Abstract

Achieving sustainable economic growth requires a careful balance between public debt accumulation and the macroeconomic stability necessary for long-term development. While public debt can support growth through productive public investment, excessive debt may crowd out private investment, raise borrowing costs, and undermine financial stability, ultimately threatening economic sustainability. In this context, the quality of institutions plays a pivotal moderating role by fostering responsible debt management and ensuring that debt-financed investments contribute to sustainable development. In this context, this study investigates the relationship between public debt and economic growth, with a focus on the moderating role of institutional quality (IQ). Utilizing an unbalanced panel of 115 countries over the period from 1996 to 2021, this study tests the hypothesis that robust institutional frameworks mitigate the negative impact of public debt on economic growth. To address potential endogeneity, this study employs the dynamic system Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimation technique. The results reveal that, although the direct effect of public debt on economic growth is negative, the interaction between public debt and IQ yields a positive influence. Furthermore, the results indicate the presence of a threshold beyond which public debt begins to exert a beneficial effect on economic growth, whereas its impact remains adverse below this threshold. These findings underscore the critical importance of sound debt management strategies and institutional development for policymakers, suggesting that effective government governance is essential to harnessing the potential positive effects of public debt on economic growth.

1. Introduction

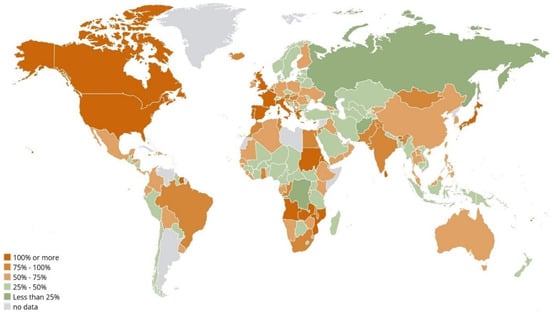

Public debt has always been a subject for researchers to study how it affects economic growth. After the 2008 economic crisis and COVID-19, debt levels rose rapidly across the globe, as shown in Figure 1, and academics anticipate that they will remain high due to underlying reasons. High debt in many countries has spurred discussion regarding macroeconomic variables and long-term economic growth. Theoretically, governmental debt harms economic growth (Schclarek [1]). When kept below such thresholds, however, public debt can support economic growth by financing productive investments and helping countries achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs) related to economic growth and poverty reduction. The empirical literature reports a bidirectional causal relationship between debt and growth, showing that threshold regression techniques produce nonlinearity that is substantially more challenging than that seen in models with exogenous thresholds. In principle, it is essential for achieving sustainable development goals such as economic growth and profit. Moreover, debt management plays a critical role in supporting sustainable development. While public debt can provide essential resources for financial systems and help facilitate loans and investments, high debt levels may have long-term adverse consequences for fiscal sustainability and economic stability. The public debt and deficit, which are still increasing in many nations in the wake of the last crisis, are causing government anxiety. Public spending is also an important indicator of financial growth and the long-term stability of public finances [2]. Governments have a critical role in distributing money and resources in the economy [3].

Figure 1.

Map of Public Debt as (% of GDP) around the World in 2021. (Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook).

While Classical Economics traditionally focuses on economic growth and debt dynamics, it is increasingly important to explore how non-economic factors, such as IQ, influence sustainable economic development. For example, the quality of the organization has a significant impact on the burden of debt [4]. Several recent studies have shown that state debt is the result of corruption [5], and through their study on the relationship between institutions and public debt, Tarek and Ahmed [6] concluded that weak institutions are the root cause of rising levels of debt. Due to the debt–growth nexus and financial agreements, academics are interested in bridging the gap between IQ and financial markets. Inability to follow credit agreements makes individuals more likely to miss payments.

Several studies have highlighted the conditional role of institutions in determining whether public debt acts as a burden or a catalyst for development. Yet, the precise mechanisms through which IQ moderates the debt–growth nexus are not fully understood. IQ, in the context of this study, refers to the effectiveness and integrity of formal institutions that shape economic and political interactions. It encompasses key dimensions such as control of corruption (COC), government effectiveness (GEF), rule of law (ROL), regulatory quality (REQ), political stability and absence of violence (PSV), and voice and accountability (VAA). These elements influence the credibility, transparency, and efficiency of public policy, particularly in fiscal governance and debt management. A clear understanding of these institutional attributes is essential to assess their moderating role in the public debt–economic growth relationship.

The world’s enormous and complicated financial markets depend on each party’s contractual rights and responsibilities [7]. Asymmetric information and agent information transmission are crucial to resource allocation. Investment and capital are more susceptible to institutional contexts and financial agreements in economies with asymmetric information. A financial contract may be too tempting to breach if, for example, low-quality institutions are engaged because of the prospective cash gains. Institutions underpin financial markets’ capacity to finance economic activity. Thus, a nation’s economy depends on its institutions. This important problem is underexplored in academia, although rule of law and government quality are linked [8]. IQ is viewed as a precondition for growth in the economy [9,10].

A key contribution of this study lies in its examination of the marginal effect of public debt on economic growth as conditioned by IQ. The marginal effect refers to the change in the dependent variable resulting from a one-unit change in an independent variable, holding other variables constant. In linear regression models, this effect is constant and directly represented by the regression coefficient. In linear regression models, marginal effects are constant and directly interpreted through the coefficient values [11]. However, in nonlinear models such as logit or probit, the marginal effect varies depending on the values of the explanatory variables, and it is typically calculated as the derivative of the estimated probability with respect to the variable of interest [12]. Scholars often use marginal effects to interpret the practical significance of model coefficients, particularly when analyzing how policies, economic factors, or institutional changes influence outcomes. In this context, it is especially important in institutional economics, where the impact of GEF, REQ, or ROL on growth may not be linear or uniform across countries or time periods [13].

In the context of marginal effect and unlike traditional approaches that assume a uniform relationship, our analysis reveals that the impact of public debt on growth varies significantly across different levels of institutional development. When IQ is below a certain threshold, increases in public debt are associated with adverse growth outcomes, likely due to governance inefficiencies and weak fiscal oversight. However, once IQ surpasses this critical threshold, the marginal effect becomes less negative or even turns positive, indicating that strong institutions can enhance debt management and support productive public investment. By quantifying these threshold effects, our study offers novel insights into the nonlinear dynamics of the debt–growth nexus and underscores the central role of IQ in transforming public borrowing into a catalyst for sustainable economic development.

Although previous research has examined the relationships between public debt, IQ, and economic growth, key empirical gaps remain. First, most existing studies focus on either the direct effects or simple moderation effects of IQ without exploring the nonlinear dynamics or threshold levels at which institutions alter the debt–growth relationship. This study addresses that gap by identifying precise institutional thresholds beyond which public debt contributes positively to economic growth. Second, unlike earlier work, we draw on two complementary global datasets, World Governance Indicators (WGI) and International Country Risk Guide (ICRG), to comprehensively capture institutional dimensions. Third, we employ a combination of advanced estimation techniques, including dynamic system GMM, Panel Threshold Regression (PTR), and Extended Threshold Interactive Regression (ETIR) to ensure the robustness of our findings across different empirical frameworks. These contributions distinguish our work by providing new insights into how the interaction between IQ and public debt can shape long-run sustainable growth trajectories.

The other sections of this study are organized as follows: Section 2 provides the literature review. Section 3 introduces the theoretical framework and model; Section 4 provides the findings and discussion; Section 5 provides the robustness analysis; and lastly, Section 6 summarizes this research and discusses the policy implications.

2. A Literature Review

2.1. Public Debt and Economic Growth

The detrimental impact of public debt on economic growth has been posited by classical economists such as Smith [14], Mill [15], and Ricardo [16]. The Ricardian equivalence posits that the lifetime present value of an individual or family’s after-tax income determines their level of consumption. Moreover, according to this theory, public expenditures are equivalent whether they are funded through borrowing or taxation. Individuals save more by purchasing the bonds under this scenario, where the government’s decision to reduce taxation to stimulate the economy leads to this outcome. Therefore, government indebtedness has no discernible effect on economic growth, as Ricardo noted. The Investment Savings–Liquidity Preference and Money Supply (IS–LM) macroeconomic model, which is based on Keynesian economics, posits that an increase in public debt resulting from deficit-financed fiscal policy raises transaction demands for money and prices, as well as income levels. However, this leads to an increase in interest rates on public bonds because of the fixed money supply. If the private sector perceives public bonds as a net asset, the deficit will exacerbate private spending, transaction demand, interest rates, and prices, in accordance with Keynesian theory. Accelerated effects have the potential to strengthen the impacts of expansionary fiscal policy on capital formation, consequently stimulating economic growth. Conversely, proponents of monetarism contended that the financed debt has a macroeconomic impact of deterring private investment through the escalation of interest rates. Public debt will consequently exert a detrimental influence on economic growth. Furthermore, according to the theory of debt overhang, in the event that a nation’s future debt surpasses its capacity for repayment, the anticipated expenses associated with servicing that debt would deter both domestic and foreign investment, consequently impeding economic expansion.

According to established theory regarding the association between debt and growth, public debt stimulates aggregate demand and, thereby, exerts a positive impact on growth in the short term [17,18]. Nevertheless, several prior investigations have identified an inverse correlation between debt and growth, which is in opposition to the Ricardian equilibrium [19,20]. Several investigations, however, provide support for Barro’s theory of Ricardian equivalence [21]. Additionally, a number of studies have produced contradictory results. Nevertheless, this matter remains unresolved; however, in recent years, the majority of researchers have investigated the debt–growth relationship via a variety of channels, deviating from this conventional view.

According to some studies, a substantial public debt is extremely detrimental over time. In addition to long-term interest payments, a nation with a greater level of indebtedness is also exposed to sovereign risk [22,23]. Other studies investigate the pathway through which high levels of government debt distort tax increases [24]. Higher indebtedness leads to inflation [25]. However, Cochrane [26] analyzed the trend of diminishing public expenditure on infrastructure. Debt levels that are excessively high may restrict the implementation of discretionary counter-cyclical policies. As a result, increased economic volatility ensues, leading to a decline in growth. An extreme instance of high indebtedness occurs when it disrupts the banking sector and generates a monetary crisis, subsequently resulting in economic instability [27].

2.2. Institutional Quality and Economic Growth

Institutional quality refers to the collective elements of traditions and establishments that facilitate the exercise of governmental power. IQ encompasses the processes of government selection, observation, and replacement, as well as the government’s ability to proficiently formulate and execute sound policies. Additionally, it involves the recognition of citizens and the state in relation to the institutions governing economic and social interactions between them. The significance of IQ within international organizations has been a prominent aspect since the late 1990s. Quality institutions play a crucial role in fostering economic growth [28]. However, some articles emphasize the significance of IQ and the requisite institutional circumstances. IQ is seen by several scholars as a predictor of economic development [29]. Government institutions have a crucial role in facilitating and fostering economic progress [30]. Some authors make reference to the significance of robust institutions in shaping sustained economic development, highlighting the predicament and lack of progress experienced by nations with weaker institutional frameworks [31,32].

The quality of institutions influences economic expansion both directly and indirectly [33]. In addition to fostering economic expansion, high-quality institutions erode income disparity. Quality institutions have become increasingly significant in recent decades. This is becoming an increasingly vital factor on a global scale, especially for developing nations seeking to attract more investment and achieve sustainable growth [34]. Inadequate IQ results in ineffectual political and economic activities, which hinder the promotion of productive endeavors [10]. As mentioned by Globerman and Shapiro [35], in addition to increasing economic resources, economic development contributes to the establishment of institutions. In addition, they assert that institutions are the foundation for the ROL, low corruption, and so forth. Likewise, it is evident that developed nations exhibit greater political stability in comparison to developing or impoverished countries.

Furthermore, it appears that the six dimensions provided by WDIs are interconnected and capable of influencing one another. As an illustration, Kayani and Gan [36] demonstrate that investment is negatively impacted by inadequate IQ. Corruption adversely affects investment by virtue of its direct correlation with governmental inefficiency, legal laxity, and political instability. Additionally, economists provide a concise analysis of the interrelationships and mutual influences among these variables. The ROL deficiency fosters corruption and has detrimental repercussions on the economy. Bribery is exacerbated by inadequate government policies and substandard regulatory standards, which impede competition. Consequently, the safeguarding of property rights may be compromised, leading to public sentiments of vulnerability towards the ROL and a perception that tax dollars are being misapplied.

2.3. Institutional Quality as a Moderator

The relationship between public debt and economic growth has been the subject of sustained scholarly attention, yet remains deeply contested in terms of both direction and magnitude. Traditional growth models such as the Solow–Swan and endogenous growth frameworks argue that excessive debt can crowd out productive investment and slow growth, particularly when debt servicing costs rise above a critical threshold [37,38]. However, this relationship is not homogeneous across institutional settings. Increasingly, scholars argue that the quality of institutions and governance structures can significantly moderate the debt–growth nexus [10].

Several recent empirical studies support this proposition. Sani, Said [39] emphasize that in Sub-Saharan Africa, weak institutions undermine the capacity of governments to use debt productively, thereby amplifying their negative effects on growth. Similarly, Iyoboyi and Badiru [40] used data from Nigeria and found that the effect of debt on growth is positive up to a threshold value of GDP, beyond which its effect becomes negative and significant. This finding is echoed in [41], who show that IQ significantly moderates the impact of public debt on growth in low-income countries, suggesting that sound governance structures can transform debt into a growth-enhancing tool. In the same context, Abbas and Junqing [42] used a panel of 106 countries and found that governance plays a moderating role in the debt–growth relationship. Moreover, there is a threshold value of governance beyond which pubic debt has a positive relationship with economic growth and vice versa in case of values below the threshold.

The more recent literature further elaborates on this moderating role. Ashogbon and Onakoya [43] use dynamic panel data methods to demonstrate that good governance indicators such as REQ and ROL attenuate the negative effects of public debt in West African economies. El-Naser [44], when studying MENA countries, provided evidence that institutional fragility magnifies the growth-reducing impact of high public debt. Oppong and Salifu Atchulo [45] extend this analysis to emerging markets and underscore the role of public accountability and political stability in mediating the fiscal–growth relationship.

From a policy perspective, these findings imply that strengthening institutions through improved transparency, ROL, and governance accountability not only enhances debt management but also supports sustainable economic growth. Therefore, ignoring the institutional dimension may lead to misleading conclusions about the debt–growth relationship. In line with these arguments, our study contributes to the existing literature by empirically testing the moderating role of IQ in the relationship between public debt and economic growth across developing countries, using a comprehensive panel data approach.

In general, the existing body of evidence suggests that the quality of institutions has a significant impact on both the magnitude of public debt and the overall stability of macroeconomic conditions. There exists a certain degree of correlation among all six characteristics of IQ. The presence of weak IQ tends to increase the amount of public debt due to rent-seeking activities and the distribution of government expenditure.

The primary aim of this research is to address the existing gap in the literature by examining the moderating function of IQ in the link between debt and economic growth. Given this consideration, we investigate the threshold values of all six measures of IQ in relation to the link between debt and economic growth.

3. Theoretical Framework and Model

3.1. Theoretical Framework

The debt–growth nexus has been quantified using a variety of theoretical frameworks; nevertheless, the Solow model of sovereign debt serves as the foundation for our analysis of this relationship. Both the ever-present income hypothesis and the family dynamic optimization model are open for discussion, both from a theoretical and an empirical perspective [46]. According to the permanent income theory, families choose their spending levels not based on their present income but rather on their lifetime income. Nevertheless, a number of empirical pieces of research point to a correlation between one’s present income and their level of spending [47].

Human capital is included in customer behavior, unlike the Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans (RCK) and Blanchard models. Human capital availability affects governmental debt under the Solow model, as based on the Solow model of Weil [48] with human capital enhancements. The production function is given by Equation (1):

The steady state output is given by Equation (2):

where and show the rate of savings and physical and human capital, respectively.

To assess debt load, Equation (2) incorporates the debt variable [49]. First, it is necessary to determine how the state of the budget influences the overall savings rate. The total savings account considers both private and public funds. For the sake of simplicity, governmental savings only apply to physical capital.

In Equation (3), is the rate of private sector savings because we assume absolute crowding out, government savings have no effect on private savings. Meanwhile, the budget deficit can be given by of the private savings as mentioned in Equation (4):

And by putting the value of in Equation (3), it gives Equation (5):

Then, putting these values in Equation (2) of the output gives us Equation (6):

By replacing , , and by , and , we will get the Equation (7):

Suppose = , where changes as the population growth rate, technological growth rate, and production function parameters all vary as the private sector saves. The apparent justification for this position is that, if the rate of saving in the private sector is substantial, the budget deficit that is required to keep a particular debt ratio will have a negligible effect on savings, which will result in only slight shifts from the steady-state level of output [49].

3.2. Model

This study applies the neoclassical growth model to the preceding portion. The neoclassical growth model is necessary for modeling the aggregate production function:

In the preceding Equation (8), Y is the total output; K represents capital stock, and L signifies labor. During the course of examining this production function, the concept of convergence becomes apparent due to the presence of heterogeneity across countries. According to this concept, countries with lower values may attain a continuous state of development more quickly than countries with higher values since their return on capital is higher [50]. Debt and economic growth form a “U-shaped link” [51]. As argued by Cunningham [52], by the incorporation of public debt (Debt) in the model, the form of Equation (8) is Y = f(K, L, Debt).

In this analysis, to examine the debt–growth relationship, we employ IQ as a moderator variable, and marginal effect can be assessed after the inclusion of IQ, our model has the following structure, as shown in Equation (9):

After adding the interaction term, Equation (10) presents the interacted model:

where i represents the number of countries, which is 115; t is the time span 1996–2021; is the economic growth; is the institutional quality; represents country’s specific fixed effects, and is the error term. is the sum of control variables. It consists of total factor productivity (TFP), inflation (INF), government size (GS), exports (EXP), and urbanization (URB). Since our main objective is to evaluate the moderating effect of IQ on the debt–growth relationship, we can compute the marginal impact of debt using the following Equation (11):

Equation (11) implies that IQ affects the marginal impact of public debt on economic growth. This shows that the marginal impact across countries varies by institution quality.

3.3. Data

This study used a panel dataset of 115 economies, including both developing and developed countries, for the period of 1996–2021. The data for the IQ were extracted from WGI. Other variables used in this analysis are extracted from the World Development Indicators (WDI), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and Penn World Table 10.0. A list of countries is presented in Table A1. First of all, we used the GDP growth rate to measure the economic growth. Debt is the independent variable. IQ is the moderating variable. Furthermore, a set of control variables is used in this research. All variables with their source of data are described in Table 1, and the descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Description of Data.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics.

For IQ, we used all six indicators as defined by WGIs. These indicators range from −2.5 to +2.5, but we rescaled from their original range of −2.5 to +2.5 to a normalized scale of 0 to 10 using a linear transformation method, following the previous studies such as [42,53]. This ensures that the transformed scores lie within the range of 0 (lowest IQ) to 10 (highest IQ), making interpretation more intuitive.

3.4. Estimation Strategy

This study utilizes an unbalanced panel dataset comprising 115 countries observed over the period from 1996 to 2021. Given the dynamic nature of the economic growth process and the likelihood of endogeneity due to reverse causality, simultaneity, and omitted variable bias, we employ the two-step system GMM estimator proposed by Blundell and Bond [54]. The inclusion of lagged dependent variables as regressors introduces correlation between explanatory variables and the error term, which traditional estimation techniques, such as fixed effects (FE) or random effects (RE), fail to address adequately. The System GMM technique is particularly appropriate in our context, as it provides a robust framework for analyzing dynamic panel data with a relatively short time dimension and a large number of cross-sectional units [55,56].

The System GMM estimator improves upon the earlier difference GMM approach [57] by combining equations in both first differences and levels, thereby enhancing efficiency and reducing the weak instrument problem. In the differenced equation, lagged levels of the regressors are used as instruments to address endogeneity and eliminate unobserved country-specific effects. In the levels equation, the instruments are constructed from lagged first differences under the assumption that these differences are uncorrelated with the fixed effects. This dual-equation system enables the estimator to capture both short-term dynamics and long-term structural relationships more accurately, even when explanatory variables are persistent over time.

The general form of our dynamic model in levels is expressed as

where denotes the dependent variable; is a vector of explanatory variables; represents unobserved country-specific effects, and is the error term. The differenced form of this model is given by

This transformation removes unobserved fixed effects and introduces a new composite error term. However, it may still suffer from endogeneity if the lagged differences are correlated with the new error term; hence, the need for suitable instruments.

To ensure the validity of our instruments and model specification, we conducted several diagnostic tests. The Sargan [58] test of over-identifying restrictions assesses whether the instruments used are exogenous, i.e., uncorrelated with the error term. A failure to reject the null hypothesis indicates valid instrumentation. We also apply the Arellano–Bond test for second-order serial correlation (AR(2)), as the absence of such correlation in the differenced residuals is crucial for the consistency of the GMM estimator. Furthermore, we address concerns about instrument proliferation, which can overfit endogenous variables and weaken test power by limiting the number of instruments based on Roodman’s [59] guidelines.

The two-step variant of System GMM, used in this study, is preferred over the one-step version due to its asymptotic efficiency and use of a robust weighting matrix. However, the standard errors in two-step GMM are known to be downward-biased in finite samples. To correct for this, we apply Windmeijer’s [60] finite-sample correction, which adjusts the standard errors for greater accuracy. Overall, System GMM allows us to consistently estimate the dynamic effects of our variables of interest while accounting for endogeneity, unobserved heterogeneity, and measurement error, making it the most appropriate econometric technique for our analysis.

3.5. Robustness Testing

To further assess the sensitivity of our results to data or econometric parameters, we provide robustness tests. First, we include additional factors that might serve as proxies for IQ; we substitute WGI data with a variable from the International Country Risk Guide dataset. Second, we employ nonlinear PTR to substantiate the computation of the threshold in the baseline results and discussion section. Third, following the contemporary economic growth literature on interactive regressions, for example, Tchamyou and Asongu [61] and Hansen [62], we also employ ETIR to see whether the results hold true using these three alternative regression methods.

The PTR model, developed by Hansen [62], is a nonlinear panel data technique that captures regime-dependent relationships by allowing for the effect of an explanatory variable on the dependent variable to vary depending on the value of a threshold variable. Unlike traditional linear models, PTR endogenously determines the threshold point at which the relationship changes, making it especially useful for examining economic phenomena where effects are conditional on institutional or structural factors. For example, the impact of debt on economic growth may differ across countries with low versus high levels of IQ. PTR also accommodates individual fixed effects, enabling control for unobserved heterogeneity across cross-sectional units, and it can be applied to both balanced and unbalanced panels. The standard PTR model is as follows:

where is the dependent variable; is the key explanatory variable; is the threshold variable, and is the threshold value. The indicator function I(·) captures regime shifts, enabling the estimation of distinct coefficients and across low- and high-threshold regimes. This approach provides valuable insights into the conditional and potentially nonlinear effects of policy-relevant variables, particularly in contexts where IQ plays a moderating role.

In this study, we have also used ETIR as given by Wang [63], which is an advanced econometric modeling approach that builds upon the traditional PTR by incorporating interactive terms between explanatory variables and the threshold variable. While standard PTR models allow for coefficients to switch across regimes defined by a threshold value, ETIR further enables continuous interaction between variables and the threshold variable itself, offering a more flexible framework for capturing gradual or non-binary changes in relationships. This is particularly useful when the effect of a variable such as debt on an outcome like economic growth intensifies or weakens progressively as IQ changes rather than abruptly shifting at a single cutoff point. The ETIR model can be stated as follows:

The advantages of ETIR include its ability to model smooth transitions in the influence of variables, account for heterogeneous effects across varying levels of the threshold variable, and provide a richer interpretation of moderation mechanisms. Unlike PTR, which imposes sharp thresholds and can sometimes oversimplify complex dynamics, ETIR reflects real-world economic relationships where policy effectiveness or institutional influence evolves gradually. This makes it especially valuable for analyzing the conditional impact of macroeconomic variables such as debt, inflation, or trade under varying levels of IQ, governance, or financial development.

4. Results and Discussions

Baseline Results: Using System GMM

Table 3 displays the results of the two-step dynamic system GMM estimator. Using the previously given Equation (11) and the results of the GMM system, we calculate the IQ threshold over which the impact of the debt turns positive.

Table 3.

Dynamic system GMM estimates using WGI dataset.

The coefficient of debt is significantly negative across all the models, with the coefficient value ranging from −0.237 to −1.010, indicating that higher levels of debt are related to a substantial decline in economic growth. Moreover, the strong statistical significance of these coefficients (mostly at the 1% level) underscores the reliability of this negative relationship in the sample. The results imply that debt is a critical factor that countries need to manage carefully, as excessive debt accumulation can substantially hamper their economic growth prospects.

In the context of IQ, the coefficient of IQ measured by VAA is 0.686 in Column 1 and 0.237 in Column 2. This suggests that when VAA improves, it indicates greater freedom of expression, media independence, and public participation, which can have a positive impact on economic growth.

In Columns 3 and 4, the IQ is measured by PSV, and the coefficients are 0.664 in Column 3 and 0.199 in Column 4, with p < 0.01, suggesting that PSV has a positive relationship with economic growth. The strong positive effect indicates that a politically stable environment significantly promotes economic growth, likely by minimizing uncertainty, deterring conflict, and encouraging investment.

The coefficients for GEF are 0.599 and 0.234 in columns 5 and 6, respectively. These results imply that improvements in public service quality, civil service competence, and policy formulation significantly contribute to economic growth. GEF enhances policy credibility and public investment efficiency, allowing for the resources to be allocated where they are most productive.

The IQ measured by REQ, with coefficients of 0.233 and 0.275 in columns 5 and 6, shows strong and consistent positive effects on economic growth. These results are theoretically supported by endogenous growth models, where efficient regulatory frameworks reduce market distortions and transaction costs, thereby enhancing innovation, entrepreneurship, and TFP.

The IQ measured by ROL shows the coefficients of 0.228 and 0.263 in columns 9 and 10, respectively. The positive and highly significant values reflect that strong legal institutions characterized by property rights protection and contract enforcement directly boost economic growth. This shows that a well-functioning ROL reduces uncertainty, fosters investment, and ensures the efficient resolution of disputes.

The IQ measured by COC shows the coefficients of 0.420 and 0.153 in models 11 and 12, respectively. The positive coefficients suggest that COC has a meaningful impact on improving economic performance. Corruption increases the cost of doing business. Controlling corruption enhances institutional efficiency and ensures that public and private sector interactions are governed by fair and predictable rules. Overall, all the indicators show a positive relationship with economic growth.

Moreover, the results of the interaction term, which are the main results in this study, indicate that in the second model (column 2), where the interaction term () is introduced, the interaction term is significantly positive (0.129, p < 0.01). This indicates that although debt is harmful in general, its adverse effect diminishes as IQ measured by VAA improves. In other words, IQ plays a moderating role, mitigating the negative impact of debt on economic growth. The turning point analysis reveals that the harmful impact of debt disappears when the IQ index exceeds a threshold value of approximately 7.55 (on the normalized 0–10 scale). According to column 2, the marginal value is −1.103 + 0.129 × VAA, indicating that debt may boost economic growth in nations with VAA values more than 7.55. Therefore, nations with a VAA less than 7.55 find that debt has an unfavorable effect on economic growth.

Column (4) introduces the interaction term to explore whether political stability conditions mitigate the effect of debt on economic growth. The results show that the interaction term is positive and highly significant (0.143, p < 0.01). This indicates a moderating effect, meaning that the negative impact of debt on economic growth weakens as political stability improves. In other words, in politically stable environments, countries are better able to manage and utilize debt in a way that does not hinder economic performance. To quantify this moderating effect, a threshold value for IQ can be calculated using the formula given by Equation (11), and the calculated threshold value for PSV is 7.04. This implies that when PSV exceeds a value of approximately 7.04, the net effect of debt on economic growth becomes neutral or even positive. This threshold is meaningful for policy, especially in developing countries seeking to leverage public borrowing for growth-enhancing investments without destabilizing their economies.

Column (6) provides the results of incorporating the interaction term, which measures the moderating role of GEF in the debt and economic growth nexus. The results indicate that although the baseline results have an adverse effect of debt on economic growth, the interaction term is positive and statistically significant (0.114, p < 0.01), suggesting that GEF helps to mitigate the negative impact of debt. This finding suggests that governments with effective institutions are better able to allocate debt resources efficiently, implement counter-cyclical policies, and maintain public trust in fiscal governance. As the interaction is positive, it implies that the harmful effects of debt diminish as the GEF improves. A threshold analysis indicates that once GEF exceeds 7.68, the net effect of debt on economic growth becomes neutral or positive. This implies that countries with GEF above this value can potentially absorb and manage higher debt levels without economic growth being compromised.

In column (8), the interaction term is positive and statistically significant (0.091, p < 0.01), suggesting that as REQ improves, the detrimental effect of debt is attenuated. This implies a moderating effect, where strong regulatory institutions help buffer the economy against the adverse consequences of public borrowing. The net effect of debt on economic growth becomes less negative as REQ increases, and a threshold analysis shows that the turning point occurs around 7.23. Hence, when the REQ exceeds 7.23, the negative impact of debt on economic growth may be neutralized or even reversed. These findings are theoretically consistent with frameworks that emphasize the role of IQ in fiscal policy effectiveness. Countries with sound regulatory systems are better equipped to design credible and growth-enhancing debt-financed investments while minimizing risks like corruption, inefficiencies, or policy reversals.

In column (10), the results show that the interaction term is positive and significant (0.095, p < 0.01), signifying that improvements in ROL attenuate the negative effect of debt on economic growth. This supports the theoretical proposition that legal institutions, through stronger enforcement of laws, protection of property rights, and judicial efficiency, enhance public accountability and ensure that debt is used more productively. The fiscal governance literature asserts that strong legal systems are crucial for debt sustainability and efficient public investment. To identify when the moderating effect offsets the negative debt-economic growth relationship, a threshold level of IQ is 7.24. This implies that once the ROL exceeds approximately 7.24, the net effect of debt on economic growth becomes neutral or potentially positive. Thus, column (10) provides strong evidence that while debt tends to suppress economic growth, countries with stronger ROL can effectively mitigate this impact and potentially harness debt for development purposes.

The results in Column (12) show that the coefficient of the interaction term is positive and significant (0.140, p < 0.01). This suggests that control of corruption significantly moderates the adverse effect of debt on economic growth. In practical terms, this means that in countries with stronger anti-corruption institutions, debt is less harmful and can even become growth-supportive if corruption is sufficiently contained. Theoretically, this finding asserts that corruption undermines the efficiency of public spending, distorts fiscal policy, and increases the likelihood of debt mismanagement. When corruption is controlled, however, debt-financed expenditures are more likely to be channeled into productive investments such as infrastructure, education, or health. A threshold analysis can quantify the COC at which the debt’s negative effect is neutralized when the value of COC is greater than 7.21. This implies that when a country’s COC index exceeds 7.21, the net effect of debt on economic growth turns neutral or positive. This threshold is policy-relevant, as it indicates the minimum quality of COC needed to ensure that public borrowing does not impede economic growth. The result emphasizes the importance of transparency, accountability, and institutional checks in managing debt sustainably and promoting inclusive development. Results of the marginal effects of debt on IQ using the WGI dataset are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Marginal effect (WGI dataset).

Overall, the interaction terms between debt and the various dimensions of IQ consistently exhibit positive and statistically significant coefficients across all relevant models. These findings suggest that strong institutional frameworks can effectively mitigate the adverse impact of debt on economic growth. While debt alone exerts a significant negative influence, indicating that excessive borrowing may hinder economic growth through mechanisms such as debt overhang or fiscal crowding-out, these institutional variables appear to act as moderators that cushion or reverse this harmful effect. For instance, a higher level of GEF or REQ may ensure that debt-financed expenditures are channeled into productive investments, thereby offsetting the drag on economic growth. Similarly, political stability and ROL likely reduce uncertainty and transaction costs, making debt more manageable and growth-enhancing. These results align well with the theoretical foundations of New Institutional Economics and the fiscal governance literature, which emphasize that the IQ determines whether debt becomes a burden or a tool for development. Thus, in countries with strong institutions, debt may not necessarily impede economic growth, as the institutional environment provides the necessary capacity, accountability, and efficiency to manage it sustainably.

Moreover, the results of lagged GDP per capita show that the coefficient on lagged GDP per capita is mostly negative and statistically significant, except in a few specifications (e.g., columns 3 and 5) where it is small and insignificant or even slightly positive (e.g., column 5: 0.010). A negative coefficient suggests conditional convergence, meaning that countries with higher initial income levels grow more slowly over time. However, the magnitude is relatively small (e.g., −0.020 to −0.141), indicating slow convergence rates, typical in cross-country panel studies.

The coefficient on TFP is positive and highly significant (p < 0.01) across all specifications, ranging from 0.127 to 0.318. This robust result indicates that improvements in productivity strongly enhance economic growth, which is consistent with endogenous growth models (e.g., Romer [64,65]) that highlight innovation, technological efficiency, and factor reallocation as key drivers of long-run output growth. The largest coefficients appear in models with stronger IQ, which suggests that TFP gains are more effective when institutions are sound.

Inflation shows a positive and statistically significant coefficient across all models, though the magnitudes are very small (0.001 to 0.050). While inflation is typically considered harmful for economic growth beyond a certain threshold, mild inflation in developing economies can indicate healthy demand or currency stability, possibly explaining this result. Also, some models (e.g., REQ and ROL) show stronger positive coefficients (up to 0.050), suggesting that inflation’s impact may be nonlinear or context-dependent, supporting findings from Barro [66] and Dornbusch and Fischer [67], who note that moderate inflation can be tolerable or even growth-neutral when macroeconomic management is credible.

The coefficient on government size is consistently negative and highly significant in all columns (from −0.052 to −0.631). This implies that increased public consumption may crowd out private investment or reflect inefficient spending, particularly in countries with weaker institutions. These findings resonate with Barro’s [68] view that while productive government spending (e.g., on infrastructure) can enhance economic growth, excessive or unproductive public expenditures reduce efficiency and can increase fiscal burdens.

Exports have a positive and statistically significant impact across all models, with coefficients ranging from 0.016 to 0.035. This affirms the classical view that openness to trade fosters economic growth through improved resource allocation, scale economies, and technology spillovers (e.g., Grossman and Helpman [69]). Export-led growth is particularly important for developing economies, and the consistent significance of this variable reinforces the role of external competitiveness in fostering sustained output growth [70].

The coefficient on urbanization is mostly negative and statistically significant, with a few exceptions. For instance, in models using GEF (column 7), urbanization has an extremely large negative coefficient (−2.396, p < 0.01), whereas in some cases (e.g., COC), it becomes statistically insignificant or even positive. These results suggest that urbanization alone does not guarantee growth, especially if not accompanied by effective urban planning, infrastructure development, or job creation. In poorly governed or rapidly urbanizing countries, urbanization may lead to congestion, slums, or unproductive agglomeration effects, reducing their growth potential.

In addition, in System GMM, instruments are lagged values of endogenous variables used to address potential endogeneity issues (e.g., simultaneity, omitted variables, measurement error). The number of instruments reported (e.g., 101 to 114 in your table) reflects the count of these instrumental variables used in the estimation. A larger number of instruments can improve efficiency but may also lead to instrument proliferation, which risks overfitting the endogenous variables and weakening the power of specification tests. It is important to balance having enough instruments to address endogeneity without overfitting.

The Sargan test checks the validity of the instruments by testing the null hypothesis that the instruments are exogenous (i.e., uncorrelated with the error term). A high p-value (close to 1), as seen from our results (0.901 to 1.000), indicates failure to reject the null hypothesis, meaning that the instruments are valid and not correlated with the error term.

The Arellano–Bond test for AR(2) examines whether the differenced error terms exhibit autocorrelation of order 2. The null hypothesis is that there is no second-order autocorrelation in the differenced residuals. A p-value greater than 0.05 indicates failure to reject the null, confirming that the model residuals do not have problematic autocorrelation and the instruments are likely valid. Our results show p-values ranging from about 0.249 to 0.877, well above 0.05, indicating no evidence of AR(2).

5. Robustness Analysis

To further assess the sensitivity of our results to data or econometric parameters, we provide robustness tests. First, we include additional factors that might serve as proxies for IQ; we substitute WGI data with a variable from the International Country Risk Guide dataset. Second, we employ nonlinear PTR to substantiate the computation of the threshold in the baseline results and discussion section. Third, following Tchamyou and Asongu [61] and Hansen [62], we also employ ETIR to see whether the results hold true using these three alternative regression methods.

5.1. Robustness Test 1: Alternate Dataset

To ensure the robustness of our baseline findings, we employ an alternative proxy for IQ using data from the ICRG dataset. Due to data availability constraints, the sample size in this robustness check decreases to 102 countries. The ICRG dataset includes six key variables: Bureaucracy Quality (BCQ), Government Stability (GVS), Investment Profile (INP), Democratic Accountability (DAA), Law and Order (LOR), and Corruption (COR). Each variable is originally scored on different scales; for example, BCQ ranges from 0 to 4, GVS and INP from 0 to 12, and DAA, LOR, and COR from 0 to 6. To maintain consistency and comparability, we transform and rescale all these indicators into a unified index ranging from 0 to 10, where higher values represent better IQ.

The results of the two-step dynamic System GMM estimator using the ICRG dataset are presented in Table 5. These findings are largely consistent with our baseline results, providing additional support for the negative impact of debt on economic growth and the positive moderating role of IQ. Specifically, the coefficients for the interaction term ) are significantly positive across all six dimensions of IQ, confirming that better IQ mitigates the adverse effects of debt on economic growth.

Table 5.

Robustness Test 1: Alternate dataset.

Moreover, the neconomic growthative and significant coefficients on debt reaffirm the detrimental impact of high debt levels on economic performance, aligning with theories on debt overhang and fiscal sustainability. The positive coefficients of highlight the crucial role of institutional frameworks in fostering economic growth, consistent with institutional economics theories emphasizing governance quality as a growth catalyst.

Control variables such as TFP, Inflaion, Government size, Exports, and Urbanization display expected signs and significance levels, underscoring the robustness of the model.

Diagnostic tests also support the validity of our estimation strategy. The Sargan test p-values close to 1 indicate that the instruments are valid and not correlated with the error term. Additionally, the Arellano–Bond AR(2) test results show no evidence of serial correlation, confirming the reliability of the panel model.

In summary, the robustness checks with the ICRG indicators reinforce our baseline conclusions, validating the critical moderating role of IQ in the public debt—economic growth nexus. The results of the marginal effect of debt on IQ using the ICRG dataset are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Marginal effect (ICRG dataset).

5.2. Robustness Test 2: Using Panel Threshold Regression

In accordance with the insights of Wang [63], the system GMM regressions are replicated using the PTR model. In order to use the PTR estimate method, the sample of 115 nations is reduced to 92 countries that demonstrate a balanced panel dataset. Considering 95% confidence intervals, we obtain thresholds of measures of IQ such that VAA, PSV, GEF, REQ, ROL and COC of 7.621 [7.617, 7.629], 7.054 [7.045, 7.058], 7.837 [7.811, 7.870], 7.308 [7.286, 7.314], 7.475 [7.463, 7.485], and 7.733 [7.706, 7.764], respectively, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Robustness Test 2: Panel Threshold Regression.

It is important to note that the thresholds are computed for the debt in the main results and discussion section using Equation (11). Based on the results of the linear analysis, the PTR model of Hansen [49] is applied to the baseline specifications model to substantiate our basic threshold results. The LR test of the threshold effect suggested by [62,71,72] is employed to determine the existence of a threshold. Like our fundamental results, debt coefficients are negative and statistically significant. Our major results are supported by the positive coefficients of interaction variables between debt and all six IQ indicators. The finding suggests that states with poor institutions have more debt.

Thus, debt has little influence on low-quality institutions and even hurts long-term economic growth. Using bootstrap replications, the LR test strongly rejects the no-threshold null hypothesis from columns 2 to 12. The threshold value 7.621 is the turning point for voice and accountability. PSV, GEF, REQ, ROL, and COC also have IQ levels of 7.054, 7.837, 7.308, 7.478, and 7.733; after that, debt impacts positively on economic growth.

5.3. Robustness Test 3: Using Extended Threshold Interactive Regression

Following some studies that used this regression method [73,74], we provide the findings of an alternative to our fundamental computing approach, extended threshold regression analysis, using an approach to make the basic findings more robust [75]. Table 8 summarizes the findings. The net effects from the unconditional and conditional or marginal impacts of all IQ factors are evaluated to determine the overall importance of the rising effect of IQ variables. For example, the net impact on economic growth from the relevant voice and accountability in moderating the effect of debt on economic growth, or the net effect, in the second column is 0.285 [0.196 × 5.248 + (−0.747)], where −0.747 is the unconditional effect of debt; 0.196 is the conditional effect of the interaction between debt and VAA.

Table 8.

Robustness Test 3: Extended Threshold Interactive Regression.

Likewise, we calculated the values of the net effect from all even columns, which are 0.110, 0.128, 0.180, 0.140, and 0.189, respectively, for columns 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12. To make economic sense and have policy significance, the threshold should be set within the statistical ranges, which means that this should be between the minimum and maximum values. This analysis’s threshold values are all inside the statistical range, demonstrating the consistency of our findings.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Concluding Remarks

This study empirically examines how IQ moderates the relationship between public debt and economic growth in a panel of 115 countries over the period 1996–2021. Drawing on institutional measures from both the WGI and ICRG, this analysis applies a dynamic system GMM estimator and confirms that public debt exerts a significant negative impact on economic growth. However, this effect is conditional on the strength of a country’s institutional framework. Specifically, higher levels of IQ reflected in indicators significantly attenuate the adverse effects of public debt.

The results are consistent across multiple robustness checks, including alternative institutional datasets and threshold regression techniques, confirming the nonlinear and institution-dependent nature of the debt–growth nexus. These findings reinforce the theoretical proposition that institutions shape the efficiency and credibility of fiscal policy implementation. In contexts where institutions are weak, public borrowing tends to be misallocated or poorly managed, thereby impeding growth. Conversely, stronger institutional environments appear to transform debt into a more productive tool of economic development.

Overall, this study underscores the importance of IQ not only as a direct driver of growth but also as a critical conditioning factor in determining the macroeconomic consequences of fiscal policy. This insight is particularly relevant for countries facing rising debt burdens amid developmental challenges. Strengthening institutional frameworks should, thus, be seen as integral to achieving both debt sustainability and long-term economic resilience.

6.2. Research Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into the moderating role of IQ in the debt–growth relationship, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the IQ indicators used from both the WGI and ICRG datasets are perception-based and may be subject to measurement error or observer bias, which could affect the precision of the estimated effects. Second, this analysis is conducted at the macro (national) level, which may mask substantial cross-country heterogeneity in institutional dynamics, debt structures, and development stages. As such, the results represent average effects and may not fully capture country-specific or regional variations. Third, although the use of the dynamic system GMM estimator addresses endogeneity concerns, the technique is sensitive to instrument proliferation and relies on assumptions regarding the validity of internal instruments that may not hold uniformly across all contexts.

Moreover, while the panel structure allows for dynamic modeling, it may not adequately account for unobserved time-varying heterogeneity or structural breaks over the long sample period. IQ itself may also evolve slowly, limiting the capacity of the model to capture the deeper, long-run effects of institutional reform. Lastly, this study does not incorporate informal institutional factors or political economy dimensions, such as regime type, elite capture, or electoral volatility, which may further condition how public debt affects growth. These limitations suggest caution in generalizing the findings and point to areas for future empirical refinement.

6.3. Future Research Directions

In light of the findings and limitations of this study, several important directions emerge for future research. First, there is a need to move beyond cross-country averages by conducting country-specific or regional studies that account for the heterogeneity in institutional arrangements, debt structures, and development trajectories. Disaggregated analyses can better capture context-specific institutional dynamics and produce more targeted policy insights. Second, future research should explore the role of informal institutions and political economy factors, such as elite influence, electoral cycles, and regime durability, which may critically shape the relationship between public debt and growth but remain unaccounted for in macro-panel datasets.

From a methodological perspective, future studies could benefit from incorporating nonlinear and time-varying techniques, such as threshold vector autoregression, time-varying parameter models, or Markov-switching regressions, to more accurately reflect the evolving impact of institutions over time. Additionally, instrumental variable strategies using external instruments or quasi-experimental designs (e.g., difference-in-differences, synthetic control methods) could provide more robust causal inference regarding the institutional moderation effect. Scholars may also consider using high-frequency panel data or subnational data to capture within-country variations in IQ quality and public finance outcomes.

Moreover, the integration of climate-related fiscal risk, external versus domestic debt composition, and sovereign risk indicators into future frameworks would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how institutions moderate/mediate the growth impact of debt under changing global and financial conditions. Finally, applying machine learning techniques for variable selection or classification of institutional regimes could further enhance empirical precision and reveal new patterns in the debt–institution–growth nexus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S. and D.S.; methodology, H.S.; software, D.S.; vali-dation, D.S.; formal analysis, H.S. and M.R.; investigation, D.S.; resources, D.S.; data curation, M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, M.R.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the “Research on short video strategies for pan-China environmental protection agricultural machinery in the Indonesian market”, Project Fund Number: 2506045103 (Ministry of Education Industry-University Cooperation and Collaboration Project).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this research is publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of Countries.

Table A1.

List of Countries.

| Angola | Equatorial Guinea | Lao PDR | Russian Federation |

| Argentina | Egypt, Arab Rep. | Latvia | Rwanda |

| Armenia | Estonia | Lesotho | Saudi Arabia |

| Australia | Eswatini | Lithuania | Senegal |

| Austria | Fiji | Luxembourg | Serbia |

| Bahrain | Finland | Malaysia | Sierra Leone |

| Barbados | France | Malta | Singapore |

| Belgium | Gabon | Mauritania | Slovak Republic |

| Benin | Germany | Mauritius | Slovenia |

| Bolivia | Greece | Mexico | South Africa |

| Botswana | Guatemala | Moldova | Spain |

| Brazil | Honduras | Mongolia | Sri Lanka |

| Bulgaria | Hong Kong SAR, China | Morocco | Sudan |

| Burkina Faso | Hungary | Mozambique | Sweden |

| Burundi | Iceland | Namibia | Switzerland |

| Cameroon | India | Netherlands | Tajikistan |

| Canada | Indonesia | New Zealand | Tanzania |

| Central African Republic | Iran, Islamic Rep. | Nicaragua | Thailand |

| Chile | Iraq | Niger | Togo |

| China | Ireland | Nigeria | Tunisia |

| Colombia | Italy | Norway | Turkiye |

| Costa Rica | Jamaica | Panama | Ukraine |

| Cote d’Ivoire | Japan | Paraguay | United Kingdom |

| Croatia | Jordan | Peru | United States |

| Cyprus | Kazakhstan | Philippines | Uruguay |

| Czech Republic | Kenya | Poland | Venezuela, RB |

| Denmark | Korea, Rep. | Portugal | Zambia |

| Dominican Republic | Kuwait | Qatar | Zimbabwe |

| Ecuador | Kyrgyz Republic | Romania |

Notes: Barbados, Benin, Burundi, Central African Republic, Eswatini, Fiji, Kyrgyz Republic, Lao PDR, Lesotho, Mauritania, Mauritius, Rwanda, and Tajikistan are missing in the analysis when using dataset of ICRG.

References

- Schclarek, A. Consumption and Keynesian Fiscal Policy; Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo): Munich, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Izák, V. The Welfare state and economic growth. Prague Econ. Pap. 2011, 20, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplý, P.; Tripe, D. The TT index as an indicator of macroeconomic vulnerability of EU new member states. Ekon. Cas. 2015, 63, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Masuch, K.; Moshammer, E.; Pierluigi, B. Institutions, public debt and growth in Europe. Public Sect. Econ. 2017, 41, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ha, Y.; Kim, S. Public debt, corruption and sustainable economic growth. Sustainability 2017, 9, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarek, B.A.; Ahmed, Z. Governance and public debt accumulation: Quantitative analysis in MENA countries. Econ. Anal. Policy 2017, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.H.; Azman-Saini, W. Institutional quality, governance, and financial development. Econ. Gov. 2012, 13, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingales, L. More on Finance and Growth: More Finance, More Growth? Commentary. Fed. Reserve Bank St. Louis Rev. 2003, 85, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. Governance Matters IV: Governance Indicators For 1996–2004; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 6th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, E.C.; Wang, H.; Ai, C. Computing interaction effects and standard errors in logit and probit models. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2004, 4, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. The Wealth of Nations [1776]; J. M. Dent & Co.: London, UK, 1937; Volume 11937. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, J.S. Principles of Political Economy: Abridged with Critical, Bibliographical and Explanatory Notes and a Sketch of the History of Political Economy; Library of Alexandria: Alexandria, Egypt, 1885; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo, D. On the Principles of Political Economy; J. Murray: London, UK, 1821. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, D.P.; Rath, B.N. Public debt and economic growth in India: A reassessment. Econ. Anal. Policy 2014, 44, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, Í.; Brochier, L.; Freitas, F. Debt hierarchy: Autonomous demand composition, growth and indebtedness in a supermultiplier model. Econ. Model. 2023, 126, 106369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, M.; HongXing, Y.; Abbas, Q.; Fatima, S.; Hussain, R.Y. Role of institutional quality in debt-growth relationship in Pakistan: An econometric inquiry. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, I.; Al_Kasasbeh, O.; Alzghoul, A.; Alsheikh, G. The Influence of Public Debt on Economic Growth: A Review of Literature. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2023, 8, e01772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardoni, C. The public debt and the Ricardian equivalence: Some critical remarks. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2021, 58, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchener, K.J.; Trebesch, C. Sovereign Debt in the 21st Century; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beirne, J.; Renzhi, N.; Volz, U. Bracing for the typhoon: Climate change and sovereign risk in Southeast Asia. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yared, P. Rising Government debt: Causes and solutions for a decades-old trend. J. Econ. Perspect. 2019, 33, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Ghate, C. Debt decomposition and the role of inflation: A security level analysis for India. Econ. Model. 2022, 113, 105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, J.H. Determinacy and identification with taylor rules. J. Politi Econ. 2011, 119, 565–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, J. Merchants of Debt at the extreme overnight: Re-considering monetary theories via rollover-induced interbank frictions. Rev. Politi Econ. 2023, 37, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, U.; Madaleno, M.; Dagar, V.; Ghosh, S.; Doğan, B. Exploring the role of export product quality and economic complexity for economic progress of developed economies: Does institutional quality matter? Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2022, 62, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.P.; Pradhan, K.C. Institutional quality and economic performance in South Asia. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, H.K.; Gakpa, L.-L. Do economic growth and institutional quality reduce poverty and inequality in West Africa? J. Policy Model. 2022, 44, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struckell, E.; Ojha, D.; Patel, P.C.; Dhir, A. Strategic choice in times of stagnant growth and uncertainty: An institutional theory and organizational change perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccaro, L.; Blyth, M.; Pontusson, J. Diminishing Returns: The New Politics of Growth and Stagnation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zakari, A.; Khan, I. Boosting economic growth through energy in Africa: The role of Chinese investment and institutional quality. J. Chin. Econ. Bus. Stud. 2022, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, C.M. How does the impact of foreign direct investment on institutional quality depend on the underground economy? J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 12, 554–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Globerman, S.; Shapiro, D. Global foreign direct investment flows: The role of governance infrastructure. World Dev. 2002, 30, 1899–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, F.N.; Gan, C. Foreign Direct Investment Inflows and Governance Nexus: Evidence from the United States, China, and Singapore. Rev. Pac. Basin Financ. Mark. Policies 2022, 25, 2250030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, C.M.; Rogoff, K.S. Growth in a Time of Debt. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, U.; Presbitero, A.F. Public debt and economic growth: Is there a causal effect? J. Macroecon. 2014, 41, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.; Said, R.; Ismail, N.W.; Mazland, N.S. Public debt, institutional quality and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Inst. Econ. 2019, 11, 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Iyoboyi, M.; Badiru, A. The Influence of Economic Institutions in the Debt-Growth Nexus: Evidence from Nigeria. Open Econ. Rev. 2025, 36, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemoe, L.; Lartey, E.K. Public debt, institutional quality and growth in sub-Saharan Africa: A threshold analysis. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2022, 36, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Junqing, L.; Ramzan, M.; Fatima, S. Role of Governance in Debt-Growth Relationship: Evidence from Panel Data Estimations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashogbon, F.O.; Onakoya, A.B.; Obiakor, R.T.; Lawal, E.S. Public debt, institutional quality and economic growth: Evidence from Nigeria. J. Econ. Allied Res. 2023, 8, 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- El-Naser, A. Public debt, institutional quality and economic growth in eu countries in the aftermath of COVID-19 and war-induced crisis. J. Smart Econ. Growth 2023, 8, 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Oppong, C.; Atchulo, A.S.; Oman, S.F. Public debt and economic growth nexus in sub-saharan Africa: Does institutional quality matter? Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2023, 37, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, D. Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models of fluctuations. Adv. Macroecon. 2012, 4, 312–364. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, C.D.; Summers, L.H. Consumption Growth Parallels Income Growth: Some New Evidence; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, P. Overlapping families of infinitely-lived agents. J. Public Econ. 1989, 38, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedák, I.; Dombi, Á. A Closed-Form Solution for Determining the Burden of Public Debt in Neoclassical Growth Models. Bull. Econ. Research. Bull. Econ. Res. 2018, 70, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala-I-Martin, X.; Doppelhofer, G.; Miller, R.I. Determinants of long-term growth: A bayesian averaging of classical estimates (BACE) approach. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 813–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattillo, C.A.; Poirson, H.; Ricci, L.A. External Debt and Growth; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, R.T. The effects of debt burden on economic growth in heavily indebted developing nations. J. Econ. Dev. 1993, 18, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Abbas, Q.; Ramzan, M.; Fatima, S. Impact of Domestic Investment on Domestic Credit Level. Does Institutional Quality Matter? J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econ. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-S.; Chen, H.-Y.; Chang, C.-C.; Yang, S.-L. How do sovereign credit rating changes affect private investment? J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 4820–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, M.; Sheng, B.; Shahbaz, M.; Song, J.; Jiao, Z. Impact of trade openness on GDP growth: Does TFP matter? J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2019, 28, 960–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargan, J.D. The Estimation of economic relationships using instrumental variables. Econometrica 1958, 26, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. A Note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2009, 71, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windmeijer, F. A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. J. Econ. 2005, 126, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchamyou, V.S.; Asongu, S.A.; Odhiambo, N.M. The role of ICT in modulating the effect of education and lifelong learning on income inequality and economic growth in Africa. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2019, 31, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J. Econom. 1999, 93, 345–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Fixed-effect panel threshold model using stata. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2015, 15, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous technological change. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98 Pt 2, S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, P.; Aghion, P. Capital accumulation and innovation as complementary factors in long-run growth. J. Econ. Growth 1998, 3, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J. Inflation and Economic Growth; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch, R.; Fischer, S. Moderate inflation. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1993, 7, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. Government spending in a simple model of endogenous growth. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98 Pt 2, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E. Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1991, 35, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Peng, D.; Ni, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Z. Trade openness and economic growth quality of China: Empirical analysis using ARDL model. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Sample splitting and threshold estimation. Econometrica 2000, 68, 575–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.E. Inference when a nuisance parameter is not identified under the null hypothesis. Econometrica 1996, 64, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S.A.; Odhiambo, N.M. Basic formal education quality, information technology, and inclusive human development in sub-Saharan Africa. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchamyou, V.S. The role of information sharing in modulating the effect of financial access on inequality. J. Afr. Bus. 2019, 20, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambor, T.; Clark, W.R.; Golder, M. Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Anal. 2006, 14, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).