1. Introduction

Waste management has emerged as a critical global issue in response to escalating population growth, urbanization, and unsustainable consumption patterns. The projected increase in the world population to 9.7 billion by 2050 and 10.4 billion by 2100 places immense pressure on existing waste management systems and resource cycles [

1]. This growth is expected to result in a parallel surge in material consumption and waste generation, exacerbating challenges related to environmental degradation, public health, and ecological balance if not addressed through robust and systemic solutions [

2,

3]. Improper waste disposal contributes to air and water pollution, soil contamination, and greenhouse gas emissions, thereby worsening climate change impacts and compromising ecosystem resilience. In response to these threats, global attention has turned toward circular economy (CE) frameworks that prioritize resource efficiency and waste minimization through reuse, repair, recycling, and closed-loop systems [

4,

5,

6]. These strategies offer a transformative alternative to traditional linear models of production and consumption, where resources are extracted, used, and discarded.

However, the implementation of waste management and CE strategies is far from uniform across countries. In many low-income nations, waste systems are underdeveloped and rely heavily on informal sectors and community-level governance. In contrast, middle- and high-income countries generally operate under formalized waste governance structures supported by regulatory, financial, and technological frameworks [

3,

7]. Nevertheless, even in more advanced systems, challenges persist regarding regulatory enforcement, waste diversion targets, infrastructure development, and public participation [

3,

8].

Many nations are now working to align their waste strategies with CE principles and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), recognizing that waste management is a key enabler of broader sustainability agendas. Initiatives such as urban composting plants, material recovery facilities, and product stewardship programs exemplify how integrated waste systems can simultaneously advance goals such as climate action, clean water, responsible consumption, and sustainable cities [

9,

10,

11].

Central to the realization of CE objectives is the role of local governments. Municipalities and councils often serve as the frontline implementers of national environmental policies. They coordinate waste collection services, manage recycling contracts, educate communities, and oversee local infrastructure development. Through these roles, local governments are uniquely positioned to translate abstract national CE targets into tangible community-level practices [

12].

In line with these global developments, Australia—a nation with a current population of 26.26 million that is expected to grow to 30 million between 2029 and 2033—has increasingly acknowledged the importance of transitioning to sustainable and circular waste management practices [

13]. In 2018, Australia launched its National Waste Policy, outlining five foundational principles to guide the nation’s waste strategy. This was followed in 2019 by the National Waste Policy Action Plan, which set seven national targets aimed at reducing waste generation, boosting resource recovery, and promoting circular economy innovation, with a strong emphasis on local government collaboration [

14,

15].

Among the most ambitious of these goals was the phased ban on the export of recyclable waste by 2022, intended to catalyse domestic recycling infrastructure and reduce reliance on offshore processing markets. By 2025, Australia had successfully implemented bans on the export of waste glass, mixed plastics, and paper/cardboard. However, significant disparities remain, particularly in rural and regional areas where local processing capacity is insufficient, leading to stockpiling or diversion to landfill.

To support this systemic transition, the Australian Government unveiled its Circular Economy Framework in 2023, providing a national vision for transitioning from a linear to a circular economy. The framework emphasizes design-for-reuse, sustainable procurement, and improved recovery systems at end-of-life stages. Importantly, it recognizes the need for multi-level governance, inclusive infrastructure investment, and community engagement to operationalize CE principles nationwide [

16].

Historically, Australia depended heavily on exporting recyclable waste materials, particularly to China and Southeast Asia. The 2019 implementation of China’s National Sword policy and subsequent import restrictions created a seismic disruption in global recycling markets [

17]. Australia, like many nations, was left with surplus waste and limited domestic processing capabilities, triggering a re-evaluation of national waste strategy priorities [

18].

In response, Australia doubled down on its circular economy commitment. The National Waste Policy Action Plan articulated concrete targets to be met by 2030, including reducing per capita waste generation by 10%, achieving an 80% resource recovery rate, and phasing out problematic plastics by 2025. It also emphasized the need to halve organic waste sent to landfills and promote transparent data collection and reporting for evidence-based decision-making [

14,

15].

Financial commitments have followed suit. The Australian government has invested over AU$1 billion in the waste and recycling sector. Programs such as the National Product Stewardship Investment Fund and the Recycling Modernization Fund provide substantial support for infrastructure upgrades, innovation projects, and community-level CE initiatives. These efforts demonstrate a significant shift toward system-level transformation of waste governance and material flows.

At the sub-national level, Australian states and territories have implemented their own circular economy plans that complement federal goals. For example, Victoria’s Recycling Victoria strategy focuses on reducing landfill dependency, enhancing recycling, and building a circular economy through regulatory reform and investment [

19]. Similarly, New South Wales has launched CE strategies that emphasize innovation, community engagement, and market development [

20]. Queensland aims for “zero waste to landfill” through an integrated CE framework, while Western Australia’s Waste Strategy 2030 sets bold targets for recovery and waste minimization [

21,

22].

South Australia and Tasmania are also actively pursuing circular economy pathways, with a focus on maximizing regional strengths, industrial ecology, and business model innovation [

23,

24]. These state-level efforts not only reflect policy convergence with national priorities but also underscore the essential role of local governance in realizing CE objectives.

In this context, the contributions of Australian local governments are increasingly vital. Councils are responsible for implementing waste collection programs, maintaining infrastructure, managing procurement practices, and educating residents—activities that form the foundation of circular economy transformation at the community level. Despite their central role, there remains limited national data or cross-comparative studies that evaluate how effectively councils are aligning with CE goals, especially five years after the launch of the National Waste Policy.

This study addresses that gap by offering a comprehensive, council-level analysis of Australia’s progress in localizing circular economy practices. It examines variations in waste service provision, infrastructure development, digital tool integration, and policy implementation across councils, and expands the analytical lens to include energy recovery and waste-to-energy initiatives.

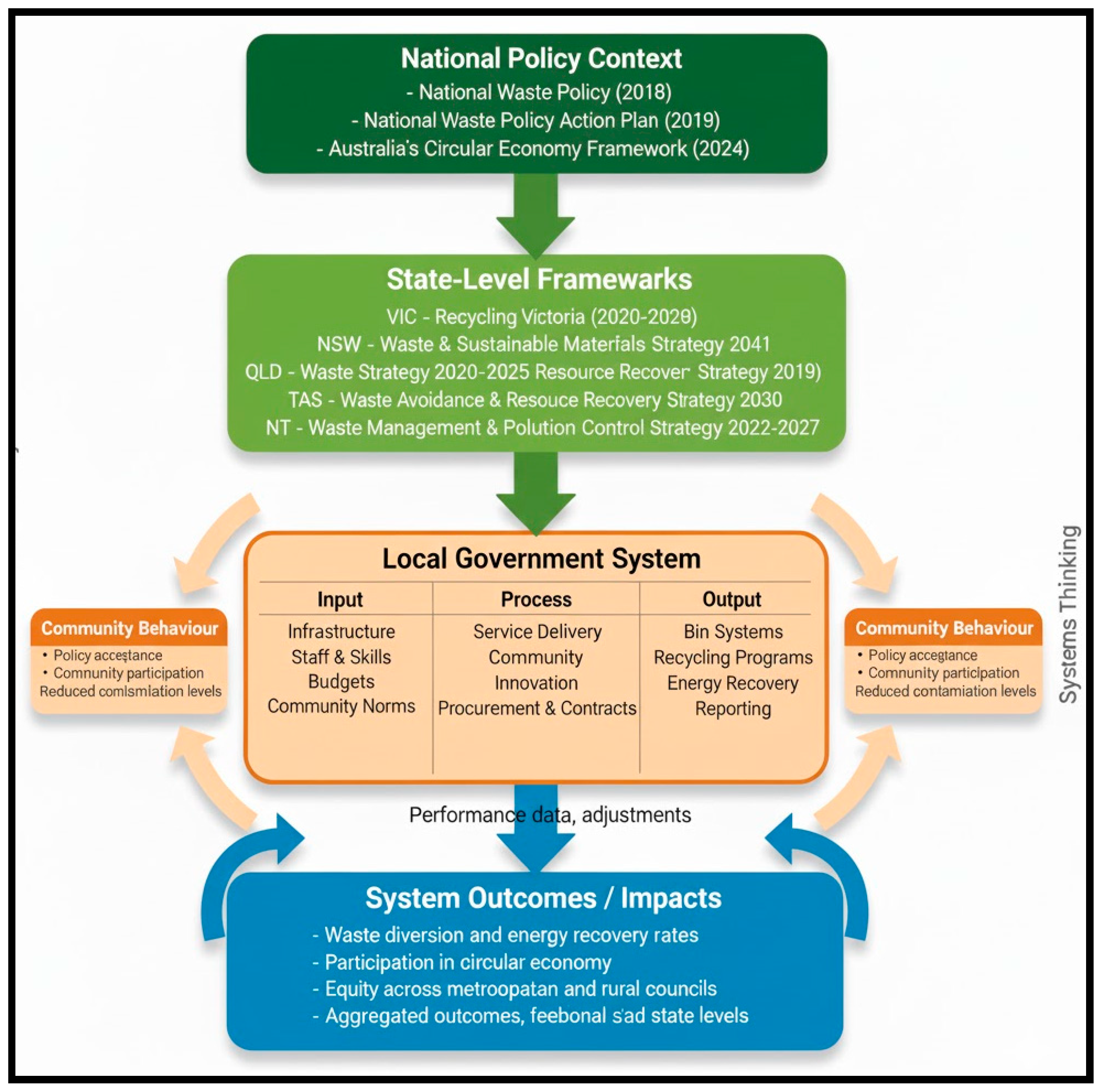

Guided by environmental governance theory and systems thinking, this study explores how policy design, institutional capacity, and resource–energy interactions collectively shape local circular economy outcomes. Environmental governance theory provides a framework for understanding the multi-level coordination challenges between national, state, and local governments, while systems thinking illuminates how decisions regarding waste collection, education, and technology interact within broader socio-environmental systems.

Existing international studies on municipal circular economy performance tend to emphasize service provision (e.g., kerbside separation, recycling access) and behavior change, but often treat energy recovery, institutional capacity, and funding structures as secondary or external to “waste” [

3,

7,

8]. In contrast, this study treats local household waste services, organics recovery, and emerging waste-to-energy activity as coupled governance and technical systems. In doing so, it responds to calls for analysis that links resource flows to energy outcomes and to the fiscal/administrative realities of local government delivery in federated systems such as Australia.

To systematically evaluate these issues, this study poses the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: How consistently are core household waste services (general waste, FOGO, mixed recycling, glass separation) provided across Australian councils?

RQ2: To what extent are councils implementing circular economy and energy recovery initiatives, and how does this differ across states and between metropolitan and rural councils?

RQ3: What governance and capacity constraints limit councils’ ability to deliver circular economy outcomes aligned with the National Waste Policy Action Plan targets?

These questions allow the research to critically evaluate local circular economy performance not only in terms of materials management but also in terms of resource—energy coupling, policy coherence, and systemic feedback loops. The following section presents the research design, theoretical framework, and analytical approach used to examine these dimensions.

This paper therefore contributes (i) an Australia-wide council-level map of circular economy and energy recovery practices; (ii) evidence of systematic metropolitan–rural inequality in service delivery, policy maturity, and technical capacity; and (iii) a theory-informed explanation of why these inequalities persist, using environmental governance theory (responsibility without resourcing) and systems thinking (feedback loops between infrastructure, community behavior, and market demand).

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study used a descriptive quantitative design to assess household waste management and circular economy initiatives across Australian local governments. It encompassed a census-level review of 520 councils across six Australian states—Tasmania, South Australia, Victoria, Queensland, New South Wales, and Western Australia—out of the 537 councils nationwide. Territories were excluded due to the unavailability of accessible and verifiable data. This study employed descriptive statistical analysis because the primary aim was to map service provision and policy variation across all 520 councils at a national census scale, rather than to test causal differences between groups.

To mitigate concerns about data reliability and ensure transparency, this study followed a systematic content analysis methodology. A structured data extraction protocol was developed to standardize how information was collected from each council website, and classification procedures were designed based on established principles of the circular economy, as articulated by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [

25].

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Council websites were systematically reviewed between June and September 2024. Each site was independently reviewed by two coders, and relevant information was recorded in a structured Excel database. A dual-coding approach was used to classify projects under either “waste management” or “circular economy,” with inter-rater agreement checks conducted to minimise bias and enhance internal validity.

Projects were classified according to the three principles of the circular economy outlined by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [

25]:

Eliminate waste and pollution—e.g., contamination prevention, waste education.

Circulate products and materials—e.g., reuse schemes, repair programs, recycling incentives.

Regenerate natural systems—e.g., composting initiatives, worm farming, community gardens.

Initiatives that focused primarily on waste collection, disposal, or landfill infrastructure were categorised under “waste management.” Projects that addressed product life extension, regeneration, or material reuse were categorised under “circular economy.” Some projects were dual coded where appropriate.

In cases where classification was ambiguous, a consensus approach was adopted between coders. A coding manual was also maintained to ensure consistency and is available upon request. To improve robustness, data triangulation was applied by cross-referencing council websites with publicly available reports, state-level policy documentation (e.g., Recycling Victoria, Sustainability NSW), and relevant press releases. Any discrepancies were documented, and unreliable data were excluded from the final dataset. Thematically, projects were categorised by type (e.g., infrastructure, rebates, educational initiatives) and analysed both by frequency and geographic distribution across states and rural vs. metropolitan councils.

2.3. Theoretical Framework

This study applies an integrated theoretical framework combining environmental governance theory and systems thinking to explain how institutional, technical, and behavioural factors influence circular-economy outcomes at the local-government level.

Environmental governance theory provides a macro-institutional lens for understanding how decentralised responsibility and multi-level policy interactions shape sustainability implementation. Local councils in Australia operate within a governance architecture where national strategies set broad targets, while fiscal and operational responsibility lies with sub-national governments. Previous studies have shown that such multi-level governance arrangements often produce “implementation gaps,” where local actors are tasked with achieving environmental targets without equivalent financial or technical resources [

25,

26,

27]. Environmental governance theory is therefore applied to identify the policy instruments, accountability mechanisms, and institutional relationships most critical to enabling effective local circular-economy delivery [

28].

Systems thinking complements this perspective by framing municipal waste management and circular-economy practices as dynamic socio-technical systems characterised by feedback loops and interdependencies among materials, energy, infrastructure, and human behaviour. Rather than viewing waste flows in isolation, this lens examines how council decisions, community behaviour, and infrastructure capacity interact over time [

29,

30,

31]. As highlighted by Orgill et al. [

32], systems thinking promotes holistic analysis by focusing on emergent system-level properties that arise from the organisation and interrelationships of the parts, while Vuorio et al. [

33] demonstrate its pedagogical and analytical value in addressing complex socio-scientific issues such as sustainability and participatory governance.

Applying these insights in a municipal context enables this study to investigate not only what local councils do, but also how institutional structures, feedback dynamics, and inter-jurisdictional linkages sustain or constrain transitions toward circularity.

Integrating these two perspectives enables dual-scale explanation: environmental-governance theory clarifies why uneven performance emerges across jurisdictions (through institutional and fiscal asymmetries), whereas systems thinking explains how these disparities evolve through interacting subsystems of policy, infrastructure, and community engagement. Together, they provide an analytical foundation for examining resource–energy coupling, service-delivery equity, and systemic barriers to circularity.

Figure 1 summarises this integrated framework, linking national-policy inputs, state-level mediation, and local-government processes with resulting material- and energy-recovery outcomes. The feedback arrows illustrate how funding mechanisms, data transparency, and citizen participation reinforce or weaken system performance over time.

Recent studies [

34,

35] corroborate the value of such integrative approaches, showing that circular-economy success depends as much on governance coherence and adaptive feedback learning as on infrastructure investment. This theoretical alignment ensures that the empirical findings presented in

Section 3 are interpreted through a systems-informed understanding of multi-level environmental governance.

3. Results

3.1. Waste Management Practices and Household Bin Colour-Coding System in Australian Councils

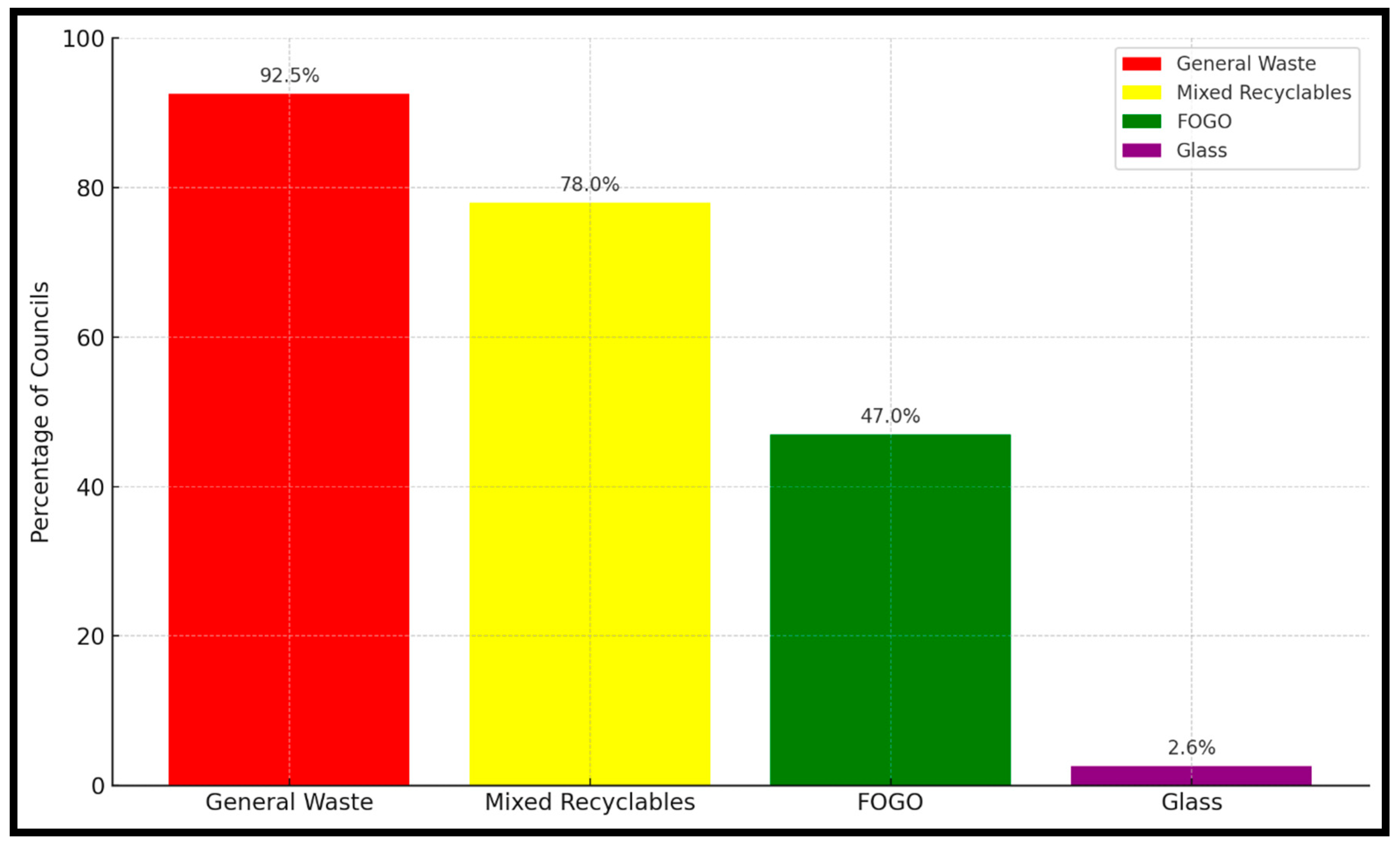

All 520 councils, except for 10 in Queensland and 17 in Western Australia, maintain dedicated information on their council’s websites for waste management, which highlights their commitment to providing vital information on household waste management to the public. As illustrated in

Figure 2, which presents the percentage of councils providing each type of bin, a significant majority 481 of the 520 councils (92.5%) offer general waste bins, while approximately 47% (246 councils) provide FOGO bins and around 78% (406 councils) supply mixed recyclable bins. The remaining 39 councils (7.5%) that do not offer general waste bins typically operate under alternative waste management models. These may include regional or remote areas where household waste collection is managed through community drop-off points, shared waste facilities, or contracted third-party services rather than individual kerbside bin provision. In some cases, these councils may provide limited or specialized waste collection on request, but not a standardized general waste bin service. However, just 2.6% (14 councils), exclusively from Victoria, have implemented separate bins for glass waste, representing a mere 2.6% of the total councils studied.

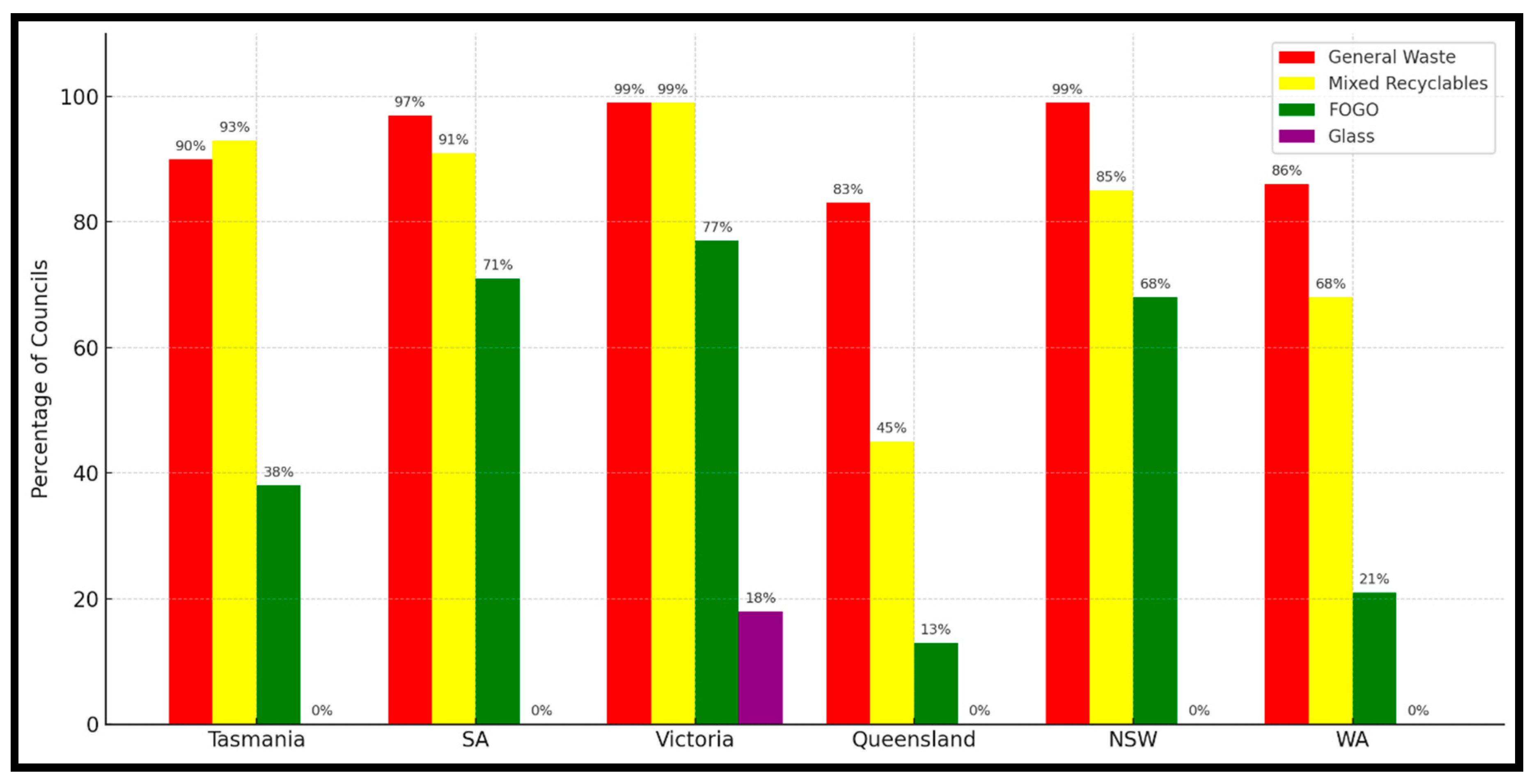

In

Figure 3, the percentage of bins available in each state is depicted. In Tasmania, among the 29 councils, 90% (26) have general waste bins, 38% (11) have FOGO bins, and 93% (27) have mixed recyclable bins. South Australia has 97% (66) of councils with general waste bins out of a total of 68, 71% (48) have FOGO bins, whereas 91% (62) provide mixed recyclable bins. In Victoria, 99% (78) of councils have general waste bins, 77% (61) offer FOGO bins, and 99% (78) provide mixed recyclable bins, with 18% (14 councils) offering glass waste bins. Moving to Queensland, 83% (64) of its 77 councils have general waste bins, 13% (10) offer FOGO bins, and 45% (35) provide mixed recyclable bins. In New South Wales, out of 128 councils, 99% (127) offer general waste bins, 68% (87) have FOGO bins, and 85% (109) provide mixed recyclable bins. Last, in Western Australia, 86% (120) of its 139 councils offer general waste bins, 21% (29) have FOGO bins, and 68% (95) provide mixed recyclable bins.

Out of 520 councils in Australia, 483 consistently use a colour-coding system for waste and recycling containers, whereas 37 do not. This method typically assigns red for general waste, green for FOGO waste, yellow for mixed recyclables and purple for glass waste, ensuring clarity and consistency in waste management practices among various municipalities. However, there are some exceptions a minority of councils in each state do not adhere to this standardized colour scheme. In Australia, there are no specific regulations mandating uniform bin colours nationwide.

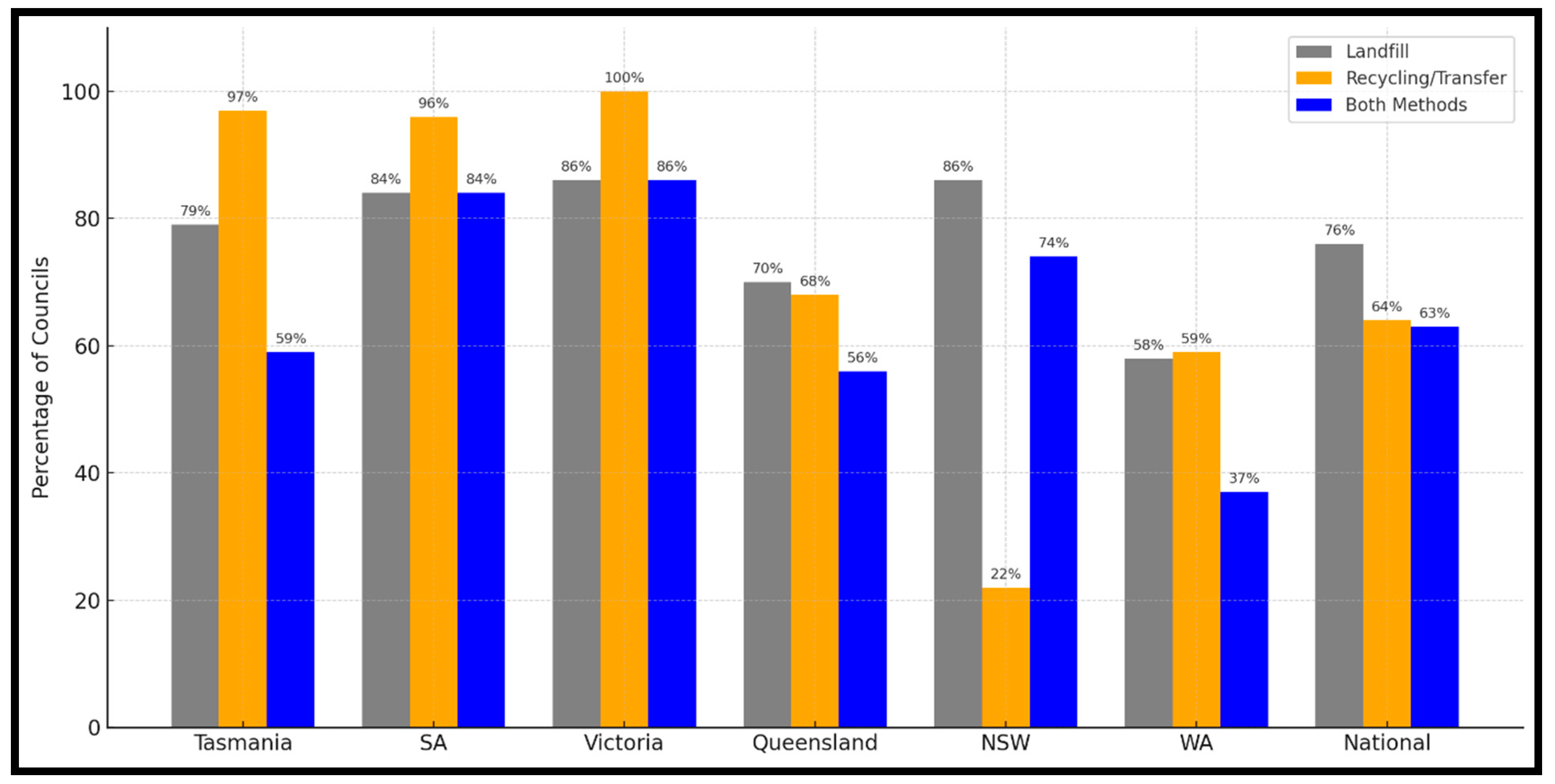

3.2. Waste Management Protocols Across Australian Councils

Of the 520 councils, 76% (393) opt for landfill disposal, 64% (334) participate in recycling or transfer practices, and 63% (331) incorporate both methods. The remaining 24% (127 councils) that do not utilise landfill disposal typically rely on alternative arrangements such as regional waste-sharing agreements, private contractors, or the use of transfer stations that consolidate waste for transport to landfill sites outside their jurisdiction. These solutions are often adopted in regions where direct landfill access is limited due to geographic isolation or environmental constraints. Similarly, the 36% (186 councils) not engaged in recycling or transfer practices may rely on regional partnerships or outsourced services to manage recyclables, rather than maintaining local infrastructure. Taken together, these patterns highlight that waste treatment systems are shaped not only by policy choices but also by geographic scale, fiscal capacity, and access to processing infrastructure. This variation is further illustrated in

Figure 4, which shows clear cross-state contrasts in the combined adoption of landfill and recycling/transfer pathways.

In Tasmania, out of its 29 councils, 79% (23) opt for landfill disposal, whereas 97% (28) divert recyclables for either recycling or transfer. Notably, 59% (17) councils have chosen to implement both waste treatment options, with just one council not utilising either.

In South Australia, 84% (57) of its 68 councils send waste for landfill disposal, and 96% (65) direct recyclables for recycling or to transfer stations. A total of 84% (57) councils has integrated both treatment options, while 4% (3) councils have not adopted either approach.

In Victoria, out of 79 councils, 86% (68) utilise landfill disposal and 100% (79) participate in recycling practices. Here, 86% (68) have incorporated both options, indicating a relatively mature waste management system underpinned by well-developed infrastructure and long-standing source-separation practices.

Figure 4 indicates clear cross-state contrasts in the combined adoption of landfill disposal and recycling/transfer strategies. Victoria exhibits the highest share of councils integrating both options (86%), signalling comparatively mature dual-stream processing capacity. South Australia also shows relatively high dual adoption, consistent with its long-established emphasis on source separation and container deposit schemes. In contrast, Western Australia records the lowest dual adoption (37%), and Queensland shows similarly constrained dual uptake, reflecting wider geographic dispersion, higher service delivery costs, and thinner infrastructure footprints. “Landfill-only” councils cluster in Queensland and Western Australia, while “recycling/transfer-only” arrangements are comparatively rare and typically emerge in regional hub-and-spoke service models. Taken together,

Figure 4 suggests a structural gradient in waste treatment capability: states with denser processing networks and established shared-service institutions (e.g., Victoria and South Australia) are more likely to provide residents with both landfill and diversion pathways at council scale, whereas states characterised by sparse populations and long transport distances have fewer councils able to sustain full dual-stream systems.

Meanwhile, among Queensland’s 77 councils, 70% (54) send waste for landfill disposal and 68% (52) dispatch recyclables for recycling or transfer. However, only 56% (43) have adopted both treatment options, reflecting geographic and resource constraints.

In New South Wales, which has 128 councils, 86% (110) opt for landfill disposal, while 74% (94) have implemented both landfill and recycling/transfer strategies. This highlights substantial diversity, influenced by urban–rural differences and regional infrastructure distribution.

In Western Australia, 58% (81) of its 139 councils opt for landfill disposal, and 59% (82) use recycling centres or transfer stations. However, only 37% (52) have adopted both pathways, illustrating marked variation in service maturity across remote and sparsely populated regions.

3.3. Waste Management and Circular Economy Projects Across Australia

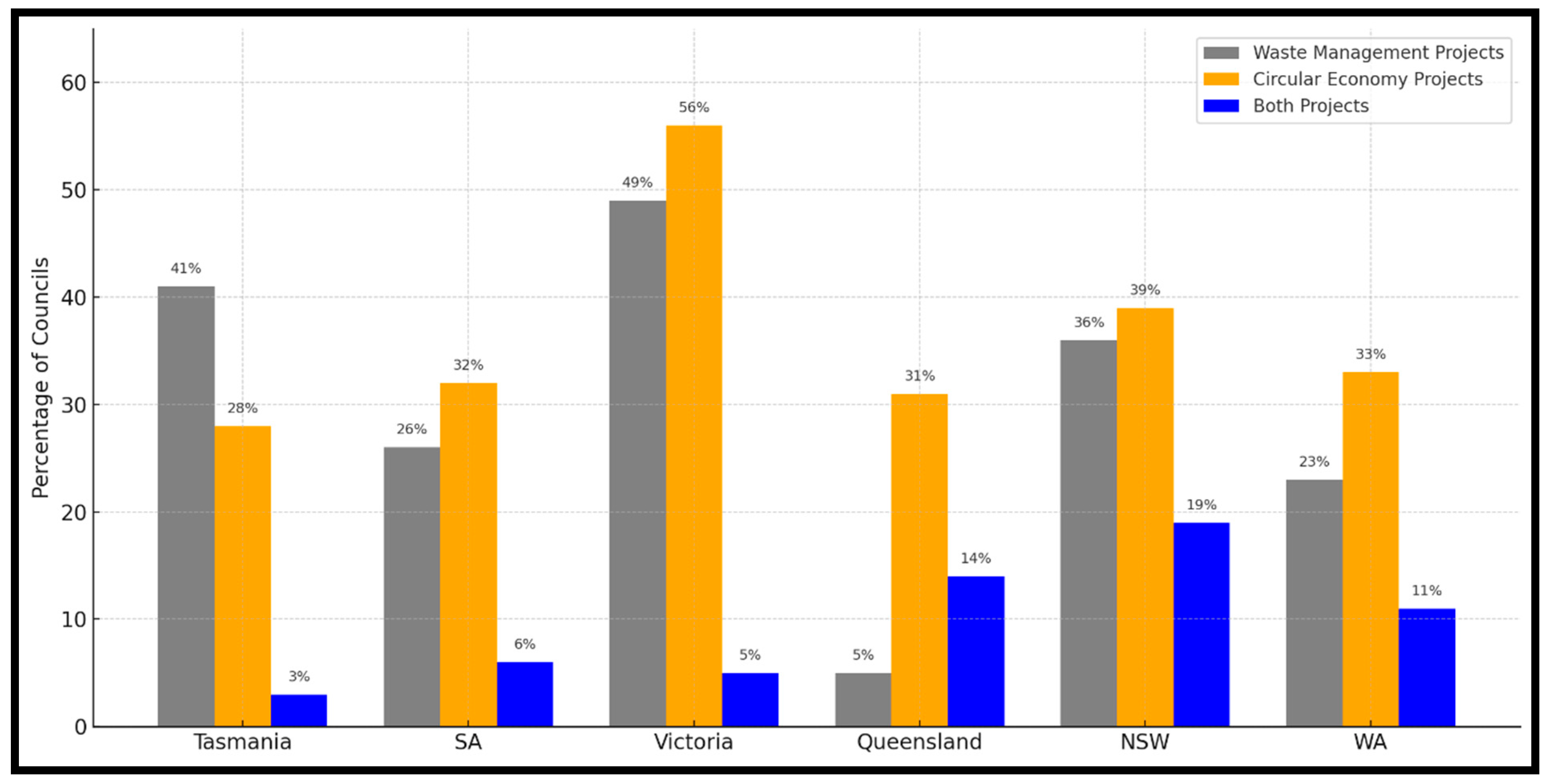

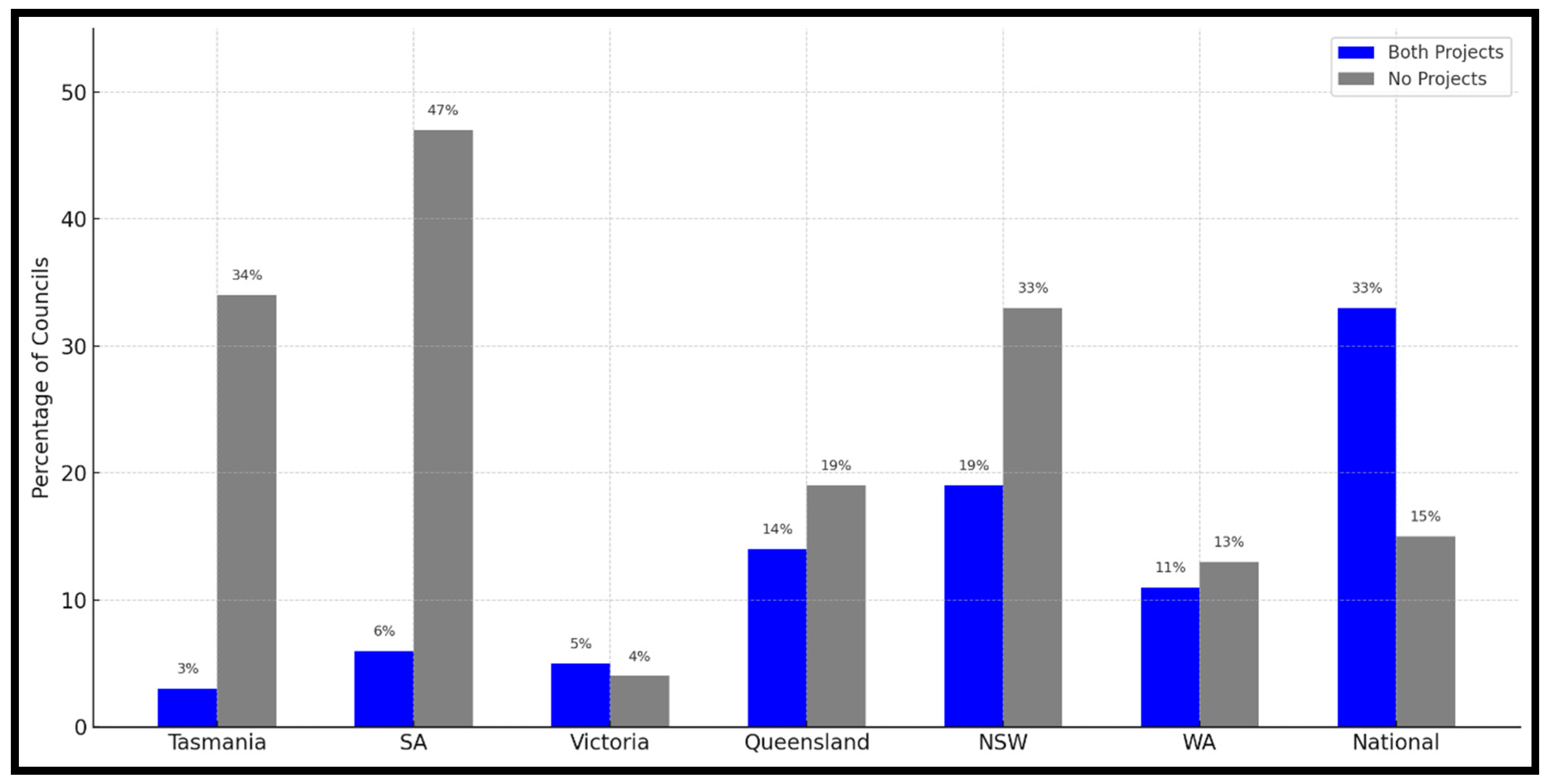

At the national scale, 33% (171) councils out of the total 520 are actively involved in both waste management and circular economy (CE) projects. A further 37% (194) participate only in waste management initiatives, while 11% (59) undertake CE projects without a linked waste management program. Notably, 15% (80) of councils have not engaged in either type of initiative, highlighting uneven program uptake across jurisdictions. These patterns are illustrated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, which show the distribution and co-occurrence of waste management and CE project involvement across states.

In Tasmania, 41% (12) councils are dedicated to waste management projects, and 28% (8) are actively working on CE projects. Only one council (3%) undertakes both, while 34% (10) have not initiated either, suggesting that capacity and market access may constrain diversification into circular practices.

Figure 5 indicates that CE engagement is most concentrated in Victoria and New South Wales, where councils participate in a broader portfolio of initiatives such as organics diversion, reuse marketplaces, recycled-content procurement, and product stewardship programs. This pattern aligns with stronger state-level CE policy frameworks and deeper market demand for recovered materials. In contrast, Tasmania and much of Western Australia display narrower portfolios that focus primarily on organics reduction and community education, suggesting that CE implementation is closely shaped by policy support, infrastructure availability, and the maturity of local end markets for secondary materials.

In South Australia, 26% (18) councils focus on waste management initiatives, while 32% (22) are dedicated to CE projects. Only 6% (4) demonstrate engagement in both domains, and 47% (32) councils currently participate in neither, reflecting considerable intra-state variability despite South Australia’s long-standing history of resource recovery policy.

In Victoria, 49% (39) of the 79 councils pursue waste management projects and 56% (44) engage in CE initiatives. A small share, 5% (4), undertake both types of projects concurrently, and only 4% (3) show no involvement in either area. This suggests a relatively mature implementation environment supported by statewide strategic guidance and shared-service structures.

In Queensland, 5% (4) councils undertake waste management projects and 31% (24) engage in CE projects. A further 14% (11) participate in both, while 19% (15) have not yet initiated programs in either domain, reflecting infrastructure dispersion and capacity differentials across the state.

In New South Wales, 36% (46) councils focus on waste management initiatives, and 39% (50) are engaged in CE initiatives. Notably, 19% (24) integrate both areas into their operations, while 33% (42) councils have not yet adopted either approach, indicating uneven implementation despite a comparatively large and diverse council population.

In Western Australia, 23% (32) councils undertake waste management projects and 33% (46) participate in CE initiatives. Only 11% (15) integrate both, while 13% (18) have not adopted either. This reflects the effect of geographic scale, long transport distances, and limited regional processing capacity on program rollout.

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarise these councils’ waste management and circular economy projects, respectively, and include the number of similar projects across Australia.

As reflected in

Table 1, a key focus of many local councils is the delivery of waste education, which is recognized as central to facilitating behavioral change an inherently complex and gradual process. Consumer awareness is critical to supporting the transition toward circular economy (CE) practices, as it enables individuals to make informed choices and participate in sustainable behaviors. Boulton et al. emphasize that educated consumers can influence institutions and industries to align their operations with sustainability objectives [

26]. Given that household consumption contributes to approximately 25% of total waste generated, targeted education becomes a strategic tool for minimizing environmental impact.

Despite various initiatives, many Australian households still struggle with effective waste practices. McKay et al. highlight issues such as contamination in co-mingled recycling bins and the high proportion of organic material around 40% found in landfill-bound waste streams [

27]. These challenges contribute to emissions and undermine recycling outcomes, further underscoring the value of public education in promoting waste separation and composting behaviors.

In addition,

Table 1 reveals that while 22 councils have developed waste management plans addressing operations and outreach, only five have adopted formal waste policies reflecting strategic, long-term commitments. This policy gap indicates a disconnect between practical waste handling and its institutional embedding, potentially due to the absence of regulatory mandates.

For rural councils, logistical and financial constraints often limit program scale. In these contexts, mobile applications offer an effective alternative for public engagement, enabling real-time updates and guidance that can overcome geographic and resource barriers in waste education and service delivery.

A prominent area of circular economy (CE) action among Australian local councils is the management of food organics and garden organics (FOGO) waste. Councils frequently address this through the provision of dedicated FOGO bins, supported by complementary initiatives such as composting and farming. These approaches align with broader CE goals by diverting biodegradable waste from landfill and enabling nutrient recovery at the community level. As McKay et al. highlight, households play a crucial role in all phases of waste management, including waste reduction, reuse, and recycling behaviors [

27]. Engaging households is therefore essential to CE implementation at the municipal scale.

To enhance this engagement, many councils are leveraging interactive online tools that support residents in adopting correct sorting practices, preventing contamination, and adopting home composting methods. These digital platforms offer scalable and cost-effective education solutions, particularly vital in rural and remote communities where traditional outreach is constrained by geography. Given the ubiquity of mobile technology, digital engagement strategies provide a flexible mechanism for behavior change aligned with CE principles.

In addition to FOGO management, councils are increasingly participating in targeted CE programs that promote resource recovery and waste avoidance. For instance, 15 out of 520 councils (2.88%) currently engage in drumMUSTER, a national program that facilitates the recycling of agricultural chemical containers. Another five councils (0.96%) participate in Love Food Hate Waste, a campaign aimed at minimizing food waste through household education and meal planning. Furthermore, 13 councils (2.5%) provide rebates for cloth nappies and reusable sanitary products, while 24 councils (4.68%) actively promote the core CE practices of reduce, reuse, and recycle.

To extend product life cycles and foster a reuse culture, councils also support platforms such as ASPIRE and Ziilch, which enable the trade and exchange of unwanted goods. Other initiatives include Mobile Muster for mobile phone recycling, textile recycling schemes, and the promotion of second-hand retail markets. These markets such as op shops (charity-run thrift stores) encourage circular consumption by providing low-cost, reused goods and reducing the demand for virgin materials.

Programs like Love Food Hate Waste, originally launched in the United Kingdom in 2007, have since gained traction in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada [

28]. By guiding households through food planning, portion control, and leftover use, the initiative contributes to both food waste reduction and household savings. Meanwhile, drumMUSTER has become a leading model in agricultural waste recycling by offering clean, traceable disposal options that align with environmental safety standards and quality assurance systems [

29].

Collectively, these initiatives support the seven national targets set under Australia’s National Waste Policy Action Plan [

15], including waste export bans, reduced per capita waste generation, an 80% resource recovery rate, increased use of recycled content, phasing out problematic plastics, halving organic landfill waste, and improving data transparency.

To further these efforts, councils can adopt emerging Industry 4.0 technologies such as real-time monitoring, smart bins, and automation to enhance efficiency and responsiveness, as suggested by Fatimah et al. [

30]. Additionally, councils may introduce CE certification programs to incentivize businesses, support circular procurement, and promote collaboration with industries and NGOs. Such partnerships are vital in scaling systemic transformation and aligning local action with global CE and SDG objectives.

3.4. Comparison of Metropolitan and Rural Councils in Waste Management and Circular Economy Practices

Significant distinctions exist between metropolitan and rural councils in Australia in their engagement with waste management and circular economy (CE) practices. These differences are shaped by population density, distance to processing infrastructure, local operating capacity, and access to stable funding. Across all states, rural councils greatly outnumber metropolitan councils, a pattern seen in New South Wales (95 of 128 councils are rural), Victoria (48 of 79), Western Australia (109 of 139), Queensland (58 of 77), South Australia (51 of 68), and Tasmania (23 of 29). This demographic composition has direct implications for service design and circular economy implementation, as smaller rate bases and dispersed settlements increase per-household waste service costs.

Metropolitan councils typically exhibit more advanced and diversified waste systems, often providing general waste, co-mingled recycling, and food organics and garden organics (FOGO) collection. In Victoria, every metropolitan council provides both general waste and recycling services, compared to approximately 85% of rural councils. Specialised services, such as glass-only purple bins, also remain largely metropolitan, with 2.6% of Victorian councils adopting them all in urban areas.

In contrast, rural councils face structural barriers including lower population density, geographic isolation, and limited access to processing facilities. For example, in South Australia, 95% of metropolitan councils provide FOGO, compared to 45% of rural councils, reflecting persistent equity and capacity gaps in service access.

Table 3 clarifies the metropolitan–rural gradient in project delivery. Nationally, metropolitan councils account for 56% of all waste management projects and 59% of all CE projects. This metropolitan concentration is most pronounced in New South Wales and Victoria, where proximity to recycling hubs and deeper end-markets for recovered materials enable councils to implement broader CE portfolios. In Western Australia, however, the distribution is more balanced and slightly rural leaning due to the state’s high reliance on regional service models and shared infrastructure. These differences indicate that capacity, scale, and market access are primary drivers: metropolitan councils are generally able to adopt multi-initiative CE programs, while rural councils participate where regional sharing arrangements or targeted funding reduce per capita costs. In other words, spatial disadvantage is closely tied to technical disadvantage; councils furthest from processing hubs face the greatest barriers to implementing high-value CE and energy recovery pathways.

A nationwide overview reinforces this divide. Metropolitan councils are more likely to manage e-waste programs, resource recovery centres, reuse marketplaces, and large-scale behaviour change campaigns, often supported by national frameworks such as MobileMuster and Love Food Hate Waste. Rural councils, while committed to environmental stewardship, tend to undertake more localised or education-focused CE activities, as financial and operational constraints limit infrastructure-intensive initiatives.

The resulting pattern reflects energy–infrastructure path dependence: metropolitan councils test higher-complexity initiatives (organics-to-energy, glass separation, e-waste hubs), because their population density supports economies of scale and market demand. Rural and remote councils frequently rely on regional transfer stations and contracted haulage, which limits the feasibility of advanced circular and energy recovery functions such as biogas capture or thermal treatment.

Addressing these structural inequities requires multi-level policy support, including shared-service processing hubs, targeted co-funding for rural organics and small-scale energy recovery, and capacity-building partnerships with state agencies and industry. Only by reducing spatial and technical disadvantages can circular economy opportunities be extended equitably across urban and rural landscapes.

3.5. Waste-to-Energy and Resource–Energy Recovery

A circular economy is not limited to “collect–sort–recycle”; it also includes recovering energy value from residual and organic waste streams. As part of this study, councils were reviewed for any reference to waste-to-energy (WTE) processes such as anaerobic digestion for biogas, landfill gas capture for electricity generation, thermal treatment of residual waste, or advanced sorting and separation for high calorific-value fractions. Fewer than 10% of councils publicly reported involvement in, or access to, any such energy recovery initiative.

Where energy recovery was mentioned, it was most often described in two forms: (i) organics-to-energy pathways such as biogas, typically linked to food organics and garden organics (FOGO) or other organic processing; and (ii) recovery of energy or fuel value from residual municipal solid waste through high-temperature treatment or gas capture. These activities were more frequently referenced by metropolitan councils in larger states (e.g., Victoria and New South Wales) than by small rural or remote councils.

Rural councils commonly described barriers to participating in energy recovery, including high capital cost, the need for specialised operators, limited local demand for recovered energy, and uncertainty about long-term offtake agreements. Councils in remote areas also highlighted workforce shortages and distance to processing infrastructure as major constraints.

Several councils explicitly linked these barriers to funding design. Although national and state programs promote “circular economy innovation,” local governments reported difficulty accessing capital co-funding, long-term operating support, or specialized technical staff for high-temperature processing, anaerobic digestion, or landfill gas valorisation. In governance terms, this represents a classic implementation gap: higher tiers of government frame waste-to-energy and organics-to-energy as strategic levers for meeting 2030 circular economy and emissions targets, but operational responsibility is devolved to councils that often lack the financial and technical capacity to deliver those levers on a scale.

These patterns indicate that energy recovery is emerging but remains uneven, particularly in regional and remote jurisdictions. From an environmental governance perspective, this unevenness reflects asymmetric responsibility: councils are expected to divert organics from landfill and generate low-carbon energy, but enabling infrastructure, long-term funding certainty, and specialized labor are concentrated in metropolitan or well-resourced councils. It also aligns with a systems thinking view, in which technical capacity, market demand, behavior, and regulatory support interact as a single system: unless all parts work together, the loop does not reinforce itself [

34,

35]. In other words, weak links in funding or technical capability prevent the energy–resource loop from stabilising as part of councils’ normal waste operations, especially outside metropolitan areas.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study shed light on the current state of waste management practices and circular economy initiatives at the local government level in Australia. The following discussion contextualizes the results within the broader national and global literature, identifies areas of contradiction or alignment with the literature and outlines implications for further research, policy and practice. It also acknowledges some limitations of this study.

4.1. Local Council’s Role in Circular Economy

The study emphasizes that Australian local councils play a crucial role in waste management and circular economy initiatives. This finding is consistent with that of the literature, which indicates that local councils are pivotal in promoting sustainability practices. Many councils demonstrate their commitment to transparency and public engagement by maintaining dedicated webpages for waste management, a practice supported by studies highlighting the importance of accessible information for public participation [

31]. Moreover, the prevalent implementation of a standard colour-coding system for bins, although not mandatory, aligns with literature suggesting that such measures significantly enhance public understanding and reduce contamination risks [

32]. This alignment with the extant literature underscores the effectiveness of local council strategies in fostering circular economy practices. Across

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 and

Table 3, the descriptive contrasts are consistent: states with denser recovery markets and stronger policy scaffolds (e.g., Victoria, New South Wales) host more councils delivering dual landfill–recycling options and broader CE portfolios, with metropolitan councils carrying the greatest share of project load.

These findings support the proposition, drawn from environmental governance theory, that local governments are required to deliver circular economy functions under national targets, but do so with uneven funding and institutional capacity; and from systems thinking, that household behavior, service design, and infrastructure performance are interdependent rather than isolated.

Moreover, the study highlights the diverse waste management practices among Australian local councils, emphasizing the dual focus on landfill disposal and recycling centers. While many councils prioritize landfill disposal, others engage in recycling and transfer stations, with a notable number adopting a hybrid approach. This diversity in practices underscores the unique challenges and priorities each council faces, influenced by factors such as geographical constraints, land availability, and transportation logistics. The collaborative use of landfill sites, such as the Corangamite Regional Landfill in Southwest Victoria, which serves multiple councils, including Corangamite Shire and Warrnambool City Council, exemplifies the resource-sharing strategies employed to address these challenges. This collective approach reflects the necessity for customized waste management solutions tailored to the specific needs and capacities of different regions, highlighting the critical role of inter-council cooperation in optimizing waste management and advancing circular economy initiatives.

Circular economy projects, particularly those related to FOGO waste, emerge as a significant focus for many councils. Initiatives such as Love Food Hate Waste and drumMUSTER highlight their multifaceted efforts to reduce waste, promote recycling and engage the community, which reflect global initiatives to decrease food waste and promote recycling in various contexts [

29,

33]. Councils’ proactive approach to waste education demonstrates the importance of consumer awareness in creating sustainable behaviors. This approach is consistent with literature, which emphasizes the role of consumer education in supporting sustainable practices. According to prior studies, raising consumer awareness through educational programs is critical for supporting appropriate waste management and recycling practices [

34,

35]. Councils actively engaged in waste education adhere to evidence-based practices that improve public understanding and participation in sustainability activities.

Furthermore, the study emphasizes the critical role of local councils in waste management and circular economy programs, consistent with studies that have highlighted the necessity of decentralized governance structures in tackling environmental concerns [

36]. The proactive involvement of councils in disseminating waste education is also consistent with studies that have highlighted the importance of consumer awareness and behavior change in achieving sustainability [

25,

26,

37]. In addition, this study’s findings on disparities among councils in waste management methods echo concerns raised in the literature about the uneven distribution of resources and the capacity constraints faced by local authorities [

31,

36,

37,

38,

39].

This Australian pattern is consistent with recent international research showing that municipal waste and circular economy systems tend to underperform when responsibility is devolved to local authorities without matching technical capability, financial stability, or citizen engagement structures. In Nigeria, for example, circular economy ambitions in municipal solid waste management remain largely aspirational because local governments face chronic infrastructure deficits, weak enforcement capacity, and fragmented funding, producing what has been described as a systemic implementation failure rather than a purely technological gap [

40]. Similarly, large-scale municipal waste sorting reforms in China demonstrate that national targets alone are insufficient; successful household sorting depends on whether local governments can mobilize residents, provide sorting infrastructure, and maintain ongoing behavioral compliance [

41]. These findings reinforce the argument that circular economy delivery is fundamentally a governance-capacity challenge, not just a matter of installing bins or drafting plans [

38,

40,

42,

43].

4.2. Challenges and Disparities

This study identifies several challenges and disparities in waste management practices among local councils, particularly with regard to the uneven adoption of circular economy initiatives. The limited implementation of formal waste management policies, as highlighted in

Table 2, indicates a potential gap in policy enforcement or a lack of mandatory directives from higher authorities [

40,

41]. Financial constraints, especially in rural areas, are a significant barrier to the successful implementation of circular economy projects [

42,

43]. This financial limitation is consistent with existing literature, which underscores the socioeconomic complexities influencing waste management [

44]. Disparities in the adoption of circular economy initiatives are evident. As

Table 1 indicates, only 33% of councils actively participate in circular economy projects, while a notable portion of councils either focus solely on waste management or lack initiatives altogether. In many cases, councils engaged in such projects may not explicitly identify their activities as part of the circular economy, reflecting a limited understanding of the paradigm. This gap suggests a need for further capacity building to align council operations with the broader goals of circularity. For rural and remote councils, logistical challenges such as waste collection difficulties and increased costs further hinder their ability to engage effectively with circular economy practices. This aligns with findings from previous studies, which show that smaller councils with limited population sizes or geographic isolation face disproportionate hurdles to implementing sustainable practices [

45,

46]. The metropolitan–rural differences visible in

Table 3 are therefore better understood as capacity and market-access gaps rather than behavioral gaps, underscoring the need for targeted co-funding, regionalised expertise, and reliable end-markets if rural councils are to expand beyond education-only initiatives.

Moreover, the ongoing challenge of contamination within Food Organics and Garden Organics (FOGO) waste streams remains a critical issue.

Table 1 highlights that 22 councils have introduced FOGO bins, yet the improper use of plastic bags in kitchen caddies rather than compostable alternatives has led to contamination, thereby complicating the composting process. The Camperdown compost facility, for instance, has encountered contaminated green waste, which not only lowers compost quality but also necessitates additional labour for sorting, thus increasing operational costs. Addressing these issues requires targeted waste education, as outlined in

Table 1, where councils are placing a growing emphasis on public education initiatives to mitigate improper waste disposal. This proactive strategy aligns with findings that consumer awareness plays a pivotal role in influencing waste management behaviors and the overall success of circular economy initiatives [

47,

48].

The disparity in formal waste management policies, as seen in

Table 2, further complicates the ability of councils to uniformly implement waste and circular economy projects. While 22 councils have waste management plans, only five have adopted formal policies, suggesting a lack of regulatory pressure for mandatory adherence to national and state-level waste management directives. In rural areas, councils have cited financial infeasibility, low population density, and logistical challenges as reasons for not pursuing circular economy projects, as exemplified by the Shire of Ngaanyatjarraku and Wujal Wujal Aboriginal Shire Council [

49,

50]. A related constraint is the limited diffusion of energy recovery technologies. Only a small subset of councils referenced anaerobic digestion, landfill gas capture, or high-temperature residual treatment. Councils repeatedly framed these technologies as financially and operationally ‘out of reach,’ describing high upfront capital requirements, specialist operator shortages, and uncertainty around energy or compost markets. This confirms that the circular economy is not only about “recycling more,” but also about overcoming structural barriers to resource–energy coupling at the local scale.

While there is a positive trend towards introducing separate bins and promoting waste reduction initiatives, a concerted effort is required to address these financial, logistical, and educational challenges. Encouraging a broader understanding and adoption of circular economy principles, alongside providing adequate support and resources, will be crucial for ensuring the success of circular economy projects across diverse council settings.

4.3. Opportunities for Improvement

The study identifies several opportunities for improving waste management and advancing circular economy initiatives at the local government level in Australia. The success of the Love Food Hate Waste, MobileMuster, drumMUSTER and cloth nappy rebate programs suggests the potential for collaboration and knowledge sharing among councils. Establishing a platform for councils to share best practices, success stories and challenges can facilitate a collective, informed approach to the circular economy. State governments can draw inspiration from programs such as Resource Smart Schools organized by Sustainability Victoria, which is a state government initiative. This program conducts regular online sessions for school officers, educating them about sustainability projects within schools [

51]. Similarly, a comparable approach can be implemented at the council level to educate, promote and monitor circular economy initiatives. This would involve the active participation of sustainability officers, circular economy officers and waste management officers within the councils.

Encouraging councils to adopt formal waste management policies by providing support or incentives can contribute to a more standardized and comprehensive approach. In addition, exploring innovative waste management systems, as suggested by Fatimah et al. [

30,

52], could enhance efficiency and sustainability. Moreover, establishing circular economy certification programs and collaborating with businesses and NGOs can present avenues for councils to strengthen their impact and promote sustainable practices.

Based on these results, three immediate policy levers emerge. First, targeted state–federal co-funding for rural organics processing and small-scale energy recovery (e.g., anaerobic digestion, landfill gas capture) would help correct the current structural gap by treating organics diversion and energy valorization as critical infrastructure, not optional innovation. Second, shared-service or regional hub models for technical expertise (including compliance, contamination management, and market development for recovered products/energy) would reduce the personnel barrier repeatedly identified by smaller councils. Third, standardised circular economy reporting requirements would improve transparency and enable benchmarking across councils, which is essential for tracking progress toward 2030 targets and for identifying where intervention is most urgent.

4.4. Alignment with National Targets

The study highlights how local council initiatives align with the seven national targets outlined in the National Waste Policy Action Plan. Council efforts, including the ban on waste exports, the reduction in total waste generation and landfill and the promotion of recycled content, showcase their concerted contributions to national sustainability goals [

14,

53,

54]. The emphasis on comprehensive data availability aligns with the transparency demonstrated by councils through dedicated web pages. Achieving the targets set under the National Waste Policy Action Plan is feasible if all councils collectively put forth efforts. However, essential financial, knowledge-related and other forms of support from the state and federal levels are crucial for success. In particular, the uneven distribution of FOGO services, the very limited uptake of energy recovery pathways, and the absence of formal waste policies in many councils together place at risk the Action Plan’s goals of achieving an 80% recovery rate and halving organics to landfill by 2030.

4.5. Limitations of the Study

This study relied primarily on publicly available council documents and website data, which, although comprehensive, may omit informal or unpublished local initiatives. The lack of access to internal records, operational data, and longitudinal datasets limits the ability to assess causal relationships or to verify implementation outcomes. Inferential statistical tests (such as chi-square or ANOVA) were considered; however, given the descriptive and census-level design of the study and the absence of consistent quantitative operational data across councils, descriptive statistics were the most appropriate approach for accurately characterizing national patterns.

Methodologically, the study applied descriptive and content-analytic approaches rather than inferential statistical testing. While appropriate for mapping trends across all 520 councils, future studies could employ statistical significance testing to examine state- and region-level variation in service provision and circular-economy adoption.

In addition, this research did not integrate geospatial or energy-endowment datasets that could illuminate spatial coupling between energy resources and waste management models which could be consider as a key future direction. Incorporating spatial and energy-system variables would help to capture the full resource–energy synergy envisioned in circular-economy frameworks.

The study also did not include stakeholder interviews or qualitative triangulation, which would add depth to understanding the governance, behavioural, and institutional dynamics underlying observed disparities. Such mixed-methods research could reveal the mechanisms linking funding design, technical capability, and policy outcomes across council contexts.

Finally, because the dataset reflects conditions between June and September 2024, the results should be interpreted as a snapshot rather than a fixed evaluation. Rapid policy and technological shifts may alter the circular-economy landscape; hence, longitudinal monitoring and cross-country comparative studies (e.g., Nigeria, China) are recommended to validate and extend these findings.

4.6. Implications for Further Research, Policy and Practice

In future studies, it would be beneficial to investigate the dynamic nature of local councils, considering changes in names, boundaries and administrative structures over time and how these alterations affect waste management practices. In addition, conducting in-depth case studies of selected councils would provide a deep understanding of challenges and opportunities, through interviews, onsite observations and closer examination of project implementations. Exploring waste management practices in internal and external territories, as well as remote areas, could offer insights into unique challenges faced in different regions. Investigating the impact of legislative changes on waste management practices, assessing the effectiveness of regulatory frameworks, and conducting longitudinal studies to track the progress of councils over time would contribute to a comprehensive understanding. Evaluating the effectiveness of community engagement and awareness programs initiated by councils and undertaking a comparative analysis with international councils that have successfully implemented circular economy initiatives would provide valuable lessons for improvement in Australia. Addressing these research avenues can contribute to a more holistic understanding of waste management practices at the local government level and further enhance the effectiveness of circular economy initiatives in Australia.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides a robust examination of waste management practices and circular economy initiatives at the local government level in Australia. Seven years after the inception of the National Waste Policy and with five years remaining to meet the 2030 targets, this study underscores the dedication of the majority of councils towards disseminating crucial information on household waste management. Notably, this commitment extends across most regions, with only a small percentage of municipalities lacking resources, primarily observed in Queensland and Western Australia. While the widespread distribution of bins for general waste, FOGO, and mixed recyclables showcases a concerted effort to meet community needs, the limited adoption of separate glass waste bins reflects an area with both potential and complexity. A dedicated glass stream can indeed improve recycling efficiency by reducing contamination and increasing material purity. However, it also poses logistical and environmental challenges, including the need for separate collection fleets, additional operational costs, and increased vehicle emissions. Moreover, glass is often efficiently sorted in many municipal recovery facilities. Therefore, while expanding glass-only services could yield environmental benefits in certain contexts, its broader implementation requires careful consideration of local infrastructure, cost–benefit trade-offs, and environmental impacts.

This study underscores both achievements and areas for improvement in waste management and circular economy initiatives among Australian local councils. Looking ahead, targeted efforts to bolster recycling infrastructure, promote circular economy principles and foster collaboration between councils, businesses and NGOs are imperative for realising a more sustainable and circular economy nationwide. The introduction of innovative technologies, such as mobile applications, signals councils’ commitment to embracing new avenues to engage residents in a more accessible manner, thus propelling the nation towards a greener future [

55,

56].

Taken together, the results show that Australia’s circular economy transition is not only a technical challenge of bins, sorting, and infrastructure, but a governance problem: responsibilities for achieving national targets have been devolved to councils whose fiscal capacity, staffing depth, and access to processing technology vary widely. In systems terms, this produces weak or broken feedback loops in rural and remote areas, where councils cannot easily convert community participation and collected organics into stable recovery streams or local energy value [

57,

58].

Without targeted financial support for rural councils, clearer governance alignment across levels of government, and investment in organics recovery and energy recovery infrastructure, Australia’s 2030 circular economy and landfill diversion targets are unlikely to be achieved in an equitable way.