Abstract

Amid rapid technological change and industrial transformation, digital consumption (DC) has become both a driver of domestic demand and a potential catalyst for corporate innovation. Yet, systematic evidence on how DC shapes innovation behavior remains limited. This study investigates the causal effect of DC on corporate innovation activity (CIA) by exploiting China’s Information Consumption Pilot Policy (ICPP) as a quasi-natural experiment with firm-level panel data from 2008 to 2022. The results show that DC significantly enhances CIA through three mechanisms: strengthening government attention to science and technology talent, advancing the circulation and utilization of regional data, and promoting corporate data assetization. Moreover, the effect is stronger in eastern regions, in areas with greater governmental digital engagement, and among firms with stronger managerial incentives. Further analysis indicates that DC not only increases overall innovation activity but also disproportionately fosters substantive innovation, as reflected in invention patents. These findings provide new empirical evidence on the differentiated role of DC in shaping both the quantity and quality of corporate innovation, offering insights for the design of digital economy policies in developing countries.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of an accelerating new wave of technological revolution and industrial transformation, the global economic landscape is undergoing profound restructuring, with intensifying geopolitical risks and a significant increase in uncertainties within global industrial chains and technology supply chains [1]. In response to the challenges facing macroeconomic development, countries have universally elevated scientific and technological innovation, as well as self-reliance and self-strengthening, with the aim of securing the strategic initiative for development in an unstable external environment. As the core vehicle of technological innovation, enterprises not only undertake the direct tasks of R&D investment, technological breakthroughs, and the commercialization of results, but also serve as critical platforms for the efficient flow and aggregation of innovation factors. Compared to traditional static stock indicators such as R&D investment and patents, corporate innovation vitality (CIA), which is measured through text-based analysis, can more dynamically and comprehensively gauge a firm’s proactiveness and responsiveness in R&D, product iteration, technology application, and business model innovation. It thus serves as a key leading indicator of both a firm’s motivation and its capacity for innovation.

With the continuous maturation of technologies such as big data, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things [2]. Information technology is providing new momentum for economic development [3]. The rapid rise of the digital economy has not only spawned new business forms and models but has also profoundly altered consumption structures and corporate behaviors, emerging as a core driver of high-quality economic development. Among these, digital consumption (DC) serves as a vital component of the digital economy, has become a new engine for stimulating domestic demand and fostering innovation. It is characterized by personalized demand, diversified forms, and shortened market feedback cycles, compelling enterprises to continuously enhance their innovation responsiveness and vitality.

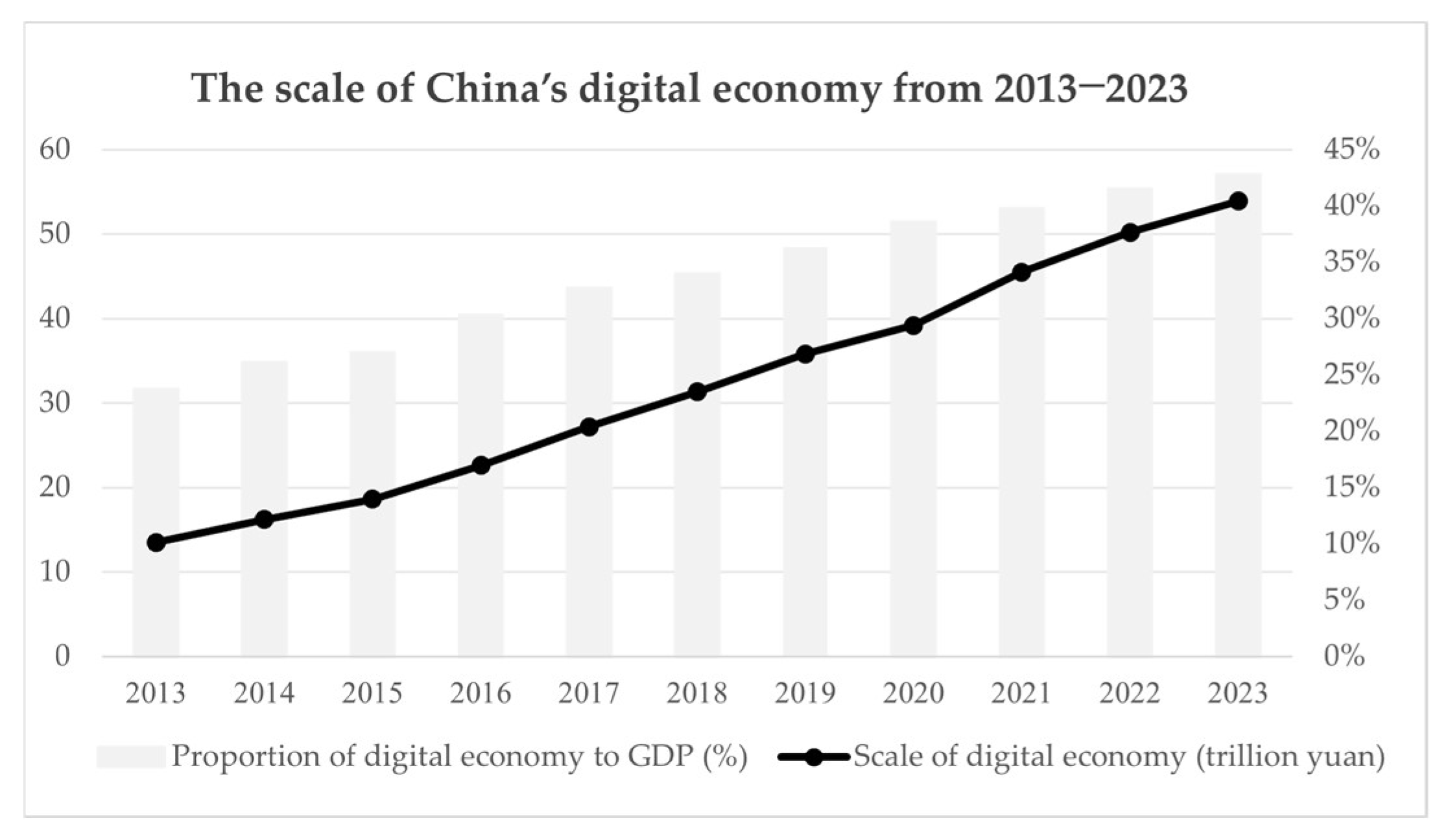

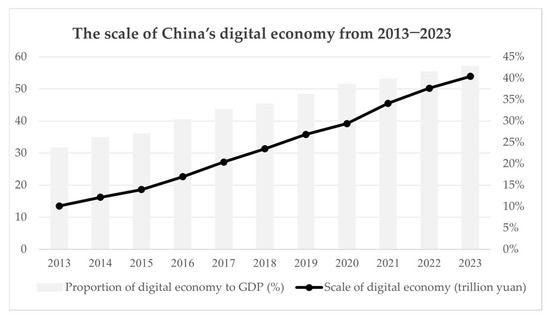

The Chinese government places high importance on the role of DC in expanding domestic demand and driving innovation-led development. Since 2013, China’s DC policy framework has been continuously refined, with the National Information Consumption Pilot Policy (ICPP) serving as a core initiative. Through fiscal incentives, infrastructure development, and scenario-based application pilots, has systematically promoted the growth of DC. This effort has not only unleashed domestic demand potential and optimized supply-side structure but also provided a crucial exogenous shock for this study. According to the “China Digital Economy Development Research Report (2024)” Figure 1, from 2013 to 2023, the scale of China’s digital economy grew from 13.5 trillion yuan to 53.9 trillion yuan, with its share in GDP increasing from 23.7% to 42.8%. This trajectory demonstrates the strong momentum of DC and reflects the significant impact of policy drivers in shaping the digital ecosystem and corporate behavior.

Figure 1.

China’s digital economy (source: China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, Research Report on China’s Digital Economy Development).

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Concept and Impacts of DC

As a new form of economic activity supported by data and digital technologies, DC is profoundly reshaping consumption structures and production modes. Early scholars, from a technological perspective, defined it as the process of information digitization enabled by information technologies such as computers, which transforms multiple stages of consumption [4]. From the perspective of consumption objects, DC refers to economic activities centered on digital products or services [5]. Building on this foundation, subsequent studies further emphasized that DC represents a dynamic process supported by internet and digital technologies and driven by data consumption to meet consumer demand [6]. In a broader sense, DC encompasses both various consumption activities conducted via digital channels and emerging consumption formats derived from digital technology iterations [7].

Regarding its effects, scholars generally agree that DC plays a significant role in improving economic efficiency and fostering innovation. In the short term, DC can enhance market efficiency by reducing transaction costs and shortening feedback cycles [8], accelerating the application of frontier technologies such as artificial intelligence [9], and stimulating firms to invest in digital skills training to build innovation capacity [10]. It also improves resource utilization efficiency through scale effects [11,12] and simultaneously creates new employment opportunities [13]. However, from a long-term perspective, some studies have identified potential risks, such as job displacement caused by technological substitution [14], platform data monopolies [15], and privacy and data security concerns [16]. Furthermore, without effective institutional constraints, the innovation-enhancing effect of DC may not be sustainable [17].

In recent years, research has increasingly focused on the systemic policy effects of DC. Empirical studies based on quasi-natural experiments have found that the ICPP promotes the construction of digital infrastructure, enhances smart land management and urban green utilization efficiency [18], improves carbon productivity [19], and reduces energy consumption and emissions through innovative consumption models [20]. Moreover, the digital–ecological synergy model has contributed to green city construction [21] and strengthened industrial resilience and urban adaptability [22]. At the firm level, the ICPP significantly promotes corporate digital transformation through channels such as technological upgrading, household consumption expansion, and financial digitization [23].

Synthesizing existing studies, it is evident that DC possesses a dual nature, simultaneously enhancing short-term efficiency and promoting long-term innovation. On the one hand, it improves market-matching efficiency through data and information flows, strengthens demand-side feedback, and stimulates continuous corporate R&D and product iteration. On the other hand, an imperfect institutional environment—characterized by insufficient data governance and weak intellectual property protection—may undermine its innovation-driving effect [24]. Although prior literature has explored the macroeconomic effects of DC, systematic micro-level analyses, particularly concerning its impact on CIA, remain limited.

From the perspectives of innovation-driven theory and endogenous growth theory, innovation is the core of sustainable corporate competitiveness [25,26]. Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction posits that the continuous emergence of new technologies and products disrupts existing equilibria and drives structural evolution [27]. DC intensifies dynamic competition by facilitating information dissemination and knowledge recombination, thereby compelling firms to engage continuously in R&D activities to adapt to market changes [28]. On the demand side, DC shortens information feedback cycles and accentuates personalized demand, prompting firms to increase R&D investment and accelerate product updates. On the supply side, leveraging big data and artificial intelligence, DC assists firms in optimizing R&D allocation, reducing costs, and enhancing innovation efficiency [8,29]. Furthermore, through the widespread adoption of digital products and services, DC intensifies market competition, incentivizing firms to pursue differentiation strategies, which collectively enhance overall industry-level innovation activity [30].

Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

DC significantly enhances CIA.

2.2. Mechanisms Through Which DC Affects CIA

As a systemic economic phenomenon, DC’s impact on CIA is not derived from a single-dimensional effect but is realized through multi-level and composite mechanisms. Drawing on the Attention-Based View (ABV), institutional economics, and the Resource-Based View (RBV), this study systematically analyzes these mechanisms from three levels: government, region, and enterprise.

2.2.1. Government Attention to S&T Talent

At the macro-institutional level, the expansion of DC significantly reshapes governmental attention allocation in public policy. With the growing digital industry and demand for high-level skills, governments increasingly focus on talent, technology, and innovation, thereby forming a crucial external environment that affects CIA. Within the frameworks of ABV and agenda-setting theory, public policy choices and resource allocations are constrained by attention scarcity—that is, only when specific issues achieve sufficient salience are they prioritized and allocated policy or budgetary attention [31,32]. Once talent-related issues gain priority, corresponding institutional arrangements and resource allocations are usually introduced, producing long-term effects on firms’ innovation activities. From this perspective, DC drives growing market demand for personalized, intelligent, and high-quality products and services, making digital skills such as algorithm engineering, big data analytics, and smart manufacturing increasingly prominent in societal needs. This, in turn, elevates the policy significance of talent shortages [33]. In response, governments often adjust policy portfolios, such as increasing research funding, optimizing tax and housing subsidies, and improving data governance and intellectual property protection frameworks. These measures help reduce institutional costs related to talent acquisition and utilization and improve the efficiency of innovation factor allocation [34]. However, if policy attention remains symbolic or superficial, it may distort resource allocation and diminish innovation incentives [35]. In contrast, sustained policy advocacy and stable investment send clear institutional signals, alleviating firms’ uncertainty about innovation returns and motivating them to increase R&D efforts, thereby enhancing CIA.

Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.

DC enhances CIA by increasing government attention to S&T talent.

2.2.2. Regional Data Elementization

At the meso-regional level, DC promotes institutional innovations in data property rights, circulation, and sharing by local governments, thereby enhancing the level of regional data elementization and indirectly influencing CIA. From the perspectives of institutional economics and factor allocation theory, the marketization and circulation of data are key institutional arrangements for improving resource allocation efficiency and stimulating innovation [36]. Data has the capability to significantly boost operational efficiency within enterprises [37]. The rise in DC accelerates data expansion and diversification, elevating its strategic significance in resource distribution. As consumers continuously generate behavioral and transactional data, local governments are driven to innovate in data property protection and government–enterprise data sharing, thus strengthening regional data elementization [38].

This process promotes CIA through multiple pathways. First, efficient data allocation mitigates information asymmetry, enabling firms to identify market trends more accurately and reduce R&D trial and error costs. Second, data openness and sharing supplement internal data deficiencies, allowing firms to enhance product iteration and process optimization via big data analytics [39]. Third, data elementization facilitates resource optimization, supporting firms in making more scientific decisions in innovation strategies and technology paths, thereby improving the market alignment of innovation outcomes [40].

Overall, DC not only creates new market opportunities through data expansion but also fosters institutional and market mechanisms that enhance data utilization, indirectly promoting CIA [41]. However, privacy protection and data security regulations may constrain this process. Inadequate institutional design could increase compliance costs and suppress innovation [42]. Therefore, the effectiveness of data elementization largely depends on institutional completeness and implementation efficiency.

Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

DC enhances CIA by improving regional data elementization.

2.2.3. Corporate Data Assetization

At the micro-enterprise level, DC encourages firms to accumulate and utilize data resources, transforming them into measurable and tradable assets, which serve as key inputs for innovation. This process strengthens internal innovation capabilities and further enhances CIA. According to the RBV and dynamic capabilities theory, a firm’s competitiveness derives from its ability to identify, integrate, and exploit scarce resources [43]. Unlike regional data elementization, corporate data assetization focuses on converting internal data resources into quantifiable and monetizable assets that are systematically integrated into R&D, production, and market processes to unlock economic and innovation potential [44]. Driven by DC, enterprises accumulate massive data through user interactions, transactions, and operational processes, laying the foundation for data assetization [45].

Corporate data assetization promotes innovation through two main mechanisms. First, the financing constraint alleviation effect: when data is recorded as assets on the balance sheet and used for collateral or securitization, external investors can more clearly assess the enterprise’s potential, reducing information asymmetry and risk premiums in financing, broadening innovation financing channels, and providing support for high-risk innovation activities [46,47]. Second, the value chain upgrading effect: data integration throughout the entire process of R&D, production, and marketing enhances project screening efficiency in R&D, optimizes resource allocation in production, and promotes precise marketing and achievement commercialization in the market [40,48]. The massive data generated by DC not only accelerates data assetization and data capital accumulation but also stimulates the innovation potential of data factors, promoting CIA and achievement transformation. The commercialization of innovation outcomes further expands data collection methods, forming new incremental data assets, thereby con-structing an internal virtuous cycle that continuously enhances CIA [42,49]. It should be noted that over-reliance on data-driven strategies may lead to short-termism and path dependence, inhibiting long-term breakthrough innovation.

Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4.

DC enhances CIA by promoting corporate data assetization.

2.3. Comment

Academia widely recognizes the significant potential of the digital economy in promoting social development, and existing research has primarily focused on its overall effects at either the macro [50] or micro [51] level. However, studies directly focusing on the specific domain of DC remain relatively scarce, particularly lacking systematic evidence identifying the causal relationship between DC and CIA from the micro-enterprise perspective. Can the ICPP effectively stimulate CIA? What are its underlying mechanisms? Does the policy effect exhibit heterogeneity? And can CIA translate into high-quality innovation outcomes?

To systematically address these questions, this study is grounded in the quasi-natural experiment setting provided by the ICPP. This policy selected pilot cities in batches across different regions, and its approval process was independent of individual firms’ innovation decisions, satisfying the exogeneity requirement and providing a precondition for identifying the causal effect between DC and CIA. This paper focuses on the following core research objectives: (1) Utilizing the ICPP as a quasi-natural experiment and employing a Difference-in-Differences approach to identify the causal effect of DC on CIA and its underlying mechanisms; (2) Investigating the heterogeneous effects from dimensions such as regional differences, regional digital attention, and executive equity incentives; (3) Examining whether CIA can be translated into innovation outcomes, distinguishing between substantive innovation and strategic innovation.

The marginal contributions of this paper can be summarized in the following three aspects:

First, this study is the first to integrate DC and CIA within a unified analytical framework, constructing a pathway of “Government Attention to S&T Talent–Regional Data Elementization–Corporate Data Assetization.” It systematically reveals the logical chain through which DC promotes CIA via multi-level transmission mechanisms. Unlike existing research that predominantly focuses on macroeconomic performance or innovation output, this paper adopts the dynamic perspective of “innovation activity.” This approach deepens the understanding of DC’s intrinsic mechanisms, expands the research boundaries on the driving factors of CIA, and provides theoretical support for the economic effects and policy optimization of the ICPP.

Second, in measuring CIA, this study constructs an indicator system for innovation activity based on textual analysis, moving beyond the traditional reliance on patent counts or R&D investment. This method largely mitigates issues such as truncation bias and data missingness, offering a more comprehensive depiction of the frequency, breadth, and persistence of corporate innovation, and providing a new empirical tool for measuring innovation capability. Furthermore, this paper systematically examines the heterogeneous impact of DC on CIA from three dimensions: geographical location, local government digital attention, and corporate management incentives. It reveals the differential roles of external environment and internal governance in policy transmission, providing empirical evidence for the differentiated implementation of DC policies.

Third, based on identifying the effect of DC on enhancing innovation activity, this study further examines whether this activity translates into substantive innovation outcomes. The results indicate that DC significantly promotes high-quality innovation output represented by invention patents, while having a weaker effect on strategic innovations such as utility models and design patents. This finding reveals the intrinsic link between innovation activity and innovation quality, providing important references for policymakers in optimizing innovation incentives and avoiding “low-quality innovation.”

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This study selects China’s A-share non-ST listed companies from 2008 to 2022 as the research sample. To ensure the validity of the results. First, we excluded firms in the financial and insurance industries, firms suspended or delisted during the sample period, and companies with severely missing data. Second, we also removed firms that changed registered addresses, relocated, or maintained operations across multiple geographical locations, so as to maintain geographic consistency and improve the reliability of the analysis. Finally, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of outliers.

The lists of the first and second batches of information consumption pilot cities were obtained from official documents issued by China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. The raw corporate data were sourced from the CSMAR and CNRDS databases, as well as annual reports of listed companies. Regional level data were collected from the China City Statistical Yearbook and prefectural level government work reports. All data processing and analysis were conducted in Stata 18 and Python 3.10 environments, with Python primarily employed for text segmentation and keyword extraction of textual data, and Stata utilized for regression estimation and robustness checks.

3.2. Variable Design

3.2.1. Explained Variable

An innovation-related keyword list was compiled by selecting terms with the highest frequency in innovation contexts. For the Management Discussion & Analysis sections of the annual reports, Chinese text segmentation was performed using the jieba library in Python. Numerical expressions, English terms, punctuation, and common stop words were removed, along with words lacking specific meaning in the annual reports, to ensure validity. The total frequency of keyword occurrences was calculated, and the ratio of keywords to total word frequency was logarithmically transformed. This ratio measures the proportion of innovation-related terms in the M&D text, with higher values indicating greater corporate innovation vitality. See the specific word cloud map in Figure A1. For detailed keywords, see Table A1.

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

This study uses a policy treatment variable (DID) based on the ICPP. The variable is formed by interacting a city dummy variable (treat) with a policy implementation time dummy variable (post), which allows us to identify the policy effect of the ICPP. Specifically, the city dummy variable (treat) assigns a value of 1 to pilot cities as the treatment group and 0 to other cities as the control group. The time dummy variable is determined based on the timeline of the lists announced by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology in 2013 and 2014, with the pre-policy period assigned a value of 0 and the post-policy period a value of 1 (see Table A2 for the specific list). This processed variable serves to construct a quasi-natural experimental framework, providing the identification basis for subsequent Difference-in-Differences (DID) estimation.

3.2.3. Control Variables

To account for potential factors influencing CIA, the following indicators were selected as control variables: firm size (Size), reflect resource endowment and risk taking capacity; leverage ratio (Lev), characterize capital structure and financial risk; return on assets (ROA), represent corporate profitability and internal financing capability; Tobin’s Q (TobinQ), proxy investment opportunities and market expectations; largest shareholder ownership (Top1), reflect ownership concentration and governance structure; intangible assets (Intangible), measure knowledge capital and technological reserves; quick ratio (Quick), control for short-term liquidity constraints; R&D investment (RD), directly capture innovation input intensity; firm age (FirmAge). Control for the impact of lifecycle stages. Detailed definitions of all variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition and description of key variables.

3.3. Research Design

Based on the theoretical framework, this study treats the ICPP as an exogenous policy shock and employs it to design a quasi-natural experiment for identifying the causal effect of DC on CIA. Considering the staggered implementation of ICPP, a multi-period Difference-in-Differences (DID) model was identified which is presented in Equation (1), as follows:

In this specification, denotes the dependent variable measuring the innovation activity of firm i in year t. represents the constant term, is the core estimated coefficient capturing the net effect of the information consumption pilot policy on corporate innovation activity. is defined as the interaction term between a city dummy (Treat) and a post-policy dummy (Post), and equals 1 if firm i is located in a pilot city during the policy period and 0 otherwise. represents the coefficients of control variables, reflecting their impact on CIA. represent nine firm-level covariates to account for other potential influencing factors. and denote industry and year fixed effects, respectively, controlling for time-invariant industry characteristics and macro-level shocks. is the error term. All regressions were completed in Stata 18, employing firm-level cluster-robust standard errors to correct for heteroskedasticity and within-group autocorrelation issues.

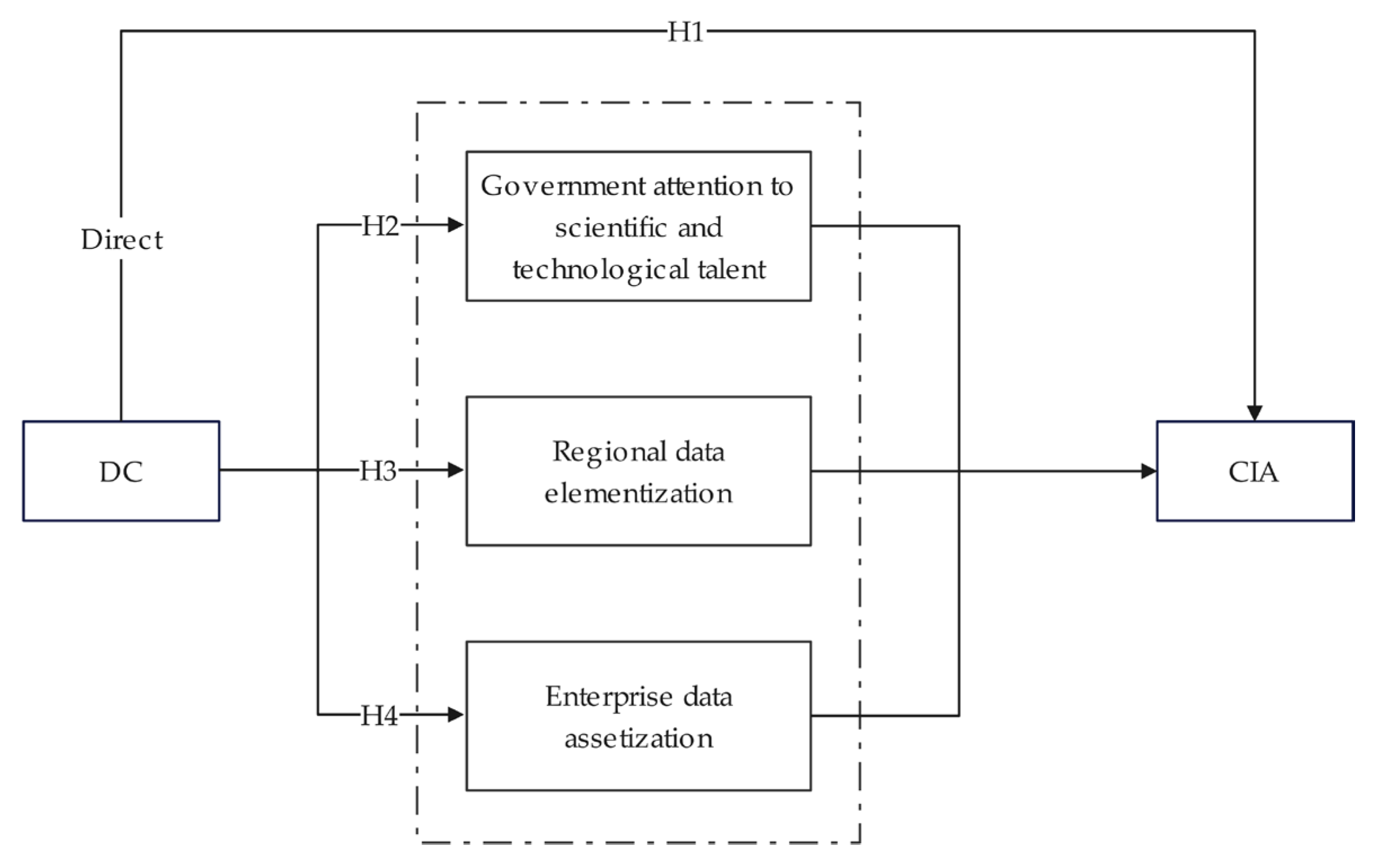

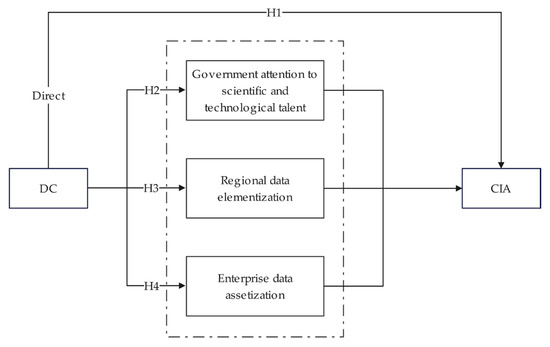

Theoretical analysis reveals multiple potential pathways through which DC affects CIA. To integrate these perspectives and systematically explain its mechanisms of action, this study constructs a theoretical framework (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework.

To empirically test this framework, drawing on previous research [21], this paper constructs a panel mediation effect model for mechanism testing, as shown in Equations (2) and (3):

Here, represents the mechanism variables, namely government attention to S&T talent (GOV), regional data elementization (RDE) and corporate data assetization (CDA), as theorized in the previous hypotheses. represents the coefficient of the mechanism variable, used to verify whether the mechanism variable has a significant effect on CIA. The definitions of the remaining variables are consistent with those in Model (1).

This empirical design is directly aligned with our proposed theoretical framework Figure 2 and research hypotheses. Specifically, the coefficient of the core interaction term in the DID model effectively identifies the net effect of the ICPP policy shock. This policy serves as a quasi-natural experiment, providing a valid proxy for capturing the exogenous driving force of DC. This estimation directly provides the foundational test for H1. To further empirically verify the transmission mechanisms proposed in the theoretical framework (H2–H4), we introduce the following mediating variables: GOV to test mechanism H2, RDE to test mechanism H3, and CDA to test mechanism H4. This alignment ensures the empirical analysis is rigorously tied to the theoretical conjectures and offers direct empirical validation.

To further ensure the reliability of the findings and more comprehensively identify the impact of DC on CIA, several extended tests were conducted. In the robustness check section, we conducted a series of tests to validate our findings: a placebo test was performed to confirm the non-random nature of the policy effect; special samples were excluded to mitigate potential biases arising from unique economic status or policy environments; specific years were omitted to control for the influence of major external shocks; PSM-DID method was employed to address sample selection bias; competing policies were controlled for to isolate the independent net effect of the ICPP; irrelevant variables were introduced to eliminate potential confounding factors; and we accounted for potential bias arising from treatment effect heterogeneity across cohorts to secure unbiased causal inference. To further address potential endogeneity issues, the Heckman two-stage model was utilized to correct for sample selection bias, and an instrumental variable approach was constructed to capture exogenous variation induced by the policy shock. For mechanism testing, grounded in theoretical hypotheses, GOV, RDE, and CDA were incorporated into the empirical framework as mediating variables. The statistical significance of the mediating pathways was rigorously verified using Sobel tests and Bootstrap methods. Finally, heterogeneity analysis was conducted based on dimensions such as geographical distribution, government digital attention, and corporate incentive mechanisms. Through subsample regression analysis and the Chow test, we systematically examined the heterogeneous performance of policy effects across different contexts.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics, Multicollinearity, and Correlation Analysis

Prior to conducting empirical tests, this study first performed descriptive statistical analysis to examine the overall distribution characteristics and data properties of the main variables. The purposes of this step are (1) to verify the rationality of the data and variability of variables used in the econometric model; (2) to develop an intuitive understanding of the relationships between main variables before regression analysis. Particularly within the Difference-in-Differences (DID) framework, descriptive statistics are crucial for confirming the comparability and balance between treatment and control groups before and after policy implementation. Specifically, all continuous variables were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the impact of outliers on regression results. Subsequently, statistical measures including mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values were calculated for each variable. Furthermore, to ensure the reliability of the regression models, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) tests were conducted on all independent variables to identify potential multicollinearity issues.

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables. The mean value of CIA is 4.167 with a standard deviation of 0.703, indicating substantial variation in innovation activity among the sample firms. The mean of the policy variable DID is 0.557, suggesting that approximately 55.7% of the observations in the sample fall within the policy treatment period. The sample sizes of the treatment and control groups are relatively balanced, providing a solid foundation for the difference-in-differences analysis. The distributions of the remaining control variables all fall within reasonable ranges. To rule out potential bias in the estimation results caused by multicollinearity, we calculated the VIF for all independent variables. As shown in Table A3, the average VIF for all variables is 1.38, and the VIF for each individual variable is well below the common threshold of 10. The correlation coefficient matrix Table A4 also shows that the vast majority of pairwise correlation coefficients between the independent variables are below 0.5. This indicates the absence of severe multicollinearity issues in the model, and the regression estimation results are robust.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of main variables.

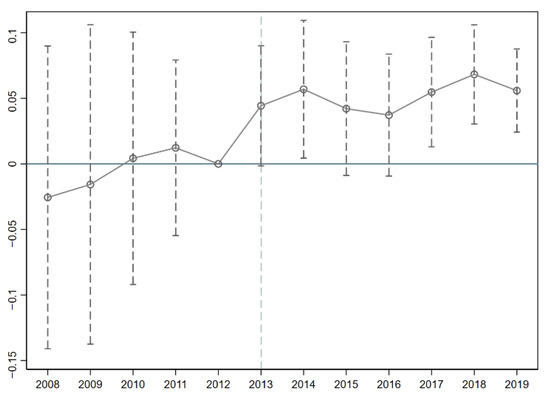

4.2. Parallel Trend Test

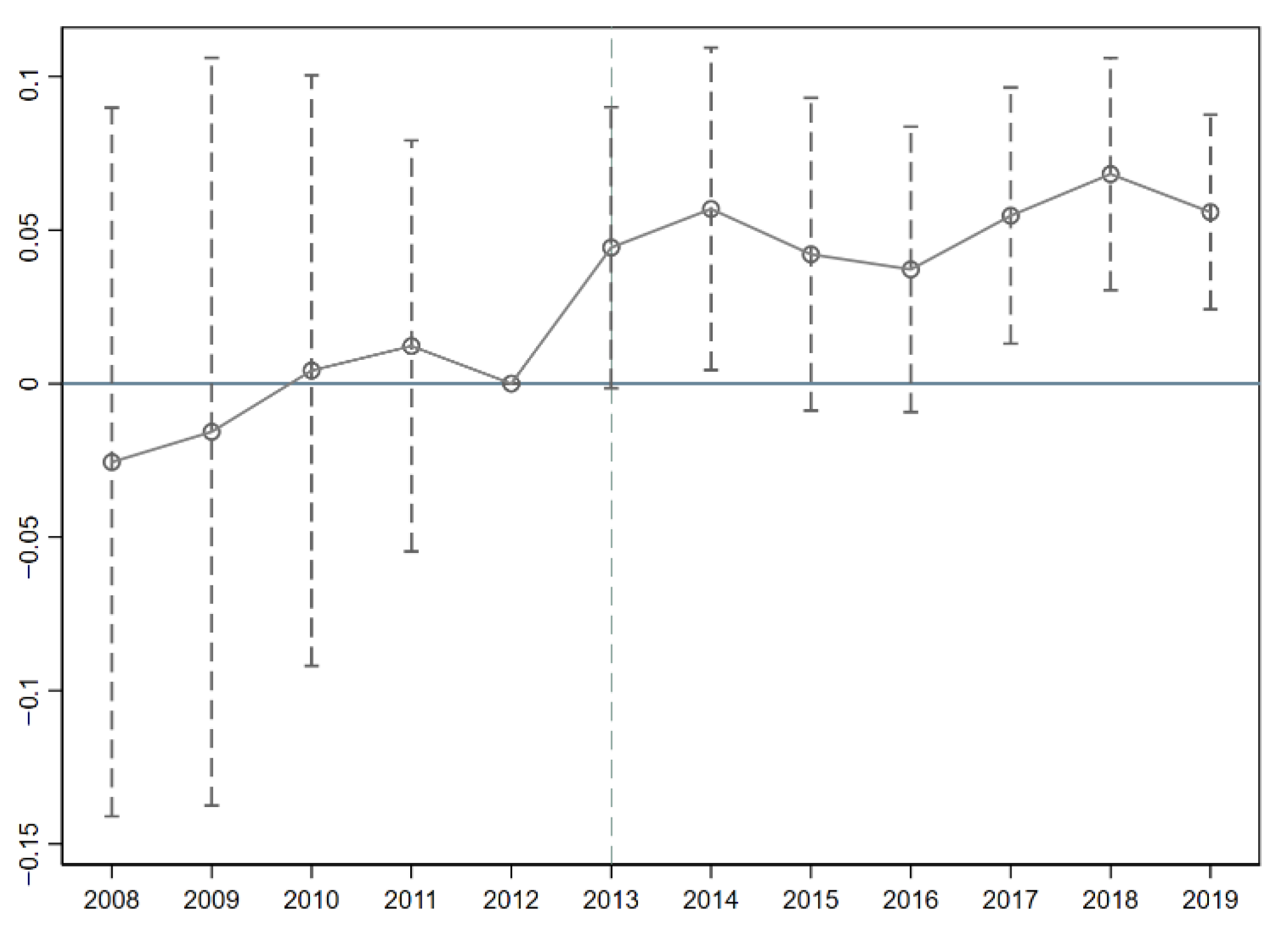

The ICPP was implemented in staggered batches during 2013 and 2014. To address this feature and test the parallel trends assumption, an event study approach was adopted. this study draws on the approach of [52] by employing an event study method to conduct a parallel trends test. Using the period immediately prior to the implementation of the ICPP as the baseline, was plotted with the horizontal axis representing the dynamic time points of the policy and the vertical axis showing the estimated coefficients of the ICPP on CIA. As illustrated in Figure 3, the estimated coefficients fluctuated around zero within the 95% confidence interval for the five years preceding the policy implementation, indicating no significant differences between the pilot cities and the control group cities before the policy took effect. This satisfies the parallel trends assumption, validating the use of the difference-in-differences method for causal inference. The results show that in all periods prior to the policy implementation, the estimated coefficients are all close to zero and their 95% confidence intervals include zero. This indicates no significant pre-existing trend differences between the treatment and control groups before the policy implementation, failing to reject the parallel trends assumption. This provides key support for the validity of using the difference-in-differences method for causal inference. The slight increase in regression coefficients during the two pre-policy periods might be attributed to the “anticipation effect” in China’s policy implementation process. The competitive application and qualification review for pilot cities release strong signals, prompting corporate management to adjust innovation activity layouts in advance based on anticipated selection. The dynamic effects results reveal a noticeable lag in the promoting effect of ICPP on CIA. The policy’s impact fluctuated in the implementation year and within two to three years afterward, becoming significant and consistently prominent only starting from the fourth year. The reasons for this may include policy implementation is not instantaneous; the construction of digital infrastructure, the rollout of supporting detailed rules, and corporate adaptation and adjustment to the new policy all require time, preventing the policy effects from materializing immediately.

Figure 3.

The parallel trend test.

4.3. Base Line Regression

Table 3 presents the baseline regression results of DC on CIA. In column (1), which includes only the core explanatory variable DID, the coefficient is 0.2598, which is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that DC significantly promotes CIA without controlling for other factors. In column (2), after incorporating firm-level control variables, the DID coefficient decreases to 0.2101 but remains significantly positive at the 1% level, demonstrating that the policy effect remains robust after controlling for factors such as firm size, financial structure, profitability, ownership concentration, and innovation input. This suggests that the innovation-promoting effect of digital consumption is not driven by differences in firm characteristics but exhibits strong policy endogeneity and universal applicability. Column (3) further includes industry and year fixed effects to control for industry heterogeneity and macroeconomic trends. The DID coefficient here is 0.0446, still significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating the effect’s robustness under more stringent model specifications. Observing the coefficient trend, although the DID coefficient decreases with the gradual inclusion of control variables and fixed effects, it remains significantly positive throughout, demonstrating that the promoting effect of digital consumption on CIA is robust and persistent.

Table 3.

Base line regression test.

In terms of economic significance, the results indicate that the information consumption pilot policy significantly enhances CIA by improving data element circulation, stimulating market demand, and promoting corporate digital transformation. This finding validates Hypothesis H1, confirming that digital consumption significantly enhances corporate innovation activity.

Additionally, results for some control variables align with expectations. The positive coefficient for suggests that larger enterprises possess stronger resource integration and R&D capabilities; the negative effect of on CIA indicates that high debt levels may inhibit innovation investment; the significantly positive demonstrates that good liquidity helps support corporate innovation investment. In summary, the baseline regression results not only verify the significant positive effect of digital consumption but also provide theoretical and empirical foundation for subsequent robustness tests and mechanism analysis.

4.4. Robustness Analysis

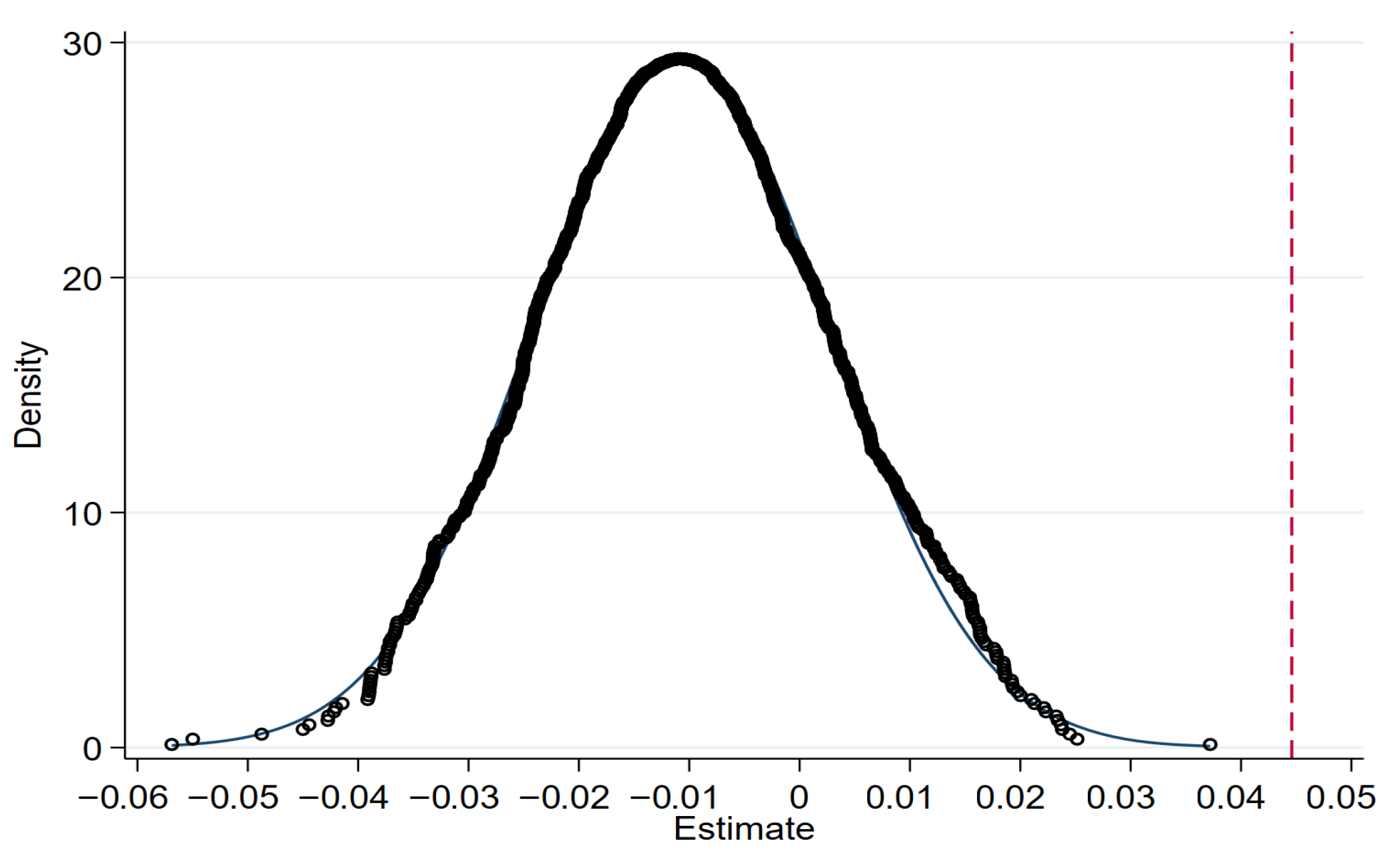

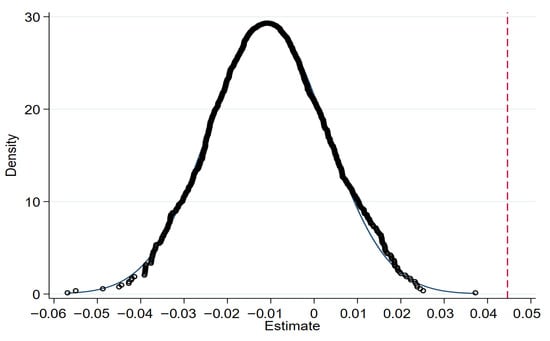

4.4.1. Placebo Test

To verify the robustness of the results and control for potential biases caused by unobservable factors, this study employs a placebo test method. In the placebo test, 2422 non-treatment group samples were randomly selected as a simulated treatment group, and each simulated treatment group was randomly assigned a policy implementation time point to construct a hypothetical policy interaction term (did). Using this hypothetical variable, regression was performed based on the same model as the baseline regression. This process was repeated 1000 times, and the estimated coefficients of the hypothetical policy variable (did) were recorded for each regression. The 1000 coefficients were then plotted into a kernel density distribution graph, as shown in Figure 4. In 1000 random simulations, the coefficients of the fictional policy effects are clustered closely around zero, with their density curve exhibiting a typical normal distribution pattern. The vast majority of the estimated coefficients are statistically insignificant at the 0.1 level. Meanwhile, the true policy effect coefficient from the baseline regression is 0.0446, which lies far from the distribution center of the randomly simulated coefficients. Moreover, almost none of the simulated coefficients exceed 0.04, indicating a significant difference between the simulation results and the true coefficient from the baseline regression. These results demonstrate that the significant policy effect identified in the baseline regression is not driven by random factors, thereby verifying the robustness of the research conclusions.

Figure 4.

Placebo test result.

4.4.2. Account for the Effects of Heterogeneous Treatment

Furthermore, to mitigate potential biases arising from heterogeneous treatment effects, this study employs the heterogeneous robust estimator proposed by Sun and Abraham for estimation [53]. The results, as shown in Table 4, indicate that the coefficient of the core explanatory variable is significantly positive at the 5% level, consistent in direction with the baseline regression results. This further validates the robustness of our conclusions.

Table 4.

Heterogeneity Treatment Effect.

4.4.3. Other Robustness Analysis

First, considering that special events may affect CIA, this study excludes samples from the periods most severely impacted by the financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, namely 2008 and 2020. During these periods of financial crisis and pandemic turmoil, the external operating environment for enterprises deteriorated sharply, internal development was constrained, and internal management decision-making was affected, which could significantly influence CIA. The results in Column (1) of Table 5 show that after excluding samples from the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic shock, the coefficient of the core explanatory variable remains significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the conclusions are not driven by macroeconomic shocks in specific years.

Table 5.

Other Robustness Analysis result.

Second, excluding cities with strong innovation capacity, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen hold leading positions in China. Their levels of economic development, digital infrastructure, innovation resource endowment, and policy support differ significantly from most other Chinese cities, which may introduce sample selection bias and interfere with the estimation results. This study excludes samples from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen and conducts robustness checks using the remaining sample. The results in Column (2) of Table 5 show that after excluding extreme samples with highly concentrated innovation resources like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, the core coefficient remains significant. This indicates that the policy effect of ICPP is not limited to a few innovative cities but also holds in a broader range of ordinary cities.

Third, to reduce potential sample selection bias in the difference-in-differences (DID) approach, this study further employed a propensity score matching model (PSM-DID) to examine the impact of the DC on CIA. Using a one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching method annually, control group enterprises were matched during the sample period. The regression was then re-estimated. As shown in Column (3) of Table 5, After controlling for pre-existing differences between the treatment and control groups, the core coefficient remains significantly positive. This implies that the research conclusions primarily stem from the policy shock itself, rather than from inherent advantages already possessed by the treatment group cities before implementation.

Fourth, given that overlapping effects from other policies during the sample period of ICPP’s impact on CIA might lead to overestimation or underestimation of the results, this study incorporated multiple policies related to information infrastructure construction promulgated by the government during the same period, such as the “Broadband China” pilot policy and the “Smart City” pilot policy. Dummy variables for these policies (DIDA and DIDB) were simultaneously introduced into the multi-period DID model to test whether the improvement in CIA stemmed from the impact of other related policies. The results in Column (4) of Table 5 show that, after controlling for the interference of these two competing policies, the estimated coefficient of the core explanatory variable remains significantly positive at the 5% level. This suggests that the policy effect is not a product of the superposition of other policies but indeed originates from the independent role of ICPP.

Fifth, to exclude the possibility of spurious correlation caused by unobservable factors, we replace the dependent variable with the logarithm of the number of corporate board members (Board) for an irrelevant variable test. Board size is a relatively stable internal corporate governance characteristic, whose changes are primarily driven by major events such as amendments to corporate charters or mergers and acquisitions. The ICPP does not directly intervene in corporate governance structures. The results in Column (5) of Table 5 show that when board size is used as the dependent variable, the core coefficient is statistically completely insignificant. This indicates that the policy does not affect stable characteristics of internal corporate governance, thereby ruling out the possibility of spurious correlation.

4.5. Endogeneity Test

4.5.1. Heckman Two Stage Model

The selection of information consumption pilot cities may be influenced by factors such as the level of regional information infrastructure construction and economic development, potentially leading to sample self-selection issues. To address this, the Heckman two-stage model was employed for testing. The specific approach is as follows: regional river density (IV1) was selected as an instrumental variable. This is because, in the early stages of urban development, inland rivers were closely linked to canal trade. Higher river density was associated with more prosperous canal trade, which in turn promoted urban economic development and enhanced information exchange and transmission capabilities. This historical context may influence the selection of information consumption pilot cities. As a geographical feature, river density primarily affects CIA through its historical impact on urban infrastructure construction and economic development.

However, contemporary enterprises are more influenced by current economic conditions, such as policy and market environments, digital and information facilities, and other practical factors, rather than directly affected by river density. Therefore, regional river density is strictly exogenous and suitable as an instrumental variable.

In the first stage of the Heckman probit model, the dependent variable was whether the city where an enterprise is located was selected as an information consumption pilot city (assigned a value of 1 if yes, and 0 otherwise). The inverse Mills ratio (IMR) was calculated based on the first stage regression results and incorporated into the second-stage model for regression. Table 6 presents the results of the Heckman two-stage regression. Column (1) shows that the instrumental variable is significantly positive, indicating that higher urban river density increases the likelihood of being selected as an information consumption pilot city. Column (2) displays the results of the Heckman two stage regression after including the IMR. The IMR is significant at the 5% level, suggesting the presence of non-negligible sample selection bias. After controlling for this bias by including the IMR, the explanatory variable remains significant, further supporting the robustness of the study’s findings.

Table 6.

Heckman two-stage model.

4.5.2. Instrumental Variable Method

Based on the above conclusions, DC can effectively promote CIA. However, an increase in CIA implies that enterprises will engage in more innovation activities, leading to breakthroughs in digital technology and other innovations, which in turn drive the development of DC and influence government planning and selection of pilot cities. This may give rise to reverse causality issues. Although control variables have been included in the model, measurement errors or oversights in the main variables may still cause endogeneity problems. Therefore, the instrumental variable method was used to mitigate endogeneity issues in the model.

Drawing on the approach of [54], this study addresses endogeneity using the instrumental variable method. The number of landline telephones per ten thousand people in cities in 1984 and the number of post offices per million people in cities in 1984 were selected as instrumental variables, and estimates were obtained using the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method. As a component of information infrastructure, landline telephones represent the level of regional communication technology development to some extent, affecting a city’s capacity for information exchange and transmission. This makes cities with higher historical landline telephone penetration more likely to be selected as information consumption pilot cities, satisfying the relevance condition for instrumental variables. Since 1984 was over 40 years ago, although historical legacies may have marginal effects on current urban development and corporate innovation, their impact on CIA is negligible compared to contemporary rapidly iterating digital communication technologies, satisfying the exogeneity condition for instrumental variables. As the 1984 landline telephone data and the number of post offices per million people in cities in 1984 are cross-sectional, while this study uses panel data, interaction terms were constructed by multiplying the instrumental variables (IV2 and IV3) with year dummy variables.

The results in Column (1) of Column (2) show that after controlling for endogeneity, the coefficient on DC remains significant, further confirming the robustness of the findings.

Table 7 shows that the coefficient of IV2 and IV3 is significantly positive, indicating a correlation between the instrumental variable and the ICPP. The endogeneity test is significant at the 1% level, confirming the presence of endogeneity in the model. The Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic exceeds the 10% critical value of 16.38, indicating no weak instrument problem. The Kleibergen-Paap rk LM test results show a p-value less than 0.01, confirming that the instrumental variable is not under-identified. The p-value of the Hansen J statistic is 0.545, meaning the null hypothesis that the instruments are valid (not overidentified) cannot be rejected at the 10% significance level. This indicates that the instrumental variables also pass the overidentification test. Column (2) shows that after controlling for endogeneity, the coefficient on DC remains significant, further confirming the robustness of the findings.

Table 7.

Instrumental variable method result.

4.6. Mechanism Test

4.6.1. Enhancing Government Attention to S&T Talent

Drawing on the approach of [55], this study constructs a metric for government attention to S&T talent by calculating the total frequency of keywords related to basic research and scientific talent in local government work reports. For specific keywords, see Table A5.

As shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 8, the estimated coefficient of DID on GOV is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that DC contributes to enhancing regional government attention to S&T talent. The regression coefficients of both DID and GOV on CIA are significantly positive, demonstrating that DC promotes CIA through GOV. To achieve regional sustainable development, local governments signal their commitment to attracting talent by implementing a series of fiscal subsidies and support policies, generating a talent aggregation effect. Enterprises can leverage this to optimize their human capital structure, enhance innovation capabilities, and gain momentum for conducting innovation activities. Bootstrap tests with 1000 replications show that the confidence interval estimates for the indirect effect do not include zero, and the Z-statistic from the Sobel test is also significant (Z = 4.576), verifying that GOV acts as a partial mediator between DC and CIA.

Table 8.

Mechanism tests.

4.6.2. Promoting Regional Data Elementization

The development level of the software industry directly reflects a region’s capacity in data collection, processing, and application. Its revenue scale largely indicates the extent to which data elements are transformed into productive factors. Following ref. [56], this study selects regional software business sales revenue as a proxy variable for data elementization to measure the level of data elementization across different regions.

Columns (3) and (4) of Table 8 show that the coefficient of DID on RDE is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that DC facilitates the advancement of regional data elementization. The regression coefficients of both DID and RDE on CIA are significantly positive, confirming that DC promotes CIA through RDE. The improvement in regional data elementization effectively enhances the circulation of data elements, enabling enterprises to access richer data resources. Data elements act as catalysts, increasing the success rate of innovation, shortening innovation cycles, and boosting enterprise productivity. This allows enterprises to more efficiently unleash innovation resources, thereby driving the enhancement of CIA. Bootstrap tests with 1000 replications show that the confidence interval estimates for the indirect effect do not include zero, and the Z-statistic from the Sobel test is significant (Z = 2.611), verifying that RDE plays a partial mediating role between DC and CIA.

4.6.3. Facilitating Corporate Data Assetization

Following the methodology of [57], this study constructs a core metric for corporate data assetization by mining text data from annual reports of A-share listed companies using dictionaries for owned data assets (ODA) and tradable data assets (DDA) to extract keyword frequencies. See the specific word cloud map in Figure A2.

Columns (5) and (6) of Table 8 reveal that the coefficient of DID is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that DC contributes to promoting corporate data assetization. Simultaneously, the regression coefficients of both DID and CDA on CIA are significantly positive, demonstrating that DC enhances CIA through CDA. Existing research shows that data assetization can significantly drive high-quality enterprise development through innovation. By leveraging data assetization, enterprises can unlock the value of data, swiftly identify innovation opportunities, accelerate innovation efficiency, and apply innovation outcomes in a cost-effective manner. Overcoming technical bottlenecks and gaining a market advantage further elevates CIA, fostering a new cycle of innovation activities. Bootstrap tests with 1000 replications show that the confidence interval estimates for the indirect effect do not include zero, and the Z-statistic from the Sobel test is significant (Z = 2.435), verifying that CDA plays a partial mediating role between DC and CIA.

4.7. Heterogeneity Analysis

To more comprehensively reveal the impact mechanisms of DC on CIA, this study further conducts heterogeneity analysis. Given that corporate innovation behavior is influenced not only by macro policy environments but also exhibits differentiated characteristics due to regional development conditions, external policy attention, and internal governance structures, it is necessary to conduct an in-depth examination across grouping dimensions. Specifically, this study categorizes the sample based on three aspects: the region where enterprises are located, external government digital attention, and the level of internal management incentives, to test whether the policy effects of ICPP on CIA vary significantly under different contexts.

First, this study divides China into eastern, central, and western regions. The findings reveal significant heterogeneity in the impact of DC on CIA across regions, as shown in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 9. The eastern region exhibits a significantly positive effect at the 5% level, while the central region shows a positive but statistically insignificant coefficient, and the western region demonstrates a negative and insignificant coefficient. This indicates that the policy impact on CIA is more pronounced in the eastern region, where innovation activities are more frequent. The weaker effects in the central and western regions may be attributed to the following two factors: Economic Development Disparities and Digital Infrastructure Gaps. The eastern region, being the most economically developed area, boasts broader markets, a stronger economic foundation, and greater attractiveness to S&T talent, providing enterprises with a robust pool of research talent. Local governments in this region also exhibit higher attention to digitalization, offering more fiscal subsidies to incentivize corporate innovation. In contrast, the central and western regions lag in economic development and struggle to attract talent. The circulation of data elements relies heavily on infrastructure support. The eastern region, having undergone earlier digital transformation, possesses more advanced digital infrastructure, such as data centers and cloud computing facilities. Conversely, the central and western regions, with their later digital transformation, suffer from inadequate digital infrastructure, hindering the flow of data elements and making it challenging for enterprises to access sufficient data resources. To ensure the robustness of the subgroup regression results, this study employs the Chow test to examine coefficient differences between groups. Columns (1)–(3) of Table 9 report the test coefficients between the Eastern and Western regions (Chow test value = 15.02, significant at the 1% level), the Central and Western regions (Chow test value = 12.94, significant at the 1% level), and the Eastern and Central regions (Chow test value = 22.79, significant at the 1% level), respectively. The results are all significant at the 1% level, indicating significant differences among the three sample groups.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity tests.

Second, the enhancement of innovation activity and the vibrant circulation of data elements rely heavily on government support. Using the jieba tool for text segmentation, this study calculates the frequency of digital economy-related keywords in prefectural-level government reports and measures local government attention to the digital economy by its proportion to the total word count. The full sample is divided into “strong digital attention” and “weak digital attention” groups based on the annual median for heterogeneity analysis. As shown in Columns (4) and (5) of Table 9, enterprises located in regions with strong digital attention are significantly positively affected by the policy at the 1% level, while those in regions with weak digital attention experience a weaker policy impact. This difference is primarily because local governments with higher emphasis on digital economy development invest more heavily in digital technology advancement. To foster regional digital economy and DC growth, these governments implement more policies to improve the business and market environment, thereby enhancing corporate innovation willingness. The two sample groups show a significant difference (Chow test value = 6.61, significant at the 1% level).

Finally, based on the annual median of management shareholding, sample enterprises are divided into “weak long-term incentives” and “strong long-term incentives” groups for heterogeneity analysis. As shown in Columns (6) and (7) of Table 9, the impact of ICPP on CIA is significant at the 5% level for enterprises with strong long-term incentives, while the coefficient for those with weak long-term incentives is positive but statistically insignificant. This indicates that DC has a more substantial effect on CIA in enterprises with strong long-term incentives. The reason lies in the fact that R&D activities often require extended periods to yield outcomes. If managers prioritize short-term gains, they may lack the motivation for innovation-driven decisions. Management shareholding, as a long-term incentive mechanism, aligns the interests of managers with those of the enterprise, encouraging them to adopt a long-term perspective in strategic decision-making. To build core competitiveness through innovation and secure a competitive edge, managers are more inclined to sacrifice short-term benefits and invest in innovation for long-term development. The two sample groups show a significant difference (Chow test value = 17.93, significant at the 1% level).

4.8. Innovation Outcomes and Quality Analysis

The baseline regression results above have demonstrated that DC significantly enhances CIA. However, a critical question remains: does the increase in innovation activity truly translate into tangible innovation outcomes? To address this, this study first examines the total patent output and then further decomposes the analysis from the perspective of innovation quality.

As shown in Column (1) of Table 10, the regression coefficient of the ICPP on total corporate innovation output is positive but not statistically significant. This implies that the increase in innovation activity does not directly lead to a significant growth in overall patent quantity in the short term. A possible explanation is that the differentiation in the quality of different types of innovations may offset the aggregate-level results. Therefore, this study further categorizes patents into two types: invention patents, which represent substantive innovation characterized by high R&D investment and long cycles, and utility model and design patents, which often reflect strategic innovation with lower costs and thresholds [58].

Table 10.

Base line regression result.

When further disaggregating innovation types, it is found that ICPP significantly promotes substantive innovation at the 1% level, while its impact on strategic innovation is not significant. This indicates that DC not only enhances CIA but also, driven by demand traction and competitive pressure, guides enterprises to allocate additional R&D resources toward core technological breakthroughs to strengthen differentiated competitiveness. In contrast, strategic innovation, which has limited technological content and market value, is not significantly incentivized.

Furthermore, to unveil the temporal path of the policy effect, this study employs a dynamic difference-in-differences approach to examine different types of innovation. Table 11 shows that in the year of policy implementation , ICPP already exerts a significantly positive effect on substantive innovation, indicating that the policy can rapidly stimulate corporate R&D investment through signaling and resource allocation mechanisms. However, during the periods from to , although the coefficients remain positive, they are overall insignificant. This “dormancy period” reflects a reasonable lag in policy effects: enterprises need time for strategic adjustment, technological accumulation, and R&D project initiation in the initial stage, while the institutional review cycle for patent applications also contributes to the delay in observable outcomes. Notably, starting from , the policy’s promoting effect on substantive innovation gradually strengthens and peaks at , demonstrating a clear long-lag effect and sustained positive impact. In contrast, strategic innovation shows no significant policy response throughout the entire period, further confirming its marginal value in the context of DC.

Table 11.

Dynamic DID model results.

Further analysis reveals that DC does not lead to a significant expansion in total patent output but instead channels innovation activity toward higher-value substantive innovation through a quality differentiation effect. This process exhibits both structural characteristics and dynamic patterns—it triggers high-quality R&D immediately but requires mid-term adjustment and long-term accumulation to yield significant outcomes. This not only elucidates the mechanism through which innovation activity translates into innovation quality but also provides insights for policymakers: while promoting DC, efforts should be oriented toward incentivizing high-quality innovation to avoid the illusion of “low-quality innovation” driven solely by quantity.

Beyond China, the findings of this study also hold certain reference value for the development of DC in other countries. Existing research indicates significant differences among BRICS countries in terms of consumption patterns, social behaviors, and government governance, which directly influence whether DC can be smoothly transformed into innovation momentum [59]. For example, although India has the world’s second-largest internet user base, the innovation-driving effect of its DC on enterprises has not been fully realized due to insufficient payment trust mechanisms and cultural inertia [60]; countries like Brazil have been unable to effectively tap the potential of digital resources due to limitations in data collection and governance capabilities [61].

In contrast, China, leveraging an institutionalized system for data collection, evaluation, and regulation, has effectively transformed DC into an institutional force that drives corporate innovation. This not only highlights the uniqueness of the “China model” but also provides a new explanatory framework for cross-national research, suggesting that the institutional and policy environment decisively influences the intensity and efficiency of DC’s effects. This point is further illustrated by comparisons from the consumer end. The popularization of digital payments in India is constrained by performance expectations and trust deficits; Japan’s digital subscription services, despite their potential, are limited by cultural habits and market perceptions [62]. In contrast, through policy guidance and institutional design, China has proactively built user trust, enhanced consumption expectations, and optimized consumption habits and market perceptions, thereby significantly amplifying the driving effect of DC on corporate innovation.

Therefore, this study not only verifies the universal mechanism of “DC driving corporate innovation” but also reveals its differential performance across various institutional environments. Compared with the existing literature, the unique contribution of this paper lies in its analysis of the key role of institutional empowerment from a policy-side perspective, providing new evidence and insights for understanding how emerging economies can unleash the innovation potential of DC. It is worth noting that China’s experience can offer valuable lessons for other emerging economies, yet its applicability is contingent on their respective institutional and policy frameworks. Without effective governance and supporting policies, market forces alone are insufficient to fully unleash the innovation potential of DC.

5. Conclusions

Based on data from China’s A-share listed companies from 2008 to 2022, this study utilizes the quasi-natural experiment of the ICPP to systematically examine the impact of DC on CIA. The empirical results show that the ICPP significantly enhances CIA, a finding that remains consistent across various robustness checks, thereby validating the core hypothesis H1.

At the mechanism level, mediation effect analyses further verify three pathways: DC significantly boosts CIA by increasing government attention to science and technology talent (H2), promoting regional data elementization (H3), and facilitating corporate data assetization (H4). These results reveal the intrinsic logic of how DC influences CIA.

Heterogeneity analysis indicates that the policy effect is more pronounced in eastern regions, areas with higher government digital attention, and enterprises with sound management incentive mechanisms, highlighting the critical role of institutional environment and corporate governance in amplifying policy effects. Further research shows that the improvement in CIA driven by DC is mainly reflected in substantive innovation outcomes represented by invention patents, while its effect on strategic innovation is limited, underscoring its “quality-oriented” effect.

Overall, this paper verifies the significant positive impact of DC on CIA, reveals its mechanisms and contextual differences, and emphasizes its unique value in promoting high-quality innovation. This not only enriches research on the digital economy and corporate innovation but also provides new empirical evidence on how emerging economies can unleash innovation potential through DC.

6. Policy Implications

Based on the above research conclusions, this paper proposes the following recommendations:

First, continuously improve the information consumption pilot policy to strengthen its guiding role in corporate innovation. Empirical results show that DC can significantly enhance CIA, and with a more notable effect on substantive innovation. In future policy design, the government should adhere to systems thinking, optimize policy implementation pathways, and ensure the long-term and stable release of policy effects. On the supply side, it is essential to accelerate the construction of digital infrastructure and the market-oriented reform of data factors, reduce information barriers, and create an institutional environment conducive to the flow of innovation factors. On the demand side, efforts should be made to guide the upgrading of DC, cultivate new consumption formats, and transform market demand advantages into traction for enterprises to pursue high-quality innovation.

Second, optimize the policy structure to emphasize support for high quality innovation. Research finds that DC promotes substantive innovation more strongly than strategic innovation. The government should place greater emphasis on incentivizing innovation with high technological content and long-term value in the allocation of policy resources. For example, measures such as R&D subsidies, special talent funding, and long-term tax incentives can guide enterprises to allocate more resources to basic research and frontier technology breakthrough, avoiding the “short-termism” and “low-quality” tendencies in innovation activities.

Third, improve the policy transmission path to enhance the efficiency of effect transformation. Mechanism tests indicate that DC primarily promotes CIA through three paths: government talent attention, regional data elementization, and corporate data assetization. Therefore, at the policy level, focus should be placed on: firstly, continuously releasing signals of talent demand, improving mechanisms for talent introduction and cultivation, and enhancing the agglomeration effect of regional talent; secondly, accelerating the establishment of systems for data openness and circulation, improving supporting safeguard policies, and fully unleashing the value of data factors; thirdly, promoting the integration of data assetization into corporate development strategies, using data assets to alleviate financing constraints and improve resource allocation efficiency, thereby realizing a virtuous cycle of internal innovation.

Fourth, promote policy implementation based on local conditions to foster balanced regional development. Heterogeneity analysis shows that the policy effect is more significant in eastern regions, areas with high government digital attention, and enterprises with sound long-term incentive mechanisms. In this regard, policymakers should emphasize differentiated promotion across spatial dimensions: in central and western regions, fiscal support and investment in digital infrastructure should be increased to cultivate DC potential; in regions with a better foundation, the structure of policy incentives should be optimized, long-term incentive mechanisms strengthened, maintain the continuous innovation momentum of the enterprise. Simultaneously, experience exchange and resource sharing between regions should be promoted to narrow the digital development gap and achieve the inclusivity and balance of policy effects.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study is based on the quasi-natural experimental setting provided by the ICPP and has conducted an in-depth analysis of the impact of DC on CIA and its underlying mechanisms, drawing a series of conclusions that are of both theoretical and practical significance. However, the following limitations still exist:

First, limitations in variables and measurement. The model may suffer from omitted variable issues, such as unobservable characteristics like corporate digital maturity and managerial cognition, which could affect the estimation results. Additionally, some proxy variables used in this study have certain limitations. For example, while using software business revenue as an indicator of regional data elementization is reasonable, it may involve measurement bias. Furthermore, while the CIA metric dynamically captures corporate innovation activity comprehensively, firms may exaggerate innovation-related discourse for signal transmission purposes; thus, interpretations should be made with caution. Future research could introduce more alternative indicators (e.g., big data industry scale, cloud computing service revenue) and employ methods such as structural equation modeling to more systematically test multi-path mechanisms.

Second, limitations in sample and data scope. The sample of this study only covers Chinese listed companies, and the research window is limited, which may not fully reflect the policy effects over a longer time dimension. Future research could expand to include small and medium-sized enterprises, non-listed companies, and cross-national data to enhance the external validity and generalizability of the findings.

Third, room for methodological expansion. While this study primarily employs DID and mediation effect analysis methods, which can identify causal effects, it does not systematically compare heterogeneous effects across different countries or periods. Future research could further adopt methods such as quantitative meta-analysis to integrate cross-national empirical results and more comprehensively evaluate the varying impacts of DC under different institutional and market environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., S.D., W.Z. and J.W.; methodology, A.P., S.D., W.Z. and J.W.; software, A.P.; formal analysis, S.D.; validation, J.W.; investigation, W.Z.; data curation, A.P.; writing—original draft, A.P.; writing—review and editing, S.D., W.Z. and J.W.; supervision, W.Z.; project administration, S.D.; resources, W.Z.; funding acquisition, S.D. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China [grant number 20BRK005], the Nanchong Municipal Social Science Planning Project—Special Program on Youth Ideological and Moral Education [grant number NCQSN25B162], the Wuhan Polytechnic University Higher Education Research Project [grant number 2025GJKT001], and the Wuhan Polytechnic University University-Level Scientific Research Project [grant number 2025S80].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

These data are not publicly available for privacy protection reasons. If needed, one can request access to the data used in this study from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Sustainability Editors-in-Chief and the anonymous reviewers for their guidance and advice throughout the review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Word cloud of corporate innovation activity.

Figure A1.

Word cloud of corporate innovation activity.

Table A1.

Keyword Dictionary for Corporate Innovation Activities.

Table A1.

Keyword Dictionary for Corporate Innovation Activities.

| Category | Keywords |

|---|---|

| R&D Core | Research and Development, Development, Research, Tackle key technological problems |

| Innovation Concepts & Methods | Innovation, Creation, Invention, Iteration, Original, Pioneering, Innovativeness, Weed through the old to bring forth the new, Original creation |

| Outputs & Assets | Patent, Intellectual property, New product, Achievement |

| Technology & Materials | New energy, New materials, New technology, New processes, Brand-new |

| Strategic Change | Transformation, Reform, Change, Upgrade, Update, Revolution, Overcome |

| Collaboration & Models | Industry-academia-research collaboration, New model, New business forms, New approach |

| Descriptors | Emerging, High and new technology, New type, New generation |

Table A2.

List of Information Consumption Pilot Policy.

Table A2.

List of Information Consumption Pilot Policy.

| Year | Treated Group |

|---|---|

| 2013 | Beijing, Tianjin, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Ningbo, Xiamen, Dalian, Shijiazhuang, Qinhuangdao, Tangshan, Yongnian County of Handan, Taiyuan, Shenyang, Jilin City, Yanbian Prefecture, Changchun Jingyue High-Tech Industrial Development Zone, Harbin, Daqing, Changning District, Yangpu District, Nanjing, Yancheng, Zhangjiagang, Guangling District of Yangzhou, Hangzhou, Jinhua, Jiaxing, Hefei, Wuhu, Ma’anshan, Fuzhou, Shishi, Nanchang, Zhanggong District of Ganzhou, Weihai, Zibo, Jining, Weifang, Zhengzhou, Jiyuan, Wuhan, Xiangyang, Xiaonan District of Xiaogan, Zhuzhou, Hengyang, Chenzhou, Shantou, Zhuhai, Huizhou, Nanning, Liuzhou, Guilin, Haikou, Chengdu, Mianyang, Nanchong, Leshan, Xixiu District of Anshun, Honghuagang District of Zunyi, Yuxi, Baoji, Lanzhou, Jiayuguan, Xining, Golmud, Yinchuan, Karamay, Yining |

| 2014 | Shanghai, Baigou New Town, Changzhi, Ordos, Manzhouli, Benxi, Hunchun, Baicheng, Mudanjiang, Xuzhou, Suzhou, Shaoxing, Anqing, Bengbu, Quanzhou, Wuyuan County of Shangrao, Xinyu, Wendeng District of Weihai, Rencheng District of Jining, Luoyang, Xinxiang, Huangshi, Wuling District of Changde, Foshan, Beihai, Meishan, Guiyang, Dali, Baoshan, Xianyang, Baiyin, Dunhuang, Delingha, Wuzhong, Yuanzhou District of Guyuan, Korla |

Table A3.

Multicollinearity Test.

Table A3.

Multicollinearity Test.

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| DID | 1.16 | 0.858 |

| Size | 1.70 | 0.588 |

| Lev | 2.51 | 0.397 |

| ROA | 1.29 | 0.777 |

| TobinQ | 1.21 | 0.827 |

| Top1 | 1.09 | 0.919 |

| Intangible | 1.03 | 0.967 |

| Quick | 1.77 | 0.563 |

| RD | 1.01 | 0.990 |

| FirmAge | 1.35 | 0.742 |

Table A4.

Correlation Analysis.

Table A4.

Correlation Analysis.

| DID | Size | Lev | ROA | TobinQ | Top1 | Intangible | Quick | RD | FirmAge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DID | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Size | 0.095 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Lev | 0.012 * | 0.546 *** | 1.000 | |||||||

| ROA | 0.057 *** | −0.019 ** | 0.334 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| TobinQ | 0.038 *** | 0.315 *** | 0.305 *** | 0.246 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| Top1 | 0.042 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.130 *** | 0.091 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| Intangible | 0.023 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.035 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.043 *** | 0.054 *** | 1.000 | |||

| Quick | 0.018 ** | 0.348 *** | 0.645 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.205 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.111 *** | 1.000 | ||

| RD | 0.019 ** | 0.027 *** | 0.040 *** | 0.041 *** | 0.020 ** | −0.011 | −0.008 | 0.062 *** | 1.000 | |

| FirmAge | 0.182 *** | 0.204 *** | 0.142 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.066 *** | 0.111 *** | −0.003 | 0.146 *** | 0.027 *** | 1.000 |

Note: ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Table A5.

Keywords Used for Measuring Government Attention to S&T Talent.

Table A5.

Keywords Used for Measuring Government Attention to S&T Talent.

| Category | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Basic Research | Basic Research, Scientific Research, Applied Basic Research, Core Technologies, Basic Science, Cutting-Edge Technologies, Original Innovation, Key Technologies, Public Welfare Technologies, Originality |

| Sci-Tech Talent | Talent Resources, High-Level Overseas Talents, Overseas Returnees, Talent Team Building, Reform of the Science and Technology Management System, National Strategy for Reinvigorating China through Human Resource Development, National Strategy of Reinvigorating China through Science and Education, Scientific and Technological Achievements, Intellectual Property Rights, Scientific and Technological Innovation, High-Level Talents, Leading Talents, Innovation Teams, Talent Pool, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Research Personnel, Mass Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Innovation-Driven Development |

Figure A2.

Word cloud of corporate data assetization.

Figure A2.

Word cloud of corporate data assetization.