Abstract

This study addresses the challenge of aligning inventory forecasting with sustainability and service level goals in re-order point systems. It introduces a semiparametric forecasting method based on exponential smoothing and M-estimation, designed to directly model reorder levels under fill rate (P2) constraints. The proposed approach is benchmarked against state-of-the-art techniques, including Generalized Autoregressive Score (GAS) models, volatility-adjusted smoothing, and DeepAR—a deep learning model for probabilistic time series forecasting. Using monthly demand data from the M3 competition, empirical evaluation demonstrates that the semiparametric method achieves high service level accuracy with low inventory and logistics costs, particularly under short lead times. DeepAR shows strong performance in minimizing inventory levels but tends to underestimate stock requirements under high service level targets. A hybrid strategy combining forecasts from multiple models proves robust across scenarios, reducing forecast risk. The findings highlight the potential of integrating traditional statistical methods with AI-based approaches to support resource-efficient inventory management. By minimizing excess stock and backorders, the proposed methods contribute to reducing environmental impact, offering practical solutions for organizations seeking to balance operational efficiency with sustainability.

1. Introduction

Forecasting in economics and business means foreseeing future events and levels of variables for the purpose of minimizing risk in economic decision-making [1]. It is understood as a formalized approach to formulate predictions about the future state of affairs, which can be verified empirically, but remain uncertain at the time of issuing them [2]. Forecasting remains of interest to decision-makers at different levels of the management hierarchy, economic and business analysts, and financial investors alike, being one of their most important and tough activities. In the sustainability context, forecasting, especially using quantitative methods, is crucial for efficient and sustainable usage of resources and the reduction in waste and environmental impact. Combining expert knowledge with automated computational solutions and good quality historical data enables decision-makers to achieve substantial economic and environmental benefits. For example, solar irradiance and wind speed forecasting are critical for planning renewable energy production, whereas traffic flow forecasting makes it possible to implement smart transport systems to support sustainable urban mobility [3,4].

Demand forecasting in supply chains is a starting point and a basis for supply chain planning and operations management in the short, medium, and long run [5] and should be considered a key component of the logistic support system of an enterprise [6,7]. In fact, this is the demand uncertainty which makes supply chain management so challenging in practice and which directly translates into supply chain costs and benefits. For this reason, forecast precision in so-called supply chain forecasting is the key determinant of future cash flows of supply chain partners [7]. It also has a direct impact on sustainability by reducing overproduction and waste, improving resource utilization, lowering inventory levels, and enhancing the efficiency of logistics operations [8]. The recent surge of the use of business analytics and expansive datasets from information systems such as ERP and CRM has further elevated the importance of forecasting in the business context [9,10]. Recent developments in machine learning and deep learning have introduced novel approaches to inventory forecasting. Models such as DeepAR [11], which utilize autoregressive recurrent neural networks, have shown promising results in capturing complex temporal dependencies and probabilistic patterns in demand data [12]. These methods complement traditional econometric approaches and offer enhanced flexibility, especially in environments with large datasets and nonlinear dynamics [13].

Next to popular precision measures, the quality of supply chain forecasts has traditionally been examined from the point of view of their influence on customer service performance and inventory turns (for example, [7,14]). The most frequently used customer service measure is the so-called P2 or fill rate service measure, defined as the fraction of orders fulfilled directly from the available stock, which is widely used in distribution systems [15,16]. The quantities derived from demand forecasts which define the inventory levels needed to calibrate an inventory system are called inventory forecasts (for example [17]). In addition to realized customer service levels, the quality of such forecasts is assessed using a range of economic indicators, including metrics relevant from a sustainability perspective, such as mean inventory levels, average backorders, wastage rates, and total logistics costs. The latter quantity can be either defined explicitly or given in a form implied by the forecasting problem at hand and can be presented either in absolute or relative terms [16,18]. The formulation of such a cost function enables considering inventory forecasts within the so-called decision-theoretic framework (for example [19]).

In the decision-theoretic forecasting and forecast evaluation, it is suggested that forecast precision should be defined taking into account the costs/benefits which the forecast incurs/brings when used by the decision-maker. Since forecasts are developed with specific economic and sustainability objectives in mind, their quality can be assessed based on the extent to which the realized outcomes align with these goals, particularly in terms of economic efficiency, operational effectiveness, and (economic and environmental) costs and benefits. As a result, decision-theoretic forecasting builds decision models into econometric analysis and/or forecasting algorithms for the purpose of ensuring “planning benefits” [20]. The optimal forecast is defined as that found using the Bayes rule, i.e., through the minimization of the expected loss/cost [21]. Only defining the forecast loss/cost function a priori will facilitate the proper evaluation of forecasts [19]. If the optimal forecast is defined more directly in the form of a given statistical functional (i.e., a distributional characteristic), such as mean or quantile, it is crucial to associate with this functional a strictly consistent loss function, i.e., a loss function that is uniquely minimized in expectation at this functional [21]. With consistent loss functions, a well-specified and more precisely estimated forecasting model based on a larger information set should on average outperform a mispecified one, estimated with less precision, and grounded on a narrower information set [22,23,24]. This approach avoids using ad hoc combinations of economic criteria and efficiency curves in forecast evaluations, which can be highly misleading. In addition, a consistent loss function can also be utilized in computing the forecasts of interest to the decision-maker through the so-called loss function-based estimation, also known as M-estimation, where M-estimation is an abbreviation of the term ‘maximum likelihood like estimation’ [25].

In this paper, we take a similar viewpoint and develop an inventory forecasting algorithm which uses M-estimation to directly model the inventory level used in an inventory system. This algorithm adapts the popular exponential smoothing model to inventory forecasting in the periodic review re-order point inventory system with fixed order quantities, non-negative lead times, and a P2 service level target, building on the previous work of one of the authors, where the inventory context was different [18,26]. In an empirical exercise, the model is confronted with state-of-the-art alternatives such as, among others, the Generalized Autoregressive Score (GAS) model and the algorithm assuming separate smoothing of mean and variance, providing very promising outcomes. Finally, the presented approaches are compared with the deep learning probabilistic model DeepAR [11], which enables one to create distributional forecasts of multiple time series. Hence, this study addresses a notable gap in the literature: while DeepAR has been widely applied in general time series forecasting, its use in modeling reorder points under fill rate constraints remains unexplored. Ref. [27] propose a data-driven framework that leverages large datasets to improve demand estimation and inventory optimization in the context of the newsvendor problem using fully connected feed-forward Artificial Neural Networks with a single hidden layer, Gradient Boosted Decision Trees, and quantile regression techniques. Their empirical evaluation, conducted on point-of-sales data from a German bakery chain, reveals that data-driven methods generally outperform traditional model-based approaches, especially when sufficient data is available. Furthermore ref. [28] use LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) and group LASSO in the data-driven newsvendor models to optimize the demand estimation and replenishment decisions by extracting key features from high-dimensional and mixed-frequency data.

Integrating DeepAR into a comparative framework alongside semiparametric and econometric methods enables us to evaluate its practical relevance and limitations in inventory forecasting. By doing so, the paper contributes to bridging the methodological divide between traditional inventory models and emerging deep learning approaches [17].

2. The Inventory Problem and a New Solution to It

The inventory policy considered in this paper is the periodic review re-order point (T, r, Q) policy with complete backordering and the review period T = 1. r and Q are, respectively, the re-order point, which can be updated at the end of each review period, and the order quantity, which is assumed to be fixed [29]. According to such a policy, the inventory level is controlled at the end of each review period, and if it drops below r, a new order of size Q is placed. The order arrives after L time units (L = 0, 1, 2, …), and, thus, the protection interval is of length L + 1.

We assume further that the re-order level for the period t, rt, is established using a P2 service measure requirement, i.e., it is solved from:

where is the assumed fill rate (P2) service level, is the demand in period t, is the information set available to the forecaster at the time of computing the inventory forecast, and as well as (see, for example, ref. [30], for the case of the continuous review (r, Q) policy, and compare [16] for a similar dynamic formulation for the (T,S) inventory policy). If it holds that , which will take place if the order quantity is large, the assumed service level is high, and the variability of the demand over the protection interval is low, the fill rate Equation (1) simplifies as follows:

Let us assume that the data generating process for the demand corresponds to the simple exponential smoothing model with Gaussian innovations, i.e.,

where is the conditional mean value of , is the smoothing constant, and the error terms are independent. Let us denote by the demand over the protection interval, i.e., . Then, it holds that, conditionally on , , where and denotes the variance of the process of the form:

equal to:

Thus, Equation (2) can be rewritten as:

where and is the standard normal loss function ( and are the standard normal cumulative distribution function and probability density function, respectively). From (5), the solution to (2) takes the form:

and, using the notations and , can also be written as:

Taking into account the model (3), the above formula can be restated as:

Equation (8) shows the updating mechanism in the computation of the re-order level using the previous inventory forecast and the latest demand signal. Note that, through appropriately defining the function , the Formula (8) can also be used if the Gaussian assumption is not fulfilled, whereas under Gaussianity we can express as .

Moreover, if the function is not known, the inventory manager is advised to use the M-estimation principle, to jointly semiparametrically estimate the parameters and . It is assumed that the error term in (3) is heteroskedastic, and thus the smoothing constant α may depend on the target service level β (compare [18]). The required estimates are obtained as two- dimensional minimizers of , with the loss function defined as:

where and is the usual indicator function [26]. The linear-quadratic loss function (9) is associated with the inventory forecast of interest in this paper (i.e., it is strictly consistent for this forecast) and possesses the following properties: it implies linear holding costs and quadratic shortage costs, it is non-negative, and it takes the value of zero if and only if the backorder level is equal to . (For the statistical consistency of this estimator, the data vector needs to fulfill certain moment and dependence assumptions, such as those formulated in the regularity conditions of Theorem A-4 in [10].) Note that, if the service level was defined as the usual P1 or, in other words, the cycle service level (the probability of not stocking out during the inventory cycle), the appropriate loss function in semiparametric estimation would be the standard quantile loss function of the form , where is the assumed cycle service level.

The computational procedure in the form of a spreadsheet is presented in Appendix B.

It is worth noting that the assumption used in calculations can be further relaxed. Namely, keeping the service level formula in the form of Equation (1) and assuming the same Gaussian data generating process as before, we can rewrite the Formula (1) to the form:

In contrary to (5), the formula above does not lead to a solution given explicitly, enforcing the use of numerical simulation to find the optimal value of . In a nonparametric setting, this solution can be obtained through minimization of an appropriately defined loss function. The required extended version of the loss function has the following form:

However, in the following part we will exclusively consider the scenario realized under Equation (2).

3. Chosen Alternative Forecasting Strategies

In our empirical evaluation in the next section, the two forecasting strategies outlined above are supplemented with further three forecasting approaches, namely, the semiparametric GAS models suggested by [31], the two-step approach without distributional assumptions (i.e., first computing the mean value forecast, and then finding the final inventory forecast applying the loss function (9) to a bootstrapped demand distribution generated by adding the mean value forecast to the aggregated random error (4)), and smoothing both the level of the data and its variance assuming that the standardized residuals are Gaussian (for example [32]).

The GAS models have been introduced by [33,34] and developed further by [24] as a family of recursive dynamic models including a rescaled derivative of the loss function from estimation as an explanatory variable. In [24], the idea of [31] has been applied to inventory forecasting in periodic review (T, S) systems, leading to very promising outcomes. In this paper, we use a similar strategy and include in our forecast competition the following GAS-type model of orders (1,1):

where

is the rescaled score of the loss function used in estimation and is a certain scaling factor, which is set here to one.

To forecast the demand volatility, several strategies have been suggested, including simple exponential smoothing of squared error terms (for example [32]) or, alternatively, errors in absolute terms (for example [35]) and using the GARCH(1,1) equation estimated jointly with an equation for the mean [36]. Since our focus here is on adapting simple exponential smoothing to a specific inventory forecasting task, we chose the first approach and, in our next forecasting strategy, we modified the model (3) as follows:

Thus, our model for the conditional variance is the usual simple exponential smoothing equation for forecasting the mean squared error (MSE), which is equivalent to the so-called IGARCH(1,1) model, where IGARCH stands for Integrated Generalized Autoregressive Conditionally Heteroskedastic. Note, however, that here, in accordance with the common practice in the logistics industry, the smoothing constants α and β are estimated separately using the least squares method.

To find inventory forecasts in the case of positive lead times L, we use the simulation approach, which, in the presence of an equation for the conditional volatility, becomes indispensable even assuming Gaussian standardized residuals (compare [36]). Because of this, the demand distribution needs to be simulated using random draws from the standard normal distribution, and thus—to find the inventory forecast—similar to the two-step approach without distributional assumptions, the loss function (9) is applied on residuals computed using the simulated demand distribution. (Such a simulation approach is also known as parametric bootstrap, whereas the strategy which does not use distributional assumptions and is based on drawing with replacement from (standardized) residuals is known as nonparametric bootstrap).

The DeepAR model is a probabilistic method for time series forecasting based on autoregressive recurrent neural networks (RNNs), originally proposed by [11]. In this study, model architecture is based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, which are capable of modeling long-range dependencies in sequential data. The primary objective of the model is to generate accurate forecasts for multiple related time series by learning their shared structure. Unlike traditional approaches that train separate models for each individual series, DeepAR employs a global training strategy, enabling it to capture common patterns and dependencies across series—even when they are short or noisy. We use this model in this study as a reference point to evaluate the performance of traditional and semiparametric forecasting strategies due to the growing interest in deep learning approaches for inventory management. While DeepAR is not integrated with the classical models presented, its probabilistic forecasts allow for a meaningful comparison under identical service level constraints. This comparative setup enables the assessment of whether deep learning offers tangible advantages over established methods in practical inventory settings.

The model operates in an autoregressive manner, meaning that each predicted value depends on previous observations. At each time step, the model receives as input the previous value of the series along with optional covariates. The architecture based on multiple LSTM networks allows the model to capture long-term temporal dependencies. The hidden state is updated according to the following recurrence:

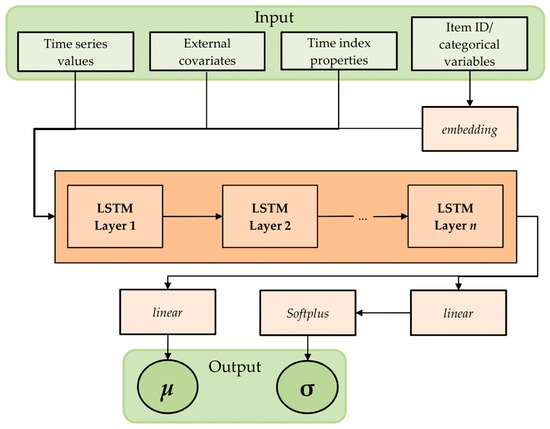

As it is highlighted in [11], one of the biggest advantages over the classical approaches are the ability to learn seasonal behavior and dependencies on given covariates across time series, and providing forecasts for items with little or no history, if only data for similar products is available. Furthermore, minimal manual feature engineering is needed to capture complex behavior and dependencies between items or groups. The architecture of the model is presented on Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the DeepAR architecture.

DeepAR has been applied in a variety of domains, including demand forecasting in retail, inventory management, energy consumption prediction, and financial analysis. For instance, ref. [37] conducted a comparative study of demand forecasting methods, including deep learning models such as DeepAR, in the context of quarterly product demand in the retail sector. Their findings demonstrated that DeepAR can effectively support inventory-level decisions and help prevent stockouts.

In the financial domain, DeepAR has been identified as a valuable tool for forecasting financial time series such as stock prices, exchange rates, and macroeconomic indicators [12]. Its ability to generate probabilistic forecasts makes it particularly suitable for risk analysis and uncertainty modeling in finance.

Among its key advantages are high forecasting accuracy due to global training, the ability to incorporate external covariates, and the generation of probabilistic outputs. However, one limitation is the requirement for a large number of related time series, which may hinder its applicability in univariate settings. The model’s performance in such cases has been critically evaluated in [13], highlighting its limitations when applied to a single time series.

4. Empirical Illustration

To evaluate the strategy proposed in this study, the six methods discussed were employed to generate forecasts based on the M3 forecasting competition dataset [38]. It has been extensively used in academic research and practical applications to compare traditional statistical models with more recent machine learning and hybrid approaches [39,40,41]. More precisely, we selected monthly demand data which are described as shipments. The general data preprocessing process was split into two main parts. First, the longest time series were selected to ensure the competitiveness of semiparametric methods. For the purpose of the experiment, a dataset comprising 197 time series of 126 months in length was prepared. Subsequently, the time series were verified for compliance with the following assumptions:

- E(DL+1) ≥ E(DL+1 − r)+ = Q(1 − β);

- E(DL+1) ≤ Q;

- Q/E(D1) (average length of the inventory cycle) facilitates the enterprise’s adaptability to market dynamics;

- P(DL+1> Q + r)~0,

where D1 and DL+1 are the random variables distributed as the demand in a single period and in the protection interval.

These conditions determine the selection of the parameter Q for a service levels β relevant to the decision-maker. On the one hand, the value of Q must not be too low, so that inventory levels can satisfy demand within the lead time (condition 2), while accounting for its variability (condition 4). On the other hand, Q must not be excessively high, as too long inventory cycles will cause the enterprise to suffer from the physical and technological obsolescence of inventories. In our numerical experimentation, we assumed that the average cycle length cannot exceed 12 months. Nevertheless, condition 1 indicates that, particularly for high service levels, the potential range of the resulting parameter Q is broad.

Note that choosing the appropriate order quantities requires in practice having good estimates of enterprise unit inventory, ordering, and shortage costs. If the latter type of cost is not available, the inventory manager usually resorts to the modified Economic Order Quantity formula in which the demand is replaced with its mean value over a certain time interval. In the absence of the appropriate cost information, we choose Q such that the technical assumptions (1)–(4) formulated above are fulfilled for a possibly large number of time series. After some experimentation, the following values were adopted: Q = 25,000 and Q = 50,000. The other model parameters were as follows: L = 0 and L = 1; and β = 0.9, 0.95, 0.975, 0.99, 0.995. The fulfillment of assumptions (1)–(4) was then verified for each configuration. Due to frequent violations of assumption (1) for β = 0.9, this configuration was excluded from further analysis. In the remaining configurations, time series that did not meet the specified requirements were removed. Ultimately, 97 time series were retained for Q = 25,000, and 68 time series for Q = 50,000. For each configuration of Q and L, we created inventory forecasts for the last 39 months (40 months if the lead time was set to one) of each time series. Depending on the selected lead time, we created one- or two-step-ahead forecasts using the expanding window of available historical data. Two-step-ahead forecasts are computed recursively, using the forecasts previously obtained for the first horizon [11]. The number of bootstrap replications for both the parametric and nonparametric bootstrap was set to 500, and the number of randomizations of initial values, applied whenever the loss function (9) was used in estimation, was set to ten.

The described neural networks were built and trained using gluonts library in Python language [42]. Hyperparameters of models were optimized using optuna package [43] for each Q and L combination. Due to the computational costs of the process and the potential requirement of such a procedure for each forecast individually, we were optimizing hyperparameters once before creating the first forecast in each (Q, L) configuration. To create the next forecasts, the same values of hyperparameters were used. The process of hyperparameter tuning was realized by minimizing average overall quantile losses on 10th, 50th and 90th percentile computed on the validation set, created from last 20 observation included in the training process from every time series. At each time step, the model receives as input the previous forecasted value along with a set of covariates. In our implementation, the following covariates were included:

- Lagged demand values: up to three previous observations (lags 1, 2, and 3), allowing the model to capture short-term autocorrelation.

- Seasonal indicators: such as week-of-year and month-of-year, encoded as cyclical features to reflect periodic demand patterns.

- Time index: a normalized linear trend variable representing the time elapsed since the beginning of the series.

- Item identifiers: categorical variables representing individual SKUs, enabling the model to learn item-specific effects within the global framework. This option was left in the default configuration.

To include such covariates, the dataset was preprocessed to the long-type data frame with time index included. Next, these covariates were passed to the model via the PandasDataset.from_long_dataframe() interface, which internally constructs the appropriate feature tensors for each time series. The model was trained separately for different lead times (L = 0, 1), with the prediction length set accordingly. Obtained hyperparameters are presented in the Appendix A, Table A1. Further dependencies between the time series could be included, using an encoder–decoder architecture. In this study, however, it was not employed. Instead, the model was based on a classical autoregressive LSTM structure, where each forecast was conditioned on previous observations and explanatory covariates. Nevertheless, this architecture could be extended to incorporate encoder–decoder components in future research, potentially enhancing its ability to capture complex temporal dependencies.

The applicability of DeepAR is particularly relevant in industries with large volumes of similar products, such as retail, e-commerce, and fast-moving consumer goods. Its global training strategy benefits from shared patterns across multiple SKUs. However, in sectors with limited or highly heterogeneous time series, the model’s performance may degrade. Therefore, contextualization of results by industry type is essential to assess the practical relevance of the proposed forecasts.

The context length was set to 100, ensuring that the model had sufficient historical information to learn temporal dependencies. Although some of the input series were preprocessed to remove seasonal components, seasonal covariates were retained to allow the model to capture residual or interacting seasonal effects. Learning rate and activation functions were kept on their default values defined in DeepAREstimator() class in gluonts package.

It is important to note that DeepAR, as implemented here, is a global model with local adaptation. While a single model is trained across all series, the inclusion of item-specific covariates allows it to learn individualized patterns. This hybrid structure aligns with the original design of DeepAR by Amazon, which combines the strengths of both global and local modeling approaches.

The final forecasts were generated recursively (using samples expanded by one observation) for each time series with models’ re-estimation on expanding windows, and the resulting predictive distributions were used to compute inventory levels under the P2 service level constraint. The computational cost of training the DeepAR model was non-negligible, with each configuration requiring approximately 15 min on a standard PC, including hyperparameter tuning and density estimation.

All further computations were performed in Matlab© using the function fmincon for constrained optimization and iterating until convergence between the functions fminsearch and fminunc in the case of unconstrained optimization.

The results of the forecast competition, evaluated using selected metrics for inventory prediction accuracy, are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Models were evaluated using the following metrics:

Table 1.

Performance measures for the scenario with Q = 25,000. Two best results in columns for each (β, L) pair are bolded.

Table 2.

Performance measures for the scenario with Q = 50,000. Two best results in columns for each (β, L) pair are bolded.

- Mean inventory at the end of the inventory cycle (expressed per unit of demand in the protection interval), describing the tendency of the model to overstocking in each inventory cycle.

- Mean empirical fill rate level (FR) obtained in the forecasted period, computed using the expression in the right-hand side of Equation (2).

- Mean cost, defined as the value of the cost function assumed in the estimation, which we treat as proportional to the logistics cost incurred in the interval between two order placements (again expressed per unit of demand)

- Mean ranking of the model in terms of costs, defined in point 3, computed by the forecasted values and associated reorder points for each time series. The higher the place in the ranking, the smaller costs obtained for the method.

- Mean ranking of the inventory level for each time series. The placement is consistent with the cost ranking.

For clarity, we report outcomes only for service levels corresponding to β = 0.975 and β = 0.99. All the results obtained are available in the Supplementary Material. The forecasting methods are defined as follows:

- Method I assumes data generation according to model (3),

- Method II relies on joint parameter estimation in Equation (8),

- Method III employs the GAS(1,1) model,

- Method IV utilizes distributional forecasts generated via DeepAR,

- Method V applies a two-step procedure without distributional assumptions,

- Method VI is based on model (11),

- Method VII presents outcomes obtained using the average of forecasts produced by Methods I–VI.

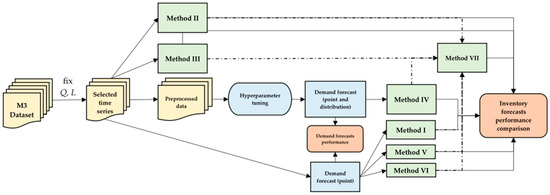

The procedure conducted in this example is visualized on Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the experiment.

For each evaluation criterion, the two best-performing methods are highlighted in bold. Under the examined conditions, Method II consistently yields favorable results in terms of empirical fill rate and average inventory per unit of demand in the protection interval, particularly when L = 0. The IGARCH-based approach (Method VI) also demonstrates strong performance, especially with respect to mean cost and fill rate metrics. Notably, the hybrid approach (Method VII) performs well across both inventory and cost dimensions. Its effectiveness is independent from the settings presented in the tables. This, for some of the examined configurations, can be caused by the significantly smaller values of certain evaluation measures obtained by deepAR, which leads to the decreasing in mean values. This behavior, compared with close-to-expected outcome, from the rest of the models, leads to good mean performance in terms of chosen evaluation metrics. It also shows that combining forecasts reduces forecast risk defined as unfavorable values of evaluation metrics.

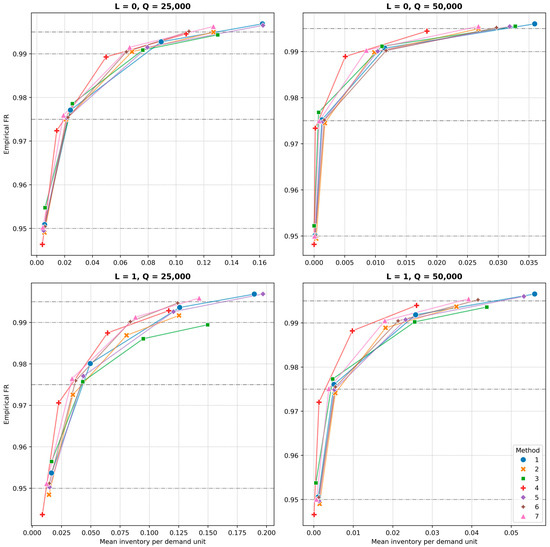

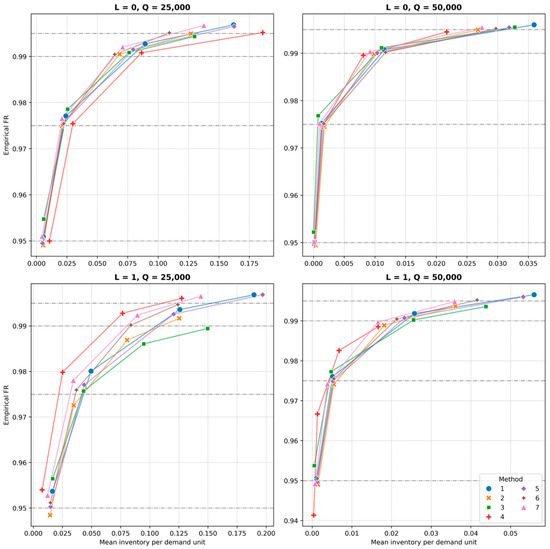

Interestingly, the DeepAR model leads to consistent results between the cases. It results in the lowest values of mean inventory per demand unit and high inventory ranking. On the other hand, the suggested inventory levels are insufficient to meet the targeted service level values. Thus, the mean cost of the model is far from the minimum in many cases. Disproportion between the deepAR and the rest of the methods is visible on Figure 3. We can also observe increasing differences between the performance of each of the models with increasing target service levels. It is especially evident at β = 0.99 and β = 0.995, where the inventory levels required to achieve higher service standards increase substantially [44].

Figure 3.

Efficiency curves of presented methods and configurations.

Further analyzing the efficiency curves plotted in Figure 3 leads to the conclusion that Method VI gives the closest-to-expected values of the P2 measure with the minimal or close to minimal mean inventory level. For L = 0, Method II is competitive in both of these conditions. Performance of the deepAR model is relatively consistent throughout analyzed cases. Overall, good performance of the combined approach (Method VII) is confirmed by the efficiency curves of this approach. Underestimation of the needed inventory by the deepAR model is the counterweight for the larger values of mean inventory levels reached by Methods I and V, which, combined with a smaller difference in the level of service obtained, leads to acceptable forecasts in the form of averages. Results for individual models, or in the comparison of choice, is available in the interactive application under the link: https://sustainability-17-10192.streamlit.app/, (accessed on 11 November 2025). In this dashboard, by selecting the lead time (L), order quality (Q) and models of choice, one can compare performance of any subset of presented methods, with exact values of mean inventory level and empirical fill rate reached.

Sensitivity Analysis on the Hyperparameters of the DeepAR Model

The initial configuration of the DeepAR model was calibrated with respect to the number of layers, cell size, and training epochs. This setup was selected due to its relatively short optimization time and satisfactory performance across evaluation metrics. Nevertheless, the observed underestimation of inventory levels and, consequently, fill rate values prompted an extension of the hyperparameter search space to assess whether improved performance could be achieved.

Subsequent optimization was conducted in accordance with the official Amazon documentation (https://docs.aws.amazon.com/sagemaker/latest/dg/deepar-tuning.html, accessed on 11 November 2025). Given the relatively small size of the dataset, the recommended parameter ranges were narrowed, and step sizes were introduced to reduce the dimensionality of the search space. The complete configuration, including the selected hyperparameters, is provided in Appendix A.

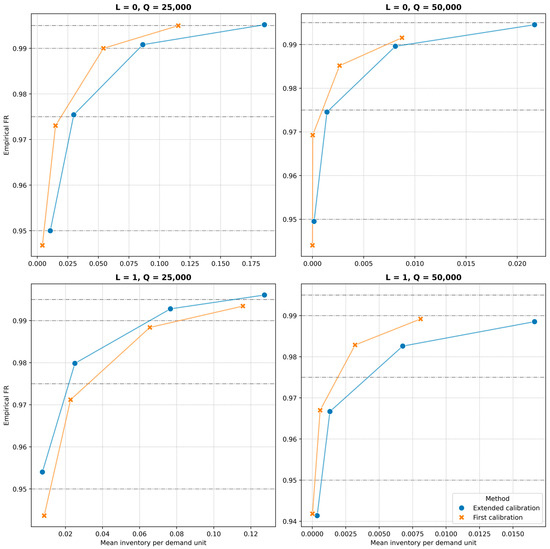

As a result of these modifications, the hyperparameter tuning process was extended to approximately 14 h per (L, Q) configuration—representing a 60-fold increase in computational time. Despite the substantial increase in resource consumption, the outcomes varied across different scenarios. A comparative summary of the results is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Efficiency curves of both DeepAR methods under different configurations.

For L = 0, regardless of the selected Q value, a notable improvement in the model’s ability to meet the target fill rate was observed. However, for Q = 25,000, the inventory levels associated with higher service level targets (P2 = 99% and 99.5%) were significantly lower in the initial model compared to the extended configuration. In contrast, for Q = 50,000, improvements were evident across all evaluated scenarios.

Extending the forecast horizon (L = 1) led to more heterogeneous results, which remained sensitive to the Q parameter. For Q = 25,000, both the mean inventory level and the empirical fill rate increased. Further increases in Q yielded similar fill rate outcomes, suggesting diminishing marginal returns.

These findings indicate that the previously observed inventory underestimations can be mitigated by expanding the hyperparameter space during model tuning. Conversely, increasing the forecast horizon and order quantity—thereby reducing the effective sample size—tends to degrade model performance. This observation aligns with the DeepAR documentation, which states that “The DeepAR algorithm starts to outperform standard methods when the dataset contains hundreds of related time series.” (https://docs.aws.amazon.com/sagemaker/latest/dg/deepar.html#deepar-inputoutput, accessed on 11 November 2025).

Although the computational cost of the extended DeepAR configuration is substantial, the model remains competitive in selected scenarios. Importantly, its performance advantage is expected to grow with the number of available time series, making it a promising candidate for large-scale, data-rich environments where sustainability and efficiency are jointly pursued.

5. Discussion

The comparative evaluation of forecasting methods highlights distinct strengths and limitations across approaches. Method II, based on semiparametric estimation, demonstrates consistent performance in achieving target service levels with low inventory and logistics costs, particularly under short lead times. Its interpretability and computational efficiency make it well-suited for operational contexts with stable demand and extensive historical data.

DeepAR model shows strong inventory minimization capabilities and, independent of L and Q parameters, good performance in terms of metrics of the forecasts error, such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Pinball loss function (reported for quantile 0.25). In the majority of cases, DeepAR outperforms the approach used to create inventory forecasts with Methods I, V, and VI (see Table A3 in Appendix A). Both these results suggest the applicability of this model in the presented framework. However, its tendency to underestimate stock requirements under high service levels suggests sensitivity to demand variability (especially with the lengthening of the forecast horizon) and potential misalignment with service constraints. This behavior can be reduced by expanding the parameters space, under the additional cost of much longer process of hyperparameters tuning. Nevertheless, this procedure does not fix all the formulated issues. These findings underscore the importance of contextual calibration and industry-specific application when deploying deep learning models in inventory forecasting.

The IGARCH-based approach (Method VI) offers balanced performance across scenarios, confirming the value of jointly modeling conditional mean and variance. Although less flexible, Method V provides acceptable results, indicating that simplified procedures can still yield reliable forecasts when properly tuned.

From a sustainability perspective, accurate forecasting contributes to resource-efficient inventory management by reducing overstocking, minimizing backorders, and lowering the environmental footprint of logistics operations [45,46]. These outcomes are particularly relevant for organizations aiming to align operational efficiency with environmental responsibility [8].

The hybrid strategy (Method VII), which combines forecasts from multiple models, demonstrates robustness and adaptability. However, its implementation requires additional computational resources and model maintenance, which may limit its scalability in certain settings.

Future research should focus on:

- Enhancing model interpretability, especially in AI-based approaches.

- Evaluating performance across industry sectors, with attention to product characteristics and demand patterns.

- Integrating sustainability metrics into forecast evaluation, such as emissions, waste reduction, and resource utilization.

- Developing hybrid frameworks that combine statistical rigor with the adaptive power of deep learning.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a comparative analysis of forecasting methods for inventory management under fill rate constraints, with a focus on semiparametric estimation and deep learning. The proposed semiparametric approach (Method II) proves effective in scenarios with short lead times and stable demand, offering high forecast accuracy and low logistics costs. The proposed forecasting model contributes to the reduction in wastage in inventory systems by minimizing overstock and backorders, and, thus, producing tangible ecological benefits. It will constitute an excellent solution for businesses striving for both economic efficiency and environmental responsibility. Given the growing accessibility of ERP and CRM systems, semiparametric approaches such as Method II present a compelling foundation for contemporary inventory forecasting, particularly in operational contexts characterized by stable demand patterns and comprehensive historical sales records. The interpretability, computational efficiency, and empirical robustness of this method make it especially suitable for organizations seeking scalable and transparent forecasting solutions without the overhead of deep learning infrastructure.

DeepAR, while promising in terms of inventory minimization, requires careful calibration to meet service level targets. Its performance varies depending on data structure and industry context, suggesting that deep learning should be applied selectively and with domain-specific adjustments. Proper calibration, although extends the process of training, can lead to improvements in forecasts and inventory values, leading to cost reduction, resource efficiency, and, thus, environmental impact.

The results confirm that combining traditional and modern forecasting techniques can enhance robustness and reduce forecast risk. In particular, hybrid models (Method VII) offer a balanced trade-off between cost efficiency and service reliability.

By linking forecasting precision with resource optimization, the study contributes to the discourse on sustainable supply chain management. The findings support the adoption of forecasting strategies that not only improve economic outcomes but also promote environmental responsibility.

Further research should explore the integration of semiparametric and deep learning models, the inclusion of sustainability indicators, such as energy costs or cost of the reduction in the carbon footprint, in forecast evaluation, and the adaptation of forecasting frameworks to diverse industrial settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172210192/s1, Table S1: Results obtained for the model with Q = 25,000 for the first configuration of deepAR model. Table S2: Results obtained for the model with Q = 50,000 for the first configuration of deepAR model. Table S3: Results obtained for the model with Q = 25,000 for the extended configuration of deepAR model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and J.B.; methodology, J.B. and J.W.; software, J.B. and J.W.; validation, J.W. and J.B.; formal analysis, J.W.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B. and J.W.; writing—review and editing, J.W. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Science Center, Poland, under grant no. 2019/35/O/HS4/00345 (Joanna Bruzda and Jakub Wojtasik).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this research are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Hyperparameters selected for the specific DeepAR model.

Table A1.

Hyperparameters selected for the specific DeepAR model.

| Q | 25,000 | 50,000 | Range, Step | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| number of layers | 6 | 8 | 4 | 5 | [1–10], 1 |

| size of the hidden state | 19 | 19 | 24 | 23 | [10–25], 1 |

| maximum number of epochs | 67 | 42 | 64 | 86 | [25–250], 1 |

Table A2.

Hyperparameters selected for the specific extended DeepAR model.

Table A2.

Hyperparameters selected for the specific extended DeepAR model.

| Q | 25,000 | 50,000 | Range, Step | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| number of layers | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | [1–8], 1 |

| maximum number of epochs | 275 | 425 | 325 | 250 | [25–500], 25 |

| dropout ratio | 0.0344 | 0.1988 | 0.0806 | 0.1515 | [0–0.2] |

| learning rate | 0.0408 | 0.0127 | 0.0160 | 0.0102 | [0.00001–0.1] |

| size of the hidden state | 25 | 40 | 10 | 20 | [10–50], 5 |

| dimension of the embedding vector | 50 | 29 | 35 | 41 | [1–50], 1 |

| batch size | 608 | 224 | 416 | 352 | [32–1024], 32 |

Table A3.

Precision metrics for forecasts obtained by procedure used in parametric and semiparametric methods and DeepAR models. Best performance in each metric is bolded.

Table A3.

Precision metrics for forecasts obtained by procedure used in parametric and semiparametric methods and DeepAR models. Best performance in each metric is bolded.

| L | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | 25,000 | 50,000 | 25,000 | 50,000 | ||||||||

| Metric | MAE | RMSE | Pinball Loss | MAE | RMSE | Pinball Loss | MAE | RMSE | Pinball Loss | MAE | RMSE | Pinball Loss |

| parametric and semiparametric methods | 356.9 | 572.1 | 180.1 | 289.6 | 456.7 | 146.4 | 636.7 | 1006.2 | 326.7 | 500.5 | 791.7 | 257.6 |

| deepAR | 391.3 | 611.8 | 169.2 | 402.4 | 569.3 | 124.5 | 661.0 | 1014.8 | 279.0 | 545.2 | 787.1 | 168.8 |

| extended deepAR | 402.3 | 652.8 | 193.8 | 280.3 | 453.7 | 133.7 | 515.3 | 773.5 | 275.3 | 596.1 | 824.7 | 193.4 |

Figure A1.

Efficiency curves of presented methods with extended approach for Method IV.

Appendix B

Figure A2.

Scheme of spreadsheet computations for the data sample of size n.

References

- Fildes, R.; Goodwin, P.; Lawrence, M.; Nikolopoulos, K. Effective forecasting and judgmental adjustments: An empirical evaluation and strategies for improvement. Int. J. Forecast. 2008, 24, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S. Principles of Forecasting: A Handbook for Researchers and Practitioners; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alguhi, A.A.; Al-Shaalan, A.M. LSTM-Based Prediction of Solar Irradiance and Wind Speed for Renewable Energy Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljabbar, R.; Dia, H.; Liyanage, S. Machine Learning Traffic Flow Prediction Models for Smart and Sustainable Traffic Management. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Meindl, P. Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operations, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, M. Logistics & Supply Chain Management, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Babai, Z.; Boylan, J.E.; Kolassa, S.; Nikolopoulos, K. Supply chain forecasting: Theory, practice, their gap and the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 252, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpitella, S.; Izquierdo, J. Trends in Sustainable Inventory Management Practices in Industry 4.0. Processes 2025, 13, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, J.A.; Dingus, R.; Wilson, J.H. An exploration of sales forecasting: Sales manager and salesperson perspectives. J. Mark. Anal. 2020, 8, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahaggach, H.; Abrouk, L.; Lebon, E. Systematic mapping study of sales forecasting: Methods, trends, and future directions. Forecasting 2024, 6, 502–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, D.; Flunkert, V.; Gasthaus, J. DeepAR: Probabilistic Forecasting with Autoregressive Recurrent Networks. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Ning, K.; Zhang, L.; Marier, S.M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xia, F. Deep learning for time series forecasting: A survey. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cyber. 2025, 16, 5079–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urjais Gomes, R.; Soares, C.; Reis, L.P. An Empirical Evaluation of DeepAR for Univariate Time Series Forecasting. In Progress in Artificial Intelligence. EPIA 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Santos, M.F., Machado, J., Novais, P., Cortez, P., Moreira, P.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 14969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, T.M.; Davis, D.F.; Golicic, S.L.; Mentzer, J.T. The evolution of sales forecasting management: A 20-year longitudinal study of forecasting practices. J. Forecast. 2006, 25, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunter, R.H.; Syntetos, A.A.; Babai, M.Z. Stock keeping unit fill rate specification. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 259, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzda, J.; Abbasi, B.; Urbańczyk, T. Data-driven inventory forecasting in periodic-review inventory systems adjusted with a fill-rate requirement. Decis. Sci. 2025, 56, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goltsos, T.E.; Syntetos, A.A.; Glock, C.H.; Ioannou, G. Inventory—Forecasting: Mind the gap. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 299, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzda, J. Quantile smoothing in supply chain and logistics forecasting. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 208, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, M.P. Evaluating Econometric Forecasts of Economic and Financial Variables; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, C.W.J.; Machina, M.J. Forecasting and decision theory. In Handbook of Economic Forecasting; Elliott, G., Granger, C.W.J., Timmermann, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneiting, T. Making and evaluating point forecasts. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2011, 106, 746–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, A.J. Comparing possibly misspecified forecasts. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2020, 38, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, F.; Ziegel, J.F. Generic conditions for forecast dominance. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2021, 39, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzda, J.; Wojtasik, J.; Abbasi, B. Forecast evaluation in base stock inventory systems with fill rate commitments using Murphy diagrams. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, G.; Timmermann, A. Economic Forecasting; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bruzda, J. Demand forecasting under fill rate constraints—The case of re-order points. Int. J. Forecast. 2020, 36, 1342–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.; Müller, S.; Fleischmann, M.; Stuckenschmidt, H. A data-driven newsvendor problem: From data to decision. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 278, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Wang, H.-T.; Ma, X.; Talluri, S. A data-driven newsvendor problem: A high-dimensional and mixed-frequency method. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 266, 109042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Babai, M.Z.; Davies, J.; Stephenson, D. Forecasting and stock control: A study in a wholesaling context. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 127, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, E.A.; Pyke, D.F.; Thomas, D.J. Inventory and Production Management in Supply Chain, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, A.J.; Ziegel, J.F.; Chen, R. Dynamic semiparametric models for expected shortfall (and Value-at-Risk). J. Econom. 2019, 211, 388–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syntetos, A.A.; Nikolopoulos, K.; Boylan, J.E. Judging the judges through accuracy-implication metrics: The case of inventory forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 2010, 26, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creal, D.; Koopman, S.J.; Lucas, A. Generalized autoregressive score models with applications. J. Appl. Econom. 2013, 28, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.C. Dynamic Models for Volatility and Heavy Tails, Econometric Society Monograph; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; Volume 52. [Google Scholar]

- Strijbosch, L.W.G.; Moors, J.J.A. The impact of unknown demand parameters on (R, S)-inventory control performance. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2005, 162, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzda, J. Multistep quantile forecasts for supply chain and logistics operations: Bootstrapping, the GARCH model and quantile regression based approaches. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 28, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ul Husna, A.; Amin, S.H.; Ghasempoor, A. Demand Forecasting Using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches in the Retail Industry: A Comparative Study. In Industrial Engineering in the COVID-19 Era. GJCIE 2022; Lecture Notes in Management and Industrial Engineering; Calisir, F., Durucu, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridakis, S.; Hibon, M. The M3-Competition: Results, conclusions and implications. Int. J. Forecast. 2000, 16, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Petropoulos, F.; Kang, Y. Improving Forecasting by Subsampling Seasonal Time Series. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 61, 976–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godahewa, R.; Bergmeir, C.; Baz, Z.E.; Zhu, C.; Song, Z.; García, S.; Benavides, D. On Forecast Stability. Int. J. Forecast. 2025, 41, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, C.D.; Schneider, M.J.; Lee, J. Can We Protect Time Series Data While Maintaining Accurate Forecasts? Int. J. Forecast. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, A.; Benidis, K.; Bohlke-Schneider, M.; Flunkert, V.; Gasthaus, J.; Januschowski, T.; Maddix, D.C.; Rangapuram, S.; Salinas, D.; Schulz, J.; et al. GluonTS: Probabilistic and Neural Time Series Modeling in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–6. Available online: http://jmlr.org/papers/v21/19-820.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.J. Measuring Item Fill-Rate Performance in a Finite Horizon. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2005, 7, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, P.; Mula, J.; Sanchis, R. Sustainable Inventory Management in Supply Chains: Trends and Further Research. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, S.; Nayak, M.M.; Abbate, S.; Centobelli, P. Recent Trends in Sustainable Inventory Models: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).