Abstract

The application of the same global legal regulations to areas with different climates, landscapes, and cultural and urban conditions may ultimately lead to decisions that are unsuitable for the region, which could result in poor investment and development decisions for the municipality. This article examines how sustainability regulations established locally, in response to local conditions, differ from global regulations created without considering the differences between the areas to which they apply. Selected criteria were assessed in relation to global and local regulations, and then, based on these criteria and their weights, rankings of the strengths and weaknesses of municipalities were proposed in relation to the selected criteria, the weights of which were evaluated depending on the adopted global or local regulations. The AHP method was used to conduct this multi-criteria assessment, based both on expert group opinions and artificial intelligence tools. The aim of this analysis was to demonstrate differences in the hierarchies of sustainable development aspects implemented globally and locally, as well as local conditions. The assessment results indicate discrepancies between expert knowledge, which takes into account local conditions, and the priorities resulting from general legal regulations. Some areas important from a local perspective, such as building density or mixed-use development, are insufficiently addressed in legal regulations, both under Polish and EU law and local law. This also contradicts current trends in urban planning theory, which advocates a shift away from zoning. Others, such as energy efficiency in buildings and renewable energy sources, are strongly present in both national and EU law but are not implemented in local regulations.

1. Introduction

The development of civilizations and cities over the centuries has been determined by energy consumption. In the world’s most developed countries, we observe higher per capita energy consumption than in less developed countries [1].

It is difficult to assume that developed countries will be able to reduce this consumption without compromising quality of life. Energy demand will increase with increasing technological development, leading to the development of renewable energy production.

Local spatial planning acts (i.e., local spatial development plans, general plans, studies of the conditions and directions of the spatial development of the municipalities), national law (acts and regulations), and European Union regulations (directives of the European Parliament and the Council) regarding sustainable development and energy efficiency should be tailored to local circumstances, not global ones. This approach is necessary because European countries differ significantly in terms of climate, landscape, resource availability, and potential for generating energy from renewable sources. To illustrate this, in this study, we conducted research in municipalities in Poznan County and assessed the area against specific criteria. We weighted these criteria based on expert assessment, assessment based on global EU regulations, and assessment based on Polish and local law to compare them and demonstrate that the results differ. The legal regulations referred to have been detailed in Section 3 (Materials and Methods) and Section 3.1 (Research Material).

The problem pertaining to communes around Poznan is uncontrolled urban sprawl [2], which results in a suboptimal spatial distribution of functions. As a result, services important for inhabitants, which influence quality of life, are not provided [3]. The problems include a lack of commercial services, educational institutions, workplaces, and recreation and leisure areas within an accessible range, necessitating commuting to such facilities [4]. Dispersed development, along with insufficient transportation infrastructure and low accessibility of public transport, hinders traffic access. This leads to waste of time, energy losses, and higher fuel consumption for commuting [5]. All these issues influence the social needs of inhabitants, which is why they should be considered in commune governance. Furthermore, these factors have ecological significance for energy consumption, quality of air, water resources, biodiversity, etc. Therefore, concern for the proper development of the commune and sustainable development is in line with global trends and sustainable development goals. The factors mentioned above relate to sustainable development adapted to local conditions [6]; therefore, they were assessed in this study.

Taking all of the above into account, we observed that problems and conditions are so individual and territorially diverse that adapting solutions to sustainable development goals requires taking these differences into account in legislative documents and development planning. Therefore, this article examines how the same criteria are weighted depending on whether global or local regulations are applied. To support this analysis, rankings based on selected municipalities in the Poznan district are presented. The main research objective is to demonstrate the disparities between local and global approaches to formulating sustainability and energy efficiency requirements for municipalities, and subsequently to identify areas that require improvement in this regard.

In this study, communes in Poznan County were ranked by energy efficiency [7], to be able to assess which areas of sustainable development are insufficiently taken into account in individual municipalities, and which should be strengthened. The criteria on which the ranking was based refer to matters of transportation, function, energy efficiency, buildings, greenery, and social participation. We used QGIS software (version 3.40.7 Bratislava) for data collection [8] and the AHP multi-criteria decision analysis method for the assessment. We involved architecture students and gathered data on their rural practices to assess the actual situation in 17 communes around the city of Poznan. This research may be helpful in decision making about the locations of future investments in municipalities. The data obtained about the commune are assessed according to selected criteria; however, the weights of these criteria may differ depending on which type of legal regulations they were based at the time of assessment: global or local. This means that rankings for the same municipality may differ despite using the same criteria during evaluation, depending on the regulations on which the assessment is based: global or local.

The entire study is described in detail in the following chapters. Section 2 presents the state of the art, taking into account contemporary ideas in urban planning, particularly those related to suburban areas, the impact of urban design on energy efficiency and sustainability, and a review of similar studies to date. Section 3 provides a detailed description of the research material—17 municipalities located in the suburban area of Poznan, along with data sources and methods of data collection, and the methodology applied—specifically, the use of the AHP method in four scenarios: local conditions assessed by experts, local spatial planning regulations, Polish law, and European Union regulations assessed using AI tools. The results, including the hierarchy of sustainable development and energy efficiency criteria across the four scenarios, as well as rankings of the municipalities according to each scenario, are presented in Section 4. Section 5 includes the discussion: it addresses the limitations and shortcomings of the presented study, interprets the results, and proposes directions for future research.

2. State of the Art

2.1. Contemporary Urban Planning Ideas for Suburban Zones

There are many models and concepts of spatial and urban planning, just as there are many examples of urban space development. In this chapter, urban planning theories have been cited to emphasize the importance of implementing them in legislation, which, unfortunately, is often overlooked, as in the case of functional zoning, for example. This subsection will discuss urban planning concepts primarily focusing on suburban areas, as the studies presented in the article pertain to this type of region.

The 15-min city by Carlos Moreno is a concept that promotes sustainable urban living, encourages changes in the habits of automobile-dependent city residents, and maximizes the social benefits of living in a human-centric city. Everyday essential services like schools, stores, and offices should only be a short walk or bike ride away from home. This will reduce reliance on cars and enhance community well-being [9,10].

Zwischenstadt (literally “in-between city”) is a phenomenon observed and defined by German architect and urban planner (also planning theorist) Tom Sieverts. According to his observation, the open countryside was subject to a profound transition, from being the background of the city to being a figure in itself. Urban planning scholarship and practice in Europe that had been largely critical of the urban prospect in the 1950s and 1960s, when cities were seen as centers of economic and social crisis, had changed their tone in the final decades of the twentieth century to normatively re-appreciate the dense, compact, and central “European city” as a cultural, ecological, and social example for future urban development. Sieverts’s Zwischenstadt questioned the assumptions at the basis of this re-evaluation and demonstrated that the European city center, if it even still existed in the way it was portrayed, was in fact only part of an emerging urban landscape that stretched over a regional scale and beyond [11,12,13,14,15,16].

New Urbanism is a planning and design theory that emerged in the early 1980s in the United States. It aims to create environmentally friendly, walkable communities that integrate various types of housing, jobs, and public spaces. It was supposed to be a remedy for the unfriendly-to-humans, radically organizing modernism and the negative effects of urban sprawl. This movement was participated in by the renowned architect, planner, and urbanist Leon Krier, recognized as one of the leading representatives of the principles of New Urbanism, which he implemented in his works [17]. His most famous project is the development of the town of Poundbury in the United Kingdom [18]. It promotes a return to traditional neighborhood designs that prioritize human scale and community engagement. Key principles of New Urbanism include walkability, mixed-use development, connectivity, diversity, quality architecture, and urban design [19,20].

In Poland, in 1983, a team led by architect and urban planner Jerzy Buszkiewicz designed the Zielone Wzgórza housing estate in the town of Murowana Goślina near Poznań. This residential complex features shops, schools, and all necessary infrastructure for daily living, all within walking distance, shaped in the manner of a small town. Its heart is a square surrounded by colonnaded tenement houses, with a central building resembling a Renaissance town hall capped with a tall tower. This project serves as an excellent example of the principles of New Urbanism. A contemporary developed example in Poland is the Siewierz-Jeziorna settlement project [21].

An Edge City refers to a concentration of businesses, service and commercial facilities, and entertainment on the outskirts of a traditional city center or business district, in an area that was previously suburban, residential, or rural. This phenomenon has often resulted from the development of housing estates in areas outside the city center, the migration of residents from the city center to the suburbs where real estate costs were lower, and the development of road infrastructure. The term was popularized by journalist and author Joel Garreau in his 1991 book Edge City: Life on the New Frontier. Garreau argues that the Edge City has become a standard form of urban growth worldwide. Other terms for these areas include suburban activity centers, mega-centers, and suburban business districts. These districts have now developed in many countries [22].

In the Smart Cities concept, new technologies are employed to improve the quality of life for residents within the urban area. The concept and how it has evolved, along with the aspects that have gradually begun to be emphasized, have allowed us to observe four generations of smart cities. Smart city 1.0: a city inspired by available technologies; Smart City 2.0: a city with a decisive role for public administration; Smart City 3.0: a city based on the creative involvement of its inhabitants; Smart City 4.0: a city that takes advantage of the opportunities offered by sustainable development [23].

By introducing just a few concepts, it can be seen how diverse the approaches to the issues of designing, revitalizing, and engaging cities and suburban zones can be. It is crucial to adapt the method to the actual needs of a specific city at a given time and place. Furthermore, it is important to anticipate future developments and changing needs. The primary task of municipal authorities is to familiarize themselves with these models and to distill the most valuable processes and features from the chosen concept to align with local needs.

Moreover, it can be observed that the urban layout and the planning concepts of suburban area development influence the energy efficiency of residential estates, technical infrastructure, and, more broadly, the entire municipality. After approximating the planning concepts by moving from the general to the specific, the next subsection will discuss concrete solutions that impact energy efficiency in spatial planning and construction.

2.2. Energy Efficiency in Urban Planning

Energy efficiency in buildings and urban areas is determined not only by technological and material solutions, but also by spatial planning-related conditions. The impact of urban design and spatial planning on energy efficiency may be considered from multiple perspectives and varies depending on geographic location and climatic conditions. The most significant factors influencing energy performance can be identified across several key aspects of urban planning described below.

Urban Morphology. Beyond the technical and material solutions, the spatial layout itself may significantly contribute to the energy performance of buildings [24]. It may also affect both energy losses and gains (i.e., solar passive heat gains).

The compactness of buildings is crucial for the amount of heat transmitted through the building envelope. A lower A/V coefficient, which determines the ratio of the surface area of the building’s external envelope to its volume [25], allows for a reduction in heat losses through transmission, but also limits the embodied energy utilized in the construction and insulation materials [26]. A high degree of dispersion of the built environment, which is a common problem in suburbs affected by urban sprawl, may lead to increased costs of infrastructure networks [27]. Improper locations of developments in relation to urban cores, infrastructure, and services, especially the lengths and configurations of utility networks (e.g., water, sewage, district heating, and electricity), influence both construction and exploitation costs caused by energy losses in transmission.

Building arrangement and street layout are important factors for mutual shading and ventilation patterns [28]. The orientation of buildings in relation to cardinal directions is crucial for passive solar gains and daylight availability, which are taken into consideration in many energy efficiency certification standards, e.g., the Passive House Standard [29]. The research to date also shows the impact of greenery in the direct vicinity of building facades as a factor useful for reducing overheating in the summer [30].

Functional Structure and mixed land-use. The functional composition of urban areas affects the mobility patterns, energy use profiles, and efficiency of the infrastructure. Contemporary urban planning ideas (such as 15 min cities and New Urbanism) tend to introduce land-use diversity (residential, commercial, public services, recreational) and avoid monofunctional districts with uneven temporal use, which was the basis of modernist urban planning ideas underlying functional zoning. Contemporary studies show benefits from promoting the continuous and intensive use of buildings and public space throughout the day, and the integration of living, working, and leisure spaces to reduce commuting distances [31].

Mobility and Transportation Accessibility. This topic is strongly connected with the functional structure and mutual relationships between housing and workplaces, as well as other daily activities [32]. Transport-related energy consumption is significantly influenced by the spatial configuration of cities and the accessibility of transportation networks. Key factors shaping sustainable mobility include the quality and coverage of public transport systems, the walkability and bikeability of urban environments [33,34], and the degree of intermodal transport integration. Access to means of mass transit plays a vital role in ensuring social equity, reducing car dependency, thereby decreasing fuel consumption and air pollution [35], while simultaneously enabling all population groups—particularly those without access to private vehicles—to participate fully in urban life. The development of infrastructure for low-emission and electric mobility is also essential for mitigating environmental impacts and supporting the transition toward more sustainable urban transport systems [36].

Integration of Energy Systems and Renewable Energy Sources. This category refers to the spatial and infrastructural capacity of urban areas to support low-emission, zero-emission, and decentralized energy systems [37]. The patterns of urban structure may affect the availability of space and conditions for renewable energy installations (e.g., photovoltaics, geothermal, biomass), which require possibilities and appropriate conditions for connection to the network, but are also subject to certain restrictions regarding the vicinity, e.g., distance from residential buildings or protected areas [38].

A major challenge arising with the development of renewable energy sources is their integration into one coherent and stable energy system. However, this is also an opportunity to increase efficiency and reduce greenhouse gas emissions in urban areas. The efficiency of energy transmission infrastructure is influenced not only by its technical ability, but also by its adaptability to local conditions and energy demand characteristics. Research is underway on the implementation of smart grids, energy storage technologies, and demand-side management systems, contributing to the creation of a more dynamic and responsive energy grid [39]. In this context, long-term planning for resilient and flexible energy infrastructure is essential [40].

Green and Blue Infrastructure. Natural elements embedded in the urban fabric, often referred to as green and blue infrastructure, play a fundamental role in moderating microclimatic conditions and contributing to energy efficiency [41]. Urban green spaces, tree canopies, strip buffers, etc., help lower ambient temperatures and therefore are crucial for mitigating the urban heat island (UHI) effect [42,43]. Green roofs and vertical greenery not only provide insulation benefits but also support biodiversity and stormwater management [44]. Similarly, the presence of water bodies, wetlands, and water retention systems enhances urban climate regulation through evaporative cooling [44].

Planning Policies, Regulations, and Governance. Institutional frameworks are critical in guiding the implementation of energy-efficient spatial strategies [45]. However, the detailed regulations referring to architectural form (e.g., glazed area ratio, share of biologically active areas and green roofs) may also influence the energy performance of buildings. Effectively implementing these strategies and regulations requires a coherent approach at various planning levels and in specific areas [46]. It is extremely important that the above-mentioned key aspects be taken into account when assessing the development of the municipality and when making strategic decisions regarding its growth and sustainable development of the commune. The topic of evaluating communes, settlements, and evaluation criteria has already been studied in scientific environments. In the next chapter, selected examples will be discussed.

2.3. Similar Research to Date

Creating rankings and positioning settlements are a highly developed discourse in various scientific environments. Comparative analysis of municipalities is intended to enable a reliable collection of data on municipal planning strategies, popularize and promote sustainability, and contribute to the development of methods for measuring sustainability performance. The authors of [47] use 260 indicators from the Sustainable Cities Program to create sustainable indicators for small Brazilian municipalities. The indicators presented in the research focus heavily on aspects of quality of life and economic, educational, and development indicators. L’opez-Penabad et al. created a rural development index (RSDI) for Galician municipalities (Spain) to stop the depopulation of rural areas [48]. The results of their research show, among other things, the impact of mountainous terrain and a lack of infrastructure and services on the depopulation of the areas studied. Nagy et al. used the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicators to verify the degree to which the Sustainable Development Goals had been achieved [49]. During their research, they encountered a problem with obtaining data, which is a common obstacle in this field. Old reports, incomplete data, or a lack of access to information can lead to distorted results or the complete abandonment of research. To avoid such a situation, Nagy et al. [49] used the statistical databases of the National Institute of Statistics (NIS) and obtained some data during telephone conversations with the local mayor’s office. Despite the limitations, the results presented in the paper show the progress made by the municipalities in achieving the SDG. As a result, Nagy et al. show that the central urban core municipality is the closest to achieving the SDG, while the rest of the municipalities mainly show lower indicators as we move away from the urban core. The authors emphasize that their results indicate a strong need to mobilize efforts towards achieving SDG 2030. As a result of creating SDG indicators based on sustainability, inclusiveness, safety, and resilience, researchers Diaz-Sarachaga and Jato-Espino created the RESSICOM tool [50]. The selection of indicators was based on literature research, which resulted in the identification of 61 balanced indicators. The results of the research were applied in Mexico City to verify the city’s planning commitments in relation to the principles of sustainable development. Research shows that Mexico City is not sustainable. SDG indicators are also used by Lopez-Penabad et al. [48] The requirements in addition to the definition and methods of using SDGs are emphasized by Martyka et al., who emphasize the need to consider sustainability not in four sectors but in five [51]. They propose expanding the essential SDG areas of economic, development, social, and environmental to include spatial planning. Using a ranking of rural communes in the Podkarpackie region of Poland, the authors indicate in which directions the communes are developed and in which they require a change in approach in order to achieve the desired SDG.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Material

As research material, several datasets related to various aspects of development in the municipalities in Poznan County were used. Poznan County contains 17 municipalities, including 7 rural municipalities, 8 mixed urban–rural municipalities, and 2 urban municipalities (containing only single towns). In order to make them comparable, urban municipalities were merged for statistical purposes with neighboring rural or urban–rural municipalities. As a result, for the purposes of comparison, 15 statistical units (Figure 1) were created:

Figure 1.

Statistical municipality units adopted for research [source: own work].

- Buk (urban–rural municipality);

- Czerwonak (rural municipality);

- Dopiewo (rural municipality);

- Kleszczewo (rural municipality);

- Komorniki (rural municipality) + Luboń (urban municipality);

- Kostrzyn (urban–rural municipality);

- Kórnik (urban–rural municipality);

- Mosina (urban–rural municipality) + Puszczykowo (urban municipality);

- Murowana Goślina (urban–rural municipality);

- Pobiedziska (urban–rural municipality);

- Rokietnica (rural municipality);

- Stęszew (urban–rural municipality);

- Suchy Las (rural municipality);

- Swarzędz (urban–rural municipality);

- Tarnowo Podgórne (rural municipality).

The research material consists of data collected during student summer rural practices in the academic year 2023/2024 on the location of basic services in the municipalities of Poznan County. These data were used to assess several criteria and were collected in two forms:

- Spreadsheet files (.xlsx or .csv) containing the geographical coordinates of the service locations in the EPSG:900913 Google Maps Global Mercator coordinate system;

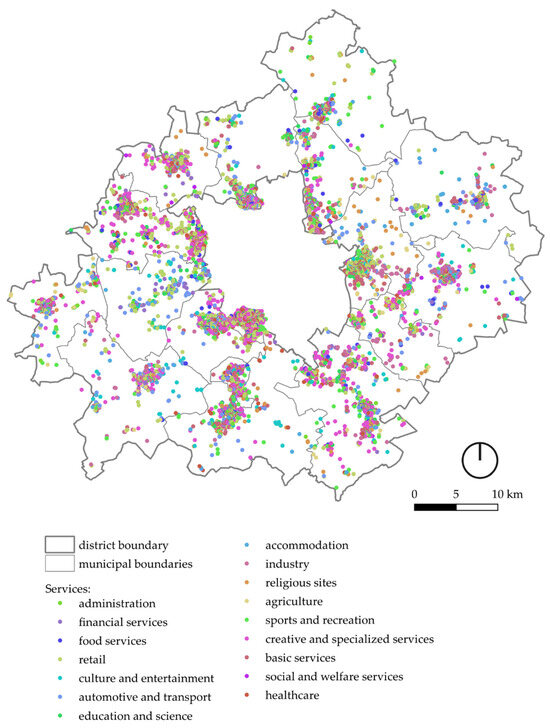

- The GIS spatial database, containing spatial data of the service locations in the EPSG:4326 WGS84 coordinate system, developed using the QGIS program (version 3.40.7 Bratislava) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of services in Poznan district [source: spatial data collected by students of the Faculty of Architecture of PUT during summer rural practices].

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of services in Poznan district [source: spatial data collected by students of the Faculty of Architecture of PUT during summer rural practices].

Other spatial data available from the spatial information systems of the municipalities and Poznan County were additionally used in this research, in particular:

- Land and building records;

- The road network;

- The public transport network;

- The designation of areas for residential and service functions in local spatial development plans, and a study of the conditions and directions of the spatial development of municipalities.

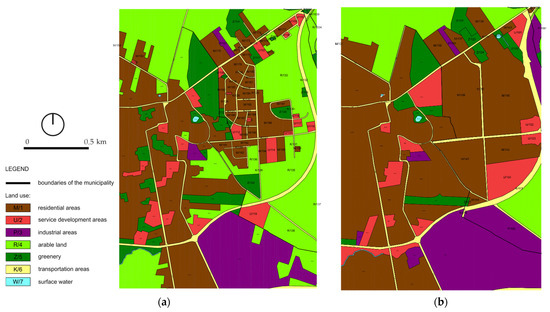

Spatial data on the actual use of areas for residential and service functions was obtained from, among other work, studies carried out as part of student summer rural practices in the academic year 2020/2021 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Land use in the municipality of Buk: (a) actual [source: spatial data collected on site by students of the Faculty of Architecture of PUT during summer rural field practices]; (b) according to the study of the conditions and directions of the spatial development of the municipality of Buk [52] [source: spatial data collected by students of the Faculty of Architecture of PUT during summer rural practices based on applicable studies of the conditions and directions of spatial development of the communes [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68].

Data about building energy efficiency were collected from the central energy certificate records (Centralny rejestr charakterystyki energetycznej budynków, https://rejestrcheb.mrit.gov.pl, accessed on 1 November 2024).

Community participation and governance: Data for the assessment under this criterion were obtained from the municipality’s website and directly during telephone conversations with the municipal office, consisting of verifying whether participatory budgets are provided for each municipality and whether the community submits projects. The research covers the previous budget period for the year 2024/2025.

Pollution reduction strategies: To evaluate municipalities based on pollution reduction strategy criteria, data collected throughout the year from air quality monitoring stations in individual municipalities were compiled. Air quality data were collected from the website of the Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (Air Quality Assessment—Current Measurement Data—GIOŚ (Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection) and [https://aqicn.org/map/poznan/pl, accessed on 1 November 2024]). The research covers the period for the year 2024.

Data about transportation network/public transport accessibility were collected from GUS—Central Statistical Office (Główny Urząd Statystyczny).

Data about urban density were collected from spatial databases of the land and building records of Poznan County.

AI was used to assess EU regulations, Polish law and standards, and local law using certain documents. The first assessment was made by artificial intelligence based on the following Key EU Documents: European Green Deal (COM/2019/640); EU Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EU, amended 2023); EU Taxonomy Regulation (EU 2020/852); Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) (2023/2413); Fit for 55 package; Urban Agenda for the EU; New European Bauhaus; Smart Cities Marketplace; EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030. The second assessment was made by artificial intelligence based on Polish law (KPEiK—Polish National Energy and Climate Plan 2021–2030; Krajowa Polityka Miejska 2030—National Urban Policy 2030; PEP2040—Energy policy of Poland until 2040; Prawo ochrony srodowiska—Environmental Protection Law; Act on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels; Strategy for Sustainable Development of Transport 2030; Act on Spatial Planning and Development; Strategi Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Energetycznego—Climate Policy of Poland). The third assessment was based on the Local Law of the City of Poznań—BIP resolutions (https://bip.poznan.pl/bip/uchwaly/; https://www.poznan.pl/mim/main/-,p,22550,22551,22560.html, accessed on 8 November 2024).

3.2. Research Methods

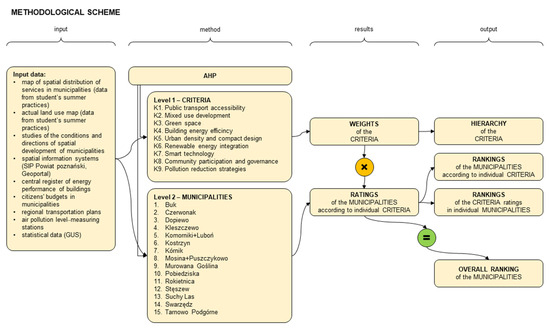

The energy efficiency of the municipalities was assessed in a multi-criteria fashion using the AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) method (AHP Decision for Mac version 1.1.0 Apple software) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Methodological scheme of the research [source: own work].

Nine criteria were selected to assess the energy efficiency of municipalities as part of sustainable development. These criteria were established based on an analysis of the most frequently appearing keywords in 1000 scientific articles on the topic of sustainable development, regarding criteria related to urban planning that influence energy efficiency in communes, searched using the Scopus AI tool. The received issues were grouped into the following nine criteria:

- K1.

- Public transport accessibility;

- K2.

- Mixed use development;

- K3.

- Green space;

- K4.

- Building energy efficiency;

- K5.

- Urban density and compact design;

- K6.

- Renewable energy integration;

- K7.

- Smart technology;

- K8.

- Community participation and governance;

- K9.

- Pollution reduction strategies.

Data on the individual criteria for each municipality were calculated and collected as follows:

K1. Public transport accessibility. Data were collected from GUS—Central Statistical Office (Główny Urząd Statystyczny). The evaluation was based on the number of bus stops per resident in the given municipality, using data from 2018–2024.

K2. Mixed Use Development and K7. Smart Technology. The study covered selected services provided in the Poznan Region, divided into individual municipalities. The services were isolated from a set of 223 types, which were grouped according to individual categories: religion; health and medicine; basic commercial services; basic services; mixed commercial services; creative services; banking services; automotive services; cultural, sports, accommodation, official, gastronomic, school, agricultural, social, and industrial services. In order to identify the number and location of a given service in the specific municipality, an inventory of the area was made using geolocation on the map. The study used geolocation data from the Google Maps portal, which was verified through walk-through surveys of individual municipalities. A total of 120 students in the sixth semester of Architecture at Poznan University of Technology took part in collecting data on the location of functions in Poznan district. The data were collected in July 2024. The collected data were placed in a table, which was used to develop numerical data—in particular, a numerical breakdown of all services in a given category with each of the municipalities of the county. The resulting database of 8786 services, together with geolocation data, was used to create maps of spatial data in the QGIS program. The service figures were used to determine the energy-saving-city indicators in the categories K2—Mixed Use Development and K7—Smart Technology. The figures for K2 and K7 for each of the municipalities were summarized, and then, the formula was used to normalize the min–max values.

K3. Green Space. Data collected in July 2021 by students in the sixth semester of Architecture at Poznan University of Technology were used to calculate the K3 index. Information on the size of green areas and the number of inhabitants was collected for a given municipality. Data on the size of green areas per inhabitant were obtained. The received data were normalized, thus obtaining the expected index.

K4. Building energy efficiency. Building energy efficiency was assessed based on data from the Central Register of Energy Performance of Buildings (pol. Centralny rejestr charakterystyki energetycznej budynków, https://rejestrcheb.mrit.gov.pl, accessed on 1 November 2024), access date 1 November 2024—the certificates available to date covered 15.48% of existing buildings, including mandatory certificates for all buildings newly commissioned after 28 April 2023. The register contains data on all the energy performance certificates of buildings in Poland. An energy performance certificate is a document specifying the energy performance of an existing or commissioned building, i.e., a set of data and energy indicators of a building or part of a building, specifying the total energy demand necessary for its intended use. The certificate contains values of the annual demand for usable energy, final energy, and non-renewable primary energy, as well as the unit CO2 emissions and share of renewable energy sources in the annual demand for final energy.

For comparison, the index of annual demand for non-renewable primary energy EP [kWh/(m2 × year)] was chosen. The primary energy index was calculated according to the methodology included in the Polish Regulation of the Minister of Infrastructure and Development on the methodology for determining the energy performance of a building or part of a building and energy performance certificates.

K5. Urban density and compact design. Data about urban density were collected from spatial databases of land and building records of Poznan County (Powiat poznański—System Informacji Przestrzennej, https://poznanski.e-mapa.net/, accessed on 8 November 2024). The urban density index was calculated for the geographical unit of reference defined by a square grid of 500 × 500 m as a ratio of built-up area to land area.

where

- is the urban density index;

- is the total built-up area of all buildings in a unit of reference;

- is the land area of a unit of reference.

The compact design is related to the distribution of the development. Built-up areas may be concentrated or evenly distributed within the commune area. The more concentrated the distribution of buildings, the higher the index of compact design in the commune. The compactness of the building can be calculated as a measure of uneven distribution. For this purpose, the Gini coefficient was used as a measure of the compactness of development in each commune:

where

- is the Gini coefficient of the distribution of buildings in a given commune;

- is the value of the urban density index in the i-th geographical unit of reference;

- is the total number of geographical units of reference in a given commune;

- is the average value of the urban density index in a given commune:

K6. Renewable energy integration. Renewable energy integration was evaluated based on data taken from the Central Register of Energy Performance of Buildings, regarding the share of renewable energy sources UOZE [%] in the annual demand for final energy EK [kWh/(m2 × year)].

K7. Smart technology. Information about the intensity of the use of smart technologies in individual municipalities was collected during rural student practices in July 2024 and measured based on the number of creative industry and smart technology institutions present.

K8. Community Participation and governance. The most important parameter within the Community Participation and Governance criterion is considered to be the engagement of local communities in bottom-up actions aimed at improving the quality of life of residents. The main activity that enables such bottom-up actions is the submission of projects by residents to the civic budget as part of a competition within a single municipality. Data for the assessment of the commune under this criterion were obtained from the municipality’s website and directly during telephone conversations with the municipal office, consisting of verifying whether participatory budgets are provided for each municipality and whether the community submits projects. The research covers the previous budget period for the year 2024/2025.

K9. Pollution reduction strategies. To evaluate municipalities based on pollution reduction strategy criteria, data collected throughout the year at air quality monitoring stations in individual municipalities were compiled. Air quality data were collected from the website of the Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (Air Quality Assessment—Current Measurement Data—GIOŚ (Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection) and [https://aqicn.org/map/poznan/pl]). The research covers the period for the year 2024.

Data normalization. In order to make different criteria comparable, all values were converted into ratings normalized to the range [0, 1], where 1 is the most advantageous rating among all considered items and 0 is the least advantageous.

The formula for the values that should be maximized in order to achieve the best rating is as follows:

where

- is the normalized rating of the i-th item;

- is the value of the parameter of the i-th item;

- is the lowest value of the parameter among all items;

- is the highest value of the parameter among all items.

The formula for the values that should be minimized in order to achieve the best rating is as follows:

where

- is the normalized rating of the i-th item;

- is the value of the parameter of the i-th item;

- is the lowest value of the parameter among all items;

- is the highest value of the parameter among all items.

4. Results

In order to assign weights to individual criteria, a five-person expert group compared the importance of these criteria in pairs (on a scale of 1–9) using the AHP method (Table 1). The correlation coefficient for this assessment was 9%. The expert group included four architects and urban planners who are scientists in the field of engineering and technical sciences with architectural and construction licenses to design without restrictions. One of them has experience working in the Municipal Urban Planning Studio. The fifth expert is a second-cycle student of the Faculty of Architecture in Poznan University of Technology. The presence of experts from only a single field of science constitutes a certain limitation. Our recommendation for future research would be to assemble experts from as wide a range of technical fields as possible, as well as from the natural and social sciences.

Table 1.

AHP pairwise comparison matrix and weights—expert assessment based on local conditions [source: own work].

In order to be able to compare the expert assessment, ChatGPT (version GPT-4o mini) artificial intelligence was used to assign weights to the nine selected criteria based on, first, the local laws of the city of Poznan (Table 2); second, Polish law regulations and norms (Table 3); and, third, EU Regulations (Table 4).

Table 2.

AHP pairwise comparison matrix and weights—assessment made by AI (ChatGPT) based on local law acts of Poznan district [source: own work].

Table 3.

AHP pairwise comparison matrix and weights—assessment made by AI (ChatGPT) based on Polish law regulations and norms [source: own work].

Table 4.

AHP pairwise comparison matrix and weights—assessment made by AI (ChatGPT) based on EU regulations [source: own work].

First, the following prompt was used: “make pairwise comparison matrix using AHP method, calculate correlation coefficient (must be <10%), calculate weights. Doing this, take into consideration the Local Law of the City of Poznan—BIP resolutions, regarding sustainable development and energy efficiency.”

Second, in order to be able to compare the expert assessment, ChatGPT artificial intelligence was also used to assign weights to the nine selected criteria based on Polish law. The following prompt was used: “make pairwise comparison matrix using AHP method, calculate correlation coefficient (<10%), calculate weights, based on local law, Polish Government regulations regarding sustainable development and energy efficiency.” The second assessment was made by artificial intelligence based on Polish law (KPEiK—Polish National Energy and Climate Plan 2021–2030; Krajowa Polityka Miejska 2030—National Urban Policy 2030; PEP2040—Energy policy of Poland until 2040; Prawo ochrony srodowiska—Environmental Protection Law; Act on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels; Strategy for Sustainable Development of Transport 2030; Act on Spatial Planning and Development; Strategi Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Energetycznego—Climate Policy of Poland).

Third, the following prompt was used: “make a pairwise comparison matrix using the AHP method, calculate correlation coefficient (must be <10%), calculate weights. Doing this, take into consideration EU regulations regarding sustainable development and energy efficiency.” An assessment was made by artificial intelligence based on the following Key EU Documents: European Green Deal (COM/2019/640); EU Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EU, amended 2023); EU Taxonomy Regulation (EU 2020/852); Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) (2023/2413); Fit for 55 package; Urban Agenda for the EU; New European Bauhaus; Smart Cities Marketplace; EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030.

- From these, we prioritize:

- Energy efficiency (K4) and renewable energy (K6) very highly;

- Public transport (K1), pollution reduction (K9), and compact design (K5) highly;

- Green space (K3), smart technology (K7), and community governance (K8) moderately highly;

- Mixed use (K2) moderately, based on urban planning goals.

For each assessment, a consistency check was performed to ensure the logical coherency of pairwise comparisons of the criteria following the standard procedure defined within the AHP methodology [69]. The consistency ratio is calculated according to the following formula:

where

- is the consistency ratio;

- is the consistency index;

- is the random index, defined as the average CI of randomly generated matrices.

In this formula, the consistency index is calculated as follows:

where

- is the maximum eigenvalue of the matrix;

- is the number of criteria.

The maximum eigenvalue of the matrix is defined by the following formula:

where

- is the consistency vector;

- is the weighted sum vector of the i-th criterion;

- is the priority vector (weight) of the i-th criterion.

The criteria weighting values according to all four assessments discussed are presented in the table below (Table 5).

Table 5.

AHP weights—comparison of four approaches [source: own work].

The presented rankings of the criteria according to four scenarios were validated by calculating Kendall’s W coefficient and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ). The Kendall’s W coefficient value of 0.43 indicates a moderate level of agreement between the assessments provided by the expert panel and the AI models analyzing regulations on three levels. A more detailed insight into the discrepancies between assessments is provided by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Table 6).

Table 6.

Spearman’s rank coefficients of correlation (ρ) between four approaches [source: own work].

The weights obtained for the criteria, from the expert assessment and three assessments made by artificial intelligence, were used to rank communes using the AHP method (Table 7). This shows how the assessment differs depending on the regulations adopted in the evaluation.

Table 7.

Final rankings of municipalities according to expert assessment and three assessments made by AI [source: own work].

The differences in weighted values between rural and urban–rural municipalities are minor across all assessment approaches, likely because both types often represent suburban areas with similar spatial structures and development issues, despite their formal administrative distinctions. The combined units that include fully urban municipalities, however, reveal noticeably lower scores, which may result from the limited availability of extensive areas for new suburban housing development and the more compact spatial structure of towns like Luboń and Puszczykowo.

5. Discussion

The research conducted aimed to verify whether provisions in local, national, and European legal regulations differ.

However, several limitations were encountered that may have influenced the research outcomes. These limitations were related to two main areas: data availability and the composition of the expert group. Regarding data availability, the scope and format of data publication varied significantly between municipalities. Moreover, the available datasets were limited in both temporal and territorial coverage. Not all municipalities possessed a complete set of records. Filling these gaps would have required supplementary data collection beyond the accessible datasets and the planned research framework. This would have exceeded the foreseen time constraints and significantly delayed the publication of results, potentially rendering them outdated. Therefore, it was decided to base the analysis on a dataset restricted to available information. The second limitation, concerning the composition of the expert group, was that its members had knowledge and experience mainly in the fields of urban planning and architecture. Future research is expected to expand this group to include experts from other relevant fields.

Kendall’s W coefficient and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient are calculated in Section 4. The results indicate that there are significant discrepancies between the factors regarding energy efficiency and sustainable development, taking into consideration regulations on local, national, and supranational levels. While the EU and Polish legal systems are more or less coherent, the local regulations do not correspond with them, as the negative value of the correlation coefficient shows.

This result confirms the belief that local law should be adapted to the local conditions of the commune. A prime example is the urbanization of mountainous areas, which differs significantly from the urbanization processes in the plains. For example, the mountainous landscape contributes to depopulation (and the aging of communities) in these areas [48]. However, the suburban municipalities studied require a different approach, partly because they face different challenges, including demographic, landscape, economic, and other issues. They are experiencing mass migration from cities (urban sprawl). They are also experiencing a shift from agricultural to residential and service character (declining agricultural employment), as in rural areas, but on a much larger scale [70,71].

From the ranking of weights in expert assessment based on local conditions and assessment made by AI (ChatGPT) based on Polish law regulations and norms, EU regulations result in a situation in which the most important criterion influencing sustainable development of the commune is Renewable Energy Integration. The situation is different in the case of AI assessment based on the local law acts of the Poznan district. The low position of the Renewable Energy Integration criterion in the assessment made by AI based on the local law acts of the Poznan district reflects the actual state of affairs in the provisions of local law. Limited reference to renewable energy sources in the General Plans of municipalities can be observed (they are referenced only in one of the zones—the open zone—with wind and solar power plants as a basic/supplementary profile) [72]. There are no or few regulations regarding renewable energy sources in most local spatial development plans for residential and commercial areas.

Another observation after analyzing the results is that the mixed-use development criterion is generally considered a low priority under EU, Polish, and local law. However, according to expert assessments, this matter should be given more focus. This issue is addressed in contemporary urban planning ideas (15 min city, new urbanism, etc.), but it is not included in the spatial planning legislation, which is still based on zoning. Urban density and compact design are also insufficiently considered in local law [73,74].

Biodiversity appears to be a relatively important issue in local law. Indeed, there are many restrictions on investments and their processing resulting from the protection of valuable natural sites and species (Natura 2000, environmental decisions, etc.). Such provisions can be interpreted as an opportunity to protect areas of natural value; at the same time, restrictive procedures for obtaining building permits may block or delay certain investments that may improve transport or energy efficiency, for example.

The comparison of criteria weights indicates that bottom-up initiatives, crucial in shaping fourth-generation cities that respond to user needs, are not included in the EU Regulations or Polish law, and experts regard these a significant element in shaping the sustainable development of municipalities or energy efficiency. However, its importance was recognized in local law.

The ranking of spatial units presented in this study serves an illustrative purpose and demonstrates how the adopted method determines the final results. The weights and hierarchy of criteria, as well as the observed differences between the global and local approaches, are strictly dependent on the local context and therefore cannot be directly generalized. Applying the proposed framework in different locations may lead to different results, which is why the entire evaluation procedure should be carried out individually for each given area, taking into account its specific characteristics.

The methods, research, and conclusions drawn from the results used in this article can be used by municipal authorities to make decisions about spatial development or which areas require improvement. What are the municipalities’ needs regarding spatial planning and sustainable development? Where should specific functions and investments be located?

Therefore, the conclusions from the conducted research emphasize the need for greater territorial differentiation and adaptation of planning regulations to local realities—at both the national and EU levels. Legal frameworks and spatial policies should consider local and regional specificities, including climatic conditions, physiographic features, socioeconomic structure, demographic trends, cultural landscape, and the availability of natural and infrastructural resources. Recognizing and integrating these factors would enable more informed, flexible, and sustainable planning decisions—particularly in dynamically changing suburban municipalities, facing challenges such as migration (i.e., to the peri-urban zone from city centers), land-use transformation, infrastructure shortages, and environmental pressures. In this context, the presented study provides not only an analytical basis for assessing current planning practices but also strategic guidance for shaping more resilient and locally adapted spatial development policies.

The research will be continued and extended in several directions. The primary goal is to address current limitations by involving experts from diverse fields related to sustainable development, such as environmental engineering, energy, social studies, spatial management, environmental protection, hydrology, and others, with the aim of comparing and validating results across disciplines. Further research directions include studies of the accessibility of services in relation to the planning of newly developed residential areas, using isochrone-based analyses, considering environmental impact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.B.; methodology, W.B., A.K.-A., I.P.-C., W.S. and K.B.; software, W.S., A.K.-A. and I.P.-C.; validation, W.B., A.K.-A., I.P.-C., W.S. and K.B.; formal analysis, A.K.-A., I.P.-C. and W.S.; investigation, A.K.-A., I.P.-C. and W.S.; resources, W.B., A.K.-A., I.P.-C., W.S. and K.B.; data curation, W.B., A.K.-A., I.P.-C., W.S. and K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.-A., I.P.-C. and W.S.; writing—review and editing, W.B.; visualization, W.S.; supervision, W.B.; project administration, W.B., A.K.-A., I.P.-C. and W.S.; funding acquisition, W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Poznan University of Technology, grant number ERP 0111/SBAD/2404.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used ChatGPT (version GPT-4o mini) for research purposes, particularly to prepare selected pairwise comparison matrices (three out of four) using the AHP method, including the assignment of weights, as described in Section 4 (Results). Additionally, Scopus AI (Release: November 2024) was used to compile a database of keywords, as presented in Section 3.2 (Research Methods). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Komarova, A.V.; Filimonova, I.V.; Kartashevich, A.A. Energy consumption of the countries in the context of economic development and energy transition. Energy Rep. 2022, 8 (Suppl. S9), 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lityński, P. The intensity of urban sprawl in Poland. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinska-Andruszkiewicz, A. Brak przestrzeni społecznych i kontynuacji założeń urbanistycznych wsi Skórzewo jako wynik suburbanizacji Poznania (Lack of Social Spaces and Continuity of Urban Planning Principles in the Village of Skórzewo as a Result of Suburbanisation of Poznań). Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Poznańskiej. Archit. Urban. Archit. Wnętrz 2023, 15, 477–498. [Google Scholar]

- Lityński, P.; Hołuj, A.; Zotic, V. Polish urban sprawl: An economic perspective. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2015, 6, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Aparicio, S.; Grythe, H.; Drabicki, A.; Chwastek, K.; Toboła, K.; Górska-Niemas, L.; Kierpiec, U.; Markelj, M.; Strużewska, J.; Kud, B.; et al. Environmental sustainability of urban expansion: Implications for transport emissions, air pollution, and city growth. Environ. Int. 2025, 196, 109310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiack, D.; Cumberbatch, J.; Sutherland, M.; Zerphey, N. Sustainable adaptation: Social equity and local climate adaptation planning in U.S. cities. Cities 2021, 114, 103235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boria, E.; Rozhkov, A.; Seyrfar, A. Identifying the need for an energy urban planning role. Energy Proc. 2020, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Yamagata, Y. Sustainable urban development: Balancing decarbonisation and well-being using GIS scenario analysis. Energy Proc. 2025, 54, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C. The 15-Minute City: A Solution for Saving Our Time and Our Planet; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Szymańska, D.; Szafrańska, E.; Korolko, M. The 15-Minute City: Assumptions, Opportunities and Limitations, Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series; Nicolaus Copernicus University: Toruń, Poland, 2024; pp. 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverts, T. From the Impossible Organization to a Possible Disorganization in Designing of the City Landscape: A Personal View on the Global Development of City Landscapes and Their Chances of Development; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2007; pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverts, T. Zwischenstadt (In-Between City) (1997), the Horizontal Metropolis: The Anthology; Springer International Publishing: Darmstadt, Germany, 2022; pp. 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverts, T.; Koch, M.; Stein, U.; Steinbusch, M. Zwischenstadt—Inzwischen Stadt? Entdecken, Begreifen, Verändern (Zwischenstadt—Already a City? Discovering, Understanding, Transforming); Müller und Busmann: Wuppertal, Germany, 2005; ISBN 3-928766-72-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bölling, L.; Sieverts, T. Mitten am Rand. Auf dem Weg von der Vorstadt Über die Zwischenstadt zur Regionalen Stadtlandschaft (At the Edge Yet in the Middle. On the Path from Suburb to Zwischenstadt to Regional Urban Landscape); Müller und Busmann: Wuppertal, Germany, 2004; ISBN 3-928766-59-7. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, R. Zwischenstadt|Inbetween City. Thomas Sieverts, Cities Without Cities: An Interpretation of the Zwischenstadt, 2004, Urban Book Series Book Chapter; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicenzotti, V.; Qviström, M. Zwischenstadt as a Travelling Concept: Towards a Critical Discussion of Mobile Ideas in Transnational Planning Discourses on Urban Sprawl, European Planning Studies; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krier, L. The Architecture of Community; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Samalavičius, A. Modernity and its discontents: A conversation with architect and urban planner Leon Krier. J. Archit. Urban. 2013, 37, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F.; Moreno, C. On Proximity-Based Dimensions and Urban Planning: Historical Precepts to the 15-Minute City, Resilient and Sustainable Cities, Research, Policy and Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson-Fawcett, M. Leon Krier and the organic revival within urban policy and practice. Plan. Perspect. 1998, 13, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantey, D. New Urbanism in Assessing Sustainability of Polish and American Suburbs; The University of Warsaw Press: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; pp. 206–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreau, J. Edge City: Life on the New Frontier; Anchor Books a Division of Random House Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Komninos, N. Intelligent Cities and Globalisation of Innovation Networks, London and New York; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bonenberg, W.; Skórzewski, W.; Qi, L.; Han, Y.; Czekała, W.; Zhou, M. An Energy-Saving-Oriented Approach to Urban Design—Application in the Local Conditions of Poznań Metropolitan Area (Poland). Sustainability 2023, 15, 10994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonenberg, W.; Kapliński, O. Knowledge is the key to innovation in architectural design. Procedia Eng. 2017, 196, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitha, J.S.; Tejaswini, D.N.; Charhate, S. Embodied energy—A measure of sustainability of buildings. Indian Concr. J. 2018, 92, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, S.; Abdullah, J.; Nawawi, A.H. The financial costs of urban sprawl: Case study of Penang State. Plan. Malays. 2017, 16, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hoelscher, M.-T.; Nehls, T.; Jänicke, B.; Wessolek, G. Quantifying cooling effects of facade greening: Shading, transpiration and insulation. Energy Build. 2016, 114, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, W. Gestaltungsgrundlagen Passivhäuser; Beispiel (Design Principles of Passive Houses, Example): Darmstadt, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baez-Garcia, W.G.; Simá, E.; Chagolla-Aranda, M.A.; Carreto-Hernandez, L.G.; Aguilar, J.O. Experimental evaluation of the thermal behavior of a green facade in the cold and warm seasons in a subtropical climate (Cwa) of México. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 84, 111627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, X.C. Effects of jobs-residence balance on commuting patterns: Differences in employment sectors and urban forms. Transp. Res. Rec. 2015, 2500, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Hipp, J.R. Do employment centers matter? Consequences for commuting distance in the Los Angeles region, 2002–2019. Cities 2024, 139, 10466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, F.; Zakaria, R.; Bigah, Y.; Mustafar, M.; Puan, O.C.; Zin, I.S.; Klufallah, M.M.A. Conceptualising the indicators of walkability for sustainable transportation. J. Teknol. (Sci. Eng.) 2013, 65, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hideg, V.; Makó, E. Introducing the Walkability Index, an Index That Measures the Walkability of Public Spaces. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 107, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Huang, Y.; Sun, T. Urban sprawl, public transportation efficiency and carbon emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 489, 144652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchen, T.; Typaldos, P.; Malikopoulos, A.A. A United Framework for Planning Electric Vehicle Charging Accessibility. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.05827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jin, S.; Xiao, B. An estimation of the available spatial intensity of solar energy in urban blocks in Wuhan, China. Energies 2024, 17, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachan, Y.; Shram, O. To the issue of the appropriate scheme for connecting renewable energy sources to industrial power grids. Vidnovluvana Energ. 2023, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Talebi, A.; Agabalaye-Rahvar, M.; Zare, K.; Gozel, T. Economic-Environmental Analysis of Smart Power System in the Presence of Dynamic Line Rating and Energy Storage System. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Technology and Energy Management (ICTEM 2024), Behshar, Iran, 14–15 February 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger-Lacan, C. Urban Planning and Energy: New Relationships, New Local Governance. In Local Energy Autonomy: Spaces, Scales, Politics; Labussière, O., Nadaï, A., Eds.; Wiley-ISTE: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanusi, R.; Jalil, M. Blue-Green Infrastructure Determines the Microclimate Mitigation Potential Targeted for Urban Cooling. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 918, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.; Zou, D. The Impact of Architectural Layout on Urban Heat Island Effect: A Thermodynamic Perspective. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2024, 42, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Zhang, T.; Qin, Y.; Tan, Y.; Liu, J. A Comparative Review on the Mitigation Strategies of Urban Heat Island (UHI): A Pathway for Sustainable Urban Development. Clim. Dev. 2023, 15, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrelet, K.; Moretti, M.; Dietzel, A.; Altermatt, F.; Cook, L.M. Engineering Blue-Green Infrastructure for and with Biodiversity in Cities. npj Urban. Sustain. 2024, 4, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfasi, N.; Margalit, T. Toward the Sustainable Metropolis: The Challenge of Planning Regulation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Allred, D. Connecting Regional Governance, Urban Form, and Energy Use: Opportunities and Limitations. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2015, 2, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frare, M.B.; Clauberg, A.P.; Sehnem, S.; Campos, L.M.; Spuldaro, J. Toward a sustainable development indicators system for small. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1148–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Penabad, M.C.; Iglesias-Casal, A.; Rey-Ares, L. Proposal for a sustainable development index for rural municipalities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, J.A.; Benedek, J.; Ivan, K. Measuring Sustainable Development Goals at a Local. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M.; Jato-Espino, D. Resilient, Sustainable, Safe and Inclusive Community Rating System (RESSICOM). J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyka, A.; Jopek, D.; Skrzypczak, I. Analysis of the Sustainable Development Index in the communes of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship: A Polish case study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the City and Municipality of Buk. Resolution No. XII/96/2019 of 29 October 2019 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the City and Municipality of Buk. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Czerwonak Municipality. Resolution No. 778/LXXII/2023 of 23 November 2023 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Czerwonak Municipality. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Dopiewo Municipality. Resolution No. XVI/226/16 of 29 February 2016 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Dopiewo Municipality. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the City and Municipality of Kórnik. Resolution No. XXXII/442/2021 of 26 May 2021 on the amendment of the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Kórnik Municipality (Amendment no. 33, Błażejewko Precinct). 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Kleszczewo Municipality. Resolution No. XXXII/186/01 of 26 September 2001 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Kleszczewo Municipality. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Komorniki Municipality. Resolution No. LII/348/2010 of 25 October 2010 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Komorniki Municipality (amendments: Resolution No. XXXV/355/2017 of 25 May 2017, Resolution No. XXVIII/242/2020 of 24 September 2020). 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Kostrzyn Municipality. Resolution No. XXIV/208/2020 of 10 September 2020 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Kostrzyn Municipality. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the City of Luboń. Resolution No. XXXII/234/2017 of 8 May 2017 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the City of Luboń. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Mosina Municipality. Resolution No. LVI/386/10 of 25 February 2010 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Mosina Municipality. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Murowana Goślina Municipality. Resolution No. XXXIII/336/2021 of 15 June 2021 on the amendment of the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Murowana Goślina Municipality. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Pobiedziska Municipality. Resolution No. V/40/2011 of 24 February 2011 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Pobiedziska Municipality. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Rokietnica Municipality. Resolution No. XI/72/2011 of 27 June 2011 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Rokietnica Municipality (Amendments: Resolution No. V/32/2019 of 28 January 2019, Resolution No. XVIII/156/2019 of 16 December 2019, Resolution No. LV/455/2022 of 20 June 2022). 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the City of Puszczykowo. Resolution No. 279/18/VII of 30 January 2018 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the City of Puszczykowo. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Suchy Las Municipality. Resolution No. XXXVIII/424/21 of 28 October 2021 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Suchy Las Municipality. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Swarzędz Municipality. Resolution No. X/51/2011 of 29 March 2011 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Swarzędz Municipality; amended by Resolution No. XXXV/402/2021 of 23 March 2021. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Tarnowo Podgórne Municipality. Resolution No. L/852/2022 of 29 March 2022 on the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Tarnowo Podgórne Municipality. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the Stęszew Municipality. Resolution No. XXIV/177/2020 of 22 July 2020 on the adoption of the Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of the Stęszew Municipality. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, J.; Martyniuk-Pęczek, J. Looking for the Optimal Location of an Eco-District within a Metropolitan Area: The Case of Tricity Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulicka, A. Miasto zielone—Miasto zrównoważone. Sposoby kształtowania miejskich terenów zieleni w nawiązaniu do idei Green City (Green City—Sustainable City. Methods of Shaping Urban Green Spaces in Reference to the Green City Concept). Pr. Geogr. 2015, 141, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzykowski, B.; Rembarz, G.; Cenian, A. Revitalisation Living Lab as a Format to Accelerate an Energy Transition in Polish Rural Areas: The Case Studies of Metropolitan Outskirts Gdańsk-Orunia and Lubań//Energy Transition in the Baltic Sea Region Understanding Stakeholder Engagement and Community Acceptance; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2022; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jenks, M.; Colin, J. Dimensions of the Sustainable City; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W. Intelligent cities, e-Journal on the Knowledge Society. UOC Pap. 2007, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).