Abstract

The transformation of vocational education and training (VET) systems has become a strategic priority for achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in the context of accelerating global economic transitions. This article examines how EU member states modify their VET systems to address evolving labor market demands and align with the objectives of SDGs 4, 8, and 10, utilizing system alignment, decentralization, infrastructure development, stakeholder engagement, and investment in green and digital skills. The article analyzed the influence of these five strategies. Using cross-national comparative analysis and multidimensional indicators, the study reveals that strong partnerships with labor market stakeholders and investments in green and digital transitions significantly enhance the responsiveness and sustainability of VET systems. However, assumptions related to the decentralization of governance and infrastructure expansion were not consistently supported, indicating the need for a more nuanced approach to policy reform. The findings offer practical implications for VET policy design, emphasizing flexibility, system coherence, and future-oriented planning. This study contributes to the growing body of research that links education systems to sustainable economic development. The research also concludes that innovative management models—combining flexible governance, labor-market intelligence, and digital innovation—are central to modernizing VET and improving its adaptability to future skill needs.

1. Introduction

Global economic trends are undergoing profound transformations, shaped by rapid technological innovation, the green transition, and demographic shifts. These changes are redefining the demand for skills, creating both new opportunities and significant risks for labor markets worldwide. Against this evolving backdrop, vocational education and training (VET) systems require substantial redesign to remain relevant and adaptable.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a conceptual framework for positioning VET within the broader sustainable development agenda. In particular, SDG 4 (Quality Education) emphasizes the need to ensure inclusive, equitable, and lifelong learning opportunities for all, highlighting the responsibility of VET to provide flexible pathways that connect general education with the acquisition of professional skills. SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) underscores the role of VET in equipping individuals with labor-market-oriented skills that drive productivity, innovation, and transitions to formal and decent employment. At the same time, SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) highlights the potential of VET to promote social inclusion by expanding access to education and employment opportunities for vulnerable groups, including young people, women, migrants, and residents of rural or economically disadvantaged areas.

Current evidence suggests that the effectiveness of VET systems strongly correlates with labor market outcomes. Moreover, VET’s adaptability to digitalization and ecological transition is increasingly shaping national and regional competitiveness. The European Commission (2022, 2025) [1,2] and recent scholarship (Bieszk-Stolorz & Dmytrów, 2023) [3] emphasize that VET must continue to evolve from traditional models toward more sustainable, innovation-driven, and socially inclusive systems, aligned with global development objectives and responsive to structural shifts in the labor market.

The Education and Training Monitor (2024) [4] reports that over 64% of medium-level VET graduates in the EU engage in work-based learning, enhancing employability. Studies in Malaysia (Sethi et al., 2023) [5] and Africa (ILO & AfDB, 2023) [6] confirm that demand-responsive VET supports structural transformation and inclusive growth. Evidence shows that countries with consolidated VET systems (e.g., Germany, Austria) achieve higher productivity and lower youth unemployment, confirming the link between VET, economic growth, and innovation. OECD studies (OECD, 2024) [7] show that these systems help reduce skills mismatches and improve workforce readiness. Hanushek et al. (2017) [8] also emphasize that VET enhances initial labor market entry and short-term earnings but must evolve to support lifelong adaptability in dynamic economies. The World Bank (2019) [9] and ILO (2020) [10] report that integrating VET into national development strategies contributes to more inclusive and equitable growth, directly supporting SDG 4 and 8 targets.

Inclusion, equity, and gender remain central global challenges. UNESCO (2022) [11] and Hilal (2022) [12] highlight the need for inclusive and gender-responsive VET to ensure equitable participation for women, migrants, and disadvantaged groups in EU policy initiatives.

Future-oriented VET must respond to automation, digitalization, and green economy demands. Lee and Hong (2025) [13], Persson et al. [14] apply advanced data analysis to demonstrate that VET programs aligned with Industry 4.0 skills have a greater influence on employment outcomes. Key evidence indicates that VET programs aligned with Industry 4.0 and digital skills have stronger employment effects, while micro-credentials and flexible learning enhance resilience.

Despite progress, VET faces persistent challenges: social stigma, underfunding, misalignment with labor market needs, and weak private sector engagement in curricula. Cedefop (2020) [15] reports that many EU countries struggle to align VET provision with rapidly evolving skill demands, particularly in the green and digital sectors. Greinert (2005) [16] also noted the institutional rigidity of VET systems, which often hinders swift adaptation to new economic imperatives. Additionally, UNESCO (2020) [17] highlights weak private sector engagement in curriculum design and insufficient teacher training as major barriers to VET relevance and effectiveness.

Overall, VET is increasingly viewed not only as a pathway to labor market development and economic growth, but also as a structural policy instrument for addressing inequalities and regional disparities. At the same time, EU countries are shaping their own models of VET development aimed at specific objectives:

- Strengthening youth employment through dual training. Evidence shows that Germany’s dual system, combining classroom instruction with paid apprenticeships, is highly effective in easing school-to-work transitions. In 2022, Germany had one of the lowest youth unemployment rates in the EU (7.6% vs. 13.1% EU average), with strong employer involvement supporting long-term employability and productivity (Cedefop, 2020) [18], (OECD, 2024) [7];

- Apprenticeship expansion and economic inclusion. Austria and Switzerland illustrate how inclusive apprenticeship policies can expand access for underrepresented groups, such as migrants and disadvantaged youth. Austria’s targeted VET funding has strengthened social cohesion and youth employment, directly supporting SDGs 4.5 and 8.3 (European Commission, 2021) [19];

- Skills anticipation and lifelong learning for productivity. Finland’s 2018 VET reform introduced individualized learning paths and modular curricula, combined with skills-forecasting tools, to enhance adaptability. These measures improved labor market integration and productivity, aligning with SDGs 4.3 and 8.2 (Cedefop, 2023) [20];

- Digitalization and economic modernization through VET. Estonia has prioritized digital transformation in VET by integrating e-learning platforms, AI-based career guidance, and digital certification. These initiatives prepare the workforce for Industry 4.0, boosting productivity and employability (Musset, 2019 [21], OECD, 2020 [22]);

- Green and digital competence integration in VET. Spain’s 2021–2025 VET Modernisation Plan embeds green and digital skills into curricula and expands micro-credentialing. This approach supports resilience, adaptability, and ecological transition, reinforcing SDG 8.4 (Jiménez et al., 2022) [23];

- work-based learning and upskilling strategies. The Netherlands emphasizes flexible learning and competency-based assessment in its “MBO” system, fostering continuous upskilling and regional labor market partnerships. These measures correlate with high employment rates of VET graduates and stronger workforce productivity, advancing SDGs 8.5, 8.6, and 10.3 (Cedefop, 2023) [24].

Aim of the Study

This article examines how VET in EU countries is transforming to support the SDGs and how these changes affect jobs, self-employment, and youth employability amid today’s global economic challenges.

The following hypotheses were tested in the course of the study:

H1.

The development of VET in EU countries plays a significant role in increasing the number of employed and self-employed individuals.

H2.

Graduates of vocational education have higher employment rates and lower unemployment levels compared to youths without vocational qualifications.

H3.

VET systems in EU countries are undergoing active transformation to adapt to the demands of modern labor market amid global economic challenges.

H4.

The transformation of VET in the EU contributes to the achievement of SDG 8—Decent Work and Economic Growth.

H5.

The implementation of innovative management models in VET, emphasizing flexibility, digitalization, and employer collaboration, enhances the effectiveness of vocational education systems in ensuring sustainable employment outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological foundation of this study is based on a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative statistical analysis and qualitative assessment of transformational processes in the field of VET across EU countries. This comprehensive approach enables an in-depth evaluation of the impact of VET on achieving the SDGs, providing a basis for testing the five formulated hypotheses (H1–H5).

1. Quantitative Analysis

To test hypotheses H1 and H2, the study utilizes statistical data from open-access international and national sources, including Eurostat, OECD, Cedefop, ILO, World Bank, reports by the European Commission on VET and labor market performance, and ISCED data (levels ED 35 and ED 45) for VET coverage across EU countries.

Key indicators include

- Employment and self-employment rates by education level (especially ISCED 3–4);

- Share of youth not in employment, education, or training (NEET);

- Youth unemployment rate (ages 15–24);

- Growth dynamics in VET enrolment and graduation rates;

- Employment rates of VET graduates within three years post-graduation;

- Level of digital skills and adult participation in lifelong learning.

The analytical methods used: comparative analysis of EU countries with diverse VET models (e.g., dual systems); correlation analysis between VET coverage and employment outcomes; graphical and time-series analysis of trends (2005–2024).

2. Qualitative Analysis

To assess hypotheses H3, H4, and H5, the study includes a structured analysis of policy, academic, and strategic documents, with particular attention paid to: national VET transformation strategies (e.g., Germany, Austria, Spain, Estonia, Finland, the Netherlands); implementation of digitalization, green competencies, soft skills, and STEM education; changes in the structure of vocational education fields based on 2015–2022 data.

Key transformation aspects examined

- Adoption of dual education models;

- Digital platforms and online learning formats;

- Integration of green skills and emerging professions;

- Adult learning participation rates;

- International mobility and institutional partnerships in VET.

3. Synthesis and Hypothesis Testing

All five hypotheses (H1–H5) are tested through the triangulation of quantitative indicators and qualitative findings. The integrated analysis offers a comprehensive view of VET system effectiveness in achieving the SDGs and identifies key best practices and challenges. Special emphasis is placed on the experiences of countries with advanced VET systems and on identifying future-oriented development trajectories.

3. Results

In 2015, the United Nations developed the SDGs, which represent a global action plan until 2030 aimed at ending poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring well-being for all.

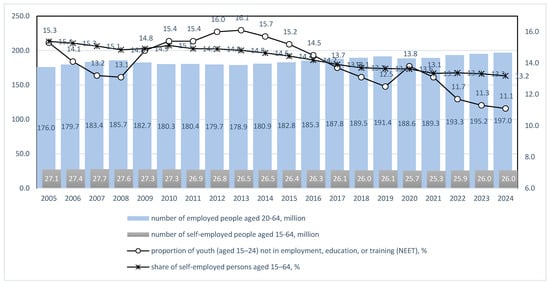

A dynamic analysis of key indicators characterizing employment across 27 EU countries over the past twenty years allows us to draw the following conclusions. Between 2005 and 2024, the number of employed persons aged 20–64 in the EU increased from 176 million to 197 million (+12%), aligning with overall population growth from 434.6 million in 2005 to a projected 450.4 million in 2025 (+3.6%). At the same time, the share of self-employed people among the working-age population declined from 15.3% to 13.2%, despite relatively stable absolute numbers, reflecting labor market changes, such as the expansion of wage employment, tighter business regulations, and the decline of traditional sectors like agriculture. The proportion of NEET youth (aged 15–24) dropped significantly from over 16% in 2013 to 11.1% in 2024, largely due to targeted EU policies in vocational education, youth employment initiatives, and improved access to training (Calculated based on the data: [25]). These dynamics indicate a gradual shift toward more inclusive, formalized, and skills-oriented labor market structures, which supports the achievement of SDG indicators (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dynamics of Employment Indicators in the EU-27 *. * Calculated based on the data of [26].

Within the framework of attaining SDGs 4, 8 and 10, VET is expected to play a pivotal role in equipping a skilled and productive workforce. Such efforts are instrumental in mitigating unemployment rates, particularly among young people, while fostering inclusive and sustainable economic growth through the advancement of competencies that align with labor market requirements. A more detailed account of the potential contribution of VET to achieving the SDG indicators 4, 8, and 10 is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Anticipated Contribution of VET to the Attainment of SDGs Indicators.

In 2024, the EU market for VET was valued at approximately USD 260 million. It is projected to expand to USD 451.5 million by 2030, reflecting an average annual growth rate of 8.8%. Notably, the EU accounts for approximately one-third of the global VET market, underscoring its pivotal role in shaping skills development systems worldwide. VET in the EU spans multiple levels of education, primarily upper secondary (ISCED 3) and post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED 4), while in some member states, it also encompasses short-cycle tertiary education (ISCED 5):

- Upper secondary vocational education (ISCED 3, ED 35). This level of education follows lower secondary education and is typically undertaken between the ages of 16 and 19. It focuses on practical training for specific occupations. In Germany, such education is delivered through Berufsschule, Fachschule, or duale Ausbildung; in France, through Lycée professionnel, CAP, or BEP; in Italy, through Istituto Professionale; in the Netherlands, through MBO level 3–4; and in Poland, through Technikum or szkoła branżowa II stopnia. The duration varies by country, generally ranging from 2 to 5 years. These programs usually lead to both an upper secondary school diploma and a vocational qualification. In many cases, practical training components are included, such as internships (e.g., in Spain) or in-company training (e.g., in Germany).

- Post-secondary non-tertiary vocational education (ISCED 4, ED 45). This level follows upper secondary vocational education (ISCED 3, ED 35) and is designed to deepen professional qualifications or retrain in a specific field. In France, such education is provided in Brevet de Technicien Supérieur (BTS) programs; in Germany, in Meisterschule or Fachschule; in Austria, in Kolleg institutions; and in Poland, through szkoła policealna.

In many EU countries, VET is a growing part of the education system due to its strong alignment with economic and labor market needs. Therefore, it is essential to evaluate the contribution of vocational education and training to the economic growth of EU countries by testing several hypotheses.

H1.

The development of VET in EU countries plays a significant role in increasing the number of employed and self-employed individuals.

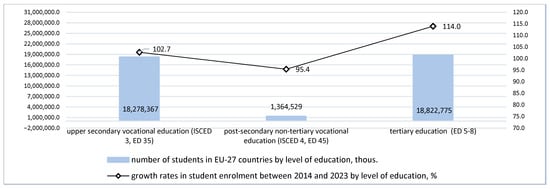

In 2023, the number of students in EU countries enrolled in VET at the levels of upper-secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education amounted to nearly 20 million individuals [27,28]. Within the structure of VET learners, 93% were students acquiring a profession in parallel with completing general upper-secondary education, while only 7% were individuals enhancing their professional qualifications or undergoing retraining.

Despite the promotion of lifelong learning policies across the EU, the number of adults pursuing upskilling or reskilling through vocational programs has remained virtually unchanged over the past decades. The number of students enrolled in higher education is now nearly equal to those engaged in VET (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of students in EU-27 countries by level of education in 2023 and growth rates in student enrolment between 2014 and 2023 *. * Calculated based on the data: [26,27].

This trend reflects both structural and socio-cultural dynamics within educational systems in EU countries. In many member states, academic education is still perceived as a more prestigious and secure pathway to socio-economic advancement, contributing to a steady increase in student numbers at the tertiary level (ISCED 6–8). In contrast, VET, particularly at the upper-secondary level (ISCED 3–4), has experienced stagnation or even a decline in enrolment. For instance, according to Eurostat, in 2022 approximately 38% of upper-secondary students across the EU were enrolled in VET programs, a figure that has remained relatively stable or decreased in several countries over the past decade.

Several underlying factors contribute to this imbalance. These include societal undervaluing of manual and technical professions, limited public awareness of modern VET opportunities, and often inadequate alignment between vocational curricula and the rapidly evolving labor market. Moreover, secondary school systems in many countries remain heavily oriented toward university preparation, thereby discouraging alternative educational trajectories [28].

Nevertheless, there are important exceptions. Countries such as Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands have maintained robust and respected dual education systems, where VET is well integrated with practical work experience and employer engagement. In Germany, for example, around 48% of upper-secondary students are enrolled in dual VET programs, contributing to low youth unemployment and high workforce readiness (Cedefop, 2024) [29]. These examples illustrate that the perceived status and effectiveness of vocational pathways can be significantly enhanced through coordinated public policy, investment in training infrastructure, and sustained collaboration between education providers and industry.

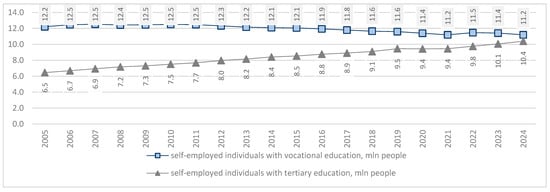

Studies indicate that a proportion of individuals with vocational education pursue self-employment (Figure 3). The technical skills acquired enable them to work in various sectors, including beauty services, construction, crafts, and agriculture. Over the past two decades, the number of self-employed individuals with vocational education has remained relatively stable, whereas the number of self-employed individuals with higher education has increased by more than 1.5 times. Individuals with higher education are more likely to engage in intellectual self-employment, such as IT, consulting, design, and marketing. Therefore, the level of education has a significant impact on the nature of self-employment; however, this impact is not always straightforward and depends on labor market trends, work motivation, and local characteristics.

Figure 3.

Number of self-employed individuals by level of education in EU countries, 2005–2024, million persons *. * Calculated based on the data: [25].

Conclusion to H1 (Table 2): The empirical findings do not fully confirm the hypothesis that the development of VET in EU countries significantly increases the number of employed and self-employed individuals. Furthermore, the number of self-employed individuals with vocational qualifications has remained relatively stable, while self-employment among tertiary-educated individuals has expanded considerably. These results suggest that the impact of VET on employment and self-employment is conditional and strongly influenced by institutional design and labor market dynamics.

Table 2.

Triangulation of Evidence for H1.

H2.

Graduates of vocational education have higher employment rates and lower unemployment levels compared to youth without vocational qualifications.

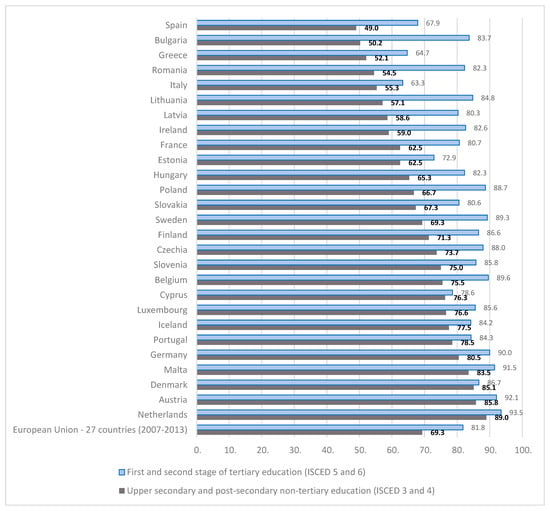

The SDGs are oriented towards increasing youth employment levels, particularly by reducing the proportion of young people who are neither employed, in education, nor acquiring professional skills. A comparative analysis of employment rates within three years after completing formal education indicates that graduates with higher education exhibit higher employment levels compared to those who completed vocational and technical education (81.8% versus 69.3%). In certain Eastern European countries (e.g., Bulgaria and Romania), the lack of strong employer integration means that training in vocational and technical institutions does not necessarily enhance employment opportunities. Furthermore, a persistent bias exists whereby obtaining an academic degree (bachelor’s or master’s) is perceived as more valuable and more conducive to career advancement than vocational qualifications.

Conversely, in countries with a dual vocational education system, the share of employed graduates after completing vocational and technical education is significantly higher, reaching 80.5% in Germany, 85.8% in Austria, and 85.1% in Denmark (Figure 4). Countries with a well-developed dual education system tend to have more competitive economies. Students are provided with practical experience and skills that align with employers’ requirements, enabling graduates of dual education programs to find employment more rapidly.

Figure 4.

Percentage of individuals employed within three years after completing formal education, by education level, EU countries, 2024 *. * Calculated based on the data: [25].

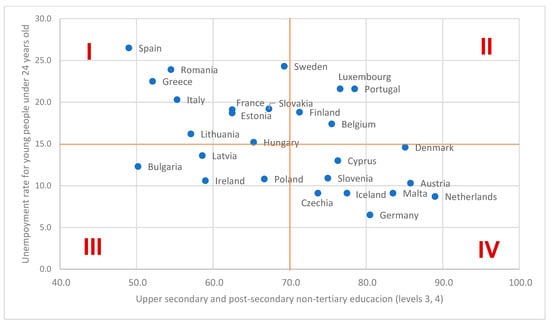

Research also indicates that in countries with well-developed dual education systems, youth unemployment rates (under the age of 24) are significantly lower, as employers are more willing to hire individuals with practical experience or those who have demonstrated their abilities during internships (Quartile IV, Figure 5) [30]. In contrast, the highest youth unemployment rates are observed in countries with a low level of dual education implementation, including Greece, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, and Bulgaria (Quartiles I–II, Figure 5). According to OECD findings, only about 15% of vocational education students in Bulgaria, Latvia, and Lithuania are enrolled in dual education programs, whereas in Italy this share is below one-third [31].

Figure 5.

Relationship between the share of individuals employed within three years after completing upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education and the youth unemployment rate (under 24 years) *. * Calculated based on the data: [25].

Dual education enhances the competitiveness of vocational and technical education graduates in the labor market, as it equips them with skills that can be immediately applied in manufacturing, construction, and technological services.

Conclusion to H2 (Table 3): Hypothesis 2 is only partially supported by analysis. Graduates of vocational education do not consistently demonstrate higher employment rates compared to those with higher education qualifications, as the overall EU average shows lower employment among vocational graduates (69.3%) relative to higher education graduates (81.8%). However, in countries with well-developed dual education systems, such as Germany, Austria, and Denmark, vocational graduates achieve high employment rates (80–86%) and contribute to significantly lower youth unemployment levels. Thus, the impact of vocational education on employment outcomes largely depends on the extent of employer engagement and the quality of dual training systems.

Table 3.

Triangulation of Evidence for H2.

Hypotheses 3–5:

H3.

VET systems in EU countries are undergoing active transformation to adapt to the modern labor market demands amid global economic challenges.

H4.

The transformation of VET in the EU contributes to the achievement of SDG 8—Decent Work and Economic Growth.

H5.

The implementation of innovative management models in VET, emphasizing flexibility, digitalization, and employer collaboration, enhances the effectiveness of vocational education systems in ensuring sustainable employment outcomes.

The modern labor market is being transformed under the influence of global economic development trends such as digitalization and technological integration (services, platforms, logistics, IT, e-commerce), the advancement of the green and circular economy, the substantial predominance of the services sector over manufacturing in the EU, production automation, demographic decline in the EU, increasing labor mobility, and capital flows to countries with cheaper labor that generate a significant share of added value.

Under current conditions in EU countries, financial, educational, and creative services have an increasing influence on economic growth as they generate high value, innovation, and competitive advantages in the global market.

These trends pose challenges for the development of (VET), particularly the need to produce specialists for emerging professions in services, IT, logistics, tourism, healthcare, and other sectors, to develop soft skills and customer orientation, to enhance graduates’ digital competences, to integrate “green” skills into training programs, and to strengthen teamwork and communication skills [32].

Among the key trends in VET, the following should be highlighted:

The shift in vocational education toward service-related fields is not keeping up with labor market demands.

The services sector accounts for approximately 70% of the EU’s economy, while manufacturing accounts for the remaining 30%. In 2022, the share of graduates in service-oriented fields within upper-secondary VET stood at 60.1%, and in post-secondary non-tertiary VET at 67.1%, which is still below labor market needs (Table 4). At the same time, there has been a decline in general education programs and the fields of business, administration and law. Conversely, there has been growth in fields such as health and welfare as well as information and communication technologies (ICT), which are predominantly service-oriented.

Table 4.

Distribution of graduates of upper-secondary VET and post-secondary non-tertiary VET by fields of education *.

VET Systems as Drivers of Europe’s Green Transition. The environmental priorities of the EU require VET to ensure the training of specialists equipped with “green skills”. VET institutions are actively introducing programs in renewable energy and the circular economy. For example, Denmark has established specialized climate-focused vocational institutions: the Rybners Technical School focuses on wind and solar energy; Herningsholm specializes in climate-friendly agriculture and sustainable construction; while the Technical Education Copenhagen offers programs in green transport and logistics. These initiatives are supported by substantial funding for advanced equipment and teacher training. The Netherlands serves as an example of a circular economy-oriented approach, embedding waste reduction and resource efficiency into VET curricula within the framework of its National Circular Economy Program 2023–2030 [33]. At the same time, EU countries face the challenge of a lack of systematic forecasting of emerging occupations and skills required by the green transition.

Lifelong Learning and Continuous Professional Development in the Context of Digital Transformation.

To monitor progress toward SDG 4, which aims to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education at all stages of life—from secondary school to technical, vocational, and higher education—a key indicator is used: the participation of adults in learning within the past four weeks or twelve months.

In countries with high socio-economic development such as Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg, every second employee engages in non-formal education at least once a year. By contrast, the lowest participation rates are observed in Greece (8.8%), Bulgaria (15.9%), and Romania (19.2%) [33]. A high level of engagement in non-formal education offers not only the advantages of remote and flexible learning across age groups but also reflects strong motivation and the capacity to quickly adapt to changing interests or professional demands.

According to statistical data, the share of adults in the EU participating in learning over the past four weeks increased 2.5 times between 2002 and 2024, rising from 5.3% to 13.5%.

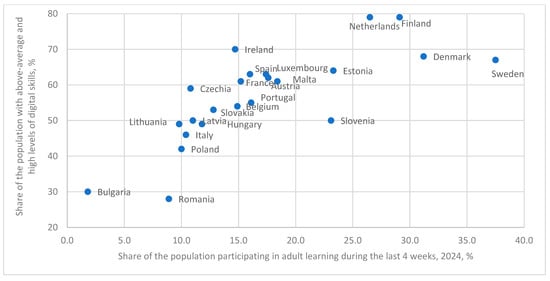

Studies have demonstrated that adult learning participation is not correlated with GDP per capita but rather shows a strong relationship with the level of digitalization. In countries with the highest levels of lifelong learning—such as Sweden (37.5%), the Netherlands (26.5%), Finland (29.1%), Denmark (31.2%), and Estonia (23.3%)—the population also exhibits the highest and above-average digital skills, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The relationship between the development of digital skills and lifelong learning participation among adults in EU countries *. * Calculated based on the data: [34].

The VET sector is undergoing a process of digital transformation, which requires new skills from both learners and instructors, while simultaneously enabling new modes of educational delivery. The role of online education is increasing, offering greater flexibility and necessitating digital competencies. Both online and offline education formats have distinct advantages. Online learning provides access to education for individuals who are employed, have family responsibilities, or live in remote areas. However, in-person instruction still remains essential for certain vocational skills such as welding, electrical installation, carpentry, and other manual trades. These areas require the physical presence of learners, access to modern vocational training centers, and opportunities for workplace-based learning.

A competitive dynamic has emerged between traditional vocational education systems and individualized learning facilitated through online course platforms. At present, a considerable number of companies and online platforms deliver technical training services. Notably, platforms such as Coursera for Business and Udemy for Business provide training for professionals across diverse industrial sectors. Similarly, Mind Tools for Business and FutureLearn focus on enhancing accessibility to education by offering short-format courses, mobile learning solutions, and employer-sponsored training programs. Moreover, Absorb LMS, EdX, and Simplilearn are engaged in pilot implementations of tools aimed at advancing skill development through personalized learning pathways [35]. This competition is prompting traditional institutions to adopt digital technologies, update curricula, and embrace flexible learning formats to remain relevant in the evolving labor market.

The dynamics of scientific advancement and emerging technologies will accelerate the transformation of online learning platforms, enabling them to deliver new courses tailored to the evolving needs of the economy and labor market. Simultaneously, as digital platforms, automation, and artificial intelligence become increasingly integrated into industrial processes, demand will rise for workers capable of maintaining, managing, and servicing these systems. Vocational education specializing in these emerging sectors will appeal to a broader demographic, including technically trained youth and mid-career professionals seeking upward mobility.

Furthermore, the application of virtual reality and simulation tools in training will enhance the learning process, making it more interactive and effective while increasing learner engagement and improving outcomes. Another defining feature of the future global vocational education and training market is the growing emphasis on personalization and accessibility. Online platforms, virtual simulations, and interactive modules will play an increasingly significant role in how learners acquire new skills. These developments will enable individuals to learn at their own pace from virtually any location. The integration of offline and online learning modalities will expand opportunities for a greater number of people to succeed in professions that previously required physical attendance [34].

Online platforms and emerging technologies are expanding access to learning while fostering innovation in teaching methods and curriculum design. At the same time, traditional hands-on training remains critical for many vocational fields, highlighting the importance of blended approaches. As a result, vocational education systems that successfully integrate digital technologies, adapt to rapidly changing skill requirements, and provide flexible, accessible learning opportunities will be best positioned to meet the needs of future economies and societies.

The Growing Demand for STEM Education Specialists in the EU. The rapidly expanding STEM education sector in the EU is currently unable to meet the increasing demand for professionals with advanced technical skills. The labor market is increasingly seeking specialists capable of implementing innovations, managing new technologies, and addressing complex challenges related to digitalization, green transition, and Industry 4.0. At the core of STEM education is the active application of innovative technologies that empower learners not only to acquire theoretical knowledge but also to create new solutions and technologies, adapting them to rapidly changing economic and societal needs. The integration of advanced simulations, virtual laboratories, and other digital learning tools allows students to gain hands-on experience working with real-world objects in a controlled educational environment. This approach strengthens technical literacy, fosters creative problem-solving, and develops adaptability in fast-evolving information and production systems [35].

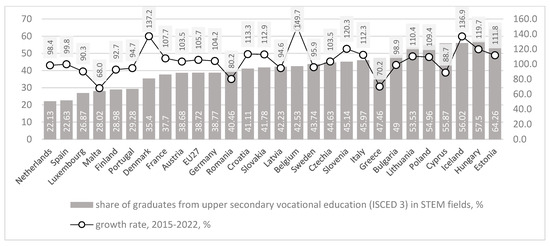

Despite the strategic importance of STEM, Europe faces a shortage of approximately 2 million STEM professionals, and this skills gap continues to grow. In 2022, upper secondary VET graduates (ISCED 3) in STEM fields represented only 38.7% of all graduates across the EU-27. Moreover, the growth rate between 2015 and 2022 reached just 105.7%, far below the level needed to close the workforce gap (Figure 7). The EU target for STEM education by 2030 is 45%, yet current trends indicate that more systemic interventions are necessary [36]. Moreover, disparities are evident both in graduate shares and growth dynamics. While countries such as Estonia (64.2%), Hungary (57.5%), and Poland (54.9%) demonstrate high STEM participation rates, others such as the Netherlands (22.1%), Spain (22.6%), and Luxembourg (26.9%) remain well below average [36].

Figure 7.

Share and growth rate of graduates from upper secondary vocational education (ISCED 3) in STEM fields, % (2015–2022) *. * Calculated based on the data: [36].

Notably, growth rates between 2015 and 2022 vary significantly. Belgium, Iceland, and Denmark exhibit remarkable increases, with growth rates exceeding 130%, signaling strategic investments in STEM-focused vocational training. In contrast, some high-income nations like Sweden (95.9%), the Netherlands (98.4%), and Finland (92.7%) report stagnating or declining growth rates, raising concerns over future talent shortages. As a result, Europe’s capacity to generate a highly skilled workforce is under significant strain, threatening its ability to maintain technological leadership and innovation-driven growth.

In response to these challenges, the EU has intensified efforts to strengthen STEM education as a strategic priority. The new EU Strategic Plan for STEM Education aims to modernize curricula, improve teacher training, promote gender equality, and enhance access to digital learning infrastructure. Special emphasis is placed on linking STEM education with labor market demands, supporting interdisciplinary approaches, and integrating emerging technologies into teaching and learning processes. These policies are expected to help bridge the STEM skills gap, ensure a steady pipeline of qualified professionals, and support Europe’s transition towards a digital, green, and innovation-driven economy.

Enhancing the Role of International Partnerships and Learner Mobility in VET. The growing importance of international partnerships and learner mobility represents both an opportunity and a challenge for VET institutions. Educational mobility fosters the formation of a unified European learning space, simplifying diploma recognition and facilitating cross-border employment. International collaboration provides access to high-quality learning resources and global best practices, increasing the competitiveness and career prospects of VET learners.

A variety of support mechanisms exist, including short-term exchanges, group and blended mobility, and the Erasmus+ program. Erasmus+ (2021–2027) has a budget of approximately €26 billion, enabling annual support for more than 130,000 VET learners and 20,000 instructors [37].

Furthermore, the European Council adopted the European Commission’s recommendation to expand opportunities for young Europeans to study, train, and learn across Europe and beyond, targeting at least 12% of VET learners participating in international mobility programs by 2030 (“Europe on the Move” recommendations).

Currently, this remains a challenge, as participation rates barely exceed 5%. Engagement in international mobility programs requires substantial administrative capacity, including handling documentation, insurance, visa processing, and logistics. Smaller VET institutions often lack the resources to prepare project applications or provide adequate student support during mobility. Additionally, many programs are short-term in nature, which may not be sufficient for acquiring practical skills or adapting to different educational and workplace systems.

Conclusion to H3–H5 (Table 5): The analysis confirms Hypothesis H3, demonstrating that VET systems in EU countries are indeed transforming to address modern labor market demands amid global economic challenges. This process highlights the importance of effective education management, as institutional governance structures are responsible for coordinating digitalization, introducing blended learning models, and aligning curricula with “green” and STEM skills. However, the limited pace and uneven implementation across regions reveal management gaps in strategic planning, coordination with employers, and resource allocation, which slow down the full adaptation of VET to labor market needs.

Table 5.

Triangulation of Evidence for Hypothesis H3–H5.

Hypothesis H4 is also confirmed, since the transformation of VET contributes directly to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). Modernized VET systems increasingly provide skilled labor for sectors such as IT, logistics, healthcare, tourism, and the green economy. Here, management innovations —including cross-border cooperation programs (e.g., Erasmus+, “Europe on the Move”), strategic investment in adult learning, and governance of lifelong learning frameworks—play a decisive role. These managerial instruments ensure equitable access to skills upgrading and reinforce the resilience of labor markets.

Hypothesis H5 is partially confirmed. This shows that digitalization in VET does not guarantee better outcomes on its own; it requires solid governance frameworks to ensure the sustainability of innovation, which connects with dynamic capabilities theory and the literature on inclusive education policies.

The implementation of flexible and digitalized VET models, supported by employer collaboration, has improved training accessibility and facilitated personalized learning pathways. These achievements, however, are highly dependent on institutional management capacity: while some institutions demonstrate effective governance in adopting online courses, VR tools, and simulation-based training, others face resource shortages and weak strategic management. Moreover, insufficient managerial prioritization of STEM and green skills integration delays alignment with labor market demand This shows that digitalization in VET does not guarantee better outcomes on its own; it requires solid governance frameworks to ensure the sustainability of innovation, which connects with dynamic capabilities theory and the literature on inclusive education policies.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study highlight the transformative shifts taking place in VET systems across the EU in response to global economic trends and labor market demands. Our results indicate that the incorporation of green skills and stronger employer collaboration within VET governance frameworks reinforces the connection with SDG 8 on decent work, as also emphasized by García and López (2023) [23]. In line with this, the reforms observed across EU member states promote equitable access to practice-oriented education, expand lifelong learning pathways, and create new opportunities for vulnerable groups. This suggests that VET modernization is not only reducing social and territorial disparities but also strengthening human capital and fostering innovation-driven regional development.

VET reforms foster equitable access to quality and practice-oriented education, strengthen lifelong learning pathways, and expand opportunities for vulnerable groups, thereby reducing social and territorial disparities. This aligns with the view that inclusive and gender-responsive VET frameworks are essential to address inequalities, particularly for women, migrants, and disadvantaged youth (UNESCO, 2022) [17]. Our results confirm that policies targeting vulnerable groups not only improve equity but also enhance the overall adaptability of regional labor markets.

A key theme emerging from the analysis is the increasing demand for adaptive, flexible, and modular learning pathways that allow individuals to transition across sectors and occupations, particularly in the face of digital and green transitions. This finding corresponds to the experience of Austria, where inclusive apprenticeship policies and modular training approaches have strengthened labor market integration and expanded opportunities for disadvantaged groups (Cedefop, 2023) [20]. These examples highlight that innovative management models—including modular curricula, blended learning formats, and stronger foresight methods—serve as crucial governance tools for making VET more adaptable to rapid economic change.

Moreover, the growing role of partnerships—between VET institutions, employers, regional authorities, and civil society—is reinforcing the responsiveness of vocational training to local economic needs. This is consistent with European Commission (2021) [19], which highlights that inclusive apprenticeship policies strengthen youth employment through cooperation between schools and employers in EU countries. Similarly, our results suggest that regionalization of skills development strategies improves the alignment between training outcomes and labor market opportunities.

Ultimately, this study confirms previous findings regarding the need for enhanced governance mechanisms and systemic reforms within VET systems to ensure equity, quality, and sustainability. This suggests that innovative management frameworks—particularly those integrating labor market intelligence, digital tools, and AI-based feedback mechanisms—represent a new paradigm of VET governance (OECD, 2020) [33]. This is particularly relevant in the context of accelerating technological change and ecological pressures, where strategic governance capacity becomes a precondition for sustainable VET reforms.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the role of VET systems in advancing SDGs 4, 8, 10, focusing on how they respond to global economic trends and labor market demands across EU countries. Through comparative analysis and hypothesis testing, the paper aimed to identify structural and institutional drivers that contribute to the effectiveness and adaptability of VET systems.

The findings provide partial support for the proposed hypotheses. Hypothesis H1 was generally confirmed: countries with VET systems better aligned with SDGs objectives show stronger adaptability to labor market changes, particularly in the context of economic recovery and skills mismatch. Similarly, H4 and H5 were supported by the data, confirming that stronger cooperation between VET institutions and employers, along with targeted investments in green and digital skills, enhances employment out-comes and system resilience.

A key conclusion of this research is that innovative management models are central to modernizing VET systems. These models combine flexible governance (modular and competency-based curricula, decentralized partnerships), foresight and labor market intelligence (anticipating skills needs), and digital innovations (AI-based teaching tools, blended learning). By integrating such approaches, VET systems can achieve not only higher employment outcomes but also greater inclusivity and long-term adaptability to global transformations.

An additional innovative direction relates to the integration of artificial intelligence into VET. Recent evidence from engineering education suggests that AI-assisted tools, such as real-time classroom behavior analysis and emotion recognition models (ERAM), can substantially enhance instructional effectiveness by providing immediate feedback and facilitating adaptive teaching strategies (Hu et al., 2024 [38]). For VET systems, this opens opportunities to address emerging challenges such as AI-driven job displacement by equipping learners with technical expertise and adaptability skills. Thus, AI-enhanced management models represent a promising frontier for ensuring the resilience, inclusivity, and global competitiveness of VET reforms.

Although the empirical analysis focused on EU countries, the findings carry broader significance, particularly for non-EU Eastern European states, post-Soviet countries, and Ukraine. These contexts are characterized by similar structural challenges in the development of VET systems, including persistent skills mismatches with labor market demands, misalignment between educational programs and employer requirements, demographic decline, and the pressing need to integrate digitalization and the green transition. Evidence from these countries highlights the importance of adapting VET systems to address such challenges, as this is essential for strengthening competitiveness, fostering employment, and promoting social inclusion. Moreover, comparative examples from Malaysia and African countries further confirm that analogous reforms can promote sustainable growth beyond Europe, thereby reinforcing the global relevance of the study’s findings.

In this way, the research contributes not only to the academic debate but also to practical policy design, offering lessons that can guide reforms in diverse socio-economic contexts. By linking VET with global development objectives, the study underlines the universal role of vocational education as a driver of resilience, innovation, and inclusive growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S. and L.B.; methodology, K.P.; software, I.C.; validation, O.I., I.S. and L.B.; formal analysis, K.P.; investigation, L.B.; resources, I.C.; data curation, O.I.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, O.I.; visualization, I.C.; supervision, I.S.; project administration, O.I.; funding acquisition, O.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- European Commission Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union. Vocational Education and Training: Skills for Today and for the Future. 2022. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/webpub/empl/VET-skills-for-today-and-future/pdf/KE0621179ENN.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- The Union of Skills: Communication From the Commission to The European Parliament, The European Council, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and The Committee of The Regions. Brussels, 5.3.2025 COM(2025) 90 Final. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/union-skills_en (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Bieszk-Stolorz, B.; Dmytrów, K. Decent Work and Economic Growth in EU Countries: Static and Dynamic Analyses of Sustainable Development Goal 8. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union. Education and Training Monitor 2024: Comparative Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/education_and_training_monitor_2024.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Sethi, A.; Jangir, K.; Toshniwal, R.; Vaidya, R. Role of Vocational Training Effectiveness and Employment Outcomes in Sustainable Quality Education. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Sustainable Business Practices-2024 (ICETSBP 2024), Mohali, India, 28–29 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Pathways to Sustainable Growth: Strengthening TVET and Productive Sector Linkages in Africa; International Labour Office and African Development Bank: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40africa/%40ro-abidjan/%40sro-cairo/documents/publication/wcms_881406.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Challenging Social Inequality Through Career Guidance. Insights from International Data and Practice; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/02/challenging-social-inequality-through-career-guidance_be87ce97/619667e2-en.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Hanushek, E.A.; Woessmann, L.; Schwerdt, G.; Zhang, L. General Education, Vocational Education, and Labor-Market Outcomes over the Life-Cycle. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 52, 48–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Changing Nature of Work: World Development Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/816281518818814423/pdf/2019-WDR-Report.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Skills Policies for Resilience; OECD; Cedefop; European Commission; ETF; ILO; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-issues/adult-skills-and-work/Skills_Policies_for_Resilience.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- UNESCO. Transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth: UNESCO Strategy 2022–2029. 2022. Available online: https://unevoc.unesco.org/pub/unesco_strategy_for_tvet_2022-2029.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Hilal, R. The Invisible Contribution of TVET to SDGs–Palestine Case. Int. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. Res. 2022, 8, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Hong, I. Quantifying the influence of vocational education and training with text embedding and similarity-based networks. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0329405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson Thunqvist, D.; Gustavsson, M.; Halvarsson Lundqvist, A. The role of VET in a green transition of industry: A literature review. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2023, 10, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publications Office of the European Union; Cedefop. Digital Gap During COVID-19 for VET Lerners at Risk in Europe. 2020. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/digital_gap_during_covid-19.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Greinert, W.-D. Mass Vocational Education and Training in Europe: Classical Models of the 19th Century and Training in England, France and Germany During the First Half of the 20th. CEDEFOP Panorama Series, 2005. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/5157_en.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025). CEDEFOP Panorama Series.

- European Training Foundation; UNESCO-UNEVOC. Innovating Technical and Vocational Education and Training: A Framework for Institutions. 2020. Available online: https://unevoc.unesco.org/pub/innovating_tvet_framework.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Vocational Education and Training in Germany: Short Description; Cedefop; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/329932 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document: Putting into Practice the European Framework for Quality and Effective Apprenticeships–Implementation of the Council Recommendation by Member States. Brussels, 13.8.2021 SWD(2021) 230 Final. 2021. Available online: https://irshare.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/EN-final-swd-efqea_1632054923.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Cedefop. Finland: The Government Sets Objectives for Vocational Education and Training. ReferNet Finland. 2023. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/finland-government-sets-objectives-vocational-education-and-training (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Musset, P.; Field, S.; Mann, A.; Bergseng, B. Vocational Education and Training in Estonia, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Publishing. Strengthening the Governance of Skills Systems: Lessons from Six OECD Countries, OECD Skills Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda Jiménez, J.R.; Campos-García, I.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C. Vocational continuing training in Spain: Contribution to the challenge of Industry 4.0 and structural unemployment. Intang. Cap. 2022, 18, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop. The Future of Vocational Education and Training in Europe: Synthesis Report. Cedefop Reference Series; No 125; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/08824 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Students Enrolled in Tertiary Education by Education Level, Programme Orientation, Sex, Type of Institution and Intensity of Participation. Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/educ_uoe_enrt01/default/table?lang=en&category=educ.educ_part.educ_uoe_enr.educ_uoe_enrt (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Eurostat. Students Enrolled in Upper Secondary Education by Programme Orientation and Sex. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/educ_uoe_enrs05/default/table?lang=en&category=educ.educ_part.educ_uoe_enr.educ_uoe_enrs (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedefop. Vocational Education and Training Policy Briefs 2023–Germany. Cedefop Monitoring and Analysis of Vocational Education and Training Policies. 2024. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/035346 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Huismann, A.; Hippach-Schneider, U. Vocational Education and Training in Europe–Germany: System Description. In Vocational Education and Training in Europe: VET; Cedefop, & ReferNet: Hove, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384684803_Vocational_Education_and_Training_in_Europe_-_system_description_Germany_2023 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Education Policy Outlook in Greece. OECD Education Policy Perspectives, No17. 2020. Available online: www.oecd.org/en/publications/education-policy-outlook-in-greece_f10b95cf-en.html (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Liu, H.; Paramalingam, M. Aligning Vocational Education with Emerging Industry Trend. J. Neonatal Surg. 2025, 14, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczera, M. Vocational Education and Training (VET) and the Green Transition: Insights from Labour Market DATA; Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 327; OECD: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). 2022. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2022 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Klingberg, L. EU Looks to Plug STEM Skills Gap. Science|Business 2025. Available online: https://sciencebusiness.net/news/careers/eu-looks-plug-stem-skills-gap (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Key Indicators on VET. Cedefop. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/key-indicators-on-vet/indicators?year=recent#89 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- European Commission. Vocational Education and Training Initiatives. 2023. Available online: https://education.ec.europa.eu/ru/education-levels/vocational-education-and-training/about-vocational-education-and-training?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Hu, J.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Zou, Y. Real-Time Classroom Behavior Analysis for Enhanced Engineering Education: An AI-Assisted Approach. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).