Abstract

Rural areas in Brazil, like many parts of the Global South, face profound socioeconomic and demographic transformations, including depopulation, aging populations, and infrastructural deficits. These challenges are particularly acute for traditional communities such as quilombolas—descendants of Afro-Brazilian maroons—whose territorial rights and cultural survival remain vulnerable. This study examines socioeconomic and demographic changes in two traditional quilombola communities—Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol—in the municipality of Rio Espera, Minas Gerais, and their interaction with rural development policies. Using a mixed-methods approach combining census data (IBGE 2022), geoprocessing (QGIS, MapBiomas), and fieldwork—including semi-structured interviews with 16 households and community leaders—we analyze population trends, land use dynamics, access to services, and local strategies of resistance. Results reveal a dual dynamic: structural pressures such as youth outmigration, aging, and inadequate infrastructure coexist with endogenous resilience strategies, including agroecological farming, productive diversification, and cultural revitalization through festivals and community associations. Programs such as the Food Acquisition Program (PAA) and National School Feeding Program (PNAE) have provided critical support, but their impact is amplified by community ownership and participation. We conclude that sustainable rural development in quilombola territories depends on integrating context-sensitive public policies with endogenous social, productive, and cultural dynamics. This calls for a territorialized, participatory approach that recognizes quilombola communities not merely as beneficiaries, but as agents of sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Rural development in Brazil has long been shaped by top-down policy interventions, from agricultural modernization programs to contemporary social welfare and environmental conservation initiatives. While these policies aim to address poverty, inequality, and sustainability, their impacts on marginalized rural communities are often uneven and poorly understood. This is particularly true for quilombola communities—Afro-Brazilian populations descended from maroon settlements—whose historical resilience and territorial practices are frequently overlooked in mainstream development planning. Although recent scholarship has begun to document the socioeconomic and demographic transformations affecting these communities, there remains a critical gap in understanding how these transformations interact with endogenous community responses to external policy interventions. This study addresses this gap by examining how two quilombola communities in Minas Gerais navigate processes of demographic decline, economic precarity, and land use change not merely as passive subjects of policy, but as active agents engaged in the reinterpretation, appropriation, and strategic use of public programs. By focusing on this dynamic interplay, our research offers a nuanced perspective on rural resilience that bridges structural constraints and local agency—a dimension of rural development that has been underexplored in the existing literature.

With the intensification of globalization and urbanization processes, rural areas in Brazil have undergone significant transformations in their socioeconomic and demographic structures. These changes, historically associated with rural-to-urban migration and the modernization of agriculture, have directly affected territorial configurations, ways of life, and productive practices of traditional rural populations. In Minas Gerais, these transformations take on specific characteristics due to the diversity of environmental, historical, and cultural contexts that define the state [1,2].

According to the Brazilian Institute for Applied Economic Research [3], renewed public policies focused on family farming and the strengthening of traditional communities have sought to correct historical imbalances in the distribution of resources and opportunities in rural areas. Recent public policies have prioritized environmental sustainability, food sovereignty, and social inclusion as structural pillars of rural development. However, structural challenges persist, such as land concentration, the expansion of predatory activities, and the weakening of local socio-productive networks—factors that strongly impact rural communities in Minas Gerais.

At the same time, as highlighted by Cruz and Costa [4], current paradigms of territorial development face limitations when applied to contexts of “demographic contraction” or “rural depopulation.” These authors suggest adopting strategies that value non-economic dimensions of development—such as quality of life, community cohesion, and emotional ties to the territory—elements essential to the permanence and resilience of traditional rural communities.

Thus, this study aims to understand how socioeconomic and demographic changes manifest in two traditional rural quilombola communities, and how they interact with and are reshaped by rural development policies implemented in Minas Gerais. Crucially, we examine not only how policies affect communities, but also how communities actively interpret, adapt, and reconfigure these policies to align with their own territorial and cultural logics. The approach adopted emphasizes an analysis that recognizes territory as a historical and symbolic construction, and rural development as a multidimensional and participatory process [1].

Research Objectives, Hypotheses, and Manuscript Structure

This study aims to empirically analyze the socioeconomic and demographic transformations in the quilombola rural communities of Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol, located in the municipality of Rio Espera, Minas Gerais, Brazil. It further seeks to assess how national and local rural development policies intersect with local territorial practices and shape community resilience in the context of rural depopulation.

To achieve this, the following specific research objectives guide the analysis:

To identify and quantify recent demographic trends (e.g., population change, age structure, migration patterns) in Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol using census and municipal data (1970–2022);

To map and analyze land use and land cover changes in the study area between 2000 and 2023 using geoprocessing techniques;

To evaluate the implementation and local impacts of key rural development policies—particularly the Food Acquisition Program (PAA), the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), and Technical Assistance and Rural Extension (ATER)—on productive and organizational practices;

To document community-driven strategies of resistance, adaptation, and economic multifunctionality through qualitative fieldwork;

To assess the feasibility of a sustainable and inclusive territorial development model in contexts of demographic contraction, informed by the Rural Development Index (RDI) framework proposed by Renzi and Parré [1].

Based on these objectives, the study tests the following research hypotheses:

H1:

Quilombola communities experiencing greater integration with public procurement and technical assistance programs will demonstrate higher levels of socioeconomic resilience and productive diversification.

H2:

Despite regional trends of rural depopulation, communities that maintain strong cultural institutions and collective land management will exhibit greater capacity for endogenous development.

H3:

Land use changes in Rio Espera reflect a divergence between municipal-level trends (e.g., expansion of silviculture and pasture) and community-level practices (e.g., agroecological polyculture), indicating a mismatch between policy priorities and local sustainability models.

The relevance of this research lies in its mixed-methods approach, which integrates quantitative data (demographic censuses, land use maps) with qualitative insights (interviews, participant observation) to provide a comprehensive understanding of rural quilombola territories. By applying the RDI framework [1], the study contributes to debates on territorial inequality and inclusive rural development, offering empirical evidence for policy design that aligns economic growth with social justice and environmental sustainability [4].

This article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical and policy context of rural development in Brazil; Section 3 outlines the study area and methodology; Section 4 details the demographic and land use trends; Section 5 discusses the impacts of public policies; Section 6 analyzes community-based strategies; and Section 7 provides a comparative discussion of findings in relation to existing literature. The conclusion evaluates the achievement of research objectives and offers policy and research implications.

2. Research Background

2.1. Quilombola Communities: Identity, Territory, and Livelihoods

Contemporary quilombola communities are established in rural, peri-urban, or urban contexts across Brazil, where they develop economies based on subsistence and/or commercial agriculture, along with other social reproduction strategies [5]. Their cultural expressions maintain a strong connection to African heritage, interwoven with Indigenous and Portuguese influences, forming a unique identity rooted in resistance and resilience [5,6,7].

The legal recognition of a group as quilombola, as established by Article 68 of the 1988 Federal Constitution and Presidential Decree No. 4887/2003 [7], is based on self-identification and anthropological reports attesting to their historical trajectory and ancestry linked to slavery [8,9]. These legal instruments are crucial for securing land rights and ensuring the permanence of these communities in their traditionally occupied territories. However, as traditional communities, quilombolas often face restrictive environmental policies that impact their livelihoods and cultural practices [10,11,12].

In the context of Minas Gerais, quilombola communities such as those in Rio Espera integrate collective agricultural production, agroecological practices, and deep cultural ties to the territory—forms of resistance against processes of modernization and market exclusion [13]. This way of life reflects a multidimensional understanding of rural development, one that extends beyond economic output to include identity, autonomy, and territorial belonging [3].

2.2. Rural Transformation: Depopulation, Multifunctionality, and Economic Diversification

Migration processes are among the most significant factors transforming Brazilian rural areas [14]. The intensification of rural-to-urban migration has led to “rural depopulation,” characterized by the loss of economically active populations, demographic aging, and the decline of public services in small localities [15]. This trend is particularly pronounced in Minas Gerais, where employment and educational opportunities are concentrated in urban centers, encouraging youth out-migration and weakening the sociocultural foundations of rural communities [15,16,17].

Yet, as Cruz and Costa [3] argue, contexts of “territorial contraction” should not be interpreted solely as decline, but also as opportunities for reconfiguration. In response to demographic and economic pressures, rural areas have increasingly adopted diversified and multifunctional economic models. Renzi and Parré [1] show that rural development now relies on a combination of agricultural and non-agricultural activities, including tourism, handicrafts, and local services.

This shift reflects a broader transformation in the functions attributed to rural space—extending beyond food production to include environmental stewardship, cultural preservation, and community-based resource management. IPEA (2024) [18] emphasizes that multifunctionality can serve as a strategy for economic strengthening, inclusion, and sustainability, particularly in traditional communities where agroecology and collective management of common goods play central roles.

2.3. Policy Frameworks and Institutional Responses

Public policies play a decisive role in shaping rural territorial dynamics [19,20]. Programs focused on family farming, land regularization, and productive inclusion—such as PRONAF, PAA, PNAE, and the Brasil Quilombola Plan—have contributed to reducing historical inequalities, although outcomes remain uneven across regions [15]. The institutional strengthening of rural councils and community associations has also enhanced local agency and cooperation networks.

However, the effectiveness of these policies depends on their ability to adapt to territorial specificities. As Renzi and Parré [1] observe, the uniform implementation of national programs, without accounting for regional and sociocultural differences, often reproduces inequalities and limits impact. In quilombola territories, where land tenure insecurity and limited access to technical assistance persist, context-sensitive and participatory approaches are essential.

Moreover, the policy landscape has undergone significant shifts since 2003—from expansion and rights recognition in the 2000s to institutional setbacks and funding reductions after 2016. This volatility underscores the need for resilient local institutions and adaptive strategies, which this study explores through the experiences of Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol.

3. Theoretical Framework

The study of rural development has evolved into a complex, interdisciplinary field that recognizes the phenomenon as a multidimensional, multi-actor, and multi-level dynamic, integrating economic, social, environmental, and cultural factors [1]. This conception expands beyond the traditional focus on agricultural production, incorporating dimensions such as quality of life, territorial equity, sustainability, and social innovation. It reflects a global shift in development thinking—from top-down, productivity-centered models toward integrated, place-based, and participatory approaches that acknowledge the agency of local actors and the embeddedness of development in historical and cultural contexts.

In Brazil, this paradigmatic evolution is evident in recent institutional and political restructuring. Ref. [3] emphasizes that the re-establishment of the Ministry of Agrarian Development and Family Farming marks a significant policy reorientation aimed at integrating environmental sustainability and social justice into rural development strategies. This vision breaks with the previous model centered solely on productivity and advances toward promoting family-based and agroecological farming, linked to the preservation of traditional territories. These shifts are not merely administrative but represent a theoretical commitment to multifunctional rural development, where agriculture serves not only economic functions but also ecological, social, and cultural roles [21]—a concept echoed in IPEA’s call for holistic policy integration.

A central challenge in applying such integrated models lies in their translation across highly heterogeneous rural landscapes. As observed by Cruz and Costa [4], development paradigms must consider the territorial and identity-specific characteristics of each community, recognizing that local dynamics are shaped by multiple factors—historical, cultural, and environmental—that influence different rhythms and trajectories of transformation. Their framework of “local development in contexts of contraction” offers a particularly relevant lens for understanding marginalized communities facing population decline, aging populations, and infrastructure shortages, yet maintaining social cohesion and community innovation capacity. This perspective underscores the importance of endogenous development theory, which posits that sustainable transformation must emerge from within communities by leveraging local knowledge, networks, and symbolic resources.

3.1. Geographic Factors and Rural Development

Geographic and territorial factors decisively influence rural development, shaping both productive opportunities and communities’ capacity to integrate into regional economic circuits [22,23]. In Minas Gerais, the diversity of topography, unequal distribution of infrastructure, and distance from urban centers shape particular development dynamics—especially in areas of traditional quilombola occupation [24,25].

According to Renzi and Parré [1], the Brazilian rural space is marked by intense territorial disparities, in which accessibility, centrality, and population density directly influence quality of life and the availability of public services. Spatial heterogeneity makes it essential to adopt policies adapted to the local scale, considering the environmental and sociocultural specificities of each territory. This recognition aligns with the broader theoretical principle of territorial differentiation, which challenges one-size-fits-all development models and calls for geographically nuanced interventions.

Notes [4] that physical factors such as topography, soil quality, and water availability are crucial in structuring rural activities and formulating development policies. Territorial analysis, therefore, extends beyond economic aspects to include an understanding of the landscape as an expression of the relationship between society and nature—a fundamental dimension for rural sustainability. This ecological–social dialectic reflects a core tenet of political ecology and sustainable development theory, further reinforced by national policy discourse.

3.2. Territorial Diversity and Differentiated Policies

Regional inequalities in Brazil’s rural areas demand territorialized policies that recognize the diversity of natural and sociocultural conditions [26]. As IPEA (2024) [15] points out, effective public policy formulation requires detailed territorial diagnostics capable of guiding investments in infrastructure, technical assistance, and productive inclusion, respecting the vocation of each region. This operational emphasis on diagnostic tools reflects a governance turn in development theory, where data-driven, context-sensitive planning replaces blanket interventions.

Renzi and Parré [1] emphasize that the Rural Development Index (IDR) is a relevant tool in this process, as it enables the identification of local inequalities and potentials based on economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Data analysis shows that municipalities with greater productive diversity and a strong presence of family farming tend to perform better on well-being and sustainability indicators. This empirical insight supports the theoretical argument that economic diversification and social embeddedness are key drivers of resilient rural development, reinforcing the value of policies that strengthen local economies and community institutions.

3.3. Territory as a Social and Symbolic Construction

The contemporary understanding of rural development incorporates the symbolic dimension of territory, recognizing it as a space of meaning, memory, and belonging. According to Cruz and Costa (2025) [3], territory is simultaneously a material and immaterial resource that shapes identities and guides social practices [27]. This approach transcends a purely economic view and integrates affective and cultural values into the analysis of development dynamics.

This configuration results from historical processes of occupation that have transformed the landscape over time [20], evolving beyond a mere system of objects into an articulated system of actions [10]. The territory functions as a dynamic stage of contestation and meaning, whose essence is defined by identity and population attachment [28]. It represents not only physical space but also the material and emotional foundation of daily life [20], serving as the basis for work, housing, and symbolic exchange.

This conceptualization resonates with Lefebvrian and post-structural understandings of space as socially produced, and with Latin American critical geography that emphasizes territory as a site of resistance and identity formation—particularly among historically marginalized groups such as quilombola communities. By framing territory as a lived, contested, and symbolic construct, this section grounds the analysis in a critical, culturally sensitive theory of place, which is essential for understanding how rural communities assert agency and reimagine development on their own terms.

4. Literature and Policy Review

4.1. Strategies and Guidelines for Rural Development

Sustainable rural development in Brazil depends on integrated public policies that reconcile economic growth, environmental preservation, and social justice. According to the authors, the State plays a central role in promoting equity and strengthening rural communities through credit, innovation, and sustainability. The structure of rural policies is supported by pillars that integrate technology, territorial cohesion, socio-environmental sustainability, productive integration, and social equity [29,30].

4.2. Historical Trajectory of Rural Development Policy

Brazilian rural development policy has evolved through distinct phases, reflecting broader shifts in national development paradigms and socio-political struggles. This evolution is marked by alternating periods of policy advancement and rollback, deeply influencing the socioeconomic conditions of rural populations, particularly traditional communities such as quilombolas.

4.2.1. Period of Rights Realization (1960–1980)

This period laid the legal foundations for rural citizenship [31] was the first comprehensive legal framework to extend labor rights to rural workers, marking a significant step toward social inclusion. In 1971, the creation of the Rural Worker Assistance Fund (FUNRURAL) established the first social security system for rural workers, representing a fundamental advancement in social protection, albeit initially limited in coverage and equity [32].

4.2.2. Democratization and Recognition (1980–2000)

The 1988 Federal Constitution represented a turning point in rural policy, enshrining agrarian reform as a constitutional principle and recognizing the social function of land—a concept that redefined property rights in favor of social justice and environmental sustainability. This era also saw the rise of powerful social movements: the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), founded in 1984, and the National Confederation of Agricultural Workers (CONTAG), which became central actors in advocating for land rights and rural development [32].

4.2.3. Consolidation of Structural Policies (2000–2016)

This phase witnessed the institutionalization of policies supporting family farming and sustainable development. Key initiatives included:

The National Family Farming Strengthening Program [33] which became the primary credit instrument for small-scale producers, consolidating family farming as a recognized political and economic category.

The National Policy for Technical Assistance and Rural Extension [34], which reoriented rural extension services toward agroecology, sustainability, and participatory approaches.

The Food Acquisition Program [34] and the National School Feeding Program [35,36] which created institutional markets linking family farming to public food procurement, enhancing income stability and food security [32].

These programs reflected a shift toward integrated, rights-based rural development that acknowledged the role of smallholders in national sustainability.

4.2.4. Rollbacks and Resistance (2016–Present)

Since 2016, rural policies have faced significant setbacks. Participatory governance mechanisms were dismantled, public spending was frozen, and key institutions—such as the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA)—were weakened. Concurrently, agribusiness interests gained dominance, evidenced by the expansion of pesticide use and the relaxation of environmental licensing requirements [37].

Despite these challenges, resistance and innovation have persisted. State and municipal governments have maintained critical programs, and short food supply chains, cooperatives, and community-supported agriculture have expanded, demonstrating resilience and alternative development pathways.

4.3. Key Pillars of Sustainable Rural Development

Contemporary debates on rural development in Brazil center on the tension between two contrasting models: one driven by export-oriented agribusiness and financial capital, and another rooted in family farming, agroecology, and social justice. Sustainable rural development, as argued by Cunha and Fornazier (2025), requires a policy framework that integrates five core pillars: technological innovation, territorial cohesion, socio-environmental sustainability, productive integration, and social equity [29,30,31,32,33].

4.3.1. Land Tenure Security and Intergenerational Succession

Land regularization remains a fundamental precondition for sustainable rural development. Secure land tenure enables long-term investment, strengthens community identity, and reduces vulnerability to displacement. Support for rural succession—ensuring youth can inherit and work the land—is equally critical to counter rural exodus and demographic aging. Programs such as PAA and PNAE have contributed to youth retention by creating stable markets for local production, thereby enhancing the economic viability of staying in rural areas [31,32,33,34].

4.3.2. Productive Diversification and the Solidarity Economy

Cooperativism and associativism are central to strengthening the solidarity economy and diversifying income sources in rural communities. These models reduce dependence on volatile commodity markets and promote collective agency. The National Policy for Technical Assistance and Rural Extension (ATER) plays a key role by integrating agroecological practices, social innovation, and access to rural credit, thereby expanding productive opportunities and fostering resilience against exclusionary agricultural models [38,39].

4.3.3. Urban–Rural Integration and Territorial Cohesion

Overcoming the urban–rural dichotomy is essential for balanced regional development. Abramovay (2003) emphasizes that strengthening local potentials—through integrated policies on infrastructure, education, health, and digital connectivity—is crucial for ensuring rural citizenship and promoting territorial cohesion [40]. Equitable access to public services not only improves quality of life but also enhances the attractiveness of rural areas for younger generations.

4.4. Current Challenges and Future Directions

The current rural policy landscape reflects what Firmiano (2022) describes as the “reconfiguration of the agrarian question,” where the countryside has become a focal point of structural contradictions within dependent capitalism. Despite advances such as the ABC Plan (Plano ABC)—launched in 2010 to promote low-carbon agriculture through sustainable credit—and initiatives like RenovAgro, which incentivize green innovation, implementation gaps persist. These policies often fail to reach small-scale producers due to bureaucratic barriers, lack of technical support, and uneven territorial coverage [28,31].

Moreover, neo-developmentalism has not fundamentally broken with the agro-export model, reinforcing Brazil’s dependency in the global division of labor. Sustainable rural credit, while expanded, continues to favor larger producers and lacks sufficient integration with agroecology and environmental conservation goals (Cunha & Fornazier, 2025) [32].

The future of rural development in Brazil depends on re-centering agrarian reform and agroecology as structural pillars of national policy. This requires rebuilding participatory governance, strengthening dialogue between the State, academia, and civil society, and empowering social movements such as La Vía Campesina, MST, and CONAQ as key agents of change [32]. Only through such a territorialized, inclusive, and rights-based approach can rural development become truly sustainable—particularly for vulnerable communities like the quilombolas, whose survival and resilience are central to Brazil’s rural future.

5. Research Methods and Data Sources

This study adopts a mixed-methods approach to investigate rural sustainability and community resilience in two traditional quilombola communities in southeastern Brazil. By integrating quantitative and qualitative data, the research aims to understand how historical, institutional, and environmental factors intersect to shape local development trajectories within the broader context of national rural policy.

5.1. Research Design and Methodological Approach

A convergent parallel mixed-methods strategy was employed, combining qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis to provide a comprehensive understanding of rural development dynamics. This approach enables triangulation of findings, enhances validity, and allows for a richer interpretation of complex socio-environmental processes.

The methodology integrates three core components:

Geospatial analysis using remote sensing and GIS tools;

Field observations and participatory engagement;

Semi-structured interviews with key community stakeholders [Appendix A].

This integrative framework facilitates a multidimensional and multilevel analytical perspective, enabling the systematic examination of policy implementation mechanisms, territorial management practices, and their real-world impacts on livelihoods and land use in marginalized rural territories.

QGIS (v3.28) was used as the primary geospatial tool for data visualization, mapping, and spatial analysis. It enabled the creation of intuitive cartographic representations of the study area, supporting both data interpretation and community engagement.

The integration of these distinct data types presented a methodological challenge, primarily concerning the reconciliation of differing scales: the geospatial and census data (e.g., from IBGE and MapBiomas) provide a regional, macro-level perspective on demographic and land-use trends, while the semi-structured interviews and field observations offer a localized, micro-level understanding of community experiences and decision-making. To address this, our analysis focused on using the macro-level patterns identified through geospatial tools as a contextual foundation. These patterns—such as observed land cover changes or demographic shifts—were then explored and interpreted through the narratives and insights gathered from community stakeholders. This process allowed the qualitative data to provide meaning and context to the quantitative observations, resulting in a more holistic analysis of the interplay between structural forces and local realities in the quilombola territories.

While geospatial and census data provide the structural backdrop of rural transformation, semi-structured interviews serve as the primary analytical lens through which this study interprets the lived experience of policy, territorial belonging, and intergenerational change. Guided by a constructivist grounded theory approach, the interview narratives were not merely illustrative but constitutive of the study’s core arguments—particularly regarding how quilombola communities negotiate, resist, or reconfigure state interventions. This epistemological stance positions community voices as central to understanding the “how” and “why” behind observed demographic and land-use trends.

5.2. Research Data and Information Sources

5.2.1. National-Level Data

Official Statistics: The statistical foundation of this research relies on official data published by national institutions. The primary source is the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), whose periodic surveys—such as the Agricultural Census, the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD), and the National Accounts—provide a comprehensive and reliable picture of rural development in Brazil, serving as a basis for large-scale contextualization.

Demographic Census Data: This article’s analysis is based on microdata from the most recent Demographic Census, conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 2022. Using this source, the study investigates the evolution of critical indicators for rural development, namely:

- (i)

- Agricultural modernization, observed through variables such as land use and changes in crop structure;

- (ii)

- Access to basic health and education services;

- (iii)

- Economic restructuring, analyzed through the dynamics of the agricultural and industrial sectors in the context of transformations in asset structure and demographic profile.

5.2.2. Local-Level Data

Land Use and Land Cover:

To analyze spatial dynamics in the state of Minas Gerais, particularly in the municipality of Rio Espera—where the two quilombola communities of Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol are located—land use and land cover (LULC) data for the years 2003, 2013, and 2023 were obtained from the Interactive Geographical Platform (PGI) of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) and the MapBiomas project. These datasets provide annual land cover classifications at 30-m resolution, enabling a detailed assessment of territorial change over two decades.

Within QGIS 3.40.6, the LULC maps were processed through spatial clipping to the study area boundaries, followed by reclassification into broader categories relevant to rural development: natural vegetation, agricultural land (including subsistence farming and polyculture), pasture, commercial forestry (mainly eucalyptus plantations), and built-up areas. Area calculations (in hectares) were performed for each class and year, allowing for quantitative comparison of land use transitions. Change detection maps were also generated to visualize patterns of deforestation, agricultural expansion, or abandonment.

Temporal Policy Context and Community Selection Criteria:

The temporal analysis spans 2003–2023, structured in ten-year intervals (2003–2013–2023). The starting point, 2003, coincides with the issuance of Decree No. 4887, which regulates the land titling of quilombola territories and marks the beginning of strengthened public support for sustainable rural development in traditional communities. The period 2003–2013 saw the expansion of key programs such as Brasil Quilombola, PRONAF (National Program for Strengthening Family Farming), and the Family Farming Crop Plan, contributing to advances in productive inclusion and land regularization.

In contrast, the period 2013–2023 has been marked by institutional setbacks and policy discontinuity, particularly after 2016, including the restrictive Normative Instruction No. 88/2020 and significant reductions in funding for rural development and technical assistance. This 20-year timeframe enables an evaluation of how shifts between policy expansion and contraction have influenced local land use and territorial management strategies.

The selection of the two communities—Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol—was based on their official recognition as quilombola territories, geographic proximity within the same municipality, and divergent trajectories of social organization and resilience. While both face challenges related to depopulation and limited infrastructure, Moreiras has developed stronger collective institutions and agroecological initiatives, whereas Buraco do Paiol exhibits greater vulnerability due to weaker community cohesion and lower program integration. This comparative design allows for insights into the role of local agency in mediating structural pressures.

Qualitative Data Collection and Sampling Strategy:

Fieldwork included semi-structured interviews with 16 residents, including household heads, youth, elders, women leaders, and representatives of community associations and cooperatives. Participants were selected through a combination of purposive and snowball sampling to ensure diversity in age, gender, land tenure status, and participation in public policies. Sampling continued until thematic saturation was achieved, ensuring comprehensive coverage of key experiences and perspectives.

Interviews were guided by a thematic protocol focusing on: (1) demographic changes and migration patterns; (2) agricultural practices and access to land; (3) experiences with public programs such as PAA, PNAE, and ATER; (4) access to education and health services; and (5) cultural and organizational initiatives (e.g., Congado festival, cooperative groups). All interviews were conducted in Portuguese, recorded with informed consent, and transcribed verbatim for thematic analysis.

This mixed-methods approach—integrating geospatial analysis, policy review, and qualitative fieldwork—ensures a robust and context-sensitive understanding of rural transformation in quilombola territories.

5.3. Study Area and Case Selection

The research focuses on two traditional quilombola communities—Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol—located in the municipality of Rio Espera, in the state of Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil. These communities were selected based on the following criteria:

Legal recognition or active participation in the land titling process under Decree No. 4887/2003, which recognizes collective territorial rights of quilombola communities;

Presence of active community associations capable of organizing collective action and engaging with public institutions;

Contrasting development pathways: Moreiras emphasizes cultural revitalization and agroecology, while Buraco do Paiol is more oriented toward conventional agricultural production and integration into federal programs such as PRONAF and PAA.

Rio Espera has a rural population of 53.88% and exemplifies broader trends of demographic contraction and rural aging in the interior of Minas Gerais. This context makes it a relevant case for analyzing rural sustainability in historically marginalized territories.

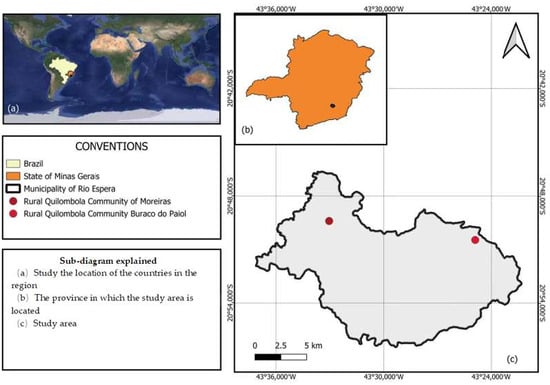

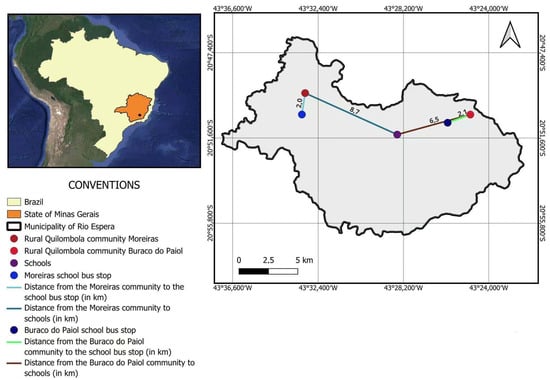

The two quilombola rural communities are located in rural areas of the municipality of Rio Espera, in the state of Minas Gerais. With a total population of 5429 inhabitants, the municipality has a markedly rural demographic and territorial profile: 53.88% of its population (2925 people) resides in areas classified as rural. Within this context, the quilombola population—estimated at 292 people—represents approximately 5.4% of the total residents and about 10% of the municipal rural population, constituting a significant group within the local sociodemographic composition (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the Moreiras Quilombola Rural Community and the Buraco do Paiol Quilombola Rural Community.

The analysis of infrastructure indicators reveals considerable challenges. Only 44% of households are located on paved roads, and 44.91% have access to public street lighting. Urban accessibility is particularly critical, with minimal rates of wheelchair-accessible ramps (5.03%) and obstacle-free sidewalks (1.58%). Tree coverage is uneven, with only 15.92% of households located on streets with five or more trees. Furthermore, cycling infrastructure is entirely absent.

Demographically, the municipality shows a clear process of population aging. The Aging Index, which expresses the ratio between the number of elderly residents (population aged 65 or older) and young people (population aged 0 to 14), multiplied by 100, is 132.75. This value indicates that for every 100 young people, there are approximately 133 elderly individuals, reflecting a mature age structure. The municipality has 985 elderly residents compared to 742 children and adolescents.

5.4. Sampling Strategy for Qualitative Fieldwork

The selection of 16 households for semi-structured interviews was conducted in close collaboration with the presidents of the Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol quilombola associations. We requested that they help identify a diverse group of residents who could provide insights into different aspects of community life, including agricultural practices, access to public services, and participation in government programs. The final sample includes a mix of elders, middle-aged farmers, and younger community members, as well as individuals holding leadership positions in local associations. This purposive sampling approach was designed to capture a range of perspectives on the socioeconomic and demographic changes under investigation.

6. Results

The results presented in this section are grounded in the lived experiences of quilombola residents from Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol, drawn from semi-structured interviews with 16 households conducted in early 2025. Rather than treating demographic trends, land use patterns, or service access as isolated indicators, this analysis centers on how community members themselves interpret these changes—and how public policies have (or have not) shaped their daily realities and future prospects.

6.1. Demographic Trends and Rural Depopulation

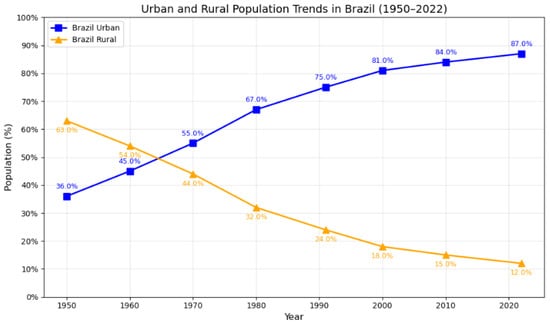

The two quilombola communities—Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol—are embedded within a broader context of rural demographic contraction in Brazil, where the rural population has declined steadily since the 1970s (as shown in Figure 2). Despite Rio Espera maintaining a relatively high rural population share (53.88%, n = 2925), it faces severe depopulation pressures, particularly among youth. Field interviews reveal a pronounced generational imbalance: one resident from Buraco do Paiol noted, “What has changed a lot over the past 40 years is the number of people living here—it has decreased greatly, and only the elderly remain” (Interviewee 8, 2025).

Figure 2.

Proportion of Urban and Rural Population in Brazil, 1950–2022. Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

Field interviews (n = 16 households) and census data reveal a marked generational imbalance. Residents consistently reported a significant reduction in population over the past four decades. One interviewee from Buraco do Paiol noted: “What has changed a lot over the past 40 years is the number of people living here—it has decreased greatly, and only the elderly remain” (Interviewee 8, 2025). Another from Moreiras stated: “Nowadays, there isn’t much to do in the community; the young people are leaving” (Interviewee 1, 2025).

This outmigration is predominantly composed of young adults seeking education and employment in urban centers such as Conselheiro Lafaiete and Belo Horizonte. As a result, the municipal Aging Index stands at 132.75, indicating that for every 100 individuals aged 0–14, there are 133 aged 65 or older. The quilombola population, while small (n = 292), mirrors this trend, with limited youth presence and increasing dependency ratios.

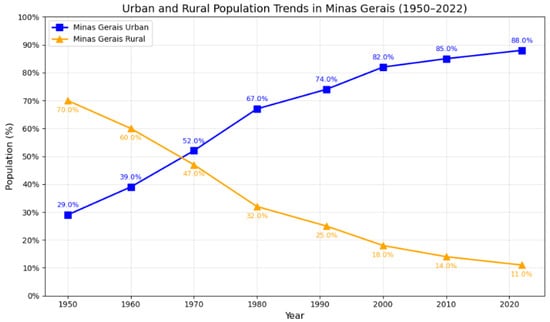

The trajectory of urbanization in Minas Gerais, marked by the continuous decline of its rural population since the 1970s (as shown in Figure 3), conceals significant disparities at the municipal level. While the state of Minas Gerais exhibits high urbanization rates, the municipality hosting the communities studied here is characterized by a relatively persistent rural context. However, this research identifies that such persistence coexists with severe demographic depopulation and aging, resulting from the preferential outmigration of young people. This phenomenon, in turn, generates a vicious cycle of problems: depletion of the workforce, declining agricultural productivity, deterioration of infrastructure and public services, and the gradual erosion of community social fabric.

Figure 3.

Proportion of urban and rural population in the state of Minas Gerais, 1950–2022. Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

The process of rural contraction has significantly impacted the two quilombola rural communities under study. This context is exacerbated by poor road infrastructure, with most access routes consisting of unpaved dirt roads, and by the drastic reduction of employment opportunities in the agricultural sector. In search of better economic prospects and urban lifestyles, young people represent the group most likely to migrate to nearby urban centers. This exodus has created a dual problem within the communities: pronounced population aging and a critical loss of labor.

This scenario of depopulation and demographic change is clearly perceived by the residents themselves. As one interviewee from Moreiras Community stated: “Nowadays, there isn’t much to do in the community; the young people are leaving” (Interviewee 1, 2025). Similarly, a resident from Buraco do Paiol Community noted the long-term shift: “What has changed a lot over the past 40 years is the number of people living here—it has decreased greatly, and only the elderly remain” (Interviewee 8, 2025).

Faced with this context of youth exodus, one of the strategies adopted by the studied quilombola communities to retain young people in their territories is their inclusion in public policies aimed at strengthening family farming. Key programs in this regard include the Food Acquisition Program (PAA) and the National School Feeding Program (PNAE).

From the field data collected, it was observed that, out of the 16 families interviewed, seven benefit from the PAA and two from the PNAE. The distribution of these programs is uneven: five of the seven PAA beneficiaries and both PNAE beneficiary families are located in the Buraco do Paiol Quilombola Community, while the remaining two PAA families belong to the Moreiras Community.

In parallel to these agricultural and economic initiatives, the Moreiras quilombola rural community employs collective cultural strategies as a mechanism to retain its youth. Annual gastronomic festivals and the maintenance of traditional artistic and cultural events—such as the Congado band and the Festa de Santa Efigênia—organized by a strengthened community association, are central to this effort. The management of social media to promote these activities, primarily assigned to young residents, not only increases the visibility of the events but also positions youth in practical and leadership roles within community life. In this way, these initiatives serve a dual purpose: while reinforcing cultural and identity bonds, they also engage young people in the continuity of traditions, transforming them into active agents of their own culture.

6.2. Land Use Dynamics and Socioeconomic Transformation

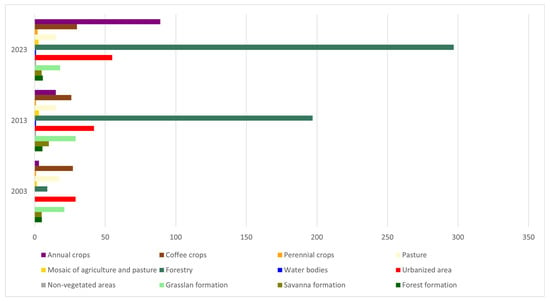

The spatiotemporal analysis of land use and land cover dynamics in the municipality of Rio Espera over the past two decades (2000–2023) (Table 1, Figure 4) reveals a significant transformation in the rural landscape. The study identifies a shift from a historically homogeneous matrix—dominated by cattle ranching and coffee cultivation—toward a more diverse territorial mosaic. This new configuration is characterized by the interplay and tension between forest regeneration, the consolidation of perennial crops—including silviculture—and the recent intensification of temporary (annual) croplands.

Table 1.

Land Use and Land Cover Change in Rio Espera, Minas Gerais (2000–2023).

Figure 4.

Land use and cover in the municipality of Rio Espera Source: MapBiomas; (values of the X axis in hectares—ha)/Perennial crops: various fruit trees, agroforestry systems. temporary crops: corn, beans, cassava, vegetables, among other basic foods.

- 2000 to 2003

During this period, land use in Rio Espera was characterized by the predominance of pasturelands (17,190 ha), areas primarily used for cattle raising. Forest formations (5058 ha)—remnants of dense native tree vegetation—still represented a significant portion of the municipality’s vegetative cover. There was also the presence of grassland formations (21 ha), open areas dominated by grasses and low vegetation, and savanna formations (5 ha), sparse shrubland vegetation. In agriculture, coffee cultivation stood out (27 ha), a traditional perennial crop in the region, alongside other temporary crops (3 ha), such as seasonal maize and beans. Silviculture (297 ha), involving planted forests like eucalyptus and pine, was already present on a small scale. Overall, the landscape was dominated by pastures, with forests and agricultural mosaics occupying smaller proportions.

- 2003 to 2013

This period saw significant changes. Forest formations increased (5502 ha), indicating processes of natural regeneration or conservation policies. Pasture areas decreased (14,987 ha), reflecting the replacement of livestock areas with native vegetation or other land uses. Grassland formations expanded (29 ha), and savanna formations also grew (10 ha), suggesting diversification in the natural landscape. Agriculture experienced slight expansion, particularly in temporary crops, which rose to 15 ha. Coffee (26 ha) remained nearly stable, reaffirming its local cultural and economic role. Silviculture (324 ha) showed growth compared to the previous decade. This period reveals a trend of reduced pressure from pasturelands and a strengthening of native vegetation and diversified agricultural uses.

- 2013 to 2023

In the last decade, the trend of forest recovery continued, with forest formations reaching 5718 ha. Pastures continued to decline (14,880 ha), albeit at a slower pace. Agriculture intensified significantly, with a notable increase in temporary crops (89 ha), indicating greater pressure on land for annual cultivation. Grassland formations decreased (18 ha), and savannas dropped back to 5 ha, signaling shifts in the balance of open vegetation types. Coffee (30 ha) saw a slight increase, maintaining its historical relevance. Silviculture (297 ha) stabilized, consolidating itself as a permanent land use. This period highlights a transition from a pasture-dominated territory toward a more balanced landscape encompassing forest regeneration, agricultural crops, and silviculture.

Land Use in Quilombola Rural Communities

Although situated within the broader municipal context of rural predominance and small-scale production, the studied communities exhibit a distinctive productive profile: remarkable crop diversification and the absence of large-scale livestock or silviculture activities. Among the 16 households interviewed, none reported cattle raising or commercial silviculture, contrasting with more conventional regional production models.

The communities practice an agricultural system based on diverse plantings and the raising of small animals, with production oriented substantially toward subsistence and local markets. All families cultivate a common set of crops, including maize, coffee, beans, rice, vegetables, cassava, pumpkin, and other vegetables and greens. Additionally, they raise pigs and chickens and maintain home gardens with medicinal plants used for teas.

This productive profile maintains a close relationship with the community’s food traditions, where cultivation is directly linked to local culture and culinary practices. In Moreiras Community, this connection is strengthened and made visible through the use of their own produce in the annual gastronomic festival—an event that has become a key practice for cultural valorization and adding value to local production.

A fundamental aspect of this model is its agroecological orientation. According to interviews, both communities emphasized the non-use of synthetic chemical inputs. As one resident from Buraco do Paiol explained: “Here we don’t use poison; we work with what the land provides and grow only what we need for our consumption” (Interviewee 5, Buraco do Paiol). In Moreiras Community, the same principle was reaffirmed: “We don’t use chemicals [pesticides]; everything here is natural” (Interviewee 7, Moreiras). These practices not only define the productive systems but also connect them to broader conceptions of health and environmental stewardship.

This deliberate exclusion of cattle ranching and commercial silviculture stands in sharp contrast to the dominant economic models observed at the municipal level (Section 6.2), where pasturelands and planted forests have historically been central to the rural economy. The absence of these activities is not indicative of economic stagnation, but rather reflects a conscious choice to pursue an alternative development pathway. The communities’ model of land use diversification is fundamentally different: it prioritizes internal agrobiodiversity and food sovereignty over integration into external commodity markets for meat or timber. This finding underscores that their economic resilience is built on cultural autonomy and agroecological principles, actively resisting the homogenizing pressures of regional agricultural intensification and redefining what “rural development” means within their territories.

6.3. Resources and Services

6.3.1. Educational Resources

The status of educational resources in the Buraco do Paiol and Moreiras communities will be examined through the evaluation of three fundamental dimensions: the geographic distribution of schools, population accessibility to these resources, and the availability of basic education at the elementary and secondary levels.

Based on the 2022 Demographic Census (IBGE), data regarding the quilombola population in the municipality of Rio Espera, totaling 292 individuals, reveal significant educational disparities. Of the total 241 quilombola individuals aged 15 years or older, 178 are literate, resulting in a literacy rate of 73.86% for this group. This percentage is slightly below the overall literacy rate of the municipality for the same age group, which stands at 87.69%, highlighting a specific deficit in access to formal education for this community.

Educational Resources in Buraco do Paiol Community

The precarious distribution of educational resources in the Buraco do Paiol community imposes severe accessibility barriers. The nearest school infrastructure, which concentrates primary, middle, and high school levels, is located in the center of Rio Espera, 6.5 km away (Figure 5). To reach it, students initially face a 3 km journey on foot, by bicycle, or by private means to the school bus pick-up point. This initial leg of the journey constitutes a critical logistical obstacle, whose human impact is highlighted through community testimonials.

Figure 5.

Location of the rural communities studied and their proximity to municipal schools.

As one interviewee recalled about their own experience: “It was very hard; we walked a lot, and we were just children. Sometimes when it rained, we arrived at school dirty and tired because the roads are not paved and there was an unsafe bridge to cross” (Interviewee 4, Buraco do Paiol Community). This testimony not only illustrates the physical toll of the journey but also highlights how poor road infrastructure exacerbates access to education, affecting dignity and readiness for learning.

- Educational Resources in Moreiras Community

The school distribution in the Moreiras quilombola rural community presents serious accessibility obstacles. Although the district of Ponte Alta, located 2.0 km away, offers a basic education school (covering early childhood education for children aged 0–5 years and the early years of primary education), complete educational infrastructure, including the later years of primary education (grades 6–9 for ages 11–14) and secondary education (ages 15–17), is exclusively located in the center of Rio Espera municipality, 8.7 km away. To reach these facilities, students must first travel to Ponte Alta on foot, by bicycle, or by car to access the school bus.

This initial displacement constitutes a significant logistical barrier, making the educational journey unfeasible for many young people, especially those with reduced mobility. The absence of middle and secondary schools within or near the community thus consolidates dependence on commuting to the municipal headquarters.

6.3.2. Health Resources

The distribution of medical resources between urban and rural areas is markedly unequal in Brazil. While the Southeast Region concentrates the majority of the country’s health resources—a reflection of its high urbanization rate (93%, IBGE, 2022)—this concentration primarily occurs in urban centers. Consequently, the gap between rural and urban contexts manifests in access to institutions, equipment, staff qualifications, and service quality. As shown in Table 2, the apparent quantitative advantage of the Southeast region masks significant internal disparities, where rural areas remain under-equipped.

Table 2.

Health Resources in Minas Gerais.

This inequality underscores the challenges faced by rural communities like Buraco do Paiol and Moreiras in accessing adequate healthcare services, further emphasizing the need for targeted policies to address these gaps.

Significant regional disparities are evident even within the Southeast region itself. While state capitals such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Belo Horizonte concentrate the most abundant medical resources, predominantly rural municipalities—especially those with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants—face a relative scarcity of these inputs. Thus, the region’s overall adequate level of resources masks localized shortages in its interior, perpetuating inequalities in healthcare access.

6.3.3. Specific Performance of Healthcare Resources in the Two Quilombola Rural Communities

Access to healthcare services for the populations of the two communities is centered in the municipality of Rio Espera and is marked by significant limitations, reflecting a scenario of regional inequality. The municipality faces a critical shortage of medical professionals, with a density of 0.74 physicians per 1000 inhabitants—a figure substantially below the 3.5 per 1000 benchmark established by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This places Rio Espera among the 44% of municipalities in Minas Gerais that have fewer than one physician per 1000 residents, while only 8% of the state meets the international target.

However, fieldwork conducted for this study identified a discrepancy in official records. Despite DataSUS registration (updated as of April 2025) indicating a ratio of 0.74 physicians per 1000 inhabitants, three active physicians were confirmed in the municipality: two working at the Basic Health Unit (UBS)—responsible for Primary Health Care, including routine consultations, prenatal care, vaccinations, and low-complexity services—and one at a small hospital focused on medium-complexity care. This inconsistency highlights that the fragility of the healthcare system extends beyond mere resource scarcity to include deficiencies in monitoring and updating the data underpinning public policies.

The lack of specialized infrastructure imposes a heavy logistical burden on the population. For high-complexity care—such as oncology, cardiac and neurological surgeries, and advanced diagnostic imaging (MRI, CT scans)—patients must travel to the state capital, Belo Horizonte, located 161 km away. Meanwhile, medium-complexity services—including surgical centers and more advanced imaging exams—are referred to Conselheiro Lafaiete, a regional hub located 99 km from Rio Espera. Although this hierarchical referral system is technically aligned with Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS), in practice it entails exhausting and costly journeys for citizens, thereby exacerbating health inequities.

6.4. Strategies for Territorial Strengthening and Sustainability in the Quilombola Communities of Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol

An analysis of the quilombola rural communities of Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol reveals that, despite structural limitations and a trend toward population decline, both communities have developed their own forms of territorial resistance and adaptation. These strategies integrate productive, cultural, and political dimensions, demonstrating ways of life that, while shaped by deficiencies in public policies, reaffirm the territory as a space of belonging and communal continuity.

In the case of the Buraco do Paiol Quilombola Community, the primary local concern is maintaining living conditions and ensuring residents’ permanence amid a context of population aging. To address these challenges, integration between public policies and community-led initiatives is essential. Strengthening family farming—already supported through programs such as the Food Acquisition Program (PAA) and the National School Feeding Program (PNAE)—should be expanded through complementary actions aimed at productive diversification and the promotion of agroecology. Measures such as ongoing technical assistance, access to rural credit tailored to quilombola realities, and the development of regional cooperative networks can help reverse economic dependency and foster local autonomy.

Furthermore, given the demographic aging, there is an urgent need to expand health and wellness services, with a focus on mobile primary care units and the training of local community health agents capable of integrating traditional knowledge with contemporary care practices. These actions, combined with improvements in road infrastructure, would not only enhance care for the elderly population but also support youth retention, as inadequate access conditions are one of the main reasons young people migrate.

In contrast, sustainability strategies in the Moreiras Quilombola Community are strongly linked to the cultural and symbolic dimensions of the territory. Religious festivals, the congado music band, and annual gastronomic events are practices that transcend mere festivity, serving as mechanisms of identity-based resistance and solidarity network strengthening. The active role of youth in promoting and organizing these activities—particularly through digital media—reflects a generational renewal of belonging and demonstrates how culture can become an instrument of territorial governance.

In this context, community-based tourism and cultural economies emerge as viable pathways for endogenous development, provided they are guided by sustainability ethics and community-led control. Public policies supporting community tourism, solidarity economy, and the valorization of intangible heritage can create real income-generating opportunities while respecting environmental limits and collective land-use logic.

Thus, in both Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol, prospects for territorial strengthening depend on the articulation between structural policies and local self-management practices. Sustainable rural development in these communities relies less on the mere replication of external models and more on recognizing the unique forms of quilombola organization—rooted in reciprocity, ancestry, and belonging. Valuing these dimensions is essential for designing territorialized public policies capable of advancing social justice, productive autonomy, and cultural continuity in quilombola territories.

7. Discussion

The contrasting trajectories of the quilombola communities of Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol reveal a distinct form of rural transformation—one rooted not in economic modernization, but in the reaffirmation of cultural and territorial identity as a strategy for resilience. While both communities face the structural vulnerabilities common to Brazil’s rural peripheries, their divergent paths highlight how local agency, manifested through cultural practices and agroecological stewardship, interacts with public policy to produce radically different outcomes. This section argues that the transformation in Moreiras is a process of active resistance and reconstitution, where community initiatives are not merely adapting to external pressures but are actively reshaping their relationship with the state and the market. In contrast, Buraco do Paiol’s stagnation reflects a state of territorial exclusion, where the absence of supportive governance reproduces historical marginalization. By framing these dynamics through the lens of territoriality and co-creation, this study offers critical insights into the conditions under which rural communities can assert autonomy and redefine development on their own terms.

7.1. Resilience Forged in Culture and Agency

The challenges faced by Buraco do Paiol—labor outmigration, aging populations, and environmental degradation—are not unique but reflect patterns observed across peripheral rural regions in Latin America. Similar processes of rural hollowing-out have been documented in indigenous and Afro-descendant communities in Colombia and Guatemala where outmigration erodes social cohesion and weakens collective land stewardship. In Brazil, data confirm a national trend of rural population decline, particularly in the Southeast, yet this study reveals how such macro-level trends manifest unevenly at the municipal level. Buraco do Paiol’s stagnation contrasts sharply with Moreiras’ revitalization, suggesting that structural forces alone cannot explain community outcomes; local capacity, leadership, and access to resources play decisive mediating roles.

This divergence echoes findings from who argue that quilombola communities with stronger associative networks and external alliances are better positioned to leverage public policies and attract investment. Moreiras’ success in developing community-based tourism and accessing school feeding programs aligns with studies showing that cultural capital and heritage recognition can serve as catalysts for socioeconomic development [41]. The persistence and revitalization of festivals such as Congado not only reinforce identity but also generate income and foster intergenerational transmission of knowledge—a dynamic also observed in Maranhão’s quilombos.

7.2. Territoriality: A Site of Resistance and Reconstitution

The concept of territoriality proves essential for interpreting these dynamics. As emphasizes, territory is not merely a geographic container but a lived space shaped by memory, struggle, and collective action. Our findings reveal a fundamental tension between two contrasting development models: the dominant agribusiness model, which prioritizes large-scale, capital-intensive production and land commodification, and the community-based agroecological model, which emphasizes food sovereignty, environmental stewardship, and collective land use. In Moreiras, territorial practices—such as cooperative farming, forest conservation, and cultural events—are actively reconstituted through engagement with state programs. This supports notion of “autonomous development,” where marginalized communities reinterpret and redirect top-down interventions to serve endogenous goals. The agroecological practices observed in Moreiras—characterized by polyculture, the absence of synthetic inputs, and integration with cultural traditions—stand as a direct counter-model to the expansion of silviculture and pasture observed at the municipal level (Section 6.2), which are often linked to the agribusiness paradigm. This active reconstitution of policy is thus not merely an adaptation, but a form of resistance against the homogenizing pressures of industrial agriculture. This proactive reconfiguration of policy stands in stark contrast to the more common trajectory in Brazil’s rural peripheries, where demographic decline and economic precarity often lead to passive acceptance of welfare dependence or outright abandonment of the territory.

In contrast, Buraco do Paiol’s limited integration into policy networks suggests a form of territorial exclusion, where bureaucratic barriers, lack of technical assistance, and infrastructural neglect reproduce historical inequalities. This resonates with Santos’ (2019) analysis of how rural Black communities in Minas Gerais are often rendered invisible in policy design, despite legal recognition under. Our field data indicate that even when policies exist, implementation gaps—such as delayed land titling or inadequate ATER coverage—undermine their transformative potential. While Buraco do Paiol faces severe structural constraints, the very fact that community members continue to assert their territorial rights and demand inclusion—despite the lack of support—highlights a form of persistent resistance that differs from the silent disengagement often seen in non-traditional rural areas under similar pressures.

7.3. Co-Creation: Bridging Policy and Community Practice

Our findings challenge the dichotomy between state intervention and community autonomy. Instead, they support a dialectical model in which policies and local practices co-constitute one another. The effectiveness of programs like PAA and PNAE depends not only on funding and design but on how they are appropriated by local actors. In Moreiras, farmers’ associations strategically use these programs to stabilize markets and promote agroecological production, mirroring successes in Bahia’s assentamentos. Conversely, in Buraco do Paiol, the absence of such intermediaries limits policy uptake, reinforcing cycles of disengagement.

This highlights the critical role of intermediary institutions—cooperatives, NGOs, and technical extension agents—in bridging policy and practice. As Ribot (2014) argues, decentralization without democratization of access leads to elite capture or abandonment. Our case shows that equitable outcomes emerge when policies are coupled with participatory governance mechanisms that empower communities to define priorities. However, the very existence of PAA and PNAE as differentiated policies designed to support family farming and traditional communities (as discussed in Section 4.2.3) does not guarantee their effectiveness in practice. The case of Buraco do Paiol reveals a critical gap: while these policies recognize the existence of quilombola communities, their implementation often fails to address the specificity of their identity and needs. The lack of adequate ATER (Technical Assistance and Rural Extension) tailored to communal land tenure and agroecological practices, and the bureaucratic hurdles in land titling mentioned in Section 5.2, demonstrate how a state apparatus still influenced by the logic of the agro-export model (Section 4.4) can undermine even well-intentioned differentiated policies. Thus, the effectiveness of these policies is contingent not just on community agency, but on the state’s genuine commitment to recognizing and supporting the heterogeneity of quilombola territories.

7.4. Beyond Romanticism: The Structural Foundations of Community Agency

Finally, this study affirms the value of a local and community-based perspective in understanding rural change. Identical policy instruments produce divergent outcomes depending on local histories, social capital, and ecological conditions. This aligns with recent calls for place-based approaches in rural development, which reject one-size-fits-all solutions in favor of context-sensitive strategies.

However, our research also cautions against romanticizing community agency. Without structural support—including secure land tenure, infrastructure, and fair market access—local initiatives risk becoming symbolic rather than transformative. The modest scale of temporary crops and coffee cultivation in both communities reflects broader constraints on smallholder agriculture in a globalized economy.

7.5. Synthesizing the Transformation: From Inclusion to Co-Creation

In sum, the transformation observed in Moreiras is not a departure from quilombola identity, but its strategic reassertion in the contemporary era. The community’s success is built on the revitalization of cultural practices (e.g., the Congado festival) and agroecological farming, which serve as both a source of livelihood and a form of resistance against the homogenizing forces of agribusiness. This process is enabled by a shift in governance—from passive inclusion in state programs to the active co-creation of development pathways. Community associations and farmers’ groups in Moreiras act as crucial intermediaries, appropriating policies like PAA and PNAE to serve endogenous goals. In contrast, the lack of such agency and institutional support in Buraco do Paiol results in a trajectory of exclusion and decline. This comparative analysis thus reveals that rural transformation for quilombola communities is fundamentally a political and cultural process, contingent on the recognition of their heterogeneity and the empowerment of their autonomy.

7.6. Limitations and Future Research

This study focuses on two communities within a single municipality, limiting generalizability. Future research should expand to comparative regional analyses and incorporate quantitative indicators of well-being, food security, and ecosystem health. Longitudinal studies could further assess the sustainability of current development models.

In sum, the experiences of Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol illustrate that rural quilombola communities are not passive recipients of policy but active agents engaged in continuous negotiation with state and market forces. Their trajectories reveal that resilience is relational—forged through the interplay of historical rootedness, cultural continuity, and strategic engagement with institutions. To advance racial, environmental, and rural justice, public policy must move beyond inclusion to co-creation, ensuring that quilombola voices shape the very frameworks meant to serve them.

8. Conclusions

This study set out with three central objectives: (1) to analyze the socioeconomic and demographic transformations affecting the quilombola rural communities of Moreiras and Buraco do Paiol in Rio Espera, Minas Gerais; (2) to examine how national and local rural development policies intersect with community-based territorial practices; and (3) to identify pathways of resilience and sustainability grounded in local knowledge and collective action. Drawing on a mixed-methods approach—integrating census data, geoprocessing, and fieldwork—the research has fully achieved these objectives, offering a nuanced, empirically grounded understanding of the complex realities shaping these traditional territories.

The first objective was achieved through the integration of quantitative and qualitative data, which revealed a dual dynamic in the communities: on one hand, structural pressures—including population aging, youth outmigration, and limited access to infrastructure and public services—are undermining social reproduction, particularly in Buraco do Paiol. On the other hand, Moreiras demonstrates how community-led initiatives in agroecology, cultural revitalization, and cooperative economies can counteract these trends, confirming the importance of local agency in rural resilience.

The second objective—assessing the interface between public policies and local practices—was fulfilled by analyzing the implementation and appropriation of key programs such as the Food Acquisition Program (PAA), the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), and Technical Assistance and Rural Extension (ATER). The findings show that while policy frameworks exist to support rural development, their impact varies significantly depending on local capacity, institutional intermediation, and historical patterns of inclusion or exclusion. In Moreiras, active engagement with these programs has enabled transformative outcomes; in Buraco do Paiol, weak integration has limited their effectiveness. This demonstrates that policy success is not solely determined by design but by context-sensitive implementation and community agency.

The third objective—identifying pathways for sustainable and equitable rural development—was achieved by highlighting the resilience strategies employed by these communities, particularly in Moreiras. These include subsistence polyculture (maize, beans, cassava, coffee, and vegetables), small-scale livestock raising, and cultural practices such as the Congado festival—all conducted without chemical inputs and rooted in ancestral knowledge. This agroecological and culturally embedded model stands in contrast to the municipality’s dominant cattle ranching and commercial forestry sectors, offering an alternative vision of rural development centered on food sovereignty, environmental stewardship, and identity affirmation.

In sum, this study not only met its stated objectives but also contributes to broader debates on quilombola territoriality and rural policy in Brazil. It underscores that sustainable development in marginalized rural communities requires more than top-down interventions; it demands co-creation, secure land tenure, and institutional support that recognizes and amplifies local knowledge. Future research should continue monitoring the long-term impacts of evolving policy frameworks and explore innovative governance models that integrate environmental conservation, social justice, and community autonomy in the Zona da Mata region of Minas Gerais.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.N.S.; Methodology, J.M.N.S., L.Z. and A.L.L.d.F.; Software, J.M.N.S.; Validation, J.M.N.S.; Formal analysis, J.M.N.S. and A.L.L.d.F.; Investigation, J.M.N.S.; Resources, J.M.N.S. and S.E.R.; Data curation, J.M.N.S. and L.Z.; Writing—original draft, J.M.N.S. and L.Z.; Writing—review & editing, J.M.N.S., L.Z. and A.L.L.d.F.; Visualization, J.M.N.S., L.Z., A.L.L.d.F. and S.E.R.; Supervision, J.M.N.S., L.Z., A.L.L.d.F. and S.E.R.; Project administration, J.M.N.S., L.Z. and S.E.R.; Funding acquisition, J.M.N.S., L.Z. and S.E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABC | Plano Agricultura de Baixo Carbono (Low-Carbon Agriculture Plan) |

| ATER | Assistência Técnica e Extensão Rural (Technical Assistance and Rural Extension) |

| CONAQ | Coordenação Nacional de Articulação das Comunidades Quilombolas (National Coordination for the Articulation of Quilombola Communities) |

| CONTAG | Confederação Nacional dos Trabalhadores na Agricultura (National Confederation of Agricultural Workers) |

| FUNRURAL | Fundo de Assistência ao Trabalhador Rural (Rural Worker Assistance Fund) |

| IBGE | Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) |

| IDR | Índice de Desenvolvimento Rural (Rural Development Index) |