Abstract

In urban spaces, areas that can be used for cultivation are largely limited. In addition, the use of areas belonging to green–blue infrastructure for agricultural purposes is not always feasible under conditions of high urban population density. Currently, over half of the global population live in cities, which affects the price of land and how it is developed within the urban fabric. By 2050, at least 70% of the human population is estimated to be living in cities; therefore, problems related to the economics and logistics of supplying food to residents are expected to increase and become significantly more complex. Attempts to develop alternative solutions for food production that minimally absorb usable urban space and have low climate impacts on the urban fabric have already been made. One such solution is large-scale vertical food cultivation in the underground areas of cities, such as unused parts of metro stations, bunkers, basements, and underground parking lots. This study aims to analyze the feasibility of using underground urban spaces for efficient and environmentally friendly food production in terms of spatial, economic, ecological, and climatic aspects. The conducted research is based on a review of literature and urban documents, which was complemented by a SWOT analysis, a Weighted SWOT, and a TOWS matrix. The results obtained indicate a number of benefits, such as independence from weather conditions and the shortening of supply chains, while simultaneously pointing to barriers related to high energy costs and the lack of regulatory frameworks. The conclusions, however, suggest that underground farming may serve as one of the elements of critical food-related infrastructure, provided that this system is integrated into urban policies and receives additional systemic support.

1. Introduction

Due to the ongoing urbanization of all continents and preference for cities as places of residence, as much as 70% of the population is estimated to live within the urban fabric by 2050 [1,2]. This means that cities are likely at a critical turning point in relation to spatial, environmental, climatic, and social changes. As cities expand, they require more energy and water and will increasingly use space for residential purposes. A larger number of residents also implies a greater demand for fresh, healthy, and easily accessible food. However, demographic pressure and competition for access to agricultural land mean that food production will be increasingly displaced from urban areas (e.g., liquidation of allotment gardens). Cities are slowly beginning to function as the largest consumers of resources, dependent on external, often unstable, food supply chains [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. This may cause future social crises and contribute significantly to increasing inequalities in food access and social exclusion [10,11,12,13]. This situation becomes dire when we realize that the world is slowly facing a food crisis. Observed climate change and consequently the occurrence of extreme weather events, soil degradation, excessive monoculture introduction in agricultural crops, and water resource depletion have caused traditional agricultural production systems to become less efficient, thereby contributing to environmental burdens [14,15,16]. In the face of armed conflicts (e.g., in Ukraine) or pandemics (e.g., COVID-19), the supply of food to the urban population is becoming increasingly important, and vulnerability to supply chain disruptions is a reason to consider the deepening problem of food shortages and lack of food sovereignty in modern cities, even in the more developed cities of the Global North [17,18,19,20,21,22]. In this context, a rethinking of the possibilities and methods for organizing food production in the urban fabric as an alternative system for supplying fresh vegetables to the population is critical. This will make it possible to increase the level of food supply security for urban residents. One of the alternatives and increasingly tested systems of food production in urban fabrics is the use of underground structural spaces, such as basements, metro tunnels, shelters, underground parking lots, or post-industrial halls. In these locations, low-emission plants can be developed under controlled conditions using spaces that in many cases are already unused or are difficult for people to use. Such a strategy can contribute to reducing the carbon footprint of cities related to food transport [23,24,25,26,27] and allow for the optimal use of urban space.

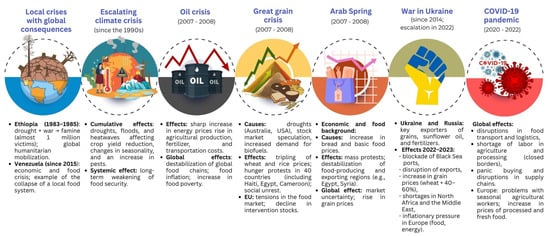

Because contemporary cities are highly dependent on global supply chains, even minor disruptions can result in shorter or longer interruptions in access to basic food products. Such a situation may be caused by armed conflicts, natural disasters, extreme weather events, or pandemic outbreaks. An example is the recent food crisis caused by Russia’s conflict of Ukraine in 2022, which clearly shows the instability of the grain supply system and how quickly it could collapse. Crisis situations worldwide usually have an impact on the global or European food supply and can disrupt its production, availability, prices, or distribution. Figure 1 presents examples of selected global crises that have occurred since World War II, emphasizing how their cascading effect could potentially have influenced food security in urban areas, illustrating the so-called “butterfly effect” in relation to the issue of food supply for cities (Figure 1) [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Each of these crises reveal instability in supply chains, underscoring the importance of building adequate resilience in urban food systems, that is, urban food resilience, and the need to shorten supply chains as much as possible through the implementation of appropriate policies and crisis management as well as development of urban agriculture and creation of strategic food reserves.

Figure 1.

Selected global crises that have occurred since World War II and their potential cascading impact on food security in urban areas (the so-called “butterfly effect”).

Progressive urbanization also influences how cities are supplied with food because it leads to the deagrarianization of suburban areas and fragmentation of agricultural land. Suburban areas play an important role in maintaining the security of urban supply chains. Unfortunately, their constant development has resulted in the need to import food from increasingly distant areas. In the face of climate change, the intensity of agricultural development, which accounts for approximately 17–32% of global greenhouse gas emissions [42,43,44,45], as well as soil degradation [46], excessive water resource depletion [47,48,49], and the negative impact of introducing monocultures and genetically modified organisms on biodiversity must also be considered [50,51]. From this perspective, current and future food crises may also affect Earth’s climate and natural resources. This emphasizes the importance of implementing solutions based on the production of “ethical food,” which should be produced locally by residents of urban agglomerations [52,53,54]. Such an approach can not only protect urban residents from problems with access to fresh food, but also help maintain the well-being of our planet. Overall, food systems in cities are sensitive to the effects of climate change, including heat waves, droughts, floods, and variability in growing seasons. The urban fabric, through dense development and improperly designed green–blue infrastructure, creates spaces with the urban heat island effect, making it difficult to use these areas for potential urban agriculture, which has been marginalized in spatial and urban planning processes for decades. Recently, this topic has reappeared as a new element of strategic actions, not only of a social dimension but also, above all, pro-climatic [55,56]. Adapting food systems to new challenges in urbanized areas is currently becoming one of the most important topics in the contemporary debate on sustainable urban development. Another challenge in the food supply security system for city residents is excessive waste [57,58]. Estimates show that approximately 30–40% of food is wasted, not only at the distribution stage but also at the consumption stage [59]. Hence, real and efficient functioning mechanisms must be built for the recovery and recycling of bioproducts that can be fed into urban food production systems. Failure to use these resources results in the loss of valuable nutrients and an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, which is reflected in problems with waste management. One solution is the implementation of a circular food system that utilizes biowaste and its composting and another is the creation of a closed cycle of biowaste resource use in the city. Persistent challenges in urban food systems include the surplus of food in cities and undernourishment of the poorest residents (i.e., food deserts). This paradox indicates that fair access to fresh and healthy food in cities is one of the most significant problems to be solved in the coming decades. This can be addressed to a large extent by proper spatial planning, in which projects consider climate issues, waste management, and the use of space for the needs of urban agriculture [60,61,62]. This is not just about creating new allotment gardens, but developing integrated projects of genuinely functioning actions for food production using all possible available urban spaces, particularly those underground, to stabilize food systems. In such systems, the trend towards the appropriation and enclavization of urban spaces can be reversed A coherent urban food policy is also necessary (literature), as its absence causes chaos and often destroys decision-making processes regarding cross-sectoral activities related to urban food production. Because of these problems, an increasing number of cities are now trying to systematically develop their own strategic food systems, with the overarching goal of integrating different sectors and linking them to food (e.g., transport, waste management, education, and health) [63,64]. Some examples include the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact [65], which has been signed by over 250 cities, and local urban strategies developed for Toronto, Barcelona, and Copenhagen [66,67,68]. This research contributes to the broader discourse on resilient and adaptive urban systems, emphasizing how innovative food production models can enhance cities’ capacity to respond to environmental and socio-economic challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

In the conducted research on underground urban farms, it was assumed that this issue is multifaceted and significant from the perspective of spatial planning, urban studies, and environmental and climate considerations [69,70,71]. The aim was not only to describe existing examples, but also, above all, to attempt to define the role that such farms may play within the urban system. The analyses focused primarily on treating them as: spaces utilizing new technologies, a way of adapting existing infrastructure, and a potential response of cities and various sectors (urban planning, spatial planning, logistics, and agriculture) to climate and food security challenges [72,73]. Therefore, the proposed research methodology combines urban, environmental, technological, and social approaches. At the same time, the research process was based on clearly defined research questions that determined the direction of the analysis.

The following research questions were posed:

- ○

- Under what conditions can underground farms become a real element of the urban food system, and in what ways can they strengthen the urban metabolism and support the city in adapting to climate change?

- ○

- What are the key strengths and weaknesses of underground urban farms, and what opportunities and threats arise from the political, social, and environmental context? Which of these factors are the most significant, and how should they be prioritized?

- ○

- What strategies for integrating underground farms into the urban fabric can be developed in order to best utilize their potential and minimize environmental risk?

- ○

- Can underground urban farms support processes of including various social groups in joint activities within their space, and is their integration into ecological education of city residents possible?

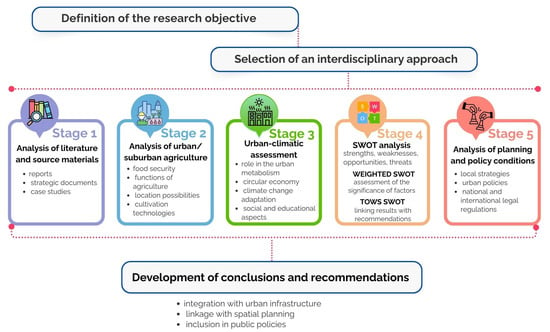

Answers to these questions were sought in five interrelated stages that together formed a coherent whole (Figure 2). The first step was a review of scientific literature as well as strategic documents, supplemented with industry reports and an analysis of urban food and climate plans [69,70,71]. For this purpose, the Scopus and Web of Science databases were searched, along with FAO and UN-Habitat reports, which together allowed the collection of over 200 literature sources. After an initial selection, about 155 were chosen as the basis for further work. At this stage, the aim was to identify global trends in urban food production, applied technologies, examples of food production in underground spaces, as well as cases of successful implementations and data on problems and barriers encountered at various stages of their functioning [74,75].

Figure 2.

Research methodology—action scheme.

To compare different projects related to underground urban farms, a set of common descriptive categories was developed, including type of underground space (e.g., metro tunnel, parking lot, shelter, basement, etc.), cultivation technologies (hydroponics, aeroponics, aquaponics, mixed CEA systems), type of production (leafy vegetables, herbs, mushrooms, fruits), scale and intensity of production (where possible expressed quantitatively), additional functions (social, educational, tourist, commercial), and links with urban systems (energy, heat, CO2, circular economy). Thanks to this approach, examples of underground farms such as La Caverne in Paris, Growing Underground in London, or Cycloponics in Brussels were compiled. Despite differences, these farms were described according to one common framework. On the basis of these studies, a three-dimensional typology of underground urban farms was developed, encompassing the spatial dimension (type of infrastructure), technological dimension (level of advancement of CEA systems), and functional dimension (dominant role of the facility—productive, educational, integrative, touristic, innovative). This enabled comparison of highly diverse cases within a coherent analytical framework and the identification of patterns recurring across different cities [74,75].

In the next stage, the potential of underground urban farms was assessed in the context of their integration into urban metabolism and climate adaptation. The analysis focused on how these farms can contribute to shortening supply chains, reducing transport emissions, reusing resources such as waste heat or CO2, and ensuring production continuity regardless of weather conditions [73]. The research also considered the social dimension of these investments, as they can serve both as educational spaces and as sites of inclusive integration and tools for building ecological awareness [74].

The strategic analysis was based on the SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats—a classical method for identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats), the Wright SWOT (a modification enabling the analysis of interrelations between factors), and the TOWS matrix (an extension of SWOT used for designing development strategies [76,77,78]). Weights ranged from 0 to 1, indicating the relative importance of each element within the system, with a value of “0” denoting no relevance and “1” the highest importance; the sum of weights in each category equaled 1. Scores were assigned within the range from −5 to +5, where negative values indicated strong negative impact (weakness or threat), and positive values indicated positive impact (strength or opportunity). The value “0” denoted no clear influence. The final score was obtained by multiplying the weight by the score, which made it possible to distinguish key factors and assign them appropriate priorities (see Annex S1 in Supplementary Materials and Table 1). This analysis determined which elements may be crucial for the development of underground farms within the urban fabric, and which were marginal. Based on these results, a TOWS matrix was constructed [77,78], linking internal and external factors, which made it possible to generate a catalog of strategies. In total, 140 scenarios were developed through this analysis, which were synthesized and grouped into four main directions: utilization and revitalization of existing infrastructure, energy linkages and circular economy, integration of farms into urban policies, and educational and communication activities. The article presents the priority strategies (Table 2), while the full set of analyses is provided in Annex S2 in Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Results of the Weighted SWOT analysis—a synthetic summary of the most important factors identified during the analytical process for underground urban farms (the full analysis is provided in Annex S1 in Supplementary Materials).

Table 2.

TOWS matrix—a synthetic summary of the main strategic directions for underground urban farms (the full analysis is provided in Annex S2 in Supplementary Materials).

The final step was synthesis and recommendations, which allowed the transition from the analysis of cases and factors to the design of concrete scenarios for the development of underground urban farms. Thanks to this approach, underground farms were not only described but also embedded within the urban fabric, shown as supporting the city’s circular economy, and framed as part of climate adaptation strategies. On this basis, the authors formulated original conclusions and recommendations regarding the integration of underground food farms into urban infrastructure, spatial planning, and public policy.

All figures, photographs and visual materials presented in this article were prepared by the authors to illustrate the analyses and interpretations developed within the framework of this study.

3. Results

3.1. Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture

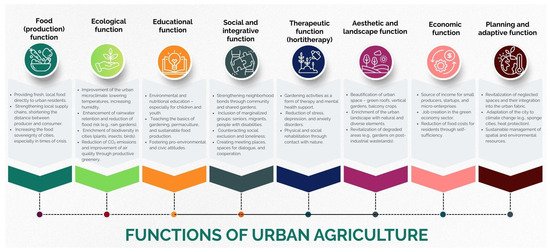

Urban agriculture is an underappreciated system that addresses the problem of supplying residents with fresh and high-quality food. It entails the practice of growing plants and/or raising animals on the outskirts of or within cities. Such a system responds to the problems and challenges related to food supply security for urban residents while also addressing climate change and often unnecessary natural environment degradation [79,80,81,82]. Urban agriculture has multidimensional and multifaceted impacts (Figure 3), including production, ecological, esthetic, landscape, and educational dimensions. It plays an important role in the social and integrative conditions of city residents. It can also serve a therapeutic role for busy, tired, and over-stimulated individuals by providing contact with nature. An important element of urban agriculture is its economic dimension, which can constitute an additional source of income for small producers and elderly people and contribute to job creation [71,72,73,74,75]. Although its planning and adaptive functions are underestimated, such a practice helps revitalize degraded areas within cities and is an important element in adapting them to climate change [79,80,81].

Figure 3.

Functions of urban agriculture.

Urban agriculture in the era of climate, economic, political, and health crises can play a key, if not one of the most important, role in building resilient, just, and nature-oriented cities.

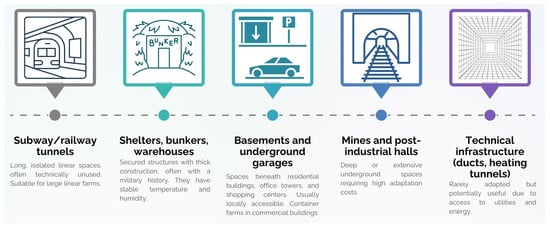

Peri-urban agriculture supports urban agriculture systems and is related to the implementation of agricultural activity conducted in urban outskirts, that is, in suburban or transitional areas between urbanized and rural areas, constituting a buffer zone. In the urban planning context, peri-urban agriculture forms a barrier to uncontrolled urban sprawl and is constantly under urban pressure (e.g., development or infrastructure projects). In Europe, these areas cover approximately 48,000 km2, and their size is comparable to that of urbanized areas [82,83,84,85,86]. Similar to urban agriculture, peri-urban agriculture fulfills several important functions (Figure 4), including production, such as enabling the supply of fresh vegetables and fruits to cities; ecological, performing many tasks such as supporting biodiversity and strengthening the city’s green infrastructure; spatial and landscape, serving as a spatial barrier limiting urban sprawl and preserving the landscape mosaic with field trees; and social, becoming a place where residents can build an identity, socially integrate, and fill the educational gap for children and youth. In terms of the economic function, it provides additional sources of income for local farmers and their families, supporting the local market and shortening supply chains. Peri-urban agriculture influences the maintenance of land reserves that can be developed in the future and forms a buffer between the city and countryside, thus fulfilling planning and strategic functions [86].

Figure 4.

Functions of peri-urban agriculture.

Urban and peri-urban agriculture plays a significant role in maintaining local food systems and supply chains, supporting the local economy, and fulfilling ecological and landscape functions [87,88,89,90]. The pressure of urbanization, visible both at the edges of cities and within their dense fabric, leaves little space for food production. In such conditions, traditional agriculture struggles to find its place in the vision of modern, sustainable urban systems. The answer to these challenges is the development of vertical and underground agricultural systems, which makes it possible to redefine the usability of abandoned and inaccessible areas classified as unsuitable for vegetable cultivation. A special role in this arrangement can be played by underground agriculture. As this form of cultivation is independent of weather phenomena, it allows for the continuous quality control of crops, reduces pressure on the natural environment, and enables continuous harvesting.

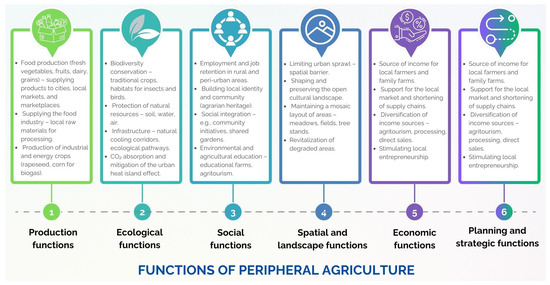

3.2. Underground Farms as an Alternative Form of Urban Agriculture

Traditional forms of urban agriculture, such as allotment gardens, home gardens, rooftop farms, have a major drawback; they require space, which is a scarce resource in densely developed urban fabrics. For this reason, multi-level thinking regarding urban space is needed, with underground areas no longer only considered technical zones but also as levels that can be used within the urban fabric for agricultural cultivation. Underground agriculture is an innovative form of urban agriculture that is slowly but systematically gaining support. This form of agriculture uses abandoned areas that are often post-industrial, unused, or difficult for city residents to use, such as tunnels, basements, parking lots, metro stations, or shelters (Figure 5), which constitute almost ready-to-use infrastructure that meets the needs of urban agriculture. However, for underground farms to exist, they must use advanced technologies such as hydroponics, aeroponics, LED systems, controlled atmosphere systems, and infrastructure managed with artificial intelligence (AI) [25,71,72,88,89,90,91,92] (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Underground farm locations.

Figure 6.

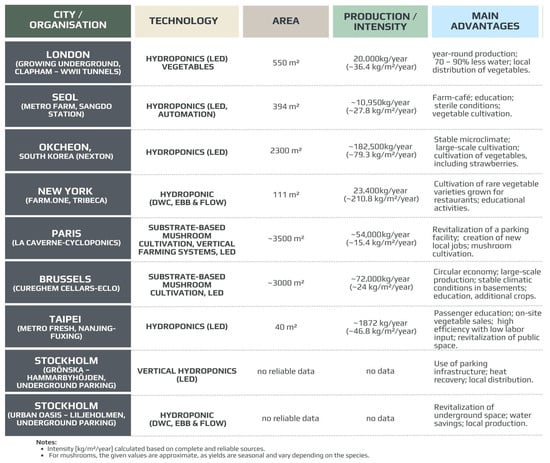

Examples of underground urban farms worldwide with their location, technology, area, production intensity, and main advantages [93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102].

Figure 7.

Technologies used in underground farm cultivation.

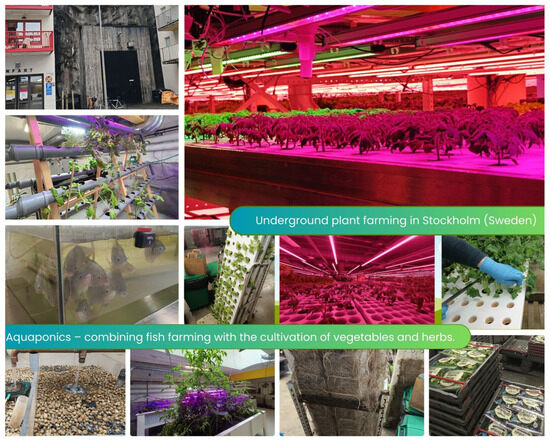

Figure 8.

Examples of good practices for underground farm technological solutions in Sweden.

3.3. Technologies for Underground Cultivation

Underground agriculture is only possible with appropriately selected technologies because of the lack of natural sunlight, soil, and water. Therefore, hydroponics, aeroponics, aquaponics, LED systems, temperature and microclimate control systems, closed-loop water supply systems, automation, and parameter monitoring systems using IoT (Internet of Things) are necessary (Figure 7) [103,104]. The use of these systems allows the precise adjustment of light, water quantity, temperature, fertilizer consumption, energy management, and harvesting pace during the day. The combination of all these elements enables continuous production independent of the season. Therefore, underground farming can provide more environmentally sustainable practices compared to traditional cultivation methods.

The technologies used in lighting systems are LEDs that utilize the full light spectrum, adjusted to the specific growth phases of plants grown underground. The advantages of using such solutions are low heat emissions, high energy efficiency, and the possibility of using the appropriate color and light intensity tailored to the cultivation requirements [104,105,106].

Multizone lighting is also used in underground cultivation, employing various types of light adapted to many crops on one farm and in different sectors containing other plants. This can reduce the energy requirements of vegetable production (Figure 8). The most modern solution is real-time light control systems via AI sensors, which are dynamic lighting systems (smart lighting) designed to optimize plant growth and save energy, and are well integrated with the microclimate inside the cultivation space [103,104,105].

In enclosed spaces, climate and atmosphere control is important; thus, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems are used to maintain appropriate temperature and humidity and provide heating, ventilation, and air conditioning functions. Humidity control ensures adequate protection against excessive moisture, molds, and fungi (literature). In underground cultivation, CO2 control is also important as it is supplied to accelerate photosynthesis and thus increase yields [106].

For proper equipment operation and parameter control, microclimate sensors are used to measure temperature, color and light intensity, and water pH and electrical conductivity, thereby enabling precise control of the plant growth environment For systems to be efficient and not consume excessive amounts of resources, closed-loop water circulation systems are used, in which the water in circulation is purified and reused, reducing water consumption by approximately 90–95% compared with conventional surface cultivation [25].

Because of precise fertilizer dosing (fertigation), plant growth is optimized and nutrient losses are reduced. Under conditions of high-density cultivation, regulated microclimates, and lack of natural ventilation, food production safety is ensured by removing pathogens from the water and air using air and water filtration systems and UV systems [107,108,109].

Modern information technologies help control this system through IoT systems, which allow remote monitoring and data collection from sensors located throughout the cultivation area and remotely controlling them, enabling energy savings and real-time crop monitoring [110]. AI is also used to optimize cultivation conditions through machine learning and data analysis, thus increasing yield.

To operate these devices, special applications and platforms are required, for example, cloud-aggregating data, energy, and environmental dashboards, which collect data on energy consumption, emissions, and yields. These applications and sensors are used to create special security systems for monitoring, alerting people about parameter exceedances, or even in ordinary access control of the cultivation area [111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118].

To minimize costs, modern underground farms use modular container systems that often combine various technologies to optimize resources and space. In addition, photovoltaic panels and energy storage facilities are installed on the surface for such crops, which are used, for example, to power LED lighting. Moreover, CO2 recirculation from ventilation systems is used, as is heat from office buildings, industrial plants, and metro systems [115,116,117,118,119].

3.4. Underground Farms as an Element Supporting Urban Metabolism and Resilience to Climate Change

The cultivation of plants underground is a response to the constantly increasing pace of urbanization and city development. In addition, climate pressure and the need for cities to adapt to climate change make it necessary to implement changes and transformations in many sectors related to urban space management. This entails redefining urban production spaces, including spaces designated for the development of urban agriculture. Contemporary cities have many unused areas with appropriate structures and technical infrastructures, thereby enhancing their utility potential. Local food production in sustainable cities is becoming an essential step towards the future, and the concept of underground farms represents a multidimensional approach to the use of space in the urban fabric. In this manner, cities can gain new economically developed areas, generate profits, and strengthen food security for residents, which can significantly increase their autonomy.

In the future, underground farms may become key elements and components of city adaptation and serve as strong reinforcements to urban resilience in the face of climate change. Due to their construction and location, as well as the fact that they have natural thermal insulation, they are resistant to variable climatic conditions, seasonal changes, and other external factors. This enables year-round cultivation and the possibility of regulating the quantity and frequency of harvests and introducing greater crop security compared with conventional large-scale agriculture. Through water recycling (in hydroponic cultivation), water savings can amount to about 90% and pesticides can be eliminated. The water resources saved can be used to maintain green infrastructure in cities, which not only has economic benefits but also supports the city’s adaptation to climate change, with agricultural pollution virtually being eliminated. Additionally, owing to the use of various methods of renewable energy utilization and energy recovery, underground farms can be as low-emission or even almost climate-neutral as food production systems. Their location, possible in almost any part of the city (e.g., city center) is an additional advantage, as it allows production in direct proximity to consumers, which contributes to reducing CO2 emissions associated with transport within cities and in suburbs and food storage and refrigeration.

Underground farms can be classified not only as elements of Circular Urban Agriculture [119,120] but also as Smart Green Infrastructure [121] because they constitute a system connecting plant production with urban metabolism [122]. In this sense, underground farms can be treated as a specific systemic interface owing to spatial factors (hidden and invisible spaces), energy recovery from buildings (in the form of heat capture), a social interface connected with education, food supply, logistical aspects (transport), and recycling. This means that they can be regarded as an element of new ecological urbanism (literature) whose main axis is urban symbiosis, considering synergy models and flows in the multidimensional system of the urban fabric [123,124].

3.5. Social and Educational Dimensions of Urban Underground Agriculture

In cities, underground farms can be used not only as places for food production but also as spaces for residents and have educational functions (Figure 9). The cultivation of vegetables and mushrooms underground is usually conducted by entrepreneurs, but it can also be conducted by social groups, e.g., non-profit organizations, which often combine the production function with an educational one and create areas for the vocational reintegration of various groups of residents, including the elderly and socially excluded individuals. One example is the farm located in the underground parking lot La Caverne in Paris [96,125] in which immigrants and youth who are not in education, employment, or training participate [126]. Workshops for children, school pupils, and students can also be organized, such as the Growing Underground Project in London at a farm established by Richard Ballard and Steven Dring in 2015 [127]. These activities can be implemented at the street (e.g., involving residents of several buildings located on the same street) or district (e.g., several underground farms) levels.

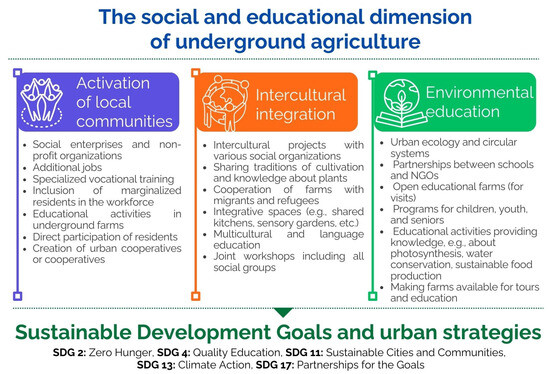

Figure 9.

Social and educational dimensions of underground farms.

In underground farms, plants from different parts of the world can be grown, which enables a cultural dialog with agriculture based on vegetable cultivation as a unifying element. This allows the integration of people from different cultures, nationalities and religions, making it possible to build communities at various existential levels [128,129,130,131]. Thus, underground farms can become urban spaces for transformative education—places that provide knowledge about cultivation, ecology and ecosystem services, and at the same time shape ecological awareness and attitudes among residents.

Other added values may also be the creation of new jobs, especially for those outside the labor market, and as places for organizing internships and vocational training, providing opportunities for volunteering, which allows for actions that increase social cohesion and resident engagement in a given urban area. This can lead to the generation of a strong social capital, especially where there is a lack of access to public space. These activities align positively with the Sustainable Development Goals, European Green Deal, EU Farm to Fork Strategy, urban strategies, local climate plans, food justice strategies, and the 2030 Agenda [132,133,134,135,136,137].

3.6. Integration of Underground Farm Implementation into Urban Fabrics Considering Municipal and Climate Policies

Underground farms have the potential to be used for the production of vegetables, herbs, mushrooms, and fruits in urban areas. Unfortunately, official planning documents rarely consider their existence and design. Although their potential may not be evident initially, it is enormous, ranging from economic and environmental to climatic and social benefits. Therefore, the lack of a systematic approach to the implementation of these systems in official city planning documents remains a challenge.

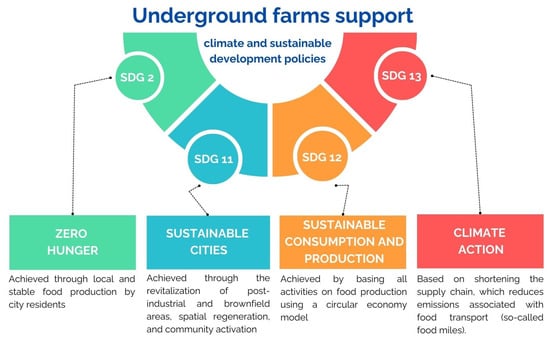

Underground farms can address many key objectives related to climate change adaptation, post-industrial area revitalization, food supply chain shortening, local circular economy development and support, job creation, exclusion prevention, education, and public–social partnership development involving local authorities, NGOs, and social enterprises [69,70,138,139]. Such provisions can be included in local climate action plans, urban food strategies, municipal circular economy strategies, and strategic food plans (Urban Food Strategies) [137]. As previously mentioned, food-producing underground farms can also strongly support several Sustainable Development Goals, such as SDG 2, 11, 12, and 13 [108,135] (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Sustainable Development Goals supported by urban underground farms.

The development of such dedicated strategies and the inclusion of these elements in strategic urban development documents could help finance such projects, especially because urban food systems, including food production on underground farms, can be considered critical infrastructure and should therefore be included in new food production models [69,140].

An important element of urban space recovery policy is planning based on the regeneration and revitalization of spaces that can be used for food production. This involves the reclamation of unused and often-neglected existing underground infrastructure, such as metro tunnels, underground parking lots, and bunkers [24,138,141,142,143]. Considering the sustainable and green transformation of the circular economy, underground food-producing farms support the creation of jobs in the green production sectors, logistics, education, and the building of resident communities producing vegetables and herbs. In addition, they contribute to water and energy recovery within the urban metabolism and support zero-emission logistics.

They foster the transformation of the urban economy into a “green economy,” which is in line with the expectations that sustainable cities should meet through the development of new forms of supporting and advancing urban agriculture and integrating it into green–blue infrastructure systems [70]. To fully materialize and implement these activities, underground farms should be reflected in planning and legislative documents to facilitate action by all interested parties (primarily residents).

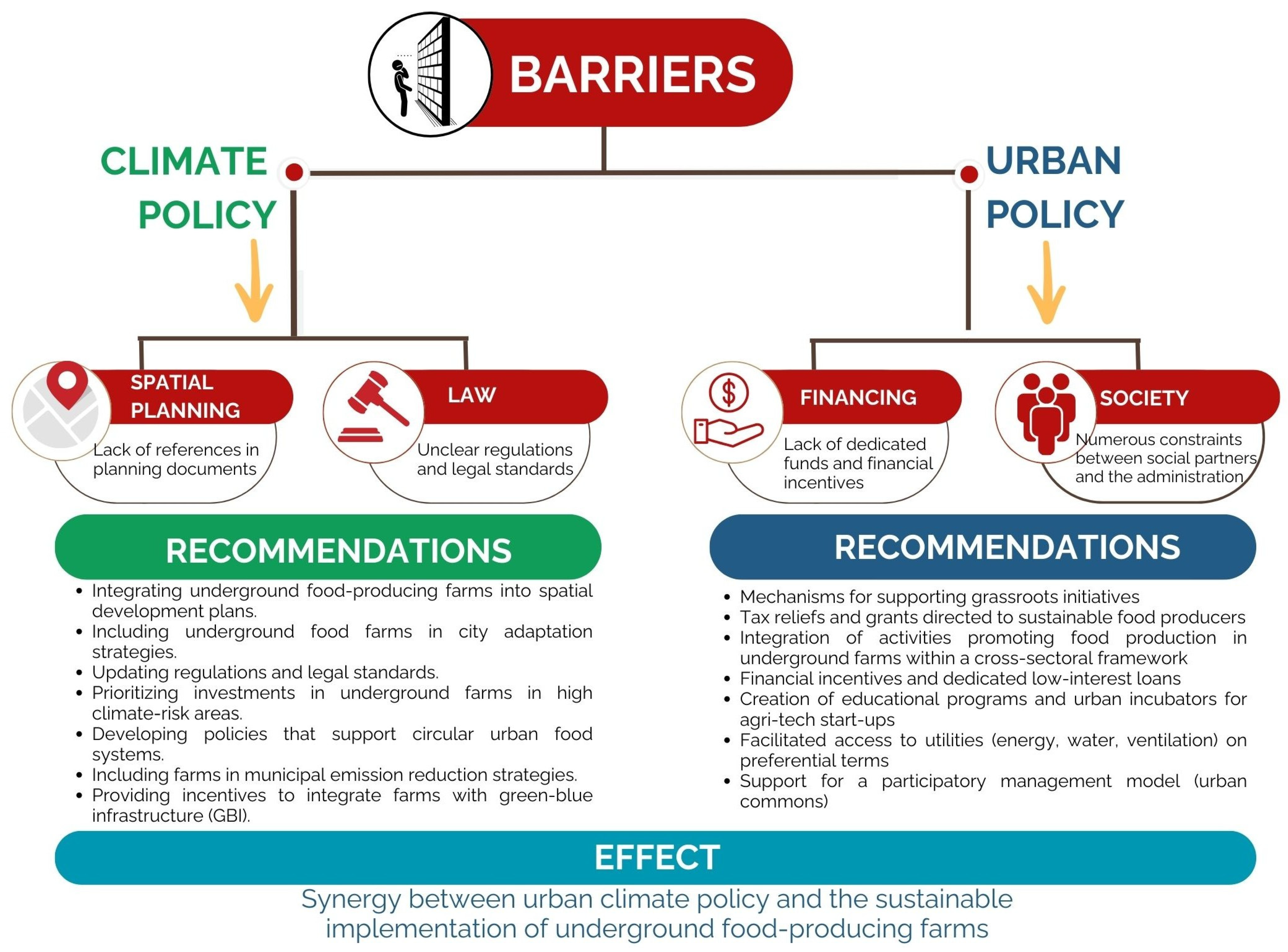

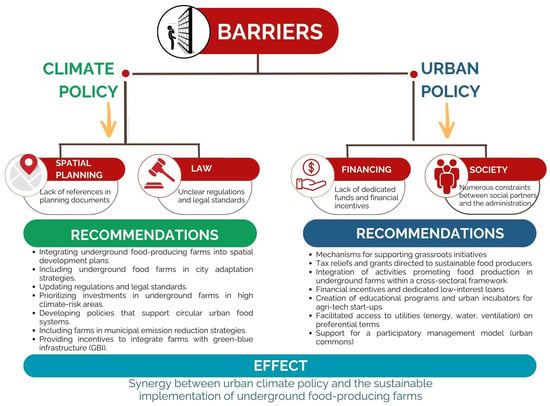

To achieve synergy between climate and urban policies within the urban fabric and develop a method for implementing and developing underground farms, spatial planning and legal, financial, and social barriers must be overcome (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Barriers to achieving synergy between climate and urban policy for underground farm implementation in cities.

3.7. Economic Considerations of Underground Farms

From an economic perspective, underground farming conducted within CEA carries both clear benefits and serious barriers, which may determine its actual feasibility and long-term sustainability. These solutions currently constitute a system full of challenges that may decide its future. CEA systems allow producers to control factors such as temperature, wind, lighting, and/or rainfall. They also help increase crop yields while simultaneously reducing factors that may hinder plant growth, such as adverse weather conditions and common pests.

Over the last two decades, the application of CEA systems across all types of food cultivation has led to their increased use and to a rise in the production of fresh vegetables and fruits. For example, in the United States, CEA operations—including greenhouses, vertical farms, hydroponics, aquaculture, and other controlled production methods, including underground farming—have increased by over 100%, from 1476 operations in 2009 to 2994 in 2019. During the same period, agricultural output from these systems increased by 56%. Approximately 60–70% of CEA crops in both 2009 and 2019 were the most popular vegetables, i.e., tomatoes, lettuce, and cucumbers, with hydroponics being the most widely used method [144]. Higher yields can be achieved through vertical farming, which is also successfully applied in underground agriculture, where it contributes to achieving higher yields compared to traditional farming. For example, in conventional agriculture a 1 × 1 m field can produce about 3.9 kg of lettuce per year, while vertical farming can yield up to 12 times more on the same area [145]. Additional advantages of such cultivation include significant water savings, supported by irrigation methods such as drip irrigation. According to studies conducted in Arizona, the average water demand in hydroponic production was 13 ± 2.7 times lower compared to conventional production. However, the same studies showed that lettuce cultivation in hydroponic systems required as much as 82 ± 11 times more energy per kilogram compared to traditional cultivation [145].

The main energy costs are associated with lighting, heating, and cooling. Artificial lighting is indispensable in underground farming to ensure continuous year-round production. Some systems use it even 24 h a day, especially during the initial growth phases of plants, while others limit it to just a few hours per day [145,146]. Since CEA production facilities are usually located much closer to end consumers than traditional farms, products grown in these systems reach the market fresher and therefore have a longer shelf life than conventional products. This significantly reduces emissions related to long-distance transportation, minimizes waste and losses in the food chain, and consequently has a positive impact on the economics of the enterprise.

Local production and harvesting substantially reduce “food miles,” which positively affects transport costs and the carbon footprint. This is particularly important for fresh produce transport, as preservation through refrigeration generates high CO2 emissions [147]. In addition, the use of hydroponics or aeroponics for soil-free cultivation supports the supply of fresh produce despite the anticipated future shortage of land available for farming.

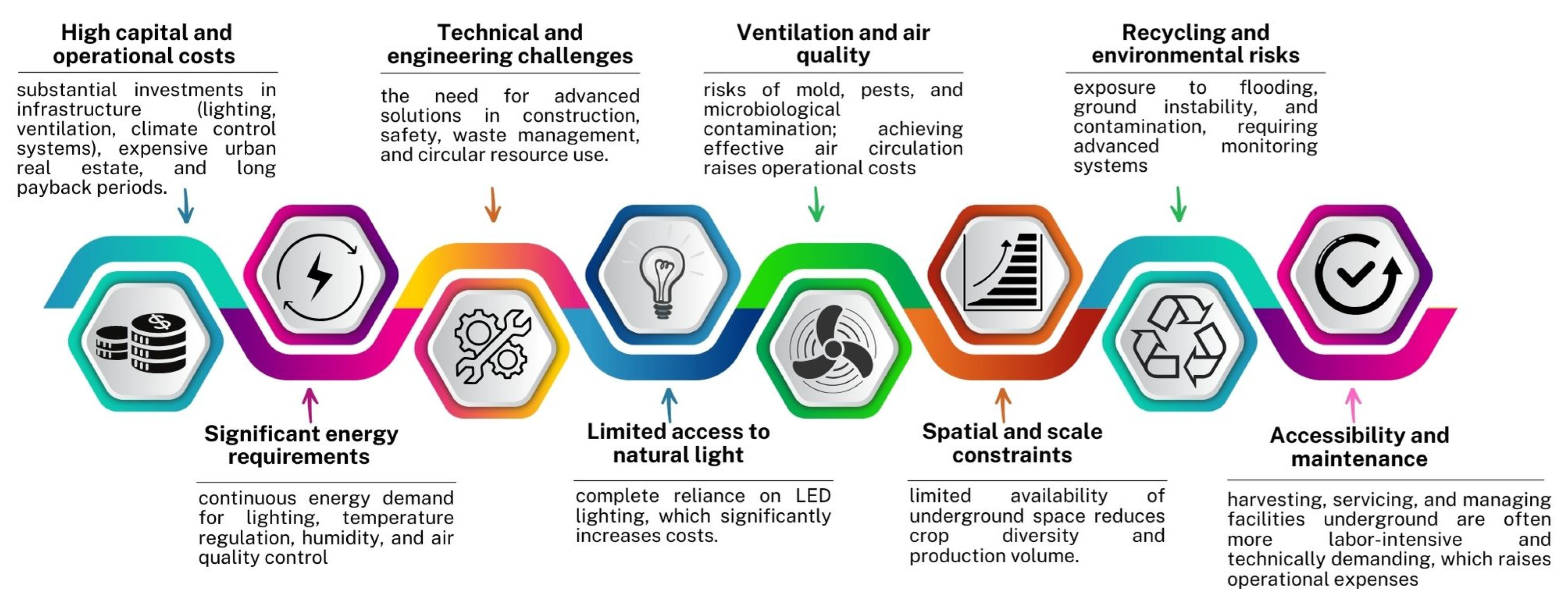

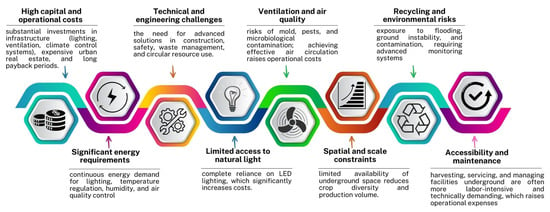

Underground farming, as a form of controlled environment agriculture (CEA), offers innovative solutions related to spatial constraints in cities and environmental challenges. Nevertheless, it also entails multidimensional difficulties that must be addressed to ensure its economic viability and sustainable development, including above all: high capital and operational costs, significant energy requirements, technical and engineering challenges, limited availability of natural light, ventilation and air quality issues, limitations in crop diversity and scale, recycling and environmental risks, as well as accessibility and maintenance [148,149]. Figure 12 presents the key challenges grouped into eight categories related to the economic viability of underground farming.

Figure 12.

Barriers to the Economic Viability of Underground Farming in a Controlled Environment System.

The analysis of examples of underground urban farms (see Section 3.2, Figure 6) shows that the economics of such investments depend primarily on the scale of production, the applied technology, and the additional social functions they perform or may perform in the future. Analyzing the data from Figure 6, it can be observed that production intensity ranges from as little as 15 kg·m−2·year−1 in the case of mushroom cultivation in Paris to over 210 kg·m−2·year−1 in a hydroponic farm in New York. Such a wide variation suggests that profitability is not a simple function of yield but also depends on added value—for example, niche products, short supply chains, or the local premium market. However, this issue is multifaceted and requires further in-depth economic analysis due to existing knowledge gaps. Moreover, projects such as Cycloponics in Paris or Cureghem Cellars in Brussels (see Figure 6) indicate actual profitability of production even at moderate production intensity. In addition, stable revenues for a company or organization can be achieved by linking this type of agriculture with spatial revitalization and the circular economy. Meanwhile, the Growing Underground farm in London (see Figure 6) demonstrates that local distribution can reduce transport costs, which may consequently compensate for high energy expenditures. As a result, under current technological and environmental conditions, the economics of underground food farms are shaped at the intersection of biological efficiency based on available urban space, while financial success depends both on an innovative business model and on the applied production technology.

In summary, although underground cultivation represents a promising solution to problems of urban agriculture such as limited land availability, water savings, and the shortening of supply chains, it faces significant challenges related to high energy demand, technical complexity, investment costs, and market acceptance. Overcoming these barriers requires the development of underground farming technologies, political support, and strategic planning. One possible solution for controlled environment agriculture, including underground farming, is to locate such cultivation sites in places with access to inexpensive renewable energy sources, such as solar, geothermal, or wind energy.

4. Discussion

Innovative solutions introduced in urban agriculture, particularly on food-producing underground farms, require an analysis of both the benefits and potential risks for cities and their inhabitants. In the near future, this type of agriculture may play a significant role in the creation of resilient and sustainable food systems, and its development will depend on many factors and potential for implementation through appropriate policy and an understanding of the system.

The assessment of the potential for multidimensional integration into urban space requires consideration of many aspects, including technological, environmental, planning, and social. Introducing underground farms may indirectly influence the urban climate due to the reduction in pollution emissions from transport through local production. Cities will also gain solutions supporting food supply systems for residents during crises. In addition, dialog and cooperation among residents working together in the framework of public–private partnerships and NGOs will be possible, which will help strengthen social participation and build social ties, regardless of social status. If such actions are reflected in planning and executive acts, they will allow the integration of urban policy with the city’s food, health, and educational policies.

Unused or even difficult-to-use areas, such as abandoned metro lines, old underground parking lots, bunkers, and post-industrial areas, which constitute a type of lost space, can be revitalized and returned to use. This will create a basis for building ecological awareness through education and learning about food-producing farms. Unfortunately, the lack of uniform regulations regarding solving infrastructure problems (e.g., ventilation, water, and electricity supply) and farm safety, as well as an insufficient number of specialists and companies specializing in this topic, causes many difficulties in the rapid implementation of such farms in the urban fabric. In addition, a limited understanding of the need to create such farms on the part of the administration, who does not perceive the spatial and ecological potential of this form of food production, creates barriers to the development of these initiatives. This situation may increase the risk of this business being taken over by private capital and the exclusion of residents’ participation in such projects.

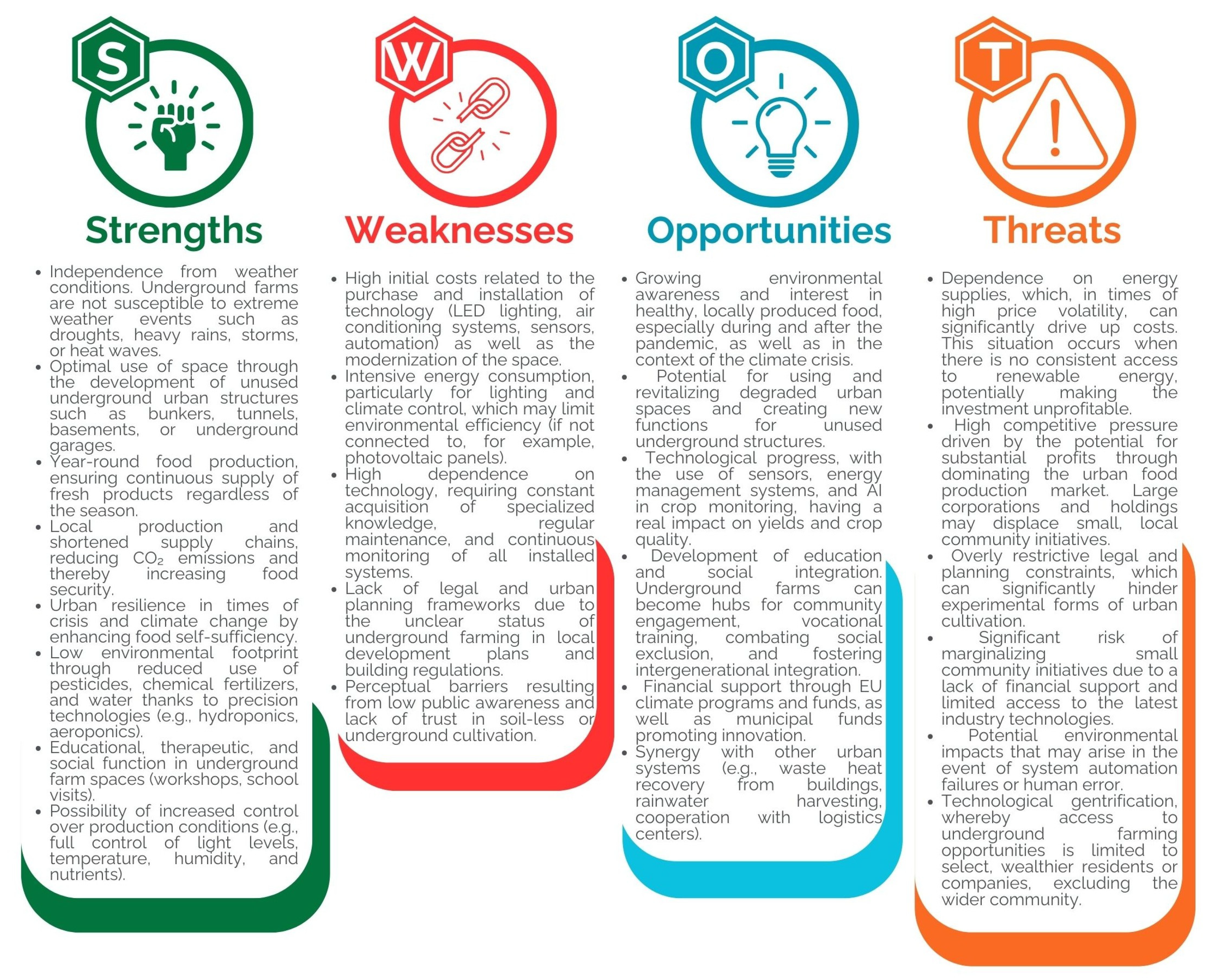

The SWOT analysis for underground food farms showed the challenges associated with transforming unused underground infrastructure into functioning critical structures related to the food security of cities. This analysis identified the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with integrating underground agriculture into urban metabolism, as well as climate–spatial policies, and their impact on environmental education and social participation of city residents (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

SWOT analysis of the potential for developing urban underground farms.

To systematize and assign priorities to the SWOT factors, the method of weighting was applied, where each element was assigned a specific weight and score (Table 1). This approach made it possible to calculate the indicative strength of influence of individual factors and to identify those that may have the greatest significance for further strategic analysis. Table 1 presents a synthetic summary of the data, while Annex S1 in Supplementary Materials contains the complete set of calculations. The most important strengths include the use of existing underground infrastructure in the city, the reduction in transport emissions (due to shorter distances in supplying food to consumers), and independence from weather conditions. These elements play a key role for logistics and the stability of food production in the city. Among the important weaknesses are the high investment and operational costs (CAPEX/OPEX), as well as the energy intensity of the systems, which in turn limit the scale of investments. Opportunities are mainly based on the energy transition and the possibility of integrating such projects with urban policies and the circular economy. The key threats include the risk of rising energy prices and insufficient social acceptance of new solutions in food production, stemming from the lack of awareness among city residents.

Based on the identified and weighted factors, a TOWS matrix was constructed, which helped generate 140 detailed strategies (72 in the SO quadrant, 35 in WO, 19 in ST, and 14 in WT). The table containing the full analysis, due to the size of the constructed matrix, is included in Annex S2 in Supplementary Materials, while the article itself presents only the super-result table (Table 2). This table provides a synthesis of the main strategic directions for each of the four quadrants of the TOWS matrix.

The results obtained from the analysis indicate that the greatest and most important potential for the development of underground urban farms lies primarily in the use of existing urban infrastructure (including infrastructure recovered through revitalization), as well as in energy symbiosis (SO strategy). WO-type strategies focus mainly on reducing costs and overcoming legal and social barriers. In the next quadrant—ST—the dominant actions are those that strengthen the resilience of production systems to various extreme events, such as energy and climate crises. Meanwhile, WT strategies focus mainly on minimizing operational risks and promoting the development of niche premium markets (Table 2, Annex S2 in Supplementary Materials). The TOWS matrix not only organizes the identified SWOT factors but also translates them into concrete action scenarios, ranging from the use of technical and urban infrastructure, through participation in the energy transition, to risk management and the development of specialized niches promoting food production in underground urban spaces. Thanks to this analysis, a picture of possible adaptation and implementation pathways for underground urban farms in urbanized areas was obtained.

From the perspective of an urban planner, underground farms can help activate degraded and effectively excluded, often inaccessible, or unused spaces, which is a type of urban recycling. This is an interesting example of the adaptive transformation of a problematic, unused space into a multifunctional, productive area that is useful to the broader public. Moreover, the potential of underground farms is currently being strengthened by great interest in autonomy and self-sufficiency. From a systemic perspective, underground farms fit into the Fourth Agricultural Revolution owing to new technologies such as AI, digitization, and automation.

The conducted analysis indicated relatively clearly that the implementation of underground farming in urban areas will require an integrated approach encompassing technological, planning, and social dimensions, where technical innovations will be combined with and complemented by the needs of city residents, ecological education, and the development of local cooperation.

Limitations and Future Directions

The presented analysis is exploratory in nature and represents an attempt to capture a new phenomenon in urban food systems through the development of underground food farms, which are only now beginning to be recognized in the dispersed body of literature and in urban practice. The limited availability of data and the diversity of research methods applied make these analyses introductory, serving as the beginning of a broader discussion on the phenomenon of underground food farming and an invitation to further, more in-depth studies that will make it possible to better understand its potential, conditions, and limitations. Many urban underground farm initiatives still operate at a pilot stage, as indicated in this paper, which makes it impossible to fully compare their environmental and economic performance with conventional production models. There is also a lack of standardized indicators regarding investment costs, energy and water use, and life-cycle emissions of such systems. These limitations, however, are constructive in nature, as they result from the novelty of the phenomenon, which is only beginning to take shape in cities and is increasingly recognized as a potential direction for the redevelopment and revitalization of degraded or underused urban areas. Their analysis helps define directions for future research. In the economic dimension, it is necessary to deepen the understanding of cost–benefit relationships between underground and aboveground farms, as well as to assess under what extreme conditions, such as climate crises, supply chain disruptions, or armed conflicts, investment in underground systems may become economically and strategically justified. It is also worth examining to what extent spatial factors, including the shortage of agricultural land in densely built-up cities, determine the need to develop underground farming, and how these systems can be scaled depending on the size, structure, and character of the city. Equally important is the social and cultural dimension, which so far has appeared only marginally in the literature. It requires reflection on the role of underground farms as places of ecological education, community building, and intercultural integration. It is also worth exploring whether underground farms can genuinely contribute to changing consumer attitudes and environmental awareness among urban residents, or whether they will remain a niche phenomenon limited to specific social groups.

Although this study does not yet exhaust the complexity of the subject, it points to an important new direction in research on the transformation of urban food systems. Despite data limitations and differences in technological maturity, underground farms are becoming laboratories of new thinking about urban resilience, locality, food security, and resource management in the era of climate crises. The limitations of this study are therefore also an invitation to further analyses in which interdisciplinary knowledge from urban, ecological, social, and economic fields can form a coherent basis for the evaluation and planning of this emerging and potentially crucial urban infrastructure.

5. Conclusions

Despite interest and emerging possibilities owing to the introduction of new technologies that can realistically support their functioning, underground food farms still do not occupy their right place in urban food systems or in urban strategies, policies, and spatial planning. Nevertheless, the results of the analysis clearly indicate that this type of agriculture is a real response to contemporary urban challenges, especially in the face of future global crises and wars.

Modern cities have ever-growing populations and occupy more living spaces, which often occur at the expense of green areas. Underground food farms offer a solution that can help not only on the proper functioning of cities in terms of food supply, but also survival during crises. Underground areas in cities represent a type of “reclaimed space,” which can be important for ensuring fair access to fresh food for residents. Because modern cities face systemic problems (spatial, economic, environmental, climatic, and population-related) and food-related challenges owing to many factors, underground farms can be considered a specific urban interface that is an infrastructural response for both times of prosperity and crisis. Therefore, underground food farms should be considered as critical structures supporting the city’s metabolism and infrastructure [69,70,73,123,148,149,150,151,152,153,154].

The application of modern hydroponic, aeroponic, and aquaponic technologies and introduction of automation and cultivation control systems in the underground areas of cities open up new opportunities for using areas that have thus far been marginalized. Unfortunately, despite its many advantages, the implementation of urban farms into city structures encounters several problems owing to the high initial costs of such investment and lack of legal regulations and technical standards that allow for its implementation. Low public awareness and lack of knowledge also make it difficult to embed this idea in people’s minds. Food production involves cash flow, which leads to the creation of large holdings that dominate this business and its commercialization, which may result in the exclusion of residents and social groups from these areas and limit their access. For this reason, one of the most important challenges when introducing this into a city’s food system is social participation in building a responsible and fair food production system. The authors noted that underground farms are not only innovative ideas but also symbols of modern thinking about contemporary urbanism, containing all the elements of a sustainable city, which strengthens environmental and social potential, providing a place for integration, environmental education, and the building of a climate-resilient urban fabric. The conducted research and analyses demonstrated both the potential and the limitations associated with implementing underground farming as an innovative component of Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) in urban conditions. According to the results obtained from the Weighted SWOT–TOWS analysis, the most significant strengths of underground farms were: the possibility of reusing existing infrastructure, the reduction in transport emissions, as well as independence from weather conditions during production. The threats and weaknesses of these systems are revealed primarily in the high investment and operational costs (not only at the start of the investment) and the considerable energy intensity and vulnerability to fluctuations in energy prices.

In addition, the Weighted SWOT–TOWS analysis made it possible to define three main strategic priorities for the development of underground farming in cities:

- Integration with urban circular economy systems through resource recovery and reuse;

- Strong linkages with renewable energy sources and urban energy transition strategies, which allow both the reduction in operational costs and the lowering of the carbon footprint;

- Continuous building of positive social perception of underground farms through diverse educational activities, by embedding them into local food strategies and the adaptation of cities to climate change.

To achieve this, the authors recommend universal frameworks for implementing underground farms in cities, which include the following:

- Actual integration of underground farms with strategic documents, including urban, climate, and food policies, as well as crisis response strategies and social participation.

- Creation of incentive systems and financial support for the construction and redevelopment of underground areas to implement underground farms in urban fabrics, as well as the possibility of obtaining investment relief and grants for social projects.

- Promotion of underground farm pilot projects covering various types of city undergrounds.

- Initiation of information campaigns to build ecological and educational awareness that allow the participation of city residents and the use of farms as spaces for creating joint cooperatives, eliminating social differences and barriers.

- Development of tools and forms for assessing the potential of implementing underground food farms in a given space and introducing them as analytical tools in urban design practices.

- Development of tools for assessing the environmental impact of food-producing underground farms.

Underground agriculture will not only complement the food chain but will also help redefine the role of agriculture in future urban spaces. These solutions and locations contribute to the redefining of the functional structure of the urban fabric, thinking not only horizontally but also downwards into the underground of cities, thereby reclaiming “lost surfaces.” By shifting the burden of food production underground, we can reclaim areas for development and use more areas on the surface for other purposes, allowing us to better shape green infrastructure, which can be reflected in the improvement of the city’s landscape quality. Therefore, underground farms can constitute an element of a city’s structure, invisible at first glance but essential, forming a critical infrastructure that strengthens cities’ resilience to climate change and, in times of crisis, provides security for food supply chains. Underground urban farms may, over time, become one of the key elements of critical infrastructure developed for ensuring urban food security, particularly in the context of supply chain disruptions and climate change. Due to the considerable difficulty of estimating economic conditions, including the current profitability of production, it appears necessary to conduct further research focused on developing realistic business models and governance frameworks for such investments, as well as on strengthening full social acceptance and understanding of the role of underground farms in the food supply chain. In this way, underground farming could evolve from a niche scale to large-scale solutions, applied widely and with benefits for the climate.

The findings may also support the development of policy frameworks for integrating underground farming into resilient and adaptive urban systems, contributing to future-oriented approaches in sustainable urban planning.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17219392/s1, Annex S1. Weighted SWOT—extended version with calculations; Annex S2. TOWS—Underground Urban Farms, Full list of SWOT factors. References [155,156,157] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., A.Z., M.A.-P. and H.J.; methodology, A.K., A.Z., M.A.-P., H.J. and M.G.A.C.; software, A.K. and A.Z.; validation, A.K., A.Z., M.A.-P., H.J. and M.G.A.C.; formal analysis, A.K., A.Z., M.A.-P., H.J., M.G.A.C. and L.A.V.C.; investigation, A.K., A.Z., M.G.A.C. and L.A.V.C.; resources, A.Z., A.Z., M.A.-P. and H.J.; data curation, A.K., M.G.A.C., A.Z. and L.A.V.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., M.A.-P., A.Z. and H.J.; writing—review and editing, A.K., A.Z., M.A.-P. and H.J.; visualization, A.K., L.A.V.C.; supervision, M.A.-P. and H.J.; project administration, A.K., A.Z. and M.A.-P.; funding acquisition, A.Z. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Centre for Research and Development (NCBR) under the DUT 2022 program, with a total budget of PLN 1,125,906.50. The project duration is from 1 February 2024 to 31 January 2027. A project titled as ‘Food production and provisioning through Circular Urban Systems in European Cities’ (FOCUSE) is being carried out at the University of Wrocław.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/assets/WUP2018-Report.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision—Key Facts; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/assets/WUP2018-KeyFacts.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- McPhearson, T.; Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N. (Eds.) Nature-Based Solutions for Cities. Edward Elgar Publishing. 2023. Available online: https://arhiv2023.skupnostobcin.si/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/nbs-for-cities.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Kousar, S.; Ahmed, F.; Pervaiz, A.; Bojnec, Š. Food Insecurity, Population Growth, Urbanization and Water Availability: The Role of Government Stability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaki, F.A.; Oteng-Abayie, E.F.; Baajike, F.B. Effects of Water, Energy, and Food Security on Household Well-Being. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Frantzeskaki, N. Perspectives on Urban Transformation Research: Transformations in, of and by Cities. Urban Transform. 2021, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Zhai, J.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, H.; Li, X. Impact of Urbanization on Water Resource Competition Between Energy and Food: A Case Study of Jing-Jin-Ji. Sustainability 2025, 17, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Kämper, R.; Kirby, C.K.; Specht, K.; Cohen, N.; Ilieva, R.; Caputo, S.; Schoen, V.; Hawes, J.K.; Poniży, L.; Béchet, B. The Role of Urban Agriculture in Food–Energy–Water Nexus Policies: Insights from Europe and the U.S. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 239, 104848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulterbrandt-Gragg, R.; Anandhi, A.; Jiru, M.; Usher, K.M. A Conceptualization of the Urban Food-Energy-Water Nexus (FEW) Sustainability Paradigm: Modeling from Theory to Practice. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macalou, M.; Keita, S.I.; Coulibaly, A.B.; Diamoutene, A.K. Urbanization and Food Security: Evidence from Mali. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1168181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Compte, M.; Burrola-Méndez, S.; Lozano-Marrufo, A.; Ferré-Eguiluz, I.; Flores, D.; Gaitán-Rossi, P.; Teruel, G.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Urban Poverty and Nutrition Challenges Associated with Accessibility to a Healthy Diet: A Global Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagi, M.; Bertrand, K.Z.; Bar-Yam, Y. The Food Crises and Political Instability in North Africa and the Middle East. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b68a4e4a2772c2a206180a1/t/5c0036b9c2241b0a1e7b5b56/1716920068415/food_crises.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- FAO. Urbanization Affects Agrifood Systems Across the Rural–Urban Continuum Creating Challenges and Opportunities to Access Affordable Healthy Diets. State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, FAO. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cc3017en/online/state-food-security-and-nutrition-2023/urbanization-affects-agrifood-systems.html (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Yuan, X.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Huang, S.; Chen, H.; Ao, X. Impacts of Global Climate Change on Agricultural Production. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T. Soil Degradation, Land Scarcity, and Food Security. Sustainability 2016, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turral, H.; Burke, J.; Faurès, J.M. FAO Report, Climate Change, Water and Food Security. FAO. 2008. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/i2096e/i2096e.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Xue, H.; Zhai, Y.; Su, W.M.; He, Z. Governance and Actions for Resilient Urban Food Systems in the Era of COVID-19: Lessons and Challenges in China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ušča, M.; Tisenkopfs, T. The Resilience of Short Food Supply Chains During the COVID 19 Pandemic: A Case Study of a Direct Purchasing Network. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1146446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E. Food Supply Chains During the COVID 19 Pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, B.T.; El Bilali, H. Conflict in Ukraine and the Unsettling Ripples: Implications on Food Systems and Development in North Africa. Agric. Food Secur. 2024, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, T.B.; El Bilali, H. Impact of the Russia–Ukraine War on Global Food Security: Towards More Sustainable and Resilient Food Systems? Foods 2022, 11, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin-Nashwan, S.A.; Hassan, M.K.; Muneeza, A. Russia–Ukraine conflict: 2030 Agenda for SDGs hangs in the balance. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2024, 40, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devecchi, M.; Ghersi, A.; Pilo, A.; Nicola, S. Landscape and Agriculture 4.0: A Deep Farm in Italy in the Underground of a Public Historical Garden. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matacz, P.; Świątek, L. The Unwanted Heritage of Prefabricated Wartime Air Raid Shelters—Underground Space Regeneration Feasibility for Urban Agriculture to Enhance Neighbourhood Community Engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatistas, C.; Avgoustaki, D.D.; Bartzanas, T. A Systematic Literature Review on Controlled-Environment Agriculture: How Vertical Farms and Greenhouses Can Influence the Sustainability and Footprint of Urban Microclimate with Local Food Production. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graamans, L.; Baeza, E.; van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Tsafaras, I.; Stanghellini, C. Plant factories versus greenhouses: Comparison of resource use efficiency. Agric. Syst. 2018, 160, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietze, V.; Alhashemi, A.; Feindt, P.H. Controlled-environment agriculture for an urbanised world? A comparative analysis of the innovation systems in London, Nairobi and Singapore. Food Secur. 2024, 16, 371–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueller, W.; Diem, C.; Hinterplattner, M.; Stangl, J.; Conrady, B.; Gerschberger, M.; Thurner, S. Propagation of Disruptions in Supply Networks of Essential Goods: A Population-Centered Perspective of Systemic Risk. 2022. Available online: https://pure.fh-ooe.at/ws/portalfiles/portal/56495967/2201.13325v1.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Savary, S.; Akter, S.; Almekinders, C.; Harris, J.; Korsten, L.; Rötter, R.; Waddington, S.; Watson, D. Mapping Disruption and Resilience Mechanisms in Food Systems. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 695–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Niu, N.; Li, D.; Wang, C. A Dynamic Evolutionary Analysis of the Vulnerability of Global Food Trade Networks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, E.; Helbig, R.; Avermaete, T.; Halliwell, K.; Calder, P.C.; Brown, L.R.; Ingram, J.; Popping, B.; Verhagen, H.; Boobis, A.R.; et al. Impacts of the Ukraine–Russia Conflict on the Global Food Supply Chain and Building Future Resilience. Eurochoices 2023, 22, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, T.M.; Voutilainen, M.; Helske, J.; Högmander, H. A Bayesian Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Markets During the Finnish 1860s Famine. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2022, 71, 1282–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkman, J. Managing Food Crises: Urban Relief Stocks in Pre-Industrial Cities of the Netherlands. Past Present 2021, 251, 41–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puma, M.J.; Bose, S.; Chon, S.Y.; Cook, B.I. Assessing the Evolving Fragility of the Global Food System. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 024007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffantini, G. Food insecurity and political instability during the Arab Spring. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähde, V.; Garschagen, M.; Romero-Lankao, P.; Müller, B.; Eakin, H.; Jäger, J. The Crises Inherent in the Success of the Global Food System. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Górecka, A.; Domagała, J. The Linkages between Crude Oil and Food Prices. Energies 2020, 13, 6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, G.; Algieri, B.; Kalkuhl, M.; von Braun, J. Drivers and triggers of international food price spikes and volatility. Food Policy 2014, 47, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, Y.; Misaki, E.; Casoni, G.; Fagiolo, G. Multiple Dimensions of Resilience in Agricultural Trade Networks. Q Open 2024, 4, qoae024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Bargawi, H. The 2007–2008 World Food Crisis: Focusing on the Structural Causes. Centre for Development Policy and Research. 2010. Available online: https://openresearch.lsbu.ac.uk/download/45988d6d5c5e02224178488e6c2fbd6ecf0b322f1340be066564e2ecc096480a/178808/The%202007-2008%20World%20Food%20Crisis.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Clapp, J. The 2007–2008 Food Crisis and the Global Governance of Food Aid. In Hunger in the Balance: The New Politics of International Food Aid; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubiello, F.N.; Salvatore, M.; Ferrara, A.; House, J.; Federici, S.; Rossi, S.; Biancalani, R.; Jacobs, H.; Flammini, A.; Prosperi, P.; et al. The Contribution of Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use Activities to Global Warming, 1990–2012. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 2655–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Leip, A. Food Systems Are Responsible for a Third of Global Anthropogenic GHG Emissions. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twine, R. Emissions due to Animal Agriculture—16.5% Is the New Estimate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, P.H. The Climate Crisis and Agriculture. Environ. Law Rep. 2022, 52, 10096. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, R. Soil Carbon Sequestration Impacts on Global Climate Change and Food Security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrao, C.; Strippoli, R.; Lagioia, G.; Huisingh, D. Water Scarcity in Agriculture: An Overview of Causes, Impacts and Approaches for Reducing the Risk. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Tang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wada, Y.; Yang, H. Global Agricultural Water Scarcity Assessment Incorporating Blue and Green Water Availibility Under Future Climate Change. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2020. In Overcoming Water Challenges in Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carwardine, J.; Martin, T.G.; Firn, J.; Reyes, R.P.; Nicol, S.; Reeson, A.; Grantham, H.S.; Stratfors, D.; Kehoe, L.; Chades, I. Priority Threat Management for Biodiversity Conservation: A Handbook. J. Appl. Ecol. Br. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 56, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andow, D.A.; Zwahlen, C. Assessing Environmental Risks of Transgenic Plants. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretty, J. Agricultural Sustainability: Concepts, Principles and Evidence. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 363, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R.; Marsden, T. Beyond the Divide: Rethinking Relationships between Alternative and Conventional Food Networks in Europe. J. Econ. Geogr. 2006, 6, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. In Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca6030en/ca6030en.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Barthel, S.; Isendahl, C. Urban Gardens, Agriculture, and Water Management: Sources of Resilience for Long-Term Food Security in Cities. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N. Why Farm the City? Theorizing Urban Agriculture through a Lens of Metabolic Rift. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattibene, D.; Recanati, F.; Dembska, K.; Antonelli, M. Urban Food Waste: A Framework to Analyse Policies and Initiatives. Resources 2020, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choochote, P.; Supakata, N. Urban Food Waste Generation and Sustainable Management Strategies: A Case Study of Nonthaburi Municipality, Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A.; FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention. In Food and Agriculture; Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulac, J.; Kristjansson, E.; Cummins, S. A Systematic Review of Food Deserts, 1966–2007. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2009, 6, A105. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.E.; Keane, C.R.; Burke, J.G. Disparities and Access to Healthy Food in the United States: A Review of Food Deserts Literature. Health Place 2010, 16, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebinck, A.; Selomane, O.; Veen, E.; de Vrieze, A.; Hasnain, S.; Sellberg, M.; Sovová, L.; Thompson, K.; Vervoort, J.; Wood, A. Exploring the transformative potential of urban food. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2021, 1, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, S.L.G.; Pineda-Martos, R.; Timpe, A.; Pölling, B.; Bohn, K.; Külvik, M.; Delgado, C.; Pedras, C.M.; Paço, T.A.; Ćujić, M.; et al. Urban Agriculture as a Keystone Contribution Towards Securing Sustainable and Healthy Development for Cities in the Future. Blue-Green Syst. 2020, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourichon, H. How Can Urban Food Policies Contribute to a Sustainable Economy? Lessons from London. DPU Working Paper Bartlett UCL. 2020. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/sites/bartlett/files/wp200_gourichon.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (MUFPP)—Framework for Action; Municipality of Milan. 2015. Available online: https://www.milanurbanfoodpolicypact.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Milan-Urban-Food-Policy-Pact-EN.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- City of Toronto. TransformTO Net Zero Strategy: 2024 Annual Report on Implementation Progress. 2025. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2025/ie/bgrd/backgroundfile-255754.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. Informe Anual IMU 2024—Memoria IMU 2024 (2024 Annual Report). 2025. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/instituturbanisme/sites/default/files/2025-06/EN-Memoria_IMU24_web.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- City of Copenhagen. Copenhagen Municipal Plan 2024—Abridged Version. 2025. Available online: https://kp24.kk.dk/copenhagen-municipal-plan-2024 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2021. Making Agrifood Systems More Resilient to Shocks and Stresses. 2021. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb4476en/cb4476en.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Urban Sustainability in Europe—What Is Driving Cities’ Environmental Performance? 2022. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/urban-sustainability-in-europe-what (accessed on 15 August 2025).