Abstract

Urban areas are growing, often at the expense of native ecosystems. As a result, indigenous lands (ILs) have become critical refuges for biodiversity, essential for sustainability and sit at the intersection of cultural, economic, and environmental interests. ILs play a double role in this context: they protect native biodiversity but are often framed as barriers to economic growth. In Brazil, nearly 14% of the territory is demarcated as ILs. This has led to conflicts with Brazil’s agricultural sector, particularly in the southernmost states, where agribusiness drives the economy. We hypothesize that this conflict leads to agricultural encroachment of ILs, which might become extension of farms, compromising their sustainability. We analyzed two decades of public data on soy coverage within ILs in Brazil’s southernmost states (Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul) and found that soy cultivation in ILs increased by over 116% in the last two decades, peaking in 2019 at 177% above the 2001 baseline. We argue that ILs urgently need a framework that enables the communities therein to benefit from income originating from land lease, while ensuring that encroachment is limited and does not pose threats to native biodiversity. This can be challenging due to growing political pressure to weaken socioenvironmental protection and ILs’ demarcation but is nevertheless essential for the sustainable coexistence of urban areas, farms, and ILs.

1. Introduction

Indigenous lands (ILs) are essential entities to protect cultural heritage and biodiversity, acting as key buffers against deforestation and environmental degradation. In Brazil, ILs cover nearly 14% of the national territory (~1.188.121 km2) and are constitutionally guaranteed for the exclusive use and preservation of indigenous communities [1]. Most (98.25% of ILs total area) of the ILs in Brazil are in the Amazon region and have been the focus of intense scrutiny due to humanitarian crises—such as the Yanomami emergency, which exposed the devastating impacts of illegal mining and state neglect [2]. However, the remaining 1.75% of ILs’ total area elsewhere in the country also face—often quietly—threats to their existence and to sustainability more broadly. In particular, the ILs in Brazil’s southernmost states have received far less scrutiny (e.g., [3,4]). This is an important oversight, because these territories can be equally critical for the conservation of threatened biomes, including the Atlantic Forest, Pampa, and Cerrado, which are among the most fragmented and ecologically vulnerable regions in the country and the world [5,6]. ILs not only safeguard sociobiodiversity but also provide essential ecosystem services in landscapes dominated by urban development and intensive agriculture, and we need to understand how anthropogenic pressures are shaping their usage and sustainable futures [7].

Brazil is the world’s largest soybean exporter and a central player in the global soy supply chain, producing over one-third of global exports in recent years [8]. The national soybean area has more than doubled since 2000, expanding from 26.4 million hectares to over 55 million hectares by 2019, largely at the expense of natural vegetation in the Amazon, Cerrado, Atlantic Forest, Pampa, and Pantanal biomes [9]. While the Amazon Soy Moratorium has slowed direct forest-to-soy conversion in parts of the Amazon, expansion continues through indirect land use change and in biomes with weaker protections [10,11,12]. Moreover, other biomes have not benefited from the Amazon Soy Moratorium, especially areas with highly fragmented biomes. This includes the southernmost states of Brazil, which are home to the Atlantic Forest (including Araucaria Forests), Cerrado, and Pampa. Soy is primarily destined for animal feed, with smaller shares for vegetable oil and human consumption [13]. Its cultivation is closely tied to infrastructure expansion, land speculation, and biodiversity loss, with measurable impacts on species richness and ecosystem services, even where forest loss is minimal [14].

ILs in the southernmost states of Brazil—Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul—are intertwined with a complex network of competing interests that can shape ILs’ sustainable futures. This is because these states are hubs of agribusiness. Together, these three states produced nearly 25% of the total value (in BRL) of Brazil’s soybean production and 49% of poultry production in 2023, highlighting their exceptional role in economic growth and commodity production [8]. In each of these states, small-scale farms dominate the soybean landscape: approximately 79% of soy-producing establishments in Paraná, 81% in Rio Grande do Sul, and 87% in Santa Catarina operate on less than 50 hectares [15]. The region also leads in the production of other commodities such as rice, tobacco, and wheat, which supports robust agro-industrial supply chains. These economic strengths make southern Brazil one of the most advanced and intensively farmed regions in the country [8,15].

There is a clear political tension regarding the permanence and expansion of ILs in Brazil and, in particular, the states of Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul [16]. Currently, land demarcation and identification processes for ILs are frozen due to a legal deadlock that remains unresolved in the Supreme Court. In territories located near regions dominated by agribusiness, Indigenous communities often depend on public assistance policies, as their lands are surrounded by private properties, making traditional and sustainable practices such as hunting and fishing unfeasible [17]. Therefore, internal conflicts have emerged within some communities (such as in Serrinha and Ivaí in 2024), as well as disputes with landowners living near ILs, exemplified by the ongoing dispute between Guarani indigenous communities and non-indigenous populations in the municipalities of Guaíra and Terra Roxa in Paraná [18]. Although the conflict between indigenous peoples and the national society in western Paraná is longstanding and marked by episodes of violence, the current context of land exploitation and agrarian disputes has led to unprecedented acts of brutality in the region, including two recent accounts of decapitation of indigenous people in the region (see [19]).

In this scenario, there is growing pressures on ILs to give away space for agricultural activities, which threatens national sustainable development. On 28 May 2024, Brazil’s Senate approved a controversial bill by Senator Esperidião Amin from Santa Catarina state [20], which aims to halt the demarcation of indigenous lands in Santa Catarina. If passed, this bill will weaken Brazil’s legal framework for IL recognition, opening the door for agribusiness expansion and anti-indigenous lobbying. Adding to this political climate, the recently approved PL2159/2021 (aka ‘PL da Devastação’ or PL of devastation) [21] overhauls the environmental licensing process, making it easier for large-scale projects to bypass stringent environmental assessments. Such deregulation risks accelerating deforestation, biodiversity loss, and the marginalization of indigenous communities—further augmenting the role of ILs as wildlife sanctuaries and the cornerstone for lasting cultural heritage. A key question remains: how are ILs in Brazil’s southernmost states interacting with the agricultural industry, and what are consequences of these interactions for the health and sustainability of ILs?

In this study, we analyzed over two decades (from 2001 to 2022) of data from the Global Forest Watch to analyze land use changes, with particular attention to the expansion of soy cultivation within IL boundaries. We were particularly interested in understanding if—and to what extent—ILs were being used for soy cultivation. Our hypothesis was that agribusiness expansion would lead to encroachment of IL areas, converting parts of ILs into soy plantations. We expected this encroachment to have increased over the years due to the growing contribution of the agribusiness to Brazil’s GDP and socioeconomic wealth. Our findings highlight the constant struggle between sociobiodiversity and economic development in Brazil’s south and report the vulnerabilities of ILs to surrounding agricultural pressures. We emphasize that ILs are indispensable not only for local sociobiodiversity but also for broader sustainability strategies in Brazil, and national policies that integrate IL needs with sustainable agricultural development is urgently needed to safeguard sustainable development in the country.

2. Methods

2.1. Indigenous Land and Soy Plantation Data

We focused our analysis on Brazil’s three southernmost states: Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul (Figure 1). Polygons of ILs are publicly available from the Fundação Nacional dos Povos Indígenas (FUNAI), which define the official boundaries of demarcated indigenous territories. To quantify land use changes and the expansion of soy cultivation within these ILs, we extracted data from the Global ForestWatch platform (https://data.globalforestwatch.org/datasets/soy-planted-area-/about, accessed on 24 April 2025) [22], covering the period from 2001 to 2022. This dataset provides annual estimates of soy plantation areas at a fine spatial resolution, allowing us to track temporal and spatial dynamics across more than two decades. The link to access the specific data used here is provided in Table S1. State boundaries were extracted from the official IBGE state shapefile.

Figure 1.

Map of Brazil with the three southernmost states highlighted. PR: Paraná (blue), SC: Santa Catarina (green), and RS: Rio Grande do Sul (orange).

2.2. Study Areas

We compiled boundaries of 79 indigenous lands (ILs) across the three southern Brazilian states: 24 in Paraná, 25 in Santa Catarina, and 30 in Rio Grande do Sul. IL sizes varied widely, ranging from very small parcels of 5 ha to large territories of 37,078 ha, with a mean area of approximately 4222 ha. The principal ethnic groups represented were the Kaingang (28 ILs), Guaraní (17 ILs), and Guarani Mbya (15 ILs), with additional ILs occupied by Guarani Nhandeva, Xokléng, and mixed communities (e.g., Kaingang–Guaraní). The ILs in southern Brazil are distributed across two major biomes. Most territories in Paraná and Santa Catarina and part of those in northern Rio Grande do Sul occur within the Atlantic Forest biome, particularly in the highland Araucaria mixed forest subregion. By contrast, ILs in the southern and western portions of Rio Grande do Sul are located in the Pampa biome, characterized by natural grasslands interspersed with wetlands and gallery forests. Table 1 summarizes the detailed information about each IL in relation to its name, ethnicity(ies) and area (ha).

Table 1.

Characteristics of indigenous lands (ILs) in southern Brazil, including state, name, resident ethnic group(s), and total area.

2.3. Data Analysis

All spatial analyses were conducted in R v.4.5.0 (R Core Team, 2025) [23] using the ‘terra’ package v 1.8-54 and the ‘sf’ package v 1.0-21 [24,25], which enables efficient manipulation of large raster and vector datasets. To quantify soy expansion within indigenous lands (ILs) in southern Brazil, we combined annual maps of the soy planted area with official IL boundary datasets. Annual soy rasters (2001–2022) were obtained as tiled GeoTIFFs in geographic coordinates (WGS84, EPSG:4326). For each year, individual tiles were mosaicked and cropped to the extent of Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul states and then masked to the state boundaries. IL polygons were made topologically valid (sf::st_make_valid), merged, and simplified for plotting using rmapshaper v 0.50 [26]. All vector data (states, ILs) and annual soy rasters were reprojected to South America Albers Equal Area Conic (EPSG:5880). Pixel areas (in hectares) were derived from the raster resolution, and soy cover within each polygon was quantified using the exactextractr package v 0.10.0 [27]. Specifically, we summed the soy values multiplied by the fractional pixel overlap with each polygon to obtain the soy planted area (ha) and divided this by the polygon’s total area (derived with st_area) to calculate the percentage of each IL planted with soy. Data visualization and descriptive statistical analyses were conducted using the ‘ggplot2’ package v3.5.2 [28].

3. Results

3.1. Soy Cultivation Has Intensified Across ILs over the Last Two Decades

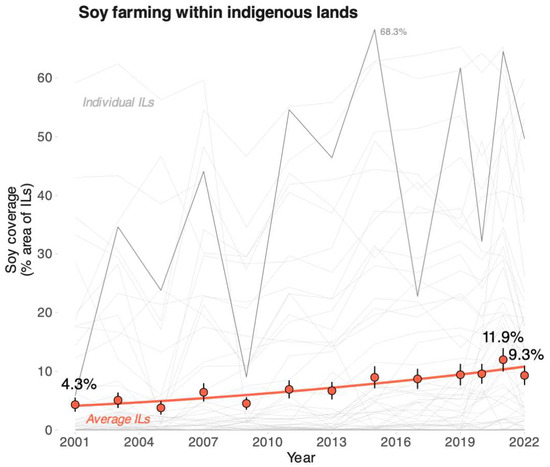

We found that soy cultivation in ILs has expanded markedly over the past two decades. In 2001 (baseline), the average soy coverage across ILs was approximately 4.3%, but by 2022 it had nearly tripled, reaching 11.9%, an increase of ~177% (Figure 2). In 2023, the soy coverage decreased slightly to 9.3%, representing an increase of ~116% from the baseline. The increase appears to be non-linear, with a steady upward trend in recent years. The last decade (2012–2022) of monitoring data appears to show a more pronounced rise in the average soy coverage compared to the 2001–2010 period. Public policies and leadership attitude towards ILs and agribusiness certainly contributed to this trend.

Figure 2.

Indigenous lands turned into soy farms in Brazil’s southernmost states of Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul. We analyzed Global Forest Watch Soy Cover data from 2001 to 2022 (links for raw data in Table S1). We estimated the percentage (%) area of soy planted within ILs by calculating the soy planted area over the total IL area, multiplied by 100. We calculated the percentage of soy area for individual ILs (grey lines) and the average across ILs (red line) over time. The plot was made using the ‘ggplot2’ package [28].

3.2. Some ILs Have Most of Their Land Coverage in Soy

Our data revealed that some ILs are more vulnerable to encroachment than others. While some ILs experienced minimal or no soy cultivation during the monitoring period, others had over 60% of their territory converted to soy, with the highest recorded value peaking at 68.3% in 2016. This shows that nearly three-quarters of the IL was covered with soy. Overall, our results suggest that southern ILs are increasingly vulnerable to agricultural encroachment, highlighting a tension between traditional land use and the surrounding agribusiness economy.

3.3. Soy Expansion Has Been Uneven but Consistent Across States

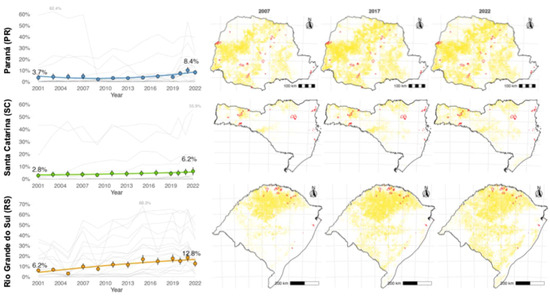

We found marked geographic differences in the extent and trajectory of soy cultivation within ILs by state. In Paraná, soy cultivation within ILs remained relatively stable from 2001 to the mid-2010s but has increased since 2017, doubling from 3.7% in 2001 to 8.4% in 2022, an overall increase of ~127% from the baseline (Figure 3). In Santa Catarina, soy cultivation within ILs has consistently remained the lowest among the three states, rising from 2.8% in 2001 to 6.2% in 2022, which is still a ~121% increase (Figure 3). By contrast, ILs in Rio Grande do Sul have experienced the strongest and most sustained expansion, with the mean soy coverage increasing from 6.2% in 2001 to 12.8% in 2022, a ~106% increase, and with some ILs exceeding 60% of their territory planted with soy (Figure 3). Maps for 2007, 2017, and 2022 are shown to illustrate how soy has progressively encroached into ILs across the three states, with expansion concentrated in the northern and western regions of Paraná, the western region of Santa Catarina, and across large areas of central (north through south) Rio Grande do Sul (Figure 3). Together, these results demonstrate that ILs in southern Brazil are not equally exposed to soy expansion, with the pressure being most intense in Rio Grande do Sul. Nevertheless, all three states doubled the soy encroachment in ILs in 2022 compared with 2001.

Figure 3.

Spatial and temporal dynamics of soy cultivation within ILs in Paraná (PR), Santa Catarina (SC), and Rio Grande do Sul (RS). Left panels: maps of soy cover (yellow) in 2007, 2017, and 2022, with state borders (black) and IL boundaries (red). Right panels: trajectories of soy coverage (%) within ILs from 2001 to 2022, showing individual ILs (grey lines) and the state-level average (colored lines: blue for PR, green for SC, orange for RS). End-point values (2001 and 2022) are annotated for each state. Scale bars for PR and SC are the same, and for clarity, we omitted the scale bar for SC.

4. Discussion

Our findings reveal an alarming trajectory of agricultural encroachment within indigenous lands (ILs) in Brazil’s southernmost states. The increase in soy cultivation by over 116% since 2001 reflects not only the growing economic pressures from agribusiness but also the vulnerability of ILs in regions, where biomes like the Atlantic Forest, Pampa, and Cerrado are already under intense anthropogenic stress (e.g., [5,29]). This expansion aligns with broader national patterns of soybean-driven land use change, which disproportionately affects biodiversity hotspots such as the Atlantic Forest and Cerrado [9,12]. In these biomes, soy cultivation is among the top drivers of habitat loss, with measurable impacts on multiple taxa including plants, birds, and amphibians, at both regional and global scales [9,11,12,30].

The impacts of soy expansion are not necessarily unidimensional and uniform. Recent work on biodiversity-specific footprinting shows that forest loss is not always a good proxy for sociobiodiversity decline across landscapes [14]. This is relevant for ILs that are more well integrated into urban landscapes, where agricultural encroachment may degrade the land and forest mosaics without necessarily triggering large-scale deforestation metrics. Additionally, the sociobiodiversity impacts of soy cultivation expansion are often compounded by indirect effects, such as infrastructure development and land speculation—both of which accelerate secondary deforestation and habitat fragmentation [10,13]—and direct ethnic conflicts [31].

Our data highlight that southern ILs are at increasing risk and urgently require targeted policy interventions. The expansion of commodity crops—particularly soy—within ILs will continue to compromise sociobiodiversity, disrupt cultural practices, and undermine the constitutional rights of indigenous peoples. These concerns are supported by findings from recent analyses showing that, while the economic benefits of soybean production are often localized, the environmental costs, especially sociobiodiversity loss, are spatially widespread, affecting both focal and adjacent areas [32].

Recent political activities have added further uncertainty to ILs and sociobiodiversity conservation in Brazil (see Introduction). Proposals such as the bill from Senator Esperidião Amin [20] and the recent uproar against environmental conservation—such as the PL 2159/2021 (PL of Devastation, [21]), which was vetoed by the President Luis Inacio Lula da Silva with amendments—threaten sustainability in two ways: first, by halting IL demarcation in Santa Catarina, and second, by dismantling policy frameworks designed to safeguard indigenous rights and ecological health. These developments resemble broader governance failures to enforce zero-deforestation commitments in commodity supply chains [14] and risk intensifying the policy–agribusiness alignment that prioritizes short-term revenue over long-term socioenvironmental resilience.

It is in our view futile to try and fully reverse the impacts of encroachment, as this has multidimensional and complex socioeconomic interactions that, at times, can benefit indigenous people and overcome shortcomings from the State. However, we must mitigate these challenges. To achieve this, we argue Brazil need structured frameworks that enable indigenous communities to regain control of agricultural practices and the wealth they generate within their lands. This includes moving away from illegal leasing arrangements that benefit external actors and instead, adopting regulated indigenous-led agricultural models. Similar to recommendations by Boerema et al. (2016) [13] and Lucas et al. (2021) [12], such models should integrate sustainable cropping practices (e.g., crop rotation, reduced agrochemical use) with cooperative organization, technical assistance, and access to credit other than from agribusiness. Moreover, policies should account for biodiversity-intactness metrics [33] rather than relying solely on deforestation rates as performance indicators, thereby ensuring that agricultural development aligns with both cultural values and environmental thresholds.

Finally, the future of ILs in Brazil’s southern states will depend on integrating indigenous rights with sustainable development strategies that respond to the realities of a rapidly expanding agricultural sector. Holistic monitoring approaches—combining remote sensing, biodiversity risk assessment, and socioeconomic evaluation—are essential to avoid repeating the pattern seen elsewhere in Brazil, where soybean expansion has often preceded irreversible ecological degradation [9,34]. Our results underline the urgency of designing economic alternatives that reconcile cultural heritage and biodiversity conservation with the demands of agribusiness-driven landscapes. In the absence of these actions, we foresee an escalation of ongoing conflicts, which threaten sociobiodiversity and agricultural growth, compromising both ecological integrity and the sustainable futures of indigenous and non-indigenous communities.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study highlights the rapid expansion of soy cultivation within ILs in Brazil’s southernmost states, stressing the growing tension between agribusiness and sociobiodiversity. By quantifying over two decades of land use change, we demonstrate that ILs—although constitutionally protected—are increasingly vulnerable to economic pressures and political decisions that favor agricultural expansion. We argue that a solution to this challenge will require policies that regulate IL use and empower indigenous communities to liaise with agribusiness for sustainable ways to produce commodities within ILs without threatening ILs’ role of safeguarding cultural heritage and sociobiodiversity. This is crucial because ILs have multiple roles including safeguarding sociobiodiversity (e.g., [7,35]). Our proposed solution could be used in other regions of Brazil that also face similar conflicts (e.g., Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul states) [36], as well as serve as a model for conflicts within ILs globally (e.g., [37,38,39].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17219918/s1, Table S1: Links to Soy planted. Table S2: Soy coverage relative to total IL area (raw data).

Author Contributions

J.M. and F.K. conceptualized the study. J.M. collected and analyzed the data, wrote the draft and revisions of the manuscript. F.K. wrote the draft and revisions of the manuscript. Both authors approved the submission of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- STF. Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil, Article 231. 1988. Available online: https://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/legislacaoConstituicao/anexo/brazil_federal_constitution.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Mallert, C. Indigenous Territory Still in Crisis Despite Brazil’s Expulsion of Miners. The Guardian. 2 August 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/02/brazil-indigenous-yanomami-crisis-miners-expulsion (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Ferrante, L.; Fearnside, P.M. Brazil threatens Indigenous lands. Science 2020, 368, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.; Vale, J.C.E.D.; Costa, G.d.M.; dos Santos, R.C.; Filho, W.L.F.C.; Gois, G.; de Oliveira-Junior, J.F.; Teodoro, P.E.; Rossi, F.S.; Junior, C.A.d.S. The forests in the indigenous lands in Brazil in peril. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.C.; Grelle, C.E. The Atlantic Forest. In History, Biodiversity, Threats and Opportunities of the Mega-Diverse Forest; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, B.R.; Martins, E.; Martinelli, G.; Loyola, R. The effectiveness of protected areas and indigenous lands in representing threatened plant species in Brazil. Rodriguésia 2018, 69, 1539–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, S.T.; Burgess, N.D.; Fa, J.E.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Molnár, Z.; Robinson, C.J.; Watson, J.E.M.; Zander, K.K.; Austin, B.; Brondizio, E.S.; et al. A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Produção agropecuária no Brasil. 2023. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/explica/producao-agropecuaria/pa (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Song, X.-P.; Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.; Adusei, B.; Pickering, J.; Adami, M.; Lima, A.; Zalles, V.; Stehman, S.V.; Di Bella, C.M.; et al. Massive soybean expansion in South America since 2000 and implications for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnside, P.M. Soybean cultivation as a threat to the environment in Brazil. Environ. Conserv. 2001, 28, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, F.; Solar, R.; Lees, A.C.; Martins, L.P.; Berenguer, E.; Barlow, J. Reassessing the role of cattle and pasture in Brazil’s deforestation: A response to “Fire, deforestation, and livestock: When the smoke clears”. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.R.G.; Antón, A.; Ventura, M.U.; Andrade, E.P.; Ralisch, R. Using the available indicators of potential biodiversity damage for Life Cycle Assessment on soybean crop according to Brazilian ecoregions. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerema, A.; Peeters, A.; Swolfs, S.; Vandevenne, F.; Jacobs, S.; Staes, J.; Meire, P. Soybean Trade: Balancing Environmental and Socio-Economic Impacts of an Intercontinental Market. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotoks, A.; Green, J.; Ribeiro, V.; Wang, Y.; West, C. Assessing the value of biodiversity-specific footprinting metrics linked to South American soy trade. People Nat. 2023, 6, 1742–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, A.S.; Fasiaben, M.C.R.; Oliveira OCde Almeida, M.M.T.B. Características Principais dos Estabeleci-Mentos Agropecuários Produtores de Soja do Brasil Segundo Estratos de Área Colhida. Circular Técnica 204; Embrapa Soja: Londrina, Brazil, 2024; Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/1164808 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Pires, J. Mortes, Corrupção e Milícia: O Saldo do Arrendamento de Terras Kaingangs no Paraná; Instituto Socioambiental: São Paulo, Brazil, 2023; Available online: https://terrasindigenas.org.br/es/noticia/220850 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Tommasino, K.; Mota, L.T.; Rodrigues, I.C.; Faustino, R.C.; da Rocha, F.V.; Quinteiro, C.T.; Novack, E.; Jacomini, S.; Souza, P.d.e.; Buratto, L.G. Diagnóstico Da Situação Sócio-Cultural E Econômica Da T.I. Ivaí; Universidade Estadual de Maringá: Maringá, Paraná, Brazil, 2002; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Masuzaki, T.I. A luta dos povos Guarani no extremo oeste do Paraná. PEGADA Rev. Geogr. Trab. 2015, 16, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MDHC. Nota Sobre o Assassinato de Jovem Indígena em Guaíra (PR). 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mdh/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2025/julho/nota-sobre-o-assassinato-de-jovem-indigena-em-guaira-pr (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Senador Esperidião Amin. Projeto de Decreto Legislativo nº 717 de 2024. Senado Federal. 2024. Available online: https://www25.senado.leg.br/web/atividade/materias/-/materia/166664 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Zica, L. Câmara dos Deputados. In Projeto de Lei do Senado nº 2159 de 2021; Senado Federal: Brasília, Brazil, 2021; Available online: https://www25.senado.leg.br/web/atividade/materias/-/materia/148785 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Global Forest Watch. Global Forest Watch. World Resources Institute. 2014. Available online: https://www.globalforestwatch.org (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Hijmans, R. terra: Spatial Data Analysis. R package, Version 1.8-42. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Pebesma, E. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R J. 2018, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teucher, A.; Russell, K. rmapshaper: Client for ‘mapshaper’ for ‘Geospatial’ Operations, Version 0.5.0.9000. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/ateucher/rmapshaper (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Baston, D.; ISciences, LLC. Package ‘exactextractr’; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=exactextractr (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Ribeiro, S.; Moreira, L.F.B.; Overbeck, G.E.; Maltchik, L. Protected Areas of the Pampa biome presented land use incompatible with conservation purposes. J. Land Use Sci. 2021, 16, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóbrega, R.L.B.; Alencar, P.H.L.; Baniwa, B.; Buell, M.-C.; Chaffe, P.L.B.; Correa, D.M.P.; Correa, D.M.D.S.; Domingues, T.F.; Fleischmann, A.; Furgal, C.M.; et al. Co-developing pathways to protect nature, land, territory, and well-being in Amazonia. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondardo, M. The struggle for land and territory between the Guarani Kaiowá indigenous people and agribusiness farmers on the Brazilian border with Paraguay: Decolonization, transit territory and multi/Transterritoriality. J. Borderl. Stud. 2022, 37, 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.F.B.; Viña, A.; Moran, E.F.; Dou, Y.; Batistella, M.; Liu, J. Socioeconomic and environmental effects of soybean production in metacoupled systems. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlich, L.; Jung, C.; Schaldach, R. The Biodiversity Footprint of German Soy-Imports in Brazil. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourençoni, T.; Junior, C.A.d.S.; Lima, M.; Teodoro, P.E.; Pelissari, T.D.; dos Santos, R.G.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Luz, I.M.; Rossi, F.S. Advance of soy commodity in the southern Amazonia with deforestation via PRODES and ImazonGeo: A moratorium-based approach. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bryan, C.J.; Garnett, S.T.; Fa, J.E.; Leiper, I.; Rehbein, J.A.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Jackson, M.V.; Jonas, H.D.; Brondizio, E.S.; Burgess, N.D.; et al. The importance of Indigenous Peoples’ lands for the conservation of terrestrial mammals. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastens, J.H.; Brown, J.C.; Coutinho, A.C.; Bishop, C.R.; Esquerdo, J.C.D.M. Soy moratorium impacts on soybean and deforestation dynamics in Mato Grosso, Brazil. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begotti, R.A.; Peres, C.A. Rapidly escalating threats to the biodiversity and ethnocultural capital of Brazilian Indigenous Lands. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J.E. Soy states: Resource politics, violent environments and soybean territorialization in Paraguay. J. Peasant. Stud. 2019, 46, 316–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepkiewicz, L.; Dale, B. Keeping ‘our’ land: Property, agriculture and tensions between Indigenous and settler visions of food sovereignty in Canada. J. Peasant. Stud. 2019, 46, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).