The Impact of Digital Technology Penetration on Sustainable Household Consumption: Evidence from China’s Sinking Market

Abstract

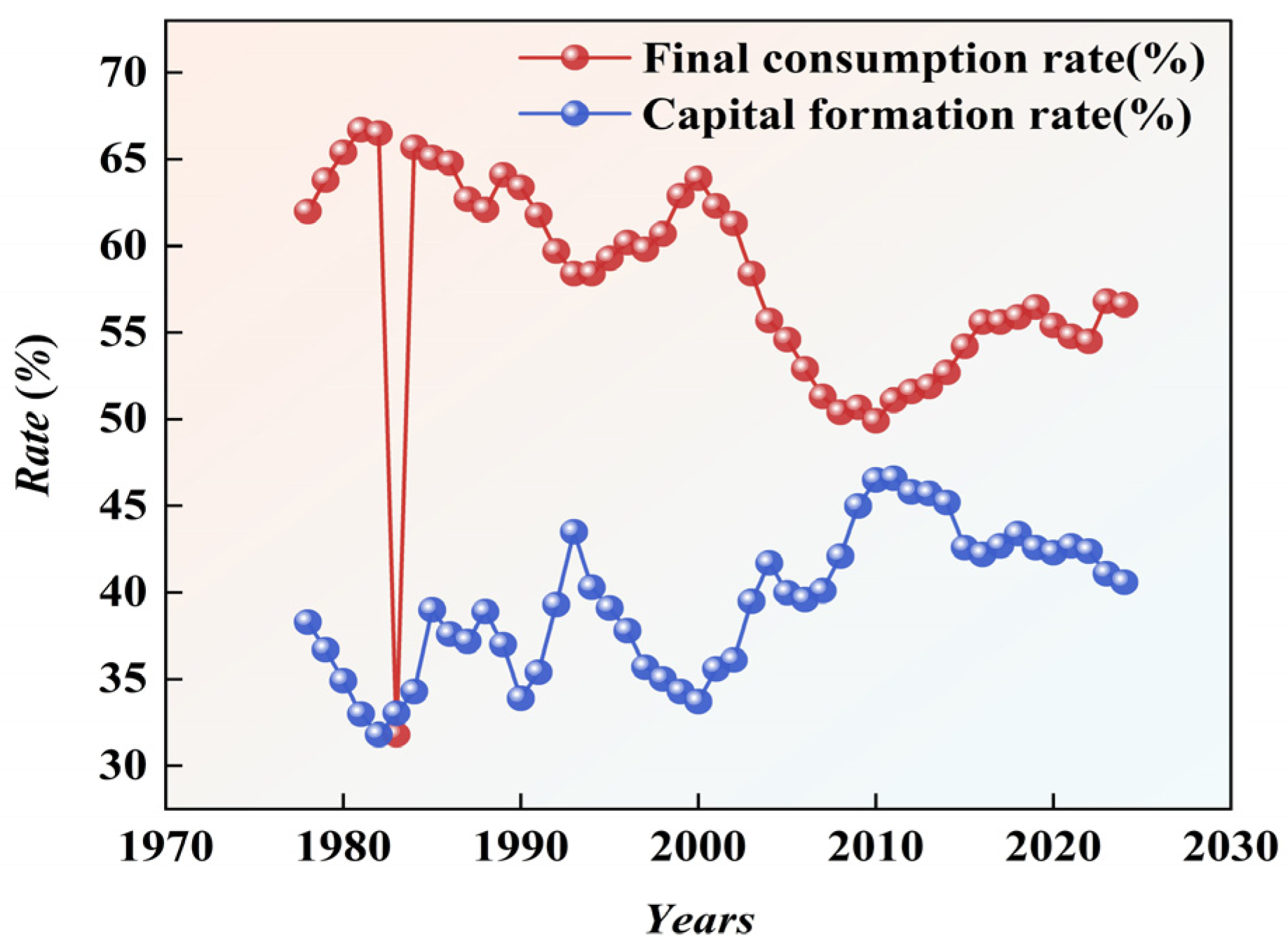

1. Introduction

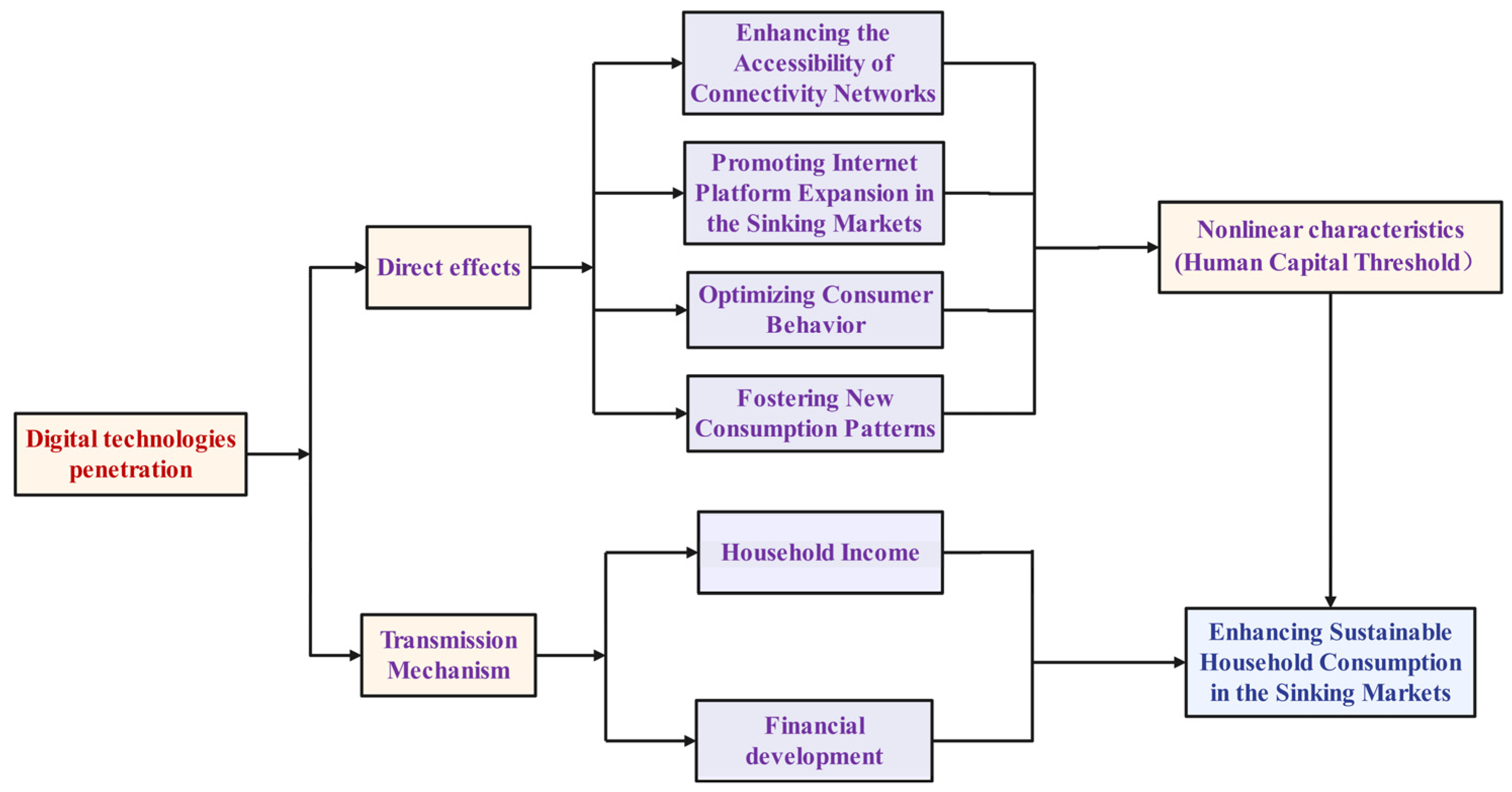

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Impact of Digital Technology Penetration on Consumer Behavior in the Sinking Market

2.2. The Transmission Mechanism of Digital Technology Penetration on Sustainable Consumption in the Sinking Market

2.2.1. The Income Effects of Digital Technology Penetration

2.2.2. The Financial Inclusion Effects of Digital Technology Penetration

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources, Sample Construction, and Preprocessing

3.1.1. Sample Selection and Processing

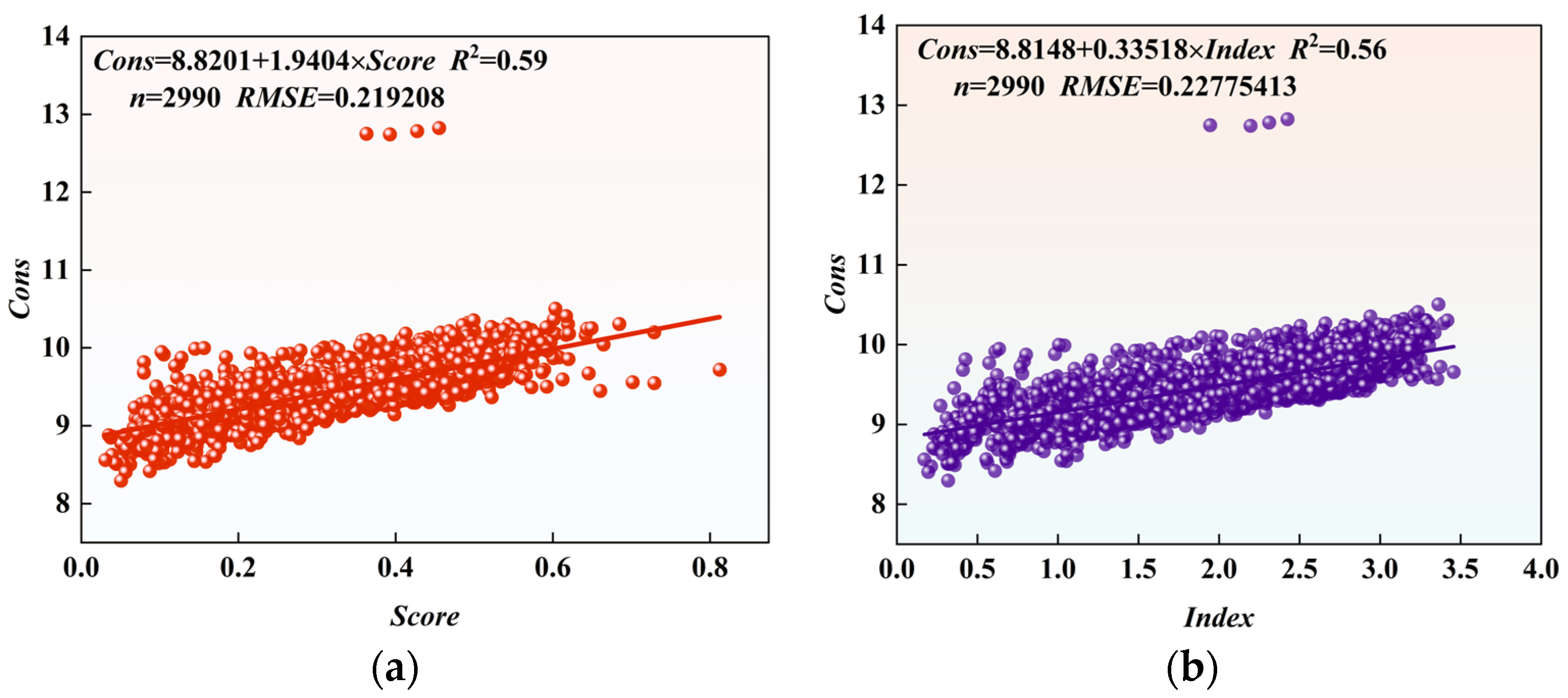

3.1.2. Variable Definitions

- (1)

- Dependent variable: sustainable household consumption (Cons). This study draws on Zhang et al. [44], who examined the macro-level impact of inclusive finance on household welfare. Total expenditure was adopted as an effective indicator to assess consumption levels and economic resilience, providing a foundation for understanding sustainable consumption patterns. The per capita consumption expenditure of households in the sinking market was used as a proxy indicator for sustainable household consumption. Specifically, Up, Uc, Rp, Rc, and Tp are used to denote urban population, urban per capita consumption, rural population, rural per capita consumption, and total population, respectively, with the results transformed into logarithmic form.

- (2)

- Key independent variable: digital technology penetration (score). Digital technologies exhibit two core attributes—data factorization and digital enablement [45]. Although invention patent applications are widely employed as supply-side proxies of digital development [46], and some studies synthesize digital industry and application dimensions [47], the analysis centers on application-side penetration. Referring to the measurement of the impact of digital finance on consumption by Zhang et al. [21] and Guo et al. [48] pointing out that the digital inclusive finance index is mainly compiled based on consumer data, a composite penetration index is constructed from three subdimensions of the Digital Inclusive Finance Index—account coverage, payment activity, and digital support services—augmented with internet penetration. Indicators are directionally aligned and standardized; Compared with the Analytic Hierarchy Process and Principal Component Analysis, the entropy method is more objective in assigning values, weights are assigned via the entropy method. The specific calculation process is as follows:

- Step 1: Standardize the variables:

- Step 2: Calculate the proportion of indicators. Calculate the relative proportion of each indicator in each sample:

- Step 3: calculate information entropy. Calculate the information entropy of each indicator based on its proportion:

- Step 4: Calculate the weights of each indicator:

- Step 5: Calculate the comprehensive score:

- (3)

- Instrumental Variable: Great Circle Distance to Hangzhou (dis_s). Referring to Fan et al. [50] selection of instrumental variables, this article selects the spherical distance from prefecture level cities to Hangzhou as the instrumental variable, which is calculated using a geographic information system (GIS). The robustness test uses the 2000 mobile phone penetration rate as an instrumental variable, where the mobile phone penetration rate () is calculated as the number of mobile phone users at the end of the year () divided by the total population ().

- (4)

- Mediators: Household Income () and Financial Development (). Both theoretical and empirical evidence confirm that household income is the most crucial determinant of consumption. Digital technology penetration promotes consumption by raising household income. Urban and rural per capita income, denoted as and , are employed respectively, with household income calculated as:

- (5)

- Threshold variable: human capital (Hca). The extent of digital technology penetration in the sinking market is correlated with the knowledge base of its households. Ep represents the number of students enrolled in regular higher education institutions. The calculation formula is as follows:

- (6)

- Other variables. Drawing on existing studies of the digital economy, digitalization, and household consumption, economic development level (lngdp), urbanization (Urb), government intervention (Gov), and openness (open) are included as additional explanatory variables. Lf and Te-x denote local government general budget expenditure and total imports and exports, respectively. The calculation formula is as follows:

3.1.3. Data Processing

3.2. Econometric Model Selection

3.2.1. The Relationship Between Digital Technology Penetration and Sustainable Household Consumption in the Sinking Market

3.2.2. Econometric Model Specification: The Effect of Digital Technology Penetration on Sustainable Household Consumption in the Sinking Market

- (1)

- Baseline model specification

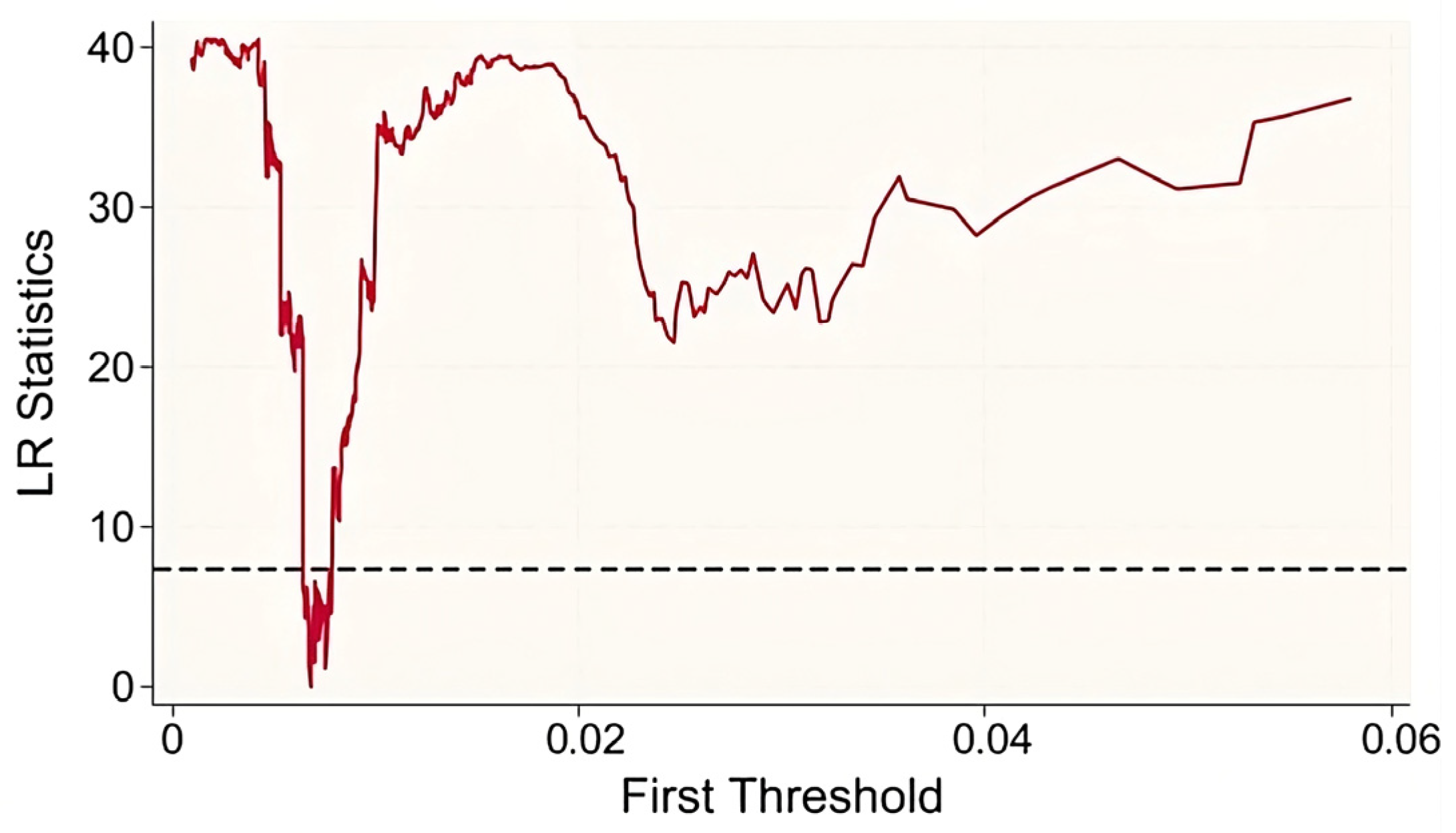

3.2.3. Threshold Model Specification

3.2.4. Specification of the Sobel Mediation Effect Model

4. Empirical Analysis of Digital Technology Penetration and Its Effects on Sustainable Household Consumption in the Sinking Market

4.1. Effects of Digital-Technology Penetration on Sustainable Household Consumption in the Sinking Market

4.2. Empirical Test for Endogeneity

4.3. Robustness Checks

4.3.1. Replace the Key Independent Variable

4.3.2. Modification of the Measurement Approach for the Key Independent Variable

4.3.3. Introduction of Higher-Order Nonlinear Terms

4.3.4. Replace Instrumental Variables

4.3.5. Excluding the Influence of Major Public Health Events

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Analysis of the Transmission Mechanism of Digital Technology Penetration on Sustainable Household Consumption in the Sinking Market

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Digital technology penetration can effectively enhance the sustainable consumption of households in the sinking market. This conclusion remains robust under various conditions, including the substitution of the key independent variable, modification of the method for calculating the key explanatory variable, the inclusion of higher-order terms for the key explanatory variable, replace instrumental variables and the exclusion of the impact of major public health events.

- (2)

- There exists a human capital threshold for the promotion of digital technology penetration on the income of households in the sinking market. An interesting phenomenon is observed in the baseline regression: human capital has an inhibitory effect on the consumption of sinking market households at the 10% significance level, which contradicts expectations. This suggests that the synergy between human capital and consumption in the sinking market results from human capital accumulation reaching a certain threshold. Only when human capital accumulation surpasses this threshold can positive changes in both variables be realized, highlighting the importance of human capital accumulation in the sinking market.

- (3)

- Household income and financial development play a partial mediating role in the impact of digital technology penetration on the sustainable consumption of sinking market households. Specifically, the mediating effect of “digital technology penetration → household income → sustainable household consumption” accounts for a substantial proportion, aligning with the theory that income is both a core influencing and constraining factor for sustainable consumption. The mediating effect of “digital technology penetration → financial development → sustainable household consumption” constitutes a smaller proportion; however, some mediating effects are statistically significant, suggesting that this path has further development potential and warrants further attention.

- (4)

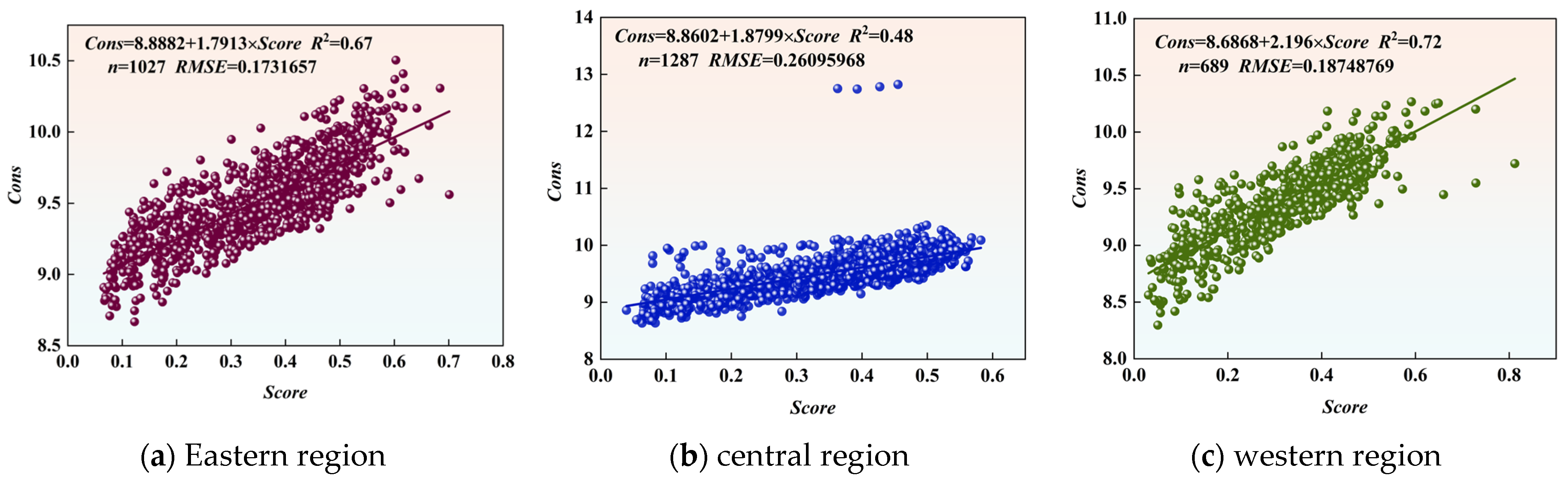

- Digital technology penetration is inclusive. Regional heterogeneity analysis reveals that under fixed effects, the impact of digital technology penetration on sustainable consumption in the sinking market follows this order: central region > western region > eastern region. Under the threshold effect, the promotion effect of digital technology penetration is as follows: western region > central region > eastern region. In both fixed effect and threshold effect models, the impact of digital technology penetration on sustainable consumption growth is more pronounced in the central and western regions, indicating that the positive effect of digital technology penetration on sinking market sustainable consumption exhibits an inclusive nature.

6.2. Recommendations

- (1)

- Comprehensively deepen the penetration and application of digital technology in the sinking market. Firstly, the direct and steady enhancement of sustainable consumption resulting from digital technology penetration is more significant in the central and western regions. Priority must be given to the acceleration of the development of new infrastructures, including 5G base stations, gigabit optical networks, the Internet of Things, and data centres, with a particular focus on central and western regions, counties, and rural areas. It is imperative to direct efforts towards resolving the “last mile” issue of network coverage, thereby ensuring both the accessibility and availability of high-quality network services. Secondly, it is imperative to proactively foster and nurture digital consumption scenarios within the sinking market. The primary objective of enhancing digital technology integration is to promote increased consumption. The exploration of a wide range of application scenarios is imperative to leverage the full potential of this integration. It is recommended that e-commerce platforms and local service providers develop applications that are better suited to the consumption habits of the sinking market (e.g., simplified apps, voice/video shopping). Support new models such as “live-streaming sales” and “community group purchasing” to promote both the upward flow of agricultural products and the downward flow of industrial goods. Organize regional digital consumption festivals and issue targeted digital consumption vouchers.

- (2)

- Continuously improving the accumulation of human capital. For regions with human capital levels below 0.0068, policies should focus on “literacy” and “achieving standards”. Specifically, we should make every effort to ensure and improve the quality of basic education, and ensure that the vast majority of the young labor force can achieve a high school education or above, which is a key step in promoting sustainable consumption through digital technology. For regions approaching or exceeding 0.0068, the policy focus should shift towards “optimization” and “enhancement”, vigorously developing vocational education and higher education, to fully leverage the driving role of high human capital in consumption upgrading and economic growth.

- (3)

- Improve the two mechanisms of “digital technology penetration → household income → sustainable household consumption” and “digital technology penetration → financial development → sustainable household consumption”. The key to improving the first mechanism is to cultivate “digital technology+” characteristic industries and new forms of employment, continuously expand income channels, combine digital technology with residents in the sinking market, and let workers see the benefits brought by digital technology, thereby forming positive incentives. The key to improving the second mechanism is to encourage financial institutions to develop small-scale, inclusive consumer credit and installment products that are more suitable for the credit characteristics and consumption scenarios of households in the sinking market, under the premise of controllable risks, to smooth household income and consumption cycles, and alleviate their liquidity constraints.

- (4)

- Implement differentiated and precise inclusive policies. As for the central region, building regional digital consumption hubs in core transportation hubs such as Zhengzhou, Wuhan, and Changsha, supporting central cities to hold digital consumption festivals and online exhibitions, enhancing the attractiveness and radiation of the central region in the field of digital consumption, and transforming location advantages into market advantages. As for the western region, in the national new infrastructure investment, it is clear to tilt a higher proportion towards the western region, and it is even more important to ensure the quality of network coverage and affordable network costs in remote rural and pastoral areas. In terms of talent introduction, the “Flexible Digital Talent Introduction and Localized Training” plan is implemented, encouraging eastern experts to serve the western region through forms such as “weekend engineers” and “online consultants”, while cultivating local digital forces rooted in the western region. Further expand the pilot scope of “inclusive finance”, relax the admission of pilot institutions, and provide risk compensation. In terms of the eastern region, the policy focus should shift towards innovative consumption patterns and quality improvement and explore corresponding governance models to provide a demonstration for the whole country; guide the cultivation of “high-end consumer market” and “digital brand matrix”; support the development of experience economy, customized economy, green consumption, etc., in eastern cities. It is particularly important to note that the formulation and implementation of policies are not static, but require regular evaluation of the effectiveness of policies in various regions, timely optimization and adjustment, prevention of policy rigidity, and implementation of rewards and punishments for excellence.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yi, S.H. Looking at the Trend of China’s Consumption Changes from the Law of Consumption Development in Developed Countries. Price Theory Pract. 2018, 10, 26–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.K. The Change of Social Structure and the Promotion of Consumer Power—Consumer Empowerment in the Era of Mobile Internet. Zhejiang Soc. Sci. 2021, 3, 87–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sandmo, A. Public Goods and the Technology of Consumption. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1973, 40, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkarainen, T.; Pikkarainen, K.; Karjaluoto, H.; Pahnila, S. Consumer Acceptance of Online Banking: An Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.T.; Huang, R. Research on the Interaction Mechanism between Technological Progress and Consumer Demand: Analysis of Factor Allocation Based on the Perspective of Supply-Side Reform. Economist 2017, 2, 50–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xing, X.Q.; Zhou, P.L.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, X.H. Digital Technology, BOP Business Model Innovation and Inclusive Market Building. Manag. World 2019, 35, 116–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.P. The Change of Consumption in the Digital Economy: Trends, Characteristics, Mechanisms and Model. Financ. Econ. 2020, 1, 120–132. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Contribution Share of the Three Components of GDP to the Growth of GDP (1970–2023) * [Data Set]. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01 (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Qu, X.; Chen, J. Changes in the structure of household expenditure in urban and rural China. Appl. Econ. 2024, 57, 1596–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.Y.; Zheng, R.X. Research Report on Further Tapping the Consumption Potential of Sinking Markets. Bank China Res. Inst. 2024, 43, 1–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 58Tong Zhen and County Governance Research Center; Social and Financial Research Center, School of Social Sciences, Tsinghua University. County Consumer Market Survey Report. Available online: https://rccg.sss.tsinghua.edu.cn/info/1014/1033.htm (accessed on 14 October 2025). (In Chinese).

- Wang, S.X.; Zhang, S.S.; Xu, H.; Gao, T.F. Developing Market, Product Quality and Traffic Data Game. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2024, 44, 129–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Couture, V.; Faber, B.; Gu, Y.; Liu, L. Connecting the Countryside via E-Commerce: Evidence from China. Am. Econ. Rev. Insights 2021, 3, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.R.; Yang, J.D. How to Optimize the Path of Industrial Goods Downlink by Rural E-Commerce from the Perspective of Rural Revitalization: Based on Grounded Theory Research of Value Chains Coupling Mechanism. Issues Agric. Econ. 2019, 4, 118–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Mu, X.; Xu, D.Y. Search and Information Frictions on Global E-Commerce Platforms: Evidence from AliExpress; NBER Working Paper 28100; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Digital Economics. J. Econ. Lit. 2019, 57, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Kuang, J. How Artificial Intelligence Applications Enhance Enterprise Green Total Factor Productivity? A Perspective on Human-Machine Matching and Labor Skill Structure. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 87, 926–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, M.P. The Digital Divide and the Elderly: How Urban and Rural Realities Shape Well-Being and Social Inclusion in the Sardinian Context. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.; Phillips, T. The Gender Digital Gap: Shifting the Theoretical Focus to Systems Analysis and Feedback Loops. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2023, 26, 2071–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.Q.; Yuan, D.M. Bridging the Digital Divide to Promote Digital Dividends for All. China Econ. Times 2019, 14, 5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Wan, G.H. Digital Finance and Household Consumption: Theory and Evidence from China. Manag. World 2020, 36, 48–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, S.Q.; Zhu, W.H. The Impact of Internet Use and Life Satisfaction on Household Consumption Expenditure: Based on Empirical Data from Chinese Surveys. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2025, 97, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöggl, J.; Stumpf, L.; Baumgartner, J.R. The role of interorganizational collaboration and digital technologies in the implementation of circular economy practices—Empirical evidence from manufacturing firms. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2023, 33, 2225–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Hsueh, S.C.; Zhang, S. Digital Payments and Household Consumption: A Mental Accounting Interpretation. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 2079–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.P. Digital Economy Drives High-Quality Economic Development: Efficiency Improvement and Consumption Promotion. J. Shanghai Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 24, 48–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L. Analysis of the Change of Artificial Intelligence to Online Consumption Patterns and Consumption Concepts. Soft Comput. 2022, 26, 7559–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, P.; Chen, W. Research on Chinese Live Broadcast Marketing and Sustainable Consumption Intention under the Internet Environment. ITM Web Conf. 2022, 45, 01073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, I.A.; Abubakar, R.I.; Sharifi, A. Low-carbon lifestyle index and its socioeconomic determinants among households in Saudi Arabia. Urban Clim. 2024, 56, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Permanent Income Hypothesis. In A Theory of the Consumption Function; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1957; pp. 20–37. Available online: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c4405 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Frish, R. Consumption and the Permanent Income of Households. Res. Econ. 2024, 78, 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alauddin, F.D.A.; Aman, A.; Ghazali, M.F.; Daud, S. The Influence of Digital Platforms on Gig Workers: A Systematic Literature Review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Li, L.Y. The Innovation of Business Model in Internet Era: From Value Creation Perspective. China Ind. Econ. 2015, 1, 95–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi, S.; Sumarto, S.; Suryahadi, A. It’s All in the Timing: Cash Transfers and Consumption Smoothing in a Developing Country. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 119, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriger-Lin, J.; Khanna, N.; Pape, A. Conspicuous Consumption and Peer-Group Inequality: The Role of Preferences. J. Econ. Inequal. 2020, 18, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, T.F.; Low, H.W. Job Loss, Credit Constraints and Consumption Growth. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2014, 96, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.A. Review of Money and Capital in Economic Development, by Ronald I. McKinnon. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1974, 56, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levchenko, A.A. Financial Liberalization and Consumption Volatility in Developing Countries. IMF Econ. Rev. 2005, 52, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Pu, M.; Wang, H. Digital Inclusive Finance, Rural Revitalization and Rural Consumption. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0310064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L. From Fintech to Finlife: The Case of Fintech Development in China. China Econ. J. 2016, 9, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousmah, M.A.Q.; Onori, D. Financial Openness, Aggregate Consumption, and Threshold Effects. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2016, 21, 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Ren, X.H.; Wen, F.H. The Spatial Spillover Effect of Digital Financial Inclusion on Resident Consumption. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2022, 42, 1770–1781. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zipser, D.; Hui, D.; Shi, J.; Chen, C. Chinese Consumption Under the New Normal; McKinsey: Shanghai, China, 2025; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com.cn (accessed on 7 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- China Logistics Information Center. Research Report on Sinking Market Development and E-Commerce Platform Value. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/355418260_99900352 (accessed on 7 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Zhang, J.; Gong, X.; Cheng, M. Broadband cities: Bridging the urban–rural consumption gap with digital innovation. Cities 2025, 167, 106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, H.C.L.; Chen, L. Digital Innovation Ecosystem: Concept, Structure and Innovation Mechanism. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2022, 9, 54–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.H.; Gao, Y.X. Technology Convergence of Digital and Real Economy Industries and Enterprise Total Factor Productivity: Research Based on Chinese Enterprise Patent Information. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 11, 118–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.C.; Xiong, Q.Y. Digital Technology Empowers China’s Service Sector Growth: Mechanism and Implementation Path. China Econ. 2022, 17, 26–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.Y. Measuring China’s Digital Financial Inclusion: Index Compilation and Spatial Characteristics. China Econ. Q. 2020, 19, 1401–1418. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook. 2024. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2024/indexch.htm (accessed on 10 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Fan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xu, L.; Wang, Z. Can Digital Economy Reshape Urban Spatial Structure? Evidence from the Perspective of Urban Sprawl. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2025, 74, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Yi, J.B. The Impact and Spatial Effects of Urban-Rural Equalization of Basic Public Services on Household Consumption: Empirical Evidence from 272 Prefecture-Level and Above Cities. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 45, 118–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sala-i-Martin, X. The World Distribution of Income: Falling Poverty and Convergence. Q. J. Econ. 2006, 121, 351–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxim, P.; Xavier, S.I.M. Lights, Camera … Income! Illuminating the National Accounts-Household Surveys Debate. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 579–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold Effects in Non-Dynamic Panels: Estimation, Testing, and Inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.L.; Ye, B.J. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.Q.; Liu, H.M.; Zhang, Y.S. Study on the Influence of Rural Land Transfer on Agricultural Carbon Emission Intensity and Its Mechanism in China. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 51–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Sawada, Y. The degree of precautionary saving: A reexamination. Econ. Lett. 2007, 96, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Yang, X.M. Dynamic Efficiency Compensation of Consumption and Human Capital and Its Innovation Effect. Financ. Trade Econ. 2025, 46, 114–130. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.L.; Guo, K.G.; Wang, C.J. Digital Economy, Distribution Efficiency and Consumer Growth. J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 6, 5–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nunn, N.; Qian, N.U.S. food aid and civil conflict. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1630–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.Y.; Liu, Z. Circulation Digitization and Residents’ Consumption Upgrading: Supply-Driven or Demand-Pull. J. Manag. 2025, 38, 114–132. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Ding, G.; Long, S.; Dong, Y.; Yan, J. Digital divide or dividend? Exploring the impact of the digital economy on regional gaps in high-quality economic development in China using a relational data model. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2025, 101, 104222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Yang, L.; Ta, M. The Impact of Digital Economy on Regional Resource Allocation Efficiency: An Analysis Based on Resource Flow Speed and Direction. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 82, 107644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Deng, F. The Impact of Digital Transformation on Enterprise Vitality—Evidence from Listed Companies in China. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2023, 36, 3955–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quttainah, M.A.; Ayadi, I. The Impact of Digital Integration on Corporate Sustainability: Emissions Reduction, Environmental Innovation, and Resource Efficiency in Europe. J. Innov. Knowl. 2024, 9, 100525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibuea, N. Digital Innovation as the Key to Efficiency and Accountability of Public Administration in Medan City, Indonesia. Golden Ratio Data Summ. 2025, 5, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Metric | Secondary Indicator | Indicator Description | Indicator Weight | Indicator Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| digital technology penetration | Number of Alipay accounts per 10,000 people | |||

| Account coverage rate | Proportion of Alipay card binding users | 0.2008 | + | |

| Average number of bank cards bound to each Alipay account | ||||

| Per capita number of payments | ||||

| Per capita payment amount | ||||

| payment business | High frequency (active 50 times or more per year) ratio of active users to active 1 time or more per year | |||

| 0.2126 | + | |||

| Proportion of mobile payment transactions | ||||

| Proportion of mobile payment amount | ||||

| Average loan interest rate for small and micro operators | ||||

| Personal average loan interest rate | ||||

| Digitization level | Proportion of Huabei payment transactions | 0.1618 | + | |

| Proportion of Sesame Credit Free | ||||

| Deposit Transactions (More than all cases requiring a deposit) | ||||

| Proportion of Sesame Credit Free Deposit Amount (More than all situations requiring a deposit) | ||||

| Proportion of user QR code payments made | ||||

| Proportion of user QR code payment amount | ||||

| Internet penetration | The ratio of Internet broadband access users to registered residence population | 0.4248 | + |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Sd | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | 3003 | 9.473 | 0.345 | 8.296 | 12.824 |

| score | 3003 | 0.335 | 0.137 | 0.031 | 0.812 |

| index | 3003 | 1.957 | 0.769 | 0.170 | 3.457 |

| lngdp | 3003 | 10.613 | 0.569 | 8.730 | 12.764 |

| Hca | 3003 | 0.0051 | 0.014 | 0.0001 | 0.0101 |

| Urb | 3003 | 0.538 | 0.128 | 0.182 | 0.988 |

| Gov | 3003 | 0.219 | 0.104 | 0.044 | 0.916 |

| open | 3003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.029 |

| Inc | 3003 | 9.860 | 0.341 | 8.446 | 10.953 |

| Fin | 3003 | 2.386735 | 1.064346 | 0.5878793 | 21.30146 |

| dis_s | 3003 | 1072.568 | 533.2651 | 101.3577 | 3185.424 |

| phl | 3003 | 0.070 | 0.072 | 0.009 | 0.742 |

| ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | ⑦ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| score | 1.767 *** | 1.389 *** | 1.418 *** | 1.149 *** | 1.015 *** | 1.039 *** | |

| (48.54) | (23.28) | (22.67) | (17.12) | (12.59) | (12.74) | ||

| lngdp | 0.224 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.192 *** | 0.251 *** | 0.242 *** | 0.229 *** | |

| (8.13) | (8.18) | (7.98) | (8.09) | (7.77) | (10.90) | ||

| Hca | −2.454 * | −2.606 * | −2.454 * | −2.440 * | |||

| (−2.23) | (−2.52) | (−2.39) | (−2.39) | ||||

| Urb | 0.953 *** | 0.949 *** | 0.954 *** | 0.971 *** | |||

| (7.25) | (7.15) | (7.21) | (12.57) | ||||

| Gov | 0.383 ** | 0.370 ** | 0.316 *** | ||||

| (3.32) | (3.23) | (3.82) | |||||

| open | 4.584 * | 4.520 * | |||||

| (2.22) | (2.25) | ||||||

| 1.158 *** (20.94) | |||||||

| 0.998 *** (20.16) | |||||||

| Region FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 8.880 *** | 6.626 *** | 6.578 *** | 6.576 *** | 5.908 *** | 5.981 *** | 6.088 *** |

| (727.68) | (23.97) | (23.34) | (26.91) | (17.75) | (17.94) | (27.98) | |

| N | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 |

| r2_a | 0.744 | 0.760 | 0.761 | 0.773 | 0.775 | 0.776 | 0.759 |

| Explained Variable | Threshold Variable | Threshold Number | F-Statistic | 10% | 5% | 1% | Threshold | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Hca | Single | 40.57 | 30.5845 | 37.7327 | 62.2610 | 0.0068 | [0.0066, 0.0068] |

| Variable | R2 | Adjusted | Partial R2 | Robust | Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | F(1,2996) | ||||

| score (IV dis_s) | 0.4690 | 0.4680 | 0.0959 | 273.473 | 0.0000 |

| Variable | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| score | 1.264 *** | 1.263 *** | 1.263 *** | 1.263 *** | 1.263 *** | |

| (48.53) | (15.35) | (15.35) | (15.35) | (15.35) | ||

| lngdp | 0.184 *** | 0.154 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.184 *** |

| (20.34) | (22.40) | (13.67) | (13.67) | (13.67) | (13.67) | |

| Hca | −1.010 *** | 0.505 *** | −1.010 *** | −1.010 *** | −1.010 *** | −1.010 *** |

| (−3.39) | (2.74) | (−3.36) | (−3.36) | (−3.36) | (−3.36) | |

| Urb | 0.599 *** | 0.186 *** | 0.599 *** | 0.599 *** | 0.599 *** | 0.599 *** |

| (18.18) | (7.57) | (16.84) | (16.84) | (16.84) | (16.84) | |

| Gov | −0.018 | 0.567 *** | −0.017 | −0.017 | −0.017 | −0.017 |

| (−0.61) | (19.41) | (−0.37) | (−0.37) | (−0.37) | (−0.37) | |

| open | 3.486 *** | −9.590 *** | 3.480 ** | 3.480 ** | 3.480 ** | 3.480 ** |

| (3.42) | (−9.47) | (3.24) | (3.24) | (3.24) | (3.24) | |

| dis_s | −0.0001 *** (−16.54) | |||||

| F-statistic | 453.46 | |||||

| Wald χ2 statistic | Prob > F = 0 | 9117.55 Prob > chi2 = 0 | 9117.55 Prob > chi2 = 0 | 9117.55 Prob > chi2 = 0 | 9117.55 Prob > chi2 = 0 | |

| Regional FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| _cons | 6.788 *** | −1.432 *** | 6.786 *** | 6.786 *** | 6.786 *** | 6.786 *** |

| (79.11) | (−21.29) | (52.52) | (52.52) | (52.52) | (52.52) | |

| N | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 |

| r2_a | 0.748 | 0.4680 | 0.748 | 0.748 | 0.748 | 0.748 |

| Variable | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| index | 0.206 *** | ||||

| (15.53) | |||||

| lngdp | 0.194 *** | 0.250 *** | 0.232 *** | 0.200 *** | 0.221 *** |

| (6.34) | (7.87) | (7.87) | (11.48) | (4.81) | |

| Hca | −2.386 * | −2.538 * | −1.402 | −0.999 *** | −1.543 |

| (−2.33) | (−2.49) | (−1.43) | (−3.35) | (−0.61) | |

| Urb | 0.834 *** | 0.966 *** | 0.919 *** | 0.615 *** | 0.857 *** |

| (6.07) | (7.30) | (6.86) | (15.70) | (4.15) | |

| Gov | 0.258 * | 0.409 *** | 0.259 * | 0.028 | 0.449 *** |

| (2.32) | (3.49) | (2.46) | (0.46) | (3.52) | |

| open | 5.720 ** | 4.298 * | 3.880 * | 3.040 ** | 2.984 |

| (2.87) | (2.09) | (1.99) | (2.58) | (1.35) | |

| score | 1.558 *** | 1.159 *** | 1.130 *** | ||

| (10.96) | (9.51) | (11.23) | |||

| score2 | −0.799 *** | ||||

| (−4.34) | |||||

| score1 | 0.088 *** | ||||

| (12.39) | |||||

| Regional FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 6.531 *** | 6.240 *** | 6.055 *** | 6.635 *** | 6.213 *** |

| (19.64) | (17.27) | (19.27) | (39.78) | (13.07) | |

| N | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 2079 |

| r2_a | 0.782 | 0.775 | 0.778 | 0.747 | 0.716 |

| Explained Variable | Threshold Variable | Threshold Number | F-Statistic | 10% | 5% | 1% | Threshold | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons (East) | Hca | No | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Cons (Central) | Hca | Single | 34.43 | 33.5079 | 45.8860 | 69.8928 | 0.0066 | [0.0065, 0.0066] |

| Cons (West) | Hca | Single | 38.24 | 30.8671 | 35.4819 | 44.7877 | 0.0237 | [0.0228, 0.0238] |

| ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | ⑥ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| score | 1.016 *** | 1.137 *** | 0.819 *** | |||

| (8.58) | (9.01) | (4.25) | ||||

| lngdp | 0.112 *** | 0.279 *** | 0.405 *** | 0.108 *** | 0.257 *** | 0.381 *** |

| (3.55) | (5.00) | (4.83) | (5.70) | (5.88) | (11.86) | |

| Hca | −0.320 | −3.564 | −4.803 ** | |||

| (−0.41) | (−1.47) | (−2.43) | ||||

| Urb | 1.102 *** | 0.533 ** | 1.005 *** | 1.108 *** | 0.517 ** | 1.014 *** |

| (5.49) | (2.76) | (4.09) | (15.31) | (3.22) | (9.32) | |

| Gov | 0.519 ** | 0.569 ** | 0.376 * | 0.496 *** | 0.445 ** | 0.338 *** |

| (2.89) | (3.27) | (1.91) | (5.25) | (2.62) | (3.38) | |

| open | 3.908 | 5.235 | −8.448283 | 3.976 * | 4.411 | −9.594 |

| (1.71) | (1.75) | (−0.88) | (2.42) | (1.17) | (−1.45) | |

| score × I (Hca < 0.0066) | / | 1.409 *** (12.51) | ||||

| score × I (Hca > 0.0066) | 1.107 *** (11.08) | |||||

| score × I (Hca < 0.0237) | 0.833 *** (11.29) | |||||

| score × I (Hca > 0.0237) | 0.595 *** (7.98) | |||||

| Regional FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 7.244 *** | 5.761 *** | 4.381 *** | 7.282 *** | 5.968 *** | 4.581 *** |

| (18.93) | (9.67) | (5.37) | (35.46) | (13.32) | (14.32) | |

| N | 1027 | 1287 | 689 | 1027 | 1287 | 689 |

| r2_a | 0.913 | 0.659 | 0.9050 | 0.908 | 0.639 | 0.898 |

| Inc | Fin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ | |

| score | 1.264 *** (41.86) | 1.384 *** (68.18) | 0.319 *** (7.45) | 2.548 *** (18.80) | 1.235 *** (38.72) |

| lngdp | 0.184 *** (16.74) | 0.169 *** (22.96) | 0.068 *** (6.43) | −0.734 *** (−14.91) | 0.192 *** (16.91) |

| Hca | −1.010 *** (−3.99) | −0.519 ** (−3.05) | −0.656 ** (−2.91) | 27.404 *** (24.11) | −1.325 *** (−4.79) |

| Urb | 0.599 *** (15.56) | 0.632 *** (24.45) | 0.167 *** (4.46) | 3.042 *** (17.63) | 0.564 *** (0.040) |

| Gov | −0.018 (−0.45) | −0.257 *** (−9.63) | 0.158 *** (4.40) | 3.303 *** (18.52) | −0.056 −1.33 |

| open | 3.486 ** (2.59) | 6.385 *** (7.06) | −0.874 (−0.72) | −32.075 *** (−5.31) | 3.854 ** (2.85) |

| Inc | 0.683 *** (28.27) | ||||

| Fin | 0.011 ** | ||||

| (2.82) | |||||

| Regional FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 6.789 *** (63.85) | 7.308 *** (102.29) | 1.798 *** (8.98) | 6.662 *** (13.97) | 6.711 *** (61.24) |

| N | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 | 3003 |

| r2_a | 0.748 | 0.884 | 0.801 | 0.467 | 0.748 |

| Inc | Fin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Est | Std_err | z | p > |z| | Est | Std_err | z | p > |z| |

| Path a | 1.384 | 0.020 | 68.181 | 0.000 *** | 2.548 | 0.135 | 18.804 | 0.000 *** |

| Path b | 0.683 | 0.024 | 28.267 | 0.000 *** | 0.011 | 0.004 | 2.820 | 0.005 *** |

| Indirect effect (a×) | 0.945 | 0.036 | 26.112 | 0.000 *** | 0.029 | 0.010 | 2.789 | 0.005 *** |

| Direct effect c′ | 0.319 | 0.043 | 7.450 | 0.000 *** | 1.235 | 0.032 | 38.723 | 0.000 *** |

| Total effect c | 1.264 | 0.030 | 41.864 | 0.000 *** | 1.264 | 0.030 | 41.864 | 0.000 *** |

| Proportion Mediated (a × b/c) | 74.7% | 2.3% | ||||||

| Sobel’s Z statistic | 26.11 *** | 2.789 *** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. The Impact of Digital Technology Penetration on Sustainable Household Consumption: Evidence from China’s Sinking Market. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210175

Zhao X, Li Y, Zhang W. The Impact of Digital Technology Penetration on Sustainable Household Consumption: Evidence from China’s Sinking Market. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210175

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Xinghua, Ya’e Li, and Wang Zhang. 2025. "The Impact of Digital Technology Penetration on Sustainable Household Consumption: Evidence from China’s Sinking Market" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210175

APA StyleZhao, X., Li, Y., & Zhang, W. (2025). The Impact of Digital Technology Penetration on Sustainable Household Consumption: Evidence from China’s Sinking Market. Sustainability, 17(22), 10175. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210175