1. Introductory Vignette

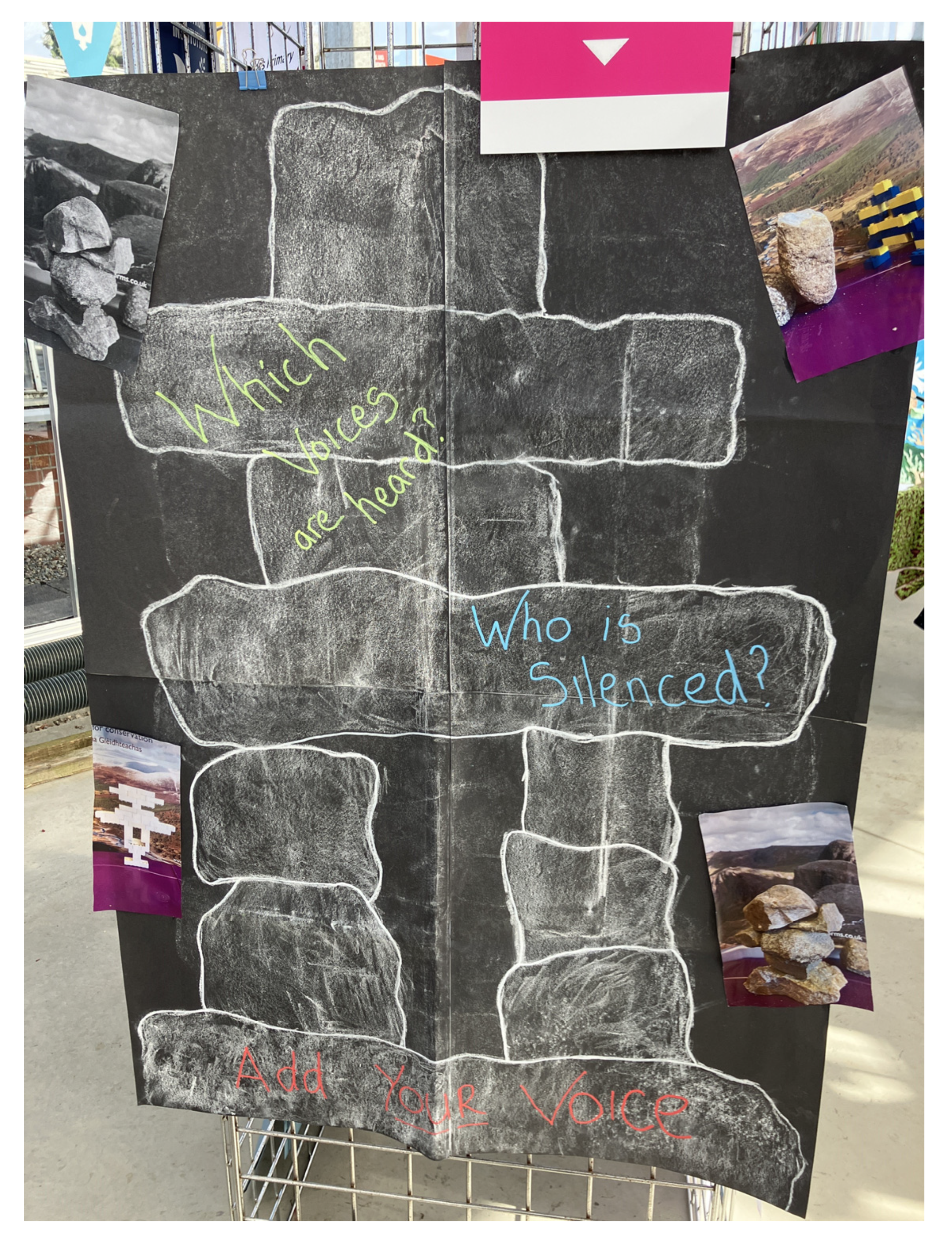

An Inukshuk, a stone landmark built by Inuit people in the Arctic region of North America, was created by children and young people in the Highlands region of Scotland (

Figure 1). Inukshuk means ‘in the likeness of a human’ and are considered a ‘voicing’ of navigation or warning of dangers. They are made of local, naturally available stones, stacked to resemble the human form, and it is disrespectful to build Inukshuks that damage the landscape or interfere with the natural habitat. Previously, during the United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference in Baku in November 2024, this school invited all attendees at their mock-COP to bring stones from their area to build an Inukshuk to represent their collective views.

2. Introduction

We do not know as much as we should about what children and young people think about how their societies should respond to climate emergencies [

1,

2,

3]. We know they are aware of the situation and many feel climate-related anxiety [

4,

5], probably connected with a lack of agency in being part of the solutions to this human-made situation [

6]. Societies have few formal mechanisms for them to express their feelings and opinions, despite their rights under article 12 of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child [

7] ‘to express their views, feelings and wishes in all matters affecting them, and to have their views considered and taken seriously’ [

8] (p. 29), and under article 13 that ‘the child shall have the right to freedom of expression’. Children and young people should have the right to play an active role in decisions which affect them—releasing their potential to be activists [

9]. However, our collective experiences across Scotland, Nigeria and Kenya, is that young people’s voices are often silenced or silent in relation to climate change decision-making This view is supported by evidence from the 2024 UNCCC report [

10] which called for “greater inclusion of children’s voices in national adaptation planning processes”(p. 6).

This article reports on an international project that has been exploring the roles of adults in facilitating children’s rights to be heard in addressing the climate emergency. The project created spaces for communities to engage with young people’s artivism, which is defined as “Art-actions to effect societal transformation” [

11] in ways that can transcend the dominant consensus about what voices or opinions are part of the conversation [

12]. This article does not report the findings of the study itself, but, rather, reflects on its approach.

2.1. The Need for Environment/Climate Community-Relevant Research

The impact of climate change is widespread across communities, making it critical that all ages are included in community-relevant research informing future environment/climate action [

13]. Connecting global climate issues to local community issues is central to fostering action, but there needs to be assurance that dialogue between community participants and researchers avoids a “one-way didactic delivery” [

14] (p. 830). Community is more than humans with a shared connection, it embraces the inter-connectedness of all bodies (human and others) with their environments, materials, spaces and places [

15,

16]. Positioning research within a community indicates clearly where agency and efficacy lie and gives opportunities to share findings not only within the local community but further afield too, all of which can result in action [

14].

There is much literature reporting on how the older generation influence the younger ones [

17]. Yet for many, the promotion of intergenerational learning is vital for climate action [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Participatory research has proved effective in promoting community engagement and action. For example, one large-scale European study developed an understanding of the priorities for communities and explored potential solutions [

21]. Importantly, “creating substantive conversations between the different sets of expertise” can result in new local knowledge and ways of “understanding, seeing and acting in the world” [

22] (p. 8). Direct community involvement results in ‘”on-the-ground” approaches’ bringing researchers closer to “participants in action” [

23,

24] (p. 14; 22).

2.2. Facilitating Multigenerational Sustainable Practices

The project facilitated and celebrated children’s contributions to societal decision-makers’ thinking by encouraging expression through a broad understanding of the arts and using their preferred languages. We invited policymakers, community and business leaders to exhibitions of artefacts made by children and young people in Scotland, Kenya and Nigeria, creating intergenerational manifestos. The project developed sustainable partnerships through co-creating opportunities to facilitate sustainable thinking and acting, both locally and at a distance. This involved being responsive to diverse ways of thinking, being, relating and collaborating.

This article explores the responsibilities and relationalities of the adults involved, and the ethical principles and practices which had to be resolved. It illustrates how sustainable pedagogies, building from and bringing together existing initiatives in Scotland and Kenya came to create something new in Nigeria. These partnerships work across traditional disciplines and contexts providing vital wisdom about local and global sustainability, navigating challenges together, and learning with one another about what is needed for this endeavour. The ways of working reported are an enactment of the sustainable pedagogies principles and practices captured in The Open University

Sustainable Pedagogies badged open course [

25]. They illustrate roles adults can play, how care and compassion are central sustainable pedagogies, and the ways education for sustainability involves pedagogies of collaboration and co-creation which entangle us beyond our immediate formal educational settings. Focusing on the adults is not to privilege adult experiences over those of the young people, artworks or others involved in this project, but to provide a frame through which to explore the issues surrounding facilitating a multi-located, multi-partnership, and multimodal project.

3. Ethical Approaches to Partnership Working

This international, distributed partnership needed to reveal and counter power imbalances in every aspect, starting with the task of partnership building. Agreement to ethical principles was embedded into our practices as part of our collective vision to shape research and practice, seeking to enact democratic, locally relevant, and empowering evidence-gathering. This required the flexibility to embrace different variants of ethical and practical protocols. The leading higher education institution had access to funds for partner activities and hence led responsibilities to approve all activities through its Human Research Ethics Committee. Power imbalances were linked to partners spanning the Global North and South, and intersecting Higher Educational Institutions and Third Sector Organizations. We accepted our responsibilities to participants already marginalized by being children and young people within societies led by adults, or marginalized or at risk of being marginalized by their communities. Countering this in Scotland required reaching out across rural areas to schools in the Highlands region, and in Kenya it required working with young people at risk of engaging in or having engaged in criminal activity. In Nigeria, the project was introduced in the capital Abuja so that the children could engage with powerful policymakers, in what would be a truly novel experience.

We drew upon the Global Code of Conduct for Equitable Partnerships [

26] to guide our ethical decision-making. The TRUST Code is a resource for all research stakeholders who want to ensure that international research is equitable. Embracing this code led to both revelations and actions. Firstly, as the Scottish and Kenyan partners had initiated the activities on which the project was building, the role of the higher institution became not to lead, but to follow—and to share the learning across the three settings. Secondly, the negotiation of tailored collaborative agreements involved ethical approval and adapted documentation from the higher education institution in Nigeria and regional and national approval in Kenya. Adaptations were required by the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, and by the Amref Health Africa and NACOSTI review bodies in Kenya, and protocols and materials were adapted accordingly. The latter involved ethical training for participants, including the young co-researchers, empowering them to lead ethical decision-making in the field. Thirdly, and as a consequence of the other revelations, the Nigerian team who were new to artivism, could think locally, laterally, and creatively about their work in Nigeria, creating new materials as contributions to the project’s outputs and co-leading the project.

4. Art for Action

Our project Art for action is an educational intervention that fosters art-based expressions by children and young people and invites them to become climate activists beyond their school settings. We define ‘The Arts’ in its broadest sense, encompassing performing arts, digital arts, artistic expressions through language and gaming.

A growing number of authors advocate specifically arts-based and participatory approaches to engagement with the climate emergency. Trott [

27] emphasized art as prioritizing awareness, agency and action. Art-based approaches are an accessible and inclusive way for children and young people to voice their views about climate change, including climate anxiety. However, interventions have tended to be short-term and small-scale, some examples include art-based action research in natural settings with six children in Finland [

28]; canvas mural creation by 10–12 year olds in the USA [

29]; poetic approaches with nine 18–31 year olds in Canada [

5], and photovoice practices using SHowED reflections with 10–12 year olds in the USA [

30]. Such studies show that art-based practices effectively enhance nature-connectedness and environmental agency; they are generally limited in scale, focus only on the children’s responses and explore the needs and ways of supporting those in the Global North.

Gaming is a powerful means of self-expression, the design of which can be considered a creative, arts-based activity [

31,

32]. Computer games can be regarded as art in its widest sense and play an important role in ecological critique and “engage young people with the issue of climate change and encourage them to think, feel and act in ways that help address the problem” [

33] (p. 713). Of particular interest are gaming projects which go beyond learning and focus on enhancing a sense of agency regarding the challenges brought about by climate change. There is limited inclusion of children and young people in the design of such games, but children and young people could be game designers, rather than consumers [

34]. For instance, 11–16-year-old volunteers from schools in Romania, Italy, Estonia, and Finland were invited to participate in games which used group simulations to address urgent environmental issues and propose solutions to these situations [

35]. Importantly, participants included children with learning difficulties, those at risk of exclusion, as well as some with a history of school failure. The children made emotional connections with their learning and showed motivation for action. Gaming approaches to learning about climate change must foster a connection between play and actual articulation of climate views and action.

It is this process of articulating emotions, learning, opinions, and needs that creates the potential for the artefacts to ‘act’ upon community discussions and decision-making, moving the emphasis to ‘artivism’ [

36]. During artivist experiences, children and young people’s climate-related ‘voices’ begin to arise, when conceptualizing problems, exploring messages, selecting materials, in the moment of producing a piece of work, and in their personal engagements with others. This demonstrates how children and young people can become activists rather than symbols of or passive participants in the lived experience of climate change. Applegarth [

37] examined youth-led activism from the 1990s to the present, focusing on how children and young people can navigate and leverage their age as what she terms a ‘rhetorical resource’ in advocacy efforts. Our project aims at facilitating such an agency and encouraging children and young people’s direct engagement with their communities and leaders, helping them realize the potential of their artivism.

5. Posthumanist Approaches to Methodological Acts

Posthumanism is characterized by its direct challenge to human exceptionalism, binary thinking, and power imbalances, arguing that humans can no longer afford to be seen as the egocentric pinnacle of what occurs (of power, control, and dominance in the world) [

38,

39,

40]. Instead, it argues that humans (particularly those situated in the Global North) need to rethink and renew relationships with each other and with the world, moving to an ecotistical view which accepts the diversity of humans’ privileges and the ways in which other non-human actors do and can participate with us (

Figure 2).

The literature on sustainability points to the vital role posthumanist views of materials–environments–bodies play in challenging the anthropocentric frameworks in which sustainability agendas have operated [

41,

42]. Materials and bodies are constantly intra-acting, being enmeshed and entangled, which Braidotti [

37] notes critiques notions of species hierarchies and advancing the notion of ecological justice. As existing binaries, hierarchies and practices that revolve around human exceptionalism are disrupted by posthumanist thinking, methodologies need to respond. In recognizing the broad and dynamic nature of inter-species and species–material entanglements, researchers “begin to do it differently wherever we are in our projects” [

43] (p. 635). The aim becomes producing “multiple and heterogeneous knowledge pathways that are radically generative for educational research” [

39] (p. 7).

Recognizing this need for multiple, local, bodily, and materially engaged methodologies, and at the same time ensuring some coherence of experiences across the three international partners, the project developed key principles. These developed from the

Sustainable Pedagogies course [

25], and were considered for coherence and efficacy with posthumanism, arts-based, and artivist approaches. These principles formed an open, flexible, and responsive structure to allow us to enact the project across our different communities and environments (

Figure 3), allowing for differences and recognizing the contexts of the research in three different countries with localized relationships between people, materials, environments, and project materials. The focus of this research is on what is ‘set in motion’ and what is ‘made’ through the experiences of the research, where all of us (children, young people, adults, materials, spaces, environments) entangle with each other in different performances of the research. An important part is acknowledging the role the materials of the project play in ‘setting in motion’ different entanglements, what is made, and what we become [

38] as a result.

Research materials were co-created across our project partnership as common starting points across the three contexts. These included a confidence quiz (available as a physical board to be completed individually, a digital board for completion by groups in classes (

Figure 4) or as a quick survey for individuals), responsive SHowED ‘postcards’ (

Figure 5), and climate conversations (

Figure 6) with the young people and the adult attendees at the exhibit events. Adaptations were developed in response to feedback from educators and youth workers once the original idea for each tool was shared with them.

The acronym SHowED prompts critical reflection:

See: “What do you see here?”

Happen: “What is really happening here?”

Our lives: “How does this relate to our lives?”

Why: “Why does this concern, situation, or strength exist?”

Do: “What can we do about it?”

In each national setting, different consent protocols (recruitment, participant-information and consent forms) were required by the Nigeria and Kenya local ethical committees. Each of these research experiences were designed as ‘invitations’ for engagements between young people, policymakers, and researchers concerning the materials, understanding climate change, and the local/global communities they are entangled with. The ‘doing’ of the artworks themselves were central, to recognise their power to ‘set in motion’ such intra-actions. Therefore, this article is illustrated with artefacts from the children and young people, keeping their artivist voices central to this work. At the time of writing, over 600 young people in Scotland (aged between 4 and 18), 35 across a range of countries led by Kenya (aged between 18 and 25), and 40 in Nigeria (aged between 5 and 17) are involved in Art for Action making, alongside 27 educators in Scotland, 8 in Nigeria and 4 youth leaders in Kenya. Over 500 members of the public have engaged with the artefacts in Scotland, over 30 policymakers in Nigeria, and at least 30 in Kenya.

6. Project Viewpoints

The vignettes below offer viewpoints about different adults’ involvement in aspects of the project partnership. We invited each partner to invite someone to offer their perspectives, alongside the central team reflecting on their roles in progressing the project’s aims. Each of the viewpoints are based around the scaffolding of the project and the following are responses to being asked to reflect on the project’s aims of looking for changes in (a) understanding, (b) explaining, (c) influencing, and (d) acting for a sustainable future.

6.1. Youth Game Designer in Kenya: Teresiah Kaberia, Research Scholar Attached to the AAYMCA

In today’s digital world, where youth are constantly connected to their phones, gaming offers a powerful way to educate and inspire—transforming what might seem like a distraction into a tool for learning and positive change. Attending expert-led workshops in game design deepened my understanding of how games can be more than just entertainment. One of the highlights of being part of this project was conducting prototype testing in Naivasha (Nakuru County, Kenya) where we observed firsthand how young players interacted with our chess-based climate game. This unique twist on traditional chess integrates environmental decision-making into gameplay, challenging players to think strategically about sustainability while competing (

Figure 7).

It was inspiring to see how quickly the youth grasped the concept and how engaged they became not just in winning the game, but in discussing real-world climate issues sparked by the gameplay. For young people, a game is more than play, it can be a powerful moment of learning, reflection, and action.

6.2. Secondary School Educator in Scotland: Keith, Principal Teacher of Geography in the Scottish State Secondary Sector (With Children Aged 11–18 Years of Age)

Primary schools are good at using art to express their pupils’ views when it can be difficult for younger children to explain their thoughts and feelings to adults. At this event, they found new ways to express themselves, such as through their song and hedgehog artworks (

Figure 8).

These are very engaging and build compassion. I also noted that one or two took a new line, in particular the badger-focused ones (

Figure 9), connecting with Celtic Scottish mythology.

This fits with our work in our secondary school on decolonising the curriculum. Our work is in the exhibition on the Inukshuk and northern indigenous communities. I can see lots of examples of climate change being no longer a topic to teach in class, but rather as relevant to all aspects of life. I really liked the sketch pads related to fast fashion that show how climate change is embedded in societies (

Figure 10). These examples show young people’s awareness of a global circular economy and how this needs to be understood to become sustainable.

I am perhaps a little cynical after 20 years of trying to promote education for the environment! Will the presentations today affect the policymakers here? Anecdotally, the many children involved in climate strikes prior to lockdown are one of the reasons why the Scotland-wide climate conversations happened. I have stopped focusing learners on their carbon footprint, as this places the responsibility for action on the individual, when this is the role of societal leaders, and it is good that we have some Members of Parliament and of the Scottish Parliament at this exhibition. The imagery of melting ice caps is just not having the impact everyone hoped.

6.3. Project Lead in Kenya: Lloyd Muriuki Wamai, Programme Innovation and Management Executive for the AAYMCAs

The AAYMCAs have spent the last few years listening closely to young people—especially those on the margins. What has become painfully clear is that climate change is not just an environmental issue. For many youths across Africa, it is a justice issue, driving young people into vulnerability, unemployment, conflict with the law, or worse. From illegal gold mining in Zimbabwe to militant recruitment at the Kenyan coast, climate-induced hardship is a major, under-acknowledged force shaping youth realities.

The Climate Games Project is a new kind of engagement, enabling young people to be designers and co-creators of a new, climate-resilient world. Through the project, 35 young people from five countries—Kenya, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Sierra Leone, and Gambia—are trained to create games rooted in their lived realities. These are hyper-local, co-created tools for dialogue, learning, and action. From a Climate Chess game in Mombasa, to a card game targeting garbage site workers in Sierra Leone, these innovations are sparking new conversations. But the magic happens when the youth sit across policymakers, not in confrontation, but in play. The game becomes a platform—a shared space where climate adaptation strategies are imagined together, and young people shape responses.

We hope these games will give rise to powerful youth-led platforms for climate adaptation. We want to equip young people to design, adapt, and lead. Africa needs youth-led, locally owned, and unapologetically bold climate resilience. Art in Action is focused on research aimed at evidence-gathering across our wider Climate Games activities.

6.4. Project Lead in Nigeria: Deborah Ayodele-Olajire, Specialist in Climate Action and Sustainability Science, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Nigeria’s ecological zones range from mangrove swamps in the south to the Sahel Savanna in the north. Between these two zones are Freshwater Swamp Forests, Lowland Rain Forests, the Derived Savanna, Guinea Savanna, and Sudan Savanna ecological zones. Climate change is exacerbating flooding and multi-year droughts [

44,

45]. The effects of these hazards are experienced by both children and adults. Children have had limited opportunities to add their voices to decisions that will inevitably affect them in the present and the future. Including their voices through their art expressions and manifestos is, therefore, important. Educators and policymakers have been receptive to the goals of the project.

While preparing documents for the Nigeria ethical review process, it became apparent that there was no existing comprehensive art-for-climate-action training guide for facilitators or educators. The development of a training guide that could be useful across other nations and for other researchers interested in implementing art-for-climate-action research was undertaken. The Nigerian team drafted the guide and members from the wider team provided input, emphasizing the co-creation model of this collaboration and creating a new resource piloted in Nigeria. The project has now successfully held its first Art for Action event, bringing children and educators from their schools and policymakers together in a prestigious and safe space, aimed at informing those in government of the views of local children.

6.5. Project Lead in Scotland: Catriona Willis, Co-Ordinator of Highland One World Global Learning Centre

Highland One World Global Learning Centre works with schools across the Highlands, supporting children and young people in taking creative action on climate issues that matter to them. The Highland Council Educational Psychology team have shown that the climate emergency is a source of anxiety for many young people. Through our

Art for Action project, we aimed to cultivate a ‘pedagogy of hope’ [

46] that promoted agency and belief in a better future.

We provided schools with resources to explore COP 29, climate justice, and the use of art to drive social and environmental change. These materials incorporated active, participatory Global Citizenship approaches that went beyond learning about climate issues, to developing the values and skills needed to effect positive change. Learners developed climate ‘artivism’ projects to raise awareness and call for action on their chosen issue. At the heart of the project was ensuring young people had a voice on issues affecting them and access to spaces where decision-makers would listen. Artworks were displayed at the Highland Council Chambers in Inverness during COP 29, and later at Inverness Botanical Gardens. The latter included a stakeholder event attended by Members of the UK Parliament, Members of the Scottish Parliament, local councillors, business leaders, and members of the third sector. A Tree of Change captured pledges for action inspired by the exhibition.

Over 600 children and young people from 17 schools created artworks expressing their visions for change, and 110 people took part in the stakeholder event. The artworks will continue to be shared through a permanent online exhibition, extending their reach further. Young people did not just learn about climate issues and create art, they also took a stand, made their voices heard, and sparked important conversations, all while developing core values and skills of Global Citizenship.

6.6. Internal Methodological Lead and Partner to the Nigerian Project Lead: Margaret, Researcher in International Education, the Open University, UK

The SHowED cards (

Figure 5) represent a co-developed participatory tool designed to support critical reflection, creative expression, and action-oriented dialogue among children and young people. Adapted from the photovoice methodology pioneered by Caroline Wang, SHowED was originally developed to empower marginalized communities through photography and narrative-based enquiry [

47]. In this project, the tool has been recontextualised to build on work in the Lake Chad region [

48]. Young people’s voices, deeply rooted in socio-emotional and environmental challenges, produced multimodal outputs that served as powerful platforms for engagement with local, regional, and national stakeholders [

49]. These child-led engagements not only illuminated the lived realities of those navigating intersecting crises of conflict and climate disruption but also catalyzed critical conversations.

SHowED questions support a structured, child-led reflection process that moves from individual storytelling to collective action. In the current iteration of our

Art for Action project, the cards are used not only to prompt individual reflection during art-making workshops but also to scaffold shared learning among peers. Young people are invited to narrate what they see and feel in their artwork, linking it to broader social and environmental issues. Finally, the tool prompts action planning, encouraging children to design solutions such as community murals, performances, and advocacy messages. This layered use of SHowED transforms children’s creative outputs into catalysts for critical consciousness and civic agency, aligning closely with our project’s commitment to its eight principles (

Figure 3).

6.7. Internal Methodological Lead and Project Design Member: Carolyn Cooke, Scotland-Based Senior Lecturer and Staff Tutor, the Open University, UK

As a former music teacher, I have had a long-standing interest in what arts (in their broadest sense) can do beyond being a tool to demonstrate learning outcomes for assessment. I began to explore what happened when we, as a group of music students, walked to learn, or played with water sounds, or visited the zoology museum. What were the connections, the different perspectives this could give about education and learning, about what sounds, visuals, and emotional responses could do to change thinking and doing?

These explorations led to me working with posthumanist theories, which challenge human exceptionalism and power over materials, bodies, and the environment. I started interacting with sustainability and climate change issues. Bringing these threads of the arts, experiential learning, and posthumanism into this project, I have particularly drawn on Donna Haraway’s work around multi-species kinships [

38] and Ingold’s writings on correspondence and attentionality [

50,

51]. These have directly influenced the development of the underpinning principles of the project, recognizing the importance of attentionality, and correspondence between people and environments in creating action. This has influenced our thinking about the artworks as ‘doings’, whereby they are performative participants in the exhibitions, not merely representations of the children and young people’s learning. This led to the development of the SHowED postcards (

Figure 5) as an active response between exhibition attendees and the artworks, making connections between their emotions, ideas, and the generation of actions as a result of their engagement. In developing an analytical approach, again, the centering of the artworks as active participants in the project enables understanding of the role they have played in communicating with and between young people, communities, and policymakers.

6.8. Internal Data Management Lead and Project Design Member: Alison Glover, Wales-Based Research Fellow, the Open University, UK

My contributions to the development of this project were influenced by the impact of being in Wales (UK), teaching in Welsh schools and universities, and researching sustainability-related topics. Embedding Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship has gained traction in Wales since 2004, with sustainability a central organizing principle for public bodies, culminating in well-being goals passing into law in 2015. Recent changes to the school curriculum require learners to become ethically informed citizens of Wales and the world. Integral to this is creative and critical thinking, authentic learning experiences, and empowering learners to take ownership of their own learning. Taking all of this into account, contributing to this project offered a perfect opportunity to support an activity enabling young people to be heard.

We aspired that the research instruments and the data management approach adopted should be suitable for all partners’ situations. Negotiations involved how best to ensure research tools were clear and accessible in each setting and creating multiple formats of the confidence tool in response to feedback and preferences, adapting the participant information and consent forms for Nigeria and Kenya as well as offering Shona-translations of documentation in Kenya. Adaptations needed to retain a high level of consistency to allow for fair comparison of data across locations. Whether this has been as effective as hoped, is yet to be discovered. Ongoing partner feedback has been crucial to the development of the tools and processes. Throughout, it has been imperative to retain the individuality of each partner’s situation within the overarching aim to enable young people’s voices to be heard.

6.9. Illustration of the Principles in Action

Even though the viewpoints written by the adults involved in the project partnership presented above are relatively short, between them all eight principles of

Art for Action (

Figure 3) are evident. For instance, the youth game designer and project lead from Kenya reflect on how gaming offers opportunity for engagement with a different mode of artistic expression, and that the young people also made meaningful connections between their own environment and real global concerns. The facilitation of dialogue between communities and generations is also clear, with climate adaptation strategies created together. From the views of the adults from Scotland, it is apparent that the young people are expressing themselves effectively through their ‘artivism’; they have agency now, and other artistic modes such as song are also used. Meaningful engagement with materials is noted as the young people in Scotland developed values and skills to support future positive change. Links to local environment are also prominent and the opportunity for dialogue between generations evident, with the children conversing with politicians at the forefront of the Scottish activities. The ongoing exhibitions offer a legacy for community activism in Scotland too. In the Nigerian example, the impact of making connections between their local environment and climate change is highlighted, and the project provides a platform for young people to express themselves using a range of different outputs. The young people have been able to engage with others effectively and create a legacy with the locally created resources now available for use with more groups. The application of SHowED cards (

Figure 5) also demonstrates the different elements of the process from the making to the final output and impact. The reflections from other members of the project team in the UK also highlight the importance of local to global connections with regard to climate change, and the significance of facilitating expression through artivism that is enabling young voices to be heard.

7. Discussion

Setting up the conditions for children and young people’s agency to express their ideas to secure a more sustainable future has involved recognizing that their voices are silenced in mainstream societies. Children and young people’s direct engagement with their leaders and communities in various settings demands greater equity in the solutions to the climate emergency, and hence climate justice. These demands require us to be hyper-local in our engagement with them, their communities, the leaders and policymakers.

Facilitating shared spaces with adults who are in positions of community, regional or national, commercial or political leadership should be an outlet for frustrations from being excluded from solution-making. In Scotland, these shared spaces have extended to what we as partners facilitated in an exhibition into council and government spaces, to which children and their artefacts were invited. In Kenya, community hubs led by young people are envisaged, and in Nigeria, community murals and performances are planned. Part of the messages we have already seen from young people to the older generation are that societies should take a more ecotistical rather than egotistical view [

38], and they illustrate how to go about that through their acts of artivism.

We moved as a project to avoid reference to the climate situation as a ‘crisis’ to one of an ‘emergency’, as all parts of the team are conscious of not contributing further to eco-anxiety. Our application of sustainable pedagogies is articulated through participatory research. The project does not dictate content but offers varied tools to explore the meanings young people incorporated into the ‘making’ of their ‘doings’. We piloted variants of our confidence quiz (as a physical board, digital Jamboard, and survey) to capture how young people feel about their role in climate action, SHowED postcards (as physical invitations to write or mark make in response to artefacts), and climate conversations (with makers and artivism audiences, exploring the impact of engaging with the materials and their influence on actions). These tools were viewed as forms of ‘matter’, to try and tease out ways of joining the entanglements of young people with materials and with adults. A rich variety of artistic acts, voicing through objects and making processes, have allowed different global, local, and personal stories to emerge and be shared.

The project shows children and young people embrace writing lyrics and performing, mark-making, sculpting, and collaging and designing games to express themselves. They reappropriate natural objects, musical genres, fabrics, and waste materials to make bold, demanding, and engaging artivist artefacts. Children and young people can show us, the older generation, that “It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with… It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories” [

38] (p. 12). The younger generation needs societies to uphold their rights to be included, heard, and to express themselves.

8. Concluding Thoughts

This partnership of higher education and third-sector organizations, working with schools and the youth sector, has taken on the project of working out how to enact a pedagogy of hope [

46] through creating spaces to advocate children and young people’s views of and for a sustainable future. Instead of relaying their voices, adults have been creating facilitated spaces which open doors for children and young people to speak for themselves with their calls for action. Shared peer and intergenerational spaces are needed to imagine solutions and move beyond stories and lived experience. We are currently co-investigating with these children and young people on what their manifestos for change should look like, in our continued mission to support, under articles 12 and 13 of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child [

7].

We contribute to the field of sustainability education how adults can invoke posthumanist principles to reduce power imbalances, reject the exceptional position of humans in society and embrace the complexity and entanglements this stance reveals. We call for this move towards working equitably with one another and the environment, and how conditions need to be created, within and beyond the formal curriculum, for children and young people to access their heritage, their local culture, its languages, their natural environment, and local materials. We highlight firstly that, to enable these young people to act as global citizens, adults should facilitate their makings and doings as ‘hyper-local’. Secondly, supporting them to be creative by embracing the widest view of the arts, including game design, enables their views to be authentically expressed. Thirdly, facilitating spaces for the results of young people’s makings to be taken provides the opportunity for their calls for action to be heard and integrated into a society’s climate solutions—whether in person, through their artefacts, or through recordings. Meeting with and speaking directly to those in society who can make the changes they see as necessary to working towards a net zero future can and should be arranged.

8.1. Lessons for Practice

We believe pedagogical ways forward need to be intergenerational, intra- and intercultural using multilingual and multimedia tools for young people to help us, as adults, drive change. If we listen, we can hear the children and young people calling for us to show climate justice—to identify whose voices are being heard and who is being silenced—including theirs. As with their Inushak exhibit, children and young people remind us to learn from ‘‘Strong, silent, stoic figures much like indigenous peoples across the globe.” They are calling for us to help them learn from other cultures less affected by capitalism, also advocated in Experimental Pedagogies or Pedagogies of Collapse [

52]. The children in Scotland demand that it is time to HEAR voices other than our own, “to LEARN from those most connected to the land and SUPPORT those least to blame for the crisis”. As active but marginalized global citizens, they are calling us—expecting us—as adults to draw on our care and compassion for others, both local and global, in our educational practices, and indeed beyond, into our own lives as citizens, to lead global responses to climate emergencies.

8.2. Future Direction for Research

Our research continues to capture these entanglements through evidence-gathering along our journey as a reflexive account, to identify limitations in our approach and to guide future research. We appreciate that, so far, we have only been providing the modes and means for young people’s voices to be heard in policy spaces. The next steps are to show commitment to providing them agency in taking the lead in the research itself. The team members are currently setting up workshops with children and young people who have participated in Art for Action in each of the three settings as advisory groups to invite them to steer in the next phases of research. We have applied for external funding in which we will invest in building the next phases of research as child-led, accepting that this is not straightforward [

53] and will require an iterative dialogue with children and young people, and those who are supporting them, within their respective unique contexts.

Author Contributions

All authors are acknowledged in alphabetical order of their surname in respect with the democratic approach taken to the partnership work being reported in the article. Conceptualization, I.A., D.A.-O., G.B., C.C., M.E., A.F., A.G., L.M.W., C.W.; Methodology, I.A., D.A.-O., G.B., C.C., M.E., A.F., A.G., L.M.W., C.W.; Software (project website), C.C., M.E., A.F., A.G.; Validation, D.A.-O., L.M.W., C.W.; Formal analysis, I.A., G.B., C.C., A.F., A.G.; Investigation (fieldwork), D.A.-O., G.B., C.C., M.E., A.F., L.M.W., C.W.; Resources (research tools), I.A., D.A.-O., G.B., C.C., M.E., A.F., A.G., L.M.W., C.W.; Data curation, I.A., D.A.-O., G.B., C.C., A.F., L.M.W., C.W.; Writing—original draft preparation, I.A., D.A.-O., G.B., C.C., M.E., A.F., A.G., L.M.W., C.W.; writing—review and editing, I.A., G.B., C.C., A.F., A.G.; Supervision, D.A.-O., L.M.W.; Funding acquisition, A.F., L.M.W., C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Open University element of this research provided Open Societal Challenges internal funding (OSC-181) to partners in Nigeria and Kenya. Highland One World was also funded by the Pebble Trust (Scottish charity number SC044593) to deliver the Art for Action project in Scotland. The Climate Games Project of the AAYMCAs has also been funded by Brot für die welt (Bread for the World)—a development and relief agency of the Protestant Churches in Germany, as well as The YMCA of the USA (Implementation in Kenya and Zimbabwe) and The Forest Steward Council (FSC) (Implementation in Naivasha, Kenya).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Open University (HREC0693-Fox/30 December 2024), the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Ethics Committee of the University of Ibadan, Nigeria (UISSSHREC2025017/approved 6 February 2025), Amref Global Africa, Kenya P1881-2025, approved 12 June 2025 and NACOSTI/P/25/4177362, approved 29 July 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from those named in this article for the content included and how they wish to be recognized.

Data Availability Statement

There is a commitment for all original data presented in this study to be openly available via ORDO [

https://ordo.open.ac.uk/].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gaynor Henry-Edwards for supporting the administrative processes of this project and to the anonymous reviewers for valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAYMCA | African Alliance of YMCAs, formerly called: Young Men’s Christian Association |

| UN | United Nations |

| COP | Conference of Parties |

| SHowED | See, Happen, Our lives, Why and Do (in response to artefacts) |

| NACOSTI | National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation |

| ORDO | Open Research Database Online |

References

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Newsome, T.M.; Barnard, P.; Moomaw, W.R. World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. BioScience 2020, 70, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Selboe, E.; Hayward, B.M. Exploring youth activism on climate change: Dutiful, disruptive and dangerous dissent. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Seballos, F. Action research with children: Lessons from tackling disasters and climate change. IDS Bull. 2012, 43, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; Van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Plan. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelderman, G. To Be Alive in the World Right Now: Climate Grief in Young Climate Organizers. Master’s Thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2022. Available online: https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/1d89dee5-0a05-4a62-9e7b-61f40944ea3f (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Sporre, K. Young people–citizens in times of climate change? A childist approach to human responsibility. HTS Teol. Stud. /Theol. Stud. 2021, 77, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Treaty no. 27531. In United Nations Treaty Series; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 1577, pp. 3–178. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1990/09/19900902%2003-14%20AM/Ch_IV_11p.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Robinson, C. Lost in translation: The reality of implementing children’s right to be heard. J. Brit. Acad. 2021, 8, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, J.K.; O’Kane, C. Questioning children’s activism: What is new or old in theory and practice? Child. Soc. 2024, 38, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCCC. Informal Summary Report of the Expert Dialogue on the Disproportionate Impacts of Climate Change on Children and Relevant Policy Solutions; United Nations: Bonn, Germany, 2024. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/640922 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Jordan, J. Artivism: Injecting Imagination into Degrowth. 2016. Available online: https://degrowth.info/blog/artivism-injecting-imagination-into-degrowth (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Alonso-Fradejas, A.; Barnes, J.; Jacobs, R. Introducing: The Artivism review series. J. Peas. Stud. 2022, 49, 1331–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D. Looking to the future? Including children, young people and future generations in deliberations on climate action: Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly 2016–2018. Innov. Europ. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 34, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Parsons, K.J.; Halstead, F.; Wolstenholme, J.M. Reimaging activism to save the planet: Using transdisciplinary and participatory methodologies to support collective youth action. Child. Soc. 2023, 38, 823–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidotti, R. Posthuman Humanities. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozaleck, V.; Bayat, A.; Gachago, D.; Motala, S.; Mitchell, V. A Pedagogy of Response-ability. In Socially Just Pedagogies—Posthumanist, Feminist and Materialist Perspectives in Higher Education; Bozaleck, V., Braidotti, R., Shefer, T., Zembylas, M., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2018; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, D.F.; Stevenson, K.T.; Nils Peterson, M.; Carrier, S.J.; Renee Strnad, R.; Seekamp, E. Intergenerational learning: Are children key in spurring climate action? Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 53, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North American Association for Environmental Education. Guidelines for Excellence—Community Engagement; NAAEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Available online: https://dg56ycbvljkqr.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/eepro-post-files/community_engagement_guidelines.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Valdez, R.X.; Nils Peterson, M.; Stevenson, K.T. How communication with teachers, family and friends contributes to predicting climate change behaviour among adolescents. Environ. Conser. 2017, 45, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Vision. Learning to See the Climate Crisis Children and Young People’s Perceptions of Climate Change and Environmental Transformation in Albania, 2023, Albania. Available online: https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/Climate%20Change%20Research_Albania_FS%20edit_clean_final%20pdf.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Da Silva, N.M.; da Silva, S.M. What can I do for my community? Contributing to the promotion of civic engagement through participatory methodologies: The case of young people from border regions of mainland Portugal. Child. Soc. 2023, 38, 892–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facer, K.; Enright, B. Creating Living Knowledge: The Connected Communities Programme, Community-University Partnerships and the Participatory Turn in the Production of Knowledge. Arts and Humanities Research Council, UK, 2016. Available online: https://connected-communities.org/index.php/creating-living-knowledge-report/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Lee, K.; Gjersoe, N.; O’Neill, S.; Barnett, J. Youth perceptions of climate change: A narrative synthesis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2020, 11, e641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, J.V.; Geddes, A.; Gagnon, A.S.; Burnett, K.A. Participation and co-production in climate adaptation: Scope and limits identified from a meta-method review of research with European coastal communities. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2024, 15, e880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoli, A.; Glover, A.; Fox, A.; Cooke, C.; Lee, C.; Dewberry, E.; Burnside, G. Sustainable Pedagogies. Online Course. 2024. Available online: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/section.php?id=198868 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- The TRUST Code—A Global Code of Conduct for Equitable Research Partnerships. 2022. Available online: https://www.globalcodeofconduct.org/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Trott, C.D. What difference does it make? Exploring the transformative potential of everyday climate crisis activism by children and youth. Child. Geograp. 2021, 19, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raatikainen, K.J.; Juhola, K.; Huhmarniemi, M.; Peña-Lagos, H. “Face the cow”: Reconnecting to nature and increasing capacities for pro-environmental agency. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneller, A.J.; Harrison, L.M.; Adelman, J.; Post, S. Outcomes of art-based environmental education in the Hudson River Watershed. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2009, 20, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, I.R.; Lawson, M.A.; Matewos, A.M. Through the eyes of a child: Exploring and engaging elementary students’ climate conceptions through photovoice. Educ. Develop. Psych. 2022, 39, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Comley, S. Games-Based Techniques and Collaborative Learning between Arts Students in Higher Education. Doctoral Dissertation, University of the Arts London, London, UK, Falmouth University, Cornwall, UK, 2020. Available online: https://repository.falmouth.ac.uk/4794/1/COMLEY%2C%20S_final%20thesis.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Brooks, E.; Sjöberg, J. Evolving playful and creative activities when school children develop game-based designs. In International Conference on ArtsIT, Interactivity and Game Creation, Proceedings of the 7th EAI International Conference, ArtsIT 2018, and 3rd EAI International Conference, DLI 2018, ICTCC 2018, Braga, Portugal, 24–26 October 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouariachi, T.; Olvera-Lobo, M.D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J.; Maibach, E. A framework for climate change engagement through video games. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, C.; Robertson, J. Children as Game Designers: New Narrative Opportunities. In Virtual Literacies; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 142–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tramonti, M.; Dochshanov, A.M.; Fiadotau, M.; Grönlund, M.; Callaghan, P.; Ailincai, A.; Delle Donne, E. Game on for climate action: Big game delivers engaging STEM learning. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammen, L.; Meissner, M. Social movements’ transformative climate change communication: Extinction rebellion’s artivism. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2022, 23, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegarth, R. Just Kids: Youth Activism and Rhetorical Agency; The Ohio State University Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C.A.; Hughes, C. Posthuman Research Practices in Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, R. Posthuman Knowledge (Volume 2); Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lupinacci, J. Addressing 21st century challenges in education: An ecocritical conceptual framework toward an ecotistical leadership in education. Impacting Educ. J. Transform. Prof. Pract. 2017, 2, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K.E.; Jónsson, O.P. Towards posthuman climate change education. J. Mor. Educ. 2024, 54, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, Ç.; Zampaki, N. Posthumanism for sustainability: A scoping review. J. Posthum. 2023, 3, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowookere, T.; Ayodele-Olajire, D. Transborder resource conflicts in a peri-urban area of Oyo State. J. Bord. Manag. 2023, 7, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ayodele-Olajire, D.; Olusola, A. A review of climate change trends and scenarios (2011–2021). In Current Directions in Water Scarcity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 7, pp. 545–560. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 1st ed.; Barr, R., Translator; 1992 original version; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.C. Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. J. Women’s Health 1999, 8, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanji, T.; Ebubedike, M.; Kunock, A.I.; Mala, A.; Hadiza, K.F.; Bourma, M.O.; Nwoye, A. A ‘Hidden’ Crisis-In-Crises: A Transformative Agenda ‘Boko-Haram and Education in the Countries of The Lake Chad Region Through Visual Narratives. 2024. Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/98978/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Sprague, N.L.; Zonnevylle, H.M.; Jackson Hall, L.; Williams, R.; Dains, H.; Liang, D.; Ekenga, C.C. Environmental health perceptions of urban youth from low-income communities: A qualitative photovoice study and framework. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 1832–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. The maze and the labyrinth: Walking, imagining and the education of attention. In Psychology and the Conduct of Everyday Life, 1st ed.; Schraube, E., Højholt, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. On human correspondence. J. R. Anthrop. Inst. 2016, 23, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servant-Miklos, G. Pedagogies of Collapse: A Hopeful Education for the End of the World as We Know It; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, N.P. Child-led research, children’s rights and childhood studies: A defence. Childhood 2021, 28, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).