Abstract

The persistent gap between consumers’ pro-environmental attitudes and their sustainable behavior continues to challenge both scholars and practitioners. While social norms are often viewed as a lever for encouraging sustainable behavior, empirical results remain inconsistent. This paper develops a conceptual model of sustainable behavior that integrates insights from prior research on social norms, culture, and self-construal. Specifically, the paper links social norms, self-construal, macro-culture, and environmental awareness to explain their combined influence on sustainable behavior. Drawing from social norms theory, self-construal theory, cross-cultural psychology, and environmental psychology, the model proposes that appeals combining specific types of norms (injunctive vs. descriptive) with targeted self-construal activation (independent vs. interdependent) can strengthen purchase intentions, moderated by cultural context and environmental awareness. Eight testable propositions that distinguish established effects from novel extensions are advanced, thereby clarifying boundary conditions and guiding future empirical testing. By synthesizing insights from fragmented literature, the framework positions social norms as the central explanatory construct and provides practical guidance for designing culturally attuned, norm-based sustainability communications.

1. Introduction

The urgency of addressing climate change, resource depletion, and environmental degradation has intensified scholarly interest in sustainable consumer behavior. While consumers often express concern for the environment and support for sustainable products, actual adoption remains modest. This phenomenon is widely described as the attitude–behavior gap [1,2,3]. Scholars have long sought to understand how communications and interventions might bridge this gap, and appeals to social norms have been a central focus [4,5]. Social norms, defined as “cultural rules that guide behavior within a society” [6] (p. 105), can influence consumer choices by signaling what is typical (descriptive norms) or what is socially approved (injunctive norms). However, research has yielded mixed findings: some studies report strong effects on pro-environmental intentions and behaviors (e.g., [7]) while others find little or no impact, particularly in complex purchase decisions [8].

Prior research has investigated parts of our model in isolation. Social norms have been widely studied as predictors of sustainable consumer behavior, with mixed findings regarding their impact on actual adoption (e.g., [9,10,11]). Self-construal has been examined primarily as a moderator shaping responses to persuasive appeals (e.g., [12,13]), while macro-cultural dimensions have been shown to influence pro-environmental attitudes and values at a societal level (e.g., [14,15]). Yet, these constructs have rarely been integrated, and the literature provides inconsistent results on whether self-construal and culture operate as moderators, mediators, or independent drivers. Our model builds on these insights by addressing the inconsistency in how these constructs have been conceptualized across studies and responds to calls for more integrative approaches [5,16,17] that explain when and why social norms influence sustainable behavior.

One explanation for these inconsistencies is the interaction between social norms and self-construal, the way individuals perceive themselves in relation to others [18]. Individuals with an interdependent self-construal tend to value connectedness and group harmony, making them more receptive to normative influence [5,19,20]. In contrast, those with an independent self-construal emphasize autonomy and personal choice, and may perceive injunctive norms as threats to their freedom [21,22,23].

Both interdependent and independent self-construal exist across cultures, but cultural context influences which of these is more dominant and how individuals respond to normative appeals. Macro-level cultural values, such as individualism versus collectivism [24] or societal environmental awareness [25], may therefore moderate the persuasiveness of norm-based interventions. Integrating these macro-cultural factors with micro-level psychological variables can help explain the variability in the effects of social norms and guide the design of interventions with greater impact.

As a conceptual paper, the present study does not aim at empirical validation. Instead, following established guidelines for conceptual contributions [26,27,28,29,30], its value lies in integrating fragmented perspectives, enhancing construct clarity, and developing theoretically grounded propositions to guide future empirical research. Specifically, the paper advances an integrative framework linking social norms, self-construal, macro-culture, and environmental awareness to sustainable behavior. Drawing on insights from social psychology, cross-cultural research, and environmental psychology [5], it synthesizes existing theoretical perspectives and formulates eight propositions to explain the combined influence of these constructs on sustainable behavior.

Taken together, this study makes a twofold contribution. First, it explicitly models self-construal and macro-culture as moderators that condition the effects of social norms, thereby clarifying inconsistent findings in prior research where these constructs were variously treated as mediators, moderators, or independent drivers. Second, it integrates individual-level psychology, cultural context, and environmental awareness into a unified framework, something that, to the best of our knowledge, has not yet been offered in the sustainability literature. This cross-level integration addresses a clear gap and offers a platform for targeted empirical investigations.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Conceptual Approach

The review by Saracevic and Schlegelmilch [5] synthesized two decades of research on the role of social norms in pro-environmental behavior, with particular emphasis on the moderating roles of culture and self-construal. It concluded that while social norms represent a central explanatory construct, prior findings remain fragmented across disciplines, norm types, and cultural settings.

Building on this foundation, the present paper extends the discussion by developing an integrative conceptual framework. Specifically, we combine insights from social norms theory, self-construal theory, cross-cultural psychology, and environmental psychology into a structured model that generates testable propositions. This approach positions social norms as the central explanatory construct while systematically incorporating cultural and psychological moderators.

Our framework advances prior norm-framing work in three ways. First, it integrates macro-culture, self-construal, and environmental awareness into a single model of sustainable consumer behavior. Second, it specifies boundary conditions, highlighting contexts where sustainability motives compete with other considerations and where cultural or situational factors moderate effects. Third, it distinguishes between well-established relationships and novel extensions, thereby clarifying our incremental contribution.

To provide the theoretical basis for this framework, the following subsections briefly introduce its four core components: social norms, self-construal, macro-culture, and environmental awareness.

2.1. Social Norms

Social norms are informal, socially shared rules that guide behavior in the absence of formal legal enforcement [31]. In consumer research, injunctive norms convey what others believe one ought to do, while descriptive norms indicate what most people actually do [32,33,34]. Both types have been shown to influence diverse pro-environmental behaviors, including hotel towel reuse [7], energy conservation [35,36], litter prevention [32], recycling and green product purchases [37,38], plastic bag reduction [39], packaging choices [40], and responses to environmental marketing claims [41].

Despite this evidence, the effectiveness of norm-based appeals varies across behaviors, contexts, and populations. Some studies find robust effects, while others report no impact or effects limited to intentions [8,22,42]. Social norms may also backfire when poorly matched to the audience, producing boomerang effects that inadvertently legitimize undesirable behaviors [43]. Their influence is embedded in an individual’s immediate social environment, such as family, peers, and colleagues, where group identity and interpersonal interactions shape both expectations and responses [33].

In the proposed model, social norms do not operate in isolation; their impact is shaped by macro-culture and self-construal, and is further amplified by environmental awareness, which, together, drive sustainable behavior.

2.2. Self-Construal

Self-construal refers to how individuals define and interpret themselves in relation to others [18]. Two primary orientations are identified: independent self-construal, emphasizing uniqueness and autonomy, and interdependent self-construal, emphasizing connectedness, social harmony, and collective goals [44]. While generally stable, self-construal can be activated through priming [45,46].

Interdependent self-construal is associated with greater receptivity to both injunctive and descriptive norms, as it reinforces in-group belonging and social obligations [44,47]. Conversely, independent self-construal can lead individuals to resist externally imposed norms, especially injunctive ones [21,22,23]. Message framing, for example, through pronoun use (“we” vs. “I”), emphasis on group harmony vs. personal achievement, or culturally resonant imagery, can prime particular self-construal orientations and enhance message effectiveness [48,49].

Within the model, self-construal functions as a key moderator linking cultural values and social norms to pro-environmental intentions. To this end, self-construal shapes whether individuals accept or resist normative cues.

2.3. Macro-Culture

Cultural values at the societal level influence the salience and interpretation of social norms [50]. Among Hofstede’s [24] dimensions, individualism–collectivism is particularly relevant. Collectivistic cultures emphasize conformity and may respond more strongly to injunctive norms, whereas individualistic cultures value autonomy and may resist injunctive norms while still responding to descriptive ones [51]. While several Hofstede dimensions may indirectly shape norm effects, our model concentrates on individualism–collectivism and on cultural tightness–looseness as proposed by Gelfand et al. [52], as these constructs are most directly linked to the salience, strength, and enforcement of social norms.

2.4. Environmental Awareness

Environmental awareness refers to the degree to which individuals recognize environmental problems and understand their causes and consequences. In this study, it is conceptualized as a cognitive–affective construct, encompassing both knowledge of environmental issues and emotional concern for ecological well-being. Consistent with prior research (e.g., [53]), environmental awareness is treated as distinct from behavioral intention, which represents the conative or action-oriented dimension of sustainable behavior. Accordingly, conative elements are excluded to prevent criterion contamination and to maintain a clear separation between antecedents (awareness) and outcomes (intentions or behaviors).

Higher levels of environmental awareness are generally associated with stronger pro-environmental attitudes and greater receptivity to norm-based appeals, as awareness enhances the perceived relevance of sustainability issues [54,55]. However, this relationship is often moderated by situational constraints and perceived consumer effectiveness [56]. Within our proposed model, environmental awareness functions as an amplifier of normative influence, increasing the motivational salience of social norms without overlapping with the outcome variables of sustainable behavior or intention. Empirical work could therefore operationalize awareness through validated scales capturing cognitive and affective dimensions (e.g., knowledge, concern), keeping it conceptually separate from the behavioral intentions the model aims to explain.

Taken together, the constructs social norms, self-construal, macro-culture, and environmental awareness form the foundation of the proposed conceptual model. The model positions social norms as the central behavioral influence, with macro-level cultural values and self-construal shaping how norms are interpreted and acted upon. Environmental awareness, in turn, heightens the personal relevance of normative cues. This multi-level framework provides a basis for the eight propositions that follow, offering a structured agenda for future empirical research on sustainable behavior.

3. Conceptual Model and Propositions

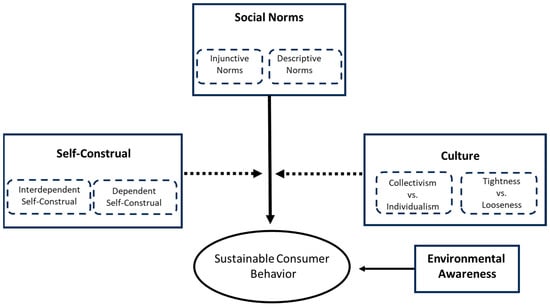

Building on the four constructs outlined above, this study develops eight propositions. These propositions specify how combinations of norm type, self-construal activation, macro-cultural context, and environmental awareness jointly influence sustainable consumer behavior (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model integrating self-construal, macro-cultural context, and environmental awareness as moderators and amplifiers of normative appeals influencing sustainable behavior.

Social norms constitute the central explanatory construct in Figure 1. Self-construal and macro-culture are conceptualized as moderators that shape the strength and direction of normative influence, while environmental awareness functions as a cognitive–affective amplifier that heightens the personal salience of sustainability issues. This conceptualization explicitly separates awareness from behavioral intention to avoid criterion overlap and to ensure conceptual clarity across the framework.

The decision to conceptualize self-construal and macro-culture as moderators rather than mediators rests on both theoretical reasoning and empirical evidence. Previous studies often treated these constructs as boundary conditions that shape the strength and direction of relationships rather than as explanatory mechanisms in their own right. For instance, it has been shown that individual versus collective cultural environments moderated responses to advertising appeals [12], while cultural tightness–looseness has been found to condition the effect of norms on compliance [52]. At the same time, there is some evidence of mediating roles, particularly for self-construal in shaping identity processes (e.g., [18]). The inconsistent findings in the literature underscore the need for a more systematic conceptualization.

Our contribution lies in integrating these variables into a unified framework. While prior research has explored them in fragmented ways, few studies have jointly examined the interplay of social norms, self-construal, macro-culture, and environmental awareness in the context of sustainable consumer behavior. By modeling self-construal and macro-culture as moderators, we emphasize their role as contextual and psychological conditions under which social norms are more or less effective. By including environmental awareness as an amplifier, we extend beyond previous dichotomous treatments of awareness as simply “present or absent.”

This integrative approach addresses two critical gaps: (1) the lack of cross-level models that connect individual psychological factors with broader cultural structures in shaping sustainable consumption, and (2) the absence of clarity in the literature on the conditions under which social norms translate into behavior. In this sense, our model offers a novel synthesis and provides a foundation for more targeted empirical investigations.

Independent self-construal emphasizes autonomy, uniqueness, and personal choice [44]. Individuals high in independence may resist prescriptive messages if perceived as limiting their freedom [21]. However, when injunctive norms are framed to highlight personal benefits or align with self-determined values, they can still motivate sustainable behavior [11]. Prior research shows that norm–self-construal congruence enhances persuasiveness, suggesting that matching independent orientations with carefully framed injunctive norms can strengthen behavioral intentions [31]. For illustrative purposes, each proposition is accompanied by an example from sustainable consumption, although the conceptual model applies broadly to other forms of sustainable behavior.

P1: Building on prior research, appeals combining independent self-construal activation with injunctive norms enhance sustainable behavior compared to messages without such appeals.

Example: Injunctive norms emphasizing personal responsibility for sustainable consumption can reinforce independent self-construal by aligning moral approval with individual choice.

Interdependent self-construal prioritizes connectedness, group harmony, and fulfilling social obligations [44]. Such individuals are more receptive to injunctive norms, as these communicate socially approved behaviors consistent with group values [20]. Studies on pro-environmental messaging show that appeals highlighting community approval and moral expectations can be effective in interdependence-dominant audiences [32]. This alignment between social approval cues and self-views increases the likelihood of sustainable behavioral intentions:

P2: Building on prior research, appeals combining interdependent self-construal activation with injunctive norms enhance sustainable behavior compared to messages without such appeals.

Example: Injunctive norms that highlight collective approval for sustainable consumption can strengthen intentions among interdependence-oriented consumers.

Descriptive norms convey information about what others typically do [32], providing a behavioral benchmark. For individuals with independent self-construal, descriptive norms framed as voluntary trends can be persuasive without threatening autonomy [11]. Presenting sustainable behaviors as common among peers can signal social relevance and sophistication while appealing to an independent self-view:

P3: Extending prior work, appeals combining independent self-construal activation with descriptive norms enhance sustainable behavior compared to messages without such appeals.

Example: Descriptive norms emphasizing the popularity of sustainable products can enhance the appeal of environmentally friendly choices for independence-oriented consumers.

Interdependent individuals are motivated by belonging and social alignment, making them particularly sensitive to descriptive norms that signal in-group behaviors [20]. When sustainable practices are presented as common within their community or reference group, this reinforces conformity and social identity [33]. Such norms can activate a desire to maintain group cohesion and avoid social disapproval, thereby increasing intentions to engage in similar pro-environmental actions:

P4: Extending prior work, appeals combining interdependent self-construal activation with descriptive norms enhance sustainable behavior compared to messages without such appeals.

Example: Descriptive norms showing that sustainable purchases are common within a valued social group can increase conformity among interdependence-oriented consumers.

Interdependent self-construal strengthens receptivity to both injunctive and descriptive norms due to its emphasis on social harmony and collective benefit [44]. In sustainability contexts, interdependence primes greater alignment with group-endorsed behaviors, whether they are prescriptive (injunctive) or representative (descriptive) [5]. This suggests that interdependence not only supports the uptake of norms but may amplify their influence beyond that of independence-oriented frames:

P5: Novel integration, interdependent self-construal activation amplifies the effect of both injunctive and descriptive norm appeals more strongly than independent self-construal activation.

Example: Interdependent self-construal can amplify the persuasive effect of both injunctive and descriptive appeals by reinforcing collective motivation for sustainable consumption.

Cultural values shape responses to normative appeals. Collectivistic societies, where interdependence is more prevalent, tend to place greater emphasis on conformity and group-endorsed behaviors [57]. Consequently, both injunctive and descriptive norms are likely to have stronger persuasive effects in collectivistic than in individualistic settings. In such cultures, sustainable consumption framed as a shared social responsibility is likely to resonate more strongly than in cultures that prioritize personal choice and autonomy.

P6: Extending prior work, norm-based appeals are more effective in collectivistic cultures than in individualistic cultures.

Example: In collectivistic settings, normative messages that stress shared social responsibility for sustainable consumption are likely to be more persuasive than in individualistic contexts.

In addition to collectivism–individualism, cultural tightness–looseness provides an important contextual lens [52]. Tight cultures, characterized by strong social monitoring and sanctioning, tend to reinforce the persuasiveness of injunctive norms, whereas loose cultures, which tolerate greater behavioral diversity, may heighten the relevance of descriptive norms. These dynamics can be further conditioned by self-construal (e.g., interdependence amplifying injunctive effects in tight contexts, independence enhancing descriptive effects in loose contexts) and by environmental awareness, which can strengthen both types of appeals in culturally specific ways.

P7: Extending prior work, injunctive norm appeals exert stronger effects in tight cultures, while descriptive norm appeals exert stronger effects in loose cultures.

Example: In tight cultures, injunctive appeals emphasizing social approval for sustainable consumption are especially effective, whereas in loose cultures, descriptive cues about prevalent behavior gain greater traction.

Environmental awareness increases the salience of sustainability-related norms [56]. Individuals with higher awareness are more likely to recognize the personal and societal relevance of environmental issues, making them more receptive to norm-based appeals [58]. Awareness can act as an amplifier by strengthening the cognitive and emotional link between normative cues and pro-environmental intentions [55].

P8: Novel extension, norm-based appeals are more effective among individuals with higher environmental awareness than among those with lower environmental awareness.

Example: Higher environmental awareness enhances responsiveness to both injunctive and descriptive norms, increasing the likelihood of sustainable consumption decisions.

4. Theoretical Contributions

This paper integrates multiple theoretical perspectives into a unified framework. It addresses inconsistencies in norm-based persuasion research and advances the view of self-construal as an activatable state. In addition, it conceptualizes environmental awareness as a cognitive–affective amplifier that heightens the salience of sustainability issues, thereby strengthening the influence of normative appeals and providing directions for future empirical testing. More specifically, self-construal operates as a psychological filter through which normative cues are interpreted, with interdependent orientations amplifying receptivity to both injunctive and descriptive norms, while independent orientations may trigger resistance unless messages are framed to align with personal values. At the same time, macro-cultural values shape the salience of these interpretations, and environmental awareness acts as an amplifier that increases the motivational force of norms, thereby jointly structuring the pathways from normative appeals to sustainable behavior. Together, these contributions provide a richer understanding of how contextual and individual-level factors interact to influence sustainable behavior. In addition, this model advances understanding by explicitly integrating insights from social psychology, particularly norm theory [31], with cross-cultural marketing research in the sustainability context [5,57]. By incorporating the cultural tightness–looseness framework [52] alongside individualism–collectivism [24], the model provides a richer lens for predicting when injunctive or descriptive norms will be most effective across cultural contexts. While our model highlights these two dimensions most prominently, it is designed to be flexible and can accommodate additional cultural factors such as uncertainty avoidance, power distance, or masculinity–femininity where relevant. This adaptability enhances its applicability in multicultural scenarios without undermining conceptual parsimony.

Our approach responds to recent calls for interdisciplinary approaches to address the complex nature of sustainable consumer behavior [59,60]. Furthermore, the conceptualization of self-construal as both a stable trait and a state that can change depending on the situation extends prior work [44,48] by highlighting its dynamic interaction with macro-cultural variables. Taken collectively, the proposed model contributes to a more nuanced theoretical understanding of how cultural and individual factors jointly shape normative influence and, by doing so, advances the debate on how to close the attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption.

5. Managerial Insights and Practical Applications

The proposed model can serve as a conceptual guide for marketers and policymakers interested in promoting sustainable behavior. Future interventions could explore matching the type of norm to an audience’s self-construal and activating self-construal strategically. Campaigns could be aligned with cultural context and use environmental awareness as an amplifier. In addition, audiences could be segmented by psychological and cultural profiles to potentially increase the impact of sustainability messages.

From a practical standpoint, the model may help managers design sustainability messages that align with both the prevailing cultural values and the audience’s predominant self-construal [23,61]. For example, in tight, collectivistic cultures, injunctive norms framed around community approval may resonate strongly, whereas in loose, individualistic cultures, descriptive norms highlighting widespread adoption might be more persuasive [51]. Segmentation strategies could also consider environmental awareness levels, enabling the development of differentiated campaigns for high- and low-awareness segments [58].

To mitigate the risk of norm fatigue, where repeated exposure to similar messages reduces their impact [43], marketers might experiment with dynamic, adaptive campaigns that refresh normative content over time and across channels. In addition, managers should remain cautious that norm-based appeals are not universally beneficial. Excessive repetition or poorly targeted normative messages could trigger psychological reactance, skepticism, or outright resistance, thereby undermining campaign goals. Such “boomerang effects” may occur if messages legitimize undesirable behaviors, appear manipulative, or conflict with an individual’s self-construal. To minimize these risks, practitioners might focus on calibrating both the frequency and framing of normative information, tailor messages to culturally and psychologically relevant audiences, and integrate variety and personalization to sustain engagement over time.

While the preceding section outlines how the proposed model may inform practical communication strategies, further empirical research is needed to validate and refine these conceptual relationships. The following section therefore highlights key directions for future research.

6. Future Research Directions

As with all conceptual papers, the present study does not include empirical testing. Consequently, a natural next step for future research is the empirical validation of the proposed integrative model. Such work could employ Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the relationships among the constructs and Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) to assess the cross-cultural moderation effects implied by the framework. These methods would provide a robust approach for testing the model’s propositions and evaluating its applicability across different cultural contexts.

Future studies should pursue several avenues to extend and empirically validate the proposed model. First, systematic cross-cultural testing is essential to examine how combinations of norm type, self-construal, and the amplifying role of environmental awareness operate in diverse cultural contexts. Comparative research could identify whether certain cultural dimensions, such as collectivism versus individualism or cultural tightness versus looseness, consistently moderate the persuasiveness of specific norm–self-construal pairings. For example, future research could compare contexts that differ markedly along these dimensions. A comparison between China and the United States would allow testing across tight versus loose cultural settings, while contrasting Germany and India would capture differences in individualism–collectivism. To strengthen validity, such studies should also control for potential confounding variables beyond culture, including socioeconomic status, education levels, the stringency of environmental regulations, or the degree of media exposure to sustainability issues. These illustrations are not exhaustive, but they provide a concrete starting point for operationalizing cross-cultural designs and offer subsequent researchers a more actionable blueprint.

Second, longitudinal designs would be valuable to track how self-construal, environmental awareness, and responsiveness to norms evolve over time, particularly in response to sustained interventions, such as multi-year public campaigns, continuous school-based environmental programs, or long-term corporate sustainability initiatives. Such research could reveal whether the model’s relationships are stable or contingent on temporal dynamics, life stages, or shifting socio-environmental conditions.

Third, future work should move beyond self-reported intentions and measure actual sustainable behaviors in real-world settings. Field experiments, natural experiments, and behavioral tracking through digital platforms can offer more robust evidence on the causal links proposed in this model.

Fourth, communication channel effects merit deeper investigation. Studies could compare the influence of digital platforms, social media influencers, traditional advertising, and interpersonal advocacy in delivering norm-based appeals. This line of research should also examine how message framing interacts with self-construal activation and cultural orientation across different media.

Fifth, generational and demographic differences offer another promising direction. Younger cohorts, for example, may exhibit higher receptivity to descriptive norms in online environments, whereas older generations might respond more strongly to injunctive norms framed in traditional channels [62].

Sixth, contextual moderators should be more systematically incorporated into empirical investigations. Factors such as cultural values, regulatory environments, or market maturity may shape how social norms, self-construal, macro-culture, and environmental awareness interact in influencing sustainable consumption. Explicitly modeling such moderators would deepen understanding of the boundary conditions of the proposed framework and help explain why certain interventions succeed in some contexts but fail in others.

Seventh, situational contingencies of the attitude–behavior gap deserve closer attention. The relative influence of social norms, self-construal, macro-culture, and environmental awareness may not be uniform across all consumption contexts. For example, the drivers of sustainable behavior could differ markedly between high-involvement and low-involvement green products, or between utilitarian versus identity-laden product categories. Examining such contingencies would enhance the specificity and practical relevance of the framework, allowing researchers and practitioners to design interventions that are better tailored to the types of sustainable consumption decisions where they can have the greatest impact.

Finally, emerging technologies such as AI-driven personalization create opportunities for tailoring messages to an individual’s momentary self-construal, cultural background, and awareness level. Mixed-method designs combining large-scale quantitative testing with qualitative exploration could uncover the psychological mechanisms behind acceptance or resistance to such adaptive interventions.

By pursuing these research directions, scholars can help refine the model. Most importantly, they can provide actionable insights for designing culturally attuned, psychologically informed, and technologically enhanced strategies to close the attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption. To support future empirical testing, it will be important to adopt clear and consistent operationalizations of the model’s core constructs. For instance, self-construal may be measured using established scales such as Singelis [18], while cultural context can be captured using widely applied frameworks such as Hofstede [24] or Gelfand [52] on cultural tightness–looseness. Environmental awareness can be operationalized following validated instruments that assess cognitive, affective, and conative components (e.g., [53,56]), and normative influences can be measured through scales developed by Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren [32] and subsequent refinements. To avoid construct overlap, future studies should distinguish environmental awareness from behavioral intentions by focusing on knowledge and concern as antecedents, while treating intention as a separate dependent variable. Moreover, given that the model combines societal- and individual-level constructs, future empirical work should adopt multi-level research designs. Nesting individual-level data within cultural contexts and modeling cross-level interactions (e.g., through hierarchical linear modeling) would help avoid ecological fallacy and ensure that societal- and individual-level influences are correctly specified.

Finally, future studies should also investigate the boundary conditions and potential downsides of norm-based appeals. For instance, excessive repetition of normative messages may lead to “norm fatigue,” reactance, or even boomerang effects that reduce rather than increase sustainable behavior. Exploring when and why such negative outcomes occur would enhance both the theoretical completeness and the practical usefulness of the framework, ensuring that interventions are designed not only for maximum impact but also for long-term credibility and acceptance.

7. Conclusions

This conceptual model offers a theoretically grounded approach to enhancing sustainable consumer behavior through norm-based appeals matched to self-construal, cultural values, and environmental awareness. It provides both a research agenda and actionable insights for practitioners, moving towards narrowing the gap between sustainable attitudes and sustainable behavior. In summary, the proposed conceptual model bridges theoretical perspectives from social norms, self-construal, and cross-cultural research to address the enduring attitude–behavior gap. Its interdisciplinary nature strengthens its relevance to both scholars and practitioners, offering testable propositions and actionable insights for tailoring sustainability communications. Looking ahead, empirical testing of the model across diverse cultural and product contexts will be critical to refining its predictive power and practical utility.

In doing so, this paper directly responds to calls in the literature, including an earlier review in Sustainability [5], for frameworks that move beyond fragmented evidence and place social norms at the center of explanations of sustainable behavior. By highlighting the interplay of social norms with culture, self-construal, and environmental awareness, the proposed model provides a theoretically grounded basis for future empirical validation and practical application, serving as a conceptual foundation for subsequent empirical research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.S. and S.T.; visualization, B.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.S.; writing—review and editing B.B.S. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Bualuang ASEAN Chair Professor Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hulland, J.; Houston, M. The importance of behavioral outcomes. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Z.; Ren, Z.; Zhu, Z. Attitude-behavior gap in green consumption behavior: A review. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2022, 28, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorn, A. Why should I when no one else does? A review of social norm appeals to promote sustainable minority behavior. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1415529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracevic, S.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. The Impact of Social Norms on Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review of the Role of Culture and Self-Construal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H.L. Perspectives on Social Order; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristl, A.C.; Kilian, S.; Mann, A. When does a social norm catch the worm? Disentangling social normative influences on sustainable consumption behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, D.; Batzke, M.C.; Bläsing, T.M.; Gomera Deaño, S.; Helfers, A. Effectiveness and context dependency of social norm interventions: Five field experiments on nudging pro-environmental and pro-social behavior. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1392296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Schultz, P.W.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. Normative social influence is underdetected. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Rishad, H.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.P.; Shavitt, S. Persuasion and culture: Advertising appeals in individualistic and collectivistic societies. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 30, 326–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.Y.; Aaker, J.L.; Gardner, W.L. The pleasures and pains of distinct self-construals: The role of interdependence in regulatory focus. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 1122–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Schultz, P.W. Culture and the natural environment. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eom, K.; Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.K.; Ishii, K. Cultural variability in the link between environmental concern and support for environmental action. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 27, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.W.; Hong, Y.Y.; Chiu, C.Y.; Liu, Z. Normology: Integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2015, 129, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrighetto, G.; Vriens, E. A research agenda for the study of social norm change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2022, 380, 20200411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.; Xie, X.; Liu, C. Interdependent orientations increase pro-environmental preferences when facing self-interest conflicts: The mediating role of self-control. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bartels, J.; Antonides, G. Environmentally friendly consumer choices: Cultural differences in the self-regulatory function of anticipated pride and guilt. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronrod, A.; Grinstein, A.; Wathieu, L. Go green! Should environmental messages be so assertive? J. Mark. 2012, 76, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saracevic, S.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Wu, T. How normative appeals influence pro-environmental behavior: The role of individualism and collectivism. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 344, 131086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Simpson, B. When do (and don’t) normative appeals influence sustainable consumer behaviors? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Handayani, W.; Ariescy, R.R.; Cahya, F.A.; Yusnindi, S.I.; Sulistyo, D.A. Literature review: Environmental awareness and pro-environmental behavior. In Nusantara Science and Technology Proceedings, Proceedings of the 5th International Seminar of Research Month 2020, Kuching, Malaysia, 27 October 2020; Nusantara Science and Technology Proceedings: East Java, Indonesia, 2021; pp. 170–173. [Google Scholar]

- MacInnis, D.J. A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing conceptual articles: Four approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L.L.; Goldberg, C.B. Editors’ comment: So, what is a conceptual paper? Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.S. The decline of conceptual articles and implications for knowledge development. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R. Construct clarity in theories of management and organization: Editor’s comments. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M.R. Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; Gilbert, D.T., Fiske, S.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culiberg, B.; Elgaaied-Gambier, L. Going green to fit in–understanding the impact of social norms on pro-environmental behaviour, a cross-cultural approach. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, V.; Van Herpen, E.; Van Trijp, J.C.M. The influence of social norms in consumer decision making: A meta-analysis. Adv. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 463–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O.A.; Mahrous, A.A. Sustainable consumption behavior of energy and water-efficient products in a resource-constrained environment. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M.; Kenefick, J.; Schultz, P.W. Normative messages promoting energy conservation will be underestimated by experts … unless you show them the data. Soc. Influ. 2011, 6, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issock, P.B.I.; Roberts-Lombard, M.; Mpinganjira, M. Normative influence on household waste separation: The moderating effect of policy implementation and sociodemographic variables. Soc. Mark. Q. 2020, 26, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Social norms and cooperation in real-life social dilemmas. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Abrahamse, W.; Jones, K. Persuasive normative messages: The influence of injunctive and personal norms on using free plastic bags. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1829–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. The ethical consumer. Moral norms and packaging choice. J. Consum. Policy 1999, 22, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, E.-J.; Hur, W.-M. The normative social influence on eco-friendly consumer behavior: The moderating effect of environmental marketing claims. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 30, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivaara, L.; Lombardini, C.; Lankoski, L. Examining social norms among other motives for sustainable food choice: The promise of descriptive norms. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Snibbe, A.C.; Markus, H.R.; Suzuki, T. Is there any “free” choice? Self and dissonance in two cultures. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H.C. The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychol. Rev. 1989, 96, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Louis, W.R. Do as we say and as we do: The interplay of descriptive and injunctive group norms in the attitude–behaviour relationship. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 647–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafimow, D.; Triandis, H.C.; Goto, S.G. Some tests of the distinction between the private self and the collective self. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.W.; Lapinski, M.K. Cultural influences on the effects of social norm appeals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2024, 379, 20230036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Xia, X.J.; Betancor, V.; Rodríguez-Gómez, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A. Cultural variations in perceptions and reactions to social norm transgressions: A comparative study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1243955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Kim, M. Hofstede’s collectivistic values and sustainable growth of online group buying. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Nishii, L.H.; Raver, J.L. On the nature and importance of cultural tightness-looseness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.B.; Rice, R.E.; Gustafson, A.; Goldberg, M.H. Relationships among environmental attitudes, environmental efficacy, and pro-environmental behaviors across and within 11 countries. Environ. Behav. 2022, 54, 1063–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleeli, M.; Jawabri, A. The effect of environmental awareness on consumers’ attitudes and consumers’ intention to purchase environmentally friendly products: Evidence from United Arab Emirates. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyez, K. How national cultural values affect pro-environmental consumer behavior. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the world through GREEN-tinted glasses: Green consumption values and responses to environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer ‘attitude–behavioral intention’ gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingolla, C.; Hudders, L.; Cauberghe, V. Framing descriptive norms as self-benefit versus environmental benefit: Self-construal’s moderating impact in promoting smart energy devices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Brower, T.R. Longitudinal study of green marketing strategies that influence Millennials. J. Strateg. Mark. 2012, 20, 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).