Abstract

Achieving organizational efficiency requires the selection of an appropriate operating model. To date, no objective indicators, methods of measuring, or criteria for evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of forest management organizations have been developed. In the heterogeneous forest management of the European Union (EU), multiple objectives and functions—from production to social and ecological services—coexist at regional and national levels. This study provides an overview of the organizational and legal forms of EU forestry, taking into account environmental conditions, ownership structures, and the role of the forestry sector in national economies. The legal information of EU countries on forest management was verified. We examine the impact of the entity’s organizational and legal form on the implementation of sustainable forest management and the objectives of the New EU Forest Strategy 2030, particularly in terms of absorbing external capital for forest protection and climate-related activities. Joint stock companies, public institutions, and enterprises are the most relevant. The private sector is dominated by individual farms, associations, chambers of commerce, and federations. A clear trend toward transforming state-owned enterprises into joint-stock companies and expanding their operational scope has been confirmed. Multifunctional forest management is practiced in both state and private forests. Economic efficiency, legal and property liability, and organizational goals depend on the chosen organizational and legal form.

1. Introduction

The ownership structure of forest land is the result of the interplay between natural forestry conditions, land-use practices, political situations, and demographic factors over extensive temporal and spatial scales [1]. Research into socio-demographic and socio-economic variables indicates that these factors significantly influence forest management; however, they do not fully capture the interdependencies arising from the pluralization of social life and the individualization of forest owners [2]. These dynamics have led to the introduction of diverse organizational and legal forms for conducting forest management in both public and private forests. In the EU’s “old” member states, the forest ownership structure is characterized by a higher share of private forest ownership compared to countries where state ownership predominates.

Private forest ownership has traditionally been linked with small-scale agriculture [3], although this association is gradually weakening, leading to further fragmentation or consolidation of forest properties [4]. These changes affect management capacity [5] and raise concerns regarding the stewardship of private forests [6]. Institutional changes in Central and Eastern Europe, evolving lifestyles of forest owners [7], diverse requirements for forest management [8], and variations in property-rights regimes have implications for implementing international environmental protection policies and underscore the need for tailored policy instruments in rural development, the bioeconomy, climate-change mitigation, and nature-conservation strategies [9].

The utilization of natural resources is of interest across multiple research disciplines [10]. Forest management involves fulfilling competing functions—commercial (timber production) and non-commercial (social and ecological) [11]. Evaluating and enhancing efficiency—understood as the ratio of outcomes to inputs [12]—is a key determinant of organizational development [13]. Forestry is grounded in a specific paradigm of principles, concepts, and assumptions regarding forest ecosystem functioning and responses to management interventions [14]. Entrepreneurial activity significantly influences the realities of forest management [15], yet a unified methodology for measuring, assessing, and identifying factors affecting forest-management organizations remains undeveloped. Management theory defines organizational effectiveness as an enterprise’s ability to adapt operationally and strategically to environmental changes and to use resources effectively to achieve set objectives [16,17,18].

Sustainable forest management [19], which sets explicit expectations for forest managers to provide a range of ecosystem services [20,21], confronts contemporary organizations with substantial market challenges [22]. Adhering to sustainable development principles entails rational resource use [23,24] and the search for new, efficient management forms [25]. Economic instruments employed by EU member states exhibit significant variation in forest-management approaches and financial outcomes, tailored to national strategies and action plans [26]. Among these instruments, the organizational and legal form of an entity is pivotal. Its selection during establishment and subsequent development stages carries binding contractual implications, defines representation mechanisms, impacts decision-making processes, and influences access to external financing. Therefore, this decision must balance the objectives and nature of activities undertaken, as later transformations can result in complex and costly consequences.

Forests deliver multiple social functions: they are reservoirs of biodiversity, sources of economic raw materials, and play crucial roles in climate change mitigation by sequestering carbon and supporting water retention. Forestry faces numerous challenges—including climate change, growing demand for wood and biomass energy, and forest health threats—necessitating that organizational and legal structures in EU member states adapt to a dynamically changing context. Models of forestry organization in the EU, legal frameworks dictating management styles, information flows, and decision-making processes are all critical. Increasing emphasis on the non-commercial functions of forests (social, biodiversity conservation, and climate regulation) raises operational costs for forest holdings across EU countries. In this context, external capital financing can play a decisive role in achieving climate objectives and ensuring forest resilience amid changing climatic conditions.

The aim of this study is to present an analysis of the organizational and legal forms of forest-managing entities in EU countries, focusing on their capacity to fulfil climate-protection and biodiversity-conservation functions. The research scope encompasses the examination of legal aspects influencing forest management across EU member states and the impact of forest ownership structures on the implementation of sustainable forest management in light of the challenges facing European forestry, particularly regarding the mobilization of external capital for climate-related goals. The article fills the research gap of fully identifying the ownership structure and form of forest management in the EU. Verification of the forms of ownership provides important information in terms of influencing changes in forest management. The acquired information presenting the share of public–private ownership of EU forests has a direct impact on the indicated directions and legal forms of adapting forests to the new EU requirements and ensuring sustainable development of the forest management sphere [27].

The aim of the work is to analyze the organizational and legal forms of entities managing forests in EU countries, with particular emphasis on their ability to implement the function of climate protection and biodiversity. Articles refer to the current legal, organizational, and financial status of these entities and their ability to adapt to the challenges of sustainable development. The following research questions were asked in the work: What are the basic organizational and legal forms of entities managing forests in EU countries, and what factors shape them? How does the legal form affect decision-making autonomy and the possibility of obtaining external financing, especially for climate goals? How does the structure of forest ownership determine the implementation of multifunctional forest management goals?

The analysis showed that the organizational and legal form of forest management entities affects their ability to obtain external financing, especially for purposes related to climate protection and biodiversity. In addition, the forest ownership structure determines access to public and private capital, which is of significant importance for the implementation of sustainable forest management in EU countries.

We assessed the availability of financial instruments for different organizational and legal forms—including access to EU funds, bank loans, and bond issuance—and verified the accessibility and potential utilization of these financing sources by forest-managing entities operating under varying legal regimes. The research task undertaken in the article is to assess the impact of forest land ownership on potential adaptation to the challenges facing European forestry [28].

2. Literature Review

Forest management in Europe has been shaped by reforms in the 19th century, which introduced planning and protection of forest resources [1,28]. In the 20th century, the forest sectors of countries developed, adapting to social and ecological challenges [28,29]. An example of a modern institution is the Finnish Metsähallitus, combining commercial activities with nature conservation [30]. State forest management organizations (SFMOs) play a key role in the European forest sector, managing almost half of the forests in the region [31]. In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, state forestry companies dominate, which are slowly moving to market mechanisms [32,33,34]. The growing role of capital companies, such as the Swedish Sveaskog, highlights the tendency to combine business with public functions and environmental protection [35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. In many EU countries, forest management is carried out by public institutions linked to the state administration, implementing forest policy and biodiversity protection, often in centralized or decentralized models (e.g., France, Spain, Belgium) [42,43,44,45,46]. These models vary in the degree of regional flexibility and coherence in achieving national goals. The financing of sustainable forestry relies on public funds, commercial activities, and increasingly important financial instruments such as green bonds supporting EU climate and environmental goals [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. The EU taxonomy and the European Green Deal direct private capital towards green investments, which increases the availability of funds for forest enterprises [51,52,53,57,58,59,60,61]. Regional differences in capital absorption and the need for dialogue between the financial and forest sectors indicate challenges in obtaining and effectively using external funds [61,62,63,64]. Mishenina et al. [25] advocate for a wider use of modern management—public–private partnership (PPP) as a promising and strategic direction of environmental and economic policy in the forest sector, in the conditions of state and communal forest ownership. They believe that it can help to expand the investment potential of forestry and solve budgetary and financial problems. Moreover, technological and managerial innovations are becoming crucial for the sustainable development of the sector in the face of climate change and demographic pressure [65,66,67,68,69].

3. Materials and Methods

The development of advanced analytical tools and research methods is the basis for building and systematizing knowledge in management sciences [70]. Comparative analysis, the most commonly used method in the study of volumes and financial relations, is preferred due to the possibility of isolating and defining the studied features [71]. Comparative analysis of forest ownership forms in the EU is needed to understand differences in governance and adapt policies to country-specificities. This helps to better support climate protection and sustainable development goals.

The study analyzed the legal conditions shaping forest organizations in the EU countries, using a comparative analysis of national legal systems (organizational and legal models) regulating the forest law of the Member States. A review of literature and legal acts on the ownership structures of forests and the organizational and legal forms of forest entities in the EU was conducted. These forms were classified by country, type of ownership, forest area, and legal form, creating a typology of organizational and legal structures. Legal forms of forest management were identified, and their distribution in individual EU countries was analyzed. The authors used research methods typical for the analysis of legal practice in forestry. These methods, although widely used in management sciences and comparative analyses, are also suitable for examining legal systems and regulations. Inductive reasoning and synthetic analysis allowed us to identify common features and differences in legal and organizational solutions shaping forest management practice. A review of literature and legal acts allowed for a reliable assessment of the applicable legal norms and their implementation in practice.

This approach is purely analytical, focusing on the synthesis and interpretation of secondary data and a review of existing legal regulations and scientific literature. No empirical research or quantitative analyses were conducted in the work, which results from the assumption that the study focused on the systematization of knowledge and comparison of organizational and legal models.

The concept of a “common statutory paradigm” refers to a set of basic assumptions, principles, and legal frameworks characteristic of the legal systems of the EU Member States in the field of forest management. It includes common goals, such as sustainable management of forest resources, environmental protection, and regulations on the ownership and use of forests. This paradigm is a reference point for the comparative analysis of forest legislation, enabling the identification of similarities and differences in regulations and management practices.

The study selected indicators that allow for a comprehensive assessment of the organizational and legal forms of forest management in EU countries. The forest ownership structure was taken into account, with particular emphasis on the share of public and private ownership, because different ownership models affect management strategies and access to financing. The organizational and legal forms of managing entities, which determine their decision-making autonomy and the effectiveness of implementing forest functions, were also analyzed. An important element was the assessment of access to external financing, including EU funds, bank loans, and bond issues, which are important for achieving climate and sustainable development goals. Additionally, the area of managed forests was taken into account because the scale of forest areas affects the effectiveness of management and protective measures. These indicators were selected due to their significant theoretical and practical significance in the context of sustainable forest management and the adaptive capacity of entities to growing environmental and economic challenges.

Data Sources

Secondary data sources included statistical reports from Eurostat, Forest Europe, FAO, UNECE, OECD, EEA and the European Commission; legal acts (acts, directives, regulations); certification systems; forest managers’ charters; national and international reports; scientific literature; websites of ministries, forestry institutions and sectoral organizations.

Methods used include the following:

- Inductive reasoning: inferring general trends and phenomena from detailed data on the organizational and legal forms of EU forestry entities, enabling an assessment of the functioning of the organizations, identifying common features and distinguishing elements at the EU level. Synthetic analysis: examining the common features of different organizational forms in forestry in order to classify them into the main categories—public institutions, state-owned enterprises, joint-stock companies, associations, chambers of commerce, federations, and individual holdings—and providing detailed characteristics of each of them.

- Literature review: analysis of scientific publications, sectoral reports, and books on forest management organization in Europe in order to establish a theoretical and practical basis.

- Process analysis: assessing forest management processes within sustainable and multifunctional forestry.

- Synthesis of findings: integrating the results of the analysis to assess the impact of organizational forms on the effectiveness of forest management in EU forests and to explain the relationship between organizational structure and the effectiveness of forest policy implementation.

Policy documents from 1992 to 2025 were collected mainly from official websites of European Union countries and the World Open Access Database. They were supplemented with data resources collected from the official websites of relevant ministries, departments, and organizations related to forestry and environmental policy

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Legal Frameworks for Forest Management in the EU and Member States

Legal instruments [72] are fundamental tools for governing, conserving, and sustainably utilizing forest resources at the level of individual EU countries. Despite the EU’s regulatory stance on environmental matters [73], it has yet to adopt a common forest policy [74,75], and EU treaties do not directly reference forestry [76,77]. Forests and related policies are not listed among the shared competencies under the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) [78]. Under primary EU law, execution of forestry-related provisions is largely delegated to member states [79], with no standardized legal framework imposed across the Union [80]. EU legislation treats forestry topics within the broader contexts of environmental protection and agriculture [81], and the Common Agricultural Policy remains the principal source of EU funding for forest-related activities [82]. Climate, energy, and bioeconomy policies impose cross-sectoral obligations on forests [83].

The formal absence of a unified EU forest mandate [74] is offset by an array of regulatory acts, directives, guidelines, and strategies aimed at forest conservation [84], which serve as long-term policy frameworks for member states [85,86]. Legally binding instruments with enforcement mechanisms include the Habitats Directive [87], Birds Directive [88], Renewable Energy Directive [89], Regulation on the marketing and exports of deforestation-related commodities [90], the EU Solidarity Fund [91], the LIFE Programme [92], the LULUCF Regulation on greenhouse-gas accounting [93], the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation [94], and the Deforestation-free Products Regulation [95]. In addition to binding legislation, the EU issues strategic documents—such as its forest strategies [96,97]—which embed key concepts (biodiversity, climate change, forest protection) to shape the European forestry vision. Forest Europe, a pan-European ministerial-level forum, remains a leading political initiative. Other relevant legal acts include the Public Procurement Directive [98], VAT Directive [99], and Emergency Support Regulation [100]. Over recent years, there has been a shift toward favouring regulations over directives [83], though the EU’s forest-law landscape remains fragmented across multiple documents without a single, cohesive legal instrument [101].

National and international forestry policies and instruments are extensively reflected in the forest legislation of European countries, with shared objectives—sustaining forests, facilitating timber production, and regulating public access—enshrined in key laws: Austria’s Forest Act [102], Bulgaria’s Forests Act [103], the Czech Forest Act [104], Croatia’s Forestry Law [105], Cyprus’s Forestry Law [106], Estonia’s Forest Act [107], Finland’s Forest Act [108], France’s Forest Code (1979) [109] and the Forestry Orientation Law (2001) [110], Germany’s Federal Forest Act (1975) [111], Hungary’s Forest and Forest Protection Act [112], Lithuania’s Law on Forests [113], Poland’s Forest Act [114], Slovakia’s Forest Act [115], Slovenia’s Forestry Law [116], Sweden’s Forestry Act [117], Romania’s Forest Code [118], Ireland’s Forestry Act [119], Belgium’s Forest Code [120], Denmark’s Forestry Act [121], Greece’s Forestry Law [122], the Netherlands’ Nature Conservation Act [123], Luxembourg’s Forest Act [124], Spain’s Forestry Law [125], Portugal’s Forestry Law [126], Malta’s Forests and Trees Protection Act [127], Italy’s foundational Royal Decree [128], and Latvia’s Forestry Law [129].

In newer EU member states, legislative initiatives to transition from a raw-material extraction model toward legally enshrined sustainable forestry emerged in the early 1990s. Additional statutes influencing forestry include land-tax laws [130], VAT legislation [131], disaster-relief regulations [132], and multi-tiered environmental governance frameworks reflecting EU–member state relationships [133].

Introducing new legislation to fulfil national and international commitments on forest and biodiversity protection has driven transformations across Europe’s forestry sector. Voluntary certification schemes have become instrumental in establishing regional and international standards for sustainable forest management—integrating environmental, social, and economic values [134,135] and sometimes complementing or superseding traditional policy tools [136]. The most prevalent systems are the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), emphasizing environmentally and socially responsible management [137], and the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), favoured in countries seeking a balance between timber production and environmental protection without overly stringent requirements. FSC follows its own guidelines, whereas PEFC adapts to local legal frameworks [138].

Consequently, the once-clear division between Western European and former socialist forestry systems has become less pronounced. National legislation also shapes private forestry by defining owners’ rights and responsibilities. However, the scope of these rights varies regionally, granting Western European owners greater autonomy in silvicultural and utilization decisions, while Eastern European countries often impose stricter oversight [139].

In Table 1, we present key forestry-sector indicators that facilitate comparison of legal frameworks and environmental protections across EU countries.

Table 1.

Comparison of selected forestry and environmental sector indicators in EU countries. (Source: FSC [92], PEFC [93], Naturland [140], Eurostat [141,142], EUR-Lex [143], EEA [144], EC [145]).

National legislation in EU Member States applies uniformly to all forms of forest ownership, while guaranteeing the statutory right of entry to publicly owned forests; access to private forests remains contingent on the owner’s consent. The FSC certification system has been adopted throughout the Union, whereas the PEFC scheme is absent in Croatia, Greece, Lithuania, Malta, Hungary, and Cyprus. Their respective uptake varies widely: across the EU as a whole, some 45% of forest area is PEFC-certified, versus roughly 24% under FSC. At the national level, PEFC predominates over FSC in Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, France, Spain, Luxembourg, Latvia, Germany, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Italy; in all other Member States, FSC holds the larger share. Countries where PEFC dominates also register the highest numbers of infringement proceedings for environmental breaches and, despite comparatively high environmental-protection expenditures, tend to fall further short of their greenhouse-gas reduction targets.

The forestry sector’s contribution to national GDP is substantial in Austria, Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, and Germany, where protected areas account for approximately 30–40% of each country’s land area. By contrast, in Cyprus, Malta, Belgium, Denmark, Greece, and Luxembourg—where forestry plays a marginal or negligible economic role—environmental-protection budgets are below recommended thresholds, and protected-area coverage ranges between 14% and 38%.

Across the EU, a shared statutory paradigm of permanently sustainable forest management, sustainable forest management, which implies that the use of forests is to be compatible with their ecological, economic, and social potential, and at the same time, must ensure their long-term sustainability and functionality. Together with widely varying sectorial GDP shares and certification regimes, it shapes each Member State’s progress toward its climate-protection goals. The selection of organizational and legal form for conducting forest management remains beyond the scope of EU legislative competence, preserving full autonomy for national authorities the Union, a shared statutory paradigm of permanently sustainable forest management, together with widely varying sectoral GDP shares and certification regimes, shapes each Member State’s progress toward its climate-protection goals. The selection of organizational and legal form for conducting forest management remains beyond the scope of EU legislative competence, preserving full autonomy for national authorities.

4.2. Characterization of Organizational and Legal Forms of Forest Management in the EU

Forest-management entities in the EU combine commercial production and marketing functions with the delivery of non-market services (e.g., recreation, biodiversity protection) on either a fee or pro bono basis. Ownership divides them into public and private sectors; their multi-dimensional operations are determined by their organizational and legal form, which prescribes their legal personality, governance and supervisory architecture, liability framework, accounting and tax regimes, and minimum share-capital requirements. This legal form informs their strategic outlook, growth potential, policy execution, and investment priorities.

A comprehensive review of EU forestry governance structures identifies two principal sectors and their key legal manifestations: private and public. As a result of the analysis of the existing forms of ownership, the following sectors were separated: state forestry enterprise, joint-stock company, limited liability company, public agency, association, chamber of commerce, and private forest ownership.

4.2.1. Public Sector

- State Forest Enterprises—autonomous, self-governing, self-financing legal entities under full or majority state control, established by ministries or other public bodies, answerable alone for their obligations, operating under civil and forestry law plus their own statutes, and governed internally by workforce councils and directors [146,147,148]. As economic actors of national importance, they are subject to Articles 101, 102, and 106 of the TFEU (competition rules and public-service exemptions) and to the State-Aid Transparency Directive [78,149]. Many undergo commercialisation or privatization processes [150,151]. Their performance hinges on domestic political dynamics and the efficacy of supporting public institutions [152]. Strengths include integrated administration, clarity of command, financial stability, and strong public brand recognition; weaknesses encompass political interference [153], opaque employee rights, lack of independent audit, complex regulations, and weak incentives for cost control or revenue generation. Profitable enterprises enhance public finances; loss-making or heavily indebted ones may require state recapitalisation [154].

- State-Owned Capital Companies—joint-stock (e.g., S.A., S.p.A., A.G.) or limited-liability (e.g., GmbH, SRL) entities in which the state is sole or majority shareholder, governed by EU directives covering shareholder rights [155], financial transparency [156], non-financial disclosures [157], company-law simplification [158], and merger control [159]. These companies combine private-sector governance models with public-sector objectives.

- Public Agencies/Institutions—administrative bodies of central or regional government, endowed with executive and regulatory powers, organizationally distinct and acting on behalf of the state [160,161,162]. They develop and enforce forest policy, administer public funding for conservation, sustainable harvesting, and innovation, and perform advisory or coordinating roles under ministerial oversight. Particularly prevalent in “old” Member States with limited state forest ownership, such agencies are integral to implementing the EU Forest Strategy 2030 [97].

4.2.2. Private Sector

- Individual Forest Holdings—family or privately owned estates combining timber production with ancillary services.

- Associations and Federations—membership organizations representing private owners, providing collective advocacy, technical assistance, and market facilitation.

- Chambers of Commerce—semi-public bodies that support forestry enterprises through training, market access, and regulatory guidance.

- State Forest Enterprise

By design, a state forest enterprise pursues economic returns within a broader public-service mandate. It enjoys extensive operational autonomy, though its strategic direction is often influenced by the government’s forestry policy cycle [163,164]. Financial security from the state can dampen commercial incentives, while strong local structures ensure integration with regional socio-economic contexts [165]. Large natural-resource endowments and infrastructure position these enterprises as key providers of ecosystem services, though engagement with local stakeholders remains challenging [166]. They face systemic risks from climate-driven changes in forest productivity [167] and from changing interpretations of “sustainable forest management” across the EU.

- Joint-Stock Company

As legally and financially independent entities, joint-stock companies facilitate risk diversification, strategic governance, and capital-market financing (equity, bonds) [168]. Their governance model—comprising a management board, supervisory board, and shareholders’ assembly—ensures transparency and accountability. The European Company (SE) framework [169] enables cross-border consolidation under a single statute, enhancing operational scale and capital-raising capacity.

- Limited-Liability Company

Limited-liability companies (e.g., sp. z o.o., S.L., SARL, SRL, B.V.) offer simplified formation procedures and lower capital thresholds [170], at the cost of restricted capital-market access and potentially protracted liquidation processes [171]. Their internal governance is less rigid than that of joint-stock companies, making them well suited to small- and medium-sized forestry ventures.

- Public Agency

Public agencies wield delegated authority to regulate and implement forest policy, issue and enforce legal standards, and allocate public funds for conservation and sustainable-use measures. Reporting to ministerial bodies, they often coordinate multi-level governance frameworks, balancing national objectives with regional autonomy [160,161,172,173,174]. Their central role in delivering the EU Forest Strategy 2030 [97] underscores their importance in achieving Union-wide sustainability and climate goals.

- Association

An association is a social organization established by any group of persons to represent the collective interests of its members before public authorities or within any other scope defined in its statutes. It operates on a non-profit basis, founded on voluntariness, permanence, and self-governance. Its funding derives primarily from membership dues. An association maintains its own organizational structures and work programme, relying chiefly on the voluntary efforts of its members. Its influence depends on the size, internal cohesion, and expertise of both membership and leadership [173,174]. It may adopt internal regulations governing its activities. Legal personality is acquired upon registration, which requires a statute adopted by at least seven founding members and submission of an application by the board. The governing bodies of an association are the general assembly of members, the board of directors, and a supervisory or audit committee [175,176].

In the forestry sector of EU Member States, associations support private forest owners, shape public perceptions of forests and forestry [177], and act in a consultative capacity to assist with the implementation of legal regulations. They participate in formal consultation processes and back a wide range of forest-protection and sustainable-development initiatives under EU forest policy. Their organizational status enables them to facilitate access to rural development and forest-protection funds under EU regulations [178], acting as representatives of forest owners. Associations can exert real influence on EU policy and decision-making—far beyond mere advisory roles—by mobilizing their members, providing technical expertise, and coordinating joint advocacy efforts at national and EU levels.

- Chamber of Commerce

A chamber of commerce is a self-governing economic organization that represents the business interests of its member enterprises before public authorities. Its mission is to advance the common good and the specific needs of its members to facilitate their commercial activities [179]. A chamber possesses legal personality. Its governing organs consist of the general assembly of entrepreneur-members, an executive board, and an audit commission. Funding comes predominantly from membership fees, though chambers may also engage in economic activities. To establish a regional chamber (covering a single province), at least 50 founding enterprises must petition its creation; for a wider territorial mandate, at least 100 founders are required.

Membership regimes vary across Europe: in countries such as France, Italy, Croatia, and Luxembourg, chamber membership is compulsory, whereas in Finland, Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia it is voluntary. Chambers do not generate profit in the strict sense; however, their socially responsible activities can yield indirect and residual economic benefits by improving market conditions for members [180]. Their competencies include issuing opinions on draft legislation affecting business operations, participating in legislative preparation, and evaluating the implementation and functioning of existing legal provisions. Under the EU Services Directive [181], chambers can provide advisory and business services. By organizing training courses, workshops, and conferences, they help enterprises adapt to evolving regulations, innovate, and enhance competitiveness. At a chamber’s request, a national government may delegate certain administrative tasks to it [182]. Although chambers of commerce are relatively rare in the EU’s private forestry sector, they can support sustainable forest management, represent private forest-owner interests, foster collaboration with environmental NGOs, mediate legal disputes, and raise public awareness of forestry’s societal value.

- Private Forest Ownership

Private forest ownership encompasses a diverse category—including individuals, family groups, community cooperatives, business enterprises, private religious or educational entities, non-governmental organizations, nature-conservation associations, and other private bodies [183]. Organizational forms such as individual forest holdings (family co-operatives), associations, unions, federations, and corporate holdings are often hybrids or conglomerates of the above legal types. They are characteristic of private forest enterprises, whose collaboration within these frameworks enables more flexible management and the pursuit of sustainable forestry objectives [184]. Forming larger cooperative structures allows for the sharing of best practices, joint access to EU funding, and stronger collective advocacy in shaping forest policy, particularly by federations and holdings. Scale also facilitates access to both public and private support schemes.

All these organizational forms share a status as structured entities with defined governance architectures, objectives, and competencies, enabling them to carry out forest-management tasks effectively within the EU (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characterization of organizational and legal forms in the European forestry sector. Source: author’s own compilation.

4.3. Forest Area in EU

European forests cover approximately 160 million hectares. National forest administrations manage about 59 million hectares—roughly 37% of the EU’s forest area—while private owners and municipalities oversee over 99.5 million hectares (62%). Table 3 presents, for each Member State, the total forest area, the extent under national (state) management, and the area in private or municipal ownership, together with each category’s share of the national forest estate. (Areas of unidentified ownership are excluded.)

Table 3.

Forest area in EU Member States by ownership structure and share of national territory. Sources: Eurostat [185], UNECE [186].

4.4. Forest Ownership Structure in EU Member States

The highest proportions of national forest management—ranging from 25% to 86% of total forest area—are found in eleven former socialist Member States, where the average national-level estate covers approximately 2.19 million ha. Collectively, publicly owned forests in this group account for 63% of their combined forest area. Bulgaria leads with 86% under state administration, followed by Poland (81%), Czechia (76%), and Croatia (70%). Lower shares occur in Lithuania (59%) and Latvia (46%), with Slovenia at the lowest (25%). The average private-municipal holding for these countries is 1.22 million ha. The largest private-municipal shares are in Slovenia (74%), Estonia (60%), Latvia (54%), and Romania (49%); the smallest in Poland (18%), Croatia (29%), and Slovakia (34%).

By contrast, the sixteen “old EU” Member States average 2.31 million ha of state-managed forest, with national shares ranging from 0% to 74%. Public ownership in this cohort accounts for 28% of their total forest area. Greece exhibits the highest state share (74%), followed by Cyprus (69%) and Ireland (48%), while Malta (0%), Portugal (2%), and France (23%) record the lowest. Among the largest forest nations, Sweden, Finland, and Spain show public-ownership shares of 26%, 30%, and 32%, respectively. The average private-municipal estate in these countries is 5.37 million ha. Private-municipal forests predominate entirely in Malta (100%) and nearly so in Portugal (98%), Austria (82%), Denmark (82%), France (73%), Sweden (74%), Finland (69%), Spain (68%), Italy (68%), and Germany (77%). In the remaining Member States, private-municipal shares vary between 31% and 51%, with Greece at the low end (26%).

4.5. Forest Oversight in EU Member States in the Context of Organizational and Legal Forms

In every EU Member State, central governments—acting through their ministries—exercise oversight of state forests. National-level forest management, however, is organized under three principal legal forms: public institutions, state enterprises, and capital companies. Across the Union, we identify eleven dedicated forestry institutions, nine state forest enterprises, and seven state-controlled capital companies (three public limited companies and four limited-liability companies). These totals abstract from the multiple entities that may operate within each country, focusing instead on the prevailing organizational concepts. Table 4 provides a country-by-country overview of the organizational and legal forms employed by national forest-management bodies.

Table 4.

Overview of organizational and legal forms of conducting forestry in EU Member States. Source: author’s own compilation.

A common feature of all the structures described above is their organizational status as entities operating under the strategic direction set by the EU. They differ, however, in how and to what extent they implement these directives. Each possesses its own field-level network through which it executes its statutory functions.

4.6. Characterization of Selected Organizational Forms of Forestry Management in EU Member States

4.6.1. State Forest Enterprises

In nine EU Member States, the responsibility for administering and managing national forests has been assigned to state forest enterprises. With the exception of Finland and Germany, the post-socialist political transformations in Central and Eastern Europe marked the transition from a centrally planned, resource-extraction model of forestry to one based on the principles of sustainable forest management. During this period, forestry organizations were reconfigured around economic efficiency and financial self-sufficiency, charged with both administrative oversight and operational management of state forests. The size and extent of these forests—nationalized in the aftermath of World War II—remained largely unchanged for decades, while the initial waves of reprivatization, poor economic performance under the old model, and the mismatch between the capacity of state forest enterprises and societal expectations laid the groundwork for comprehensive reform.

Reform strategies typically included corporatization or partial privatization of forestry services and assets, and organizational restructuring—processes that continue, albeit in attenuated form, to the present day. In Poland, for example, the State Forests National Forest Holding (SF) operates under statutory authority without possessing separate legal personality; nevertheless, its organizational units function in practice like state-owned enterprises, leading Polish courts to recognize SF as a sui generis legal entity [187,188,189]. Commercial results—primarily from timber sales and resource management—drive its operations. Under EU law, SF is treated as a public undertaking participating in the market and subject to state-aid rules under Articles 107 and 108 TFEU [78], as well as sector-specific forestry-aid regulations [190]. Article 50 of Poland’s Forest Act [72] further enshrines the Holding’s financial self-sufficiency [191], reinforcing its “entrepreneurial” character, which the judiciary has consistently upheld [192,193]. Governance rests with the Director General, assisted by regional directors; at the operational level, forest district managers execute silvicultural plans independently within each forest district—the Holding’s primary organizational unit.

In the Czech Republic, the transformation of provincial state forestry enterprises resulted in the creation of joint-stock companies that conduct silvicultural operations and timber marketing on behalf of the State Forests of the Czech Republic. These companies operate under Czech forestry law, with their commercial activities governed by three distinct legislative instruments [194,195]. The Military Forests and Farms enterprise, under the Ministry of Defence, administers forests in military districts. In Slovakia, forests are managed by Forests of the Slovak Republic (Lesy Slovenskej republiky), a multi-tiered state enterprise with forest districts as the foundational units, specialized forest companies at the intermediate level, and a General Directorate at the apex [196].

Romania’s National Forest Administration “Romsilva” oversees forty-one forestry directorates aligned with the country’s administrative counties. Beyond conventional timber production, Romsilva is active in horse breeding and manages twenty-two national and natural parks [197]. In Estonia, the State Forest Management Centre (RMK) administers not only forests but also a wildlife park and a fish farm [198]. Lithuania established its own state forestry enterprise in 2018 to consolidate forest management responsibilities [199].

Germany’s integrated, multifunctional forest-management model—shaped at the Länder (state) level in recognition of each region’s autonomy—has garnered international attention [200]. Besides a single federal forestry enterprise (Bundesforst), forest administration is carried out by sixteen separate Länder forestry administrations, varying widely in legal and economic structure. These Länder enterprises typically lack distinct legal personality and are financed through net budget allocations from their respective state governments. Advantages of this model include investment and staffing flexibility, expedited decision-making, transparent accounting for forestry results, and operational autonomy balanced by public oversight [201,202]. In Bavaria, Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Schleswig-Holstein, and Thuringia, former Länder forest administrations were converted into profit-oriented state enterprises with explicit public-service obligations. Budgetary constraints at the turn of the century, alongside rising environmental and conservation imperatives, drove these reforms [28]. Though rooted in 19th-century reforms that unified German forestry under central planning to safeguard long-term yields—an industrial forestry paradigm synonymous with national economic independence—the 20th century saw the creation of a distinct national forestry sector [29].

In Finland, Metsähallitus—the State Forest and Park Service—embodies a hybrid model combining commercial and public mandates. A restructuring in 2016 separated its profit-seeking business operations (fully self-financed) from its public-sector administrative functions (state-budget funded). Metsähallitus owns a limited-liability company for its forestry activities, including timber sales; share transfers require parliamentary approval. It also manages the Parks and Wildlife Finland unit, responsible for the nation’s cultural and natural heritage conservation [30].

Bulgaria’s forest sector, still influenced by socialist-era legacies of state dominance and strict regulation, is organized into six state forestry enterprises overseeing 165 regional units. A separate Executive Forest Agency, with sixteen regional directorates and eleven park directorates, provides oversight and policy guidance [33,202]. Ongoing privatization of forest services, land restitution to private owners, and the demands of market liberalization and stakeholder engagement continue to drive the need for enhanced capabilities within state forestry organizations [34].

4.6.2. Capital Companies

Tendencies to convert state forestry entities into capital companies have appeared both in former socialist Member States and in the “old Union.” These transformations cannot be attributed to a single set of objective factors. In Sweden, management of state forests was entrusted to the public limited company Sveaskog AB, which became a holding of state-owned forestry companies and, as the first in Europe, prepared its structures for issuing green bonds to finance Sweden’s climate targets [35]. In Austria, the single-shareholder public limited company Österreichische Bundesforste AG was created to administer federal forests—without owning them—allowing a focus on efficient management; beyond core forestry operations, it holds stakes in other capital companies and operates in real estate, brewing, renewable energy, tourism, and consultancy [36].

Ireland’s state forestry company, Coillte Teoranta, holds and manages state forests under commercial principles. Its shareholders are the Department of Finance and the Department of Maritime Economy and Natural Resources. Coillte’s activities are carried out through subsidiaries, such as Medite Smartply (engineered wood panels), and specialized divisions for advisory services, ecosystem restoration, and renewable energy—enabling better economic risk management and resource utilization [37].

Hungary opted for a dispersed model, establishing 22 state-owned limited-liability forestry companies, all fully owned by the State Treasury and overseen by the Ministry of Agriculture [38]. In Croatia, Hrvatske šume Ltd.—founded in 1991—is a wholly state-owned forestry company [38]. Latvia’s Latvijas Valsts meži AS is the joint-stock company managing Latvian state forests [40]. Slovenia’s Slovenian Forests d.o.o. is the EU’s most recently established forestry capital company [41].

By their very orientation toward financial performance, capital companies are more driven to explore new markets, assume investment risks, embrace innovation, and improve operational efficiency—while remaining subject to public-service obligations and regulatory oversight.

4.6.3. Institutions

The dominant organizational-legal form for national-level forest management in many EU Member States is the public institution, directly integrated within the state administration and tasked with executing governmental forestry policy. In France, for example, the Office National des Forêts (ONF) [42] is a state institution conducting commercial forestry operations under the direct supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture. Its financial results are treated as instruments to support national policy rather than as independently appropriable profit. The ONF is led by a President, Vice-Presidents, and members of a Supervisory Board—each appointed by governmental decree—and managed on a day-to-day basis by a Director General. It alone is responsible for implementing France’s strict, multifunctional forest-planning regime. Its revenue streams include timber sales, hunting and grazing rights, services rendered to local authorities, and state budget subsidies.

Spain preserves regional autonomy through its autonomous-community governments. In Castilla-La Mancha, the Junta de Comunidades de Castilla oversees forestry via its Directorate-General for the Environment and Biodiversity; similarly, the Junta de Castilla y León manages not only state forests but also those of small public bodies and private owners, with responsibilities extending to firefighting, game management, fisheries, and biodiversity protection. In Catalonia, the General Directorate of Forest Ecosystems and Environmental Management—within the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Husbandry, Fisheries and Food—administers regional forestry policy [43].

Belgium’s complex federal structure assigns each region its own forestry institution: for Flanders, the Agency for Nature and Forests contracts out to Natuurinvest [44], which handles timber sales, property renovation, training venue management, and the promotion of nature-management practices. Denmark’s modest forest estate is managed by the Danish Nature Agency under the Ministry of Environment, which also regulates outdoor recreation, hunting and wildlife management, and nature conservation [45]. Italy likewise maintains national administrations that delegate to regional forestry bodies; in Malta—the only EU country without a private forestry sector—all forests fall under central government institutions.

In summary, a centralized institutional model enables coherent, top-down coordination of forestry policies at the cost of regional flexibility, whereas decentralized models respond more effectively to local needs but can hinder the uniform implementation of national objectives. The functions entrusted to these institutions range widely—from the full spectrum of multifunctional forest management to specialized conservation and social services.

4.7. Classification of Organizational and Legal Forms Operating in EU Forestry

In Southwestern Europe, institutions overwhelmingly administer national forests, while state enterprises predominate in Central Europe, and capital companies are least common across the Union (Table 5).

Table 5.

Organizational and legal forms conducting national-level forest management in EU Member States.

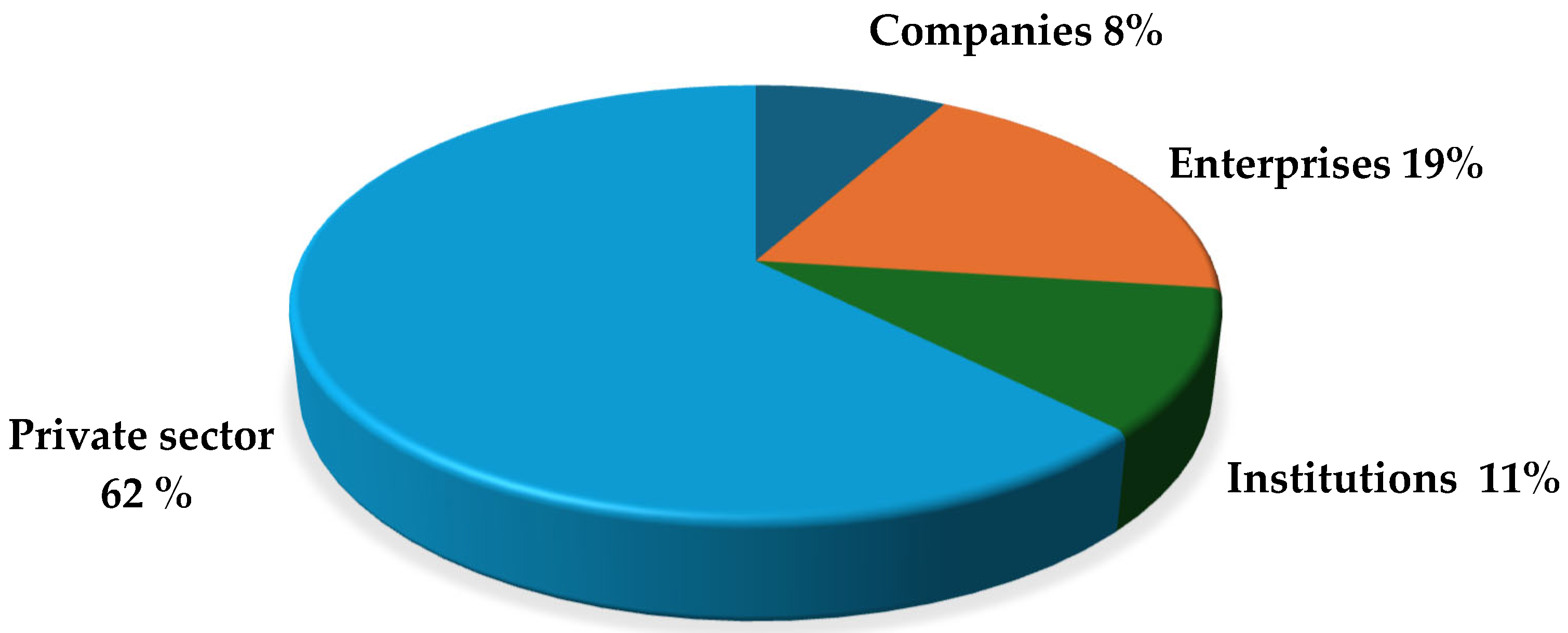

Overall, approximately 12,816 million ha of publicly owned EU forests are administered by capital companies, 29,185 million ha by state enterprises, and 16,859 million ha by institutions. The private sector—which includes individual holdings, associations, and municipal forests—manages about 99,465 million ha (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

EU forest area under management by organizational-legal form (million ha).

The highest share of privately owned forests is observed in the group whose national-level forest management is conducted by institutions (23.45% of the total EU forest area), followed by state enterprises (20.97%) and capital companies (17.68%).

4.8. Financing Sustainable Forestry and Potential Capital Sources in the EU

State ownership plays an important role in steering corporate governance toward achieving a range of government objectives [46]. A close interaction exists between the state and its forestry organizations. By fulfilling defined obligations and assisting the government, an organization can expect support in the form of preferential loans, tax incentives, grants, and subsidies. In the case of institutions, in addition to their budgets being linked to the national budget, their revenues also derive from commercial activities. Enterprises operate on a self-financing principle. Companies enjoy full financial autonomy in all countries where they are present. The scope for raising external capital—both to finance operational forestry activities and to achieve climate-related objectives—depends on the legal form of the entity, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Scope of External-Capital Mobilization by Organizational and Legal Form. Source: author’s own compilation based on [47].

Table 6 presents the standard sources of external capital. These include loans, borrowings, shareholder contributions, EU funds, membership fees, donations, and earmarked grants (awarded for a specific purpose); they also represent the most common way to receive EU funding, as well as non-earmarked subsidies. Existing forest-grant systems operate in many Member States and are used for various nationally defined objectives [48].

Within this classification, capital companies stand out for their ability to attract external investors via share offerings (which alter the company’s shareholder composition) and bond issues (debt instruments that leave ownership unchanged). Note also the role of Venture Capital funds, which provide both capital and expertise to young companies promising rapid returns. Forestry investments offer four approaches to portfolio diversification and risk mitigation—geographic, temporal, product, and market strategies [49]. Geographic diversification, through the choice of different countries, regions, or local markets and the ability to sell shares or issue bonds, helps attract investors. Private-sector capital is essential to scale up global forest- and landscape-restoration initiatives [50].

Bond issuance, as debt securities, is particularly significant in light of the EU Taxonomy Regulation [51] and the European Green Bonds Regulation (EuGB) [52]. The Taxonomy, driven by the European Green Deal (EGD) principles [52], aims to redirect private-capital flows toward sustainable investments that advance the EU’s sustainable development goals [54]. Green bonds—also called climate bonds—play a pivotal role [55,56]; they finance projects that improve the natural environment, support low-carbon economies, and enhance climate resilience. These frameworks enable market-based fundraising and allow investors to anticipate the Taxonomy’s impact on their portfolios, such as changes in capital costs or reallocation by other investors [57,58,59].

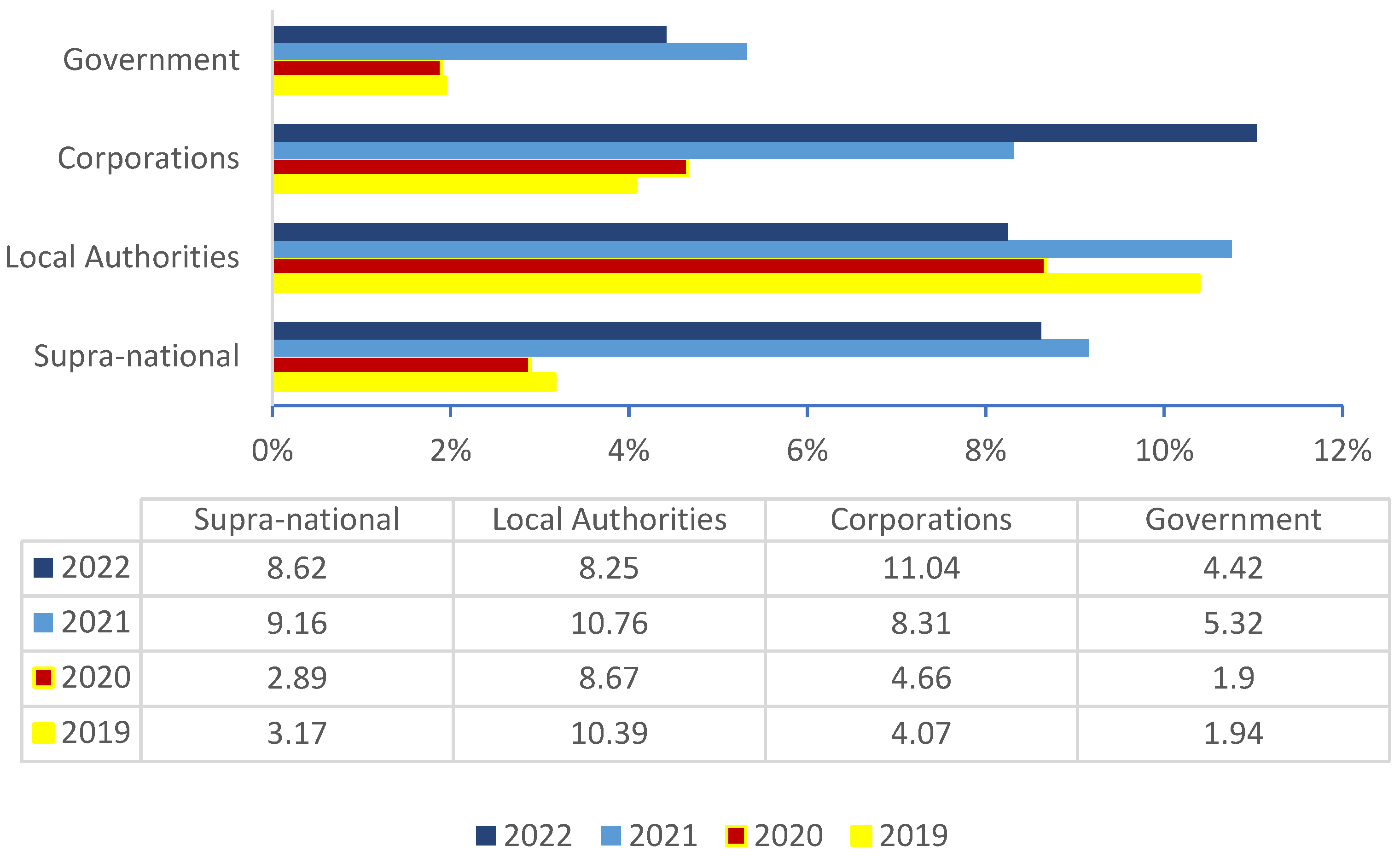

In recent years, the share of EuGB in total EU bond issuance has surged. In 2022, corporate issuers led with 11.1% growth, followed by local governments at 8.25% and national governments at 4.42%. Demand for EuGB may continue to rise as European interest rates fall, driving investors to seek new opportunities. Green bonds also serve a signalling function, demonstrating the issuer’s commitment to sustainable development [59]. Figure 2 illustrates the percentage share of green-bond issuance within total bond issuance by issuer type in the EU from 2019 to 2022 (a) and the share of green bonds in 2022 total issuance by Member State (b). Eurostat [64].

Figure 2.

Percentage of green bonds issued between 2019 and 2022 in total EU bond issuance by type of issuer. Eurostat [64]. Percentage of green bonds issued by EU countries in 2022.

The position of enterprises and institutions under the Taxonomy [94] can be described as that of secondary beneficiaries. Financial capital from private markets may originate from the issuance of green bonds by the State Treasury or local governments and be redistributed as grants or subsidies. Meeting the conditions set out in the Taxonomy is intended to determine access to EU funds. For “green” investments, a crucial dialogue must occur between financial-sector experts—who focus primarily on financial risk—and foresters promoting the investment potential of this asset class [69]. Capital raised in this manner may attract firms with higher long-term debt ratios [202]. Green bonds enjoy the greatest popularity in the Nordic countries and in Central-Western Europe, with the lowest uptake observed in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. An organization’s ability to attract external capital may be regarded as a key measure of its growth potential. Financing availability will vary across projects with different risk profiles and growth prospects.

5. Discussion

Development theories prevailing until the 1970s viewed progress solely through the lens of economic growth, focusing exclusively on profit [68]. The fundamental dilemma of the modern forest enterprise lies in the conflict between an owner’s pursuit of maximum profit and the aim of preserving the forest in a near-natural state. Managing public forests is not always economically viable without general public-budget support, as circumstances differ in terms of forest-management profitability and public-finance structures. The priority thus becomes finding a balance among the three interrelated pillars of sustainable development: environmental, social, and economic goals [203,204]. EU Member States share similar forest-policy objectives, although they differ in the measures adopted and their implementation methods. The organizational and legal form of forest-management entities is one such differentiator. The complexity of these forms precludes a single, unified organizational model for European forestry. The reasons for establishing entities separate from state administrations are rooted in commercial [205], economic, and technological factors, as well as outsourcing considerations. Viewing these structures from a single perspective is misleading; a holistic approach that incorporates multiple dimensions is more appropriate than replicating established organizational templates [206]. New management trends and anticipated benefits vary across municipal, private, and state forests, necessitating differentiated management models [28]. Management style is critical to delivering forest-ecosystem services and associated values. The interdependence of environmental performance, financial results, and wellbeing at the stand level requires these aspects to be integrated into natural-resource management [206].

The great variability and diversity of EU forests stem from the range of climatic zones across Europe [207], which influence stand composition and growth rates. Reliance on site conditions alone may lead to divergent quantitative and qualitative outcomes in similarly sized holdings. Studies have linked organizational effectiveness to management style and environmental factors [208,209,210]. Natural conditions [211] make forestry one of the sectors most dependent on natural capital, whose depletion may jeopardize the financial stability of forest enterprises [212]. Subjective valuation of the forestry sector is also shaped by ownership structure, which differentially influences owners’ objectives based on personal landowner preferences [31,213,214,215]. Private forest owners often see themselves as consumers rather than timber producers, seeking advisory services to overcome their lack of participation in forestry organizations [216]. In light of changing conditions affecting forest management, owner demographics—such as gender and age—are increasingly relevant [217,218]. Younger, better-educated owners are more likely to support diversified, biodiversity-focused management practices, whereas older owners tend to be more resistant to such measures [219]. Socio-economic shifts may compel modifications to forest-management practices [220]. Financial incentives and appropriate advisory services can help overcome barriers and promote environmental values [221].

Forest planning, as a sequence of interconnected decisions, requires continuous assessment of new information’s impact on corporate financial performance, enabling organizations to adapt to changing conditions. The multitude of forest functions makes it impossible to compile a single, exhaustive catalogue of management-influencing factors. Mishenina et al. [25,222] advocate for a wider use of modern management—public–private partnership (PPP) as a promising and strategic direction of environmental and economic policy in the forest sector, in the conditions of state and communal forest ownership. They believe that it can help to expand the investment potential of forestry and solve budgetary and financial problems [27]. The complexity of trade-offs in forestry and the often-conflicting challenges demand sophisticated compromises. Modern forestry, which delineates the potential services of forest ecosystems [27], requires a flexible management system capable of adaptation and risk tolerance, while accommodating stakeholders’ capacities for organizational change. This flexibility involves establishing general frameworks that allow discretion in response to external factors [223]. Inadequate institutional arrangements in forest management can marginalize the ecosystem services provided by forests [224]. The complexity of regulations shaping sustainable forestry may negatively affect adopted management practices [225], necessitating advisory and expert structures to provide intellectual support for forest managers. Industry knowledge, entrepreneurial capacity, and social responsibility enable legal issues to be addressed proactively before state intervention is required [226]. The primary indicator of forestry’s role in the national economy is the volume of wood harvested—i.e., the forest’s production function [227]. Forestry’s share of GDP varies among EU Member States and tends to decline in highly developed countries, reaching between 2.5% and 10.5% in less developed economies. Production functions and their contributions to national economies in countries such as Finland, Estonia, and Lithuania—where forestry’s GDP share exceeds 1% [228]—may shape management styles distinct from those in Western Europe, where biodiversity conservation is more emphasized. Management objectives influence the balance among the economic, ecological, and social dimensions of sustainable development [229]. The importance of environmental services and social integration in management is growing, especially in Nordic countries, where new economic activities—such as renewable energy, real estate, and recreation—are expanding, leading to increased outsourcing and workforce reductions. Liubachyna et al. [230] identified three main clusters of state forest management organizations (SFMOs) in Europe. The first cluster had a rather small but commercially oriented forest unit with other business activities and a strong emphasis on public services. The second cluster focused on the public interest, and the third was profit-oriented. The existence of different SFMO clusters shows different approaches to SFM with a focus on different goals (e.g., making profit, providing public services). Reductions in public forest management in Germany and Austria—driven by rising conservation and social-policy demands—led to economic crises in the 1980s and 1990s, prompting administrative and forestry reforms as well as enterprise commercialization. Today, the enterprises that emerged from these reforms generate substantially higher revenues from a variety of services, including ecosystem services [231]. Management forms differ between centralized and federal systems, complicating the coordination of forest policies at the EU level [232]. National regulations can strongly influence the effectiveness of higher-level policies [9]. Greater efficiency under centralized management—attributed to stronger work incentives and the inability to compare centralized and private management performance—has been demonstrated [233]. EU forest management is polycentric, dominated by around ninety national and regional administrative structures. This diversity represents potential for regional development based on established policies [234], best practices, and the promotion of regional capacity in forest production [235,236]. Although highly developed countries favour institutional management and countries with higher forestry-GDP shares favour enterprise models, it is not possible to classify these structures as inherently good or bad; their suitability depends on the conditions under which objectives are pursued [237]. Recognizing diverse national practices is fundamental to building a harmonized European forestry sector.

6. Conclusions

Forest management models in the European Union show considerable diversity in terms of legal form, organizational structure and implementation of economic and social goals. This diversity reflects the political and historical conditions of individual Member States, ownership patterns and natural and economic conditions. In the absence of a uniform, pan-European forest policy, its place is taken by a mosaic of sectoral regulations and national strategies that play a key role in climate protection.

Each Member State has established its own legal framework based on the principle of sustainable forest management, often supported by voluntary certification systems such as FSC and PEFC. Economic activities in forestry reflect national priorities and local conditions: private forests often focus on wood production, at the expense of broader sustainable development goals, while state forests implement the principles of sustainable management in a more comprehensive way, adapting more quickly to ecological, social and climatic needs.

The choice of organizational and legal form—from public institutions and state-owned enterprises to capital companies—determines the decision-making autonomy of entities, their financial independence and access to external capital. In countries where forestry primarily serves social or protective functions and private ownership is dominant, coordination of activities by state institutions, industry associations and chambers of commerce has proven effective. In countries where forests are of significant importance for the wood processing industry, forest management is usually entrusted to state-owned enterprises or capital companies.

Current trends in transforming state forest units into capital companies have increased flexibility in access to various financing instruments, but may also pose a risk of losing operational independence. A practical solution—used, for example, in Austria and Poland—is to leave forest ownership in the hands of the state, while entrusting management to autonomous entities. From a political point of view, it is recommended to continue supporting state entities in performing management functions while maintaining public ownership, which promotes better coordination of protective measures and ecological investments. EU and national financial instruments should take into account the diversity of forms of ownership and adapt support to the specifics of individual entities in order to more effectively implement the objectives of the EU Forest Strategy for 2030.

Due to different priorities, legal traditions and multifunctional needs of Member States, it is not possible to develop a universal organizational and legal model. Both state and private forests can implement multifunctional management and the objectives of the 2030 Strategy, but the legal form affects economic efficiency and the ability to raise capital. Further in-depth research is needed to match management models to the economic role of the forest sector in individual countries and to the dynamics of public opinion, in the light of the evolving requirements of sustainable development.

Analyses of the organizational and legal structure of forestry based on actual management models in the European Union constitute the basis for further research on the effectiveness of forest management in the context of biodiversity protection, which will be presented in subsequent publications. The reader can assess for himself how the complexity of management forms affects the coherence of the implementation of protective tasks in the area of European forests.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and J.B.; methodology, A.K. and J.B.; software, J.B.; validation, M.W. and K.A.; formal analysis, M.W.; investigation, K.A.; resources, M.W.; data curation, J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.; writing—review and editing, M.W. and R.G.; visualization, J.B.; supervision, M.W.; project administration, K.A.; funding acquisition, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this study was financed by the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education as part of the Strategy of the Poznan University of Life Sciences for 2024–2026 in the field of improving scientific research and development work in priority research areas.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bergès, L.; Avon, C.; Verheyen, K.; Dupouey, J.L. Landownership is an unexplored determinant of forest understory plant composition in Northern France. For. Cology Manag. 2013, 306, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, J.; Franz, K.; Seintsch, B.; Neitzel, C. Factors Explaining the Willingness of Small-Scale Private Forest Owners to Engage in Forestry—A German Case Study. Forests 2024, 15, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogl, K.; Pregernig, M.; Weiss, G. What is new about new forest owners? A typology of private forest ownership in Austria. Small Scale For. Econ. Manag. Policy 2005, 4, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittredge, D.B. The cooperation of private forest owners on scales larger than one individual property: International examples and potential application in the United States. For. Policy Econ. 2005, 7, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, F.; Laschi, A.; Zorzi, I.; Foderi, C.; Cenni, E.; Guadagnino, C.; Pinzani, G.; Ermini, F.; Bottalico, F.; Milazzo, G.; et al. Forest Sharing as an Innovative Facility for Sustainable Forest Management of Fragmented Forest Properties: First Results of Its Implementation. Land 2023, 12, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkumienė, D.; Doftartė, A.; Škėma, M.; Aleinikovas, M.; Elvan, O.D. The Need to Establish a Social and Economic Database of Private Forest Owners: The Case of Lithuania. Forests 2023, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.; Lawrence, A.; Hujala, T.; Lidestav, G.; Nichiforel, L.; Nybakk, E.; Quiroga, S.; Sarvašová, Z.; Suarez, C.; Živojinović, I. Forest ownership changes in Europe: State of knowledge and conceptual foundations. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 99, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juutinen, A.; Haeler, E.; Jandl, R.; Kuhlmey, K.; Mäkipää, R.; Pohjanmies, T.; Rosenkranz, L.; Skudnik, M.; Triplat, M.; Tolvanen, A.; et al. Common preferences of European small-scale forest owners towards contract-based management. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 144, 102939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichiforel, L.; Keary, K.; Deufficc, P.; Weissd, G.; Thorsen, B.J.; Winkel, G.; Avdibegovićh, M.; Dobšinská, Z.; Feliciano, D.; Gatto, P.; et al. How private are Europe’s private forests? A comparative property rights. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, J. Koncepcja „Ecosystem Services” i jej zastosowania w badaniach ekologiczno-krajobrazowych „Ecosystem Services” concept and its application in landscape-ecological studies. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2008, 21, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Młynarski, W.; Kaliszewski, A. Efektywność gospodarowania w leśnictwie—Przegląd literatury Efficiency evaluation in forest management—A literature review. Leśne Pr. Badaw./For. Res. Pap. 2018, 79, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Masternak-Janus, A. Analiza efektywności gospodarowania przedsiębiorstw przemysłowych w Polsce. Econ. Manag. 2013, 4, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowlati, T. Effiecency studies in forestry using data envelopment analysis. For. Prod. J. 2005, 55, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rist, L.; Moen, J. Sustainability in forest management and a new role for resilience thinking. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 310, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, D.H. The Evolution of Entrepreneurship: A Comparative Study of Perspectives Past, Present, and Future. Int. J. Adv. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2024, 2, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, E. Efektywność przedsiębiorstw-definiowanie i pomiar. Rocz. Nauk. Rol. Ser. G 2010, 97, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, W.; Paździor, A.; Paździor, M. Analiza Ekonomiczna Działalności Przedsiębiorstwa; Monografie-Politechnika Lubelska: Lublin, Poland, 2017; p. 7. Available online: http://bc.pollub.pl/dlibra/doccontent?id=13103 (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Mielcarek, P.; Markowski, P. Efektywność realizacji projektów strategicznych polskich przedsiębiorstw. Manag. Sci. 2017, 2, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ezquerro, M.; Pardos, M.; Diaz-Balteiro, L. Sustainability in Forest Management Revisited Using Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Techniques. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarski, W.; Prędki, A.; Kaliszewski, A. Efficiency and factors influencing it in forest districts in southern Poland: Application of Data Envelopment Analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 130, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, V.J.P.; Ferreira, A.J. Forest Resources Management and Sustainability: The Specific Case of European Union Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaszek, Ł.; Świć, A.; Gola, A. Koncepcja w zastosowania narzędzi predykcji w projektowaniu harmonogramów odpornych. Zarządzanie Przedsiębiorstwem 2016, 19, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Levchenko, Y.; Tshizma, Y.; Slobodian, N.; Nehoda, O. Organization and planning of the enterprises of the future: Legal status. Futur. Econ. Law 2022, 2, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denysiuk, O.H.; Ostaphuk, T.P.; Orlova, K.Y. Ensuring the efficiency of forestry enterprises’ potential management as an element of sustainable development. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1254, 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishenina, H.; Dvorak, J. Public–Private Partnership as a Form of Ensuring Sustainable Development of the Forest Management Sphere. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Bernal, D.C.; Hájek, M. Implementation of Economic Instruments in the EU Forest-Based Sector: Case Study in Austria and the Czech Republic. Forests 2023, 14, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linser, S.; Wolfslehner, B. National Implementation of the Forest Europe Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management. Forests 2022, 13, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C. Zarządzanie zmianami w leśnictwie niemieckim—Przekształcenie jednostek administracyjnych w państwowe przedsiębiorstwa leśne. Wyzwania leśnictwa wobec zachodzących zmian w środowisku przyrodniczym, oczekiwań społecznych, uwarunkowań ekonomicznych i prawnych. In Zimowa Szkoła Leśna Przy Instytucie Badawczym Leśnictwa, IX Sesja; Instytut Badawczy Leśnictw: Sękocin Stary, Poland, 2017; p. 152. Available online: https://www.ibles.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/publikacja2017.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Kotilainen, J.; Rytteri, T. Transformation of forest policy regimes in Finland since the 19th century. J. Hist. Geogr. 2011, 37, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsähallitus. Available online: https://www.metsa.fi/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Westin, K.; Bolte, A.; Haeler, E.; Haltia, E.; Jandl, R.; Juutinen, A.; Kuhlmey, K.; Lidestav, G.; Mäkipää, R.; Rosenkranz, L.; et al. Forest values and application of differe nt management activities among small-scale forest owners in five EU countries. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 146, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgaria. Available online: https://eustafor.eu/members/ministry-of-agriculture-and-food/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Makrickiene, E.; Brukas, V.; Živojinović, I.; Dobšinská, Z. Three decades of forest policy studies in the countries in the former socialist countries of Europe: A review. For. Policy Econ. 2025, 172, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazdinis, M.; Lazdinis, I.; Carver, A.; Paulikas, V.K. From union to union: Forest governance in a post-soviet political system. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweden. Available online: https://www.sveaskog.se/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Austria. Available online: https://www.bundesforste.at/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Ireland. Available online: https://www.coillte.ie/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Hungary. Available online: https://eustafor.eu/members/ministry-of-agriculture/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Croatia. Available online: https://eustafor.eu/members/sgd-hercegbosanske-sume/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Latvia. Available online: https://www.lvm.lv/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Slovenia. Available online: https://sidg.si/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- France. Available online: https://www.onf.fr/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Spain. Available online: https://eustafor.eu/about-eustafor/members/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Belgium. Available online: https://www.natuurinvest.be/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Denmark. Available online: https://naturstyrelsen.dk/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).