Abstract

The construction of child-friendly cities is important for social and economic development. Based on the two-dimensional analysis framework of “Policy Tools–Policy Elements”, this study uses NVIVO 15 qualitative analysis software to code and quantitatively analyze China’s current child-friendly city construction policies. This study examines the formulation strategies and operational characteristics of policy texts on building child-friendly cities in China. The research shows that there are structural imbalances in current policies on child-friendly city construction in China, with too many supply-oriented policy tools and insufficient application of environmental policy and demand-oriented policy tools. The mix of policy instruments is poorly structured, with insufficient attention to children’s rights and social policies and a lack of monitoring and evaluation of policy performance. In the future, China’s children’s urban construction policy should strengthen the balance between the design of policy structures, optimize the structure of policy tools, strengthen the design and protection of laws and policies of children’s rights, and establish a monitoring and evaluation system of policy performance.

1. Introduction

In 1996, the concept of a “child-friendly city” was first proposed at the Second United Nations Conference on Human Settlements. The fundamental needs of children should be incorporated into urban planning [1]. In the same year, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) put forward the “Growing in the City” initiative to assess the urban environment from the perspective of children. Emphasizing the public participation of children [2]. In 2002, a special session of the United Nations on children identified 10 principles and goals to “build a world fit for children” [3]. In 2004, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) issued a framework for action on child-friendly cities [4]. This study proposes 12 rights related to children’s well-being in urban construction. Subsequently, relevant international organizations issued a series of initiatives and action plans to build child-friendly cities (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Initiatives and action plans related to child-friendly cities of the United Nations.

UNICEF believes that a child-friendly city is a wise government that fully implements the Convention on the Rights of the Child in all aspects of the city. As a result, children should have political priority in public affairs, whether in large cities, medium cities, small cities, or communities. Incorporating children into decision-making systems [5]. It can be seen that the focus of the construction of child-friendly cities is to guide the government in formulating a series of action plans to make the urban environment more suitable for the birth and growth of children.

The initiative to build child-friendly cities has received a global response. Currently, more than 3000 cities and communities in developed countries such as Germany, Finland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, and Japan, as well as developing countries such as Vietnam, Brazil, and Belarus, have obtained child-friendly certification from the United Nations Children’s Fund [6]. In September 2021, the China Development and Reform Commission jointly issued the Guidelines for Promoting the Construction of Child-Friendly Cities with 22 departments. It proposes that we should adhere to the priority of children’s development, proceed from the perspective of children, and take children’s needs as the guide. Toward the urban development goal of enabling children to grow up better through policy-friendly, public service-friendly, rights protection-friendly, growth space-friendly, and development environment-friendly measures. Under the guidance of this policy, Shenzhen, Changsha, and other major cities have further deepened the construction of child-friendly cities [7]. Many other cities followed suit. At the new starting point for urban growth, this document explores the comprehensive promotion mechanism for the construction of child-friendly cities in China from a design perspective at the highest level. This is not only of great significance for the high-quality development of Chinese cities. It is also of great significance to explore the construction of child-friendly cities with Chinese characteristics [4].

Research on the construction of child-friendly cities has attracted considerable academic circles. At present, relevant research focuses on the construction of child-friendly city spaces [8,9], the enlightenment of construction experiences at home and abroad [10,11], and the policy of a child-friendly city [12]. The relationship between urban development and children’s health and well-being encompasses urban planning, geography, public health, sociology, psychology, and other fields [13,14,15]. The study also links the construction of child-friendly cities with the issue of governance and theoretically interprets the construction of child-friendly cities [16]; a typological analysis of child-friendly communities [17]; and the issues of building and maintaining child-friendly communities are discussed in depth [18]. In addition, there are also researchers from the perspective of evolutionary logic and the meaning of the concept of child-friendly and the construction of a mechanism of participation of children, exploring the logic of building a child-friendly city [19,20].

This paper uses policy tools to analyze current policies on the construction of child-friendly cities, as described by central and local governments at all levels. Qualitative and quantitative analysis methods were used to investigate the shortcomings of the current child-friendly city construction policy. Based on this, a feasible path is proposed to provide theoretical insights and practical guidance for the future optimization of child-friendly cities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Materials

With the help of the Peking University legal database and the websites of local governments at all levels in China, the file name “Child-Friendly City” was used for the search. The retrieval time was from September 2021 to February 2025.

The following criteria are to be considered to determine the inclusion of a policy in the aforementioned list: (1) Policies concerning the construction of child-friendly cities must be issued by central and local governments at all levels. (2) The title of the policy must contain the words “child-friendly city construction”. (3) Types of policies are normative policy documents such as laws and regulations, plans, action plans, notices, standards, and rules.

The policy exclusion criteria are as follows: (i) administrative notices, forwarding, notification, approval, letters, etc.; (ii) documents with repetitive content and low relevance; and (iii) policy documents that have been abolished or replaced by amendments.

To prevent bias in the retrieval of policy texts, the research team assigned two members to perform the retrieval based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. When the retrieval results were inconsistent, the researchers engaged in extensive discussions and finally determined which policy texts to include or exclude.

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above, the statistics show that 51 child-friendly city construction plans or action plans were successively issued by the central and local governments of China (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical table of policy documents on the construction of child-friendly cities in China.

2.2. Analytical Framework

After reviewing the sources of material for this study, we established the theoretical analytical framework for this research.

In recent years, the analysis of policy texts using policy tools as core tools has been widely used in the field of public policy. The use of policy tools plays a guiding role in the development of policy objectives. The policy elements constitute the basic content of a policy. Through the setting of policy elements, we can grasp the key points and objectives of policy implementation [21,22].

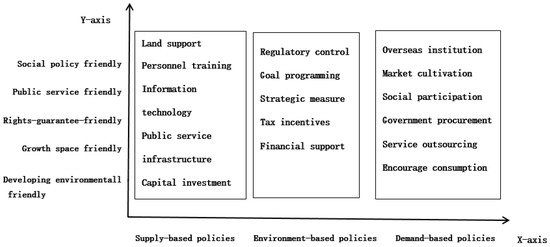

This paper adopts Rothwell and Zegveld’s classification of types of policy instruments [23]. The framework for the analysis of the policy text is constructed from two dimensions: support for children and elements of urban construction. There are three types of policy instruments: environmental, supply, and demand policies.

This paper says that a way to classify policy tools based on supply, environment, and demand is a good way to conduct policy research to make cities better for children. On the one hand, this classification method is suitable for different types of policies. It is widely used in science, technology, innovation, and public management policies. The policy framework for building child-friendly cities essentially involves the use of science and technological innovation to advance such initiatives, thus exhibiting strong technological innovation characteristics. However, in terms of the suitability of the research objectives, this classification method uses the different ways in which policy tools influence policy objectives as its classification criteria, thereby helping this study identify the logical mechanisms through which policy tools impact policy objectives.

According to current academic research and the focus on international and domestic policy regulation, the five elements of child-friendly city construction are social policy, public service, rights protection, growth space, and the development of an environmentally friendly environment. The analysis framework of this paper is constructed from two aspects: policy tools and policy elements. The policy tools are considered as the X dimension, and the five elements of the child-friendly city construction are the Y dimension, constructing a two-dimensional analysis framework of China’s child-friendly city construction policy (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A two-dimensional analytical framework for constructing child-friendly cities in China.

2.2.1. Dimension X-Policy Instruments

The means or methods used by the government to achieve policy objectives are policy tools. Rothwell and Zegveld divided policy instruments into three types: environmental, supply, and demand, which have been widely used. The proposed classification tool has a clear definition and strong operability [24]. Therefore, this tool was selected as the X-axis in the two-dimensional analysis framework. Supply-oriented policy tools are mainly embodied in the state’s support for constructing child-friendly cities through the acquisition of funds, talent, and technology. The policy thrust of the construction of child-friendly cities and the role of environmental policy tools is to provide a favorable environment for constructing such cities. Including target planning, regulation, financial support, etc. Demand-oriented policy tools are the tools of choice for policy to promote the construction of child-friendly cities. Through market cultivation, government purchases, service outsourcing, and other means, the potential for child-friendly city construction can be stimulated. See Table 3 for the classification and meaning of specific policy instruments.

Table 3.

Classification and meaning of policy tools for child-friendly city construction in China.

2.2.2. Y-Dimensional Policy Element

UNICEF was founded on children’s rights and sustainable urban development. A five-benefit framework can be used to define child-friendly cities. First, health: A clean city can maintain children’s behavior patterns so that they can grow up healthy. Second, safety: environmental safety can lead to the existence of various risks for children. Third, citizenship: inclusion of members of society and the right to participation by children. Fourth, the environment: a sustainable urban environment guides children in their environmental protection and promotes the concept of greenness. The fifth pillar is prosperity: citizens who live a decent life can receive education and afford urban services, support the improvement of children’s life skills, and open the job market to them [25].

However, some rich experience has been accumulated in the construction of child-friendly cities both in China and abroad. Based on practical experience, the construction of friendly cities in China has led to the design of five policy agendas. It also constitutes the five elements of China’s friendly city construction policy [26]: First, it promotes social policy friendliness, which requires setting up an urban policy agenda. The allocation of public resources and investment in financial funds should consider children’s needs and listen to their voices. Children can effectively participate in public affairs. Second, the public service was friendly. Public services for children, such as education, health and sanitation, water and sanitation, housing, culture, recreation, and leisure, will be addressed on the urban agenda. Third, protection and friendship of rights, improving the child welfare system, and making every effort to help children in distress; fourth, growing friendly to space, improving the quality of urban space, and improving the efficiency of public services; and fifth, developing a friendly environment, advocating for a civilized home and school atmosphere, and ensuring social security. This paper adopts the above five policy agendas (or five elements) as the Y dimension. This study examines the coverage of China’s child-friendly city construction policy.

The combination of policy tools and policy elements to build a child-friendly city constitutes a two-dimensional analysis of the child-friendly city construction policy framework.

2.3. Encoding Policy Texts

After systematically sorting out the sources of policy texts and establishing a theoretical framework for research, considering the qualitative and quantitative analysis of policy text content, it is necessary to use relevant analysis software to code the content of policy texts.

Vivo is a text content analysis software. Content analysis is a scientific method used to determine the essence of a phenomenon [27]. The proposed method can reproduce the content of the policy text and infer the results simultaneously. This article collected 51 policy texts on the construction of child-friendly cities in China according to “Policy Number-1” through the following: Level 1 Title—Level 2 Title—Encode. On the premise of ensuring the integrity of the expression of meaning, the smallest element describing the object of measurement research in the content analysis method is determined according to the principle of “non-subdivision”. When a paragraph expresses a layer of meaning, the paragraph is the unit of analysis; when a paragraph expresses multiple meanings and can be subdivided into multiple sentences, the sentence is taken as the unit.

The ambiguity of word meanings, category definitions, and other coding rules in the analysis of policy text content often leads to issues with the reliability of coding. In reliability testing, our research team assigned two coders to evaluate the same text using the same analytical dimensions, achieving a consistency rate of 0.91. According to the standards for reliability assessment, the reliability of the coding was considered satisfactory. After validating the reliability of the coding, the two coders discussed and revised the areas where inconsistencies in the coding were identified.

After excluding content not related to the construction of child-friendly cities in the policy text, 1416 valid codes were obtained. In this way, the content of the policy text can be classified and coded (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Text coding of China’s child-friendly city construction policy.

3. Results

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis of Policy Documents on the Construction of Child-Friendly Cities in China

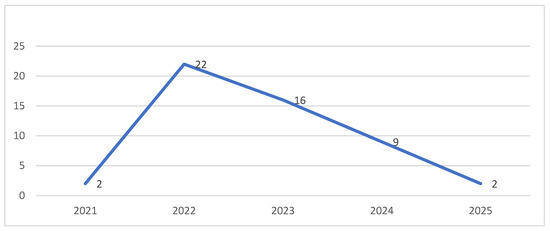

3.1.1. Analysis of Publication Dates

Time-series analysis is a systematic approach that uses time as an order to reveal patterns of change in phenomena and predict their future trends. China has issued 51 policy documents on the construction of child-friendly cities, with the issuance period spanning January 2021 to February 2025 (see Figure 2). In 2021 and 2025, there were two documents each, with the highest number at 22 in 2022, followed by 16 in 2023, and only nine in 2024. This is because after the National Development and Reform Commission and 13 other departments issued Guided Opinions on Promoting the Construction of Child-Friendly Cities in 2021, it had a driving effect on local governments at all levels. Under the strengthened enforcement capacity of local governments, local governments at all levels in China have successively issued relevant policies on the construction of child-friendly cities.

Figure 2.

Distribution of release dates for policy documents on the construction of child-friendly cities in China.

3.1.2. Frequency Analysis of Policy Documents

China’s policy implementation force can be divided into laws, administrative regulations, departmental rules, departmental normative documents, local normative documents, and other forms according to the level of effectiveness. Of the 51 policy texts issued, only one was a normative document formulated by the State Council and its relevant departments, and 50 local normative documents were formulated by the local People’s Congress and local governments of the People’s Republic of China. The policy texts include seven local ordinances, 25 regulations created by the local government of the People’s Republic of China, and 19 departmental normative documents created by the local government of the People’s Republic of China and their relevant departments. The local People’s Congress and the government of the People’s Republic of China have used legal documents to promote the development of child-friendly cities.

3.1.3. Frequency Analysis of Issuing Agencies

Of the 51 child-friendly city-building policies, relevant bodies include the National Development and Reform Commission, the All-China Women’s Federation, local people’s congresses and their standing committees, the local government of the People’s Republic of China at all levels, and local government development and reform commissions. There is only one central policy document, and the other 50 are local policy documents that promote child-friendly city construction. There were 16 joint documents issued by departments and 35 policy documents issued by a single entity, respectively.

3.2. Results of the X-Dimension Analysis of the Policy Instrument Dimension

In 51 policy texts on child-friendly city construction, there are 1416 reference points on the dimension of policy tools. There are differences in the use of the three types of policy instruments, among which the supply policy instruments account for the highest proportion (58.4%). The proportion of environmental policy tools is the second highest (27.8%), and the proportion of demand policy tools is the lowest (13.8%).

At the same time, the analysis of the proportion of the 17 policy sub-tools shows that the use of the various policy sub-tools is also emphasized. Among the 827 analysis units of supply policy tools, public service is 550, accounting for the highest proportion, reaching 66.5%. Second, there are 135 infrastructures, which account for 16.3% of the infrastructure, and the least used of the personnel training is 20, which accounts for only 2.4% of the infrastructure. The most frequently used sub-tools are strategic measures, accounting for 43.3% of environmental policy tools. The second-highest category is target planning and regulation, accounting for 22.9% and 16.5%, respectively, and the lowest category is tax incentives and financial support at 9% and 8%, respectively. Among demand-oriented policy tools, social participation is the most widely used, accounting for 45.9%, followed by market cultivation at 20.4%. The lowest is encouraging consumption, accounting for only 6% (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of basic policy tools for China’s child-friendly city construction policies.

3.3. Y-Dimensional Analysis of the Dimension of the Policy Element

Based on the unit coding table for the content analysis of the policy for the construction of child-friendly cities, the distribution of the elements of China’s child-friendly city construction policy is obtained by classification, induction, and statistics. Among the 1616 units of policy content analysis, five elements were included in the construction of child-friendly cities. Social policy-friendly has 217 units, accounting for 15.3%; public service-friendly has 316 units, accounting for 22.3%; there are 218 units of rights protection friendship, accounting for 15.3%; there are 364 units of growth space friendship, accounting for 25.7%; and there are 301 environmentally friendly units, accounting for 21.3%. China pays more attention to five specific areas to develop child-friendly cities. The proportion of growth space friendliness is slightly higher than that of the other four specific areas.

3.4. XY Dimensional Analysis Results of Policy Tools and Elements

According to Table 6, there are three types of policy tools, seventeen types of policy sub-tools, and five areas of child-friendly city construction. Different policy tools are used, but each has its emphasis.

Table 6.

Results of the two-dimensional X-Y analysis of the text of China’s child-friendly city construction policy.

Of the 827 analysis units on supply policy tools, 95 analysis units on social policy friendliness account for 11.5%. Public service friendliness has 160 units, representing 19.3% of the total. Rights protection friendliness has 132 analysis units, accounting for 16%. There are 231 analysis units for growth-space friendliness (27.9%). There are 209 analysis units for development environment friendliness (25.3%). Among the supply-side policy instruments, the construction of policies of growth-space friendliness and development environment friendliness is more friendly than social policy friendliness, public service friendliness, and protection of rights friendliness. They have a clear advantage.

Of the 393 analysis units in the field of environmental policy instruments, 65 were in socially friendly areas, representing 16.5%. A total of 104 analysis units were in public service friendliness, representing 26.5%. A total of 72 analysis units were in the rights-protection-friendly mode (18.3%), and 87 analysis units were in the growth-space-friendliness mode, accounting for 22.1%. Furthermore, 65 analysis units were on development environment friendliness, representing 16.5%. Therefore, in the field of environmental policy, we pay more attention to improving the service quality and growth space of public services. Social policy and environmental friendliness for development have received relatively little attention.

Of the 196 analysis units in the field of demand-oriented policy, 57 are socially policy-friendly, accounting for 29%; public service-friendly has 56 analysis units, accounting for 28.6%. Rights protection-friendly are 4 analysis units, accounting for only 2%; 36 analysis units of growth-space friendliness, accounting for 18.3%; and 27 analysis units of development environment friendliness, accounting for 13.8%. In demand-based policies, children’s rights are not given enough attention. More attention has been paid to the construction of social policy and public service friendliness.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Selection of Policy Instruments Is Often Unbalanced

Whether it is the choice of large policy tool types or the choice of sub-tool types, policy tools are not balanced. Among the three types of policy instruments, supply-oriented policies (58.4%) far exceed the proportion of environmental policies (27.8%) and demand-oriented policies (13.8%). It is even more than the sum of environmental and demand policies. The United Nations proposed the construction of child-friendly cities in 1996. Some countries have successful policies and practical experience and have a long history of construction. Since 2021, China’s policy has been of great importance to the construction of child-friendly cities, which has taken a relatively short time and has insufficient research and practical experience. In the early stages, advocates argued for top-down policy implementation and practice. However, as a long-term policy to build child-friendly cities, this may face the dilemma of policy implementation. It is also difficult to achieve the desired results [28].

In terms of the selection of policy tools, there is an imbalance among the three main types of policy tools, with supply-oriented policies accounting for too large a proportion, while environment-oriented and demand-oriented policies account for too small a proportion, especially demand-oriented policies. This indicates that China is still in the early stages of exploring policy types for developing healthy, child-friendly cities. At the same time, this imbalance is also reflected in the selection of sub-tools for each policy type.

In the sub-tool selection, the construction of child-friendly cities in China overused growth space (25.7%), development environment (21.3%), and public services (22.3%); social policies (15.3%) and protection of rights (15.3%) were not given more attention. This reflects that China has chosen the policy tools for the construction of child-friendly cities.

The construction of child-friendly cities is essentially a movement for children’s rights that legalizes the rights of children as a unique group and a call to develop mechanisms and policies to address or meet their needs. From the perspective of children’s rights, the construction of child-friendly cities covers the following content. Child-friendly cities are required to follow the principle of “children first”, that is, to prioritize and implement all children’s issues in terms of environmental creation, governance mechanisms, and service provision [29]. Second, from the perspective of the content of rights, the construction of child-friendly cities should follow a method of “balancing protection and autonomy”. That is to say, while creating a safe, fair, and friendly social atmosphere and development environment for children, we should attach importance to giving full play to children’s subjective initiative, promoting participation in the entire process of building and developing child-friendly communities [30]. Finally, from the perspective of rights protection, the construction of child-friendly cities is an institutional framework involving the design of top-level child-friendly legal frameworks and policies, capacity building and training, and monitoring and evaluation to fulfill the long-term commitment to the construction of child-friendly cities [31].

4.2. The Setting of Policy Content and Agendas Is Not Scientific

From the results of the data analysis, we can see that the following three aspects are emphasized in the setting of policy content or policy element agendas: Focusing on public service-friendly policy settings. In general, public services accounted for 22.3%, second only to growth space (25.7%), and slightly higher than the development environment (21.3%). Public services include the development of infant care services, strengthening children’s health security, and enriching children’s sports services. It reflects that under limited resources, provinces prefer to improve the quality of public services to help children grow up healthy. Second, it is important to pay attention to the growth space of children. Among the five policy elements, growth space accounts for the highest proportion (25.7%). The creation of growth space is beneficial to promote the transformation of urban space suitable for children, so the design of urban space considers the characteristics of children’s age. Third, it is important to pay attention to the creation of an environment for the development of children. The construction of a development environment is conducive to eliminating the adverse effects of the social environment and building a barrier to protect the safe development of children. However, the current child-friendly city construction policy does not pay sufficient attention to the two main social policy elements and rights protection. The coverage rate is 15.3%. This reflects the fact that the policy of building child-friendly cities in China does not pay enough attention to children’s rights and the social policy environment. By examining China’s child-friendly policies and institutions, we found that child-friendly laws and policies are generally found in the texts of specific areas [32]. For example, the Civil Code, the Law on the Protection of Minors, the Compulsory Education Law, and the Opinions on Strengthening the Protection of Children in Distress. Special laws and child-friendly policies related to child welfare are temporarily absent. To some extent, it restricts the promotion and sustainability of the construction of child-friendly cities [33]. Second, government responsibilities related to children’s survival and development are distributed within civil affairs, women’s and children’s working committees, women’s federations, league committees, education, and other line systems. Specialized institutions for protecting children’s rights are not well developed. Furthermore, there is a lack of specialized complaint organs to protect children’s rights [34].

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The core concept of child-friendly cities lies in the formulation and implementation of a series of policies and practical measures, ensuring that the rights of children in urban life are fully respected. A child-friendly city is not simply a suitable space for children to live in. It is also an environment that can fully stimulate children’s potential and promote their overall development. The construction of child-friendly cities is guided by the realization of children’s well-being. In the process of “letting the city return to children”, we should realize the fairness of urban life and the mainstream values of public life. This is not only a new way to solve the problems faced by human cities, but it is also a new way to solve these problems. It is also the pursuit of a more diversified and better human life.

The construction of child-friendly cities in China has just begun, and there are still many shortcomings in policy design. This policy emphasizes the supply of top-down policies. However, it did not consider the actual situation in some places or the needs of children when designing the policy agenda. The rights of the child and the formulation of social policies are generally neglected; we should pay more attention to the construction of public services for children, growth spaces, and development environments. To some extent, this neglect weakens the effect of policy implementation. China should learn from the advanced experience of foreign countries in the construction of child-friendly cities, based on the national conditions of China and the actual growth of its children, to improve the policy of building child-friendly cities and improve its implementation.

Based on the above discussion and the actual situation of the construction of child-friendly cities in China, this document proposes some suggestions and measures to build a child-friendly policy in China.

First, the use of policy tools should be balanced, and the allocation of policy tools should be optimized. The proportion of policy tools used affects the effectiveness of policy implementation. Establishing a systematic and coherent system of policy tools is conducive to improving the utilization rate of policies and realizing the transformation from ”single” to ”multiple” [35]. China should properly optimize the structure of policy tools and maximize the advantages of coordination among policy tools. An emphasis should be placed on increasing the frequency of the use of demand-oriented policy tools and moderately weakening the use of supply-oriented policy tools, as well as effective use of three types of policy tools to maximize the release of policy-driven effects [36]. At the same time, we should also pay attention to the structural balance of the internal sub-tools and optimize the internal structure of policies as much as possible [37]. When reducing supply-side policy, land security and capital investments should be increased to ensure that children’s developmental needs are met in a basic physical space. When strengthening demand-oriented policies, we should focus on increasing the frequency of exchanges and cooperation and the use of government purchasing tools to broaden our horizons, providing excellent experience and improved quality of child welfare projects. When strengthening environmental policies, attention should be paid to strengthening industrial development and market management.

Second, we should pay more attention to children’s rights and ensure the realization of children’s basic rights. Although specific models of child-friendly city construction vary from country to country, their core is the same, that is, focusing on the implementation of children’s rights. In particular, guarantees of the right of children to participate [38]. Contemporary China should pay more attention to children’s rights and protect basic human rights, which are based on existing laws and policies related to children. We will accelerate the construction of a typological and hierarchical legal and policy system that covers the interests and needs of children and their families. Prompt enactment of child-friendly legislation specifically related to the welfare of children aims at the weak links of child-friendly policies, such as child protection, child mental health, inclusive nurseries, and family education, strengthening policies supporting the welfare of children and their families [38]. However, the protection of children’s rights should be included in planning as a priority, and a special complaint mechanism for children’s rights should be established. We should give full play to the important role of children’s rights and interest-protection organizations in the promotion of children’s rights and attach equal importance to the cultivation of rights awareness and rights relief, providing a rigid and lasting legal policy and a soil of social concept for the cultivation of the concept of children’s rights [39].

From a policy design perspective, we should strengthen the development of demand-driven policies, such as fostering a societal environment that prioritizes children’s rights and creating a supportive social atmosphere, as well as cultivating family, school, and societal environments conducive to healthy development. The government should enhance its functions in providing services for children, establish effective mechanisms to legally prevent and severely punish criminal activities targeting children, and strictly enforce online criminal activities that infringe on children’s legitimate rights and interests. It should also strengthen international cooperation and exchange, actively absorb experiences from other countries in building child-friendly cities, promote social participation, and guide third-party organizations to provide services related to children’s healthy development.

Third, under the guidance of the international framework for the construction of child-friendly cities, we will explore the establishment of a monitoring and evaluation mechanism for the construction of child-friendly cities in light of local conditions. On the one hand, we should strengthen process monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for constructing child-friendly cities. For example, the implementing party should regularly monitor the implementation process and evaluation of the phased construction of child-friendly cities through a multiparty cooperation framework and joint meetings to evaluate achievements, difficulties, potential resources, and opportunities [40]. However, efforts should be made to improve impact monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for constructing child-friendly cities. The proposed system provides the corresponding basis and rectification measures for the feedback system to help build a child-friendly city. Such as the development of a checklist to monitor and assess the impact of the construction of child-friendly cities. A team of experts, including government personnel, experts, scholars, and professional childcare workers, was established to conduct field surveys and visits. Finally, an impact assessment report is prepared. To monitor and evaluate the impact of child-friendly city construction on children, their families, communities, and urban development [41].

Of course, this study still has some shortcomings, such as the lack of comparisons between domestic and international policies on child-friendly city construction, the lack of research on the actual effectiveness of child-friendly city construction in China, and the lack of in-depth comparisons between different types of policies and policy tools for child-friendly city construction. In the future, we plan to conduct a comparative analysis of domestic and international policies on child-friendly city construction and conduct an empirical evaluation of such policies.

Author Contributions

Q.W.: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, and writing—review and editing. H.C.: data curation, methodology, and writing—review and editing. Q.Z.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, visualization, and writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Fund for Humanities and Social Sciences Research of the Ministry of Education (23YJC820013).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are provided within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without commercial or financial relationships, which could be understood as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Simon-i-Mas, G.; Honey-Roses, J. A global overview of Bike Bus: A journey toward a child-friendly city. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2024, 18, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rut, M.; Davies, A.R. Transitioning without confrontation? Shared food growing niches and sustainable food transitions in Singapore. Geoforum 2018, 96, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, T.; Bailey, A.; Kerr, N.; Walton, A.; Ferrington, L.; Cecilio, M.E. Start small and let it build; a mixed-method evaluation of a school-based physical activity program, Kilometre Club. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P. Child-Friendly Urban Development: Smile Village Community Development Initiative in Phnom Penh. World 2021, 2, 505–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Azizan, S.A.; Huang, H. GIS-based intelligent planning approach of child-friendly pedestrian pathway to promote a child-friendly city. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberg, C. The Child-Friendly Cities Initiative-Minneapolis Model. Matern. Child Health J. 2024, 28, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, G.; Shi, Y.; Chen, R. Environmental affordances and children’s needs: Insights from child-friendly community streets in China. Front. Arch. Res. 2023, 12, 411–422. [Google Scholar]

- Kamelnia, H. A Paradigm Shift to CA in Spatial Indicators of Children’s Environment: An Investigation of Children’s Participation in Design and Relation to SCI: Case of CFC of BAM, 2005–2020. Child Indic. Res. 2025, 18, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhbari, P.; Mohammadi, N.K.; Zayeri, F.; Ramezankhani, A.; Hakimian, P.; Sahamkhadam, N. Design and validation of Iranian Child Health-Friendly Neighbourhood checklist: A mixed-methods study. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2024, 8, e002918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhbari, P.; Keshavarz-Mohammadi, N.; Ramezankhani, A. Child health-friendly neighbourhood: A qualitative study to explore the perspectives and experiences of experts and mothers of children under 6 years of age in Tehran, Iran. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e077167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-del-Pulgar, C.; Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T. Child-friendly urban practices as emergent place-based neoliberal subjectivation? Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 2349–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsavounidou, G.; Sousa, S. Reimagining Urban Spaces for Children: Insights and Future Directions. Urban Plan. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanian, M.; Laszkiewicz, E.; Kronenberg, J. Exposure to greenery during children’s home-school walks: Socio-economic inequalities in alternative routes. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 130, 104162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Million, A.; Schamun, K.; Fegter, S. Understanding Well-Being Through Children’s Eyes: Lessons for Shaping the Built Environment. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 8618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torun, A.O.; Akin, I.Z.; Bingol, H.; Defeyter, M.A.; Severcan, Y.C. Children’s Perspectives of Neighbourhood Spaces: Gender-Based Insights From Participatory Mapping and GIS Analysis. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D. Challenging Child-Friendly Urban Design: Towards Inclusive Multigenerational Spaces. Urban Plan. 2024, 9, 8495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Jabbour, N.; John, D.; Ahmad, A.M.; Furlan, R.; Al-Matwi, R.; Isaifan, R.J. The impact of urban design on mental well-being by integrating green spaces in Doha City, Qatar. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, A. Examples of good experiences for child-friendly cities. Comparison of sustainable practices in Italy and around the world. TeMA-J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2024, 2, 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, K.; Anund, A.; Pettigrew, S. Autonomous shuttles contribution to independent mobility for children—A qualitative pilot study. J. Urban Mobil. 2023, 4, 10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Church, A.; Maskiell, A.; Raisbeck, P.; Eadie, T. Design considerations in the activation of a temporary playspace for children and families: Perspectives of council, architects and designers. Aust. Plan. 2023, 59, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Parker, D.C.; Drescher, M. Adoption determinants and policy tools for residential green stormwater infrastructure: A review synthesizing differences and commonalities among lot-level practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasnezhad, B.; Abrams, J.B. Are prevailing policy tools effective in conserving ecosystem services under individual private tenure? Challenges and policy gaps in a rapidly urbanizing region. Trees For. People 2025, 19, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegveld, W. Technology policy under changing socioeconomic conditions. Environ. Plan. C-Gov. Policy 1988, 6, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capano, G. Policy implementation and policy instruments: The underdeveloped dimensions of the four “political” American policy process theories. A Western European perspective. Eur. Policy Anal. 2025, 11, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, D.; Hang, T.; Ding, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Q. Constructing child-friendly cities: Comprehensive evaluation of street-level child-friendliness using the method of empathy-based stories, street view images, and deep learning. Cities 2024, 154, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Furuya, K. A Bibliometric Analysis of Child-Friendly Cities: A Cross-Database Analysis from 2000 to 2022. Land 2023, 12, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoto, S.; Cordaway, C.; Napolitano, A.; Foy, J.; Pan, C.; Bellizzi, K. A Content Analysis of #Childhoodcancer Chatter on X. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Elkhouly, A.A.N.; Shukla, P.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, S.; Ni, M.; Fan, S.; Gunay, Z.; et al. The child-friendly cities concept in China: A prototype case study of a migrant workers’ community. Int. Soc. Work 2024, 67, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Vinueza, V.A.; Niekerk, F.F.; van Dijk, T.T. Making child-friendly cities: A socio-spatial literature review. Cities 2023, 137, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Savahl, S.; Florence, M.; Jackson, K. Considering the Natural Environment in the Creation of Child-Friendly Cities: Implications for Children’s Subjective Well-Being. Child Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, N.J.; Sundari, L. A new platform taps the ban through child-friendly cities. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2021, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, F. Policy innovation on building child-friendly cities in China: Evidence from four Chinese cities. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Fang, Z.; Lee, C.; Shang-Kuan, C.; Mao, L.; Chiang, Y. Building a child-friendly social environment from the perspective of children in China based on focus group interviews. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 2001–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zheng, B.; Liu, J.; Tian, F.; Sun, Z. Research on Child-Friendly Evaluation and Optimization Strategies for Rural Public Spaces. Buildings 2024, 14, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yang, L.; Qian, B.; Yang, Y.; Wei, G.; Li, C. Physical-medical integration policies and health equity promotion in China: A text analysis based on policy instruments. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Liu, J.; Mai, Q. Exploring the impact mechanisms of the green innovation policy instruments system: A system dynamics approach. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 9949–9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Gao, J.; Yuan, J. Issue uncertainty and selections of policy instruments in policy pilots: Evidence from China’s long-term care insurance. J. Asian Public Policy 2024, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Kim, D. Children as Key Actors in Participatory Planning: Co-Working Experience of Community Planning for Walking Safety Around Bongrae Elementary School in South Korea. Plan. Theory Pract. 2024, 25, 321–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Fang, Z.; Mao, L.; Ma, H.; Lee, C.; Chiang, Y. Creating A child-friendly social environment for fewer conduct problems and more prosocial behaviors among children: A LASSO regression approach. Acta Psychol. 2024, 244, 104200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Huang, J.; Jia, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J. Evaluation of route choice for walking commutes to school and street space optimization in old urban areas of China based on a child-friendly orientation: The case of the Wuyi Park area in Zhengzhou. Child. Soc. 2024, 38, 1527–1556. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Yu, C.; Liu, X. Evaluating the Quality of Children’s Active School Travel Spaces and the Mechanisms of School District Friendliness Impact Based on Multi-Source Big Data. Land 2024, 13, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).