1. Introduction

China’s rapid economic development has persisted for years; however, this progress has been accompanied by environmental challenges stemming from high energy consumption, pollution, and emissions. These issues not only affect production and quality of life, but also pose constraints on the overall sustainable development of the economy and society [

1]. To cope with these challenges, the Chinese government, in its 2021 work report, incorporated goals aimed at peaking carbon emissions and achieving carbon neutrality. Embracing a sustainable development approach is imperative for China to address these environmental concerns and work toward meeting the outlined goals [

2,

3]. Within this broader policy turn, green finance has been identified as a key instrument to channel financial resources toward low-carbon activities and to support the real economy’s green transformation.

Building on the 2016 Guidelines for Establishing a Green Financial System, which laid out a comprehensive policy toolkit for green credit, green bonds, environmental information disclosure, and performance evaluation, the State Council, in June 2017, designated Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Guangdong, Guizhou and Xinjiang as Green Financial Reform and Innovation Pilot Zones (GFRI).

The pilot zones were created to integrate these largely framework-level arrangements into an operational, place-based system that could test how financial factor markets can be steered toward green transformation. These pilots were designed to localize and operationalize the national green finance framework in specific regions, and to test how financial factor markets could be steered toward green development.

The central policy intention of GFRI is to strengthen financial institutions’ commitment to green and sustainable development by redirecting credit and investment toward environmentally friendly projects, stimulating firms’ participation in green activities, and ultimately supporting China’s agenda of ecological civilization and green growth. Companies, as rational economic entities, are expected to exhibit adaptive behavioral responses to such policies. Faced with emission reduction and cost pressures imposed by GFRI, companies will adjust their production, operation, investment strategies, and financing decisions based on their own resources and technological advantages [

4]. The flourishing of financial markets amid GFRI has created new investment pathways for enterprises, leading to a continuous rise in the proportion of their financial assets. This financialization behavior, while offering new profit modes, may pose risks to the long-term development of enterprises, especially high-energy-consuming and polluting ones. However, the relationship between pilot policies like GFRI and corporate financialization has not received sufficient attention in the existing research. As a crucial green financial policy, the impact of GFRI on corporate financialization merits further exploration.

This paper will focus on the following questions: Does GFRI enhance or inhibit CF? What is the underlying mechanism of such impacts? How do the impacts of GFRI on CF differ at the regional, industrial, and enterprise levels? Exploring these questions will enhance our theoretical understanding of the micro-economic effects of GFRI and offer policy insights for promoting long-term corporate development through GFRI.

The remaining structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides an institutional background and literature review;

Section 3 puts forward the research hypotheses;

Section 4 introduces models, variables, and data;

Section 5 presents empirical analysis;

Section 6 examines the heterogeneity and mechanisms in policy effects; and

Section 7 concludes and proposes policy implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Micro-Influence of GFRI on Enterprises

Scholars have undertaken comprehensive investigations to evaluate the micro-impacts of these pilot zones. To begin with, in relation to the influences on corporate investment efficiency, Yan et al. observed significant reductions in inefficient and excessive investments among enterprises situated in the pilot zones [

5]. Their findings unveiled a mediating effect between the establishment of these zones and corporate investment efficiency, encompassing the mitigation of agency problems and an augmentation in R&D investments, consequently enhancing overall investment efficiency. Zhang et al. indicated a positive influence exerted by GFRI on green invention [

6]. Cui et al. underscored the pivotal role played by GFRI in shaping the energy consumption structure [

7]. Lastly, Chen et al. demonstrated that GFRI contributes to enterprises attaining higher ESG standards [

8]. These studies mainly focus on real-side adjustments triggered by the pilots, showing that GFRI can guide firms toward greener and more efficient activities, but they pay relatively little attention to firms’ financial allocation responses under the same policy shock. Our paper, therefore, complements this strand by examining whether GFRI also induces a shift in the financial margin, namely corporate financialization.

2.2. Factors Influencing CF

Existing scholarly work has extensively delved into the factors influencing corporate financialization, categorizing them into two groups. The first group is macroeconomic factors, encompassing elements such as economic growth, uncertainty in the economic environment, labor costs, interest rate levels, and government policies, among others [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. The other group focuses on micro-level factors, including credit financing, corporate social responsibility, profitability, corporate size and capital demand, profitability and financial status, governance structure, transparency, and more [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

In summary, while existing research has drawn meaningful conclusions regarding green finance policies and corporate financialization, it has not yet examined how China’s GFRI pilots, as a concrete green finance regime, may lead firms to adjust this financial margin. By treating financialization as a behavioral response under GFRI, this article links the GFRI literature with the corporate financialization literature and makes the mechanism more explicit.

This article aims to contribute in several ways: Firstly, in contrast to previous studies, it delves into how GFRI influences CF, which contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of its influence on micro-enterprise behavior. Secondly, by applying the “reservoir” theory and “investment substitution” theory, this study uniquely identifies the two primary motivations driving corporate financialization under a green finance policy, revealing the balance of the economic and environment goals of firms during decision-making processes. Thirdly, the article investigates the heterogeneity in the impact of GFRI across regions, industries, and enterprises, providing a rich foundation for improving and tailing the policies in each pilot zone and, thus, further improving green transformation and sustainable development.

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. GFRI’s Impact on Corporate Financialization

As a type of environmental regulation, the establishment of GFRI aims to accelerate the refinement of green development policies and top-level designs for green finance within the pilot regions. Environmental regulations could have a dual impact on corporate production decisions. On one side, compliance with environmental regulations adds to the cost burden, specifically in emission reduction and pollution control. This could drive companies to redirect their investments toward more profitable ventures in the short term. When firms encounter environmental regulations, they tend to diversify their investments, including increasing their financial investments, thereby elevating their financialization levels.

On the contrary, the “Porter hypothesis” posits that well-designed environmental policies can generate an innovation offset, thereby enhancing enterprise productivity, subsequently leading to economic gains [

22]. Pilot policy initiatives that establish a recording platform for corporate pollution and environmental violations augment the cost of environmental pollution for firms. This directly impinges on their profitability and financing capabilities. Consequently, firms are more inclined to invest in environmental improvements as a preventative measure. These investments aim to cut emissions, mitigate negative environmental externalities from production and operations, and lessen the need to expand capital through financial channels. Under such circumstances where enterprises have to assume greater environmental responsibilities and, consequently, incur additional expenses, their level of financialization may be constrained.

Therefore, we posit the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a:

GFRI can enhance corporate financialization.

Hypothesis 1b:

GFRI can suppress corporate financialization.

3.2. GFRI’s Impacts Under “Reservoir” Motivation

The impacts of the pilot implementation of GFRI on corporate financialization is driven by different motivations of the enterprises. We will explore the impacts of the implementation of GFRI on corporate financialization based on two motivations for financialization: “reservoir” motivation and profit maximization motivation.

According to the “reservoir” theory, preventing future cash flow uncertainty is a crucial reason for companies to increase financial investments. GFRI policy requires companies to increase environmental governance investments, raising compliance costs. This will undoubtedly increase operating costs for companies, bringing greater uncertainty to their future production and operations. Additionally, the implementation of pollution control and technological upgrades under the constraints of the pilot policies of GFRI will also generate significant short-term funding needs. Considering the fluctuation in expected future cash flows for companies caused by the policies of GFRI, companies, driven by “reservoir” motivation, are likely to increase the proportion of financial investments to cope with the cash flow volatility risks induced by policy changes.

Therefore, this paper posits the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

Facing liquidity risks introduced by GFRI, companies will enhance their level of financialization under the “reservoir” motivation.

3.3. GFRI’s Impact Under Profit Maximization Motivation

As per the “investment substitution” theory, the fundamental aspect of corporate financialization lies in the quest for maximizing profits. The variation in industry returns is a crucial factor that drives companies to prefer financial investments. The pilot policies of GFRI impose constraints on the financing of high-energy-consuming and high-polluting enterprises. Given these limitations, adhering to current production methods by companies would result in harm to their profits and a reduction in market competitiveness. In response, companies will increase green innovation investment to upgrade production processes and alleviate environmental policy pressures. Innovation investment is characterized by high costs, long-term nature, and uncertain returns, which may increase operating costs for companies, worsening the profitability of operation. In this scenario, companies, driven by profit maximization motivation, will prefer low-cost, high-return financial investments to ensure the realization of their short-term profit goals. Secondly, investment in innovation empowers companies to enhance production processes, elevate production efficiency, and mitigate long-term production costs. Consequently, this encourages an uptick in physical investment and a decrease in the share of financial investment. Both scenarios represent choices made by companies under the profit maximization motivation. The key to the difference in these choices lies in whether the pilot policies of GFRI can effectively enhance the profitability of companies.

Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3:

When innovations guided by GFRI fail to improve their economic performance, firms will increase financial investments under profit maximization motivation.

4. Models, Data, and Variables

4.1. Model

The existing literature predominantly employs Difference-in-Differences (DID) methodology for policy evaluation. DID aims to assess policy causal effects by comparing the pre- and post-treatment differences between the treatment and control groups, thereby mitigating endogeneity issues and yielding robust results. In this study, we examine whether the introduction of GFRI has an impact on the financialization of firms by using the DID model. We consider GFRI policy as a quasi-natural experiment, with listed companies in the five pilot provinces (regions) as the treatment group, and those in other provinces as the control group. The pilot policy was announcement in June 2017; therefore, the period before 2017 is considered pre-treatment, and from 2017 onwards is post-treatment. This design enables the identification of the policy’s net effect. The benchmark model is constructed as follows:

In Equation (1), the subscript denotes firms, and represents year. The dependent variable stands for the degree of financialization for firm in year . is a dummy variable for the pilot zones; is a dummy variable that indicates whether GFRI policy was implemented ( for , for ). is the interaction term that captures the policy’s impact on firm financialization. represents control variables for financialization; and are year and firm fixed effects, respectively; and is the random error term influenced by time variation.

4.2. Data

This study selected Chinese listed companies from the years 2012 to 2021. We excluded firms with missing data during the sample period; firms in the banking, securities, insurance, and other financial industries; firms that have been listed for less than 1 year; and firms that suffered severe losses (marked as ST or *ST) during the sample period. Ultimately, our study included 3351 firms, constituting 21,271 observations. The primary financial data, managerial characteristics, and green patent data used in this study were sourced from the CSMAR database. It should be noted, however, that firm-level data are available only for listed companies, so the results mainly reflect the behaviors of publicly traded firms in pilot areas and may not fully capture the responses of smaller or unlisted firms. To mitigate the impact of extreme values on the research findings, we apply winsorizing at the 1% and 99% levels for all continuous variables.

4.3. Variables

Corporate Financialization (CF): We refer to the research of Peng et al. to quantify the extent of financialization, which is characterized as the proportion of a company’s financial assets to its total assets [

11]. To be specific, financial assets encompass trading financial assets, net value of available-for-sale financial assets, derivative financial assets, net value of held-to-maturity investments, net value of long-term equity investments, and net value of investment properties.

Current ratio (Curr): The Curr is measured by the ratio of current assets to current liabilities of firms.

Return on equity (Roe): The Roe is measured by the ratio of net income to shareholders’ equity of firms.

Control variables: In accordance with the studies by Shi et al., the control variables selected include firm size, growth potential, leverage, return on assets, property rights, firm age, and ownership concentration [

23]. Specifically, firm size (Siz) is measured by the natural logarithm of total assets, growth potential (Gro) is measured by the growth rate of total assets, leverage (Lev) is measured by the ratio of total liabilities to total assets, return on assets (Roa) is measured by the ratio of net profit to total assets, firm age (Age) is measured by the age of the firm, ownership concentration (Top) is measured by the percentage of shares held by the largest shareholder, and property rights (Soe) is a dummy variable whose value is 1 for state-owned enterprises and 0 for non-state-owned enterprises.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Benchmark Results

We empirically test the effects of the implementation of GFRI on corporate financialization based on Equation (1).

Table 2 displays the findings. Initially, we include only the DID term, our core independent variable in our benchmark model, the result of which is displayed in column (1). Then, we include both industry and year fixed effects in our model, after which the firm-level control variables are also included, the results of which are shown in column (2) and column (3), respectively. Across all three columns, the coefficients of the DID term are consistently and significantly positive, indicating a substantial increase in the level of financialization among enterprises due to GFRI policy. This suggests that a policy intended to channel funds toward green activities may simultaneously induce firms to expand financial investments, an unintended effect that echoes findings in recent international studies on green finance and balance sheet adjustments.

5.2. Robustness Tests

5.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

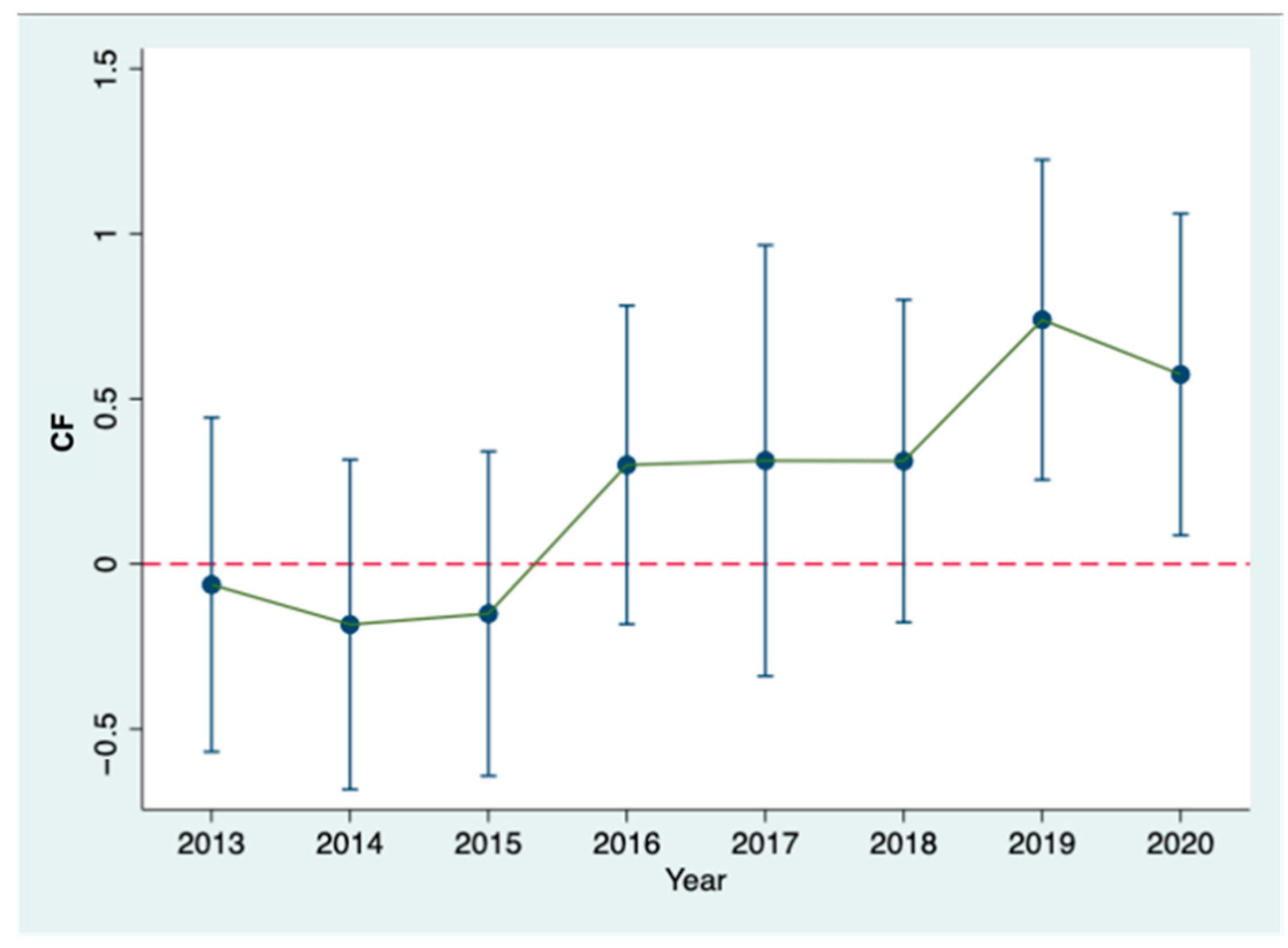

In the event that significant disparities in financialization levels were present between companies in the pilot zones and those in other regions prior to the policy enactment, the outcomes of our study could potentially be attributed to factors unrelated to the pilot zone policy. To ensure the premise of our DID model holds, we construct a parallel trend test on our treatment and control groups based on the following model.

In Equation (2),

is a dummy variable and t = 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020. If the year is 2014, then we set

to be 1, the other

to be 0, and all other

are set accordingly.

Figure 1 reports the regression results and shows that the DID coefficients in the four years prior to the policy are not statistically significant, indicating that the parallel trends assumption holds.

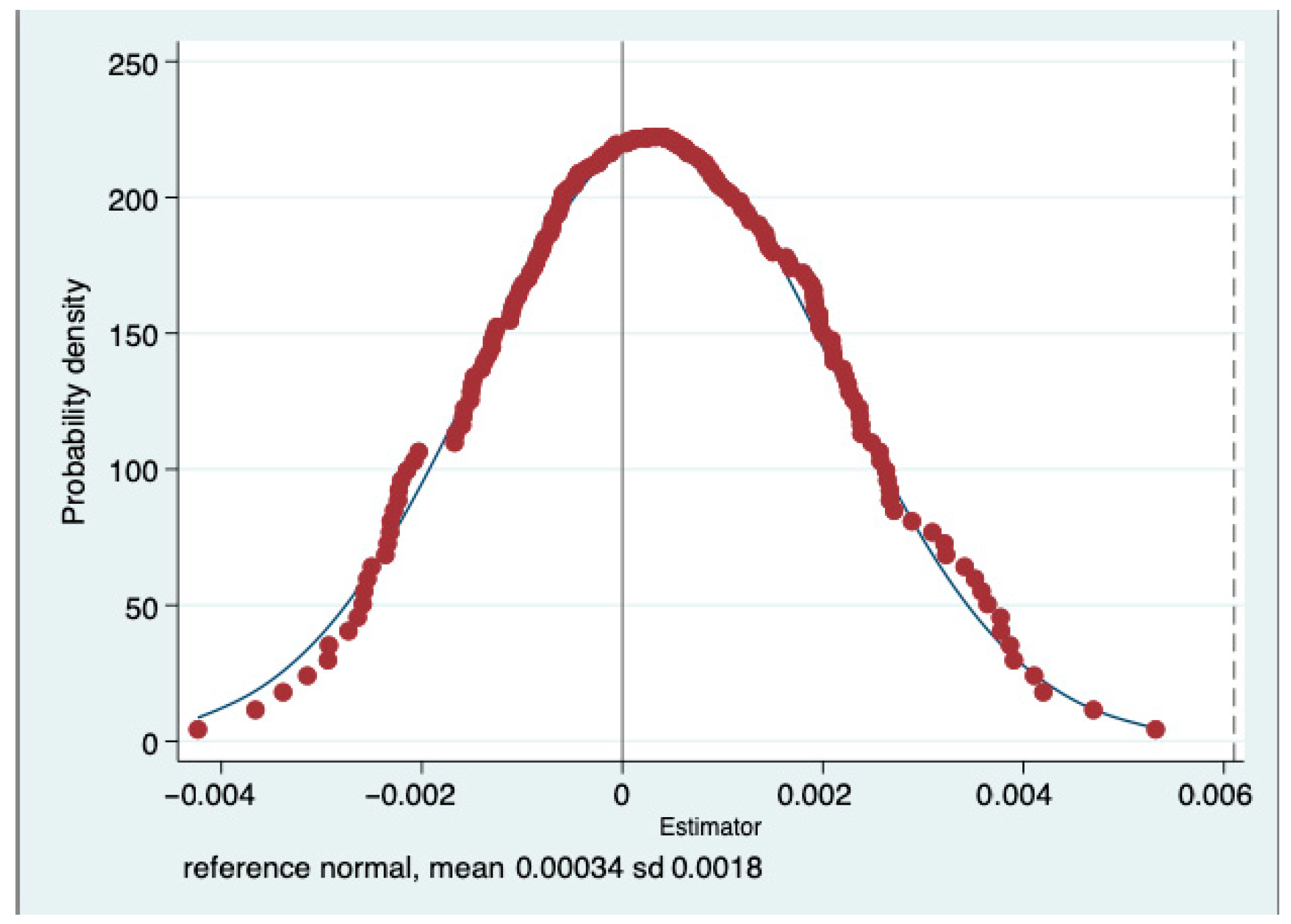

5.2.2. Placebo Test

To eliminate the concern that the increase in financialization is triggered by other random factors, instead of the pilot policy, we conducted a placebo test by simulating the randomized effect of GFRI on specific areas by generating a computer-randomized treatment group and running the benchmark model using the simulated treatment groups. This process was repeated 500 times, and we expected that the coefficient of the interruption term of randomized treatment group and post would not be significantly different to zero.

The result of the test is demonstrated in

Figure 2, which confirmed that there are no other random factors that trigger the increase in CF.

5.2.3. Redefine the Core Dependent Variable

To minimize the potential influence of measurement errors on our outcomes, we adopted an approach recommended by Song and Lu and modified the measurement of financialization [

24]. Specifically, we redefined financial assets to encompass the following eight accounting items: trading financial assets, net value of available-for-sale financial assets, derivative financial assets, net value of investments held to maturity, net value of long-term equity investments, net value of real estate investments, receivable dividends, and receivable interests. We then used the ratio of corporate financial assets to total assets as our redefined core dependent variable and reanalyzed using the benchmark model. The regression results are presented in column (1) of

Table 3, demonstrating that the coefficient of the DID term remains significantly positive.

5.2.4. Excluding the Effects of Environment Policies

In addition to the influence of GFRI, outcomes may be subject to interference from environment policies. China initiated carbon emission trading scheme pilot policies (ETSs) aimed at improving resource allocation efficiency through market trading, serving the objective of carbon emission reduction. The ETSs were implemented starting from 2013 in seven cities. Our model incorporates the interaction effects between the regions affected by the ETS and the policy implementation year (2013) (ETS × post). The results of the regression, depicted in column (2) of

Table 3, affirm that our findings remain consistent, even when excluding the effects of the ETSs.

5.2.5. Excluding the Effects of Other City-Level Policies

In 2008, the Innovative City Pilot (ICP) policy, involving a complex system of multiple innovation entities, was initiated, with Shenzhen being the first pilot. By 2020, our sample’s end year, 78 cities were included in the ICP. Additionally, China released a Low Carbon City Pilot (LCCP) policy that spanned 87 cities from 2010 to 2017. To mitigate potential disruptions from city-level policies, we incorporated interaction terms between city fixed effects and year fixed effects (City × year) into Equation (1). The regression outcomes, outlined in column (3) of

Table 3, affirm the persistence of our findings, demonstrating their validity, even when accounting for potential city-level policy interference.

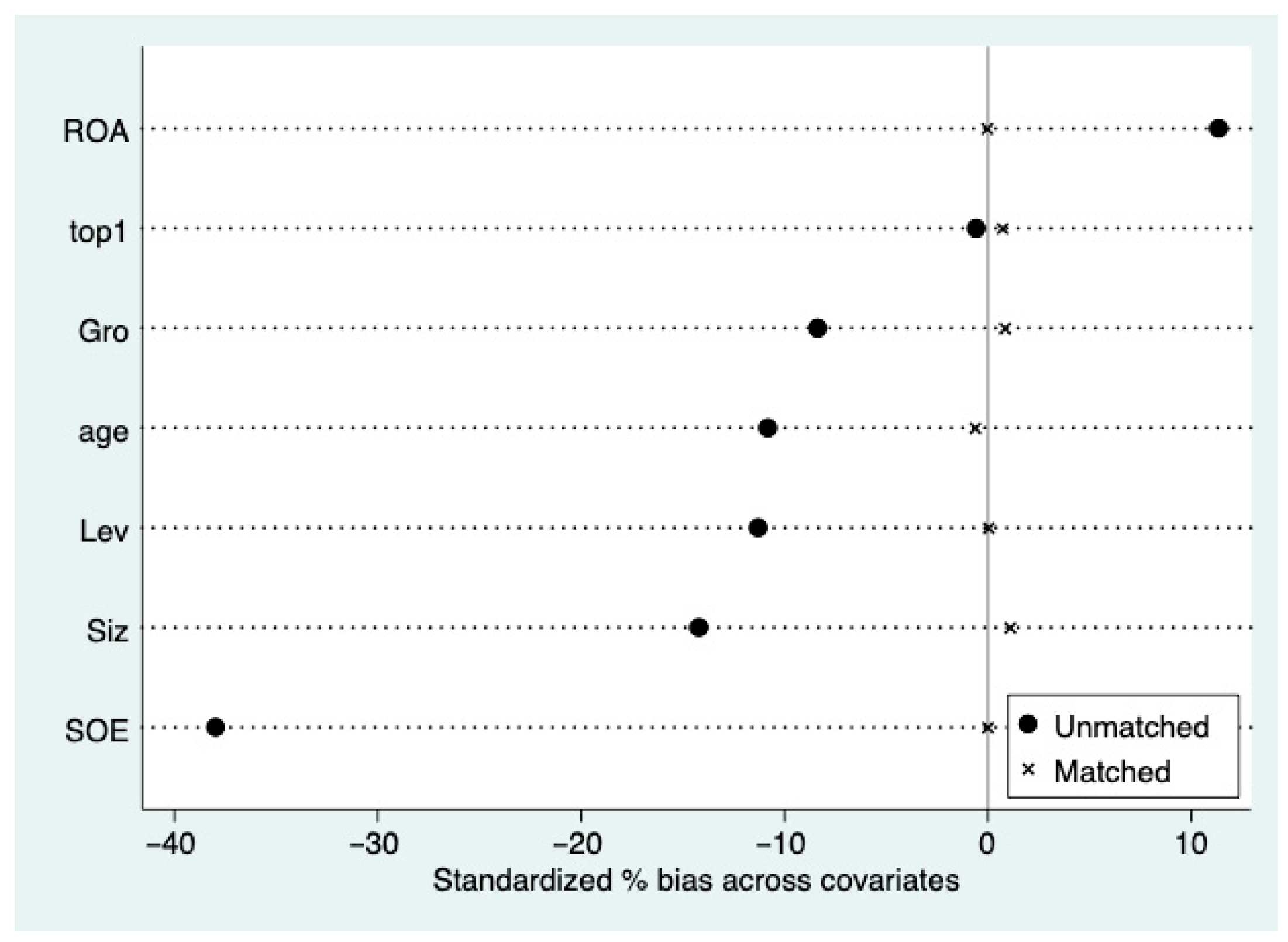

5.2.6. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)-DID Method and Sub-Sample Estimation

To mitigate potential sample selection bias, we employed the Propensity Score Matching (PSM)–Difference-in-Differences (DID) approach for robustness testing. Since our sample included 3351 firms over China, traditional DID may overlook initial group differences, impacting the present study’s accuracy, while PSM-DID mitigates this by aligning firms based on similarity scores, creating comparable groups. The process involves selecting control variables as identifiers for matching companies in the treatment and control groups. We employed a 1:2 nearest neighbor matching method, creating a refined sub-sample and conducting a benchmark model analysis using the matched sub-samples. The outcomes of this matching, as shown in

Figure 3, demonstrate significantly reduced disparities between the groups, affirming the feasibility and reasonableness of PSM-DID.

The result in column (4) of

Table 3, derived from the PSM-DID method, is aligned closely with our benchmark regression findings, affirming the persistence of our conclusions, even with the adoption of this alternative method.

6. Heterogeneity of Policy Effects and Mechanism Analysis

6.1. Heterogeneity Analysis

6.1.1. Heterogeneity of Geographic Locations

From the perspective of geography, given the varying geographical locations of different enterprises, the pilot policy’s impacts on corporate financialization could differ. In accordance with the classification standards established by the National Bureau of Statistics, China is categorized into the eastern and central–western regions. Firms located in the eastern region constitute the eastern sample, and those in the central–western region make up the central–western sample. We analyzed the influence of the policy on companies situated in the eastern and central–western regions, as presented in column (1) and column (2) of

Table 4.

The results show that the coefficient for the DID term is positive in column (1), while is not significant in column (2). This suggests that the impacts of the pilot policy are more pronounced on enterprises in the eastern region. This pattern is consistent with existing studies showing that eastern provinces have more developed financial and factor markets and stronger profit-oriented management [

23], which makes firms in these regions more responsive to changes in financial returns.

6.1.2. Heterogeneity of Property Rights

The pilot policy’s effects on corporate investment behavior may vary according to property rights. To validate the heterogeneous impacts of property rights, we separated two groups of our sample based on whether or not they are state-owned enterprises. We examine the policy impacts on Soes and non-Soes in column (3) and column (4) of

Table 4.

The results indicate that, in contrast to non-state-owned enterprises, the implementation of GFRI is unlikely to exert a significant influence on the financialization of state-owned enterprises. Facing the environmental pressure brought on by the pilot policies, companies anticipate significant risks to future cash flows due to environmental regulatory adjustments. In response to operational risks, companies tend to allocate more investments toward financial assets, thereby enhancing liquidity reserves. Conversely, state-owned enterprises benefit from soft budget constraints and implicit government guarantees, granting them greater access to fiscal subsidies and bank credit, subsequently leading to reduced financing constraints compared to their non-state-owned counterparts. Consequently, state-owned enterprises typically do not maintain substantial holdings of financial assets in the short term to address potential future cash flow risks.

6.1.3. Heterogeneity of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance

In the context of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) behaviors, companies with high ESG ratings may exhibit unique responses to the pilot policy compared to those with lower ESG scores. Referring to Sun et al., 2023 [

25], we assessed corporate environmental and social performance based on the environmental and social responsibility scores derived from the Hexun website’s corporate social responsibility reports. We then categorized the sample into two groups, namely low- and high-ESG groups, using the median ESG score as the threshold. The results of the pilot policy’s impacts on high-ESG-scored firms and low- ESG-scored firms are demonstrated in column (5) and column (6) of

Table 4.

The results of column (5) and column (6) in

Table 4 indicate that GFRI significantly impacts low-ESG-scored firms. This could be attributed to the fact that companies with lower ESG ratings may face more pressing financing constraints and operational costs in the context of GFRI compared to those with better ESG performance. Consequently, these firms might prioritize addressing liquidity risks and improving their financial stability. This focus on immediate financial concerns may lead them to seek more aggressive financialization strategies, or to invest in short-term financial assets as a means to mitigate these risks.

6.1.4. Heterogeneity of Executive Team’s Financial Background

The policy’s influences may differ due to the heterogeneity among executive teams. We divided the sample into the following two groups: one whose current executive teams include at least one member having a financial background (including past and present work experiences), and the other consisting of current executive teams with no members having a financial background. We examined the heterogeneity impacts on firms’ executive teams with and without financial backgrounds in column (7) and column (8) of

Table 4.

The results indicate that the policy does not significantly affect firms with financial background executive teams, but does impact those without. This could be attributed to the absence of a financial background indicating higher risk aversion, leading to an increase in liquidity reserves when confronted with financial uncertainty. In contrast, executive teams with a financial background often possess stronger risk management capabilities, potentially having more tools and strategies to hedge risks. Their deeper understanding of financial markets and instruments gives them greater confidence in addressing financial uncertainty.

6.2. Mechanism Analysis

The baseline regression outcomes presented above suggest a substantial increase in the degree of financialization within enterprises in the pilot zones following the implementation of GFRI policy. Our study verifies whether the pilot policy encourages enterprises to increase their financialization to mitigate future liquidity risks. The findings, presented in column (1) of

Table 5, reveal that the pilot policy leads to a reduction in the liquidity of enterprises and, thus, firms enhance CF in this case through “reservoir” motivation.

To investigate the second motivation driving the increase in CF, we first explore the effectiveness of GFRI, which is whether GFRI improved the green transformation of the firms within pilot zones and further examines the impacts on the economic performance of companies. We quantify corporate green innovation (GIN) using the number of green patent applications. Since firm-level monetary expenditures on green innovation are not consistently disclosed for all listed companies, GIN serves here as an observable proxy for firms’ green innovation efforts. The results, as shown in column (2) of

Table 5, confirm that the pilot policy has indeed stimulated green innovation in firms within the pilot zones, verifying the policy’s effectiveness. However, column (3) indicates that this green innovation response is not matched by an increase in profitability, so firms have an incentive to reallocate part of their resources to financial assets with relatively higher and more certain returns, which is consistent with the investment substitution channel.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study uses data from China’s listed companies and employs the DID method, along with a series of robustness tests, to empirically examine the influence of GFRI on corporate financialization. The research findings indicate three key outcomes. Firstly, the pilot policies have effectively elevated the level of corporate financialization. Second, the intensifying effect of GFRI on corporate financialization is particularly evident in the eastern region, non-state-owned enterprises, low-ESG-rated companies, and firms where the board and supervisory team lack a financial background. Third, from a mechanistic viewpoint, in response to the liquidity constraints imposed by the pilot policy, companies are inclined to boost their financial investments as a strategy to counterbalance liquidity risks, aligning with the “reservoir” motivation. Additionally, while the pilot policies affirmatively impact green innovation, this does not necessarily lead to enhanced profitability. In line with the “investment substitution” theory and driven by profit maximization motivations, firms tend to increase their investments in financial assets.

Based on these findings, this study suggests several policy implications. Firstly, there is a need to maintain a focus on the real economy while cautiously advancing the implementation of GFRI. This means that the green finance toolkit tested in the pilot zones does not only guide firms toward green activities, but can also trigger a shift in resources into financial assets, which is a point policymakers need to anticipate when promoting similar schemes outside the pilot areas. The government should bolster support for the real economy, preventing excessive corporate investments in the financial sector to align financial activities with real economic growth, thereby averting financial bubbles and systemic risks.

Secondly, differentiated policy implementation among various entities is crucial. In other words, firms with weaker ESG performance or weaker internal governance are more likely to respond to GFRI on the financial margin, so the policy effect is heterogeneous across firms, which suggests that future rollouts should impose stronger green investment requirements, or provide earmarked support for these firms, to ensure that financial resources are channeled to real green activities, rather than to financial asset accumulation. Customized policy measures should be developed based on the unique characteristics of different regions, industries, enterprises, and management teams, ensuring more effective and targeted policy execution.

Thirdly, alongside green finance, which primarily supports green projects, financial support should be actively promoted for the green transformation and innovation of high-energy-consuming and high-polluting enterprises, such as special loans and credit concessions, under the GFRI framework. These measures aim to alleviate cash flow issues during enterprise transformation, reduce green innovation cost pressures, expand income sources, and support sustainable development.

Finally, it should be emphasized that a sustained increase in corporate financialization, if not accompanied by corresponding growth in green and productive investment, may dilute the contribution of GFRI to China’s long-term green, low-carbon, and high-quality development targets. Policymakers, therefore, need to monitor this balance sheet response and prevent financialization from crowding out real green upgrading, so that the pilot remains consistent with the national carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Q.; Software, X.L.; Validation, X.L.; Formal analysis, C.Z.; Investigation, J.Z. and K.L.; Resources, S.Q., J.Z. and C.Z.; Data curation, S.Q., X.L. and K.L.; Writing—review & editing, C.Z.; Project administration, J.Z.; Funding acquisition, K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by the Hubei Natural Science Foundation (No. 2023AFB1114) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2042024kf0005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the partial support of Ningbo philosophy and Social Sciences Key Research Base “Research Base on Digital Economy Innovation and Linkage with Hub Free Trade Zones”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Qi, S.; Bo, Y.; Kai, L. An International Comparative Analysis on China’s Economic Growth and the Convergence in Energy Intensity Gap and Its Economic Mechanism. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2011, 9, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qi, S.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X. Green credit policy, government behavior and green innovation quality of enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Lin, S.; Cui, J. Can Environmental Rights Trading Markets Induce Green Innovation? Evidence from China’s Listed Companies’ Green Patent Data. Econ. Res. 2018, 53, 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Qi, S. Does green finance restrain corporate financialization? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 70661–70670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Mao, Z.; Ho, K.-C. Effect of green financial reform and innovation pilot zones on corporate investment efficiency. Energy Econ. 2022, 113, 106185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cheng, X.; Ma, Y. Research on the Impact of Green Finance Policy on Regional Green Innovation-Based on Evidence From the Pilot Zones for Green Finance Reform and Innovation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 896661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Mao, H.; Dong, X.; Shao, L.; Wang, M. Will green financial policy influence energy consumption structure? Evidence from pilot zones for green finance reform and innovation in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1216110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, L.; He, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D.; Wang, W. Green Financial Reform and Corporate ESG Performance in China: Empirical Evidence from the Green Financial Reform and Innovation Pilot Zone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, F. Financial liberalization, private investment and portfolio choice: Financialization of real sectors in emerging markets. J. Dev. Econ. 2009, 88, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.Y. Financial asset allocation, macroeconomic conditions and firm’s leverage. World Econ. 2018, 41, 148–173. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.C.; Han, X.; Li, J.J. Economic policy uncertainty and corporate financialization. China Ind. Econ. 2018, 1, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Du, P.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S. The minimum wage and the financialization of firms: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 76, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, H.J.; Dai, J.; Xu, C.H. Deregulation of interest rates, equalization of profit-rate, and enterprises’ shift from real to virtual. J. Financ. Res. 2019, 6, 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S.; Duan, B. Research on the impact of carbon trading policy on the financialization of enterprises. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 5, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bernanke, B.S.; Gertler, M. Inside the black box: The credit channel of monetary policy transmission. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliman, A.; Williams, S.D. Why ‘financialisation’ hasn’t depressed US productive investment. Camb. J. Econ. 2015, 39, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance; Zimmerli, W.C., Holzinger, M., Richter, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Fan, W.; Li, S.; Zhou, M. Impact of Surface Waves on the Steady Near-Surface Wind Profiles over the Ocean. Bound.-Layer Meteorol. 2015, 155, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Udell, G. The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. J. Bank. Financ. 1998, 22, 613–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Maksimovic, V. Financial and Legal Constraints to Growth: Does Firm Size Matter? J. Financ. 2005, 60, 137–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Maksimovic, V. Law, Finance, and Firm Growth. J. Financ. 1998, 53, 2107–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a New Conception of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, T. Does green financial policy affect debt-financing cost of heavy-polluting enterprises? An empirical evidence based on Chinese pilot zones for green finance reform and innovations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 179, 121678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lu, Y. U-shape Relationship between Non-Currency Financial Assets and Operating Profit: Evidence from Financialization of Chinese Listed Non-Financial Corporates. J. Financ. Res. 2015, 6, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhou, C.; Gan, Z. Green Finance Policy and ESG Performance: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Firms. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).