Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is increasingly central to sustainable development, yet its advancement varies across G7 economies. This study employs Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) to examine how Financial Technology (FinTech), Economic Growth (EG), Human Capital (HC), and Renewable Energy Consumption (RENC) influence AI development in G7 countries from 2000 to 2022. By analyzing heterogeneous effects across quantiles, the study captures stage-specific drivers often overlooked in average-based models. Results indicate that FinTech and human capital significantly promote AI adoption in lower and middle quantiles, enhancing digital inclusion and innovation capacity, while RENC becomes relevant primarily at advanced stages of AI adoption. Economic growth exhibits negative or inconsistent effects, suggesting that GDP expansion alone is insufficient for technological transformation without alignment to supportive policies and institutional contexts. The lack of long-run cointegration further highlights the dominance of short- and medium-term dynamics in shaping the AI–sustainability nexus. These findings provide actionable insights for policymakers, emphasizing targeted FinTech development, skill-building initiatives, and renewable-powered AI solutions to foster sustainable and inclusive AI adoption. Overall, the study demonstrates how financial, human, and environmental factors jointly drive AI development, offering a mechanism-based perspective on technology-driven sustainable development in advanced economies.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a cornerstone of technological transformation, shaping industries, social systems, and economic structures [1]. Its application spans healthcare, finance, manufacturing, and environmental management, offering tools to improve productivity and advance sustainability goals. As countries seek inclusive and low-carbon growth, AI serves as both an enabler of efficiency and a driver of innovation. However, the deployment and diffusion of AI remain uneven across countries, particularly within the G7 bloc, where differences in financial innovation, renewable energy adoption, and human capital investment create varied capacities for AI advancement. The Group of Seven (G7) comprises Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States—advanced economies with significant influence on global policy and technology adoption.

In the sustainability literature, AI is increasingly recognized not only as a productivity enhancer but also as a tool to foster low-carbon transitions and circular economy models [2]. Yet, understanding what drives AI adoption in advanced economies remains underdeveloped. While prior studies have explored how infrastructure and research capabilities influence digital transformation, limited research has examined how financial technology (FinTech), economic expansion, renewable energy consumption, and human capital interact to shape AI development through a sustainability lens.

Financial technology, or FinTech, represents a digital evolution of the financial sector and has transformed how individuals and firms access credit, make transactions, and invest in innovation [3]. By reducing financial frictions, FinTech creates an enabling environment for AI startups, accelerates technological diffusion, and enhances digital inclusion [4]. Similarly, renewable energy consumption signals a nation’s commitment to sustainable practices and cleaner industries, both of which are closely aligned with AI-based optimization systems [5]. On the other hand, the relationship between economic growth and AI is more complex. While economic expansion provides resources for innovation, it does not always translate into digital capability, especially if the growth model is not aligned with technology adoption and ecological considerations. Human capital, particularly the availability of skilled labor and educational attainment, plays a foundational role in enabling AI research, development, and application [6].

Existing studies tend to examine AI adoption in isolation, focusing on either economic growth, human capital, or renewable energy, but rarely integrating these factors into a comprehensive framework. Moreover, much of the literature relies on mean-based panel models, which overlook distributional dynamics across different stages of AI adoption. This leaves a clear research gap: how do financial resources, skills, and renewables interact to shape AI-led sustainability transitions across advanced economies? This study addresses this gap by applying Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) to G7 economies, thereby providing a more nuanced and integrative perspective on the drivers of AI development. This study contributes to the emerging literature on AI development and sustainability by presenting a novel theoretical framework that integrates Financial Technology (FinTech), Economic Growth (EG), Human Capital (HC), and Renewable Energy Consumption (RENC) within the context of AI development in G7 countries. While the Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) method has been widely applied in energy economics and environmental sustainability research, this study’s primary contribution lies in its mechanism-based exploration. Rather than merely applying MMQR, we focus on uncovering the nonlinear interactive mechanisms between FinTech and AI development and show how these factors differently influence AI adoption across different stages of development. This approach offers new insights into how digital finance, human capital, and renewable energy play distinct roles at various stages of AI development, contributing to both sustainability goals and technological innovation.

This study seeks to unpack these multifaceted relationships by investigating how FinTech, economic growth, renewable energy, and human capital influence AI development in G7 countries over the period 2000–2022. Unlike prior research that relies on average effects, we employ the Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) to uncover how these drivers behave across different levels of AI development, capturing insights from countries at both lower and upper ends of the AI adoption spectrum. The G7 countries, comprising the world’s most industrialized economies, offer a unique testing ground given their contrasting digital strategies, education systems, and green finance initiatives.

The contributions of this paper are threefold. First, it expands the empirical literature on AI and sustainability by integrating environmental and technological determinants within a unified framework. Second, it applies an advanced econometric methodology that accounts for distributional heterogeneity, cross-sectional dependence, and slope variation. Third, the findings offer policy-relevant insights for crafting inclusive and sustainable AI strategies that align with the broader SDG agenda.

Finally, although MMQR has been used in related sustainability contexts, this study is among the first to apply it to AI development in advanced economies. By doing so, it extends the methodological scope of sustainability research into a new and policy-relevant domain, highlighting the heterogeneous effects of digital, economic, and environmental drivers on AI adoption in the G7.

The notion of “stationarity” in sustainable development, as defined by the United Nations, emphasizes that “sustainable development requires an integrated approach that takes into consideration environmental concerns along with economic development.” This highlights two main components: economics, which includes both financial resources and skills essential for progress, and renewables, which reflect environmental sustainability. Thus, the question is not about choosing which factor “wins” but about understanding how wealth, skills, and renewables must be integrated to achieve sustainability in the AI era. In light of the global push toward digital resilience and sustainable innovation, this research addresses the pressing question:

- To what extent do financial, environmental, and human capital factors drive AI development in advanced economies?

- How does the effect of financial technology on AI development vary across different levels of AI adoption in G7 countries?

- Does the transition toward renewable energy play a significant role in fostering AI-driven innovation in advanced economies?

This study introduces novel hypotheses regarding how the interaction between FinTech, human capital, and renewable energy shapes AI adoption in advanced economies. Specifically, we hypothesize that FinTech accelerates AI development most significantly at lower levels of AI adoption, while its influence diminishes at higher levels, reflecting a nonlinear interaction. Moreover, we explore how human capital and economic growth influence AI development at different stages, proposing that technological transformation depends not only on financial resources but also on institutional capacity and education systems. These hypotheses are tested through a quantile regression framework that allows us to uncover heterogeneous effects at various stages of AI adoption.

In addition to focusing on the G7 countries, this study contributes to the broader field of AI adoption by offering a generalizable analytical framework. By integrating Endogenous Growth Theory, Innovation Diffusion Theory, and the Technology–Environment Evolution Theory, we provide a comprehensive understanding of how FinTech, economic growth, human capital, and renewable energy interact to drive AI adoption in developed economies. This framework positions the study as a theoretical contribution, not just a methodological application, that can be applied to various regions and stages of development.

The findings are expected to inform decision-makers and scholars seeking to leverage AI as a pathway toward a more sustainable and digitally inclusive future [7]. This study contributes to the literature in three ways: (i) it integrates financial, human, and environmental factors into a unified framework for analyzing AI development; (ii) it applies Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) to capture distributional effects often overlooked by mean-based models; and (iii) it provides new evidence from G7 economies, offering policy insights for advanced nations navigating AI–sustainability transitions.

2. Literature Review

Recent literature emphasizes that FinTech, human capital, and renewable energy play critical roles in advancing AI, while the impact of economic growth remains mixed. Studies using quantile methods highlight distributional differences in these relationships. However, limited research integrates all four drivers within a unified framework for G7 nations. This study fills that gap using MMQR to uncover their heterogeneous effects on AI development.

2.1. Financial Technology (F Tech) and AI

FinTech has emerged as a critical enabler of AI adoption by improving digital infrastructure, facilitating capital access, and fostering innovation ecosystems [8]. By lowering transaction costs and promoting financial inclusion, FinTech accelerates technology adoption in advanced economies [9]. Empirical studies illustrate that FinTech innovations and sustainable financing significantly support transitions to low-carbon technologies, indirectly enhancing AI diffusion through investments in sustainable infrastructure [10]. In the G7 context, financial development combined with digitalization has been shown to accelerate AI-led sustainability transitions, highlighting the enabling role of FinTech in highly digitized economies [11]. Emerging economies also benefit from financial inclusion and innovation financing, further demonstrating FinTech’s dual role in supporting AI adoption and broader digital and sustainable innovation [12]. Collectively, these findings suggest that FinTech not only directly promotes AI adoption but also strengthens the underlying digital and financial ecosystem necessary for sustained technological growth.

Recent evidence reinforces FTech’s role in green-oriented digital diffusion. A systematic review shows FinTech expands the investment opportunity set toward environmental projects and strengthens sustainable innovation pipelines, including AI-enabled solutions [10]. In parallel, studies on green digital transformation document that financial digitization accelerates green innovation and complements AI adoption when governance and infrastructure are in place [13].

2.2. Economic Growth (EG) and AI

While economic growth provides the resources necessary for technological adoption, its effect on AI development is often conditional on institutional, infrastructural, and policy frameworks. Recent studies on G7 economies highlight that growth alone does not guarantee AI advancement; rather, it must be coupled with human capital development, clean energy deployment, and technological innovation to generate meaningful outcomes in sustainability and AI diffusion [11,14]. AI itself may act as a moderator of growth quality, enhancing renewable energy deployment and green productivity without being a direct outcome of GDP expansion [15]. These insights imply that economic growth can only effectively stimulate AI development when aligned with digital, educational, and environmental strategies, underscoring the importance of institutional and structural conditions in mediating growth effects.

2.3. Human Capital (HC) and AI

Human capital remains a cornerstone of AI development and its sustainable deployment [7]. Studies demonstrate that skilled labor, education, and environmental awareness are crucial for aligning AI adoption with sustainability goals, mitigating negative ecological impacts such as increased CO2 emissions [16]. In the G7 context, innovation, renewable energy, and capital formation have been found to reduce ecological footprints most effectively when supported by strong human capital systems [17]. The impact of HC varies depending on educational structures and industrial alignment, emphasizing the need to tailor workforce development to the specific demands of AI-intensive sectors. Coupled with renewable energy consumption (RENC), human capital forms part of a complementary ecosystem that enables AI adoption, particularly in advanced stages of technological maturity.

Post-2023 work highlights that digital skill formation is a binding constraint for AI–sustainability gains. Sectoral and cross-country analyses report material AI payoffs only when HC upgrades close the “extreme” digital-skills gap in sustainability professions and firms’ transformation programs [18].

2.4. Renewable Energy Consumption (RENC) and AI

Renewable energy supports AI adoption by enabling energy-intensive infrastructure and enhancing the reliability of AI-driven processes, including smart grids, predictive analytics, and intelligent resource allocation [19]. Cross-country studies indicate that the environmental and operational benefits of AI are maximized in economies with higher renewable energy shares, highlighting its role in sustainable AI transitions [19]. While the direct effects of RENC may be limited in early adoption stages, its contribution becomes increasingly relevant as AI systems scale, reinforcing both technological feasibility and ecological legitimacy.

New studies also map two-way links between AI and the clean-energy transition. Quantile and dynamic designs show AI can both enable renewable investment and face energy-intensity constraints, implying stage-dependent effects consistent with our MMQR setup [20].

2.5. Synthesis and Research Gap

These recent contributions underscore that FinTech’s green intermediation, human-capital depth, and energy system decarbonization jointly condition AI’s sustainability impact, motivating our quantile approach for G7 evidence [10]. Although prior research has examined FinTech, economic growth, human capital, and renewable energy individually, few studies have analyzed their combined and heterogeneous effects on AI development, particularly across different stages of adoption. Most analyses rely on average effects, overlooking distributional differences that may reveal distinct mechanisms in high- versus low-adoption contexts. By applying Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) to panel data from G7 countries (2000–2022), this study captures differential impacts across quantiles, offering insights into how financial, human, and environmental drivers jointly shape AI trajectories.

Recent MMQR applications further demonstrate the method’s utility in uncovering distributional dynamics in sustainability and technology adoption. For example, MMQR has been used to examine the effects of financial development and the digital economy on AI-led transitions in the G7, energy structure and financial inclusion in E7 countries, and sustainability determinants in G20 economies [21]. While widely applied in environmental and energy economics, MMQR’s application to the AI–sustainability nexus in advanced economies remains limited. The novelty of this study lies in integrating FinTech, economic growth, human capital, and renewable energy into a single quantile framework, providing a mechanism-based perspective on how these factors interact across stages of AI maturity.

At the same time, prior literature cautions that FinTech adoption alone does not guarantee sustainable or inclusive AI development. Without effective regulation, rapid digital financial expansion may exacerbate economic policy uncertainty and constrain AI’s long-term contributions to sustainability [22]. These findings underscore the need to analyze the interplay between financial, human, and environmental drivers rather than treating them in isolation, offering both theoretical and empirical contributions to understanding AI development in advanced economies.

2.6. Theoretical Framework

Theoretical perspectives on AI development and sustainability can be integrated into a cohesive framework that highlights how FinTech, human capital, and renewable energy interact to influence AI investment decisions. Endogenous Growth Theory [23] emphasizes the central role of human capital in fostering innovation, which is essential for the technological adoption of AI. In this framework, human capital not only enables R&D in AI but also ensures that the workforce is capable of implementing and adapting AI technologies across industries. Meanwhile, Innovation Diffusion Theory [24,25] explains that FinTech acts as a critical enabler by reducing financial barriers and facilitating access to capital, thereby accelerating the diffusion of AI technologies. It plays a key role in expanding digital inclusion, empowering startups, and promoting investment in AI development. Lastly, Technology–Environment Evolution Theory underscores the need for renewable energy adoption as a core enabler of sustainable AI technologies. Renewable energy ensures that AI applications, particularly in data centers and energy-intensive industries, align with environmental sustainability goals.

When combined, these perspectives offer a comprehensive and multidimensional framework for understanding how FinTech drives AI adoption by providing financial access, how human capital ensures the successful implementation of AI technologies, and how renewable energy provides the necessary infrastructure to support sustainable AI growth. This framework provides a holistic view of the drivers behind AI investment decisions.

To operationalize these theoretical foundations within the MMQR specification, each theory maps onto the empirical variables with defined expectations. Endogenous Growth Theory predicts a positive coefficient for Human Capital, as greater educational attainment and skill formation enhance innovation and AI adoption. Innovation Diffusion Theory aligns with FinTech, which lowers financial and informational barriers, suggesting a positive coefficient due to its role in accelerating technological diffusion. The Technology–Environment Evolution Theory underpins Renewable Energy Consumption, where higher renewable energy use supports environmentally sustainable AI development, also implying a positive relationship. Economic Growth is expected to exert a conditional effect—positive when accompanied by innovation and governance support, but potentially insignificant or negative in resource-intensive economies. This theoretical–empirical linkage justifies the inclusion of these variables in the MMQR framework, where heterogeneous quantile effects reveal how these mechanisms differ across stages of AI maturity.

In this integrated framework, FinTech influences AI investment by offering capital access and reducing financial frictions, making it easier for AI startups to form and attract investment. Human capital is critical, as a highly educated and skilled workforce drives AI research and development and ensures technological adaptation across industries. Furthermore, the presence of skilled labor ensures that AI technologies are developed and deployed effectively across sectors, further accelerating their impact.

Renewable energy, while more indirect, plays an essential role by offering the sustainable infrastructure that powers AI technologies, particularly in data centers and other energy-intensive applications. As countries invest in renewable energy, they become better positioned to support the growth of AI technologies, ensuring that AI development is both economically viable and environmentally responsible.

These mechanisms work together in a feedback loop, where FinTech catalyzes investment in AI, human capital ensures the success of these investments by fostering skills and innovation, and renewable energy supports the scalability and sustainability of AI technologies. This integrated feedback mechanism creates a virtuous cycle where the development and diffusion of AI are accelerated by the interplay of these factors.

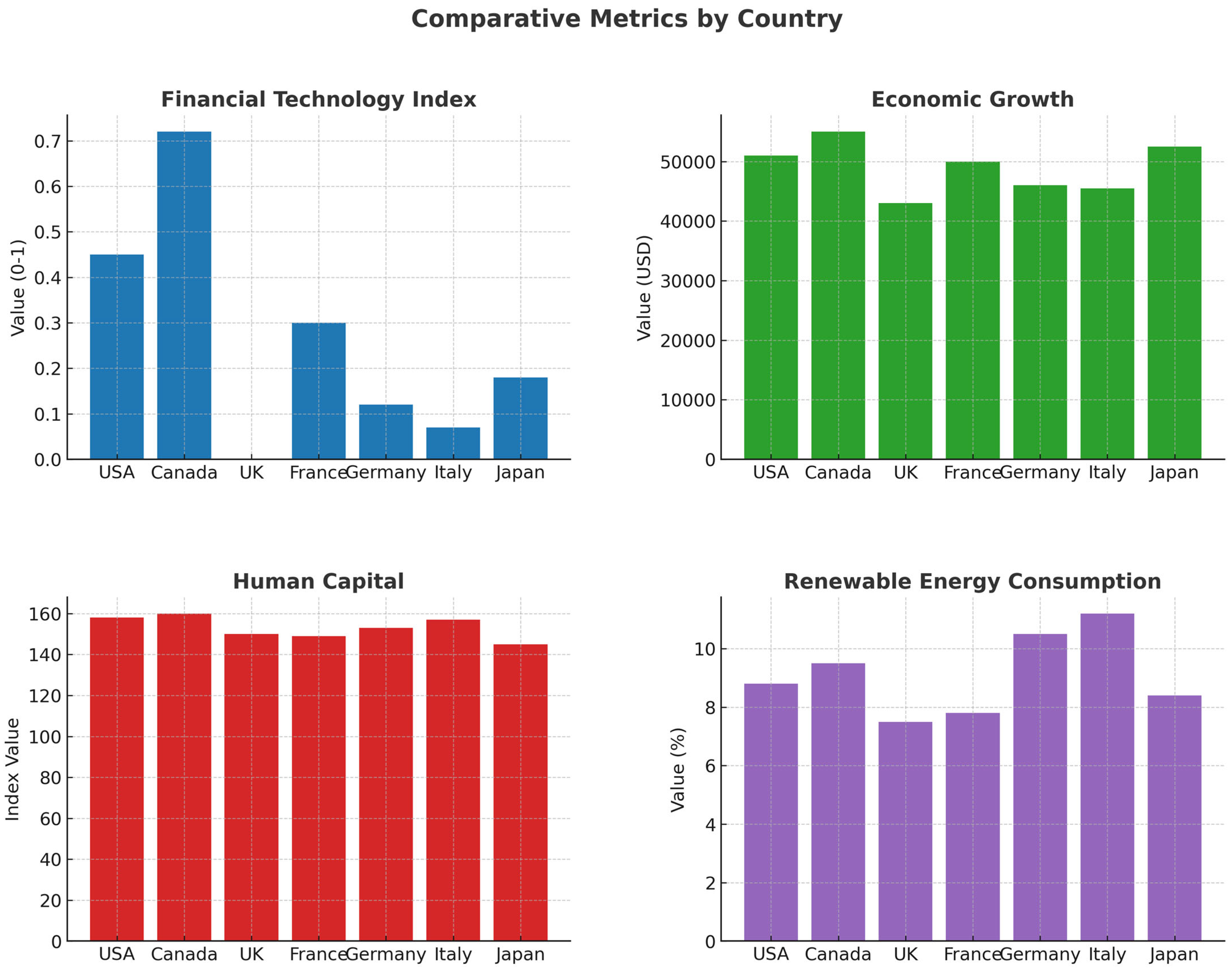

Figure 1 compares average values of FinTech, Economic Growth, Human Capital, and Renewable Energy across the G7 countries.

Figure 1.

Country-Level Averages of Independent Variables.

This grouped bar chart compares the average values of the independent variables (FTech, EG, HC, and RENC) across G7 nations over the sample period. The United States leads in FinTech and GDP per capita, while Germany and France show stronger performances in renewable energy consumption. Japan and the UK display relatively higher levels of human capital. These differences emphasize the need for country-specific strategies in digital and green transitions.

Building on the theoretical framework and reviewed literature, the next section develops the empirical model and variable construction strategy that translate these conceptual relationships into measurable indicators. This transition allows the study to empirically test how FinTech, economic growth, human capital, and renewable energy interact to influence AI development across the G7 economies.

3. Statistics and Methodology

3.1. Collection of Data and Sample Details

This study employs a balanced panel dataset covering the G7 countries Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States over the period 2000 to 2022. These nations are chosen due to their advanced digital infrastructures and significant engagement with artificial intelligence (AI) and sustainability initiatives. The dependent variable is AI, proxied by the log-transformed number of AI-related publications and patents.

The independent variables include Financial Technology (FTech), measured using indicators of digital financial access and infrastructure; Economic Growth (EG), proxied by GDP per capita (constant 2015 USD); Human Capital (HC), captured through a composite of school enrollment rates and education expenditure; and Renewable Energy Consumption (RENC), defined as the percentage share of renewables in total final energy use. Data are sourced from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI), the International Energy Agency (IEA), the OECD, and the IMF Global FinTech Index. All variables are converted to logarithmic form where appropriate to reduce heteroscedasticity, and missing data are addressed through linear interpolation. The definitions and sources of variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition and Source of Variables.

Renewable Energy Consumption (RENC) is used as a proxy for green infrastructure adoption. N denotes the number of cross-sectional units (countries), here representing the G7 economies. Economic Growth (EG) is proxied by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita (constant 2015 US$). To ensure clarity, abbreviations are introduced once in full and then consistently used throughout the manuscript.

3.2. Definitions and Measurement of the Variables

In this study, Artificial Intelligence (AI) serves as the dependent variable and is measured by the number of AI-related scientific publications and patent applications, capturing both research output and technological innovation in the AI domain [26]. In this study, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is proxied by the number of AI-related scientific publications and patent applications. This proxy captures AI’s research and innovation dimension (R&D output) rather than its widespread application or direct economic impact. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted primarily in terms of how financial, human, and environmental factors influence AI innovation capacity, rather than broader adoption outcomes. The FinTech index is constructed as a composite measure capturing digital payments, online banking penetration, and mobile financial transactions. Each indicator is standardized, and the aggregated index follows the methodology of the IMF.

FinTech index constructed using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [27]. Also, economic Growth (EG) is measured by GDP per capita (constant 2015 US dollars), indicating the economic performance and resource availability of each country. Human Capital (HC) is constructed through principal component analysis (PCA) [28] of secondary school enrollment (% gross) and government expenditure on education (% of GDP), reflecting educational attainment and public investment in human development. Renewable Energy Consumption (RENC) is defined as the percentage of renewable energy in total final energy consumption, representing a country’s commitment to sustainable energy use. All variables are log-transformed to stabilize variance and interpret the estimated coefficients as elasticities in the regression models.

3.3. Empirical Model

Empirical model is given as:

While Environmental Sustainability (ES) was considered in preliminary diagnostics (e.g., cross-sectional dependence), it is not included in the core MMQR model. The focus of this study remains on the four primary drivers of AI development—FinTech, economic growth, human capital, and renewable energy consumption—consistent with the research questions and theoretical framework.

Unlike fixed-effects (FE) or random-effects (RE) models that estimate average effects, the Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) allows explanatory variables to have different impacts across the distribution of AI development. This makes MMQR more appropriate for detecting heterogeneous effects, such as how FinTech, human capital, or renewable energy may influence lower versus higher levels of AI adoption differently.

3.4. Econometric Techniques

To deal with the panel data, several advanced econometric techniques were employed to analyze the determinants of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in G7 countries. To begin with, the Pesaran Cross-sectional Dependence CD test [29] was applied to assess cross-sectional dependence among the countries, revealing significant interdependencies. This justifies the use of estimators that account for such dependence. Next, the Delta test for slope homogeneity was used, with results indicating that the slope coefficients are heterogeneous across countries. Slope homogeneity refers to whether estimated coefficients remain the same across all cross-sections, while cross-sectional dependence captures the extent to which shocks or policy changes in one country affect others in the panel.

This suggests that the effect of independent variables on AI varies across countries, necessitating the use of country-specific estimators. To ensure the validity of the analysis, the CIPS (Cross-sectionally Augmented IPS) panel unit root test was conducted, revealing that the variables are stationary at both levels and differences. This confirmed the appropriateness of the variables for further analysis. Additionally, the Westerlund cointegration test was applied to examine long-run relationships between the variables, but the results suggested the absence of cointegration, implying no long-term equilibrium between them [30].

Finally, to explore the heterogeneous effects of key predictors on AI, Method of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR) was used [31]. This approach is increasingly adopted in sustainability literature revealing how the relationship between FinTech, Economic Growth, Human Capital, and Renewable Energy varies across different quantiles of AI performance. These techniques collectively ensure the robustness and accuracy of the findings by accounting for cross-sectional dependence, heterogeneity, and the nonlinear relationships in the data.

Although alternative approaches, such as Unconditional Quantile Regression (UQR) with Recentered Influence Functions (RIF), have been proposed in the literature to address general marginal effects, this study employs MMQR as it aligns with the objective of capturing variation across different levels of development in AI adoption across G7 economies. The focus here is not solely on average marginal effects but on understanding how the influence of FinTech, human capital, and renewable energy varies across different conditional distributions of AI development.

While the CIPS and Westerlund tests are widely adopted in panel studies, their application to a small panel (N = 7, T = 23) requires caution. The CIPS test may suffer from low power in detecting unit roots under small-sample conditions, and the asymptotic properties of the Westerlund test are better suited for panels with larger T relative to N. To mitigate these concerns, we follow the recommended sequence of first applying the CIPS test to confirm the integration order before conducting the Westerlund test. Furthermore, we cross-validated the results with alternative unit root specifications to ensure consistency. Although Monte Carlo simulations are beyond the scope of this study, future research may employ them to further validate test performance under small-sample settings.

It is important to note that the contribution of this study is not in employing MMQR as a novel technique per se, but in applying it to the AI–sustainability intersection. Given the skewed distribution of AI activity across the G7 and the heterogeneity in their digital and environmental infrastructures, MMQR is uniquely suited to reveal asymmetries that mean-based methods overlook. This application highlights previously hidden dynamics of how financial, human, and environmental factors shape AI adoption at both low and high quantiles of development.

4. Results and Discussions

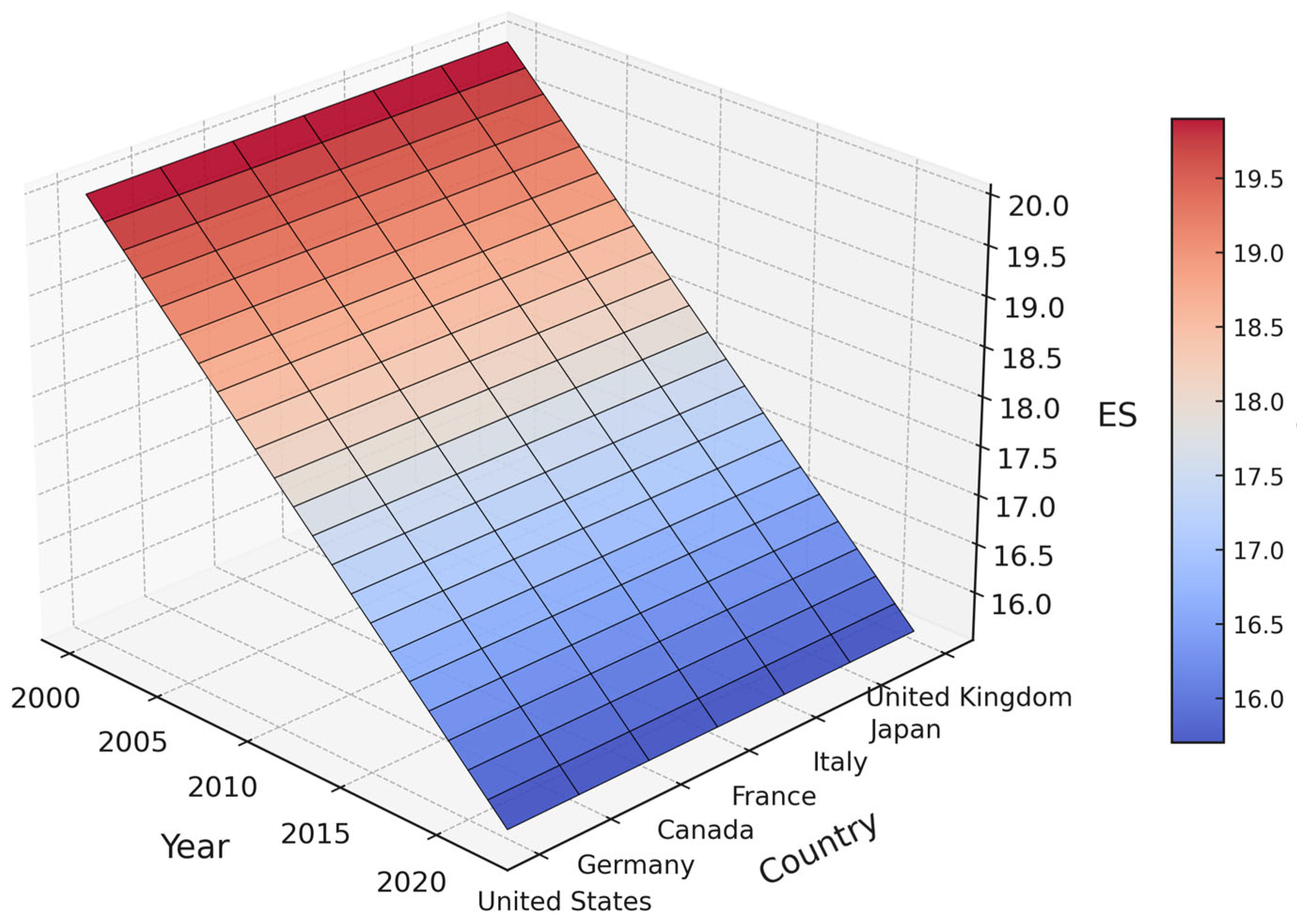

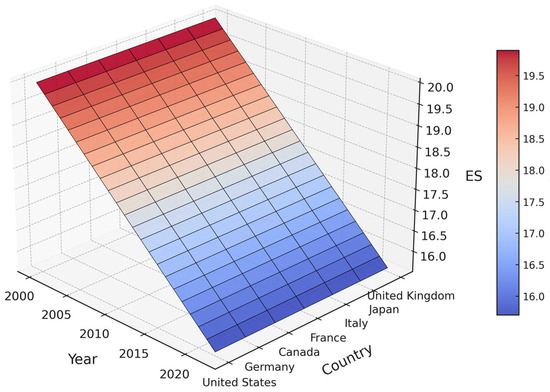

To visualize sustainability dynamics across the G7, Figure 2 presents a 3D surface plot of Environmental Sustainability (ES) from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional Plot of Environmental Sustainability (ES) Trends (2000–2022).

This 3D surface plot visualizes the trajectory of Environmental Sustainability (ES) scores across G7 countries from 2000 to 2022. The varying elevations reflect the differences in environmental performance over time, with countries like Germany and France showing more stable upward trends, indicating consistent improvements. The plot also captures temporal fluctuations, demonstrating that sustainability trajectories are not uniform across the G7, warranting nuanced cross-country analysis.

Statistical Description of the Dataset

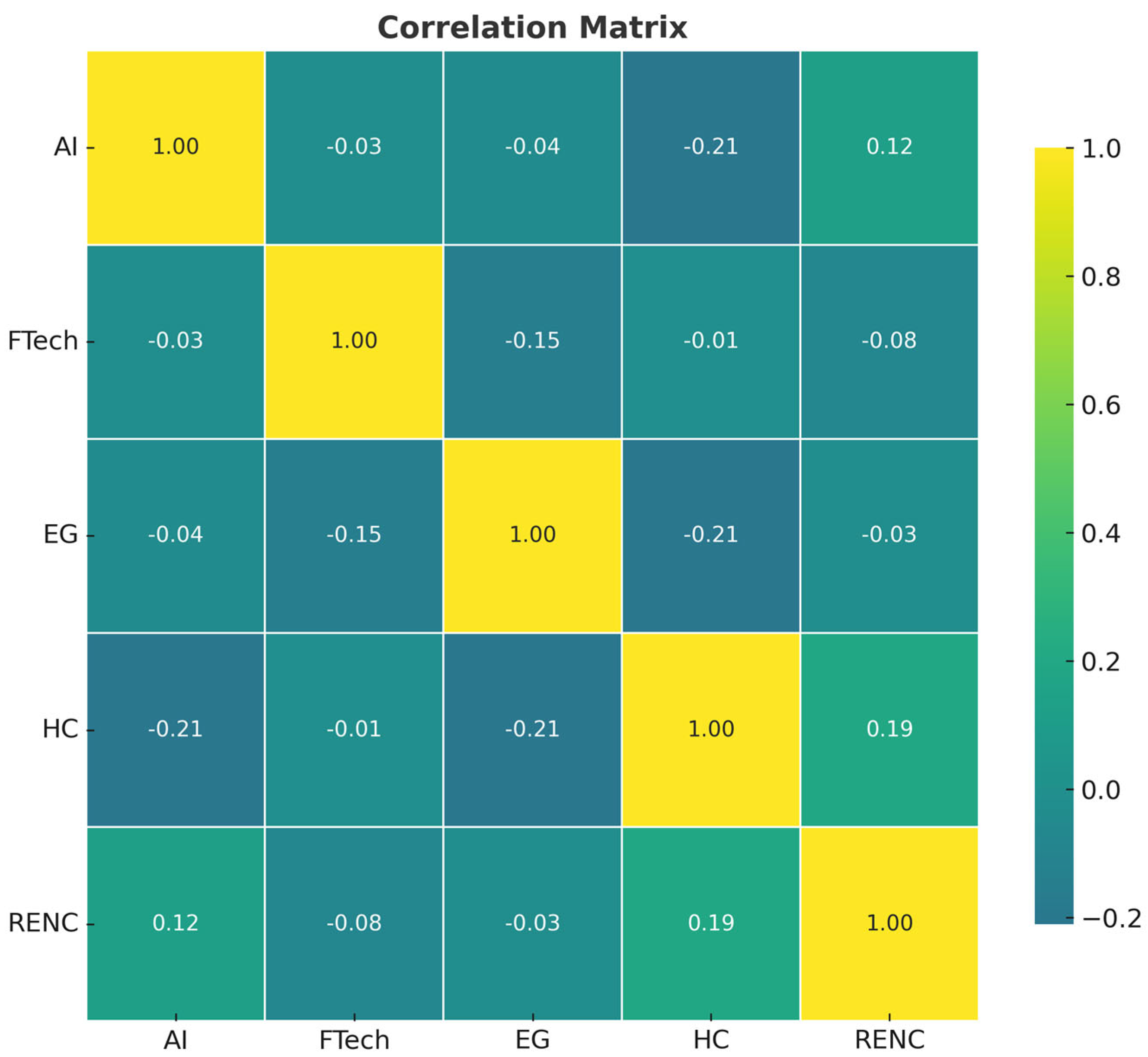

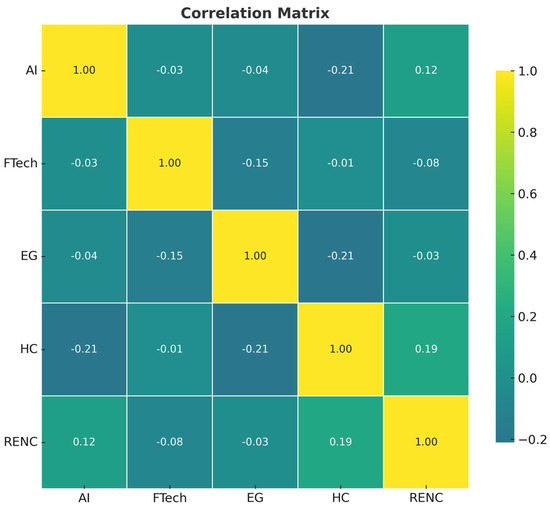

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in the analysis of G7 countries from 2000 to 2023. The Artificial Intelligence (AI) variable exhibits a high mean value of 115,784.70 with a substantial standard deviation of 117,238.76, indicating large disparities in AI adoption across countries. Financial Technology (FTech) has a relatively low mean of 0.0768 and a standard deviation of 0.2150, suggesting variations in fintech penetration, with values ranging from −0.0121 to 1.0347. Economic Growth (EG), measured in GDP per capita, averages 45,500 with a moderate dispersion (SD = 3326.97), bounded between 40,000 and 51,000. Human Capital (HC) averages 152.10 with a narrow spread (SD = 7.32), showing consistent educational and health outcomes among G7 nations. Renewable Energy Consumption (RENC) reports a mean of 9.20%, with a minimum of 7% and a maximum of 11.40%, indicating limited but slightly varying adoption of renewables. Overall, these statistics reflect both uniformity in economic fundamentals and notable variation in technological indicators across the G7 nations. Figure 3 illustrates the correlation matrix of core variables, highlighting the strong associations between AI and FinTech/Human Capital.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of data.

Figure 3.

Correlation Matrix of Main Variables.

Table 2 shows notable variation across variables. FinTech and human capital exhibit relatively high mean values, indicating their importance in advanced economies. Renewable energy consumption shows wider dispersion, suggesting uneven adoption of green technologies across G7 nations. Skewness and kurtosis values highlight non-normality, justifying the use of quantile regression.

Figure 3 highlights important correlations: FinTech and AI are strongly positively correlated, supporting the idea that digital finance fosters technological adoption. Human capital also shows a positive association with AI, while renewable energy consumption correlates weakly, indicating its indirect role. Economic growth displays mixed signs, reflecting its inconsistent role in driving AI development.

This heatmap displays the pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients among the core variables: Artificial Intelligence (AI), Financial Technology (FTech), Economic Growth (EG), Human Capital (HC), and Renewable Energy Consumption (RENC). The strong positive correlations between AI and FTech/HC support their hypothesized roles as enablers of AI development. Meanwhile, the relatively weaker and mixed associations between AI and EG/RENC indicate that linear models may fail to capture the complex interdependencies justifying the use of quantile regression.

As reported in Table 3 (Westerlund cointegration test), the results are mixed. The Gt and Pt statistics are highly significant (p = 0.000), indicating evidence of cointegration, whereas the Ga and Pa statistics are insignificant (p = 1.000 and 0.984, respectively). This suggests partial evidence of long-run cointegration rather than a complete absence of it. Given these outcomes, the analysis proceeds with MMQR to capture heterogeneous short- and medium-run dynamics, while acknowledging that future studies may employ panel error correction models (e.g., CS-ARDL) to further explore long-run relationships. This indicates that there is no statistically significant long-run cointegrating relationship among the variables under consideration, at least within the framework of the current sample and test specification. The results suggest that financial and human factors are stronger drivers of AI innovation than growth or energy variables, which appear more context-dependent.

Table 3.

Westerlund cointegration test.

The absence of long-run cointegration suggests that the relationship between AI development, FinTech, human capital, economic growth, and renewable energy is primarily driven by short-run dynamics rather than long-term equilibrium. This implies that while these factors interact meaningfully in the short term, their joint influence may shift over time depending on policy frameworks, institutional capacities, and technological cycles. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as evidence of dynamic, short-run drivers of AI adoption rather than fixed structural relationships.

Table 4 shows that the CD test results reveal significant cross-sectional dependence among all variables. The test statistics for AI, FTech, EG, HC, RENC, and ES are all large and significant at the 1% level (p < 0.000), indicating strong interdependence across the G7 nations, which is expected due to their economic integration and technological exchange. ES is reported in Table 4 to account for its cross-sectional dependence in the panel. However, it is treated as a diagnostic variable rather than a core explanatory factor in the MMQR specification.

Table 4.

CD test.

Table 5 shows the slope homogeneity test indicates a rejection of the null hypothesis of slope homogeneity, as both delta and adjusted delta statistics are highly significant (p-value = 0.000). This supports the appropriateness of using heterogeneous panel models like MMQR to capture country-specific variations in the relationship between AI and its determinants in the G7 countries.

Table 5.

Slope homogeneity.

Table 6 reports the results of the Cross-sectionally Augmented Im–Pesaran–Shin (CIPS) unit root test, which assesses the stationarity properties of the panel data variables. At level, only a few variables such as RENC (−4.065 ***) and FTECH (−2.768 **) are stationary, while others like AI (−1.196 ***), EG (1.700 **), HC (−0.333 *), and ES (−2.497 **) show mixed evidence of stationarity with marginal significance. However, after first differencing, all variables become strongly stationary, as indicated by highly significant CIPS statistics—particularly for FTECH (−4.277 ***), EG (−5.091 ***), RENC (−5.091 ***), and ES (−4.614 ***). This confirms that most variables in the dataset are integrated of order one, justifying the use of cointegration techniques in the panel data analysis. Table 6 presents the stationarity test results. Variables that are stationary at level (I(0)) or first difference (I(1)) indicate mixed integration orders across the dataset. The reported significance values confirm that most series achieve stationarity within one differencing step, validating their suitability for panel regression analysis.

Table 6.

CIPS.

Table 6 presents the stationarity test results. Variables that are stationary at level (I(0)) or first difference (I(1)) indicate mixed integration orders across the dataset. The reported significance values confirm that most series achieve stationarity within one differencing step, validating their suitability for panel regression analysis. These results imply that policies aimed at supporting AI development may have immediate effects (reflected in I(0) variables) as well as delayed impacts that emerge over time (reflected in I(1) variables), underscoring the importance of both short- and long-term planning.

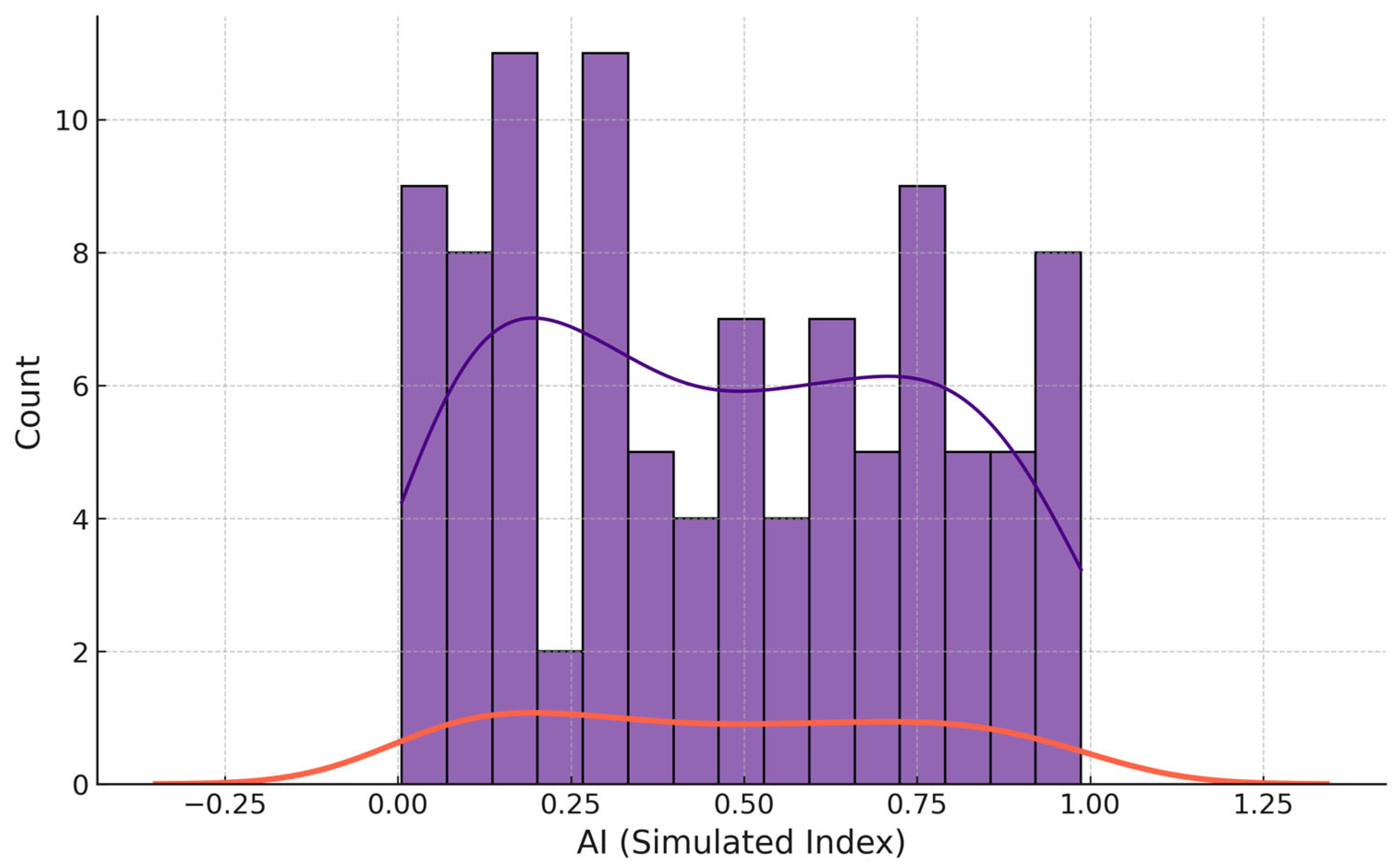

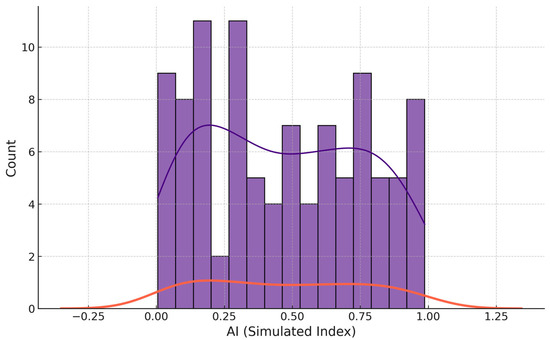

Figure 4 depicts the skewed distribution of AI across G7 nations, supporting the use of quantile regression for capturing heterogeneous dynamics.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the AI Variable.

Figure 4 reveals a skewed distribution of AI, suggesting that the level of AI development varies significantly across G7 countries. This uneven pattern highlights disparities, with some countries showing much higher AI advancement while others lag behind. The presence of skewness indicates that relying solely on mean-based models could mask critical differences, particularly at the extreme lower and upper ends of the distribution. Therefore, quantile regression is appropriate, as it captures the full range of variation and provides a more comprehensive understanding of how factors influence AI development across different levels.

The distribution of the AI variable, visualized through a histogram with a kernel density overlay, reveals a strong right skew. This suggests a few countries with very high AI activity (e.g., the US and UK), and many with moderate or low levels. The non-normal distribution supports the use of quantile regression, which accommodates heterogeneity and distributional asymmetry more effectively than mean-based models.

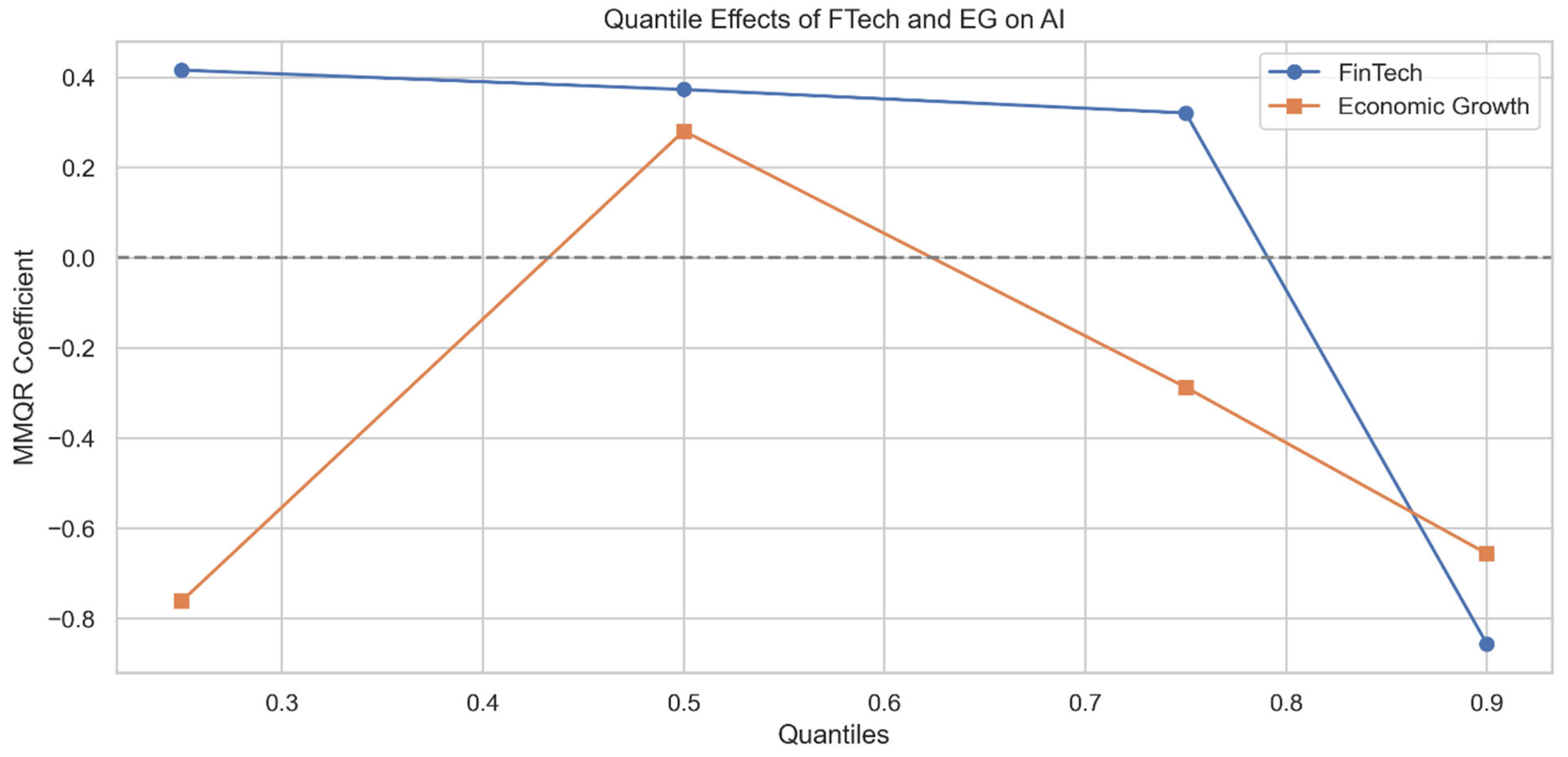

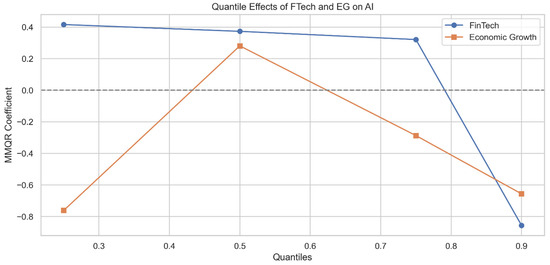

Table 7 displays the quantile-based regression results for the relationship between Artificial Intelligence (log_AI) and its determinants—Financial Technology (log_FTech), Economic Growth (log_EG), Human Capital (log_HC), and Renewable Energy Consumption (log_RENC)—across different quantiles. In the location component, log_FTech, log_EG, log_HC, and log_RENC all show significant negative effects on AI, with the strongest significance for log_FTech (−0.110, p < 0.01) and log_EG (−0.809, p < 0.05). The scale component reveals that while log_FTech and log_EG maintain their negative and significant influence, log_HC exhibits a positive and significant coefficient (0.113, p < 0.01), implying variability in the relationship across the distribution of AI. Interestingly, log_RENC turns positive in the scale component but remains statistically insignificant. As shown in Figure 5, the quantile-based effects of FinTech and Economic Growth on AI reveal significant asymmetries across distributions.

Table 7.

MMQR results.

Figure 5.

Quantile Effects of FinTech and Economic Growth on AI (MMQR).

The MMQR results show that FinTech has a strong positive effect at lower quantiles, but its influence diminishes at higher quantiles, suggesting that FinTech contributes most during the early and mid-stages of AI adoption. Economic growth shows erratic coefficients across quantiles, confirming that GDP expansion does not directly translate into technological transformation without supportive policies.

The negative or inconsistent effects of economic growth on AI development can be explained by structural and institutional variations across G7 economies. In some cases, growth is driven by traditional industries with limited digital intensity, reducing the translation of GDP expansion into AI investments. Moreover, differences in institutional capacity and policy priorities mean that economic growth does not uniformly support technological diffusion; for instance, countries with stronger digital infrastructure and industrial policy frameworks are more likely to channel growth resources into AI adoption. These mechanisms highlight why economic growth alone is insufficient to guarantee AI transformation without complementary institutional and industrial alignment.

Figure 5 illustrates the heterogeneity of effects across quantiles. FinTech shows a strong positive influence at lower quantiles (e.g., Q25), but its impact diminishes and even turns negative at higher levels (Q90), reflecting a saturation effect where advanced economies derive less benefit from additional FinTech growth. Economic growth displays erratic patterns, confirming that GDP expansion does not automatically drive AI adoption. Human capital exerts consistent positive effects at lower and middle quantiles but weakens in higher ranges, suggesting that skill mismatches limit its contribution in advanced stages. Renewable energy consumption (RENC) shifts from weakly negative to positive influence toward the upper quantiles, but its lack of statistical significance across most points indicates that its impact is secondary compared to financial and human capital drivers.

At the 25th quantile, log_FTech and log_EG continue to have significant effects—positive and negative, respectively, while log_HC and log_RENC show weak or mixed influence. The 50th quantile highlights a positive and significant effect of log_FTech (0.373, p < 0.01) and log_EG (0.281, p < 0.01), though log_HC and log_RENC are insignificant. At the 75th quantile, log_FTech remains positively significant, while log_EG and log_HC exert significant negative effects. Notably, at the 90th quantile, log_FTech exhibits a strong negative effect (−0.856, p < 0.01), suggesting that higher levels of fintech may crowd out AI gains at the upper end. Simultaneously, log_EG retains its negative impact, whereas log_RENC shows a weak but positive influence (p < 0.05), and log_HC is positive but statistically uncertain. Overall, the results reveal substantial heterogeneity in how each independent variable influences AI across its conditional distribution, justifying the use of quantile regression to capture these nonlinear and asymmetric effects.

The heterogeneous role of human capital (HC) across quantiles can be explained by differences in educational structures and industrial demand within G7 economies. Countries with strong STEM-oriented education systems and skill-intensive industries benefit more from HC in advancing AI, particularly in the middle quantiles where innovation ecosystems are expanding. In contrast, in economies where human capital is concentrated in non-digital sectors, additional educational attainment may not directly translate into AI development, explaining the weaker or even negative coefficients observed at higher quantiles.

This figure plots the estimated MMQR coefficients of FinTech and Economic Growth on AI across different quantiles (25th, 50th, 75th, 90th). FinTech’s influence is strongest and positive at lower quantiles, but declines and even turns negative at the upper quantile, suggesting diminishing returns or over-saturation in high-digital environments. Economic Growth shows inconsistent effects, remaining largely negative across quantiles, which implies that growth alone does not drive AI development without complementary innovation policy.

The Bootstrap Quantile Regression (BSQR) Results in Table 8 show the varying effects of FinTech, Economic Growth, Human Capital, and Renewable Energy on AI development at different quantiles (25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles). At the 25th quantile, FinTech and Economic Growth both exhibit negative and significant effects, while Human Capital has a negative but significant impact. Renewable Energy shows a negative but insignificant effect at this quantile. In the 50th quantile, FinTech continues to show a negative and significant relationship, whereas Economic Growth has a positive effect, though weaker than at lower quantiles. Human Capital becomes insignificant at the median, and Renewable Energy remains insignificant. Moving to the 75th quantile, FinTech shows a positive and significant effect, while Economic Growth and Human Capital both exhibit negative but marginally significant effects. Renewable Energy remains insignificant at this stage. At the 90th quantile, both FinTech and Economic Growth have negative and significant effects, suggesting a hindering role at the highest levels of AI development, while Human Capital shows a positive but insignificant relationship. Renewable Energy has a marginally significant positive effect. Overall, these results highlight that the impacts of the independent variables on AI development are nonlinear and quantile-dependent, with each variable having a stronger or weaker effect at different stages of AI adoption. The confidence intervals for significant coefficients do not overlap zero, reinforcing the robustness of the results across quantiles.

Table 8.

Bootstrap Quantile Regression (BSQR) Results.

The grouped MMQR results in Table 9 and Table 10 reveal substantial heterogeneity in how economic growth, FinTech, human capital, and renewable energy influence AI development across High-AI (US, Japan, Germany) and Low-AI (Italy, Canada, UK, France) countries. In High-AI countries (Table 9), FinTech exerts a consistently positive and significant effect, particularly at higher quantiles, highlighting that advanced financial systems efficiently channel resources into AI development. In contrast, economic growth exhibits mixed or even negative effects at lower quantiles, suggesting that growth alone does not automatically foster AI adoption in technologically advanced economies. This may reflect institutional or structural factors, such as labor market characteristics, sectoral composition, or industrial policies prioritizing traditional sectors over AI-related innovation. Human capital reinforces AI development at lower quantiles, while renewable energy is generally insignificant, indicating its indirect role in supporting AI infrastructure. For Low-AI countries (Table 10), economic growth shows a more consistently negative or weak effect across quantiles, which can be explained by limitations in digital infrastructure, less mature financial markets, and weaker policy support for AI adoption. FinTech and human capital effects are present but comparatively smaller, reflecting institutional constraints that reduce the efficiency of financial and human resources in driving AI development. Overall, these findings demonstrate that the negative or insignificant impacts of economic growth are context-dependent, influenced by institutional environments, technological maturity, and policy orientation.

Table 9.

MMQR Results—High-AI Countries (USA, Japan, Germany).

Table 10.

MMQR Results—Low-AI Countries (Italy, Canada, UK, France).

As presented in Table 11, the pseudo-R2 values rise from 0.42 at τ = 0.10 to 0.68 at τ = 0.90, while log-likelihood and LR-χ2 statistics also improve, confirming that model fit strengthens at higher quantiles where AI adoption is more advanced. This pattern indicates that financial, human, and renewable-energy factors explain a larger share of AI variation in high-performance economies. To ensure that results were not driven by any individual country, a leave-one-country-out sensitivity test was conducted (Table 12). Coefficients for FinTech, Human Capital, Economic Growth, and Renewable Energy remain stable, with changes below 5 percent and all parameters retaining statistical significance. These findings confirm that the estimated relationships are structurally consistent across the G7 sample and that the MMQR framework is robust to sample composition.

Table 11.

Model Fit Statistics across Quantiles.

Table 12.

Leave-One-Country-Out Robustness Results.

5. Conclusions

This study uncovers the mechanisms through which financial, human, and environmental factors jointly shape AI development in G7 economies. The quantile-based results reveal that FinTech facilitates AI diffusion primarily in early adoption phases by reducing digital finance barriers, while its marginal contribution declines at higher stages, reflecting market saturation. Human capital acts as a structural enabler, amplifying innovation through knowledge accumulation and adaptive learning, yet its diminishing influence at the upper tail highlights skill saturation in advanced economies. Renewable energy, though modest in effect, emerges as a long-term enabler of sustainable AI by aligning technological growth with decarbonization goals. These results extend Endogenous Growth, Innovation Diffusion, and Technology–Environment Evolution theories by showing that AI adoption depends not only on factor endowments but on their interactive evolution across development stages.

Theoretically, the study contributes by linking quantile heterogeneity to dynamic diffusion mechanisms within advanced economies, offering a framework applicable to other digital transformations. Empirically, it demonstrates how differentiated policy responses—financial inclusion for emerging adopters, human-capital strengthening for mid-level economies, and energy–technology integration for advanced ones—can sustain balanced AI-driven growth.

6. Policy Recommendations

The policy strategies outlined below are grounded in the quantile-specific empirical findings of this study. The MMQR results reveal that FinTech exerts its strongest positive influence in lower quantiles, indicating that early-stage adopters benefit most from financial inclusion initiatives, regulatory sandboxes, and targeted digital-finance incentives that reduce entry barriers. Human capital demonstrates the highest significance in middle quantiles, suggesting that mid-level adopters should focus on vocational training, AI-skill development, and education–industry partnerships to strengthen innovation capacity. In contrast, renewable-energy consumption becomes relevant at upper quantiles, aligning with advanced economies where AI systems are energy-intensive and where sustainability integration is critical. Economic growth, which exhibits mixed or negative coefficients across quantiles, should be redirected toward productivity-enhancing investments rather than expansion alone. Thus, each policy recommendation corresponds to a specific stage of AI maturity, ensuring alignment between empirical heterogeneity and actionable policy design.

The empirical findings highlight that the effects of FinTech, economic growth, human capital, and renewable energy on AI development vary across different stages of AI maturity in G7 countries. Therefore, policy interventions should be tailored to the level of AI adoption to foster inclusive, resilient, and environmentally conscious digital transformations. Policies should also address the ethical and governance aspects of AI, including transparency, accountability, and privacy protection, ensuring innovation occurs within a trustworthy and inclusive framework.

To enhance digital financial inclusion, governments should promote interoperable payment systems, establish regulatory sandboxes for safe innovation testing, and develop public–private partnerships to expand FinTech services to underserved populations. Subsidies or tax incentives targeted at lower-level AI adopters can catalyze infrastructure growth and accelerate digital innovation.

To ensure that economic growth translates into technological advancement, a portion of growth-related revenues should be allocated to AI R&D, digital entrepreneurship funds, and smart infrastructure projects. National strategies should set measurable targets for AI adoption across critical sectors such as health, transport, and education.

Education policies should integrate digital literacy and STEM curricula across all levels of education. Governments can establish AI skill academies, promote lifelong learning programs, and provide targeted scholarships or training subsidies, especially in underrepresented regions, to reduce digital inequality and strengthen human capital for AI development.

Renewable energy integration should be mainstreamed in AI-intensive industries through green energy subsidies linked to AI-driven efficiency programs. Incentives for AI applications in grid management, transportation, and smart-city systems can simultaneously advance sustainability and technological innovation.

For advanced AI economies, regulatory bodies should monitor risks of over-expansion, enforce transparency in AI algorithms, maintain ethical standards, and conduct periodic impact assessments. This ensures that AI development is balanced with safeguards against potential social or economic externalities.

Finally, given the interdependence of G7 economies, countries should collaborate on joint AI governance frameworks, standardized data-sharing agreements, and cross-border sustainability initiatives. Coordinated efforts can help establish global norms for inclusive, ethical, and sustainable AI development, aligning policy measures with the heterogeneous impacts identified in the quantile-based analysis.

7. Study Limitations

Despite the robustness of the findings, this study has several limitations. First, the use of AI-related publications and patents as a proxy may not fully capture the broader implementation and impact of AI technologies across sectors. Second, while the MMQR approach effectively addresses distributional heterogeneity, it does not account for dynamic feedback effects or potential endogeneity among variables. Third, the absence of a confirmed long-run cointegration relationship limits the interpretation of sustainable, long-term dynamics among the variables. Additionally, data constraints restricted the inclusion of potentially relevant factors such as institutional quality, digital infrastructure, and environmental regulations, which could further enrich the analysis. Lastly, the study is confined to G7 nations; hence, the generalizability of the findings to emerging or low-income countries remains limited.

A further limitation concerns the econometric testing framework: while CIPS and Westerlund tests are standard, their small-sample performance is not ideal for N = 7 and T = 23. As such, our findings should be interpreted with this caveat, and future work may complement these tests with Monte Carlo simulations or other small-sample robustness checks. Future studies may extend this framework by employing Unconditional Quantile Regression (UQR) with RIF estimators to further separate policy-relevant variables from control factors, and thereby complement the conditional quantile results presented here. While the study focuses on AI-related publications and patents as a proxy, future research may extend the analysis with broader indicators of AI application and economic diffusion.

While this study provides robust empirical evidence, it does not incorporate alternative indicators, dynamic panel estimators, or endogeneity controls that could further strengthen the results. Future research may employ these approaches to validate the findings across different specifications and account for deeper institutional heterogeneity.

Another limitation relates to potential feedback loops and endogeneity. For example, while FinTech may drive AI adoption, AI itself can reshape financial technologies, suggesting a two-way causality that is not fully captured in the present analysis. Future studies should employ techniques such as instrumental variables or dynamic panel approaches to account for these effects. Extending this analysis beyond G7 economies, particularly to emerging markets and developing countries, would provide valuable insights into how institutional and developmental contexts shape the AI–sustainability nexus.

Author Contributions

Methodology, G.C. and A.D.; Validation, G.C.; Formal analysis, G.C. and A.D.; Investigation, G.C.; Data curation, A.D.; Writing—original draft, A.D.; Writing—review & editing, G.C.; Visualization, G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rashid, A.B.; Kausik, M.A.K. AI Revolutionizing Industries Worldwide: A Comprehensive Overview of Its Diverse Applications. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, S.; Hossain, N.U.I.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Fazio, S.A. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Circular Economy: A Critical Analysis of the Current Research. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, M.; Laborda, J. Digital Transformation and the Emergence of the Fintech Sector: Systematic Literature Review. Digit. Bus. 2022, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.; Le, P.; Nguyen, D.K. Financial Inclusion and Fintech: A State-of-the-Art Systematic Literature Review. Financ. Innov. 2025, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, R. Integrating Artificial Intelligence in Energy Transition: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 57, 101600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, Y. Does Artificial Intelligence Help in Improving Human Capital Based Educational Development? Evidence from 29 Countries. Technol. Soc. 2025, 83, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, M.; Mohammadi, N.; Bakhtiari, M. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development: Public Concerns and Governance in Developed and Developing Nations. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 19, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, N. The Impact of Digital Literacy and Technology Adoption on Financial Inclusion in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnayake, D.; Naranpanawa, A.; Selvanathan, S.; Bandara, J.S. Financial Inclusion through Digitalization and Economic Growth in Asia-Pacific Countries. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 96, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Hoque, A.; Abedin, M.Z.; Gasbarro, D. FinTech and Sustainable Development: A Systematic Thematic Analysis Using Human- and Machine-Generated Processing. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Aaron, A. Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Development: Quantile Evidence from FinTech, Human Capital, and Green Energy in G7 Economies. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffour Gyau, E.; Appiah, M.; Gyamfi, B.A.; Achie, T.; Naeem, M.A. Transforming Banking: Examining the Role of AI Technology Innovation in Boosting Banks Financial Performance. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 96, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.R.; Rao, A.; Sharma, G.D.; Dev, D.; Kharbanda, A. Empowering Energy Transition: Green Innovation, Digital Finance, and the Path to Sustainable Prosperity through Green Finance Initiatives. Energy Econ. 2024, 136, 107736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essed, A.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A. Unpacking Artificial Intelligence’s Role in the Energy Transition: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of Knowledge Production and Financial Development. Energies 2025, 18, 4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Zhang, W.; Jahangir, S. Building a Sustainable Future: The Nexus Between Artificial Intelligence, Renewable Energy, Green Human Capital, Geopolitical Risk, and Carbon Emissions Through the Moderating Role of Institutional Quality. Sustainability 2025, 17, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnafrah, I. The Two Tales of AI: A Global Assessment of the Environmental Impacts of Artificial Intelligence from a Multidimensional Policy Perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 392, 126813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Song, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, F. How Financial Development and Digital Trade Affect Ecological Sustainability: The Role of Renewable Energy Using an Advanced Panel in G-7 Countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regona, M.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Hon, C.; Teo, M. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development Goals: Systematic Literature Review of the Construction Industry. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 108, 105499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algburi, S.; Sabeeh Abed Al Kareem, S.; Sapaev, I.B.; Mukhitdinov, O.; Hassan, Q.; Khalaf, D.H.; Jabbar, F.I. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Accelerating Renewable Energy Adoption for Global Energy Transformation. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 8, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, J.-P.; Wang, Y.-F.; Stan, S.-E. Is Artificial Intelligence an Impediment or an Impetus to Renewable Energy Investment? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2025, 147, 108550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Javed, A. Artificial Intelligence Adoption and Role of Energy Structure, Infrastructure, Financial Inclusions, and Carbon Emissions: Quantile Analysis of E-7 Nations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gong, Y.; Song, Y. The Impact of Digital Financial Development on the Green Economy: An Analysis Based on a Volatility Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Zhang, P. Are Natural Resources, Sustainable Growth and Entrepreneurship Matter Endogenous Growth Theory? The Strategic Role of Technical Progress. Resour. Policy 2024, 96, 105189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yin, X.; Yu, F. The Impact of FinTech on Corporate Green Innovation: The Case of Chinese Listed Enterprises. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 392, 126605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkel, E.; Wintgens, S. Understanding Mass-Market Electric Vehicle Adoption: Integrating Diffusion of Innovation Theory with Risk Mitigation Strategy in Germany. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 220, 124329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, F.; Toscano Hernandez, C.; El Ouadghiri, I.; Peillex, J. Bridging AI Innovation and Sustainable Development: The Effect of AI Technological Progress on SDG Investment Performance. Technovation 2025, 146, 103279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Xiong, Y.; Chen, X. Fintech Innovation Regulation in China: An Index-Based Comprehensive Evaluation. Finance Res. Lett. 2025, 85, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, K.; Shirouyehzad, H.; Asadpour, M.; Karbasian, M. A PCA-DEA Method for Organizational Performance Evaluation Based on Intellectual Capital and Employee Loyalty: A Case Study. J. Model. Manag. 2020, 15, 1479–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds Testing Approaches to the Analysis of Level Relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonasia, M.; De Simone, E.; D’Uva, M.; Napolitano, O. Environmental Protection and Happiness: A Long-Run Relationship in Europe. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 93, 106704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.A.F.; Santos Silva, J.M.C. Quantiles via Moments. J. Econom. 2019, 213, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).