Abstract

This research investigates various stakeholder perspectives on AI-powered teacher education, focusing on its potential benefits, strengths, and limitations for integrating this promising technology into a sustainable educational future. It was designed as an exploratory mixed-methods study. It involved five distinct groups: curriculum developers in teacher-training institutions, artificial intelligence experts, department heads and deans in education faculties, private sector managers in teacher-training companies, and over 500 pre-service teachers. The findings reveal promising smart opportunities that AI offers for reimagining teacher training, contributing to the social and long-term institutional sustainability of teacher education. Key components of AI-powered teacher education identified include “Intended use of AI in teacher education context,” “Machine learning with data monitoring,” “AI-human interaction in teacher training,” “AI-powered feedback for better faculty management,” and critically, “Digital vision, risks, and AI ethics for responsible and sustainable implementation.” Prominently stressed codes within these themes include “AI readiness, automated teacher education curriculums, a new recruitment system, designing AI-guided smart faculties, measuring on-entry skills, identifying risky pre-service teachers, improving teachers’ assessment capacity, creating smart content, and criticisms over its value.” The results of the multiple regression analysis demonstrate that curiosity about AI use has the strongest impact on pre-service teachers’ openness and readiness for AI-empowered teacher education, followed by institutional AI support. The research concludes by implicitly calling for a holistic and ethical strategy for leveraging AI to prepare educators to successfully navigate the demands of a sustainable future.

1. Introduction

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into teacher education requires a responsible approach emphasizing sustainability as a core pillar. Moving beyond simple technological adoption, it is necessary to consider AI’s role not just in terms of digital transformation, but also in how it can foster long-term institutional sustainability, equity, and responsible resource management within the teacher-training system. This perspective aligns with Sociotechnical Systems Theory (STS), which posits that organizational performance is optimized when both the social (human) and technical (AI) subsystems are jointly optimized and ethically aligned. The growing use of artificial intelligence (AI) across diverse sectors—from agriculture and autonomous systems to healthcare, finance, and manufacturing [1]—has created a profound societal impact, making it imperative to address its implications for teacher education [2]. This new-generation of technology, with its computational power and resource optimization capabilities, is expected to transform fundamental aspects of teacher preparation.

A review of the existing literature revealed a growing body of research on AI’s potential uses in general educational settings [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Consistent with this trend, Salas-Pilco et al. [14] suggested that future educators (pre-service teachers) must be prepared for an increasingly digitalized educational environment. This preparation is critical because a significant gap remains in understanding the varying levels of support, perception, and ethical concerns across the diverse groups—curriculum developers, administrators, industry, and pre-service teachers—who must collectively drive this change. To effectively support future teachers, research-based implications are crucial for the possible integrations of AI, aligning with the broader goal of building resilient and future-proof teacher educational systems. One key framework for building such systems is Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). This study is situated within the framework of ESD, whose core purpose is preparing individuals to find solutions to issues that threaten global sustainability. Instead of treating it as an optional subject, colleges and universities are expected to embed ESD across the entire learning experience [18], integrating sustainability principles into undergraduate and graduate degree programs, where students learn about the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of their careers.

While AI is a relatively new field in teacher education, pioneering studies like SCHOLAR offer valuable historical perspectives on AI’s role in terms of efficiency and sustainability in education [19,20,21,22,23]. Connecting Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) goals to the actual implementation of technology highlights the crucial need for institutional preparedness, often termed “AI readiness.” Ref. [13] emphasized that different sectors varied in their AI readiness, arguing that the educator community (teacher education in particular) needed to focus on building AI-powered learning communities rather than understanding its technical infrastructure. Ref. [24] stressed that AI readiness is not static but iterative, requiring institutions to continually adapt AI integration in ways that strengthen social and educational sustainability. Building upon the established Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), this study extends the concept of readiness to include ethical and institutional support factors. Ref. [25] pointed out that to make matters worse, the literature did not offer sufficient insight into this issue. They explored what it meant to become ‘AI-ready’ through in-depth interviews with top- and middle-level managers from 52 multinational corporations. The findings suggested that AI readiness could be categorized into eight dimensions: informational, environmental, infrastructural, participants, process, customers, data, and technological readiness [25]. Drawing on this literature, AI readiness in our study is understood as the degree to which an organization or individual is prepared to adopt, implement, and manage capabilities of artificial intelligence in a way that not only enhances teaching and learning but also actively contributes to equity, inclusion and efficiency for a sustainable future. Within this vision, AI’s opportunities, like personalized learning and data-informed instruction, are only truly valuable when they support sustainability goals, particularly those related to Quality Education (SDG 4) and Responsible Consumption (SDG 12).

The study’s conceptual framework, which utilizes Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and Sociotechnical Systems Theory (STS), is crucial for establishing the necessity and ethical boundaries of AI integration in teacher education. Education for Sustainable Development constitutes the normative foundation of this study, serving as the guiding rationale—or the “why”—for the integration of artificial intelligence into educational systems. The central objective is to advance long-term resilience and equitable access to learning opportunities, thereby aligning directly with Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4): Quality Education. Another study conceptualizes smart opportunities of AI as transformative mechanisms for realizing ESD’s overarching aim of preparing educators for a sustainable future. These technological innovations are not treated as ends in themselves but as systemic enablers of sustainability-oriented pedagogical transformation [26]. In terms of equity and inclusivity, smart opportunities of AI can play a pivotal role in promoting educational equity. Its capacity for early detection of learning risks directly operationalizes ESD’s mandate to foster inclusive and equitable quality education. By supporting diverse learners, particularly those from underserved backgrounds, this AI function provides a measurable contribution to achieving SDG 4 outcomes. Pursuing goals related to SDG 4—like equity, inclusion, improving teacher skills for employment, and increasing lifelong learning in future teachers—is more viable through AI integration. As exemplified by [27], AI tools like Microsoft’s Immersive Reader and Google’s transcription software helped create more inclusive and equitable classrooms. By assisting students with disabilities and those who are not native speakers, these technologies empower all learners and embrace diversity in the learning environment.

Simply adopting AI tools falls short of the primary goal of AI-empowered teacher education: for it to be truly successful and contribute to SDG 4 (Quality Education), it must be implemented in a way that is environmentally responsible, financially viable, and ethically sound [18,28]. To ensure a sustainable and equitable future, teacher training should focus on how smart opportunities provided by AI integration into teacher education empower global sustainability frameworks, such as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals provide a roadmap and there have been indications that AI could be a powerful tool for achieving them, especially in terms of social sustainability [29,30]. It helped directly address the equity and access goals of SDG 4 by providing scalable learning opportunities for underserved populations [31]. Additionally, as a measurable impact, AI can make globally environmental complex problems understandable, which is a key part of fostering an eco-friendly mindset for sustainability [32].

AI holds transformative and sustainable potential in empowering teacher development by fostering long-term institutional sustainability, automated assessments, and responsible use of educational resources. AI can promote peer collaboration by identifying and recommending connections between educators who have complementary skills and shared interests. By using AI to foster these relationships, teachers can learn from one another, adopt best practices, and work together on projects that contribute to shared professional growth, as Jeelani and Syed [33] suggested. Current literature explored assessment practices of AI comparing ChatGPT ‘s (GPT-3.5) effectiveness against traditional teacher assessments [12] and investigating its benefits in pedagogy including interactive learning, automated essay grading, and personalized tutoring [3]. Ref. [34] highlighted AI’s role in enhancing critical thinking, noting its capacity as an idea generator, scaffolding tool, and editorial guide. A growing body of research has demonstrated how AI practices in controlled environments can significantly improve students’ academic performance [35,36], metacognitive development [37,38], and emotional engagement [39,40]. Furthermore, specific AI practices like ASSISTments, Cognitive Tutor ALGEBRA, and ALEKS [41,42,43] showed statistically significant positive effects on learning and accomplishment in real-world contexts. These findings underscore how empowering teacher education with AI can enhance pre-service teachers’ assessment capacities and professional development, ultimately contributing to a more efficient and impactful allocation of educational resources as a part of sustainability.

1.1. Addressing the Lag and Fostering Equitable Access

A World Bank report by [16] revealed that low- and middle-income countries invest millions in teacher education annually, yet often fail to equip educators with the necessary technological and pedagogical expertise. This makes most of the current teacher education models unsustainable. The report stressed the urgent need to transform teacher training with AI, understand the profile of new-generation teachers, and embrace new concepts like smart content, automated assessments, and personalized learning for professional development. Unfortunately, the actual use of AI in teacher preparation programs continues to lag behind these developments [2]. This persistent implementation gap, particularly regarding multi-stakeholder consensus on core AI components and readiness, highlights a critical area for sustainable development research in teacher education, in the hope that underserved regions could benefit from technological advancements.

Artificial intelligence offers smart opportunities and significant potential to promote the key principles of SDG such as equity and access to high-quality educational content. Smart opportunities can be defined here as “new possibilities for value creation, efficiency, or innovation that emerge directly from the strategic use of AI technologies to advance sustainable development goals”. This concept goes beyond simply using AI tools; it highlights unique advantages enabled by core capabilities of artificial intelligence. In teacher education, it involves not just using an app but also leveraging AI for systemic improvement and new, more sustainable ways of teacher professional development. As one smart opportunity, AI integration can enhance assessment capacity through adaptive, unbiased, and scalable evaluation methods [12]. Bridging access gaps, AI-powered tools deliver directly to devices in remote or under-resourced communities. From this perspective, [3] investigated the potential benefits of incorporating AI into pedagogy, highlighting its potential in automated essay grading and personalized tutoring. Furthermore, unlike traditional teacher-led assessments, AI’s evaluations have the potential to reduce unconscious biases related to gender, language, culture, or ability. In terms of its capacity, AI is a “renaissance in assessment” according to [44]. AI can give teachers instant assessments and continuous evaluation rather than one-time assessments [2]. This streamlined assessment process can lead to more efficient feedback loops and reduced resource consumption associated with traditional grading methods. From a sustainability perspective, AI also supports educators in identifying learning gaps across diverse student populations more efficiently, enabling faster and more targeted interventions—particularly in under-resourced educational settings. Even when looking at the limited number of studies, the necessity of powering teacher education with artificial intelligence for sustainability goals is clear.

1.2. Theoretical Framework: The Role and Practices of Artificial Intelligence in Teacher Education

While higher education institutions have generally embraced Gen-AI and chatbots, their integration into teacher education faculties remains an urgent question. Ref. [9] reported the widespread adoption of intelligent chatbots in higher education for supporting learning, connecting students to course information, and assisting with various academic tasks. China and the United States are at the forefront of AI education expenditure [45], with numerous AI education service companies globally putting AI into practice. Companies like SquirrelAI were developing “AI supereducators,” while IBM’s Watson and McGraw-Hill’s ALEKS were proved effective in improving student academic performance and reducing course completion times [41,42]. These instances highlighted AI’s capacity for optimizing learning and resource management, which is a crucial element of sustainable educational practices [43]. The diverse practices of AI trends in educational institutions such as secondary or high schools include adaptive learning and AI-supported proctoring in smart classrooms. This leads to the crucial question: How prepared is teacher training to embrace this digital transformation in a new era, and what are the key components identified by its stakeholders?

The integration of AI into teacher professional development aligns with the key principles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) such as holistic and transformative change, system thinking, and fostering adaptability. Ref. [46] highlighted AI’s role in creating a transformative learning environment for teacher training. AI has the capacity to revolutionize teacher training through machine learning in classrooms, making smart suggestions and providing analytics-driven tutoring. AI is also regarded as “renaissance in assessment” [47] enabling earlier identification of learning gaps and allowing for timely interventions. Ref. [14] emphasized AI’s support for teachers’ decision-making by reporting real-time class status and responding to learner needs via AI-based platforms. Their systematic review depended on behavioral, discourse, and statistical data in large educational datasets for machine learning. Most AI studies focused on behavioral data collected through observing and recording teacher behaviors, allowing machine learning to identify teachers’ patterns [48,49]. Machine learning and natural language processing [50,51] were commonly used techniques in AI to empower teacher professional development, with some rare studies exploring vision-based mobile augmented reality [52]. Some studies relied on AI software tools such as chatbots that can employed to support pre-service teachers’ professional skills [51].

Examples of specific AI tools that enhance teacher education include Moodle, Knowledge–Behavior–Social Dashboard tool, Code.org, TraMineR, and various analytical and visualization tools [14]. AI-based simulations offered pre-service teachers safe environments to practice classroom scenarios, developing key skills like classroom management [53]. Learning analytics tools allow pre-service and novice teachers to monitor their development, receiving video-based feedback on speaking speed, gestures, and facial expressions [50,54]. Chatbots like LitBot and FeedBot provide tailored support for self-directed learning and automated feedback [51]. In a study, an assessment system developed on AI was found effective in assessing teaching competencies and identifying qualification standards [55]. Interestingly, AIED systems were even found to perform better than human teachers in tutoring large classes, though they were less effective than one-to-one human tutoring [54].

Education for Sustainable Development stresses interconnectedness in terms of system thinking. As in interdependence of environmental, social, and economic systems, we have been—to a certain degree—connected with machines as teachers. The use of AI as a classroom assistant demonstrates the interconnectedness of human and machine roles in teacher education. Integrating artificial intelligence into teacher education underscores a vital link between technology and the human aspect of teaching. Some researchers have addressed artificial intelligence as classroom assistants [2] supporting human (teacher)–machine interaction in class, giving AI the role of classroom assistant. AI can create adaptive groups, facilitate online interactions, and contribute to collaborative learning by summarizing ideas and key concepts so that a human instructor can succeed in the primary aims of a course [2]. This kind of human–AI interaction in classrooms requires a system design. Ref. [53] focused on the design of AI-assisted instruction and practical applications in the classroom and asserts that the implementation of such a smart class was reported to improve classroom performance by 25%. Empowering teacher education with AI is crucial to embrace a collaborative and interconnected approach to teacher education issues as a part of institutional sustainability. The Triple Bottom Line theory, with its three pillars (people, planet, and profit), provides a comprehensive guide for understanding AI-empowered teacher education.

People: This pillar focuses on the social and human aspects, including the well-being of individuals and communities. Research questions about stakeholders’ perceived benefits and ethical risks already align perfectly with this.

Planet: This pillar concerns environmental impact. While AI in teacher education may not seem to have a direct environmental link, this link can still be explored. For example, reducing costs for professional development through AI-powered teacher training can lower carbon emissions. Alternatively, it may have environmental impacts due to the energy consumption of AI data centers.

Profit: This pillar, often called “prosperity,” refers to economic viability and sustainability. Research questions on institutional support and private-sector managers’ views connect to this, as they are concerned with the financial and strategic value of integrating AI.

There is a need to explore smart opportunities of AI to create a more equitable, efficient, and sustainable model for the future of teacher education. This research investigates various stakeholder perspectives on AI-powered teacher education, focusing on its potential benefits, strengths, and limitations for integrating this promising technology into sustainable teacher education. It is important to note that 70% of AI research in education was student-oriented, with teachers being underrepresented [2] or teacher education ignored. This gap underscores the need to research how AI can strategically empower teacher education through the perspectives of diverse stakeholders (curriculum developers, AI experts, deans, private sector managers, and pre-service teachers).

Accordingly, the study is guided by the following research questions:

What are the different stakeholders’ perspectives about AI-empowered teacher education (deans, curriculum developers, AI experts, and private sector managers)?

TBL Framing: This question addresses the people and profit dimensions by exploring the social and economic benefits perceived by various stakeholders. It acknowledges that value is created for all, not just for one group.

What is the readiness and openness level of pre-service teachers for AI-powered teacher education? Which variables predict pre-service teachers’ openness and readiness level (ORATE) for AI-empowered teacher education?

TBL Framing: This question is a direct measure of the people pillar. It assesses the readiness and human capital aspects of AI integration.

H1.

There is a significant relationship between a set of independent variables (teachers’ perceived institutional support, curiosity about AI use, daily AI use frequency, and teaching field) and the dependent variable (the readiness and openness level for AI-powered teacher education).

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a sequential exploratory research design proposed by [56]. Due to the scarcity of sufficient research on artificial intelligence in teacher training, this approach was vital for in-depth exploration and prevalence. Exploratory research is usually preferred when the issue under research is new or when the process of gathering data is challenging for several reasons [57]. According to [56], in a sequential exploratory mixed method design, the qualitative component is the primary component and the quantitative component is used for support of the qualitative analysis that helps to validate the ideas generated from the qualitative component. To combine them in the best way to provide an understanding of opportunities of AI-powered teacher education, this study collected the qualitative data with online focus group discussions (including curriculum developers, AI experts, and managers in the private sector) and face-to-face interviews (including deans and department heads), then collected the quantitative data with a survey for descriptive and inferential analyses (including pre-service teachers). This study is conceptually grounded in Stakeholder Theory, which posits that an organization’s success and sustainability depend on its ability to satisfy the interests of all its key stakeholders, not just its shareholders. Ref. [58]. We have expanded this to the context of teacher educational innovation, asserting that the successful and ethical integration of AI into teacher education depends on understanding and incorporating the perspectives of diverse stakeholder groups. This theoretical perspective directly guides our research design by accomplishing the following:

Justifying the Multi-Stakeholder Approach: The theory was the primary reason we chose to include diverse groups—deans, curriculum developers, AI experts, and private sector managers—in our study. Stakeholder Theory recognizes that each group holds a unique “stake” in the outcome of AI integration, providing distinct insights into its benefits, challenges, and ethical implications. Also, in accordance with TBL theory, the interviews with deans and department heads would uncover insights on economic viability and institutional support (“Profit”). The focus groups with curriculum developers and AI experts would provide perspectives on the social and educational impacts (“People”).

Data Collection Strategy: To capture the rich, varied perspectives of these stakeholders, we adopted a sequential exploratory mixed-methods design. The qualitative phase, consisting of online focus group discussions and face-to-face interviews, was specifically designed to explore the subtle views of each stakeholder group. This initial data collection was not just to explore a new topic but also to fulfill the core principle of Stakeholder Theory—giving voice to those impacted by a change. By including diverse voices from different sectors (e.g., academics, private industry, and educational practitioners), this study can identify unforeseen challenges or opportunities, leading to more robust and comprehensive solutions that would be impossible to achieve with a single-perspective approach [59].

2.1. Justification of Research Method

This approach is particularly well-suited for this study for two primary reasons: the newly emerged nature of the topic and the complementary relationship between the qualitative and quantitative data. The qualitative phase of this study was designed to explore the opportunities and limitations of AI-empowered teacher education from the perspectives of key stakeholders. The insights from this phase were crucial for developing a valid and relevant survey instrument for the quantitative phase. An exploratory design is the most appropriate method when a topic is new or poorly understood. By starting with a qualitative phase, this study can uncover the perspectives, challenges, and opportunities of AI-powered teacher training. This initial qualitative exploration is crucial for generating foundational insights and hypotheses that would be difficult to formulate with a quantitative-only approach. The rich, detailed information gathered from focus group discussions and interviews was used to develop a survey instrument. This ensures that survey items are not only relevant but also directly grounded in the lived experiences and concerns of stakeholders, which is the central aim of this study’s theoretical framework.

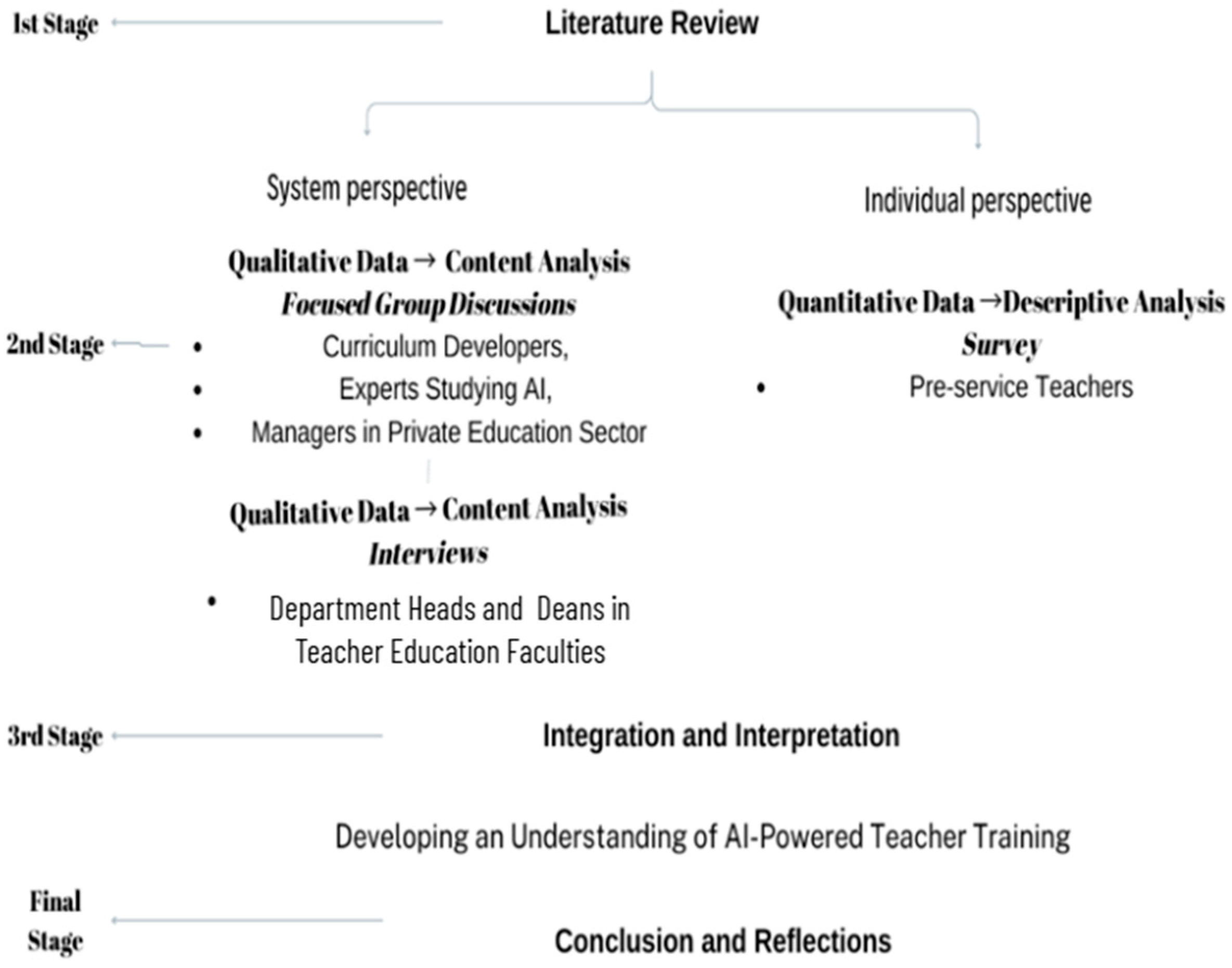

Figure 1 presents the research process and the steps followed at each stage.

Figure 1.

Visual model of data collection and analysis process in this study.

Study Group

Qualitative data were collected through two different methods to capture a broad range of expert opinions:

Online Focus Group Discussions: Three online focus discussion groups were conducted, each consisting of 5–7 participants. Participants included curriculum developers, AI experts, and managers from the private sector. This allowed for the inclusion of geographically dispersed experts, fostering a rich, multi-disciplinary discussion. These discussions were semi-structured, guided by a protocol designed to reveal diverse views on AI’s potential within a teacher education context.

In the first group, a purposive sampling technique was adopted, defined by [60] as “the sampling of a politically important case, which is a special or unique situation involving the selection of important or sensitive cases for study”. The first group included 6 curriculum developers, 6 artificial intelligence experts, and 4 managers working in the teacher-training institutions in the private sector. These participants were selected because of their direct involvement in leading teacher education programs and their strategic insight into how AI could be integrated. Table 1 presents the demographic information about participants in the first study group in the research.

Table 1.

The descriptive statistics of participants in the first study group.

Face-to-Face Interviews: In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with deans and department heads from teacher education faculties. Face-to-face interviews were preferred for these participants to encourage a deeper, more personal reflection on institutional and pedagogical challenges. The interview protocol explored their perspectives on the practical implementation of AI into teacher education, its value, and ethical implications for institutional sustainability.

The second group included 8 academic department heads and 8 deans in different education faculties, adopting a purposive sampling technique, which selects participants based on specific purposes to answer a research study’s questions. These participants were chosen deliberately, not randomly, as they worked as part of faculties with a demonstrated interest in AI—as evidenced by their organization of AI-related seminars—and could provide informed perspectives on institutional readiness, policy considerations, and leadership-level decision-making in AI adoption. Table 2 presents demographic information about participants in the second study group.

Table 2.

The descriptive statistics of participants in the second study group.

Lastly, as the third study group, a survey was developed from the qualitative data and conducted with 528 participants from different education faculties to reveal the readiness and openness level of pre-service teachers for AI-empowered teacher education. This group was included to capture the perspectives of pre-service teachers who will play a crucial role in next-generation teacher-training practices. Table 3 presents demographic information about participants in the third study group.

Table 3.

The descriptive statistics of participants in the third study group.

Researchers took steps to identify and remove data points considered missing or significant outliers. They (n = 16) were identified and removed from the dataset to prevent them from distorting the model’s coefficients and standard errors. The quantitative analysis only included participants who fully provided the necessary data. The analysis included only the 512 participants who properly completed the ORATE Survey and recorded their “teaching area,” “frequency of daily AI use,” “perceived institutional AI support,” and “their curiosity level for AI use”.

By engaging these distinct study groups, the study ensures a multi-stakeholder perspective of AI-powered teacher education, enabling both vertical and horizontal triangulation of insights across the teacher education ecosystem.

2.2. Justification of Sampling

The use of focus groups, individual interviews, and survey participants provides methodological triangulation, strengthening the credibility of the findings. Focus groups are ideal for generating a wide range of ideas and revealing shared opinions, while individual interviews allow for a deeper exploration of personal experiences and subtle perspectives from influential decision-makers. The selection of these specific participatory groups was justified by their diverse expertise: curriculum developers and department heads provide educational context, AI experts offer technical insights, and private sector managers contribute a valuable perspective on scalability and practical application. The subsequent quantitative data from the survey of pre-service teachers then served to validate and generalize the findings from the initial qualitative phase, providing a broader understanding of the prevalence and significance of the identified themes. This mixed-methods approach offers a more robust picture than either a qualitative or quantitative study could achieve on its own.

To start with, Qualtrics software was used to determine the adequacy of the sample size. It was determined that the total population size of pre-service teachers in the faculties of education in Turkey was 195,475 [61]. A total of 528 participants from different universities were included in this study with 95% confidence interval and 4% margin of error, and they were thought to represent the population. To address a limitation, while this sample size was statistically significant for a Turkish context, it may not be generalizable to other countries with different educational systems and technological infrastructures.

2.2.1. Data Collection

In the first stage, two online focus group discussions with curriculum developers, artificial intelligence experts, and managers lasted more than 110 min. In the second stage, 16 individual interviews were arranged with deans and department heads ranging from 18 min to 22 min. Two different data collection forms were developed after reviewing both the AI literature and the teacher-training literature. Forms include questions on expectations, opportunities, and concerns regarding AI-powered teacher education (Form A for the online group focus discussion and Form B for the individual interviews).

To ensure the validity of these data collection tools, multiple strategies were focused on. These included strategies to establish content validity, face validity, construct validity, and credibility. To establish content validity, the data collection instruments (Forms A and B) were meticulously developed based on a comprehensive review of the current literature on both artificial intelligence and teacher training. Face validity was secured by subjecting the forms to expert review from a linguist, an instructional technologist, and an educational science expert, ensuring the clarity and appropriateness of the questions. The credibility of the qualitative findings was enhanced through several established techniques. Triangulation was employed by collecting data from multiple sources (focus groups and individual interviews) and multiple groups (curriculum developers, AI experts, and academic leaders). The study further enhanced credibility through member checking to verify participants’ responses, providing thick descriptions of the data for contextual richness. The researcher acknowledges his own biases and how they might influence data collection and analysis, which adds transparency. Pilot testing with a smaller group of participants (N= 5) and the feedback from this pilot test helped refine the data collection tools and ensure that they were understood as intended. For transparency, some participants, especially those in formal roles like deans and department heads, might have felt pressured to provide answers that were perceived as positive or progressive regarding technology and innovation, rather than expressing their genuine concerns.

For the quantitative data, an online survey was developed and validated to assess pre-service teachers’ openness and readiness for AI-powered teacher education. Content validity was established by creating an item pool based directly on the themes and insights derived from the qualitative data, which explored stakeholders’ expectations, opportunities, and concerns. The items were also initially drafted. Following this, a preliminary set of items was shared with a panel of three experts—scholars in educational technology, curriculum design, and AI ethics—to refine the survey items and ensure they were clear, unbiased, and relevant. Their feedback was critical for refining the survey items to be relevant to the study’s objective. The draft version initially included 20questionnaire items. As a pilot test, the revised version was applied to a smaller group of participants (N = 10). The final version included an 11-item questionnaire form with an informed consent form, which were sent to the volunteer participants as an online survey. The survey instrument’s reliability was confirmed using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding a coefficient of 0.88 indicating good/excellent internal consistency for the survey instrument [62]. Table 4 presents the data collection process and tools followed in this study.

Table 4.

Participating groups, data collection tools, and focus group questions.

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Sinop University Research Ethics Committee Approval No [SNU1206] prior to data collection. All participants were informed about the purpose, procedures, and voluntary nature of their participation, and informed consent was obtained from each participant before conducting interviews or administering the survey.

2.2.2. Data Analysis

An inductive approach was used to analyze the qualitative data through open coding and thematic analysis using MAXQDA 22. As the first stage in the coding process, open coding enables the researcher to find broad preliminary themes. The initial reading and rereading process was followed to find broad themes. Afterwards, axial coding was used to find connections among open codes and clarify categories for selective coding [63]. In order to ensure the validity of the qualitative data analysis, peer debriefing, member checking, and triangulation techniques were used in the study to ensure credibility and dependability [64]. To enhance the trustworthiness and rigor of the qualitative analysis, peer review was conducted by two independent researchers who examined coding consistency and theme development. Two iterative discussions were conducted with a team of two experts. A code book (list) was created independently through reading and re-reading through all data to identify codes and themes. The codes and themes that were appropriate in terms of understanding AI-powered teacher training and those that were outside of it were identified. Stepwise replication was used to review, organize, define, and name the codes and themes indicated by the data [65]. At 4-week intervals, the data were coded and recoded again to enhance the dependability of the qualitative inquiry [66]. Member checking was implemented by sharing summarized findings with a subset of participants to confirm the accuracy and interpretation of their perspectives. Each participant verified the analysis results and interview transcripts, and revisions were made when needed. Triangulation was achieved by comparing data across multiple stakeholder groups and integrating both qualitative and quantitative findings to ensure a comprehensive and corroborated understanding of the phenomena. Table 5 presents how coding process have been followed for analysis of qualitative data.

Table 5.

Examples of coding process used for qualitative data.

After the discussion of the code book (list) with two independent coders, an 82% inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s kappa coefficient) was attained. A discussion and consensus session was held and the inter-rater reliability increased to 86%. The final code list included 30 codes and all the codes were grouped under five themes to best reflect their characteristics.

When it comes to the quantitative data, the inferential statistics were conducted using SPSS version 21. As one of the inferential statistical techniques, multiple regression analysis (R2, β coefficients) was applied. Multiple regression is the ideal method to test the predictive power of a set of independent variables (perceived institutional AI support, curiosity about AI use, frequency of daily AI use, and teaching fields) on a single dependent variable (openness and readiness for AI-empowered teacher education). This analysis revealed which of these factors had the strongest influence on the dependent variable and the overall variance they explained. Additionally, as one of the inferential statistical techniques, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (F statistic, p-value) was conducted. ANOVA was used to compare the means of a continuous dependent variable (openness and readiness for AI integration) across two or more independent categorical groups. When a significant difference was found, post hoc tests (Bonferroni test) were conducted to determine which specific groups differed from each other.

For the multiple regression analysis and one-way ANOVA to be valid and the results reliable, several key statistical assumptions had to be met: normality, homogeneity of variances, independence of observations, linearity, multicollinearity, outliers, and normality of residuals. The dependent variable (ORATE) was measured on a continuous scale; four independent variables were categorical (nominal variables). Then, Durbin–Watson statistics were used to check the assumption of the independence of errors/autocorrelation.

Absence of Outliers: The dataset might contain observations that had an unusual influence on the regression model. These outliers, while distinct, represent data anomalies that could significantly distort the model’s coefficients and standard errors. Significant outliers (n = 16) were identified and removed for multiple regression analysis.

Normality: Skewness and kurtosis were checked in the data to ensure normality. The statistical value of skewness obtained from the analysis was divided by the standard error value and it came out that the values were between +1.5 and −1.5 at 5% significance level. Therefore, the normality of the distribution of the data was ensured [67]. Homogeneity of variances was also ensured in SPSS Statistics using Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances.

Linearity: The relationship between the dependent variable and each independent variable must be linear. Linearity was visually checked by creating scatterplots. The scatter plot of the values with strong positive skew and strong negative skew were checked for linearity and it was observed that an elliptical form was obtained.

Absence of Multicollinearity: The independent variables should not have been highly correlated with one another. This assumption was checked by examining correlation coefficients between independent variables and by tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values. It should be emphasized that multicollinearity problem may arise when pairwise correlations are greater than 0.90, VIF values are equal to or greater than 10, and tolerance values are smaller than 0.10 [68].

In Table 6, the Durbin–Watson statistic was found to be between 1.5 and 2.5 (acceptable range), indicating no significant evidence of positive autocorrelation among the residuals [69]. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was tested to indicate the presence of multicollinearity. If the value of VIF is above 5, there is multicollinearity among the independent variables in a model. Collinearity diagnostics were performed to check for multicollinearity among the independent variables. As tolerance > 0.25 and the variance inflation factor (VIF) values ranged from 1.01 to 1.26, well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5 or 10, this indicated that multicollinearity was not a concern in the model [70]. Table 6 presents collinearity statistics about the collected data.

Table 6.

Durbin–Watson, tolerance and VIF values.

3. Findings and Results

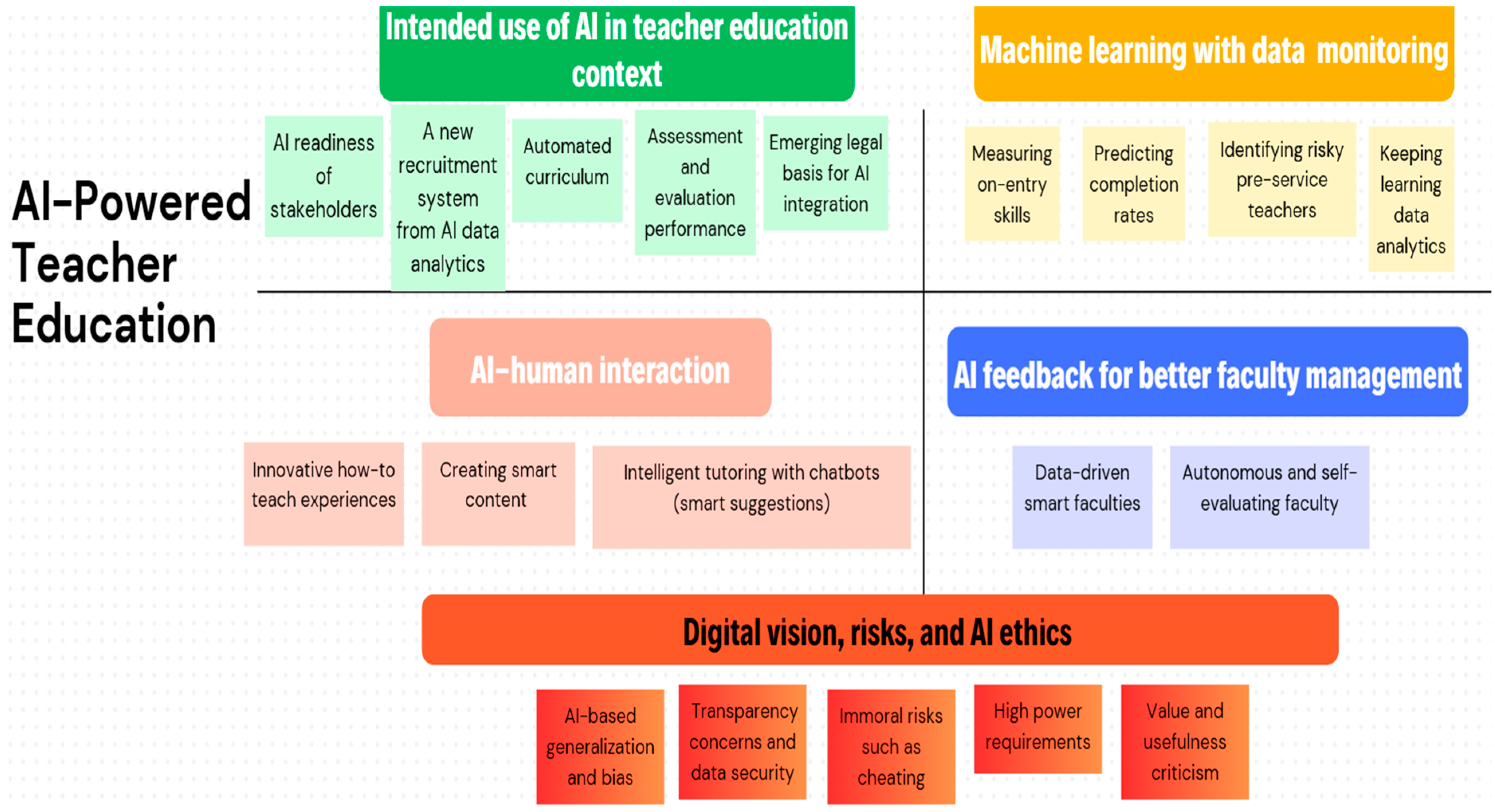

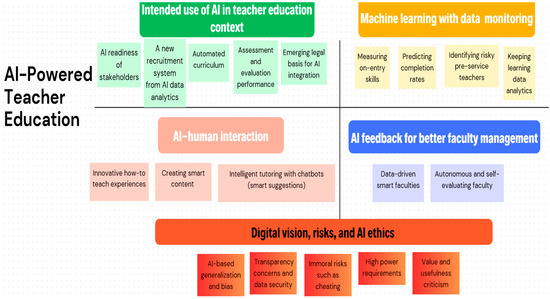

This study attempted to develop a coherent understanding about the smart opportunities of AI for reimagining teacher training and the key components for the development of AI-powered teacher education. The analysis of the collected data reveals that AI-powered teacher education can be conceptualized through five components including “intended use of AI in the teacher education context; Machine learning with data monitoring; AI-human interaction; AI feedback for better faculty management; Digital vision, risks and AI ethics”.

The five components of AI-powered teacher training are explained in detail with codes and examples in Table 7:

Table 7.

Summary of themes and explanation of codes.

The qualitative findings and codes indicate that all stakeholders (except for the deans) interested in the field of teacher training show a high level of willingness to adopt AI-powered teacher training, which is expected to increase social, institutional, and economic sustainability. They are open to the integration of new-generation technologies into the teacher-training system. They accept machine–human interaction as a reality of today, not of the future, and with utmost care they associate AI with ethical issues at a high level. On the other hand, faculty deans have a relatively low opinion about this digital vision and show a low level of willingness to integrate AI into faculty-training systems. Most of the stakeholders find AI valuable due to the potential performance of AI as an adaptive content creator and in personal learning analytics and tutoring. They emphasized that AI can use learning analytics to enhance each pre-service teacher’s professional development based on smart suggestions and can also be effective in supporting them 24/7. AI integration is also expected to increase the test development skills and assessment capacities of pre-service teachers (creating short essay questions or multiple-choice test items or even evaluating individual research reports). It can serve as a useful data-source tool for a new recruitment system for public and private schools.

The findings indicate that five components are critical in AI-powered teacher training from a multi-stakeholder perspective as displayed in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

The key components of ai-powered teacher training from a multi-stakeholder vision.

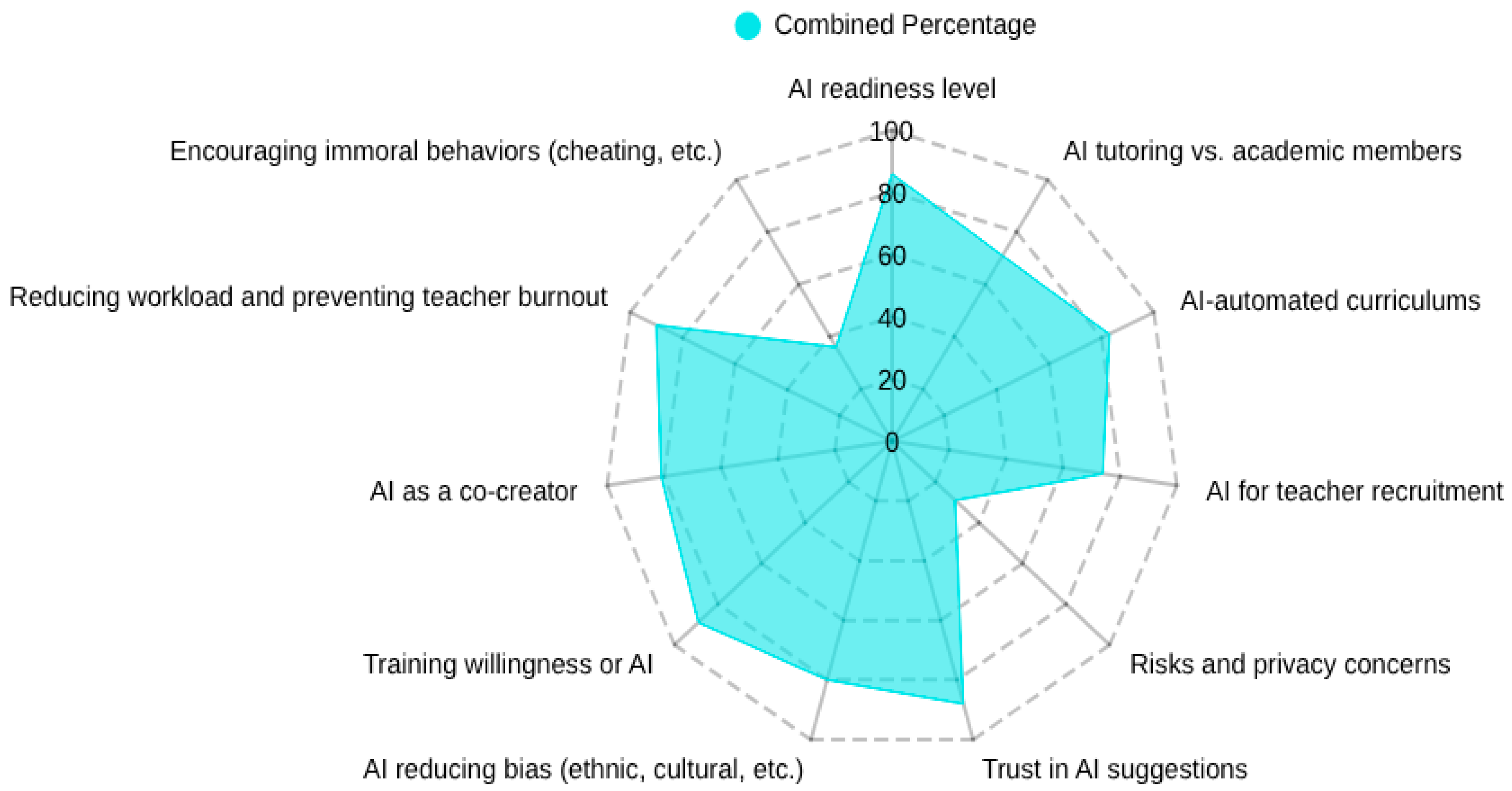

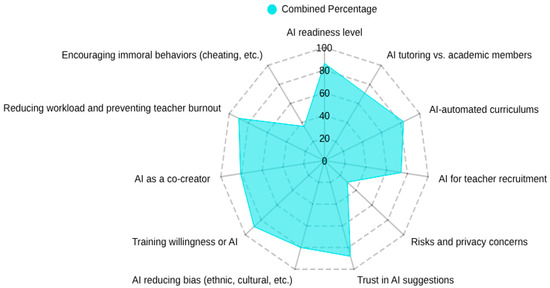

The quantitative data collected from pre-service teachers was analyzed with SPSS 21. Figure 3 displays a radar chart showing the combined positive responses (selecting totally agree and agree on the Likert scale) about pre-service teachers’ attitudes about AI-powered teacher training.

Figure 3.

Pre-service teachers’ openness and readiness for AI-powered teacher training.

Figure 3 points out that pre-service teachers also have a high level of readiness supporting AI trends in teacher education systems. They trust smart revisions led by artificial intelligence and embrace machine–human teacher interaction in the classroom. They mostly accept AI as a co-creator/assistant in teaching given that AI and teachers respect each other’s unique abilities. They are open to training to integrate AI applications into teaching practices, which would reduce their workload and burnout. They think that teacher education faculties should offer intelligent tutoring services. Pre-service teachers show relatively high levels of tolerance to the risks of AI, believing that AI can help resolve conflicts and even reduce ethnic and cultural bias problems and allow for new pedagogies. However, in terms of professional development, pre-service teachers believe that they can interact more effectively with faculty members rather than an AI-powered teacher-training system. A recruitment system based solely on AI should not be adopted in teacher recruitment because AI may fall short in assessing teacher qualities such as empathy and creativity and it cannot fully take into account contextual factors such as cultural alignments with the school’s mission; therefore, it appears to pre-service teachers that it is not feasible to use AI for recruitment. They also do not agree that AI would encourage immoral behaviors (e.g., cheating) among pre-service teachers in education faculties.

Findings of Inferential Statistics (Multiple Regression Analysis and ANOVA Results)

The researcher included 512 participants (after outliers were removed) who properly completed the ORATE Survey (Openness and Readiness for AI-Empowered Teacher Education) and also recorded their “teaching area”, “frequency of daily AI use”, “perceived institutional AI support”, and “their curiosity level for AI use”.

The researcher’s goal was to be able to infer which variables strongly predict ORATE. In Table 8, the correlation matrix indicates that there is a positive and strong relationship between perceived institutional AI support and ORATE (r = 0.38) as well as curiosity about AI use and ORATE (r = 0.48). Subsequently, the results also show no significant relationship between teaching field and ORATE (r = −0.02) as well as frequency of daily AI use and ORATE (r = −0.02). The perceived institutional AI support and curiosity about AI use correlations were significant at p < 0.05. Multiple regression analysis was used whereby independent variables were put into a regression equation concurrently to determine significant predictors of the dependent variable, namely ORATE.

Table 8.

Correlation matrix between variables.

Table 9 indicates that the factor of curiosity about AI use was found to be the strongest predictor (β = 0.418, p < 0.05) of openness and readiness for AI-empowered teacher education, followed by perceived institutional AI support (β = 0.283, p < 0.05).

Table 9.

Multiple regression analysis results.

- Predictors: (Constant), Curiosity about AI use, perceived institutional AI support.

- Dependent Variable: ORATE.

In Table 10, R2 of 0.310 indicates the contribution of the combined two independent variables to the variance of the dependent variable. Curiosity about AI use and perceived institutional AI support together predicted 31% of the variance in openness and readiness for AI-empowered teacher education. For this study, teaching field and daily AI use frequency were excluded from the final model since their correlations were not significant (p > 0.05). Table 11 tests whether the overall regression model is a good fit for the data.

Table 10.

Model summary.

Table 11.

Overall regression model.

Table 11 indicates that perceived institutional AI support and curiosity about AI use statistically significantly predicted the dependent variable ORATE, F(2, 508) = 113.979, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.310.

When it comes to the one-way ANOVA results for curiosity about AI use, Table 12 provides some very useful statistics about subgroups based on the curiosity about AI use variable, including their means and standard deviations.

Table 12.

Descriptive statistics about subgroups based on curiosity about AI use.

Table 12 shows that the lowest scores belong to slow adopters while moderate and high scores belong to cautious optimists and tech adventurers.

Table 13 indicates that there is a statistically significant difference between subgroups as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(2508) = 77.799, p < 0.05). The multiple-comparisons table contains the results of the Bonferroni post hoc test.

Table 13.

ANOVA results between groups.

Table 14 indicates that there is a statistically significant difference in openness and readiness for AI-empowered teacher education between tech adventurers and slow adopters (p < 0.05) and cautious optimists (p < 0.05), with tech adventurers showing higher ORATE, as well as between cautious optimists and slow adopters (p < 0.05), with cautious optimists showing higher ORATE.

Table 14.

Multiple-comparisons Bonferroni results.

Table 15 provides some very useful statistics, including the means and standard deviations for the dependent variable (ORATE) for subgroups based on perceived institutional AI support.

Table 15.

Descriptive statistics about subgroups based on perceived institutional AI support.

Table 15 indicates that those who receive the highest support from their institution for AI are those with the highest readiness for AI-empowered teacher education. Table 16 presents the ANOVA analysis and whether there is a statistically significant difference between the subgroups. Table 16 indicates that there is a statistically significant difference between the subgroups, F(2508) = 45.304, p < 0.05). Table 16 presents the multiple-comparisons according to the results of the Bonferroni post hoc test.

Table 16.

ANOVA results between subgroups based on perceived institutional AI support.

Table 16 indicates that there is a statistically significant difference in openness and readiness for AI-empowered teacher education between subgroups.

Table 17 indicates that there is a statistically significant difference in ORATE level between the strong support and low support subgroups (p < 0.05) with the strong support subgroup showing higher ORATE, as well as between the moderate support and low support subgroups (p < 0.05) with the moderate support subgroup showing higher ORATE. There was no significant difference found between the subgroups with moderate institutional AI support and strong institutional AI support in terms of ORATE. Those who received the highest support from their institution were those with the highest readiness for AI-empowered teacher education which suggests a strong correlation between the level of support given by an institution and a pre-service teacher’s openness to AI. Institutional support is a key driver of teacher readiness for AI-empowered teacher education. Table 17 presents how ORATE level differ depending on institutional AI support

Table 17.

Multiple-comparisons Bonferroni results.

4. Discussion

Teacher-training institutions do not have much time to reflect on how AI will empower teacher education. The findings of this study reveal strong stakeholder interest in AI-powered teacher education and there exist promising smart opportunities for AI to reimagine teacher training to develop future-ready teachers. With the exception of deans, there is high consensus among department heads, curriculum developers, and pre-service teachers on the integration of AI into teacher education. Deans’ more cautious stance appears linked to their institutional leadership responsibilities, which require careful alignment with policies, ethical standards, budget constraints, and data privacy regulations. This mirrors earlier observations by [2], who noted that administrative leaders often act as “gatekeepers” to large-scale technological change. Instead of immediately deploying AI in the classroom, AI systems should be launched exclusively through audited pilot programs focused on highly efficient administrative tasks (like automated document review, scheduling, or basic data reporting). Auditing these pilots allows administrators to see quantifiable proof of efficiency gains and a solid Return on Investment (ROI).

In contrast, pre-service teachers, department heads, and curriculum developers tend to be innovation-oriented, viewing AI as a timely and transformative tool for a sustainable future and qualified pedagogical practices which could improve the overall efficiency of teacher education. Their openness and readiness remind us of [71], which claims that educators’ willingness to adopt emerging new technologies strongly predicts their actual use. The divergence of deans suggests that leadership concerns over accountability and AI readiness of faculties may slow its adoption, even when operational stakeholders perceive AI as immediately beneficial. This divergence creates an institutional tension that is key to long-term sustainability: the drive for immediate efficiency versus the need for robust, long-term governance. To navigate this tension and prepare students for a sustainable future, as suggested by [72], institutional strategies for sustainable entrepreneurship must focus on both curricular restructuring and ecosystem development: encouraging cross-disciplinary programs that holistically integrate different disciplines is recommended to provide students with the systemic thinking and holistic understanding required to address complex sustainability challenges.

This strategic focus on balancing institutional processes with sustainability directly validates the application of the Triple Bottom Line theory to AI in teacher education. It is a management theory that measures an organization’s success based on its social, environmental, and financial performance referring to three Ps: people, planet, and profit [73]. Framing these findings within educational sustainability clarifies the implications. Sustainable teacher education refers to the ability of systems to adapt to changing social, technological, and environmental contexts. Stakeholder openness to AI suggests significant adaptive capacity, but leadership caution underlines the need for institutional readiness and governance structures that ensure long-term relevance.

To meet the demands of a sustainable future, AI implementation must be viewed through a proactive, long-term perspective, balancing short-term gains against potential long-term risks across the TBL dimensions:

People (social): Teacher beliefs, readiness, and confidence are central to sustainable use of AI in education. Pre-service teachers’ openness to AI-powered professional development directly supports the social pillar, showing that human attitudes are as critical as technology itself. However, long-term social impacts also require explicit strategies to prevent teacher alienation, deskilling, and the erosion of human-centric pedagogical skills. A sustainable model must ensure AI augments teacher capacity rather than replaces professional judgment, thereby securing the long-term value of the teaching profession. AI should be positioned as a co-pilot that handles routine tasks, freeing teachers to focus on high-value human interaction and mentorship.

Planet (environmental): Stakeholders emphasized the ecological costs of AI, including energy consumption and e-waste. Embedding sustainability requires design of AI systems that minimize environmental impacts. Long-term environmental viability necessitates addressing Green AI, using energy-efficient algorithms, prioritizing local, edge computing solutions over large-scale cloud data centers where possible, and instituting clear life-cycle policies for AI hardware to mitigate e-waste [74]. The massive long-term computational demands of large language models (LLMs) must be weighed against their educational benefits.

Profit (financial): While AI can enhance efficiency through automation and analytics, long-term viability requires financial strategies and equitable investment. Without this, resource disparities could undermine sustainability. The economic sustainability of AI hinges on moving beyond initial pilot investments to establish durable funding models. This includes assessing the long-term ROI in terms of reduced teacher attrition and administrative costs and establishing scalable licensing models to prevent the digital divide from widening between well-funded and resource-constrained institutions.

The results of this study show that a sustainable AI system depends on social, environmental, and economic factors, not just technology itself. The research confirms that the success of AI is fundamentally a human issue (people). Findings reveal that pre-service teachers’ beliefs and attitudes toward AI-empowered teacher education is a critical factor in its adoption. Openness and readiness for AI-empowered professional development acts as a significant support to AI’s long-term sustainability. This supports the TBL’s social pillar, showing that human factors like training, confidence, and positive perception are crucial for the system to be effective and long-lasting. Therefore, the findings explicitly recognize the need to address the environmental impact of AI-powered teacher education, a direct link to the TBL’s environmental pillar (planet). The research indicates that successful, long-term AI-empowered teacher education requires “careful consideration of AI’s environmental impacts,” underscoring that the massive energy consumption and potential for e-waste from AI’s computational demands are a real burden in the system’s sustainability. As the third part of the TBL, the financial aspects of such a system (profit) over time are as important as the technology itself. AI-powered teacher training is expected to contribute to long-term social sustainability by improving teacher efficacy and retention; however, financial issues in sustainability require investments in infrastructure and a clear financial strategy in faculties. Without a sound economic plan, the system cannot be sustained.

Stakeholders highlighted smart opportunities where AI enables both innovation and sustainability. Generative AI for curriculum design, intelligent tutoring systems, and video-based analytics can increase efficiency and inclusivity. However, participants consistently emphasized that AI must augment rather than replace human teachers. This human–AI synergy ensures that sustainability encompasses not only efficiency but also empathy and professional values, mitigating the long-term risk of teacher de-professionalization.

When it comes to educational sustainability, AI-empowered teacher training becomes crucial in reference to the ability of teacher education systems to adapt and remain relevant in changing social and technological contexts [75]. By integrating AI into teacher education, institutions can foster long-term resilience through supporting diverse learners and the underserved in teacher training (measurable outcome for SDG 4: Quality Education). Studies on AI in professional development for teachers have demonstrated that these systems can provide personalized and just-in-time feedback to educators based on their performance and needs [76]. A key finding from their study on AI-driven professional development for math teachers showed that a virtual facilitator based on natural language processing was not only effective in improving teacher practices but was also scalable and accessible to educators across the nation, regardless of their location [77]. This ability to reach a large and geographically dispersed teacher audience is crucial for building a sustainable teacher education system, reducing dependency on localized, high-cost human resources. These findings align directly with education for sustainable development, which emphasizes inclusive, equitable, and lifelong learning. Embedding SDG 4 (Quality Education) into the research implications also strengthens this interpretation. AI can advance inclusive and equitable teacher education by offering scalable professional development, personalized feedback, and reduced administrative burdens. For example, AI-driven analytics support early detection of at-risk pre-service teachers, while automation can reduce teacher attrition by making the profession more manageable. These outcomes align directly with SDG 4.4 (skills for work) and SDG 4.c (increasing the supply of qualified teachers).

AI-powered teacher training—through personalized learning, continuous feedback, and intelligent tutoring—supports this goal by ensuring that teacher education adapts to diverse learners and the educational needs of the underserved. This mirrors the research findings of [78] which highlight the power of AI to enhance personalization and scalability in sustainable learning contexts. AI-empowered teacher education can directly contribute to efficiency, making new teachers more qualified in the teaching profession. This can be measured by a 25% increase in teacher self-efficacy scores and a 15% reduction in the time it takes for new teachers to achieve competency in classroom management. Furthermore, by automating administrative tasks, AI tools can help to achieve SDG 4.c by increasing the supply of qualified teachers by making the profession more manageable and attractive, potentially leading to a 10% decrease in teacher attrition rates within the first five years of service [79].

This study found strong stakeholder interest in integrating AI into teacher education, though leadership expressed caution regarding ethics, governance, and resources. Interpreted through the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) and SDG 4 (Quality Education), the findings highlight that AI’s long-term sustainability depends on social acceptance (teacher readiness and professional values), environmental responsibility (reducing energy use and e-waste), and financial viability (equitable investment and efficiency gains). While AI can enhance inclusivity, professional development, and workload management, participants stressed that technology must augment rather than replace human teachers. This central theme of augmentation is the crucial long-term mitigation strategy against the social and ethical risks of AI adoption. Ensuring sustainability therefore requires balancing innovation with empathy, equity, and ecological responsibility, positioning AI not only as a tool for efficiency but as a driver of resilient, future-ready teacher education systems.

4.1. Learning Analytics and Resource Optimization in AI-Powered Teacher Education

The results of this study show strong support for AI’s role in economic sustainability by analyzing large datasets to improve teacher-training efficiency, with particular enthusiasm for identifying “at-risk” pre-service teachers early. This supports [80,81] assertions that machine learning can enhance targeted interventions and early risk detection. However, the findings of this study extend the findings of [4] by showing that stakeholders not only value risk detection but also see simulation of outcomes (e.g., graduation rates, attendance, and recruitment success) as a resource optimization strategy. This dual emphasis—diagnosis plus projection—suggests AI adoption could reduce inefficiencies in teacher preparation within the scope of sustainability, especially in resource-constrained settings, aligning with the vision of AI [82] as a proactive support tool rather than a reactive measure. By identifying “risky” pre-service teachers early on and simulating outcomes like completion rates, AI can help economic sustainability and optimize the allocation of resources. This means less time, effort, and financial investment are wasted on individuals unlikely to succeed, leading to a more sustainable use of educational resources over the long term. The use of AI is framed as a strategic necessity for institutional resource optimization and early risk detection in teacher education. AI’s primary operational role should be to facilitate the timely identification of pre-service teachers exhibiting risk indicators, thereby enabling the deployment of precise and targeted interventions. However, stakeholders fundamentally assert that AI algorithms must not operate as autonomous decision-making tools. Stakeholders strongly emphasize that AI algorithms, which are susceptible to reflecting social biases present in their training datasets, must not operate as autonomous decision-making tools. Consequently, human support is deemed essential to ensure fairness and equity in outcomes. AI’s role should therefore be restricted to augmenting human-led decisions and faculty decision-making by providing objective, analytical data. The final responsibility for guidance, intervention, and evaluation remains vested in qualified human faculty members and educational psychologists. This model of human–AI synergy is fundamental to preserving the human-centric core of teacher training.

Stakeholders also highlighted the value of video-based analytics [50,54] for performance feedback, which is consistent with [14]’s findings on behavioral data use for enhancement. Our study suggests that, in practice, such tools could deepen self-reflection and mentorship processes, reinforcing the argument of [83] that AI supports innovation and transformation in higher education. This coherence across studies strengthens the case for AI-enabled analytics as both a pedagogical and equity-enhancing intervention. According to AI experts and curriculum developers, education faculties should have access to AI to conduct their needs analysis by gathering and analyzing data from multiple sources (pre-service teachers’ grades, academicians’ comments, internship school records, and other institutions’ reviews or references). Additionally, AI-powered teacher training should provide learning analytics such as participant performance, successfully completed courses, engagement level, teacher educators’ feedback, and behavioral metrics including participant learning profiles. Understanding factors contributing to poor performance [4] allows for precise interventions. This reduces the need for broad, resource-intensive solutions that may not be effective for all. Ref. [4] suggests educational psychologists should create algorithms guided by data in order to accurately identify learners who will perform poorly in a course by tracking the early learning events of high and low performers. As claimed by [81], these data can be utilized to identify and help pre-service teachers who are at risk in their courses who might struggle otherwise, sometimes going unrecognized. Much of the AI work in teacher education focuses on the analysis of behavioral data collected by observing and recording behavior [14]. Specifically, in practical courses covering topics like content development, classroom reinforcement strategies, and the use of facial expressions, pre-service teachers can receive video-based feedback powered by AI [50]. As strongly emphasized by department heads, teacher education faculties should harness the power of AI to deliver deeper insights to pre-service teachers through learning analytics tools such as Vosaic for in-class observations, mentoring, peer feedback, and unbiased AI-generated evaluations. Learning analytics in teacher education can serve Education for Sustainable Development by providing data-driven insights that improve educational efficiency and personalize learning pathways. This data-driven approach helps in identifying successful strategies in teacher education, which is essential for managing complex global challenges for a sustainable future.

The findings of this research define smart opportunities as the capabilities of AI to advance both technological innovation and sustainable teacher development goals. In other words, “smart” opportunities should enable equitable access, resource optimization, and resilient institutional practices—not just enhance functionality. As implied by [80], their study results reveal that the integration of AI in higher education can facilitate progress by promoting innovation, equality, and digital literacy. From a sustainability standpoint, these AI-driven practices promote long-term capacity building by providing scalable, data-informed support for teacher growth, especially in underserved environments. By reducing reliance on human-intensive assessment processes and enabling continuous, personalized feedback loops, AI helps make teacher training more transformative and equitable. Furthermore, AI tools such as Knowledge–Behavior–Social Dashboard, Code.org, TraMineR, support-vector machine classifiers, IBM Watson speech recognition, and Chart.js for data visualization [14] support the cultivation of core teaching competencies like classroom management and addressing diverse learner needs [53]. These innovations not only improve instructional quality but also contribute to the sustainability of teacher education systems by optimizing learning outcomes.

4.2. Automated Curriculums, Smart Content, Intelligent Tutoring, Human Teacher–AI Synergy in AI-Powered Teacher Education

The findings of this study indicate that AI can automate many processes including development of automated curriculums. As implied by curriculum developers and AI experts in particular, AI has the potential to create automated smart curriculums based on data-driven analytics derived from current global innovations, faculty members’ customized feedback, and pre-service teachers’ instant needs. Automated curriculum creation is one of the things about AI that excites curriculum developers most. AI can assess how to improve teacher education curriculums and identify global new emerging competencies and content areas. Ref. [6] stresses that AI-based solutions will help universities to create international curriculums based on the concept of the automated curriculum. A better curriculum is also a form of capital. Data mining and automated curriculum-making with AI ensures the sustainability of this intellectual capital in delivering teacher training and can create a smarter and more productive system. Artificial intelligence can transform how people create content, increasing pre-service teachers’ productivity. As emphasized by AI experts, AI in teacher education has the capability to simulate human-teacher creativity and generate original content. Ref. [84] implies that AI can currently enable teachers to spend less time on routine tasks and more time on qualified teaching interactions. They stress that AI capabilities reported in other sectors can be extrapolated to the teacher education sector as well (14% increase in worker productivity, a great impact on novice and low-skilled workers). As one of the most significant predictors, perceived institutional AI support suggests that teachers should have the appropriate AI support; AI could be used to help novice teachers become better content creators. Pre-service teachers and department heads stress that pre-service teachers are overwhelmed by repetitive tasks while preparing content. AI will relieve teachers’ workload and burnout. Education faculties should leverage generative AI tools such DALL-E, Casper AI, and Github Copilot to create content that can summarize complex content. This study also found that pre-service teachers trust AI to act as a content creator and as a co-creator. Ref. [85] explains the process as “from digital natives to the AI empowered”. As educators explore, learn, and collaborate with AI, they may use these ideas to apply generative AI to the creation of lesson plans, rubrics, how-to-teach activities, exam questions, and more. This efficiency is directly aligned with ESD’s goal of transformative learning. By saving time on routine work, teachers can dedicate more energy to fostering a deeper, more hands-on learning experience for students.

This study also indicates the need for integration of intelligent tutoring into teacher education. Although not yet included in teacher training, smart assistants, chatbots, and smart suggestions have begun to be used at different school levels. According to Ref. [86], an important component of artificial intelligence is smart assistants. They can be used to help guide pre-service teachers, giving them feedback 24/7, suggesting tailored content, and providing better training [13]. As a good practice, eTeacher is designed as a system to provide personalized assistance by monitoring learners’ behaviors as they interact with course materials and generating a learner profile. It is used to personalize learners’ course interactions, particularly in high school education contexts [15]. Likewise, in intelligent tutoring in education faculties, such a system could offer customized professional development suggestions in addition to personal action plans. Intelligent tutoring should rely upon comprehensive educational data for educational data mining, data visualization, recommender systems, and personalized adaptive learning [14]. Expanding pre-service teacher mentorship procedures, chatbots are employed by [51]. They created two chatbots, LitBot and FeedBot, that offered personalized assistance for pre-service teachers’ independent study skills, particularly to deal with seminar literature and suggested readings. Chatbots perform better with large classes; however, they perform worse than one-to-one human tutors [53].

This study explores the role of human–AI synergy in sustainable teacher education. In line with [68] and the subsequent literature, we argue that smart opportunities for AI in teacher education should be defined not only by technological innovation but also by their contribution to value creation, efficiency, and sustainable development goals. As an example, AI-powered systems assist both the cognitive and emotional components of learning [87]. This is supported by [88], which emphasizes synergy between teachers and trustworthy AI, suggesting that institutions can adopt AI-enabled tools without compromising the human-centered core of teaching. Our findings reinforce this model: stakeholders generally view AI as a facilitator of pedagogical innovation in teacher training, not a replacement for human interaction which is the affective core of the teacher profession. Artificial intelligence’s fundamental optimal use is a process wherein responses created by AI are directed by humans [89]. This study has discovered that AI is not a rival to teachers but instead serves as a co-creator and strong driver for pedagogical innovation. It can never replace the genuine care of a human teacher, for the profession’s essence is deeply rooted in the irreplaceable bonds of human touch. This focus on synergy is a long-term social strategy designed to maintain the integrity of the teaching profession while leveraging technological gains.

4.3. Assessment Capacity and Recruitment in AI-Powered Teacher Education

This study also indicates that AI can support pre-service teachers in dealing with complex problems in terms of assessment and evaluation capacity. AI work depends on the assumption that “any aspect of intelligence can in principle be described that a machine can simulate it” [90]. As emphasized by department heads and AI experts, AI can improve assessment preparation by simulating a teacher’s assessment performance. AI’s capability to support pre-service teachers in complex assessment and evaluation tasks contributes significantly to the sustainability of educational practices. Traditionally, assessment and evaluation are labor-intensive. By automating tasks like essay grading with tools such as M-Write or StudyGleam [91], AI frees up valuable human resources—teachers’ time and effort. This allows educators to focus on more specific aspects of teaching, such as individualized feedback and creative lesson planning, optimizing the use of their expertise. This efficiency reduces the “cost” in terms of human capital, making the assessment process more economically sustainable. AI can move beyond one-time assessments to provide continuous evaluation of performance [2]. This “renaissance in assessment” [47] enables earlier identification of learning gaps and allows for timely interventions. Despite all these opportunities, warning signs exist. While embracing AI technologies, it is necessary for teachers to manage the threats to curiosity, imagination, and discovery—fundamental aspects of human work.