Abstract

This study examined how environmental attitudes, message framing, and cultural context shape conservation judgments in national parks and protected areas (NPPAs). Participants from the U.S. (N = 181) and India (N = 157) reported their environmental attitudes using the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale and responded to scenarios depicting unsustainable behaviors (trampling vegetation, feeding wildlife, and littering) framed in either gain or loss terms. Regression analyses showed that stronger pro-environmental attitudes consistently predicted greater disapproval of unsustainable actions and higher willingness to donate. Indian respondents generally expressed stronger pro-conservation judgments, and the NEP × Country interaction was significant for trampling, indicating cultural moderation of attitude effects. Message framing had minimal impact, reaching significance only for littering and showing no moderation by country. NPPA pass ownership positively influenced all outcomes, while age predicted donation intentions only. These findings underscore the importance of values-aligned, context-sensitive strategies to encourage sustainable behaviors across diverse cultural settings.

1. Introduction

Promoting environmentally responsible behavior is essential for conserving protected areas and safeguarding ecosystem services, which include biodiversity preservation, carbon sequestration, water purification, soil protection, cultural heritage maintenance, and recreational opportunities [1]. Recreational use, in particular, drives nature-based tourism and generates economic benefits for local communities [2]. However, these services are not always complementary: maximizing short-term gains from tourism can negatively affect conservation outcomes, highlighting the trade-offs inherent in managing protected areas [3].

Nature-based tourism is rapidly expanding. Globally, protected lands receive over eight billion visits annually. In the U.S., National Park Service sites have seen visitation rise from 266 million in 2003 to 325 million in 2023, with per capita visitation remaining relatively stable [1]. As populations continue to grow [4], the tension between recreational use and conservation goals is likely to intensify, making visitor behavior a central determinant of environmental outcomes.

To mitigate negative impacts, NPPA management prohibits behaviors such as littering, feeding wildlife, off-trail hiking, plant removal, and excessive noise, and encourages sustainable conduct through educational campaigns and staff-led initiatives. Despite these efforts, tourism-related degradation persists in many areas [5]. Research has explored message framing as a tool to influence visitor behavior, with mixed results: some studies report strong effects, while others suggest individual values and situational context may matter more [6,7,8,9]. Understanding how message framing interacts with personal attitudes and social context is therefore a critical gap in the literature.

This study focuses on two key drivers of sustainable behavior: environmental attitudes and societal norms. The New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) framework [10,11] distinguishes nature-centered from human-centered worldviews, with stronger nature-centered orientations linked to more sustainable actions. Norm activation theory further suggests that environmentally conscious individuals act when they feel morally responsible for ecological problems, reinforcing the likelihood of pro-environmental behavior [12,13].

Societal and personal norms shape how sustainable actions are perceived and enacted. Personal norms, grounded in moral responsibility, encourage environmentally responsible behavior, while societal norms define acceptable conduct and create social pressure to comply [13]. In highly polarized societies, however, environmental norms often align with political or social identities rather than universal principles, complicating efforts to promote collective action and normative messaging [14,15,16]. Differences in norms between groups, such as strong environmentalists and skeptics, may reduce the effectiveness of campaigns aimed at encouraging sustainable behavior.

Despite the extensive literature on message framing and environmental attitudes, three critical gaps remain. First, most studies focus on high-consequence behaviors or policy preferences, leaving everyday, low-risk actions in protected areas largely unexplored. Second, few studies examine how personal attitudes, societal polarization, and framing interact to shape conservation judgments across cultural contexts. Third, sustainability research is heavily concentrated in the U.S., raising concerns about generalizing findings across cultural contexts [17].

Studying tourist groups across diverse cultural and political contexts is therefore both necessary and timely [18]. In this study, we examine the combined effects of environmental attitudes, message framing, and societal context to understand how these factors influence environmentally responsible behavior in NPPAs. By highlighting which visitor groups are more receptive to particular interventions, such as values-aligned educational campaigns, staff-led initiatives, or tailored messaging strategies, this research can inform the design of more effective approaches to promote sustainable behaviors, reduce tourism-related degradation, and support long-term conservation goals.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Attitudes and Societal Polarization

The New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) framework is the most widely accepted measure of environmental attitudes [10,11], with its central component of environmental concern. The scale [11] covers a broad range of attitudes, including limits to growth, anti-anthropocentrism, the fragility of nature and human-nature balance, humans’ control over nature, and the possibility of eco-crisis. Studies point to the multi-dimensionality of the NEP scale: “… populations will no doubt vary in the degree to which the NEP beliefs are organized into a highly consistent belief system, and in many cases, it will no doubt be more appropriate to treat the NEP as multidimensional” ([11] p. 436). The scale is known for its reliability and validity, discrimination among social groups, and broad public appeal [19]. The NEP scale has been used in various topical and behavioral contexts, including nature-based tourism [20,21], and stands strong as “the key source for a coherent environmental belief system” ([19] p. 54).

Personal norms, grounded in moral responsibility, encourage environmentally responsible behavior when individuals internalize the importance of stewardship, while societal norms provide guidance and social pressure, shaping perceptions of acceptable behavior and reinforcing the legitimacy of sustainable action [13]. In polarized societies, environmental issues often align with political or social identities rather than shared scientific concerns, reducing the influence of norms and complicating collective behavior [14,15,16]. This can lead to reduced consensus on environmental priorities, such as climate change or conservation efforts, and increased resistance to policies perceived as aligned with the ‘other side.’

Political ideology further shapes environmental attitudes. Liberal ideologies, emphasizing collective welfare and equity, are generally associated with higher environmental concern and support for policies such as renewable energy or carbon regulation. Conservative ideologies, emphasizing individual freedom and economic growth, tend to be more skeptical of environmental regulations perceived as restrictive or costly [14,22,23]. The research found that NEP attitudes mediate the effect of socio-demographic variables such as the individual’s political ideologies or proximity of the place of residence to nature on environmental concerns [19,22,24].

2.2. Message Framing in Nature-Based Tourism

Message framing involves presenting information in terms of gains or losses to influence decision-making [25,26]. Gain frames highlight positive outcomes of sustainable behavior (e.g., “By choosing eco-friendly tours, you help preserve wildlife and support local communities”), whereas loss frames emphasize negative consequences of unsustainable actions (e.g., “Failing to follow sustainable practices can harm wildlife and local communities”).

Framing operates via cognitive and emotional pathways. Gain frames appeal to tourists’ desire for enriching experiences, aligning with the emotional benefits of nature-based tourism—joy, fulfillment, and connection to nature—making sustainable choices feel rewarding [6,8,9]. Loss frames invoke avoidance and guilt, motivating action in high-risk situations but potentially reducing the attractiveness of leisure experiences [27,28,29]. Neuroimaging evidence suggests that gain frames promote long-term commitment, while loss frames drive immediate, short-term behavior [30].

Framing effectiveness is moderated by factors such as language intensity, personality traits, social class, psychological distance, and perceived risk [31,32,33]. In nature-based tourism, messages emphasizing visitor experience often outperform those emphasizing wildlife protection alone [6,8]. Much of the research, however, has focused on high-consequence behaviors, leaving open the question of how framing influences mundane, low-risk behaviors such as littering or feeding wildlife. We therefore expect positive (gain) framing to be more effective than negative (loss) framing in promoting sustainable behavior among recreational visitors.

2.3. Integrating Societal Context: The U.S. and India

This study focuses on two populations with contrasting levels of polarization around environmental issues: the U.S. and India [18,34]. In the U.S., polarization is high, driven by a deeply entrenched partisan divide and widespread climate change skepticism [15,23,35]. Most environmentally skeptical books are U.S.—published, highlighting ideological opposition [23]. A 2020 Brown University study found that the U.S. is polarizing faster than other developed nations, including Canada, the U.K., Germany, and Australia (https://www.brown.edu/news/2020-01-21/polarization, accessed on 24 September 2025). While political affiliation is often used as a proxy for environmental attitudes, Huber (2020) [15] suggests personal tendencies toward populist solutions may also predict attitudes independently of party identity.

In contrast, India faces significant environmental challenges—air and water pollution, deforestation, and waste management—exacerbated by rapid economic development and population growth. Societal polarization on environmental protection is relatively low [36]. Differences in opinion generally reflect competing priorities and awareness rather than outright denial. Polarization arises from tensions between economic development and environmental protection rather than ideology. Environmental issues are frequently framed in terms of public health or livelihoods, fostering broader societal consensus [37]. Media coverage reflects this difference: U.S. media (e.g., The New York Times) focus on divisive issues such as energy costs, whereas Indian media (e.g., The Hindu) emphasize high-level negotiations and environmental costs [38].

Thus, India exhibits a more pragmatic, environment-oriented form of polarization, with less ideological resistance to environmental protection. These contrasts make the U.S. and India a valuable comparative lens for examining how societal polarization interacts with message framing and environmental attitudes to influence sustainable behavior in nature-based tourism contexts.

2.4. Research Expectations

Despite growing research on message framing and environmental attitudes, there is limited understanding of how these factors jointly influence everyday, low-risk conservation behaviors in diverse cultural contexts. Most studies focus on high-stakes or safety-related actions, examine attitudes or norms in isolation, and rely predominantly on U.S. samples, leaving open questions about the moderating role of societal polarization. By comparing the U.S. and India, this study addresses these gaps, offering insights into the combined effects of environmental attitudes, message framing, and cultural context, and informing targeted strategies for promoting sustainable behavior in national parks and protected areas. Thus, based on the literature, the study formulated and examined three interrelated expectations:

- Message framing: Positive (gain) frames will be more effective than negative (loss) frames in promoting sustainable behavior in low-risk NPPA settings.

- Environmental attitudes: Individuals with stronger pro-environmental attitudes will show reduced tolerance for unsustainable behaviors.

- Societal polarization: Polarization will modulate responses to unsustainable behaviors and support for environmental protection, with the U.S. showing more divided patterns and India more cohesive responses.

3. Method

3.1. Samples: U.S. and India

The samples of US and Indian NPPA visitors were drawn from the Amazon Mechanical Turks (MTurk). MTurk is a crowdsourcing online platform where the human intelligence tasks posted by requesters are completed by anonymous workers in exchange for compensation. Importantly, the MTurkers are overwhelmingly represented by the US and India workers [39], justifying platform selection. MTurk is widely used in research, mainly for its ability to provide high-quality data [40] on large and diverse population samples quickly and at a low cost. For instance, Google Scholar reports over 500 tourism publications completed using MTurks. MTurks are reasonably representative of the general population across most psychological dimensions [41], and under proper quality control, MTurk crowdsourcing and traditional survey outcomes are consistent [42]. This study followed the MTurk best practice recommendations [43]. The participants had at least a 95% approval rate at the site (that is, only the premium quality workers participated in the study). Compensation was set targeting the average earning of $6 per hour, which the community of MTurk workers recommended as the ethical compensation rate [44]. To classify participants by country (U.S. or India), we collected participants’ zip codes.

3.2. Message Framing

Three rules of sustainable behavior were selected as the basis for the environmental messages, reflecting the most frequent unsustainable behaviors of NPPA visitors [45] and the severity of the consequences of breaking them: (1) stay on trails, (2) do not feed wildlife, and (3) take your trash with you. Formal trails protect vulnerable resources and prevent ecological damage. Walking off designated trails can lead to soil erosion, vegetation damage, and disturbance to wildlife (e.g., [46]). Genuine desire of tourists to satisfy their curiosity by interacting with animals frequently devolves into fostering wildlife dependency on human-provided food, diminishing their natural foraging skills, thus jeopardizing their welfare (e.g., [47]). Finally, improper waste disposal leads to pollution of rivers and land, threatening animal habitats and increasing the risk of wildlife accidentally ingesting litter, which harms their health and survival [48]. Thus, two distinct framings of the rules, emphasizing either the positive consequences of compliance or the negative consequences of non-compliance were designed (Table 1) and pre-tested with about 30 college students. The framing was overwhelmingly recognized as intended, with minimal misinterpretation.

Table 1.

Message framing. Bold font indicates frame name.

3.3. Study Design

To qualify, participants had to have visited an NPPA within the past three months. After completing NEP attitude questions, they viewed a photo of a wooden board displaying park rules to help mentally recall the park experience. Participants were then randomly assigned to the experimental stimulus (Table 1): those in the positive framing condition wrote about the benefits of following rules, while those in the negative condition reflected on the consequences of breaking them. This step was mandatory.

Participants then viewed three photographs depicting rule violations: trampling vegetation, feeding a squirrel, and dropping a snack wrapper. After each image, they responded to four Likert-scale items (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) measuring emotional and behavioral reactions, such as negative emotions, likelihood of reminding others, commenting on social media, and refraining from similar behavior. A higher score indicated greater disapproval. Participants also reported their willingness to donate to the NPPA.

A quality control procedure following Smith et al. (2016) [49] was applied to the collected data, targeting the response patterns characteristic of “speeding” and “cheating”. The median completion time was 10 min. Manipulation checks based on participants’ comments confirmed that the framings were recognized. Six respondents from countries other than India and the U.S. were excluded. The final dataset contained 338 respondents. All questions except demographics were forced-entry (Table 2), minimizing the amount of missing data.

Table 2.

Respondents’ profiles.

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Profile

Respondent profile (Table 2) was similar for Indian (N = 157) and US (N = 181) participants, except for education and income (see Section 5 for discussion of this issue). The gender split was almost even, with slightly more male respondents. Most respondents were between 25 and 44 years old and held bachelor’s degrees, with the political orientation slightly leaning toward liberals. These statistics are characteristic of the MTurk workers in general [39,50]. Most participants (88%) visited natural parks at least once per month.

4.2. Consistency and Direction of NEP Attitudes

Participants’ environmental attitudes were measured using the 15-item NEP scale [11] (Table 3), with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items reflect different dimensions of environmental beliefs and can be broadly categorized as nature-centric (eight items, e.g., “The balance of nature is very delicate and easily upset”) or human-centric (seven items, e.g., “Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs”).

Table 3.

Original NEP items for the US and India. Index k in the first column differentiates between the nature-centric (k = +1, items 1–8) and human-centric (k = −1, items 9–15) dimensions of environmental beliefs.

Preliminary principal component analyses indicated that the NEP item structure differed across the U.S. and Indian samples, suggesting that strict measurement invariance could not be assumed. Because the factor configuration was not comparable, multi-group confirmatory factor analysis was not pursued. Instead, we retained all 15 items and standardized participants’ NEP responses within each country (z-scores). This conservative, item-level approach minimizes cross-national differences in response styles and enables comparison of behavioral associations rather than latent factor means [51].

We then constructed a key vector (k) representing the NEP structure, coding eco-centric items as +1 and anthropocentric items as −1 (Table 3). Each participant’s standardized responses were collected into a response vector (z_person), and the alignment with the key vector was quantified using the Pearson correlation coefficient: r = cor (z_person, k). The sign of r indicates the participant’s overall worldview orientation (positive = eco-centric; negative = anthropocentric), while the absolute magnitude ∣r∣ reflects the degree of internal consistency with the eco- versus anthropocentric structure. Note that Pearson’s correlation is equivalent to cosine similarity in this context, capturing both direction and consistency without loss of information.

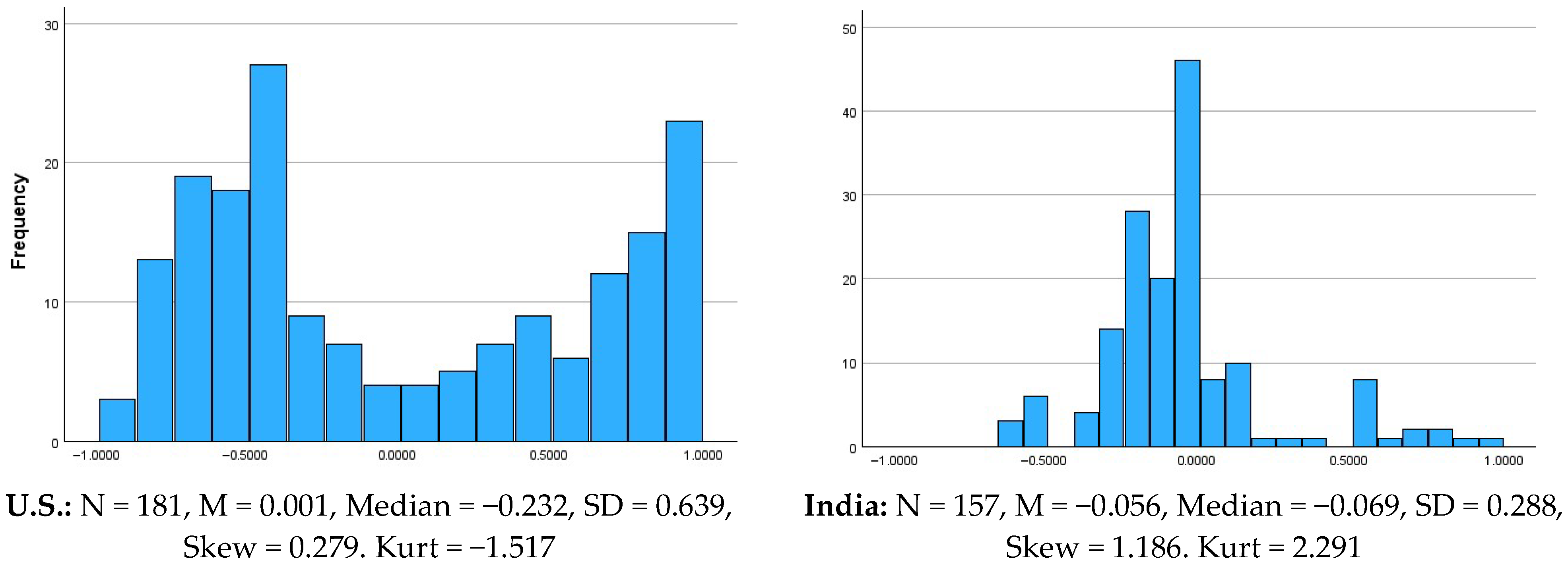

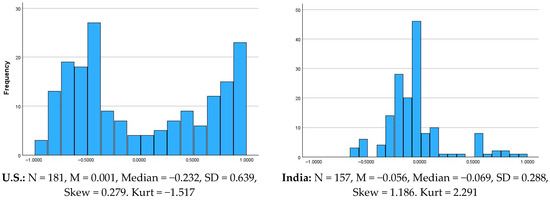

Distributional patterns differed by country. The U.S. sample exhibited a bimodal distribution, with respondents tending to be either strongly pro-environmental or anthropocentric, indicating polarization in environmental attitudes. In the Indian sample, a small group displayed high pro-environmental attitudes, while the middle 50% ranged from −0.20 to −0.02, indicating generally balanced to slightly human-centered attitudes. Distributions are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

NEP attitudes consistency score.

4.3. Testing Expectations: Regression Analysis

To examine whether disapproval response to non-sustainable behaviors varied as a function of environmental attitudes, country, and message framing, we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis using participants’ NEP scores as a continuous measure. In the first step, control variables including demographic characteristics (gender, age, and education), political views, and holding an NPPA pass were entered. In the second step, the main effects of NEP, country, and message framing (positive vs. negative expression of park rules) were added. In the third step, two interaction terms (NEP × Country and Frame × Country) were included to test whether the association between environmental attitudes and responses to non-sustainable behaviors differed across countries and whether the framing effect differed between the two countries. Treating NEP as a continuous variable allowed us to retain full variability in attitude orientation, while the hierarchical approach controlled for potential confounding variables and directly tested the moderating effects of country. The NEP variable was grand-mean centered across countries. This created a single reference point common to both US and India samples. Dependent variables were Trample (α = 0.86), Feed (α = 0.83), and Litter (α = 0.71) averaged across original statements, and Donate to NPPA (Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of dependent variables.

The four regression equations were as follows:

where

- = outcome variable (Disapprove of behavior or Donate),

- = intercept,

- = effect of environmental attitudes (NEP),

- = main effect of Country (U.S. = 0, India = 1),

- = interaction between NEP and Country,

- = main effect of message Framing (Negative = 0; Positive = 1),

- = interaction between Framing and Country,

- = effects of control variables c (gender, age, education, political views, NPPA pass), and

- = error term.

Among the control variables, political views were a significant predictor for disapproval of trampling vegetation and littering, with negative coefficients indicating that more liberal respondents (higher scores) expressed lower disapproval than more conservative respondents (see Table 5). Possession of an NPPA annual pass was strongly and positively associated with disapproval across all three behaviors, suggesting that passholders tended to evaluate these actions more negatively. Demographic variables were not significant predictors. Collectively, the control variables accounted for 6% of the variance in disapproval of trampling vegetation, 9% in feeding wildlife, and 5% in littering.

Table 5.

Responses to unsustainable behaviors in NPPAs: Regression analysis. Unstandardized regression coefficients reported to preserve the interpretability and facilitate replication. Bold font indicates statistically significant coefficients (p < 0.05).

Regression analyses showed that pro-environmental attitudes (NEP; b1) significantly predicted disapproval across all three behaviors: trampling vegetation, feeding wildlife, and littering. In each case, higher NEP scores were associated with greater disapproval (see b1 in Table 5). Country (b2) was also a consistent predictor, with Indian respondents reporting higher disapproval than U.S. respondents at the mean NEP score (see b2 in Table 5). The NEP × Country interaction (b3) was negative across all behaviors, indicating that the positive relationship between NEP and disapproval was weaker in India than in the U.S.; however, this effect reached statistical significance only for trampling vegetation. For littering, a significant main effect of message framing (b4 = −0.76, p = 0.015) indicated that participants exposed to gain frames reported lower disapproval than those exposed to loss frames, with no difference between countries, as the Frame × Country interaction (b5) was not significant. The intercepts (b0) represent the predicted baseline disapproval for U.S. respondents at the mean NEP score under the reference framing condition.

For intentions to donate, the control variables collectively explained 23% of the variance, with more liberal political orientation and NPPA annual pass ownership each positively predicting donation intention. Adding the focal predictors (framing, NEP, country, and the interaction terms) accounted for an additional 5% of variance. Both NEP (b1) and Country (b2) emerged as significant positive predictors, indicating that stronger pro-environmental attitudes and being from India were associated with greater willingness to donate. Neither the NEP × Country (b3) nor the Frame × Country (b5) interactions explained additional variance. These results mirror the disapproval models in showing consistent positive effects of NEP and country, while highlighting the particularly strong influence of political orientation and NPPA pass ownership on donation intentions.

5. Discussion

The regression analyses largely support the expectations outlined in Section 2.4 Research Expectations. Pro-environmental attitudes were consistently associated with stronger disapproval of unsustainable behaviors and greater willingness to donate to conservation efforts, highlighting the central role of personal environmental values in shaping conservation-relevant judgments. Country differences further indicate that social context matters: Indian respondents generally exhibited higher disapproval and donation intentions than U.S. respondents. However, the NEP × Country interaction was significant only for trampling, suggesting that the influence of environmental attitudes can vary depending on the specific behavior. The consistent effects of NEP and country across both behavioral disapproval and donation intentions underscore that environmental worldviews play a central role in shaping conservation judgments across cultural contexts. At the same time, the comparatively stronger impact of age, political orientation, and NPPA pass ownership on donation indicates that financial support for conservation is embedded within broader social and experiential contexts.

The NEP distributions (Figure 1) revealed clear contrasts between the U.S. and Indian samples, reflecting differences in societal polarization as anticipated in the Research Expectations Section. In the U.S., the bimodal distribution (M = 0.001, Median = −0.232, SD = 0.639, Skew = 0.279, Kurtosis = −1.517) points to two distinct subgroups, environmentally concerned versus skeptical, consistent with high partisan polarization. This divergence helps explain the heterogeneous responses observed in the U.S. regression analyses, where NEP attitudes predicted varying levels of disapproval toward unsustainable behaviors. In India, the distribution was unimodal and peaked (M = −0.056, Median = −0.069, SD = 0.288, Skew = 1.186, Kurtosis = 2.291), indicating more cohesive attitudes. Notably, the mean slightly favors a pro-human orientation, reflecting moderate anthropocentric perspectives linked to the country’s ongoing industrial and economic development, where balancing environmental protection with livelihoods is a central concern. This pragmatic stance suggests that normative and framed messages in India are likely to elicit more uniform responses, supporting Research Expectation 3 (Section 2.4) that lower societal polarization strengthens the alignment between environmental attitudes and sustainable behaviors.

These findings carry practical implications for managing NPPAs. Younger visitors, particularly in the U.S., tend to hold more human-centric but not extreme attitudes (18–34: NEP = −0.24; 35–44: NEP = 0.23; 45+: NEP = 0.11), whereas in India, older visitors show the most pronounced pro-environmental attitudes (18–34: NEP = −0.14; 35–44: NEP = −0.09; 45+: NEP = 0.60). Those who are neither strongly eco-centric nor extremely human-centered are arguably more receptive to educational interventions, as they are less prone to ideological rigidity and confirmation bias associated with strong worldviews [52]. When combined with broader trends of younger generations, particularly in the U.S., becoming more moderate in their political views [53], these results suggest that societal polarization around environmental protection may eventually decline. Encouragingly, NPPA passholders consistently showed higher disapproval and donation intentions, underscoring the importance of engagement experiences in promoting conservation behaviors. This highlights an opportunity for targeted, values-aligned messaging to foster sustainable behaviors, particularly among age groups whose environmental attitudes are still developing and relatively flexible.

Message framing exerted only a limited effect, reaching significance for littering, where participants exposed to gain-framed messages reported slightly lower disapproval compared to those exposed to loss-framed messages, whereas the Framing × Country interaction did not reach significance. This aligns with prior research showing mixed effects of gain- versus loss-framed messages, suggesting that framing effectiveness is context-dependent. In familiar and low-risk scenarios such as recreational littering, loss-framed messages may have been more effective because they prompted participants to recall instances when they themselves occasionally violated rules, evoking feelings of guilt [29]. This avoidance-focused response [27,28] may have outweighed the typical tendency in leisure contexts to respond more to positive, reward-oriented cues [8,9]. The high familiarity of the scenarios may also have reduced attention and engagement, a phenomenon known as habituation or automatic processing [54]. Across behaviors, individual environmental attitudes and social context consistently predicted responses, reinforcing the importance of considering both personal values and broader norms when designing interventions.

Several limitations temper these conclusions. Demographic differences between the Indian and U.S. samples, particularly regarding education and income, may limit generalizability. However, adjustments for purchasing power parity help align income distributions across countries (https://wdi.worldbank.org/table/4.16, accessed on 24 September 2025), and MTurk’s English proficiency requirement plausibly explains the underrepresentation of less-educated Indian respondents [55]. A comparative analysis of Indian and American MTurk samples is thoroughly described in Boas et al. (2020) [56]. Moreover, our regression analyses revealed only weak or nonsignificant effects of demographic controls, suggesting that education, income, and related variables exert limited influence on the main relationships examined. Together, these factors indicate that while demographic biases warrant cautious interpretation, they are unlikely to substantially compromise the generalizability of the attitudinal patterns observed.

A further limitation concerns the reliance on self-reported attitudes and behavioral intentions rather than observed behaviors, which may be susceptible to social desirability bias. Nonetheless, cross-tabulations showed that participants already supporting NPPAs were more likely to donate (U.S.: χ2 = 46.90, p < 0.001; India: χ2 = 21.66, p < 0.001), reinforcing the real-world relevance of these measures. Future studies should incorporate experimental or observational designs to validate and extend these findings. Finally, inattentive responses [57] might introduce measurement error, although prior research indicates high replicability of MTurk data [58].

In summary, the results largely confirm the expectations stated in the Research Expectations Section: NEP attitudes consistently shaped responses to unsustainable behaviors in NPPAs, with participants holding more pro-environmental orientations expressing stronger disapproval and greater willingness to donate, while those with more human-centric orientations showed weaker responses. Message framing exerted only a limited effect, significant for littering but not moderated by country, likely due to the low-risk, familiar scenarios used. Social context also influenced overall engagement, with stronger and more cohesive responses observed in India, where NEP attitudes were less polarized, compared to the more divided U.S. These findings underscore the central argument advanced in the introduction: that promoting conservation behaviors cannot rely on universal strategies such as message framing alone, but must instead account for the interaction between individual worldviews and societal contexts. By demonstrating how NEP orientations and polarization patterns shape conservation judgments across two distinct cultural settings, this study highlights the need for values-aligned, context-sensitive interventions to foster sustainable behavior. Future research should replicate these results in diverse settings and examine how proximity to nature, political orientation, and other social factors condition responses to sustainability messages under varying conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and R.B.; Methodology, S.S. and A.K.; Formal analysis, S.S.; Investigation, R.B.; Data curation, A.K.; Writing—original draft, S.S., R.B., A.K. and T.C.; Writing—review & editing, S.S.; Visualization, S.S.; Supervision, S.S.; Project administration, S.S.; Funding acquisition, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Data collection for this research was supported by Bill Sims Student Research Award at the Department of Tourism, Hospitality and Event Management, University of Florida.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Institutional Review Board IRB#2, University of Florida IRB202101230, 6 November 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author due to IRB-imposed restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- National Park Service. 2023. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/visitation-numbers.htm (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Dangi, T.B.; Gribb, W.J. Sustainable ecotourism management and visitor experiences: Managing conflicting perspectives in Rocky Mountain National Park, USA. In Stakeholders Management and Ecotourism; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 136–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.M.; Peterson, G.D.; Gordon, L.J. Understanding relationships among multiple ecosystem services. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 1394–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Population. United Nations. 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/population#:~:text=Our%20growing%20population&text=The%20world’s%20population%20is%20expected,billion%20in%20the%20mid%2D2080s (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Cui, Q.; Ren, Y.; Xu, H. The escalating effects of wildlife tourism on human–wildlife conflict. Animals 2021, 11, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, K.M.; Leong, K.; Melena, S.; Teel, T. Encouraging safe wildlife viewing in national parks: Effects of a communication campaign on visitors’ behavior. Environ. Commun. 2020, 14, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Knezevic Cvelbar, L.; Grün, B. Do pro-environmental appeals trigger pro-environmental behavior in hotel guests? J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Taff, B.D.; Lawhon, B.; Benfield, J.A.; Kreye, M.; Newton, J.; Miller, L.; Newman, P. The Impact of Message Framing on Wildlife Approach During Ungulate Viewing Experiences in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. J. Interpret. Res. 2023, 28, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, C. Effective Pro-environmental Communication: Message Framing and Context Congruency Effect. J. Travel Res. 2023, 64, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D. The “new environmental paradigm”. J. Environ. Educ. 1978, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Jones, R.E. New trends in measuring environmental attitudes: Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clulow, Z.; Ferguson, M.; Ashworth, P.; Reiner, D. Comparing public attitudes towards energy technologies in Australia and the UK: The role of political ideology. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 70, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.A. The role of populist attitudes in explaining climate change skepticism and support for environmental protection. Environ. Politics 2020, 29, 959–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.Z.; Waltman, L. A large-scale bibliometric analysis of global climate change research between 2001 and 2018. Clim. Change 2022, 170, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, M.; Kashima, Y.; Steg, L.; Dietz, T. Environmental decision-making in times of polarization. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2023, 48, 477–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Dunlap, R.E.; Hong, D. Ecological worldview as the central component of environmental concern: Clarifying the role of the NEP. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 32, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, N.J. An integrated model of travelers’ pro-environmental decision-making process: The role of the New Environmental Paradigm. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarinc, A.; Ergun, G.S.; Aytekin, A.; Keles, A.; Ozbek, O.; Keles, H.; Yayla, O. Effect of climate change belief and the new environmental paradigm (NEP) on eco-tourism attitudes of tourists: Moderator role of green self-identity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M.; Willer, R. The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, P.J.; Dunlap, R.E.; Freeman, M. The organisation of denial: Conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism. Environ. Politics 2008, 17, 349–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, C.M.; Schmitt, M.T. Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.P.; Schneider, S.L.; Gaeth, G.J. All frames are not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 76, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueddefeld, J.; Ostrem, J.; Murphy, M.; Maraj, R.; Halpenny, E. Lessons for becoming bison wise and bear aware in Elk Island National Park. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2024, 29, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessa, S.J.; Rothman, J.M. The importance of message framing in rule compliance by visitors during wildlife tourism. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, K.F.; Sintov, N.D. Guilt consistently motivates pro-environmental outcomes while pride depends on context. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minich, M.; Chang, C.T.; Kriss, L.A.; Tveleneva, A.; Cascio, C.N. Gain/loss framing moderates the VMPFC’s response to persuasive messages when behaviors have personal outcomes. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2023, 18, nsad069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, S.; Chen, K.; Jin, R. The effect of message framing and language intensity on green consumption behavior willingness. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 2432–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Ye, C.; Huang, S.; Su, L. The “Green Persuasion Effect” of Negative Messages: How and When Message Framing Influences Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Travel Res. 2024, 00472875241289571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Liu, D.; Ma, F.; Xu, X. Good news or bad news? How message framing influences consumers’ willingness to buy green products. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 568586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; McCright, A.M.; Yarosh, J.H. The political divide on climate change: Partisan polarization widens in the US. Environ.: Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2016, 58, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Båtstrand, S. More than markets: A comparative study of nine conservative parties on climate change. Politics Policy 2015, 43, 538–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubash, N.K.; Khosla, R.; Kelkar, U.; Lele, S. India and climate change: Evolving ideas and increasing policy engagement. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 395–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Swarnakar, P. How fair is our air? The injustice of procedure, distribution, and recognition within the discourse of air pollution in Delhi, India. Environ. Sociol. 2023, 9, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylä-Anttila, T.; Eranti, V.; Kukkonen, A. Topic modeling for frame analysis: A study of media debates on climate change in India and USA. Glob. Media Commun. 2022, 18, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difallah, D.; Filatova, E.; Ipeirotis, P. Demographics and dynamics of mechanical turk workers. In Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Marina Del Rey, CA, USA, 5–9 February 2018; pp. 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinsky, A.J.; Huber, G.A.; Lenz, G.S. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon. com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Anal. 2012, 20, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCredie, M.N.; Morey, L.C. Who are the Turkers? A characterization of MTurk workers using the personality assessment inventory. Assessment 2019, 26, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, G.; Chandler, J.; Ipeirotis, P.G. Running experiments on amazon mechanical turk. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2010, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Villamor, I.; Ramani, R.S. MTurk research: Review and recommendations. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We Are Dynamo. Guidelines for Academic Requesters, Version 1.1. 2014. Available online: https://irb.northwestern.edu/docs/guidelinesforacademicrequesters-1.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Esfandiar, K.; Dowling, R.; Pearce, J.; Goh, E. Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: An integrated structural model approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesa, D.; Cerdà, A. Soil erosion on mountain trails as a consequence of recreational activities. A comprehensive review of the scientific literature. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orams, M.B. Feeding wildlife as a tourism attraction: A review of issues and impacts. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Environmental Contaminants and Their Impact on Wildlife. In Toxicology and Human Health: Environmental Exposures and Biomarkers; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Roster, C.A.; Golden, L.L.; Albaum, G.S. A multi-group analysis of online survey respondent data quality: Comparing a regular USA consumer panel to MTurk samples. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3139–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, B.D.; Ewell, P.J.; Brauer, M. Data quality in online human-subjects research: Comparisons between MTurk, Prolific, CloudResearch, Qualtrics, and SONA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milfont, T.L.; Fischer, R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, P.J.; Sparks, A.C.; Sherman, D.K. Support for environmental protection: An integration of ideological-consistency and information-deficit models. Environ. Politics 2017, 26, 253–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Youth Poll. 2024. Available online: https://iop.harvard.edu/youth-poll/48th-edition-fall-2024 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Rankin, C.H.; Abrams, T.; Barry, R.J.; Bhatnagar, S.; Clayton, D.F.; Colombo, J.; Coppola, G.; Geyer, M.A.; Glanzman, D.L.; Marsland, S.; et al. Habituation revisited: An updated and revised description of the behavioral characteristics of habituation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2009, 92, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Martin, D.; Hanrahan, B.V.; O’Neill, J. Turk-life in India. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work, Sanibel Island, FL, USA, 9–12 November 2014; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boas, T.C.; Christenson, D.P.; Glick, D.M. Recruiting large online samples in the United States and India: Facebook, Mechanical Turk, and Qualtrics. Political Sci. Res. Methods 2020, 8, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.; Clifford, S.; Burleigh, T.; Waggoner, P.D.; Jewell, R.; Winter, N.J. The shape of and solutions to the MTurk quality crisis. Political Sci. Res. Methods 2020, 8, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyton, K.; Huber, G.A.; Coppock, A. The generalizability of online experiments conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Exp. Political Sci. 2022, 9, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).