Abstract

The integration of renewable energy sources has become a strategic necessity for sustainable energy management and supply security. This study evaluates the performance of eight metaheuristic optimization algorithms in scheduling a renewable-based smart grid system that integrates solar, wind, and battery storage for a factory in İzmir, Türkiye. The algorithms considered include classical approaches—Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), Krill Herd Optimization (KOA), and the Ivy Algorithm (IVY)—alongside hybrid methods, namely KOA–WOA, WOA–PSO, and Gradient-Assisted PSO (GD-PSO). The optimization objectives were minimizing operational energy cost, maximizing renewable utilization, and reducing dependence on grid power, evaluated over a 7-day dataset in MATLAB. The results showed that hybrid algorithms, particularly GD-PSO and WOA–PSO, consistently achieved the lowest average costs with strong stability, while classical methods such as ACO and IVY exhibited higher costs and variability. Statistical analyses confirmed the robustness of these findings, highlighting the effectiveness of hybridization in improving smart grid energy optimization.

1. Introduction

Integrating distributed generation (DG) units into smart grids necessitates advanced optimization techniques to ensure efficient energy production and consumption management. Metaheuristic algorithms have gained prominence due to their effectiveness in addressing complex, nonlinear optimization problems [1], particularly under the uncertainties inherent in renewable energy generation profiles, where conventional deterministic methods often fall short [2].

Prior research has applied metaheuristic approaches to multi-objective problems in smart grids, including production planning, load balancing, demand-side management, and cost minimization [3,4,5]. For instance, Ref. [3] reported an 11% reduction in production costs, while [4] demonstrated improved load balancing accuracy. Farhangi [6] highlighted the challenges faced by smart grid management systems under structural transformations that significantly increase data volumes, whereas Singh [7] analyzed the effectiveness of GA and PSO in enhancing DG system efficiency. Similarly, Ref. [8] reported up to a 20% reduction in energy losses using PSO for DG placement optimization. Recent studies have also emphasized the importance of hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES) for off-grid electrification challenges, especially in developing regions. For example, Khan et al. [9] conducted a comprehensive techno-economic feasibility analysis of an autonomous hydrogen-based HRES combining photovoltaic panels, fuel cells, and biogas generators to address severe power shortages in Pakistan, demonstrating system viability with optimized cost of energy and reliability.

Recent studies have shown that advanced and hybrid metaheuristic structures can further improve system performance [10,11]. Zhang et al. [12] achieved a 20% reduction in energy costs and an 18% increase in renewable energy penetration in microgrid management using a hybrid GWO algorithm. Additionally, research on DG systems integrated with battery storage has shown that optimization algorithms directly influence energy storage strategies, with [13] reporting a 25% increase in battery charge–discharge cycles and a 20% improvement in grid feedback efficiency.

Diab et al. [14] demonstrated that algorithm selection impacts system efficiency by 5–15% in energy management applications. Furthermore, recent studies indicate that AI-supported and adaptive metaheuristic algorithms yield better performance under dynamic network conditions, reducing response times to sudden load changes by 20–35% and decreasing energy losses by 10–25% [15,16,17,18]. In line with these findings, Al-Maqaleh et al. [19] highlighted that hybrid swarm intelligence models significantly enhance energy cost minimization and reliability in renewable-based microgrids. Similarly, Akopov [20] demonstrated that matrix-based hybrid genetic algorithms outperform conventional evolutionary and swarm methods in terms of accuracy and convergence speed when applied to complex optimization environments. The use of the KOA algorithm led to notable efficiency gains by simultaneously reducing fuel cost, power losses, and emissions, while maintaining acceptable voltage stability—demonstrating its effectiveness in complex power system optimization tasks [21]. The Ivy algorithm (IVYA) is a bio-inspired optimization method that mimics the coordinated growth and adaptive behavior of Ivy plants to preserve population diversity and effectively solve complex engineering problems [22]. Table 1 summarizes up-to-date literature on metaheuristic algorithm-based optimization in smart grids.

Table 1.

Metaheuristic algorithm-based optimization results from the literature.

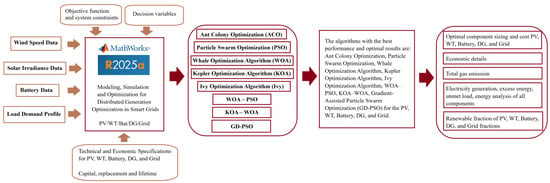

This study, as seen in Figure 1, examines the performance of five different metaheuristic optimization methods and three hybrid metaheuristic algorithms within a systematic and comparative analysis framework to optimize the energy management processes of DG systems integrated into smart grids. The study looked at how well eight optimization algorithms work for managing energy in smart grids, focusing on goals like lowering costs, using more renewable energy, and improving battery efficiency, while considering the complex nature of production planning. In this study, we propose an objective function designed to enhance the accuracy and realism of the optimization model. This is achieved by incorporating a penalty term that addresses deviations in the battery’s State of Charge (SOC) at the conclusion of the 24 h planning period. Then, we analyzed the aforementioned algorithms’ performance differences against deterministic and stochastic inputs in detail; we conducted a multi-criteria evaluation based on criteria such as solution quality, convergence speed, computational cost, and algorithmic stability. Additionally, the findings aim to provide decision-makers with a scientific reference framework for algorithm selection in designing and operating smart grid infrastructures. In this regard, the investigation, one of the rare studies, further illuminates interdisciplinary applications in renewable energy integration, battery management, and grid economics.

Figure 1.

General block diagram of the optimization methodologies used in the study.

2. Problem Definition

2.1. System Components

Today’s transformation in energy systems is replacing the centralized structure with a more flexible, environmentally friendly, and efficient structure known as DG systems. Integrating renewable sources such as solar and wind into the grid brings with it a multi-criteria and dynamic optimization problem that involves uncertainties in production forecasts and the management of energy storage units. In this context, energy management, production planning, battery charge–discharge strategies, and minimizing economic costs in a grid-connected system within an innovative grid environment require a holistic approach.

This study addresses the problem of minimizing the total operational cost of a hybrid energy system over a 24 h horizon, extended here to a 7-day dataset (168 h) to capture temporal variability. The system consists of solar and wind energy generation, a battery energy storage system (BESS), grid connection, and time-varying energy demand. The optimization model considers three primary decision variables: hourly grid energy procurement, battery charging, and battery discharging. These variables are subject to constraints including battery capacity limits, energy balance requirements, renewable energy allocation, and dynamic grid pricing.

Within the battery capacity constraint, the state of charge (SOC) is limited between 0 and 500 kWh. This constraint determines the battery’s full discharge and full charge limits, ensuring both the preservation of the battery’s chemical and mechanical structure and the realism and feasibility of energy management strategies. In the mathematical model, SOC is updated based on the net effect of charging and discharging processes at hourly time steps and is always kept within the specified limits. This constraint prevents energy optimization algorithms from exceeding battery capacity, thereby contributing to grid stability and the continuity of energy flow. Thus, the system minimizes the risks of overloading and discharging while ensuring the efficient use of the battery’s energy storage capacity.

On the other hand, the energy balance constraint requires that the supply-demand balance be maintained in real-time for each hour to ensure a healthy and continuous flow of energy in an innovative grid environment. In this context, the energy balancing constraint defined in the system indicates that at each time step (with hourly resolution), the total energy supply must be at a level that meets the total energy demand and battery charging requirements for the same time. In mathematical terms, this constraint is expressed in Equation (1), which holds for each hour t ∈ {1, 2, …, 24}:

The symbols used in this study are defined as follows:

- G(t): Energy drawn from the grid at time t (kWh);

- S(t): Energy produced from solar at time t (kWh);

- W(t): Wind energy production at time t (kWh);

- D(t): Battery discharge amount at time t (kWh);

- L(t): Load demand at time t (kWh);

- C(t): Battery charging requirement at time t (kWh).

This constraint ensures that the system maintains sufficient energy supply on an hourly basis. In instances where this adequacy is not achieved, the resulting energy imbalance is systematically penalized within the objective function, thereby encouraging solutions that satisfy operational feasibility while minimizing costs. Furthermore, this balancing is not solely dependent on production and demand, but also on the dynamic behaviors of temporary storage elements like batteries. This reduces unnecessary energy extraction from the grid and encourages the more efficient use of renewable energy sources. Additionally, suppose the balancing rules are not followed. In that case, any energy shortage or excess is assessed using a penalty function that impacts the system’s financial performance, making sure the algorithm focuses on finding solutions that keep energy balanced. This situation both supports grid stability and increases the impact of battery management on the system.

In this study, we modeled the production of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind energy, using hourly data because they can vary significantly over time. Solar energy is produced only from 07:00 to 18:00, reaching a peak of 380 kWh during this period, following a wave-like pattern. Wind energy, however, can be generated at any time of the day and varies randomly between 0 and 140 kWh each hour. The production profiles of both energy sources were created at the beginning of the optimization algorithm, defined as a fixed dataset, and evaluated independently of the algorithm’s decision variables. The solar irradiance and wind data used in the simulation were determined based on measurements from İzmir province [23,24]. This approach ensures that the photovoltaic production scenarios reflect local climatic conditions, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the energy management model.

Grid electricity prices exhibit hourly variations, which constitute a critical parameter within the total cost function. This temporal variability significantly influences the economic efficiency of energy consumption scheduling, a process essential for determining optimal energy procurement strategies in the context of energy system optimization. Consequently, energy management algorithms are designed to coordinate energy demand and battery operation in a manner that minimizes operational costs while incorporating these price fluctuations. In the present simulation, actual electricity price data covering the period of 19–25 May 2025 were employed. These data correspond to the industrial (low-voltage, free consumer) subscriber group, with unit prices ranging between 2.02 and 6.53 TL/kWh [25,26]. These values were utilized as the weekly minimum and maximum thresholds, ensuring that the hourly price inputs reflect actual market dynamics. This methodology provides a more reliable and realistic assessment of the performance and effectiveness of the employed optimization algorithms.

The objective of the problem is to minimize the total cost by using the grid and renewable resources in a balanced manner, along with the battery system under variable energy prices. The cost function consists of the total amount obtained by multiplying the energy drawn from the grid by the hourly prices and the penalty term resulting from energy imbalances. In this context, the proposed structure aims not only at economic optimization but also at reducing the load on the grid and increasing the share of renewable energy usage. This complex and multi-dimensional optimization problem is challenging to solve with traditional deterministic methods, so utilizing the effectiveness of metaheuristic and hybrid metaheuristic algorithms has been deemed appropriate. In this case study, a comparative analysis was conducted on several modern optimization algorithms, including ACO, PSO, WOA, WOA-PSO, KOA, KOA-WOA, IVY, and GD-PSO. The performance of each algorithm was rigorously evaluated concerning its efficacy in energy management.

2.2. Energy Optimization Flow Diagram

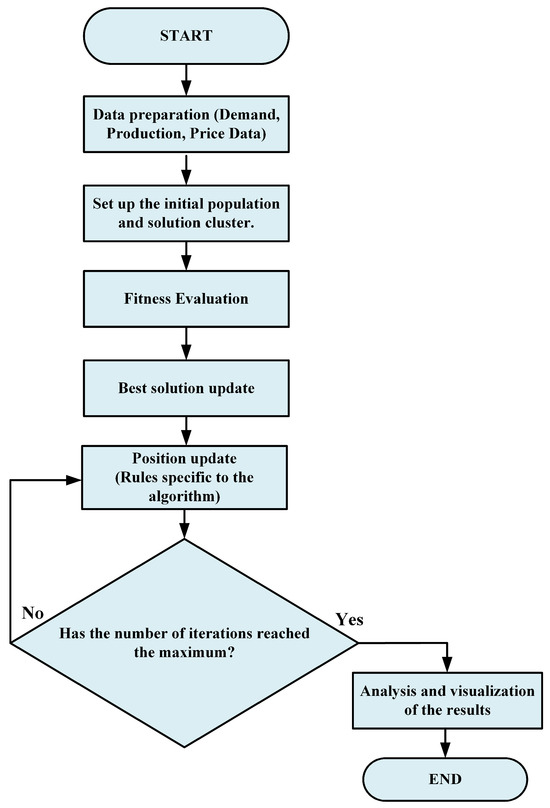

In this simulation study, we utilized traditional metaheuristic algorithms and hybrid metaheuristic algorithms derived from them to optimize the energy management system that integrates renewable energy sources, including solar and wind, along with battery systems. The optimization process aims to minimize the total energy cost based on time series data of demand, renewable energy production, and grid prices. Each of the employed algorithms determines the hourly values of energy supply and consumption parameters, including grid energy procurement, battery charging, and battery discharging, over a seven-day period. A flowchart illustrating the energy optimization process is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of energy optimization.

According to this flowchart, during the data preparation phase, an important step in the optimization process, basic input information like energy demand, solar and wind energy production patterns, and grid energy prices are gathered or created from relevant data sources every hour. These data guarantee the model’s realistic design and suitability for dynamic working conditions. During the initial step of creating the population and solution set, the starting points for the search agents, or potential solutions, are randomly selected within specified limits according to the chosen optimization algorithm. This initial population provides diversity for the algorithm to explore the vast search space effectively. At the end of this process, a fitness evaluation is conducted. In each iteration, the suitability of the current solution candidates is evaluated within the framework of the specified cost function. The aforementioned cost function is based on the total energy cost resulting from multiplying the amount of energy purchased from the grid by its price; in addition, it includes penalty terms to ensure compliance with energy balance constraints and battery SOC limits. In this way, cost minimization is ensured, and the system’s technical constraints are prioritized. As a result of the fitness evaluation, the solution candidates with the lowest cost value are identified as the best positions (lowest cost), and these positions are optimized throughout the progress of the algorithm. The search agents change their positions based on the algorithm’s particular math and statistical criteria. This change helps improve the optimal solution by moving it closer to local and global optima. The iteration process continues until the predetermined maximum number of iterations is reached. The algorithm tries to find better points in the search space during this process by updating the best solution at each step. Thus, the algorithm continuously updates its position.

At the end of the iteration and status check phase, the steps are repeated if the maximum number of iterations has not been reached. When the maximum number of iterations is reached or sufficient convergence is achieved, the best-found solution is considered the final output. Detailed analyses are conducted using the obtained optimal solution in the final stage of the algorithm, which is the result analysis and visualization phase. The study includes energy distribution, renewable production, grid usage balance, battery SOC, and total cost. Graphs are created to visualize these analyses; thus, system performance and optimization success are evaluated quantitatively and visually. This integrated approach contributes to decision support processes aimed at enhancing the effectiveness of the energy management system.

2.3. Decision Variables

The primary objective of this study is to optimize an energy management framework supported by renewable energy sources and integrated with a battery storage system. The system is designed to meet electricity demand over a seven-day period while incorporating solar and wind energy generation, battery charge–discharge operations, and grid energy procurement. The decision variables for the optimization problem include grid energy usage, battery charging energy, and battery discharging energy. Specifically, grid energy usage is represented by 168 continuous decision variables, each indicating the amount of energy procured from the grid during each hourly interval, constrained within the range of [0, 1000] kWh. Battery charging energy is modeled using 168 continuous decision variables that specify the hourly charging quantity, bounded between [0, 500] kWh. Similarly, battery discharging energy is characterized by 168 continuous decision variables representing the hourly discharge quantities within the range of [0, 500] kWh. This formulation results in a total of 504 decision variables, with the objective of minimizing total energy costs while optimizing battery utilization and renewable energy production. Each decision variable is subjected to a set of technical and economic constraints to ensure energy balance and to enforce adherence to the system’s physical limitations, including battery capacity and operational boundaries. Collectively, these variables define the search space within which the employed metaheuristic algorithms operate, forming the foundation of the optimization solution process.

2.4. Objective Function

The primary objective of the proposed energy management model is to minimize the total operational cost of the microgrid over a 7-day (168 h) planning horizon. The system integrates grid supply, solar and wind generation, and a battery energy storage system (charging and discharging). The objective function evaluates the total cost by considering grid energy purchases, dynamic energy prices, supply–demand imbalances, and battery state-of-charge (SOC) constraints. The objective function is mathematically represented by Equation (2).

The variables are defined as follows:

- Grid(t): Energy purchased from the grid at time t (kWh);

- Price(t): Unit price of grid electricity at time t (TL/kWh);

- Solar(t), Wind(t): Renewable generation from solar and wind at time t (kWh);

- Charge(t), Discharge(t): Battery charging and discharging amounts at time t (kWh);

- Demand(t): System energy demand at time t (kWh);

- PenaltySOC(d): Daily penalty function for the battery SOC at the end of day d;

- λ1: Weight coefficient for penalizing supply–demand imbalance (set to 10);

- λ2: Weight coefficient for penalizing end-of-day SOC violation (set to 100).

The first penalty term addresses hourly supply–demand imbalances: as the difference between total energy supply (from grid, renewables, and battery discharge) and total energy demand (including battery charging) increases, a proportional penalty is incurred. This term encourages the optimization algorithms to maintain energy balance at each time step. The second penalty term penalizes violations of the daily battery state-of-charge (SOC) bounds, which are defined within the 40–60% range of the battery capacity. Deviations from this range at the end of each day are penalized quadratically, promoting sustainable and safe battery operation over time.

The penalty coefficients are set as λ1 = 10 for the supply–demand imbalance and λ2 = 100 for the SOC constraint violation, and these values were empirically chosen to balance real-time energy balancing with long-term battery health. Specifically, λ1 penalizes hourly supply–demand imbalances, while λ2 penalizes daily SOC deviations within the 40–60% range of battery capacity. Increasing λ2 beyond 100 was observed to sometimes produce infeasible or excessively penalized solutions, disproportionately affecting the objective function and masking the actual performance of certain algorithms, particularly those with limited exploration or convergence capabilities. Therefore, λ2 = 100 was selected as a reasonable trade-off, enforcing SOC compliance while preserving fair comparability among all metaheuristic methods. This penalty-based formulation allows the algorithms to explore feasible and cost-effective scheduling solutions without explicit repair mechanisms: the supply–demand imbalance penalty discourages violations of energy equilibrium, while the SOC penalty promotes long-term battery sustainability, ensuring both economic efficiency and technical feasibility [27].

This formulation enables metaheuristic algorithms to explore feasible and cost-effective scheduling solutions without the need for a dedicated feasibility repair mechanism. The imbalance penalty discourages violations of the supply–demand equilibrium, while the SOC penalty promotes the long-term operational sustainability of the energy storage system. As a result, the optimization process ensures both economic efficiency and technical feasibility.

The proposed approach was implemented using a range of metaheuristic and hybrid metaheuristic algorithms, including ACO, PSO, WOA, WOA-PSO, KOA, KOA-WOA, IVY, and GD-PSO. These algorithms were selected to represent both classical and recently developed nature-inspired methods, as well as their hybrid extensions.

By incorporating penalty-based soft constraints rather than hard limits, the framework guides the algorithms toward technically feasible solutions while maintaining sufficient flexibility to explore the solution space. Since no explicit repair mechanism is applied, the optimization process inherently avoids infeasible solutions due to the increased cost associated with constraint violations. This structure has served as a core evaluation criterion for assessing the performance of the aforementioned algorithms in solving the smart grid scheduling problem.

Although the current objective function primarily targets the minimization of operational costs, the proposed framework can be conceptually extended to a multi-objective optimization paradigm to address additional performance criteria pertinent to contemporary microgrids. Objectives such as carbon emissions reduction, system reliability, and operational resilience could be incorporated alongside cost minimization. This integration may be realized by formulating supplementary penalty or reward terms for these objectives and combining them with the existing cost function through appropriately selected weighting factors. Multi-objective metaheuristic algorithms could then be employed to systematically explore the trade-offs among competing objectives, thereby generating a Pareto-optimal set of solutions. Such an extension would enable the framework to offer decision-makers a more comprehensive set of scheduling strategies that simultaneously account for economic efficiency, environmental impact, and operational robustness in practical smart grid applications.

2.5. Constraints

The proposed energy management model has been developed by considering various constraints related to the system’s physical capacities and the energy balance. These constraints constitute an essential component of the model to ensure the feasibility and technical validity of the solution. Equations (4)–(10) present the main constraints of the model. The model limits the maximum amount of energy drawn from the grid in each hourly period.

The maximum amounts of energy that can be charged to or discharged from the battery at the same time have also been limited.

The battery SOC is updated hourly based on the previous SOC level, along with the corresponding charge and discharge activities.

In addition, the battery’s SOC is initialized at 50% of its capacity and a daily end-of-day SOC constraint is imposed to maintain it within a target range of 40–60%, which is incorporated as a penalty term in the objective function to encourage operational consistency.

There should be no difference between the total energy supplied to the system and the total energy consumed in each hourly period. However, in this study, slight imbalances have been allowed due to practical solution pursuits, and this difference has been modeled as a penalty term in the objective function. This constraint ideally provides the following equality.

The objective function’s use of a penalty term has minimized balance violations, despite the inability to achieve this balance directly. As a result, the rules mentioned earlier, which consider the system’s technical limits, improve the reliability of the optimization process by narrowing down the possible solutions of metaheuristic algorithms to those that are valid and usable.

3. Method

This study constructed a simulation model to compare how well five popular metaheuristic algorithms and three hybrid metaheuristic algorithms combined with them worked to manage energy in a microgrid over a 7-day period. The simulation was conducted using MATLAB R2025a software. The calculations were performed on a 64-bit architecture computer with Windows 11 operating system, Intel i5-7300U 2.60 GHz processor, and 8 GB of RAM. The methodological approach consists of three main components: creating a dataset, determining parameters for five different metaheuristic optimization algorithms used, and defining performance metrics.

3.1. Setting up the Dataset

A synthetic dataset has been created for use in the optimization process. This dataset includes hourly demand, solar and wind energy production amounts, and electricity unit prices. Demand values were generated from randomly selected integers between 390 and 820 kWh for each hour. Solar energy production is active only between 07:00 and 18:00, and the production profile has been simulated with a sinusoidal-based model. Wind energy production has been simulated with randomly distributed values of 0–140 kWh for each hour. Both solar and wind profiles have been generated based on typical meteorological conditions observed in the İzmir province of Türkiye [23,24]. Electricity unit prices have been modeled to take real values for each hour within the 2.02–6.53 TL/kWh range, based on the electricity market prices observed for the industrial consumer group in Türkiye’s liberalized electricity market [25,26]. This artificial dataset has been designed to test the flexibility and resilience of algorithms against different hourly production and consumption scenarios. While synthetic data provides a controlled environment for testing, it is acknowledged that real-world renewable generation involves higher variability and uncertainty. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with this limitation in mind, and future work will focus on validating the approach with real-world datasets.

3.2. Algorithms Used in the Simulation Study

The model implemented eight distinct metaheuristic optimization algorithms, encompassing both single and hybrid approaches, each configured with default population sizes and iteration numbers, and all algorithms were executed multiple times to facilitate rigorous statistical analysis. The first of these algorithms used is the Ant Colony Optimization. ACO is a nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm that mimics the foraging behavior of ants to find optimal paths through graphs. It is particularly effective for solving complex combinatorial optimization problems by iteratively improving candidate solutions based on pheromone trails and probabilistic decision-making. In the literature, a study analyzes the optimal sizing of a hybrid energy system composed of wind, solar, and battery components for a specific load profile [28]. Due to the system’s nonlinear behavior caused by atmospheric variability and fluctuating demand, conventional optimization methods are considered insufficient. Therefore, an ACO approach is proposed to determine the optimal system sizing, and its effectiveness is validated by comparison with previous methods.

The second algorithm used in the simulation study is the PSO algorithm. PSO is an algorithm developed based on the behavior of bird flocks and fish schools. Each particle has a position and velocity in the solution space; position updates are made based on the best local (pBest) and global (gBest) solutions. This collective approach ensures convergence to the optimal solution. In a recent study, it was reported that by implementing a PSO-based energy management system in the operation of a hybrid microgrid, a 14% reduction in total energy costs was achieved with the integration of electric vehicles (EVs), and a 21% reduction without EV integration [29].

The WOA models the “bubble-net” hunting strategy of humpback whales, employing spiral convergence and linear approach mechanisms to move toward the best solution. The parameters l and p, generated stochastically, facilitate the balance between exploration and exploitation throughout the search process. In a recent application, WOA achieved a 12.4% reduction in total energy costs in an energy system incorporating renewable resources and battery storage. Furthermore, the system’s accuracy in satisfying load demand was reported to reach 98.7% [30].

The KOA is applied in managing energy systems that integrate renewable sources and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), addressing complex nonlinear optimization problems. KOA achieves significant efficiency improvements, including up to a 17.9% reduction in operational costs across various EV charging modes, demonstrating its adaptability and effectiveness in dynamic microgrid environments [31].

IVY, by emulating the growth behavior of the ivy plant, demonstrates effective performance in complex optimization problems, characterized by high convergence accuracy, reliable solution quality, and enhanced computational efficiency [32].

Furthermore, hybrid metaheuristic approaches have been increasingly applied in complex optimization problems across various engineering domains, demonstrating enhanced convergence and solution quality. For example, quantum particle swarm optimization combined with differential evolution has been successfully applied to multi-modal electromagnetic design problems, illustrating the potential of hybridization in tackling highly nonlinear, multi-peak optimization landscapes [33].

The combined use of these algorithms has led to the development of various hybrid models, such as WOA-PSO, GD-PSO and others [34,35]. These hybrid approaches leverage the complementary strengths of the individual algorithms, resulting in improved solution quality, faster convergence, and enhanced robustness across diverse optimization problems. By mitigating the limitations inherent in single algorithms, hybrid models have demonstrated superior performance in complex and large-scale scenarios, making them increasingly attractive for real-world applications in engineering, logistics, and smart grid energy management.

The hybridization mechanisms adopted in this study are designed to exploit the complementary strengths of metaheuristic algorithms by balancing global exploration and local exploitation. In the gradient-assisted PSO, a sampled numerical gradient is incorporated into the velocity update equation. This modification enables the algorithm to refine solutions around promising areas while preserving the exploratory nature of the standard PSO. The gradient term is applied with a fixed weight, resulting in a parallel mechanism where both PSO and gradient information operate simultaneously.

In contrast, the WOA–PSO hybrid follows a sequential structure. The Whale Optimization Algorithm is executed first to generate high-quality candidate solutions through global exploration. The best solution obtained from WOA is then transferred to the PSO stage, where swarm intelligence is used for local refinement. The transition between algorithms is deterministic and based on iteration completion, with the contribution of each phase implicitly controlled by the allocated iteration budget.

Similarly, the KOA–WOA hybrid employs WOA in the initial stage for diversification, followed by the Krill Herd Optimization Algorithm for exploitation. Both WOA–PSO and KOA–WOA thus adopt a two-phase framework, where exploration and exploitation are clearly separated. In all hybridizations, the transition and weighting are predetermined rather than adaptive, ensuring computational simplicity while improving solution quality compared to standalone algorithms.

For the comparative analysis, algorithmic evaluation was standardized by applying uniform parameter settings across all eight implemented metaheuristic methods, including single and hybrid approaches. The decision variables were represented as a 504-dimensional vector, structured in three consecutive 168-dimensional segments corresponding to hourly grid energy procurement, battery charging quantities, and battery discharging quantities over a 7-day horizon. The lower and upper bounds were set to 0–1000 kWh for grid procurement and 0–500 kWh for battery charging and discharging, respectively. This formulation enabled a systematic and fair comparison of the algorithms with respect to convergence behavior, solution quality, computational efficiency, and robustness under identical conditions, while also supporting sensitivity analyses across population sizes and iteration counts, as well as the assessment of convergence consistency.

3.3. Performance Parameters

The comparison of the algorithms used in the simulation study was conducted based on three basic performance criteria. The first of these is the total energy cost calculated by the objective function, based on the energy drawn from the grid and the prices. Additionally, a penalty term for supply-demand imbalances has also been reflected in this value. The second performance metric measures the proportion of energy from renewable sources like solar, wind, and battery discharge contributing to the total demand. This ratio has been used to evaluate the system’s effectiveness in terms of environmental sustainability. The final performance metric is grid usage during high-priced hours. The total amount of energy drawn from the grid during hours when electricity prices are above average has been calculated. This criterion has been used to analyze the time sensitivity of energy costs from an economic perspective. Through these criteria, each algorithm’s economic and technical performance has been comprehensively evaluated.

4. Simulation Results and Discussion

This study optimized the 7-day (168 h) energy management of a battery-supported and grid-connected energy system powered by solar and wind energy sources using eight different metaheuristic algorithms: ACO, PSO, WOA, WOA-PSO, KOA, KOA-WOA, IVY, and GD-PSO. The primary objective was to minimize the cost of energy purchased from the grid while maintaining the balance between energy supply and demand and respecting battery SOC constraints.

4.1. Sensitivity Analysis

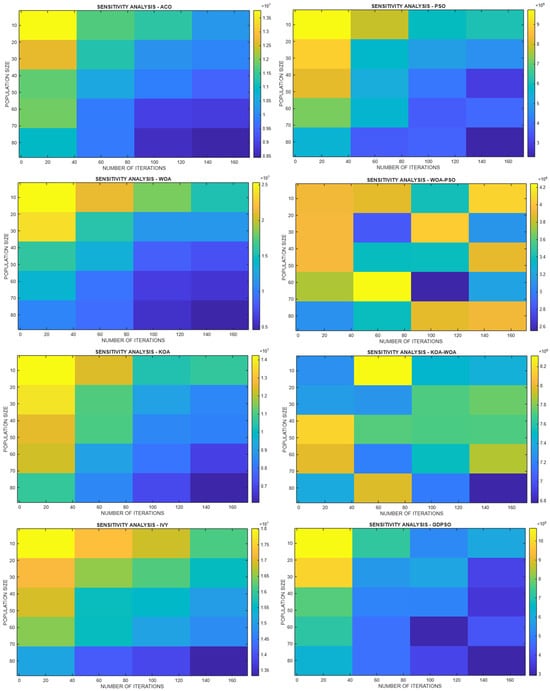

The performance of metaheuristic optimization algorithms is highly sensitive to their hyperparameters, such as population size and the number of iterations. Therefore, a comprehensive sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess how eight different algorithms react to variations in these parameters. This analysis is essential to reveal the robustness of the algorithms and to understand the impact of parameter selection on solution quality.

In the sensitivity analysis, various combinations of population size (10, 20, 30, 50, 80) and iteration count (20, 50, 100, 150) were tested for each algorithm. Each parameter setting was evaluated through 30 independent runs (R = 30) to ensure statistical reliability. For each configuration, the average cost value obtained from the runs was used as the performance metric. The resulting variations in algorithm performance across different parameter settings are visualized using heatmaps, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Performance sensitivity heatmaps by population and iteration.

The results are presented in Figure 3, where the heatmaps depict the variations in algorithmic performance across different parameter configurations. In general, increasing the number of iterations enhanced solution quality for all algorithms; however, the extent of this sensitivity varied among them.

- ACO exhibited a strong dependence on iteration count, with stable yet significant improvements at higher iterations, while being largely insensitive to population size.

- PSO demonstrated rapid improvements within the first 80–100 iterations, after which the benefits plateaued, and showed moderate dependence on population size.

- WOA displayed gradual improvements but was highly sensitive to both iterations and population size, performing better with larger populations.

- KOA revealed iteration-dominant behavior with moderate effects from population size.

- KOA-WOA showed balanced behavior, improving consistently with higher iterations but stabilizing around medium population sizes (~50).

- IVY was sensitive to iteration increases and moderately responsive to population size, though its performance was less stable compared to others.

- WOA-PSO achieved its best performance around 100 iterations and a population size of ~50, demonstrating efficient convergence.

- GD-PSO benefited from both parameters, though improvements diminished beyond 100 iterations and 50–60 agents.

Table 2 presents the parameter sensitivity analysis of the algorithms, detailing their responsiveness to changes in iteration count and population size, along with key performance observations derived from empirical evaluations.

Table 2.

Parameter sensitivity of algorithms and observations.

From these results, a population size of 50 and 100 iterations were selected as optimal parameters. Increasing the population from 30 to 50 yielded notable improvements across most algorithms, while further increases showed marginal benefit. Similarly, extending iterations beyond 100 provided only limited gains relative to the additional computational cost. Therefore, the choice of 50 agents and 100 iterations represents an effective trade-off between convergence quality and efficiency. All subsequent experiments in this study were conducted using these settings to ensure fairness and consistency in the comparative evaluation.

Building on these findings, while the sensitivity analysis provides valuable insights into the behavior of algorithms under controlled synthetic conditions, it is important to recognize the implications for real-world applications. In practice, renewable energy generation is subject to higher variability and unpredictability due to changing weather patterns, seasonal dynamics, and demand fluctuations. These uncertainties may amplify or diminish the sensitivity of algorithms to their hyperparameters. Nevertheless, the observed patterns in iteration and population size dependencies suggest that the selected parameter configurations (50 agents and 100 iterations) are reasonably robust and can serve as a strong baseline when transitioning to real-world datasets. Future studies will focus on validating these findings using actual renewable generation and consumption data to better capture the stochastic nature of energy systems and to ensure that the algorithms maintain their performance under practical operating conditions.

Furthermore, in future studies, it will be important to consider the potential limitations of the proposed algorithms under extreme operating conditions, such as prolonged periods of low renewable generation (e.g., consecutive cloudy or windless days) and sudden spikes in energy demand. Addressing these extreme conditions in future sensitivity analyses will be crucial for fully assessing the robustness and practical applicability of the proposed energy management strategies.

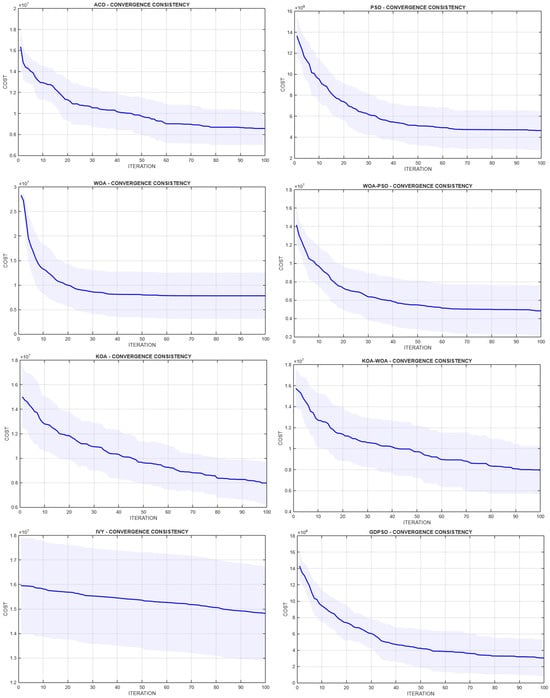

4.2. Convergence Consistency

In optimization studies, evaluating the performance of metaheuristic algorithms solely based on final solution quality can be misleading. Instead, convergence consistency, which captures how steadily and rapidly an algorithm approaches the optimal solution over iterations, provides a more comprehensive assessment of algorithmic behavior.

In this study, all algorithms were executed with a population size of 50 and a maximum of 100 iterations to ensure a fair and consistent comparison. Furthermore, each algorithm was independently run 30 times, and the convergence behavior was analyzed based on the average cost performance. The shaded regions in Figure 4 represent the standard deviation across runs, thus offering a measure of robustness against randomness.

Figure 4.

Comparative convergence curves of standard and hybrid metaheuristic algorithms (ACO, PSO, WOA, WOA-PSO, KOA, KOA-WOA, IVY, and GD-PSO) over 100 iterations and 30 independent runs. The shaded regions indicate the standard deviation, representing convergence stability.

As shown in Figure 4, the convergence behavior of the tested algorithms exhibits noticeable variation, both in terms of speed and stability:

- PSO demonstrates rapid initial convergence but tends to stagnate in later iterations, indicating strong exploitation capability yet limited exploration depth over time.

- GD-PSO, as a dynamic and gradient-guided variant of PSO, maintains the early convergence strength of PSO while slightly improving stability throughout the optimization process.

- WOA shows a smoother but slower convergence pattern, with gradual improvements becoming more evident in later iterations.

- In contrast, WOA–PSO, a hybrid approach combining the exploration mechanisms of WOA and the exploitation efficiency of PSO, significantly enhances convergence performance. It achieves faster early improvements compared to WOA and avoids premature stagnation, resulting in a steeper and more consistent trajectory.

- ACO and KOA also exhibit moderate convergence, with ACO showing a more gradual descent and KOA achieving steady improvement across iterations.

- The KOA–WOA hybrid outperforms both individual components by accelerating early convergence and demonstrating lower variance, suggesting improved robustness and balance.

- IVY, while biologically inspired and capable of navigating the search space, displays the slowest convergence, and its performance curve remains relatively flat throughout the iterations. This indicates limited capacity for both exploration and exploitation in the con-text of the tested problem.

The results from the convergence analysis highlight the importance of hybridization in metaheuristic optimization. Hybrid algorithms such as WOA–PSO and KOA–WOA successfully combine complementary strengths of their constituent algorithms. These hybrids not only achieve faster convergence rates but also exhibit greater consistency and reduced variance, making them more reliable across multiple runs. Additionally, GD-PSO stands out as a refined version of PSO, benefiting from adaptive mechanisms that improve convergence stability without compromising speed. While algorithms like IVY and standard WOA may require additional tuning or hybridization to be competitive, PSO and its enhanced variants prove effective in balancing convergence speed and solution quality. These findings confirm that convergence consistency is a critical criterion in the selection of appropriate metaheuristic algorithms for energy management systems. Algorithms that converge rapidly while maintaining stability are better suited for real-world applications where computational efficiency and reliability are essential.

4.3. Statistical Performance Comparison

To provide a more comprehensive evaluation of algorithmic performance, statistical metrics including average cost, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum cost values were computed for each optimization algorithm based on 30 independent executions. These results are presented in Table 3, allowing for a direct comparison of solution quality and consistency among the tested metaheuristic approaches. Among all evaluated algorithms, GD-PSO achieved the most favorable performance with an average cost of ₺2,903,637.51 and a relatively low standard deviation of ₺2,018,626.38, indicating a good balance between convergence quality and robustness. It also attained one of the lowest minimum cost values (₺1,006,536.46), showing its potential in reaching near-optimal solutions. The WOA–PSO hybrid algorithm also demonstrated competitive performance, achieving an average cost of ₺3,771,291.93 and a standard deviation similar to GD-PSO. Although slightly higher in average cost, WOA–PSO achieved a minimum cost of ₺973,943.77, suggesting that hybridization improved the convergence quality and reduced stagnation issues observed in the standard WOA. The PSO algorithm showed rapid convergence in previous convergence plots; however, its statistical results reflect variability across runs. With an average cost of ₺3,785,255.37 and a high standard deviation (₺2,961,357.74), it shows sensitivity to initial conditions, leading to inconsistent performance. WOA, while having a competitive minimum cost (₺644,556.85), had a high average cost (₺6,827,950.15) and the largest standard deviation (₺4,798,082.67), suggesting unstable optimization behavior and limited convergence reliability across different runs. KOA and KOA–WOA exhibited relatively higher average costs, but hybridization again led to improvement: KOA–WOA achieved a better minimum cost (₺2,723,651.00) and lower average compared to KOA. However, both algorithms still showed moderate-to-high variability. ACO recorded one of the highest average costs (₺8,416,626.31) and less competitive minimum values, indicating weaker performance under the same experimental settings. Lastly, the IVY algorithm delivered the least favorable results, with the highest average cost (₺14,750,985.52) and minimum cost (₺9,075,607.57) among all algorithms. It also showed poor consistency, as reflected in the high standard deviation (₺2,485,039.90).

Table 3.

Average results from 30 independent executions of metaheuristic algorithm-based optimization.

These results align with the convergence analysis and reinforce the conclusion that hybrid strategies (WOA–PSO, KOA–WOA) and enhanced versions like GD-PSO are more effective and reliable for complex energy optimization tasks.

To further validate these findings from a statistical standpoint, the Friedman test was employed, revealing a statistically significant difference among the compared algorithms (p-value < 0.05, χ2 = 128.36667, df = 7). This result indicates that at least one algorithm significantly outperformed the others in terms of cost minimization. In order to identify which specific algorithm pairs contributed to this difference, the Nemenyi post hoc test was subsequently applied. The Nemenyi test compares all pairs of algorithms using the difference in their average ranks obtained from 30 independent executions. The significance of the rank differences is determined by comparing them against a critical difference (CD) value. The CD is calculated using the following formula:

The symbols used in this study are defined as follows:

- : Critical value obtained from the Studentized range distribution. For a significance level of α = 0.05, the critical value is approximately ≈ 2.728 for large sample sizes.

- k: The number of algorithms being compared. In this study, k = 8.

- N: The number of independent executions or problems. In this case, N = 30.

Using the values ≈ 2.728, k = 8, and N = 30, the critical difference (CD) is calculated as approximately 1.73. Any mean rank difference between algorithm pairs that exceeds this value is considered statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Table 4 below summarizes the results of the Nemenyi pairwise comparisons between the algorithms.

Table 4.

Nemenyi post hoc test results showing pairwise differences between algorithms.

Table 4 presents the detailed results of the pairwise comparisons. According to the analysis, several statistically significant differences were observed. For instance, GD-PSO exhibited a statistically significant advantage over all other algorithms except WOA-PSO and PSO. Notably, WOA-PSO also performed significantly better than KOA, KOA-WOA, and IVY, but not significantly better than GD-PSO, confirming its competitive behavior. The ACO algorithm performed the worst in most pairwise comparisons. It was significantly outperformed by GD-PSO, WOA-PSO, PSO, WOA, and IVY, but not significantly different from KOA or KOA-WOA. On the other hand, IVY consistently ranked lowest among all algorithms, indicating inferior solution quality and statistical performance.

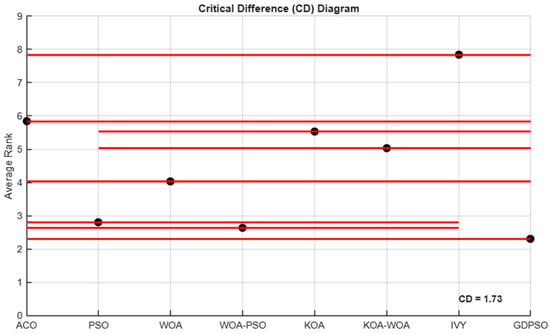

The critical difference (CD) diagram in Figure 5 visually illustrates these findings. Algorithms connected by horizontal lines are not significantly different, while disconnected ones exceed the critical difference threshold, indicating a statistically significant difference.

Figure 5.

Critical difference (CD) diagram for the Nemenyi post hoc test.

Additionally, Figure 5 shows the average ranking of each algorithm, which further supports the statistical findings. The GD-PSO algorithm achieved the lowest average rank, demonstrating the best overall performance, followed closely by WOA–PSO and PSO. Conversely, IVY and ACO received the highest ranks, indicating the weakest performances among the tested methods.

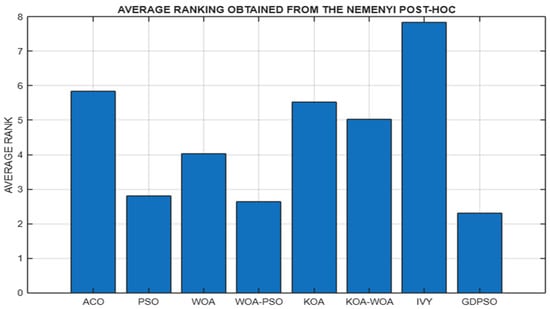

These findings confirm that hybrid metaheuristic structures such as WOA–PSO and advanced variants like GD-PSO significantly outperform traditional methods under the same experimental conditions. The consistency between statistical metrics (Table 3), average rankings (Figure 6), and pairwise significance results (Table 4 and Figure 5) reinforces the effectiveness of combining exploration and exploitation mechanisms in optimization problems. This comprehensive analysis underscores the importance of not only solution quality but also statistical reliability in selecting suitable algorithms for complex energy management tasks.

Figure 6.

Average rankings resulting from the Nemenyi post hoc analysis.

As a result, each algorithm was initially executed independently 30 times to evaluate performance based on the objective function. This phase included not only the assessment of final costs, but also sensitivity analyses with respect to population size and iteration count, as well as evaluations of convergence consistency across independent runs. These simulations revealed that different algorithms yield distinct solutions under identical system conditions, underlining the comparative strengths of both single and hybrid metaheuristic approaches.

In order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the comparative advantages observed, a detailed algorithm-specific performance analysis is presented below.

PSO exhibits relatively strong performance among classical methods, with low variability and a solid average ranking. Its global-best update mechanism efficiently guides particles toward promising regions. While it can suffer from premature convergence in complex problems, it still outperforms many alternatives like WOA, KOA, and ACO in this case.

WOA, despite its spiral update mechanism designed for exploration around the best solution, ranks below PSO in this problem. This suggests its search behavior may not be as effective in high-dimensional, complex cost landscapes, leading to suboptimal convergence compared to PSO.

ACO shows higher variability and one of the poorest rankings, likely due to its discrete path-construction mechanism being less suitable for continuous and high-dimensional scheduling problems.

IVY performs the worst among all evaluated algorithms. Its underlying mechanics may not scale well with the complexity of the 504-dimensional scheduling task, leading to weak overall performance.

GD-PSO clearly outperforms all classical methods, including PSO, with the best overall ranking. The incorporation of a sampled gradient enhances local refinement, allowing for more precise exploitation of high-quality regions and significantly improving convergence.

WOA-PSO achieves excellent performance, ranking just behind GD-PSO. By combining WOA’s spiral exploration with PSO’s exploitation, it benefits from both global search capability and fine-tuning ability. This hybridization leads to better results than either WOA or PSO alone.

KOA-WOA ranks in the middle of the pack, behind WOA-PSO and even WOA. While it improves over KOA alone, the added stochasticity from KOA’s movement appears to introduce noise that reduces convergence efficiency in smoother problem regions.

GD-PSO demonstrates better performance compared to PSO. This improvement is primarily attributed to its use of gradient-assisted updates, which enable more precise local search. In the context of the 504-dimensional scheduling problem, this capability helps the algorithm avoid swarm stagnation and leads to higher-quality convergence.

WOA-PSO outperforms both PSO and WOA individually. Its superior performance stems from the balanced combination of WOA’s exploratory capabilities and PSO’s exploitative behavior. This hybrid structure mitigates the limitations of each standalone algorithm, resulting in more effective optimization.

KOA-WOA shows improved results over KOA alone; however, it does not match the performance levels of WOA or WOA-PSO. The reduced effectiveness is likely due to the stochastic dynamics introduced by KOA, which can disrupt convergence and reduce overall stability in smoother problem landscapes.

The results clearly show that algorithmic hybridization—via mechanisms like gradient refinement, spiral-based exploration, and social learning—can significantly enhance performance in high-dimensional microgrid scheduling. GD-PSO and WOA-PSO stand out with the best rankings, outperforming traditional and hybrid algorithms alike. Meanwhile, simpler or purely stochastic approaches such as IVY, ACO, and KOA demonstrate lower effectiveness and are more prone to premature convergence or slower adaptation.

In the second phase of the study, each metaheuristic algorithm was executed once under identical environmental and operational conditions. This included the same time-series data for solar and wind generation, electricity prices, and load demand. Such a controlled setup ensured that performance differences could be attributed solely to the optimization capabilities of the algorithms rather than variability in external conditions.

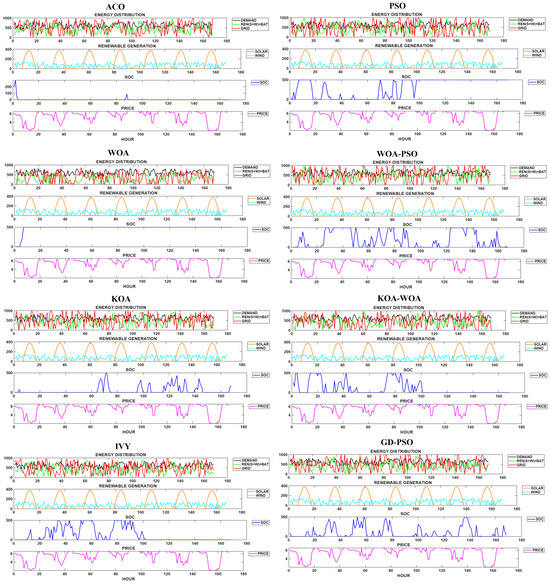

Figure 7 illustrates the hourly energy flow dynamics over a randomly selected week (168 h) for all eight optimization methods. The figure comprises four subplots for each algorithm: energy distribution, renewable energy generation, state-of-charge (SOC) of the battery, and electricity price.

Figure 7.

Weekly simulation results of the proposed algorithms.

Figure corresponds to a distinct optimization algorithm, displaying how it governs the distribution of energy among the grid, battery, and renewable sources, as well as the evolution of SOC throughout the week. The energy distribution plots clearly highlight the decision-making strategies of each algorithm under dynamic conditions, particularly their responsiveness to renewable availability and price signals. Distinct differences in battery utilization patterns are observable. For instance,

- GD-PSO and WOA-PSO maintain SOC within efficient operating zones, indicating advanced energy arbitrage strategies that align with market dynamics.

- KOA-WOA and PSO show moderately adaptive SOC profiles, occasionally failing to exploit low-price periods or renewable surpluses fully.

- In contrast, ACO and IVY display inconsistent SOC behaviors and greater reliance on grid energy, which leads to higher operating costs.

It is also worth noting that while the SOC constraint (40–60%) was implemented as a penalty-based soft constraint, rather than a strict boundary, some algorithms strategically exceed this range to achieve more favorable cost-performance trade-offs. This design choice allows algorithms flexibility in their energy storage strategies but also highlights the trade-off between feasibility and cost minimization.

Overall, the visualizations in Figure 7 offer crucial insights into the comparative strengths and weaknesses of each method in managing complex, real-time energy systems. The results underscore the importance of adaptive, cost-aware, and dynamic control mechanisms for achieving efficient energy integration in smart grids with renewable sources.

Table 5 presents key results from a single run of each algorithm, highlighting cost, renewable energy use, and grid consumption during peak prices for a clear performance comparison.

Table 5.

Best results from one execution of metaheuristic algorithm-based optimization.

Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of eight metaheuristic algorithms based on four key performance metrics: total cost, renewable energy plus battery usage, renewable energy ratio, and grid consumption during high electricity price periods. Among the evaluated algorithms, GD-PSO and WOA-PSO achieve the lowest total costs, ₺1,031,950.12 and ₺1,062,846.26, respectively, while maintaining high renewable energy ratios around 70% and substantial renewable energy plus battery utilization (over 71,000 kWh). This indicates effective cost reduction combined with strong renewable integration and battery management.

In contrast, the WOA exhibits the highest total cost (₺12,799,272.40) alongside the lowest renewable energy ratio (48.76%) and renewable energy utilization, reflecting less efficient performance in balancing cost and energy sourcing. Similarly, IVY shows a high total cost with moderately high renewable energy usage, suggesting suboptimal cost management.

Interestingly, ACO and KOA demonstrate relatively high renewable energy ratios (around 70%), but their total costs remain elevated compared to hybrid methods, highlighting that renewable penetration alone does not ensure cost efficiency. Grid usage during peak price periods varies across algorithms, with GD-PSO and PSO showing higher values, implying a trade-off between grid reliance and cost minimization.

Although the renewable energy share achieved by GD-PSO is slightly lower than that of WOA-PSO and KOA-WOA, the significantly lower total cost can be attributed to more strategic timing in grid energy usage. GD-PSO likely minimizes costs by avoiding electricity purchases during high-tariff periods and leveraging energy storage and load shifting more effectively. This highlights that cost efficiency in microgrid optimization depends not only on the quantity of renewable energy used but also on when and how energy sources—especially grid electricity—are utilized.

Overall, the results highlight the superior performance of hybrid metaheuristic approaches such as GD-PSO and WOA-PSO, which effectively balance cost savings, renewable energy utilization, and grid consumption during expensive hours, outperforming traditional algorithms in smart grid energy management.

4.4. Scalability Comparison of Algorithms

An initial assessment of computational efficiency was conducted by measuring the execution time of each algorithm for the baseline problem size, as shown in Table 6. Among the evaluated methods, WOA exhibited the lowest run time, indicating superior efficiency, whereas hybrid algorithms such as WOA–PSO and KOA–WOA, along with KOA, required longer execution times. Classical algorithms including PSO, IVY, GD-PSO, and ACO demonstrated moderate computational demand, balancing efficiency and solution quality, and highlighting the inherent trade-off between optimization performance and computational cost.

Table 6.

Execution times of algorithms for baseline problem size (7-day dataset).

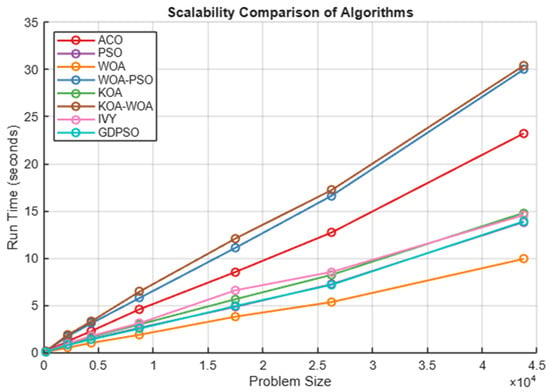

The scalability of the evaluated metaheuristic algorithms was further analyzed by measuring their computational run times across varying problem sizes, as depicted in Figure 8. Problem size was incrementally increased, and the corresponding execution times were recorded to assess how each algorithm’s performance scales with increasing complexity.

Figure 8.

Scalability comparison of algorithms.

The results reveal distinct differences in computational efficiency among the algorithms. The WOA consistently demonstrates the lowest run times across all problem sizes, indicating superior scalability and computational efficiency. In contrast, the hybrid algorithms WOA-PSO and KOA-WOA, along with the KOA algorithm, exhibit the highest run times, with execution times increasing sharply as the problem size grows. This suggests a trade-off between solution quality and computational demand for these more complex hybrid methods.

ACO displays moderate scalability, with run times increasing steadily but remaining lower than those of the more computationally intensive hybrids. The PSO, IVY, and GD-PSO algorithms show similar performance trends, with run times moderately increasing with problem size but maintaining better efficiency compared to hybrid approaches like WOA-PSO and KOA-WOA.

These findings underscore the importance of considering computational scalability alongside optimization performance when selecting an appropriate algorithm for real-time or large-scale energy management applications. While hybrid metaheuristic algorithms may offer improved solution quality, their higher computational cost may limit their practical applicability in scenarios with stringent time constraints. Conversely, algorithms such as WOA provide a favorable balance between solution accuracy and computational efficiency, making them suitable for large-scale implementations.

From a real-time grid management perspective, these scalability results provide valuable insights. Hybrid algorithms like WOA–PSO and KOA–WOA, despite their high solution quality, may face challenges in real-time decision-making due to longer execution times, particularly under tight operational time constraints. In contrast, WOA consistently exhibits low run times across varying problem sizes, indicating its capability to deliver sufficiently accurate solutions within time frames compatible with real-time grid operations. PSO, IVY, GD-PSO, and ACO demonstrate moderate computational demand, representing a potential compromise between solution quality and decision latency. Overall, these observations highlight that algorithm selection for real-time energy management requires careful balancing of optimization performance and computational efficiency to ensure timely and reliable grid control decisions.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a comprehensive comparative analysis of eight metaheuristic optimization algorithms for the optimal scheduling of a renewable-based smart grid system integrating solar, wind, and battery storage resources. The MATLAB-based framework evaluated classical metaheuristic algorithms, alongside hybrid metaheuristic approaches. Each algorithm was executed under identical environmental conditions, enabling a fair performance comparison.

The results indicate that hybrid algorithms, particularly WOA-PSO and KOA-WOA, achieved the lowest operational costs while maintaining high renewable energy utilization ratios (around 70%), demonstrating superior balance between cost efficiency and sustainable energy integration. Although some algorithms showed higher renewable ratios, their costs and grid usage during peak price periods were less optimal, highlighting the importance of strategic energy management beyond renewable maximization alone. The scalability analysis further revealed that while hybrid algorithms offer enhanced performance, they incur increased computational times, underscoring a trade-off between solution quality and computational efficiency.

From an energy management perspective, the framework successfully minimized grid energy costs, optimized battery state-of-charge trajectories, and effectively reduced reliance on high-price grid energy. Statistical analyses confirmed that the observed differences among algorithms are significant, supporting the robustness of the findings.

Overall, this work provides a flexible and reproducible platform for evaluating advanced metaheuristic algorithms in smart grid optimization. Future research should focus on extending the framework to longer planning horizons, incorporating real-world demand and price variability, and integrating physical battery degradation models. Additionally, exploring more sophisticated hybridization strategies, enhancing computational scalability, and embedding demand-side management and regulatory constraints will further improve practical applicability and sustainability of smart grid operations.

Furthermore, the proposed framework can be conceptually extended to a multi-objective optimization setting to address additional performance criteria beyond cost minimization. Future studies could incorporate objectives such as carbon emissions reduction, system reliability, and operational resilience alongside economic efficiency. By employing multi-objective metaheuristic algorithms, the trade-offs among competing objectives can be systematically explored, generating a Pareto-optimal set of solutions. This extension would enable the framework to provide decision-makers with a more comprehensive and balanced set of scheduling strategies, enhancing its applicability to real-world smart grid scenarios where multiple operational goals must be simultaneously considered.

Finally, practical implementation of the proposed algorithms requires careful consideration of integration with existing grid infrastructure and other energy management systems. Challenges may arise in coordinating real-time communication, handling legacy control protocols, and ensuring compatibility with demand response programs and distributed energy resources. Addressing these integration aspects in future studies will be essential to bridge the gap between theoretical optimization and operational deployment, ultimately enhancing the framework’s relevance and applicability in real-world smart grid environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., O.K. and S.V.; methodology, M.B.; software, M.B. and S.V.; validation, M.B., O.K. and S.V.; formal analysis, O.K. and M.B.; investigation, M.B. and S.V.; resources, O.K. and M.B.; data curation, M.B. and O.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and S.V.; writing—review and editing, M.B., O.K. and S.V.; visualization, M.B. and O.K.; supervision, O.K.; project administration, O.K.; funding acquisition, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN‘95-International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, Australia, 27 November–1 December 1995; pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Siano, P. Demand response and smart grids—A survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abido, M. Optimal power flow using particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2002, 24, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. Multi-objective optimisation using evolutionary algorithms: An introduction. In Multi-Objective Evolutionary Optimisation for Product Design and Manufacturing; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Coello, C.C. Evolutionary multi-objective optimization: A historical view of the field. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2006, 1, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, H. The path of the smart grid. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2009, 8, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, M.; Kaushik, S.C. A review on optimization techniques for sizing solar-wind hybrid energy systems. Int. J. Green Energy 2016, 13, 1564–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueasuk, W.; Ongsakul, W. Optimal placement of distributed generation using particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the Australasian Universities Power Engineering Conference (AUPEC), Melbourne, Australia, 10–13 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A.; Tao, Z.; Agyekum, E.B.; Fahad, S.; Tahir, M.; Salman, M. Sustainable rural electrification: Energy-economic feasibility analysis of autonomous hydrogen-based hybrid energy system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 141, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenel, F.A.; Gökçe, A.; Yüksel, M.; Yiğit, E. A novel hybrid PSO–GWO algorithm for optimization problems. Eng. Comput. 2019, 35, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Metaheuristic techniques in microgrid management: A survey. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 78, 101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.; Bhattacharyya, B.; Márquez, F.P.G. A hybrid optimization-based approach to solve environment constrained economic dispatch problem on microgrid system. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 307, 127196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y. Modelling and optimal energy management for battery energy storage systems in renewable energy systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.A.Z.; Abdelhamid, A.M.; Sultan, H.M. Comprehensive analysis of optimal power flow using recent metaheuristic algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandish, B.M.; Pushparajesh, V. Efficient power management based on adaptive whale optimization technique for residential load. Electr. Eng. 2024, 106, 4439–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, A.; Sundar, K.R.; Sivanesan, S.M.; Kumar, M. Multi-objective optimal scheduling of a microgrid using oppositional gradient-based grey wolf optimizer. Energies 2022, 15, 9024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Wadud, Z.; Khan, I.; Murawwat, S.; Hafeez, G.; Albogamy, F.R.; Khan, S.; Samuel, O. Demand response program for efficient demand-side management in smart grid considering renewable energy sources. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 53832–53853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, H. Integrated energy management of smart grids in smart cities based on PSO scheduling models. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 5794002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maqaleh, M.A.; El-Sawy, A.M.; Shaheen, A.M. Hybrid swarm intelligence models for renewable-based microgrid optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Akopov, A.S. MBHGA: A Matrix-Based Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for Solving an Agent-Based Model of Controlled Trade Interactions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 26843–26863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, G.; Bilgin, M.Z. Optimal power flow using kepler optimization algorithm for active power loss analysis in island mode: A case study. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Zare, M.; Trojovský, P.; Rao, R.V.; Trojovská, E.; Kandasamy, V. Optimization based on the smart behavior of plants with its engineering applications: Ivy algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 295, 111850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İzmir Development Agency, Investment in the Solar Energy. Sector in İzmir, Jan. 2016. Available online: https://www.kalkinmakutuphanesi.gov.tr/assets/upload/dosyalar/zmirde-gunes-enerjisi-sektorunde-yatirim.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- İzmir Development Agency. Investment in the Wind Energy Sector in İzmir, Jan. 2016. Available online: https://www.kalkinmakutuphanesi.gov.tr/assets/upload/dosyalar/zmirde-ruzgar-enerjisi-sektounde-yatirim.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- EPİAŞ (Energy Markets Operation Inc.). EPİAŞ Transparency Platform. Available online: https://seffaflik.epias.com.tr/home (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- EMRA (Energy Market Regulatory Authority). Electricity Tariff Tables. Available online: https://www.epdk.gov.tr/Detay/Icerik/3-1327/elektrik-faturalarina-esas-tarife-tablolari (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Oloyede, M.O.; Akpakwu, G.A.; Myburgh, H.C.; De Freitas, A.; Kunatsa, T. A review on state-of-charge estimation methods, energy storage technologies and state-of-the-art simulators: Recent developments and challenges. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Optimal allocation of wind power hybrid energy storage capacity based on ant colony optimization algorithm. Eng. Optim. 2024, 57, 1873–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.M.; Hekmati, A.; Bagheri, M. Enhancing cost-effectiveness in residential microgrids: An optimization for energy management with proactive electric vehicle charging. Front. Energy Res. 2025, 13, 1454448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, G.; Zhan, Y. Optimal power flow of power systems using hybrid whale and particle swarm optimization technique. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Energy Internet (ICEI), Guangzhou, China, 22–24 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Rui, C.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J. Energy management for microgrids integrating renewable sources and hybrid electric vehi-cles. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 69, 105937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lin, W.; Hu, G. An enhanced ivy algorithm fusing multiple strategies for global optimization problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2025, 203, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, S.; Khan, S.A.; Yang, S.; Khan, S.U.; Tahir, M.; Salman, M. Optimizing multi-modal electromagnetic design problems using quantum particle swarm optimization with differential evolution. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 101760–101775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzer, M.S.; Inan, O. Application of improved hybrid whale optimization algorithm to optimization problems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 12433–12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varaee, H.; Naser, S.H.; Mahsa, S. A hybrid generalized reduced gradient-based particle swarm optimizer for constrained engineering optimization problems. J. Soft Comput. Civ. Eng. 2021, 5, 86–119. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).