Abstract

Global brands are increasingly establishing dedicated administrative departments to strengthen sustainability and resilience in their supply chains. However, overlooking these aspects at the supplier level can result in significant costs and systemic vulnerabilities. This study addresses this gap through four key contributions: First, we provide a comprehensive sustainability assessment by simultaneously considering economic, environmental, and social pillars along with resilience, operationalized through twenty-four sub-criteria. Second, we explicitly incorporate human judgment and uncertainty by modeling supplier evaluation with interval weights, capturing the ambiguity and subjectivity inherent in expert decision-making. Third, we propose a novel hybrid methodology, integrating lexicographic goal programming (LGP), the analytical hierarchy process (AHP), and two-stage logarithmic goal programming (TLGP) in a systematic framework. Finally, we validate the approach in real-world contexts through case studies in the electronics and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) industries. The results reveal notable differences in supplier rankings when comparing LGP and TLGP, highlighting the methodological implications of advanced goal programming in uncertain environments. Overall, this study advances supplier selection research by offering both a validated decision-support tool for practitioners and methodological insights for scholars working on sustainability and resilience under uncertainty.

1. Introduction

In today’s landscape of technological advancement and global interconnectedness, purchasing management has become a strategic priority in supply chain operations. As supply chains become more complex, the supplier selection process (SSP) plays a pivotal role, influencing cost efficiency, product quality, operational reliability, and customer satisfaction. Given the substantial investments allocated to procurement, choosing the right suppliers is not only an economic necessity but also a strategic imperative. Poor supplier choices can expose firms to delivery delays, quality issues, or reputational risks.

In recent years, the resilience of supply chains has gained prominence, particularly in light of frequent disruptions driven by political instability, pandemics, and natural disasters. Resilience, originally a concept from materials science, refers to a system’s capacity to absorb shocks and recover from disturbances while maintaining operational continuity [1,2]. In parallel with this, sustainability has become an equally critical concern in supply chain strategy, encompassing economic, environmental, and social dimensions. In this context, sustainable supplier selection (SSS) enables organizations to align procurement practices with broader social and ecological goals while ensuring long-term efficiency. However, integrating sustainability and resilience in SSP presents a dual challenge. First, the evaluation of sustainability criteria often relies on qualitative and subjective assessments, which are not easily captured by traditional quantitative tools. Second, the uncertainty inherent in human judgment complicates the decision-making process. Decision-makers may struggle to provide precise or consistent evaluations, especially when multiple, sometimes conflicting, criteria must be considered [3]. These challenges are particularly acute in multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) contexts, where assigning weights and comparing alternatives require robust mechanisms to handle vagueness and incomplete information [4].

Although various MCDM methods, such as analytical hierarchy process (AHP), best-worth method (BWM), data envelopment analysis (DEA), and analytic network process (ANP) have been used to support supplier evaluation [5]; many of these methods rely on crisp inputs and deterministic assumptions. These methods often fail in capturing the ambiguity and fuzziness of real-world judgments. To address these limitations, fuzzy extensions (e.g., fuzzy AHP and fuzzy ANP) have been introduced to incorporate uncertainty into the decision-making process. Another promising stream of research involves goal programming (GP), which accommodates multiple, often conflicting goals. One such extension, lexicographic goal programming (LGP), introduced by [6], allows decision-makers to prioritize objectives in a hierarchical structure. Building on this, Islam et al. [7] applied LGP to handle weight estimation from interval-valued pairwise comparisons, improving robustness under uncertainty. More recently, Wang et al. [8] proposed the two-stage logarithmic goal programming (TLGP) approach, which refines priority weights through a two-step process: minimizing inconsistencies in interval matrices, then deriving the final priorities.

Despite these methodological advancements, existing research has rarely addressed supplier selection in the electronics industry, specifically exploring the integration of sustainability and resiliency under uncertainty within the context of the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) industry. Most models focus on one or the other, and often rely on crisp inputs that fail to reflect real-world ambiguity. Furthermore, few approaches offer a structured framework to handle both interval-based uncertainty and multi-layered goal prioritization, especially when evaluating a large set of sustainability and resiliency criteria.

To address these gaps, this paper proposes a novel decision-making methodology for the uncertain resilient sustainable supplier selection (URSSS) problem. The methodology integrates AHP, LGP, and TLGP to support supplier evaluation under uncertainty. A structured questionnaire comprising four main criteria and twenty-four sub-criteria was distributed to fifty industry experts. Their inputs, expressed as interval weights, capture the ambiguity inherent in subjective preferences. AHP is used to derive criteria weights, followed by LGP to compute crisp evaluations, and TLGP to finalize supplier prioritization. Moreover, the proposed approach is applied to real-world case studies in the electronics and UAV sectors. The findings reveal notable differences in supplier rankings between the LGP and TLGP models, underscoring the importance of methodological choice in decision-making under uncertainty. By addressing both sustainability and resiliency within an uncertain MCDM framework, this research contributes a more comprehensive and realistic model for supplier evaluation.

To address the identified research gap, this study is guided by the following questions:

- How can sustainability and resilience dimensions be integrated into the SSP under uncertainty, particularly in high-tech industries such as UAVs?

- How do supplier rankings vary when applying LGP compared to TLGP, and what are the implications of these differences for methodological robustness and decision stability?

- How does the proposed decision framework enable managers to balance trade-offs among economic, environmental, social, and resilience objectives in supplier selection decisions?

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews some related works and defines the research gap. Section 3 presents the problem under consideration. Section 4 outlines the proposed methodology that integrates AHP, LGP, and TLGP. Section 5 presents the case study and analyzes the numerical results obtained. Section 6 presents some managerial insights for decision-makers. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper by outlining some research directions.

2. Literature Review

During recent years, specifying an appropriate supplier in the SC has been a noticeable problem, which has received much attention. Introducing additional qualitative criteria can significantly complicate these problems, particularly when this study considers the inherent subjectivity and uncertainty inherent in human evaluation. Considering all of these factors in an SSS makes it more challenging to evaluate and requires a different method and perspective to solve the problem and make a decision. To review the related research about the URSSS, five streamlines are studied: (1) supplier selection, (2) sustainable supplier selection, (3) resilience supplier selection, (4) supplier selection under uncertainty, and (5) uncertain resilience sustainable supplier selection.

De Boer et al. [9] introduced three heuristic algorithms to identify relevant supplier selection criteria and determine their relative priorities. In another study, Mukherjee [10] highlighted key characteristics essential to SSP and presented mathematical models for supplier selection under both deterministic and probabilistic scenarios. Additionally, Gupta and Barua [11] employed the fuzzy TOPSIS method to rank suppliers based on their green innovation capabilities, particularly in the context of SMEs. Borjalilu et al. [12] developed a hybrid decision-making framework combining the Entropy and VIKOR methods to address the supplier selection problem in the airline industry. It first identified key criteria and sub-criteria through literature review and expert opinions, then calculated their weights using the Entropy method, and finally ranked potential suppliers with VIKOR. The approach avoided subjectivity in weight assignment, fully utilized data, and considered group utility, ultimately selecting the most suitable supplier for flight operations. Bai et al. [13] proposed a comprehensive set of circular economy metrics for supplier selection, monitoring, and development across macro and micro levels. A hybrid decision-making method integrating BWM, Regret Theory, and dual hesitant fuzzy sets was developed to evaluate suppliers, accommodating decision-makers’ psychological behavior and conflicting opinions. Nayeri et al. [14] developed a novel supplier evaluation model integrating circular economy, viability, and Industry 5.0 dimensions using a stochastic fuzzy BWM and a modified stochastic fuzzy COPRAS approach. Applied to an automotive industry case, the model identified key performance indicators and ranked suppliers.

Nowadays, SSS has garnered increasing attention due to its integration of social, environmental, and economic dimensions. As sustainability remains a core issue in supply chain management (SCM), many researchers have explored models that incorporate sustainability criteria. In this field, Dai and Blackhurst [15] proposed a hybrid approach combining AHP with quality function deployment to incorporate sustainability considerations into supplier selection. Fallahpour et al. [16] utilized survey-based data to identify sustainable criteria and applied a hybrid model to prioritize the suppliers. Kannan [17] introduced a three-phase methodology applied to the Indian textile industry, integrating the perspectives of multiple stakeholders on sustainability. In more recent work, Zhang et al. [18] proposed a novel green supplier selection (GSS) approach that addressed uncertain information and decision-maker preferences using hesitant fuzzy sets. It integrated the LINMAP method with HFS, aggregated evaluations through the hesitant fuzzy weighted averaging operator, and analyzed consistency using TOPSIS indexes to identify the optimal supplier. The approach’s feasibility and effectiveness were demonstrated through sensitivity analysis and a case study. Hamdan et al. [19] addressed a deterministic multi-period single-product GSS and order allocation problem, considering suppliers’ varying availability, costs, and green performance across time. A bi-objective integer linear programming model was developed to maximize the total green value while minimizing total costs under different quantity discount schemes. The study showed that environmental solutions differed from economic ones and validated a heuristic approach as efficient and accurate for large-scale GSS problems. Alastal et al. [20] presented a literature review on GSS, emphasizing the vital role of MCDM in supporting sustainable business strategies. It also offered recommendations for industry practitioners to apply adaptive MCDM models that can effectively address changing sustainability standards and stakeholder expectations.

Beyond sustainability, several studies have also addressed the resilience aspect of supplier selection. For instance, Rajesh and Ravi [21] used the AHP and ANP to rank resilient suppliers, while Torabi et al. [22] proposed a bi-objective probabilistic two-phase stochastic model to prioritize suppliers under operational and disruption risks. Sahu et al. [23] incorporated resilience factors into supplier selection using the fuzzy VIKOR method. Parkouhi and Ghadikolaei [24] combined fuzzy ANP and gray VIKOR to identify the most resilient supplier by evaluating resilience element weights. Lastly, Hosseini and Khaled [25] classified resilience into absorptive, adaptive, and restorative capacities, proposing an integrated model to assess resilience criteria in SSP. Shidpour and Shidpour [26] investigated the impact of corporate social responsibility on supplier selection and supplier market share in the oil industry.

Recently, several scholars have focused on supplier selection and related keywords, including uncertainty, sustainability, and resiliency. For example, Mahmoudi et al. [27] extended a decision-making technique to manage the SSP in a green and resilient SCM based upon an ordinal priority approach. Echefaj et al. [28] proposed an advanced SSP approach to obtain the optimal supplier regarding the circular, resilient, and sustainable criteria. Nayeri et al. [29] investigated the order allocation and SSP based on stochastic fuzzy BWM, focusing on three pillars: resiliency, sustainability, and responsiveness. Zhao et al. [30] presented an integration algorithm based on rough set theory and developed the VIKOR method to find the best resilience SSS. Sheykhizadeh et al. [31] introduced a new framework for determining resilience SSS by applying fuzzy MCDM, fuzzy BWM, and fuzzy AHP to the oil industry in Malaysia. Taghavi et al. [32] introduced a method to minimize the risk of sustainability and resiliency in the SSP and production scheduling under disruption risk based on conditional value at risk optimization. Li et al. [33] proposed a digital twin for SSP considering sustainable and resilient aspects in a fuzzy situation.

Table 1 presents a comprehensive summary of methodologies employed in the SSP under the lenses of sustainability, resilience, and uncertainty. Early research primarily relied on deterministic models and quantitative techniques, such as the AHP and linear programming, to optimize supplier decisions. As the field progressed, sustainability considerations were increasingly integrated through fuzzy logic and various MCDM approaches. More recent advancements have focused on combining sustainability and resilience using hybrid methods, including fuzzy VIKOR, stochastic weighting, and ontology-based frameworks. These developments underscore an increasing recognition of the complexity and uncertainty inherent in real-world supply chains. However, existing studies often fall short in two key areas: (1) adequately modeling the ambiguity inherent in human judgment, and (2) incorporating a comprehensive set of sub-criteria that span all three pillars of sustainability, alongside resilience.

Table 1.

Literature Review.

To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a novel hybrid methodology that explicitly accounts for subjective uncertainty and is designed for application in complex, high-tech industry contexts. Although prior research has explored SSP under uncertain conditions and with considerations for sustainability and resilience, a notable gap remains in effectively integrating these dimensions. This study addresses that gap through the four key contributions:

- Comprehensive Sustainability Assessment: The study simultaneously considers all pillars of sustainability with specific sub-criteria for each. The economic pillar comprises nine sub-criteria, the environmental pillar six sub-criteria, and the social pillar four sub-criteria. In comparison, resilience is evaluated based on five sub-criteria, resulting in a total of twenty-four sub-criteria.

- Explicit Consideration of Human Judgment and Uncertainty: The study uniquely and explicitly addresses the role of human judgment and the inherent uncertainty and ambiguity in decision-making, a factor often overlooked in previous research.

- Novel Hybrid Approach: A novel hybrid approach, combining methods LGP, AHP, and TLGP, is proposed and systematically presented in a stepwise framework.

- Application to Electronics Industry and UAV: The proposed methodology is applied to the selection of suppliers in the electronics and UAV industries.

3. Problem Description

The supplier selection problem under today’s dynamic supply chain conditions demands a shift from traditional deterministic models to frameworks that can effectively handle uncertainty, multi-dimensionality, and conflicting objectives. In practice, decision-makers must evaluate suppliers not only on economic factors but also on their ability to contribute to environmental protection, social responsibility, and operational resilience. These evaluations often involve subjective judgments, particularly when assessing qualitative attributes like adaptability, emission control, or labor practices. However, human judgments are inherently vague and inconsistent, making it essential to model these preferences using interval data that better reflects real-world ambiguity.

To address this complexity, the URSSS problem is formulated as a multi-criteria decision-making task under uncertainty, integrating resilience and sustainability objectives into a structured prioritization framework. A set of 24 sub-criteria spanning four pillars, including economic, environmental, social, and resilience, is used to assess supplier alternatives. The evaluation process involves collecting expert inputs via interval pairwise comparisons, then applying a two-phase methodology: first, LGP is used to derive crisp weights from interval judgments; next, TLGP refines these priorities by minimizing inconsistencies in expert input. This approach enables robust supplier ranking under uncertainty, supporting more resilient and sustainable procurement decisions.

4. Proposed Methodology

This section outlines the developed methodology for solving the URSSS problem. It begins with the LGP, which handles interval judgments and derives precise weights despite inconsistent expert inputs. Next, the TLGP model is introduced to estimate interval weights by minimizing inconsistencies using logarithmic transformations. Finally, the practical implementation process is described in three steps: defining criteria and suppliers, collecting expert judgments via pairwise comparisons, and applying LGP and TLGP to determine supplier priorities.

Application of LGP and TLGP is particularly useful in the case of the URSSS problem. Firstly, LGP can convert interval-based ratings of experts into crisp weights, hence enabling reliable prioritization even when experts provide imprecise and partially inconsistent ratings. This is crucial since our research relies on subjective inputs from industry experts, where accurate numerical judgments are seldom available. Second, TLGP enhances the capability of LGP by incorporating logarithmic transformations to minimize inconsistency in interval comparison matrices. This feature enables us to account for the lower and upper limits of weights, which more accurately represent the uncertainty in human decision-making. Third, these methodologies have a high Ability to manage multiple and conflicting objectives.

In selecting suppliers, sustainable pillars and resilience considerations are generally in opposition to each other. The LGP method enables objectives to be hierarchically ordered (lexicographically) so that key goals, such as resilience or sustainability, are prioritized before considering secondary goals, like cost. This feature of the model aligns it more closely with the logic of real managerial decision-making. Moreover, TLGP is enabling sensitivity analysis and robustness evaluation. Unlike algorithms that generate a single sharp value, TLGP computes intervals of weights (upper and lower bounds). This capability enables decision-makers to evaluate the robustness of supplier rankings under various expert judgment scenarios. Such analysis finds particular utility in highly uncertain conditions, such as UAV supply chains, where even moderate changes in expert opinions have considerable effects on the ultimate supplier choice. By integrating LGP and TLGP, the proposed approach not only yields robust and consistent supplier rankings but also ensures that differences between expert opinions are addressed systematically. Consequently, these methods directly aid in fulfilling our research objective of creating a robust decision-support tool to evaluate sustainability and resilience factors comprehensively.

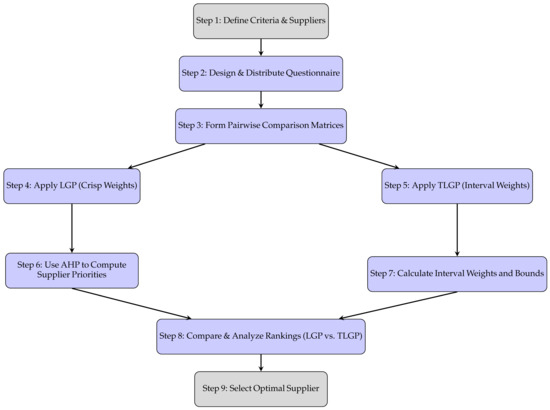

Figure 1 presents the schematic diagram of the proposed hybrid decision-making model in a clearly articulated, step-by-step format. The methodology comprises three broad phases: criteria definition, weight determination, and supplier ranking, each of which is a subset of several computational steps. The flowchart actually signifies data inputs, transitional methodological processes (AHP, LGP, TLGP), and decision support outputs. Phase I: Problem structuring and information collection (Steps 1–3); Phase II: Weight determination under uncertainty through LGP and TLGP (Steps 4–7); Phase III: Supplier ranking and decision-making (Steps 8–9).

Figure 1.

Stepwise flowchart of the proposed AHP–LGP–TLGP methodology.

4.1. Lexicographic Goal Programming

As mentioned previously, decision makers are not forced to assign a specific weight to criterion i relative to criterion j. Hence, the resulting weights fall within the bounds and , both being non-negative integers, satisfying . Consequently, the pairwise comparison matrix is expressed in Equation (1) and Constraint (2):

Subject to

Arbel and Vargas [34] indicated that a pairwise comparison matrix is consistent if and only if it satisfies Constraint (3):

Furthermore, the probability of a being preferred over b is calculated using Equation (4):

where and .

Interval judgments can be expressed by Equation (5):

This equation is valid only for consistent judgments. In the case of inconsistent judgments, two additional variables, and , are introduced, modifying the previous inequality to an inequality with Equation (6):

Here, and are non-negative real numbers with the condition that they cannot both be positive simultaneously, meaning at least one of them must be zero. The objective of this approach is to minimize the values of and related by the following optimization model:

Solving the optimization model (7) yields precise (non-interval) criterion weights, which can subsequently be used within the AHP framework to obtain the priorities among alternatives.

4.2. Two-Phase Logarithmic Goal Programming

Wang et al. [8] applied the additive constraints or equivalently to the pairwise comparison matrix in AHP and utilized the TLGP model to estimate the weights of the criteria. Consequently, the following inequalities with Equation (8) is established:

Subject to

This inequality applies to both consistent and inconsistent matrices. Since the goal of this approach is to minimize inconsistency within interval matrices, the optimization model (9) has been developed:

Non-negative variables x and y are introduced as

Consequently, model (9) is modified according to Equation (10), resulting in the following model (11):

To determine a feasible range for each weight , , the original objective function is maintained but transformed into a constraint. Thus, our goal-programming model is structured as follows:

Min/Max

where is the optimum result. Therefore, if , then model (12) is equal to the following model:

Min/Max

By solving model (13), we can obtain the interval weights for both criteria and alternatives. The lower and upper bounds for the final weights are derived using the following non-linear optimization model:

Let represent the vector of weights, and define the feasible region as

Here, and denote the upper and lower bounds of the weight for alternative , respectively. Each alternative’s total weight is thus represented as

The above process is repeated until the top level of the decision structure is reached. After obtaining the final interval weights, we apply the procedure described in Section 4.3 to determine the priority ranking of the alternatives.

4.3. Select the Best Supplier

For selecting the best URS supplier, the approach consisting of three different steps is as follows:

- Step 1: Determining Criteria and Possible SuppliersThe first step involves implementing a structured process for selecting the evaluation criteria. A thorough literature review on sustainable and resilient supplier selection is conducted, focusing on studies that emphasize economic, environmental, social, and resiliency perspectives. This review yields a preliminary list of potential criteria and sub-criteria. These initial criteria are then further refined through a series of semi-structured interviews with academic experts in SCM and industry professionals from the UAV sector. To ensure practical applicability, the company’s top management team participates in a focus group discussion to assess the completeness and practicality of the initial list. Through this iterative consensus-building exercise, the team reaches an agreement on four main criteria and twenty-four sub-criteria. The sub-criteria are then validated for their alignment with the company’s strategic objectives and operational constraints. In parallel, the company’s senior manager provides a list of potential suppliers (GoPro, Parrot, and DJI), which are already under consideration in the procurement process. These suppliers serve as the alternatives to be evaluated in the subsequent stages of the methodology.

- Step 2: Forming Pairwise Comparison MatricesA structured questionnaire is designed and distributed among the company’s experts to evaluate the relative importance of each criterion in accordance with the organization’s strategic objectives. The experts also assess the significance of each alternative with respect to these criteria, and their responses are used to construct interval pairwise comparison matrices. To develop a sustainable and robust supplier selection system, interviews are conducted with 50 managers and employees using structured questionnaires. The choice of a 50-member expert panel reflects the need to capture diverse perspectives across the dimensions of sustainability and resilience in supplier evaluation. Although no formal power analysis is performed, this sample size aligns with established practices in MCDM research, ensuring a balanced representation of expert opinions without introducing resource constraints. The selected experts include managers and professionals with substantial experience in SCM, sustainability, and resiliency, whose judgments are considered both credible and representative of real-world decision-making contexts.To control for potential bias and ensure the reliability of expert judgments in the pairwise comparison process, several complementary precautions are implemented. First, each judgment is elicited in interval form rather than as a single crisp value, which allowed the decision-makers to express uncertainty and reduced cognitive pressure that could lead to bias. Second, the answers of the 50 experts are aggregated using the geometric mean in an attempt to remove personal biases and obtain a group consensus matrix. Third, in order to establish inter-rater reliability, we compute the Kendall’s coefficient of concordance between experts’ comparison matrices. The obtained value of indicates high agreement among the experts, supporting the reliability of judgments. Finally, we test matrix consistency using both the AHP consistency ratio and a pairwise dispersion index to detect any experts whose responses differed significantly from group consensus. Matrices exceeding threshold values are carefully reviewed and adjusted through follow-up discussions. Collectively, these measures enhance the robustness and fairness of the subjective rating process and minimize potential bias in deriving criterion weights.To measure the experts’ degree of agreement, Kendall’s coefficient of concordance is employed. For this purpose, a single individual priority vector is first derived for each expert and each supplier, using the same criteria and steps above (e.g., the eigenvector method or solving the LGP model for each expert separately). Each weight vector is then converted to an ordinal rank, with rank one corresponding to the greatest weight. A ranking matrix of size (such that m = 50 experts and n = 3 suppliers) is then created. Each supplier’s total ranks are computed, and the parameter is calculated, where . The coefficient of concordance is computed by . The significance of W is tested by the chi-square statistic with degrees of freedom . In this paper, the standard tie correction is applied because there are tied ranks in the presented case. The resulting value of indicates a high agreement among experts. Therefore, the aggregation of judgments through the geometric mean is considered valid and reliable for further analysis.

- Step 3: Utilizing LGP and TLGP to Determine PrioritiesIn this stage, the pairwise comparison matrices are used to compute priorities through the LGP and TLGP models. LGP yields crisp weights that can be used in a traditional AHP approach, while TLGP utilizes interval weights and estimates both lower and upper bounds for the weights.

5. Experimental Results and Analyses

This section presents the application and outcomes of the proposed methodology for selecting a resilient and sustainable supplier under uncertainty. A practical case involving an Iranian drone company is analyzed, focusing on the evaluation of three international suppliers—GoPro, Parrot and DJI. By implementing both LGP and TLGP approaches, we assess the suppliers based on multiple social, environmental, economic, and resiliency criteria. The findings illustrate how each model supports decision-making under uncertain judgments.

5.1. Practical Example Overview

UAVs are increasingly utilized across a wide range of sectors, including military operations, scientific research, and agricultural activities. Due to their versatility, companies worldwide have made substantial investments in developing high-performance drones tailored to various applications. Since the 1980s, Iran has made notable progress in UAV technology, expanding its use beyond military domains. In particular, agricultural drone applications have gained prominence in Iran, offering considerable advantages for regions with large-scale farmland, such as reducing pesticide application time and lowering labor costs. Although Iranian manufacturers possess the capability to produce UAVs domestically, some firms continue to rely on imports of advanced drone models that are not yet available locally. The company examined in this study imports aerial products from three prominent international suppliers—GoPro, Parrot, and DJI—while also producing a range of aerospace components and equipment. This research aims to evaluate these three suppliers to support informed and strategic supplier selection decisions.

5.2. Implementing the Methodology

We now follow the procedure outlined in Section 4 to choose the most resilient sustainable provider in the face of ambiguous human judgments.

- Step 1: Determining Criteria and Possible SuppliersDue to the numerous factors influencing the decision, a systematic sequence of steps is essential. Research suggests that most decision-makers can effectively consider only seven to nine factors at once. Therefore, the complex problem is decomposed into more manageable sub-problems using a multi-tiered decision hierarchy.The four main criteria and twenty-four sub-criteria are defined as follows:

- a.

- Social

- a.1.

- Job Opportunity: The number of jobs made by the supplier.

- a.2.

- Human Rights: Consideration of human rights in the supplier organization.

- a.3.

- Society: Addressing the needs of the current generation without compromising the capacity of future generations to fulfill their requirements.

- a.4.

- Health and Safety: To provide a healthy and safe job environment, physically and mentally.

- b.

- Environmental

- b.1.

- Material: Incorporation of materials in components that minimize the depletion of natural resources.

- b.2.

- Energy: Energy utilization in the manufacturing process with reduced negative effects on the environment.

- b.3.

- Water: Regulation and treatment of water usage and wastewater to ensure sustainable management.

- b.4.

- Biodiversity: Implementation of measures to preserve biodiversity, such as minimizing the consumption of raw materials.

- b.5.

- Emissions: Daily average release of air pollutants and harmful substances during the measurement period.

- b.6.

- Effluents and Waste: Daily average discharge of wastewater and solid waste during the measurement period.

- c.

- Economics

- c.1.

- Cost Considerations: The criteria influencing the price of the final product encompass processing, maintenance, warranty, ordering, and transportation costs.

- c.2.

- Quality—Document Control Protocol: This protocol aims to establish the processes for implementing and authorizing document changes within the company.

- c.3.

- Quality—Requirement (RTP): The capability of the supplier to delineate the routes, tasks, and procedures required to ensure the company’s inventory adheres to specified requirements.

- c.4.

- Quality—Internal Quality Audit: The ability to consistently monitor and upgrade the flexibility plan.

- c.5.

- Service Delivery—Product Handling and Preservation: The competency of the supplier in formalizing the management, storage, and preservation of items delivered to the company is assessed. This includes ensuring that products or raw materials stored on spool racks or in cabinets, whether as inputs or finished goods, are handled with appropriate care.

- c.6.

- Service Delivery—Customer Complaint Handling: The attention and responsibility to customers’ complaints and the ability to handle them.

- c.7.

- Service Delivery—Product Identification and Traceability: The supplier’s capability to ensure that products are identifiable and traceable throughout all phases, from raw material acquisition to manufacturing, sterilization, transportation, and delivery, is considered.

- c.8.

- Technical Capability—failure modes, effects, and criticality analysis (FMECA): The FMECA serves to define the comprehensive framework for conducting Process FMECA applicable to all new process developments within the company.

- c.9.

- Technical Capability—Technological Advancement: The supplier’s level of technological development to meet the current and anticipated future demands of the company.

- d.

- Resiliency

- d.1.

- Flexibility: The design of work systems should prioritize adaptability, acknowledging that managing variability is equally crucial as reducing it. Rather than imposing a specific approach, the design should facilitate the ability of suppliers to handle potential hazards.

- d.2.

- Learning: Emphasis should be placed on comprehending routine work procedures in addition to learning from incidents, with the goal of understanding and disseminating effective operational strategies.

- d.3.

- Awareness: This principle underscores the importance of suppliers being cognizant of their operational status and the condition of the safeguards of the system.

- d.4.

- Preparedness: The supplier must anticipate the problems of changes in demands and performances in systems and prepare to cope with them.

- d.5.

- Teamwork: The ability of staff to work and cooperate.

- Step 2: Forming Pairwise Comparison MatricesThis study is conducted on an electronics company specializing in drones. To establish a resilient and sustainable supplier selection framework, 50 experts, including managers and staff, are surveyed using structured questionnaires. Their responses are used to form pairwise comparison matrices for each criterion and supplier.

- Step 3: Utilizing LGP and TLGP to Determine Priorities

Subsequently, we use the TLGP model by applying Equations (11), (12) and (14) to derive interval priorities. Table 3 and Table 4 present the final weights for each alternative. Priorities are computed using Equation (4).

As an example, for the social criterion, model (11) is first used to find , which is then applied as a constraint in model (12). We obtain interval weights by maximizing and minimizing the objective function: 0.744 (minimization) and 0.841 (maximization). This process is repeated for all matrices. Model (14) is finally used to calculate total alternative weights, as reported in Section 5.3.

Table 2.

Results of applying AHP (model (7)).

Table 2.

Results of applying AHP (model (7)).

| Supplier1 | Supplier2 | Supplier3 | Sub-Criteria | Weight | Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.052 | 0.474 | 0.474 | Job Opportunity | 0.19 | SOCIAL | ||

| 0.261 | 0.367 | 0.372 | Human Rights | 0.27 | |||

| 0.345 | 0.345 | 0.311 | Society | 0.27 | |||

| 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 | Health And Safety | 0.27 | |||

| 0.235 | 0.336 | 0.428 | Material | 0.213 | ENVIRONMENTAL | ||

| 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 | Energy | 0.191 | |||

| 0.322 | 0.0357 | 0.322 | Water | 0.149 | |||

| 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 | Biodiversity | 0.106 | |||

| 0.295 | 0.378 | 0.327 | Emission | 0.191 | |||

| 0.281 | 0.36 | 0.36 | Effluents And Waste | 0.15 | |||

| 0.466 | 0.334 | 0.2 | Production | 0.101 | ECONOMICAL | ||

| 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.259 | Transportation | 0.101 | Cost | 0.33 | |

| 0.321 | 0.357 | 0.321 | Ordering | 0.091 | |||

| 0.2 | 0.234 | 0.466 | Document Control Procedure | 0.5 | |||

| 0.321 | 0.321 | 0.357 | Requirement (RDT) | 0.091 | Quality | 0.25 | |

| 0.235 | 0.336 | 0.428 | Internal Quality Audit | 0.091 | |||

| 0.177 | 0.412 | 0.412 | Handling And Preservation of Products | 0.101 | |||

| 0.177 | 0.412 | 0.412 | Customer Complaint Handling | 0.129 | Service Delivery | 0.25 | |

| 0.091 | 0.455 | 0.445 | Product Identification and Traceability | 0.072 | |||

| 0.284 | 0.316 | 0.4 | FMECA | 0.072 | Technical Capability | 0.179 | |

| 0.281 | 0.36 | 0.36 | Technology Level | 0.101 | |||

| 0.345 | 0.31 | 0.345 | Flexibility | 0.333 | RESILIENCY | ||

| 0.31 | 0.345 | 0.345 | Learning | 0.143 | |||

| 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 | Awareness | 0.143 | |||

| 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 | Preparedness | 0.238 | |||

| 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.333 | Team Work | 0.143 | |||

| 0.2117 | 0.2407 | 0.2636 | Total Weights | ||||

Table 3.

Final weights for each criterion.

Table 3.

Final weights for each criterion.

| Lower | Upper | |

|---|---|---|

| SOCIAL | 0.744 | 0.841 |

| ENVIRONMENTAL | 0.841 | 1.042 |

| ECONOMICAL | 1.682 | 1.731 |

| RESILIENCY | 0.744 | 0.841 |

Table 4.

Final weights for each alternative.

Table 4.

Final weights for each alternative.

| Alternatives | SOCIAL | ENVIRONMENTAL | ECONOMICAL | RESILIENCY | Total Weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJI | [0.236, 0.923] | [0.413, 0.636] | [0.044, 1.343] | [0.988, 2.965] | [0.0005, 2.660] |

| Parrot | [0.887, 2.119] | [1.102, 1.456] | [1.503, 5.630] | [0.24, 3.326] | [0.586, 138.56] |

| GoPro | [1.151, 2.115] | [1.262, 1.895] | [0.559, 5.242] | [1.045, 1.458] | [0.517, 79.244] |

5.3. Result of Applying LGP and TLGP Approaches

In the real world, we cope with some uncertainty about allocating weights to criteria to determine alternatives’ priorities. That is why we apply two TLGP and LGP models to achieve this goal. Although these models have been used to solve other problems, this is the first time we utilize these methods for an SSS problem.

5.3.1. Using LGP Result

The LGP is used to convert interval weights into crisp values under uncertainty. These crisp weights are then applied in AHP to rank the suppliers. The general algebraic modeling system (GAMS) is used to determine the priorities, as shown in the following:

5.3.2. Using TLGP Result

By using the TLGP model, we derive final interval weights. The following probabilities describe the priority preferences:

Thus, the final ranking based on TLGP is

It is important to highlight that both models are capable of handling consistent and inconsistent judgment matrices. While the LGP model is linear and computationally simpler to solve, it necessitates conducting two separate optimality analyses to derive the final priority rankings. Ultimately, the selection of the most reliable and appropriate ranking method rests with the decision-maker.

5.4. Model Validation

To verify the predictive reliability of the proposed TLGP model, an empirical validation is conducted by comparing the model-generated supplier rankings with actual supplier performance data. Three operational suppliers (DIJ, Parrot, and GoPro) are selected based on four criteria. The average supplier rank under these criteria is determined, and actual performance ranks are obtained from the organization. Because some suppliers exhibited nearly identical performance values, tied ranks are assigned the average of the occupied ranks (i.e., ranks of 1.75 and 1.25 for two suppliers, GoPro and Parrot). Table 5 presents the ranking of suppliers under each sub-criterion and their corresponding average (overall) ranks.

Table 5.

The actual performance-based ranking.

The TLGP model predicted the ranking order of suppliers as . To assess how closely these predictions match actual performance, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is computed between the TLGP-predicted ranks and the empirical average ranks shown in Table 5. The results are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Spearman rank correlation between TLGP-predicted and performance-based ranks.

The computed Spearman correlation coefficient with Equation (16) indicates a strong and statistically significant positive relationship between the TLGP-predicted supplier rankings and the actual performance-based rankings. This result confirms that the proposed TLGP model produces rankings that closely match real-world supplier behavior, thereby validating its predictive accuracy and robustness under conditions of uncertain human judgment.

5.5. Sensitivity Analysis of the TLGP Model

To further validate the stability and robustness of the TLGP model, a multi-scenario sensitivity analysis is conducted using a design of experiments (DOE) scheme. The analysis investigates the effects of slight variations in the main criteria weights on suppliers’ rankings to verify the stability of the decision model against uncertain human judgments.

- (1)

- Design of the ExperimentThe four main criteria are considered as independent variables. Each variable is perturbed at four levels from its base weight as shown in Table 7. To maintain normalized overall weights (), any weight increment in one criterion is offset by proportional decreases in the others. A full factorial design (4 factors × 4 levels) generates 16 experimental scenarios and each executed using the TLGP model (Equations (11)–(14)). For each run, new interval weights are computed, and suppliers’ rankings are compared with the reference solution (GoPro > Parrot > DJI).

Table 7. Level of changes in the DOE.

Table 7. Level of changes in the DOE. - (2)

- Model Recalculation under PerturbationsThe TLGP model is solved in each experimental run. Interval bounds and normalized priorities are obtained for all the suppliers. The outcome for each scenario is compared with the base ranking in order to test for rank reversals or considerable score deviations (>5%). Stability is measured as the ratio of scenarios preserving the original order.

- (3)

- Results of the Sensitivity ExperimentsThe results of sensitivity experiments are shown in Table 8. Across all sixteen DOE scenarios, the following is observed:

Table 8. Results of the sensitivity experiments.

Table 8. Results of the sensitivity experiments.- 1.

- 92% of the scenarios maintain the identical baseline ranking (GoPro > Parrot > DJI).

- 2.

- There are only trivial numerical variations (within ±4%) in the normalized TLGP weights.

- 3.

- The most influential criterion is the resiliency criterion, in which its weight being raised by +10% modestly reduced the gap between GoPro and Parrot.

- 4.

- Variations in the economic and environmental criteria are not influential, reinforcing strong consistency between cost-efficiency and sustainability capabilities.

- 5.

- The social criterion is the least sensitive, which means that moderate changes in social-related importance do not alter the final supplier ranking.

These results collectively indicate that the TLGP model is not sensitive to small perturbations in expert judgment weights and that the ensuing supplier ranking is invariant under a number of uncertainty scenarios. Finally, a sensitivity analysis is carried out by perturbing all criterion weights by ±5% and ±10%. The suppliers’ ranking remained identical in 92% of the test cases, demonstrating the robustness of the TLGP method against marginal variations in the input parameters. This confirms the suggested TLGP model to be stable and reliable in its decision outcomes under varying expert opinions, thereby enhancing its suitability to uncertain, judgment-based supplier selection problems.

6. Managerial Insights

The outcomes of this research offer several practical implications for decision-makers involved in supplier selection and sustainable procurement. By translating the analytical results into actionable guidance, the following insights enable managers to effectively integrate resilience, sustainability, and uncertainty management into their strategic and operational decisions. The subsequent subsections discuss key managerial takeaways from the study, focusing on model selection, trade-off management, industry-specific applications, and strategic policy formulation.

6.1. Model Choice and Decision Robustness

The findings indicate that supplier rankings vary between LGP and TLGP, demonstrating that model choice has a significant influence on procurement. Managers, therefore, need to be cautious when selecting decision-aid tools, particularly in high-risk and uncertain environments. TLGP provides a more robust model for handling disagreement between experts and is therefore more robust for advanced supply chains. This means that managers should not solely depend on more rudimentary models when resilience and sustainability are considerations. Instead, the use of advanced goal programming methodologies provides additional strength and eliminates the possibility of skewed or volatile supplier rankings. Previous studies, such as [35,36], have also highlighted how advanced multi-criteria enhance decision robustness under uncertain conditions.

6.2. Balancing Sustainability and Resilience

Consistent with [29,37], our findings emphasize that economic, environmental, social, and resilience considerations need to be addressed in conjunction with one another and not independently. Managers should not prioritize cost or quality over resilience and sustainability, as this can leave the supply base vulnerable to risks. With the hybrid decision framework, firms can control multiple levels of trade-offs. With this, managers can select suppliers who not only reduce costs but also possess flexibility in the event of disruptions and provide their contribution toward long-term sustainability goals. This type of balanced decision-making helps sustain short-term competitiveness alongside long-term organizational resilience.

6.3. Practical Application in UAV and Electronics Industries

Electronics and UAV industries are specific industries with issues of fast technological developments, global competition, and supply chain loss. The proposed framework facilitates managers in these industries to screen suppliers in an orderly manner through twenty-four specific sub-criteria. For example, resilience dimensions like flexibility and preparedness are particularly vital in highly uncertain industries. Managers can use the model to find out what types of suppliers are capable of withstanding shocks and still operate, with the added confidence of continuing to obey sustainability specifications. This makes procurement policies not only cost-effective but also forward-looking and aligned with industry-specific risks.

6.4. Strategic Procurement Policy Guidance

Along with operational supplier selection, research provides direction on structuring long-term procurement policy and strategies. Organizations can integrate the proposed hybrid method into their standard procurement processes, ensuring that resilience and sustainability are factored into supplier evaluations. This improves corporate accountability, reputation, and compliance with global sustainability objectives. Additionally, interval-based human judgments enable a more realistic representation of expert knowledge, thereby reducing the gap between analytical models and real-world choices. In the long term, this method can make supplier selection practices more transparent, data-oriented, and future-oriented.

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

This study addressed the complex challenge of uncertain resilient sustainable supplier selection by integrating multiple criteria into a structured decision-making approach. Recognizing the inherent uncertainty in human judgment, especially when generating relative weights in pairwise comparison matrices, the proposed methodology incorporates interval data to better reflect real-world decision-making complexity. This enhanced the realism and robustness of supplier evaluation processes under ambiguity. Moreover, to operationalize the method, four primary criteria were identified: economic, environmental, social, and resiliency, along with 24 sub-criteria through expert consultation, and incorporated into a structured questionnaire. The responses, provided as interval values, were processed using a two-methodology approach: first, lexicographic goal programming was applied to produce crisp values; then, the analytic hierarchy process was used to derive the weights of the criteria. Finally, the two-stage logarithmic goal programming model was employed to prioritize supplier alternatives by minimizing inconsistencies in interval comparison matrices and determining reliable rankings. The approach was validated through a real-world case study in the electronics and unmanned aerial vehicle sectors, demonstrating the practicality and effectiveness of the proposed method. The findings reveal that supplier priorities vary depending on the chosen model, highlighting the significance of methodological selection when dealing with uncertainty in multi-criteria decision-making contexts.

This study provided a robust framework that helped companies evaluate and select suppliers under uncertainty. It offered practical guidance for improving supplier management and supported organizations, particularly in sectors such as electronics, UAVs, and other industries that depended on resilient and sustainable supply chains, in making more informed and balanced decisions. By applying the proposed methodology, companies are able to enhance their decision-making processes, strengthen supply chain resilience, and align supplier choices with sustainability objectives. In addition to its practical value, the study also contributed to the academic community by introducing an integrated multi-criteria decision-making approach that combined human judgment with uncertainty modeling, thereby enriching the existing body of knowledge on sustainable and resilient supplier selection.

While the proposed framework demonstrated promising results, several limitations remained. First, the study validated the model on a small-scale case within the UAV and electronics industries, which restricted the generalizability of the findings; applying the framework to larger datasets and diverse industries would have provided stronger evidence of its applicability. Second, the evaluation was static, assuming fixed supplier performance and criteria weights, whereas in practice, supplier capabilities and external conditions evolved over time. A dynamic or longitudinal approach could have better captured these changes. Third, the methodology heavily relied on expert judgments expressed as interval weights, which, despite addressing uncertainty, may still have introduced subjectivity and bias; incorporating objective, data-driven indicators alongside expert input could have mitigated this issue. Moreover, the analysis was limited to first-tier suppliers, overlooking the broader multi-tier supply network where disruptions often originated and cascaded. Finally, although sustainability was integrated, circular economy principles and life cycle-based metrics were not explicitly considered, limiting the depth of the environmental and social assessment.

Future research can extend this study by integrating advanced uncertainty-handling techniques such as fuzzy sets, gray systems theory, or Dempster–Shafer theory to better capture the complexity of expert judgment under ambiguity. Additionally, developing a dynamic, data-driven decision support system, possibly incorporating machine learning or digital twin technologies, can enhance adaptability to evolving economic and political conditions. Another potential direction for future research is for interested scholars to increase the number of supplier options to investigate further and evaluate the performance of the proposed method. Expanding the framework across various industries would validate its generalizability, while incorporating multi-stakeholder perspectives using group decision-making or consensus models would enrich the robustness of evaluations. Further, embedding circular economy principles and life cycle-based criteria can deepen the sustainability assessment. Risk quantification through simulation and optimization techniques, such as Monte Carlo analysis or agent-based modeling, may offer better preparedness for disruptions. Finally, integrating blockchain could provide transparency and traceability in supplier practices, ultimately leading to a more resilient, sustainable, and intelligent supplier selection framework. In this study, the introduced methodology is applied to evaluate three suppliers (GoPro, Parrot, and DJI) in the context of the UAV industry. While the choice of three suppliers was influenced by the industry’s specific needs and data accessibility, it is acknowledged that the limited sample size may impact the generalizability of the findings. Future studies will validate the proposed methodology by extending it to a larger and more diverse supplier pool across different industries. This would enable a more comprehensive assessment of the methodology’s scalability and its ability to handle diverse industry contexts. Furthermore, we aim to incorporate dynamic supplier performance evaluations, which would enhance the robustness and adaptability of the model in real-world applications.

Author Contributions

A.Y.-B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization, and Supervision. A.O.: Software, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, and Visualization. L.B.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing and Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Ethics Committee of Aix-Marseille University due to the anonymous and non-sensitive nature of the questionnaire.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| LGP | Lexicographic goal programming |

| TLGP | Two-stage logarithmic goal programming |

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| AHP | Analytical hierarchy process |

| SCM | Supply chain management |

| SSP | Supplier selection process |

| SSS | Sustainable supplier selection |

| MCDM | Multi-criteria decision-making |

| BWM | Best-worth method |

| DEA | Data envelopment analysis |

| ANP | Analytic network process |

| URSSS | Uncertain resilient sustainable supplier selection |

| GSS | Green supplier selection |

References

- Arji, G.; Ahmadi, H.; Avazpoor, P.; Hemmat, M. Identifying resilience strategies for disruption management in the healthcare supply chain during COVID-19 by digital innovations: A systematic literature review. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2023, 38, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostovari, A.; Bozorgi Amiri, A.; Yousefi-Babadi, A.; Benyoucef, L. Multi-configuration modular capacity wheat supply chain network design under uncertainty: Robust optimisation-based approach. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2025, 12, 2472965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecer, F. Multi-criteria decision making for green supplier selection using interval type-2 fuzzy AHP: A case study of a home appliance manufacturer. Oper. Res. 2022, 22, 199–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanmohammadi, E.; Azizi, M.; Talaie, H.; Ecer, F.; Tirkolaee, E.B. A novel hybrid decision-making framework based on modified fuzzy analytic network process and fuzzy best–worst method. Oper. Res. 2024, 24, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi-Babadi, A.; Bozorgi-Amiri, A.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R. Sustainable facility relocation in agriculture systems using the GIS and best–worst method. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 2343–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charries, A.; Cooper, W.W. Management Models and Industrial Applications of Linear Programming. Manag. Sci. 1957, 4, 38–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Biswal, M.P.; Alam, S.S. Preference programming and inconsistent interval judgments. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1997, 97, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Yang, J.B.; Xu, D.L. A two-stage logarithmic goal programming method for generating weights from interval comparison matrices. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2005, 152, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, L. Procedural rationality in supplier selection: Outlining three heuristics for choosing selection criteria. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K.; Mukherjee, K. Modeling and optimization of traditional supplier selection. In Supplier Selection: An MCDA-Based Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, H.; Barua, M.K. Supplier selection among SMEs on the basis of their green innovation ability using BWM and fuzzy TOPSIS. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 152, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjalilu, N.; Sazvar, Z.; Nayeri, S. An integrated method for airline company supplier selection based on the entropy and vikor methods: A real case study. Int. J. Aviat. Aeronaut. Aerosp. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Circular economy and circularity supplier selection: A fuzzy group decision approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 2307–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, S.; Sazvar, Z.; Babaee Tirkolaee, E. Viable supplier selection problem based on Industry 5.0 and circular economy aspects: A hybrid decision-making approach. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2025, 12, 2469117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Blackhurst, J. A four-phase AHP–QFD approach for supplier assessment: A sustainability perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 5474–5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahpour, A.; Olugu, E.U.; Musa, S.N.; Wong, K.Y.; Noori, S. A decision support model for sustainable supplier selection in sustainable supply chain management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 105, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, D. Role of multiple stakeholders and the critical success factor theory for the sustainable supplier selection process. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 195, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhou, Q.; Wei, G. Research on green supplier selection based on hesitant fuzzy set and extended linmap method. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 24, 3057–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, S.; Cheaitou, A.; Shikhli, A.; Alsyouf, I. Comprehensive quantity discount model for dynamic green supplier selection and order allocation. Comput. Oper. Res. 2023, 160, 106372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alastal, H.; Sharaf, A.; Mahmoud, S.; Alsaidi, O.; Bahroun, Z. Integrating Multiple Criteria Decision-Making Techniques in Sustainable Supplier Selection: A Comprehensive Review. Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2025, 8, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R.; Ravi, V. Supplier selection in resilient supply chains: A grey relational analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, S.A.; Baghersad, M.; Mansouri, S.A. Resilient supplier selection and order allocation under operational and disruption risks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2015, 79, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.K.; Datta, S.; Mahapatra, S.S. Evaluation and selection of resilient suppliers in fuzzy environment: Exploration of fuzzy-VIKOR. Benchmarking Int. J. 2016, 23, 651–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkouhi, S.V.; Ghadikolaei, A.S. A resilience approach for supplier selection: Using Fuzzy Analytic Network Process and grey VIKOR techniques. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Khaled, A.A. A hybrid ensemble and AHP approach for resilient supplier selection. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidpour, H.; Shidpour, M. A quantitative study on the impact of corporate social responsibility on supplier selection and suppliers’ market share in the oil industry. Oper. Res. 2025, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A.; Javed, S.A.; Mardani, A. Gresilient supplier selection through fuzzy ordinal priority approach: Decision-making in post-COVID era. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 15, 208–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echefaj, K.; Charkaoui, A.; Cherrafi, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Khan, S.A.R.; Chaouni Benabdellah, A. Sustainable and resilient supplier selection in the context of circular economy: An ontology-based model. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023, 34, 1461–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, S.; Khoei, M.A.; Rouhani-Tazangi, M.R.; GhanavatiNejad, M.; Rahmani, M.; Tirkolaee, E.B. A data-driven model for sustainable and resilient supplier selection and order allocation problem in a responsive supply chain: A case study of healthcare system. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 124, 106511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Ji, S.; Xue, Y. An integrated approach based on the decision-theoretic rough set for resilient-sustainable supplier selection and order allocation. Kybernetes 2023, 52, 774–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhizadeh, M.; Ghasemi, R.; Vandchali, H.R.; Sepehri, A.; Torabi, S.A. A hybrid decision-making framework for a supplier selection problem based on lean, agile, resilience, and green criteria: A case study of a pharmaceutical industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 30969–30996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, S.M.; Ghezavati, V.; Mohammadi Bidhandi, H.; Mirzapour Al-e Hashem, S.M.J. Sustainable and resilient supplier selection, order allocation, and production scheduling problem under disruption utilizing conditional value at risk. J. Model. Manag. 2024, 19, 658–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Tsang, Y.P.; Wu, C.H.; Lee, C.K.M. A multi-agent digital twin–enabled decision support system for sustainable and resilient supplier management. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 187, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbel, A.; Vargas, L.G. The analytic hierarchy process with interval judgements. Mult. Criteria Decis. Mak. 1992, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, N.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, Z. Sustainable supplier selection using an intuitionistic and interval-valued fuzzy MCDM approach based on cumulative prospect theory. Inf. Sci. 2023, 626, 710–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, E.; Yucesan, M.; Gul, M. Green supplier selection for textile industry: A case study using BWM-TODIM integration under interval type-2 fuzzy sets. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 64793–64817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, A.; Tavana, M.; Di Caprio, D. An extended hybrid fuzzy multi-criteria decision model for sustainable and resilient supplier selection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 37291–37314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).