Abstract

This study examines the evolving relationship between the Port of Motril and the adjacent fishing community of El Varadero. The reduction in fishing quotas and the port’s transformation into a maritime transport hub have not only reshaped the connection between the area and the port but have also contributed to the gradual decline of the local community. Through a community survey conducted among residents of the fishing neighborhood and the urban center (n = 65), we assessed community assets, psychological sense of community, and collective self-efficacy in this coastal area in southern Granada. The survey findings were supplemented with interviews with key informants from the local fishing sector (n = 5). The results indicate that residents of the fishing neighborhood perceive a higher prevalence of social problems and report a diminished sense of belonging. The community’s historical ties to the port have progressively weakened, exposing residents to ongoing socio-economic decline. This study explores the potential of fishing cultural heritage as a resource for local development and highlights the need for integrated governance between the fishing sector and the local authorities.

1. Introduction

Seafaring districts often experience a decline when fishing activity is replaced by other economic sectors. In this scenario, it is common for part of the population to move to other residential areas, for signs of urban physical deterioration to appear, and for an identity crisis to occur [1]. However, despite these transformations, such areas may remain connected to fishing and sustain a small-scale fishing industry. Fishing heritage and seafaring practices remain embedded in the collective imagination and continue to influence residents’ subjective identification with their community, even in times of crisis.

Fishing fosters a sense of belonging in coastal communities by shaping emotional connections to the seascape and contributing to the construction of a shared social memory [2]. This connection manifests both in an engagement with the sea and nature [3] and through material culture. Many fishermen perceive their trade as a way of life, profoundly shaping their community identity [4]. Additionally, traditional fishing activities, tools, materials, and marine structures possess a symbolic value that facilitates the psychological sense of community.

It has been shown that community cohesion in fishing villages is influenced by leadership, geographic proximity, and shared fishing practices [5]. However, fishing communities vary significantly in their social structures. While some traditional fishing communities historically functioned as closed, relatively isolated, and self-sufficient societies, many have since been integrated into larger urban centers that attract diverse populations and market their catches nationally and internationally [4]. Consequently, the conventional classification of communities based on their port of reference has been questioned insofar as mobility “at sea” offers the opportunity to develop more far-reaching social spaces [6].

1.1. Sense of Belonging to the Neighborhood

In psychological research, a community is defined as “a readily available, mutually supportive network of relationships upon which one could depend” [7], p. 1. These communities consist of broad groups of individuals who share a sense of mutual commitment, even if they do not personally know one another. Consequently, they function as meso-social structures that highlight the significant impact of indirect relationships on individual behavior. In residential areas, the creation of a community depends on neighbor interactions, collective belonging, and shared interests. The community thus has an objective and a subjective dimension, both of which are rooted in the interdependence of its members.

However, psychological studies have primarily focused on the subjective experience of belonging to a group. The psychological sense of community is defined as “the perception of similarity with others, an acknowledged interdependence with others, a willingness to maintain this interdependence by giving to or doing for others what one expects of them, and the feeling that one is part of a larger dependable and stable structure” [7], p. 157. The most common method of studying this concept involves psychometric evaluation, often using the model proposed by McMillan and Chavis [8], which defines four components of a sense of community: membership, mutual influence, satisfaction of needs, and shared emotional connection. While these factors are compatible with Seymour Sarason’s original definition, they have not yet obtained sufficient empirical support.

Consequently, alternative models have been proposed. Following a multilevel ecological framework, Jason et al. [9] developed a scale to assess the perceived quality of the reference community (e.g., the neighborhood), social interactions between members (e.g., neighbors), and the psychological significance of the community for the individual. This model facilitates the exploration of links between individuals and collectives, incorporating an intermediate level focused on interactions. To assess identification with a particular area, the perceived quality of residential conditions, neighborhood connectedness, and the feeling of shared emotional connection experienced by its members are all considered.

Prior research suggests that a sense of belonging to neighborhoods, blocks, districts, and cities is influenced by local rootedness and the length of time spent in the community [10,11]. It is also associated with engagement in community activities, such as walking [12], dog walking [13], and making use of nearby green spaces [14].

In this study, we examine a neighborhood with a homogeneous demographic composition and a shared history rooted in fishing activity. However, in recent decades, it has experienced a progressive decline, coinciding with the transformation of the European fishing sector. To identify its distinctive characteristics, we compared it with other neighborhoods in the urban center to which it belongs. While case studies have traditionally dominated community research, this comparative approach provides a valuable perspective on each neighborhood’s characteristics and highlights the unique aspects of the specific community context.

1.2. The Present Study

In this study, we evaluate the psychological sense of community among the residents of a fishing neighborhood in Motril, located south of Granada, Spain. Adopting a multilevel ecological model, we assess the perceived quality of the area, interactions among its residents, and the psychological significance of residing in a port-adjacent community. Additionally, we explore how the port’s transformation has impacted community integration and identification. El Varadero, the area under study, is situated next to the Port of Motril, approximately four kilometers from the urban center. Through a community survey, we compare the perceived problems, community assets, collective self-efficacy, and psychological sense of community between residents of El Varadero and the urban center. This case study examines the effects of changes in the fishing industry and port operations on the social cohesion of a community historically associated with fishing activities.

Therefore, the study pursues a dual objective: first, to analyze the processes and factors underlying both community decline and resilience in a traditional fishing neighborhood; and second, to compare these dynamics with those of the broader urban environment, an approach that advances beyond the conventional single-case studies typically focused on community development or transformation.

2. Study Area

El Varadero is a coastal neighborhood adjacent to the Port of Motril, located four kilometers from the urban center. According to the Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia, in 2023, Motril had a population of 58,939, with 48,714 residing in the urban center and 3450 in El Varadero (Among other population clusters and scattered settlements, according to a consultation on 11 November 2024 at: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/sima/nucleos.htm?CodMuni=18140). The life of the neighborhood has traditionally been closely tied to the commercial and fishing activities of the port.

The port features seven commercial docks and one fishing dock, with more than 350,000 square meters of industrial land. It operates three regular shipping lines connecting to Melilla and northern Morocco (With regular lines to Nador and Al Hoceima), serving both passenger and cargo traffic. Passenger volume peaks during “Operation Crossing the Strait of Gibraltar,” when a significant number of Europe-based workers travel to their countries of origin.

The Motril fishing fleet comprises 29 vessels engaged in trawling, purse seine fishing, and small-scale operations. The primary species caught include white shrimp (Parapenaeus longirostris), Motril shrimp (Plesionika edwardsii), octopus (Octopus vulgaris), Norway lobster (Nephrops norvegicus), mackerel (Scomber colias), sardine (Sardina pilchardus), hake (Merluccius merluccius), and red mullet (Mullus surmuletus). The closure of Moroccan fishing grounds, the administrative separation of the South Atlantic and South Mediterranean fishing areas, and the European Union’s Common Fisheries Policy have imposed restrictive measures that have gradually reduced fishing activity. This decline has affected the size of the fleet, the number of workers, and the volume of fish landed.

Since 2020, the fleet has been part of the Motril Fishing Producers Organization (OPP-85). This entity, led by the Fishermen’s Guild, has launched initiatives in marketing, environmental restoration, heritage conservation, and scientific research on extractive fishing practices.

In recent decades, the neighborhood has experienced economic and social decline, leading to its inclusion in the Intervention Program for Disadvantaged Areas under the Andalusian Regional Strategy for Social Cohesion and Inclusion (ERACIS). Residents have raised concerns primarily about safety and environmental issues, as well as declining employment opportunities in the fishing sector and at the port.

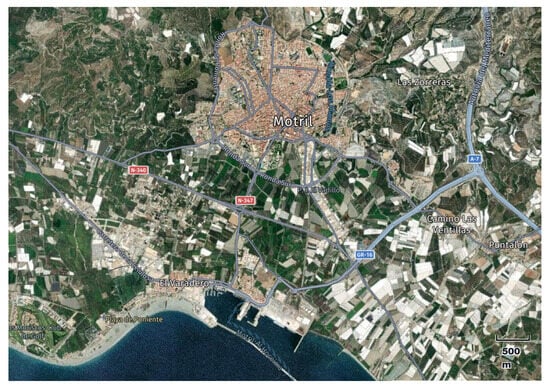

The El Varadero neighborhood, with the port, is separated by about four kilometers from the urban center, as shown in Figure 1. Situated on the open sea with no natural shelter, the Port of Motril lies at 36°43′06″ N latitude and 3°31′30″ W longitude.

Figure 1.

The neighborhood of El Varadero is situated on the coast of Granada, next to the port of Motril, and located four kilometers from the urban center. Source: satellite image from HERE WeGo, https://wego.here.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

3. Methods

The present case study was conducted in two phases using a sequential mixed methods design. First, a comparative survey was carried out with residents of the fishing district and the urban center of Motril. Second, key informants from the neighborhood and the fishing sector were interviewed. A meeting was also held with the fish producers’ organization to interpret the results.

A comparative approach was adopted to contextualize the characteristics of the seaside neighborhood within the broader context of the town. This method allowed for the identification of both shared urban features and distinctive spatial, social, community, and architectural elements specific to the seaside area.

3.1. Survey Participants

A total of 65 residents of Motril participated in the study, including 32 from El Varadero and 33 from the urban center. Participants were selected through purposive sampling to represent residents from both areas. At the time of the interview, the participants had an average age of 42 years, ranging from 18 to 80 (M = 42.43, SD = 15.92). Of the respondents, 53.8% were male (35) and 46.2% were female (30). The sample included seven foreign residents.

The two neighborhood samples varied in employment status and educational level. Respondents from El Varadero had lived in the neighborhood longer than those from the urban center (t = 3.534, p < 0.001). They also had a lower socioeconomic status (t = −2.898, p < 0.01) and scored lower on the comparative quality of life scale (t = −4.129, p < 0.001).

Participation was voluntary. Respondents provided informed consent, agreeing that their information would be used solely for research purposes. The researchers committed to maintaining anonymity in data handling and disseminating the results.

3.2. Key Informants

To validate the results of the community survey, qualitative interviews were conducted with five key informants connected to the neighborhood and the fishing industry. The participants in this qualitative phase included the president of the Fishermen’s Guild, the president of a neighborhood association, the administrator of a Facebook group on fishing communities, a retired fishing industry entrepreneur, and a former local fisheries councilor. Semi-structured interviews, each lasting approximately one hour, gathered insights on neighborhood issues, the community’s relationship with the port, the training needs of fishing sector workers, and potential strategies for local development. Participants consented to publicly share their opinions within the context of the study.

The survey results were also presented at a meeting with the fish producers’ organization, attended by seven participants over a two-hour session. The interviews and group discussions were recorded and fully transcribed. Data collection followed an inductive approach, exploring the respondents’ statements in depth until a sufficient level of empirical detail was reached [15]. Two members of the research team independently conducted the content analysis and later discussed the interpretation of the findings.

3.3. Survey Instruments

Respondents completed a series of psychometric scales assessing perceived problems, community assets, psychological sense of community, and perceived self-efficacy. Additional data were collected on perceived socioeconomic status, quality of life, length of residence in the current neighborhood, and the number of neighborhoods previously inhabited. Finally, respondents completed a sociodemographic data sheet, providing information on age, gender, nationality, marital status, educational level, and professional status at the time of the interview.

Perceived problems. Respondents rated 12 social issues in their neighborhood on a scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much”). These included unemployment, poor sanitation and waste management, crime, noise, disputes among neighbors, drug trafficking and consumption, challenges in immigrant integration, excessive tourism, poverty, housing prices, poor quality of public services, and the decline in the number of fishing boats. The 12-item list demonstrated strong internal consistency, with an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.835. To further validate the items, respondents also answered an open-ended question about what they considered “the most significant problems in the neighborhood.”

Three-factor Psychological sense of community scale [9]. This scale measures three factors related to a sense of community: Entity, Membership, and Self. It consists of 9 items scored on a scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”). In this case, respondents were asked to rate “the neighborhood where they currently reside”. The “entity” factor evaluates the characteristics of the reference community (e.g., “I think this neighborhood is a good neighborhood.”). The “membership” factor focuses on the relationships maintained with the members of the community (e.g., “there is reciprocity among the residents of this neighborhood”). Thirdly, the individual’s emotional connection with the group (self) is evaluated (e.g., “this neighborhood is important to me”). The scale yielded an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.798.

Community Assets Survey [16]. This inventory evaluates various community resources, including residential support, the physical conditions of the neighborhood, economic support, resident motivation, individual participation, community involvement, empowerment, institutional support, and collective self-efficacy. The items are rated on a scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). This study used the Spanish adaptation by Hombrados-Mendieta and López-Espigares [17], employing a reduced 44-item version to facilitate its inclusion in the context of the survey. The Community Assets Survey showed strong internal consistency, with a reliability alpha coefficient of 0.874.

Perceived self-efficacy. To measure perceived self-efficacy, we asked participants to indicate, on a scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much”), the abilities of their neighbors to act in response to a list of situations such as “witnessing a fight in the street,” “seeing an adult consuming drugs in public,” and “traffic and parking problems,” among others. The eight-item scale demonstrated good reliability, with an alpha coefficient of 0.742.

Comparative self-efficacy. Using the same items as the previous scale, participants were asked to compare the level of perceived self-efficacy between El Varadero and the historic center of Motril. Due to the low reliability of this measure (alpha = 0.402), it was excluded from further analysis.

The final section of the survey included an open-ended question to explore the main problems perceived by respondents. Responses were grouped inductively, and five key categories were identified: neighborhood maintenance issues and limited available services (n = 28); socioeconomic and public order issues (n = 25); lack of institutional support and infrastructure problems (n = 18); neighbor interaction (n = 15); and problems related to port activity (n = 14). The coding and thematic analysis of this qualitative section served as an element of triangulation and comparison with the survey results.

4. Results

Residents of the fishing neighborhood perceived more problems than those of the urban center of Motril. They expressed concerns about the physical conditions of the area and the lack of institutional support. Additionally, they highlighted issues related to environmental pollution, the impact of port activities, and drug trafficking. This perceived decline is indirectly reflected in a diminished sense of belonging to the community.

Consistent with the aims of this study, we proceed to examine the community processes in the traditional fishing neighborhood, contrasting them with those observed in the urban center. The survey data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics V. 30.

4.1. Perceived Problems and Collective Self-Efficacy

Table 1 presents respondents’ evaluations of perceived problems. Residents of El Varadero are particularly concerned about the reduction in the number of fishing boats (M = 4.12, SD = 0.9). Noise (M = 3.90, SD = 1.2) and drug trafficking and consumption (M = 3.75, SD = 1.3) are also among the most pressing concerns.

Table 1.

Comparison of perceived problems in El Varadero and the urban center of Motril.

In all cases, except for housing prices, perceived problems are more pronounced in El Varadero than in the urban center of Motril. The most notable differences relate to the decline of the fishing fleet, drug trafficking, and crime. In El Varadero, there is also a comparatively greater perception of neighbor-related conflicts.

Housing affordability emerges as the only issue that appears to impact both the central and peripheral areas of Motril to a similar extent. In both cases it is considered a fairly important problem.

Table 2 presents the results of the collective self-efficacy scale. Overall, Motril residents score below 3 (out of 5) in their perceived ability to collectively address problems affecting their living conditions. Few differences were observed between residents of El Varadero and those of the urban center.

Table 2.

Perceived collective self-efficacy in El Varadero and the urban center of Motril.

Significant differences emerged in only two specific items. As expected, based on their geographic proximity, El Varadero residents perceive themselves as more capable of addressing problems related to port activities (t = 5.860, p < 0.001) and issues concerning environmental pollution and noise (t = 2.251, p < 0.05).

When comparing both areas, in all cases, the residents of the urban center were rated higher in terms of their capacity to act than the residents of El Varadero. This perception was more pronounced among residents on the outskirts. Again, the only exception concerns the issues related to port activities, which are considered to fall within El Varadero’s sphere of influence.

This perception aligns with the recent mobilization of residents against the port fencing, as well as the noise and pollution attributed to port activities. As shown in Figure 2, messages criticizing the port’s impact on residents’ quality of life are visibly displayed on balconies throughout the neighborhood. Also, with the existence of associations that seek to recover and enhance the maritime heritage of this coastal district.

As Table 2 shows, elements of community decline and resistance can coincide in the same territory. We return to this aspect in the qualitative analysis section.

4.2. Sense of Community and Community Assets

Compared to residents of the urban center, those in El Varadero feel that institutions neglect their neighborhood and provide insufficient political or institutional support. They highlight the need for greater resource investment to implement improvements and develop long-term projects. Additionally, they perceive the neighborhood as inadequately maintained.

Table 3 presents the results of the psychometric scale measuring the sense of community. Residents of the urban center of Motril report a stronger sense of belonging to their community than those in El Varadero (t = −3.12, p < 0.001). This difference largely corresponds to the perceived quality of the neighborhood, as reflected in the “Entity” factor. El Varadero scores lower on items describing it as “a good neighborhood,” according to the residents.

Table 3.

Psychological sense of community within the neighborhood of residence.

Additionally, some differences are observed in the type of interaction residents have with their neighbors. In the urban center, they report feeling safer when sharing opinions or asking for advice from their neighbors (t = −2.6, p < 0.01).

Pearson correlation analysis revealed a negative association between the overall index of perceived problems and the sense of belonging to the community (r = −0.441, p < 0.01). This relationship is even stronger when considering only the “Entity” factor (r = −0.535, p < 0.01), suggesting that the perceived quality of the neighborhood significantly influences residents’ identification with it (The “Self” factor, which refers to the respondent’s connection with their neighborhood of residence, shows a higher correlation with self-efficacy (r = 0.397, p < 0.01) than the total sense of community scale).

Additionally, the psychological sense of community is positively associated with perceived self-efficacy (r = 0.321, p < 0.01). These correlations are independent of the length of residence in the neighborhood and the number of previous neighborhoods where respondents have lived.

Table 4 presents the results for factors of the community assets scale. Overall, no significant differences were observed between the urban center and the outskirts (El Varadero) in the availability of community assets. Across all dimensions, scores generally fall within the lower-middle range. Only the motivation and empowerment subscales exceed a score of 3 out of 5, indicating that residents report a certain degree of motivation and capacity to engage in neighborhood issues.

Table 4.

Community assets factors in El Varadero and the urban center of Motril.

When comparing specific factors, respondents in El Varadero report lower scores than those in the urban center for physical conditions (t = −3.307, p < 0.001), economic support (t = −2.051, p < 0.05), and institutional support (t = 0.757, p < 0.05). Residents of El Varadero perceive their neighborhood as being in poor physical condition and receiving insufficient economic and institutional support from public authorities.

Community assets are positively correlated with the psychological sense of community (r = 0.435, p < 0.01) and collective self-efficacy (r = 0.422, p < 0.01). Notably, the “Self” subscale of the sense of community belonging also shows a strong positive correlation with the total community assets score (r = 0.532, p < 0.01). Conversely, community assets are negatively correlated with perceived problems (r = −0.306, p < 0.05).

Participation and empowerment are the two highest-scoring factors in the El Varadero neighborhood. Notably, although residents are aware of the area’s challenges, they trust in their neighbors’ willingness to get involved in addressing them. Despite physical deterioration and a lack of institutional support, they perceive the presence of community resources that could help improve their living conditions.

4.3. Thematic Analysis of Perceived Problems

As part of the survey, participants identified the main issues they perceived in a final qualitative section. Residents of El Varadero reported significantly more problems, averaging 3.95 issues per person, compared to 1.73 in the urban center. This suggests a higher level of dissatisfaction among those living in peripheral areas.

The qualitative analysis grouped the reported issues from both areas into five thematic categories. In El Varadero, the most frequently mentioned concerns included deteriorating physical conditions of the neighborhood, insufficient institutional support, and weak collaboration among neighbors—often reflecting broader challenges related to organization and maintenance. Environmental pollution and drug trafficking also emerged as prominent issues.

By contrast, urban center residents primarily focused on problems related to infrastructure and maintenance, with notably less emphasis on institutional support or social cohesion. Interestingly, concerns linked to port activity and neighborhood cohesion were largely absent in responses from downtown residents, underscoring the contrasting realities experienced by central and peripheral communities.

4.4. Key Informant Analysis

The key informants interviewed are fully aware of the transformation of the Port of Motril, noting a gradual decline in the prominence of fishing activity. As a result, sector representatives express concerns about the long-term sustainability of the fishing fleet.

“Granada was not a maritime province. It belonged to Almeria. The technicians came from there. At that time, we were dedicated almost exclusively to fishing. Our income was from fishing. At school, it was clear to us that we were going to be fishermen. In 2005, the Port Authority of Granada was created. Technicians arrived from Granada and from abroad. Cargo traffic began to develop. Between 2008 and 2014, 60 percent of the fishing vessels were lost. Now, we have become a nuisance. The port authority keeps pushing us further and further away. If we disappear, we’ll be doing them a favor…”.(E1, head of the Fishermen’s Guild)

“The port has grown without considering its people. The port has always relied on fishing, but there came a point when it changed, and goods began to have greater relevance”.(E1, head of the Fishermen’s Guild)

“This has always been a fishing port. But now the merchant sector is dominant and there are fewer and fewer fishing boats left. They will renovate the port in a few years, and the fishing port will be moved from here (…). This could take a lot of life out of the neighborhood, which will be completely surrounded by the infrastructure of the commercial port”.(E3, president of the Neighborhood Association)

This has indirectly impacted the neighborhood of El Varadero, whose history has always been closely tied to the port. Residents feel that the port authority has disrupted this connection, increasingly isolating the port from local life. This shift is evident in urban redesign efforts, which have separated the neighborhood from the passenger transport area. Changes to port access have reduced entry points for residents and restricted direct access to the beach. These factors have further contributed to the growing disconnect between the port and the neighborhood.

“Here, the most important thing for the people of El Varadero was that the La Azucena beach was there, but with the construction and expansion of the port, they lost direct access”.(E3, president of the Neighborhood Association)

“When the entrance to the neighborhood was cut off, it took away its life because that was like putting a wall or a roof on what was the port… and then the neighborhood was left isolated”.(E4, fishing sector entrepreneur)

“They have taken the beach, they are going to take the fishing port, and they are going to leave us surrounded by the port platform. The only thing left would be for them to buy all the houses and take over the whole neighborhood. I wouldn’t be surprised if that happened one day, as the port is getting bigger and bigger and needs logistics areas”.(E3, president of the Neighborhood Association)

“El Varadero was a fishing neighborhood before it was a port… Now, the opportunities generated by the port benefit outsiders—the technicians. Those of us from the neighborhood only have the option of fishing, and that’s it. That’s why when I hear the port authority claim they are an “open port,” it’s something I can’t understand; it bothers me…”.(E1, head of the Fishermen’s Guild)

Nevertheless, fishing continues to occupy a central place in the cultural and symbolic heritage of the locality. The social memory of the residents of El Varadero is significantly linked to fishing activities, which have experienced a marked decline in recent decades. Despite reductions in fishing quotas and the functional transformation of the port, the fishing sector continues to play a role in the local economy. Some informants highlight that fishing shaped their childhood and remains integral to the identity of the neighborhood’s residents:

“El Varadero has a great history: a seafaring history because it is a seafaring neighborhood. Here, we call someone a ‘Marengo’ if they live, grow up, and have always lived by the sea. This culture is not found in other neighborhoods. What sets it apart from other neighborhoods is precisely the link between the sea and the people here”.(E2, administrator of a Facebook group about fishing communities)

“My identity is Marenga (That is, Mediterranean maritime identity); it comes from the people of the sea, and all my family or those around us have lived, in one way or another, through fishing (…). I remember going to the fish market with my father, who was a fisherman, and then we had a business, a fish restaurant. I was 5 or 6 years old; I would walk around the fish market; the fish was in the boxes, on the floor. So, of course, I have walked in that water, in those boxes… that smell, every day on my body, in my nose, in my senses…”.(E5, former fisheries councilor)

“And we must not forget that many people returned to fishing, seeking refuge during the construction crisis”.(E1, head of the Fishermen’s Guild)

As a result of the fishing crisis, the residents express a strong nostalgic identification with the fishing port’s past while simultaneously recognizing the ongoing decline of their coastal neighborhood. This sentiment is further reinforced by the physical separation from Motril’s urban center. The once-thriving fishing quarter has become a no man’s land, with residents widely perceiving that the neighborhood has entered a cycle of progressive deterioration.

“In El Varadero, there were a lot of bars, businesses, stores. It was a hive of activity, there was a lot of life, and the neighborhood port, the port of El Varadero, was very important”.(E2, Administrator of a Facebook group about fishing neighborhoods)

“Varadero used to have more life because we were more involved in the port. We were all people from the town. My parents came from Malaga. I arrived on 25 January 1947, when I was 10 years old, and we came to sell fish, to work at the fish market (…). Now, they treat it as a neighborhood that is a little bit abandoned. However, in the 50s and 60s, there was a fabulous festival here, the Virgen del Carmen, which was celebrated with so much glory, so much joy”.(E4, fishing industry entrepreneur)

“The neighbors here feel excluded; they believe, in their minds, that everything happens in Playa Granada or Motril center, that attention is directed to other more prominent neighborhoods”.(E2, administrator of a Facebook group about fishing neighborhoods)

“Over time, it has deteriorated a bit… Those who could leave have left, and those who couldn’t are stuck here in a place that is no longer truly a fishing community”.(E1, head of the Fisherman’s Guild)

Paradoxically, community development initiatives aimed at reversing the neighborhood’s decline often draw on its seafaring past as a reference:

“…that Motril looks towards the sea, that Motril does not turn its back on the sea, because the most precious treasure that Motril has is its fishing port; we are the only fishing port in the province of Granada”.(E5, former fisheries councilor)

These collective memories and sentiments of loss are not only expressed through narratives and interviews but are also materially inscribed in the neighborhood’s landscape, as shown in Figure 2. The tension between past identity and present transformation becomes visible in the everyday fabric of El Varadero, where residents continue to resist the perceived marginalization of their community and its maritime heritage.

Figure 2.

A walk through the area reveals various signs of the neighborhood’s ongoing transformation. (a) A fence now separates the neighborhood from the port. (b) Residents have hung banners from their balconies protesting against noise pollution and the use of toxic substances in port operations. (c) Several buildings formerly used for maritime and fishing activities have fallen into disuse. (d) Some houses in the neighborhood exhibit visible signs of physical deterioration. Photos: IMJ and MRUD.

5. Discussion

Through a comparative case study, we found that residents of the fishing neighborhood of El Varadero in Motril perceive more social problems than those in the urban center. In the fishing district, concerns were particularly focused on the decline of the fishing sector and the environmental impact of port activities. These two issues feed into each other in residents’ perceptions, as exposure to noise and port activities becomes harder to justify when employment opportunities in the sector are diminishing. Residents also described the physical conditions of the neighborhood in negative terms and expressed a lack of institutional and economic support from the public authorities. Over time, a sense of abandonment has gradually taken hold.

Furthermore, the level of perceived problems was negatively related to the sense of belonging to the community. Specifically, the “Entity” factor of the psychological sense of community scale revealed that the perceived quality of the residential environment influences the degree of identification with the neighborhood where people live. In urban settings, research has shown that neighborhood reputation plays a crucial role in reproducing patterns of social inequality. Specifically, some neighborhoods are caught in a negative spiral where a poor reputation leads to resident outmigration, decreased civic engagement, and, ultimately, higher levels of poverty, crime, or violence [18]. The neighborhood examined in this case study could be in the early stages of such a process.

In contrast, the psychological sense of community was positively correlated with collective self-efficacy. In this case, the “Self” factor of the scale showed a significant relationship with the sense of belonging. This factor also correlated positively with the perception of community assets in the neighborhood. These findings support a framework that evaluates the sense of community by incorporating meaning, degree of commitment, and emotional connection with the collective, as experienced by members at an individual level [9].

This distinction opens an interesting avenue for exploring the interaction between collective and personal factors in neighborhood attachment. On the one hand, the quality of living conditions and the neighborhood’s reputation appear to shape residents’ perceived identity. On the other hand, the relative importance of the neighborhood for the individuals influences their motivation to engage in and take responsibility for community affairs. This second aspect connects to opportunities for resident empowerment and participation. From a multilevel ecological perspective, the perceived quality of the neighborhood and its psychological importance constitute two distinct dimensions of the psychological sense of community [9], with neighbor interactions situated at an intermediate level between them.

However, the limitations of our study prevent us from being conclusive in this regard. The survey was based on a small number of interviews, and participants from the urban center came from diverse neighborhoods. Nonetheless, our case study highlights opportunities for further research, particularly given that the factors constituting the psychological sense of community remain an open question in community studies [19]. Additionally, the qualitative phase of our research validated the relevance of adopting a multilevel ecological approach to studying community identity.

Some fishing neighborhoods—such as the one in Motril—illustrate this tension between the objective conditions of the environment and the psychological sense of community for its residents. While El Varadero’s residents are acutely aware of the neighborhood’s deterioration, which coincided with the decline of the fishing sector, they continue to view their seafaring heritage as a positive and distinctive element of their community identity. Even among Motril’s broader population, the town’s seafaring past evokes, in the collective imagination, an image of a tightly knit and authentic community. It evokes a sense of a “lost community” [20].

This positions fishing heritage as a central element in any community development initiative. Residents frequently invoke their seafaring heritage to advocate for greater public attention and investment in the neighborhood. The fishing producers’ organization also recognizes the cultural and symbolic significance of fishing activities as a valuable asset for local development. Indeed, in recent decades, various initiatives have sought to diversify the economies of coastal communities by transforming fishing practices and traditions into tourism resources [21,22,23,24].

Coastal communities can be strengthened through sustainable strategies such as economic diversification, fishing tourism, community-based aquaculture, and participatory governance of marine protected areas. Achieving this involves integrating local culture [25] and adapting governance to reflect community needs and expectations [26]. Long-term socioecological sustainability also depends on linking fisheries with other marine and land-based activities [27].

5.1. The Transformation of the Fishing Port into a Maritime Transport Hub

El Varadero is a traditional coastal community that evolved from a fishing neighborhood to a fishing port, and from a fishing port to one primarily focused on passenger and cargo transport. Although fishing activity remains significant, with approximately 30 vessels, the sector’s relative importance has diminished in recent decades, partly due to European Union fishing quota regulations. Fishing efforts have become concentrated in a smaller number of vessels, which now play a secondary role in the port’s reconfiguration. The changes observed in Motril mirror international trends, where many ports have shifted towards tourism, recreation, and logistics services [28,29].

This transformation has directly impacted a neighborhood that has historically been linked to the port and, in recent decades, has led to a growing sense of detachment between the two. According to the residents of El Varadero, passenger and cargo transport has not generated significant economic benefits for the neighborhood. Moreover, new job opportunities require specialized training, primarily attracting workers from outside Motril. As a result, there is a growing sentiment that “the port no longer needs the neighborhood,” meaning that, in the medium or long term, the very survival of El Varadero could be at stake. Despite the port’s significance in local identity, a type of disconnect is observed that has already been described in other geographical contexts. Specifically, ports do not necessarily have a significant impact on the economic development of the region where they are located, and at times, they seem to serve areas that are geographically distant [30]. This dynamic particularly affects marginalized fishing communities, which have a limited capacity to adapt to change [31].

Integrating the governance of the port and the city—or, in this case, a neighborhood separated from the city—presents a significant challenge. A key goal is to achieve a balanced transition between the declining fishing sector and the booming passenger and cargo transport industry. More broadly, the aim is to ensure a sustainable relationship between the port and the city. One approach could be to mitigate the environmental impact of port activities through improved waste collection [32] and control of ship-generated air and noise pollution [33]. Additionally, enhancing resident engagement and fostering community coalitions could be crucial in revitalizing coastal communities [34,35].

5.2. Relegation and Decline of the Fishing District

As the name of the neighborhood itself suggests (In Spanish, “Varadero” means place for beaching, where later a slipway, a dock, or a shipyard may be built), the port of Motril was constructed on the historic beach where fishing crews traditionally beached their boats. Over time, buildings and service infrastructures were organically developed around these areas to support fishing activities, including huts, shipyards, carpentry workshops, and sheds for commercializing the catch. The construction of the port began in 1908 and continued for several years. By the early 20th century, the beach-shipyard area was a hub for small-scale maritime fishing and the trade of goods such as sugar cane, salt, and iron. This type of activity gave the waterfront an industrial imprint, marked by warehouses and chimneys, while creating an environment where the fishing neighborhood and the port entered a process of “mutual reinforcement” [36].

However, with the subsequent boom in commercial activity and passenger transport driven by the port authority [37], fishing traffic gradually became relegated to a secondary role [38]. Today, the fishing dock is surrounded by infrastructure dedicated to freight and passenger transport, encircling it on both the east and west sides. The removal of the lamppost and staircase of the old fishing pier became a symbolic turning point for the residents, marking the redevelopment of the dock and the decline of the area. Currently, residents can only access the fishing dock through a gated perimeter enclosing the entire port area (While entry and exit are possible by simply calling an intercom, it is a physical barrier that holds significant meaning when considering the historical spatial relationship between the neighborhood and the fishing dock). This has led port managers to consider the current location of the fishing area as problematic, viewing it as a “barrier” between the commercial and passenger docks [37], p. 631. Consequently, the Motril port master plan envisions relocating the fishing and nautical-sports dock, along with its service facilities, to the west of the current site. This move could represent another step in the practical, physical, and symbolic relegation of the fishing neighborhood.

5.3. Implications for Sustainable Development

Recent experiences of sustainable development in coastal communities highlight the transformative potential of locally grounded, community-driven strategies. Approaches that prioritize local participation, cultural capital, and environmental stewardship—such as fisheries tourism and ecotourism—have demonstrated their capacity to foster both economic resilience and social justice [39,40].

Within this broader framework of community-based development, women’s leadership emerges as a critical factor in strengthening collective action and redefining the local economy. Evidence from Andalusia [41] shows that women-led initiatives in economic diversification—spanning tourism, the valorization of natural and cultural heritage, product processing, and local marketing—are reshaping socio-economic dynamics in traditionally male-dominated contexts. Recognizing women’s contributions within family enterprises, cooperatives, and community organizations enhances social trust, participatory governance, and collective well-being in fisheries systems [42,43].

This localized and inclusive model of development stands in marked contrast to the dominant “Blue Growth” paradigm promoted by European maritime policy, which prioritizes large-scale industrial sectors such as shipbuilding, port infrastructure, energy, mass tourism, and commercial logistics, often at the expense of small-scale fisheries and traditional livelihoods [44,45]. By overlooking the social and cultural fabric of coastal communities, such growth-oriented frameworks contribute to economic marginalization and the erosion of heritage-based practices. In contrast, community-driven initiatives anchored in women’s leadership demonstrate a more equitable and sustainable pathway, aligning economic diversification with cultural continuity, social inclusion, and environmental care.

In future research, it would be valuable to examine the role of port workers in commercial and passenger transport activities, as most do not reside in El Varadero and constitute a transient population during the working week, potentially shaping the social and economic dynamics of the neighborhood.

6. Conclusions

The relationship between the fishing neighborhood of El Varadero and the Port of Motril illustrates the complex interaction between the fishing sector and regional governance. The life of the fishing neighborhood has been inextricably linked to the port. However, the restructuring of the fishing sector has diminished both its scale and its economic significance within the local economy. This decline has been further compounded by the increased focus on passenger and freight transport in the port’s activities. At the same time, port management falls under the jurisdiction of the central government and involves stakeholders that are often disconnected from the local environment. As a result, the link between the local neighborhood and the port has progressively weakened.

To counteract the decline of the local community, fostering dialogue between port managers and the city’s public administration is essential, along with developing strategies to reconnect the neighborhood with the port [46]. In this context, tourism and fishing cultural heritage are among the resources that could represent valuable opportunities for revitalizing the area. In any case, community strengthening and neighborhood participation will ultimately play a decisive role in shaping the future of this fishing district. As has been shown in other contexts, emotions can drive leadership and collective action [47].

This study presents a case-based analysis of the decline and resistance of a historic fishing neighborhood, making several key contributions to urban and community studies. First, while much of the existing literature emphasizes processes of community building, our research highlights a case of community decline shaped by broader dynamics of port transformation and social marginalization. Second, rather than analyzing the neighborhood in isolation, we adopt a comparative approach that situates El Varadero within the wider context of the coastal city, thereby offering a more nuanced understanding of community processes and senses of belonging. Third, this comparison reveals that despite the erosion of social and economic structures in El Varadero, the fishing tradition endures as a source of symbolic and affective resistance, anchoring a collective identity that challenges dominant narratives of decline. Importantly, our study innovates by foregrounding the psychological sense of community, an aspect rarely explored in case studies of coastal cities and fishing communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.-J., D.F.-d.-C. and M.R.U.-D.; methodology, I.M.-J. and M.R.U.-D.; software, I.M.-J. and M.R.U.-D.; validation, I.M.-J., D.F.-d.-C. and M.R.U.-D.; formal analysis, I.M.-J., D.F.-d.-C. and M.R.U.-D.; investigation, I.M.-J. and M.R.U.-D.; resources, I.M.-J. and D.F.-d.-C.; data curation, I.M.-J. and M.R.U.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.-J.; writing—review and editing, I.M.-J., D.F.-d.-C. and M.R.U.-D.; visualization, I.M.-J., D.F.-d.-C. and M.R.U.-D.; supervision, I.M.-J.; project administration, I.M.-J.; funding acquisition, I.M.-J. and D.F.-d.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study explores the comparative analysis of neighborhoods as part of the project “Multiple senses of community in adjoining neighborhoods: an approach based on the analysis of personal networks” (PID2021-126230OB-I00), funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain. The field work, developed between September and November 2024, was funded by the Society for the Development of Coastal Communities, with the project “Study of needs and resources in the seaside neighborhood of El Varadero (Motril)” led by Isidro Maya Jariego.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the University of Seville Research Foundation (FIUS, CP: 5165/GT: 0227). The activities were subject to Regulation (EU) 2016/679 on the protection of personal data, as well as to Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights. Prior to participation, all participants were provided with detailed information about the study’s objectives, procedures, and their rights, including the right to withdraw at any time without any repercussions.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the interviews were conducted. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained throughout the study, and the collected data were securely stored and used solely for research purposes. They were fully informed about the objectives and procedures of the research, the voluntary nature of their participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without any consequences.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Motril Fisheries Producers Organization (OPP85) for their collaboration during the fieldwork, as well as the Motril residents who participated in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thompson, C.; Johnson, T.; Hanes, S. Vulnerability of fishing communities undergoing gentrification. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakzad, S.; Griffith, D. The role of fishing material culture in communities’ sense of place as an added-value in management of coastal areas. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2016, 5, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakel, J.T. A Maritime Sense of Place: Southeast Alaska Fishermen and Mainstream Nature Ideologies; University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Ramírez, C.E.; Ota, Y.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M. Fishing as a livelihood, a way of life, or just a job: Considering the complexity of “fishing communities” in research and policy. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2023, 33, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.M.; Bodin, Ö.; Barnes, M.L. Untangling the drivers of community cohesion in small-scale fisheries. Int. J. Commons 2018, 12, 519–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Martin, K.; Hall-Arber, M. Creating a place for” Community” in New England fisheries. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2008, 15, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason, S.B. The Psychological Sense of Community: Prospects for a Community Psychology; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason, L.A.; Stevens, E.; Ram, D. Development of a three-factor psychological sense of community scale. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 43, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.T.; Sonn, C.C.; Bishop, B.J. (Eds.) Psychological Sense of Community: Research, Applications, and Implications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.L. Psychological sense of community: Suggestions for future research. J. Community Psychol. 1996, 24, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Frank, L.D.; Giles-Corti, B. Sense of community and its relationship with walking and neighborhood design. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toohey, A.M.; McCormack, G.R.; Doyle-Baker, P.K.; Adams, C.L.; Rock, M.J. Dog-walking and sense of community in neighborhoods: Implications for promoting regular physical activity in adults 50 years and older. Health Place 2013, 22, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipeolu, A.A.; Ibem, E.O.; Fadamiro, J.A. Influence of green infrastructure on sense of community in residents of Lagos Metropolis, Nigeria. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, M.L.; Calarco, J.M. Qualitative Literacy. A Guide to Evaluating Ethnographic and Interview Research; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jakes, S.; Shannon, L. Community Assets Survey; The University of Arizona: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hombrados-Mendieta, I.; López-Espigares, T. Dimensiones del sentido de comunidad que predicen la calidad de vida residencial en barrios con diferentes posiciones socioeconómicas. Psychosoc. Interv. 2014, 23, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, M.R.; Ward, C.; Jackson, J.E.; Muirbrook, K.A.; Andre, A.N. Taking another look at the sense of community index: Six confirmatory factor analyses. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 48, 1410–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellman, B.; Leighton, B. Networks, neighborhoods, and communities: Approaches to the study of the community question. Urban Aff. Q. 1979, 14, 363–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, S.; Robertson, R.A.; Hall-Arber, M. Fishing heritage festivals, tourism, and community development in the Gulf of Maine. In Proceedings of the 2005 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium, Bolton Landing, NY, USA, 10–12 April 2005; Volume 341, pp. 420–428. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, S.; Witman, J. Human ecological sources of fishing heritage and its use in and impact on coastal tourism. In Proceedings of the 2006 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium, New York, NY, USA, 9–11 April 2006; Burns, R., Robinson, K., Eds.; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 394–402. [Google Scholar]

- de Madariaga, C.J.; del Hoyo, J.C. Enhancing of the cultural fishing heritage and the development of tourism: A case study in Isla Cristina (Spain). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 168, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martindale, T. Heritage, skills and livelihood: Reconstruction and regeneration in a Cornish fishing port. In Social Issues in Sustainable Fisheries Management; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- Tommarchi, E.; Jonas, A.E.G. Culture-led regeneration and the contestation of local discourses and meanings: The case of European maritime port cities. Urban Geogr. 2024, 46, 632–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthoven, L. How do local communities perceive marine protected area governance, management, surrounding development, and outcomes? A systematic review. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.C.L.; Piñeiro Antelo, M.Á. Fishing Tourism as an Opportunity for Sustainable Rural Development—The Case of Galicia, Spain. Land 2020, 9, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.C. A Study on Strategic Planning of Fishery Port Transformation for Tourism and Recreational Development. Master’s Thesis, National Sun Yat-sen University, Taiwan, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, I.S.G.; Ounanian, K. From fishing port to transport hub?: Local voices on the identity of places and flows. PORTUSplus 2020, 10, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Gripaios, P.; Gripaios, R. The impact of a port on its local economy: The case of Plymouth. Marit. Policy Manag. 1995, 22, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.; Ma, G. Marginalisation of the Dan fishing community and relocation of Sanya fishing port, Hainan Island, China. Isl. Stud. J. 2017, 12, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilewska-Bien, M.; Anderberg, S. Reception of sewage in the Baltic Sea–The port’s role is in the sustainable management of ship wastes. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tichavska, M.; Tovar, B. Port-city exhaust emission model: An application to cruise and ferry operations in Las Palmas Port. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 78, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, L.; Dumouchel, R.; Pontarelli, H.; Casali, L.; Smith, W.; Gillick, K.; Godde, P.; Dowling, M.; Suarez, A. Fishing community sustainability planning: A roadmap and examples from the California coast. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, L.; Casali, L. The role of social capital in fishing community sustainability: Spiraling down and up in a rural California port. Mar. Policy 2022, 137, 104934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguís-Climent, D. Puertos, Arquitectura, Patrimonio. Los Puertos Autonómicos en Andalucía. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Seisdedos, M. Puerto de Motril (Granada): Transformación de un puerto al servicio del tráfico de pasajeros. In XIV Jornadas Españolas de Ingeniería de Costas y Puertos; Gómez-Martín, E.E., Ed.; Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2018; pp. 623–632. [Google Scholar]

- Bajurec, P. Ficha Análisis Puertos Estatales Andalucía; Asociación Paisaje Limpio: Madrid, Spain, 2022; 419p, Available online: https://www.programapleamar.es/sites/default/files/archivos/proyectos/2023/ficha_analisis_puertos_pesqueros_estatales.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Ghate, A.D.; Roy, J. Local Community Participation based Ecotourism Management for Sustainable Development of Marine Protected Areas. Nat. Eng. Sci. 2024, 9, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Bakar, N.A.A.; Zairul, M.; D’Silva, J.L. Exploration of Fisheries Tourism as an Alternative to Diversify the Livelihoods of the Fishing Communities in Kampung Kuala Muda. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 1598–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayuela, P. Estudio Sobre el Emprendimiento Femenino en las Zonas de Pesca de Andalucía. Fomento de la Cultura Emprendedora y de las Actividades Empresariales Ligadas a la Pesca Realizadas Por Mujeres. [Study on Female Entrepreneurship in the Fishing Areas of Andalusia. Promoting an Entrepreneurial Culture and Fishing-Related Business Activities Undertaken by Women.] Grupos de Desarrollo Pesquero Andaluces. 2017. Available online: https://www.pescamalaga.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/4.-Emprendedoras-en-las-Zonas-de-Pesca.-Casos-pr%C3%A1cticos..pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Harper, S.; Grubb, C.; Stiles, M.; Sumaila, U.R. Contributions by Women to Fisheries Economies: Insights from Five Maritime Countries. Coast. Manag. 2017, 45, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, S.; Conway, F.; Rusell, S. Acknowledging the voice of women: Implications for fisheries management and policy. Mar. Policy 2016, 74, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penca, J.; Ertör, I.; Ballesteros, M.; Briguglio, M.; Kowalewski, M.; Pauksztat, B.; Cepic, D.; Piñeiro-Corbeira, C.; Vaidianu, N.; Pascual-Fernández, J.J.; et al. Rethinking the Blue Economy: Integrating social science for sustainability and justice. npj Ocean Sustain. 2025, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A.M.E.; Lopes, D.A.; Mateus, L.; Penha, J.; Súarez, Y.R.; Catella, A.C.; Nunes, A.V.; Arenhart, N.; Chiaravalloti, R.M. The economic displacement of thousands of fishers in the Pantanal, Brazil: A telling story of small-scale fisheries marginalization worldwide. Fish Fish. 2024, 25, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrie, J.; Raimbault, N. The port–city relationships in two European inland ports: A geographical perspective on urban governance. Cities 2016, 50, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maso, A.; Capo, F.; Sancino, A.; Gerli, P.; Mora, L. Because we love our place: The role of emotions in place-based leadership. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2529953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).