Abstract

The entire ecology is obviously being significantly impacted by climate change. Its causes must be found and addressed before it can be prevented. Therefore, this research investigates the impact of Green Production Processes (GRPP), Technological Globalization (TGLO), Renewable Energy Consumption (RECN) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on ECOF (Ecological Footprint) in Turkey from 1990 to 2022 using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) and Frequency Domain Causality methods. The E-Views 12 statistical software was used for the ARDL analysis, while the STATA 17 software was used for the Frequency Domain Causality. The ARDL outcome in the long run showed that GRPP and GDP contribute to ECOF significantly, while TGLO and RECN reduce ECOF insignificantly. The implication of this is that GRPP and GDP lead to ecological degradation, while TGLO and RECN contribute to ecological quality negligibly. In the short run, TGLO reduces ECOF, while GDP increases ECOF. This means that TGLO drives ecological quality, while GDP reduces it. Furthermore, the outcome of the Frequency Domain Causality confirms that GRPP and TGLO Granger-cause ECOF in the short, medium and long term. RECN, on the other hand, only Granger-causes ECOF in the long run, while there is no causal relationship between GDP and ECOF. This study recommends stringent environmental policies and investments in clean energy technologies, such as renewable energy.

1. Introduction

Due to a great influence of human activities, the global economy is dealing with serious ecological issues, such as the depletion of resources, pollution of the air and water, and other types of environmental degradation [1]. Ref. [2] stated that pollution can be very harmful to the environment. According to the Global Footprint Network, human activities are about 75% greater than Earth’s carrying capacity [3]. This significant ecological effect has an array of wide-raging consequences for the health of the public, economic activities and the supply of energy [4]. Many countries have taken a variety of actions to preserve natural resources and lessen their ecological impact in response to these pressing concerns [5]. By adopting the Paris Climate Agreement, nearly every country has pledged to lower their carbon footprints.

There are different factors that can affect the quality of the environment. Some scholars suggest that urbanization plays a crucial role [5,6]. Others suggest that institutional quality [7,8], political stability [9,10] and financial development [9,11,12] all play important roles in fostering a high-quality environment. However, this research focuses on other factors such as economic expansion, sometimes called economic growth or GDP, Green Production Processes (GRPP), which encompass the use of environmental-related technologies in the production process, renewable energy consumption (RECN) and trade globalization (TGLO). These variables are very important because they largely determine whether Turkey will be able to achieve its Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target. In addition, the impact of these variables on the quality of the environment is extensively discussed in the literature review section.

The focus of this research is on Turkey because of the numerous capabilities and challenges that Turkey possesses. Turkey is a country that is growing quickly and is strategically located, intersecting Europe and Asia, where economic expansion, urbanization and globalization have accelerated in the past thirty years [13]. An urban population that is growing, an increasing demand for energy, changing patterns of trade and changing industrial structure all come together to make Turkey’s ecological path a model case for ecological footprint (ECOF)-based research. Turkey’s GHGs rose from 338 million tons of CO2 equivalent in 2005 to over 564 million tons in 2021 [14]. Turkey’s land, forest and water resources—essential elements of its ecological footprint—are increasingly under stress, despite the fact that CO2 is only one aspect of ecological pressure. Furthermore, at the COP29 climate summit, Turkey pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2053 and extend the use of clean energy [15]. Turkey also has a GDP size of USD 1.3 trillion and a population size of 85.5 million [16]. Therefore, this research investigates the impact of Green Production Processes (GRPP), Technological Globalization (TGLO), Renewable Energy Consumption (RECN) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on ECOF (Ecological Footprint) in Turkey from 1990 to 2022 using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) and Frequency Domain Causality methods.

What are some of the contributions of this research to existing studies?

- First, very limited studies have used Turkey as a case study, which necessitates future research.

- Second, while TGLO has received little attention, other forms of globalization notions, such as financial and social globalization [16,17], have been examined. Thus, the TGLO variable is used. Considering TGLO is significant because it shapes the global economy, influences domestic policies and has a direct impact on individuals and societies.

- Third, in addition to the ARDL approach, also utilized by existing studies such as [18,19], this research employed the Frequency Domain Causality approach to support the ARDL findings.

- Fourth, rather than using patent from residence and non–residence, this research uses a more captivating variable called GRPP to capture the ecological effects of green technologies. In addition, the use of this variable in existing literature is very scanty.

- Fifth, as a deviation from other studies, this research confirms that GRPP reduce the quality of the environment, while TGLO improves it.

- Lastly, rather than using CO2 as a proxy for ecological sustainability, this research uses ECOF because it is the sole indicator that contrasts the need for resources by people, governments and corporations with the ability of the planet to regenerate biologically [3]. It takes into account a variety of ecological factors, such as farmland, grazing land, forest area, carbon footprint, fishing grounds and built-up land.

2. Literature Review

2.1. GRPP and ECOF Association

For Pakistan, employing the NARDL, ref. [20] found that GRPP contribute to a quality environment. This means that GRPP reduce ECOF. For the ten biggest ECOF economies, ref. [21] discovered that GRPP reduce ECOF. Using economies that are green innovators as a case study, ref. [22] ascertained that the main cause of ecological deterioration is economic expansion. The study further showed that RECN moderates ECOF, and at the same time, GRPP contribute to ecological quality. In OECD economies, ref. [23] established that, in the long run, GRPP and ECOF are substantially correlated, according to all the methodologies employed. The CS–ARDL conclusion, however, suggests that GRPP’s short-term ecological impact is negligible. This outcome is justifiable because the implementation of green technologies is a lengthy process that requires significant financial outlays, and is fraught with uncertainties regarding a wide range of socioeconomic issues, including ecological laws and patterns of consumption. Ref. [24] opined that RECN and GRPP reduce ECOF. For Turkey, ref. [25] stated that GRPP improve the quality of the environment. The research also stated that this could contribute to a growth that is sustainable. For the top 10 Asian economies, ref. [26] found a bidirectional causal association between GRPP and ECOF. Ref. [27] argued that the adverse effects of human ecological actions could be lessened by GRPP and RECN. For example, clean energy sources like cars that are electric in nature, and solar and wind power have the potential to reduce dependency on fossils. The study further emphasized that, in order to prevent unforeseen negative effects, the implementation of these technologies must be carried out with extreme care, while keeping in mind the concept of sustainability.

2.2. TGLO and ECOF Association

In APEC economies, ref. [28] found that GLO can improve the environment. For Uruguay, ref. [19] revealed that TGLO contributes to the degradation of the environment. The methods used are the ARDL method and spectral causality test. For nuclear power economies, employing the CS–ARDL technique, ref. [29] argued that TGLO increases the ECOF, which drives up ecological costs. In terms of recommendation, the creation and execution of trade policies that are sustainable ought to be the primary focus of these chosen countries. Ref. [30] found no association between TGLO and the quality of the environment. Ref. [31] asserted that TGLO has a detrimental influence on sustainable development, although this effect diminishes as one moves from the 10th to 90th quantile. From G9 industrial economies, using MMQR and BSQR methodologies, ref. [32] found that TGLO, ICT and GDP increase ECOF. The study suggests that, in order to lessen the negative ecological effects of TGLO, more ecological laws and sustainable trade practices are crucial. For SAARC nations, ref. [33] established that GLO and GDP contribute to ecological degradation. According to [34], the relationship between GLO and the ECOF is complex, with both positive and negative effects. Ref. [35] asserted that GLO has a dual impact on SSA’s ecological results, lowering CO2 but also greatly expanding the ECOF. The study of [36] revealed that GLO and GDP greatly worsen the environment. On the other hand, RECN is linked to smaller ECOF, suggesting that they could be useful mitigating strategies. For the Turkish economy, ref. [37] also established that GLO spurs ecological degradation. Also for Turkey, ref. [38] asserts that TGLO improves the environment. The proxy used for the quality of the environment was the load capacity factor. Ref. [39] argued that the quality of the environment is improved via RECN and green production methods. Furthermore, TGLO has marginal favorable benefits for ecological quality, although economic expansion has a negative impact.

2.3. RECN and ECOF Association

For BRICS nations, ref. [40] revealed that RECN contributes to the quality of the environment. In addition, the EKC hypothesis was confirmed. In 120 economies, ref. [41] stated that, from the standpoint of various income brackets, RECN does not always reduce ECOF. More specifically, global clean energy boosts economic prosperity and the environment. In some selected oil-producing economies, ref. [42] established that, in contrast to clean energy, which neither causes nor impacts the ECOF, economic expansion has an impact on it. In addition, investments in clean energy are insufficient in oil-producing nations. In 36 OECD economies, ref. [43] opined that, in order to reduce the ecological impact and promote conservation of the environment, the development of clean energy is essential. The UK’s ECOF is greatly reduced by the effectiveness of clean energy research and development [44]. Ref. [45] argued that, although clean energy lowers ECOF, it does not completely stop environmental deterioration. The following studies also confirmed that RECN improves the environment, including [46] for the USA, [47] for Denmark, [36] for SSA economies, and [48] for China. The negative link between RECN and ECOF is further established for the Turkish economy [49,50,51].

2.4. GDP and ECOF Association

In Saudi Arabia, using the Simultaneous Equation Modeling, a bidirectional association between GDP and CO2 was established [52]. In BRICS, the adverse implication of GDP was confirmed by [53], while ref. [54] opined that, in the long run, GDP does not contribute to ecological progress. The ARDL and Driscoll–Kraay regressions were used, respectively. For the Turkish economy, employing the NARDL approach, ref. [55] found that GDP decreases ecological quality. Adopting the 2SLS and FGLS methods for developing economies, ref. [56] stated that high rates of economic expansion, a wealth of resources and significant foreign direct investment all contribute to environmental damage. Using the spectral Granger causality technique for the Indian economy, ref. [57] found that GDP hinders ecological quality. In East Asia and the Pacific, adopting the Quantile Regression technique, ref. [58] argued that GDP contributes positively to the quality of the environment. In the case of Somalia, ref. [59] confirmed the EKC hypothesis, suggesting that, at the beginning of a country’s development, not much emphasis is placed on the quality of the environment. However, as the country develops further, attention is given to how the environment turns out. The openness of trade was also found to be beneficial to the environment, while institutional quality was insignificant. In Japan, ref. [39] also established that GDP negatively impacts the environment. For the Turkish economy, ref. [60] used the load capacity factor to proxy for the quality of the environment, and found that GDP contributes to the degradation of the environment due to existing energy policies that drive economic activities.

2.5. Gap in the Literature

A number of important insights are brought to light by the literature review. Firstly, despite the fact that many studies have looked into the factors that influence ECOF, the results are frequently contradictory and highly dependent on context. Secondly, current studies offer diverse but disjointed viewpoints on the factors that determine ECOF by analyzing single countries and groups of economies. In addition, Turkey as a country has been under-researched in the investigated literature. Thirdly, econometric methods including MMQR, ARDL, NARDL, 2SLS, FGLS and DOLS have been frequently utilized in the investigated literature. Therefore, by using the Frequency Domain Causality Technique [19,57] in conjunction with the ARDL technique, this study expands the methodological terrain and offers an improved comprehension of the interactions between variables. Fourthly, other types of globalization concepts such as financial and social globalization have been considered, while trade globalization has been neglected. In addition, the role of GRPP has also been overlooked. Thus, this investigation fills this important gap by examining how TGLO and GRPP affect ECOF. It also adds new perspectives and advances the conversation on sustainable development.

3. Theoretical Framework, Data and Methodology

3.1. Theoretical Framework

The impact of GDP on ECOF is explained by the EKC hypothesis [61]. Early on, in the development process, ecological quality is adversely affected by the spike in economic expansion (this is called the “scale effect”). However, as the levels of income rise, people start requesting more environmentally friendly products. In addition, production techniques will also change to ecologically friendlier ones. At this point (known as the “composition and technical effects”), raising GDP spurs ecological quality [39,62]. GRPP, which incorporate environmentally friendly technologies and practices into industrial outputs, are essential to raising the quality of the environment [63]. It is important to state that the impact of GRPP on the environment can also be negative as suggested by [21]. Regarding the impact of TGLO on ECOF, two viewpoints surfaced. The “Pollution Halo Hypothesis” states that there is a positive correlation between TGLO and the quality of the environment, whereas the “Pollution Haven Hypothesis” states that there is an inverse correlation between TGLO and the quality of the environment. Thus, if TGLO is environmentally beneficial, it can improve the quality of the environment, and vice versa [64,65]. Furthermore, a large number of the studies investigated showed that RECN drives ecological quality.

3.2. Data

This research used data from 1990 to 2022. It is important to state that the study timeframe and sample size were limited by the lack of data. The variables employed include ECOF, GRPP, TGLO, RECN and GDP. ECOF is the dependent variable; GRPP, TGLO, RECN and GDP are the independent variables. In addition, to lessen heteroscedasticity, all of the study’s variables are converted to natural logs. Table 1 displays the sources and metrics for the variables of interest.

Table 1.

Variables employed.

Furthermore, based on the study of [40], the following represents the construction of the model for this study:

The descriptions of the variables ECOF, GRPP, TGLO, RECN and GDP are clearly stated in Table 1. However, the error term is denoted as . In terms of a priori expectation, and based on the investigated literature and theoretical framework, we project that GRPP can have a positive or an inverse link with ECOF (; TGLO can have a positive or negative association with ECOF (; RECN will have a negative association with ECOF (; the association between GDP and ECOF will be positive (.

3.3. Methodology

Firstly, this study employed the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) as postulated by [69]. This method examines the long- and short-term interconnection between variables, taking into consideration mixed stationarity conditions. This implies that the outcome of the unit root test can be I(0), I(1), or a combination of both. However, it should be stated that it is better for the dependent variable (ECOF) to be stationary at I(1) as recommended by [69]. One of the major advantages of using the ARDL approach is that it is suitable for sample sizes that are small, and helps to solve the problem of endogeneity [69,70,71]. The ARDL model is specified as follows:

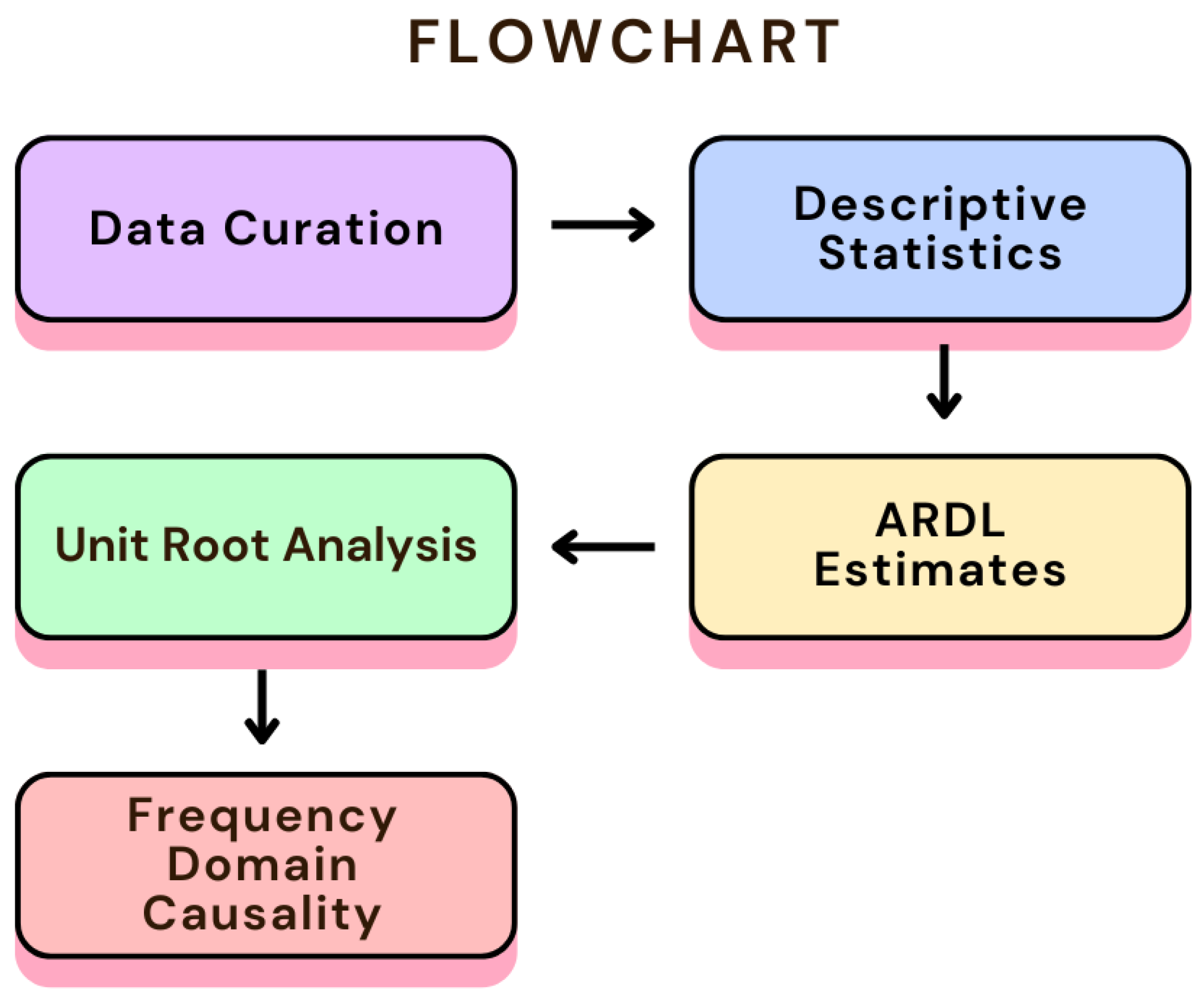

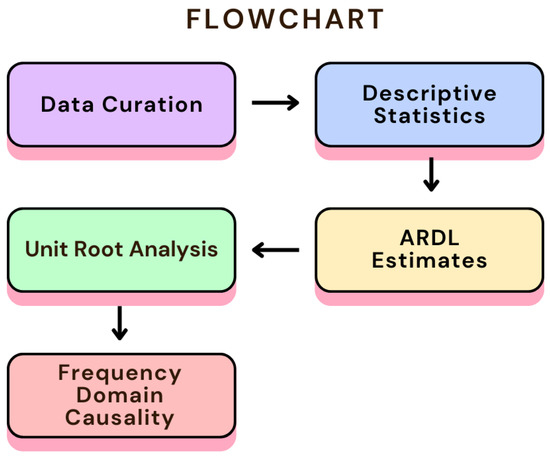

where – denote long-term parameters, – denote short-term parameters, and ECT is the Error Correction Term. In addition to the ARDL approach, the Frequency Domain Causality method [72] was also utilized as seen in the studies of [19,57]. This approach is also called spectral Granger causality. It reveals the extent of frequency domain evaluation, which may be used to find causative cycles and nonlinearity at both high and low frequencies. This method’s capacity to identify causal relationships between variables at various frequencies is one of its main advantages [19]. The analysis flowchart is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Analysis flowchart.

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

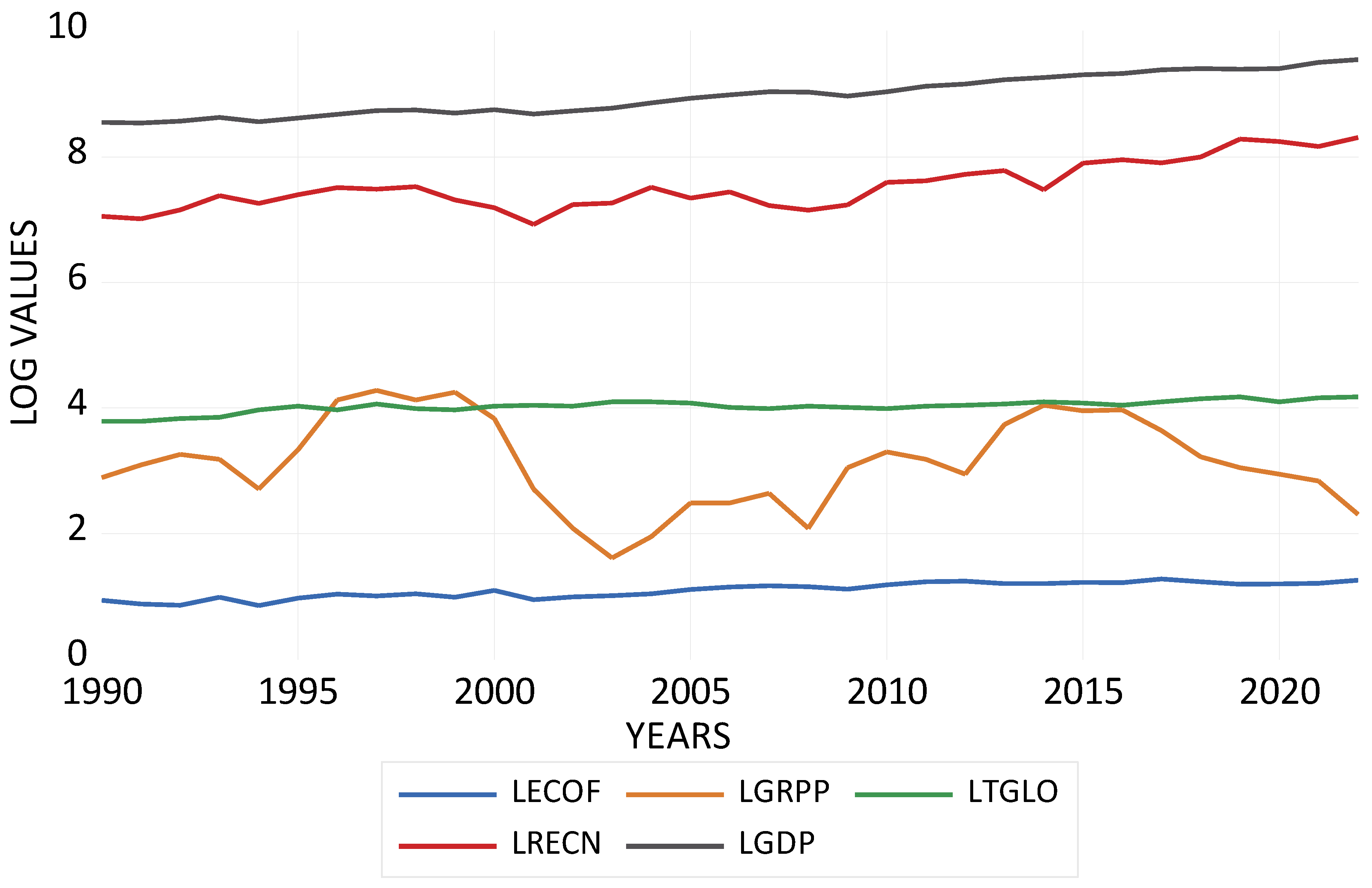

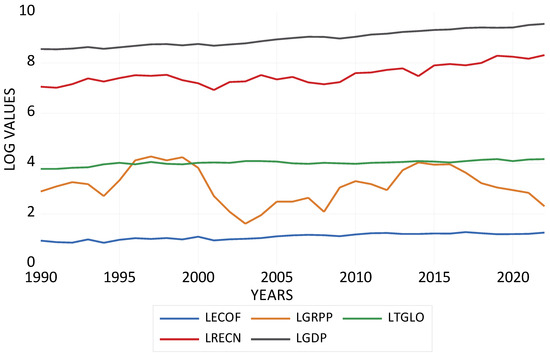

The descriptive statistics in Table 2 show how the variables in this study are distributed. From the table, it is evident that LGDP (8.975475) has the highest mean, followed by LRECN (7.531859). LGRPP (3.128587) has the lowest mean. Similar outcomes are also applicable to the median values. Regarding skewness, LECOF (−0.403777), LGRPP (−0.117692) and LTGLO (−0.935007) are negatively skewed, while LRECN (0.586829) and LGDP (0.247275) are positively skewed. Regarding kurtosis, LECOF (1.932604), LGRPP (2.256994), LRECN (2.374689) and LGDP (1.700906) are platykurtic. This is because the numerical values are less than 3. However, LTGLO (3.725477) is leptokurtic because the value is more than 3. Furthermore, the probability values of all variables are more than 5%, which signifies normal distribution. Figure 2 shows the descriptions of variables in a diagrammatic form.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Figure 2.

Graphical plot of variables.

4.2. Unit Root Analysis

In Table 3, the ADF [73] and PP [74] unit root tests are presented. The ADF result shows that LECOF, LGRPP, LTGLO, LRECN and LGDP are all stationary at I(1). Likewise, for the PP test, the result shows that LGRPP, LTGLO, LRECN and LGDP are stationary at I(1), while LECOF is stationary at I(0).

Table 3.

Unit root analysis.

4.3. Bounds Test

The bounds test in Table 4 demonstrates that a long-run link exists among the variables. This is because the F-stat. value is greater than the bounds of I(0) and I(1).

Table 4.

Bound test.

4.4. ARDL Long- and Short-Run Outcomes

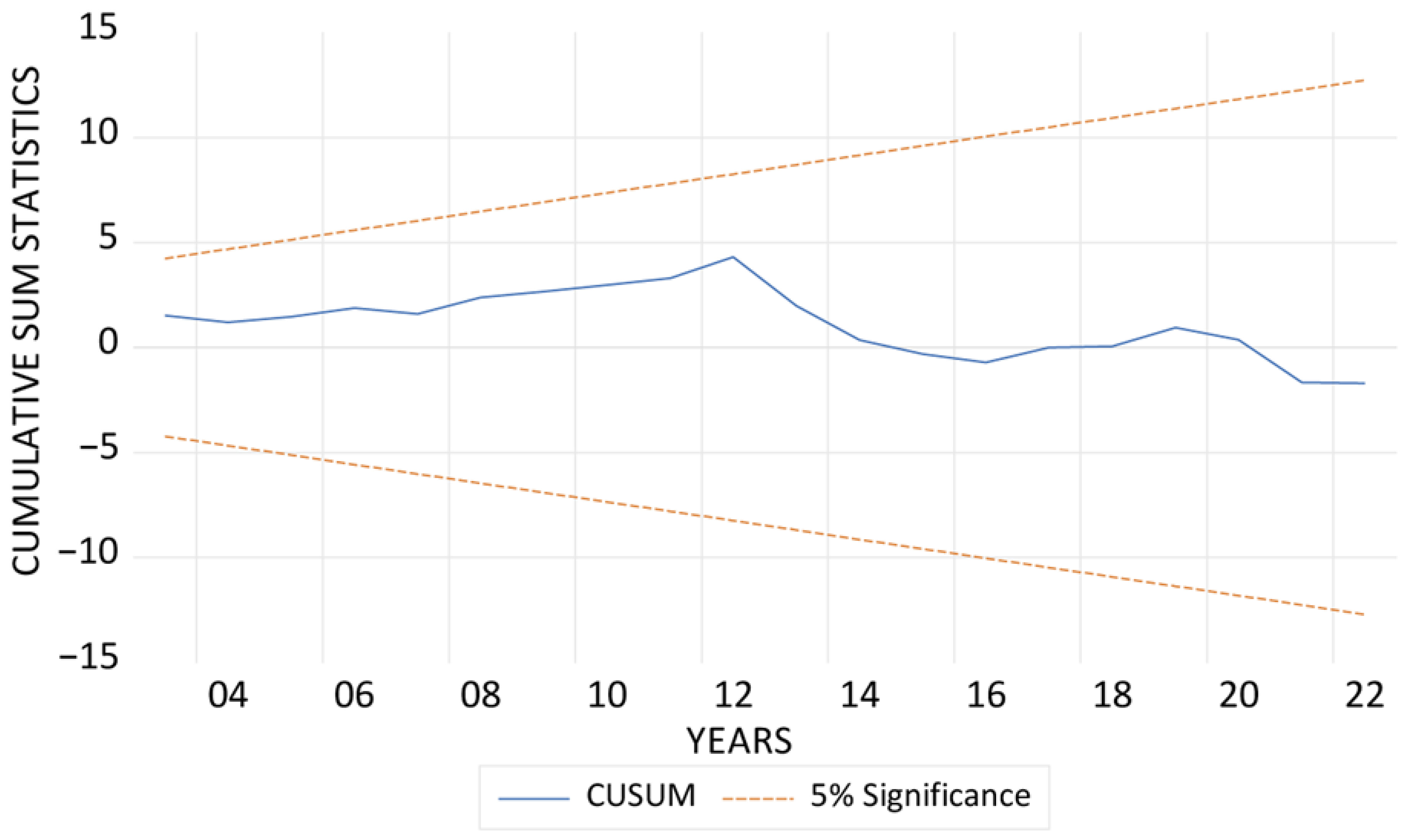

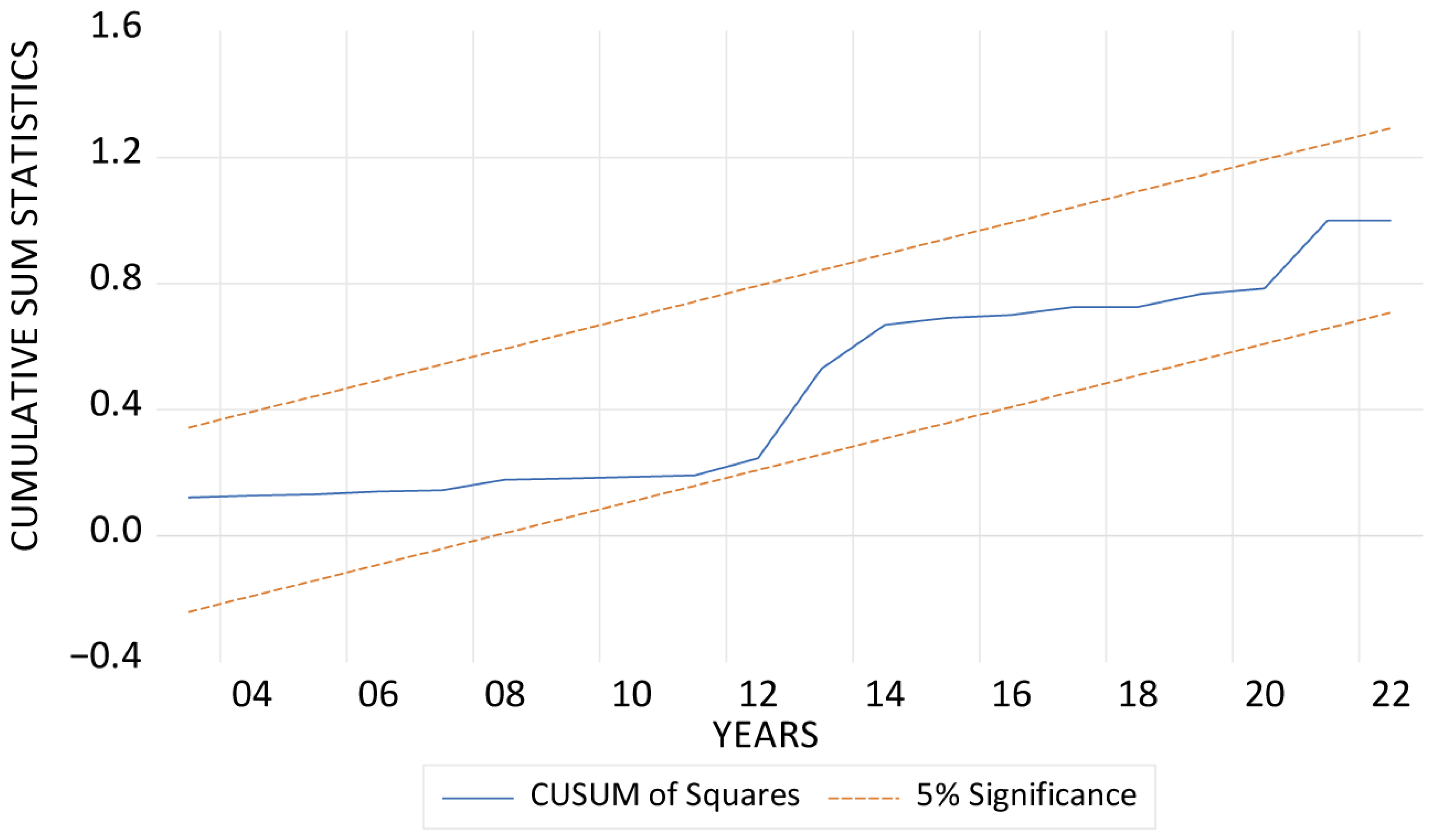

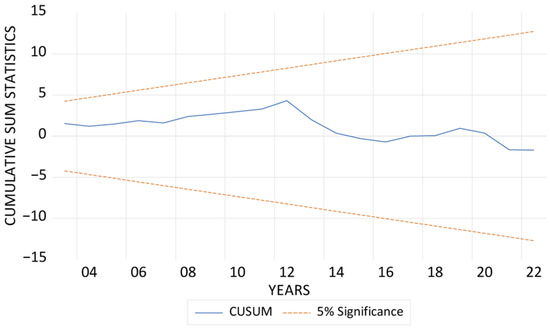

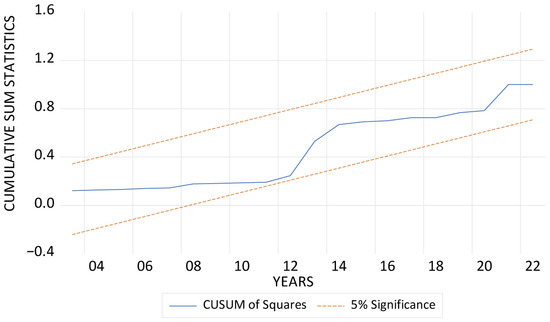

In Table 5, it is evident that the association between LGRPP and LECOF is positive in the long run. This means that LGRPP contributes to the degradation of the environment. Specifically, a 1% increase in LGRPP leads to a 0.02% increase in LECOF. Regarding the LTGLO and LECOF nexus, the relationship is negative and insignificant. This means that LTGLO contributes to the quality of the environment, although the impact is not significant. This, somewhat, in a way confirms the Pollution Halo Hypothesis. Furthermore, although insignificant, LRECN also reduces LECOF, implying that, as LRECN increases by 1%, LECOF decreases by 0.08%. Finally, LGDP contributes to the degradation of the environment. A 1% increase in LGDP spurs LECOF by 0.42%. In the short run, LTGLO reduces LECOF at no lag and at lag 2. More specifically, a 1% increase in LTGLO reduces LECOF by 0.43% and 0.25%, respectively. In addition, just like the long-run result, LGDP leads to a decline in the quality of the environment. A 1% increase in LGDP leads to a decline in the quality of the environment by 1.01%. In line with theoretical assumptions, the ECT is negative and significant. In detail, the ECT confirms that the economy will move back to equilibrium at an adjustment speed of 0.65%. The regressors account for 87% and 85% of the variance of LECOF, according to the R-squared and adjusted R-squared values, respectively. Based on the outcome of the diagnostic tests, our model is normally distributed and homoscedastic and has no serial correlation. Figure 3 shows the CUSUM and CUSUMQ, which confirm the stability of the model.

Table 5.

ARDL long- and short-run outcomes.

Figure 3.

CUSUM and CUSUM of squares.

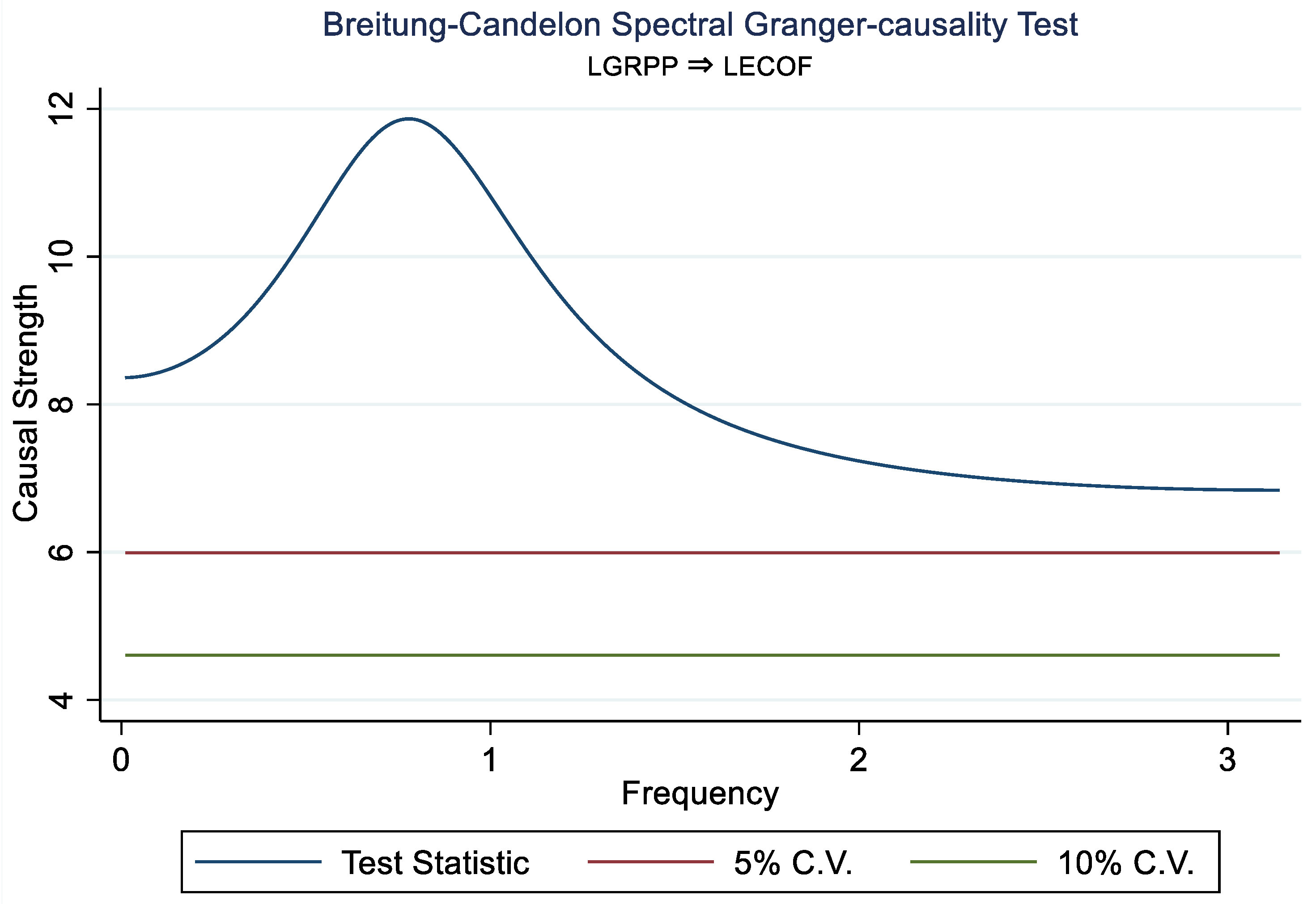

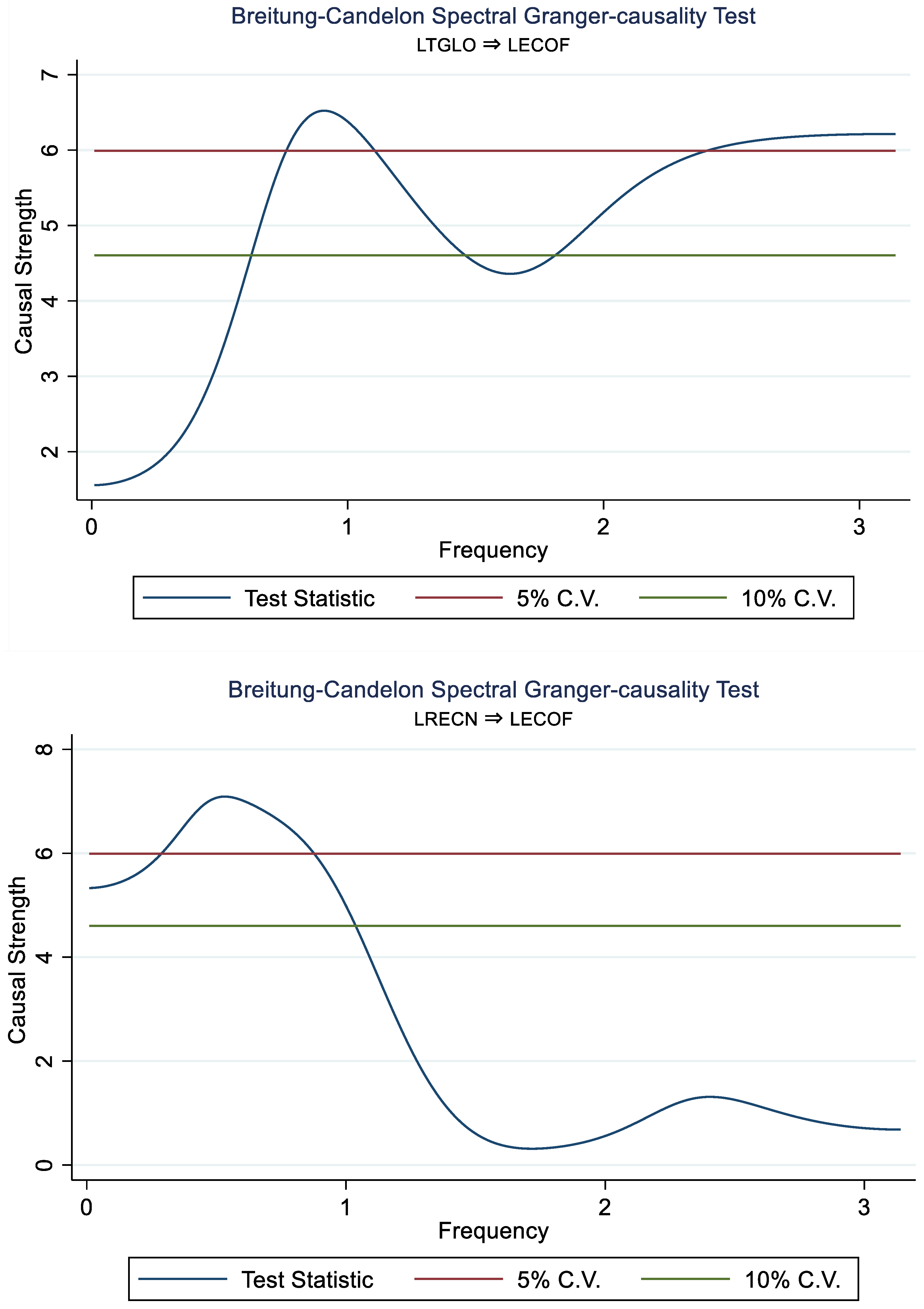

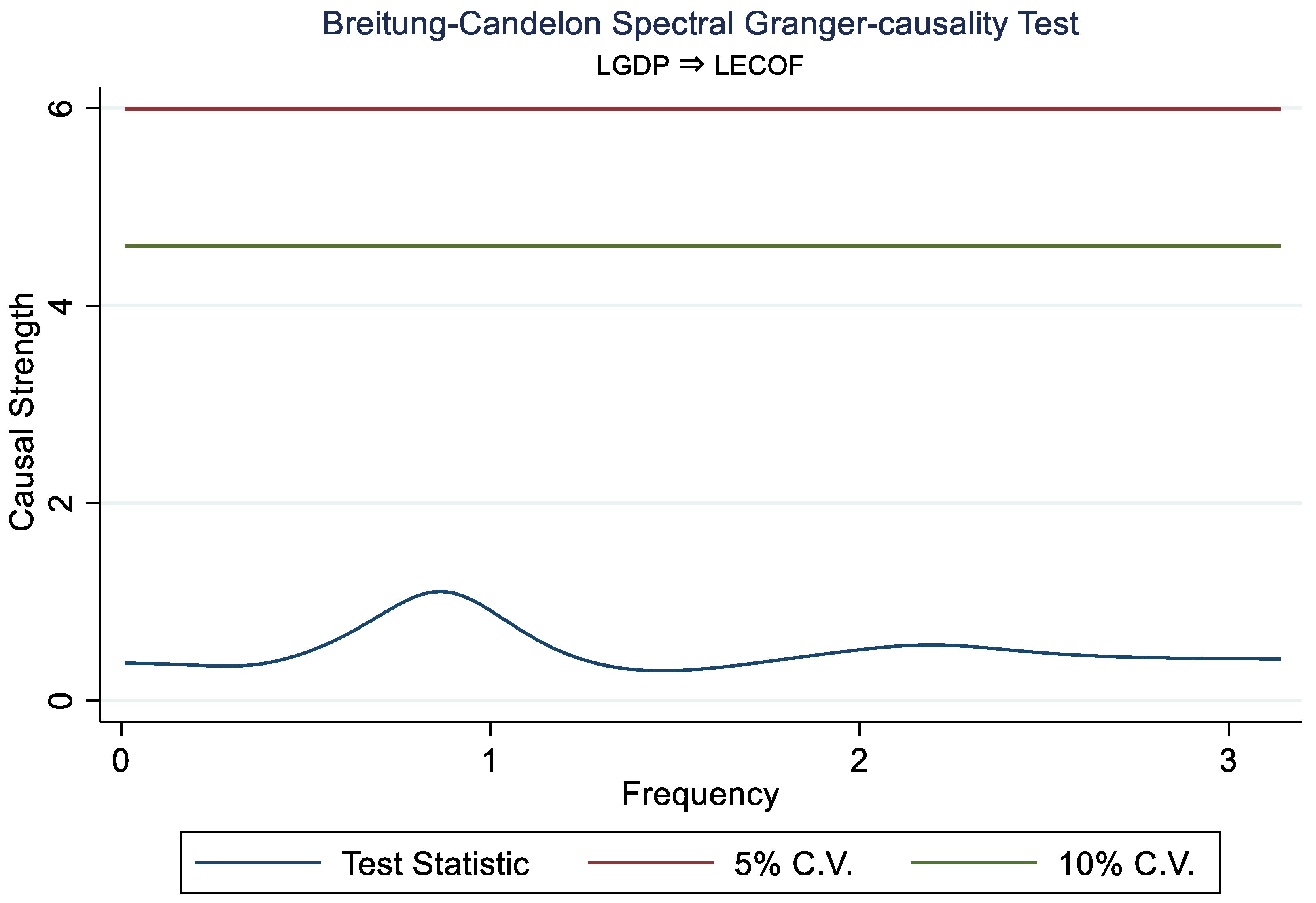

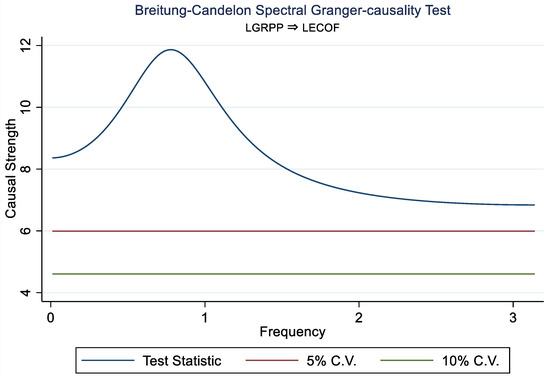

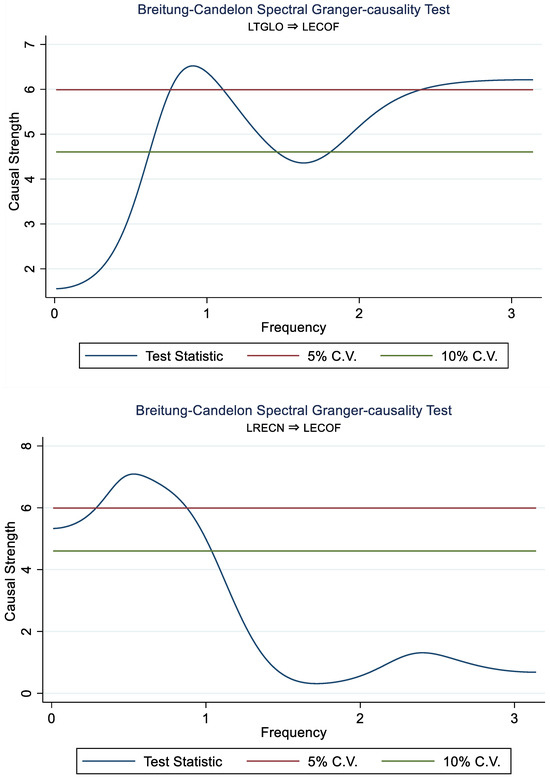

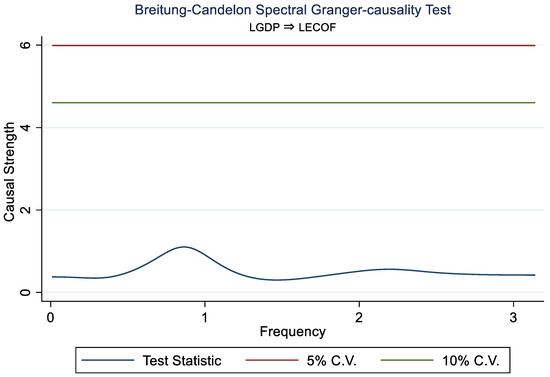

4.5. Frequency Domain Causality

In Figure 4, the Frequency Domain Causality confirms that LGRPP Granger-causes LECOF in the short, medium and long term. LTGLO also Granger-causes LECOF in the short, medium and long term. LRECN, on the other hand, only Granger-causes LECOF in the long run. The short- and medium-term effects are insignificant. Furthermore, there is no causal relationship between LGDP and LECOF. It is important to state that causation does not necessarily mean that there is a relationship. Causation shows that a change in one variable can lead to a change in another variable.

Figure 4.

Frequency domain causality.

4.6. Discussion

The majority of the studies confirm that GRPP spur ecological quality [21,23,27,39]. However, in this study, it is observed that GRPP increase ECOF in Turkey. One of the reasons that could be responsible for this outcome is weak environmental laws. While it is evident that environmental laws exist in Turkey, an absence of stringent oversight can lead to projects, including those using purportedly “green technologies”, being approved without sufficient ecological impact assessment. This can lead to water pollution, land degradation, a loss of habitats and air pollution. In addition, economic and political factors are also some contributors to this outcome. In the economic context, Turkey’s economic growth is a priority because of the ripple effect on the populace. In addition, it is becoming a global economy. As a result, industrial expansion will be prioritized above ecological protection. The economic context also relates to the Turkish government subsidizing fossils, making them more attractive at the expense of renewable technologies. From the political angle, ref. [55] opined that an essential metric for assessing Turkey’s ecological quality is political stability. For Turkey’s environmental sustainability to persist, the political tensions in the nation must be managed by politicians. Ref. [39] also found in their study that, in the early phases of putting green ideas into practice, GRPP might not instantly improve the quality of the environment. This could be due to large upfront costs, inefficiency, or a lack of developed technologies. This is also confirmed by [75,76]. Ref. [76] further asserted that GRPP will drive ecological degradation when it is relatively low. Ref. [77] explained the reasons more succinctly. They argued that, in Turkey, carbon footprint increases when ecological innovation falls below a certain threshold. Furthermore, this increment becomes more pronounced when the threshold is crossed. The findings essentially confirm the ecological rebound effect, highlighting the fact that, rather than lowering the carbon footprint, the benefits of ecological innovation typically result in increased production and consumption.

Secondly, our study found that TGLO reduces ECOF in both the long and short run, although the impact is not significant in the long run. This can be justified. Emerging economies like Turkey frequently experience short-term gains from TGLO but long-term stagnations in ecological sustainability. This can be explained by the relative intensity of the three main effects of trade: technique, composite, and scale effects. Since TGLO has a strong and instantaneous effect, due to the technique effect, it initially improves ecological sustainability. Over time, the composite and scale effect assume precedence. Greater output and consumption are the main drivers of the scale effect, whereas a nation’s industrial specialization following trade liberalization is the main driver of the composite effect. An industry’s competitive edge may determine its kind. Ref. [39] concluded that TGLO contributes to ecological quality when environmental performance is high. Ref. [38] confirmed that ecological quality might rise as TGLO increases, if export and product diversity, which is consistent with natural balance, increases. On the contrary, other studies confirmed that TGLO contributes to ECOF [29,31,32].

Regarding the RECN and ECOF nexus, the majority of the studies found a negative relationship [43,46,49,50,51], implying that RECN contributes to the quality of the environment. This clarifies that RECN can help lower ECOF in a clean way. By incorporating and developing clean energy technologies, Turkey is working on achieving its sustainable development goals [40]. Ref. [78] argued that there are many environmental benefits of using energy from renewable sources. It is unlimited in supply, supports sustainability, improves human health and is reusable, making it a resource that is replenishable. From an economic point of view, the production of clean energy could lead to more job opportunities and lower costs related to the negative health impacts of ecological pollution. However, it is essential to state that, in this study, a positive and insignificant association was found between RECN and ECOF. There are some justifiable reasons for this. Due to a substantial counter-effect from rapidly rising overall energy demand and steadfast pro-fossil fuel policies, clean energy has no long-term impact on alleviating environmental deterioration. Simply put, despite Turkey’s efforts to increase its renewable energy capacity, the country’s expanding and industrializing economy has such a huge energy demand that fossil fuels are used to provide enough energy.

Lastly, as expected, the link between GDP and ECOF is positive, implying that, as the economy grows, the quality of the environment declines. Both the short- and long-term trends point to Turkey’s propensity to accept and enjoy greater economic advantages at the expense of ecological quality. This result is expected given that most developing nations, including Turkey, have seen strong economic expansion over the past ten years, which has coincided with an increase in degradation of the environment. ECOF is increased when the corporate and household sectors rely too heavily on the use of fossils to meet their needs. It is in these conditions that the negative ecological effects of Turkey’s economic growth are confirmed. This outcome is affirmed by the following studies [39,57,60].

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

This research investigates the impact of Green Production Processes (GRPP), Technological Globalization (TGLO), Renewable Energy Consumption (RECN) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on ECOF (Ecological Footprint) in Turkey from 1990 to 2022 using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) and Frequency Domain Causality methods. The E-Views statistical software was used for the ARDL analysis, while the STATA software was used for the Frequency Domain Causality. The ARDL outcome in the long run showed that GRPP and GDP contribute to ECOF significantly, while TGLO and RECN reduce ECOF insignificantly. The implication of this is that GRPP and GDP lead to ecological degradation, while TGLO and RECN contribute to ecological quality negligibly. In the short run, TGLO reduces ECOF, while GDP increases ECOF. This means that TGLO drives ecological quality, while GDP reduces it. Furthermore, the outcome of the Frequency Domain Causality confirms that GRPP and TGLO Granger-cause ECOF in the short, medium and long term. RECN, on the other hand, only Granger-causes ECOF in the long run, while there is no causal relationship between GDP and ECOF.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the findings of this research, policies are recommended as follows:

- Firstly, to prevent the negative impact of GDP on the environment, Turkey should incorporate ecological considerations into its economic expansion policies from the outset. Policies such as environmental levies, incentives for green technologies, and support for sustainable companies are essential. With these steps, economic progress will be positively correlated with ecological sustainability, especially in the early stages of development. This highlights the necessity of Turkey undergoing a sustainable energy transition, wherein the nation’s energy needs are met by producing energy using clean energy resources. The authors of [29] stated that investors and businesses suffer financially because of environmental taxes. Businesses are likely to implement cutting-edge eco-friendly technologies to reduce their environmental impact and avoid these costs.

- Secondly, investments in solar (roof top solar panels for residential and commercial buildings), wind (onshore and offshore) and geothermal energy infrastructure (geothermal power plants) must be given top priority in Turkey. This shift can be sped up with the help of policy instruments including tax breaks for investments in clean energy, subsidies for clean energy projects and funding for renewable technology R&D. Increasing the use of clean energy would help Turkey achieve its carbon neutrality objectives by lowering its reliance on fossils and improving ecological integrity.

- Thirdly, Turkey needs to offer specific assistance to sectors implementing environmentally friendly technologies. This entails PPPs, grants for energy-saving tools, and technical support for carrying out practices that are sustainable. This will drive innovation in environmentally friendly processes. This will also hasten the shift to sustainable industrial practices.

- Fourthly, for the purpose of strategically coordinating ecological and trade strategies, Turkey ought to continue to foster the commerce of green technologies, impose more strict ecological regulations on imports and exports, and push enterprises to obtain international environmental certifications. Turkey can guarantee that globalization promotes ecological quality and sustainable development by coordinating trade policy with environmental objectives. In addition, this coordination can occur if it is examined from the perceptive of green industrial policy, aligning its SDGs with the EU’s Green Deal. It is important to note that the EU is Turkey’s largest trading partner.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

Although this research has made a significant addition to ecological literature, especially in Turkey, it has a number of shortcomings. These shortcomings result from the study’s limited use of parameters and unavailable data. Future studies might include other parameters and examine how they affect different environmental measures. More specifically, variables such as urbanization, institutional quality and political stability can be included in further studies. In addition, a nonlinear technique may also be used in future research to ascertain the impact of the factors under investigation.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written by M.A.A. and supervised by W.M.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2SLS | Two-Stage Least Squares |

| BSQR | Bootstrap Quantile Regression |

| CS–ARDL | Cross-Sectional–Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide Emissions |

| DOLS | Dynamic Ordinary Least Square |

| EKC | Environmental Kuznets Curve |

| EU | European Union |

| FGLS | Feasible Least Squares Generalized |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GFN | Global Footprint Network |

| GLO | Globalization |

| GRPP | Green Production Process |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| MMQR | Methods of Moment Quantile Regression |

| NARDL | Nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| OWD | Our World in Data |

| PPP | Public–Private Partnership |

References

- Soto, G.H.; Martinez-Cobas, X. Nuclear energy generation’s impact on the CO2 emissions and ecological footprint among European Union countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 173844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Qin, S.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Fan, B.; Jin, Y. Study on the Hg0 removal characteristics and synergistic mechanism of iron-based modified biochar doped with multiple metals. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 332, 125086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GFN. Global Footprint Network. 2025. Available online: https://data.footprintnetwork.org/#/countryTrends?cn=223&type=BCpc,EFCpc (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Numan, U.; Ma, B.; Sadiq, M.; Bedru, H.D.; Jiang, C. The role of green finance in mitigating environmental degradation: Empirical evidence and policy implications from complex economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 400, 136693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakher, H.A.; Ahmed, Z.; Acheampong, A.O.; Nathaniel, S.P. Renewable energy, nonrenewable energy, and environmental quality nexus: An investigation of the N-shaped Environmental Kuznets Curve based on six environmental indicators. Energy 2023, 263, 125660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, T.; Erdem, A.; Aydin, M. The nexus of industrial employment, financial development, urbanization, and human capital in promoting environmental sustainability in E7 economies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2025, 32, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, A.; Song, H.; Faheem, M.; Daud, A. Caring for the environment. How do deforestation, agricultural land, and urbanization degrade the environment? Fresh insight through the ARDL approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 11527–11562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.A.; Inuwa, N.; Chaouachi, M.; Samour, A. Testing the Impact of Renewable Energy and Institutional Quality on Consumption-Based CO2 Emissions: Fresh Insights from MMQR Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaidi, R.; Hakimi, A. Financial inclusion, economic growth, and environmental quality in the MENA region: What role does institution quality play? Nat. Resour. Forum 2025, 49, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zubairi, A.; AL-Akheli, A.; ELfarra, B. The impact of financial development, renewable energy and political stability on carbon emissions: Sustainable development prospective for arab economies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 15251–15273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, F.; Alsanusi, M.; Kabir, M.M.; Awan, A. Quantile dynamics of control of corruption, political stability, and renewable energy on environmental quality in the MENA region. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 14001–14021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Batool, Z.; Ain, Q.U.; Ma, H. The renewable energy challenge in developing economies: An investigation of environmental taxation, financial development, and political stability. Nat. Resour. Forum 2025, 49, 699–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C.; Gattone, T.; Madaleno, M. The impact of socio-economic factors on the ecological footprint in Turkey: A comprehensive analysis using machine learning approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 387, 125861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Statistics, 1990–2021. 2023. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- TRT. Türkiye Commits to Net Zero Emissions by 2053, Expand Renewables at COP29. 2024. Available online: https://trt.global/world/article/18231341 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data. 2025. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Destek, M.A. Investigation on the role of economic, social, and political globalization on environment: Evidence from CEECs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 33601–33614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.-C.; Le, T.-H. Effects of economic, social, and political globalization on environmental quality: International evidence. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 4269–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosusi, A.A.; Xulu, N.G.; Ahmadi, M.; Rjoub, H.; Altuntaş, M.; Uhunamure, S.E.; Akadiri, S.S.; Kirikkaleli, D. The Sustainable Environment in Uruguay: The Roles of Financial Development, Natural Resources, and Trade Globalization. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 875577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Jahanger, A.; Radulescu, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Do Nuclear Energy, Renewable Energy, and Environmental-Related Technologies Asymmetrically Reduce Ecological Footprint? Evidence from Pakistan. Energies 2022, 15, 3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Wen, F.; Dagestani, A.A. Environmental footprint impacts of nuclear energy consumption: The role of environmental technology and globalization in ten largest ecological footprint countries. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2022, 54, 3672–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, A.; Yucel, A.G.; Ulucak, R. Green innovation and ecological footprint relationship for a sustainable development: Evidence from top 20 green innovator countries. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.K. Determinants of ecological footprint in OCED countries: Do environmental-related technologies reduce environmental degradation? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 23779–23793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Arshad, Z.; Bashir, A. Do economic policy uncertainty and environment-related technologies help in limiting ecological footprint? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 46612–46619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, O.; Khan, N.; Ahmed, M. Impact of green technological innovations on environmental quality for Turkey: Evidence from the novel dynamic ARDL simulation model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 72207–72223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.-C.; Wang, K.-H. Effects of economic globalization, environment-related technology innovation, and industrial structure change on the ecological footprint of top 10 Asian technological innovation countries. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2024, 14, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Sharma, G.D.; Radulescu, M.; Usman, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Environmental apprehension under COP26 agreement: Examining the influence of environmental-related technologies and energy consumption on ecological footprint. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 7999–8012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.A.H.; Zafar, M.W.; Shahbaz, M.; Hou, F. Dynamic linkages between globalization, financial development and carbon emissions: Evidence from Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir Mehboob, M.; Ma, B.; Sadiq, M.; Mehboob, M.B. How do nuclear energy consumption, environmental taxes, and trade globalization impact ecological footprints? Novel policy insight from nuclear power countries. Energy 2024, 313, 133661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A.; Oğuz, İ.H.; Okumuş, N. Do Trade and Financial Cooperation Improve Environmentally Sustainable Development: A Distinction Between de facto and de jure Globalization. Eval. Rev. 2024, 48, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Hiung, E.Y.T.; Destek, M.A.; Ahmed, Z. Green policymaking in top emitters: Assessing the consequences of external conflicts, trade globalization, and mineral resources on sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2024, 31, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Rasool, Y.; Kashif, U. Asymmetric Impacts of Environmental Policy, Financial, and Trade Globalization on Ecological Footprints: Insights from G9 Industrial Nations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, S. Impact of globalization and industrialization on ecological footprint: Do institutional quality and renewable energy matter? Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1535638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadekin, M.N. Analyzing the impact of remittance and electricity consumption on ecological footprint in South Asia: The role of globalization using panel ARDL and MMQR method. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.H.; Siyad, S.A.; Sugow, M.O.; Omar, O.M. Approaches to ecological sustainability in sub-Saharan Africa: Evaluating the role of globalization, renewable energy, economic growth, and population density. Res. Glob. 2025, 10, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, M.A.; Riaz, M.H.; Uddin, M.N.; Ridwan, M.; Akinpelu, A.A.; Akter, R. Analyzing the Drivers of Ecological Footprint Toward Sustainability in BRICS+. Environ. Innov. Manag. 2025, 01, 2550017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilkaya, O.; Polat, M.A.; Babacan, A. The Effect of Globalization on Environmental Pollution in Turkey: A Fourier Cointegration Analysis. In Community Climate Justice and Sustainable Development; Roy, P.K., Hamidi, M.B., Wahab, H.A., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, A.; Güriş, B. Unveiling the Impact of GDP, Population, Energy Consumption, and Trade Globalization on the Load Capacity Factor in Türkiye: Nonlinear Approaches. Ekonomika 2025, 104, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S. Transforming environmental quality: Examining the role of green production processes and trade globalization through a Kernel Regularized Quantile Regression approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 501, 145232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish; Ulucak, R.; Khan, S.U.-D. Determinants of the ecological footprint: Role of renewable energy, natural resources, and urbanization. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 54, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q. Does renewable energy reduce ecological footprint at the expense of economic growth? An empirical analysis of 120 countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 131207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, E.E.; Acar, S. The nexus between economic growth, renewable energy and ecological footprint: An empirical evidence from most oil-producing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 352, 131548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ge, Y.; Li, R. Does improving economic efficiency reduce ecological footprint? The role of financial development, renewable energy, and industrialization. Energy Environ. 2025, 36, 729–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, S.; Naimoğlu, M. The effectiveness of renewable energy technology under the EKC hypothesis and the impact of fossil and nuclear energy investments on the UK’s Ecological Footprint. Energy 2025, 322, 135351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Niu, H.; Hayyat, M.; Hao, V. Understanding the relationship between ecological footprints and renewable energy in BRICS nations: An economic perspective. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 118, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joof, F.; Samour, A.; Ali, M.; Abdur Rehman, M.; Tursoy, T. Economic complexity, renewable energy and ecological footprint: The role of the housing market in the USA. Energy Build. 2024, 311, 114131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, M.; Georgescu, I.; Çeştepe, H.; Sarıgül, S.S.; Tatar, H.E. Renewable Energy Consumption and the Ecological Footprint in Denmark: Assessing the Influence of Financial Development and Agricultural Contribution. Agriculture 2025, 15, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.; Sun, R.; Mei, H.; Yue, S.; Yuliang, L. Does renewable energy consumption reduce energy ecological footprint: Evidence from China. Environ. Res. Ecol. 2023, 2, 015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, U. Environmental sustainability in Turkey: An environmental Kuznets curve estimation for ecological footprint. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2021, 28, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.; Baris-Tuzemen, O.; Uzuner, G.; Ozturk, I.; Sinha, A. Revisiting the role of renewable and non-renewable energy consumption on Turkey’s ecological footprint: Evidence from Quantile ARDL approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 57, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, B.A. The impact of export, import, and renewable energy consumption on Turkey s ecological footprint. Pressacademia 2021, 8, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahia, M.; Omri, A.; Jarraya, B. Green Energy, Economic Growth and Environmental Quality Nexus in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, V.S. Financial development, economic growth, globalisation and environmental quality in BRICS economies: Evidence from ARDL bounds test approach. Econ. Change Restruct. 2023, 56, 1651–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wasif Zafar, M.; Vasbieva, D.G.; Yurtkuran, S. Economic growth, nuclear energy, renewable energy, and environmental quality: Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve and load capacity curve hypothesis. Gondwana Res. 2024, 129, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirikkaleli, D.; Osmanlı, A. The Impact of Political Stability on Environmental Quality in the Long Run: The Case of Turkey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjra, A.I.; Bouri, E.; Azam, M.; Azam, R.I.; Dai, J. Economic growth and environmental sustainability in developing economies. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.V. Asymmetric Role of Economic Growth, Globalization, Green Growth, and Renewable Energy in Achieving Environmental Sustainability. Emerg. Sci. J. 2024, 8, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Marshadi, A.H.; Aslam, M.; Janjua, A.A. Correction: Ecological footprints, global sustainability, and the roles of natural resources, financial development, and economic growth. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Abdi, A.H.; Mohamud, S.S.; Osman, B.M. Institutional quality, economic growth, and environmental sustainability: A long-run analysis of the ecological footprint in Somalia. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekun, F.V.; Yadav, A.; Onwe, J.C.; Fumey, M.P.; Ökmen, M. Assessment into the nexus between load capacity factor, population, government policy in form of environmental tax: Accessing evidence from Turkey. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2025, 19, 841–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.; Krueger, A. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; p. w3914. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, E.; Inglesi-Lotz, R. The impact of economic structure to the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis: Evidence from European countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 12717–12724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, N.; Shabbir, M.S.; Song, H.; Farrukh, M.U.; Iqbal, S.; Abbass, K. A step towards environmental mitigation: Do green technological innovation and institutional quality make a difference? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 190, 122413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Ibáñez-Luzón, L.; Usman, M.; Shahbaz, M. The environmental Kuznets curve, based on the economic complexity, and the pollution haven hypothesis in PIIGS countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 1441–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilanci, V.; Bozoklu, S.; Gorus, M.S. Are BRICS countries pollution havens? Evidence from a bootstrap ARDL bounds testing approach with a Fourier function. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 55, 102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Patents—Technology Diffusion. 2025. Available online: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/vis?df[ds]=DisseminateFinalDMZ&df[id]=DSD_PAT_DIFF%40DF_PAT_DIFF&df[ag]=OECD.ENV.EPI&dq=.A.GOODS..&pd=%2C&to[TIME_PERIOD]=false&vw=tb (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- KOF. KOF Globalization Index. 2025. Available online: https://kof.ethz.ch/en/forecasts-and-indicators/indicators/kof-globalisation-index.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- OWD. Per Capita Energy Consumption from Renewables, 1965 to 2024. 2025. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-renewables?tab=table&tableFilter=countries&tableSearch=T%C3%BCrk (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econ. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouse, G.; Khan, S.A.; Rehman, A.U. ARDL Model as a Remedy for Spurious Regression: Problems, Performance and Prospectus. Ph.D. Thesis, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Somoye, O.A.; Ozdeser, H.; Seraj, M. Modeling the determinants of renewable energy consumption in Nigeria: Evidence from Autoregressive Distributed Lagged in error correction approach. Renew. Energy 2022, 190, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitung, J.; Candelon, B. Testing for short- and long-run causality: A frequency-domain approach. J. Econ. 2006, 132, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, P.C.B.; Perron, P. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 1988, 75, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, P.; Sarıgül, S.S.; Karataşer, B.; Çetin, M.; Aslan, A. Analysis of the relationship between tourism, green technological innovation and environmental quality in the top 15 most visited countries: Evidence from method of moments quantile regression. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 2337–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yi, J.; Chen, A.; Peng, D.; Yang, J. Green technology innovation and CO2 emission in China: Evidence from a spatial-temporal analysis and a nonlinear spatial durbin model. Energy Policy 2023, 172, 113338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, Ö.; Yıldırım, D.Ç.; Güven, M. Asymmetric impact of environmental innovation on carbon footprint in Turkiye—Healer or disruptor? Symmetry Cult. Sci. 2023, 34, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoye, O.A.; Akinwande, T.S. Exploring the association between the female gender, education expenditure, renewable energy consumption and CO2 emissions: Empirical evidence from Nigeria. OPEC Energy Rev. 2024, 48, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).