Abstract

The European Union (EU)’s commitment to promoting social, economic, and environmental sustainability in the agri-food system prompts this study to recognize young farmers as essential stakeholders in maintaining agricultural productivity and a steady supply of healthy food. It addresses their under-representation in practice and research, as Romania transitions to a greener agricultural model, particularly regarding fertilizer use. Data were collected in 2025 targeting Romanian farmers aged up to 45 years. The research mapped fertilizer usage practices and perceptions, awareness of environmental measures, and access to EU subsidies, utilizing descriptive and inferential statistics. More precisely, this aims at identifying those behavioral determinants influencing fertilizer reduction among young Romanian farmers, with a focus on sustainability, food safety, and security implications. The findings reveal that while young Romanian farmers show potential for adopting sustainable practices, their chemical fertilizer usage is complex, as 21% reported reductions, 49% maintained, and 30% increased their use of chemical fertilizers. Despite their awareness of environmental impacts, their practices are often misaligned with the sustainability objectives of the EU and the Farm to Fork Strategy, highlighting the intersection of education, policy support, and broader agricultural realities necessary to achieve a more resilient and sustainable food system in Romania and beyond. The results are intended to inform targeted policy interventions and capacity-building programs that can better align young farmers’ actions with EU sustainability goals.

1. Introduction

1.1. Macro-Level Framing—General European and Global Contexts

The European Union’s Farm to Fork (F2F) Strategy is a central element of the European Green Deal (GD), which seeks to reshape the EU’s agri-food system in pursuit of sustainability, ecological resilience, and health. On an overall, this approach to food production and consumption is embedded in broader ecological and health contexts as it considers the holistic health of the entire agri-food system and consumers alike. First and foremost, as noted by the European Commission [1], the F2F Strategy aims to establish agri-food systems that are not only sustainable but also responsive to the contemporary challenges posed by health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. By prioritizing overall sustainability, the F2F strategy also addresses the growing challenges posed by food insecurity and dietary deficiencies stemming from industrial agricultural practices, geo-political and populational contexts. More specifically, core changes are envisioned in how food is produced, processed, and consumed across Europe, stressing the necessity for the development of inclusive and equitable agri-food systems for all segments of the EU population [2], for their food to be safe, healthy, and affordable [3]. This is particularly important in light of recent global events, such as the war in Ukraine, that have exacerbated food access and quality issues, revealing vulnerabilities in the food system alongside the dependency on expensive chemical raw materials originating from unstable markets, such as Russia.

This study is conceptually grounded in Sustainability Transition Theory (STT), which views agricultural sustainability as a muti-level socio-technical transformation driven by interaction between policy and institutional frameworks, technology innovation and markets, as well as behavioral change [4]. In the agri-food domain, applying this multi-level perspective [5] highlights how policy frameworks (such as the F2F) and social actors (farmers) interact to reshape agricultural transitions, determining the alignment of practice with sustainability goals [6]. There are multiple key objectives to achieving EU sustainability desiderata. For the scope of this paper, one of the most relevant issues is to reduce reliance on chemical fertilizing inputs. This call is motivated by the need to address the significant detrimental health and environmental effects, which have been exacerbated by the intensive agricultural practices characteristic of the past decades, such as nutrient runoff and overall watershed and soil pollution. To this end, the F2F strategy stipulates a reduction in EU chemical fertilizer use by 20% by the year 2030 [1]. In their place, the strategy promotes the use of organic fertilizers and sustainable farming techniques, advancing the EU’s commitment to enhancing biodiversity and soil health. In the current global framework, EU agricultural practices are aimed at aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established by the United Nations in 2015 in areas such as responsible consumption and production patterns (Goal 12) [3]. The SDGs also call for efforts to significantly reduce food waste and loss, as well as nutrient losses in agricultural systems, similar to the GD strategy that aims to reduce these losses by 50% [7].

Under EU Regulation (EU) 2019/1009, effective July 2022 [8]—the Fertilizing Products Regulation—the distinction between chemical (inorganic) and organic fertilizers is legally codified, reflecting their origin, composition, and intended use. Chemical (or inorganic) fertilizers are defined as products composed of mineral products manufactured through industrial chemical processes, typically providing nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in immediately available, soluble forms. In contrast, organic fertilizers are derived from biodegradable plant, animal, or microbial residues—such as compost, manure, or digestates—and release nutrients more gradually as they decompose. The regulation further introduces a third category: organo-mineral fertilizers, which combine organic matter with synthetic nutrients. This is the newest legislation setting out uniform requirements for safety (including contaminant thresholds such as for heavy metals), nutrient content, labeling, and product functionality across the European Single Market. The legal framework facilitates the free movement of compliant fertilizing products while promoting sustainable nutrient management practices aligned with the EU’s Green Deal, but also Circular Economy objectives. Comprehensively, this means there is an overall paradigm shift in agriculture that involves nutrients being used efficiently, helping to minimize waste and enhancing the ecological resilience of food production systems, including agricultural practices that involve nutrient-dense crops, ultimately producing healthier food.

1.2. Meso-Level Framing-European Policy Context, National Relevance, and State-of-Play

The conceptual lens that connects policy implementation with compliance models (namely linking EU-level policy design to national execution and local farmer behavior) is paramount, as EU agri-environmental policies only shift practices when policy design aligns with national implementation and the motivations and capacities of farmers facing everyday trade-offs. Classic implementation and compliance data help explain when and why farmers adopt, partially adopt, or resist measures like fertilizer reduction or eco-schemes, shaped by intertwined motivational, institutional, and behavioral factors. Evidence from compliance theory shows that farmers’ adherence to EU environmental measures reflects a mix of calculated (cost–benefit), normative (values and stewardship), and social (peer and market expectations) motives, complemented by their awareness and capacity to comply [9].

Policy-wise, European-level initiatives following the F2F and GD principles include multiple documents, of which the Communication from the Commission ensuring availability and affordability of fertilizers (2022) [10] can be mentioned, which fosters collaboration among farmers to adopt greener practices, encourages nutrient recycling and carbon sequestration in the soil. The Communication (2022) [10] stipulates that the European Commission in partnership with Member States should facilitate the broad adoption of sustainable agricultural practices, including the development of nutrient management plans, improvement of soil health, precision farming techniques, organic agriculture, and the integration of leguminous crops into crop rotation systems, which have the potential to reduce both the sector’s reliance on imported natural gas and its overall carbon footprint. Furthermore, the European Commission promotes investment in low-emission technologies for fertilizer production by encouraging Member States as part of a broader strategy to decarbonize agricultural inputs. To ensure effective implementation, farmers are supported through tailored advisory services and training programs, complemented by digital tools such as the Farm Sustainability Tool for Nutrients (FaST) [11], a platform used by regions in Italy, Spain, Estonia, as well as more recently, Belgium, Romania, Slovakia and Greece.

Subsequently, progress has been made, with European Commission data [12] revealing a decrease in the use of chemical fertilizers (of which the most common are inorganic ones like nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium-based) for 2023. This represented a 3.7% year-on-year reduction and a cumulative decline of 20.5% from the relative peak in 2017. Farmers across the EU used 8.3 million tons of nitrogen fertilizer, 3.8% less than in 2022. Similarly, agricultural use of phosphorus fertilizers amounted to 0.9 million tons in 2023, 2.2% less than in the previous year. This trend is country-wide, with sharp decreases from 2013, in all EU Member states except a few agricultural producers in Northern or Central-Eastern Europe, such as Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Croatia, Estonia, Bulgaria and Romania.

Studies show that regional disparities exist as different countries may pursue various pathways to meet these EU-wide goals. For instance, Poland’s adaptations to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and F2F suggest that while eco-schemes can enhance farmer engagement in environmental stewardship, they also face challenges in ensuring that production levels remain competitive [13]. Conversely, other studies note France’s successful implementation of agri-environmental schemes, thus highlighting the potential for such programs to harmonize economic and ecological outcomes and revealing the importance of targeted policies that align with local farming contexts [14]. Such practices have led to an overall reduction in the use of fertilizers over the last decade in France, following the broader EU trend. However, as EU data reveal, France remains the highest EU consumer of inorganic fertilizers, especially nitrogen (1.7 million tons) [12], due to its vast agricultural area and extensive agricultural production.

Despite significant harmonizing legislative initiatives -such as the Emergency Ordinance No. 121/2022 on establishing measures for the placing on the market of certain fertilizing products [15], a 2025 updated version of a List of Chemical and Biological fertilizers Authorized for Use in Agriculture and Forestry in Romania [16] and practical approaches, subsequent to the EU F2F and GD provisions—Romania reveals a stark increase in its use of both nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers. According to Eurostat data (2025b) [12], nitrogen fertilizer use exhibited a provisional increase from 344 thousand tons in 2013 to 463 thousand tons in 2023. While a marginal decline was observed in 2014, the overall trajectory over the subsequent years reflects a consistent upward trend. Similarly, phosphorus fertilizer usage in Romanian agriculture exhibited an almost twofold increase, rising from 49 thousand tons to 91 thousand tons between 2013 and 2023—contradicting the anticipated and needed reduction projected under the F2F strategy.

This further shows that diverse member states have demonstrated varying degrees of response to these ecological strategies so far, largely shaped by their individual agricultural contexts, resource availability, and political frameworks. Broadly, innovative initiatives reflect a growing trend towards sustainable agricultural practices that aim to mitigate the reliance on chemical fertilizers proposed by GD and F2F. For instance, nations like Ireland [17], Poland [18,19], Italy [20,21], the Netherlands [22], Spain [23,24,25], even Romania [26] and others have pioneered the implementation of integrated farming approaches that combine eco-friendly technologies. These include the production and use of bio-based fertilizers [27], green manures and organic fertilizers, including biochar and composted pelletized poultry litter [28], biogas production from organic waste and overall arable and livestock farm adaptation to sustainability criteria within collaborative frameworks involving different stakeholders, such as R&D, policy-makers and farmers.

1.3. Theoretical and Empirical Gaps—Problem Identification

While the F2F Strategy presents a compelling case for reducing chemical fertilizer dependency, there are still significant economic implications to consider. Decreasing fertilizer application across the EU agricultural sector is projected to lead to potential productivity reductions of approximately 12% [29]. According to Baquedano et al., these agricultural input reductions could lead to GDP losses and higher market prices for food products as decreases in agricultural output become more pronounced under stricter regulations, threatening market prices and ultimately, consumer welfare [30]. This requires that Member States not only focus on immediate reductions in fertilization but also on long-term strategies that involve investment in research and development for new sustainable technologies to mitigate any adverse economic impacts and maintain competitiveness in an evolving market landscape, particularly as EU member states vary in their agricultural productivity and economic resilience [31]. This empirical evidence across the EU demonstrates that participation in such schemes varies with economic incentives, farm structure, risk preferences, knowledge access, and attitudinal factors, reflecting the heterogeneous capacities of farmers to engage in sustainability transitions [32,33].

The F2F strategy aspires to simultaneously empower farmers, consumers, and improve public health outcomes. In this array, farmers are essential stakeholders in the maintenance of agricultural productivity, environmental sustainability and the consistent supply of healthy food within the European Union. As primary producers, their chemical fertilizer reduction and further transition to sustainable agricultural practices that enhance food security, public health, societal well-being and environmental integrity are paramount.

Also, younger farmers, specifically those under the age of 45, represent a significant demographic in the agricultural landscape of the EU, but not necessarily numerically- only 20% of farm managers in the EU are under 45 years of age [34], with only 11.9% under 40. Their relevant part in the social dynamism and the revitalizing of rural regions complements young farmers’ importance for core agricultural and economic activities. Moreover, their importance revolves around the “young farmer problem”, highlighting a concerning trend of low generational renewal rates in agriculture across the EU [35]. Young farmers are defined, first within the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) core Regulation 2021/2115 establishing financial support [36] as a person setting up for the first time as head of an agricultural holding, who is no more than 40 years old (before turning 41) and who possesses adequate occupational skills and competence. However, young farmers are also considered from the perspective of the last EU census on farm managers [34], which sets out to include young farmers solely under 35 years of age, with farm manager age categories established to be of less than 35 and 35–44 years of age, thus only partially overlapping the aforementioned Regulation.

Despite multiple initiatives at the EU level under the CAP, young farmers remain underrepresented both in practice and in research. Thus, this study aims to help young Romanian farmers to be viewed, considered, motivated and supported in this EU green and more sustainable agricultural transition. Their selection was essential, as they are meant to represent the future generation in Romanian agriculture, with higher access to education, technology and broader world and European views. Additionally, Romanian farmers are relevant in the broader European context, with Romania playing an important role in EU agriculture (7th in terms of agricultural land and 8th in terms of standard output at the EU level) [37].

1.4. Research Aim, Objectives and Questions

To this end, the current study sets out to investigate the degree of young farmers’ knowledge alongside their current and future behavior towards broader sustainability goals. This investigation particularly focuses on the use and reduction of chemical fertilizers, as well as the potential adoption of organic alternatives in alignment with the F2F strategy within the broader GD. Furthermore, it aspires to reveal the perspectives that have influenced the commitment of young farmers to these sustainability goals or lack thereof.

The following research questions were envisioned:

- Q1: What are young farmers’ views and behavior towards the reduction of chemical fertilizer and the increase in organic fertilizer use and practices in the context of the F2F and GD strategies?

- Q2: How can their behavior be explained alongside their knowledge and beliefs regarding sustainability desiderata and the provision of healthy food for the EU population?

- Q3: What means of information, education, training and procurement are used to encourage farmers to align with the provisions of fertilizer reduction under the F2F strategy?

The study is structured into 6 parts, with the Introduction outlining the European agri-food context under the F2F and GD environmental provisions towards farmers’ chemical fertilizer reduction, matters supported and discussed in Section 2, the Literature review along the lines of European, national and farmer regulatory and practical characteristics. Section 3 includes the Materials and Methods part with a focus on sample size and characteristics, and the statistical methods employed. Section 4 aptly follows with the Results, mainly focused on farmers’ practical outcomes related to fertilizer use and their reasons and principles for this use, detailed and analyzed in the Discussions (Section 5) in farmers’ specific context and against F2F and GD mandates, other initiatives and research in the field. The paper ends with a Conclusions (Section 6) section outlining the theoretical and practical relevance of the study, as well as its limitations.

2. Literature Review

A comprehensive review was conducted that highlighted the emerging research directions in the context of the European GD, suggesting that the implementation of policies focused on reducing fertilizer use and nutrient loss is critical for achieving environmental sustainability and climate mitigation goals [38]. Studies also show that EU financial incentives have led to significant advancements in technology adoption that allow for the careful application of fertilizers, optimizing their usage and thus minimizing waste, while increasing both the economic competitiveness and environmental performance. This has been exemplified by German farms, while in the Netherlands, a focus on resource efficiency and precision farming has also allowed farmers to achieve sustainable production levels despite stricter nutrient management policies [7,39]. Such models need to be closely examined by other member states, particularly as they develop their respective agricultural policies to align with EU directives.

In this respect, as noted in various studies [40,41], achieving synergies across landscapes to optimize both farm economic viability and ecological balance remains a critical challenge within EU agricultural frameworks, due to significant knowledge gaps and variable implementation across regions due to differences in agricultural structures and financial incentives. A policy-oriented review barely preceding the F2F [42] highlights that integrating behavioral insights—through tailored advice, peer learning, and simplified compliance—can bridge the gap between EU-level sustainability ambitions and local on-farm practices. Also, with innovative techniques being implemented, there is still uneven dissemination of knowledge between science, policy-making and farmer communities regarding sustainable practices undertaken that critically foster or even enhance the disparities in success across Member States.

Micro-Level Framing-Young Farmers as Agents of Change

Traditionally and more recently, the EU’s CAP and the F2F, alongside national legislation, have been specifically designed to support farmers in producing healthier food options while simultaneously addressing environmental concerns through targeted subsidies and support for sustainable practices. This is consistent with farmers’ public opinion that they require substantial support from the EU in the transition towards sustainable practices, as mandated by policies like the F2F strategy. This clearly reflects from studies advocating for the development of EU green policies and subsidies aimed at fostering organic farming and enabling farmers to offset the costs associated with conversion to more sustainable production methods, such as organic or regenerative agriculture [43].

All momentous innovations in agricultural practices have prompted debates among farmers regarding the balance of productivity and food quality. Evidence suggests that historically, the CAP has significantly contributed to heightened productivity following the intensification of agricultural practices over the past decades. However, its complexities and bureaucratic nature can inhibit farmers’ ability to respond effectively to market demands for nutrient diversity and overall nutritious food [44]. This is because agricultural policies and farmers have prioritized economic efficiency over nutritional and environmental outcomes for a long time, and farms may run the risk of being productive but unable to align with the new public health and environmental objectives.

In this context, research argues that without clear support mechanisms—including financial incentives for resource acquisition, education [45], and infrastructure improvements—many farmers may struggle to meet the environmental standards outlined in the F2F policy [39] and successfully navigate this transformation while maintaining economic viability amidst increasing regulatory burdens. In their recent study on Swedish dairy farming, Oyinbo and Hansson (2024) [46] overtly highlight the need for clear economic interventions to aid farmers in navigating the complex shift towards sustainability goals put forth in the F2F Strategy as do Hoes and Aramyan (2022) [47] discussing the significant external pressures faced by Dutch dairy farmers due to EU regulations aimed at achieving these sustainability objectives. Studies argue, in this respect, that, in order for these challenges to be tackled, new entrants are essential to generational renewal, which in turn helps with resilience, innovation adoption, and environmental sustainability. Because newcomers and new successors may be more willing to adopt newer practices, to question older norms, or bring in fresh perspectives (e.g., concerning environmental practices) compared to older, more established farmers [48]. Thus, supporting them well can help drive the sustainability goals embedded in CAP, GD, and F2F.

One study in particular [49] provides comparative economic data for the EU and Romania, showing that Romanian farms—especially small and semi-subsistence ones where many young farmers begin—face weaker profitability, limited liquidity, and fragile investment capacity, highlighting the tension between sustainability ambitions and economic realities. This has direct sustainability implications: young farmers may recognize the importance of environmental practices, but financial constraints often push them toward conventional methods with higher short-term returns, prompting the need for stronger, better-targeted CAP and national supports if young farmers are to lead the transition toward greener practices.

Thus, a further shift was envisioned, specifically with the introduction of eco-schemes under the CAP, beginning in 2023, further supporting environmentally friendly practices by allowing farmers to allocate part of their direct payments towards sustainable farming initiatives. Research has shown that these new CAP measures could lead to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions across the EU while simultaneously encouraging farmers to maintain production levels [13]. Additionally, other recent studies indicate that over the past decade, CAP subsidies have been essential in shifting the agricultural landscape from conventional farming methods towards more environmentally sustainable practices, including the increased allocation of resources towards organic farming [50].

It is generally valid that, discursively, farmers view the push towards organic and diversified farming as positive. But further research has highlighted farmers’ views related to the CAP, where, despite the EU’s intent to support farmers in this green transition, there are feelings of dissatisfaction surrounding subsidy distributions and bureaucratic complexities among farming communities [51]. This disparity often results in protests and calls for reform that better address the needs of diverse farming models, reinforcing that a comprehensive understanding of farmer perspectives is critical for shaping effective, healthy food security strategies in the EU.

The reduction of chemical fertilizers, as envisioned under the EU F2F Strategy, must also be approached through a dual lens of food safety and food security, ensuring that sustainability objectives do not compromise the safety, availability, or affordability of food. Beyond the environmental rationale, fertilizer reduction directly intersects with food safety, as excessive chemical inputs can lead to soil contamination, nitrate accumulation, and residues that pose health risks to consumers and ecological systems. At the same time, abrupt or poorly supported transitions may endanger food security by lowering yields and destabilizing production, especially in regions where young farmers lack access to alternative inputs or technologies. Therefore, implementing the F2F provisions requires integrated policies that promote the safe use of fertilizers, enhanced farmer education, and monitoring systems to maintain productivity while minimizing health risks. As emphasized by Chomać-Pierzecka and colleagues, sustainable development and thus agri-food transitions must embed safety as a multidimensional concept [52]. It should encompass not only consumer and environmental safety, but also the economic and operational security of producers navigating policy-driven change. This approach ensures that sustainability goals align with both public health protection and the long-term resilience of the food supply chain.

Herrera et al. [53] explore the adoption of circular agronomy solutions among EU farmers—practices such as nutrient recycling, manure valorization, composting, by-product reuse, and closed-loop nutrient cycles. These practices extend sustainability beyond the conventional dichotomy of “organic vs. conventional,” aligning with broader EU sustainability goals by reducing dependency on chemical inputs and lowering environmental externalities. However, it is clear that farmers’ role in achieving EU sustainability goals depends on a mix of structural (economic, policy) and behavioral (knowledge, risk perception, norms) determinants.

The relevance of our study on young farmers’ perspective and behavior lies in the belief that sustainability transitions in farming are not just about compliance with EU targets but about creating enabling conditions—financial, social and educational—that make environmentally friendly practices a rational choice for farmers. Also, to our knowledge, research on European farmers’ behavior and perspectives towards sustainability goals in view of the GD and F2F strategies in agriculture has been scarce, with very few particularly focused on young farmers and even fewer on chemical fertilizer reduction. For one, an extensive empirical study has investigated the ways in which a subset of young, educated farmers returning to rural areas in Italy [54] are implementing conservation and resilience strategies to support the operational efficiency of their business activities, but also contributes to expanding business opportunities and preserving the agricultural landscape. Even more overtly connected to European strategies, research by Balezentis et al. (2020) [55] investigated the impact of support systems available to young farmers, encompassing both direct payments and rural development measures initiatives under the CAP, but interestingly, with a focus on the intentions and decisions made by young farmers in Lithuania within the framework of rural sustainability. The differences in environmental practices between young women farmers and their male counterparts in Slovenia have also been examined [56], particularly to show how enhancing the visibility of young women on family farms and their heightened sensitivity to environmental issues influences the adoption of Agri-Environment-Climate Measures (AECMs), with significant differences in relation to received environmental subsidies.

There are also several studies that aspire to provide comprehensive insights into the viewpoints of EU farmers of all ages, contributing to the broader discourse on agricultural sustainability in the face of environmental challenges. For instance, drawing on a review of extensive academic literature, Henchion et al. (2022) [57] consider EU farmers’ and consumer-citizens’ perspectives on smart technologies across the dairy production cycle from a sustainability standpoint, with differences in knowledge accounting for some variation and differences in values also being significant. Two additional studies [58,59] sought to explore Finnish farmers’ perceptions of climate change and the shift to carbon-neutral agriculture, focusing on their understanding of roles, responsibilities, justice, and potential strategies for both mitigation and adaptation. Additionally, these studies aimed to evaluate the relationship between various farmer background variables and personal values in shaping these perspectives. Interesting to note is the scholarly concern for environmental sustainability research in Finland, among the EU countries that have increased inorganic fertilizer use. This concern is a much-needed starting point and should be extrapolated to field practice and policy-making.

Also, in a more localized framework, studies on Central and Eastern European farmers’ awareness of sustainability in the EU context by Gebska et al. (2020) [60] have focused particularly on animal and crop production and the advantages arising from sustainable production in these fields. These advantages were aptly recognized to be the protection of water against pollution and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in both dairy and crop farming in Poland.

It is essential to emphasize the importance of not only aligning agricultural policies with sustainable practices and public health goals, but also, of equal importance, with the diverse needs of farmers [61], given their key role in the provision of EU food. Ultimately, a more integrated approach that views the future generation of farmers as truly central, that empowers them with adequate resources and support while valuing their role in achieving the aforementioned objectives set forth in the F2F Strategy, would ensure healthy food security, farm and environmental sustainability in the EU.

3. Materials and Methods

In line with the study’s objectives to identify behavioral and structural factors influencing young farmers’ decision to adopt environmentally sustainable fertilization practices, data were collected in the spring of 2025 using a Google Form administered both in person and online to Romanian farmers aged up to 45 years. Given Romania’s demographic realities and the extended age of active farm management, the study adopted the aforementioned broader age threshold of up to 45 years to capture a more representative share of the country’s younger farming population. This adjustment aligns with national statistical categorizations and reflects the delayed entry of many Romanian farmers into independent farm management, providing a more contextually relevant understanding of the “young farmer” group. Participants were recruited during meetings with farmer associations, with the survey link further shared via personal and institutional networks. A snowball sampling technique was applied, whereby initial respondents were encouraged to share the questionnaire within their professional and social farming networks, facilitating broader reach and inclusion of diverse farm profiles across regions. This approach was chosen to effectively engage a population that is often dispersed and difficult to access through conventional sampling methods. Although non-probabilistic in nature, the resulting sample was broadly consistent with national data on the age, education level, and farm-type distribution of young farmers in Romania, supporting its contextual representativeness for exploratory analysis. Although response rates could not be calculated due to the open recruitment, participation was voluntary and geographically diverse. Participants were informed about the aim of the research and voluntarily agreed to fill out the survey. Anonymity and data confidentiality were ensured in compliance with GDPR regulation. The questionnaire collected data on socio-demographics, farm characteristics, present and future fertilizer usage and perceptions on their impact, awareness of EU measures aimed at reducing chemical fertilizer use, and access to EU subsidies and to knowledge. Farm type was considered a differentiating characteristic that allowed comparisons among groups. A total of 178 responses were retained for analysis. The sample size was validated through a post hoc power analysis using G*power 3.1.9.4 (effect size w = 0.33, significance level α = 0.05), which indicated a statistical power of 99% [62]. Out of the entirety of the group, the majority of respondents were male respondents (78.4%), and about 87% of the total have an agricultural diploma or are enrolled in agricultural degree programs.

Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the data. Group differences were assessed using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables. Games-Howell post hoc test was used to identify the pairwise differences, while statistical significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05. SPSS Statistics software, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), was used for all statistical analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Farm Characteristics

The surveyed farmers operate under diverse legal structures, with sole proprietorship (31.5%) and authorized natural persons (27.5%) being the most common forms (Table 1). This proportion suggests less fragmentation among the “natural persons” category or possibly fewer small farms in the sample. Official data says [63] that “without legal personality,” farms are overwhelmingly dominant in Romania, which likely corresponds to many sole proprietorships or informal farms. Approximately 54% of the farms have been in operation for over a decade, whereas a mere 3.4% are newly established, with less than one year of activity. The relatively higher share of registered entities in this survey indicates more formalized or economically active ones, reflecting a group that is more integrated into market transactions or institutional programs. This pattern might also suggest that farmers with clearer legal status are more visible and hence more likely to participate in such surveys. The high share of farms in activity for over one decade and the relatively low rate of new entrants align with the broader trend of generational stagnation in Romanian agriculture. However, since the farmers’ age is under 45, this could indicate earlier entry by our respondents into the farming business or generational farm succession, with the newer generation taking up previously established farms. The earlier farm establishment could also explain the larger surface area (with 80 farms holding over 50 ha of land) and the established and professionalized economic structure of holdings. The sampling approach might have introduced some self-selection bias, as the over-representation of mixed farms (66.3%) suggests that more diversified and market-oriented farmers were more inclined to respond, yet this group remains particularly relevant for analyzing sustainability transitions and policy engagement.

Table 1.

Respondents’ farm characteristics.

In terms of farming practices, mixed farming, encompassing both crop cultivation and livestock rearing, is the predominant farm activity, represented by 66.3%. Conversely, the remaining 33.7% of farms solely focus on crop production. The extent of land cultivated varies significantly: 44.9% of farms exceed more than 50 hectares, while only 10.1% occupy smaller plots of less than 5 hectares. Mixed farming is common in Romania, but official data suggest that specialized holdings (particularly crop-oriented) remain dominant at the structural level. Eurostat statistics indicate that Romania belongs to the group of countries where mixed farms make up around one quarter of holdings, which is considerably lower than the 66.3% recorded in the survey [64], with larger or more commercially oriented farms that diversify production or, mixed livestock and crops are more common in the regions where farms in the survey are located; or simply the threshold for what counts as livestock is low (e.g., small numbers of animals). These figures point to a dual structure within the sample, combining larger, more commercially oriented operations with a smaller share of subsistence or semi-subsistence holdings. The observed predominance of mixed farms in the survey reflects regional specificities (agroecological characteristics or local traditions, for instance) or differences in how production diversity is classified (which is disambiguated by further questions- Table 1). Overall diversity of crops and animals could point to a resilient production model, potentially aimed at self-sufficiency and risk mitigation in fluctuating market or climatic conditions. This not only enhances resilience to price and weather shocks but also allows for the efficient use of farm resources through internal feed supply and nutrient recycling.

The prevalent agricultural practices are quite varied. In terms of crop production, cereals such as corn, wheat, and barley emerge are the most prevalent, cultivated on 89% of the farms, followed by forage crops, which are grown on 60.7% of the farms. Other cultivated crops include technical plants, oil seeds, and protein crops (20.8%), potatoes (20.2%), vegetables (16.9%), and fruits and grapevines (14.6%), indicating a diverse array of crop types. Moreover, in the realm of livestock farming, 60.7% of farms raise cattle. Additional livestock present on many farms includes pigs (43.3%), poultry (35.9%), and sheep (28.1%). In contrast, the presence of horses (7.3%), bees (5.6%), and goats (5.1%) is notably less common.

4.2. Farm Production Valorization

The predominant channels for the sale of agricultural products among farmers are agricultural markets (47.8%) and processors (36.5%), which are depicted in Table 2. Other significant sales outlets include collection points (18.0%) and farmers’ associations (15.2%). In contrast, a smaller proportion of farmers engage in sales to retail facilities, including supermarkets (7.9%) and restaurants (5.1%).

Table 2.

Farm product valorization practices of young Romanian farmers.

Product distribution highlights the primary focus on raw agricultural output within the sales strategies of the surveyed farmers, as a substantial majority of farmers (88.2%) provide raw materials, in terms of the form in which products are sold. In comparison, only 27.0% of respondents report selling processed products.

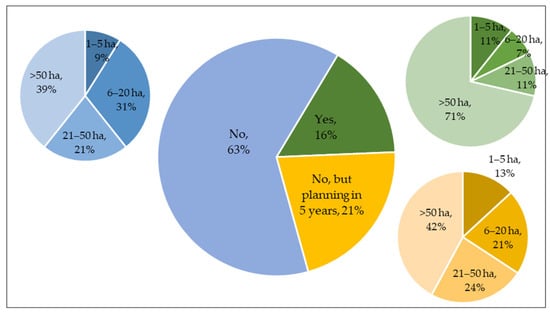

As illustrated in Figure 1, a mere 16% of farms hold organic certification, with the prevalence of such certification being notably higher among larger farms, where 71% of those certified manage over 50 hectares. Furthermore, a slightly greater percentage of farmers—21%—expressed their intention to pursue organic certification within the next five years, primarily among farms of larger scale. The data indicate a clear trend toward organic certification, particularly among more extensive agricultural operations. This distribution suggests that the adoption of organic practices is closely linked to farm size and capacity, as larger farms are generally better equipped to bear the administrative, financial, and logistical burdens associated with certification. In contrast, smaller farms may engage in low-input or traditional farming methods that align with organic principles but lack the formal certification due to limited access to markets or institutional support. The growing interest in certification among larger farms may also reflect the expanding market opportunities for organic products and the alignment of such practices with the strategic modernization goals promoted by EU agricultural policy.

Figure 1.

Organic certification status and intention of young Romanian farmers.

4.3. Types of Subsidies Accessed and Knowledge of EU Fertilizer Regulations

The respondents were asked if they have received support from the National Rural Development Program from 2014 to 2022 (Table 3). The most prevalent form of subsidies received was direct payments under Pillar I, which were significantly more awarded to crop producers (78.3%) in comparison to those engaged in mixed farming (38.1%) (p < 0.001). In contrast, significant disparities were found in the case of coupled income support which was found to be notably more common among mixed farms (55.9%) than among those focused solely on crop production (6.7%) (p < 0.001). Participation in eco-schemes (green payments) and transitional national aids exhibited moderate uptake, with engagement rates fluctuating between 21% and 30%. Compensatory measures from Pillar II were reported less frequently across both farming categories, except for agri-environment and climate payments, where significant disparities were identified; mixed farms benefited from substantially higher levels of support in this area (p < 0.05). Respondents’ strong willingness to access subsidies in the next five years, with 96.1% indicating their intent, reveals a strong reliance and trust in EU support, potentially including greening or environmental payments.

Table 3.

Type of subsidies accessed by respondents.

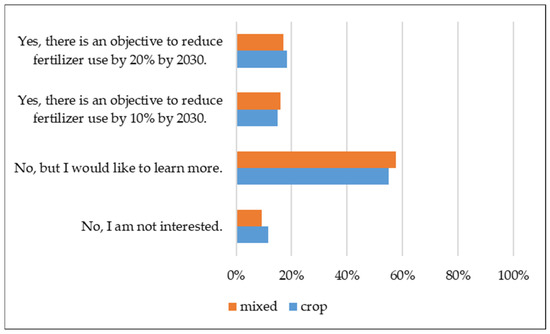

A notable percentage of farmers, representing both crop and mixed farming sectors, reported insufficient familiarity with the EU’s fertilizer policies as outlined in the F2F and therefore the GD, although they demonstrated a strong interest in obtaining further information (Figure 2). No statistically significant differences were noted between the two groups of farmers (p > 0.05). Approximately 33% of respondents from each category acknowledged some awareness of the measures, with some incorrectly citing a 10% reduction target by 2030, while others referred to the established target of 20%. It is significant to mention that only a limited number of farmers indicated a lack of interest in learning more about these policies. These findings highlight a general information gap regarding EU environmental objectives, suggesting that the communication and dissemination of policy details remain limited at the farm level. The mixed understanding of reduction targets also points to confusion between different EU sustainability initiatives, reflecting the potential complexity of the regulatory framework as perceived by farmers. Nevertheless, the expressed willingness to acquire more knowledge represents a positive foundation for future outreach and capacity-building efforts, indicating that awareness campaigns and advisory services could effectively bridge this gap and lead to greater compliance with EU sustainability goals.

Figure 2.

Young farmers’ knowledge of EU fertilizer use policies under the F2F within the GD.

4.4. Fertilizer Use: Current Practices and Future Intentions

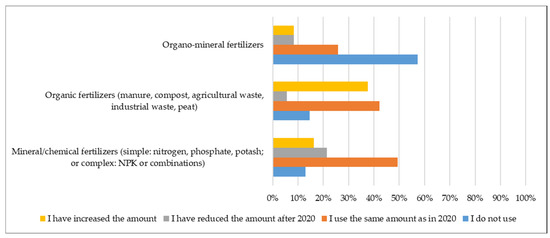

Farmers were surveyed regarding their fertilizer usage practices, which included the types of fertilizers applied (Figure 3), their sources of information and procurement, as well as their approaches towards the reduction of chemical fertilizer application. Notably, approximately 21% of farmers reported a reduction in the use of mineral or chemical fertilizers since 2020; in contrast, 49% maintained their usage levels. Expectedly, there has been a significant increase in the adoption of organic fertilizers, with 38% of farmers incorporating them, while about 42% reported using organic fertilizers at consistent levels compared to 2020. Conversely, organo-mineral fertilizers appear to be less favored, with 57% of farmers indicating that they do not utilize them. Among those who do use organo-mineral fertilizers, 26% have maintained their usage, and only a small percentage reported a change in behavior regarding this type of fertilizer.

Figure 3.

Types of fertilizer used by young Romanian farmers.

Regarding fertilizer procurement, many farmers identified multiple sources. Approximately 60% indicated that they acquire fertilizers directly from local distributors. Fewer farmers rely on organically produced fertilizers from their own farms or purchase directly from manufacturing companies (Table 4). Their choices are largely influenced by the accessibility of information, with local distributors, manufacturing companies, and the internet identified as primary sources (Table 4). While specialized magazines and training courses are also widely used sources of information, social media platforms and newsletters were mentioned less frequently.

Table 4.

Fertilizer procurement, information sources, and reasons for reduction.

Farmers were asked on their reasons to reduce the amount of chemical fertilizers and/or why they consider it a need for the future (Table 4). The most frequently cited reasons included the reduction in input costs, the preservation of soil properties, and a growing concern for environmental sustainability and biodiversity.

Farmers were also asked to assess their level of agreement with a series of statements pertaining to the use of chemical fertilizers, utilizing a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Table 5). These statements addressed the environmental and economic implications of chemical fertilizers, along with the farmers’ role in enhancing food security. Perceptions were analyzed across four distinct groups: (1) farmers who do not utilize fertilizer; (2) farmers who maintain their fertilizer usage at the same levels as in 2020; (3) farmers who have reduced their fertilizer application; and (4) farmers who have increased their fertilizer use. Comparisons were made separately for each of the three types of fertilizers.

Table 5.

Farmers’ perceptions on chemical fertilizer impact for the environment, business and consumers.

The analysis revealed no significant differences among the groups concerning their perceptions of the environmental and economic impacts of chemical fertilizers. All groups demonstrated a moderate level of agreement that chemical fertilizers are detrimental to the environment. When questioned about the sustainability of their own farming operations, concern levels were notably higher among all respondents. Specifically, regarding organic fertilizers, farmers who had increased their usage expressed significantly greater concern about their responsibility in providing healthy and affordable food, with a mean score of 4.55 (±0.72), compared to those who had reduced their usage, who reported a mean score of 3.50 (±1.43) (p < 0.05).

Employing the same 5-point Likert scale, the four groups were also assessed for their level of agreement with additional statements regarding the importance of reducing chemical fertilizer use (Table 6). The perceived contributions of chemical fertilizer reduction to local economic development and food security through the provision of healthier food were met with moderate agreement across all groups, resulting in average scores with no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05).

Table 6.

Farmers’ perceptions on the reduction of chemical fertilizers.

However, perceptions regarding future usage behaviors of mineral fertilizers varied among the groups in relation to who should implement reductions and which types of farms should be involved. Farmers who reduced their use of chemical fertilizers exhibited significantly stronger agreement that all farms should reduce their chemical fertilizer usage, irrespective of farm size, with a mean score of 3.53 (±1.16), compared to those who increased their use, who reported a mean score of 2.79 (±0.98) (p < 0.05). A similar significant difference was identified for the statement advocating that reductions should be implemented by all farms, regardless of farm type, where farmers reducing their chemical fertilizer use expressed notably higher agreement, with a mean score of 3.55 (±1.01), as opposed to those who increased usage, who scored an average of 2.86 (±0.99).

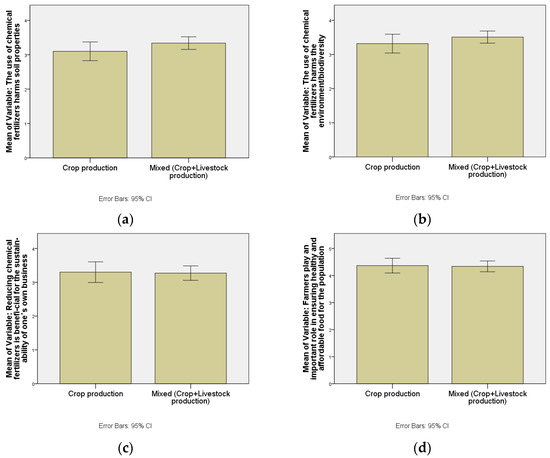

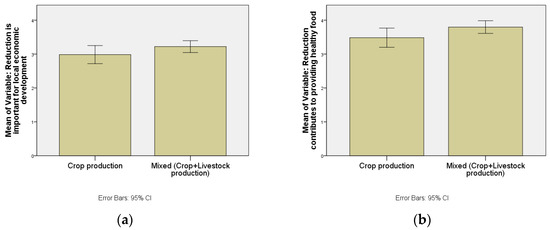

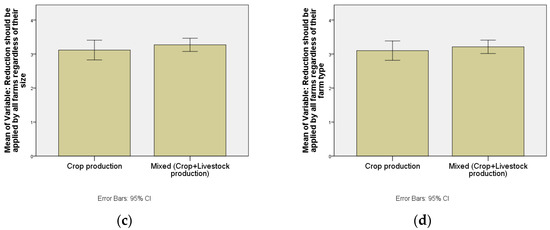

Furthermore, it was investigated whether the perceptions of chemical fertilizer use differed between farmers engaged solely in crop production and those involved in mixed (crop and livestock) systems. The perceptions related to the use of chemical fertilizer and the one related to the importance of reducing their use are depicted in Figure 4 and Figure 5. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups of farmers (p > 0.05). The average scores were moderate to high, suggesting a shared concern among farmers about the potential impacts of chemical fertilizer use on the environment, farm sustainability, and human health.

Figure 4.

Comparative average scores by farm type (scale: 1 to 5, 1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree) (a) The use of chemical fertilizers harms soil properties; (b) The use of chemical fertilizers harms the environment/biodiversity; (c) Reducing chemical fertilizers is beneficial for the sustainability of one’s own business; (d) Farmers play an important role in ensuring healthy and affordable food for the population.

Figure 5.

Comparative average scores by farm type (scale: 1 to 5, 1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree) (a) Reduction of chemical fertilizer is important for local economic development; (b) Reduction of chemical fertilizer contributes to providing healthy food; (c) Reduction of chemical fertilizer should be applied by all farms regardless of their size; (d) Reduction of chemical fertilizer should be applied by all farms regardless of their farm type.

5. Discussion

The concerning EU trend where 57% of farm managers are over the age of 55 [34] is duly matched by Romania’s overwhelming proportion of 39.6% farm managers over 65. These top-heavy age structures have prompted high EU policy interest and this research to consider and encourage a new generation of farmers, acknowledged for their considerable potential to lead the transition towards a sustainable agri-food system [65], as postulated by the F2F strategy. and for addressing the challenges inherent in agricultural succession.

5.1. Q1: What Are Young Farmers’ Views and Behavior Towards the Reduction of Chemical Fertilizer and the Increase in Organic Fertilizer Use and Practices in the Context of the F2F and GD Strategies?

With the first research question in mind, information on young farmers’ fertilizer use behavior supports EU data [12] on Romania’s increase in the use of mineral fertilizers, but only partially, with 21% of farmers reporting a reduction in the use of mineral fertilizers since 2020. In contrast, 49% maintained their usage levels, and 30% increased their chemical fertilizer use levels. This reveals the propensity of young farmers to balance their use of chemical fertilizing inputs in a country where the upward trend for chemical input usage is evident and documented. This balance is also reflected in the increase of 38% of farmers incorporating organic fertilizers in their operations and about 42% using organic fertilizers at consistent levels compared to 2020. This more balanced and environmentally conscious behavioral pattern may reflect both growing awareness of sustainability objectives and a pragmatic response to rising input costs or changing market conditions. Moreover, the notable proportion of farmers incorporating or maintaining the use of organic fertilizers indicates a gradual integration of alternative nutrient management strategies that could contribute to the long-term goals of the Farm to Fork Strategy.

From a theoretical standpoint, the results first contribute to understanding the behavioral dynamics of young farmers as agents of agricultural transition. The coexistence of stability in mineral fertilizer use with increased interest in organic inputs reflects a process of incremental sustainability-oriented adaptation rather than radical behavioral change. This gradual shift aligns with well-established theories of innovation diffusion, where adoption of new practices occurs progressively across the farming community [66]. It suggests that younger farmers are more likely to experiment with hybrid input use behavior in an evolutionary manner, requiring social learning, trust-building, and visible demonstration of benefits rather than top-down directives alone in order to ultimately balance economic viability and environmental responsibility. These findings also stress the role of information access and policy awareness in shaping environmental behavior (addressed by Q3), aligning with theories of planned behavior and environmental literacy, where knowledge and perceived behavioral control influence sustainability-oriented decisions. Similarly, studies worldwide [67,68,69,70] believe young farmers to exhibit more potential to adopt novel business models, digital and precision technologies on the farm, have priority access to information, to innovative precision techniques [71] thereby facilitating the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices, which include methods such as reduced fertilizer usage, enhanced nutrient use efficiency while supporting sustainable or organic agricultural practices and safeguard business sustainability.

EU policy signals (F2F farmers’ adoption of improved nutrient management practices) translate, via national implementation, into these young farmers’ motivations (cost, values, norms), capacities (knowledge, tools, advisory access), and perceived risks towards mixed fertilizer use trajectories (reduction, status quo, increase). Interestingly, young farmers’ behavior towards reduced chemical fertilizer use is neither particularly consistent with the overall European direction in this respect, nor with farmers’ clear awareness of the detrimental effects of these inputs. All respondents, regardless of the farm type or their behavior towards reducing or increasing chemical fertilizer usage, showed moderate levels of agreement related to the damage that chemical fertilizers exert on the environment (Table 4). They also stressed their responsibility towards environmental health and the provision of clean and healthy food, especially farmers who had increased their use of chemical inputs. This reveals young farmers’ overt declarative awareness, but naturally begs the question as to the reasons against the subsequent reflection of this awareness in everyday farm practice. In a similar Romanian context, a disconnect between the beliefs and attitudes farmers have about protecting the environment and their actual agricultural practices is also present [72].

In practice, this means that while environmental awareness among young farmers is high, the structural and economic conditions necessary to enable consistent behavioral change are not yet fully in place. One can tentatively assume that reducing mineral fertilizing inputs could be regarded as a cumbersome and lengthy endeavor that would elicit significant farm resources, involve bureaucratic constraints and long-term commitment, not to mention potential production decreases. With the appropriate mindset and motivation, proven by their answers, farmers could take the next step towards the gradual behavioral transition to reduce fertilizer use. Therefore, effective policy implementation must move beyond awareness-raising and address practical policy action. Fostering and enhancing the overall vitality and sustainability of the EU and Romanian agricultural sector relies on initiatives such as the Young Farmers Program- Setting up Aid, Complementary Income Support and Investment Support that facilitating young farmers’ entry and active participation in modern farming practices [73,74]. This is essential, as studies have indicated that the average age of farmers continues to rise, thereby stressing the need for these comprehensive policies to attract younger demographic groups into farming [75] and supporting them to pursue this activity for the long-term, as with cases of farm management and ownership being transferred generationally. This is especially important, as young farmers are undoubtedly more technologically savvy, more educated and dynamic in terms of their access to knowledge and resources. There is significant potential in accessing EU support mechanisms and subsidies for farm and environmental sustainability as it appears to be devoid of obstacles for the young farmers surveyed in supporting their agricultural operations (Table 3).

From the same theoretical standpoint, the results contribute to understanding more broadly the attitude–behavior gap in environmental decision-making within agriculture. The finding that even farmers who increased fertilizer use might express strong environmental concern supports the notion that awareness and pro-environmental attitudes do not automatically translate into sustainable behavior. This aligns with established behavioral theories such as the Theory of Planned Behavior [76] and the Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) framework [77], which emphasize the mediating roles of perceived behavioral control, social norms, and contextual constraints. The disconnect observed here suggests that cognitive and normative alignment with sustainability principles is insufficient when economic risks might outweigh perceived benefits.

5.2. Q2: How Can Their Behavior Be Explained Alongside Their Knowledge and Views Regarding Sustainability Desiderata and the Provision of Healthy Food for the EU Population?

Confirming the aforementioned theoretical bases, the complex reasons behind farmers’ perspectives and behavior related to further reduction in order to comply with F2F objectives are predominantly contextual- economic in nature, such as reducing input costs by reducing the reliance on expensive mineral fertilizers, followed by environmental protection views such as the preservation of soil properties and an overall concern for environmental sustainability and biodiversity. These are secondary, but complementary reasons, indicating that sustainability efforts are pursued when they align with economic self-interest. Their perspectives aptly align with studies identifying Romanian trends towards agricultural sustainability as mostly dependent on economic sustainability (business productivity and increase in personal income), rather than social (reduction of poverty in rural areas) or environmental sustainability (increase in production of renewable energy, rise in organic farming and reduction of nitrogen balance), which are identified as achieved [78]. Even young farmers’ awareness related to fertilizer reduction is primarily fueled by concerns for business profitability and sustainability through farm savings on costly inputs, preceding any environmental considerations (Table 4) (Figure 4). Other studies have also identified a downsizing of environmental concerns even with the educated farmer population in Romania, where agriculture is acknowledged as a profitable industrial activity first and foremost [72].

All these findings are a reflection of the instrumental rationality prevalent in Romanian agriculture, where environmental behavior is contingent upon its alignment with farm-level economic sustainability. The findings also echo the notion of incremental adaptation discussed by [66], where behavioral change occurs gradually as innovations become economically feasible and institutionally supported, rather than through abrupt, norm-driven transformations. In essence, young farmers’ choices reveal a pragmatic form of conditional environmentalism that must be considered in both behavioral investigation and future policy designs. As such, the practical implications for policy design should include incentive mechanisms aimed at reducing chemical inputs, which are more likely to succeed if they integrate economic benefits (e.g., cost savings, efficiency gains, and market advantages) alongside environmental objectives.

Conversely, young farmers’ significant reliance on agricultural markets (47.8%) and processors (36.5%) (Table 2) may indicate that many farmers prioritize direct connections to their consumers and value chains that emphasize environmental sustainability, organic certification and traceability, which are increasingly important to environmentally conscious consumers. Moreover, the lesser engagement in sales through supermarkets (7.9%) reflects a potential disinterest in mass-market distribution channels that may prioritize volume over sustainability. Farmers’ sales dynamics suggests a pragmatic approach in which young farmers seek to maintain economic viability through differentiated, sustainability-oriented [79] new market niches seeking to reduce waste and loss, rather than competing in price-sensitive conventional markets. In practical terms, these results indicate that supporting organic, local markets, producer cooperatives, and green value chains, and promoting certification schemes can simultaneously advance both environmental and economic objectives for these young producers. Second, from a theoretical perspective, our findings reveal that sustainability transitions in agriculture are shaped by market-mediated social learning processes, provided that institutional and infrastructural conditions allow them to capitalize on these market-oriented sustainability opportunities.

Moreover, the predominance of farmers focusing on raw agricultural outputs, with 88.2% selling unprocessed products, aligns closely with the sustainability objectives of the EU’s F2F strategy, which emphasizes the need to reduce food waste and food loss across the entire food supply chain [80]. However, this trend could be attributed to the crop type, with cereal grains being predominantly produced and less-frequently processed on the farm, as well as the large farm sizes in our study when it comes to both cereal grain crops and mixed farms.

Quite noteworthy, the proportion of large farms in this array was sizeable (44.9% of farms were over 50 ha). It is believed that larger farms in the European Union exhibit a significant potential and inclination to adopt sustainable agricultural practices, such as fertilizer reduction and organic conversion. In our studies, farms cultivating over 50 ha represent 71% of holdings with an organic certification, confirming literature accounts [81]. Scale enhances the capacity for sustainability-oriented innovation, reliant on the fact that higher resource availability leads to integration of innovation and technology into these substantial agricultural enterprises and henceforth to enhanced efficiency and environmental stewardship. Hloušková and Prášilová (2020) [82] even highlight that young farmers managing larger agricultural operations, like in our study, tend to embrace innovative practices more than older generations, which is consistent with our research only at a discursive level, but indicating a correlation between farm size, age and the likelihood of adopting sustainable methods. Similarly, Krejčí et al. (2019) [83] emphasize that while small-scale farmers face market challenges, larger farms are positioned to implement diversified sustainable strategies, which enhance their competitiveness and contribute to the overall sustainability of the agri-food chain. Practically, this differentiation highlights the importance of tailored policy design that recognizes the heterogeneity of farm structures across the EU, with CAP and F2F targeted policies that incentivize organic and regenerative agriculture [84] yielding faster results when strategically directed toward larger holdings, while smaller farms might require more structural support and targeted incentives to overcome entry barriers. Although representing only a little over 10% of the farms surveyed, small farms should not be overlooked or deterred from this convergence towards organic practices, although at the beginning, it might be difficult for them to absorb the initial costs. It has been argued [30] that the long-term economic benefits of these practices can outweigh the initial costs, as they often lead to decreased dependency on pricey chemical inputs and foster resilience against market volatility. As a corollary, under the F2F strategy, organic agriculture in the EU is predicted to reach 25% of the total agricultural area by 2030 from 9.1% in 2020 [85].

But these matters are not at all simple for neither farm type nor size. More in-depth studies [86] have shown that organic farming conversion and viability are highly dependent on a multitude of on-farm factors, like the management, safety and sustainability of nutrient supply and sources, farm location, higher farm output and land-use efficiency and much less on farm type, while there is no mentioning of farmers’ age or farm dimension as indicative factors for organic farming uptake or economic viability. The yields in organic farming system have been reported to be globally 75–81% of the ones of conventional farming systems or even lower in countries with a general high productivity (e.g., northern Europe 70%) [87], but more research is needed to clarify what agronomic practices and favorable conditions can enhance organic farming’s productivity potential across different farm types and sizes.

As the farms surveyed were diverse in terms of agricultural practices, with the majority (66.3%) being mixed livestock and crop farms, their crop diversity and mixed type outline a tentatively optimistic account for the future, as it is essential that agricultural systems focus towards integrating diverse crops and cropping methodologies that both address food security and promote environmental resilience [88]. This is because a focus on monoculture and high-yield crops has been shown to undermine biodiversity and limit the production of nutrient-rich foods, posing significant risks to agricultural sustainability. According to research by Figuerola et al. (2014) [89], monoculture practices can reduce the spatial turnover of soil microbial diversity which play an essential role in maintaining healthy soil ecosystems and nutrient cycling. This can hinder the capacity of agricultural systems to support diverse and nutritious crop production, limiting food quality and variety available to consumers. Contrary to our study, there is evidence suggesting that larger farm sizes may reduce the cultivation of nutrient-dense crops [90] due to farmers’ focus on income stability as paramount when deciding to undertake practices that enhance food quality. Market fluctuations and risks associated with the agricultural sector can lead them to prioritize short-term yields over sustainable methods [91], especially given the increasing regulatory pressure that often comes with sustainability mandates. From a practical perspective, the mixed production model observed among young farmers reflects an important adaptive strategy in line with EU sustainability objectives promoting agroecological intensification and circular resource use. However, ensuring that such diversity translates into long-term resilience requires policy frameworks that reward multifunctional farming systems—through agri-environmental payments, diversified crop insurance mechanisms, and market recognition for ecosystem service provision. The findings therefore stress the practical need for supportive governance structures that sustain diversity as both an ecological and economic asset, counteracting the pressures toward specialization and monoculture driven by global commodity markets. Theoretically, these findings reinforce the notion that sustainability transitions in agriculture emerge from systemic interactions between ecological complexity and socio-economic behavior, rather than from purely technical or policy interventions.

5.3. Q3: What Means of Information, Education, Training and Procurement Can Be Used to Encourage Farmers to Align to the Provisions of Fertilizer Reduction Under the F2F Strategy?

An integrated avenue for further aligning environmental awareness and farm practices in Romania would be a reliance on every form of education and training made available to young farmers. As the study reveals, specialized formal and informal education is prized by respondents, with 87% having or being enrolled in specialized higher education. Specific information about fertilizer usage is extracted from certified sources (such as distributors, companies, agricultural magazines and targeted courses) and less from informal sources (such as social media platforms and newsletters). The same findings derived from the most recent 2020 Agricultural Census [34] highlight the educational advantage held by younger farmers, revealing that approximately 21% of individuals under the age of 35 have attained qualifications from agricultural colleges, universities, or other forms of higher education focused on agriculture. In stark contrast, only 4% of farmers aged 65 and above possess similar educational credentials. No wonder that our young educated respondents choose certified and official sources to provide them with the necessary information on fertilizer use. This further suggests that young farmers are receptive to expert guidance and value scientific legitimacy in their decision-making and can directly influence the quality and sustainability of on-farm practices. These same sources should be further used to enhance and complement their existing knowledge, especially in relation to F2F and overall GD mandates.

This disparity in educational attainment not only highlights the potential for younger farmers to implement modern and sustainable practices but also emphasizes the critical role of farmers’ education in driving innovation within the agricultural sector. Young farmers are more likely to implement practices that prioritize environmental sustainability, which is essential for the long-term viability of agricultural systems [73,74]. Conversely, when (specialized) education and training are lacking, detrimental economic and environmental issues can emerge, as revealed by a study on South-Asian farmers’ use of organic and inorganic fertilizers [92]. Lack of specialized and authorized information as to chemical fertilizer dosage or a low overall education level may lead to over-use and subsequent environmental and economic downsides. The intergenerational gap revealed by EU census data reveals a stark need to institutionalize lifelong learning frameworks that can bridge educational disparities across age cohorts, ensuring that sustainability goals are adopted uniformly across Romania’s farming landscape. However, it is interesting to note that with younger and more educated generations of farmers, labor-intensive practices like organic fertilizer (manure) application tend to be disregarded and can lead to a surge in less labor-intensive practices of inorganic fertilizer use. This might provide a rationale for our findings related to inorganic fertilizer use among young farmers, as well as one reason for agriculture’s lack of appeal for European youth, seeking easier life paths, especially in more developed countries where opportunities are manifold.

Furthermore, findings on young farmers’ awareness of F2F’s 20% chemical fertilizer reduction until 2030 may help us shed light on the best avenues for farmer education and training as it reveals a prevailing awareness gap regarding EU fertilizer policies among farmers, despite their willingness to engage with and understand the initiatives associated with the Green Deal. Their awareness is not precise, but they exhibit high willingness to improve and professionalize their knowledge and their businesses, thus leaving room for education and training interventions and necessary synergies between formal and informal education, between European and national communication and training campaigns that would undoubtedly yield practical outcomes towards GD and F2F goals, providing respondents’ declared openness.

Moreover, farmers’ knowledge and experience on the potential of organic waste fertilizing options available are highly critical [93] in the uptake of these organic variants as their social acceptance and pertinent information on potential health risks needs to be addressed at European and national levels. This might also explain the feeble transfer of theoretical knowledge and views on organic and sustainable agriculture into Romanian farm practice and the need for (young) farmers to be well-trained and informed on the organic variants available, by companies, national and European authorities and even academia developing such innovative practices. Without these synergies, young farmers’ knowledge and views on environmental sustainability might remain stuck at a discursive level. However, this is not only the case in the Romanian farming setting, as variations in environmental sustainability knowledge, values and practice in farming and consumer communities have been identified globally [57].

The need to professionalize and expand farmers’ knowledge on the availability and use of organic fertilizing variants is even more stringent, with chemical and organic fertilizer use being regarded in a broader global context. This is not a small matter either, as EU countries are highly dependent on expensive chemical fertilizers sourced from raw materials coming from such countries as Russia, US, Australia, Morocco, Canada and China, which are either distant or unstable markets, or both. The majority of our respondents stated that their sources involve local distributors and manufacturing companies for mineral fertilizers, proving the accessibility of these products through consistent distribution networks. In truth, there are several major companies that dominate the EU landscape, including Yara International, BASF, and Nutrien. Yara International predominantly uses natural gas from Canada and Australia as a feedstock for the production of nitrogen fertilizers, while Nutrien is the largest manufacturer of potash and sources its potassium from extensive mining operations, also predominantly in Canada. BASF is one that emphasizes integrating sustainable practices, sourcing both nitrogen and phosphate from its own mines and recycling processes to ensure a more sustainable approach. However, the present EU’s raw material strategy aims to secure domestic sourcing while enhancing the sustainability of fertilizer production, improving resource efficiency and circular economy practices. This perspective should include raw materials management from more reliable EU sources [93], as well as purchasing outlets.

Conversely, as far as organic fertilizer procurement is concerned, respondents source their organic fertilizers either from their own production or from manufacturing companies. This also raises questions of knowledge and responsibility, safety, waste management from primary sources, scalability and economic efficiency, especially when larger farms are concerned. Notably, the F2F Strategy [1] stresses the improvement in the application of precise and sustainable fertilization techniques, which are extremely important in hotspot areas of intensive livestock farming.

Interestingly, Mainar-Causapé et al. [94] provide robust quantitative evidence that the implementation of F2F targets—particularly reductions in fertilizer and pesticide use—could generate short-term economic stress in Eastern European agriculture, including Romania, where farm structures are dominated by small-scale and semi-subsistence holdings. Such structural vulnerabilities translate into a higher risk of income losses, productivity declines, and employment effects compared to Western EU countries with more consolidated farm systems. For young farmers, this dual context presents both a risk and an opportunity. On the one hand, limited access to capital and land, coupled with weaker market integration, make young entrants especially vulnerable to the increased costs and stricter compliance requirements that F2F entails. This could discourage new generations from entering farming or drive them toward conventional practices that prioritize short-term survival over sustainability. On the other hand, as shown by our study, younger farmers often display higher levels of environmental awareness and openness to diversification. With adequate policy design, they could act as frontrunners in sustainability transitions, pioneering practices such as organic farming, regenerative agriculture, precision fertilization, or diversification into short food supply chains.