Abstract

This research study addresses the critical contradiction within global food systems: unsustainable consumption patterns and persistent food insecurity coexist and are exacerbated by food waste, which deepens socioeconomic inequalities and generates negative environmental externalities. In this scenario, higher education plays a central role in adopting comprehensive strategic frameworks to develop specialized human capital and influence society. This study analyzes a Service Learning model that integrates the CFS-IRA Principles to promote the SDGs and ensure responsible consumption. Based on a case study of the Food Bank Chair spanning 10 years and 212 projects, the implementation of this model was evaluated using the Working with People (WWP) method, which combines the development of postgraduate students’ skills with community service to address social problems. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of the SL-WWP model in strengthening students’ technical, social, and ethical competencies while reducing food waste. The evaluation showed strong alignment with key SDGs, with outstanding performance in governance, although the need to strengthen environmental and social criteria was identified. The originality lies in integrating the CFS-IRA Principles into an SL model that encourages innovative cooperation among universities, civil society, and public–private sectors, offering a replicable proposal for higher education institutions to establish themselves as agents of change towards sustainability.

1. Introduction

The promotion of sustainability in three dimensions—economic, social, and environmental—including the reduction in food waste, is high on the agenda of higher education institutions [1]. Their role in the formation of responsible leaders and their ability to influence sustainability policies and practices position them as key actors in the fulfillment of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [2].

The problem addressed in this research study is the need to frame these efforts within a global reality characterized by the unsustainable use of resources. Currently, humanity consumes the equivalent of 1.7 planets to maintain its lifestyle, and it is estimated that if this trend continues, 3 planets would be needed to meet future demand [3]. This situation contrasts with persistent levels of poverty and hunger; in 2023, more than 733 million persons faced food insecurity [4]. This paradox is accentuated when considering that, while millions of people suffer from extreme hunger, more than 1000 million tons of food are wasted annually globally, equivalent to 19% of the products available for consumption [5].

In Spain, in 2024, food waste accounted for 3.7% of the total food and beverages purchased, which is equivalent to more than 1125 million kilos/liters [6]. This phenomenon not only aggravates social inequalities but also leads to severe environmental consequences, such as soil erosion, deforestation, water and air pollution, and increased greenhouse gas emissions [7,8,9].

Against this backdrop, the motivation behind this research study, i.e., to highlight the need for higher education to adopt strategic frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-IRA) Principles, which provide concrete guidance for addressing critical social, environmental, economic, and governance challenges, becomes a priority [10].

Many studies have proposed specific actions to mitigate the problem of food waste, with emphasis on raising consumer awareness regarding the responsible use of food [11,12]. These initiatives have been developed at different levels—international, national, and local—and include campaigns aimed at diverse audiences, especially young people [13,14,15].

This study presents a model of Service Learning projects that integrates the CFS-IRA Principles and the SDGs as implemented by the so-called Chair of Food Banks (FBC) of the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM), as an innovative structure in the educational field. This FBC partnership, formed in 2013 between FESBAL and the GESPLAN Research Group, has made it possible to carry out 212 projects over a decade, aimed at raising awareness about food waste and promoting responsible consumption, using the Working with People methodological approach [16].

This research study aims to analyze the SL model as a methodological proposal that enables a strengthening of the competencies of students at the postgraduate level while generating impacts on society in collaboration with third-sector organizations and Food Banks which work for sustainable development [17,18,19,20]. It also highlights the strategic role of the university as a platform for the design of sustainable interventions, aligned with the principles of social justice, environmental sustainability, and participatory governance [21].

The findings indicate that the integration of the SL model with the CFS-IRA Principles within the FBC framework results in consistently high ratings across all sustainability dimensions (social, environmental, economic, and governance). Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that the distinctive contribution of this research study lies in the introduction of an innovative evaluation framework for applying the Principles to the SL model [3,16,17,18,22]. The empirical evidence demonstrates that this methodology serves as a valid instrument for the systematic analysis and optimization of sustainability-oriented projects, enabling the identification of specific improvement areas across all dimensions.

Literature Review: SL Projects, CFS-IRA Principles, and FBC

Service Learning projects (SL model) have established themselves as fundamental tools for linking higher education with contemporary social challenges [22,23]. This methodological approach makes it possible to address complex problems, such as food waste, environmental sustainability, and social inclusion, by implementing learning projects with community impact [24]. Various authors have highlighted the benefits of the SL model, which, for example, fosters key competencies, promotes experiential learning, and strengthens student civic engagement, especially in the university environment [25].

These SL projects combine academic theory with community practice, encouraging students’ participation in their own learning while addressing real problems in their communities [26,27]. This methodology not only contributes to the development of academic skills but also promotes values such as social responsibility and teamwork, preparing students to face the challenges of today’s world [28]. SL projects involve “serving while learning” or “learning while serving” [29,30,31] and are thus focused on improving students’ understanding of theory by enabling them to provide community service and reflecting on the experience [32].

Although it is often considered a recent proposal, the SL model has its roots in the nineteenth century in the United States, with projects linking academic learning and community engagement [33,34]. In 1916, John Dewey, who was among the first to lay the foundations of what we know today as the SL model, argued that students would learn more effectively and become better citizens if they committed themselves to community service and integrated this experience into their academic curriculum [35,36].

In 1969, the term as we know it today was consolidated at the first Service Learning Conference in Atlanta [33]. According to educators, this term implies that service is an important value in integral formation, since it represents a link among authentic community service, intentional academic learning, and reflection [37].

In recent decades, multiple definitions have emerged to describe Service Learning, considering it a methodology, experience, project, pedagogy, and even educational philosophy [38]. Despite this conceptual diversity, there is consensus that the SL model is articulated around organized activities that seek to satisfy community needs while enriching academic learning through reflection [39,40].

Various studies underscore its potential to connect theory and practice, strengthen civic engagement, and broaden citizen participation [41,42,43]. From an applied perspective, the SL model has also been adopted as an instrument of community intervention, with the aim of transforming the social, educational, and environmental spheres and promoting the development of personal, social, and professional skills in young people [44]. In this sense, a well-designed Service Learning project allows students to assume meaningful responsibilities within their educational and social communities, contributing to the strengthening of the social fabric [45,46,47].

This approach is particularly relevant in the context of sustainable development. Through SL projects, students not only apply acquired knowledge but also become active agents of change by promoting responsible consumption practices and environmental sustainability. These initiatives align closely with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Responsible Investment in Food and Agriculture (CFS-IRA) Principles, providing a robust operational framework for the design of educational interventions with transformative impact. In this way, Service Learning transcends academic training to become a strategic tool for social transformation.

The SL model is tightly linked to Project-Based Learning (PBL), with which it shares the methodological foundation: active, meaningful, and contextualized learning [48]. The SL model can be considered to be PBL with a social purpose, with projects not only becoming vehicles for learning and developing skills but also opportunities for sustainable, ethical development and social responsibility [49].

Among the various human activities, consumption is among those with the greatest impact on the environment [50,51,52]. George Fisk defined responsible consumption as a rational and efficient use of resources considering the needs of the global population, a vision underscoring the importance of adopting ethical and conscious consumption habits. Numerous studies have shown that many environmental problems can be mitigated by modifying the behaviors at their root [53].

Responsible consumption has traditionally been understood as a rational practice in which informed citizens make decisions that consider the social and environmental impact of their actions [54,55]. In this context, the growing academic and social interest in behaviors related to food waste has driven research aimed at identifying its causes and developing intervention strategies [56,57,58].

Since the 1980s, the study of consumption habits among children, adolescents, and young people has intensified, as these groups have been highly exposed to commercial stimuli and have played an increasingly active role as consumers [59,60]. This evolution has been influenced by a culture of leisure and consumption that often relegates other fundamental values [61]. Consequently, the transformation of individual ethical codes has placed consumption as the structuring axis of social identity [62,63]. It is crucial to encourage critical thinking in education, promoting individual and collective responsibility as a basis for sustainable development [64,65].

In this sense, the SDGs and the CFS-IRA Principles offer a strategic framework that seeks to balance economic growth, social equity, and environmental conservation. The SDGs, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, set out 17 global targets to eradicate poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all. These are articulated around five fundamental pillars: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership [66]. The CFS-IRA Principles are the result of a global consultation process led by the FAO between 2012 and 2014 and played a key role in the formulation of the SDGs, as they promote sustainable agricultural and food investments through a comprehensive vision that considers human rights, gender equity, sustainable resource management, and inclusive participation [67,68,69].

Both frameworks align with the four key dimensions of sustainability: social, environmental, economic, and governance [22,70,71].

Partnerships between universities and third-sector entities are essential to translating these principles into concrete actions. An example is the Chair of Food Banks (FBC), resulting from the collaboration between the Spanish Federation of Food Banks (FESBAL) and the GESPLAN Research Group. All FBC projects seek to contribute to solving the most pressing problems of society, such as hunger and food waste.

The Spanish Federation of Food Banks (FESBAL) is a non-political and non-denominational entity founded in 1995 which coordinates and represents the Food Banks of Spain in their fight against hunger, poverty, and food waste. Its mission includes the recovery and redistribution of food to people in need while promoting environmental sustainability [72].

FESBAL is made up of 54 Food Banks throughout Spain, which, in 2023, distributed food to 6919 charities, benefiting more than 1.2 million people. In addition, it is a member of the European Federation of Food Banks (FEBA) and the Global FoodBanking Network (GFN) and was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for Concord in 2012 [73].

In 2013, the Food Bank Chair (FBC) was created with the purpose of strengthening, supporting, and raising awareness about rational and responsible food consumption; it promotes training in values of solidarity and sustainability and contributes to the reduction in food waste.

The Chair develops educational programs aimed at different levels, from primary and secondary education in schools and institutes to undergraduate and postgraduate degrees in higher education institutions [74], as well as specific training activities for professionals. Within this framework, conferences, seminars, and round tables are organized, and scholarships and support for the completion of doctoral theses and final degree projects are offered. The training provided is aimed to develop key competencies, such as leadership, sustainability, social responsibility, and community cohesion.

In 2014, the FBC launched the Rational Food Consumption (CORAL) Program, an educational initiative aligned with the SDGs that seeks to raise awareness about responsible and ethical food consumption. Aimed at primary, secondary, and baccalaureate students, the CORAL Program promotes awareness about the importance of avoiding food waste and reflection on its link with problems such as poverty and hunger. This program, in line with the mission of Food Banks, promotes social ethics from the earliest educational levels, providing students with practical tools to adopt more responsible consumption habits [75].

FBC and FESBAL projects are aligned with the SDGs and the CFS-IRA Principles as they promote food security, the reduction in food waste, and sustainability in the distribution chain [76,77]. These actions range from community awareness to the implementation of strategies for the collection, conservation, and redistribution of surplus food. Likewise, research is being carried out to optimize logistic processes, and strategic partnerships are consolidated among the public, private, and academic sectors, generating a comprehensive and sustainable intervention model [69,78].

Among the most outstanding projects is the implementation of good practices through the use of Geographic Information Systems (GISs), such as the GIS-FESBAL tool. This platform enables the management and updating of information on the activities and impact of Food Banks in Spain, improving their operational capacity and social reach, in alignment with the SDGs and the CFS-IRA Principles [79,80,81].

The various projects developed in this context allow students to be trained in fundamental values and competencies to perform in the workplace in an ethical and responsible way [82]. These values and skills are essential to promoting sensitivity to the most complex social realities. In terms of technical skills, priority is given to the acquisition of skills that allow projects to be carried out with impact, following the international standards of the International Project Management Association (IPMA). The competencies defined by these frameworks include technical, behavioral, and contextual aspects, which are essential to addressing the challenges of sectors such as construction, industry, the environment, energy, or technology [83,84,85].

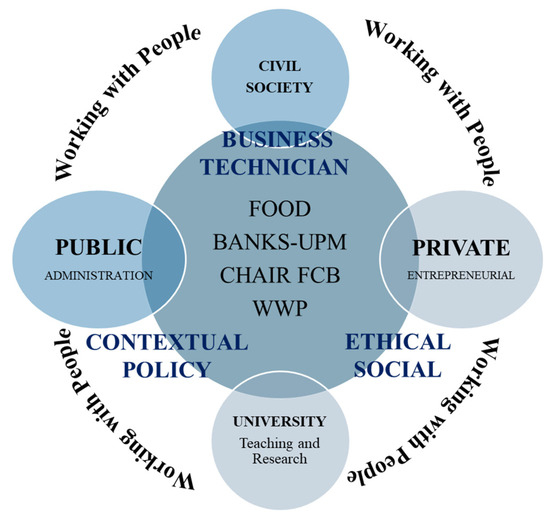

Based on the conceptual foundation, the SL model developed by the FBC is applied to foster training in relevant values with the acquisition of skills, a reduction in food waste, and the establishment of sustainable food systems. Figure 1 summarizes this SL-WWP model for implementing Service Learning projects in three main areas: (1) training and educational cooperation, (2) dissemination and transfer of knowledge, and (3) promotion of research, development, and innovation.

Figure 1.

SL-WWP work model of FBC-UPM. Reprinted from [49] with permission.

2. Materials and Methods

We analyze the accumulated experience of ten years of work of the FBC, in collaboration with FESBAL and its 54 associated banks, as a case study. The SL-WWP [49] work model is used to evaluate the Service Learning projects developed by the FBC (Figure 1), assessing each one with a specific measurement tool.

Figure 2 shows the FBC’s collaborative ecosystem that enables interaction among various public and private actors, the university, and related civil society organizations.

Figure 2.

Working with People model.

In the development of this research, artificial intelligence (AI) tools were employed to assist in the literature search and review phases. Specifically, the platforms Consensus and SciSpace were used to locate relevant academic literature, synthesize key findings, and refine the accuracy of citation references. The purpose of using these tools was to streamline the document review process and ensure comprehensive bibliographic coverage. It should be noted that all ideas, analyses, and interpretations presented in the manuscript are solely those of the authors, and any content generated or suggested by AI was critically evaluated and verified before being incorporated into the study.

Implementation of SL Projects and CFS-IRA Principles

By applying the case study approach, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of a population of 212 SL model projects that integrate the Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-IRA) Principles defined by the FAO [86], where the Principles constitute a comprehensive framework that addresses social, environmental, economic, and governance aspects to promote sustainable investments in agriculture.

Each project was evaluated according to 10 fundamental Principles, using a Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 represents a very low impact and 5 a very high impact in relation to each Principle, enabling standardized and comparative assessment. Furthermore, based on an internationally recognized sustainability framework, the Principles were grouped into four key dimensions to facilitate analysis:

Social Dimension: Food security and nutrition (P1), gender equality (P3), and youth participation (P4).

Environmental Dimension: Sustainable tenure and management of natural resources (P5 and P6) and sustainability of agricultural and food systems (P8).

Economic Dimension: Inclusive economic development (P2) and promotion of cultural heritage, diversity, and innovation (P7).

Governance Dimension: Responsible and inclusive governance (P9) and accountability (P10).

The final value of each dimension was calculated as the simple average of the grouped Principles, ensuring transparency, comparative assessment, and reproducibility of result synthesis. Equal weight was assigned to each Principle within its dimension, enhancing evaluation credibility based on the strong content validity of the CFS-IRA framework for measuring sustainability. The overall project rating was obtained as the average of the four dimensions.

This methodology facilitated the acquisition of normalized comparative measurements. Consequently, the dataset derived from the analysis is available in the Results Section, which compiles the calculated metrics. The instrument’s validity is demonstrated through its capacity to identify improvement opportunities in each dimension, as shown in Results, establishing foundations for feedback and continuous improvement processes.

The evaluation was conducted by the interinstitutional research team that coordinates the FBC, which includes the authors, with support from experts of the GESPLAN Research Group. Therefore, project assessment was carried out according to a collaborative and rigorous process. The participation of experts ensured that the application of the evaluation instrument benefited from their empirical experience, as they are actively involved in project implementation, and validated the results.

However, it is significant to note that although the implementation of the CFS-IRA Principles, their application across the four sustainability dimensions, and SDG promotion served as the evaluative basis, this study did not explicitly document formal training processes to standardize evaluation criteria among raters, nor were inter-rater reliability measures calculated (such as the Kappa coefficient or correlation), which should be considered a methodological limitation.

The formal analysis of the 212 projects was supported by a rigorous data curation process, collaboratively executed by the four authors. This procedure involved two sequential phases: first, the verification of the effective implementation of the CFS-IRA Principles as a fundamental inclusion criterion; second, the removal of records with incomplete or inconsistent data, as can be seen in Table 1. Only after this comprehensive validation were the simple averages for the sustainability dimensions calculated, thereby ensuring result reliability.

Table 1.

Assessment rubric used in the analysis.

Likewise, SL projects are integrated in the curriculum of the master’s degree and doctorate in Rural Development Project Planning and Sustainable Management at UPM. In 2009, this program was accredited within the IPMA Registry of Skills Development Programs, being a pioneer in the application of these competencies to sustainable rural development in Spain. In addition, the International Postgraduate Program for Sustainable Rural Development—Erasmus Mundus—has been developed with the participation of five universities of the European Union, which formed the Agris Mundus Alliance for Sustainable Development [87]. The development and assessment of competencies in this program are supported by the framework of the International Project Management Association (IPMA) based on the IPMA Competence Baseline (ICB) standard, and since 2016, the program has integrated the Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-IRA) Principles in its learning curriculum. The program is integrated into the meta-university and has been consolidated in an international network of 46 universities and 52 business organizations in 12 countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain committed to the implementation of these principles (https://principiosirametauniversidad.com, accessed on 29 September 2025) aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Among these CFS-IRA Principles, No. 4, focused on youth empowerment, stands out as it is directly aligned with target 4.7 of SDG 4, which promotes education oriented towards sustainable development.

Below, Table 2 summarizes the curricular contents of the master’s degree, identifying the learning objectives, the IPMA competencies applied, and the service actions linked to the SL projects.

Table 2.

Curricular contents of master’s degree linked to SL model and IPMA competencies.

3. Results and Discussion

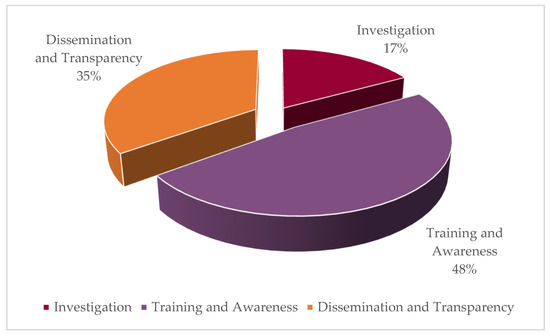

The research results obtained following the integration and analysis of the information collected during 2014–2024 are presented below. The SL projects carried out by the FBC were categorized into three lines of action to facilitate their analysis: training and awareness raising, dissemination and transfer of knowledge, and research. Table 3 summarizes the 212 projects, providing the average and total scores per dimension (social, environmental, economic, and governance). Additionally, Figure 3 compares the percentages of the dimensions across these categories.

Table 3.

Projects by line of action.

Figure 3.

Project percentages by line of action.

3.1. Global Scope of Service Learning (SL) Projects

The SL-WWP model has generated a relevant impact on the training of students and teachers, as well as on the beneficiary communities, when implemented in the Service Learning (SL) projects developed along three lines of action: training and awareness (49%), research (17%), and dissemination and transfer of knowledge (34%).

The scope of the impact is evaluated based on the projects’ contribution to society, particularly children and young people, the main recipients of the various initiatives [88]. It should be noted that this impact is also evident in the sustainability of many of these projects, such as the CORAL Program, which has been implemented over time since the model was established. This sustained growth has favored cooperation among different organizations, mainly Food Banks, promoting positive experiences with the most vulnerable sectors of society. The projects are coordinated by the FBC, which makes joint decisions with FESBAL and the UPM team, generating effective solutions for various social problems throughout the years. Table 4 shows the extent of these impacts.

Table 4.

Impact of Service Learning (SL) projects.

Over the years, some projects, such as the CORAL Program (in the area of awareness), have been consolidated, reflecting growing acceptance of this methodology among Food Banks and educational entities. The cumulative impact of SL projects during the period analyzed reflects that this model is a key pillar in academic training, providing transformative and meaningful educational experiences [89,90,91].

Entities Involved According to Project Areas

The analysis of the entities involved according to project area reveals significant differences in the levels of participation, depending on the type of entity and the thematic axis addressed. Firstly, it is observed that public entities have outstanding participation rates in all areas, being especially prominent in training and awareness, with 2031 entities (46.70%), and in dissemination and transfer, with 191 entities (42.26%). This finding coincides with previous studies that highlight the central role of public institutions in promoting sustainable development policies and environmental education [92,93]. These entities mainly include regional and local governments, as well as public educational entities that actively collaborate in awareness and training programs.

On the other hand, private entities, mainly companies, show balanced participation in the different areas, with 1139 entities (26.19%) in training and awareness, 151 entities (33.41%) in dissemination and transfer, and 10 entities (5.35%) in research. Among these, the company ESRI Spain stands out, as it contributes to the GIS-FESBAL project by offering use of its technology, an innovative Geographic Information System (GIS) aimed at monitoring FBC projects [94]. This trend could reflect greater orientation towards technological innovation and product development rather than towards social awareness, as suggested by the literature on corporate social responsibility [95].

Civil society entities show outstanding participation rates in all SL project areas, standing out in research, with 161 entities involved (86.10%); the records show 1179 (27.11%) civil society entities in training and awareness and 110 (24.34%) in dissemination and transfer, as can be seen in Table 5. This diversity indicates a great adaptability of third-sector organizations, which usually act as a bridge between local communities and public policies, also collaborating in the generation and application of knowledge [96].

Table 5.

Entities involved according to project area.

In general terms, it can be concluded that public entities lead in the number of participants in SL projects, followed by civil society entities and private entities. These results support the idea that the public sector assumes a key role in the implementation of development projects, while the private sector and civil society act as complementary collaborators with more specialized approaches.

3.2. Service Learning (SL) Projects Aimed at Training and Raising Awareness

In the category of training and awareness, 103 SL projects have been implemented, representing 49% of the total. These projects are the basis for concretely contributing to addressing the challenges associated with food production and consumption patterns while promoting responsible investments in the agricultural sector, in line with the principles of the CFS-IRA Principles and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [69,97].

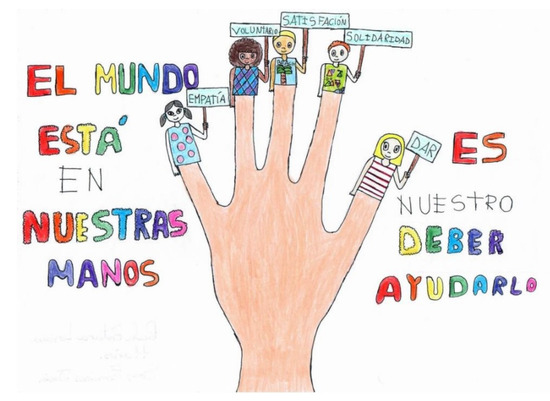

One of the most outstanding projects is the CORAL Program, aimed at raising awareness about responsible food consumption. This initiative, coordinated by the FBC and FESBAL, involves educational centers throughout Spain. Each of the ten annual editions is an SL project mainly aimed at primary school students and organized into four phases: preliminary, regional, national, and awards ceremony. In the preliminary phase, Food Banks, with the support of the Food Bank Chair, carry out educational and awareness-raising activities in the participating schools. In the regional phase, local juries select the best drawings sent by the centers in their jurisdiction. The winning works (three from CET and one from CEE) are registered on the ArcGisSurvey123 platform or sent by email. The national phase involves the evaluation of these works by the jury of the Food Bank-UPM Chair, which proposes the winners and honorable mentions to FESBAL. Finally, at the awards ceremony, the four winning drawings at the national level receive a diploma and a prize during the annual “Golden Spike Awards” ceremony organized by FESBAL at CaixaForum—Madrid [98].

As shown in Table 6, the results of the ten editions of the CORAL Program’s drawing competition show a progressive expansion both in territorial coverage and in the number of participants, consolidating this initiative as an effective strategy for education and awareness among children and adolescents about food security and sustainability. The participation of 780 schools and more than 38,000 students reflects the project’s ability to generate meaningful learning through artistic and participatory methodologies, in line with transformative pedagogy approaches [99,100]. At the same time, the sustained increase in the number of Food Banks involved—from 4 in the first edition to 19 in the most recent ones, with a cumulative total of 116—demonstrates the strengthening of territorial cooperation networks, a key aspect in the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 17 (Partnerships to Achieve the Goals), based on the promotion of cooperation among social, educational, and third-sector actors [101,102]. The results of the drawing contest are illustrated in Figure 4, which shows one of the award-winning works from the latest edition.

Table 6.

Results of the SL project of the Drawings in Schools contest carried out by the FBC.

Figure 4.

Third place in the drawing contest, 3rd A Coruña Paula Botana Lozano Colegio San Francisco Javier.

The drop observed in the sixth edition (2019–2020) in school participation and number of drawings is directly linked to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on educational processes and extracurricular activities [103]. However, the immediate recovery in subsequent editions shows both the resilience of the program and the sustained commitment of the educational community. This capacity for adaptation confirms the potential of non-formal education as a space for containment, motivation, and pedagogical continuity in crisis contexts [104]. The use of drawing as a means of expression has been shown to be effective in encouraging students’ critical reflection on problems such as food waste, inequality, and solidarity. Previous research has underlined the value of creative practices for the development of socio-emotional and citizenship competencies in childhood [105,106], reinforcing the value of the contest as a comprehensive educational practice. In short, the contest has evolved not only quantitatively but also in its qualitative dimension, constituting a transformative educational experience with the potential for replicability and integration in public policies of education for sustainability.

This area also includes the Final Master’s Project (FMP), as well as curricular internships and volunteer experiences that are undertaken as SL projects with the international master’s degree in Rural Development Project Planning and Sustainable Management. These projects have proven to be an effective way to integrate academic training with social commitment, allowing students to apply their knowledge in real contexts while developing technical and social competencies that are fundamental for comprehensive learning [107,108,109]. The application of the SL model in the FBP not only responds to a growing trend in the university environment but also constitutes an opportunity to strengthen the link between university and community, generating a transformative impact on both the student and the environment in which they intervene [110,111]. Within the framework of the Food Bank Chair (FBC-UPM/FESBAL), a diverse and transversal academic production has been consolidated in the form of Final Master’s Projects (FMPs) and Final Bachelor’s Projects (FBPs), which comprehensively address the challenges of the contemporary food system. The more than 25 recent research projects show remarkable thematic diversity, ranging from food security and sovereignty to surplus management, food waste, rural planning, and food public policy analysis, both in local and international contexts.

Among the topics analyzed are alternative food webs, organic certification, Food Banks, the evaluation of market management models, innovative sources of food (such as edible insects), and legislative aspects of food waste based on participatory approaches such as the Working with People model. Likewise, works focused on international cooperation can be identified, with case studies in Ecuador, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Peru, which reinforces the global nature of the food problem and the way in which it is addressed in applied research.

This diversity responds to the strategic objectives of the FBC, which include the fight against food waste, the promotion of food security, the promotion of university social responsibility, environmental sustainability, and development cooperation. In particular, several works are directly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), highlighting SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 17 (Partnerships to Achieve the Goals).

The academic research performed constitutes a key input for innovation in food policies, the design of sustainable intervention methodologies, and the raising of awareness among public and private actors about the importance of fair, resilient, and sustainable food systems.

Other SL projects are international and national seminars, which have a predefined scope, involve stakeholders, and evaluate learning outcomes, as can be seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Training and awareness projects.

3.3. Service Learning Projects in the Research Area

A total of 35 research projects have been conducted, representing 17% of the total. These are characterized by their applied orientation, their interdisciplinary approach, and the use of innovative technological tools aimed at solving real problems. The results of these projects are published by FESBAL in the form of technical reports, prepared according to a rigorous scientific methodology.

The topics addressed are diverse and include sustainable production, food waste, product analysis, good practices in the management of Food Banks, the study of poverty in Spain and the role of Food Banks (FBs), the analysis of public policies, research on food waste in school canteens, and the design of strategic plans to align Food Banks’ activity with SDGs and the CFS-IRA framework [1,72].

One of the most relevant projects has been the design and implementation of the Geographic Information System (GIS) Geoportal GIS-FESBAL, which provides a technical approach to territorial analysis and contributes to more sustainable planning (Observatory of Good Practices in Food Banks). This project aligns with previous studies that highlight the value of GISs in socio-environmental research [112].

Below are some representative examples of Service Learning (SL) projects in the field of applied research:

- The project “GIS as a Tool for Calculating the Carbon Footprint of Food Banks” [4] involved students in the collection and analysis of data to estimate the carbon footprint generated by the logistic operations of FBs by applying GIS tools and environmental sustainability methodologies [81].

- In the study “Towards Project-Based Governance from the SDGs and ESG Criteria: The Case of Food Banks”, the participation of students in the development of governance frameworks based on the SDGs and ESG criteria was promoted, strengthening the institutional and strategic dimension of FBs [113].

- The project “Learning from the Madrid Food Bank Experience: 30 Years of Work on Volunteer Projects to Help Vulnerable People” [114] made it possible to document the good practices accumulated over three decades of volunteer work by using qualitative methods, with the active collaboration of students in the analysis and systematization of data [115].

- In the research study “Exploratory Analysis of Plate Food Waste in School Cafeterias in Spain” [78], students participated in direct observation in schools and in the evaluation of eating habits, contributing to the design of strategies aimed at the prevention of waste.

- Finally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the study “Eating Behavior Changes Related to Individual and Household Factors during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Spain” [116], in which students actively participated in the design and application of surveys, as well as in the statistical analysis of the data obtained [117], was carried out.

These projects demonstrate the potential of Service Learning as a methodology that integrates academic training with the generation of useful knowledge for society, strengthening the research dimension of educational processes.

In the studied context, the work dynamics of the SL model are always collaborative, involving the interdisciplinary research team of the FBC and FESBAL. This enables the establishment of a knowledge foundation to address the current challenges of Food Banks and FESBAL in relation to sustainability, which, as pointed out in [118], requires integrating multiple dimensions to achieve significant impacts on public policies and local communities. In addition, the orientation towards practical application is inherent in action research approaches that seek to transform realities through the participation of various actors, as proposed in [119].

The inclusion of the social component in knowledge management and the participation of researchers from other universities and interest groups are key factors in the success of these activities. The authors of [120] similarly underline the relevance of stakeholder engagement in the context of sustainability-oriented projects.

Within the framework of the research initiatives analyzed, three main types of outputs were identified: Research reports represent the largest proportion, with 68.57% of the total, which shows a strong focus on the systematization of results and the generation of applied knowledge. Research projects constitute 17.14%, reflecting the promotion of more structured and far-reaching processes. Finally, the development of the GIS-FESBAL Geoportal represents 14.29%, highlighting the incorporation of technological tools for the visualization and spatial analysis of information related to food safety and the activity of Food Banks.

3.4. Service Learning (SL) Projects for the Dissemination and Transfer of Knowledge

Finally, in the category of dissemination and transfer of knowledge, 73 projects were carried out, representing 35% of the total.

These projects are aimed at disseminating results that reinforce academic training with dissemination and transfer actions while helping students develop oral and written communication skills. The students participating in these projects are mainly from the doctoral program in planning rural development projects and sustainable management, coordinated by the research professors collaborating with the FBC.

Various actions aimed at the dissemination and transfer of knowledge have been implemented, covering both general discussion spaces and specialized forums with wider audiences, e.g., international and national conferences presenting communications that enabled the exchange of research advances with the global and national scientific community. The transfer of knowledge is an essential function of universities, as part of their mission to contribute to social and economic development [121]. Through this function, higher education institutions not only generate knowledge but also apply it to solve community challenges, thus promoting collective well-being. This commitment is manifested in the so-called “third mission” of universities, which encompasses activities such as innovation, entrepreneurship, and collaboration with various sectors of society [122]. In this context, education emerges as a transformative tool, capable of empowering communities and fostering a more equitable and sustainable society [123].

The direct impact on beneficiary communities ensures the implementation of evidence-based strategies and promotes sustainable development through innovative and collaborative solutions.

As for the dissemination and transfer of knowledge, 22.97% of projects involved the presentation of communications at international conferences, constituting the most recurrent format. These are followed by national conferences and workshop- or seminar-type events (14.86%), which indicate active participation in training and discussion spaces at the local level. Studies published in research journals accounted for 12.16% of the total, while international conferences and other similar contributions accounted for 9.46% each. On the other hand, studies in popular journals and communications at national congresses showed lower percentages, 2.70% and 1.35%, respectively, evidencing a lower preference for formats involving the general public and discussion spaces of national scope.

3.5. Relationship of Projects with IRA Principles and the SDGs in the Dimensions of Sustainability

A total of 21 projects were evaluated by applying the Committee on World Food Security’s Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-IRA) Principles [88] and organized according to the four pillars of sustainability: social, environmental, economic, and governance. This assessment was complemented by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework [124].

The results show that the governance dimension had the highest score, with an average score of 4.0, followed by the economic dimension (3.0), the social dimension (2.4), and the environmental dimension (2.3), as can be seen in Table 8. This suggests a strong institutional commitment to transparency, participation, and organizational management, although significant challenges remain in integrating social and environmental criteria, which are crucial to comprehensive sustainability [125].

Table 8.

SL projects carried out by the FBC and their relationship with the CFS-IRA Principles and the pillars of sustainability.

Therefore, in the considered Service Learning projects, these dimensions show low integration of the related CFS-IRA Principles, thus of environmental and social indicators. This implies that, while there may be an intent to address socio-environmental issues, strengthening the systematic application and measurement of impact across all initiatives should be a priority; it could be accomplished by addressing the identified gaps, including incorporating food waste metrics as Key Performance Indicator (KPIs) in new projects and continuing to explore the inclusion of tools for estimating the carbon footprint.

Among the types of projects evaluated, research project stood out as the most balanced and robust, with a total score of 4.5, standing out especially in the environmental (4.67), economic (4.67), and governance (4.50) dimensions. This performance shows its direct alignment with SDGs 2 (Zero Hunger), 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and 13 (Climate Action) [126].

In the social dimension, educational cooperation projects obtained the highest score (4.5), reflecting their effectiveness in promoting inclusion, collaborative learning, and capacity building, in line with SDGs 4 (Quality Education) and 17 (Partnerships to Achieve the Goals) [127]. However, this dimension was the least integrated in the set of projects, which indicates the need to strengthen community impact strategies.

From the environmental perspective, although research projects stood out (4.67), most of the initiatives showed medium or low scores, which reveals a gap in the application of agroecological practices and climate resilience, an aspect that should be a priority in future interventions [128].

The economic dimension was also better integrated into projects with research or production orientation. Research projects again stood out, highlighting the potential of linking knowledge production with sustainable economic strategies.

Finally, the governance dimension was the most consistently applied. SL: TFG-TFM projects obtained the maximum score (5.0), reflecting consolidated participatory structures, institutionalization of processes, and transparency, in line with SDGs 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) and 17 [129].

A relevant finding is that a high total score does not always imply balance among dimensions. Some projects showed significant internal imbalances, which reinforces the need to design interventions that ensure coherence among the social, environmental, economic, and institutional aspects.

The Service Learning WWP model (SL-WWP), developed over a decade, includes the CFS-IRA Principles and the SDGs, implementing them, e.g., in local learning activities integrating academic programs and focused on raising awareness about food waste and responsible consumption.

Key intermediate results highlight the importance of the model’s overall framework for developing student competencies, applying the IPMA competence framework, and promoting the strengthening of partnerships. Furthermore, pilot waste reduction projects such as GIS-FESBAL Geoportal promote information monitoring and management. Among the directly measured results are reach, quality of design, and comparative standardized evaluation using a Likert scale. Inferred results include the contribution to improved food security, as evidenced by the benefits achieved in waste reduction and the application of the Principles.

In conclusion, the joint application of the CFS-IRA Principles and the SDGs has proven to be a useful tool for the analysis and improvement of projects with a sustainable approach. The most successful cases not only score well but also achieve synergies among dimensions, generating transformative, scalable, and inclusive impacts [68,88,129].

Considering the results, which reflect the need to strengthen the balance among the dimensions, a future evaluation using mixed methods is proposed. This approach would capture both efficacy and transformation by applying the following: A quantitative phase (Efficacy) prioritizing the inclusion of direct impact KPIs to measure waste reduction or the optimization of logistics would establish baselines and measure changes in the Food Banks’ logistical carbon footprint. A qualitative phase (Transformation) assessing social impact and transformative learning through qualitative studies (interviews, analysis of reflections, etc.) would make it possible to evaluate the acquisition of socio-ethical competencies by students and community cohesion.

This integration would allow for an assessment of overall coherence, revealing whether the high performance in governance (4.0) effectively translates into synergies and the generation of scalable, inclusive, and transformative impacts in the social and environ-mental dimensions.

4. Conclusions

This research study demonstrates the originality and effectiveness of integrating Ser-vice-Learning projects with the Working with People (WWP) methodological model and the Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems (CFS-IRA) Principles. This combination constitutes an innovative educational approach that tangibly contributes to the advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with special emphasis on responsible consumption and the reduction in food waste.

Among the most relevant findings is the validation of the SL-WWP model through a decade-long analysis of CBA-UPM-FESBAL, which has enabled the implementation of 212 projects across the lines of action of training and awareness, research, and knowledge transfer. The ability of this model to strengthen transversal competencies in students (technical, social, and ethical) while generating quantifiable positive impacts on vulnerable communities and third-sector actors is proven.

Furthermore, a structural alignment of the interventions with SDGs 2 (Zero Hunger), 4 (Quality Education), 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) is identified, reinforcing the relevance of the approach within the framework of the 2030 Agenda. Concurrently, the multi-criterion evaluation based on the sustainability dimensions (social, environmental, economic, and governance) reveals outstanding performance in governance, although a heterogeneous integration of environmental and social criteria is detected in some cases, pointing to a priority area for improvement. This disparity responds to clear institutional mechanisms, such as organizational incentives, and points to the need to establish well-defined coordination structures and reporting systems to ensure the continuity of projects which have prioritized governance aspects. In contrast, the evaluation of environmental and social impacts requires more complex indicators and longer timeframes, gaps which have limited the systematic development of these effects.

Based on the findings obtained, it is recommended to institutionalize the SL-WWP model in the university system by integrating it into curricula and social responsibility programs, alongside the development of standardized evaluation protocols that ensure the balanced incorporation of the social, environmental, economic, and governance dimensions. Likewise, it is essential to promote the transferability of the model to diverse contexts through the systematic documentation of best practices and the establishment of inter-institutional cooperation. Finally, it is suggested to strengthen multisectoral collaboration mechanisms, incentivizing the participation of the public–private sector in the co-design, financing, and scaling of projects, to guarantee the sustainability and long-term impact of the initiatives.

In conclusion, this work consolidates the role of higher education as a transformative agent of change, demonstrating that the strategic cooperation of university, civil society, and public–private sectors through SL projects constitutes an effective pathway for addressing complex challenges, advancing towards a more just, supportive, and sustainable society.

Limitations and Research Perspectives

The methodological approach of this research study inherently imposes limitations on the external validity of the findings, as it focuses on the analysis of a specific case study: the ten-year trajectory of the Food Bank Chair (FBC). Nevertheless, the SL-WWP model implemented within the FBC is considered a replicable proposal for other higher education institutions. Likewise, initiatives derived from this framework, such as the CORAL Program, have demonstrated potential for scalability and transferability.

In terms of limitations identified in the project evaluation, the results revealed significant challenges in the cross-cutting integration of certain sustainability criteria, specifically the social (average score of 2.4) and environmental (2.3) dimensions, which were the least integrated across the evaluated projects, in contrast with the governance dimension (4.0). This disparity underscores the need to strengthen community impact strategies (social dimension) and to bridge the existing gap in the effective application of agroecological practices and climate resilience (environmental dimension) in future interventions.

Additionally, it was found that a high aggregate score does not constitute an indicator of balance among the different sustainability dimensions (social, environmental, eco-nomic, and governance). This finding reinforces the need to adopt a more coherent and comprehensive intervention design that ensures a balanced and synergistic incorporation of all evaluation criteria.

Overall, this research study emphasizes that the integration of the SL model with the CFS-IRA Principles and the SDGs is an effective educational strategy. A clear advantage resides in the governance dimension, which was consistently the highest-rated, demonstrating a strong institutional commitment to transparency and organizational management. Furthermore, as evidenced by the decade-long experience, the implementation of this model has succeeded in strengthening students’ technical, social, and ethical competencies, and related projects have demonstrated progressive expansion.

Consequently, future lines of research should aim to strengthen the social and environmental dimensions, systematically addressing their inherent challenges. Such work could build upon existing technological projects, such as the GIS tool for calculating the carbon footprint, and upon community impact strategies that enhance inclusion and learning in alignment with Sustainable Development Goal 4. Finally, it is recommended to focus on assessing the replicability of the SL model in other higher education institutions and on designing interventions that ensure a coherent balance among the four dimensions to generate transformative impacts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.N.C. and I.J.F.E.; Methodology: P.N.C. and I.J.F.E.; Validation: P.N.C., I.J.F.E., G.A. and C.Z.; Formal analysis: P.N.C. and I.J.F.E.; Investigation: P.N.C., I.J.F.E., G.A. and C.Z.; Resources: P.N.C. and I.J.F.E.; Data curation: P.N.C., I.J.F.E., G.A. and C.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation: P.N.C. and I.J.F.E.; Writing—review and editing: P.N.C., I.J.F.E., G.A. and C.Z.; Visualization: P.N.C., I.J.F.E., G.A. and C.Z.; Supervision: P.N.C. and I.J.F.E.; Project administration: P.N.C.; Funding acquisition: P.N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the collaboration agreement between the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM), within the framework of the project for the implementation of the CSA-RAI Principles in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spain, and by the Food Bank Chair of the Polytechnic University of Madrid.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it did not involve human participants or animals, and no personal data were collected. The Ethics Committee of the Polytechnic University of Madrid and the GESPLAN Research Group reviewed the documentation for this study and concluded that as no personal information from participants was used, the project did not require institutional ethical approval or review. Therefore, a formal waiver was granted.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data regarding the results of this research study are available.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the GESPLAN Research Group and the RU-RAI University Network, whose collaboration and contributions were essential to the development of this study. The authors also wish to thank FESBAL (Federación Española de Bancos de Alimentos) for its openness and for providing the opportunity to work collaboratively. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Consensus and SciSpace to assist in research synthesis and verification. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the final content of this publication. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the GESPLAN Research Group and the RU-RAI university network, whose collaboration and contributions were essential to the development of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sibbel, A. Pathways towards Sustainability Through Higher Education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2009, 10, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žalėnienė, I.; Pereira, P. Higher Education for Sustainability: A Global Perspective. Geogr. Sustain. 2021, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Footprint Network. Earth Overshoot Day 2024 Approaching. Available online: https://www.overshootday.org/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Hunger Numbers Stubbornly High for Three Consecutive Years as Global Crises Deepen: UN Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/24-07-2024-hunger-numbers-stubbornly-high-for-three-consecutive-years-as-global-crises-deepen--un-report (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- United Nations Environment Program. Food Waste Index Report 2024: Think Eat Save—Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste. 2024. Available online: https://sdg2advocacyhub.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/food_waste_index_report_2024.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPA). The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food Allocates an Additional 100 Million in Direct Aid from the CAP. 2025. Available online: https://www.tridge.com/ko/news/the-ministry-of-agriculture-allocates-an-add-dripwq (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Buzby, J.C.; Hyman, J. Total and Per Capita Value of Food Loss in the United States. Food Policy 2012, 37, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, C.; Stoessel, F.; Baier, U.; Hellweg, S. Quantifying Food Losses and the Potential for Reduction in Switzerland. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M. Recycling, Recovering and Preventing “Food Waste”: Competing Solutions for Food Systems Sustainability in the United States and France. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Salvia, A.L.; Frankenberger, F.; Akib, N.A.M.; Sen, S.K.; Sivapalan, S.; Novo-Corti, I.; Venkatesan, M.; Emblen-Perry, K. Governance and Sustainable Development at Higher Education Institutions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 6002–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B. Benefits of Volunteerism: From Extracurricular to Service Learning and Beyond. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2024, 43, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Secondi, L.; Pratesi, C.A. Reducing Food Waste: An Investigation on the Behaviour of Italian Youths. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun Kim, J. A Hyperlink and Semantic Network Analysis of the Triple Helix (University-Government-Industry): The Interorganizational Communication Structure of Nanotechnology. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2012, 17, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrán Jorge, M.; Herrera Madueño, J.; Calzado, Y.; Andrades, J. A Proposal for Measuring Sustainability in Universities: A Case Study of Spain. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 671–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, P.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, A. Does Food Sharing Lead to Food Waste Reduction? An Experimental Analysis to Assess Challenges and Opportunities of a New Consumption Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Carmenado, I.D.L.; Mereles, M.L.A.; Deza, X.N.D.L. Connecting Sustainable Rural Development Projects and Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems from WWP Model: Lessons from Case Studies in Seven Countries. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2025090058. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Zurita, D.; Jaya-Montalvo, M.; Moreira-Arboleda, J.; Raya-Diez, E.; Carrión-Mero, P. Sustainable Development through Service Learning and Community Engagement in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 26, 158–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburuzabala, P.; Cerrillo, R. Service-Learning as an Approach to Educating for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molderez, I.; Fonseca, E. The Efficacy of Real-World Experiences and Service Learning for Fostering Competences for Sustainable Development in Higher Education. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4397–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, F.; Prianto, A.; Munawaroh, M.; Timan, A. Does Service-Based Learning Strengthen Students’ Basic Skills? Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2024, 23, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A. Do Universities Contribute to Sustainable Development? Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2019, 4, em0112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Huamán Cristóbal, A.E. The CFS-IRA Principles as Instruments for the Management of Rural Development Projects: The Case of the Central Highlands of Peru. In Proceedings of the 26th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Terrassa, Spain, 5–8 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Revilla-Cuesta, V.; Skaf, M.; Gentle-Black, J.; San-José, J.; Ortega-López, V. Train Future Agricultural Engineers at the University of Burgos, Spain, through a Service-Learning Project on Rural Depopulation and its Social Consequences. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Sánchez, A.; González Gómez, D.; Jeong, J.S. Service-Learning in the Education System: Evaluation of the Degree of Implementation as a Tool to Work on Education for Sustainability. Apex. J. Sci. Educ. 2024, 8, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersz, D.; Olaru, D. Why Do Students Differ in the Value They Place on Pro-Social Activities? J. Sociol. 2013, 51, 1017–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenier, K.A.; Englebretson, E.; James-Barry, J.A.; Rigsby, A.N.; Rodolfich, A.E.; McQueen, E.P.; Sparks, E.L. Development of a Community-Driven Waste Reduction Education and Action Program. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Heredia, N.; Corral-Robles, S.; González-Gijón, G.; Sánchez-Martín, M. Exploring Inequality Through Service Learning in Higher Education: A Bibliometric Review Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 826341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, N.P. Project Learn: Supporting On-Campus Learning with On-Line Technologies. Interact. Learn. Environ. 1999, 7, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, S. Service Learning: A Guide to Planning, Implementing, and Assessing Student Projects; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9781483364216. [Google Scholar]

- Boru, N. The Effects of Service Learning and Volunteerism Activities on University Students in Turkey. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2017, 5, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronick; Robert, F.; Robert, B.C.; Michele, G. Experiencing Service-Learning; ProQuest Ebook Central; University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salam, M.; Awang Iskandar, D.N.; Ibrahim, D.H.A.; Farooq, M.S. Service Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 20, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, K. Real and Relevant: A Guide for Service and Project-Based Learning; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E.; Kayser, C.; Wallace, M.; Bosnake, A. Soar into STEMed: Examining the Impact of a Service-Learning Internship on a Pre-Service Teacher’s Conceptions of Culturally Responsive Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.M.; Notah, D.J. Service Learning: History, Literature Review, and a Pilot Study of Eighth Graders. Elem. Sch. J. 1999, 99, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, M.E.; Gallagher, L.A. Service-Learning: A History of Systems. In Learning to Serve: Promoting Civil Society Through Service Learning; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, L.; Escofet, A. Service-Learning (SL): Keys to Its Development at University; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, B. Partnerships for Service Learning. New Dir. Stud. Serv. 1999, 1999, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, R. What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Service-Learning? Rev. Reflect. Calmly Unravels Knots 2011, 972, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bringle, R.G.; Hatcher, J.A. Implementing Service Learning in Higher Education. J. High. Educ. 1996, 67, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyler, J.; Giles, D.E., Jr. Where’s the Learning in Service-Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-7879-4687-1. [Google Scholar]

- Astin, A.W.; Sax, L.J. How Undergraduates Are Affected by Service Participation. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1998, 39, 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, B. (Ed.) Service-Learning in Higher Education: Concepts and Practices; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-7879-0275-4. [Google Scholar]

- Naufal, W.N.A.D.M.; Aris, S.R.S.; Wahi, R. Key Success Factors for Implementation of Service-Learning Malaysia University for Society (SULAM) Projects at Higher Education Level: Community Perspectives. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2024, 20, 152–172. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, B.J.L.; Ledo, A.A.F.M.; Pazos, M.D.C.M.; Jiménez, S.S.; Chávez, V.R.; Castillo, M.Q. Community Social Service: Students Away from the Classroom Building Knowledge in Their Communities. J. Serv. Sci. Res. 2017, 5, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bruce-Davis, M.N.; Gubbins, E.J.; Gilson, C.M.; Villanueva, M.; Foreman, J.L.; Rubenstein, L.D. STEM High School Research Experiences: Impact on Gifted Students’ Science Process Skills and Interest in STEM Careers. Gift. Child Q. 2012, 56, 3–23. Available online: https://nrcgt.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/953/2015/04/STEM_eBook.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Biedermann, A.; Muñoz López, N.; Serrano Tierz, A. Developing Students’ Skills through Real Projects and Service Learning Methodology. In Advances on Mechanics, Design Engineering and Manufacturing; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Ríos, I.; Cazorla, A.; Díaz-Puente, J.M.; Yagüe, J.L. Project-Based Learning in Engineering Higher Education: Two Decades of Teaching Competences in Real Environments. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Afonso Gallegos, A.; Quintanero Lahoz, S.; Ortega Rincón, R.; Nole Correa, P.; Zuluaga, C.; Roncancio Burgos, M. FESBAL-UPM Food Bank Chair and the Service-Learning Projects from the ‘Working with People’ Perspective. In Crisis After the Crisis: Economic Development in the New Normal; Chivu, L., De Los Ríos Carmenado, I., Andrei, J.V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 79–90. ISBN 978-3-031-30995-3. [Google Scholar]

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Renzulli, P.A.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Environmental Impacts of Food Consumption in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, D.; Stadler, K.; Steen-Olsen, K.; Wood, R.; Vita, G.; Tukker, A.; Hertwich, E.G. Environmental Impact Assessment of Household Consumption. J. Ind. Ecol. 2016, 20, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour: An Integrative Review and Research Agenda. J. Approx. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Curtis, J. Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviours: A Review of Methods and Approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesler, M.; Veresiu, E. Creating the Responsible Consumer: Moralistic Governance Regimes and Consumer Subjectivity. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, E. Experiential Responsible Consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.E.; Yildirim, P. Understanding Food Waste Behavior: The Role of Morals, Habits and Knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out Food Waste Behaviour: A Survey on the Motivators and Barriers of Self-Reported Amounts of Food Waste in Households. J. Approx. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinie, A.-C. Challenges for Reducing Food Waste. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2020, 14, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Consumer Behavior: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrieska, S.K.E. Understaning Children As Consumers. TIJ’s Res. J. Soc. Sci. Manag.-RJSSM 2017, 6, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, L.; Bynner, J.; Duckworth, K. Young People’s Leisure Contexts and Their Relation to Adult Outcomes. J. Youth Stud. 2006, 9, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, I.; Üniversitesi, S.M.; Yüce, K.; Üniversitesi, K.M.; Tunçel, Ö.; Firat, A.; Kutucuoğlu, K.Y.; Saltik, I.A. Consumption, Consumer Culture And Consumer Society. J. Community Posit. 2013, 13, 182–203. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, R.R. Changing an Organization’s Culture Under New Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 25, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Byker Shanks, C.; Lewis, M.; Leitch, A.; Spencer, C.; Smith, E.M.; Hess, D. Meeting the Food Waste Challenge in Higher Education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 1075–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerke, A.; Straatmann, T.; Lin-Hi, N.; Müller, K. Consumer Awareness and Sustainability-Focused Value Orientation as Motivating Factors of Responsible Consumer Behavior. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2017, 11, 959–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Transforming Our World. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 (A/RES/70/1); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. FAO and the Sustainable Development Goals: Achieving the 2030 Agenda Through Empowerment of Local Communities; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Negrillo Deza, X.; Montero, A.C. The Ira Principles as a Basis For Research Between Universities and Companies. Available online: https://www.unae.edu.py/ojs/index.php/facem/article/view/357 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Requelme, N.; Afonso, A. The Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture (CFS-RAI) and SDG 2 and SDG 12 in Agricultural Policies: Case Study of Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta Mereles, M.L.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Ávila Cerón, C.A.; Castañeda Sepulveda, R. Responsible Investment in the Processes of Substitution of Illicit Crops from the “Working with People” Model: Case Study Guaviare (Colombia). In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spana, 10–13 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Aliaga, R.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Cazorla Montero, A.; Huamán Cristóbal, A.E. Definition of Priority Objectives for the Implementation of the CFS-RAI Principles in the Central Highlands of Peru. In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spana, 10–13 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Federación Española de Bancos de Alimentos (FESBAL). 2025. Available online: https://www.fesbal.org/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- The Global FoodBanking Network. How Food Banks Reduce Food Loss and Waste. Available online: https://www.foodbanking.org/reducing-food-loss-and-waste/ (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- De los Ríos, I.; Cazorla, A.; Sastre, S.; Cadeddu, C. New University-Society Relationships for Rational Consumption and Solidarity: Actions from the Food Banks-UPM Chair. In Envisioning a Future Without Food Waste and Food Poverty; Brill: Leiden, ND, USA, 2018; pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Nole, C.; Leonor, P.; Ccancce, A.; Los Ríos, I. Service Learning Projects for Responsible Consumption: 10 Years of Experience from the Food Bank Chair UPM. In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spana, 10–13 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso, A.; Sastre, S. Good Practices for Food Bank Management: Experience Capitalization; Food Bank-UPM Chair; Polytechnic University of Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Uceda, G.; De Afonso, A.; De los Ríos, I. Challenges Facing the Post-2020 Horizon: The New Approach of Food Banks in Spain; Food Bank Chair; Polytechnic University of Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, M.; Alfonso, A.; De los Ríos, I. Food Waste in School Cafeterias: Quantification and Identification of Possible Conditioning Factors. Granja: Rev. Cienc. Vida 2018, 28, 20–42. [Google Scholar]

- Roncancio Burgos, M.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Zuluaga, C. The SIG Applied in the Management of Projects for Awareness in Responsible Consumption. In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 12–14 July 2023; AEIPRO: Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Farías Estrada, I.J.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I. Carbon Footprint of Food Banks: Conceptual Framework and Review of Experiences. 2023. Available online: https://portalcientifico.upm.es/es/ipublic/item/10136003 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Farías Estrada, I.J.; De los Ríos, I.; Velilla, C.; Marín Ferrer, C. GIS as a Tool for Calculating the Carbon Footprint of Food Banks. 2024. Available online: https://portalcientifico.upm.es/es/ipublic/item/10307256 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- De Los Ríos, I.; Rodríguez, F.; Pérez, C. Promoting Professional Project Management Skills in Engineering Higher Education: Project-Based Learning (PBL) Strategy. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2015, 31, 184–198. [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo-Narváez, A.; de los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Pastor-Fernández, A.; Blanco, J.L.Y.; Otero-Mateo, M. Project Management Competences and Sustainable Development in Higher Education: Case Studies from Two Spanish Public Universities. preprints.org. 2018. Available online: https://www.preprints.org/frontend/manuscript/9dfdc50ea54eb817c191477c9380c242/download_pub (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Stratta Fernández, R.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; López González, M. Developing Competencies for Rural Development Project Management through Local Action Groups: The Punta Indio (Argentina) Experience. In International Development; Appiah-Opoku, S., Ed.; In tech Open: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Sastre-Merino, S.; Díaz Lantada, A.; García-Martín, J.; Nole, P.; Pérez-Martínez, J.E. Building World Class Universities through Innovative Teaching Governance. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2021, 70, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on World Food Security (CFS). Principles for Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), World Food Program (WFP), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD): Rome, Italy, 2014; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-au866s.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Afonso, A. Principles for a Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land: Links with University; Working Paper 2018/1; GESPLAN Research Group Polytechnic University of Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, S.A. Service Learning as an Opportunity for Personal and Social Transformation. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2009, 21, 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Mur Nuño, C.; De Los Ríos, I.; Mejía, J.; Nole, P. Good Governance Practices in Food Banks: ESG Criteria from the APS-WWP Model; University of Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Caspersz, D.; Olaru, D. The Value of Service-Learning: The Student Perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos Carmenado, I.; Carlos, M.N.; Inclusive, C. Transparent Governance Structures from IRA Principles. Case FESBAL “Food Bank”. In Proceedings of the 27th International Congress on Project Management and Engineering, Donostia-San Sebastian, Spain, 10–13 July 2023; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- López, M.A.R. European Higher Education Area-Driven Educational Innovation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2017, 237, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, L.M.J. Circular-Spiral Economy: Transition to a Closed Economic Metabolism; Ecobook: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]