1. Introduction

Today’s consumers navigate a market that is becoming more and more flooded with environmental responsibility declarations. The growing awareness of environmental issues has led to a spike in green marketing, where businesses highlight their dedication to sustainability. Amid this trend lies a widespread challenge, which is greenwashing. Greenwashing refers to the fabrication of environmental claims or the exploitation of unreliable data to support an unjustified green image [

1]. Indeed, greenwashing is defined as the company’s attempt to conceal its ecologically harmful practices by spreading false or unclear information about sustainability activities for marketing objectives. This behavior undermines credibility, may have negative effects on customers and the environment, and detracts from sincere attempts to be sustainable.

Because consumer engagement reflects the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral investment that individuals make in brand interactions, perceived greenwashing can severely diminish engagement. When consumers detect inconsistency between a brand’s claims and actions, their engagement declines, weakening trust, loyalty, and long-term commitment to the brand [

2].

In the era of environmental friendliness and sustainability, which is characterized by a global shift toward more responsible and eco-conscious practices, brands worldwide are using the greenwashing strategy, which involves misleading consumers into having positive opinions about an organization’s environmental performance by using deceptive methods and false information about its green products and green image [

3]. Consumers are harmed by such dishonest behavior, which also weakens real sustainability programs by lessening their impact [

4]. This makes greenwashing not only a marketing concern but also a barrier to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), as it discourages authentic engagement with sustainable products and practices.

Although earlier research, such as Persakis et al. [

5] and Amatucci and Mollo [

1], has targeted greenwashing prevalence, little work has pointed out psychological processes like belief disconfirmation and cognitive confusion whereby greenwashing diminishes consumers’ trust and loyalty. This paper attempts to bridge this gap by investigating the impact of greenwashing on consumers’ expectations of a brand, a brand’s perception, emotional response, and finally, brand trust and loyalty. Specifically, it addresses the extent to which greenwashing disrupts brand-related mental processes and thus damages two key drivers of brand equity: consumer trust and loyalty. By positioning these mechanisms in the larger issues of consumer management and sustainable marketing, this study situates greenwashing as a short-term inhibitor to effective sustainability communication strategies.

This study proposes a unified conceptual model that integrates the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Expectation Confirmation Theory (ECT), and Consumer–Brand Relationship (CBR) theory to explain how greenwashing weakens both cognitive (belief disconfirmation, confusion) and relational (trust, loyalty) dimensions of engagement.

The academic contribution of the study lies in its broadening of existing knowledge on consumer behavior, sustainable marketing, and attitudes toward marketing theory. By exploring the effects of greenwashing on attitudes, expectations, and behaviors, the study contributes to the sustainable marketing discourse. The study offers a balanced presentation of authentic and inauthentic green marketing, elaborating on the ethical complexity and strategic risk of branding sustainability discourses. In doing so, this study also describes how trust loss and consumer confusion function as hindrances to companies to develop long-run sustainable consumer relationships, which is one major element in consumer management in times of sustainability transitions.

Notably, this study is set in the Lebanese context, a country that suffers from economic uncertainty, ecological pressures, and weak regulatory enforcement of marketing claims. This context provides an interesting backdrop against which to examine the effect of greenwashing since the consumers in Lebanon may be prone to increased cynicism towards corporate messages. By centering on a market with under-studied consumer behavior patterns, the study adds geographic and cultural depth to existing literature and offers practical insights for businesses operating in similar emerging economies.

Apart from its academic contribution, this study holds great practical importance for policymakers, marketers, and businesses. With knowledge of how greenwashing destroys customer trust and brand loyalty, businesses can practice more honest and ethical branding practices that will reward customer relationships in the long run. For policymakers, the study can inform consumer protection policy and aid in the development of frameworks against dishonest eco-labels. Conversely, the research highlights how authenticity in sustainability programs can enhance consumer–brand relationships and stimulate meaningful progress towards environmental responsibility. Both theoretically and practically, such a dual contribution highlights the need to balance sustainable marketing programs with authentic communications, thus facilitating consumer management efforts to indeed propel sustainability agendas.

To guide this investigation and address the identified gap, the study poses the following research question: To what extent does the use of greenwashing affect consumer behavior in terms of brand trust and loyalty?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mainstream Literature

2.1.1. Green Marketing and Its Strategic Importance

Green marketing, or in other terms, sustainability marketing/eco-marketing, involves promoting green products and sustainable activities [

6]. Environmental branding, green brand image, and sustainable innovation are important for sustaining consumer trust and fostering long-term commitment [

7,

8]. The growing consciousness of consumers regarding the environment has contributed to the growing popularity of green marketing activities because of a higher identification of personal identity with sustainable consumption [

9]. While green marketing efforts can increase overall well-being in society [

10], these efforts can be manipulated. Green communication is used by some businesses primarily for the purpose of attaining a competitive edge without actual environmental gains [

11]. This tension makes it possible for greenwashing to occur.

2.1.2. Greenwashing and the Erosion of Brand Integrity

Greenwashing refers to misleading marketing practices attempting to exaggerate a business’s environmental accountability [

12]. Misleading practice happens when businesses care more about their image than the truth, leading to confusion and doubt among environmentally conscious consumers [

13,

14]. Greenwashing is categorized into seven “sins,” including hidden trade-offs, vagueness, and false labeling. These tactics employ ambiguous language or unsubstantiated assertions to capitalize on public opinion, ultimately damaging credibility [

15]. These tactics reinforce consumer cynicism and prevent genuine attempts at sustainability [

16,

17].

2.1.3. Green Consumer Behavior and the Rise of Confusion

Environmentally aware consumers often seek to align their values with sustainable purchasing choices [

18]. Nevertheless, their increased sensitivity to environmental messaging also makes them more critical of brand claims. Sustainable consumption requires behavioral discipline, yet consumers are frequently overwhelmed by the volume and inconsistency of green messages [

19]. Green confusion arises when consumers are unable to evaluate product attributes due to ambiguous, contradictory, or excessive sustainability claims [

14,

20]. This uncertainty compromises consumer confidence, especially in cases where greenwashing clouds product evaluation [

21]. To mitigate this, transparency and evidence-based claims are essential [

10].

2.1.4. Disconfirmation of Beliefs

Disconfirmation of beliefs occurs when consumer experiences fail to match pre-purchase expectations, resulting in dissatisfaction and distrust [

22,

23]. In green marketing, inflated expectations, often due to greenwashing, can lead to negative disconfirmation when reality contradicts environmental claims [

10]. This mismatch erodes consumer trust and intensifies skepticism. Several studies confirm that greenwashing contributes to belief disconfirmation by widening the gap between brand promises and actual behavior [

13,

14]. Ha et al. [

24] show that this disconfirmation mediates the relationship between perceived greenwashing and diminished brand trust. As a result, green brands risk losing consumer loyalty, particularly from individuals with high environmental involvement.

2.1.5. Brand Trust and Brand Loyalty

Trust is foundational to consumer–brand relationships, particularly in sustainability-driven contexts [

25,

26]. Brand trust reflects consumer belief in a company’s ability to consistently fulfill its environmental promises [

27,

28]. When this trust is established, it fosters emotional attachment and strengthens brand loyalty [

29]. Loyalty, in turn, is manifested through repeat purchases and advocacy, even in the face of competitive offerings or market changes [

30,

31]. Green brand loyalty is particularly sensitive to perceived authenticity and transparency [

32]. However, greenwashing disrupts this dynamic, undermining trust and ultimately breaking the loyalty cycle [

33].

Collectively, prior studies confirm that trust and loyalty are not only outcomes of perceived brand authenticity but also critical mediators between sustainable communication and long-term consumer commitment. However, much of the existing literature examines these constructs under conditions of authentic sustainability, rather than in contexts of perceived deception or greenwashing. This study extends this stream by examining how psychological mechanisms, specifically belief disconfirmation and confusion, undermine trust and, consequently, loyalty. By integrating these constructs within a multi-theoretical framework, this study contributes a deeper understanding of how violations of green brand promises disrupt the trust–loyalty chain fundamental to sustainable marketing success.

2.1.6. Sustainable Marketing Communication and Consumer Management

Sustainable marketing transcends the marketing of green products; it is a holistic business model in which profitability is realized together with environmental and social responsibility. Communication is central to this model, as it shapes consumers’ perception of genuineness in sustainability practice and makes effective choices [

6]. Effective sustainability communication allows consumers to bring their consumption habits in line with green virtues, thereby enhancing SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

However, in cases where communication is fraudulent, like in greenwashing, the legitimacy of sustainable campaign efforts is lost. Greenwashing not just damages brand reputation but also acts as a barrier to sustainable consumption by discouraging consumers from believing genuinely sustainable products [

16,

17]. This creates a paradox where attempts to take advantage of sustainability narratives fail, resulting in distrust and alienation from green markets.

From a consumer management perspective, building trust-based, long-term consumer–brand relations is critical in sustainability-oriented contexts [

25,

26]. Repeat purchasers will be more likely to shop at ethical companies, endorse green practices, and retain green products in competitive markets. Greenwashing disintegrates this relational process by causing confusion, skepticism, and distrust [

14,

20]. Consequently, untruthful communication undermines consumer control mechanisms directly that are integral to upholding loyalty in environmentally conscious markets.

Finally, institutional and cultural settings also play a role in shaping the effects of greenwashing. Within weak-regulation emerging economies such as Lebanon, greenwashing can be extremely harmful due to the fact that consumers are faced with heightened uncertainty and distrust [

34,

35]. Thus, examining greenwashing both as a communication failure and a consumer management problem is more encompassing of how it prevents the transition towards sustainable consumption.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

To achieve its objectives, this study integrates three primary theoretical perspectives: the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Expectation Confirmation Theory (ECT), and Consumer–Brand Relationship (CBR) Theory. These theories jointly allow for a structured understanding of how antecedents shape consumer expectations, how violations of those expectations (greenwashing) create disconfirmation and confusion, and how these reactions eventually damage the consumer–brand relationship.

2.2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

The TPB [

36] provides a foundational framework for understanding how individual behavioral antecedents shape brand expectations. TPB posits that behavioral intentions and, by extension, behaviors are driven by three factors: subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral beliefs.

In the context of green marketing, TPB explains how consumers form expectations of brands that communicate environmental claims. When subjective norms encourage eco-friendly behavior, and when individuals believe they have both autonomy and the means to act sustainably, their expectations of green brands increase. These expectations form the cognitive foundation upon which consumers later assess the brand’s actual performance.

Prior studies affirm these relationships. Subjective norms, such as social influence from family, friends, and media, have been found to significantly shape green purchase intentions and eco-brand perceptions [

37,

38]. Perceived behavioral control also plays a critical role; when consumers feel capable of evaluating green information or purchasing sustainable alternatives, their brand expectations are elevated [

39,

40]. Similarly, behavioral beliefs regarding the environmental and personal benefits of green products are positively associated with expectations of brand authenticity and responsibility [

41,

42].

Building on this, this study posits the first sub-research question (SRQ1), which is as follows: To what extent do consumer behavior antecedents, namely subjective norms, controlled behavior, and behavioral beliefs, influence brand expectations toward green brands? Therefore, the following hypotheses are developed:

H1. Consumer subjective norms affect positively consumer brand expectations.

H2. Consumer-controlled behavior positively affects consumer brand expectations.

H3. Consumer behavioral belief affects positively consumer brand expectations.

2.2.2. Expectation Confirmation Theory

To complement the predictive lens of TPB, ECT [

22,

23] explains how consumers evaluate post-purchase satisfaction through the lens of confirmation or disconfirmation. When a product’s performance matches or exceeds expectations, satisfaction results. However, when performance falls short, especially after high initial expectations, negative disconfirmation occurs, often leading to dissatisfaction and damaged trust.

In this study, ECT is particularly relevant to understanding how greenwashing disrupts the alignment between brand expectations and consumer perceptions. Greenwashing inflates pre-purchase expectations by presenting misleading or exaggerated environmental claims. When consumers later discover discrepancies between these claims and actual brand behavior, they experience belief disconfirmation, a cognitive and emotional response associated with broken expectations.

This phenomenon has been consistently supported by prior research. Chen and Chang [

10] found that greenwashing undermines brand credibility by creating a mismatch between perceived and actual environmental performance. Hameed et al. [

13] further showed that high brand expectations amplify disconfirmation effects when sustainability promises are unfulfilled. Ha et al. [

24] and Yang et al. [

14] validate that unmet green brand expectations lead to cognitive dissonance and skepticism, which directly erode consumer trust.

Thus, this study postulates the second sub-research question (SRQ2), which is as follows: How do greenwashing practices moderate the relationship between brand expectations and disconfirmation of beliefs among consumers?

The following hypothesis is developed:

H4. Higher brand expectations lead to greater belief disconfirmation when greenwashing is perceived.

2.2.3. Consumer Brand Relationship Theory

To address the emotional and relational outcomes of disconfirmation, this study applies the CBR Theory [

43], which suggests that relationships between consumers and brands are built on emotional bonds such as trust, attachment, and commitment. These relationships go beyond transactions and are shaped by ongoing brand experiences, perceived authenticity, and value alignment. Greenwashing, by violating these expectations, can severely damage the relational foundation that fosters loyalty.

This study draws on CBR Theory to explain how greenwashing-induced disconfirmation can create consumer confusion, which then erodes trust and weakens brand loyalty. When belief disconfirmation occurs, consumers may struggle to reconcile brand messaging with actual behavior, resulting in uncertainty and reduced cognitive clarity. This confusion destabilizes the brand relationship, leading to skepticism, mistrust, and eventual disengagement.

Prior research supports this mechanism. Chen and Chang [

10] showed that disconfirmation of environmental claims leads to confusion, which mediates the impact of greenwashing on trust. Aji and Sutikno [

20] emphasized that vague or inconsistent green messaging fosters “green confusion,” especially among consumers with high environmental involvement. Yang et al. [

14] found that such confusion reduces consumers’ ability to evaluate credibility, increasing doubt and weakening emotional bonds with the brand.

As trust deteriorates, loyalty is also compromised. Studies by Bernarto et al. [

27] and Hussain and Waheed [

28] confirm that brand trust is a key driver of long-term loyalty, particularly in sustainability contexts. Rejitha and Jayalakshmi [

26] further argue that green brand loyalty hinges on consumers’ belief in the brand’s authenticity and transparency. When that trust is broken due to greenwashing, loyal behaviors decline, and consumers may shift to competitors who appear more credible and values-aligned.

Thus, this study posits the third and fourth sub-research questions (SRQ3 and SRQ4), which are as follows: How does disconfirmation of beliefs resulting from greenwashing influence consumer brand confusion? How does brand confusion impact brand trust and, subsequently, brand loyalty in the context of greenwashing?

H5. Belief disconfirmation positively influences consumer confusion.

H6. Consumer confusion resulting from greenwashing practices negatively affects consumer brand trust.

H7. Brand trust positively affects brand loyalty.

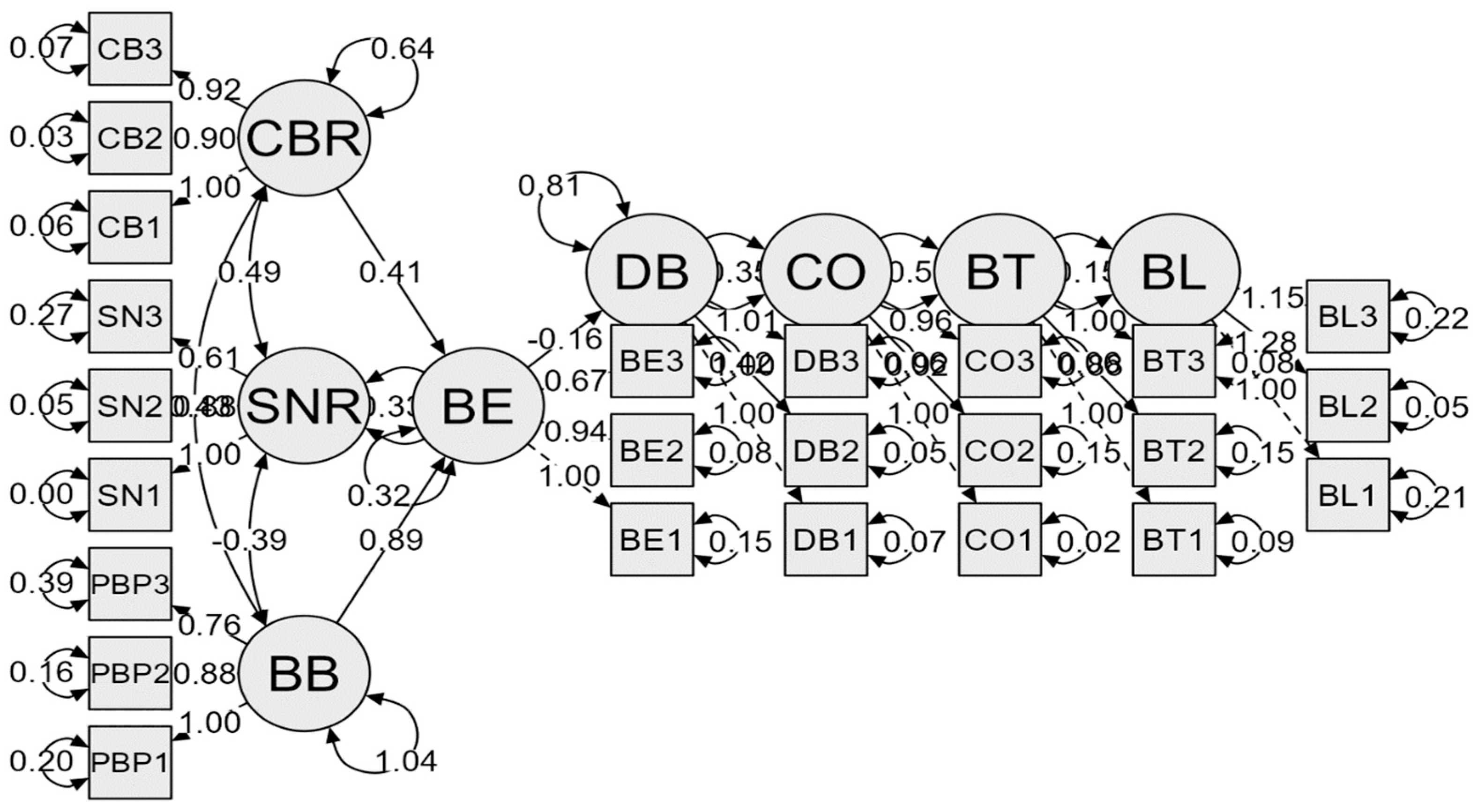

In alignment with the underpinning theories, the conceptual model in

Figure 1 serves to clarify the foundation of the research and the expected relationships among variables.

2.3. Research Context

Due to growing consumer demand for eco-friendly products and growing environmental challenges, businesses have shifted their management from brand equity to green brand equity in recent years [

44]. Environmental issues, therefore, encourage consumers to be more proactive and mindful of green consumption [

45]. This has led companies to use deceptive measures to attract green consumers without engaging in costly eco-friendly practices; this phenomenon is known as greenwashing [

15]. As awareness of greenwashing rises, numerous studies have talked about the subject and dug deeper into its root causes [

34,

35]. Nonetheless, certain concerns have been perceived regarding the impact that greenwashing may cause, especially on consumer behavior and the brand itself [

35]. In this perspective, some statistics on eco-friendly consumers on a worldwide scale are provided. Consumer demand for sustainable products has surged, with 72% purchasing more eco-friendly goods and 79% willing to switch to greener options. Over half (55%) are willing to pay extra, and sustainable products grow 2.7 times faster than non-sustainable ones. Trust is key, as 92% favor brands with eco-friendly practices. Businesses respond, with 77% adopting sustainability to boost loyalty and 63% seeing it as beneficial for reputation and profit. Additionally, 81% of consumers expect companies to integrate sustainability into marketing, while 53% support recyclable packaging and reducing plastic use.

The first academic research, in the context of Lebanon, related to green marketing was written by Taleb [

46]. Since then, numerous authors have noticed that more businesses are finding ways to change their traditional practices into “greener” ones. In Lebanon, startups and rising companies are building their mission and vision around the concept of sustainability [

47]. There is a constant growth of green consciousness amongst Lebanese consumers and the importance of conserving the image of a green Lebanon [

48]. Lebanese consumers are affected by their sense of collectivism, subjective norms, social interest, and the growing green advertising. They have the willingness to change their buying habits and put effort into purchasing brands that are known to be eco-friendly. The high sense of collectivism and constant societal influence form a decent part of Lebanese buyers’ decision-making abilities. Many Lebanese customers became environmentally conscious and started to support businesses that are socially responsible and engaged in green practices.

3. Methodology

This study employed the positivist philosophy and the deductive approach, which is directly related to the quantitative explanatory research method.

The random sampling technique was used to recruit respondents. To maintain statistical rigor, it is commonly recommended, based on experience and as a rule of thumb, to have a sample size of 300 valid observations for multivariate statistical analysis techniques [

49]. A total of 500 questionnaires were sent to Lebanese consumers, and a final sample size of 375 individuals was obtained; thus, a response rate of 75%.

The questionnaire was created following a comprehensive study of the literature, which included research on consumer green behavior, brand expectations, green confusion, disconfirmation of beliefs, and the influence of greenwashing on different factors in the business world. It included statements on a 5-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree), as well as closed-ended questions for gathering sociodemographic data. The decision to utilize five positions was deemed suitable as it allowed participants to articulate their opinions with precision [

50]. The questionnaire included three sections and a total of 37 questions. Section one included socio-demographic data, section two included statements related to green behavior, and section three included statements related to greenwashing behavior. Section one included 6 questions that were adapted from the study of Vilkaite-Vaitone [

51] on consumer demographics and green purchasing behavior. Section two focuses on green behavior, containing 9 statements that assessed consumer attitudes and habits regarding sustainability, environmental responsibility, and eco-friendly purchasing decisions. These items were based on established scales from the study of Kumar [

52] on pro-environmental consumer behavior. Section three explored greenwashing behavior through 22 statements measuring perceptions of brand trust, skepticism toward green claims, and the influence of social and personal factors on purchasing decisions. These items were derived from the study of Andreoli et al. [

53] on green marketing credibility and consumer trust in sustainability claims.

The questionnaire was administered in English, as the majority of Lebanese consumers are bilingual and accustomed to English-language surveys and marketing materials. To ensure clarity and comprehension, a pilot test was conducted with 30 participants. Minor adjustments were made to simplify wording and ensure that the concepts and statements are clearly understood.

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants using a filter question (“Do you agree to participate in the study?”) in the questionnaire directly after the introduction to ensure voluntary participation. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Higher Center for Research (HCR) at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK) under the reference HCR/EC 2025-054.

The data were analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). To ensure data adequacy for factor analysis, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were first conducted. The measurement model was then assessed through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to evaluate item reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Reliability was examined using Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability (CR), while Average Variance Extracted (AVE) assessed convergent validity. Discriminant validity was verified through the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. Model fit was evaluated using multiple indices according to conventional cutoff criteria. After confirming measurement validity, the structural model was tested to evaluate the hypothesized relationships among the constructs. Path coefficients (β) and p-values determined the significance and direction of each relationship. This procedure ensured statistical rigor and consistency with the study’s theoretical foundation in the TPB, ECT, and the CBR framework.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Profile

As shown in

Table 1, the majority of the respondents are females, with 61% while males make up around 39%. As for the age, the majority falls in the bracket 25–30, followed by 21–25, as they represent around 61%. Most participants are full-time employees (45.3%), with part-time employees (35.5%) and freelancers (14.4%) making up a significant portion. Educationally, the vast majority hold a bachelor’s degree (79.5%), while 20.5% have graduate-level education. A notable portion of respondents are engaged (49.1%), while 16.8% are single, and 34.1% are married with children. Regarding income, nearly half earn between

$1000 and

$2000 per month (45.3%), while 33.6% fall into the

$2000–

$3000 bracket. Only a small percentage (5.1%) earn above

$3000.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The KMO test scored 0.847 (

Table 2), which is rated as good. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity showed a

p-value below 0.001, showing statistical significance. Thus, the variables’ correlation matrix is not an identity matrix, which suggests that the scale created suits further confirmatory factor analysis.

With a

p-value close to zero, the chi-square statistic produced a value of 1502.968 (

Table 3). Therefore, it would appear reasonable to reject the model’s adequacy premise based on this finding. Other indices were looked at to evaluate the fit of the CFA model; nevertheless, because of the test’s sensitivity to large sample sizes, in this case, 375 individuals. Several other indices, as shown in the above table, show a statistically significant fit of the model measurement because their associated coefficients match the appropriate cutoff.

Table 4 shows that all components surpass the recommended cutoff AVE values of 0.5, which indicates to have meaningful correlations. The CR values for most of the variables are above the threshold of 0.7. These findings lend support to the good statistical converging validity and reliability of the scale.

All the factors in

Table 5 show an HTMT ratio that is lower than 0.85. Those results confirm the high distinction between the different variables, which supports the theory of having a fitting discriminant validity for all of them. Moreover, the confirmatory positive statistical results SEM analysis are being operated.

4.3. Hypotheses Validation

The results in

Table 6 show the hypothesis testing results based on SEM.

The first hypothesis that subjective norms positively influence brand expectations was verified (β = 0.328; p-value < 0.001). This shows that the subjective norms that can influence customer perception can increase the likelihood of expectations towards a green brand. The subjective norms are formed by the abundance of different external societal factors, like friends, family, and products, that would consequently alter the behavior and expectation of the customer, which might lead to either positive or negative disconfirmation of beliefs if greenwashing occurs. The positive relationship portrays the experience of the customer with the green brand and the social standards that people have set for this company.

The second hypothesis that controlled behavior positively influences brand expectations was verified (β = 0.409; p-value < 0.001). The result suggests that controlled behavior, which refers to actions that are consciously regulated, would lead to deliberate decision-making processes, such as making intentional, thoughtful choices based on careful consideration of the brand’s reputation, quality, ethical practices, or value proposition.

The third hypothesis that behavioral beliefs positively influence band expectations was verified (β = 0.891; p-value < 0.001. Consequently, when consumers have positive beliefs or perceptions of a brand’s performance, they tend to have higher expectations for future products and services from that brand.

The fourth hypothesis, that the higher the brand expectations, the greater the likelihood of belief disconfirmation when greenwashing is revealed, was verified (β = −0.157; p-value < 0.001). Thus, there is a negative relation between brand expectations and the disconfirmation of beliefs. Such results refer to how consumer expectations influence the emotional and cognitive response when actual brand performance deviates from those expectations. Disconfirmation of beliefs occurs when there is a mismatch between what consumers expect from a brand (based on their prior beliefs or experiences) and what they experience (the brand’s actual performance). This disconfirmation can lead to positive or negative outcomes, depending on whether the actual performance exceeds or falls short of expectations.

The fifth hypothesis that the disconfirmation of beliefs positively influences customer confusion was verified (β = 0.355; p-value < 0.001). Thus, the relationship between disconfirmation of beliefs and consumer confusion is rooted in how discrepancies between expected and actual brand performance can lead to uncertainty, frustration, and cognitive dissonance. Disconfirmation of beliefs occurs when consumers’ expectations about a brand or product are either not met (negative disconfirmation) or exceeded (positive disconfirmation). When the brand’s performance doesn’t align with these expectations, it can lead to confusion about the brand, its offerings, or the decision-making process itself.

The sixth hypothesis that consumer confusion resulting from greenwash practices affects negatively consumer brand trust is verified (β = −0.567; p-value < 0.001). Thus, consumer confusion significantly impacts brand trust, leading to brand distrust, as confusion creates uncertainty, which erodes confidence in a brand’s reliability, honesty, and quality. Trust is a key component of brand loyalty, and when consumers are confused, their trust in the brand may waver, leading to skepticism or even outright mistrust.

The seventh hypothesis that brand trust positively affects the consumer’s loyalty toward the brand is verified (β = 0.152; p-value < 0.05). This indicates that brand trust and brand loyalty are interrelated concepts that can significantly impact a brand’s reputation, customer retention, and long-term profitability. On the other hand, greenwashing can lead to mistrust; thus, brand mistrust is often a precursor to non-loyalty, as a lack of trust erodes the emotional and rational connection between consumers and the brand, leading them to switch to competitors.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of the Findings

This study sets out to explore the psychological mechanisms through which greenwashing affects consumer–brand relationships, focusing on how expectations, belief disconfirmation, confusion, and trust collectively influence brand loyalty. Grounded in the TPB, ECT, and CBR Theory, the findings validate a comprehensive model that integrates cognitive and emotional pathways in green consumer behavior.

The results confirm the central tenets of TPB, showing that subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral beliefs significantly shape brand expectations. In line with studies by Paul et al. [

37], Yadav and Pathak [

38], and Han et al. [

39], the findings demonstrate that expectations toward green brands are socially and behaviorally constructed. This shows that consumer intentions and expectations toward sustainability are not purely rational but also impacted by peer dynamics, perceived autonomy, and belief in green outcomes. In Lebanon, where collectivist traditions, media discourse, and eco-social expectations increasingly shape consumer orientations [

54], TPB offers a powerful perspective. Lebanese consumers, under subjective normative and green awareness influences, are shown to be particularly concerned with how brands communicate environmental sustainability, justifying the strategic role of green marketing in communicating realistic, credible promises.

Furthermore, the results support ECT theory in the sense that heightened brand expectations are shown to lead to stronger belief disconfirmation when customers experience greenwashing. This is in line with previous studies [

10,

13], wherein overstated or false claims of sustainability serve to enhance the occurrence of cognitive dissonance since promises were not fulfilled. This psychological disconnect, where anticipated and actual become dissociated, was particularly pronounced within this study. Greenwashing not only erodes a brand’s reputation; it turns the consumers’ internal logic for determining authenticity on its head, inducing negative affective states that reverberate throughout the consumer–brand relationship. In risk categories like Lebanon, where brand trust is already fragile, the reputational damage of greenwashing could be more impactful.

Consistent with the existing evidence on consumer confusion in previous studies [

14,

20], this study confirms that belief disconfirmation resulting from greenwashing leads to heightened cognitive confusion. Consumers overwhelmed by vague, conflicting, or unverifiable environmental claims struggle to make informed decisions, which introduces uncertainty and frustration. Confusion was found to negatively impact brand trust, validating prior research that suggests greenwashing obscures transparency and erodes the perceived reliability of the brand [

10]. The results affirm that confusion is not just a by-product of misleading messages; it is a central pathway through which consumer trust is destabilized. This highlights the critical role of clear, substantiated, and consistent communication in mitigating trust erosion, especially in sustainability-driven industries.

It is worth noting that the degree to which consumers identify and react to greenwashing may depend on their level of environmental literacy and sustainability awareness. As highlighted in prior literature [

3,

55], not all consumers possess the same ability to critically evaluate environmental claims. In societies where environmental education and public discourse on sustainability remain limited, such as Lebanon, some consumers may fail to recognize deceptive claims and thus remain neutral or indifferent to greenwashing. This may partly explain why, despite the growing awareness of sustainability, greenwashing still exerts influence on consumer perceptions and purchasing behavior. Therefore, environmental literacy can shape the intensity of belief disconfirmation and confusion. Increasing sustainability knowledge among consumers could reduce the impact of greenwashing and enhance their capacity to make informed choices.

Moreover, the results support the CBR Theory’s claim that trust is the cornerstone of brand loyalty [

27]. Once confusion weakens trust, consumers become less emotionally committed and more likely to disengage, switch brands, or resist sustainability messaging altogether. In the Lebanese context, where consumer trust is often eroded by broader political and economic uncertainties, brands perceived as inauthentic face an even steeper uphill battle to build or maintain loyalty. This confirms existing empirical evidence [

26,

28] that shows green brand loyalty depends not just on product quality or innovation but on perceived transparency, alignment with consumer values, and emotional credibility. Greenwashing breaks this emotional contract, resulting in not only short-term confusion but long-term disengagement.

Finally, these results carry important implications for consumer management in sustainability contexts. The study demonstrates that greenwashing disrupts the trust-based relationships that are essential for long-term consumer management. By creating confusion and disconfirmation, greenwashing weakens consumer loyalty and reduces willingness to engage with sustainable products. In this way, effective consumer management strategies in sustainability are not only about promoting eco-friendly products but also about ensuring that communication is transparent, credible, and aligned with actual practices. Managing consumers in this context requires reducing skepticism, reinforcing authenticity, and building trust as the foundation for sustained engagement with sustainability initiatives.

5.2. Country-Specific Interpretation

In contextual terms, the findings of this study are deeply rooted in Lebanon’s socio-economic and institutional context, which shapes how consumers interpret and respond to sustainability communication. Lebanon’s prolonged economic crisis, recurrent political instability, and weak enforcement of environmental and advertising regulations have fostered a general sense of skepticism toward corporate claims. This institutional fragility reduces public confidence in both regulatory oversight and corporate integrity, amplifying consumer sensitivity to potential deception such as greenwashing. Furthermore, the economic strain faced by Lebanese consumers, marked by currency devaluation, high inflation, and purchasing power erosion, intensifies pragmatic consumption behaviors, where trust and credibility become decisive in brand evaluation. In parallel, Lebanon’s collectivist social structure and growing environmental discourse among younger, educated segments promote a heightened awareness of sustainability narratives, yet also a sharper emotional reaction when these narratives are perceived as manipulative. These contextual factors explain why greenwashing in Lebanon triggers strong disconfirmation and confusion responses, as demonstrated in this study. The results, therefore, highlight that trust erosion is not only a psychological consequence but also a reflection of deeper socio-economic and institutional vulnerabilities in developing markets.

5.3. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to theory by extending and integrating established behavioral and relational frameworks in the context of greenwashing. First, it expands the TPB by positioning subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral beliefs as antecedents to brand expectations, a construct less emphasized in prior TPB applications. This shifts the theory’s utility from mere behavioral prediction to expectation formation in green consumer contexts. Second, the study enriches ECT by demonstrating how greenwashing functions as a moderating trigger for belief disconfirmation, linking misaligned brand messaging with cognitive and emotional fallout. Third, through CBR Theory, it highlights the mediating role of confusion as a cognitive mechanism that bridges disconfirmation and trust erosion, providing insight into how relational bonds are destabilized in sustainability marketing. Finally, by applying these frameworks in a developing, turbulent country context, this study addresses the underrepresentation of non-Western markets in green consumer behavior studies. The results highlight how cultural factors like collectivism and institutional trust gaps intensify consumer sensitivity to greenwashing, offering contextual nuance to global sustainability discourse.

5.4. Practical Implications

This research offers marketers, brand managers, and policymakers sound, evidence-based advice in the wake of growing demand for sustainability.

The influence of subjective norms, control of behavior, and belief on brand expectations reasserts the overriding value of authentic and open communication. Green marketing must transcend cosmetic environmental labeling or mere promises and instead be based on quantifiable, verifiable environmental performance. Consumers nowadays, especially those in cynical markets like Lebanon, are not only aware but also increasingly critical of performative sustainability.

Second, the study discovers that green promise versus brand behavior misalignment, a distinctive feature of greenwashing, leads to belief disconfirmation and cognitive confusion, both of which result in massive loss of trust. Brands, fearing reputation damage and customer switching, will have to revisit and align their sustainability communications with business deeds. Misleading communication, even if unintended, has serious costs to consumer loyalty.

Third, the paramount role of trust in fostering brand loyalty highlights the significance of ethical branding. Businesses that demonstrate transparency, even acknowledging sustainability limitations, build stronger, longer-lasting relationships than those masking shortcomings with green rhetoric. Trust is not just a value; it is a strategic asset in loyalty building.

Finally, for regulators and policymakers, these findings underscore the urgent need for stronger oversight of environmental marketing claims. Clear standards, third-party certifications, and penalties for false claims are essential to curb greenwashing and level the playing field for genuinely sustainable brands. In emerging markets like Lebanon, where institutional trust is already fragile, regulatory credibility can either reinforce or erode public confidence in sustainability efforts.

6. Conclusions

In an era where sustainability is both a strategic imperative and a moral imperative, this study provides a timely contribution to the understanding of the cost of greenwashing on sustainable consumer marketing and management. Grounded in the TPB, ECT, and CBR Theory, this study develops and tests empirically an integrative model explaining how greenwashing inflates brand promise, generates disconfirmation and belief confusion, and ultimately annihilates trust and loyalty. The results show how subjective norms, perceived control over behavior, and behavior beliefs play a determinative role in shaping green brand expectations. But when these are transgressed by making fake claims of being sustainable, consumers remain confused and suspicious, draining their intention to interact with brands that self-present themselves as sustainable. Most significantly, though, this type of trust destruction not only affects individual brands but also stifles further progress towards sustainable consumption since consumers begin questioning stories of sustainability in general.

Theoretically, the study adds to sustainable marketing scholarship by illustrating how psychological processes, i.e., expectation disconfirmation and confusion, function as barriers to sustainability transitions. By casting trust and loyalty as the outcomes not just of branding but also of transparent sustainability communication, the article highlights the necessity of addressing consumer management from an authenticity and credibility point of view. In so doing, it adds contextual richness by taking an emerging market setting where loose regulation and fragile consumer trust exacerbate greenwashing threats.

Practically, the results emphasize the need for alignment of sustainability communication with visible practice. For managers, brand authenticity is not only an ethical obligation but a consumer management strategy instrumental to building long-term loyalty. For policymakers, the implications are the urgent need for stronger regulation of environmental marketing claims, more transparent eco-labeling criteria, and consumer protection policies that ensure the integrity of sustainable markets.

Thus, this research affirms that greenwashing undermines the pillars of sustainable marketing itself. By annihilating trust, it lowers consumer–brand relations and slows progress toward SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production. To achieve material sustainability benefits, firms must move beyond symbolic claims and invest in transparent communication and authentic actions. Only then shall sustainable marketing fulfill its promise to foster both consumer loyalty and genuine ecological responsibility.

While this study provides contributory insights to green consumer behavior and green marketing literature, some limitations are noted that need consideration, and suggestions for future research are made.

Firstly, while the context of this study at Lebanon, a country with unique socio-economic challenges and weak regulation enforcement, it offers a rich context but limits the external validity of the findings. Although this context fills a critical research gap regarding emerging markets, cross-country studies would help to put the proposed model through additional tests of its strength in more stable or institutionally different and culturally diverse environments. Extrapolation to additional developing or developed economies would further enable comparative studies of how cultural values, regulation maturity, and environmental awareness affect responses to greenwashing.

Second, the study did not distinguish between types of greenwashing, i.e., symbolic vs. substantive claims, which are variably likely to impact consumers psychologically. Future studies could investigate sectoral dynamics by examining industries such as fashion, food, cosmetics, or energy, where sustainability narratives are very prevalent but greatly vary in plausibility and impact.

Third, based on the significance of environmental literacy, future studies should also account for consumers’ environmental literacy as a moderating variable, since individuals with limited sustainability knowledge may not perceive greenwashing cues in the same way as environmentally educated consumers.

Further, as consumer activism and digital advocacy continue to grow, further studies will be able to investigate how active consumers, via social media, online reviews, or blogs, are able to influence corporate behavior and demand more accountability and transparency. Research in this field would be able to reveal valuable information on the new dynamic between consumers and brands during the age of ethical consumption. Thus, future research can build a more holistic, workable understanding of greenwashing, its causes, consequences, and intended solutions in markets, industries, and technologies.

In the end, the path toward genuine sustainability demands that marketing transcend symbolic gestures and embrace transparent, evidence-based practice. By deepening understanding of how greenwashing disrupts consumer trust and loyalty, this study provides both scholars and practitioners with the insight needed to realign sustainability communication with authentic action, ensuring that future marketing serves not only profit, but also planetary well-being.