1. Introduction

Climate change is a critical global challenge that poses substantial threats to economic and social development worldwide. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025 [

1], environmental risks dominate the long-term global risk landscape. The American Meteorological Society’s 35th State of the Climate Report (2025) indicates that 2024 set records for key climate indicators, including greenhouse gas concentrations, land and ocean surface temperatures, and sea-level rise [

2]. Similarly, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) reports that the global average temperature in 2024 was 1.55 °C (±0.13 °C) above pre-industrial levels, the highest since records began [

3]. These findings underscore that climate change poses an immediate, rather than distant, threat.

According to the TCFD framework, climate risk encompasses the uncertainties associated with physical climate impacts and the transition to a low-carbon economy [

4]. As fundamental units of socioeconomic activity, firms are exposed to both physical and transition risks [

5]. Physical risk stems from acute climate events and long-term shifts in climate patterns that can damage production facilities, disrupt supply chains, and cause casualties [

6,

7], thereby impairing productivity and economic performance [

8]. Transition risk arises from climate-related policy shifts, regulatory changes, technological advances, and market transformations, such as tighter environmental regulations and higher emission-reduction targets, which compel firms to adjust their operational and technological strategies [

9]. Compared to the direct and observable nature of physical risks, transition risk, driven by policy and systemic factors, exerts more complex and far-reaching influences on strategic corporate decisions: particularly green innovation. Accordingly, we focus on transition risk.

Green innovation is widely regarded as being central to corporate green transformation and is a key driver of sustainable development in a low-carbon economy [

10]. It plays a significant role in enhancing energy efficiency and firm performance [

6]. However, green innovation is typically characterized by long development cycles, substantial capital requirements, high uncertainty in returns, and dual externalities from environmental protection and knowledge spillovers. These features often result in market failures. Growing environmental pressures and corporate climate actions have heightened scholarly interest in how climate change influences innovation behavior: particularly firms’ engagement in green innovation.

This study examines the impact of climate transition risk on corporate green innovation and seeks to reconcile divergent findings regarding the inhibiting versus facilitating effects in the existing literature. Our study is informed by two contrasting perspectives. On the one hand, a cost-based view posits that climate risk can inhibit green innovation by increasing debt costs [

11], forcing deleveraging, eroding operating profits, and heightening cash-flow volatility [

12], which undermines the risk-bearing capacity [

13] and ultimately depresses the R&D investment [

14,

15], thereby dampening green innovation. On the other hand, a competing view, consistent with the Porter Hypothesis [

16,

17], argues that climate risk can incentivize innovation by raising managerial attention and uncovering new opportunities [

18], prompting firms to increase R&D expenditure [

19] and accelerate green technological breakthroughs [

20,

21,

22].

We argue that the mixed evidence may reflect insufficient consideration of firm-level heterogeneity in responsiveness to climate transition risk. The apparent contradiction, along with statistically insignificant aggregate relationships, may arise when the sample includes firms with opposing behavioral responses. Drawing on options theoretical perspectives (real and growth options) [

23,

24], we posit that corporate green innovation reflects a complex trade-off between short-term costs and long-term benefits, and between conservative and proactive strategies. To capture this heterogeneity, we introduce a directional sensitivity distinction: “positive sensitivity” (

), where firms perceive climate risk signals as opportunities, and “negative sensitivity” (

), where such signals are perceived as threats. Our primary objective is to test whether the coexistence of these opposing sensitivities explains the mixed evidence in prior research and the potential masking of significant underlying relationships.

To systematically test this proposition, we construct firm-level measures of sensitivity to public climate attention, using data on Chinese A-share listed companies from 2011 to 2023. Following Gong et al., Lin et al., Chen et al., and Huynh and Xia [

25,

26,

27,

28], we use Baidu Search Index data on climate transition risk-related keywords as a proxy for shifts in public attention to climate risk, given Baidu’s dominance in China’s search market. We then estimate firm-level return sensitivities to these attention shocks, to construct three variables: the composite sensitivity measure (

), positive sensitivity (

), and negative sensitivity (

). We subsequently examine how these sensitivities relate to corporate green innovation, with particular emphasis on the financing constraints and R&D investment channels, and we conduct heterogeneity analyses by considering industry attributes, ownership type, board and executive financial backgrounds, and regional characteristics.

China provides a compelling empirical setting for our analysis for two reasons that are directly related to transition dynamics. First, as the world’s largest carbon emitter, accounting for roughly 35 percent of global CO

2 emissions in 2023 [

29], China’s pursuit of its “dual carbon” goals has prompted the development of a comprehensive and evolving regulatory framework. Policies such as the Implementation Plan for Improving the Market-Oriented Green Technology Innovation System exemplify this transition pressure [

30] and explicitly position green innovation as a strategic national priority. Second, this period of heightened policy activity coincides with a measurable surge in green technology development, including an average annual growth rate of about 10 percent in green low-carbon patents between 2016 and 2023 [

31]. This combination of significant regulatory pressure and vibrant innovative activity provides a favorable context for identifying how firms navigate climate transition risk.

Our analysis yields findings that help to reconcile conflicting evidence. At the aggregate level, we observe a statistically insignificant relationship between climate transition risk and corporate green innovation. However, this null result masks substantial underlying heterogeneity. Disaggregating by sensitivity type reveals a clear polarization: positive sensitivity () is associated with higher green innovation, whereas negative sensitivity () is associated with lower green innovation. This pattern suggests that the coexistence of opposing firm-level responses can obscure the underlying relationship. Further analyses confirm that financing constraints and R&D investment are channels operating in opposite directions. Moreover, this polarization pattern is more pronounced among manufacturing firms, non-state-owned enterprises, firms without financial backgrounds, and firms in central-western or low-marketization regions.

This study makes three contributions to the literature on climate risk and corporate innovation. First, it identifies an overlooked empirical pattern: a statistically insignificant aggregate relationship between climate transition risk and corporate innovation. In contrast to prior studies that report either significant negative effects [

11,

12] or significant positive effects [

18,

20], our baseline analysis reveals a null aggregate relationship. We demonstrate that this does not imply the absence of underlying effects; rather, it reflects the aggregation of strong but opposing firm-level responses. Second, we develop and validate a firm-level heterogeneity framework that reconciles conflicting perspectives by introducing the distinction between positive and negative sensitivity to public climate attention. We demonstrate that the “inhibition” and “promotion” narratives apply to distinct types of sensitivity, and that neglecting such heterogeneity may bias inference about how climate risk influences innovation. Third, we provide granular evidence for the mechanisms driving these divergent outcomes. We establish that financing constraints and R&D investment are key channels operating in opposite directions, depending on a firm’s sensitivity type. These mechanisms offer micro-level insights into how the same macro-level risk can lead to fundamentally different innovation strategies, providing empirical support for our core argument that a statistically insignificant aggregate effect masks heterogeneous responses.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 develops the theoretical analysis and hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the research design.

Section 4 presents the main empirical results, including robustness tests.

Section 5 examines the underlying mechanisms.

Section 6 conducts heterogeneity analyses across industry, ownership, board and executive financial backgrounds, and regional dimensions.

Section 7 provides additional analyses, including the policy shock around the Paris Agreement.

Section 8 concludes with key findings and policy implications.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

This section explores how the relationship between climate transition risk and corporate green innovation reflects a set of strategic trade-offs, and how these trade-offs can lead to opposing firm-level responses. We first set out the competing effects that render the aggregate impact theoretically indeterminate and motivate our competing hypotheses. We then describe the mechanisms through which these effects operate, focusing on financing constraints and R&D investment as two testable channels.

The relationship between uncertainty and innovation presents a theoretical puzzle that is best understood through two competing yet complementary perspectives: real options theory and growth options theory [

23,

24]. The traditional real options perspective emphasizes what we term the “inhibiting effect” of uncertainty. Under this framework, when environmental uncertainty increases, risk-averse firms tend to delay irreversible investments to preserve flexibility and gather additional information. Applied to the green innovation context, this translates to a cautious approach where unclear technology paths, volatile policy directions, and ambiguous market demand collectively encourage firms to adopt a “wait-and-see” strategy until uncertainty diminishes to more manageable levels.

However, building on a different theoretical foundation, the growth options perspective challenges this conservative view by highlighting the “facilitating effect” of uncertainty on investment decisions [

24]. Under this theoretical lens, uncertainty paradoxically increases the option value when future growth opportunities carry substantial potential, as option holders can capture upside gains while limiting downside exposure. In the climate transition context, this translates to a more aggressive investment stance, driven by strengthening policy support, evolving consumer preferences toward sustainability, and the potential for technological breakthroughs that create significant upside potential for green innovation. Under these conditions, moderate levels of uncertainty function as investment catalysts rather than deterrents.

The fundamental distinction between these theoretical perspectives lies in their underlying assumptions about market competitiveness and timing advantages. Real options theory typically assumes firms possess exclusive or quasi-exclusive investment opportunities, allowing them the luxury of patient capital allocation. In contrast, growth options theory operates within a competitive framework where first-mover advantages and preemption effects create urgency that can override uncertainty concerns [

32].

Climate transition risk adds complexity by simultaneously altering both the intrinsic value and optimal timing of these strategic options. This dual influence creates competing mechanisms that pull firm behavior in opposite directions. The first mechanism, which we label the “information value effect”, suggests that the rising transition risk increases the value of waiting. When confronted with multi-faceted uncertainties, ranging from regulatory changes to technological disruptions, postponing investment decisions allows firms to observe and incorporate more valuable information, ultimately enabling more optimal resource allocation decisions. This effect naturally aligns with the real options framework, where policy uncertainty embedded in transition risk, combined with the high sunk costs of green innovation, increases the option value of waiting. The incentive to delay is stronger when agency frictions are pronounced, leading managers to prioritize short-term financial security and metric-based performance targets [

33], and this is more evident in capital-intensive, high-carbon industries where regulatory timing can shift the profitability of abatement paths [

34].

Simultaneously, climate transition risk can intensify competitive dynamics through what we term the “competitive pressure effect”. As regulatory frameworks tighten and market opportunities for green technologies become more apparent, the opportunity cost of delay escalates rapidly. Firms operating under these conditions face compressed decision windows where maintaining a wait-and-see approach risks sacrificing the market position and first-mover advantages to more aggressive competitors. This competitive urgency pushes firms toward immediate action despite uncertainty, as proactive innovation in increasingly competitive low-carbon technology markets enables firms to secure first-mover advantages and lock in future market positions through preemption, standard-setting, and the appropriation of intellectual property [

24]. The dynamic capabilities perspective extends this logic, arguing that transition risk can act as a catalyst for organizational and technological change that converts external pressure into opportunities for building sustainable advantages [

35].

The relative dominance of these competing mechanisms determines the aggregate impact of transition risk on green innovation decisions. This complexity deepens when we consider that firms facing identical climate transition risk signals may respond very differently, based on their managerial cognition and agency considerations.

Managerial interpretation of uncertainty plays a pivotal role in determining which theoretical framework dominates the decision-making processes. Managers with risk-averse cognitive biases tend to emphasize the costs and potential losses associated with premature investment, naturally gravitating toward real options strategies that prioritize flexibility and patience [

36]. These managers frame uncertainty primarily as a threat to be managed through careful timing and risk mitigation. Conversely, managers with entrepreneurial orientations or opportunity-focused mindsets interpret the same uncertainty as a source of competitive advantage, leading them to pursue growth options strategies characterized by proactive investment, despite incomplete information [

37]. This cognitive framing fundamentally shapes how environmental signals are translated into strategic action.

Agency theory provides an additional layer of explanation for these divergent responses [

33]. The separation of ownership and control that is inherent in modern corporations introduces agency costs that systematically influence option exercise decisions. Managers, acting as agents for shareholders, may rationally prioritize their own short-term interests over long-term firm value maximization. Engaging in risky, long-term green R&D investments, while potentially beneficial for shareholders, might jeopardize a manager’s current position or compensation structure [

38]. This agency-driven short-termism naturally aligns with the “option to wait” strategy, even when immediate investment would serve the firm’s long-term interests. Consequently, agency problems can systematically amplify tendencies toward real options strategies at the expense of value-creating growth options [

39].

These theoretical considerations collectively suggest that opposing firm-level responses to climate transition risk can and should coexist within any given sample of firms, rendering the aggregate effect theoretically uncertain. Some firms will increase their green innovation efforts, because growth option potential, competitive pressure, and opportunity-focused managerial cognition create powerful incentives for immediate action. Simultaneously, other firms will reduce or delay such investments, because the value of waiting, resource constraints, and agency-driven short-termism create equally compelling incentives for patience. Since both strategic orientations are theoretically justified and empirically observable in market contexts, the ultimate direction and magnitude of climate transition risk’s effect on green innovation depends critically on firm-specific factors that influence its sensitivity to climate risk signals.

Given this theoretical ambiguity and the competing mechanisms that we have identified, we propose the following competing hypotheses to guide our empirical investigation.

H1a. Climate transition risk positively influences corporate green innovation.

H1b. Climate transition risk negatively influences corporate green innovation.

Having established why the aggregate effect can be ambiguous, we next examine the specific mechanisms through which transition risk affects green innovation. We identify two key behavioral mechanisms that drive differential firm responses.

First, managerial cognitive framing determines the strategic orientation. Risk-averse managers interpret transition risks as threats requiring cautious approaches and tend to show negative sensitivity. In contrast, opportunity-focused managers view risks as competitive advantages and demonstrate positive sensitivity [

36]. Second, agency considerations influence decision-making horizons. Severe agency problems promote short-term thinking and negative responses, while aligned interests encourage long-term strategies and positive sensitivity [

33]. These behavioral mechanisms operate through two empirically testable channels: financing constraints and R&D investment decisions. We examine these as complementary pathways for understanding heterogeneous firm responses.

On the financing side, these behavioral mechanisms manifest in differential constraint patterns. For firms with positive sensitivity, opportunity-focused managerial framing and aligned agency interests create eased constraints. From a growth options perspective, positive sensitivity signals that climate transition enhances the value of firms’ growth options and strategic flexibility. This increased option value improves debt capacity by reducing default risk, as the upside potential from green innovation creates valuable contingent claims that function as embedded call options for future market opportunities. The asymmetric payoff structure of these options—with limited downside risk but substantial upside potential—translates into lower required risk premiums and enhanced lending terms [

40]. Financial institutions increasingly incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into lending decisions, offering preferential rates to firms demonstrating credible green transformation capabilities [

41,

42].

By contrast, risk-averse framing and agency misalignment in negative sensitivity firms lead to tighter financing constraints. From a real options perspective, negative sensitivity signals that climate transition diminishes the value of firms’ existing assets and growth options. This erosion of option value restricts debt capacity by increasing the default risk, as potential stranded assets create contingent liabilities that function as embedded options on declining market segments [

40]. Banks recognize this diminished option value through deteriorated credit assessments, viewing firms with negative sensitivity as holding portfolios of potentially impaired assets in contracting markets [

43]. The asymmetric risk structure—with substantial downside exposure but limited upside protection—translates to higher required risk premiums and restrictive lending terms [

44]. These observations lead to the following mechanism hypothesis on financing.

H2. Climate transition risk affects corporate green innovation through the financing constraints channel. Constraints ease with positive sensitivity and tighten with negative sensitivity.

On the innovation input side, the underlying behavioral mechanisms drive differential R&D investment patterns. For firms with positive sensitivity, long-term oriented managers with aligned incentives pursue higher R&D intensity. From a growth options perspective, these firms view green R&D investments as opportunities to acquire valuable growth options in emerging markets, while the strategic logic centers on option creation rather than immediate returns. Firms with positive sensitivity view green R&D as essential for building a durable competitive advantage, strategically increasing R&D intensity to develop low-carbon technologies that align with the anticipated policy trajectories [

35]. Facing Knightian uncertainty, these firms leverage external uncertainty as a differentiation opportunity, with R&D serving as a commitment device to capture nascent market opportunities and shape industry standards through patents and alliances [

45]. Each R&D project functions like acquiring call options on future technological trajectories, where early investment secures positions that enable learning-by-doing and scale economies as markets mature [

24,

32].

By contrast, short-term-focused managers facing agency pressures in negative sensitivity firms exhibit reduced and deferred R&D investment. This pattern reflects the real options logic of waiting under uncertainty, amplified by the behavioral and organizational frictions described above. When transition risk threatens existing assets, the option value of delaying irreversible R&D investments increases significantly [

23,

46]. Risk-averse managers exhibiting loss aversion may overestimate the sunk costs and downside risks of green innovation while underestimating long-term returns, leading to systematic deferral and project cancelation [

47,

48]. Agency frictions from misaligned evaluation horizons intensify this short-term bias, as managers facing short-term evaluation horizons favor incremental improvements or compliance fixes over uncertain green R&D with extended payback periods [

33,

39]. Simultaneously, immediate compliance pressures divert both managerial attention and financial resources toward operational adjustments, crowding out green R&D in resource-allocation decisions [

49,

50]. This results in a strategic preference for preserving flexibility through inaction, rather than committing to potentially obsolete R&D investments.

H3. Climate transition risk affects corporate green innovation through the R&D investment channel. R&D increases with positive sensitivity and decreases with negative sensitivity.

8. Conclusions and Implications

The literature on the climate risk–innovation nexus remains divided, with some studies reporting negative effects and others documenting positive effects, but it lacks a unified theoretical explanation [

12,

18]. We reconcile these conflicting results by proposing a firm-level sensitivity framework that distinguishes firms with positive sensitivity to public climate attention from those with negative sensitivity.

Drawing on an integrated framework centered on option-theoretic perspectives (real and growth options) [

23,

24], we posit that corporate green innovation reflects a complex trade-off between short-term costs and long-term benefits, and between conservative and proactive strategies. This theoretical foundation provides a coherent account of how systematically opposing firm-level responses can, in aggregate, yield an overall null effect in our setting and in the prior studies.

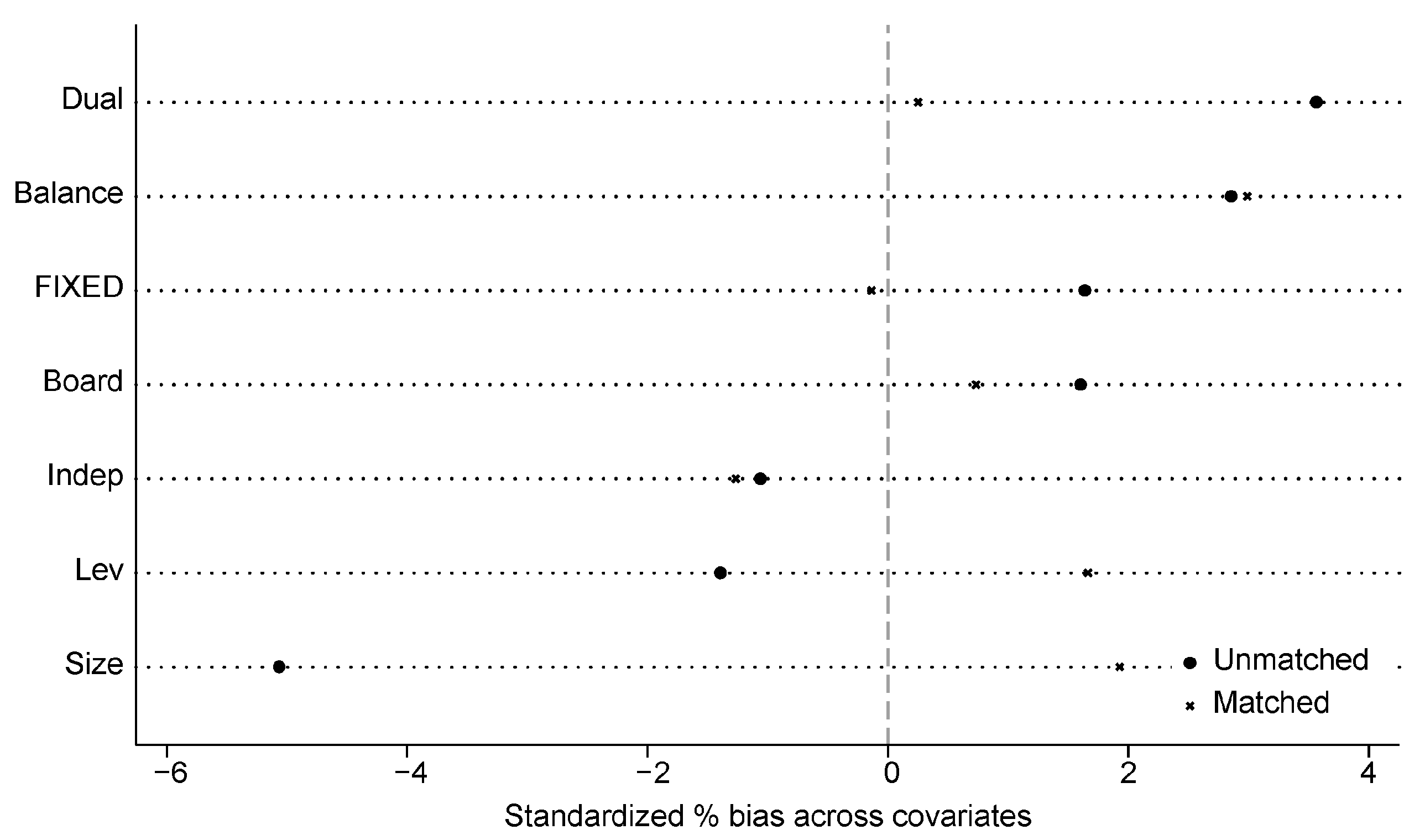

Our analysis reveals a statistically insignificant aggregate relationship between climate transition risk and corporate green innovation, which helps to reconcile the conflicting evidence in the literature [

9,

13]. Decomposing the aggregate effect shows that a one-unit increase in positive sensitivity (

) is associated with an approximately 5.4 percent increase in green innovation, whereas a comparable increase in negative sensitivity (

) is associated with a 5.0 percent reduction. These opposing patterns are consistent with our theoretical expectations: evidence for positive sensitivity (

) accords with growth options [

24], whereas evidence for negative sensitivity (

) accords with real options and agency costs [

23]. This polarization effect is robust across instrumental-variables analyses, alternative measurements, and alternative sample constructions, and it underscores that ignoring firm-level heterogeneity may bias inference.

Beyond establishing this core finding, our study clarifies the mechanisms through which these effects operate. We show that financing constraints and R&D investment serve as important channels that operate in opposite directions for different sensitivity types. Positive sensitivity is associated with eased financing constraints and higher R&D expenditures, thereby promoting green innovation, whereas negative sensitivity is associated with tighter financing conditions and lower R&D investment, thereby dampening innovation. These mechanism results are consistent with the financing constraints and R&D investment channels developed in

Section 2.

Additional heterogeneity analyses reveal that these effects are particularly pronounced in specific contexts. The impact is stronger among manufacturing firms, non-state-owned enterprises, firms without financial backgrounds, and firms located in less-developed central-western regions, as well as in low-marketization provinces. These patterns suggest that firms facing greater transition pressures or operating under tighter constraints exhibit more distinctive responses to climate risk signals. In addition, our analysis of the policy shock around the Paris Agreement, which represents a plausibly exogenous shift in the regulatory environment, shows that increased regulatory uncertainty amplifies the negative effect that is associated with negative sensitivity, consistent with the higher value of the “option to wait” predicted by real options theory [

23].

Collectively, this study provides an integrated theoretical and empirical framework that reconciles the inhibition-versus-promotion debate by introducing a directional sensitivity perspective. Our findings carry important implications for policy and practice. First, policymakers should move beyond uniform, “one-size-fits-all” climate policies. Regulatory frameworks should be designed to account for firm-level heterogeneity. For instance, opportunity-perceiving firms may respond best to innovation-led incentives like R&D grants, while threat-perceiving firms may require risk-mitigation support to overcome initial barriers. Second, governments should enhance green finance infrastructure to alleviate identified constraints, focusing on expanding instruments like green loans and sustainability bonds. These financial initiatives address the identified constraints and provide the necessary capital for firms that are committed to green initiatives, thereby reducing the inclination for “wait-and-see” behavior and ensuring a smoother transition to sustainable practices. Third, at the corporate level, managers must integrate climate-related risks and opportunities into their strategic planning and focus on enhancing internal financial resilience. This entails prioritizing R&D investment and ensuring access to capital for proactive transition strategies. Strengthening internal financial buffers is essential to help firms manage climate-related market volatility and to ensure that they are better prepared to navigate future regulatory and market changes.