Carbon Footprint Accounting and Emission Hotspot Identification in an Industrial Plastic Injection Molding Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. System Boundaries

3.2. Categories of Emission Sources

- A.

- Category 1: Direct GHG Emissions

- B.

- Category 2: Indirect GHG Emissions from Imported Energy

- C.

- Category 3: Indirect GHG Emissions from Transportation

- D.

- Category 4: Indirect GHG Emissions from Products Used by the Organization

- E.

- Category 5: Emissions and Removals from Product Use

- F.

- Category 6: Indirect GHG Emissions from Other Sources

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Emission Calculation Methodology

3.5. Uncertainty and Materiality Assessment—Bayesian Monte Carlo Approach

3.5.1. Notation and Basic Emissions Model

3.5.2. Likelihood Measurement Model

3.5.3. Prior Distributions

3.5.4. Emission Factors (EFs)

3.5.5. Posterior and Bayesian Monte Carlo Sampling

- 1.

- ∼ p(As|YA,s)

- 2.

- ∼ p(EFs,g |Y EFs,g )

- 3.

- ∼ p(ℓs|data ), = capacitys

- 4.

- = GWPg

- 5.

- =

3.6. Calculation Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings

6.2. Limitations

6.3. Future Research

6.4. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report; The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- DEFRA. UK Government GHG Conversion Factors for Company Reporting; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2023. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6846a4f55e92539572806125/ghg-conversion-factors-2025-full-set.xlsx (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- EPA. Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990–2022; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://pasteur.epa.gov/uploads/10.23719/1531143/SupplyChainGHGEmissionFactors_v1.3.0_NAICS_CO2e_USD2022.csv (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- NASA. Global Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://science.nasa.gov/earth/explore/earth-indicators/carbon-dioxide/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- WMO. State of the Global Climate 2023; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://wmo.int/publication-series/state-of-global-climate-2023 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- WHO. Climate Change and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- UNHCR. Climate Change and Displacement; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/what-we-do/build-better-futures/climate-change-and-displacement (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- OECD. Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries in 2013; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2020/11/climate-finance-provided-and-mobilised-by-developed-countries-in-2013-18_5523fb48/f0773d55-en.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2021/2022; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2021-22reportenglish_0.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- ISO 14064-1:2019; Greenhouse Gases—Part 1: Specification with Guidance at the Organization Level for Quantification and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:14064:-1:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- UNEP. Emissions Gap Report 2022; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2022 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Bakker, D.C.E.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Luijkx, I.T.; Peters, G.P.; et al. Global carbon budget 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 5301–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Bustamante, M.; Ahammad, H.; Clark, H.; Dong, H.; Elsiddig, E.A.; Haberl, H.; Harper, R.; House, J.; Jafari, M.; et al. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marsland, R.; Staples, J. Time for a Focus on Climate Change and Health. Med. Anthropol. 2024, 43, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.; Sato, M.; Hearty, P.; Ruedy, R.; Kelley, M.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Russell, G.; Tselioudis, G.; Cao, J.; Rignot, E.; et al. Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: Evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming could be dangerous. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 3761–3812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecequet, M.; DeWaard, J.; Hellmann, J.J.; Abel, G.J. Climate Vulnerability and Human Migration in Global Perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavari, A.; Mirza, I.B.; Bagha, H.; Korala, H.; Dia, H.; Scifleet, P.; Sargent, J.; Tjung, C.; Shafiei, M. ArtEMon: Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Powered Greenhouse Gas Sensing for Real-Time Emissions Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Jasni, N.S.; Ismail, R.F. Current trends in carbon emission trading: Theoretical perspectives, research methods and emerging themes. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2024, 8, 1658–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, S.P. The economics of carbon dioxide capture and storage technologies. Thermal Eng. 2022, 69, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, A.; Akbari, M. Potential of solar energy in developing countries for reducing energy-related emissions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, G.; Gupta, A.; Mulder, I.; Unterstell, N. Climate Financing Needs in the Land Sector under the Paris Agreement: An Assessment of Developing Country Perspectives. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Kimball, L.A.; Scanlon, J. Global governance for the environment and the role of multilateral environmental agreements in conservation. Oryx 2003, 37, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filonchyk, M.; Peterson, M.P.; Zhang, L.; Hurynovich, V.; He, Y. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Global Climate Change: Examining the Influence of CO2, CH4, and N2O. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 173359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabric, A.J. The climate change crisis: A review of its causes and possible responses. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Awada, T.; Zhang, Y.; Paustian, K. Global Land Use Change and Its Impact on Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.R.; Singh, O. Study of impacts of global warming on climate change: Rise in sea level and disaster frequency. In Global Warming—Impacts and Future Perspective; Singh, B.R., Ed.; InTech Publishing: London, UK, 2012; pp. 94–118. ISBN 978-953-51-0755-2. [Google Scholar]

- Romanello, M.; Di Napoli, C.; Drummond, P.; Green, C.; Kennard, H.; Lampard, P.; Scamman, D.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Ford, L.B.; et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 2022, 400, 1619–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onoh, U.C.; Ogunade, J.; Owoeye, E.; Awakessien, S.; Asomah, J.K. Impact of climate change on biodiversity and ecosystems services. IIARD Int. J. Geogr. Environ. Manag. 2024, 10, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Aryal, J.P.; Rahut, D.B.; Marenya, P. Climate risks, adaptation and vulnerability in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In Climate Vulnerability and Resilience in the Global South: Human Adaptations for Sustainable Futures; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrani, A.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Madramootoo, C.A. Machine learning for predicting greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahman, N.; Al-Khalifa, M.; Al Baharna, S.; Abdulmohsen, Z.; Khan, E. Review of Carbon Capture and Storage Technologies in Selected Industries: Potentials and Challenges. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 22, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hait, M.; Chaturwedi, A.K.; Mitra, J.C.; Verma, R.; Kashyap, N.K. Emerging Technologies for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. In Evaluating Environmental Processes and Technologies: Environmental Science and Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 385–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, K.; Patwa, N.; Gupta, Y. Breaking Barriers in Deployment of Renewable Energy. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, F. Carbon capture and storage as a corporate technology strategy challenge. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 2256–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdzik, B.; Wolniak, R.; Nagaj, R.; Grebski, W.W.; Romanyshyn, T. Barriers to renewable energy source (RES) installations as determinants of energy consumption in EU countries. Energies 2023, 16, 7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Strezov, V. Effect of foreign direct investments, economic development and energy consumption on greenhouse gas emissions in developing countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.I.D.; Brito, L.M.; Nunes, L.J.R. Soil Carbon Sequestration in the Context of Climate Change Mitigation: A Review. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Thomas, S.C.; Tian, D. Forest management and soil respiration: Implications for carbon sequestration. Environ. Rev. 2008, 16, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Sixth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement Status Report; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Bonn, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Liu, H.; Xie, L.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, Q. A Real-Time Accounting Method for Carbon Dioxide Emissions in High-Energy-Consuming Industrial Parks. Processes 2024, 12, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, Y.X.; Chew, Y.E.; Foo, D.C.; How, B.S.; Andiappan, V. Carbon emission reduction strategy planning and scheduling for transitioning process plants towards net-zero emissions. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa Zadeh, S.B.; López Gutiérrez, J.S.; Esteban, M.D.; Fernández-Sánchez, G.; Garay-Rondero, C.L. A Framework for Accurate Carbon Footprint Calculation in Seaports: Methodology Proposal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GHG Protocol. Greenhouse Gas Protocol—Official Website. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/ (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. Turkey Electricity Generation and Electricity Consumption Point Emission Factors Information Sheet; Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources: Ankara, Türkiye, 2022. Available online: https://enerji.gov.tr/Media/Dizin/EVCED/tr/%C3%87evreVe%C4%B0klim/%C4%B0klimDe%C4%9Fi%C5%9Fikli%C4%9Fi/UlusalSeraGaz%C4%B1EmisyonEnvanteri/Belgeler/Ek-1.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

| GHG | 100-Year GWP (Global Warming Potential) |

|---|---|

| Carbon Dioxide (CO2) | 1.00 |

| Methane (CH4) | 27.90 |

| Nitrous Oxide (N2O) | 273.00 |

| R22 | 1960 |

| R32 | 771 |

| R410 A | 2255.5 |

| R600 A | 0.006 |

| Source Flow | CO2e Calculation Method | EF CO2 (kg/TJ) | EF CH4 (kg/TJ) | EF N2O (kg/TJ) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel Fuel | GHG Emission = Fuel Consumption (tons/year) × Density (845 kg/m3) × NCV (43 TJ/Gg) × EF (kg/TJ) | 74.100 | 3 | 0.6 | [1] |

| On-Road Diesel | GHG Emission = Fuel Consumption (tons/year) × Density (845 kg/m3) × NCV (43 TJ/Gg) × EF (kg/TJ) | 74.100 | 3.90 | 3.9 | [1] |

| GHG Emission Source | CO2e Calculation Method | References |

|---|---|---|

| Refrigerators | If Refilling Has Been Done: GHG Emission = Gas Charged (kg) × GWP If Refilling Has Not Been Done: GHG Emission = Equipment Gas Capacity × Leakage Rate (0.1%) × GWP | [1] |

| Air Conditioners, Fire Extinguishers | If Refilling Has Been Done: GHG Emission = Gas Charged (kg) × GWP If Refilling Has Not Been Done: GHG Emission = Equipment Gas Capacity × Leakage Rate (1% for air conditioners, 4% for fire extinguishers) × GWP |

| GHG Emission Source | CO2e Calculation Method | EF CO2 (ton/Wh) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Activity Data (MWh) Emission Factor | 0.439 | [46] |

| GHG Emission Source | CO2e Calculation Method | EF | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Road Transportation | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 1.115 kg CO2e/USD | [3] |

| Air Transportation | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.976 CO2e/USD | |

| Maritime Transportation | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.618 CO2e/USD | |

| Domestic Flight | GHG Emission = Activity Data (passenger.km) × EF | 0.18287kg CO2e/passenger.km | [41] |

| International Flight | GHG Emission = Activity Data (passenger.km) × EF | 0.20011 kg CO2e/passenger.km | |

| Hotel Accommodations | GHG Emission = Activity Data (overnight stay) × EF | 32.1kg CO2e/overnight stay |

| GHG Emission Source | CO2e Calculation Method | EF | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Water | GHG Emission = Activity Data (m3) × EF | 0.15311 kg CO2e/m3 | [2,3] |

| Primary Steel | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.549 kg CO2e/USD | |

| Aluminum | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 1.41 kg CO2e/USD | |

| Aluminum Products | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.869 kg CO2e/USD | |

| Screws, Nuts, and Bolts | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.332 kg CO2/USD | |

| Ball and Roller Bearings | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.277 kg CO2e/USD | |

| Cleaning | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.405 kg CO2e/USD | |

| Household Waste | GHG Emission = Activity Data (tonne) × EF | 497.04416 kg CO2e/tonne | [2] |

| Wastewater | GHG Emission = Activity Data (m3) × EF | 0.18574 kg CO2e/m3 | |

| Certification | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.079 kg CO2e/USD | [3] |

| Accounting | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.05 kg CO2e/USD | |

| Management Consulting | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.084 kg CO2e/USD | |

| R&D (Research and Development) | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.079 kg CO2e/USD | |

| Software | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.097 kg CO2e/USD | |

| 5S | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.084 kg CO2e/USD | |

| Catering/Meals/Food Service | GHG Emission = Activity Data (USD) × EF | 0.155 kg CO2e/USD |

| Emission Source | Category | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Generator (diesel) | 1 | Electricity generation |

| Refrigerant gas leaks (refrigerator) | 1 | Cooling systems—office coolers and refrigerators |

| Refrigerant gas (air conditioner filling) | 1 | Cooling systems—office coolers |

| Fire extinguisher leaks | 1 | Fire extinguishers |

| Diesel—vehicles | 1 | Fuel consumption of on-road/off-road vehicles |

| Electricity | 2 | Building operating systems—combustion for heating, cooling, and lighting |

| Emissions from transportation or distribution of incoming goods | 3 | Road transportation |

| Emissions from transportation of outgoing goods | 3 | Road/air/sea transportation |

| Diesel | 3 | Combustion emissions for personnel transport |

| Travel and accommodation data | 3 | Emissions from customer and visitor transportation |

| Travel and accommodation data | 3 | Emissions from business travel |

| Purchased products | 4 | Emissions from raw materials/products/semi-products related to manufacturing |

| Solid and liquid waste transportation | 4 | Emissions from disposal of solid and liquid waste |

| Consultancy | 4 | Emissions from consultancy service procurement |

| Emissions and removals from product use | 5 | Emissions/removals from sold products and solar power systems (SPP) |

| Indirect GHG emissions from other sources | 6 | WTT (Well-To-Tank), electricity distribution |

| Data Acquisition Method | Emission Factor Acquisition Method | Uncertainty Value (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Device Subject to Legal Metrological Control | IPCC | 1.5 |

| Measurement Device with Valid Calibration Date | Internationally Recognized Data | 1.5 |

| Measurement Device with Expired/No Calibration | National Inventories of Countries | 2.5 |

| Labeled Supplier Data (e.g., Gas Filling Capacity) | Labeled Supplier Data (e.g., MSDS) | 3.5 |

| Supplier Data | Supplier Data | 5 |

| Distance Measurement Programs (e.g., Google Maps) | Assumption | 7 |

| Unclear and Inaccessible Data (Excluded Data) | Supplier Data and Unavailable Data | 10 |

| Uncertainty Assessment by Category | |

|---|---|

| Sub-Category | Uncertainty Value |

| 1 | 4.68% |

| 2 | 4.30% |

| 3 | 2.88% |

| 4 | 2.95% |

| 5 | 3.81% |

| 6 | 1.73% |

| Uncertainty Assessment by Sub-Category | |

| Sub-Category | Uncertainty Value |

| 1.1 | 3.81% |

| 1.2 | 3.81% |

| 1.4 | 4.83% |

| 2.1 | 4.30% |

| 3.1 | 3.81% |

| 3.2 | 2.64% |

| 3.3 | 5.22% |

| 3.4 | 3.08% |

| 3.5 | 2.58% |

| 4.1 | 3.00% |

| 4.3 | 6.94% |

| 4.5 | 3.81% |

| 5.3 | 1.73% |

| 6.1 | |

| Cumulative Uncertainty Total | |

| 2.16% | |

| Category | Emission Description | Significance Level |

|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | Emissions from inbound transportation or distribution of goods to the organization. | Not Significant |

| 3.2 | Emissions from outbound transportation of goods from the organization. | Not Significant |

| 3.3 | GHG emissions from employee commuting. | Not Significant |

| 3.4 | GHG emissions from customer and visitor transportation. | Not Significant |

| 3.5 | GHG emissions from business travel. | Not Significant |

| 4.1 | GHG emissions from purchased raw materials, intermediate goods, or finished goods related to product manufacturing. | Significant |

| 4.3 | GHG emissions from disposal of solid and liquid waste. | Not Significant |

| 4.5 | Emissions from services such as consulting, cleaning, maintenance, courier, and banking. | Not Significant |

| 5.3 | Emissions from the end-of-life stage of the product. | Significant |

| 6.1 | Emissions and removals from product use. | Not Significant |

| GHG Emissions | Data Type | Total (CO2e) | CO2 | CH4 | N2O | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Category 1: Direct greenhouse gas emissions and removals (CO2e) | 255.33 | 255.22 | 0.01 | 0.09 | |

| 1.1 | Direct GHG emissions from stationary combustion sources | Primary | 1.89 | 1.88 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 1.2 | Direct GHG emissions from mobile combustion sources | Primary | 6.32 | 6.23 | 0.01 | 0.09 |

| 1.4 | Direct GHG emissions from leakage/fugitive emissions of greenhouse gases in anthropogenic systems | Primary | 247.11 | 247.1141 | - | - |

| Indirect GHG Emissions (CO2e) | Data Type | Total (CO2e) | CO2 | CH4 | N2O | |

| 2 | Category 2: Indirect greenhouse gas emissions from imported energy | 450.72 | 450.72 | - | - | |

| 2.1 | Indirect greenhouse gas emissions from imported electricity | Primary | 450.72 | 450.72 | - | - |

| 3 | Category 3: Indirect greenhouse gas emissions from transportation sources | 191.56 | 100.80 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| 3.1 | Emissions from inbound goods transportation or distribution | Primary | 20.50 | - | - | - |

| 3.2 | Emissions from outbound goods transportation | Primary | 29.68 | - | - | - |

| 3.3 | Greenhouse gas emissions from employee commuting | Secondary | 102.40 | 100.80 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 3.4 | Greenhouse gas emissions from customer and visitor transportation | Primary | 17.14 | - | - | - |

| 3.5 | GHG emissions from business travel | Primary | 21.84 | - | - | - |

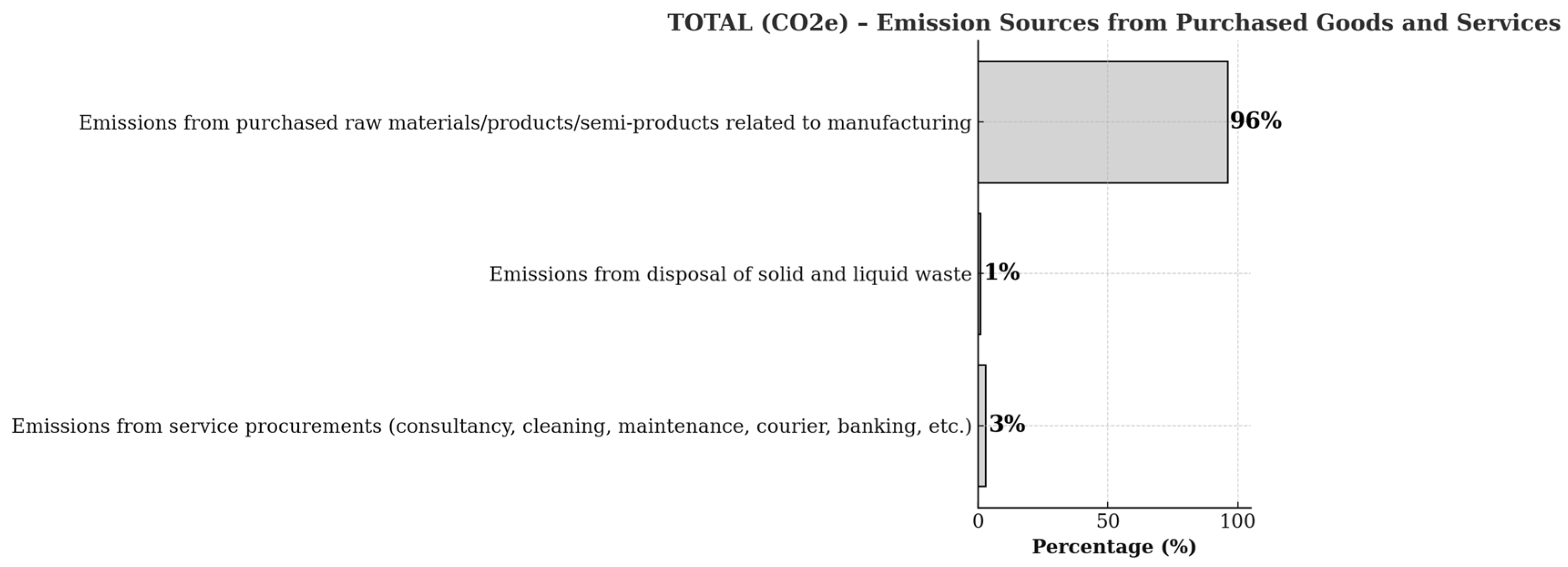

| 4 | Category 4: Indirect greenhouse gas emissions from products used by the organization | Primary | 1031.22 | 1031.22 | - | - |

| 4.1 | GHG emissions from purchased raw materials/finished goods/semi-finished goods, etc., associated with product manufacturing | Primary | 993.54 | 993.54 | - | - |

| 4.3 | GHG emissions from the disposal of solid and liquid waste | Primary | 16.82 | 16.82 | - | - |

| 4.5 | Emissions from purchased services such as consulting, cleaning, maintenance, courier, banking, etc. | Primary | 20.86 | 20.86 | ||

| 5 | Category 5: Indirect GHG emissions from post-production use of products | 1987.49 | 1987.49 | - | - | |

| 5.3 | Emissions from the end-of-life stage of the product | Primary | 1987.49 | 1987.49 | ||

| 6 | Category 6: Indirect GHG emissions from other sources | 6.43 | 6.43 | - | - | |

| 6.1 | Indirect GHG emissions from other sources | Primary | 6.43 | 6.43 | ||

| Total: | 3922.75 | CO2e (Tonne) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ateş, K.T.; Arslan, G.; Demirdelen, Ö.; Yüksel, M. Carbon Footprint Accounting and Emission Hotspot Identification in an Industrial Plastic Injection Molding Process. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219531

Ateş KT, Arslan G, Demirdelen Ö, Yüksel M. Carbon Footprint Accounting and Emission Hotspot Identification in an Industrial Plastic Injection Molding Process. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219531

Chicago/Turabian StyleAteş, Kübra Tümay, Gamze Arslan, Özge Demirdelen, and Mehmet Yüksel. 2025. "Carbon Footprint Accounting and Emission Hotspot Identification in an Industrial Plastic Injection Molding Process" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219531

APA StyleAteş, K. T., Arslan, G., Demirdelen, Ö., & Yüksel, M. (2025). Carbon Footprint Accounting and Emission Hotspot Identification in an Industrial Plastic Injection Molding Process. Sustainability, 17(21), 9531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219531