Abstract

This study constructs a comprehensive analytical framework for fire evacuation efficiency in high-rise buildings based on risk management theory, environment–behavior relationship theory, and stress-cognition theory. Through a systematic literature review and three rounds of Delphi expert consultation, a measurement questionnaire for fire-escape behavior was developed, ultimately screening out 35 key measurement items. Data were collected from 248 residents of high-rise residential buildings in Beijing who had experienced fires. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM) were employed to validate the model. The results show that the fire emergency management system (FEMS) and building-safety performance planning (BSPP) have a significant positive impact on escape response behavior (ERB), while situational panic psychological perception (SPPP) has a negative impact. The study also finds that emergency-response training and diversified escape-route design are key driving factors, and cognitive bias significantly affects situational panic psychological perception. This research provides empirical support for fire-escape management in high-rise buildings and develops a reliable measurement tool.

1. Introduction

With the continuous acceleration of urbanization, high-rise residential buildings have become the mainstream form of modern urban development, and the fire prevention and control situation has become increasingly severe accordingly. Globally, fires cause more than 300,000 deaths each year, and millions of people suffer permanent injuries [1]. According to the latest statistics, from January to August 2024, China had 660,000 fire accidents, resulting in 1324 deaths, 1760 injuries, and direct property losses of CNY 4.92 billion [2]. Among them, although high-rise building fires account for only 5.4% of the total number of fires, the death toll accounts for more than 15% [3], showing their unique high risk and severity.

The occurrence of fires often has significant suddenness and uncertainty, and people are prone to severe psychological panic in emergency situations, which seriously affects evacuation decision-making and behavioral efficiency. Especially for those who have experienced it firsthand, the high-rise living environment may become a source of anxiety and fear for a long time thereafter [4]. Therefore, it is an urgent need to improve the level of urban public safety to systematically conduct research on people’s psychology and behavior in fires and to formulate scientific and effective guidance and intervention strategies accordingly.

At present, significant progress has been made in the research on high-rise building fires in many key areas, including fire dynamics and smoke spread mechanisms, fire-resistant materials and structural design, risk assessment models, and intelligent alarm systems [1,5,6]. For example, the United States established a systematic building fire assessment framework early on [7]. The University of Science and Technology of China proposed a leading fire smoke movement composite model (CTST model) [8]. Muller et al. [9] developed an engineering tool (SCHEMA-SI) based on a dynamic hybrid model to assist fire engineers in conducting more reliable safety performance calculations. Wang et al. [10] demonstrated the development of an optimal phased evacuation strategy through the integration of smoke diffusion and personnel evacuation simulation in a 25-story high-rise building. Su et al. [11] applied variable fuzzy set theory and Bayesian networks to quantitatively assess and infer the risk sensitivity of electrical fires; Chen et al. [12] prioritized the emergency rescue capabilities of fire stations from five dimensions—personnel, equipment, environment, management, and funding—using the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Kusonwattana et al. [13] integrated structural equation modeling (SEM) and artificial neural networks to construct a theoretical model representing the self-efficacy and behavior mechanisms in fires. Wang et al. [14] established mixed Logit models and hybrid choice models to reveal the psychological latent variable mechanisms in evacuation path decision-making. Granda & Ferreira [15] constructed a fire risk index system from four dimensions—ignition, spread, evacuation, and firefighting. Shrahily & Albeera [16] demonstrated through simulation that a multi-exit coordinated strategy can significantly improve evacuation efficiency. Wang et al. [17] confirmed that rational building layout can reduce decision conflicts and clear signage can lower cognitive load, thereby improving evacuation path selection efficiency. Ronchi & Nilsson [18] established a fire risk evaluation framework applicable to different types of buildings through a literature review. Globally, authoritative standards and regulatory frameworks have further standardized fire safety practices. For instance, the U.S. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) developed NFPA 101®, the Life Safety Code®, which provides detailed requirements for evacuation route design, exit capacity, and emergency training in high-rise buildings [19]; The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) released ISO 23601:2020, focusing on the assessment of human behavior during fire emergencies and the optimization of evacuation strategies [20]; Additionally, the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) established EN 13501-1, which classifies the fire performance of construction materials and structural elements to support building safety planning [21]. These studies have provided solid support for the fire prevention design and risk management of high-rise buildings.

In this study, high-rise residential buildings are defined in accordance with the Code for Fire Protection Design of Buildings (GB 50016-2014, 2018 edition) [22], which specifies residential buildings with 10 or more floors and a height greater than 27 m. This definition aligns with the regulatory context of the study area (Beijing) and is consistent with the fire safety management practices of the Beijing Chaoyang District Fire and Rescue Detachment. It is important to note that there are differences in the definition of high-rise buildings internationally. For example, the U.S. NFPA 101® [19] defines high-rise buildings as those over 75 feet (≈22.86 m) in height. This study adopts the local standard to ensure the relevance of the research conclusions to the study objects. These standards provide a cross-national reference for the integration of management systems and building design, but the consistency between the regional evacuation behavior characteristics and the regional standards still lacks empirical verification. Despite the significant theoretical and technical foundations laid by the above achievements, existing research still has obvious limitations: most documents focus on the “material” level (such as engineering control and technical prevention), while the “human” factors—that is, the psychological and behavioral response mechanisms of people in fires—still lack systematic and in-depth discussions. Especially in emergency evacuation situations, how management measures, building environment, and psychological states interact to affect evacuation decisions and path selection is still lacking an integrated research framework to explain [23]. At the same time, although structural equation modeling (SEM) is theoretically suitable for characterizing complex causal relationships with multiple variables and latent variables, its application in fire evacuation behavior research is still in its infancy, with relatively few empirical documents, resulting in limited explanatory power for the formation mechanisms of behavior and also restricting the promotion value of related models in actual emergency management [14].

Based on this, this study takes improving the fire evacuation efficiency of high-rise buildings as the core goal, focusing on examining the interaction mechanisms of fire emergency management systems, building physical safety performance, situational panic psychological perception, and their impact paths on evacuation behavior and decision-making efficiency. This study integrates Delphi expert consultation (DM), exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM) to construct a measurement model with good reliability and validity, ensuring the systematic nature of the research process and the scientific nature of the conclusions.

The structure of this paper is arranged as follows: The second section conducts a literature review, summarizes the progress and deficiencies of existing research, and constructs a theoretical framework; the third section proposes a conceptual model and research hypotheses; the fourth section introduces the data sources and research design, and presents the empirical results; the fifth section discusses its practical significance in improving the evacuation efficiency of high-rise buildings; the last section summarizes the research findings, points out the limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Escape Response Behavior Mechanisms

Escape Response Behavior(ERB) refers to the series of reactions and decision-making processes that individuals or groups have in response to evacuation instructions or potential threats in the face of fires and other emergency events [24]. This behavior covers multiple links, from risk identification, escape decision-making, path selection, to coordination and interaction among people [24,25]. The research on ERB is not limited to fire situations, but can also be extended to any scenario that requires emergency evacuation [24], thus having cross-field practical value.

The factors affecting ERB are complex and diverse, mainly involving psychological and environmental variables, spatial structural characteristics, and organizational management mechanisms. At the psychological level, situational panic, anxiety, and cognitive biases that easily occur in emergency situations often lead individuals to make irrational evacuation choices, thereby reducing overall escape efficiency [24]. In terms of the building environment, the design of evacuation paths, exit layout, floor structure, and personnel density and other physical conditions directly shape individuals’ behavioral choices and flow characteristics [24]. In addition, organizational management factors, such as the implementation quality of emergency plans, the training level and guiding ability of staff, and the efficiency of hazard information dissemination, also significantly affect the performance of ERB [26]. Good emergency management and systematic training can help enhance individuals’ psychological resilience in disasters, suppress panic emotions, and promote orderly evacuation processes.

In summary, ERB is a complex behavioral system formed under high pressure, which is related to the psychological mechanisms of individual decision-making and is embedded in the physical environment of the building and the social interaction structure [27]. Conducting ERB research not only helps to improve emergency evacuation plans and enhance building safety levels, but also has important theoretical support and practical guiding significance for reducing casualties in disasters.

2.2. Key Factors Affecting Fire Evacuation Efficiency

The evacuation efficiency in high-rise building fires is a complex systemic problem involving the coupling of multiple elements and dynamic feedback [10]. Existing research shows that the key influencing factors can be summarized into four core dimensions: individual behavior characteristics, building environment attributes, situational panic psychology, and management response mechanisms.

Firstly, individual behavior performance is one of the key variables determining evacuation efficiency. In the context of fire emergencies, individuals’ initial reactions (such as recognizing alarm signals, confirming risks, searching for information, and alerting others and other pre-evacuation behaviors) often consume critical escape preparation time [28,29]. From a group perspective, herd behavior, decision-making lags, and structural congestion formed in exit areas also significantly affect the smoothness of the evacuation process [30]. In addition, individual attributes such as age, physical activity level, and previous disaster experience also affect their decision-making logic and mobility under stress, resulting in significant differences in evacuation behavior performance [31].

As the physical carrier of the evacuation process, the building environment directly affects the safety of evacuation paths and the possibility of passage. Its spatial structural parameters, such as corridor width, staircase settings and layout, and exit capacity, are the basic factors that restrict the efficiency of human flow movement [32]. Narrow passages or insufficient exits can easily induce bottleneck effects, thereby significantly reducing overall evacuation efficiency [33,34]. At the same time, the dynamic characteristics of fire smoke spread, heat release rate, and the effectiveness of fire compartments and other fire dynamics elements will also significantly increase the uncertainty and danger of the evacuation environment, making escape behavior face greater challenges [35].

Situational panic is a key psychological driving force in fire evacuation, and its impact extends far beyond the emotional level. Panic emotions can easily lead to the depletion of individual cognitive resources and a decline in executive functions, thereby triggering maladaptive escape decisions [36] (for example: blindly following, excessive backtracking [37,38]). Ouyang et al. [39] found that individual personality traits also significantly affect their behavioral patterns under stress. For example, in high-rise building fires, calm individuals are more likely to actively formulate escape strategies, while those with high anxiety traits are more prone to herd behavior and stagnation, which in turn affects the improvement of overall evacuation efficiency.

Finally, the management and emergency-response mechanisms, as the “central processor” of the emergency evacuation system, play a coordinating and decisive role in practice [40]. Its core includes the reliability of the emergency system, the response speed of fire rescue forces, and the soft elements of on-site command and coordination among multiple departments [41,42]. These capabilities directly affect whether evacuation actions can be carried out quickly and orderly. At the same time, the daily operation and maintenance level of the building (such as the integrity of fire protection facilities, hidden danger identification and rectification mechanisms, etc.) also constitutes an important basic support, profoundly affecting the actual effectiveness of emergency measures during disasters [43]. Notably, global regulatory frameworks such as NFPA 101 [19] emphasize the integration of “systematic training” and “dynamic risk assessment” into daily management, which aligns with the core dimensions of the Fire Emergency Management System (FEMS) in this study. However, regional variations exist in the implementation of these standards. For example, EN 13501-1 [21] imposes stricter requirements on exit width compared to Chinese national standards, highlighting the need to adapt building-safety performance planning to local contexts.

The above findings can be incorporated into three theoretical frameworks for interpretation: The stress-cognition theory from the perspective of psychology emphasizes the cognitive evaluation and coping patterns of individuals under pressure situations, providing an interpretative path for understanding the impact of panic, anxiety, and cognitive biases on escape decisions in fires [41,44]; The environment–behavior relationship theory reveals the shaping role of spatial environment on human behavior choices, providing theoretical support for analyzing the impact of building layout, exit settings, and human flow characteristics [44,45]; Risk management theory focuses on the processes of risk identification, assessment, and response, emphasizing the role of emergency management systems, training mechanisms, and resource allocation in disaster response [46,47]. Based on the integration of the above theories, this study will construct a theoretical framework and core constructs for personnel escape behavior in high-rise building fires in the next section and propose corresponding hypotheses.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Variable Definition

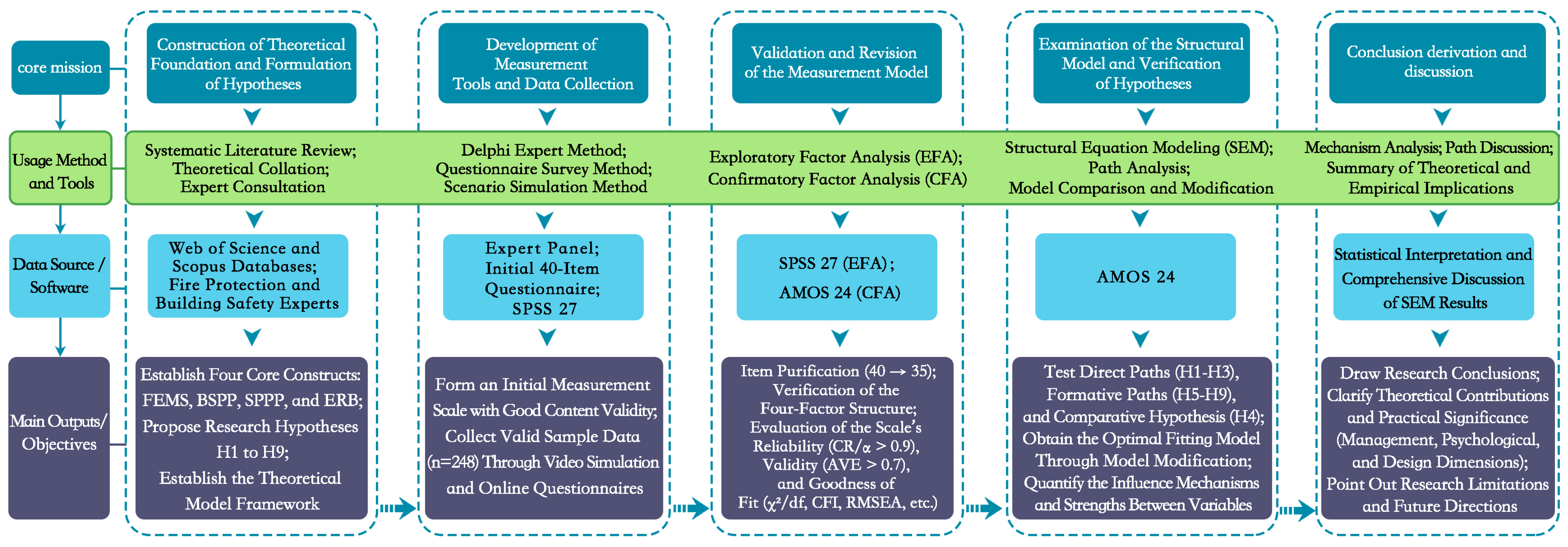

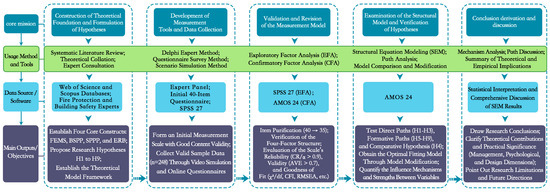

This study adopts an empirical research design, aiming to systematically explore the key factors affecting personnel escape efficiency in high-rise building fires through quantitative methods. The research process is shown in Figure 1. Based on the previous literature review and expert consultation, this study initially proposes an analytical framework covering four core theoretical domains to explore the key factors affecting personnel escape efficiency in high-rise building fires. These four preliminary theoretical domains include: fire emergency management system (FEMS), building-safety performance planning (BSPP), situational panic psychological perception (SPPP), and escape response behavior (ERB).

Figure 1.

Research framework.

Among them: FEMS is based on risk management theory, emphasizing the role of emergency systems, training mechanisms, and resource coordination in risk response and escape efficiency improvement; BSPP is rooted in the environment–behavior relationship theory, highlighting the key influence of building spatial layout and safety performance in shaping personnel evacuation paths and crowd flow; SPPP draws on stress-cognition theory, revealing the psychological response mechanisms of individuals in fire situations due to panic, anxiety, and cognitive biases; ERB serves as the dependent variable, comprehensively reflecting the combined results of psychological, environmental, and management factors on actual escape behavior.

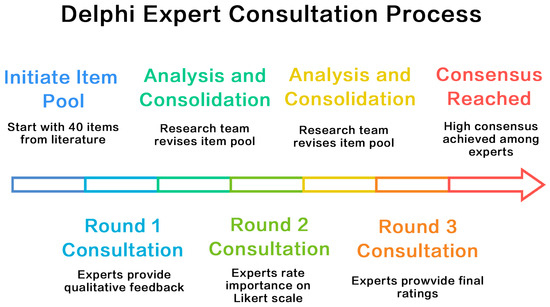

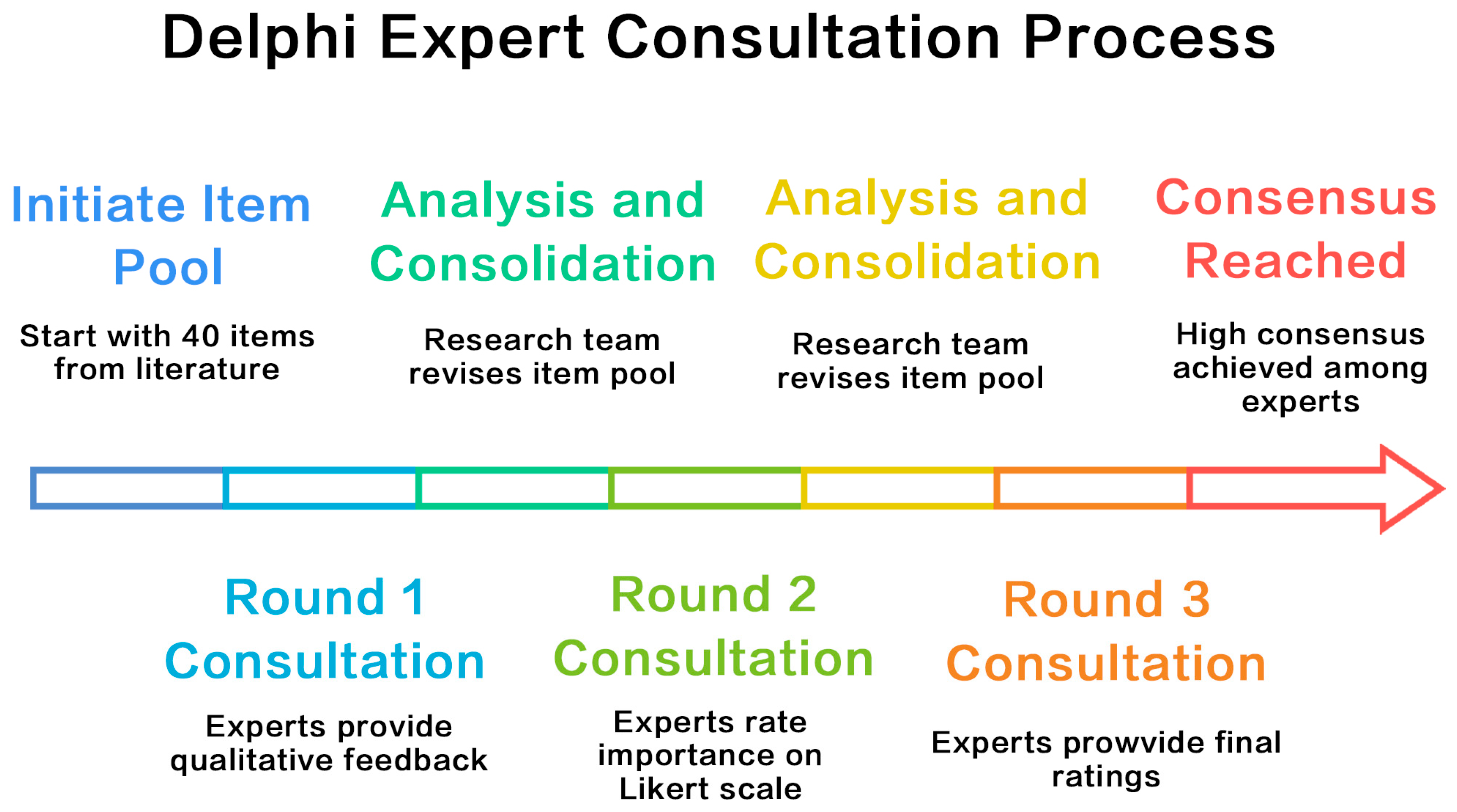

To ensure the scientific nature and effectiveness of the measurement tools, this study adopts a dual-path optimization of measurement items through “systematic literature review—Delphi iteration”. First, based on the Web of Science and Scopus, two major core databases, a systematic search and screening of literature on “high-rise escape”, “building safety”, and “fire management” in the past five years were conducted. After excluding qualitative studies and review articles, 46 high-level empirical studies were extracted, and 40 potential influencing factors were identified. Subsequently, relying on a professional team composed of senior experts from the Chaoyang District Fire Rescue Brigade in Beijing and five professors of industrial design, a three-round Delphi expert consultation was initiated (see Appendix B). Expert selection followed three core criteria: (1) Professional Background: Fire emergency management experts were required to have no less than 10 years of frontline rescue or supervisory experience; academic experts in industrial design and building safety were required to have no less than 8 years of relevant research experience. (2) Qualifications: Fire safety experts must hold senior professional titles (e.g., senior engineer or above) or occupy key managerial positions; academic experts must have led fire-safety-related research projects or published no fewer than five papers in high-level journals. (3) Representativeness: The expert panel was designed to cover the three perspectives of “practice, regulation, and academia”. To avoid conflicts of interest, individuals with direct commercial ties to the research outcomes (e.g., employees of building material suppliers) were explicitly excluded. Initially, five fire emergency management experts and six experts in industrial design and building safety were included. Through multiple rounds of feedback and revision, a set of measurement items with high content validity and theoretical fit was finally established (specific items are shown in Table 1, and the complete questionnaire is detailed in Appendix A).

Table 1.

Design of the influencing factor scale.

All items in this study used a Likert nine-point scale. Among them, 1 point indicates “strongly disagree/significantly hinders fire evacuation efficiency”, 9 points indicate “strongly agree/significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency”, and 5 points indicate a “neutral attitude”. The scale design not only accurately captures respondents’ psychological perceptions and behavioral tendencies but also provides sufficient variability and reliability for subsequent empirical analysis.

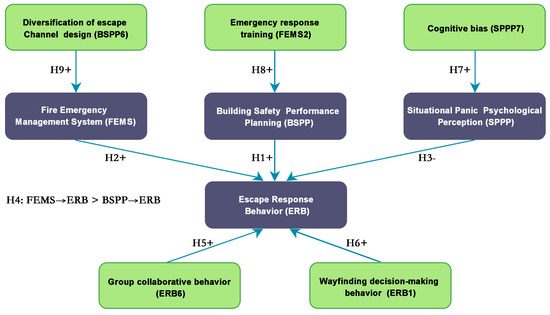

3.2. Research Model and Hypothesis

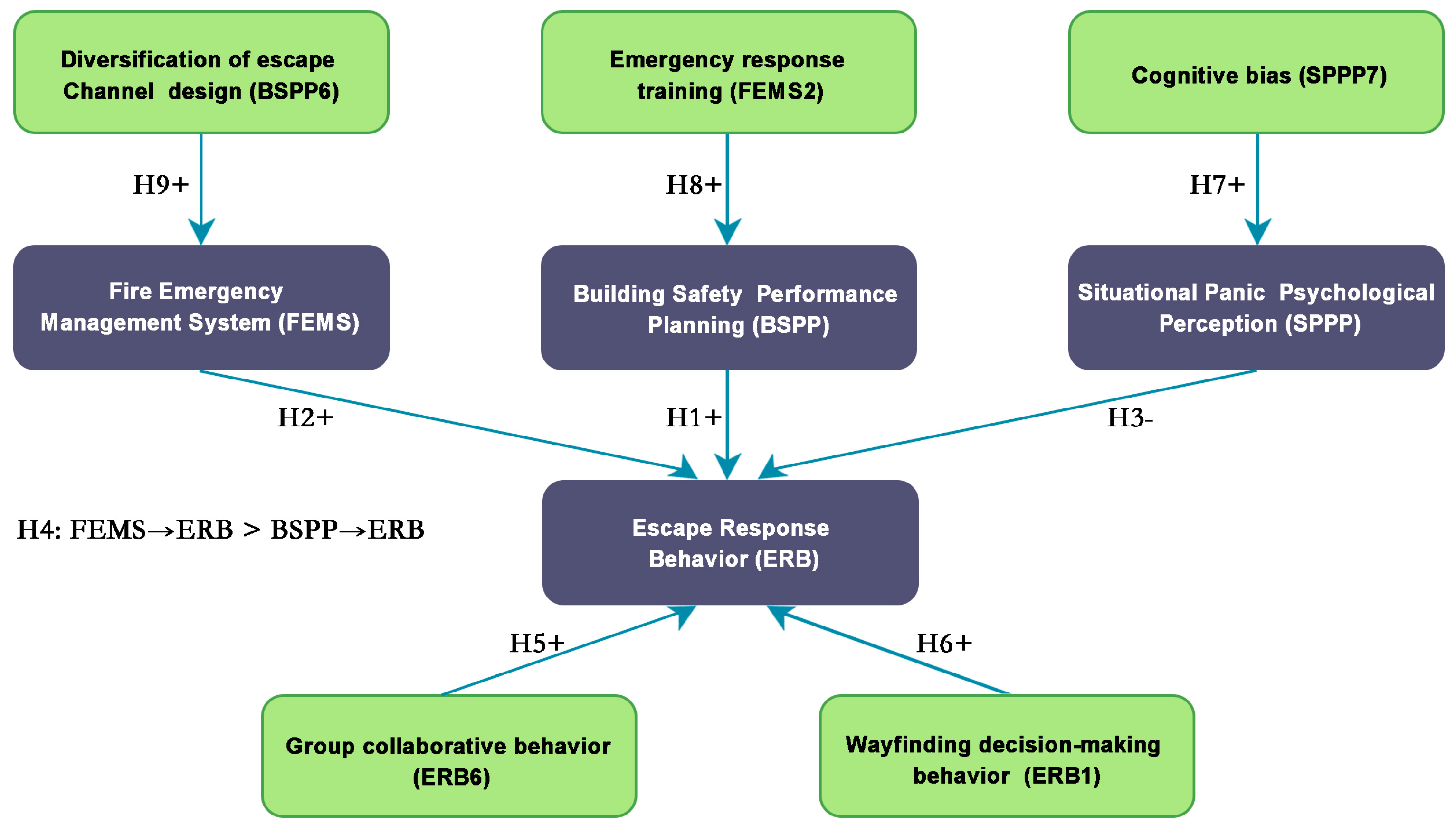

Based on the systematic review of the factors affecting escape in the previous section, this study integrates stress-cognition theory, environment–behavior relationship theory, and risk management theory from psychological, environmental, and management aspects to construct an analytical framework for personnel escape behavior in high-rise building fires. The framework posits that individuals’ psychological stress responses (SPPP), building environment attributes (BSPP), and fire emergency management mechanisms (FEMS) jointly affect escape response behavior (ERB), and their causal relationships are reflected through direct paths, comparative paths, and formative indicators (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The research model.

Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

- Direct Paths Hypotheses:

H1.

The fire emergency management system (FEMS) has a significant positive impact on escape response behavior (ERB).

H2.

Building-safety performance planning (BSPP) has a significant positive impact on escape response behavior (ERB).

H3.

Situational panic psychological perception (SPPP) has a significant negative impact on escape response behavior (ERB).

- Comparative Hypothesis:

H4.

The impact of the fire emergency management system (FEMS) on improving escape response behavior (ERB) is greater than that of building-safety performance planning.

- Formative Paths Hypotheses:

H5.

Group collaborative behavior (ERB6) has a significant positive impact on escape response behavior (ERB).

H6.

Wayfinding decision-making behavior (ERB1) has a significant positive impact on escape response behavior (ERB).

H7.

Cognitive bias (SPPP7) has a significant positive impact on situational panic psychological perception (SPPP).

H8.

Emergency response training (FEMS2) has a significant positive impact on the fire emergency management system (FEMS).

H9.

Diversification of escape Channel design (BSPP6) has a significant positive impact on building-safety performance planning (BSPP).

3.3. Data Collection

This study employs a combination of face-to-face interviews and online questionnaires to conduct surveys in multiple high-rise residential communities in Chaoyang District, Beijing, with ordinary high-rise residential residents and individuals who have experienced fires as the main targets. In the face-to-face interview stage, the research team played a 3–5-min fire simulation video to the respondents face-to-face and explained the issues involved in the video to enhance their immersion and sense of authenticity through situational simulation. Subsequently, online questionnaires were used for data collection to ensure that respondents answered based on a full understanding of the fire situation, thereby improving the authenticity and reliability of the data.

The questionnaire consists of two parts: The first part includes six questions on demographic information, involving gender, age, education level, occupational category, severity of fire experience, and whether they have received psychological or medical assistance. The second part contains the core measurement items, with 40 questions covering the four core constructs of FEMS, BSPP, SPPP, and ERB. All items are scored using a Likert nine-point scale, where 1 point indicates “strongly disagree/significantly hinders escape efficiency”, 9 points indicates “strongly agree/significantly improves escape efficiency”, and 5 points indicates a “neutral attitude”. The scale design aims to effectively capture the differences in respondents’ psychological perceptions and behavioral evaluations while ensuring the measurability of variables and the variability of data.

This study adopted a stratified convenience sampling method, first selecting eight high-rise residential communities with different building ages (5–20 years) and residential densities in Chaoyang District, Beijing. Questionnaires were distributed through community property recommendations and on-site invitations, with a total of 481 questionnaires distributed. After excluding respondents who had not experienced fires and invalid questionnaires (e.g., incomplete answers, consistent scores for all items), a final effective sample of 248 was determined, with an effective recovery rate of 51.56%. All respondents had personal fire experiences. It is important to note that this sampling method is limited by regional and accessibility conditions, so the sample may not fully represent the population of all high-rise residential residents in China. The generalizability of the results needs to be verified through subsequent multi-regional studies. The sample characteristics are shown in Table 2: Males accounted for 73.0%, and females accounted for 27.0%; the age distribution was mainly dominated by the 25–40 years old group (50.0%) and the 12–24 years old group (44.4%), with those aged 41 and above accounting for 5.6%. In terms of education level, individuals with high school and above accounted for 92.8%, among which those with a university degree accounted for 62.1%, indicating that the respondents had a good understanding ability, ensuring the reliability of the questionnaire data. In terms of occupational background, more than half of the respondents (58.9%) were engaged in fire management-related work. In terms of the severity of fire experience, nearly half of the respondents (49.2%) had experienced severe fires, 46.8% had experienced mild fires, and those who had experienced moderate fires accounted for a relatively low proportion (4.0%). In addition, 49.2% of the respondents indicated that they had received psychological or medical assistance after the disaster. The sample of this study covers a wide range of background characteristics and fire experiences, providing a valuable empirical basis for exploring escape behavior and response mechanisms in high-rise building fires.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics (n = 248).

4. Results

4.1. FA Results and Measurement Model Validation

Factor Analysis (FA) is an important statistical method in psychology, management, and behavioral sciences for revealing the latent structure of observed variables. Its core objective is to simplify complex data systems and construct interpretable measurement models by extracting common factors and identifying the underlying association patterns among variables [72,73]. To systematically examine the structural validity of the four core constructs-FEMS, BSPP, SPPP, and ERB—proposed in this study based on literature review and theoretical framework, a two-stage factor analysis strategy was employed: exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), to ensure the reliability, convergent validity, and theoretical rationality of the measurement tools.

4.1.1. EFA Results

EFA is an exploratory method used to discover latent structures, suitable for the early stages of scale development or when theoretical constructs are not well-defined. It aims to identify the covariation among variables and extract interpretable factor dimensions [74]. To assess the operability and structural rationality of the theoretical constructs, EFA was first conducted on the 40 observed items in the original questionnaire. The data analysis was completed using SPSS 27.0 software, with principal component analysis (PCA) used to extract initial factors and varimax rotation applied to enhance the interpretability of the factor loading matrix [75,76].

Before conducting the EFA, the suitability of the data was tested. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.943, and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 10,240.680, df = 595, p < 0.001), indicating a strong linear correlation among variables and suitability for factor analysis [77,78]. Meanwhile, the overall scale Cronbach’s α coefficient reached 0.928, well above the recommended threshold of 0.7 [78], indicating high internal consistency and good reliability among the items. see Table 3 for details.

Table 3.

Credit and validity test results.

After six iterations of Kaiser normalized varimax rotation, five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were finally converged, cumulatively explaining more than 70% of the variance [77,79]. Items with factor loadings below 0.7 (including SPPP8, ERB9) were eliminated, and factors with fewer than three items (including SPPP9, BSPP9, BSPP10) were deleted, resulting in the retention of 35 items.

The final factor structure is as follows (see Table 4 for details):

Table 4.

Principal component analysis results.

Factor 1 (FEMS): 12 items, factor loadings ranging from 0.826 to 0.916, eigenvalue 13.268, variance explained 10.162%; Factor 2 (BSPP): 8 items, factor loadings ranging from 0.801 to 0.921, eigenvalue 6.982, variance explained 6.454%; Factor 3 (ERB): 8 items, factor loadings ranging from 0.783 to 0.854, eigenvalue 4.818, variance explained 5.647%; Factor 4 (SPPP): 7 items, factor loadings ranging from 0.764 to 0.857, eigenvalue 2.672, variance explained 5.477%.

4.1.2. CFA Results

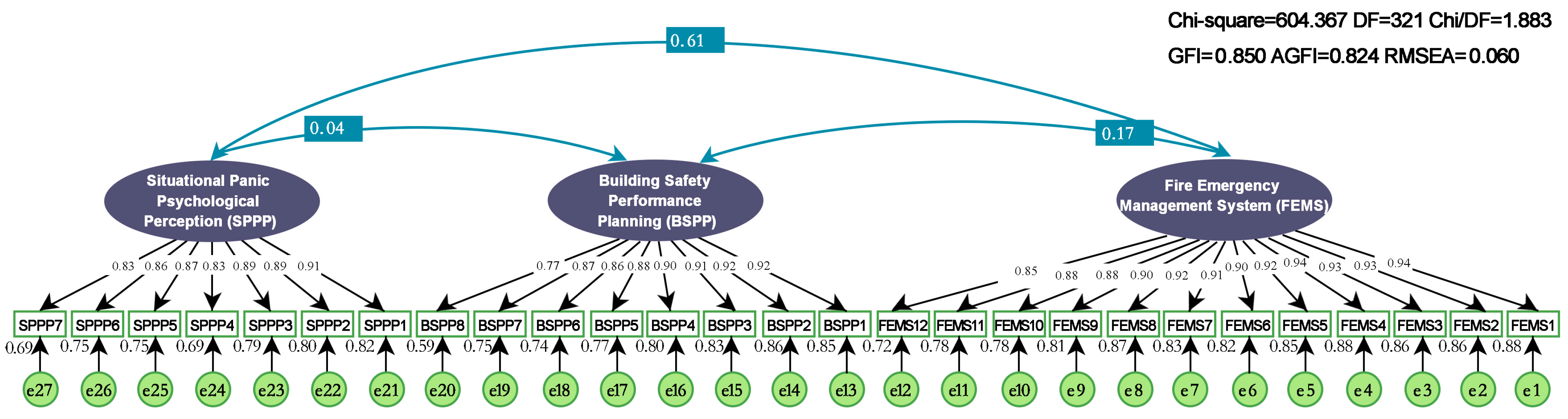

To further verify the theoretical rationality and statistical robustness of the factor structure obtained from EFA, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS 24.0 software. CFA, as a covariance-based modeling technique, is primarily used to test whether the pre-specified multidimensional measurement model matches the actual observed data, thereby confirming the convergent validity, discriminant validity, and overall fit of the constructs [80]. It is important to emphasize that CFA is not used to determine causal relationships among variables, but to validate the effectiveness of the measurement model, i.e., whether the relationship between observed variables and latent variables meets theoretical expectations [81].

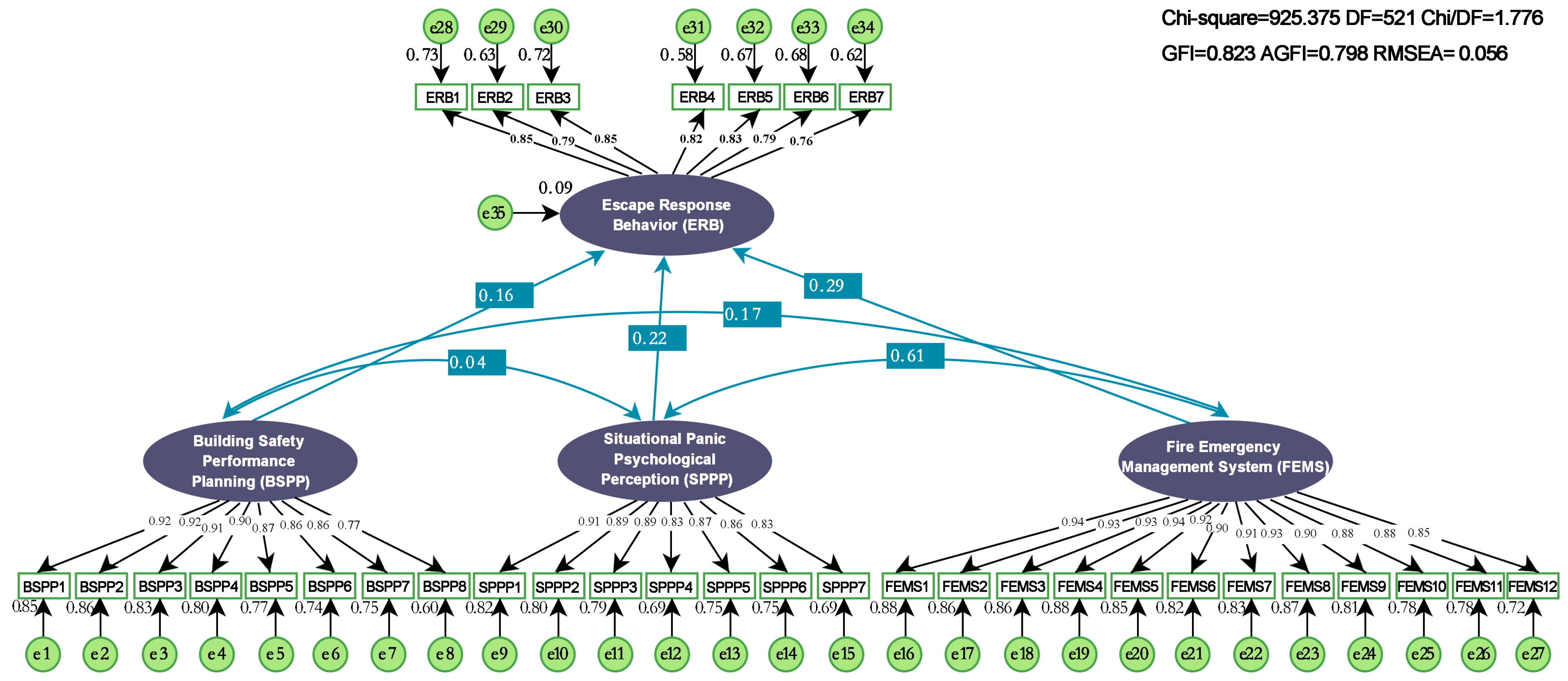

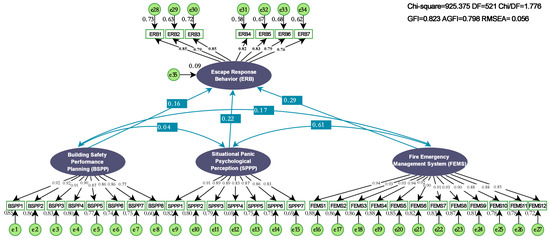

In this study, based on the EFA results and existing theoretical framework, a four-factor measurement model containing FEMS, BSPP, SPPP, and ERB was constructed (see Figure 3). Among them, FEMS, BSPP, and SPPP were set as exogenous latent variables (predictors), while ERB was set as the endogenous latent variable, representing the emergency-response behavior of individuals in fire situations and the outcome variable of interest in this study.

Figure 3.

Independent variable factor model of fire-escape efficiency in high-rise buildings.

The CFA results showed (see Table 5) that the standardized factor loadings of all observed variables on their corresponding latent variables ranged from 0.771 to 0.936, all passing the t-test (p < 0.001), meeting the convergent validity criterion of >0.70 proposed by Hair et al. (2019) [82]. The composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.956 to 0.983, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.755 to 0.828, both exceeding the critical values of 0.70 and 0.50 recommended by Fornell & Larcker (1981) [83], confirming the excellent convergent validity of each construct.

Table 5.

Results of CFA.

More importantly, the overall model fit indices showed excellent performance (see Table 6): χ2/df = 1.883 (<3), RMSEA = 0.060 (<0.08), RFI = 0.925, NFI = 0.932, CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.964, PNFI = 0.852. These indicators all met the criteria recommended by Hu & Bentler (1999) [84] and Byrne (2016) [80], indicating that the four-factor model had a good fit with the sample data.

Table 6.

Fitting the degree of the confirmatory factor model.

4.2. SEM Construction and Model Validation

Although exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses effectively revealed the measurement structure and reliability and validity of the constructs related to fire-escape behavior in high-rise buildings, they mainly stayed at the measurement level of “observed variables → latent variables” and could not deeply examine the causal relationships and effect paths among latent variables. Therefore, this study further adopted structural equation modeling (SEM) to make the transition from the “measurement model” to the “structural model” [85].

SEM, as a multivariate statistical method that integrates measurement and structural model testing, can not only assess the relationship between observed variables and latent variables (i.e., the confirmatory factor analysis part) but also test the direct and indirect effects among latent variables and even construct higher-order factor structures based on controlling measurement errors. This allows for a more comprehensive revelation of the intrinsic mechanisms of complex behavior systems [86]. Compared with traditional regression analysis, SEM has the advantages of dealing with latent variables, multiple indicators, and overall model fit assessment, making it particularly suitable for the multidimensional theoretical framework involving the interaction of psychological perception, management effectiveness, and physical environment in this study [80,87].

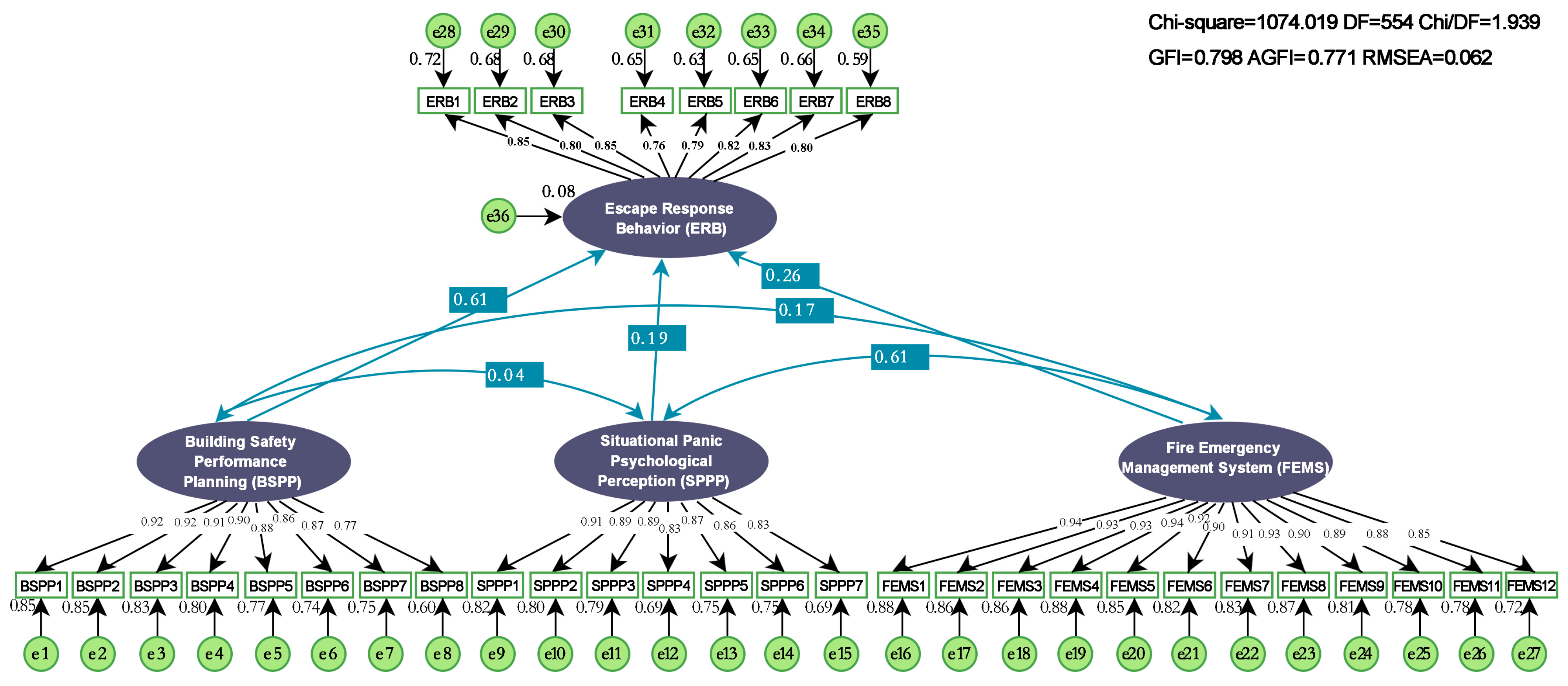

Based on the measurement model established by the previous EFA and CFA, this study adopted a two-stage modeling strategy: First, a first-order SEM model was constructed, with FEMS, BSPP, and SPPP as exogenous latent variables (independent variables) and ERB as the endogenous latent variable (dependent variable), to test the direct impact paths of the three on ERB; on this basis, combined with model modification indices (modification indices) and theoretical logic, a second-order factor model was further developed to capture higher-level latent structural characteristics and enhance the explanatory power and fit of the model [88].

4.2.1. First-Order SEM Model Construction

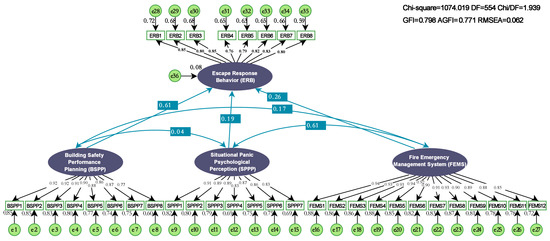

Based on the validated measurement model (CFA), this study further constructed a structural equation model (SEM) to test the causal relationships among latent variables in the fire-escape efficiency model of high-rise buildings. Based on the established factor structure, ERB was set as the endogenous latent variable (i.e., dependent variable), and its observed variables ERB1–ERB8, were included in AMOS 24.0 software to construct the first-order structural model (first-order SEM). The model aimed to examine the direct impact paths of FEMS, BSPP, and SPPP, three exogenous latent variables, on ERB, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

First-order model of response efficiency for high-rise building fire-escape behavior.

The model fit results are shown in Table 7. The results indicate that the first-order model fits well overall: χ2/df = 1.939 (<3.0), RMSEA = 0.062 (<0.08), NFI = 0.900, CFI = 0.949, TLI = 0.945, PNFI = 0.838, all meeting the criteria recommended by Hu & Bentler (1999) and Byrne (2016) [80,84]. However, the normed fit index (RFI) was 0.893, slightly below the recommended threshold of 0.90, indicating that there is still room for optimization in the model’s structural stability and internal consistency.

Table 7.

Fitting degree of SEM models at different levels.

To further improve the model fit, this study conducted diagnostic analysis based on modification indices (modification indices, M.I.). The results showed that the M.I. value between error terms e31 (ERB4: stimulated response) and e32 (ERB5: physiological response perception) was as high as 70.805, suggesting that there may be a higher-order factor or measurement overlap not captured by the model [89]. This phenomenon implies that the “stimulated-physiological” response of individuals in fire situations may constitute a higher-level psychological-behavioral dimension. Therefore, to further enhance the model’s explanatory power and theoretical depth, the study decided to construct a second-order factor model (second-order factor model) to integrate such potential higher-order structures [90].

4.2.2. Second-Order SEM Fit and Modification

To systematically optimize the theoretical model and improve its fit with empirical data, this study followed the standard structural equation modeling process, constructing and comparing first-order, initial second-order, and final second-order models. The fit indices of the models are shown in Table 7.

The initial first-order model already showed an acceptable fit level: χ2/df = 1.939 (<3), RMSEA = 0.062 (<0.08), NFI = 0.900, CFI = 0.949, TLI = 0.945. However, its RFI index (0.893) was slightly below the strict standard of 0.90, indicating that there was local misfit in the model, which had room for optimization [85]. By examining the modification indices (MI) and combining theoretical considerations, this study first attempted to delete the observed variable “ERB4” with relatively low factor loadings and possible theoretical overlap, constructing the initial second-order model. This adjustment led to an initial improvement in model fit: χ2/df decreased to 1.818, RMSEA decreased to 0.058, and RFI increased to 0.902. NFI increased to 0.909, CFI and TLI also increased to 0.957 and 0.954, respectively, indicating that the model’s parsimony and fit had both been enhanced.

To further pursue the best model, in the subsequent analysis, “ERB4” was restored, and “ERB5,” which had more significant problems indicated by the modification indices and was more theoretically independent, was deleted, forming the final second-order model. This step brought about a comprehensive improvement in fit: χ2/df further decreased to 1.776, RMSEA decreased to 0.056, and RFI (0.904), NFI (0.911), CFI (0.959), and TLI (0.956) all reached or exceeded the recommended standards [84]. This result indicates that the final model not only fits the data very well but also has better parsimony and theoretical consistency. Based on the optimized parameter estimates, the final second-order model structure is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Second-order model of response efficiency for high-rise building fire-escape behavior.

4.2.3. Path Discussion and Mechanism Analysis

The results of structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis (Table 8) show that all research hypotheses were supported by empirical evidence.

Table 8.

Path coefficients and hypothesis testing results.

In terms of direct path effects, the fire emergency management system (FEMS) had a significant positive impact on escape response behavior (ERB) (β = 0.274, p = 0.001), confirming Hypothesis H1. Building-safety performance planning (BSPP) also had a significant positive impact on escape response behavior (ERB) (β = 0.164, p = 0.013), confirming Hypothesis H2. In contrast, situational panic psychological perception (SPPP) had a significant negative impact on escape response behavior (ERB) (β = −0.199, p = 0.017), confirming Hypothesis H3.

The comparative hypothesis test showed that the path coefficient of the fire emergency management system (FEMS) on escape response behavior (ERB) (0.274) was significantly greater than that of building-safety performance planning (BSPP) (0.164). This difference was confirmed by the chi-square difference test (Δχ2(1) = 5.32, p = 0.021), thus supporting Hypothesis H4.

The formative path analysis further revealed the key drivers within each core construct:

Group collaborative behavior (ERB6) had a very strong positive formative effect on escape response behavior (ERB) (β = 0.816, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H5.

Wayfinding decision-making behavior (ERB1) was the most critical predictor of escape response behavior (ERB) (β = 0.852, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H6.

Cognitive bias (SPPP7) made a significant contribution to the formation of situational panic psychological perception (SPPP) (β = 0.828, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H7.

Emergency-response training (FEMS2) was the most important component of the fire emergency management system (FEMS) (β = 0.927, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H8.

Diversification of escape Channel design (BSPP6) made a very significant contribution to building-safety performance planning (BSPP) (β = 0.861, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H9.

Based on the standardized path coefficients, the impact strengths of the three exogenous latent variables on escape response behavior (ERB) were, in descending order of absolute value: fire emergency management system (FEMS) (β = 0.274) > situational panic psychological perception (SPPP) (β = −0.199) > building-safety performance planning (BSPP) (β = 0.164).

Firstly, the fire emergency management system (FEMS) showed the strongest positive predictive power. Among them, the loading of emergency-response training (FEMS2) was extremely high (β = 0.927), indicating that strengthening emergency plan drills and training is the most critical practical measure to enhance the effectiveness of this system and thereby optimize evacuation behavior (ERB).

Secondly, the significant negative impact of situational panic psychological perception (SPPP) highlighted the core role of psychological factors in emergency evacuation. Cognitive bias (SPPP7), as its main cause (β = 0.828), indicated that irrational decision-making and misunderstandings in fires would significantly exacerbate panic, thereby hindering the generation of effective evacuation behavior (ERB).

Meanwhile, although the impact of building-safety performance planning (BSPP) was relatively weak, it was still important. The prominent contribution of diversified escape Channel design (BSPP6) (β = 0.861) showed that providing multiple clear escape routes in the building design stage is a key strategy to enhance its safety performance and thereby have a positive impact on evacuation behavior (ERB).

Finally, within the internal mechanism of escape response behavior (ERB), wayfinding decision-making behavior (ERB1) (β = 0.852) had slightly higher explanatory power than group collaborative behavior (ERB6) (β = 0.816), indicating that in emergency situations, whether individuals can make rapid and accurate path selection decisions is a more core element in determining escape efficiency.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Conclusions

This study systematically constructed and validated a measurement model for personnel escape efficiency in high-rise building fire situations based on stress-cognition theory, environment–behavior relationship theory, and risk management theory. The four core constructs are defined as follows: (1) Fire Emergency Management System (FEMS) refers to the institutional framework encompassing emergency plans, training mechanisms, and resource coordination for risk response; (2) Building-Safety Performance Planning (BSPP) denotes the architectural design features, including spatial layout, exit accessibility, and material properties, that ensure safety during evacuations; (3) Situational Panic Psychological Perception (SPPP) represents the individual’s psychological stress responses, such as panic, anxiety, and cognitive biases, triggered by fire emergencies; (4) Escape Response Behavior (ERB) reflects the combined outcomes of psychological, environmental, and management factors on actual evacuation actions. The research conclusions are mainly reflected in the following aspects.

Firstly, regarding the verification of direct path hypotheses. The SEM results showed that the fire emergency management system (FEMS) could significantly promote escape response behavior (ERB), which means that in high-rise fire situations, a sound emergency system, standardized training mechanisms, and effective resource scheduling are the core guarantees for improving individual and group escape efficiency. Building-safety performance planning (BSPP) also had a positive impact on escape response behavior (ERB), indicating that scientific and rational spatial layout, accessibility of safety exits, and fire resistance of materials all contribute to orderly crowd evacuation. In contrast, situational panic psychological perception (SPPP) showed a negative effect, indicating that in high-pressure fire environments, panic, anxiety, and cognitive biases severely interfere with escape decision-making and behavior, thereby weakening overall evacuation efficiency. These results collectively confirmed Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3.

Secondly, regarding the test of comparative paths. The analysis results showed that the positive impact of the fire emergency management system (FEMS) on escape response behavior (ERB) was significantly stronger than that of building-safety performance planning (BSPP), supporting Hypothesis H4. This finding suggests that in the face of sudden fire events, even if the building design has reasonable safety performance, it is still necessary to compensate for environmental shortcomings through sound emergency management and institutional guarantees. The effectiveness of emergency management often plays a more decisive role at critical moments.

Thirdly, regarding the revelation of formative paths. This study further analyzed the key drivers within each core construct. Group collaborative behavior (ERB6) and wayfinding decision-making behavior (ERB1) were both proven to be important components of escape response behavior (ERB), supporting Hypotheses H5 and H6. This indicates that in the evacuation process, it is necessary for individuals to have the ability to make rapid independent judgments, and group collaboration also brings organization and mutual assistance. Situational panic psychological perception (SPPP) is mainly formed by cognitive bias (SPPP7), supporting Hypothesis H7, which reveals that psychological bias is the main cause of individual panic emotions. The effectiveness of the fire emergency management system (FEMS) depends on emergency-response training (FEMS2), supporting Hypothesis H8, which indicates that training is an important mechanism for converting institutional advantages into actual escape efficacy. The essence of building-safety performance planning (BSPP) is mainly reflected in the diversified design of escape channels (BSPP6), supporting Hypothesis H9, which shows that multi-channel, highly visible building design can provide higher safety assurance for personnel in chaotic environments.

In summary, all hypotheses of this study were supported by empirical evidence. FEMS, BSPP, and SPPP, as exogenous latent variables, jointly act on ERB, forming a complete causal chain. This analytical framework not only deepens the understanding of fire-escape mechanisms at the theoretical level but also provides operational references for fire management and building design at the practical level. The scientific nature of this study is reflected in its solid theoretical foundation, rigorous mixed research methods, and empirical testing process based on real fire experience data, providing reliable theoretical and empirical support for high-rise building fire evacuation research.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study developed and optimized a set of scales applicable to high-rise fire-escape situations through the path of “systematic literature review—Delphi method—quantitative empirical testing”. First, by systematically reviewing high-level empirical literature in the past five years, 40 potential influencing factors were initially screened. Then, experts in the fields of fire rescue and design management were invited to conduct three rounds of Delphi consultations to ensure the theoretical fit and content validity of the items. Subsequently, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to extract the latent factor structure, and the reliability and validity of the scale were strictly tested in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), finally confirming the measurement model of the scale. Finally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to construct and validate the path relationships among latent variables. The entire process not only ensured the scientific and systematic nature of the measurement tools but also provided a replicable research paradigm for subsequent related studies. Therefore, an important contribution of this study is the development of a reliable, effective, theoretically based, and empirically supported questionnaire tool, which lays a solid foundation for the measurement and intervention research of fire-escape efficiency.

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the valuable conclusions obtained in this study, there are still some limitations that need to be further improved in future research.

Firstly, the sample of this study mainly came from high-rise residential residents and groups with fire experience in the Chaoyang District, Beijing. It is worth noting that 58.9% of the respondents in this study are engaged in fire management-related work, which indicates a potential response bias in this sample structure. The professional training and work experience of this group have shaped their cognitive framework for fire emergencies. Compared with the general public without professional backgrounds, they have a more systematic understanding of evacuation norms, higher risk perception sensitivity, and more standardized behavioral tendencies. This makes the FEMS and BSPP evaluations more “standardized” rather than reflecting the true views of ordinary residents. Although this deviation may enhance the effectiveness of management systems and architectural designs in actual evacuation scenarios, it limits the promotion of research results to a wider public. After all, the responses of professional groups in fire emergencies differ from the actual psychological and behavioral characteristics of ordinary high-rise residents. Therefore, future research should balance the proportion of professional and non-professional samples to verify the applicability of the model in different populations. Although the sample covered different ages, occupations, and educational backgrounds, the geographical limitation may affect the universality of the conclusions. Future research can conduct large-scale surveys in different regions or even cross-national contexts to test the applicability and stability of the model in diverse situations.

Secondly, the sample mainly consisted of high-rise residential residents and individuals with fire experience in the Chaoyang District, Beijing. However, the data collection did not differentiate between living floors. Existing research has shown that floor height significantly impacts evacuation behavior. Residents on lower floors are more likely to escape directly through external windows or staircases, while those on higher floors are more reliant on internal evacuation systems and fire rescue guidance. They are also more prone to anxiety due to longer evacuation distances. This data collection deficiency in this study prevented the exploration of the heterogeneity in evacuation behavior mechanisms among residents on different floors, simplifying the understanding of the ERB mechanism. This gap may limit the precise application of the conclusions in high-rise building evacuation management. Additionally, the study did not explicitly focus on special groups such as people with disabilities, the elderly (≥65 years), and children (<12 years) as separate research subjects or control variables. These groups have unique evacuation needs. People with disabilities may depend on accessible facilities and assistance behaviors; the elderly have limited mobility and slower decision-making speeds; children are prone to subsequent behaviors and lack risk judgment capabilities. The lack of sample coverage and failure to capture the behavioral characteristics of these special groups result in insufficient comprehensiveness of the model. Future research should focus on special populations and floor differences, design targeted questionnaires, or use VR simulation technology to collect data on people with disabilities, the elderly, and children. It is essential to explore the moderating effects of age, physical condition, and floor height on the relationships between FEMS/BSPP/SPPP and ERB. Formulating differentiated evacuation strategy models, such as dedicated escape channels for lower-floor residents and emergency refuge layers for higher-floor residents, and incorporating special group rescue mechanisms into FEMS are necessary steps.

Thirdly, this study used a self-report questionnaire method. Although efforts were made to enhance the authenticity of the data through situational simulation videos and questionnaire design, there may still be social desirability effects, recall biases, and other issues. This means that respondents may be influenced by subjective impressions or emotions when describing their fire experiences and escape behaviors. Future research can combine experimental methods, virtual reality (VR) simulations, or field exercise observation data to enhance the objectivity and external validity of the research results.

Fourthly, although the research model covered management, environment, and psychology, it still failed to include all potential variables. For example, individual health conditions, physical function differences, cultural factors, and social capital may also affect escape efficiency. In addition, the model did not conduct an in-depth analysis of possible mediating and moderating effects among variables. For example, does FEMS indirectly reduce the negative impact of SPPP on ERB by enhancing psychological security, and does BSPP partially mediate the relationship between FEMS and ERB by enhancing individual spatial cognition? These potential mechanisms need to be further explored in subsequent research.

Fifthly, this study mainly used cross-sectional data for analysis, which can only reveal the correlational relationships and hypothetical causal paths among variables, but is not sufficient to fully prove causal relationships. Future research can combine longitudinal data or experimental designs to explore the evolutionary mechanisms of fire-escape behavior from a dynamic perspective over time, thereby more accurately revealing causal chains.

Finally, at the practical level, although the questionnaire and model of this study provide beneficial references for fire management and building design, how to transform them into specific policy measures and engineering standards still requires further interdisciplinary cooperation. Future research can incorporate detailed case studies of actual high-rise building fires or evacuation drills to further verify the reliability and universality of the proposed model and measurement tools. For example, how to incorporate the training requirements of FEMS into daily community governance, how to include the diversified escape channel design of BSPP into building regulations, and how to reduce the negative impact of SPPP through psychological interventions are all issues that need continuous exploration between academia and practice departments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G. and D.L.; methodology, K.G. and D.L.; software, K.G. and D.L.; validation, K.G. and D.L.; formal analysis, K.G.; investigation, K.G.; resources, K.G.; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.G.; writing—review and editing, D.L. and X.Z.; visualization, K.G.; supervision, D.L. and Y.J.; project administration, D.L. and Y.J.; funding acquisition, K.G. and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the anonymous and non-invasive nature of the data collection (i.e., anonymous questionnaires). The study involved anonymous questionnaires administered to participants who had experienced fires. No personal identifiers, detailed case histories, or images were collected, ensuring participant confidentiality. Signed informed consent forms were obtained from all participants and are securely stored at Hanyang University, Department of Industrial Design to protect participant privacy, in accordance with ethical guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants and is included in the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Fire and Rescue Division of Chaoyang District, Beijing, for their invaluable administrative support and assistance in facilitating the distribution and collection of questionnaires for this study. Their cooperation was essential to the acquisition of the empirical data. This study sincerely thanks all the experts who participated in the Delphi consultation for their valuable time and professional insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FEMS | Fire Emergency Management System |

| BSPP | Building-Safety Performance Planning |

| SPPP | Situational Panic Psychological Perception |

| ERB | Escape Response Behavior |

| FEMS1 | Information management |

| FEMS2 | Emergency-response training |

| FEMS3 | Psychological counseling services |

| FEMS4 | Accessibility of barrier-free facilities |

| FEMS5 | Sensitivity of alarms |

| FEMS6 | Effectiveness of emergency signs |

| FEMS7 | Path planning and training |

| FEMS8 | Regular fire assessment |

| FEMS9 | Accessibility of fire services |

| FEMS10 | Risk perception training |

| FEMS11 | Availability of sanitary facilities |

| FEMS12 | Education on fire smoke toxicity |

| BSPP1 | Scientific nature of structural design |

| BSPP2 | Accessibility and visibility of escape exits |

| BSPP3 | Escape path in spatial layout and zoning planning |

| BSPP4 | Fire resistance of materials |

| BSPP5 | Durability of materials |

| BSPP6 | Diversification of escape Channel design |

| BSPP7 | Spatial perception of door width |

| BSPP8 | Thermal conductivity of staircase materials |

| BSPP9 | Heat load perception |

| BSPP10 | Spatial constraint perception |

| SPPP1 | Panic emotions in fires |

| SPPP2 | Rebellious behavior perception |

| SPPP3 | Social vulnerability perception |

| SPPP4 | Limited rationality perception |

| SPPP5 | Environmental disorder perception |

| SPPP6 | Herd behavior |

| SPPP7 | Cognitive bias |

| SPPP8 | Escape decision-making behavior |

| SPPP9 | Human flow density perception |

| ERB1 | Wayfinding decision-making behavior |

| ERB2 | Phototaxis |

| ERB3 | Leadership perception |

| ERB4 | Response to stimuli |

| ERB5 | Physiological response perception |

| ERB6 | Group collaborative behavior |

| ERB7 | Tendency perception |

| ERB8 | Order perception |

| ERB9 | Fire material perception |

Appendix A

| QUESTIONNAIRE Study: Fire Safety and Evacuation Efficiency in High-Rise Buildings | ||||||||

| Dear Sir/Madam: You are cordially invited to participate in our research survey entitled: FIRE SAFETY AND EVACUATION EFFICIENCY IN HIGH-RISE BUILDINGS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY This research is jointly conducted by researchers from Hanyang University, Hebei Oriental University, and Beijing Chaoyang District Fire Rescue Detachment. The questionnaire is administered and distributed by the Beijing Chaoyang District Fire Rescue Detachment to individuals who have experienced fire incidents. Participant Profile: Adults who have experienced fire incidents. Participation in this study is completely voluntary. You may withdraw at any time without any negative consequences to your relationship with the researchers or affiliated institutions. The questionnaire will take approximately 5–7 min to complete. The data collected will be used solely for academic research purposes, including publication in international journals and potential applications for enhancing fire safety management strategies. Your contribution is highly valuable to this important study. Research Team:

Duanduan Liu—PhD Student, Department of Industrial Design, ERICA Campus, Hanyang University, Ansan 15588, Korea Email: liuduanduan5@hanyang.ac.kr ORCID/Lattes: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-1753-2105 Contact for Questionnaire Distribution: Beijing Chaoyang District Fire Rescue Detachment Thank you for your time and support. | ||||||||

| Part One: SQ Questions—Survey Items for Sample Characteristics | ||||||||

| 1. Gender: | ||||||||

Male Male |  Female Female | |||||||

| 2. Age: ______ years old | ||||||||

| 3. What is your highest level of education? | ||||||||

High School High School |  University University |  Master’s Degree Master’s Degree |  Ph.D. Ph.D. | others (Please specify: ______) | ||||

| 4. Your occupational category is: | ||||||||

Related to fire management Related to fire management |  Unrelated to fire management Unrelated to fire management | |||||||

| 5. Have you ever personally experienced a fire incident? (Screening question) | ||||||||

Yes Yes |  No No | |||||||

| 6. [If Question 5 is “Yes”] How would you describe the severity of the fire incident you experienced? | ||||||||

Mild Mild |  Moderate Moderate |  Severe Severe | ||||||

| 7. Following the fire incident, did you receive psychological or medical help because of the event? | ||||||||

Yes Yes |  No No | |||||||

| Part Two: Core Research Questions | ||||||||

| Instructions: This section aims to understand your views on the relevant factors in high-rise building fires. Please base your answers on professional knowledge, training experience, or personal experience, and after watching a 3–5-min fire simulation video, assess the impact of the following items on safe evacuation efficiency. The rating scale ranges from (1) “strongly disagree/significantly hinders fire evacuation efficiency” to (9) “strongly agree/significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency.” Please select the number that best reflects your opinion. Please note that all questions must be answered, and only one option can be chosen for each question. | ||||||||

| FEMS1: How does information management (such as fire data recording, real-time monitoring systems, etc.) impact fire evacuation efficiency? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS2: How does regular emergency-response training (such as fire extinguisher use, evacuation drills) impact evacuation efficiency? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS3: How does the provision of post-disaster psychological counseling services impact the recovery of affected individuals and their subsequent evacuation behavior? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS4: How does the completeness of barrier-free facilities (such as ramps, tactile paving, dedicated passages) impact evacuation efficiency? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS5: How does the sensitivity and reliability of fire alarms impact early warning and the initiation of evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS6: How does the recognizability of emergency signage (such as exit indicators, directional guidance) in a smoke-filled environment impact evacuation path selection? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS7: How does path planning and training (preset escape routes in case of fire) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS8: How does path planning and training (preset escape routes in case of fire) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS9: How does the availability and accessibility of fire services impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS10: How does the cultivation of situational risk perception impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS11: How does the availability and accessibility of sanitary infrastructure impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| FEMS12: How much effect will the popularization of smoke knowledge of chemicals produced by combustion play in safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP1: How does the scientific nature of building structural characteristics impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP2: How does the visibility and accessibility of escape exits impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP3: How does the escape path in spatial layout and zoning planning impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP4: How does the fire resistance of building materials impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP5: How does the durability and sustainability of building materials impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP6: How does the diversified design of escape channels impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP7: How does the perception of door width impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP8: How does the thermal conductivity of staircase materials impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP9: How does heat load perception impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| BSPP10: How does spatial congestion (disorderly placement of objects) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP1: How do panic emotions (panic emotions generated in fires) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP2: How does rebellious behavior perception (rebellious behavior caused by panic emotions) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP3: How does social vulnerability perception (the impact of economic and educational levels on escape behavior) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP4: How does limited rationality perception (difficulty in maintaining fully rational decision-making in emergencies) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP5: How does order perception (evacuation management and guidance) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP6: How does herd behavior (following others in emergencies) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP7: How does cognitive bias (cognitive bias that may occur in emergencies) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP8: How does escape decision-making behavior made due to fear, anxiety, and other psychological pressures impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| SPPP9: How does human flow density perception and crowd movement speed impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB1: How does wayfinding decision-making behavior (following escape signage or pre-planned escape routes to leave the danger zone) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB2: How does phototaxis (attraction and tendency towards light or illumination during a fire) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB3: How does leadership perception (the influence of leaders during evacuation) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB4: How does response to stimuli (the time it takes for an individual to perceive and react to external stimuli or emergencies, which may be influenced by various factors) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB5: How does physiological response perception (automatic physiological responses of the body under fire threat) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB6: How does group collaborative behavior (the decisions and actions of companions) impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB7: How does the tendency during escape impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB8: How does orderly evacuation guidance impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| ERB9: How does material perception impact safe evacuation? | ||||||||

| Significantly impedes fire evacuation efficiency | Neutral | Significantly improves fire evacuation efficiency | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

Appendix B. Implementation Details of the Delphi Expert Consultation Method

Appendix B.1. Expert Panel Composition

The Delphi method employed in this study involved an expert panel composed of 11 senior experts from the fields of fire emergency response and industrial design theory. This ensured that the consultation results would be both practical and forward-looking. The selection of experts followed the principles of authority, representativeness, and interdisciplinary diversity. The composition of the panel was as follows:

- Fire Emergency Response Group (5 experts): All members were from the Chaoyang District Fire Rescue Brigade in Beijing, with an average professional experience of over 15 years. Their titles/positions included senior engineers, heads of fire investigation technology departments, and frontline commanders, all possessing extensive experience in fire rescue command, risk assessment, and emergency plans formulation.

- Industrial Design and Theory Group (6 experts): Members were from industrial design departments of domestic universities, including five professors and one associate professor. Their research areas covered safety design, human factors engineering, user experience, and evacuation behavior simulation, with an average research experience of over 10 years.

All experts provided informed consent and participated fully in the study.

Appendix B.2. Consultation Process

This study strictly adhered to the classic Delphi principles of anonymity, multiple rounds, feedback, and convergence. The process consisted of three rounds of consultation, as illustrated in the figure below.

Figure A1.

Delphi Expert Consultation Process Flowchart.

Figure A1.

Delphi Expert Consultation Process Flowchart.

Round 1 Consultation (Open-Ended Questionnaire):

- Format: Experts were provided with a preliminary list of 40 potential influencing factors extracted from the literature review, along with brief definitions of the four core theoretical domains (FEMS, BSPP, SPPP, ERB).

- Task: Experts were asked to evaluate the completeness of the list based on their professional knowledge and experience, freely adding, deleting, or modifying any items, and suggesting which theoretical domain each item belonged to.

- Outcome: A total of 12 new item suggestions, 23 modification suggestions, and 18 classification suggestions were collected. The research team integrated the feedback, clarified ambiguously worded items, merged duplicates, and added five items of significant practical importance (e.g., “Accessibility of sanitary facilities—FEMS11”, “Education on fire smoke toxicity—FEMS12”), resulting in a second-round questionnaire with 42 items.

Round 2 Consultation (Structured Scoring):

- Format: Experts were provided with a structured questionnaire containing 42 items, using a Likert 5-point importance scale (1 = very unimportant, 5 = very important) and a familiarity scale (1 = unfamiliar, 5 = very familiar).

- Task: Experts were asked to rate the importance of each item and reconfirm the theoretical domain affiliation of each item.

- Analysis: After collecting the questionnaires, the mean importance score, full-mark frequency, and coefficient of variation (CV) were calculated for each item. Based on qualitative feedback from experts, further screening was conducted. The screening criteria were a mean importance score > 3.5 and a CV < 0.25. After this round, three items were deleted due to low importance scores and high controversy (high CV).

Round 3 Consultation (Final Consensus):

- Format: Experts were provided with the statistical analysis results from the second round (including mean scores, CV, and reasons for modifications/deletions) along with the revised questionnaire containing 39 items.

- Task: Experts were asked to provide final ratings and confirmations based on the aggregated feedback from the group.

- Outcome: After this round, all 39 items had a mean importance score above 4.0 and a CV below 0.2, indicating a high level of consensus among experts. The research team and expert panel conducted a final review, fine-tuned the wording of some items, and ultimately finalized the formal scale containing 40 measurement items (see Table 1).

Appendix B.3. Expert Authority and Consensus Level

- Expert Authority Coefficient (Cr): Determined by two factors: the experts’ judgment basis (Ca) and familiarity (Cs). The calculated expert authority coefficient was Cr = (Ca + Cs)/2 = 0.87, which is greater than 0.7, indicating a high level of expert authority and reliable consultation results.