Abstract

This study evaluated a sustainable strategy for Para grass (Brachiaria mutica) forage using composted cow manure in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. At Nam Can Tho Experimental Farm (January–September 2023), a completely randomized design with three replications and three harvest cycles tested five topdressing rates: 0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10 t/ha/year (TDM0–TDM10). Tiller emergence, plant height, forage quality, biomass yield, and cost–benefit were measured. Tiller counts were unaffected (p > 0.05), but plant height rose significantly with manure rate. Forage quality remained optimal (CP 7.10–7.85%, NDF 60.5–63.8%). Average fresh biomass yield (FBM, t/ha) increased linearly: y = 0.788x + 14.9 (R2 = 0.937), where x is manure rate (t/ha/year). TDM10 yielded 50% more fresh forage (22.6 t/ha) and 48% more dry matter (4.43 t/ha) than the control (15.0 and 2.98 t/ha; p = 0.001), with crude protein up 56% (0.347 t/ha) and neutral detergent fiber up 41% (2.68 t/ha). Total cost increased slightly (from 521 to 552 USD/ha), but per-ton cost dropped 30% (from 34.7 to 24.4 USD). At 10 t/ha/year, manure optimized yield, profitability, circular nutrient use, and reduced fertilizer dependence, providing a scalable model for tropical smallholder livestock feed.

1. Introduction

The global and Vietnamese shifts toward organic agricultural production have increasingly encouraged the use of manure as a practical and sustainable fertilizer for crops and pastures. Utilizing composted cow manure not only supports the cultivation of organic forage but also reduces environmental pollution and enhances economic returns [1,2,3]. In recent years, many provinces in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam have implemented crop and livestock restructuring policies aligned with national development strategies. By 2023, the region housed approximately 866,300 cattle and 443,856 goats [4]. As the populations of cattle, buffaloes, and goats continue to grow rapidly to meet rising demand for meat and dairy products, they generate substantial volumes of waste, intensifying the urgent need for sustainable forage production [5]. Because these ruminants compete minimally with humans for feed resources, cultivating grasses fertilized with livestock manure offers a vital strategy for meeting the nutritional needs of grass-fed animals and supporting organic crop systems [6,7,8]. Furthermore, systematic reviews on manure application in forage production have also shown that it plays an important role in protecting soil biodiversity, promoting sustainable forage production, optimizing nutrient use, and reducing pollution, thereby improving plant growth, yield, and profitability [9,10,11].

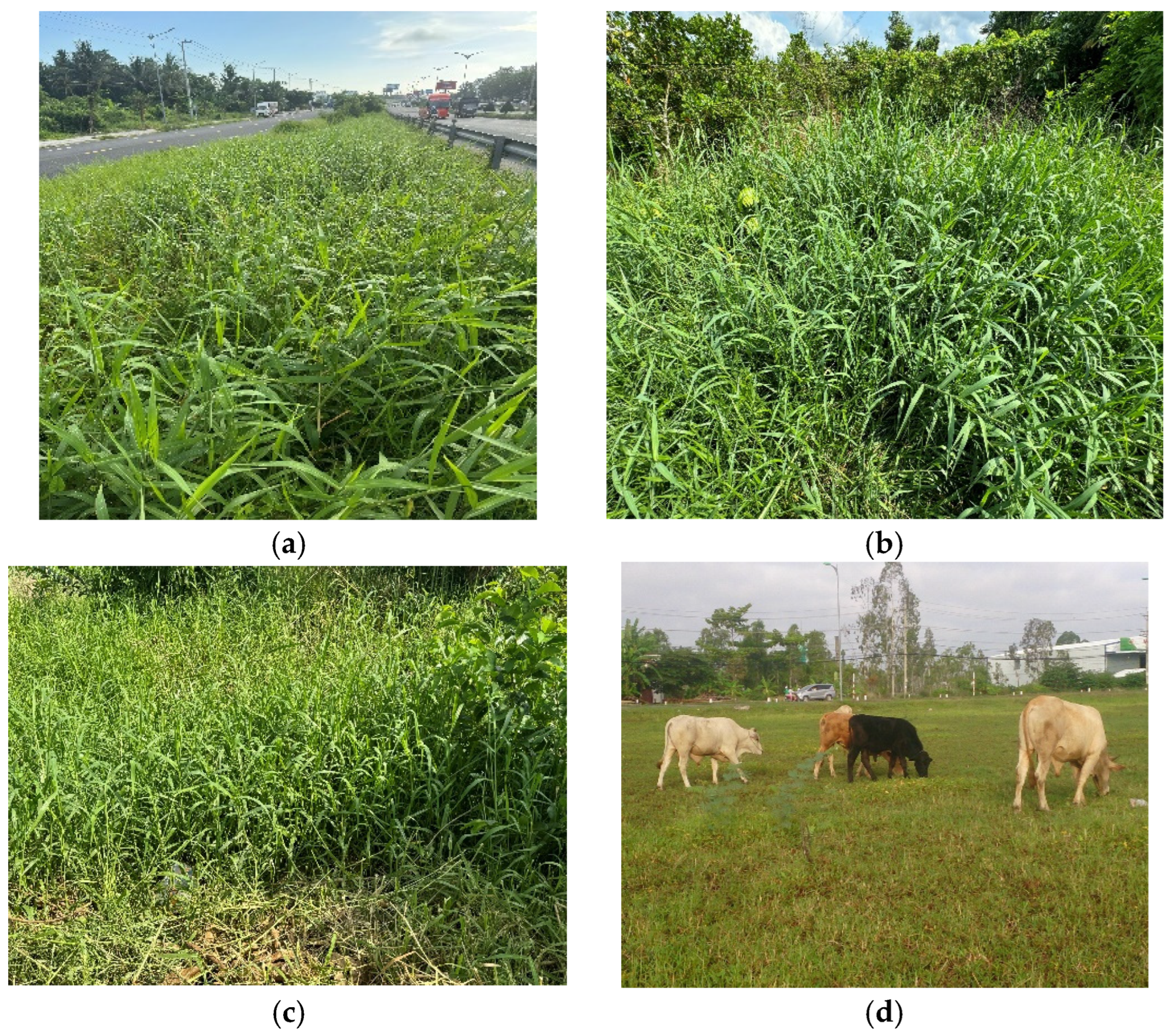

Brachiaria mutica, commonly known as Para grass, originates from South America and has been widely cultivated worldwide as forage for ruminants and horses. In Vietnam, it has been grown primarily in southern regions since the late 19th century and has since spread nationwide [12]. Para grass thrives in hot, humid climates and tolerates short-term flooding, salinity, and acidic soils [13,14]. In the Mekong Delta, it is particularly prevalent in lowland areas subject to seasonal flooding, where flood-tolerant grasses are essential for maintaining productive grasslands [15]. Despite being extensively used as a major forage source—either through free grazing or cut-and-carry systems—Para grass often grows naturally along dikes, roadsides, field margins, and homesteads without intentional planting or management (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Para grass in natural habitats and its utilization as livestock feed—(a) Para grass along the roads; (b) Para grass in fruit tree garden; (c) wild Para grass cut for feeding; and (d) cattle grazing Para grass.

Field observations revealed promising productivity, with five cuttings per year yielding approximately 55.2 tons of fresh biomass, 13.8 tons of dry matter, and 1.17 tons of crude protein per hectare annually [16]. Similarly, Wekgari et al. (2023) [17] reported that Para grass produces higher dry matter and protein yields compared to other Brachiaria varieties in Oromia, Ethiopia. Ruminants generally prefer Para grass over other commonly planted species such as Setaria, Paspalum, and elephant grass, likely due to its palatability, small stem size, high dry matter content, moderate crude protein levels, digestible fiber, and mineral profile [13]. Although well-adapted to local conditions and valued for its rapid regrowth and nutritional quality, detailed data on the growth characteristics and yield potential of Para grass under diverse management regimes remain scarce in Vietnam.

Para grasslands are widely used by ruminant farmers as primary forage sources in both grazing and cut-and-carry systems, effectively serving as natural resources for livestock husbandry with minimal inputs aimed at improving productivity or nutritive quality. In scientific research, Para grass is frequently employed as a primary roughage source or control species in livestock feeding studies, including in vitro and in vivo digestion trials [18]. Despite its extensive use and ecological importance, research focusing on its biological traits, growth dynamics, productivity, and especially economic efficiency remains limited. Economic analyses are a critical but often overlooked aspect of forage production research, particularly in developing countries like Vietnam, where practical applicability for producers and alignment with scientific and technological advances are essential.

Addressing both scientific and practical needs, this study aims to evaluate the effects of varying composted cow manure application rates on the growth, yield, and quality of Para grass. The findings are intended to provide evidence-based recommendations to optimize forage production, contribute to sustainable livestock farming, and help meet the increasing demand for green, organic forage in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Soil Characteristics

The experiment was conducted at the Nam Can Tho Experimental Farm (My Phuoc Hamlet, My Khanh Commune, Phong Dien District, Can Tho City, Vietnam) from January to September 2023. Soil preparation and planting during the dry season, combined with regular watering, were favorable for grass development. The site features a tropical monsoon climate with an average annual temperature of 27 °C and rainfall of 1500–2000 mm.

Soil samples (0–30 cm depth) were collected from five random points per plot, air-dried, sieved (<2 mm), and analyzed for physicochemical properties using standard protocols. pH was measured in 1:2.5 soil:water suspension using a glass electrode pH meter (HI 8424, Hanna Instruments, Nusfalau, Romania). Organic matter (OM) was determined by loss-on-ignition at 550 °C for 4 h. Ammonium-N (NH4+-N) and nitrate-N (NO3−-N) were extracted with 2 M KCl and quantified colorimetrically by indophenol blue and cadmium reduction methods, respectively (spectrophotometer UV-1800, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Available P was extracted with Bray-1 solution (0.03 M NH4F + 0.025 M HCl) and measured by the molybdenum blue method (spectrophotometer). Exchangeable K, Ca, and Mg were extracted with 1 M NH4OAc (pH 7.0) and determined by flame atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS, Analyst 200, PerkinElmer, Sheton, CT, USA). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was measured by the ammonium acetate saturation method at pH 7.0. Selected properties are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Some physicochemical properties of the soil used for grass cultivation.

The properties of the soil were characterized as follows: The soil pH was slightly acidic, which renders it suitable for the cultivation of most tropical forage grasses. Regarding organic matter, the soil exhibited a content of 4.03%, indicating a moderate level that is significant for nutrient cycling, moisture retention, and the maintenance of soil structure. In terms of nitrogen content (NH4+-N and NO3−-N), the ammonium concentration (6.29 mg/kg) fell within a typical range for tropical soils, whereas the nitrate concentration (0.172 mg/kg) was low, likely reflecting rapid nitrogen cycling and potential leaching associated with humid climatic conditions. With respect to available phosphorus, a concentration of 10.5 mg/kg was deemed adequate for forage production. Concerning exchangeable cations (K, Ca, Mg), the values suggested a moderate-to-high fertility status. Specifically, calcium and magnesium levels were relatively high, thereby supporting robust soil structure and nutrient supply. Potassium levels, although moderate, remained within typical ranges for soils supporting tropical forage grasses. Finally, the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of 17.6 cmol(+)/kg indicated a moderate capacity for cation retention, which contributes to nutrient availability and provides buffering against soil acidification.

2.2. Plant Material

Para grass, locally known as “co Long Tay”, was propagated using stem cuttings (20–25 cm long with 2–3 nodes) collected from healthy, sprouted plants (3–4 cm shoots) around the experimental farm. Cuttings were selected for uniformity and disease-free status.

2.3. Experimental Design and Treatments

A completely randomized design was employed with five treatments and three replications (total area 153 m2). Each plot measured 10.2 m2 (1.2 m × 8.5 m). Grass was planted in rows spaced 30 cm apart, with 40 cm between plants. Treatments consisted of topdressing rates of composted cow manure (t/ha/year): TDM0 (no fertilizer; 0), TDM2.5 (2.5), TDM5.0 (5.0), TDM7.5 (7.5), and TDM10 (10.0). Cow manure, used as fertilizer, was well-composted to destroy weeds, pests, and pathogens, promote organic breakdown, and speed up mineralization. Fresh manure was avoided to prevent pathogen transfer to plant roots.

2.4. Planting and Crop Management

Raised beds were constructed with 60 cm wide and 30 cm deep furrows between them. All plots received basal applications of composted cow manure, prepared by fermenting dung from F1 Charolais × Sind crossbred cattle with water hyacinth and straw in a 2:5:1 ratio for one month [19]. The chemical composition (%) of cow manure included moisture: 71.7, organic matter (OM): 37.3, total nitrogen (N): 1.56, phosphorus: 1.52, potassium oxide (K2O): 1.01, calcium: 0.72, and magnesium (Mg): 0.4. Basal application rates (for 153 m2 total) were manure: 306 kg (≈15.7 t/ha); phosphorus (P): 4.59 kg (≈235 kg/ha); and potassium (K): 3.06 kg (≈157 kg/ha), following the state of Quang and Trach (2003) [20]. For three litters, the topdressing was applied 21 days after planting; for subsequent regrowth cycles, it occurred two days post harvest. Topdressing rates per plot per cycle were as follows: TDM0: none; TDM2.5: 0.263 kg; TDM5.0: 0.525 kg; TDM7.5: 0.788 kg; and TDM10: 1.05 kg.

Grass was propagated using 20–25 cm stem cuttings with 2–3 nodes, selecting healthy, sprouted cuttings (3–4 cm shoots). Cuttings were planted in a grid at 30 × 40 cm spacing, with three cuttings per clump, with the first node buried about 2 cm deep and watered upon planting (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Planting preparation: (a) topdressing fertilization; (b) stem cuttings; and (c) planting.

The care and maintenance procedures for the study were systematically implemented as follows. Irrigation was conducted once daily between 3:00 and 4:00 PM on dry or sunny days to ensure adequate soil moisture. Weeding was performed as needed, with comprehensive weeding undertaken after each harvest to maintain optimal growing conditions. Additionally, pest monitoring involved regular inspections for pests and diseases to facilitate early detection and effective management.

2.5. Measurements

Measurements were taken between 8:00 and 9:00 AM on dry mornings. Tiller number (new basal shoots per clump) was counted visually in five 1 m2 quadrats per plot sampled diagonally at 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, 56, and 63 days after planting for the first cycle, and 7–35 days for regrowth. Plant height was measured from the soil surface to the tallest point of straightened leaf using a 5 m measuring tape (±1 mm accuracy; G-Star G-576E, New York, NY, USA) on 10 random plants per quadrat. Measurements were taken at five ~1 m2 points per plot using diagonal square sampling [21]. Figure 3 presents how the tillers of Para grass are counted.

Figure 3.

Counting tillers of Para grass.

Fresh biomass yield and chemical compositions: The first harvest (cut 1) was taken 63 days after planting, and the second and third harvest (cut 2 and 3) after 35 days, in order to evaluate fresh biomass, dry matter and protein yield, and the chemical composition of the grass. Harvesting time was between 8 and 9 am on dry, sunny mornings to avoid moisture bias. The grass was cut uniformly at 4–5 cm above ground, and fresh biomass was weighed on a mechanical scale. Sample collection was performed as follows: from each plot, 5 samples (1 kg fresh) were collected at random following a diagonal square pattern. Dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), and neutral detergent fiber (NDF) yield were calculated following their nutrient contents analyzed. Samples were oven-dried at 65 °C and were analyzed for dry matter (DM), organic matter (OM), crude protein (CP), ether extract (EE) by AOAC [22], and neutral detergent fiber (NDF) by Van Soest et al. [23]. Analyses were performed in Laboratory E205, Faculty of Animal Sciences, College of Agriculture, Can Tho University.

Cost production: The production cost of fresh Para grass yield (USD/ton) was calculated and analyzed based on current prices, taking into account expenses for land rent, stem cuttings for planting, organic cow manure fertilizer, pesticides, fuel for irrigation, and labor. This analysis aimed to evaluate the economic value of Para grass under different fertilization treatments (TDM0, TDM2.5, TDM5.0, TDM7.5, and TDM10).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Collected data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2016 and statistically analyzed using the General Linear Model (GLM) in Minitab 16.2.1. Treatment differences and pairwise comparisons were determined using Tukey’s test at appropriate significance levels [24].

3. Results

3.1. Tiller Density per Clump

Tiller counts per clump were recorded weekly across three harvests (up to 63 days in harvest 1 and 35 days in harvests 2 and 3). Values ranged from 3.40 to 3.70 at day 7 in harvest 1, increasing to 28.1–32.5 by day 63, with similar patterns in subsequent harvests (e.g., 28.5–33.8 at day 7 in harvest 2, stabilizing at 48.7–50.9 by day 35 in harvest 3). No significant differences among treatments were observed at any measurement point (p > 0.05). Detailed tiller counts at each interval are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of tiller per clump at different ages (day) of litters under different treatments.

3.2. Plant Height Development

Plant height (cm) was measured weekly across three harvests. In harvest 1, heights ranged from 21.0 to 21.9 cm at day 7, increasing to 124–139 cm by day 63, with significant differences emerging from day 28 (p < 0.05; TDM10 highest at 139 cm). In harvests 2 and 3, initial heights were 31.0–36.0 cm at day 7, reaching 90.9–113 cm by day 35, with significant differences observed as early as day 7 (p < 0.05). Plant height measurements at each interval are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Plant height (cm) at different ages of 3 litters under different treatments.

3.3. Chemical Composition

The chemical composition (%) of Para grass was determined for each harvest and averaged across all three. Dry matter (DM) ranged from 17.5 to 21.8% in individual harvests, averaging 18.8–19.8%; crude protein (CP) from 6.52 to 8.34%, averaging 7.10–7.85%; neutral detergent fiber (NDF) from 59.7 to 65.8%, averaging 60.5–63.8%; and other components showed minor variations (e.g., organic matter 88.4–92.7%). No significant differences among treatments were observed for any component in any harvest (p > 0.05). Compositional data across harvests and treatments are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Chemical composition (%) of Para grass under different treatments over 3 harvests.

3.4. Biomass and Nutrient Yields

Yields (t/ha per cutting) of fresh biomass (FBM), dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), and neutral detergent fiber (NDF) were calculated for each harvest and averaged. In harvest 1, FBM ranged from 13.4 to 22.0 t/ha, DM from 2.47 to 3.90 t/ha, CP from 0.167 to 0.310 t/ha, and NDF from 1.60 to 2.40 t/ha, with similar increases in harvests 2 and 3 (e.g., average FBM 15.0–22.6 t/ha across all). Significant increases with higher manure rates were observed for all yield components (p < 0.05)(Table 5).

Table 5.

Yield (t/ha/cutting) of fresh biomass, dry matter, crude protein, and neutral detergent fiber in different treatments.

3.5. The Production Costs of Para Grass

Production costs were itemized (USD/ha) and normalized per ton of fresh yield over three harvests, highlighting the impact of manure rates on total and unit economics. Total costs ranged from 521 USD/ha (TDM0) to 552 USD/ha (TDM10), driven primarily by topdressing manure (0–31.35 USD/ha), with fresh yield from 15.0 to 22.6 t/ha, resulting in costs per ton from 34.7 USD (TDM0) to 24.4 USD (TDM10) and relative costs of 70.3–100% of TDM0. Cost breakdowns and per-ton calculations are detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

The average cost to produce Para grass (USD/ha) and production cost (USD/ton) over 3 harvest cycles.

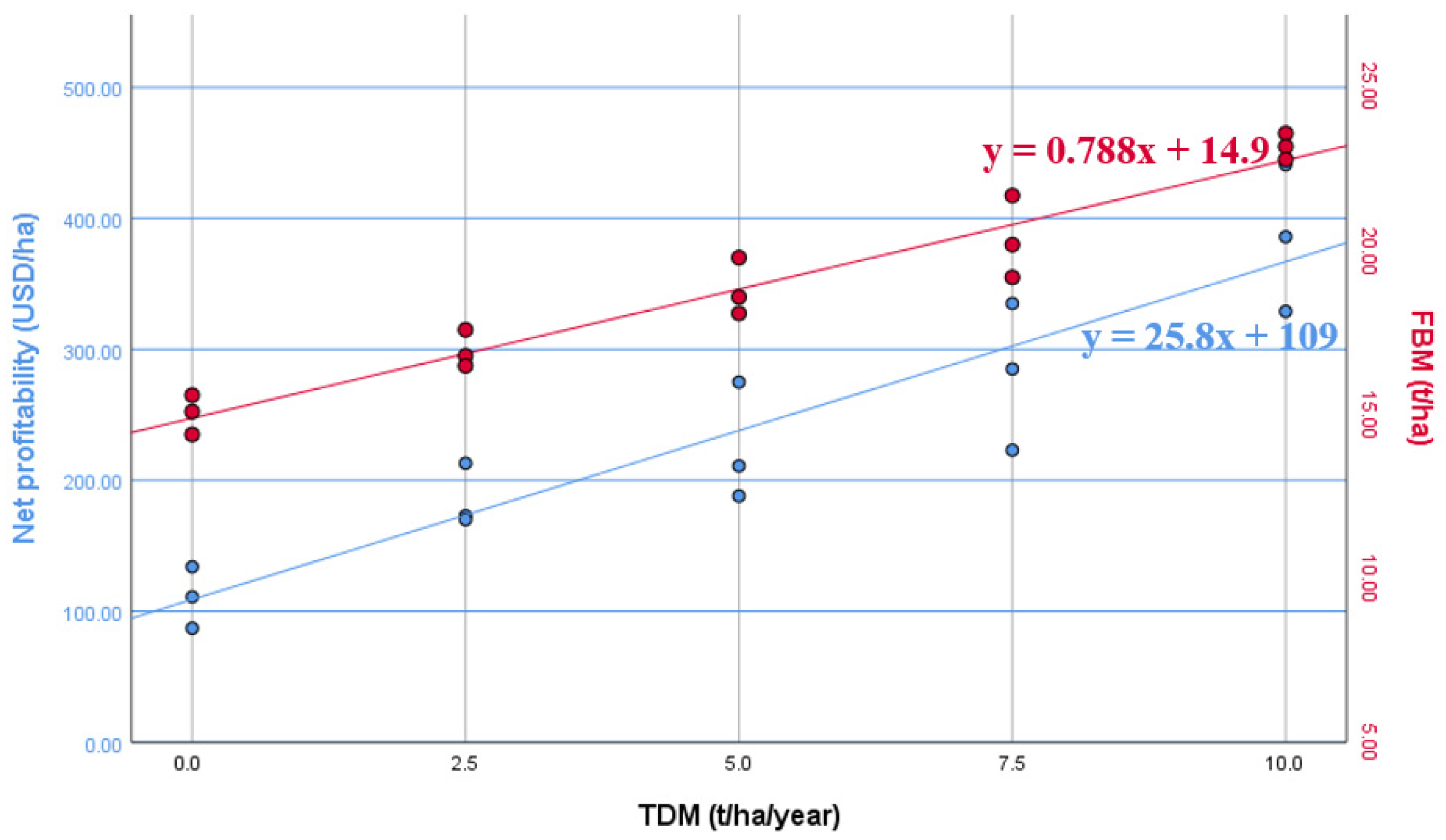

A linear regression analysis revealed positive relationships between manure application rates and both agronomic and economic outcomes in Para grass cultivation. Specifically, average fresh biomass yield (FBM, t/ha) increased with manure rate according to y = 0.788x + 14.9 (R2 = 0.937), where x is the manure rate (t/ha/year). Additionally, net profitability (USD/ha) followed y = 25.8x + 109 (R2 = 0.848), indicating that each additional ton of manure boosts profit by about USD 25.80 beyond a baseline of USD 109/ha without application. The high R2 for profitability underscores a strong linear association, driven by enhanced yields outweighing modest input costs. Both regressions are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Effects of manure application rates on fresh biomass yield and profit in Para grass. Note: TDM0, TDM2.5, TDM5.0, TDM7.5, and TDM10 denote manure application rates of 0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10 t/ha/year; FBM: fresh biomass (t/ha); Net profitability (USD/ha).

4. Discussion

4.1. Promotive Effects and Mechanisms of Composted Cow Manure on Para Grass Growth and Yield

4.1.1. Tiller Density per Clump

There were no significant differences among treatments in tiller number at any age during three litters (p > 0.05). For example, in litter 1, at 7 days, tiller counts were 3.40–3.70 across treatments, and at harvest (63 days), counts were 28.1–32.5. Similar consistency was observed in litter 2 and 3. Comparisons with Manh Et Al. (2007) [15] indicated that under 15 t/ha composted manure, the tiller numbers of Para grass were lower (17.7 to 32.4) at similar ages, and this was also from 11.8 to 18.5 at 60 days [25], suggesting good establishment in this study. Overall, growth was uniform across treatments. The observation that tiller number per clump remained statistically similar across all manure treatments contrasts with findings by Lissu Et Al. (2023) [26], where farmyard manure increased tiller count by 48% in later harvests of Brachiaria mulato II (p < 0.05). This supports that while initial emergence may be uniform, manure can stimulate further tiller counts over time.

4.1.2. Plant Height Development

The plant height increased over time. While differences in harvest 1 only became significant at day 28 (p < 0.05), they were observed much earlier in harvest 2 (by day 14) and harvest 3 (by day 7). Once these differences emerged, the TDM7.5 and TDM10 treatments consistently outperformed lower-rate treatments in terms of height. Comparisons with Manh et al. (2007) [15] suggested that lower density and uniform composting resulted in higher height (58–73 cm) compared to this study’s 45.6–51.9 cm at day 28. The slower height in this study may stem from greater tiller density, spacing, soil factors, and environmental conditions. The TDM10 treatment consistently produced the greatest height, indicating its suitability for optimizing growth. The significant height gains in TDM7.5 and TDM10 after 28 days mirror global trends: a Nigerian study found that height rose significantly (p < 0.05) with increasing manure rates throughout growth [26]. Furthermore, Para grass response to nitrogen fertilizer also supports that nutrient enrichment (including manure-derived N) enhances forage height and protein content. Some Para grass cultivars reached plant heights of 160–170 cm at maturity, which is significantly taller than the 124–139 cm observed in TDM10 in this study. The implication is that taller stature typically correlates with greater biomass potential. Taller cultivars might help boost yield further, especially under optimized manure regimes.

4.1.3. Chemical Composition

No significant differences were observed among treatments in chemical composition in either litter (p > 0.05), and there was a slight difference in the composition of DM, OM, CP, NDF, and ash among three litters. The average over three harvests ranged as follows: DM 18.8–19.8%; OM 89.2–92.2%; CP 7.10–7.85%; NDF 60.5–63.8%; EE 2.29–2.82%; and ash 7.84–10.8%. The small variation in values for the chemical composition of Para grass among treatments and litters was possibly caused by the random sampling and variable analysis. Although higher CP levels were reported previously with more compost [27,28], these study’s values remained within acceptable ranges for ruminant forage. In the present study, manure topdressing did not significantly alter nutrient percentages, but quality remained suitable for animal feed. The lack of significant differences in nutrient composition across treatments is consistent with the broader Brachiaria literature. While nutrient levels typically remain within suitable ranges, yield rather than percentage changes with improved fertility, as seen in other Brachiaria studies. Consider split-applying compost or minerals after each cut to maintain vigor, and trial narrower spacing with improved cultivars. The chemical compositions (%) of Para grass were DM: 18.0 -18.4, CP: 8.58–11.1, NDF: 61.7–71.7, and ash: 5.81–12.3, also reported by Hong Et Al., 2023 [29], and Thanh Et Al., 2012 [30].

4.1.4. Biomass and Nutrient Yields

The results showed significant increases in FBM, DM, CP, and NDF yields with higher manure rates; the TDM10 treatment consistently yielded the highest. Averaged over three harvests (cuttings), the TDM10 results were 22.6 t/ha of fresh yield, 4.43 t/ha of dry yield, 0.347 t/ha of protein, and 2.68 t/ha of NDF, which were much higher than TDM0 averages (15.0, 2.98, 0.223, 1.90 t/ha, respectively). The results of experiments showed that composted cow manure impacts forage yield and quality (e.g., nutrient content, digestibility) through several key mechanisms, including nutrient supply, soil health improvement, and microbial activity enhancement [31,32,33]. Comparisons with earlier studies confirm the higher productivity under manure topdressing. The dramatic increase in biomass and nutrient yields under higher manure applications is well supported. In Tanzania, Brachiaria mulato II showed yield increases of 59% in height and 68% in biomass at later cuts after manure application [26]. Similarly, studies using organic fertilizer layers reported average fresh yields per cut up to ~15 t/ha for Para grass [15]. Mui [34] indicated that when harvesting it five times per year, the fresh biomass was 55.2 t/ha and dry matter biomass and CP was 13.8 and 1.17 t/ha. Wekgari et al. (2023) [17] stated that in Ethiopia, the DM yield per year of Para grass 18659 was 14.2 t/ha and Para grass 6964 was 13.9 t/ha, while with five cuttings a year, the DM yield (t/ha) in the TDM10 treatment was higher (22.2). The findings from the central Gondar Zone of Ethiopia also revealed that Para grass had significantly (p < 0.05) higher mean values for fresh and dry biomass yields compared to other Brachiaria species [35].

4.2. Cost–Benefit Analysis

Analyzing economic efficiency or profitability is a critical component of agricultural production research, especially in developing countries such as Vietnam, where practical applicability for producers and alignment with scientific and technological development are key concerns. In this study, the production cost of Para grass serves as an indicator of the effectiveness and practicality of current technical advancements.

Total costs increased slightly with manure use, but yield increased enough that cost per ton decreased from 34.7 to 24.4 USD, representing a 29.7% decrease. With market grass prices in Mekong Delta ranging from 43.5 to 52.2 USD/ton, profitability is promising. The TDM10 treatment maximizes return and minimizes per-ton cost and was advantageous under rising chemical fertilizer prices. Combining enhanced yield with reduced cost per ton makes TDM10 economically compelling. Although specific economic comparisons are not cited in the current literature, the yield increases with organic fertilization reported above generally improve cost-effectiveness given current market price ranges. Similarly, Luc and Thu (2021) [36] indicated that increasing the goat manure levels in the topdressing for Setaria grass enhanced the profit from 4.21 to 26.6% due to higher productivity, and Khang (2024) [37], in a study on Elephant grass, also presented higher profit (42.1%) for goat manure compared to inorganic fertilizer, which is more expensive. Small nitrogen supplements to organic regimens could enhance forage quality without compromising organic status and are worth exploring in future trials. Furthermore, Para grass accumulated the highest proline content in leaf tissues, indicating that its salinity tolerance capacity is higher than that of Paspalum and African grass with salt-affected soils in the Mekong Delta [38].

In summary, the findings indicate that (1) tiller density remained unaffected by manure rates and consistent across harvests, (2) plant height significantly improved under higher manure, with TDM10 outperforming the others, (3) chemical composition stayed statistically steady across treatments and harvests, (4) yield metrics (fresh, dry, CP, and NDF) all increased significantly with manure, especially at 10 t/ha/year, and (5) economic analysis showed that manure topdressing increases yield profitably, lowering production costs per ton.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the findings of this study, supplemental fertilization with composted cow manure markedly enhanced Para grass growth and productivity, driving significant gains in plant height as well as yields of fresh biomass, dry matter, crude protein, and neutral detergent fiber. In contrast, manure application exerted no notable influence on tiller density or forage quality. Among the tested rates, applying 10 t/ha/year produced the best outcomes in terms of yield, production efficiency, and economic return. This demonstrates practical feasibility in smallholder contexts with rich soils in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam, while avoiding any risks to the environment from excessive nutrients and reduced profits.

5.2. Recommendations

It is advisable to conduct further studies by applying even higher rates of cow manure to Para grass to evaluate additional growth responses and potential yield increases for better environmental and sustainable benefits in ruminant production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.T.P.T. and N.V.T.; methodology, L.T.P.T. and N.V.T.; software, S.-Y.L. and N.T.H.; validation, L.T.P.T. and N.V.T.; formal analysis, L.T.P.T.; investigation, N.V.T. and S.-Y.L.; resources, L.T.P.T. and N.V.T.; data curation, L.T.P.T. and S.-Y.L.; writing—original draft, L.T.P.T.; writing—review and editing, L.T.P.T., N.V.T. and S.-Y.L.; supervision, N.V.T. and S.-Y.L.; funding acquisition, L.T.P.T. and N.T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Faculty of Animal Sciences, College of Agriculture, Can Tho University, for providing laboratory facilities and assistance with sample analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gibbs, P.A.; Parkinson, R.J.; Misselbrook, T.H.; Burchett, S. Response of grass following the application of composted and untreated cattle manure. In Proceedings of the Accounting for Nutrients—A Challenge for Grassland Farmers in the 21st Century; Occasional Symposium No. 33; British Grassland Society: Warwickshire, UK, 1999; pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Larney, F.J.; Buckley, K.E.; Hao, X.; McCaughey, W.P. Fresh, Stockpiled, and Composted Beef Cattle Feedlot Manure. J. Environ. Qual. 2006, 35, 1844–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRoberts, K.C.; Ketterings, Q.M.; Parsons, D.; Hai, T.T.; Quan, N.H.; Ba, N.X.; Nicholson, C.F.; Cherney, D.J.R. Impact of Forage Fertilization with Urea and Composted Cattle Manure on Soil Fertility in Sandy Soils of South-Central Vietnam. Int. J. Agron. 2016, 2016, 4709024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, L.V. Conference on the Developing Effective and Sustainable Beef Cattle and Meat Goat Production. In Proceedings of the ILDEX VIETNAM 2024, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 31 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cuong, V.C.; Van, V.K.; Phung, L.D.; Thong, H.T.; Tien, T.M.; Thang, C.M.; Son, D.T.T.; Tien, D.V. Livestock Environment—Effective and Sustainable Management and Utilization of Livestock Waste; Science and Technology Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2013; 239p. [Google Scholar]

- Mottet, A.; de Haan, C.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Opio, C.; Gerber, P. Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röös, E.; Patel, M.; Spångberg, J.; Carlsson, G.; Rydhmer, L. Limiting livestock production to pasture and by-products in a search for sustainable diets. Food Policy 2016, 58, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, G.; Franzluebbers, A.; Carvalho, P.C.d.F.; Dedieu, B. Integrated crop–livestock systems: Strategies to achieve synergy between agricultural production and environmental quality. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 190, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, R.; Horwitz, P.; Godrich, S.; Sambell, R.; Cullerton, K.; Devine, A. What goes in and what comes out: A scoping review of regenerative agricultural practices. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 48, 124–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, N.; Guo, L.; Meng, J.; Ding, N.; Wu, G.; Jiang, G. Effects of Manure Compost Application on Soil Microbial Community Diversity and Soil Microenvironments in a Temperate Cropland in China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummerloh, A.; Kuka, K. The Effects of Manure Application and Herbivore Excreta on Plant and Soil Properties of Temperate Grasslands—A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iNaturalist. Brachiaria Mutica. Available online: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/292125-Brachiaria-mutica (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Keo, S.; Khen, K.; Holtenius, K.; Pauly, T. Para grass (Brachiaria mutica), ensiled or supplemented with sugar palm syrup, improves growth and feed conversion in “Yellow” cattle fed rice straw. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2013, 25, 133. [Google Scholar]

- Heuzé, V.; Thiollet, H.; Tran, G.; Sauvant, D.; Lebas, F. Para Grass (Brachiaria mutica). Available online: https://www.feedipedia.org/node/486 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Manh, L.H.; Dung, N.N.X.; Ngoi, T.P. Effects of planting spacing on the growth characteristics and productivity of Hymenachne acutigluma and Para grass (Brachiaria mutica) cultivated in Can Tho City. CTU J. Sci. 2007, 7, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Binh, L.H. Forage productivity of Para grass in Vietnam. In Integrated Crop-Livestock Production System and Fodder Trees; National Institute of Animal Husbandry: Ha-Noi, VietNam, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wekgari, Y.; Gamachu, N.; Dereba, F. Adaptation Trial of Brachiaria Grass Varieties in West and Kellem Wollega Zones of Oromia, Ethiopia. J. Plant Sci. Curr. Res. 2023, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.T.K.; Thu, N.V. Effect of Spophocarpus scandén replacing Brachiaria mutica on nutrient utilization, digestibility, and growth performance of crossbred rabbits in the Mekong delta of Vietnam. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2022, 132, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Trang, N.T.Q.; Hoa, P.T.B.; Nhung, N.T.T. Study on the effects of supplementing several types of organic fertilizers on sandy soil on growth, development, and fruit yield of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). J. Nat. Sci. Technol. 2017, 14, 139–148. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Quang, P.Q.; Trach, N.X. Feeds and Feeding Dairy Cows; Agricultural Publishing House: Ha Noi City, Vietnam, 2003. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Kien, T.T. Research on Productivity, Quality, and Efficiency of Some Introduced Grass Species in Beef Cattle Production. Doctoral Dissertation, Thai Nguyen University, Thai Nguyen, Vietnam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 1990; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nutritional Ecology of the Ruminant, 2nd ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Minitab. Minitab Reference Manual Release 16.2.0; Minitab Inc.: State College, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Can, T.M. Effect of Harvesting Time on Growth, Yield, and Chemical Composition of Para Grass (Brachiaria mutica) Planted in Vinh Long Province, Vietnam. Undergraduate Thesis, College of Agriculture, Can Tho University, Can Tho, VietNam, 2021. (In Vietnamese). [Google Scholar]

- Lissu, C.; Manyanda, B.; Lulandala, L.L. Effects of Organic Fertilization on Growth Response of Brachiaria (Mulato II) in Lushoto, Tanzania. East Afr. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 6, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, T.T. Effect of Goat Manure Levels on Biomass Yield, Quality and Intake of Setaria Sphacelata of Cattle. Master’s Thesis, Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture, Can Tho University, Can Tho, Vietnam, 2022; pp. 25–27. (In Vietnamese). [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, F. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer on yield and protein content of Brachiaria mutica (Forsk.) Stapf, Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers., and Setaria splendida Stapf in Uganda. Trop. Agric. 1974, 51, 523–529. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, N.T.T.; Trang, N.T.N.; Hieu, L.T.M. Effects of a supplement of yeast-fermented broken rice on nitrogen retention and methane emissions in growing goats fed Para grass (Brachiaria mutica). Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2023, 35, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, V.D.; Thu, N.V.; Preston, T.R. Effect of potassium nitrate or urea as NPN source and levels of Mangosteen peel on in vitro gas and methane production using molasses, Operculina turpethum and Brachiaria mutica as substrate. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2012, 24, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, T.J.; Muir, J.P. Dairy Manure Compost Improves Soil and Increases Tall Wheatgrass Yield. Agron. J. 2006, 98, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, G.L.; Bernard, J.K.; Hubbard, R.K.; Allison, J.R.; Lowrance, R.R.; Gascho, G.J.; Gates, R.N.; Vellidis, G. Managing Manure Nutrients Through Multi-crop Forage Production. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 2243–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Jeong, S.T.; Das, S.; Kim, P.J. Composted Cattle Manure Increases Microbial Activity and Soil Fertility More Than Composted Swine Manure in a Submerged Rice Paddy. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, N.T. Country Pasture/Forage Resource Profiles. Vietnam; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; Available online: https://ees.kuleuven.be/eng/klimos/toolkit/documents/661_Vietnam.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Tarekegn, A.; Amsalu, D.; Gashaw, E.; Adane, K. Forage yield and quality traits of Brachiaria spp. grass species at central Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. J. Rangel. Sci. 2023, 13, 132329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, T.T.; Thu, N.V. Effect of goat manure on the growth, yield, and quality of Setaria grass (Setaria sphacelata) in Can Tho City. J. Livest. Sci. Technol. 2021, 125, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Khang, L.Q. Effects of Organic and Chemical Fertilizers on the Growth, Yield, and Production Costs of Elephant Grass. Undergraduate Thesis, Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture, Can Tho University, Can Tho, Vietnam, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Viet, V.H.; Han, P.T.; Tung, N.C.T.; Dong, N.M.; Trang, N.T.D. Assessment of increasing salt tolerance of Para grass (Brachiaria mutica), Paspalum (Paspalum atratum), and Setaria (Setaria sphacelata) in experimental conditions. CTU J. Sci. 2019, 55, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).