Abstract

To enhance the design and construction efficiency of artificial ground freezing (AGF) in water-rich sandy strata, this study takes the No. 2 cross-passage of Zhengzhou Metro Line 8 as a case study and conducts an integrated analysis combining field monitoring and numerical simulation. During the freezing process, a sensor network was deployed to capture real-time data on temperature distribution and pore water pressure evolution. Based on the collected measurements, a three-dimensional hydrothermal coupled model was developed using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.1 and validated against field data. The results demonstrate a distinct multi-stage evolution in the formation of the frozen curtain, with the highest heat exchange rate observed at the initial phase. Under a 50-day freezing schedule, increasing the average coolant temperature by 4 °C still yielded a frozen wall that meets the design thickness requirement. Additionally, several cost-effective freezing schemes were explored to accommodate varying construction timelines. This study supports sustainable urban infrastructure development by minimizing energy consumption during artificial ground freezing (AGF) processes.

1. Introduction

As a national central city and the core of the Central Plains urban cluster, Zhengzhou’s overall urban scale and population continue to expand, leading to increasing traffic pressure. Vigorous development of underground transportation can effectively divert surface traffic flow, serving as a vital supplement to urban transportation. The construction of underground transportation systems can also guide the rational distribution of urban populations and industries toward underground spaces and surrounding areas, optimize the city’s spatial structure, and promote balanced urban development [1]. The subway system, as the backbone of urban underground transportation, relies on the effective operation of a series of key auxiliary structures for its own safety and reliability. Among these, the cross passages connecting adjacent tunnel lines are one such key structure. As an intermediate passage connecting two adjacent subway tunnels, the cross passage not only serves as an escape route during emergencies but also plays a vital role in maintaining subway support structures and drainage systems. This study selects the No. 2 cross passage of Zhengzhou Metro Line 8 as a case for in-depth analysis. The connecting passage is buried at a depth of 22.656 m and is located in a sand layer with high water content, which poses significant challenges to conventional construction methods. In response to this water-rich sand layer, the artificial freezing method has become the optimal solution for the construction of this project due to its high safety and good waterproof performance [2,3].

Currently, numerous domestic scholars have conducted in-depth research on the application of frozen ground technology in cross-tunnel engineering. The freezing time and thickness of the frozen soil curtain serve as key indicators directly reflecting the effectiveness of frozen ground. Through continuous computational analysis of a model, Li et al. [4] studied the effects of eight factors on freezing time and determined that seepage velocity and pipe spacing are the most important factors affecting the freezing time of frozen soil curtains. Consequently, they established a new comprehensive model for predicting the freezing time of frozen soil curtains. In the calculation of the frozen soil curtain thickness, Hu et al. [5] established a method for determining the thickness of the frozen soil curtain with incomplete radial unloading at the inner edge. Semin, M. [6] believes that past calculations for the frozen soil curtain were typically performed under isotropic assumptions, failing to account for the non-uniform strength of frozen soil. Therefore, under the condition that the radial coordinate exhibits a piecewise linear cohesion function, a formula for calculating the thickness of the frozen soil curtain is proposed. Meanwhile, many studies have focused on the mechanical properties of frozen soil itself. Joudieh, Z et al. [7], Zhai et al. [8] and Liu et al. [9] investigated the effects of freeze–thaw cycles on soil properties during artificial soil freezing. Additionally, some researchers conducted geotechnical tests on undisturbed soil samples in the laboratory to obtain soil physical parameters, followed by retesting of the frozen soil. Chen et al. [10] found that after freezing, the overall unconfined compressive strength and flexural strength of sandy silt layers continued to increase, while the Poisson’s ratio continued to decrease.

At present, some scholars use numerical simulation software to model the actual research, analyze the temperature field, stress field, displacement field, and even multi-field coupling in the process of artificial freezing, and judge the formation of the frozen soil curtain. Through the comparison between the measured data and the simulated values, the general laws of water, heat, and force are analyzed [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Zou et al. [20] established one-dimensional distribution curves of the temperature field during the freezing process and the relationship between soil temperature and time. Subsequent laboratory studies on local Hangzhou silt loam revealed variations in the physical state at the freezing edge, indicating that a single temperature indicator cannot reliably determine whether the soil is in a frozen or thawed state. In the process of freezing, the mutual transformation of water and ice can cause serious frost heave and thaw settlement. Therefore, many scholars have studied the relationship between temperature, frost heave, and thaw settlement. Ma et al. [21] analyzed soil heat transfer and deformation by monitoring soil temperature and displacement. Gowthaman, S. et al. [22] used the empirical formula to calculate the deformation of frost heave and thaw settlement, and it was very consistent with the measured deformation. Li et al. [23] established the coupled thermo-mechanical model of frost heave by considering the orthogonal variability, which provides a scheme for deformation control in a complex environment. In order to study the change in frozen soil curtain thickness and average temperature in the process of intermittent freezing, Zhang et al. [24] proposed a method of double-loop liquid supply and specific control of brine temperature to suppress the occurrence of frost heave and thaw settlement.

In aquifer-active strata, seepage poses a significant challenge to the application of freezing technology. In response, researchers have developed targeted models and methodologies to address this issue. Nikolaev, P. et al. [25] investigated the development trends of the frozen soil curtain under high-velocity seepage conditions and established reliable models to predict the formation of the frozen soil curtain. Marwan, A. et al. [26] proposed a model under seepage conditions to reduce freezing time and energy costs by identifying the optimal positioning of frozen pipes. In addition, more advanced constitutive models have been developed to enhance predictive accuracy. Schindler, U. et al. [27] developed the EVPFROZEN model to predict the stability and applicability of geotechnical structures composed of frozen granular soil. By comparing the simulation results of the EVPFROZEN model with a simplified elastic model against measured data, they found that the EVPFROZEN model better predicts the load conditions within the frozen zone.

However, for the specific geological conditions of water-rich sand layers, in-depth research is still needed to accurately predict the temperature field evolution patterns beneath this unique soil layer, estimate the thickness of the frozen soil curtain, and develop efficient freezing strategies. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by abandoning purely empirical methods with low prediction accuracy. Instead, it adopts the advanced “monitoring data-driven simulation” approach, combining field measurement data with COMSOL hydrothermal coupling simulations. This research addresses these challenges by developing optimized freezing plans that reduce energy consumption without compromising safety, contributing to greener and more resource-efficient urban infrastructure development.

2. Case Studies and Research Methods

2.1. Case Study

The tunnel construction for the Zhengzhou Metro Line 8 Phase I project between Nan Liu Village Station and Wulongkou West Station employs a double-line shield tunneling technique, with a designed length of 2089.956 m for the left line and 2093.830 m for the right line. There are a total of three cross passages within the entire section, with the No. 2 cross passage also serving as a drainage pump room. During the construction process, the dynamic support principle of simultaneous excavation and support is applied. The first layer of support consists of a steel grid support and a sprayed concrete structure with a strength grade of C25 (the standard cube compressive strength value is 25 MPa), while the secondary lining structure is made of cast-in-place reinforced concrete.

The measured groundwater seepage velocity is relatively slow, allowing it to be considered negligible, with the groundwater level buried between −9.5 m and −11.5 m, all above the crown of the cross passage. To ensure construction safety, a proactive geological forecasting system is used to monitor the site water level in real time. For better drainage effectiveness, the waterproofing system employs a composite structure, laying an isolation layer made of geotextile and ECB waterproof boards between the temporary support layer and the permanent structural layer. The depth of the No. 2 cross passage, which also serves as a pump room, is 22.656 m, and its foundation engineering utilizes a drainage design with dual pipelines that effectively enhance the underground structure’s impermeability and drainage capacity.

2.2. Freeze Construction Processes and Parameter Design

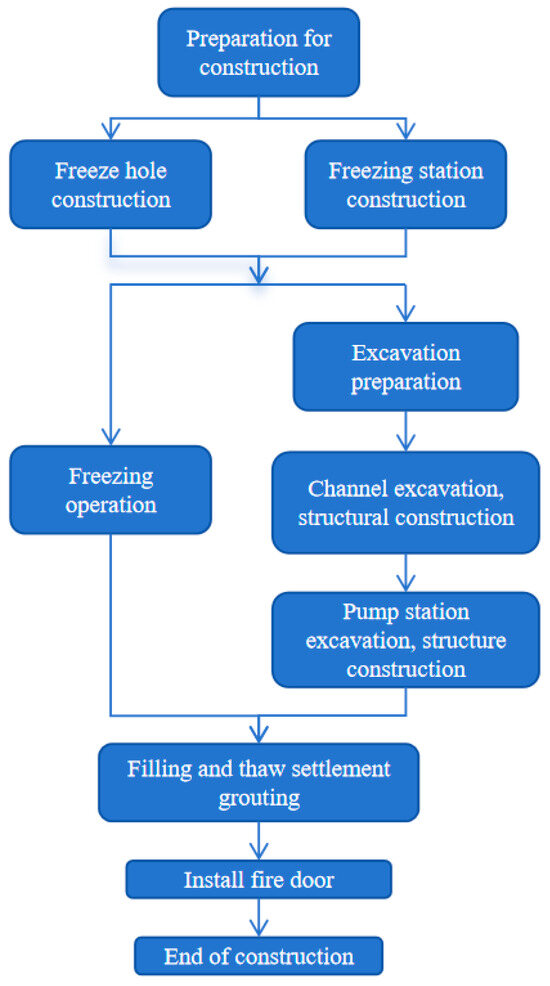

When the cross passage is constructed using the freezing method, it mainly includes the following stages: drilling operations for freezing holes, operation of the artificial freezing system in the strata, excavation of the passage, and construction of the structure. Once the main structure is completed and its strength meets the specified standards, backfilling and grouting work must be carried out promptly. The specific construction process can be referenced in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Construction flow chart of freezing method.

2.3. Frozen Soil Curtain Design

Based on the preliminary survey and on-site sampling data of the project, combined with the frozen soil strength test results under different temperature conditions, a detailed analysis and verification of the frozen soil strength and bearing capacity were conducted. Based on the experimental data and bearing capacity requirements, this study determined that the design thickness of the frozen soil curtain for the No. 2 cross passage is 2.1 m, and it was proposed that the average temperature of the frozen soil curtain should be maintained below −10 °C to ensure the stability of the soil and the safety of the structure during the freezing process. This design was optimized based on the analysis of on-site frozen soil strength and bearing capacity, fully considering the nonlinear characteristics of frozen soil strength with temperature changes and its impact on the thickness of the frozen soil curtain and overall stability, thereby ensuring the effectiveness of the frozen soil curtain and the safety of the construction project.

2.4. Freeze Hole Layout

Serving a dual purpose as both a pump room and a cross passage, the No. 2 structure adopts a bilateral tunnel arrangement for simultaneous drilling, with 78 freezing holes strategically distributed across the up-line and down-line tunnels. Specifically, 57 holes are positioned along the left tunnel and 21 along the right, resulting in a total drilling length of approximately 660.46 m. Moreover, four additional rows of freezing pipes are installed in the upper section of the adjacent tunnel to establish an auxiliary thermal insulation zone aimed at minimizing heat dissipation.

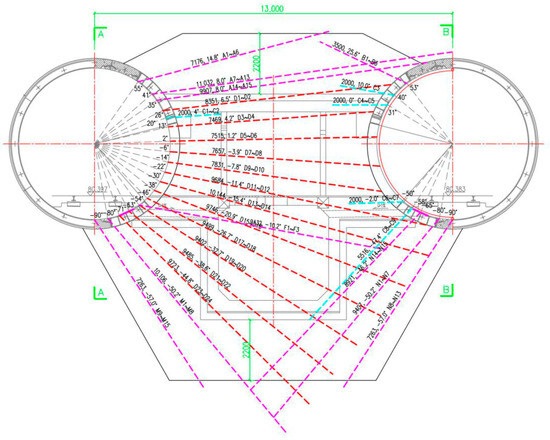

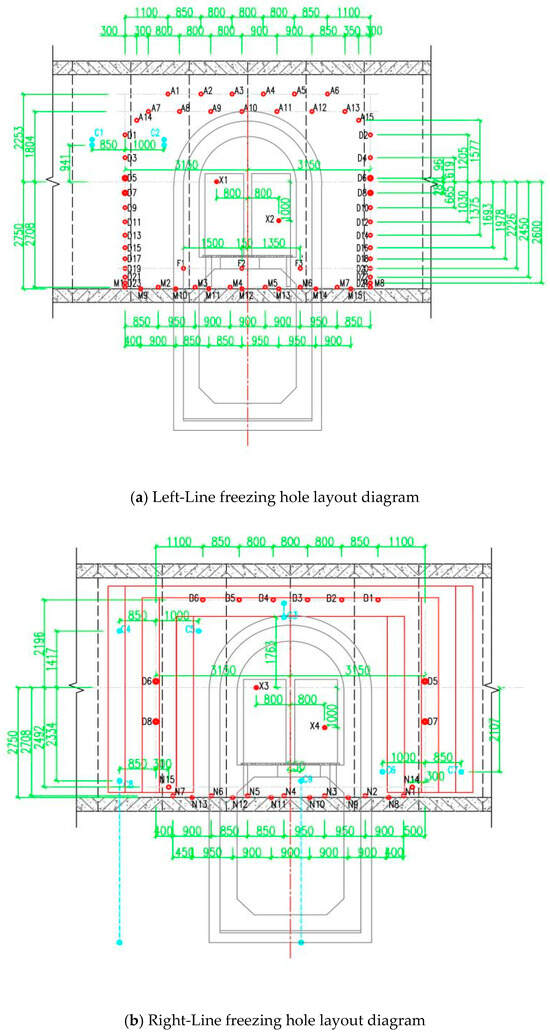

The determination of the layout position of the freezing pipes is based on the experience from similar studies and relevant recommendations from industry standards [28,29], combined with the requirements of a 50-day freezing cycle for this project, resulting in a systematic optimization design. When laying out the freezing pipes, careful consideration was given to the freezing rate, freezing depth, and the uniformity of the cooling effect to ensure the effectiveness and stability of the frozen wall. By reasonably configuring the position and spacing of the freezing pipes, an efficient and reliable frozen soil curtain is ensured within the specified freezing cycle. This design not only meets the time requirements of the project but also fully considers the technical feasibility and economic viability during the construction process, ensuring that the frozen soil curtain meets the thickness requirements while providing a solid foundation for subsequent construction. The layout perspective and opening position diagrams of the freezing holes for the No. 2 cross passage and pump room are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Perspective view of the layout of the freezing hole of the No. 2 cross passage and pump room.

Figure 3.

Location diagram of the freezing hole of the No. 2 cross passage and pump room.

2.5. Temperature Measurement Port Layout

For the temperature collection system of the No. 2 cross passage and pump room, temperature monitoring is achieved by arranging temperature measurement holes. Each temperature measurement hole is equipped with at least 3 temperature monitoring points. For the special positions C8 and C9, a deep hole temperature measurement design with a depth of 5.5 m is used, while a standard hole depth temperature measurement design with a depth of 2.0 m is used for other temperature measurement holes. The temperature measurement hole layout diagrams are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Three-dimensional temperature data are acquired to capture the evolution of the thermal field and to detect abnormal temperature gradients at an early stage, thereby enhancing construction safety.

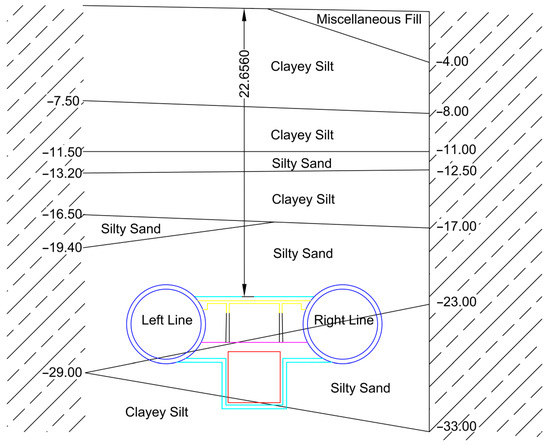

2.6. Geological Conditions of the Case Study Site

Figure 4 presents the site-specific geological profile derived from geotechnical investigation.

Figure 4.

Geological Cross-Section of the Cross Passage and Pump Room.

2.7. Pressure Relief Hole Arrangement

In the frozen soil curtain closed section, a symmetrical pressure relief design scheme was adopted. By installing pressure gauges at the pressure relief holes, real-time monitoring of the internal pressure of the frozen wall can be achieved, thereby forming a pressure gradient analysis system. Additionally, the stability of the frozen curtain structure can be assessed through pressure increases and releases. The locations of pressure relief holes X1 to X4 are shown in Figure 3.

2.8. Freezing Construction Technical Parameters

The design thickness of the frozen soil curtain for the frozen contact channel is 2.1 m. Other main parameters for freezing can be referenced in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main parameters of the freeze.

3. Establishment of Three-Dimensional Numerical Simulation

This model employs COMSOL finite element software to perform water–heat coupling calculations for No. 2 cross passage based on the actual on-site cooling scheme, temperature variations at each observation point were computed. The temperature contour plots reveal the temperature field changes across the entire area and the formation process of the frozen soil curtain.

3.1. Basic Assumptions and Theories

According to the fundamental principles of heat conduction, frozen soil gradually forms during the freezing process through heat exchange with the low-temperature refrigerant. Simultaneously, water infiltrating within the soil freezes, constituting a heat transfer problem involving phase change. Furthermore, the heat transfer process in porous media involves the combined effects of multiple mechanisms, including conduction and convection. Neglecting seepage, the mathematical model representing the transient temperature distribution is formulated as follows [30]:

In the equation: s represents solid, f represents liquid; denotes the Hamilton operator; T is temperature in Kelvin; denotes specific heat capacity in J/kg·K; represents density in kg/m3; denotes thermal conductivity in W/(m·K); and represents the sum of other heat sources.

3.2. Establishment of Geometric Models

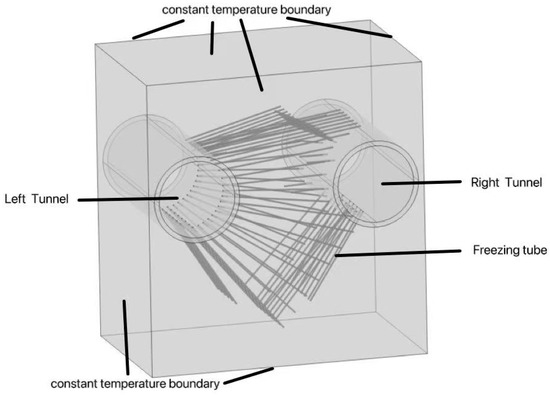

Using the built-in model module of COMSOL for modeling, a transient study of the water–heat coupling in the entire area is conducted. The dimensions of the entire model are length × width × height = 20 m × 13 m × 21 m, consisting of three main components: left and right tunnels, 74 freezing pipes, and the soil. The specific shape of the model and the model’s boundary conditions are depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the 3D model and its boundary conditions.

3.3. Model Parameter Selection

(1) Conducted geotechnical tests on the excavation layer soil during the research’s early stages. Standard testing methods were employed to determine the target soil and liquid’s thermophysical parameters, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Soil material parameters.

Table 3.

Liquid material parameters.

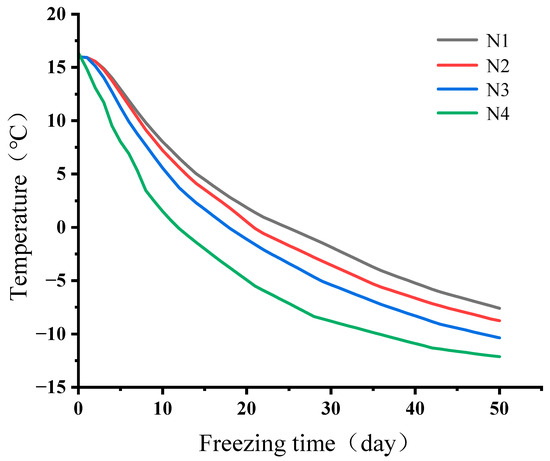

(2) For grid partitioning, four methods—N1, N2, N3 and N4 (representing four different grid precisions: more refined, refined, standard, and coarse). Through numerical simulation calculations, the temperatures at the C8-2 (Temperature measurement hole C8, depth 1.2 m) measurement point after 50 days of freezing were compared. The temperature variations are shown in Figure 6. The temperatures recorded after 50 days of freezing under the four scenarios were −7.59 °C, −8.77 °C, −10.37 °C and −12.13 °C, respectively. The temperature variation between N2 and N1 was 13.4%, while the variation between N2 and N3 was 18.2%. This demonstrates that when the grid refinement exceeds N2, the model’s calculations become independent of the grid. Therefore, all subsequent computations were based on the N2.

Figure 6.

Temperature variation in C8-2 under different mesh partitions.

(3) To accurately simulate the actual freezing process, the model’s cooling boundary conditions were established based on field monitoring data. During the 50-day active freezing period of the simulation, 50 analysis steps were set (each step representing one day).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Evolution Patterns of Temperature Fields During Freezing Processes: Field Monitoring and Simulation Comparison

Employing the currently more precise “combination of actual measurement and simulation” approach, the method utilizes actual measurement data to obtain the real-time temperature and pressure variation trends at the site. The results simulated by COMSOL are then compared with the actual measurement data to validate the rationality of the model established.

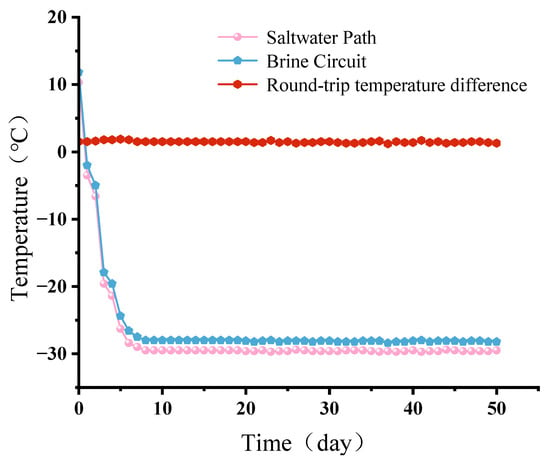

4.1.1. Analysis of Actual Brine Temperature Data

Currently, the commonly used refrigerants in the freezing method are primarily low-temperature brine and liquid nitrogen. Considering the economic benefits of the project, low-temperature brine is selected as the refrigerant. The essence of the freezing method is to circulate low-temperature brine through the freezing pipes. Due to the higher temperature of the soil, some heat is transferred to the low-temperature brine, causing a continuous reduction in heat in the soil and gradually forming a frozen soil curtain [31,32]. After the initial activation of the freezing system, there is a significant temperature difference between the soil and the low-temperature brine inside the freezing pipes. According to the analysis based on Newton’s law of cooling and Fourier’s law of heat conduction, during this stage, the rate of heat conduction in the soil reaches its peak, exhibiting a rapid cooling trend, while the brine circulation system shows a high heat exchange load state [33]. Throughout the entire phase change heat transfer process of the frozen soil curtain, the thermal gradient of the low-temperature brine circulation system generally exhibits a converging characteristic. Figure 7 illustrates the temperature changes in the low-temperature brine circulation system. Monitoring data indicate that on the seventh day of active freezing construction, the temperature of the refrigerant medium has stabilized at −18 °C, and it reaches the −24 °C threshold by the fifteenth day, with the temperature difference in the low-temperature brine circulation system remaining within 2 °C throughout the freezing process. This temperature control meets the thermal equilibrium requirements for safe excavation.

Figure 7.

Temperature change in the cryogenic brine circulation system.

4.1.2. Analysis of Actual Soil Temperature Measurement Data

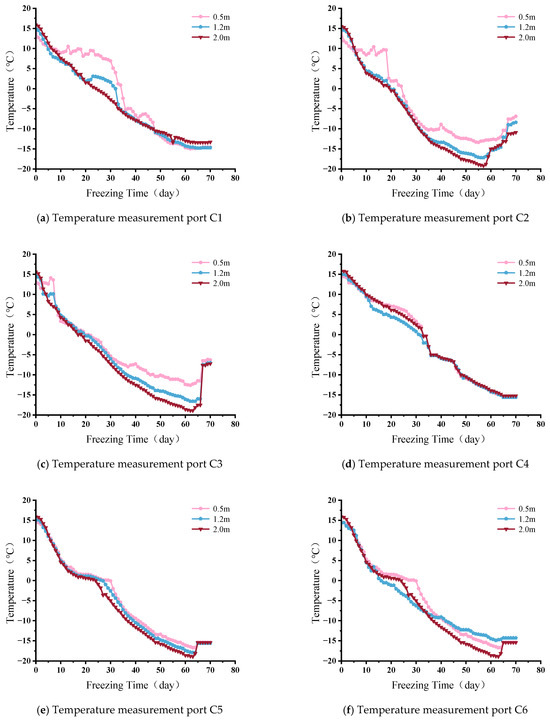

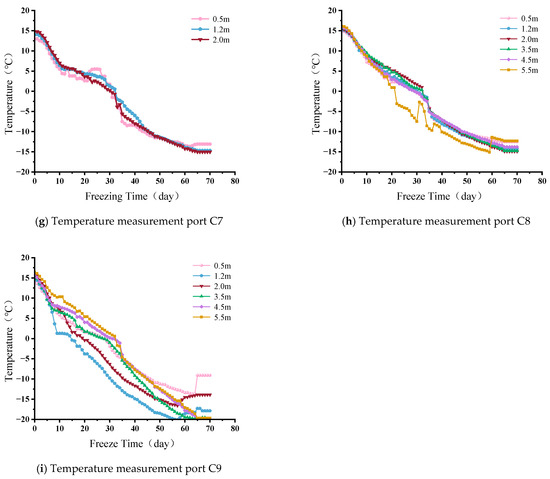

Temperature monitoring ports are arranged as shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, with two positioned on the left line and seven on the right. Each tube contains a minimum of three sensors, enabling real-time observation of frozen wall development within the soil. This configuration also supports early assessment of frost heave and thaw settlement trends, facilitating timely interventions to regulate their progression and maintain construction safety. The detailed temperature readings from the nine monitoring points are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Temperature change in C1~C9 thermometer.

According to the monitoring data from the nine temperature measurement wells shown in Figure 8, after the low-temperature brine circulation commenced, all measurement points exhibited a sustained cooling trend, ultimately reaching thermal equilibrium. Specifically, the temperature field patterns at different depth points within the same measurement well were largely consistent. During the initial freezing stage, the rate of temperature decrease accelerated significantly. As the freezing duration increased, the heat exchange efficiency decreased, and the temperature gradient exhibited dynamic convergence characteristics. Furthermore, as the frozen soil curtain continued to expand, the overall temperature within the monitoring area still showed a downward trend.

In the initial stage, the temperatures at each measurement point were approximately between 13 °C and 16 °C, with a slight increase in temperature as depth increased. Analyzing the temperature curves at different points within the same measurement well, it was found that the temperature changes at C1, C2, C3, C4, C5 and C7 followed Newton’s law of cooling and Fourier’s law of heat conduction. In the early freezing stage, the low-temperature brine in the freezing pipes continuously absorbed heat, leading to a rise in temperature. The cooling effect on the outer soil was less than that on the inner soil, resulting in a faster rate of temperature decrease at a depth of 0.5 m. However, after the freezing stabilized, the rate of temperature decrease at this depth slowed down due to its shallow burial and the rising ambient temperature during the monitoring period. Once the frozen soil curtain gradually formed, the temperature at the 0.5 m measurement point continued to decline. In contrast, the temperature data at depths of 1.2 m and 2 m were less affected by external factors, resulting in better freezing effects.

The data from measurement wells C6, C8 and C9 showed slight differences. For C6, the main reason was the dense distribution of freezing pipes at a depth of 0.5 m, which significantly improved the freezing effect. In contrast, the freezing pipes at depths of 1.2 m and 2 m were more sparse, leading to less effective freezing compared to the 0.5 m depth. For the data from measurement wells C8 and C9, the lower thermal conductivity of the peat soil compared to the silty clay and sandy soil resulted in a weaker ability to transfer heat, leading to a lower rate of temperature decrease.

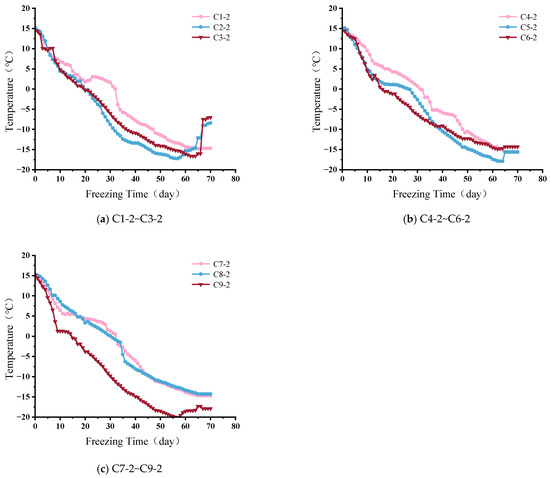

To assess the formation of the frozen soil curtain during construction, temperature data from different measurement holes buried at a depth of 2 m, which are more representative of actual conditions, were selected for plotting. The overall variation curve is shown in Figure 9. The temperature change at points C2-3 is relatively rapid. As seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the freezing pipes near this measurement hole are quite dense and located on the inner side of the frozen soil curtain, resulting in the best freezing effect in this area, with the fastest temperature drop and the lowest temperature recorded. Overall analysis indicates that since the range of soil encapsulated by the frozen soil curtain is limited, the temperatures at C2, C3, C5, C6 and C9 drop relatively quickly, indicating a better freezing effect. In contrast, C1, C4, C7 and C8 are located on the outer side of the frozen soil curtain, where the cooling provided by the freezing pipes is relatively less compared to the larger volume of soil on the outside that needs to absorb cold, resulting in a slower temperature drop.

Figure 9.

Temperature variation curve at a depth of 2 m at each temperature measuring hole.

After 55 days of freezing, an upward trend in temperature was observed at C2, C3, C5 and C9. This was due to subsequent excavation work around day 50, which increased the exposed surface area, allowing the soil outside the frozen soil curtain to absorb more heat, leading to a temporary rise in temperature. However, the interior of the frozen soil curtain is a closed space, making it difficult for heat from the exposed surface to transfer to the inside, so the temperature at the measurement points within the frozen soil curtain did not show a significant upward trend. Overall data observation revealed that the temperature of the soil during excavation was below −10 °C, meeting the requirements of the construction design.

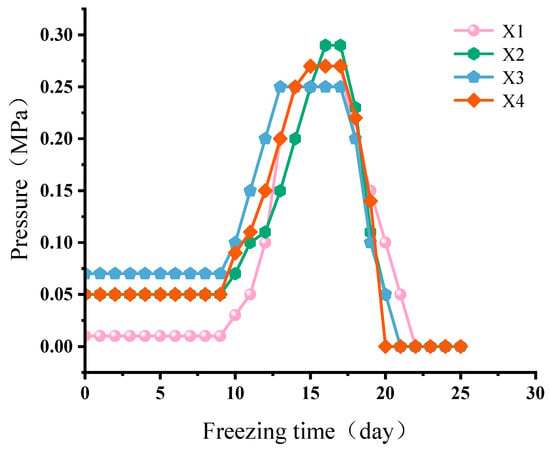

4.1.3. Analysis of Actual Pressure Data from Pressure Relief Holes

Four pressure relief holes were installed in this research. The location diagram of pressure relief holes X1–X4 is shown in Figure 3. Throughout the freezing process, as temperatures continuously decrease, the pore water pressure within the soil undergoes constant changes. The measured pressure data from these relief holes accurately reflect the formation and development of the frozen soil curtain, enabling assessment of whether the frozen soil curtain meets subsequent construction requirements. Monitoring for abnormal data can also facilitate early accident prevention, thereby reducing research risks. The pressure fluctuations at the four relief holes are illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Trend of pressure relief hole pressure.

The data in Figure 10 indicate that during the initial freezing stage, the pressure at each vent hole remains low. However, as freezing time increases, the temperature of the surrounding soil gradually decreases, causing the temperature of pore water within the soil to continuously drop, transforming the soil into frozen ground. As the frozen ground curtain expanded to close the loop, the soil surrounding the cross passage formed a sealed frozen ground mass. Pressure within the soil could not be released, causing the pressure values measured in the pressure relief holes to begin increasing. After the 8th day of freezing, the pressure values measured across all pressure relief holes started to rise continuously. Around the 15th day of freezing, the overall pressure reached its maximum value, with pressure values at relief holes X1–X4 recorded as 0.27 MPa, 0.29 MPa, 0.25 MPa and 0.27 MPa, respectively, maintaining stable levels. This indicates satisfactory formation of the frozen curtain. Pressure relief commenced after day 17, during which pressure values consistently declined in a stable trend, meeting acceptance criteria and permitting subsequent excavation work.

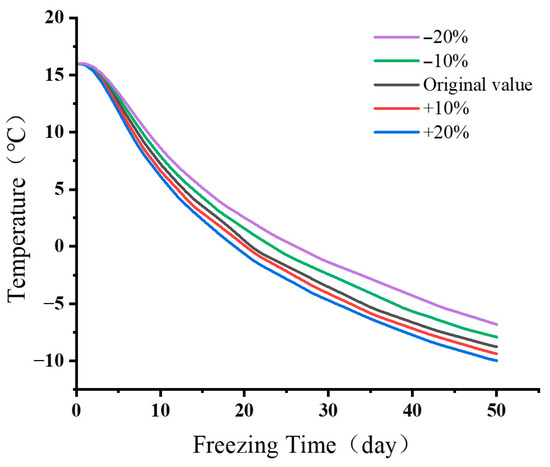

4.1.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Soil Parameters

To verify the rationality of the soil parameter settings, an uncertainty analysis of the model was conducted. Extensive research indicates that among the physical parameters of soil, the thermal conductivity has the greatest impact on the temperature field. Therefore, an uncertainty analysis was performed specifically on the thermal conductivity of the soil [4,34]. Simulations were conducted using thermal conductivities of ±20%, ±10%, and the original value.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that the C8 temperature borehole lies on the outer side of the freeze curtain. Being farther from the freeze pipes than interior points, peripheral locations like C8 have temperature evolution that is more strongly controlled by soil thermophysical properties. By comparing the temperature data at point C8-2, it was found that the cooling patterns under different thermal conductivities exhibited a consistent trend. The rate of temperature decrease is directly proportional to the thermal conductivity, meaning that the higher the soil thermal conductivity, the faster the cooling rate. When the thermal conductivity increases by 20%, the temperature drops by 1.21 °C after fifty days of freezing. Conversely, when the thermal conductivity decreases by 20%, the temperature rises by 1.96 °C after the same freezing period. Additionally, under the same freezing time, the temperature changes caused by adjacent thermal conductivities are all less than 1.4 °C, indicating that the model parameter selection is reasonable. The temperature changes under different thermal conductivities are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Temperature variations at C8-2 under different thermal conductivities.

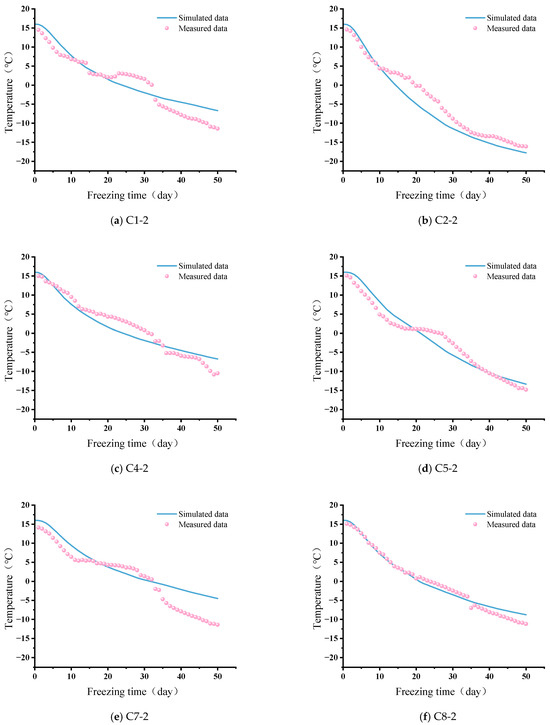

4.1.5. Comparison of Simulation Results with Actual Data

In the 3D model, measurement point No. 2 at each temperature monitoring location in the actual project was selected. Temperature variations during the simulation process were extracted and compared with the actual measured data from measurement point No. 2 at locations C1, C2, C4, C5, C7, and C8, as shown in Figure 12. The simulated temperatures at each point exhibited the same variation pattern as the actual measured temperatures: a rapid decrease rate during the initial freezing stage, followed by a gradual slowdown in the decrease rate over time and a tendency toward stabilization. Although some simulation data deviated slightly from actual measurements at individual points, the overall results closely approximated reality. At the same time, the formation speed of the frozen soil curtain in the simulation results is consistent with the results shown by the measured pressure. In the simulation, the frozen soil curtain completes its loop after 13 days of freezing, while the measured pressure rises rapidly between the 8th and 15th days of freezing. The data indicate that the measured data and simulation results are in good agreement, confirming the validity of the model establishment, parameter selection, and boundary condition settings.

Figure 12.

Comparison of simulated and actual temperature data at each measurement point.

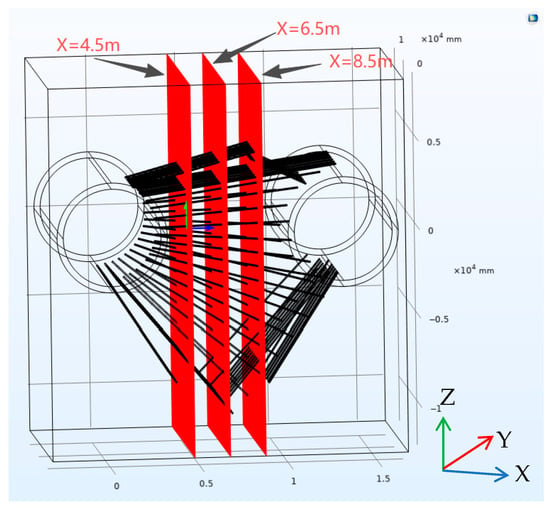

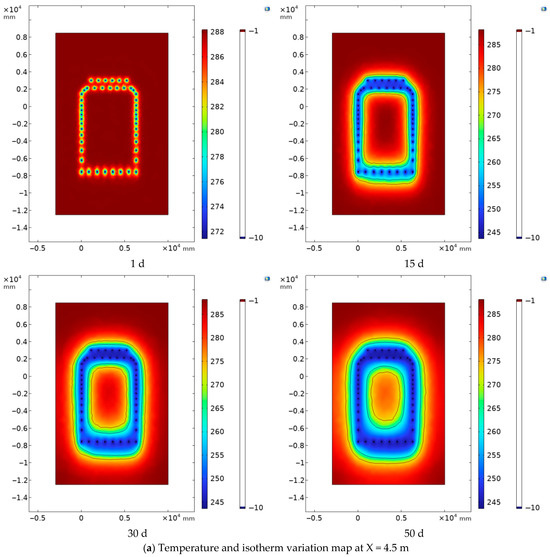

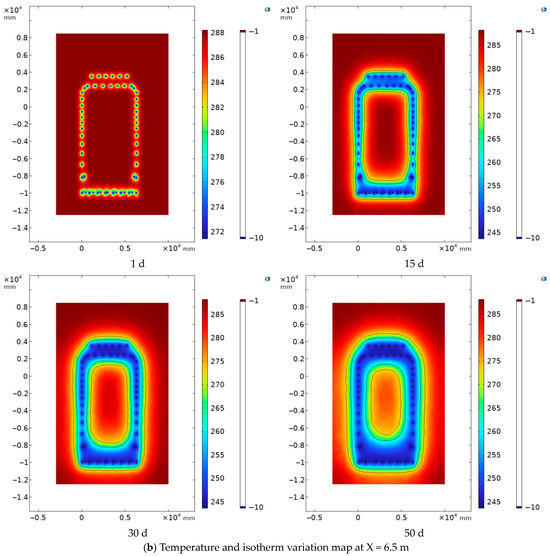

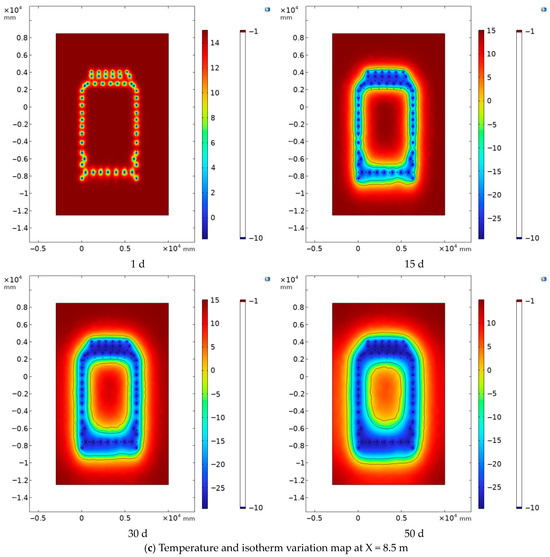

4.1.6. Analysis of Simulation Results

In the model, the YOZ of the vertical freezing pipe was selected as the working plane (Figure 13). Three cross-sections were chosen—X = 4.5 m (near the left-line tunnel), X = 6.5 m (model center), and X = 8.5 m (near the right-line tunnel)—to study temperature variation patterns and isothermal line distributions across these sections (Figure 14). Analysis of the temperature variation contour maps reveals identical development patterns across all three sections. Following the initiation of freezing, the soil layer adjacent to the outer wall of the freezing pipe first cools. This triggers a phenomenon where the frozen zone continuously expands outward from the freezing pipe as its center. As cold energy is continuously introduced, the cylindrical frozen zones gradually intersect, forming a relatively stable frozen soil curtain. Subsequently, this frozen soil curtain continues to absorb cold energy, leading to its ongoing expansion. The overall shape of the frozen soil curtain reveals that the distribution density of the freezing tubes on the left and right sides is lower than that on the top and bottom. Consequently, the amount of cold energy transferred through the freezing tubes on the left and right sides is relatively lower compared to the top and bottom. Therefore, the frozen soil curtain at each cross-section exhibits a shape that is wider at the top and bottom and narrower on the left and right sides [26].

Figure 13.

Schematic Diagram of Working Section Setup.

Figure 14.

Temperature and isotherm variation cloud diagram across cross-sections.

Following the validation of the numerical model using field data, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3 focus on optimizing the cooling strategy for practical engineering applications.

4.2. Frozen Soil Curtain Formation Performance Evaluation and Cooling Scheme Optimization Analysis

This analysis focuses on the cross-section at X = 6.5 m, which possesses spatial symmetry and is representative, allowing for a balanced reflection of the effects of the freezing pipes on both sides of the tunnel. This reduces the unilateral boundary effects and more accurately demonstrates the general shape and core characteristics of the frozen curtain in the cross passage.

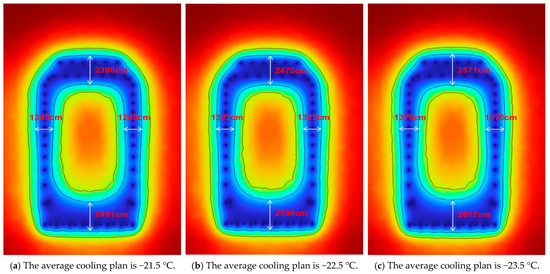

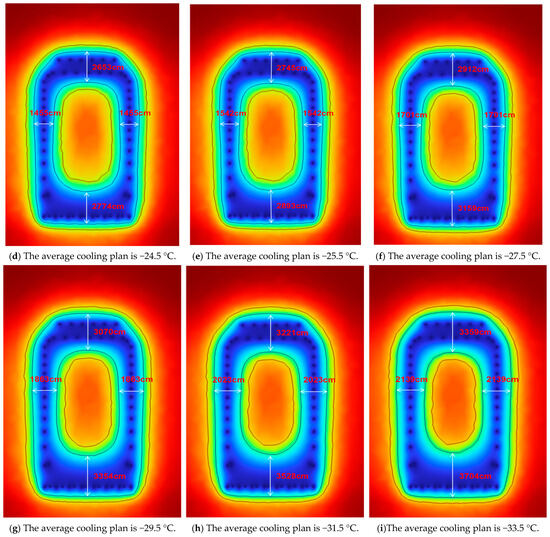

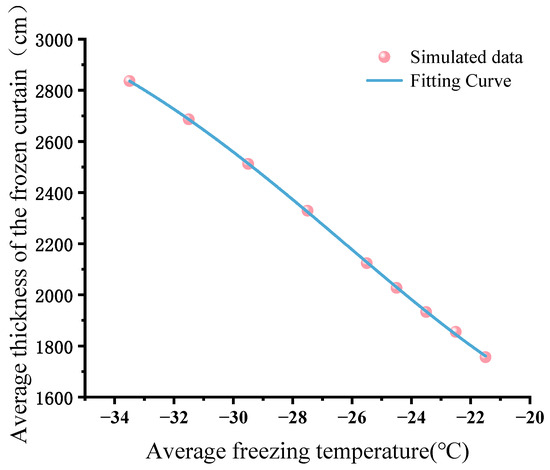

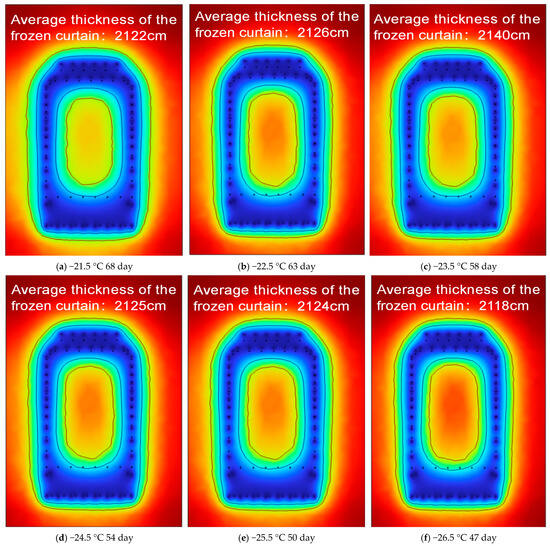

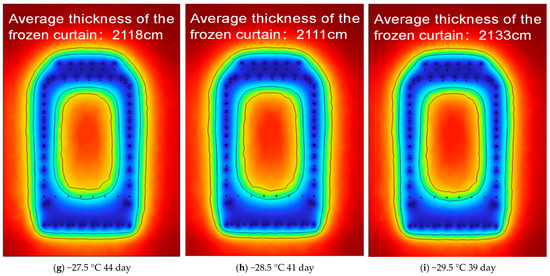

The temperature contour map at the X = 6.5 m cross-section reveals that the frozen soil curtain thickness exceeds its design value after freezing completion. To investigate the impact of cooling schedules on the final frozen soil curtain formation and the closure time of the frozen soil curtain, multiple simulation experiments were conducted. These experiments used the actual cooling schedule as a baseline while adjusting each day’s schedule (simultaneously raising or lowering the temperature by the same amount). The resulting final frozen soil curtain configuration is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Final formation of the frozen soil curtain under different cooling plans.

The data in Table 4 was obtained through weighted calculations. As the cooling temperature continues to decrease, the overall thickness of the frozen soil curtain increases, showing significant unevenness in both the vertical and horizontal directions. This unevenness may alleviate somewhat as the overall temperature decreases, but it still maintains a relatively high ratio. The main reason for this situation is the layout of the freezing pipes; double rows of freezing pipes are arranged on the upper and lower sides, while only a single row is arranged on the left and right sides. As a result, the frozen area on the upper and lower sides is larger. However, as the range of the frozen soil curtain on the upper and lower sides continues to expand, more cooling capacity is needed to maintain the existing frozen area, causing the expansion rate of the frozen area on the upper and lower sides to slow down compared to the left and right sides, leading to a certain degree of alleviation of this unevenness.

Table 4.

Frozen soil curtain conditions under different cooling plans.

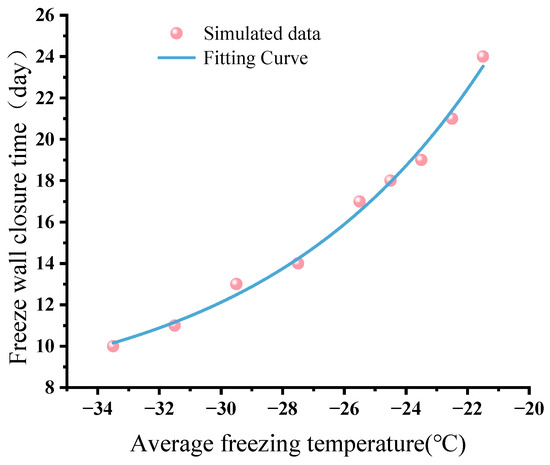

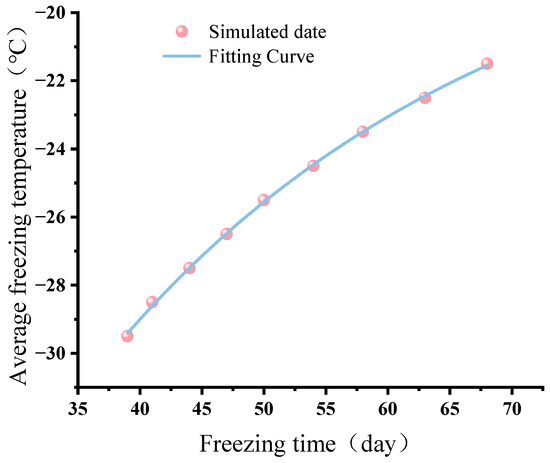

Figure 16 and Figure 17 illustrate the variations in average thickness and cycle time of the frozen soil curtain under different cooling schedules. The initial scatter plots reveal that when temperatures fall below the actual cooling plan, the rate of decrease in frozen soil curtain closure time slows. Conversely, when temperatures exceed the actual cooling plan, the frozen soil curtain closure time progressively extends. This occurs because the actual cooling plan provides sufficient refrigerant cooling capacity to support complete frozen soil curtain formation. Consequently, further reductions in the overall cooling plan yield diminishing effects on frozen soil curtain closure time. Conversely, as the overall cooling plan temperature increases, less cooling capacity accumulates in a short time, prolonging the time required to form a complete frozen soil curtain [35]. By fitting data from various scenarios, the functional relationship between the average cooling plan temperature and the frozen soil curtain closure time is obtained as:

Figure 16.

Variation in frozen soil curtain circumference time under different cooling schedules.

Figure 17.

Changes in average thickness of frozen soil curtain of tunnel under different cooling plans.

In the formula: is the frozen soil curtain circulation time; is the average temperature of the cooling schedule; = 317.94; = 6.97; = −7.28.

By observing the actual cooling plan, the average thickness of the frozen soil curtain areas far exceeding the design requirement of 2.1 m. To avoid excessive energy loss during the freezing process, simulations were conducted on nine different cooling plans to analyze variations in the average thickness of the frozen soil curtain. Through functional calculations, an economically viable cooling plan that meets the research’s design requirements can be identified.

The correlation between deviations from the optimal cooling scheme and the resulting average frozen wall thickness on both sides of the tunnel is described as follows:

In the formula: is the average thickness of the frozen soil curtain; is the average temperature in the cooling plan; = 43,308.52; = −14.85; = 22.62; = −52,158.22.

The primary objective of this optimization analysis is to determine an “economical cooling gap” without compromising safety or the project schedule. Given a strict 50-day construction timeline and a design requirement of a 2.1 m thick frozen soil curtain, the optimal freezing scheme was determined within these constraints. The analysis shows that raising the average freezing temperature to −25.5 °C still allows the frozen soil curtain to reach its design thickness within the required 50-day timeframe. This is 4 °C higher than the −29.5 °C freezing temperature used in the baseline scheme.

From a long-term stability and safety perspective, the optimized freezing scheme at −25.5 °C yields a frozen soil curtain thickness of 2.124 m, slightly above the 2.1 m design target, thereby providing an inherent safety margin. Furthermore, the frozen soil curtain’s core temperature remains well below the design average of −10 °C. This ensures that the frozen soil retains sufficient mechanical strength.

4.3. Optimization of Cost-Effective Freezing Plans Under Different Construction Durations

To reconcile project timeline requirements with energy-efficient performance in artificial ground freezing (AGF) applications, this study conducted a series of parameterized numerical simulations. These simulations examined the thermal evolution of the frozen curtain under varying durations of cooling and different refrigerant temperature settings. By identifying the minimum thermal input necessary to achieve the target frozen wall thickness within each designated construction period, the optimal freezing strategy for each scenario was derived, as illustrated in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Optimal Frozen Curtain Formation Across Cooling Plans.

To further quantify the relationship between construction time and the corresponding optimal thermal input, a fitting curve was developed based on simulation outcomes. As shown in Figure 19. This curve serves as a practical reference for selecting energy-efficient freezing strategies in future AGF projects.

Figure 19.

Optimal freezing schemes under various freezing plans.

Based on the fitted curve, we derived an empirical expression to represent the relationship between Optimal freezing schemes and various freezing plans, as follows:

In the formula: is the Average freezing temperature; is a range of freezing periods; = −45.19; = −16.38; = 31.37.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the challenge of predicting and controlling water–heat evolution processes during artificial stratum freezing in water-rich sand layers by developing an analytical optimization framework integrating field monitoring with numerical simulation. Through systematic investigation of the Zhengzhou Metro cross passage case, the following key conclusions and contributions were obtained:

- (1)

- It reveals the heterogeneous control mechanism of the temperature field evolution in the water-rich sand layer AGF, deepening theoretical understanding.

This study not only validated the formation process of the frozen soil curtain but, more importantly, quantitatively revealed that the spatiotemporal evolution of the temperature field in water-rich sand layers—a specific medium—is particularly strongly controlled by the layout of the freezing pipes and the heterogeneity of the formation. The study clarifies the differential cooling efficiency patterns on the inner and outer sides of the frozen soil curtain. It further reveals that for poorly conductive interlayers (e.g., C8, C9), the conventional uniformity assumption introduces significant prediction errors. These findings deepen the understanding of AGF heat transfer mechanisms within heterogeneous aquifer formations.

- (2)

- A novel approach for optimizing cooling solutions based on quantitative response relationships has been proposed, offering direct contributions to enhancing project economic viability.

The core practical contribution of this study lies in moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches by establishing a quantitative predictive model that links cooling strategies with freezing efficiency—specifically closure time and frozen wall thickness. For the first time, an “economic cooling window” was clearly defined within a fixed construction period of 50 days. Within this window, increasing the average cooling temperature by up to 4 °C still ensures safety thresholds are met while significantly reducing energy consumption. To accommodate varying construction timelines, multiple simulations were carried out, and an empirical formula was derived. This enables the development of schedule-adaptive and energy-efficient freezing schemes tailored to different project durations, ensuring compliance with both structural and thermal design criteria.

- (3)

- The reliability and methodological value of the water–heat coupling simulation framework has been verified and established.

This study successfully validated the effectiveness and reliability of the COMSOL water–heat coupling model in simulating the freezing process of water-saturated sand layers by using detailed field monitoring data as the benchmark for model calibration and validation. This rigorously validated model and its parameter set can serve as a reliable reference standard for future related simulation studies. The “data-driven simulation” methodology advocated herein provides a replicable paradigm for addressing similar complex problems in the field of geotechnical engineering.

- (4)

- Research Limitations and Future Prospects

This study primarily focuses on water–heat coupling processes without explicitly considering groundwater seepage effects or soil salinity content, nor mechanical phenomena such as frost heave and thaw settlement. Furthermore, the model’s simplified treatment of soil heterogeneity constitutes one of the primary sources of prediction errors. Subsequent work will aim to develop a comprehensive coupled seepage-heat-mechanics-salinity model and apply the optimization framework established in this study to a broader range of geological conditions to further validate and extend its universality.

Author Contributions

J.H.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing—review & editing. H.D.: Writing—original draft, Formal analysis, Data Curation. Y.N.: Project administration, Writing—review & editing. J.S.: Methodology, Investigation. Z.S.: Investigation, Resources. D.Z.: Data Curation, Investigation. Y.Y.: Validation, Methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the High Technology Direction Project of the Key Research and Development Science and Technology of Hainan Province, China (Grant No. ZDYF2024GXJS001); and the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation Enterprise Talent Project (Grant No. 525QY918).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ying Nie was employed by the company “Kunming Prospecting Design Institute of China Nonferrous Metals Industry Co., Ltd.”. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lu, J. Advancing the High-Quality Development of Zhengzhou’s Urban Transportation. Urban Transp. 2024, 22, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Cai, Y.; Wu, D.; Guo, C.; Zhao, W.; Tang, K.; Liu, Y. Application of Artificial Freezing Method in Deformation Control of Subway Tunnel. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 3251318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Hou, C.; Li, K.; Liu, B.; Sang, H. Evolution of temperature field and frozen wall in sandy cobble stratum using LN2 freezing method. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 185, 116334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, S.; Li, X.K.; Yue, Z.R. Evolution law and calculation model of closure time in artificial ground freezing. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 157, 106358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Yang, Z.; Han, T.; Yang, W. Calculation Method of the Design Thickness of a Frozen Wall with Its Inner Edge Radially Incompletely Unloaded. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semin, M. Calculation of frozen wall thickness considering the non-uniform distribution of the strength properties. In Proceedings of the 22nd Winter School on Continuous Media Mechanics (WSCMM), Perm, Russia, 22–26 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Joudieh, Z.; Cuisinier, O.; Abdallah, A.; Masrouri, F. Artificial Ground Freezing—On the Soil Deformations during Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Geotechnics 2024, 4, 718–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chang, D.; Yu, Q. Influence of freeze-thaw cycles on mechanical properties of a silty sand. Eng. Geol. 2016, 210, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Zhang, Z.; Melnikov, A.; Zhang, M.; Yang, L.; Jin, D. Experimental Study on the Effect of Freeze-Thaw Cycles on the Mineral Particle Fragmentation and Aggregation with Different Soil Types. Minerals 2021, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; You, Z.; Wang, J. Study on the displacement and stress variation of frozen curtain during excavation of subway cross passage. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 65, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Hong, R.; Xu, L.; Wang, C.; Rong, C. Frost heave and thawing settlement of the ground after using a freeze-sealing pipe-roof method in the construction of the Gongbei Tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 125, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Lu, M. Study on development characteristics of horizontal freezing temperature field in subway connecting passage. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 619, 012086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Yang, P. Ground temperature characteristics during artificial freezing around a subway cross passage. Transp. Geotech. 2019, 20, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zeng, H. Finite Element Analysis of Natural Thawing Heat Transfer of Artificial Frozen Soil in Shield-Driven Tunnelling. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 2769064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Ye, G.-L.; Li, Y.-H.; Xia, X.-H.; Wang, J.-H. In situ monitoring of frost heave pressure during cross passage construction using ground-freezing method. Can. Geotech. J. 2016, 53, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Li, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, W.; Yuan, B. Three-Dimensional Refined Numerical Modeling of Artificial Ground Freezing in Metro Cross-Passage Construction: Thermo-Mechanical Coupling Analysis and Field Validation. Buildings 2025, 15, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounsi, H.; Rouabhi, A.; Tijani, M.; Guérin, F. Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Modeling of Artificial Ground Freezing: Application in Mining Engineering. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 3889–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Rong, C.; Long, W.; Yu, S. Temporal and Spatial Evolution Laws of Freezing Temperature Field in the Inclined Shaft of Water-Rich Sand Layers. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopko, J. Coupled Heat Transfer and Groundwater Flow Models for Ground Freezing Design and Analysis in Construction. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Geotechnical Frontiers, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–15 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, B.; Hu, B.; Xia, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Q.; Kong, B.; Ma, J. Study on Temporal and Spatial Variation in Soil Temperature in Artificial Ground Freezing of Subway Cross Passage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Huang, K.; Zou, B.; Li, X. Experimental Study on Soil Temperature and Deformation during an Artificial Ground-Freezing Process Considering Interface Differences. Asce-Asme J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part A Civ. Eng. 2025, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowthaman, S.; Henry, G.; Leena, K.-T.; Carles, P.C.; Mirva, K. Frost Heave and Thaw Settlement Estimation of a Frozen Ground. In Fundamentals to Applications in Geotechnics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 891–898. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Cai, H.; Pang, C. Three-Dimensional Numerical Modeling of Freezing Construction of Underpass Tunnels Considering Orthotropic Anisotropy of Frozen Soil. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.-M.; Zhang, J.; Sun, T.; Ma, W.; Liu, Y.; Yang, N. A Case Study of Energy-Saving and Frost Heave Control Scheme in Artificial Ground Freezing Project. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 1004735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, P.; Jivkov, A.P.; Margetts, L.; Sedighi, M. Modelling artificial ground freezing subjected to high velocity seepage. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 221, 125084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwan, A.; Zhou, M.-M.; Abdelrehim, M.Z.; Meschke, G. Optimization of artificial ground freezing in tunneling in the presence of seepage flow. Comput. Geotech. 2016, 75, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, U.; Chrisopoulos, S.; Cudmani, R. Artificial ground freezing applications using an advanced elastic-viscoplastic model for frozen granular soils. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2023, 215, 103964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical Code for Underground Engineering Freezing Method; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Zhang, W. Manual of Design and Construction for Artificial Ground Freezing; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Hu, J.; Wei, K.; Guo, Y. Numerical Analysis of the Effect of Groundwater Seepage on the Active Freezing and Forced Thawing Temperature Fields of a New Tube-Screen Freezing Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, H.S.; Jaeger, J.C. Conduction of Heat in Solids, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Andersland, O.B.; Ladanyi, B. Frozen Ground Engineering, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P.; Bergman, T.L. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 7th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K. Study on the Evolution Law of the Temperature Field of Freezing Reinforcement for Shallow-Buried Mined Tunnels Under Seepage Conditions; Hainan University: Haikou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Li, K.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, D.; Wang, Z. Optimization of the Cooling Scheme of Artificial Ground Freezing Based on Finite Element Analysis: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).