Abstract

New York State’s Regional Economic Development Councils (REDCs) were created to support sustainable, equitable, community-driven growth by distributing state funding across diverse regions. While allocations are geographically widespread, our research suggests that structural features of the REDC model may unintentionally reinforce disparities in local capacity and limit long-term impact, particularly in rural and under-resourced communities. This paper asks: To what extent does the REDC model reinforce or reduce disparities in economic development funding? Using qualitative system dynamics, specifically causal loop diagramming, and drawing on public data of RECD funding, interviews with municipal leaders, and public administration theory we examine systemic patterns that shape which municipalities repeatedly secure funding, and which remain excluded, identifying reinforcing and balancing processes that explain such systemic patterns. Key feedback structures include: the Capacity-Investment Loop, where high-capacity communities grow increasingly competitive over time; the Need-Funding Mismatch Loop, where administrative burdens block access for distressed communities; and the Collaboration Loop, which shows how competition can disincentivize shared regional strategies. These loops highlight how program structure—not just intent—shapes outcomes. Our findings suggest that, while the REDC model is intended to promote fairness and efficiency, it risks reproducing the disparities it seeks to address. Adjustments that strengthen regional collaboration, support capacity-building, and align funding with community need may help advance more inclusive and sustainable economic development.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development, as defined in the Brundtland Commission’s landmark report, is the process of meeting present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own [1]. This concept emphasizes the integration of economic well-being, environmental stewardship, and social inclusion, forming the basis of contemporary development policy worldwide. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have extended this vision, urging governments to promote inclusive and sustainable economic development, reduce inequality, and build resilient infrastructure (see https://sdgs.un.org/goals, accessed on 15 September 2025).

A core component of sustainable development is the pursuit of sustainable economic development—economic activity that not only drives productivity and income growth but also does so in ways that are socially inclusive and ecologically responsible. In practice, this umbrella often includes decarbonization and “green” investments (i.e., renewable energy and low-carbon infrastructure), but also the institutional capacity and governance conditions that allow communities—especially rural and under-resourced ones—to access, absorb, and steward investment over time. Our focus in this article is on these governance and capacity conditions as necessary enablers of sustainability, which in turn shape the feasibility and distribution of both green and non-green development projects. Achieving this development agenda requires more than market incentives or private-sector dynamism; it depends critically on the presence of supportive governance structures that can steer public investment, coordinate among stakeholders, and reduce structural inequities. In particular, the ability of rural and distressed communities to access development opportunities is often shaped by the capacity and responsiveness of regional and state institutions. Because of these reasons, governments have developed policy interventions that provide access to resources with the goal of promoting sustainable economic development [2,3]. In practice, the outcomes of these policies often diverge from their intended goals, shaped by complex systemic and institutional dynamics [3,4].

In this context, governance becomes a central enabling or constraining force [5,6]. Scholars of multi-level and polycentric governance have long argued that fragmented or overly centralized decision-making can hinder the design and implementation of effective development strategies [7]. Sustainable economic development depends not just on policy content but on institutional design: how decisions are made, who participates, and how resources are allocated across levels of government. Within the field of public administration, these ideas have been developed into a broader framework for understanding the success and failure of public policy implementation. Key concepts such as administrative capacity [8,9], institutional collective action [10], and administrative burden [11] help explain how structural features of governance systems impact the ability of programs to reach their intended beneficiaries.

New York State’s Regional Economic Development Councils (REDCs) constitute a public policy that provides a useful case study to explore how governance structures designed to promote equitable growth may produce uneven outcomes. The REDC initiative aims to decentralize economic development decision-making by empowering ten regional councils—composed of local stakeholders—to guide investment based on regional priorities (see https://regionalcouncils.ny.gov/about, accessed on 15 September 2025). Funding is awarded through a competitive process using the Consolidated Funding Application (CFA), in which applicants must demonstrate alignment with state and regional goals (see https://regionalcouncils.ny.gov/cfa/process-guide, accessed on 15 September 2025). In this way, we use this case study to answer the following research question: What are the main processes embedded in the REDC policy and governance system that hinder or promote sustainable economic development? Specifically, we ask whether REDC funding has reached high-need rural municipalities and addressed disproportionate economic challenges; supported sustainable rural entrepreneurship and local food systems; or fostered collaboration rather than competition among municipalities.

To explore this question, we apply causal loop diagramming (CLD)—a tool from system dynamics that consists of identifying feedback mechanisms driving observed patterns in complex systems [12,13,14]. CLD enables us to model how structural conditions such as administrative capacity, funding design, and collaboration incentives interact over time to reinforce or counteract disparities, informed by secondary data of REDC funding since 2011 as well as interviews with stakeholders. Our study contributes to the sustainability literature in three primary ways: (1) By applying causal loop mapping to the domain of regional economic development funding, we highlight how program design interacts with local capacity and structural constraints, offering a systems-based diagnosis of why certain communities succeed repeatedly in accessing REDC funding while others remain persistently locked out, (2) by integrating public administration theories—such as administrative burden [15], policy capacity [8], and collaborative governance [16]—we link sustainability literature with governance scholarship, and (3) by developing a conceptual model grounded in empirical data, we lay the groundwork for future simulation modeling to test interventions and explore leverage points. In doing so, we build on a growing body of research that uses qualitative system dynamics to uncover feedback dynamics within policy systems [17,18].

In what follows, we first review the literature on regional economic governance, administrative burden, and equity in public investment. We then outline our methodological approach and present a causal loop analysis of New York’s REDC system, drawing on public data and interviews. Finally, we discuss the policy implications of our findings and suggest avenues for policy reform and further research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Economic Development Through a Public Administration Lens

Sustainable economic development concerns how economies generate prosperity while protecting ecological systems and expanding human capabilities and inclusion. This requires more than capital formation or project pipelines; it hinges on institutional arrangements—rules, roles, and capacities—that enable communities to access resources, coordinate action, and steward assets over time. In practice, this means complementing physical investment (infrastructure, firms, technology) with social and administrative infrastructure (planning, data, grant management, intergovernmental coordination, accountability). This is particularly true in rural and historically under-resourced communities, where gaps in staffing, planning resources, and access to financial capital limit participation in development programs [19,20].

A growing strand of sustainability scholarship emphasizes that governance quality is a first-order condition for durable outcomes: polycentric and multi-level arrangements can improve fit to local conditions, but only when actors have the capacity to participate and mechanisms for coordination and learning exist [7,21]. Likewise, sustainability depends on procedural and distributive equity—who can enter the process, shape priorities, and secure resources—not only on end-state environmental indicators. For rural and under-resourced places, deficits in staffing, planning expertise, and fiscal flexibility translate into binding capacity constraints that limit participation in development programs and slow adoption of both green and non-green innovations.

Seen through this lens, “green” investments in renewables, efficiency, resilient infrastructure, and local food systems are one subset of sustainable economic development; their feasibility and distribution still rest on governance preconditions—administrative capabilities, collaborative institutions, and fair rules for allocating funds. Where institutions lower coordination costs, share knowledge, and recognize differentiated needs, communities can absorb investment and sustain benefits. Where rules emphasize competition and project-by-project feasibility without capacity support, funding may be spatially widespread yet institutionally uneven, undermining long-term resilience.

In the REDC context, this perspective motivates our focus: we analyze how program design and administrative capacity shape access to state development resources as a prerequisite for sustainable outcomes. Rather than evaluating environmental performance directly, we examine the institutional pathways—capacity-building, collaboration, and equitable allocation—through which regions (especially rural ones) can translate investment into enduring prosperity and resilience.

2.2. Governance Structures and Institutional Design for Collaboration (Or Competition)

Effective regional development is rarely achieved through centralized decision-making alone. Scholars of multi-level and polycentric governance have shown that overlapping authorities, jurisdictional fragmentation, and lack of coordination can stifle local innovation and limit the responsiveness of regional policy [7,21]. Governance structures influence who participates in decision-making, how priorities are set, and whether institutional incentives encourage collaboration or competition. Feiock [10] explains interlocal collaboration as a problem of coordinating autonomous governments that face transaction costs, uncertainty, and defection risk. In fragmented metropolitan and regional settings, municipalities weigh expected benefits of joint action against the costs of negotiating, monitoring, and enforcing agreements, and often under asymmetric capacities and political incentives. Interlocal collaboration emphasizes the role of institutions (and their formal rules, repeated interactions, third-party brokers, and credible commitments) in lowering coordination and enforcement costs, creating reciprocity, and aligning payoffs so that collaboration becomes individually rational. Where rules and incentives make benefits zero-sum or amplify uncertainty, jurisdictions rationally pursue competitive, go-it-alone strategies; where institutions reduce risk and create shared gains, cooperation is more likely to emerge and persist.

Collaborative governance theory further emphasizes the role of trust, institutional alignment, and administrative infrastructure in supporting shared regional agendas [16,22]. For example, Ansell & Gash [16] argue that successful collaborative governance requires trust, shared goals, and institutional incentives for cooperation. Similarly, Bouckaert & Van de Walle [23] emphasize that perceptions of fairness in government processes are central to institutional trust; and Frederickson’s [24] argument for public equity further reinforces that fair access to public investment requires proactive, need-based distribution strategies—not simply equal opportunity to compete. Agranoff & McGuire [25] argue that interorganizational networks enable municipalities to pool resources, information, and expertise in ways that individual jurisdictions cannot achieve alone. They emphasize the managerial work of collaboration—the hard work of activating partners, framing shared problems, mobilizing resources, and synthesizing efforts—often through boundary-spanning “brokers” who connect agencies and communities. Effective networks reduce duplication, spread administrative workload, and speed knowledge transfer across jurisdictions, thereby expanding the de facto capacity of smaller governments. At the same time, networks entail transaction costs, require trust and credible commitments, and benefit from enabling rules and supportive performance systems. Where these conditions are present, networked governance can transform fragmented local efforts into coordinated regional action, improving access to external funding and implementation follow-through [25].

Finally, although regional development theory increasingly promotes collaboration, many funding systems continue to reward competition. When municipalities must compete for a limited pool of funds—without incentives for joint planning—they may view neighboring communities as rivals rather than partners. This undermines trust, leads to redundancy of efforts and projects, and can fragment efforts to build regional capacity [10,26].

In this way, REDCs were designed to foster regional collaboration by bringing together diverse local actors to shape state investment priorities. However, the design of the funding process—especially the dominant role of state agency scoring and competitive selection—may inhibit genuine regional governance, limiting the potential for locally driven strategies to emerge. In other words, the lack of structural incentives for joint applications, shared funding, or collaborative metrics limits the practical realization of these goals. As a result, municipalities often default to individual applications and protect local interests, particularly when success rates are low and future eligibility is constrained. This reinforces fragmentation and weakens the long-term sustainability of regional planning.

2.3. Administrative Capacity and Burden

The ability of municipalities to access funding is shaped not only by their need, but also by their capacity to plan, apply for, and implement projects. Public administration research has long emphasized the uneven distribution of institutional capacity, noting that smaller municipalities often lack full-time planners, grant writers, or financial officers who can navigate complex funding programs [8,9,10]. Pressman and Wildavsky [27] describe how bureaucratic complexity and administrative burden create implementation failures, preventing well-intentioned policies from reaching their intended beneficiaries [27]. In this paper, we refer to policy and administrative capacity as intertwined elements of institutional readiness—particularly in the context of securing and managing external funding.

The administrative burden framework developed by Moynihan, Herd, and Harvey [15] and subsequently expanded [28] describes how learning, compliance, and psychological costs shape access to public programs. While their work focuses on individual beneficiaries, these same mechanisms apply at the municipal level, where small governments face disproportionately high burdens in applying for competitive grants. In the REDC model, these burdens manifest in the requirement to produce feasibility studies, coordinate with multiple agencies, and align with both state and regional strategies—barriers that disproportionately disadvantage communities with limited staff and technical capacity.

2.4. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

Fundamental to the REDC process—and to economic development efforts throughout the world—is a single core value: create jobs. In the case of New York State’s funding model, the goal is to both create jobs and to build (or expand) firms. These efforts are well-supported; the entrepreneurial ecosystem literature suggests that regional economic sustainability depends on coordinated support across multiple domains: infrastructure, financial access, education and training, and institutional stability [29,30]. Stam [31] argues that thriving entrepreneurial ecosystems require both financial investment and institutional support. Funding alone is insufficient—without strategic planning, infrastructure investment, and workforce development, local business growth remains limited. Similarly, Peters & Fisher [32] caution that many economic development programs overemphasize short-term metrics (e.g., jobs “created” in the first year) rather than long-term economic transformation.

However, many state-level funding mechanisms—including New York’s REDC model—prioritize individual project feasibility over systemic ecosystem development, potentially undermining longer-term resilience [5,33]. In the REDC context, this means that while projects may be evaluated on job creation or investment potential, they are not necessarily assessed for their contribution to broader, sustainable regional transformation.

3. Methods and Data

This study is part of a broader research effort aimed at evaluating whether the REDC model has achieved its intended policy goals, particularly in the context of rural development. Specifically, we ask whether REDC funding has reached high-need rural municipalities and addressed disproportionate economic challenges; supported sustainable rural entrepreneurship and local food systems; or fostered collaboration rather than competition among municipalities.

3.1. Research Approach and Justification

System dynamics has long been recognized as a powerful tool for policy analysis, particularly when addressing complex socio-economic systems [13,34,35]. Unlike purely statistical models, causal loop diagramming (CLD) enables researchers to capture dynamic feedback structures that may remain obscured in traditional regression-based approaches. In system dynamics, reinforcing loops (R) describe feedback processes that amplify change over time, producing cycles of cumulative growth or decline, while balancing loops (B) prevent change, stabilizing the system around a given state that many times is often the result of stakeholders’ goals or resource limits. CLDs are particularly useful for identifying these feedback structures that influence long-term outcomes across interdependent variables [36,37].

This study employs qualitative causal loop diagramming as a system dynamics methodology to analyze the structural dynamics embedded within New York State’s Regional Economic Development Council (REDC) funding model. The goal is to uncover feedback structures that contribute to understanding the current performance and challenges of the system. CLD has been increasingly applied in sustainability and public administration research, including efforts to explore service delivery barriers [17] and governance in urban–rural systems [18], and sustainable development [38]. This approach offers a holistic systems perspective on the challenges and opportunities within the REDC framework, blending qualitative mapping with supporting empirical analysis.

3.2. Data Sources and Analytical Process

The causal loop analysis was informed by a combination of quantitative data and qualitative insights from stakeholder interviews. This mixed-methods approach strengthens the validity of our findings by grounding systemic patterns in both empirical evidence and practitioner experience.

Quantitative Data: We analyzed a publicly available database of REDC-funded projects, comprising over 10,300 records from 2010 to 2022. This dataset was used to identify trends in funding distribution, project types, and municipal success rates. Statistical summaries helped shape key variables in the causal loop structure.

Our analysis uses REDC award data from 2010 to 2022 (figures shown for 2011–2022, the first full year after REDC launch). We deliberately truncate at 2022 for two reasons: (1) there is a posting lag between award decisions and appearance in the public repository, creating incomplete coverage for the most recent cycles; and (2) many awards require multi-year contracting and implementation, so including 2023–2025 would mix in projects not yet executed or comparable. Limiting to 2022 maximizes data completeness and comparability across regions and years.

Qualitative Data: We have reviewed strategic documents and annual reports from 4 of the REDCs, those that include more extensive rural areas. We have also attended and observed REDC planning meetings.

Stakeholder Interviews: We have conducted 12 semi-structured interviews with municipal leaders, economic development professionals, and REDC participants. These interviews provided context-specific insights into administrative burdens, collaboration barriers, and perceptions of fairness and effectiveness. This data collection process is ongoing and approved following the processes of the University at Albany Institutional Review Board.

Iterative Model Refinement: Loop structures were developed through an iterative process of modeling, validation, and revision. Initial diagrams were informed by theory and data analysis, then refined based on interview feedback and internal review to ensure representational accuracy and relevance.

This study is exploratory and conceptual in nature, and follows well-established practices in qualitative system dynamics, where causal loop diagrams serve as a tool for conceptual modeling, informed by stakeholder input and theoretical synthesis [12,39,40]. As is typical of exploratory CLD studies, loop boundaries reflect interpretive choices based on relevance to the research question [41]. While such diagrams are useful for uncovering systemic structures, they require further development and simulation to test behavioral implications and evaluate policy alternatives; specifically, the causal loop diagrams presented here are qualitative representations of systemic patterns and do not include quantified relationships or predictive simulation. Loop boundaries reflect interpretive judgments and may exclude factors outside the focus of REDC design and implementation. While our findings are grounded in data and practitioner input, future work is needed to test and validate these feedback structures through simulation or comparative analysis.

4. Case Study Context: New York’s REDC Program

4.1. Case Overview

The REDC model was launched in 2011 as a signature initiative to decentralize New York State’s economic development strategy. The state was divided into ten regions, each led by a Regional Economic Development Council comprising local stakeholders from the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. The goal of the REDCs is to guide investment by identifying regional priorities, improving coordination, and fostering inclusive, place-based growth. Strategic planning in the regions is coordinated by Empire State Development (ESD), a New York State agency in charge of economic development. ESD provides procedural guidelines for consulting stakeholders in the region, establishing strategic goals, reporting, and assessing progress within the region. Following this guidance, regional strategic plans have been revised periodically (about every 5 years) to keep them current and relevant to the regions.

Projects are submitted through a Consolidated Funding Application (CFA), which allows applicants to apply for multiple funding sources through a single portal. Project proposals are scored primarily by state agencies (accounting for 80% of the decision weight), with REDC members offering additional input based on alignment with regional strategies and goals (accounting for 20% of the decision weight).

4.2. Description of REDC Projects

REDC awards span a broad portfolio of development priorities reflecting the state’s economic and community objectives. Business development and site readiness projects typically involve facility build-outs, industrial sites, and equipment modernization designed to attract or retain employers. Workforce development initiatives support training programs, apprenticeship networks, and partnerships with educational institutions to strengthen regional labor pipelines. Community and downtown revitalization projects include main street improvements, brownfield redevelopment, and placemaking efforts aimed at stimulating local investment. Tourism and cultural asset projects enhance visitor infrastructure and preserve heritage and arts venues that contribute to regional identity. Agriculture and local food system investments target farm modernization, food processing, and distribution infrastructure, while housing and community infrastructure projects address water, sewer, broadband, and neighborhood improvements. Finally, energy and environmental initiatives promote renewable generation, efficiency, grid resilience, and land or water conservation. These categories illustrate how REDC funding is structured to support both economic competitiveness and community well-being across sectors.

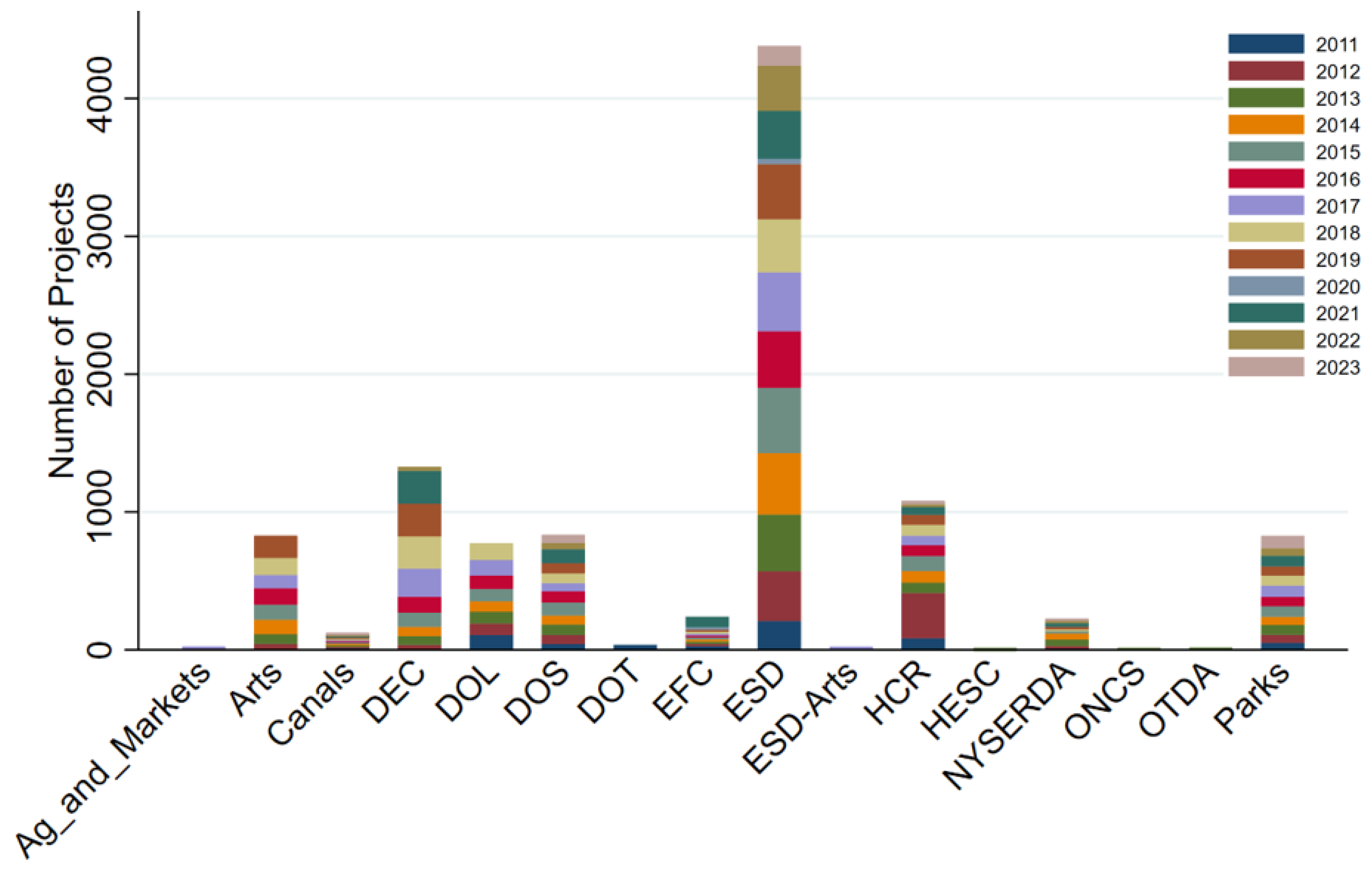

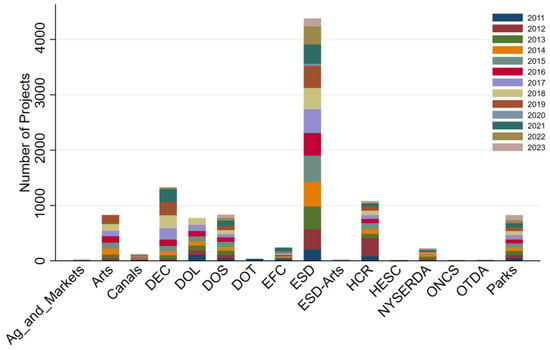

Figure 1 presents the distribution of projects by agency between 2011 and 2023. During this period, a total of 10,734 projects were implemented across 16 state agencies. Among these, the Empire State Development (ESD) agency accounted for the largest number of projects, 4380 projects (40.8%). This was followed by the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) with 1327 projects (12.4%), the Homes and Community Renewal (HCR) with 1080 projects (10.1%), and the Department of State (DOS) with 834 projects (7.8%). In contrast, agencies such as the Department of Transportation (DOT), Agriculture and Markets, and the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA) accounted for less than 1% each. Overall, the results show that project implementation from 2011 to 2023 was highly concentrated within a few major agencies, particularly ESD, DEC, and HCR.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Projects by Agency, 2011–2023.

It is important to mention that, over time, New York State has evolved its economic development toolkit alongside the REDC process. In addition to agency-aligned grants, the state has introduced place-based, bundled awards that package multiple projects under a locally developed plan. Programs such as the Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI), and more recently the New York Forward program, emphasize coordinated, multi-project implementation and explicitly extend eligibility to smaller municipalities. These bundles aim to reduce fragmentation, align investments with a shared local strategy, and simplify sequencing (planning, site, infrastructure, activation) compared to one-off project awards. In this paper, we do not assess the outcomes of these programs; rather, we treat them as part of the broader governance context within which municipalities assemble capacity, collaborate regionally, and compete for limited funds.

4.3. Evaluation of the REDC Process

The extent to which the REDC model has been systematically evaluated is difficult to assess. New York State provides open access to data through the CFA portal, where a short description of all funded projects is publicly available. Additional economic development initiatives are documented in the state’s Database of Economic Incentives, which includes broader investment programs beyond REDC oversight. These platforms offer detailed information about the number of projects funded, dollar amounts awarded, and jobs created or retained across economic development regions. While these indicators are useful for tracking investment and performance metrics, they do not fully reflect whether REDC investments have fulfilled the model’s foundational principles—placemaking, workforce development, leveraging tradeable sectors, and innovation. Nor is there sufficient evidence to determine whether these investments have led to sustained improvements in local economic vitality, particularly in distressed or rural communities.

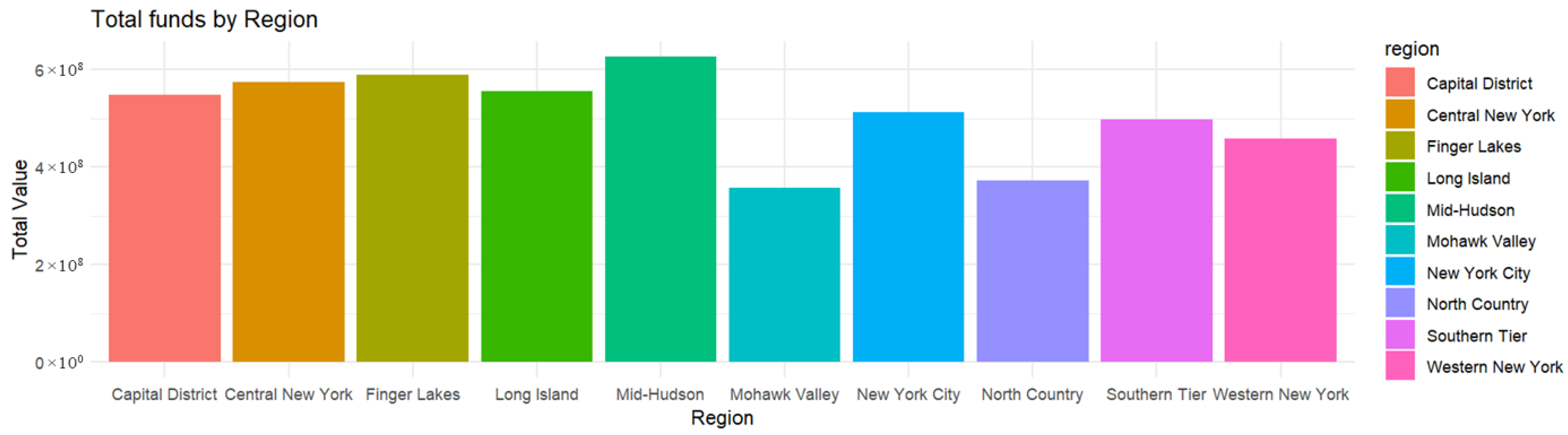

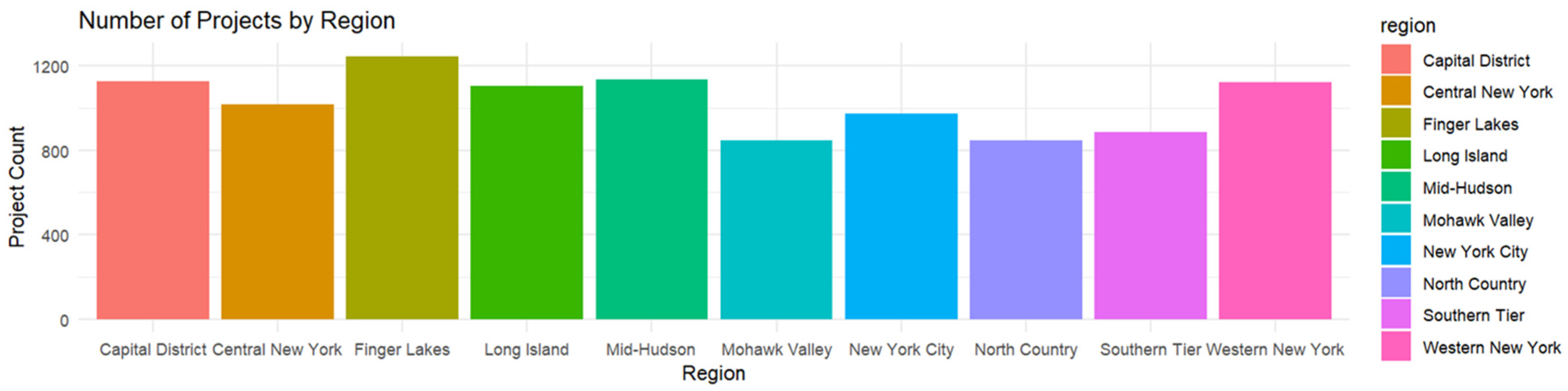

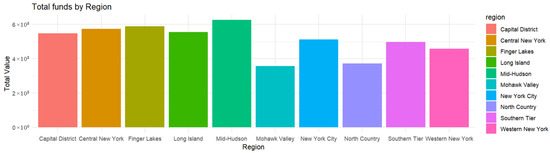

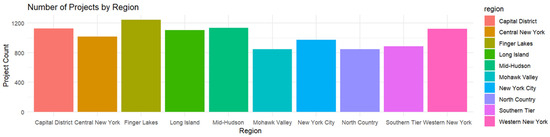

Our analysis of these public data (shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3) reveals that while REDC funding has been broadly distributed across regions, and has targeted both job creation and business development, this equal allocation has not necessarily resulted in equitable outcomes [42]. Many rural communities continue to face business closures, limited infrastructure investment, and stagnant economic performance. Even when these communities secure funding, administrative burdens related to project management and reporting as well as market constraints often limit their ability to successfully implement and sustain projects.

Figure 2.

REDC funding in New York State distributed over regions as measured by total funding, 2011–2022.

Figure 3.

REDC funding in New York State distributed over regions, as measured by number of projects awarded, 2011–2022.

We have observed that projects involving intermunicipal collaboration are not frequent, as they depend on the availability and effectiveness of county-level entrepreneurs either in the public or the private sector. Even when projects have broader regional relevance, smaller or underfunded municipalities frequently face repeated rejections, exacerbating frustration and disengagement from the process.

This analysis suggests that REDC’s spatially balanced funding approach may obscure an underlying need-funding mismatch. To investigate these dynamics more deeply, we employ causal loop analysis to model the structural conditions that may reinforce existing disparities or offer pathways toward more resilient and inclusive regional development. Moreover, key features of the REDC model, such as its reliance on agency scoring, the competitive nature of awards, and the absence of formal mechanisms to support collaboration, create structural dynamics that may reinforce regional inequality rather than reduce it. Understanding these dynamics requires a systemic lens, which causal loop mapping is well-suited to provide.

5. Results

5.1. Overview

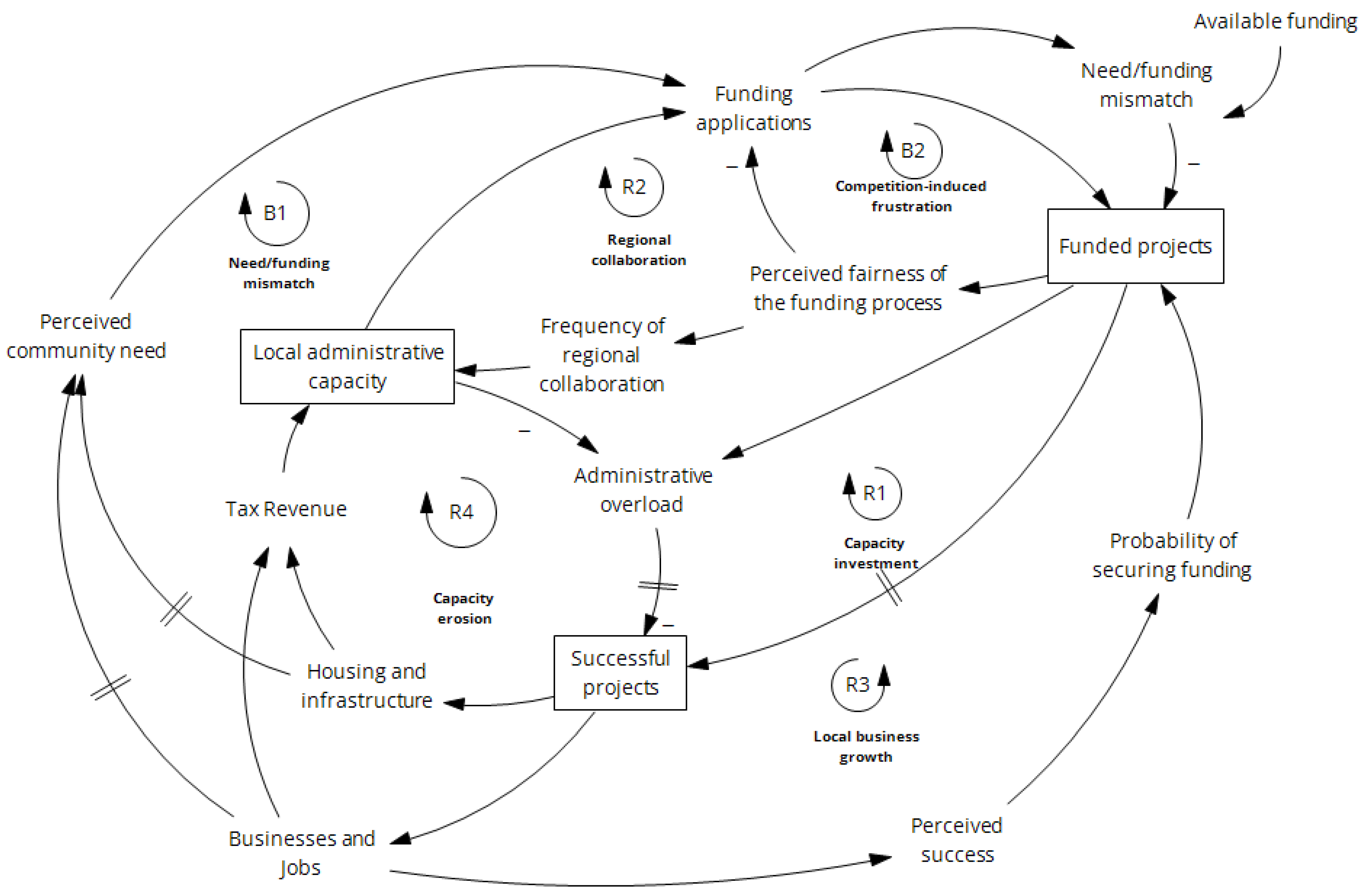

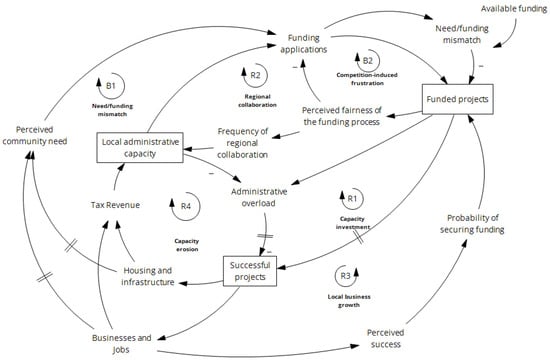

Figure 4 provides an overview of the key reinforcing and balancing feedback loops shaping the outcomes of the REDC funding model. The figure provides a visual tool to identify structural drivers of funding success and failure, exploring why certain municipalities repeatedly secure funding while others struggle to break into the cycle, and why some regions are persistently under-resourced. At the core of this model is the interplay between local administrative capacity, funding success, regional collaboration, and economic outcomes. The REDC process was designed to distribute funding equitably across regions, yet the system itself contains feedback mechanisms that inadvertently reinforce disparities rather than resolve them.

Figure 4.

Overview of the conceptual model of REDC funding in New York State. Figure follows system dynamics conventions for CLDs. Only negative causal connections are marked in the Figure (-); all other causal connections are positive. We use a double line crossing a causal connection (||) to denote a delay.

The model consists of five key feedback loops that explain these dynamics (explained further in Section 5.2,Section 5.3,Section 5.4,Section 5.5,Section 5.6,Section 5.7):

- Capacity-Investment Feedback Loop (R1): High-capacity communities continuously secure funding, increasing their long-term administrative strength and future competitiveness.

- Need-Funding Mismatch Loop (B1): High-need communities apply for funding but are often unsuccessful, leading to persistent underinvestment in the most vulnerable areas.

- Competition-Induced Frustration Loop (B2): When funding is scarce and many municipalities are unsuccessful, especially those with fewer resources, perceptions of unfairness can grow—discouraging future participation in the program.

- Regional Collaboration & Administrative Capacity Loop (R2): Strong regional cooperation can extend administrative capacity, improving a municipality’s ability to secure funding.

- Local Business Growth Loop (R3): Successful projects can foster long-term economic vitality, but if projects are short-lived or underfunded, they fail to generate sustained business and infrastructure growth.

- Capacity Erosion Loop (R4): Low-capacity communities experience a reinforcing cycle of administrative overload and, eventually, a reduced ability to compete for funding.

These feedback processes interact to reinforce economic disparities across regions. Municipalities with high administrative capacity continue to have better chances of winning funding, while those with low capacity remain at a position of disadvantage with fewer chances to be funded. Meanwhile, the prioritization of spatial fairness over need-based allocation results in a funding model that may appear equitable on the surface but fails to address underlying economic vulnerabilities.

The following sections examine each of these loops in detail, illustrating their systemic effects and drawing connections to public administration literature to provide additional context.

5.2. Capacity-Investment Feedback Loop (R1)

One of the most significant reinforcing loops in the REDC system is the Capacity-Investment Feedback Loop (R1), which illustrates how high-capacity communities repeatedly secure funding, further strengthening their administrative capacity and competitiveness over time. This loop helps explain why some municipalities continuously succeed in obtaining funding while others struggle to break into the cycle.

The dynamics suggest that as local administrative capacity increases, communities gain enhanced skills and support—they are more prepared to effectively secure funding. These are tangible effects: municipalities with well-developed administrative teams and grant-writing expertise are more likely to prepare competitive funding applications and manage challenges like securing monetary match requirements. They also tend to better understand the bureaucratic requirements, scoring criteria, and necessary feasibility studies, making them better positioned to succeed.

With greater preparedness, communities are more likely to be successful in their funding attempts. Often, participants are aware of this, and in qualitative interviews, they describe how they leverage partnerships with neighboring communities, with their local industrial development authorities, with aligned nonprofit actors and with private sector consultants in order to make their applications more competitive. Scholars suggest that well-prepared municipalities experience higher success rates in these types of competitive applications, receiving a greater share of available funding [9,26,43,44,45,46]. Moreover, when communities successfully secure funding, they tend to invest (to varying degrees) in their own local capacity to secure more funding. One of the interviewees, when asked if his town would be capable of managing a 4.5-million-dollar New York Forward grant, stated that it would be difficult, but that they would find assistance. Funds allow municipalities to hire and retain skilled staff, develop professional grant-writing expertise, and establish internal planning processes that further strengthen their competitive advantage. With a more robust administrative capacity, they become more competitive for future funding. As municipalities continue to build expertise, they become even more competitive in subsequent funding cycles, creating a self-reinforcing loop of success.

This reinforcing dynamic aligns with Feiock’s [10] Institutional Collective Action Framework, which explains how institutional constraints and governance structures favor well-resourced communities, reinforcing disparities over time. This process reflects the Matthew Effect [47,48], where those with existing advantages continue to accumulate more resources, while those with fewer resources struggle to break into the funding cycle. During a recent conversation with a rural town supervisor, he was blunt in his assessment of the political process, suggesting that to be successful, you need to golf with the right lawmakers.

In practical terms, this means that municipalities with existing capacity continue to grow stronger, while underfunded municipalities remain locked out of funding cycles, further exacerbating disparities between regions. It is also a prime example of the “success to the successful” archetype, frequently referenced in the system dynamics field [49]. Sociologist Leonard Beeghley advanced the conversation about the Matthew Effect still further, suggesting that those whose initial conditions predispose higher economic positions will likely continue to secure economic advantages; those who start off poor will struggle to advance [48]. This feedback process is also relevant in the case of local food systems governance [50]. While starting conditions are rarely prioritized in the literature, they seem to play an outsized (and powerful) role in determining whose food systems are resilient, and those for whom food deserts are the norm. These dynamics introduce challenges, and under-resourced municipalities struggle to break into this cycle due to their lack of dedicated administrative capacity, making it difficult for them to compete effectively for REDC funds.

5.3. Need-Funding Mismatch Loop (B1)

One of the primary balancing loops in the REDC system is the Need-Funding Mismatch Loop (B1), which explains why high-need municipalities do not necessarily receive funding, even when their economic conditions suggest they should be prioritized. This structural barrier perpetuates economic disparities by ensuring that some of the most vulnerable communities remain persistently underfunded.

Interviews with stakeholders and analysis of REDC data suggest that as perceived community need increases, municipalities are more likely to submit funding applications. This finding is both intuitive and consistent with previous scholarship [51]. When economic conditions deteriorate–such as through high unemployment, lack of infrastructure, or declining business activity–municipal leaders recognize an urgent need for external investment and turn to REDC funding to support critical development projects. However, while rising need drives more applications, the total pool of REDC funding remains relatively fixed. Our analysis (Figure 2 and Figure 3) shows that annual allocations vary little from year to year, regardless of shifts in demand. As a result, an increase in applications leads primarily to greater competition among municipalities, rather than a proportional increase in resources. This competition does not reward need alone. Funding allocations tend to favor high-capacity communities because state agencies evaluate projects based on feasibility and readiness, rather than economic need. Stakeholders noted that awards increasingly hinge on technical documentation such as engineering and technical readiness reports. While this emphasis disadvantages under-resourced municipalities, the state’s rationale is not without merit: several interviewees acknowledged cases where awardees struggled to spend funds due to not being capable of spending the allocated money, either due to struggles with matching funds, management and administration of funds, or because they were forced to utilize the money on a reimbursable basis. In contrast, high-capacity municipalities (from R1—Capacity Investment Loop) are better equipped to submit stronger applications, secure matching funds, navigate complex administrative systems, and demonstrate acceptable outcomes–further reinforcing their advantage.

Concerningly, low success rates for high-need communities mean that the need persists or worsens. This consequential delay is fundamental to the argument made in Pressman and Wildavsky’s [27] study of implementation, discussed earlier. Similarly, the REDC funding model—despite its goal of supporting regional economic growth—often fails to deliver investment where it is needed most. The structural barriers embedded in the application and selection process lead to a mismatch between economic need and actual funding allocations, reinforcing economic stagnation in under-resourced municipalities. Interview participants frequently share with us that they have persisted through 4, 5, and even 6 rounds of funding for projects before getting awarded; others admit that they gave up and stopped submitting requests. Unsuccessful applicants do not receive the economic boost they need, which leaves them in a continued state of underdevelopment. This leads to a reinforcing cycle where economic distress remains high (and growing), but funding remains out of reach, fueling further economic stagnation.

This has important implications for the equity vs. equality debate in contemporary public administration. This loop underscores the fundamental misalignment between need-based funding and equal distribution models, a key debate in public administration and public finance. Frederickson [24] highlights that equity—not equality—should guide public policy. Equity means allocating resources in proportion to need. Equality means distributing resources evenly, regardless of need. The REDC model leans toward equality in distribution, leading to inefficiencies where high-need communities remain underserved. Furthermore, Moynihan et al. [15] describe administrative burden as a key barrier to equitable access to government resources, highlighting how learning, compliance, and psychological costs shape individual interactions with bureaucratic systems. While their framework focuses on individual burdens, the same dynamics apply at the municipal level, where under-resourced communities struggle to navigate complex application processes, meet eligibility requirements, and repeatedly face rejection. These administrative burdens reinforce disparities in REDC funding, ensuring that high-capacity municipalities maintain a competitive edge while lower-capacity municipalities remain locked out of funding cycles. Thus, the Need-Funding Mismatch Loop (B1) exposes a critical policy gap: Funding is not necessarily allocated to the places where it is needed most; instead, it goes to the places best equipped to win it.

This loop provides a strong policy rationale for reforms that shift REDC allocation models from competitive, capacity-driven processes toward more need-based, equity-focused investment strategies; for under-resourced communities, this means that we need to do a better job at equipping them to win. This is increasingly supported in the literature. Through a resilience lens, strengthening more potential participants (our REDC applicants) is found to be a more robust and durable policy, as it favors diversification, redundancy (e.g., in connections with other entities), and innovation [52].

5.4. Competition-Induced Frustration Loop (B2)

One of the unintended consequences of REDC’s competitive funding model is that as the backlog of unsuccessful applicants grows, municipalities perceive the process as unfair, fostering competition rather than collaboration. The Frustration Loop (B2) explains how repeated rejection erodes trust in the system, discouraging future applications for funds.

Our interviews with stakeholders suggest that as more municipalities apply for funding, the reality is that most applications are unsuccessful. Exacerbating the situation, as economic conditions worsen (either because of macro-level economic conditions or because repeated cycles of unfunded proposals allow circumstances to deteriorate), more municipalities apply for REDC funding. Since the funding pool is limited, many applicants fail each cycle, adding to a growing backlog of unsuccessful applicants.

In this loop, we highlight how increasing funding applications (implying a high rejection rate), erodes the perceived fairness of the process among applicants. For example, interviews suggest that recipients become more likely to question scoring rubrics and blame party politics. Frustration builds, particularly among high-need communities that feel repeatedly overlooked. This loop and trust erosion may discourage intermunicipal collaboration, working in conjunction with the feedback loop R2. Unfortunately, one of the factors that tends to support better outcomes for regions is active and supportive collaboration. When municipalities view each other as competitors rather than partners, they are less likely to engage in cooperative planning efforts and form multi-municipal project proposals, and choose to work in isolation, fearing that helping a neighbor may reduce their own chances of winning funding.

Reduced regional collaboration does not just impact outcomes; it is likely to produce weaker applications and further exacerbate competition. Without regional collaboration, individual municipalities submit weaker, uncoordinated applications, making it harder to demonstrate regional impact and making the process of securing funding even more difficult.

This loop reflects key insights from collaborative in governance literature, which suggests that principles of trust, shared goal-setting, agenda formation and collective action. However, in the REDC model, competition-based funding erodes these elements, discouraging municipalities from forming regional coalitions. The REDC system’s repeated rejection of applicants, particularly in high-need areas, undermines trust in the process, making municipalities less likely to engage with REDC planning in future years.

Thus, rather than encouraging regional economic cooperation, the competition-induced frustration loop drives fragmentation, making it harder to achieve meaningful economic transformation. The competitive structure of REDC funding discourages municipalities from pooling resources, which weakens applications and leads to duplicated efforts. As the backlog of unsuccessful applicants grows, overall trust in the funding process declines, further reducing participation in collaborative planning.

Policy interventions should introduce incentives for regional partnerships, ensuring that municipalities see collaboration as an advantage rather than a risk. While there is room within the current REDC structure to support regional partnerships, it remains an under-recognized opportunity.

5.5. Regional Collaboration & Administrative Capacity Loop (R2)

While competition for REDC funding often discourages municipalities from working together, regional collaboration has the potential to extend administrative capacity, improving funding success rates and long-term economic development outcomes. The Regional Collaboration & Administrative Capacity Loop (R2) explains how cooperative strategies, if they are encouraged, can help under-resourced municipalities overcome barriers to funding acquisition.

When there is a healthy growth of regional collaboration, outcomes include more robust local administrative capacity. Municipalities that form coalitions and share resources can jointly apply for REDC funding, reduce individual administrative burdens, and submit stronger applications. Ideally, this allows smaller municipalities to leverage expertise from better-resourced partners, improving their chances of securing funding. Collaborative efforts help municipalities navigate complex application requirements, complete feasibility studies, and present regionally integrated proposals that appeal to REDC evaluators. And, as a result, funding success rates increase, particularly for historically underfunded areas.

As municipalities experience positive outcomes from collaboration, they become more likely to engage in regional partnerships in future funding cycles. This reinforces the cycle of administrative strengthening, reducing disparities in funding access over time. Incidentally, this loop suggests that regional collaboration may have some effect on addressing the unmet needs of historically under-resourced regions.

This loop aligns with key insights from public administration and collaborative governance literature [10]. Similar to the earlier loop (B2) evidence suggests that regional collaboration reduces institutional barriers to economic development by pooling administrative resources and reducing duplication of effort. The REDC model currently lacks strong incentives for coordinated economic planning across municipalities, limiting the effectiveness of development initiatives; still, we can imagine different outcomes if the situation included such strong incentives for cooperation. Similarly aligned with Agranoff & McGuire [25] our findings suggest that the REDC’s competitive framework, while not actively discouraging networked governance, does little to prevent fragmentation.

However, Current REDC funding mechanisms do not sufficiently reward collaboration, discouraging municipalities from pursuing regional strategies. Therefore, policies that offer deeper support to under-resourced municipalities that need technical assistance and policy incentives to engage in cooperative economic development efforts, would likely be fruitful. This loop provides a clear case for strengthening regional collaboration in the REDC process, ensuring that economic development funding is not just distributed fairly, but also leveraged effectively to maximize long-term impact.

5.6. Local Business Growth Loop (R3)

A core justification for REDC funding is that it should generate long-term economic benefits, particularly by supporting local business development and job creation. However, not all funded projects lead to sustained economic growth. The Local Business Growth Loop (R3) captures the reinforcing cycle where successful economic projects contribute to ongoing business activity, while failed or misaligned projects leave municipalities dependent on future funding cycles.

As more economic development projects are funded, more local businesses are formed or sustained and more jobs are created or saved. With this in mind, REDC funding is intended to stimulate local entrepreneurship, business expansion, and commercial infrastructure. And when investments align with community needs, businesses benefit from improved economic conditions, workforce availability, and infrastructure upgrades. As there is a more robust entrepreneurial ecosystem and thriving business sector, there are more jobs and greater perceived community well-being. Thriving businesses generate local employment opportunities, increase consumer spending, and boost municipal tax revenues.

This tends to lead to greater reinvestment in public services and business-friendly policies, and as businesses become financially self-sustaining, they contribute more to local economies. Successful local economies attract further investment, reinforcing a cycle of prosperity. However, there is a reciprocal to this loop: if funding is allocated to projects that are not well-matched to business needs, businesses may fail to see lasting benefits. Temporary job creation (e.g., construction projects) does not necessarily translate into sustained business growth. Without long-term planning, municipalities remain dependent on securing new funding, rather than fostering self-sustaining economic ecosystems [31,32]. If REDC funding prioritizes project completion over sustainable impact, the model risks reinforcing cycles of dependency rather than fostering lasting business growth.

Thus, R3 highlights a critical challenge: Does REDC funding generate long-term economic resilience, or does it simply create short-term project-based activity that fades over time? Funding metrics should shift from measuring project completion to evaluating long-term business sustainability. And in the case of New York’s REDCs, they should consider metrics that matter more than new jobs and new businesses. Municipalities have long prioritized entrepreneurial ecosystem development, but strategies that connect these efforts to REDC-funded projects are scarce.

5.7. Capacity Erosion Loop (R4)

Municipalities with limited staff or technical expertise face high per-application fixed costs. They must allocate time to interpret guidance, assemble matching funds, coordinate partners, and develop feasibility documentation. Each submission diverts scarce attention from routine operations. When proposals are unsuccessful, these sunk costs yield no immediate return, producing what interviewees described as a “grant-chasing treadmill.” Over time, repeated setbacks trigger attrition dynamics: morale declines, staff turnover rises, and tacit knowledge—templates, contacts, timing, and informal “how-to” expertise—leaks out of the organization. It is essential to note here that these dynamics arise in a complex environment—and there is not sufficient evidence to conclude that such declines are due solely to the REDC process. Still, we find a self-reinforcing loss of administrative capacity: fewer experienced staff increases the cost and time required to prepare the next application, which depresses quality and success rates, which then further undermines retention and learning, particularly in rural places.

This dynamic is consistent with public administration research on administrative burden. Both learning and compliance costs [15,28] that fall heaviest on low-capacity applicants [9,27] in the form long approval chains and fragmented responsibilities raise the chances of failure. Municipalities and other organizations simply do not have the spare time, staff, and discretionary resources to devote to the ongoing struggle of securing funding. In short, low capacity raises burden; higher burden raises failure risk; failure erodes capacity—a reinforcing loop.

Interviewees captured this vividly. As one municipal leader put it, “How can we even get to the starting line without funding for preparation?” Small, one-off planning grants can help, but when support ends at submission, capabilities do not accumulate. Without ongoing investment in administrative infrastructure, many communities repeatedly approach the “starting line” from scratch—each time paying the full learning cost again. Additional interviews suggest that even in the case of awarded projects, the long-term implementation demands wear on a community’s ability to manage projects and continue the process of securing additional funding for future projects.

To reconfigure the effects of R4, supports must be multi-year and capability-building, not one-off; our findings suggest this is far from the case. Regional service models that include shared staff and pooled technical assistance might alter the strength of this loop. Additionally, structured re-submit pathways with targeted feedback are considered potentially valuable by our interviewees; some interviewees report never connecting with their REDC throughout the submission process, never receiving feedback and resubmitting without any guidance as to how to strengthen their project and proposal. Finally, there is some indication that post-award implementation help can convert effort into retained know-how, raising future success rates and stabilizing local capacity.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study sought to understand the systemic factors influencing the distribution and impact of New York State’s REDC funding model. Using causal loop diagramming informed by public administration theory and stakeholder interviews, we found that the structure of the REDC program may unintentionally reinforce disparities in administrative capacity and access to economic development funding.

At the heart of our findings is the interaction of several reinforcing and balancing feedback loops. The Capacity-Investment Loop (R1) illustrates how communities with high administrative capacity continue to secure funding and grow stronger, while under-resourced communities remain at a disadvantage. The Need-Funding Mismatch Loop (B1) shows that even high-need communities often cannot access funding due to procedural and resource-related burdens, aligning with Moynihan and colleagues [15] framework on administrative burden, particularly in terms of compliance and psychological costs.

The Competition-Induced Frustration Loop (B2) reveals how repeated failures to obtain funding can erode trust in the system and disincentivize future participation, weakening the REDC’s goal of fostering collaboration. In contrast, the Regional Collaboration & Administrative Capacity Loop (R2) shows that inter-municipal cooperation can enhance capacity, but such partnerships are often discouraged by the REDC’s competitive, individualistic structure. Finally, the Local Business Growth Loop (R3) underscores that short-term project-based funding does not always translate into durable and sustainable economic development, as performance metrics often prioritize output over outcomes.

These patterns demonstrate that REDC outcomes are not anomalies—they are the result of embedded feedback structures. The misalignment between REDC’s stated goals and its implementation mechanisms reflects broader challenges in policy design and implementation. As Pressman and Wildavsky [27] warned, well-intentioned programs can fail when they do not account for complexity, capacity, and coordination.

6.1. Policy Implications and Recommendations

To realign REDC outcomes with its equity-focused mission, policymakers should consider reforms that address the structural barriers identified in this study. These include:

- Capacity-Building Grants: Provide direct support for planning, grant writing, and administrative staffing in under-resourced municipalities.

- Incentives for Joint Applications: Reward intermunicipal collaboration through bonus scoring, shared awards, or regional grant tracks.

- Equity-Based Scoring Adjustments: Modify agency scoring criteria to account for community need, not just project readiness or feasibility.

- Support Beyond Award: Offer post-award assistance for implementation, monitoring, and reporting—especially in communities with limited staff.

- Data Transparency and Feedback Loops: Regularly evaluate and publish funding outcomes disaggregated by region, need level, and project type to monitor equity impacts.

These changes would reduce administrative burden, incentivize cooperation, and ensure that funding reaches communities most in need—without compromising accountability or performance.

6.2. Contribution to Theory and Practice

This research contributes to the sustainability literature in three primary ways: (1) By applying causal loop mapping to the domain of regional economic development funding, we highlight how program design interacts with local capacity and structural constraints, offering a systems-based diagnosis of why certain communities succeed repeatedly in accessing REDC funding while others remain persistently locked out; it demonstrates how feedback loops can illuminate structural inequalities in policy design and outcomes, (2) by integrating public administration theories—such as administrative burden [15], institutional capacity [8], and collaborative governance [16]—we link sustainability literature with governance scholarship, and (3) by identifying the systemic constraints within the REDC funding process, this study provides a framework for understanding how well-designed policies may still fall short without structural reform. In doing so, it offers a new lens through which to analyze development programs and propose practical, systems-informed improvements.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

As a qualitative causal loop study, this research does not claim to test causality or predict future outcomes. The diagrams reflect interpretive synthesis of data and theory and are meant to support conceptual understanding and policy dialogue.

Future research will build on these insights by developing a quantitative simulation model that incorporates historical REDC data. This model will allow for scenario testing—such as reallocating funds based on need, rewarding collaboration, or offering tiered application processes. By simulating potential outcomes, we hope to support data-driven policy decisions that better align REDC funding with its mission of equitable, sustainable regional development.

Furthermore, a natural extension of this work is to analyze how the governance patterns identified here affect the distribution of environmentally focused projects such as renewables, energy efficiency, and green infrastructure. Linking process equity to environmental outcomes would help clarify whether capacity-building and collaborative incentives also improve regional decarbonization and resilience. We note this direction for future research and dataset development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.R., M.T.K., J.E. and L.F.L.R.; Methodology, A.M.R. and L.F.L.R.; Validation, M.T.K.; Investigation, A.M.R., S.K., I.H.N. and L.F.L.R.; Data curation, S.K. and I.H.N.; Writing—original draft, A.M.R. and M.T.K.; Writing—review & editing, J.E., S.K., I.H.N. and L.F.L.R.; Project administration, A.M.R.; Funding acquisition, A.M.R., J.E. and L.F.L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation grant number not available.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University at Albany, protocol number 22X200, IRB00000589, approved on 7 September 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality of research subjects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brundtland Commission. Our Common Future. Oslo, United Nations. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Goetz, S.J.; Partridge, M.D.; Deller, S.C.; Fleming, D.A. Evaluating, U.S. Rural Entrepreneurship Policy. J. Reg. Anal. Policy 2010, 40, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundey, D. Evaluating the Impact of Regional Policy on Social and Economic Development of a Region. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2009, 8, 188–190. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, D.; Schulz, T.; Seidl, I. Quantifying entrepreneurship and its impact on local economic performance: A spatial assessment in rural Switzerland. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 222–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calispa Aguilar, E. Rural entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic literature review for advancing conceptualisation. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2021, 9, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkier, H. Knowledge Dynamics and Policies for Regional Development: Towards a New Governance Paradigm. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 1767–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Comons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.G. Policy capacity in public administration. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shybalkina, I. Getting a grant is just the first step: Administrative capacity and successful grant implementation. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2024, 54, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C. The institutional collective action framework. Policy Stud. J. 2013, 41, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herd, P.; Moynihan, D.P. Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Andersen, D.L. Collecting and analyzing qualitative data for system dynamics: Methods and models. Syst. Dyn. Rev. J. Syst. Dyn. Soc. 2003, 19, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, G.P.; Pugh, A.L. Introduction to System Dynamics Modeling with DYNAMO; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, D.; Herd, P.; Harvey, H. Administrative burden: Learning, psychological, and compliance costs in citizen-state interactions. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2015, 25, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, K.; Walters, J.P. Using causal loop diagramming to explore the drivers of the sustained functionality of rural water services in Timor-Leste. Sustainability 2016, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, M.; Massey, D.; Rozhkov, A.; Murphy, J.T. Exploring the barriers to and potential for sustainable transitions in urban–rural systems through participatory causal loop diagramming of the food–energy–water nexus. Land 2023, 12, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isserman, A.M. Competitive advantages of rural America in the next century. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2001, 24, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasmeier, A.K.; Farrigan, T.L. Landscapes of inequality: Spatial segregation, economic isolation, and contingent residential locations. Econ. Geogr. 2007, 83, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2003, 97, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, G.; Van de Walle, S. Comparing measures of citizen trust and user satisfaction as indicators of ‘good governance’: Difficulties in linking trust and satisfaction indicators. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2003, 69, 329–343. [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson, H.G. Social Equity and Public Administration: Origins, Developments, and Applications; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Agranoff, R.; McGuire, M. Collaborative Public Management: New Strategies for Local Governments; Georgetown University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bickers, K.N.; Stein, R.M. Interlocal cooperation and the distribution of federal grant awards. J. Politics 2004, 66, 800–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, J.L.; Wildavsky, A. Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland: Or, Why It’s Amazing That Federal Programs Work at all, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by Two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals on a Foundation of Ruined Hopes; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1984; Volume 708. [Google Scholar]

- Herd, P.; Hoynes, H.; Michener, J.; Moynihan, D. Introduction: Administrative Burden as a Mechanism of Inequality in Policy Implementation. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, P.; Kimmitt, J. Rural entrepreneurship in place: An integrated framework. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 842–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, Y.; Lafuente, E. Do different institutional frameworks condition the influence of local fear of failure and entrepreneurial examples over entrepreneurial activity? Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2007, 19, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Fisher, P. The failures of economic development incentives. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2004, 70, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.L. Choosing an entrepreneurial development system: The concept and the challenges. Int. J. Manag. Enterp. Dev. 2005, 2, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.W. Urban dynamics. IMR. Ind. Manag. Rev. 1970, 11, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Moyano, I.J.; Richardson, G.P. Best practices in system dynamics modeling. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2013, 29, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, M.; Garrett, J.; Fullam, J.; Lovell, R.; Guell, C.; Taylor, T.; Garside, R.; Zandersen, M.; Wheeler, B.W. Using causal loop diagrams to develop evaluative research propositions: Opportunities and challenges in applications to nature-based solutions. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2024, 40, e1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoaia-Cotisel, A.; Allen, S.D.; Kim, H.; Andersen, D.F.; Qureshi, N.; Chalabi, Z. Are we there yet? Saturation analysis as a foundation for confidence in system dynamics modeling, applied to a conceptualization process using qualitative data. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2024, 40, e1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, C.; Callegari, B.; Collste, D. The system dynamics approach for a global evolutionary analysis of sustainable development. J. Evol. Econ. 2024, 34, 351–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.P. Problems with causal-loop diagrams. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 1986, 2, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagonel, A.A. ARCHIVE PAPER: Micro worlds versus boundary objects in group model building: Evidence from the literature on problem definition and model conceptualization (2007). Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2024, 40, e1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; MacGraw-Hill Company: Columbus, OH, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, I.; Cho, B.; Roggio, A.; Kim, S.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. How New York Regional Economic Development Council supports rural entrepreneurship. In Proceedings of the Public Management Research Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 25–28 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, B.K.; Gerber, B.J. Redistributive policy and devolution: Is state administration a road block (grant) to equitable access to federal funds?”. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2006, 16, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.L. Assessing local capacity for federal grant-getting. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2008, 38, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, K.; Reckhow, S.; Gainsborough, J.F. Capacity and equity: Federal funding competition between and within metropolitan regions. J. Urban Aff. 2016, 38, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, P.; Ryan, L.L. Competitive grants and educational federalism: President Obama’s race to the top program in theory and practice. Publius J. Fed. 2011, 41, 522–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. The Matthew effect in science: The reward and communication systems of science are considered. Science 1968, 159, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigney, D. The Matthew Effect: How Advantage Begets Further Advantage; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stroh, D.P. Systems Thinking for Social Change: A Practical Guide to Solving Complex Problems, Avoiding Unintended Consequences, and Achieving Lasting Results; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River, VT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, I.; Cho, B.; Roggio, A.; Luna-Reyes, L.F. The Impacts of Political Leaders’ Social Capital on Policy Success: The Case of Local Food Systems. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.K.; Andrew, S.A.; Khunwishit, S. Complex grant-contracting and social equity: Barriers to municipal access in federal block grant programs. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2016, 39, 406–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.R. Nonprofits as a resilient sector: Implications for public policy. In Nonprofit Policy Forum; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2023; Volume 14, pp. 237–253. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).