1. Introduction

In a time where sustainability has become a global issue, circular economy strategies are seen as the most plausible methods to transition toward a restorative future [

1]. Although research in major urban areas has been conducted abundantly [

2,

3], it is not quite deeply conducted in small historic towns. As for these historic small towns with rich cultural heritage and traditional practices, they are extremely rare, which is why studying them is so beneficial for understanding how the principles of the circular economy can help to maintain high historical value while at the same time ensuring sustainable development [

4,

5].

A critical review of current literature reveals a significant gap in integrated approaches that simultaneously address circular economy implementation, heritage preservation, and stakeholder engagement in small historic contexts. While urban metabolism studies dominate large city research [

6,

7], and heritage preservation research focuses primarily on conservation rather than adaptive sustainability [

8,

9], no existing framework systematically combines these approaches for small historic towns with traditional economic activities.

This research bridges these gaps through three main objectives. First, developing an Integrated Methodological Framework specifically designed to evaluate the circular economy potential in historic small towns [

10]. Second, identifying how traditional practices and cultural heritage can strengthen rather than constrain sustainability transitions. Third, providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers and practitioners managing circular economy transitions in heritage-rich contexts [

11].

In our Integrated Methodological Framework, three comparable aspects are incorporated. Firstly, urban metabolism analysis [

12,

13] gives the central perspective on understanding the flows of resources and their circularity. Stakeholder engagement theory [

14] is the tool for interpretation of the social dynamics of sustainability transitions underlying this. Last but not least, the development strategies dear to heritage [

15,

16] guarantee that cultural preservation is at the heart of the transition process.

This study is significant in three ways. From a theoretical perspective, it demonstrates how circular economy concepts can be embraced in small historic contexts and, referring to the current urban metabolism theories, can go beyond their traditional focus on large cities. On a methodological level, the integration of quantitative and qualitative approaches provided by this research, which has been specifically designed for the heritage-rich context is a novel Integrated Methodological Framework. It also offers evidence-based data for policymakers and practitioners who are in charge of managing similar transitions at the global level, which is the practical implication of the study.

To achieve these objectives, three primary research questions are addressed:

RQ1. How can circular economy principles be implemented in small historic towns without compromising cultural heritage?

RQ2. To what extent do traditional practices facilitate or hinder circular economy transitions?

RQ3. What are the key strategies for effective stakeholder engagement in heritage-rich sustainability transformations?

These questions are considered through the lens of a detailed case study of Taurasi, a historic wine-producing township from the Campania region of Italy. Taurasi is the best representation of the study because it shows the small historic towns moving toward sustainability the difficulties as well as the advantages. Through the town’s old-school wine-making tradition, its cultural legacy, and the social networks that are already there, this town becomes a real-life laboratory for a case study about the relevance of circular economy principles to heritage preservation.

This research integrates four interconnected thematic pillars to address circular economy implementation in heritage contexts: urban metabolism analysis provides the quantitative foundation for understanding resource flows and circularity potential; stakeholder engagement theory addresses the social dynamics essential for sustainability transitions; cultural heritage preservation ensures that traditional values guide rather than constrain innovation; and wine culture serves as the specific cultural lens through which these concepts interact. These themes converge through their shared focus on sustainable resource management while respecting cultural authenticity, creating a novel analytical framework specifically designed for historic small towns.

Methodologically, this research contributes by developing an Integrated Methodological Framework specifically designed for heritage-rich contexts where traditional urban metabolism approaches may be insufficient due to data limitations and the need for heritage-sensitive analysis. The framework’s primary value lies in its replicability and systematic approach to analyzing complex circular economy implementation challenges in small historic towns.

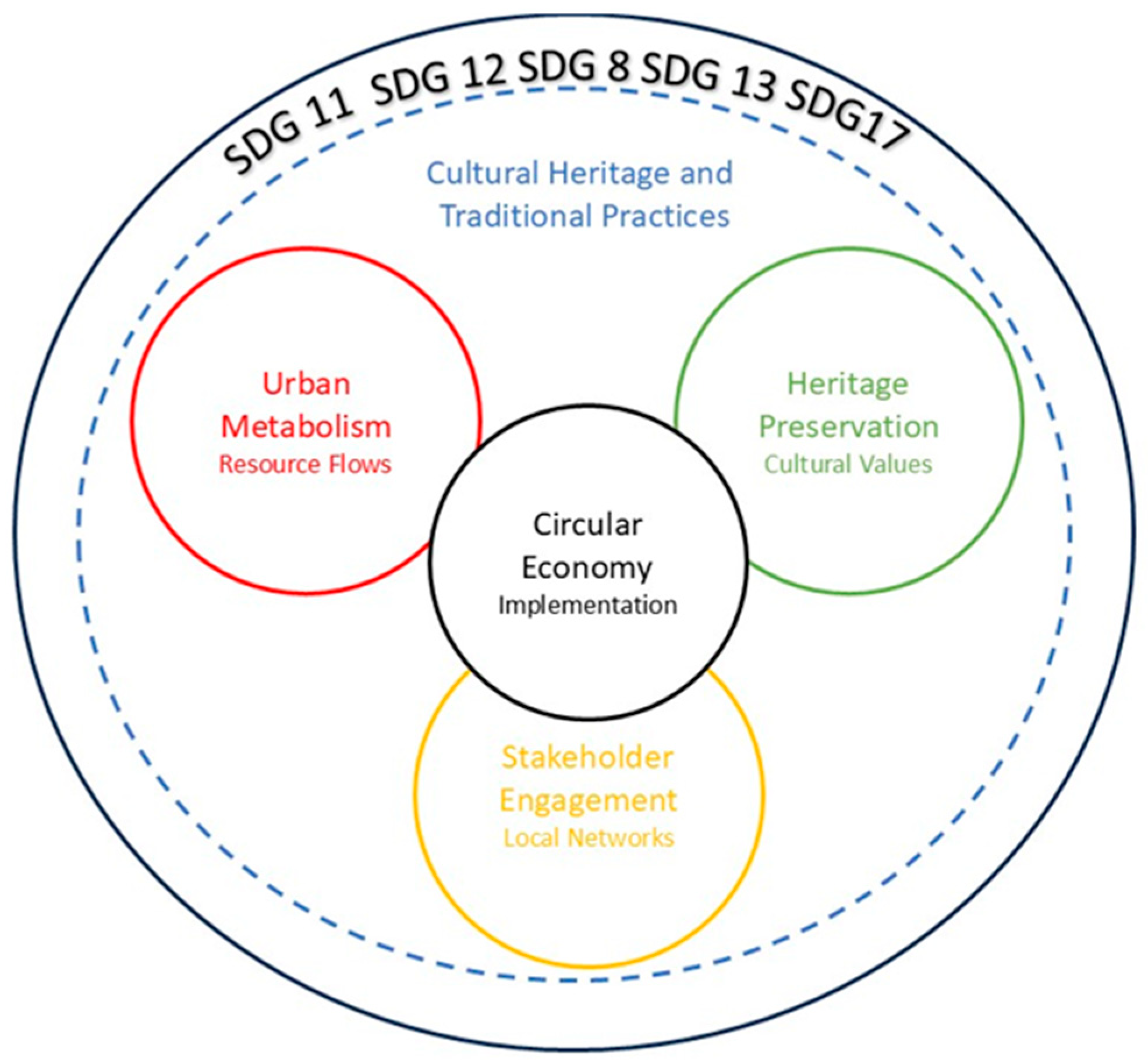

This research develops a novel Integrated Methodological Framework that integrates urban metabolism analysis, stakeholder engagement theory, and heritage preservation strategies to enable circular economy transitions in historic small towns while preserving cultural heritage and traditional practices.

This research has multiple connections with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It brings positive change to SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) through heritage preservation and sustainable urban development. The principles of a circular economy are related to SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), as well as the sustainable tourism and wine industry development path to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). The research also impacted SDG 13 (Climate Action) by resource efficiency, and it also addressed SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) by multi-stakeholder engagement [

4,

17].

Our method consists of two parts: one is measuring urban metabolism in a quantitative way and the other one is conducting a qualitative analysis of the different stakeholders and urban morphology. This multidisciplinary approach provides a holistic view of the complexities of how small historic towns can be transformed to the principles of circular economy [

9,

18].

The organization of the paper is the following.

Section 2 contains a comprehensive review of the literature on urban metabolism, circular economy, and heritage preservation.

Section 3 describes the methods applied and the data sources used.

Section 4 presents the case study of the findings and goes on to discuss it.

Section 5 wraps things up by highlighting the implications for theory and practice and future research directions. In this way, it shows the way for a successful transition of small historic towns towards circular economy principles through the preservation of their cultural heritage, hence giving insights into similar situations around the globe.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context: The Case of Taurasi

The municipality of Taurasi represents a good chance to look into the circular economy implementation in historic small towns. The local council has started a strategic plan (SP), which was prepared in collaboration with academic consultants and specialists, and aims to improve the town’s approach to sustainable development, keeping its cultural heritage.

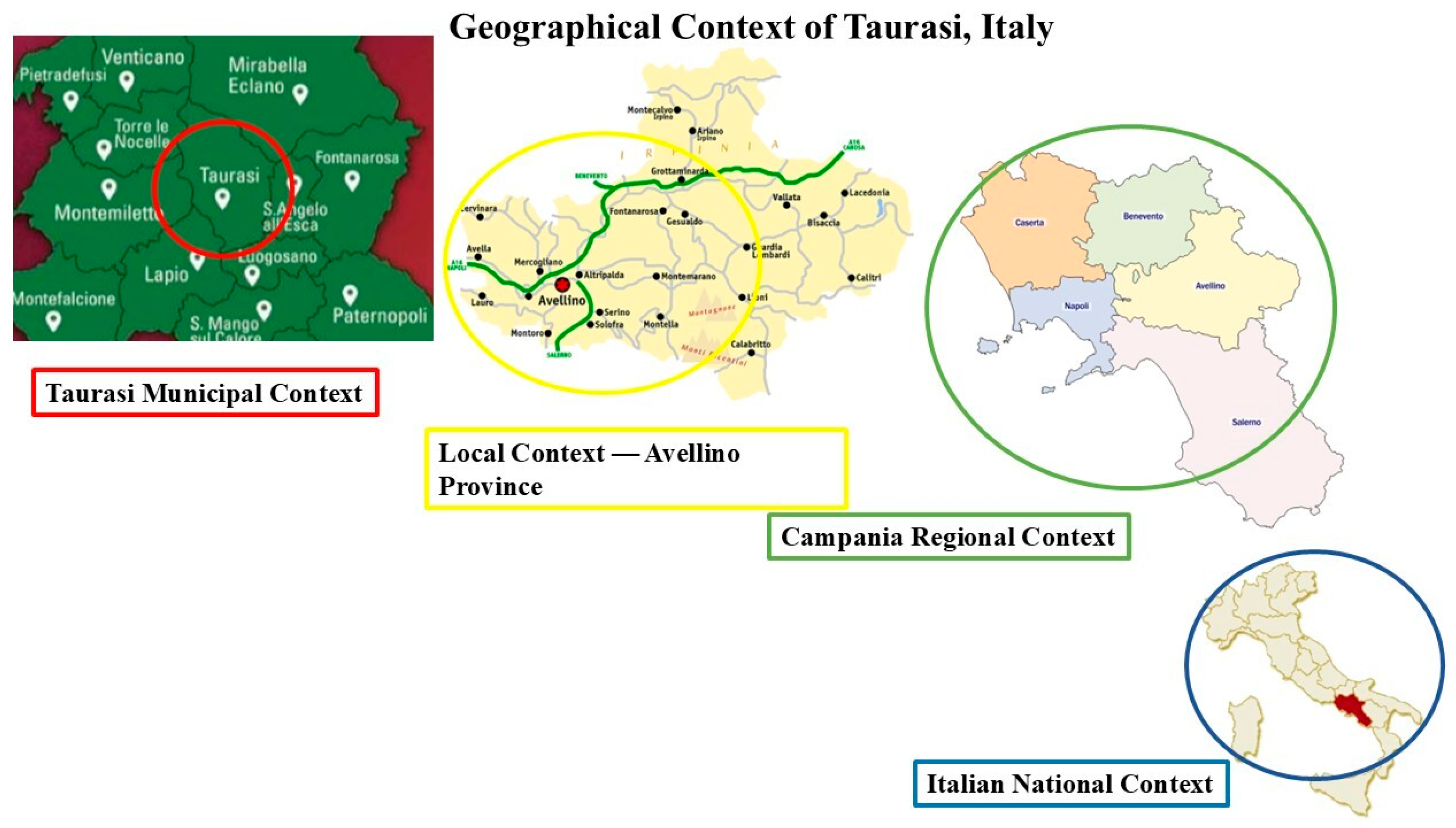

Taurasi, part of Italy’s Avellino province, occupies about 14.09 km

2 of land with different types of terrain (

Figure 1).

The town’s unique landscape, which is between 250 to 600 m above sea level, has been the main factor in its development and also its location. This geographical feature is so vital to the town and its economic base that, due to the high-quality Taurasi DOCG, the town’s identity was founded and its livelihoods were secured. The above-mentioned wine is still a main economic driver and cultural identity cornerstone.

According to the latest city council analyses, the current population of the city is about 2300 with a density of 163 inhabitants per kilometre square. The scale of this category, which is the most predominant demographic category of Italian municipalities, is covered by around 70% of the Italian towns having populations below 5000. The settlement pattern follows the traditional arrangement, with most people being easily mapped out in the central historic town, and a few other places whereby agriculture, mainly in the form of vineyards, is the main practice.

The town’s plan of action in the area of strategic planning includes several interrelated objectives such as the preservation of cultural heritage, the development of sustainable tourism, the wine industry revival, and the modernization of infrastructure. Although primarily being implemented within the city’s boundaries, the initiative has far-reaching regional goals, thus it may become a breeding ground for the neighboring municipalities of both Avellino province and Campania region at large.

This case study makes Taurasi different because it is a place that has both challenges and opportunities in a circular economy transition. The town’s approach is not only looking at the way things are done now in the area of resource utilization but also thinking about how to make life better for the people there in the future. The project to bring the old buildings into use for tourism is a typical example of the town trying to find a balance between the two. Along with growth, preservation is initiated.

The local authority has built its development strategy around several key initiatives which include both the city’s rehabilitation program and the refurbishment of the buildings, thus giving a sense of architectural continuity to the city’s history along with being a tourist attraction program. They carry out these activities within a structure that encompasses the understanding of the necessity to uphold the original image of the town, although introducing new sustainability elements.

Therefore, Taurasi is the most suitable platform for research work on the application of circular economy principles in such historic small towns.

The main instruments to interpret this town are preserved cultural heritage, robust agricultural tradition, as well as a crystal clear development strategy, which provides a wide range of conditions in which a culture can remarkably survive this shift from development policies and the adoption of digital tools while maintaining the valuable cultural heritage of the locality.

3.2. Research Design

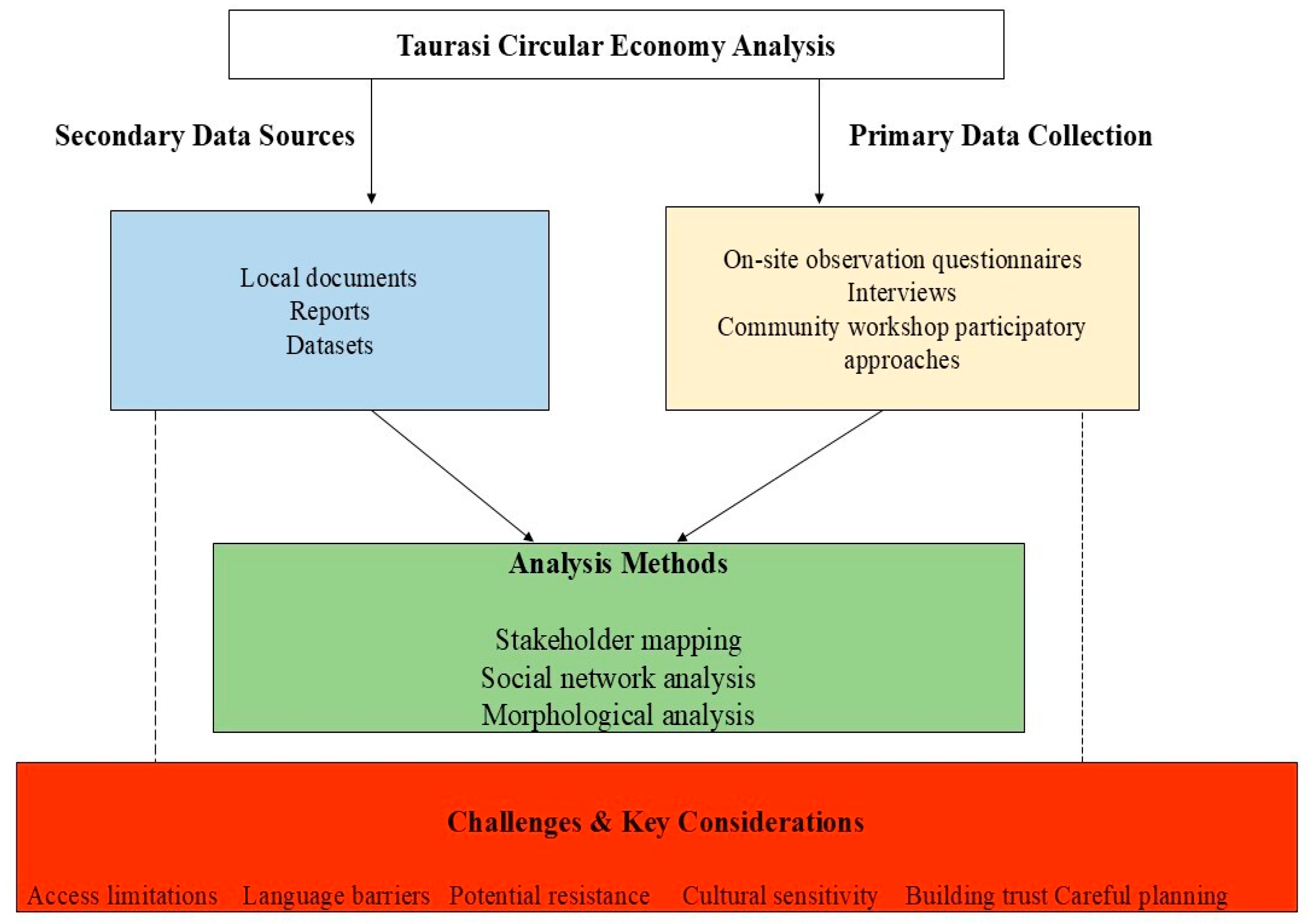

Applying the principles of a circular economy in historic small towns is a very complicated process that requires a holistic methodological approach able to grasp not only quantitative resource flows but also qualitative socio-cultural dynamics. It employed the mixed-method research design that enacts the urban metabolism analysis in combination with stakeholder engagement and morphological assessment. In this way, several strands of sustainability were touched upon at the same time, and the peculiarities of historical contexts have been respected.

Figure 2 illustrates the methodological operationalization of our Integrated Methodological Framework developed in

Section 2.4. The three analytical dimensions (urban metabolism, stakeholder analysis, and morphological assessment) directly correspond to our theoretical pillars, while the PESTEL framework provides the external context analysis that links local heritage considerations with broader sustainability transitions. This methodological coherence ensures that our empirical investigation systematically addresses each component of our Integrated Methodological Framework.

In addition, with the use of advanced social network mapping techniques [

9], a stakeholder analysis was involved and thus connections between the different actors within the transition of Taurasi to a circular economy were considered. This element is the key way of solving SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) since it investigates the relationships among sustainable practice actors in the implementation of sustainable practices and the preservation of cultural heritage.

Finally, morphological design research is the direction that our physical structure allows us to evaluate both the visual urban structure and cultural heritage elements that have together with others mentioned by [

8]. The application of this concept enables us to engage with, rather than detract from, the dynamic potentiality of the built environment to channel this transition towards a circular economy paradigm.

The main reason for choosing a case study approach as the research methodology is that, following [

24] criteria for case selection, it is possible to take a deep look at complex phenomena that exist in the real-world context. Taurasi is an ideal case for analyzing the way through which historic small towns can use circular economy methods and at the same time maintain their cultural heritage, especially in the regions of traditional wine production.

In order to ensure the scientific validity of the methods, a process of triangulation from information from different sources was adopted. A primary data collection technique is used to obtain the data from field observations and stakeholder interviews. Secondary data is taken from the local government documents and historical records. Besides, quantitative data on the resource flows and economic activities is also considered. Finally, the qualitative data on the social practices and cultural traditions is also verified.

This methodology specifically accomplishes multiple SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) due to its integrative view. It is the interconnectedness between analyzing urban form and heritage preservation in SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) that makes the study possible.

Analyses of resource flows and circular practices are supporting SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) while the assessment of economic activities, particularly in the wine sector, is an additional element to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). The evaluation of the results of the measures for energy efficiency, sustainability, and thus the attainment of SDG 13 (Climate Action).

The development follows the Integrated Methodological Framework recommended by [

18] that is used in urban metabolism studies and takes [

15] heritage-sensitive development approach into consideration.

This integration lets us look into both the technical sides of circular economy implementation and the socio-cultural aspects of sustainability transitions in historic contexts.

Our method, in particular, deals with the data shortage issues raised by [

9] in historic small-town contexts via revised data collection procedures and inappropriate data availability, qualitative assessments are also integrated where quantitative data is lacking, participatory approaches to knowledge sharing are encouraged and the urban sensing technologies for small-scale are rethought for their use.

The following sections describe the particular methods that have been adopted for data collection and analysis regarding this Integrated Methodological Framework.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Protocols

The four circular economy principles defined in

Section 2.1 (Resource Loop Closure, Life Extension, Resource Efficiency, and Collaborative Consumption) are applied through heritage-sensitive methodologies:

- -

Respect traditional knowledge systems while introducing efficiency improvements.

- -

Utilize existing social structures for circular economy implementation.

- -

Maintain architectural and cultural integrity during resource system modifications.

- -

Integrate local economic activities with broader circular economy networks.

The research project needs a totally well-thought-of data-gathering strategy that sticks to both secondary and primary data sources. Secondary data collection feeds from local publications, reports, and database information to give a clear idea and background [

18]. Still, the literature points out that data availability and quality can be low in historic small towns, so there is a need for creative ways of collecting data.

The primary data was gathered via semi-structured interviews conducted in a two-month period (May–July 2024). The project involved ten important stakeholders, two of whom were experts from local government offices in the municipal administration, three representatives of wine cooperatives, two of the local business owners, one of the environmental leaders, and two of the cultural heritage experts. After [

13], the stakeholder selection was based on purposive sampling. Stakeholders that meet the following categories are chosen: those involved in the tradition’s practices; decision-making in the organization and sustainability issues initiatives.

Direct observations were conducted during the same two-month period, focusing on urban metabolism flows including energy, materials, and waste, traditional wine-making processes, heritage building utilization patterns, and community interaction networks. These observations were systematically documented using standardized field notes and photographic evidence. Community engagement methods, such as participatory workshops, were developed to involve stakeholders and capture local knowledge [

8].

The analysis of the documents included the Municipal Urban Plan (L.R. 16/2004), SIAD updated documentation (December 2021), a historical record of traditional practices, a local development plan, and agricultural census data (1991–2001). The identification of documents gives in-depth information of descriptions background regarding the area and the basic data for Taurasi’s transformation and resource utilization patterns.

Triangulation techniques were used to validate research data. The interview data were corroborated with the documentary evidence, while observational data were covered by the feedback of the stakeholders. The data pattern derived from the historical data was used to compare the current and past practices to show the changes over time. The key informants did this by introducing the member-checking process, which helped in ensuring the accuracy and completeness of the interpretations.

The analytic process included several auxiliary methods. Transcripts from the interviews were subject to thematic analysis which was done through coding protocols that gravity around circular economy topics. Pattern matching from multiple data sources was used to increase the trustworthiness of the findings. The quantitative analysis of census and resource flow data gave measurable benchmarks, as well as iterative verification with stakeholders through follow-up consultations which guaranteed the accuracy of interpretations and conclusions.

3.4. PESTEL Analysis Framework

The PESTEL (political, economic, social, technological, environmental, legal) analysis framework serves as our external environment assessment tool, examining macro-level factors that influence circular economy transitions in heritage contexts. This framework complements our primary methodological approach by providing a systematic analysis of external constraints and opportunities that affect the local implementation of circular economy principles (

Figure 3). PESTEL analysis has been successfully applied in sustainability transitions research [

25], making it particularly suitable for our heritage-sensitive context.

Our research incorporates many methodologies aimed at gaining a comprehensive understanding of the green strategy of Taurasi. The PESTEL framework is the major means, which looks at external factors affecting the creation of the town of Taurasi. This organized pathway is a way to study politics, economy, society, technology, the environment, and legal factors that influence operations and dealings in the territory [

32,

33].

The main politic-economic issues to look at include the laws impacting the wine industry and the trade agreements being followed, besides the national/EU policies. Economic factors concern the consumers’ income distribution, currency value which is sensitive to the fluctuating interest rate, and the production costs that are involved in the process. Social, technological, environmental, and legal factors focus on habits in Taurasi, implementation of digital tools in agriculture, climate change, and taxation and wine policies.

Following [

12] for the analysis of urban metabolism in the study of towns, material and energy flows through the town’s system were explored. This analysis has been continued in the context of the specifics of the particular dataset issued for the small-scale historic data environments, which was set as one of the key problems by [

9].

Stakeholder analysis through the use of the latest methods of the network of social networks depicts the complex interrelations among Taurasi’s populace and stakeholders in the circular economy transition. This approach looks into the government structures’ knowledge-sharing, and collaboration patterns vital to the local loop’s success.

The study of socioeconomic trends is based on the research by [

8], which encompasses both quantitative economic indicators and qualitative appraisal of social dynamics. This holistic method allows us to see how traditional and modern sustainability mandates can be put together successfully.

Regarding cultural heritage, ref. [

10]’ frame was followed as a basis for analyzing ways in which the traditional elements are capable of being utilized sustainably. Thus, the assessment includes both physical heritage and intangible cultural practices, the latter of which is the main item of our research in this regard.

The analytical process consists of several key steps:

Data is initially organized and sorted according to the PESTEL framework.

Integration of quantitative and qualitative data sets.

The findings are cross-checked against various data sources.

Stakeholders confirm the correctness of the preliminary results.

The findings are aggregated across different analytical dimensions.

This is a thorough analytical method that helps us to detect trends, problems, and chances in Taurasi‘s move towards circular economy rules while at the same time, the town keeps its cultural identity. The outcome of this query delivers information about the way small, old towns could successfully carry out green transitions while still staying authentic.

3.5. Research Validity and Reliability

The research design is made up of a few different measures that make the research more scientifically sound and also add to the validity and reliability of our findings. Sticking to the approved and well-defined ground rules of qualitative investigation, we managed to bring in many verification pathways at different stages during the research process as per [

24].

Construct validity was augmented by using data triangulation from multiple sources of evidence. The formal documents and archival records from the local government contribute to historical and regulatory discourse as the walls where the buildings are founded. On the other hand, the dynamic mapping of urbanization and resource flows, through field observation, brings up the present situation.

In-depth interviews with different kinds of stakeholders help quantitative data on the use of resources and historical records of traditional practices are the necessary background. This multi-source strategy aids in the problem of data availability, which is typical in historic small towns, besides ensuring a thorough study of the phenomena.

Internal validity was improved via pattern matching and explanation building during data analysis. We regularly tested analysis processes to find out the cause and effect between circular economy initiatives and their results. More specifically, the point of attraction was the likely impact of traditional practices on the sustainability transition. The PESTEL framework was used as a conceptual guideline for the exploration of these connections; besides, stakeholder validation was employed to not only identify but also validate causal inferences.

Ensuring external validity while at the same time taking into account Taurasi’s atypical characteristics was covered by theoretical sampling in the interviewee selection and fine-grained documentation of the context and methods.

The comparison with the existing works on historic small towns and the identification of the context-specific and generalizable findings further increase the external validity of the study.

Reliability was boosted by the preparation of the case study protocol and the establishment of a complete case study database. Clear documentation of data collection procedures and standardized analysis protocols make sure of research transparency and duplication, which are very important for furthering the knowledge of sustainable development studies.

There are several limitations that deserve to be paid attention to. The narrow historic towns dimension of data availability constraints, cultural and linguistic potential in data gathering, and time limits in observing long-term transitions as well as the difficulty of quantifying some traditional practices affected the study. In order to cover these gaps, we adapted data collection methods that are valid in the local context, the involvement of local experts in cultural interpretation, the documentation of assumptions, and the constraints, as well as the recognition of the areas that require further research.

Therefore, the research design employs a balance between the methodological dimension and the practical factors, thus, the findings are successfully ensured to go well with both the theoretical understanding and practical implementation of the circular economy principles in historic small towns. This Integrated Methodological Framework is the first step to comprehending Taurasi’s transition from a linear economy to a circular economy which in turn can be a model for similar projects in other historical towns despite the idiosyncrasies that might affect generalizability.

3.6. Methodological Limitations and Framework Positioning

This study acknowledges the inherent challenges of conducting comprehensive quantitative analysis in historic small towns, as identified by [

9]. Data availability constraints, limited municipal record-keeping systems, and the informal nature of many traditional practices create methodological challenges that are common across similar research contexts.

Rather than compromising scientific rigor through data extrapolation, this research is positioned as an Integrated Methodological Framework development study. The Taurasi case serves as an illustrative application to demonstrate the framework’s potential rather than as a comprehensive empirical assessment. This approach follows the methodological precedent established by [

24] for exploratory case study research in complex heritage contexts.

The framework’s value lies in its integrated approach to analyzing circular economy potential while respecting heritage constraints. Future researchers can apply this methodology with more extensive data collection protocols to conduct comprehensive quantitative assessments. The study’s contribution is thus methodological rather than purely empirical, providing a foundation for systematic analysis of circular economy transitions in historic small towns.

Data collection limitations include the following: (1) limited availability of historical resource flow data, (2) informal nature of traditional practices making quantification challenging, (3) small sample size typical of historic town populations, and (4) time constraints on longitudinal observation. These limitations are addressed through methodological triangulation and explicit acknowledgment of the framework’s developmental nature.

3.7. Objectivity and Reflexivity Considerations

This research acknowledges the inherent subjectivity in heritage value assessments and stakeholder perspectives. To maintain analytical objectivity, we employ multiple verification strategies: triangulation across data sources, member-checking with stakeholders for interpretation accuracy, explicit documentation of researcher assumptions, and transparent presentation of conflicting viewpoints. The heritage context requires balancing analytical objectivity with cultural sensitivity, which we address through collaborative interpretation processes with local cultural experts and systematic bias identification protocols.

3.8. Circular Economy Indicators for Historic Small Towns

This framework incorporates adapted circular economy indicators specifically designed for heritage-rich contexts, addressing the limitations identified in traditional urban metabolism approaches for historic small towns [

34,

35].

Primary Indicators:

Heritage-Adapted Circular Material Use Rate (H-CMUR): modified from the EU’s standard CMUR to account for heritage building materials and traditional construction methods;

Traditional Practice Efficiency Index (TPEI): measuring resource efficiency in traditional economic activities (e.g., wine production waste utilization);

Cultural Heritage Resource Circularity (CHRC): assessing adaptive reuse of heritage buildings and spaces.

Secondary Indicators:

Stakeholder Network Density (SND): measuring collaboration effectiveness in circular economy initiatives;

Heritage-Economy Integration Rate (HEIR): evaluating successful integration of circular practices with cultural preservation;

Local Resource Loop Closure (LRLC): tracking local resource cycling within traditional economic sectors.

4. Results

4.1. Urban Metabolism Analysis

The evaluation of Taurasi’s urban environment points out three main pathways in resource use from 1991 to 2001. Firstly, agricultural land use experienced a great degree of transformation with the total area designated for agricultural use (SAT) shrinking to 563.12 hectares from 1126.97 hectares, and UAA embodied with a reduction rate of 43% (i.e., out of 989.3 hectares to 563.12 hectares). The variation in resource flow and circular economy potential happens to be a direct effect due to this.

Second, farm structure analysis demonstrates an extremely high degree of fractionalization (in an average of 1.5 hectares each), with 97% of farms having less than 5 hectares. Farm numbers fell by 19.94% (from 742 to 594), the decline equaling 1.2% of the total farms in Avellino Province. This split is crucial in determining how the resources are distributed and what can be shared.

Third, trends of labor and mechanization point to the growing issues related to resource efficiency with as many as 90% of farms being part-time and higher mechanization levels compensating for a drop in the number of family farm workdays. These shifts will affect the capacity for the introduction of options on how to implement circular practices in the traditional agriculture setting [

25].

These resource utilization patterns demonstrate “Resource Loop Closure” through traditional agricultural waste cycling and “Resource Efficiency” optimization in vineyard management practices.

The resource utilization patterns and land use transformation modalities thus contribute to multiple SDGs directly. The modern farming ways empower SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), as they are derived from resource management that is optimized. On the other hand, land use modifications beg for careful planning that approves SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities) so as to keep settlement sustainability intact. The high level of farmland fractionalization is a bottleneck in some cases, nevertheless; however, it gives scope for the preservation of biodiversity and managing the land sustainably, in line with SDG 15 (Life on Land).

4.2. Stakeholder Analysis

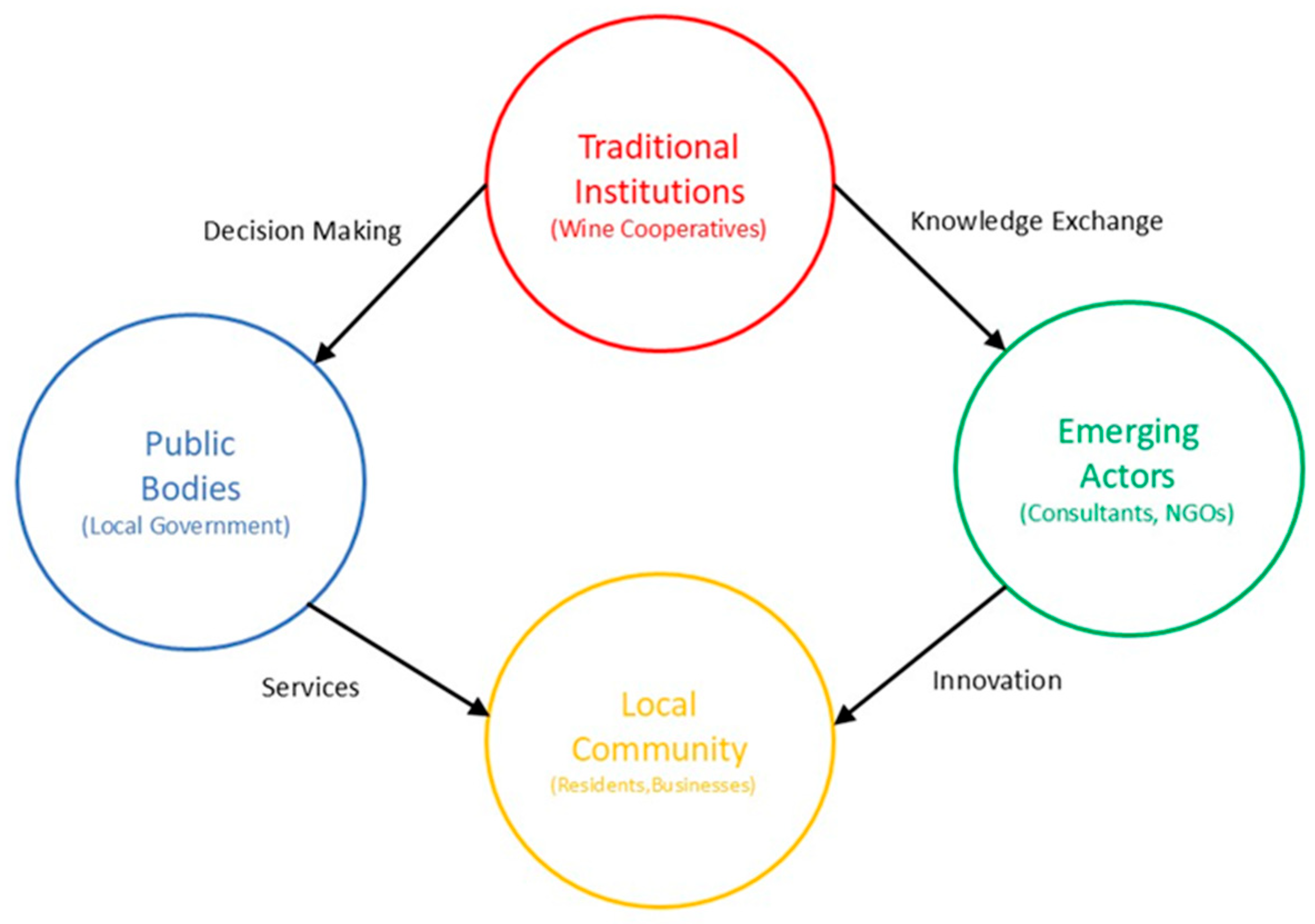

According to the SIAD analysis (December 2021), the situation is complex, as both the public and private sectors are stakeholders. The main findings show three major categories of stakeholders: traditional organizations (mostly wine cooperatives), new actors (consultants, and environmental organizations), and local people (

Figure 4). The study shows that traditional organizations still have the main decision-making power, while the new stakeholders offer fresh ideas that challenge outdated methods.

The stakeholder mapping conveys the strength of the informal networks that are reshaping the ways resources are managed. These networks are mainly in the wine production sector and are the main sustainers of the circular economy if properly involved. Nonetheless, the current governmental structure shows little integration of sustainability aspects in the decision-making process.

The stakeholder interview analysis reveals three critical themes regarding circular economy implementation. First, knowledge transfer mechanisms emerged as crucial: traditional winemakers expressed willingness to adopt sustainable practices when presented within familiar cultural frameworks. As one cooperative leader stated: ‘We have always worked with nature’s cycles, but now we understand these as circular economy principles.’

Second, institutional barriers were consistently identified: seven of ten interviewees cited regulatory complexity as the primary obstacle to implementing innovative practices. Municipal representatives acknowledged that current planning frameworks lack specific provisions for heritage-sensitive circular economy projects.

Third, collaborative potential exists but requires structured facilitation: all stakeholder categories expressed interest in cross-sector partnerships, but informal networks currently lack coordination mechanisms. The wine sector’s established cooperative structures provide existing platforms for circular economy initiatives, but these require integration with municipal planning processes and environmental organizations.

The stakeholder network configuration exemplifies Collaborative Consumption principles through existing cooperative structures, while traditional organizations demonstrate Life Extension of established social capital for sustainability transitions.

This heterogeneous stakeholder network configuration directly facilitates SDG 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) through the active involvement of and collaboration with multiple stakeholders.

SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) is reinforced through the governance process by making participation inclusive; additionally, the introduction of both the old and the new economic factors of a country’s economy to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) is ensured through sustainable business [

33].

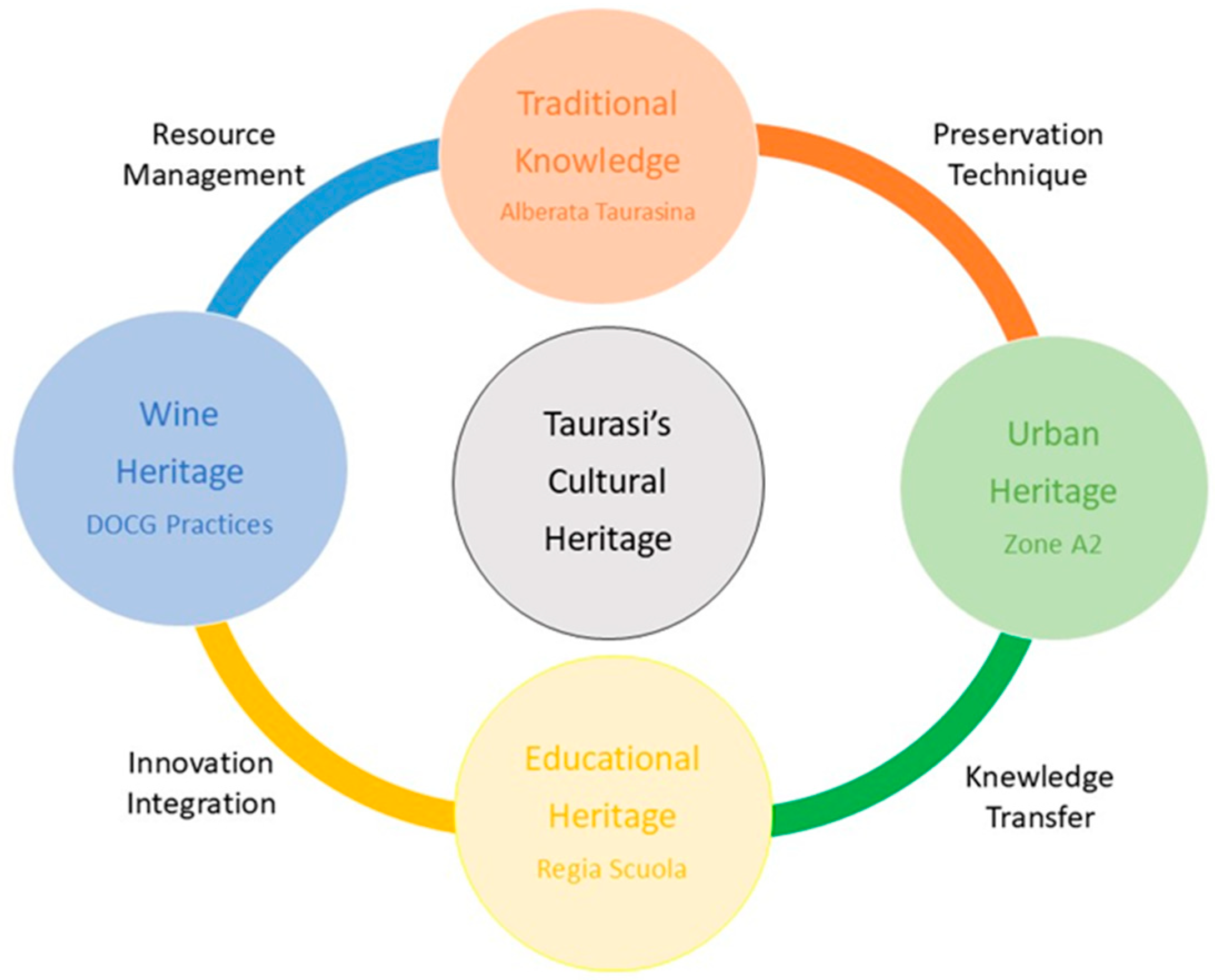

4.3. Cultural Heritage Assessment

The investigation of Taurasi’s cultural heritage has exposed key dimensions critical to circular economy implementation (

Figure 5). The heritage of the wine production, mainly the DOCG Taurasi, contains both material and immaterial parts [

26]. Wine-making practices that go back to history, e.g., the “Alberata Taurasina” system long before the Etruscan era, highlight pre-existing circular principles in the proper management of resources which, in turn, led to the cultivation of very special grape varieties.

Identified as Zone A2, the historical center of the city is the most ancient core housing the heritage area where development is regulated through restriction to preserve architectural integrity. Only retail stores up to 150 sq.m are permitted the frontage and as such along existing ground floors conversion of commercial activities is possible through renovation of dilapidated or abandoned buildings thus facilitating the two with the interplay of conservation and economic development.

Traditional practices of viticulture are intertwined with the local socio-economic structures to a great extent. The development of Avellino’s “Regia Scuola di Viticoltura & Enologia” made it possible not only to impart scientific knowledge but also to evaluate and improve viticulture. It is thus a dual function of quality improvement and skill preservation.

The conservation of and the introduction of these traditional practices are very important means of contributing to several SDG targets.

Traditional viticulture practices demonstrate all four circular economy principles: Resource Loop Closure in grape pomace utilization, Life Extension through heritage building adaptive reuse, Resource Efficiency in traditional farming methods, and Collaborative Consumption through cooperative wine production networks.

Preservation of traditional cultural, and heritage activities correspondingly focuses on SDG 11.4, whereas the sustainability of contemporary cultural activities which have been reexamined by them is the case at SDG 8.9, thus focusing on sustainable tourism that transcends local culture. Additionally, if you are interested in engaging in the scheme of Regia Scuola di Viticoltura & Enologia, and your formal intervention does contribute to Goal 4 (Quality Education) by assuring the knowledge transfer of traditional methods you will’ve been in the process successfully.

4.4. PESTEL Framework Application

The PESTEL analysis demonstrates the framework’s utility in systematically analyzing external factors affecting circular economy transitions in heritage contexts. This application illustrates how the integrated methodology can guide comprehensive assessment even when quantitative data is limited.

Political factors analysis through stakeholder interviews reveals complex regulatory landscapes: DOCG wine regulations create both constraints and opportunities for sustainable innovation. Interview data indicates that heritage protection laws (L.R. 16/2004) currently lack specific provisions for circular economy adaptations, creating policy gaps that municipal authorities struggle to address.

Economic factors assessment identifies resource efficiency as the primary driver for circular economy adoption among local businesses. Traditional cost structures in wine production create natural incentives for waste reduction and resource cycling. However, initial investment barriers for sustainable technologies remain significant for small-scale operations.

Social factors analysis reveals a strong cultural attachment to traditional practices, which stakeholder interviews indicate can facilitate rather than hinder circular economy adoption when framed appropriately. Community acceptance of innovations depends heavily on the demonstration of compatibility with cultural heritage values.

Technological factors present both opportunities and challenges: traditional wine-making techniques contain inherent circular principles, but integration with modern efficiency technologies requires careful planning to maintain authenticity. Infrastructure limitations in historic centers constrain some technological implementations.

Environmental factors create compelling drivers for change: climate change impacts on wine production are already observable, motivating producer interest in adaptive strategies. Traditional landscape management practices align well with ecosystem service provision concepts.

Legal factors reveal the need for regulatory framework adaptation: current heritage protection legislation focuses on preservation rather than adaptive sustainability, creating implementation challenges that require policy innovation.

This PESTEL application demonstrates how the framework can systematically analyze complex implementation contexts, providing a foundation for more detailed empirical studies.

The PESTEL analysis reveals how external factors either support or constrain the implementation of these four circular economy principles in Taurasi’s specific heritage context.

5. Discussion

5.1. Implementing Circular Economy in Historic Towns While Preserving Heritage

Our results show that, in historic small towns, the circular economy concept can be successfully implemented with a balanced approach that draws on traditional ways rather than replacing them. The Taurasi case illustrates the fact that circularity in winemaking is something that is inherent in the traditional methods that are being used and which could be applied more effectively rather than interrupted. Traditional techniques such as the “Alberata Taurasina” system are examples of earlier existing sustainable practices that have existed since the Etruscan era and are a proof of the statement of [

8], that cultural heritage can be the driving force for sustainable development. This approach aligns with regional innovation systems theory [

27], which demonstrates how local knowledge networks enable innovation while maintaining cultural authenticity.

The urban metabolism study has shown that the high fractionalization of farmland (97% of farms are less than 5 hectares) which is a problem, is also a good chance of circular economy introduction.

The urban metabolism study has shown that the high fractionalization of farmland (97% of farms are less than 5 hectares) which is a problem, is also a good chance of circular economy introduction. The main issue with fragmentation is the inefficient use of resources. However, it is also a way of maintaining traditional farming techniques that, according to [

12], are usually more resource-efficient and generate less waste. These results relate to [

13] who showed that sometimes the old ways in agriculture can actually help in modern circular economy practices.

5.2. Traditional Practices as Facilitators or Barriers in Circular Economy Transitions

Our study reveals that traditional practices have a double role in circular economy transitions. The example of how Taurasi DOCG wine production employs the benefits of established practices for sustainable development moving if appropriately applied, thus one’s knowledge can be passed on and channeled wisely through the “Regia Scuola di Viticoltura & Enologia” pathway which in turn demonstrates how the old wisdom can be perpetuated by incorporating the latest practice alongside traditional deeding.

Following the multi-level perspective on transitions [

28], our results demonstrate how niche innovations (traditional practices) can influence regime change through landscape pressures (sustainability requirements), while stakeholder engagement theory explains how knowledge circulation facilitates sustainability transitions.

Findings further support what [

4] already showed on the relevance of knowledge circulation for sustainability in system changes.

However, according to the PESTEL analysis, we can see that high walls are the reasons why the old ones stand solid. The current legislative set, specifically the SIAD, does not incorporate circular economy principles, which in turn shows how the traditional government structures can impede the transition efforts. This resonates with [

9] findings regarding the difficulties of reframing sustainable practices in the heritage contexts that they report.

5.3. Optimizing Stakeholder Engagement for Sustainable Transformation

The stakeholder analysis shows that there are three key points that can improve involvement in heritage-rich areas. In the first place, nontraditional projects most like wine cooperatives take into account the organizations that still have considerable influence over decisions; thus, these kinds of transitions need a bottom-up—rather than a top-down—approach by initially appropriating institutional structures. Secondly, the appearance of new stakeholders (consultants, environmental organizations) gives permission for the promotion of the introduction of innovative circular economy practices, respectful of traditional frameworks. Third, the lack of green energy production and recycling projects implementation at SIAD highlights a serious lack of coordination, a critical missing link in the relationship of the stakeholders at the organization regarding sustainability initiatives.

The results of this study add depth to the work of [

2] on stakeholder engagement. This is because they show that traditional hierarchies in historical towns can become facilitating factors for people’s involvement in the process of sustainability. The wine sector of Taurasi, with the informal networks being spotted there, is an example of how this cultural heritage (tradition) can be a prerequisite for the implementation of the circular economy initiatives, which already have the needed communication routes. In this evolving stakeholder landscape, it is increasingly necessary to think about ways digital technologies can assist those processes as well as technology-based ones while at the same time, preserving the essence of the cultural heritage.

5.4. Digital Transformation and Heritage Preservation

According to our study, digital transformation is an effective way to switch to a circular economy in historic small towns while still preserving cultural heritage. Taurasi serves as an example of the strategic implementation of digital technologies in three main domains: resource management, preservation of the heritage, and involvement of the stakeholders.

In the area of resource management, digital systems that provide monitoring make it possible to track the water and energy consumption of historic buildings in real time, and smart technologies optimize the organization of the wine production and distribution sectors. These solutions improve the efficiency of the operations as the findings of Taurasi’s wine producers show integrating digital monitoring with original production methods.

Digital platforms have reshaped how stakeholders participate in community processes and interact through knowledge sharing. These tools have been exceptionally helpful in the case of Taurasi because they make it possible for more people to participate in decision-making processes and at the same time keep traditional social networks.

Our study highlights that in historical towns, their specific context has to be respected in order to implement digital transformation.

5.5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This research sets up an Integrated Methodological Framework that combines the concepts of the circular economy and historic small towns’ urban revitalization programs. On the contrary, traditional approaches exhibit traditional practices as inconvenient pollution legacies that are, however, closely related to the decarbonizing intentions of sustainability transitions [

29].

These findings contribute to institutional theory in sustainability contexts [

30] by showing how cultural traditions can enable rather than constrain formal sustainability policies, while the global–local sustainability nexus literature [

31] explains how local heritage practices can effectively implement global sustainability goals.

Our circular economy methodology is thus a better fit, as it is flexible in that an ecoregion-wide context is needed in order for sustainability or circular products to be implemented.

Figure 6 is an Integrated Methodological Framework, which demonstrates how the dynamics between urban metabolism analysis, heritage preservation, and stakeholder engagement interrelate, traditionally practiced and by local networks. The theoretical development of this body of research introduces dimensionality to models already in use by incorporating cultural heritage as a positive asset, moving through the argument that constraining approaches dealing with traditional methods are useful. In addition, it proposes a systematic method for engaging stakeholders in heritage-rich environments and important connections between local traditional practices and global sustainability goals are uncovered.

Our Integrated Methodological Framework implies deeper theoretical issues through the use of these three areas. The first aspect of it is how urban metabolism theory is extended by showing one way historic small towns become models of efficiency rather than obstacles to resource efficiency. The second, and most important is that it gives a new and different view of stakeholder theory by bringing out the historical power structures and cultural networks that influence sustainable transitions. Third, the circular economy theory, which visualizes buying back resources, develops the urban heritages as the innovative and conflict-chilled channels for sustainability transitions in micro towns.

These new concepts that are placed beside the usual ideas that traditional practices and heritage preservation limit sustainable development, demonstrate that they have the possibility of also being useful for circular economy applications [

36,

37].

The practical impact of our research is especially important for policymaking that goes beyond one government level. At the municipal scale, our findings, therefore, imply that integrated approaches combining historical heritage preservation and sustainability objectives in urban planning instruments should be the necessary next step.

The Taurasi case illustrates the mechanism through which regional administrations can develop targeted initiatives that bolster traditional industries, and at the same time, facilitate the adoption of green practices.

Regional policy frameworks appear to be crucial because they can guide historic small towns towards a circular economy shift. Our research shows that coordination mechanisms need to be established between heritage protection and sustainable development policies.

At the national and European levels, the project shows the need for the adaptation of funding criteria which will reflect the specific problems of implementing a circular economy in heritage contexts. The case study exhibits how the EU rural development can be instrumental in aligning the local circular economy plans with the main cultural heritage at the same time. Hence, the implication is that the selection and development of concrete indicators and monitoring of frameworks for the historic small towns should be the priority, which are the towns’ distinctive characteristics and challenges recognition.

The policy implications are not only limited to specific governance levels but also inclusively the need for proper interactions in a multi-structural manner, which is a fact that is well understood that heritage conservation and sustainable growth of societies are intertwined. It was confirmed that policymakers who take care of a community by giving a framework, then balancing the needs for preservation and the new possibilities of innovation, as well as having sufficient deliberation amounts, to rural areas of this kind, would mean successful policy frameworks [

32].

This study contributes to sustainable development theory by illustrating how circular economy concepts can be successfully applied in environments with a rich heritage. Our results extend the present theoretical frames by proving that winning transitions call for inclusion with, and not substituting the old practices [

33]. The Taurasi case shows how knowledge transmission systems that are already in place can be capitalized on to the benefit of circular economy implementation while safeguarding cultural heritage.

Table 1 summarizes the outcome of our study from several primary aspects. Thus, it presents the approaches (of the analytical dimensions) necessary not only to point out the contributions and the conceptual insights but also to elucidate the experiences of application.

This Table shows that our work is all connected and can be applied in real life both in the academic and the practical sectors of circular economy in historic small towns.

5.6. SDG-Specific Metrics Integration

This framework explicitly connects circular economy indicators with measurable SDG targets, addressing the need for specific metrics in heritage contexts.

SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities):

- -

Target 11.4 is measured through the Heritage-Economy Integration Rate (HEIR);

- -

Cultural Heritage Resource Circularity (CHRC) tracks adaptive reuse effectiveness.

SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production):

- -

Target 12.2 is assessed via Traditional Practice Efficiency Index (TPEI);

- -

Heritage-Adapted Circular Material Use Rate (H-CMUR) measures resource efficiency.

SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth):

- -

Target 8.3 indicators focus on sustainable tourism development metrics;

- -

Local Resource Loop Closure (LRLC) tracks traditional industry revitalization.

5.7. Multi-Level Theoretical Contributions

Our findings contribute to theoretical understanding across multiple analytical levels. Micro-level contributions include demonstrating how traditional practices contain inherent circular principles that can be systematically leveraged. Meso-level insights reveal how regional governance structures and cultural networks influence sustainability transitions in heritage contexts. Macro-level implications show how global sustainability frameworks (SDGs) can be effectively implemented through locally adapted approaches that respect cultural specificity.

5.8. Historical Roots in Contemporary Sustainable Design

Our research findings demonstrate how historical urban planning principles in small towns like Taurasi naturally align with contemporary sustainable design frameworks, revealing that traditional settlement patterns contain inherent sustainability characteristics that can inform modern circular economy implementation strategies.

Taurasi’s traditional settlement patterns exemplify compact development principles that contemporary urban planners actively promote for sustainability. The historical concentration of residential, commercial, and cultural functions within the town center demonstrates efficient land use patterns that naturally minimize infrastructure requirements, reduce energy consumption for transportation, and preserve surrounding agricultural landscapes. This compact urban form, developed over centuries of organic growth, achieves the density and mixed-use characteristics that modern sustainable design seeks to recreate through conscious planning interventions [

33].

The town’s traditional building techniques showcase sophisticated local resource integration that significantly predates contemporary concerns about transportation-related emissions and supply chain sustainability [

34,

35]. Historical construction methods relied heavily on locally available materials such as stone, timber, and clay, creating buildings that are inherently adapted to local climate conditions while minimizing the environmental costs associated with material transportation. These practices demonstrate how traditional knowledge systems developed resource-efficient solutions that contemporary green building standards now seek to emulate through local sourcing requirements and reduced embodied energy targets.

Historical social structures in Taurasi support collaborative resource management at the community scale, embodying principles that contemporary sustainable design recognizes as essential for effective circular economy implementation [

38,

39]. Traditional cooperative systems for agricultural production, shared infrastructure maintenance, and collective decision-making create the social capital necessary for community-scale sustainability initiatives. These neighborhood-scale collaborative systems demonstrate how historical governance patterns can provide institutional foundations for modern resource sharing, waste reduction, and collective environmental stewardship programs.

The adaptive infrastructure demonstrated by Taurasi’s heritage buildings exemplifies long-term design thinking that contemporary sustainable design increasingly values. Traditional buildings have successfully accommodated changing uses, technologies, and social needs over centuries while maintaining their structural integrity and cultural significance. This adaptability reflects design principles that prioritize durability, flexibility, and resilience—characteristics that modern sustainable design recognizes as essential for reducing environmental impacts over building lifecycles. These historical examples provide concrete evidence that sustainable design principles are not merely contemporary innovations but represent the rediscovery and systematic application of traditional knowledge systems that successfully balanced human needs with environmental constraints over extended time periods [

36,

37].

These historical roots provide robust foundations for contemporary circular economy implementation that respects both cultural heritage preservation and environmental sustainability objectives, demonstrating that traditional and modern approaches can be mutually reinforcing rather than conflicting [

38,

39].

6. Conclusions

This study has investigated the execution of circular economy principles in historic small towns through the case of Taurasi, formulating a new Integrated Methodological Framework that uses urban metabolism analysis, stakeholder engagement, and heritage preservation. According to our research, even historic small towns can also move toward implementing a circular economy and at the same time preserve their cultural heritage, if the traditional practices are considered as a tool rather than a problem.

The Taurasi wine production system is an example of how traditional practices can be an extremely good way to transfer to a circular economy. The study presents the evidence that established manufacturing methods of agriculture encapsulate sustainability’s concept, which can be developed with the help of modern technology. The DOCG wine production system is not only an ideal way of preserving traditional knowledge but also, through the adoption of a sustainable perspective, a way to innovate traditional practices. Our results contribute to the theory of sustainable development by demonstrating that existing best practices in circular economy application to historic settings include integration with cultural traditions, engagement with the established network of stakeholders, and the modification of governance frameworks that are able to reconcile preservation together with innovation. The study of Taurasi urban metabolism and stakeholder relationships discovers the point that these conventional resource management systems may make their way to green development, hence, becoming a sustainable development route.

The study also has major practical applications for the policymakers and the local authorities in the same contexts. The research found that successful circular economy transitions are only possible if the local cultural heritage, stakeholder relationships, and traditional governance structures are regarded properly. Taurasi is a case of EU rural development funding being successfully linked with local circular economy initiatives through cultural heritage preservation.

Our findings both align with and extend existing literature on circular economy implementation in small towns. Similar to [

4] regarding stakeholder engagement importance, our research confirms that community networks are crucial for successful transitions. However, our study extends their findings by demonstrating how traditional cultural networks can be leveraged rather than replaced.

Our results contrast with conventional urban metabolism studies [

6,

7] that focus primarily on large cities, showing that small historic towns require fundamentally different analytical approaches. While [

12] emphasized quantitative flow analysis, our research demonstrates that qualitative heritage assessment is equally important in historical contexts.

Regarding heritage preservation, our findings align with [

8] in demonstrating circular economy compatibility with cultural heritage, but extend their port city focus to rural wine-producing contexts. Unlike [

21] who emphasized building-level interventions, our research reveals the importance of landscape-scale traditional practices.

This research makes unique contributions by (1) developing the first integrated framework specifically for historic small towns, (2) demonstrating traditional practices as circular economy enablers rather than barriers, and (3) providing empirical evidence for heritage-sensitive circular economy implementation.

Several limitations of this study have to be indicated. Firstly, though the single case study approach has the inner perspective of Taurasi’s transition to a circular economy, it only is a limitation to the generalizability of findings to other historic towns with different cultural and economic settings. Secondly, the data availability constraint that is common to historic small towns was also a factor in the scope of our study, especially, as regards the quantitative metrics of resource flows and long-term economic trends. Thirdly, the study period of the research being limited to 2024 may not be able to exhibit the long-term transition and the entire cycle of circular economy initiatives.

Finally, the stakeholder analysis, albeit extensive, may have failed to consider the informal ties that actually play a major role in the process of decision-making in historic small towns. The last point regards the sector of wine that supposes the attention of the research, which, although it indeed intends to develop a case for Taurasi, risks limiting the translation of the formulated hypothesis to historical locations featuring different economic types.

The results of the study indicated that there are many promising future research areas. First, comparative studies among different historic centers in regions and countries might be of help to validate our Integrated Methodological Framework as well as identify the local elements affecting the circular economy transition. Second, longitudinal analysis over five to ten years could bring about an understanding of how traditional practices are maintained in sustainability transitions and how communities grow and adapt to change through time. Third, research ought to be conducted to study whether digital technologies can support the circular economy transitions while maintaining heritage values.

Fourth, future studies may delve into the financial schemes and business models that facilitate sustainable transitions in heritage-rich settings, which would include new funding ideas and public-private partnerships. Fifth, research can be directed towards the formation of standardized metrics and indicators specifically meant for the measurement of the circular economy implementation in historic small towns. Besides, future studies should talk about how policy frameworks help or play a barrier to circular economy shifts in historical settings. The main concern should be how the EU directives and the national policies could be more effective in the preservation of the cultural heritage and at the same time, supporting the local initiatives.

The study, in fact, illustrates that historic small towns are “green laboratories”, that show how traditional knowledge and digital technologies can preserve cultural heritage and achieve thus sustainable goals.

6.1. Future Research Framework and Data Collection Protocols

This Integrated Methodological Framework provides the foundation for comprehensive empirical studies in historic small towns. Future researchers applying this framework should follow these specific data collection protocols:

Phase 1: Quantitative Urban Metabolism Assessment

Establish baseline resource flow measurements using municipal utility data, waste management records, and energy consumption monitoring.

Implement standardized measurement protocols for material inputs/outputs in key economic sectors.

Develop small-scale monitoring systems appropriate for historic town infrastructure constraints.

Phase 2: Comprehensive Stakeholder Network Analysis

Conduct structured surveys with representative samples from all stakeholder categories identified in this framework.

Apply social network analysis software (e.g., Gephi, UCINET) to map quantitative relationships.

Implement longitudinal tracking of stakeholder collaboration outcomes.

Phase 3: Economic Impact Assessment

Establish cost-benefit analysis protocols for circular economy interventions.

Develop heritage-sensitive economic indicators that account for cultural value preservation.

Create comparative benchmarking systems with similar historic towns.

Phase 4: Policy Integration Analysis

Systematic analysis of regulatory frameworks using legal document analysis.

Assessment of policy implementation gaps through institutional interviews.

Development of policy recommendation frameworks specific to heritage contexts.

Phase 5: Indicator Measurement Protocols

Future researchers should implement systematic measurement of heritage-adapted circular economy indicators:

- -

Heritage-Adapted Circular Material Use Rate (H-CMUR):

- -

Establish baseline measurements using local material flow data;

- -

Account for traditional building materials and construction methods;

- -

Integrate heritage preservation requirements in efficiency calculations.

- -

Traditional Practice Efficiency Index (TPEI):

- -

Implement tracking through traditional sector resource audits;

- -

Document resource flows in traditional economic activities (wine production, agriculture);

- -

Measure waste reduction and resource cycling effectiveness.

- -

Cultural Heritage Resource Circularity (CHRC):

- -

Develop assessment protocols through heritage building utilization surveys;

- -

Track adaptive reuse success rates while maintaining cultural authenticity;

- -

Monitor integration of circular practices with heritage preservation.

This research demonstrates that Integrated Methodological Frameworks specifically designed for heritage-rich contexts are essential for advancing circular economy implementation in historic small towns. The integrated approach presented here addresses the unique challenges of these environments while providing a replicable methodology for systematic empirical investigation.

6.2. Framework Transferability and Adaptation Guidelines

This Integrated Methodological Framework can be effectively adapted for application in other historic small towns through a systematic three-phase contextualization process that respects local specificities while maintaining analytical rigor.

The initial context assessment phase requires researchers to thoroughly understand the local heritage and economic landscape. This involves identifying the dominant traditional economic activities that serve as the cultural and economic backbone of the community, analogous to wine production in Taurasi’s case. Researchers must map existing social networks and governance structures to understand how decisions are made and how stakeholders interact within the local context. Simultaneously, it is essential to assess both heritage constraints that may limit certain interventions and heritage opportunities that can be leveraged for circular economy implementation. This phase concludes with a comprehensive evaluation of available data sources and collection feasibility, recognizing that historic small towns often face data availability challenges.

The methodology adaptation phase focuses on tailoring the analytical framework to local conditions. Stakeholder categories should be modified based on the specific economic structure of each town, ensuring that all relevant actors are included while respecting local power dynamics and cultural hierarchies. The PESTEL analysis factors must be adapted to reflect regional policy contexts, as regulatory frameworks and institutional support systems vary significantly across different jurisdictions. Heritage assessment criteria require careful adjustment to local architectural styles and cultural characteristics, as what constitutes heritage value differs substantially between regions and cultural contexts. Finally, data collection protocols should be scaled appropriately to match available resources and local institutional capacity.

The indicator localization phase ensures that measurement systems reflect local realities and values. Circular economy indicators must be adapted to the specific economic activities that characterize each historic town, moving beyond generic metrics to capture locally relevant resource flows and efficiency measures. Heritage-specific metrics should be developed that resonate with local cultural values and preservation priorities, ensuring that sustainability assessments align with community heritage objectives. Establishing baseline measurements using available local data provides the foundation for monitoring progress, while creating monitoring protocols appropriate to local institutional capacity ensures the long-term sustainability of the assessment framework. This systematic approach enables researchers and practitioners to apply the methodological insights from Taurasi while respecting the unique characteristics and constraints of their specific historic small-town contexts.

6.3. Policy Implementation Guidelines

Policymakers at different governance levels can effectively adapt our research findings to develop comprehensive policy frameworks that support circular economy transitions in heritage-rich contexts while respecting cultural preservation requirements.

At the municipal level, local authorities should integrate heritage-circular economy compatibility assessments directly into their urban planning processes, ensuring that sustainability initiatives are evaluated not only for their environmental and economic benefits but also for their potential impacts on cultural heritage preservation. This requires developing heritage-sensitive funding criteria for sustainability projects that recognize the additional costs and complexities associated with working within historic contexts, while providing appropriate financial support for initiatives that successfully balance innovation with preservation. Municipal governments should also create stakeholder engagement protocols specifically adapted to local cultural networks, recognizing that traditional power structures and communication patterns in historic small towns may differ significantly from those in larger urban centers, and that effective engagement requires understanding and working within these established social frameworks.