Abstract

This paper reviews the impact of various types of AI education on the sustainability attitudes of Generation Z in Istanbul in the context of the new model of Hospitality 5.0. The study concentrates on three major aspects of learning related to AI, namely knowledge, practical implementation, and value-based orientation, and their interim impact on shaping sustainability-oriented perceptions of young people. The study established the reliability and stability of the constructs using psychometric testing, and factor analysis and structural modeling proved that every educational dimension of AI is positively related to sustainability attitudes. Of them, knowledge utilization proved to be the most powerful predictor. Further residual results revealed behavioral anomalies by demonstrating that those who outperformed were people with moderate technical abilities and high sustainability values and those who underperformed possessed high digital abilities without integrity value-based alignment. These results demonstrate that formal AI education is a stabilizing force, which encourages more consistent and sustainability-focused attitudes. Altogether, the findings point to the significance of educational models combining technical skills with ethical and environmental consciousness in helping Generation Z to find a middle ground in terms of sustainable change in the digital hospitality industry.

1. Introduction

The contemporary development of tourism and hospitality cannot be fully appreciated irrespective of the rapid digital evolution and the growing integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into operational and strategic business functions. The use of AI technologies within hospitality has passed the technical optimization stage, and now it is increasingly viewed from the potential contribution that they can provide in facilitating sustainability, personalized service, and strategic resource management [1]. Still, despite the rapid growth of technology, education systems that prepare future specialists for the industry typically do not effectively manage the complex issues arising at the intersection point of digital literacy and value orientation towards sustainable development [2,3]. Although the integration of AI within tourism and hospitality has been studied widely, past studies have mostly emphasized technological or management levels, with the psychological, pedagogical, and value-based levels being under-researched. In addition, there is limited empirical evidence of the impact of AI education on sustainability attitudes. This paper aims to fill this gap and thus make a contribution to the theory of sustainable digital hospitality by incorporating educational, cognitive, and ethical aspects in the framework of Hospitality 5.0. Previous research has primarily focused on the technological and operational aspect of AI adoption, whereas the psychological, pedagogical, and value-related dimensions of youth users and workers, particularly from Generation Z, have been largely untouched [4,5,6]. As a generation that is simultaneously creating the market as consumers and entering professional lives in the sector, Generation Z raises new questions about how digital technologies are understood, valued, and utilized within the context of sustainable business practice [7]. This imbalance between technical training and value-preparation has been referred to as one of the core gaps in research according to recent literature reviews [8,9]. This gap in research suggests that it is necessary to empirically research the ways in which educational systems, especially those related to the hospitality and tourism industry, can combine digital literacy with sustainability-oriented values with the help of AI-based learning, considering the immanent complexity of the urban context as a domain of digital transformation.

The objective of this study is to analyze how different forms of AI education (formal, informal, or absence of education) influence the formation of sustainability attitudes among Generation Z members in Istanbul, within the contemporary Hospitality 5.0 framework. The concept of Hospitality 5.0 originates from the broader Industry 5.0 framework, which emphasizes human–machine collaboration, ethical innovation, and sustainable production systems [10]. Unlike Industry 4.0, which focuses primarily on automation and efficiency, Industry 5.0 and its hospitality extension highlight human-centered digitalization, social well-being, and environmental responsibility. In this sense, Hospitality 5.0 integrates advanced technologies such as AI, IoT, and robotics with value-based management and sustainability-oriented education. However, this concept is still emerging in academic discourse and lacks consistent theoretical grounding, which makes its empirical operationalization both challenging and innovative [11]. Istanbul is an ideal city for research into these topics. As a regional tourism and educational hub, the city combines intensive digitalization of hospitality services with cultural continuity and institutional challenges of sustainable development [12,13]. In this respect, the study in Istanbul supplies not only a local but also a more universal model for the explanation of how AI education is related to the attitude toward sustainability among young people in transitional and dynamic environments. In this study, AI education is conceptualized through three complementary dimensions: formal (university courses and accredited programs), informal (workshops, online courses, and self-learning), and experiential learning derived from real-world interaction with intelligent systems. This distinction allows for a more nuanced understanding of how different modes of education influence the sustainability-related value formation of Generation Z. Special emphasis is placed on identifying behavioral patterns that deviate from theoretical predictions, including an analysis of so-called overperformers and underperformers. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of how AI-focused educational content shapes sustainable attitudes among young individuals in a highly digitalized, yet culturally multilayered, urban environment. Istanbul thus serves as a representative example of an urban setting where the intensive digital transformation of the hospitality sector intersects with institutional developments in AI education and the continuity of traditional value norms. Such a complex configuration enables a nuanced examination of the relationship between technical education and socially responsible behavior within a real socio-cultural dynamic context. The research not only addresses specific local phenomena but also contributes to broader academic discussions on how Generation Z positions itself toward sustainable transformations in tourism and hospitality. The innovative contribution lies primarily in the theoretical advancement of the Hospitality 5.0 concept by integrating an educational dimension and value profiling of future professionals. Through the use of a multilayered methodological approach, combining the measurement of latent constructs, testing of a theoretical model, and additional residual analysis, the study enables not only reliable hypothesis testing but also the identification of discrepancies between educational inputs and value-based outputs. The introduction of the categories of “overperformers” and “underperformers” allows for a deeper understanding of the complex behavioral patterns within Generation Z, highlighting the importance of linking technical competence with normative development. In doing so, the research lays the groundwork for redefining educational frameworks in the hospitality sector toward the comprehensive integration of digital and sustainable competencies, in line with the demands of the 4.0 and 5.0 Industrial revolutions. Considering the multidimensional nature of AI education and its potential role in shaping sustainability attitudes, as well as the specificities of urban contexts where traditional values intersect with digital transformation, the study raises the question of how different forms of AI education influence young people’s value orientations within the hospitality sector. A particular challenge lies in understanding whether there is a consistent alignment between acquired knowledge, practical skills, and value-based acceptance of AI for sustainable development purposes. Due to the identified gap in the relationship between technical education and the values of sustainability in Generation Z, the aim of the study is to empirically explore how the various types of AI education influence the sustainability attitudes within the Hospitality 5.0 model in Istanbul. To operationalize the main research objective and to provide empirical guidance for the analysis, two supporting research questions were formulated:

R.Q.1. To what extent do different modes of AI education (formal, informal, and self-directed learning) shape the development of sustainability-oriented values and behavioral intentions among Generation Z within the Hospitality 5.0 framework?

R.Q.2. How do discrepancies between AI knowledge, practical application, and value orientation explain the emergence of “overperformers” and “underperformers” in adopting sustainable practices in smart hospitality contexts?

These research questions helped to structure the paper and create a methodological framework that gave a precise connection between the identified gap in the research and the empirical analysis of the effects of AI education and sustainability in the Hospitality 5.0 model. However, the present study does not directly focus on AI personalization through the lens of the consumer experience, but it is focused on the influence of AI-related education on the values of technological readiness and sustainability that subsequently become the determinants of how users interact with intelligent hospitality settings. The uniqueness of this work is the multidimensional aspect, and the relationship between AI education and sustainability attitudes is tested, but the behavioral types of the so-called overperformers and underperformers begin to emerge, which makes the theoretical concept of Hospitality 5.0 as a learning and value-based construct richer and more interesting.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Building Sustainable AI Competencies in Hospitality Education

Artificial intelligence personalization (AI-based personalization) refers to utilizing artificial intelligence tools—machine learning, recommendation systems and predictive analytics—in a manner where services, content and interactions are adapted to specific users in real time [14]. In contrast to the general smart tourism technologies that are aimed at automatization and data connection, personalization gives emphasis on flexibility and personalization, which has a direct impact on user interaction, satisfaction and loyalty. AI personalization, on the one hand, can enhance the competitiveness and efficiency of business with an economic and managerial perspective [15]; on the other hand, it can cause problems such as transparency, privacy and bias of algorithms [16]. As an engineer, it entails the combination of big data and deep learning algorithms, which facilitate the study of user behavior and forecasting of needs in time [17]. By doing so, AI personalization provides a solution combining innovation and sustainable user experience in smart tourism ecosystems. Within modern-day literature, the AI personalization concept, smart destinations, and improved user experience have to be considered theoretically on a larger scale beyond technical descriptions. Yamagishi et al. [18] note that personalization based on artificial intelligence suggests a cognitive and ethical learning process in the digital space. According to Chand [19], it has managerial implications because it influences organizational structures and decision-making models, whereas [20] states that smart destinations are social-technological ecosystems in which user and community engagement are determined through personalization. Bosio et al. [3] introduce an engineering aspect, stating that the technical design of systems influences the efficiency and ethics of the use of the systems, and [21] states that education and value orientations are crucial to the understanding of the sustainable use of AI technologies. This conceptually places AI personalization as a component of the Hospitality 5.0 paradigm, which relates innovation and human values and sustainability.

The increasingly pronounced presence of artificial intelligence (AI) in tourism and hotel industry has opened up a new field of research that increasingly includes educational aspects of preparing future experts. Ivanov and Webster [15] set one of the first conceptual frameworks for understanding the application of robotics, AI and automation in the tourism and hospitality sector, but their analysis remains on operational and managerial dimensions, without a deeper consideration of the impact of technologies on educational models and attitudes of the future workforce. Bilotta et al. [22] extend this approach by analyzing how Industry 4.0 technologies shape educational processes in tourism. Their emphasis on students’ ability to “think through technology” represents an important theoretical contribution to the development of digital and AI literacy, but without including the value dimension of sustainability. Neumann et al. [23] make a contribution to the study of institutional barriers in the implementation of AI and the role of organizational culture and trust in technology in this regard, both of which are also applicable to educational institutions to form ethically responsible and technologically competent generations. The bibliometric analysis conducted by Knani et al. [24] proves that education and human capital in the sphere of AI and hospitality remain under-investigated. Likewise, Deborjeh et al. [25] mentions that the majority of publications do not focus on educational implication and knowledge and attitude development of the future employees. Jabeen et al. [26] discuss the alterations to work processes that took place due to automation, but fail to provide a more in-depth perspective on the consequences for education or educational system readiness. Technologically speaking, Essien and Chukwukelu [27] create a framework of the deep learning application in tourism, though they disregard the educational and value background. The shift in attitude is facilitated by the article of Orea-Giner et al. [28], which in the context of Industry 5.0 suggests that it is necessary to combine humanistic and technological values that would allow exploring the possibility of how education influences the formation of value-oriented professionals. The Hospitality 5.0 idea proposed by Hussain et al. [29] is oriented towards educating job seekers on employability and sustainability in their careers, with a focus on digital, ethical, and sustainable skills linkage. The concept of Tourism 5.0 by Vujičić, et al. [30] is further elaborated to discuss inclusivity and accessibility, which has instant implications to education because it focuses on the relationship between the social and technological aspects of teaching. These findings suggest that while AI education improves digital competence, it does not necessarily translate into sustainability-oriented attitudes without the inclusion of ethical and value-based content.

H1.

Self-assessed knowledge of artificial intelligence has a positive and statistically significant impact on the formation of sustainability-oriented attitudes among Generation Z members in Istanbul.

Talukder et al. [31] also justify the significance of Industry 5.0 by stating that the shift towards a digital society should entail education, which should involve not only the transfer of technical knowledge but also a critical reflection on the social and ethical implications of technological innovation. Dogru et al. [32] claim that theoretical frameworks that combine education and digital literacy have to be created, whereas Kim et al. [9] note that there is a disconnect between academic literature and industry, and educational systems must be lagging behind technological advancement and modernize their curriculum. Saleh [33] examines the application of generative AI to the functioning of hotels and identifies the barriers to the educational process in the realization of the context and restrictions of the technology, whereas Tuo et al. [34] demand the introduction of ethical and environmental aspects to the educational process. Lastly, He and Zhang [35] empirically verify that experiential learning on AI does not only enhance technical skills among students, but also enhances the growth of a professional attitude that is sustainable and socially responsible, which is what the Hospitality 5.0 paradigm is all about [36].

The analyzed literature proves the existence of trends indicating the growing significance of AI literacy in hospitality education but demonstrates a gap in understanding how the specified education can be converted into value-based or sustainability-oriented practices. In the majority of the articles, descriptive rather than normative studies are conducted, and they explore the concept of digital competence but not the normative aspect of learning.

2.2. Gen Z as a Driver of Sustainable Changes in the Digital Hotel Industry

In the digitally transformed hotel sector, generation Z is becoming an increasingly important actor in shaping sustainable practices, both through consumer habits and through an increasing role in the workforce. Early literature reviews on the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in tourism and hospitality emphasized accelerated technological integration, but often neglected the role of young users and employees in the process. Knani et al. [24] point to the rise of interest in AI in the sector, but identify a lack of research that includes demographic characteristics, especially Generation Z. Essien and Chukwukelu [27] offer a methodological framework for deep learning research in tourism, but do not address how Generation Z, as the most digitally literate cohort, contributes to the sustainable digital transformation of the sector. Huang et al. [37] link AI and hotel management, staying at the organizational level and ignoring the changing value orientations of the younger generation. Saydam et al. [38], in their review of papers on AI in tourism, conclude that research remains focused on managerial and technological aspects, while the mediating role of Generation Z between sustainability and digital technology is underexplored. Such an approach, which ignores the subjective aspect of technology use, limits the development of comprehensive strategies that integrate social and environmental dimensions.

Newer research brings a fundamental turn by analyzing the expectations, attitudes and behavior of Generation Z in the context of sustainability and digitalization. Seyfi and Hall [39] emphasize that Generation Z sets new standards in the consumption of hotel services and the shaping of work ethics, insisting on transparency, responsibility and efficiency. In another paper, Seyfi et al. [40] critically question whether Generation Z can really be considered a “pro-SDG” generation. Although they note a high declarative support for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), the authors point to a gap between expressed values and actual behavior, especially in the context of tourism decisions. Popşa [41] analyzes the behavior patterns of young tourists, confirming their preference for digitally mediated services, environmentally responsible destinations and transparent communication, but also observes that the market offer often does not follow these requirements. Wu et al. [42], taking the example of the Chinese market, apply the extended Theory of Planned Behavior and confirm that behavioral control, subjective norms and previous education about sustainability significantly influence the choice of “green” hotels. Liu et al. [43] examine the impact of organizational climate on the development of “green creativity” among Generation Z employees and conclude that a supportive work environment fosters sustainability-oriented innovation. Ghouse et al. [44] compare generations Y and Z and confirm that generation Z shows a greater preference for sustainable options in consumption and professional aspirations, although there is still a gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. The latest research by Alam [45] confirms that young leaders from generation Z, especially in the hospitality industry of Bangladesh, possess a high level of digital competence and are increasingly initiating transformative processes towards sustainable business. The same author emphasizes that the digital literacy of Generation Z can be a key driver of change, but only if it is supported by adequate education, organizational culture and incentive systems. These studies indicate that practical application of AI and the development of advanced digital competencies can significantly enhance Generation Z’s orientation toward sustainability in hospitality contexts.

H2.

Practical application of artificial intelligence and advanced digital skills significantly contribute to positive attitudes toward sustainability in hospitality among Generation Z.

Although, according to previous studies, Generation Z is recognized to be digitally savvy and pro-sustainability, there is a lack of empirical evidence on whether such a generational group has been influenced to actually act in the desired way. This implies that there is a necessity of integrative models that encompass psychological and environmental aspects that influence sustainable interaction with the Gen Z in intelligent hospitality settings.

2.3. The Relationship Between AI Education and Attitudes Toward Sustainability in the Context of Smart Hospitality

The concept of artificial intelligence (AI) in the modern paradigm of managing a smart hotel is not perceived solely as a technological optimization tool, but also a tool directly or indirectly defining the sustainable behavior of employees and users. The relationship among AI education and attitudes to sustainability is growing in significance, and the existing literature covering this connection is still sparse and scattered. Biriescu et al. [13] discuss student perceptions of AI in the digital economy of the tourism sector and affirm that there are positive attitudes to using AI tools, but at the same time, the relationship between AI education and shaping socio-ecological values is not clear. The authors find that the educational content is still technically oriented, and there is no incorporation of sustainability principles, this way it is hard to come up with a value-driven professional identity. Khan and Khan [46] consider motivation to utilize smart hotel services by tourists and conclude that technological preparedness is the factor of strong motivation, and the secondary criterion is sustainability. It validates that in the absence of organized training concerning the environmentally and socially friendly role of smart technologies, users do not often associate digital innovations with environmental and social rewards. Jerez-Jerez [47] proposes a research change, switching the emphasis to the employees in independent hotels, and demonstrates that a positive understanding of AI tools stimulates employee involvement in the process of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), yet only under the condition that the education correlates the technology with the sustainability and non-financial aspects of the hotel performance.

Thongmun et al. [48] provide an analysis of the experience of guests in smart hotels and reveals that even the use of energy sensors as systems can promote the more reasonable use of resources, only with the help of the educational guidance. Hence, technical infrastructure that lacks an educational aspect is incomplete. Gu and Shakarliyeva [49] point out that digital transformation will not sustainability without a strategy to incorporate the education of both users and employees and the management. Hossain et al. [50] check that the combination of AI and sustainability may be effective in green human resource management models where education along with positive organizational environment complement the dedication to sustainable objectives. El-Akhras et al. [51] also emphasize the dangers of the educational use of AI-based applications, such as ChatGPT-4 Turbo, and point to the development of superficial knowledge and the inability to critically approach the matter among students, which should be complemented with the educational process based on digital literacy and value reflections. These findings collectively suggest that the formation of sustainability-oriented behavior depends not only on technical AI literacy but also on the development of value-based understanding of technology’s social and ethical implications.

H3.

A positive value-based attitude toward the role of artificial intelligence in tourism positively influences support for sustainable practices in the hospitality sector.

Istanbul is becoming a more and more important strategic destination, which is embracing the dynamic digital transformation with diverse cultural resources [52]. Being an educational and tourism hub, the city has already implemented smart technologies in hotel work (AI-service personalization, resource management), but the systemic aspect of the sustainability education into professional training is not introduced [53]. According to the research by Top and Kaya [54] and Tarakçı and Olcay [55] students express a positive attitude toward AI, but a poor relationship between technological competence and environmental responsibility, and sustainable factors of digital transformation are often not taken into account as strategies [13]. The role of technology in relation to space and social responsibility becomes even less certain owing to urban changes like gentrification and the proliferation of digital platforms [12,56].

Even though Istanbul has a huge potential of sustainable and smart transition, the use of AI in the hotel sector is still discontinuous and inadequately backed by the educational and institutional programs [57]. Therefore, the city is a sort of laboratory where the problems and opportunities of sustainable digital transformation interact, and this is why it is the best place to study the attitudes and behavior of the generation Z that will be the determinants of smart and sustainable hotel management in the future [58]. Using a theoretical framework of interconnection between digital literacy and value orientations and sustainable management as the concept of Hospitality 5.0, this study investigates how various elements of AI education are interconnected and attitude towards sustainability [59]. The materials provide complementary yet defragmented information on the educational, technological and ethical aspects of the adoption of AI. Nevertheless, little research empirically connects those areas, and the intermediary effect of AI education on the formation of sustainability-oriented has not been studied yet, which is the gap that this research should fill.

The integration of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Value Belief Norm (VBN) theory in the research is based on the fact that they have complementary explanatory potential [60]. Although TAM describes the cognitive and behavioral processes that define the willingness of people to use technology, VBN offers understanding of the moral, social, and value-driven factors that promote sustainability-oriented behavior [61]. They collectively constitute an integrative structure that can connect technology literacy to ethical and environmental consciousness, which is especially topical in the case of AI education and the younger Generation Z [62]. Even though the changes in sustainability attitudes could have been explained by the other theoretical models, like the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), or Learning Motivation Theory, these theoretical models provide a weak explanatory power in the case of understanding the intersection of technology acceptance and value internalization. The TAM plus VBN approach is thus a more elaborate analytical platform on which one can consider how AI education may promote the instrumental adoption of technology as well as the establishment of sustainability-focused values within the new paradigm of Hospitality 5.0 [63]. Located at the crossroads of the educational psychology research, technology research, and sustainability science, the given work contributes to the development of the theoretical debate and leaves the sphere of mere descriptive statements regarding digital competence behind, providing a systematic and conceptually coherent insight into the possibility of developing a sustainable-minded approach among the future professionals of the hospitality industry with the help of AI education.

3. Methodological Framework and Statistical Analysis

3.1. Sampling Strategy and Research Procedure

The research was conducted on a sample of 823 members of Generation Z (aged 18–29), with the aim of examining the relationship between AI education and attitudes toward sustainability within the context of smart hospitality. Generation Z was selected as the focus of the study as it represents the first digitally highly literate cohort currently undergoing education and professional integration into the tourism and hospitality sector [64]. This target group is considered a potential driver of value-based changes, including shifts in attitudes toward the role of AI in sustainable hotel operations [65]. Participants were selected using a quota sampling method, ensuring representativeness by gender, age, and educational background. The survey included students and young employees from the following districts of Istanbul: Beşiktaş, Kadıköy, Şişli, Fatih, and Üsküdar, which represent key educational and tourism-hospitality centers in the city. Istanbul was chosen as a research environment because it represents the largest educational and tourism-hospitality hub in the country, with a high concentration of study programs in tourism, management and information technologies, as well as a developed hotel sector in which smart hotel management practices are present (e.g., AI-personalization of services and digital resource management). This combination of a broad student base, a diverse curricular environment (formal, informal and online AI education) and an intensive digital transformation of hotel operations enables the examination of the connection between AI education and sustainability attitudes in a real-world Hospitality 5.0 urban ecosystem. This ensures analytical representativeness for urban and transitional destinations with a similar educational-industrial profile.

Data were collected September 2025 using the Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) method via tablets. This method was chosen for its efficiency in gathering structured responses, as well as its ability to ensure immediate quality control of the collected data [66]. The survey was administered by previously trained field assistants, and participants were contacted at university campuses, coworking spaces, student residences, and hotels that agreed to participate in the study. The questionnaire consisted of closed-ended statements measured on a five-point Likert scale (1–5), organized into four thematic sections: understanding of AI concepts, practical skills and applications, trust and attitudes toward AI, and support for sustainable hotel practices. The questionnaire was previously validated through pilot testing on a sample of 50 respondents. According to G*Power (3.1.9.7 Version)calculations (parameters: effect size f2 = 0.15; α = 0.05; 1-β = 0.95; number of predictors = 3), the minimum required sample size was 119 respondents, confirming that the collected sample was methodologically adequate and statistically robust [67].

Since the data were collected through self-reported questionnaires, measures were taken to reduce the risk of social desirability bias. Respondents were assured of full anonymity and confidentiality, and the items were neutrally worded to avoid moral priming or socially desirable cues. The online format further minimized interviewer effects and encouraged honest responses. Participant anonymity was fully respected, and participation was voluntary. Prior to beginning the survey, respondents received an informed consent form explaining the research objectives, data protection measures, and their right to withdraw from the study without any consequences. The research team adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (revised 2013), Bierer [68] and to the core standards of academic ethics and participant protection, including obligations related to data confidentiality, avoidance of participant pressure, and careful management of potential ethical risks when addressing sensitive topics related to digital technologies and sustainability.

The analyzed sample reflects an approximately balanced gender distribution, with women accounting for 51.8% and men for 48.2%. The largest proportion of respondents falls within the 22–25 age group (38.5%), while the remaining two groups, 18–21 and 26–29 years old, are relatively evenly distributed at 32.2% and 29.3%, respectively. In terms of education, the dominant group consists of university students (64.7%), while 23.4% hold a completed higher education degree, and 11.9% have completed secondary education. The most represented field of study is tourism and hospitality (32.1%), followed by IT/computer sciences (24.1%), economics/management (17.6%), and social sciences (13.2%). Regarding employment status, nearly half of the respondents are currently unemployed (47.0%), while 34.4% are engaged in part-time work and 18.6% are employed full-time. More than half of the respondents (52.5%) have no practical experience in the hospitality sector, whereas 31.1% have participated in internships or training programs, and 16.4% are already working within the tourism sector. In terms of AI education, 33.9% of respondents have attended formal courses, 37.9% have received informal education (e.g., online courses), while 28.2% have no educational background in this area (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive profile of the sample.

Quota sampling was used in this research to ensure minimal stratified coverage of key demographic and educational variables relevant to testing the research hypotheses. Quotas are set by gender, Gen Z age cohorts, and educational major, with particular emphasis on the difference between tourism and management students and those studying information technology or other related fields, including respondents with no formal AI education. This approach enables the comparability of sub-samples in relation to knowledge, practical skills and value orientations towards sustainability, thus avoiding systematic biases that could arise from disproportionate sampling. In addition, the quota approach ensures better coverage of the population, since student populations in urban areas, such as Istanbul, show an uneven distribution in terms of gender, major and educational status. The quotas are defined according to the current proportions of enrollment at the partner faculties in the field of tourism, management and information technologies, and filling was carried out using the convenient sampling method within each quota, until the planned sample size was reached. This method has proven to be adequate in research where the goal is to test the relationship between constructs (CFA/SEM) and compare subgroups, in situations where complete randomization is not logistically feasible. Additionally, gender, age, and educational background were controlled in the analytical models to reduce potential biases and increase the reliability of the results. Although the quota sampling method ensured demographic and educational representativeness across gender, age, and study fields, it is not fully random. Therefore, certain bias in the distribution of responses may exist, particularly related to accessibility of participants and institutional affiliation. However, the use of quotas minimized major deviations and ensured comparability across subgroups relevant to the study’s hypotheses.

3.2. Measurements

The instrument developed for this study was created to check Gen Z’s competencies, attitudes and perceptions toward artificial intelligence (AI) and sustainability within the context of smart hospitality. The questionnaire was structured to encompass the key cognitive, operational, and value-based dimensions related to digital transformation and sustainable management in the tourism sector. Its development was grounded in the theoretical framework of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [69], supplemented by contemporary extensions and applications within tourism, including studies [15,16,70]. In addition, elements addressing support for sustainable practices were based on the Triple Bottom Line concept [71] and applied research in tourism sustainability [72,73]. The constructs were designed to examine respondents’ understanding of basic concepts related to artificial intelligence, their self-confidence in its practical application, their general attitudes toward its role in hospitality, and their willingness to accept AI as part of sustainable development strategies. In line with the TAM framework, the questionnaire covered dimensions such as perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and technology acceptance readiness. Furthermore, the STARA framework was used as the basis for assessing digital readiness and professional adaptability among young users [74]. The questionnaire also included items theoretically grounded in value-based behavioral models (Table 2), such as the VBN theory to capture the relationship between education and environmentally oriented attitudes [75]. Following the approach of [28,29], formal AI education was operationalized as participation in structured, accredited learning programs such as university courses, certified training modules, or officially recognized curricula that include AI-related content (e.g., machine learning, data analytics, or digital systems). Informal AI education referred to self-directed, non-accredited learning experiences, such as online courses, workshops, or personal experimentation with AI tools (e.g., Chat GPT-4 Turbo, hotel management software). Participants were classified based on self-reported engagement in at least one of these forms of learning within the past two years. This distinction allowed comparative analysis between institutionalized and self-initiated modes of AI knowledge acquisition.

Table 2.

Constructs and item descriptions.

Prior to the main study, a pilot test was conducted on a sample of 50 respondents from three districts in Istanbul (Beşiktaş, Kadıköy, and Şişli), enabling the assessment of the questionnaire’s clarity, duration, and conceptual consistency. Based on the feedback received, targeted adjustments were made, including terminological modifications to more precisely differentiate between the concepts of automation and AI systems, expansions of statements that were identified as unclear (by providing concrete examples of AI tools), as well as the removal of one item that demonstrated weak psychometric properties (factor loading < 0.50). Content validation of the instrument was carried out through a process of expert consultation with university professors specializing in digital tourism, sustainability, and hospitality education, thereby ensuring the theoretical and terminological clarity of the statements. All measurement items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”.

3.3. Approach to Data Processing

The data collected through the survey instrument were analyzed using a combination of software packages: IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27) for descriptive and preliminary analyses, and Mplus (version 8.9) for latent variable modeling and the estimation of structural relationships. The analytical approach consisted of three complementary phases: descriptive statistics and distribution checks, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA and CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM) with additional residual analysis.

In the first phase, the normality of data distribution, homogeneity of variances, and the presence of potential outliers were examined. All variables demonstrated satisfactory levels of skewness (<1) and kurtosis (<1), confirming their suitability for the application of multivariate techniques [78]. To validate the constructs used in the questionnaire, the sample was divided into two parts: one part was used for conducting the EFA and the other for CFA. Of the total 823 participants, 300 were randomly selected for the EFA, ensuring stability in the identification of latent structures during the initial phase. The remaining 523 respondents were included in the CFA to test the validity of the factor structure.

The exploratory factor analysis was performed using Promax rotation and a factor loading threshold greater than 0.60. It is necessary to mention that the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in the study under consideration was not performed as a data reduction tool but as the means of diagnostics to assure the dimensional structure and the internal consistency of theoretically specified constructs. One of the purposes of the EFA was to validate item grouping before the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was undertaken and thus the EFA was not utilized to probe new or unknown aspects of the data. This design corresponds to the methodological guidelines of [79,80], who state that EFA can be used as a pre-methodological step when constructs are theoretically proved, but empirical validation is needed. Based on the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO = 0.913) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2(190) = 4583.217, p < 0.001), the data were confirmed to be appropriate for factor extraction [81]. The resulting four latent dimensions cumulatively explained 91.64% of the total variance, with individual contributions as follows: AI_Knowledge (61.3%), AI_Application (17.2%), AI_Attitudes (13.1%), and Sustainability_Views (8.3%). The CFA indicated excellent model fit according to the following indices: χ2(164) = 291.487, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 1.777, CFI = 0.963, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.047 (CI: 0.038–0.055), and SRMR = 0.041, consistent with standards from the literature [82]. All factors demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ≥ 0.785), composite reliability (CR ≥ 0.844), and convergent validity (AVE ≥ 0.581). In order to check the possibility of common method bias (CMB), Harman’s test of one-factor analysis was conducted. All measurement items were included in an unfactored exploratory factor analysis, and the first factor explained less than 40% of the total variance, indicating that CMB was not a significant problem in this study [83].

The structural model was tested using SEM in Mplus, where three latent predictors (AI_Knowledge, AI_Application, AI_Attitudes) were modeled in relation to the outcome variable (Sustainability_Views). All structural paths in the model were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Following the SEM modeling in Mplus, the predicted values for the latent outcome variable were exported and further processed using Python (3.14.0 Version)programming language. Utilizing the pandas, numpy, and sklearn libraries, residuals were calculated for each respondent. Based on the discrepancies between the actual and predicted values, cases were classified as overperformers, underperformers, or model-aligned, allowing for an individualized assessment of model fit.

4. Results

The descriptive and psychometric characteristics of the latent constructs indicate that all the factors were reliably measured and conceptually well-defined. The AI_Knowledge construct displayed a moderate to high average score (m = 3.81) and a satisfactory level of internal consistency (α = 0.785), with all items exhibiting factor loadings above the acceptable threshold of 0.60. The highest loading was recorded for the statement “I have received basic education about AI” (λ = 0.864), suggesting that formal education in artificial intelligence is central to the perception of AI knowledge. The AI_Application construct demonstrated a higher average score (m = 3.98) and greater internal reliability (α = 0.817), with the highest factor loading associated with the statement “I know how AI supports sustainable inventory management” (λ = 0.883), indicating respondents’ clear understanding of the operational benefits of AI. The AI_Attitudes construct, which measures general beliefs and acceptance of AI in tourism, achieved high internal reliability (α = 0.865) and a solid structural coherence, with the highest loading attributed to statements expressing positive attitudes and trust in AI’s ecological function, particularly the statement “I have a positive attitude toward the use of AI in tourism” (λ = 0.848). Finally, Sustainability_Views, as the outcome variable, demonstrated the highest reliability among all constructs (α = 0.901), indicating clearly formed respondent attitudes regarding the role of AI in enhancing sustainability within the hotel industry. The statement “Sustainability in hotel operations is important for environmental preservation” showed the strongest factor loading (λ = 0.891), confirming a strong ecological orientation among Generation Z respondents. All factor loadings exceeded the recommended threshold (λ > 0.60), confirming the convergent validity of the constructs. These results demonstrate the strong theoretical and empirical grounding of the measurement scales used in this study (Table 3).

Table 3.

Item-level metrics and measurement validity across constructs.

The descriptive and psychometric characteristics of the latent constructs indicate a high level of reliability and validity within the measurement model. All constructs achieved satisfactory mean values (m ranging from 3.80 to 4.18), suggesting a generally positive orientation among respondents toward the concepts of artificial intelligence and sustainability in the hospitality context. Standard deviations reflect an expected degree of variability in responses, with the greatest dispersion observed for the AI_Application factor. The internal consistency of the measurement scales, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70 across all constructs, with Sustainability_Views demonstrating the highest reliability (α = 0.901) and AI_Knowledge the lowest, though still acceptable (α = 0.785).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was not conducted to identify new variables, but to check the dimensionality and internal consistency of items taken from earlier research. This analysis was applied as a preliminary step to check whether the observed variables are correctly grouped into the theoretically expected factors, before conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural modeling. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) revealed that each construct has its distinct factor structure with a corresponding latent component, with all eigenvalues greater than 1. The construct AI_Knowledge accounted for the largest proportion of explained variance (61.3%), while collectively, the four constructs explained 100% of the variance, an outcome aligned with the constrained four-factor solution applied during the rotated factor analysis. Composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) further confirmed the constructs’ stability and convergent validity. All CR values exceeded 0.84, and all AVE values surpassed the minimum criterion of 0.50, thus satisfying the conditions required for confirming the measurement model within the SEM analysis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of construct-level psychometric properties and explained variance.

Even when cumulative variance attained 100, this outcome does not represent the ideal elucidation potential of the model, but instead, it represents the statistical sealing of the factor extraction process. All four extracted components add up to the total variance in the rotated solution since each of them reflects a section of the explained structure [79]. To avoid overfitting, only the factors with a high eigenvalue (more than 1) were kept, and loadings that were less than 0.50 were not interpreted. This model has also been confirmed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) which established the discriminant-validity as well as internal consistency of the constructs. The given interpretation can be justified by the recommendations of [79,80], which point out that the total values of variance in the PCA indicate the overall sum of extracted orthogonal components and not the hypothetical perfection of the model.

Additionally, variance inflation factor (VIF), skewness, and kurtosis values were calculated to test the assumptions of multicollinearity and univariate normality. All VIF values were below the threshold of 5, indicating no multicollinearity among variables. Skewness and kurtosis values were within the recommended ranges (−2 to +2 and −7 to +7, respectively), confirming the normal distribution of the data and supporting the adequacy of the measurement model.

The results of the correlation matrix indicate that all latent constructs are positively interrelated, confirming the existence of theoretical associations between knowledge of artificial intelligence, its practical application, attitudes toward AI, and attitudes toward sustainability in hospitality. The strongest correlation was observed between attitudes toward AI and attitudes toward sustainable practices, suggesting that a positive perception of the role of AI technologies directly contributes to a higher level of support for sustainable hotel practices. Significant correlations were also found between AI knowledge and AI application, as well as between AI application and sustainability, indicating that a higher level of digital skills and practical competencies fosters the development of value-oriented attitudes in the context of sustainability (Table 5).

Table 5.

Inter-construct correlations.

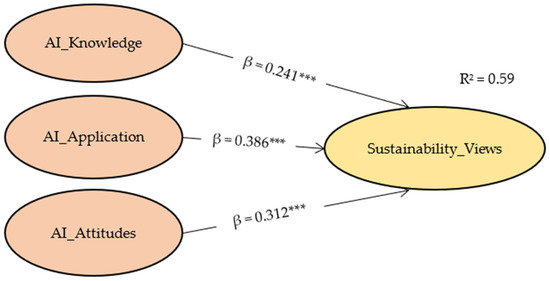

After confirming the adequacy of the measurement model, the hypothesized structural relationships were tested through SEM. The overall fit indices of the structural model confirmed an excellent model–data fit: χ2(167) = 295.203, χ2/df = 1.767, CFI = 0.962, IFI = 0.963, GFI = 0.940, AGFI = 0.918, SRMR = 0.046, and RMSEA = 0.045 (90% CI: 0.037–0.052). These results meet the recommended thresholds for good model fit (CFI, IFI, GFI ≥ 0.90; RMSEA ≤ 0.08; SRMR ≤ 0.08), confirming the validity of the proposed structural relationships [79]. The results of the structural model testing indicate that all proposed relationships between the constructs demonstrate statistically significant effects, confirming the research hypotheses. Although the initial hypothesis H1 predicted that self-assessed knowledge of artificial intelligence would not have a significant impact on attitudes toward sustainable practices, the obtained results clearly suggest otherwise. A positive and statistically significant relationship (β = 0.241, p < 0.001, Z = 4.085) indicates that, even at a basic level, the cognitive component of understanding AI contributes to shaping support for sustainability among members of Generation Z. The significant Z-value further suggests that the effect is stable and that the probability of the result occurring by chance is practically nonexistent, thus leading to the rejection of hypothesis H1 and acceptance of the opposite claim.

Furthermore, the findings related to hypothesis H2 reveal that the practical application of artificial intelligence and the development of digital skills exert the strongest influence on attitudes toward sustainability (β = 0.386, p < 0.001, Z = 5.761). This result, accompanied by a very high Z-value, confirms that direct experience with AI tools significantly contributes to the development of value-oriented attitudes. It appears that practical application, as opposed to merely theoretical knowledge, enables young professionals to recognize the concrete advantages that AI offers in the context of energy efficiency, waste reduction, and the enhancement of sustainable business strategies. The results for hypothesis H3 further confirm that a positive value-based attitude toward the role of artificial intelligence in tourism has a significant positive effect on support for sustainable practices (β = 0.312, p < 0.001, Z = 4.875). The high Z-value here again indicates strong statistical confirmation that young people’s value orientations toward technology are critical in shaping their attitudes toward sustainability. The formation of positive value-based beliefs about AI not only facilitates technology acceptance but also directly contributes to the development of sustainable business behaviors (Table 6).

Table 6.

SEM path analysis results.

The findings of the structural model are presented in Figure 1, which demonstrates the standardized path coefficients between the latent constructs and the level of significance. All the relationships in the model were found to be significant (p < 0.001) which proves the established hypotheses and demonstrates the stability of the theoretical framework in the concept of Hospitality 5.0. Specifically, the greater impact of the artificial intelligence application (AI_Application) and attitude towards AI (AI_Attitudes) on sustainable values as opposed to the self-perceived knowledge about AI (AI_Knowledge) is emphasized. The standardized path coefficients are statistically strong; however, the interpretation of the results in practical terms has a more profound meaning. The fact that AI knowledge and sustainability perspectives are positively related (r = 0.241, p = 0.001) indicates that a theoretical knowledge of AI tools impacts positively on the awareness of the environmental and ethical concerns in hotels. In a similar manner, the correlation between AI application and sustainability (p = 0.001, r = 0.386) shows that practice-level of AI technology application, including energy management or optimization of digital services, is connected to visible pro-sustainability behavior in students and young professionals. The correlation between AI attitudes and sustainability (r = 0.312, p = 0.001) also demonstrates that value orientations towards AI are motivational and supports sustainability oriented engagement instead of technical competence. Therefore, the statistical associations provide a practical understanding of how the interaction of AI education elements contributes to the development of sustainable mindsets among Generation Z in hospitality education and practice. The structural model explained 59% of the variance in Sustainability Views (R2 = 0.59), indicating moderate explanatory power according to Hair et al. [79].

Figure 1.

Structural model results. *** p < 0.001.

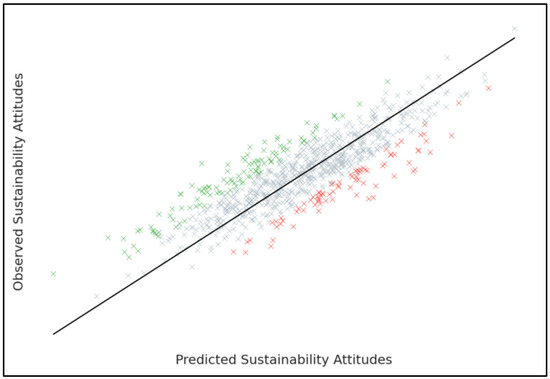

To further deepen the understanding of the predictive efficiency of the structural model, the predicted values of the latent outcome variable Sustainability_Views for each respondent were exported from Python software (3.14.0 version). Structural relationships were tested on Python with the sklearn library to perform residual analysis, to understand the strength of structural relationships, and to determine systematic deviations between observed and predicted values. This step, in addition to being characteristically technical, is theoretically advantageous to the model in the sense that it allows behavioral patterns that are not reflected in conventional SEM estimates to be identified. Specifically, the residual clustering made it possible to identify overperformers and underperformers, which gave theoretical differentiation in Generation Z in terms of AI knowledge, application and value orientation empirical foundation. Therefore, the residual analysis was not only a diagnostic instrument but an interpretative interim between statistical modelling and heterogeneity of behaviors in the Hospitality 5.0 setting [79]. In order to enhance interpretative clarity while maintaining methodological transparency, a subsample of 20 respondents is presented. Although the total number of respondents included in the analysis is considerably larger, this number is sufficient for illustrative purposes, allowing for qualitative comparisons between actual and predicted values and demonstrating representative cases across all identified categories. The presentation of a limited number of units within residual analysis and model diagnostics is a common research practice when the aim is not statistical generalization, but rather the demonstration of the classification logic and the visualization of differences in predictive patterns [79,80]. Based on the degree of deviation, respondents were classified into three groups: those aligned with the model, whose predicted and actual values were very close; “overperformers,” whose actual values were significantly higher than expected; and “underperformers,” whose actual values were lower than the model’s predictions. This classification provides insights into how individual variations contribute to the overall predictive accuracy of the model and opens space for exploring potential factors influencing these deviations. The results showed that 11.2% of respondents fell into the “overperformer” group, exhibiting significantly more positive attitudes toward sustainability in hospitality than would be expected based on their AI knowledge, skills, and attitudes. This phenomenon may be attributed to other latent factors, such as personal values, prior work experience, or strong environmental awareness. Approximately 10.6% of respondents were classified as “underperformers,” indicating potential barriers to applying AI knowledge in the domain of sustainability (Table 7).

Table 7.

Residual analysis and classification of observations based on predictive model accuracy.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the predicted and observed values of the latent variable Sustainability Attitudes, with respondents classified according to the degree of deviation in prediction. The black diagonal line represents the ideal match between the model’s expectations and actual outcomes. The visualization clearly reveals three distinct groups. Overperformers (marked in green) represent respondents whose attitudes toward sustainability are significantly stronger than the model predicted based on their AI knowledge, skills, and attitudes. This group may reflect the influence of additional motivational or value-based factors not directly captured by the model, but which positively affect support for sustainable practices. In contrast, underperformers (marked in red) display lower observed values than predicted, which may signal the existence of certain barriers to applying knowledge or a degree of skepticism toward sustainability, despite their demonstrated AI-related competencies. The majority of the sample (marked in gray) was classified as model-aligned, meaning that their observed values closely matched the model’s predictions, thereby confirming the stability and validity of the SEM model in predicting attitudes toward sustainability.

Figure 2.

Pillar contribution by group: Overperformers vs. Underperformers.

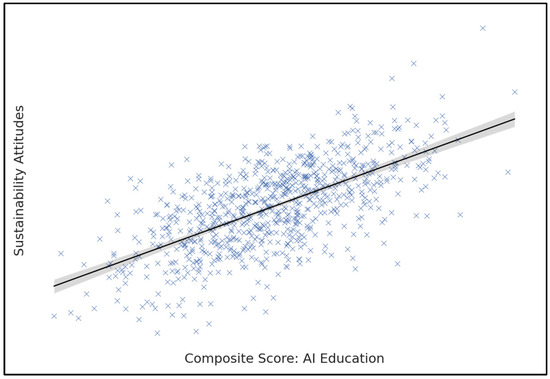

To visually depict the relationship between AI education and sustainability attitudes, a scatter plot with a regression line was created, where the X-axis represents the composite AI education score, and the Y-axis represents attitudes toward sustainability (Sustainability Attitudes).

This visualization provides a direct insight into the direction and strength of the relationship between the analyzed variables. The results clearly show a positive linear relationship: as the level of knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward AI (expressed through the composite score) increases, so does the level of support for sustainable practices in hospitality. The regression line, accompanied by a narrow confidence interval (depicted as a gray shaded area), confirms the stability and consistency of the trend. This finding supports the theoretical assumption that AI education among Generation Z not only enhances technical readiness for working in digitalized hospitality environments but also significantly contributes to the development of sustainability awareness. The visual analysis here serves as a complement to the quantitative results of the SEM model, further confirming the validity of the established regression relationships (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Scatter plot: composite score of AI Education vs. Sustainability Attitudes.

Although the results of the χ2 test (χ2(4) = 3.21, p = 0.466) did not show a statistically significant association between the field of study and respondents’ status in terms of deviations from model predictions (p > 0.05), the descriptive analysis reveals a recognizable pattern with interpretative value. Specifically, overperformers were identified exclusively among students of tourism and hospitality, and economics and management, which may indicate a stronger value orientation toward sustainability within these fields. These respondents exhibited higher outcomes than expected, even when the model, based on known predictors, did not anticipate a pronounced support for sustainable practices. Conversely, underperformers were found exclusively among students of IT and computer sciences, suggesting a possible disconnect between technical proficiency and the application of knowledge in the context of sustainable development. Although these individuals possess strong capacities in digital technologies, their attitudes toward sustainability fall below model expectations, indicating a need for stronger integration of technical education with value-based sustainability principles. It should be noted that the displayed results are based on a representative subset of respondents selected for illustrative purposes. Given the total sample size of 823 participants, only cases showing meaningful deviations, either as overperformers or underperformers, were included in this focused analysis. This approach, commonly used in residual diagnostics, aims not at statistical generalization, but at providing a clear visualization and interpretation of predictive patterns through selected representative examples [79,80] (Table 8).

Table 8.

Distribution of respondents by field of study and residual-based classification.

The results of the χ2 test indicate a statistically nonsignificant association between the type of AI education and deviations in respondent performance (χ2(4) = 6.00, p = 0.221); however, the observed patterns hold interpretative value and highlight relevant trends. Specifically, overperformers were identified exclusively among respondents who had received either informal or formal AI education, while no overperformers were found among those with no exposure to AI education. Conversely, the only underperformer in the sample originated from the group of respondents without any AI education, suggesting a limited capacity to apply knowledge toward forming sustainable attitudes among individuals who have not been exposed to any form of education in this field. Furthermore, the majority of model-aligned respondents, those whose actual values matched the model’s predictions, came from the group with formal AI education. This suggests that systematic, institutionally structured training contributes to a more stable adoption of expected behavioral patterns and values related to sustainability (Table 9).

Table 9.

Profile analysis by type of AI education.

5. Discussion

The results of this study confirm the thesis that education about artificial intelligence (AI) is a key factor in shaping sustainability attitudes among members of Generation Z within the context of Hospitality 5.0. In addition to the numerical validation of the postulated relationships, the discussion provides a more global theoretical insight into the role of AI education in the formation of sustainable orientations among the representatives of Generation Z. The results support the original assumption of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), though they also expand it by incorporating dimensions of value and normative that are in line with the Value Belief Norm (VBN) theory. Although the TAM has conventionally used perceived usefulness and ease of use to explain a behavioral intention, the present study proves that an additional determinant of pro-sustainability attitudes is ethical and ecological literacy, which is developed as a result of AI-related education. The hybridization of TAM and VBN frameworks is consistent with the concept of Hospitality 5.0 [29] where technology is not merely a functional innovation, but a way to transform culture and morality as well. Hence, the outcomes do not only substantiate the statistical powers of associations, but also contribute to the theoretical knowledge on how education can transform digital competence into a sustainable behavioral transformation. The results should also be explained within the framework of a certain socio-cultural and institutional context of Istanbul where certain traditional educational patterns and the rapid digitalization of the hospitality service set a new learning environment. The application of AI in hospitality in Istanbul is also highly mediated by cultural values, priorities in public policies, and unequal access to technology, unlike in Western European cities [84]. This implies that the sustainability attitude that is observed in Generation X is the result of not only personal educational experience but also contextual factors, including social trust in technology, policy incentives on digital education, and community-based norms on sustainability. Within the same style as socio-technical research [63], the presence of an interaction between institutional support and personal digital preparedness seems to be of paramount importance in the formation of consistent sustainability orientations.

Contrary to the initial assumptions, self-assessed AI knowledge showed a significant positive impact on the formation of sustainable attitudes, aligning with the findings of [35] who emphasize that experiential education enhances both technical readiness and students’ ecological orientation.

The practical application of AI technologies emerged as the strongest predictor of support for sustainable practices, further confirming the arguments of [28,32] regarding the necessity of integrating humanistic values into technological education. The findings clearly demonstrate that hands-on experience with AI tools enables a deeper understanding of their role in enhancing energy efficiency, resource management, and environmentally responsible business practices, also supporting the observations of [34] about the importance of connecting practical and value-based education.

Positive value orientations toward AI, as the third dimension examined, also significantly contributed to sustainable attitudes, aligning with [40] findings that Generation Z exhibits strong declarative support for sustainable development goals. However, the results of the additional residual analysis reveal a more complex picture: the presence of overperformers and underperformers indicates that high technical knowledge does not necessarily guarantee strong sustainability attitudes, as previously suggested by [44]. When compared to previous studies conducted in Istanbul [54,55], it becomes evident that, although there is a positive attitude toward AI technology implementation, the lack of systematic integration of sustainability values within educational programs limits the full development of sustainability-oriented digital competencies. This finding also supports the critique made by [13] that technical education often remains isolated from value-based aspects.

Specific differences by field of study further illustrate these dynamics: overperformers were more frequently identified among tourism and management students, which is consistent with [40] findings that service-oriented sectors tend to foster stronger ecological awareness. Conversely, underperformers were predominantly from IT fields, confirming the claims of [9] regarding the insufficient linkage between technical education and sustainability. In addressing the first research question (RQ1), the results indicate that different forms of AI education, formal, informal, and the absence thereof, have differentiated effects on the formation of sustainability attitudes. Formal education proved to be the most effective in aligning technical competencies with value-based attitudes, which is consistent with the conclusions of [29] regarding the importance of institutionally structured education for developing sustainable digital competencies.

Regarding the second research question (RQ2), the analysis of deviations from theoretical predictions reveals that individual differences in AI knowledge, application, and value-based orientations significantly shape behavioral patterns. Overperformers, who demonstrate a strong sustainability orientation despite modest AI knowledge, and underperformers, whose technical readiness is not accompanied by value-based commitment, underscore the complexity of the relationship between educational inputs and normative outputs, further highlighting the insights of [47]. In a broader context, these findings confirm that Istanbul, as an urban laboratory of digital transformation [12], provides unique insights into the challenges and opportunities of connecting AI education with sustainability. The fragmented implementation of AI in the hospitality sector, coupled with insufficient institutional support for sustainability education [57], further complicates the integration of technological and value-based competencies, yet simultaneously opens avenues for strategic interventions.

Moreover, although this study proves that AI education increases the level of sustainability awareness, it also indicates that the attitude–behavior gap, which is a long-standing phenomenon in social psychology, is still present [85,86]. Even in cases when people have high pro-sustainability attitudes, they do not necessarily play out in environmentally responsible behavior. The implication of the said finding is that curriculum design must go beyond cognitive and technical competencies, and include mechanisms of behavioral reinforcement like experiential learning, collaboration with peers, and institutional rewards of sustainable behavior.

6. Conclusions

This study confirms that education about artificial intelligence plays a crucial role in shaping sustainable attitudes among members of Generation Z within the context of Hospitality 5.0. Nevertheless, the findings should be interpreted with caution, because Istanbul is a specific socio-cultural environment, and the education system is of a transitional nature, which might have influenced the reactions of the participants. Future studies may investigate the role of institutional differences between universities where engineering and hospitality are the focus in the mediation of the relationship between AI education and sustainability values. By connecting technical knowledge, practical skills, and value-based orientations, the research revealed that both formal and informal AI education significantly contribute to the development of sustainability awareness, while the absence of education can lead to insufficiently expressed normative attitudes. The original contribution of this study lies in the integration of educational and value-based dimensions into a model for understanding the relationship between AI and sustainability, representing a theoretical advancement over existing approaches that have predominantly favored technical or operational aspects of digital transformation. In doing so, the study enriches the global body of knowledge on the role of Generation Z in the transition of the hospitality industry toward sustainable business models. This research is particularly relevant to academics, researchers in the fields of tourism, hospitality, education, and information technologies, as well as to policymakers and hospitality industry managers. Its value lies in providing empirically grounded insights that can serve as a foundation for curriculum redesign, the development of professional training programs, and the enhancement of sustainable development strategies within the industry.

Given that the research was conducted in Istanbul, a highly digitalized urban environment characterized by complex cultural dynamics, the findings also have the potential for application in other regions undergoing similar processes of digital and sustainable transformation, including cities in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America. The use of a multilayered methodological approach, incorporating factor analysis, structural modeling, and residual analyses, enabled a reliable validation of the model and a precise understanding of the complexity of the relationship between AI education and sustainability attitudes. The results were presented clearly and interpretably, making them accessible even to readers without an expert background in statistical modeling.

The significance of this study lies in its contribution to the development of new educational strategies that integrate technical and value-based competencies, as well as in opening avenues for redefining industry practices toward sustainable digital hospitality. It is expected that this work will impact academic research by laying the groundwork for future studies on the value-based formation of digitally literate professionals, while also contributing to industrial practice by supporting the development of innovative models of employment, education, and sustainable management. For these reasons, this study can be recommended to students, researchers, and practitioners as a reference that raises new questions and offers concrete solutions for the challenges of contemporary education and sustainability.

Although the research proves the fact that AI-based personalization is capable of improving tourist satisfaction and service quality, it must not be assumed that such an impact is unconditional technological optimism. Practically, there are still limitations to the application of AI systems in the hospitality sector connected to the protection of data, the transparency of algorithms, and the ethical responsibility. Thus, the beneficial effect of AI personalization is based on the conscientious development and use of such tools in open, humanistic structures. In comparison to the pre-AI setting, where the personalization was performed primarily based on the intuition of the staff and the use of databases that were not dynamic, the systems supported by AI will allow responding to the preferences of the users and the conditions that the context implies in real-time, which outperforms the efficiency of the work considerably. Nevertheless, such advances need to be offset with continuous ethical surveillance and institutional control in order to maintain that personalization contributes to user trust and green hospitality practices. The findings also demand the creation of context-specific strategies in Hospitality 5.0 learning. In particular, real-life sustainability initiatives, ethical role-playing, and intersectoral collaboration with hotels and technology companies should be introduced in the curricula, thus allowing students to move the awareness of sustainability to a level of behavioral participation. By instilling sustainability in formal and informal AI learning settings, educational establishments can make sure that the Generation Z not only learns the principles of sustainability but also puts them into practice.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The repositioning of AI education as a transformative mechanism within the theoretical framework of Hospitality 5.0 is what makes this study unique. This research suggests a conceptual shift by viewing education as a cognitive and normative process that mediates the relationship between technological readiness and sustainability behavior, in contrast to earlier studies that have only addressed digital literacy or technology adoption. The study theoretically expands the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) toward a framework of sustainable technology adoption integrated in values by introducing the categories of overachievers and underachievers. This strategy enables the Hospitality 5.0 paradigm to advance from technical optimization to a human-centered theory of digital transformation that incorporates sustainability, ethics, and education.

This research makes a significant theoretical contribution by expanding the concept of Hospitality 5.0 by integrating educational and value-based components into the analysis of technology acceptance in the hospitality sector. Previous models [15,32] mainly focused on technical and operational aspects of digital transformation, while this research shows that technical literacy, if not accompanied by the development of ecological and ethical awareness, cannot result in the formation of sustainable patterns of behavior. This opens a new theoretical field that requires the systematic integration of normative education into models of technology acceptance [34], which represents an important direction for future researchers interested in the connection of digital literacy, value systems and sustainability in tourism and hospitality.

Additionally, the identification of categories of overperformers and underperformers contributes to the theoretical refinement of the understanding of individual differences within Generation Z, building on earlier findings on digitally literate cohorts [40] and highlighting the complexity of the relationship between knowledge, practical skills and value orientation. This approach contributes to the development of more advanced theoretical models that no longer view young technology users as a homogeneous group, but as a differentiated population in which sustainable values are the result of different educational and experiential paths. In this way, the research advances the understanding of the connection between AI education, value systems and sustainable behaviors within the concept of Hospitality 5.0.