Abstract

The article discusses the use of virtual reality (VR) as a tool for responsible tourism. Practical research was conducted in a group of 215 participants using VR headsets (Meta Quest Pro and HTC VIVE). Volunteers participated in a VR session using the Google Earth VR application. They visited two locations of their choice. The first was a place they had previously visited in real life, while the other was a location they had not visited but would like to. Participants completed a survey before and after the VR experience. In the survey, participants rated, among others, their level of satisfaction, willingness to visit given locations, and emotions accompanying the experience. The authors conducted a statistical analysis of the survey results. The scientific goal of the article was primarily to present a proposal for the use of virtual reality as an innovative tool supporting responsible tourism. The results confirmed a positive reception of VR experiences: average satisfaction ratings exceeded 4.0 on a 5-point scale, and positive emotions (most often +1 and +2 on a scale from −2 to +2) dominated among participants. Higher emotional valence was significantly correlated with satisfaction (ρ ≈ 0.434, p < 0.001) and with increased willingness to visit destinations (ρ ≈ 0.306, p < 0.001). Statistically significant differences were noticed in satisfaction level with visiting new places among groups of respondents with different tourism type preferences (people who prefer cultural or health tourism reported noticeably higher satisfaction with the VR experience than other respondents). The authors also conducted a discussion on how VR technology can be a tool supporting responsible tourism.

1. Introduction

Today, in the era of globalization, easy transportation, and growing travel options, the world is becoming increasingly borderless. New modes of transportation, low-cost airlines, and high-speed rail are making travel between countries and even continents increasingly easier and more accessible. At the same time, communication technologies—smartphones, video apps, social media, and video calls—allow people to meet people from many countries and discover distant cultures and customs without leaving home, fueling a desire for experiences, interactions, and real-life travel [1,2]. People want to experience more than just photos and videos, but also to visit monuments and see places in person—natural consequence of growing technological capabilities and mobility.

However, the increasing intensity of tourism is leading to new, serious environmental challenges. According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the number of international tourists in the first seven months of 2024 reached approximately 790 million—11% more than during the same period the previous year [3]. This has led to numerous negative consequences, such as increased CO2 emissions from transport [4,5,6], overuse and exploitation of natural and cultural resources [7,8], and degradation of the natural environment [9,10]. In the face of these challenges, there is an urgent need to find innovative solutions that will help steer tourism towards sustainable development and responsible one. Immersive technologies, such as virtual reality (VR), are becoming increasingly promising: they can reduce the need for physical travel to sensitive areas and offer alternatives to mass travel. VR allows visitors to explore places, monuments, and nature without traditional travel [11].

The authors of this article address the use of virtual reality in tourism for visiting places virtually. They propose VR to be used in tourism, as this industry should explore and develop innovative methods and tools within the framework of responsible tourism. Such solutions should be aimed at reducing the negative impact of tourism on the environment. As part of the study, the authors conducted a VR session using the Google Earth VR application for users visiting the chosen locations. Users also completed a two-part survey: before and after the VR experience.

Based on the literature review conducted by the authors (presented in Section 2 “Literature Review”), it can be concluded that existing research on responsible tourism has focused primarily on its theoretical assumptions and the analysis of the attitudes of tourists and local communities. However, there is a lack of studies presenting practical tools and technologies that could support the implementation of responsible tourism principles in practice. Furthermore, the authors noted, through their literature analysis, that few empirical studies examine the use of immersive technologies, such as virtual reality, as a tool supporting responsible travel and sustainable tourism development. Based on the results of the literature review, the authors identified a research gap. This research gap concerns the empirical verification of VR’s potential as a technology that can be used in practice as a tool for responsible tourism. In other words, there is a lack of studies in which respondents use VR to visit places and evaluate this technology in the context of practical use based on various criteria. This article fills this gap by presenting the results of experimental research involving VR users, which allows for the assessment of their satisfaction, emotions, and tourist intentions after virtual visits to selected destinations. The contribution of this work is both scientific and applied: first, it expands knowledge on the possibilities of using VR in the context of responsible tourism, and second, it provides insights into the practical use of VR in tourism.

The paper is divided into six sections. Section 2 includes a literature review, divided into four subsections that refer to the concept of responsible tourism, a review of practical research on responsible tourism, virtual reality in tourism, and the identified research gap. Section 3 presents materials and methods used in the research. Section 4 analyzes and interprets the results of the study (surveys and statistical analysis). Section 5 provides the scientific discussion, and Section 6 summarizes the paper with conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Responsible Tourism—The Concept

The responsible tourism concept has been discussed in the literature since the early eighties [12,13]. Responsible tourism is defined as a tourism management strategy in which the tourism sector and tourists take responsibility for protecting and preserving the natural environment, respecting and preserving local cultures and lifestyles, and contributing to strengthening local economies and improving the quality of life of local people [14]. The goal of responsible tourism is sustainable development. The concept is that individuals, organizations, and businesses must take responsibility for their actions and their impact. This responsibility rests with the government, owners, those responsible for products and services (including transportation), social services, industry associations, non-governmental and social organizations, as well as tourists and local communities. It is worth mentioning that responsible tourism can often be confused with sustainable tourism or even ecotourism [15]. In some papers, it can be read that responsible tourism is an application for sustainability with a practical operational-level difference [8,9].

Moreover, it must be noted that in literature and practice, there are many terms connected with sustainable tourism. They include alternative tourism [16], ecotourism [17], ethical tourism [18], green tourism [19], pro-poor tourism [20], geo tourism [21], integrated tourism [22], community-based tourism [23], smart tourism [24] etc. Responsible tourism is closely connected to these terms. According to Smith [12], this form of tourism respects the host’s natural, built and cultural environments and the interest of all parties concerned. It is worth referring to the critical remarks of Wheeler [25] who comments on the growing number of seemingly environment-friendly tourism initiatives and claims that responsible tourism cannot solve the problems of tourism, as long as the volume of global tourism increases. This necessarily has an increase in negative impacts and, taking it into account, responsible tourism requires limiting the scale and volume of tourism. According to this author [25], this form of tourism can be described as “a pleasant, agreeable, but dangerously superficial, ephemeral and inadequate escape route for the educated middle classes unable, or unwilling, to appreciate or accept their/our own destructive contribution to the international tourism maelstrom”. This means that while responsible tourism emphasizes the need for respect for the environment and local communities, it cannot be considered a universal solution to all the problems of mass tourism. The literature raises the question of to what extent this concept is a real tool for reducing the negative impacts of travel, or to what extent it is merely a declarative approach that remains insufficient without systemic change. This suggests that responsible tourism requires real solutions, not just slogans that will not actually minimize the negative impact of the tourism industry on the natural environment and cultural heritage. Moreover, according to Goodwin [26] responsible tourism is about everyone involved taking responsibility for making tourism more sustainable. However, calling everyone to take responsibility for everything can only serve to weaken this term, as it does not, in fact, provide or add any conceptual clarity.

To sum up, while the concept of responsible tourism is well-established in the literature, scholars emphasize that its interpretation varies and sometimes overlaps with related notions such as sustainable or ethical tourism. This conceptual ambiguity suggests the need for clearer operational frameworks and practical tools to implement responsible tourism in measurable ways.

2.2. Responsible Tourism—Review of Practical Research

There are many empirical studies and case studies in the literature that show how the concept of responsible tourism is implemented in practice. The first example is a case study by Chettiparamb and Kokkranikal [15]. The authors analyzed a local responsible tourism program aimed at increasing local communities’ participation in the benefits of tourism. Implementations included, among other things, the promotion of local products, support for small businesses, and the protection of cultural heritage. The study emphasized the importance of coordination between the public and private sectors for effective initiatives.

In South Africa, a study examining the challenges of implementing the concept of responsible tourism was conducted by Tichaawa and Samhere [27]. The authors used a stakeholder approach to survey hotels, travel agencies, and other tourism sector entities. The results showed that despite declarative support for the concept of responsible tourism, its practical implementation is limited by a lack of financial resources, low awareness, and insufficient institutional support.

The mentioned two research collectively indicate that while responsible tourism initiatives are being implemented in different contexts, their effectiveness largely depends on the level of institutional coordination and community participation.

Another example of research on the practical implementation of this concept is the article by Mathew and Sreejesh [28]. The authors conducted a survey in India, analyzing residents’ perceptions of responsible tourism initiatives in three destinations. The results showed that responsible tourism positively impacts residents’ perceptions of sustainability and quality of life, but its implementation faces financial and institutional barriers.

In Malaysia, responsible tourism practices were studied in the context of protected area protection [29]. The article analyzes the implementation of responsible tourism principles in Kinabalu National Park. The authors indicate that key practices include tourism management, educational activities, and the protection of local ecosystems. The study results demonstrate that such activities can effectively integrate sustainable development goals with tourism management practices when accompanied by local community engagement and appropriate regulations.

A study from Thailand also provides an example of regional implementation [30]. The authors described how a secondary tourist city implemented responsible tourism principles, including community integration, cultural promotion, training for industry professionals, and environmental protection. This study demonstrated that responsible tourism is more effective when incorporated into official tourism management plans and when it relies on cooperation between local authorities, businesses, and residents.

A common thread among the mentioned three studies is the emphasis on collaboration between public authorities, private stakeholders, and local communities. However, despite positive intentions, practical implementation is often hindered by limited financial resources and weak governance structures.

Another article, by Chan et al. [31], examined local community participation in responsible tourism practices in the Lower Kinabatangan area of Malaysia. Using mixed methods (surveys and focus groups among residents), the study analyzed barriers to implementing these practices (e.g., lack of capital, lack of knowledge, institutional constraints). According to the results, the local community recognizes the potential for sustainable tourism development and its economic benefits, but their actual participation in tourism activities and responsible tourism practices are limited. Key constraints include a lack of resources (financial, educational) and the lack of active involvement of external institutions. The authors recommend strengthening the knowledge and capabilities of local residents, supporting them in the development of tourism offerings, and incorporating them into decisions regarding tourism development.

Other researchers conducted a survey of 371 tourists in Vietnam [32]. They examined how the perception of a destination’s social responsibility directly and indirectly (through identification with the destination, reputation, and satisfaction) influences tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. The results indicate that the perception of a destination’s social responsibility has a positive impact on tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. Furthermore, increasing tourist identification with the destination, the destination’s reputation, and satisfaction influences the practical implementation of responsible tourism practices.

Aytekin et al. [33] conducted a survey among residents of the Manavgat region (Turkey). They analyzed the relationships between perceptions of responsible tourism, place attachment, and support for sustainable tourism development. They also examined the moderating role of residents’ environmental awareness. They found that positive perceptions of responsible tourism by residents increased their emotional attachment to the place; stronger attachment fostered support for sustainable tourism development; and environmental awareness strengthened these relationships as a moderating factor.

Taken together the mentioned last three papers, the findings show that although residents and tourists tend to support responsible tourism in principle, its success depends on awareness, education, and the provision of concrete mechanisms that allow communities to benefit from tourism in practice.

Based on the research cited, it can be concluded that the concept of responsible tourism is finding increasing practical application, yet its implementation faces numerous limitations. Analytical findings indicate that responsible tourism can truly support the sustainable development of destinations, improve residents’ quality of life, and strengthen their attachment to a place, provided it is accompanied by active engagement of local communities, appropriate regulations, and collaboration with various stakeholders. At the same time, research shows that barriers remain: a lack of financial and educational resources, low awareness among tourists and entrepreneurs, and insufficient institutional support. This means that while responsible tourism has significant potential, it requires complementation with specific tools and innovative solutions that will enable more effective implementation of its principles in practice. Overall, the reviewed literature highlights both the potential and the limitations of responsible tourism practices, revealing the need for innovative, technology-based tools that can enhance their real-world implementation.

2.3. Virtual Reality in Tourism

One of the newer tools with potential for use in tourism is virtual reality. It can be applied in various areas of tourism. Literature research indicates a few areas in which VR can play a significant role.

The first area is the virtual watching of individual works of art, or even parts of museums or cultural heritage sites. VR enables the creation of virtual tours, historical reconstructions, and interactive exhibitions—for instance Viking VR [34]. This allows tourists to virtually visit specific sites. The literature shows many examples of research on visiting museums in VR, for example [35]. Papers discuss virtual experiences [34,36,37], effects of such visits [38], developing VR museums [39], building exhibitions in VR [40], usability evaluation living museums [41] and more. What is more, there are research on cultural heritage and VR experience, discussing the need for such applications [42], the virtual experience [43,44], 3D visualization of artefacts [45], accessibility of cultural heritage [46,47], and more. In VR, virtual visitors can see Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa [48,49], Van Gogh’s Starry Night [50], or Pablo Picasso’s Guernica [51]. These studies show that VR applications are not limited to entertainment but can significantly enhance cultural accessibility and engagement, allowing users to experience art and heritage in new, immersive ways.

VR can be used to visit specific places around the world, such as a city where a future trip is planned. According to Stecuła and Naramski [11], simulations and immersive experiences allow potential tourists to familiarize themselves with a destination before traveling or revisit a place they have already visited, choosing from spots all over the world. Such tools can reduce uncertainty and psychological barriers associated with choosing new, unfamiliar destinations. According to other research findings [52] telepresence (realism, immersion, a sense of being present) significantly influences the creation of mental images of destinations and fosters positive intentions to visit. Therefore, VR can act as a stimulus for actual travel—at least in intention. Other authors [53] note that high-quality content and systems, as well as a realistic experience, increase immersion and enjoyment, which in turn strongly influences intentions to visit specific places. In these contexts, it can be said that VR can be a marketing tool. Some results confirm that VR can be an important element of marketing strategies [54]. Literature proves that VR is effective as a tool for tourism marketing and destination promotion [53,55,56,57]. Some authors developed a guide to the application of virtual reality marketing with its social implications as a disconnection to tourism networks [58]. Collectively, this part of research highlights VR’s strong potential as a persuasive and experiential marketing tool, yet few studies connect this potential to sustainability or responsible travel behaviors.

Another area of VR application is nature tourism and protected areas. VR can provide experiences of contact with nature—for example, national parks [59,60] or coral reefs [61]—without the risk of environmental degradation. Such solutions are particularly important in the context of sustainable development and responsible tourism, where minimizing tourist pressure on sensitive ecosystems is a priority.

Education and awareness-raising among tourists are also important areas. VR allows for interactive presentations on environmental protection, local culture, and responsible travel behavior. Its immersive nature makes the message highly engaging and effective. VR can stimulate the emotion of awe which in turn influences the adoption of pro-environmental attitudes in the context of cultural heritage. A study by Zhu et al. [62] found that in VR tourism experiences involving heritage sites, perceived ease of use (PEU) and perceived usefulness (PUS) have a positive impact on the emotional state of awe and attitudes toward pro-sustainable behavior. Another study demonstrated that VR has potential as a tool supporting sustainable tourism policies [63]. In the case of a virtual tour of the Pahlavon Mahmud Mausoleum in Khiva, respondents rated the experience as acceptable and valuable from the perspective of protecting cultural sites and the natural environment. Some other study highlights that VR can be used for museum education [64], as well as it has also been shown to foster interest in art [65]. These findings suggest that VR may serve as a bridge between education and emotional engagement, transforming environmental knowledge into affective experiences that promote responsible behavior.

The literature also highlights the use of VR in destination management and spatial and urban planning processes [66]. Local authorities and tourism managers can use VR simulations to test various scenarios for the development of tourism spaces, forecast traffic flow, and assess the impact of new investments on the surrounding area. For example, in some study [67], the authors used VR so that residents could compare two options for renovating a historic district and express their preferences, facilitating spatial planning and integrating cultural heritage. In another case [68], researchers from Romania created an online portal with 3D models and panoramic VR images, allowing for virtual tours of wooden churches, which helps protect these structures and facilitates access and planning for conservation measures. There is also study on innovating the cultural heritage museum service model through VR [69].

The importance of VR for people with limited mobility cannot be overlooked, as it provides an alternative form of participation in tourism and culture. In this way, VR supports the concept of inclusive tourism and expands access to tourism experiences for previously excluded groups. Researchers have created a VR experience that allows wheelchair users to immersively explore the archaeological site of Cancho Roano in Spain [70]. Using 3D models acquired through laser scanning, users can virtually “walk” through an area that may be difficult for people with limited mobility to access in real life. A study in nursing homes in which elderly residents participated in VR sessions three times a week for six weeks [71]. Participants reported reduced anxiety and fatigue, and increased social engagement and quality of life. This demonstrates that VR can be a way to participate in tourism (virtual tourism) for people who cannot physically travel due to mobility or health limitations. Another project investigated how 3D virtual tours help people with limited mobility assess the accessibility of unfamiliar places—for example, entering buildings and checking for architectural obstacles [72]. This allows them to plan their visits in advance, reducing the uncertainty and stress associated with physical barriers. This field of research highlights the inclusive nature of VR. It demonstrates that immersive technologies can facilitate and enhance access to culture and tourism for people with physical, cognitive, or other disabilities.

Additionally, it is worth mentioning that there are also papers on the metaverse in the context of tourism. This topic is another step (big step) when it comes to virtual reality. Al-kfairy [73] in the paper examines the factors influencing users’ intentions to adopt virtual reality technologies in museums. In the paper of Yang and Wang [74], the authors analyze the past, present, and future of the metaverse with a focus on the tourism domain. In another paper [75], it has been shown that the metaverse influenced experiences in hospitality and tourism in four ways: an immersive trial that reduce the uncertainty of experience; a spatial and temporal change with an immersive experience; a blended travel fusion of digital virtuality and physical reality; and a blurred boundary of before, during and after trip experience journey. According to Chen [76], metaverse technology can enhance the tourist experience through personalized options, social interaction, immersive experiences and feedback. Summing up, the literature review indicates that VR in tourism serves promotional and marketing functions, as well as educational, protective, managerial, and social functions. Although this technology is still being developed, research indicates that VR can become a key tool for innovation in tourism, supporting its sustainable and responsible development. Table 1 summarizes the literature review on VR in tourism.

Table 1.

Summarization of the thematic categorization of studies on the use of VR in tourism.

2.4. Virtual Reality and Responsible Tourism—The Research Gap

An analysis of research indicates that both the concept of responsible tourism and the use of virtual reality in tourism are discussed in the literature, but they typically constitute two distinct research streams. Many publications focus on the theoretical aspects of responsible tourism, analyzing its assumptions, challenges, and best implementation practices, while empirical research on practical tools supporting the implementation of its principles remains limited.

Research on VR in tourism, on the other hand, focuses primarily on marketing, educational, and promotional applications, analyzing the impact of immersive experiences on traveler satisfaction, interest, and intentions. Although the potential of VR in the context of sustainable development is increasingly emphasized, there is a lack of work that clearly connects this technology with the concept of responsible tourism. Critical voices regarding responsible tourism are also worth mentioning: some scholars emphasize that the concept is often theoretical and lacks practical relevance. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is a need to develop and implement practical tools that will help implement the idea of responsible tourism—and virtual reality offers just such a solution. In other words, real tools and technologies are needed, not just declarations. Few studies examine VR as a practical tool for implementing responsible tourism. The literature also lacks empirical studies examining VR user experiences in the context of satisfaction, emotions, and tourist intentions in connection with the concept of responsible tourism. The latest published literature reviews also confirm the gap in the field of virtual reality and emotions. Linares-Vargas’s and Cieza-Mostacero’s [77] indicate methodological and empirical gaps in the topic of emotions in VR; Mariana Magalhães et al. [78] emphasize the lack of reliable empirical research on emotions; Mancuso et al. [79] indicate the need for further empirical research on emotions in VR, including in tourism.

Despite the growing popularity of the concept of responsible tourism, its practical implementation faces a number of challenges described in the literature, including a lack of effective monitoring tools, insufficient tourist education, limited stakeholder collaboration, and difficulty changing traveler behavior. These barriers indicate that traditional approaches are insufficient to translate the concept of responsibility into everyday tourism practice. Therefore, innovative technological tools are needed to make responsible tourism more tangible and engaging. Virtual reality can address these challenges by combining education, emotional engagement, and accessibility, thus enabling responsible experiences of destinations while reducing environmental impact.

The identified research gap therefore points to the need to integrate both perspectives—technological and responsible—to develop innovative solutions supporting sustainable tourism development. Such research can contribute to a better understanding of how VR can truly support the implementation of responsible tourism principles, serving as a practical educational, protective, and inclusive tool.

The study adopted an approach based on one of many theories explaining the process of accepting new technologies. Reference was made to Davis’s Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [80], which posits that acceptance and positive attitudes toward new technology depend primarily on its Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU). In the context of this study, these factors are crucial for assessing whether users perceive virtual reality as a tool supporting responsible tourism and whether they find the VR experience satisfying and intuitive. This theoretical approach is justified because the study focuses on assessing users’ perceptions, emotions, and intentions in response to exposure to new technology—thus directly addressing the processes of technology acceptance and innovation adoption. It is worth noting that the literature contains articles that utilize or expand upon TAM assumptions in the context of virtual reality and tourism. An et al. [81] analyze how Perceived Information Quality and the experience of immersion (Flow) influence visit intention. The model is based on the TAM constructs (PU) and (PEOU), which provide a foundation for understanding why users accept virtual tourism experiences. Ying et al. [82] use classic TAM elements, and the theoretical model examines the impact of telepresence (sense of presence) and social presence on perceived VR usefulness and visit intention (Behavioral Intention). Another paper [83] is not based directly on TAM, but on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model—a different concept of user behavior, but very often treated in the literature as an extension of TAM. Thus, TAM and its extensions offer a relevant framework for explaining users’ responses and intentions toward the use of virtual reality in responsible tourism.

3. Materials and Methods

The study was carried out between late March and the end of June 2025 among 215 respondents recruited at the Faculty of Organization and Management, including both students (full-time and part-time) and academic staff. The analyses presented in this paper focus on a subset of the project devoted to willingness to visit or revisit destinations, satisfaction with the VR experience, and affective responses.

The target population consisted of potential and active users of immersive technologies interested in tourism experiences, represented by students and academic staff of the Faculty of Organization and Management at the Silesian University of Technology. The sample was obtained through a convenience sampling approach, as participation was voluntary and limited to individuals available during scheduled research sessions.

The main scientific objective (Os) of the conducted study was formulated as follows:

- Os: Presenting a proposal for the use of virtual reality as an innovative tool supporting responsible tourism.

In order to achieve the main objective, five utilitarian objectives (Ou) were set:

- Ou1: Conducting experimental studies using VR headsets with user participation.

- Ou2: Assessing satisfaction with using VR to visit selected destinations.

- Ou3: Analyzing the impact of VR on tourist intentions.

- Ou4: Identifying individual factors that differentiate the evaluation of the VR experience for visiting destinations.

- Ou5: Assessing the role of emotions in the VR experience and their relationship with satisfaction and tourist intentions.

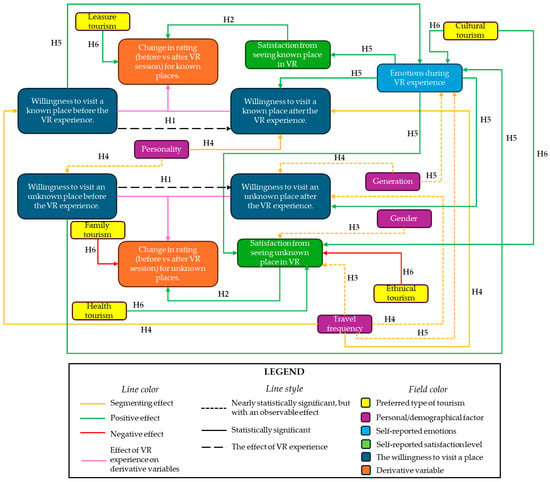

Based on the presented research objectives, six hypotheses were formulated:

H1.

VR exposure changes willingness-to-visit destinations; willingness-to-visit pre-VR differs from willingness-to-visit post-VR (for both previously visited and previously unseen destinations).

H2.

Higher satisfaction with the VR experience is associated with a greater increase in willingness-to-visit (Δ = post-VR minus pre-VR).

H3.

Individual characteristics (gender, generation, education, personality type, VR use frequency, travel frequency, headset type) significantly differentiate satisfaction (for previously visited and previously unseen destinations).

H4.

Individual characteristics (gender, generation, education, personality type, VR use frequency, travel frequency, headset type) significantly differentiate willingness-to-visit (pre-VR, post-VR).

H5.

Emotion valence experienced during VR is positively associated with satisfaction and willingness-to-visit (pre-VR, post-VR, Δ).

H6.

Tourist preferences (declared preferred types of tourism) significantly differentiate emotion valence and satisfaction (for previously visited and previously unseen destinations).

To ensure adequate statistical power across all key analyses, three a priori power analyses were conducted in G*Power 3.1:

- First, for within-subject comparisons using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-tailed, medium effect size dz = 0.5, α = 0.05, power = 0.95), the required sample size was 57 participants.

- Second, for correlation analyses between ordinal variables (e.g., satisfaction, emotions, willingness), assuming a bivariate normal model with ρ = 0.3, α = 0.05, and power = 0.95, the required sample size was 138 participants.

- Third, for group comparisons using a nonparametric equivalent of one-way ANOVA (e.g., Kruskal–Wallis tests with five groups), a power analysis based on an F test (effect size f = 0.25, α = 0.10, power = 0.90) indicated a required sample size of approximately 215 participants.

The final sample of N = 215 therefore exceeded or matched the required thresholds for all planned analyses, ensuring high statistical power and robustness of the results. As mentioned before, the sample was limited to university students and academic staff from a single faculty. This convenience sampling approach constrains the external generalizability of the findings to wider tourism populations and should therefore be interpreted as exploratory. Nevertheless, the study serves as a first step toward validating VR-based assessments of travel-related attitudes and will be extended in future research to more diverse, non-academic samples. Although the data were collected within a single faculty, the participant pool included individuals from multiple study programs (e.g., logistics, management and production engineering, cognitive technologies, and business analytics), which contributed to internal variability in attitudes, technology familiarity, and tourism orientations.

The research design consisted of three stages: a pre-VR questionnaire, a single VR session, and a post-VR questionnaire. In the pre-VR stage, participants provided socio-demographic information (gender, generational cohort, education level), declared their self-perceived personality type (introvert, ambivert, extravert), frequency of VR use, headset familiarity, and travel frequency. They also indicated preferred forms of tourism (e.g., cultural, health, leisure, family, adventure, weekend, landscape, city). Finally, each respondent named two destinations: one previously visited that they would like to revisit, and one unknown location they would like to see. For both destinations they rated their willingness to (re)visit on a five-point Likert scale (1 = no willingness, 5 = very strong willingness).

The VR session lasted about 10 min and involved exploring the two chosen destinations in Google Earth VR, using either HTC Vive or Meta Quest Pro. Immediately afterwards, participants completed the post-VR questionnaire. They again rated their willingness to (re)visit the two destinations, this time allowing for the calculation of individual change scores (post minus pre). They also assessed satisfaction with the VR experience separately for the “new place” and the “visited place” (5-point scale), and reported the emotions experienced during VR on a bipolar scale ranging from −2 (very negative) to +2 (very positive).

For the purposes of analysis, willingness was therefore represented by four variables (want to visit pre and post, revisit pre and post) and by two difference scores (Δ want, Δ return). Satisfaction was assessed for both types of destinations, while emotion was treated as a single ordinal variable. In addition, binary indicators were created for each declared type of tourism preference to enable comparison between those who selected a category and those who did not.

Because the variables were ordinal and distributions showed many ties, all analyses relied on non-parametric methods. Pre- and post-VR comparisons of willingness were tested using Wilcoxon [84] signed-rank tests for paired data. Differences between the “want to visit” and “revisit” constructs, both before and after VR, were likewise tested with Wilcoxon procedures. Kruskal–Wallis [85] rank-sum tests were applied to examine group differences in satisfaction and willingness across gender, generation, education, personality, VR use, headset type, travel frequency, and tourism preferences. Where omnibus significance was found, post-hoc Dunn [86] tests with Bonferroni [87] correction were used to identify the source of differences, for example between generational cohorts or travel frequency groups. Associations between ordinal measures, such as emotions and satisfaction or willingness, were assessed using Spearman’s [85,88] rank correlation coefficient. Because of ties, exact p-values were not available and large-sample approximations were reported, as indicated by the software.

All measures used in the present analyses are summarized in Table 2. They include pre- and post-exposure ratings of travel intentions (for both previously visited and unknown destinations), post-exposure satisfaction and emotions, as well as demographic and individual characteristics such as gender, generation, education, personality, VR experience, travel frequency, and declared tourism preferences. For each variable, the table specifies its operationalization, coding, measurement scale, and the moment in which it was collected. All constructs were measured using single-item indicators developed by the authors specifically for the context of VR-based tourism experiences. Therefore, internal consistency measures (Cronbach’s α or composite reliability) are not applicable, as these indices require at least two items per construct. Single-item measures were used intentionally due to the specific and concrete nature of the constructs (e.g., satisfaction, emotional valence, visit intention) and the need to minimize participant burden and cognitive fatigue in a short, immersive VR experiment involving repeated pre–post assessments. Because the constructs of interest (e.g., satisfaction, emotional valence, visit intention) were concrete and unambiguous, each was operationalized as a single item. The wording of all measurement indicators is presented within the variable descriptions.

Table 2.

Measures and coding of variables used in the analyses.

Results were presented visually using histograms (for change scores), boxplots (for group comparisons), and bar plots (for tourism preferences). Multi-panel figures combined related analyses to facilitate interpretation. In addition, maps and word clouds were generated to illustrate the geographical distribution and diversity of destinations selected by respondents.

The measures presented in Table 2 were used to test the previously formulated hypotheses and, in consequence, achieve the utilitarian research aims. Table 3 presents an operational mapping between the aims, hypotheses, key variables, and statistical tests, ensuring direct traceability between the conceptual specification introduced in the Introduction and the analytical procedures reported in the Results

Table 3.

Mapping of study aims (A1–A5) to hypotheses (H1–H6), key variables, and primary statistical tests.

All tests were two-sided with a significance level of α = 0.05. Multiple testing was addressed by applying Bonferroni corrections within each family of post-hoc contrasts, although no global adjustment was introduced; results are therefore treated as exploratory. Unequal group sizes meant that some subgroups—such as Generation X (11 cases) or “other/prefer not to say” in the gender item—were small, and findings for these categories are interpreted with caution.

Analyses were performed in R [89], using the tidyverse [90] for data wrangling, ggplot2 [91] for visualization, FSA [92] for Dunn’s tests, base stats for Wilcoxon, Kruskal–Wallis and Spearman procedures, and patchwork [93] for multi-panel layouts.

4. Results

4.1. Selection of Places

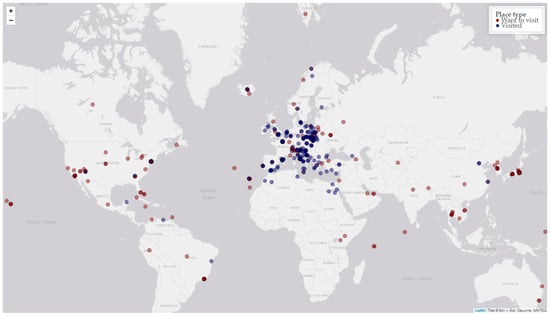

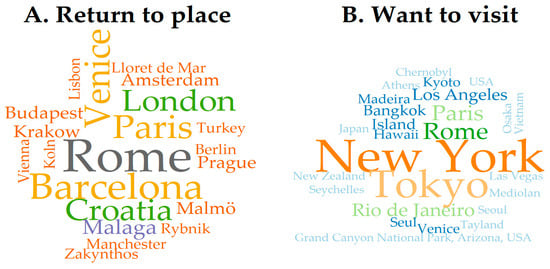

Before the VR experience, participants were asked to indicate two destinations: one they had previously visited in real life and would like to revisit, and one they had not yet visited but would like to explore. It should be noted that participants were aware they would take part in an experiment involving VR technology and were likely to virtually visit these destinations. This awareness may have influenced their choices. Figure 1 presents a map with the locations identified by the respondents, while Figure 2 illustrates word clouds of the most frequently selected destinations (each mentioned by at least two participants).

Figure 1.

Global distribution of destinations selected by participants for the VR experience. Navy dots represent locations previously visited in real life, while crimson dots indicate destinations respondents wished to visit. The map is based on self-reported choices from 215 participants [11].

Figure 2.

Word clouds of destinations most frequently selected by participants. Panel (A) shows places respondents had previously visited and wished to revisit, while Panel (B) shows destinations they had never visited but wanted to explore. Only places mentioned by at least two participants are displayed.

Figure 1 visualizes the spatial distribution of all indicated destinations on a world map, divided into places already visited and places participants wished to visit. The map reveals a strong concentration of revisited destinations in Europe, reflecting geographical proximity and established travel patterns within the sample. By contrast, aspirational destinations are more globally dispersed, spanning North America, Asia, and Oceania. This pattern suggests that VR was perceived as an opportunity to explore remote and less accessible locations. The spatial contrast highlights the potential of VR applications in responsible tourism: providing immersive access to culturally and geographically distant sites while reducing the environmental costs of long-haul travel. Such applications can serve both as an educational tool and as a means of encouraging more sustainable travel behavior.

Figure 2A shows places previously visited by respondents that they would like to revisit, while Figure 2B illustrates destinations they had not yet experienced but wished to visit. In both cases, a relatively small number of cities dominate the responses. Among revisited places, European destinations such as Rome, Barcelona, London, and Paris are most prominent. Desired but not yet visited destinations are more globally distributed, with New York and Tokyo standing out as the most frequently indicated, followed by Rio de Janeiro, Los Angeles, and Bangkok. This contrast points to a tendency to revisit culturally and geographically proximate European cities, while aspirations for new experiences extend to distant, global metropolises. The distinction between revisited and new destinations provides insights into different motivational drivers of tourism demand. While revisited cities reflect the importance of cultural familiarity and accessibility, the choice of long-haul destinations indicates aspirational travel goals. In the context of responsible and smart tourism, these findings underline the potential of VR to satisfy curiosity about distant destinations in a sustainable manner—offering virtual exploration as a complement, or in some cases an alternative, to physical long-haul travel.

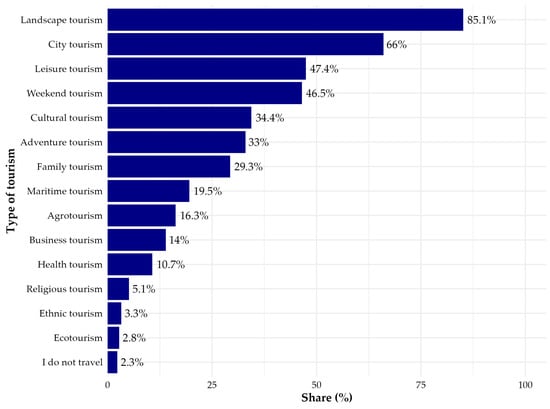

Interestingly, the results indicate that both in the case of destinations participants wished to visit for the first time and those they wanted to revisit, large cities (such as Tokyo, Rome, or New York) were most frequently mentioned. However, in the initial part of the survey, when respondents were asked to indicate their preferred types of tourism, city tourism was not the most common answer. Figure 3 presents the distribution of preferred forms of tourism among participants.

Figure 3.

Distribution of respondents’ preferred forms of tourism.

As shown in Figure 3, the most frequently selected type was landscape tourism (85.1%), followed by city tourism (66%). Almost half of the respondents also indicated leisure tourism (47.4%) and weekend tourism (46.5%). Among the least popular categories were religious tourism (5.1%), ethnic tourism (3.3%), and ecotourism (2.8%). A small number of participants declared no travel (2.3%). Although respondents declared the strongest preference for landscape tourism, the destinations they most frequently named were large urban centers. This discrepancy suggests that while travelers value nature-oriented and sustainable forms of tourism in the abstract, iconic global cities dominate when concrete destinations are considered.

For the purposes of responsible and smart tourism, VR could play a dual role. On the one hand, it can provide immersive experiences of distant metropolitan icons (e.g., Tokyo, New York, Rome) in a way that reduces the environmental costs associated with long-haul urban travel. On the other, it can be used to enhance interest in landscape and nature-based tourism, supporting more sustainable, local, or regional travel choices that align with participants’ stated preferences.

In this way, VR emerges as an innovative tool bridging the gap between aspirational global travel and responsible tourism practices, complementing physical trips while helping to shape more sustainable patterns of tourist behavior.

4.2. Willingness to Visit a Destination Before and After VR Experiences

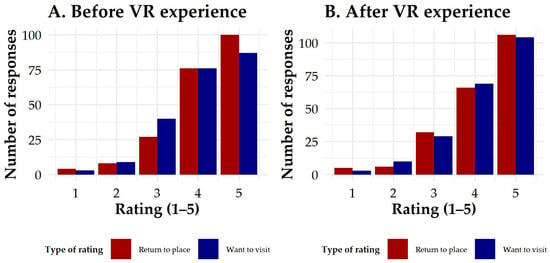

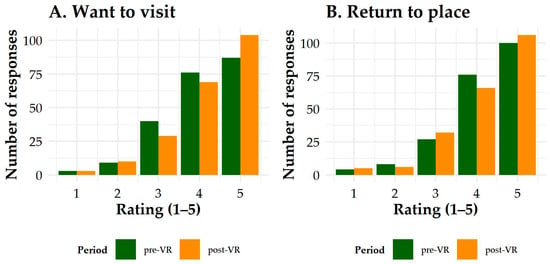

Respondents were asked both before and after the VR experience to evaluate their willingness to visit the indicated destinations—both those previously visited in real life and those not yet experienced—using a five-point Likert scale (where 1 indicated no willingness and 5 indicated very high willingness). Figure 4 presents the distribution of these ratings: Figure 4A shows the comparison between “want to visit” and “return to place” before VR, while Figure 4B illustrates the same comparison after VR. In addition, Figure 5 compares pre- and post-VR ratings separately for each category: Figure 5A shows scores for destinations respondents had previously visited and wished to revisit, while Figure 5B shows scores for places they had not visited before in reality.

Figure 4.

Distribution of willingness-to-visit ratings before and after the VR experience. Panel (A) shows the responses before the VR experience, while Panel (B) shows the responses afterward. Ratings are grouped by destination type: previously visited (dark red) or never visited before (navy).

Figure 5.

Comparison of pre- and post-VR ratings for destinations never visited before Panel (A) and previously visited ones Panel (B).

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied to assess paired differences, and the results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for paired comparisons of tourism intention ratings.

No statistically significant differences were observed between pre- and post-VR scores for either the intention to visit new destinations (V = 2495, p = 0.082, r = 0.16) or the willingness to return to previously visited places (V = 2147.5, p = 0.734). Similarly, comparisons between the two destination types did not reveal significant differences, either before VR (V = 3700, p = 0.102, r = 0.136) or after VR (V = 2259.5, p = 0.938, r = 0.008). Taken together, these findings indicate that the VR experience did not produce statistically significant shifts in participants’ ratings, although a weak trend was observed toward higher post-VR ratings for new destinations.

An important limitation of this study is that participants themselves selected the destinations they had not previously visited but wished to explore. This self-selection may have biased the results, as respondents were already interested in those places, leaving less room for VR to alter their evaluations. Future research could address this issue by including randomly selected destinations—unfamiliar to participants—and measuring changes in their perceived attractiveness before and after VR exposure. Such a design could better capture VR’s potential to stimulate interest in locations that might not initially be considered attractive, thereby highlighting its value as an innovative tool for destination promotion.

The analysis indicates that the VR experience did not significantly alter participants’ willingness to visit or revisit destinations. This stability suggests that individuals’ core travel preferences and intentions are relatively robust, even when exposed to immersive VR simulations. From the perspective of responsible and smart tourism, such findings are valuable: VR may not necessarily override established travel motivations but can reinforce and complement them.

Although the trend toward higher post-VR ratings for new destinations was not statistically significant, it suggests that VR may have the potential to stimulate additional interest in aspirational travel, particularly to distant locations. This raises important questions about VR’s role in responsible tourism: while it could encourage environmentally costly long-haul travel, it also offers opportunities to act as a substitute or complement, providing meaningful experiences of distant places without physical displacement. At the same time, the stability observed in “return to place” ratings points to VR’s usefulness as a tool for sustainable destination management, enabling repeated engagement with familiar sites while limiting the environmental burden of repeated travel.

In summary, the Wilcoxon tests indicated no significant pre–post differences in willingness to visit both previously visited and never-visited destinations. Only weak, non-significant upward tendencies were observable. Because pre-VR intentions were already very high, ceiling effects likely limited the detectable room for improvement. Thus, H1 (VR exposure changes willingness-to-visit destinations; willingness-to-visit pre-VR differs from willingness-to-visit post-VR (for both previously visited and previously unseen destinations)) was not supported. Rather than drawing final conclusions at this stage, these results highlight the need for a closer look at individual-level differences. In the next section, we therefore analyze how participants’ ratings changed before and after VR exposure and examine whether these differences were related to the level of satisfaction with the VR experience (Section 4.3).

4.3. Differences in Ratings and Their Relationship with VR Satisfaction

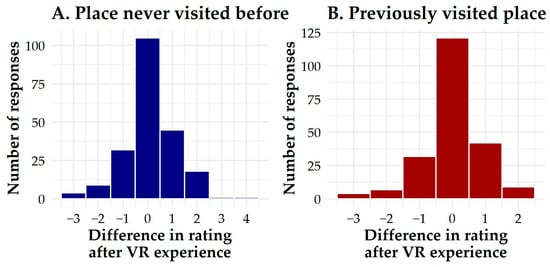

To further investigate the potential impact of VR on participants’ evaluations, we calculated the difference between post- and pre-VR ratings for both categories of destinations: places previously visited and places not yet experienced. Figure 6A,B present the distributions of these individual-level differences. The majority of participants reported no change (difference = 0), while a substantial number indicated small positive shifts (+1 or +2), and only a few reported decreases. These histograms reinforce the results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, showing overall stability in willingness-to-visit ratings, but they also highlight heterogeneity in individual responses to VR exposure.

Figure 6.

Distributions of individual-level differences in willingness-to-visit ratings (post–pre VR). Panel (A)—change in willingness to visit places never visited before. Panel (B)—change in willingness to revisit previously visited places. Positive values indicate increased interest after the VR experience.

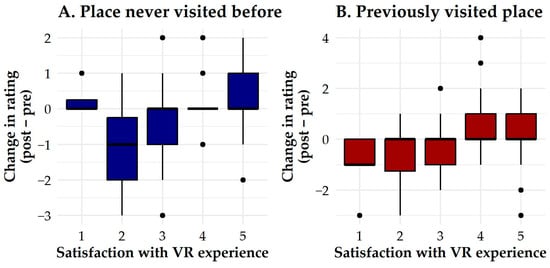

In addition to rating destinations, participants evaluated their satisfaction with the VR experience using a five-point Likert scale (1 = not satisfying at all, 3 = neutral, 5 = very satisfying). This allowed us to test whether satisfaction was associated with changes in willingness-to-visit ratings. Spearman’s rank correlations revealed significant positive associations: higher satisfaction was linked to greater increases in the intention to visit new destinations (ρ = 0.306, p < 0.001) and in the willingness to return to previously visited places (ρ = 0.297, p < 0.001). Consistently, Kruskal–Wallis tests confirmed significant differences in rating changes across satisfaction levels (χ2 = 31.66, df = 4, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.132 for new destinations; χ2 = 25.37, df = 4, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.102 for revisited places). The effect sizes can be interpreted as medium according to conventional benchmarks [94,95] (0.06 < η2 < 0.14). To further illustrate these effects, Figure 7 presents boxplots of rating differences by satisfaction levels. The plots show that participants reporting low satisfaction with the VR experience (scores 1–2) most often exhibited no change or even decreases in their ratings, whereas those with higher satisfaction (scores 4–5) more frequently reported positive differences. This pattern is consistent across both categories: willingness to return (Figure 7A) and willingness to visit new destinations (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Boxplots of rating differences (post–VR rating minus pre–VR rating) by satisfaction with the VR experience: Panel (A)—willingness to visit new destinations; Panel (B)—willingness to return.

Taken together, these findings suggest that although VR exposure did not uniformly alter intentions across the entire sample, its impact was moderated by the level of satisfaction with the experience. Participants who found the VR experience more satisfying were more likely to increase their willingness to visit destinations, underlining the importance of user experience quality in leveraging VR for tourism applications. In other words change scores differed significantly across satisfaction levels, and satisfaction correlated positively with post-VR intention levels. Thus, H2 (Higher satisfaction with the VR experience is associated with a greater increase in willingness-to-visit (Δ = post-VR minus pre-VR)) was supported.

4.4. Determinants of Satisfaction with the VR Experience

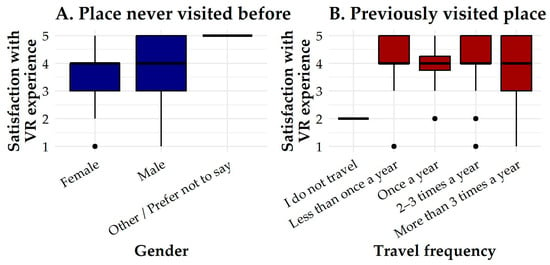

To explore which factors may explain satisfaction with the VR experience, non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted separately for satisfaction with visiting a previously unknown place (that the participant wished to see) and satisfaction with revisiting a place already known from real life. Independent variables included socio-demographic characteristics (gender, generation, education), personality, frequency of VR use, type of headset, and frequency of travel.

The results indicate that no variable significantly differentiated satisfaction at the conventional 0.05 level. For satisfaction with visiting a previously unknown place, the closest to statistical significance was frequency of travel (χ2 = 8.45, df = 4, p = 0.076, η2 = 0.021). Gender also showed a weaker, but observable tendency (χ2 = 3.275, df = 2, p = 0.194, η2 = 0.006). For satisfaction with revisiting a known place, no individual characteristic approached significance (all p > 0.2). All other variables — including generation, education, personality, VR use, and headset type — did not reveal meaningful effects. To illustrate these tendencies, Figure 8 presents satisfaction levels across the two contexts. Figure 8A (gender) shows that male participants reported slightly higher median satisfaction with visiting a previously unknown place, but also displayed a much broader range of evaluations, from very low to very high. Female participants, in contrast, tended to provide more consistent ratings clustered around moderate values, while those identifying as “other” or preferring not to specify gender consistently reported high satisfaction. Figure 8B (travel frequency) indicates that individuals who traveled more often (two to three times per year or more than three times per year) generally expressed higher satisfaction with revisiting a known place. At the same time, this group exhibited the greatest variability in scores, suggesting that frequent travelers may hold stronger and more diverse expectations of VR. Conversely, those who reported little or no travel activity tended to rate their satisfaction lower, with limited variability.

Figure 8.

Satisfaction with the VR experience: Panel (A)—satisfaction with visiting a place never visited before by gender; Panel (B)—satisfaction with revisiting a previously visited place by travel frequency.

Taken together, these descriptive patterns align with the near-significant statistical results: gender differences appear more relevant in the case of previously unknown places, while travel frequency seems to matter more for familiar destinations. Although the observed effects fall short of statistical significance, they highlight potentially meaningful relationships that could emerge more clearly in larger and more diverse samples. Further research should therefore examine the role of gender and travel activity in shaping satisfaction with VR experiences, as these factors may condition how immersive technologies are received in tourism contexts. Nevertheless, no factor showed statistically significant effects at α = 0.05. The closest tendencies were for travel frequency and gender in satisfaction with never-visited places, but these did not reach significance after correction. Thus, H3 (Individual characteristics (gender, generation, education, personality type, VR use frequency, travel frequency, headset type) significantly differentiate satisfaction (for previously visited and previously unseen destinations).) was not supported.

4.5. Determinants of Willingness-to-Visit Ratings

Furthermore, we examined whether socio-demographic factors (gender, generation, education), personality traits, VR-related variables (frequency of VR use, type of headset), and travel frequency influenced participants’ ratings of willingness to visit new destinations or to return to previously visited places, both before and after the VR experience. Non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied to all four measures (want.visit.score, want.visit.score2, was.score, was.score2).

The results indicate several noteworthy associations. For willingness to visit new destinations before VR, no factor reached conventional significance, although personality showed a near-significant effect (χ2 = 5.74, df = 2, p = 0.057, η2 = 0.018). For willingness to visit new destinations after VR, two factors approached or reached significance: generation (χ2 = 11.62, df = 2, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.045) and travel frequency (χ2 = 9.21, df = 4, p = 0.056, η2 = 0.025). For willingness to return to previously visited places before VR, travel frequency was significant (χ2 = 14.03, df = 4, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.048). After VR, two factors emerged as significant: personality (χ2 = 6.56, df = 2, p = 0.038, η2 = 0.022) and travel frequency (χ2 = 25.49, df = 4, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.102). The corresponding effect sizes (η2 = 0.02–0.10) indicate small-to-moderate practical effects, suggesting that generation, personality, and travel frequency modestly influenced the impact of VR on tourism intentions.

Post-hoc Dunn tests provided more detail on where these differences occurred:

- Generation—Participants from Generation Y reported significantly higher willingness to visit new destinations after VR compared to both Generation X (p = 0.021, z = 2.698, r = 0.184) and Generation Z (p = 0.004, z = −3.204, r = 0.219). No significant differences were observed between Generations X and Z.

- Travel frequency—For willingness to return to a visited place, which was rated before VR experience, differences emerged mainly between participants traveling less than once a year and those traveling more than three times per year (p = 0.017, z = −3.135, r = 0.214), with the latter giving higher ratings. After VR experience, several comparisons reached significance: respondents traveling two to three times per year reported higher willingness to return compared to those traveling less than once a year (p = 0.041, z = 2.867) or once a year (p = 0.010, z = 3.299). Likewise, participants traveling more than three times per year differed significantly from the less-than-once-a-year group (p = 0.049, z = −2.811, r = 0.196) and from the once-a-year group (p = 0.016, z = 3.163, r = 0.216), again with frequent travelers expressing higher willingness to return.

- Personality—After VR experience, extraverts reported significantly higher willingness to return than extraverts (p = 0.042, z = 2.461, r = 0.168). Differences between ambiverts and the other two personality groups did not reach significance after correction.

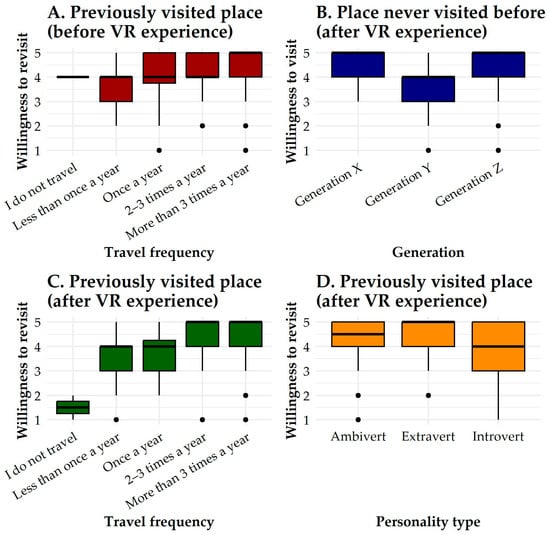

To further illustrate these associations, Figure 9 presents boxplots of willingness-to-visit ratings by the factors that reached or approached significance. Figure 9A shows differences in willingness to revisit before VR across travel frequency groups, while Figure 9C illustrates the same comparison after VR. Figure 9B presents differences in willingness to visit new destinations after VR by generation, and Figure 9D shows willingness to revisit after VR by personality type.

Figure 9.

Boxplots of willingness-to-visit ratings by participant characteristics: Panel (A)—willingness to revisit a previously visited place before VR experience by travel frequency; Panel (B)—willingness to visit a never visited before place after VR experience by generation; Panel (C)—willingness to revisit a previously visited place after VR experience by travel frequency; Panel (D)—willingness to revisit a previously visited place after VR experience by personality type.

The patterns shown in Figure 9 align with the Dunn post-hoc comparisons. Figure 9A indicates that willingness to revisit before VR was generally higher among participants who traveled more frequently, with those traveling more than three times per year reporting the highest scores. Figure 9B reveals clear generational differences in willingness to visit new destinations after VR: members of Generation Y displayed significantly higher ratings compared to both Generation X and Generation Z, suggesting that this cohort was most responsive to VR stimulation in terms of aspirational travel. Figure 9C reinforces the strong effect of travel frequency after VR, with a marked contrast between frequent travelers (two to three times per year or more) and those who rarely or never traveled, the latter expressing the lowest willingness to revisit. Finally, Figure 9D shows that personality influenced willingness to revisit after VR: extraverts provided significantly higher ratings compared to introverts, while ambiverts occupied an intermediate position.

Together, these results highlight that while VR did not substantially alter aggregate travel intentions, specific subgroups—such as Generation Y, frequent travelers, and introverts—responded more positively to VR experiences, which suggests that immersive technologies may interact with personal and behavioral characteristics in shaping tourism-related motivations. In the end, for never-visited destinations after VR, generation (age) was significant, and travel frequency was near significant. For previously visited destinations, travel frequency was significant before VR, and both personality and travel frequency were significant after VR. Hence, H4 (Individual characteristics (gender, generation, education, personality type, VR use frequency, travel frequency, headset type) significantly differentiate willingness-to-visit (pre-VR, post-VR)) was partially supported.

4.6. Emotions Associated with the VR Experience

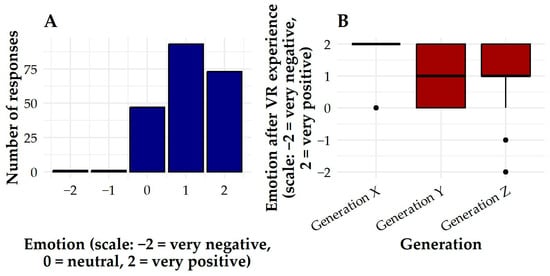

Participants were asked to evaluate their emotions after the VR session using a five-point scale, where −2 represented very negative emotions, 0 was neutral, and 2 indicated very positive emotions. The distribution of responses (Figure 10A) reveals that the majority of participants reported positive affective reactions to the VR experience. Specifically, the most common ratings were +1 and +2, while neutral evaluations were less frequent, and negative emotions were rare. This pattern indicates that the VR sessions were generally well received on an emotional level, with very few participants perceiving the experience in a negative way.

Figure 10.

Emotional responses to the VR experience: Panel (A)—overall distribution of emotions reported on a scale from −2 (very negative) to +2 (very positive); Panel (B)—emotional responses grouped by participant generation.

To further explore the role of emotions, their associations with satisfaction and willingness-to-visit scores were assessed. Spearman correlations consistently showed positive and statistically significant relationships. More positive emotions were associated with higher satisfaction with the VR sessions for both contexts: visiting a previously unknown place (ρ = 0.434, p < 0.001) and revisiting a familiar place (ρ = 0.440, p < 0.001). Emotions also correlated with willingness ratings, although the associations were weaker: for visiting a new destination post-VR (ρ = 0.242, p < 0.001) and revisiting a known destination post-VR (ρ = 0.372, p < 0.001). Even pre-VR willingness scores showed a smaller but significant link with emotions (ρ = 0.159 for new destinations, p = 0.020; ρ = 0.307 for known destinations, p < 0.001). These results suggest that emotions elicited during VR play a particularly strong role in shaping satisfaction, and to a lesser extent also in reinforcing intentions to visit or revisit destinations. Importantly, affective responses appeared to matter more for revisiting known places than for exploring new ones.

Beyond correlations, non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to examine whether emotions differed across socio-demographic and behavioral groups. The results indicated significant differences for generation (χ2 = 6.63, df = 2, p = 0.036, η2 = 0.022), education (χ2 = 6.91, df = 2, p = 0.032, η2 = 0.023), and travel frequency (χ2 = 9.89, df = 4, p = 0.042, η2 = 0.028). No significant variation was observed for gender, personality, VR use frequency, or headset type (all p > 0.36).

Post-hoc Dunn tests provided more detailed insights. For generation, participants from Generation X reported significantly more positive emotions than those from Generation Z (padj = 0.031, r = 0.175). However, this result should be interpreted with caution, as Generation X was represented by only 11 individuals in the sample, making the finding tentative at best. Comparisons between Generations X and Y, and Y and Z, were not statistically significant after adjustment. For education, none of the pairwise contrasts reached significance after Bonferroni correction, suggesting only a weak overall trend. Similarly, while the omnibus test indicated differences across travel frequency categories, none of the specific pairwise contrasts remained significant after adjustment (padj ≥ 0.243).

Figure 10 illustrates these findings: Figure 10A presents the overall distribution of emotional evaluations after VR, while Figure 10B shows generational differences. The visualization confirms that most participants, regardless of group, experienced the VR sessions as positive, underscoring the technology’s potential to generate favorable emotional engagement in tourism contexts.

Taken together, these results highlight the central role of affective responses in shaping participants’ evaluations of VR experience. Emotions were not only predominantly positive but also systematically associated with satisfaction and, to a lesser extent, with intentions to visit or revisit destinations. Although some group differences in emotions emerged, these effects were relatively modest and should be interpreted with care, particularly in the case of generational contrasts where sample sizes were uneven. In the end the correlations showed moderate positive associations between emotion valence and both satisfaction and intention indicators for both destination types, and emotions were also related to generation and travel frequency. Thus, H5 (Emotion valence experienced during VR is positively associated with satisfaction and willingness-to-visit (pre-VR, post-VR, Δ)) was supported.

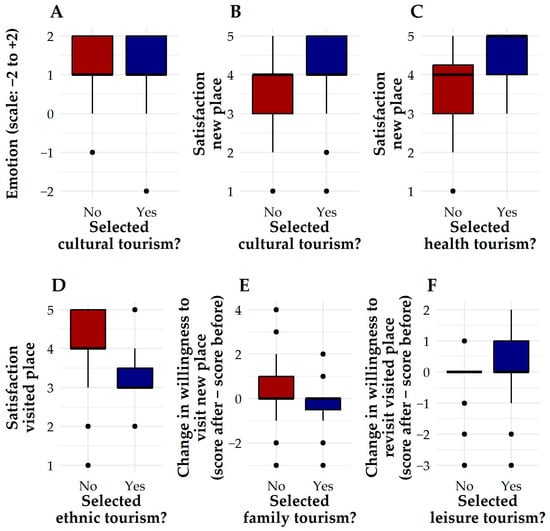

4.7. Preferences and Their Associations with Affect and Evaluation

To examine whether declared tourism preferences were linked to affective and evaluative responses to VR, we contrasted respondents who did versus did not indicate a given preference category. Several omnibus Kruskal–Wallis tests reached the 0.05 level (Figure 11). Participants selecting cultural tourism reported more positive emotions after VR than those who did not (χ2 = 4.66, df = 1, p = 0.031, η2 = 0.017; Figure 11A). However, descriptive statistics revealed only a modest mean difference (M = 1.23 vs. 1.03), with identical medians across groups, indicating that this effect should be interpreted as a tendency rather than a strong group distinction. They also declared higher satisfaction in the “new place” scenario (χ2 = 3.931, df = 1, p = 0.0474, η2 = 0.014; Figure 11B). Respondents indicating health tourism likewise showed higher satisfaction for the “new place” experience (χ2 = 9.83, df = 1, p = 0.0017, η2 =0.041; Figure 11C). In contrast, those who selected Ethnic tourism tended to rate the “visited place” scenario less favorably (χ2 = 4.58, df = 1, p = 0.0323, η2 = 0.017; Figure 11D). With respect to changes in willingness (post–pre), preference for Family tourism was associated with a smaller increase (or slight decrease) in willingness to visit a new place (χ2 = 3.88, df = 1, p = 0.049, η2 = 0.013; Figure 11E), whereas preference for leisure tourism was linked to a larger positive change in willingness to revisit a known place (χ2 = 6.43, df = 1, p = 0.0112, η2 = 0.025; Figure 11F). All other preference categories showed no meaningful associations with emotions, satisfaction, or change scores (all p > 0.05).

Figure 11.

Boxplots comparing emotions, satisfaction, and pre–post changes by declared tourism preferences: Panel (A)—cultural tourism vs. emotion; Panel (B)—cultural tourism vs. satisfaction (new place); Panel (C)—health tourism vs. satisfaction (new place); Panel (D)—ethnic tourism vs. satisfaction (visited place); Panel (E)—family tourism vs. change in willingness to visit a new place; Panel (F)—leisure tourism vs. change in willingness to revisit a visited place.

Because multiple preference categories were tested in parallel, the results should be interpreted with caution. The observed associations highlight potentially meaningful differences between tourism segments—for example, stronger positive responses among participants oriented toward cultural or health tourism, and weaker or more ambivalent patterns among those selecting ethnic or family tourism. These findings are best regarded as exploratory signals rather than definitive evidence, pointing to promising directions for future studies with larger and more balanced samples.

In summary, Respondents who preferred cultural tourism reported more positive emotions and higher satisfaction for never-visited destinations. Health-tourism enthusiasts also reported higher satisfaction for new destinations. In contrast, ethnic-tourism oriented respondents evaluated new places lower, and family-tourism oriented respondents reported lower willingness to visit new places, while leisure-tourism oriented respondents showed higher post-VR increases for known destinations. Thus, H6 (Tourist preferences (declared preferred types of tourism) significantly differentiate emotion valence and satisfaction (for previously visited and previously unseen destinations)) was supported.

5. Discussion

5.1. Responsible Tourism in the Context of Global Challenges

Today, the concept of responsible tourism is particularly relevant given the dynamic growth of global mobility, easy access to transportation, and the increasing availability of travel. The number of tourists worldwide is constantly growing, which, on the one hand, fosters cultural exchange and economic development, but on the other, leads to serious environmental challenges. Intensive tourism results in carbon dioxide emissions [96], environmental degradation [97], the destruction of cultural heritage [98], and the phenomenon of overtourism in popular destinations [99]. In this context, responsible tourism is becoming not just an idea but a necessity—a way to mitigate the negative impacts of travel and incorporate ethical, ecological, and social values into the tourism process.

However, as the literature emphasizes, despite widespread interest in the concept of responsible tourism, practical tools and solutions that would enable its practical implementation are still lacking. It often remains merely declarative—a theoretical concept with positive assumptions but without specific mechanisms for its practical implementation. Authors such as Wheeler [25] and Goodwin [26] point out that responsible tourism is sometimes perceived as an attractive idea, but its effectiveness is limited unless accompanied by systemic changes and concrete tools. In this context, the use of modern technologies, such as virtual reality, may be one of the missing links enabling the practical implementation of responsible tourism principles.

5.2. Virtual Reality as a Tool for Responsible Tourism

Virtual reality can significantly support the concept of responsible tourism on many levels. Primarily, it helps reduce tourist pressure on particularly sensitive sites—both environmentally and culturally. Thanks to immersive experiences, users can realistically visit museums, monuments, and national parks without being physically present, helping to protect these sites from degradation, littering, and excessive tourism. VR also enables contact with areas that are difficult to access or closed to tourists for conservation reasons [46,68], and allows for exploration of remote locations without the need for long, high-emission journeys. In this sense, virtual tourism can contribute to reducing CO2 emissions and the carbon footprint associated with tourist travel.

Another benefit is the educational and awareness aspect. VR allows for engaging and emotional presentations of issues related to environmental protection, local culture, and sustainable development [62]. The immersive nature of the content allows users to respond more emotionally [100,101], increasing the effectiveness of the educational message and fostering pro-ecological attitudes. Virtual experiences can also foster empathy and understanding of other cultures, fostering the idea of responsible behavior in interactions with the inhabitants of the places visited [102].

The social dimension of VR, related to inclusivity, cannot be overlooked. Generally, immersive technologies such as VR, augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) demonstrate the potential to be tools supporting inclusivity in various spheres of human activity [103,104,105]. Of course, such technologies can also enhance certain problems and barriers (e.g., fear of operating goggles), but their gradual introduction and familiarization with them can lead to significant benefits [106]. For older people [107], those with limited mobility [108], or disabilities [109], VR offers an alternative form of participation in tourism and culture. The same refers to other health, physical, financial, or political reasons [11]. It allows them to experience travel, explore the world, and connect with heritage, experiences that would often be impossible in real life. In this way, this technology supports the concept of accessible and equal tourism, expanding the boundaries of participation in culture and heritage.

5.3. Summary of the Study Findings

In the context of our own research, it is important to emphasize that the results confirm the positive reception of VR experiences by users. Participants rated their satisfaction with the virtual places they visited as high. They were asked whether the exploration of a given place was satisfactory, using a Likert scale from 1 to 5. For the place they had already visited, the average rating was 4.01. The most frequently chosen points were 4 (38.4% of participants) and 5 (36.6%). For the place, participants had never visited before and wanted to see, the average rating was 3.83. The most frequently chosen ratings were 4 (40.7%) and 5 (27.8%). This indicates that this technology can be an attractive alternative to traditional ways of exploring the world. These findings are consistent with prior studies showing that immersive VR experiences generate high satisfaction and engagement among users (e.g., [110,111]). Similar to those results, our participants perceived VR as an attractive and enjoyable way of exploring destinations. When it comes to relations examined, Spearman’s rank correlations revealed significant positive associations: higher satisfaction was linked to greater increases in the intention to visit new destinations (ρ = 0.306, p < 0.001) and in the willingness to return to previously visited places (ρ = 0.297, p < 0.001). On the other hand, our results revealed that that although VR exposure did not uniformly alter intentions across the entire sample, its impact was moderated by the level of satisfaction with the experience. Participants who found the VR experience more satisfying were more likely to increase their willingness to visit destinations, underlining the importance of user experience quality in leveraging VR for tourism applications.