1. Introduction

The development of inclusive cities continues to improve the quality of the urban environments to establish gender equality so women can actively participate and achieve personal success through work, education, and leisure activities. The demographic makeup of society shows women comprise half of the population, so they must receive equal mobility rights and opportunities that match those of men.

The research connects the UN Sustainable Development Goals 5 and 11 to urban planning because these goals represent essential components for achieving gender equality in urban areas. The study investigates how cities can progress to create an accessible built environment which supports women and their inclusion in daily life participation.

It has become critically significant to think about women’s relationships with the city and their urban experiences to be seen in public spaces to know how much they belong to such places in the city [

1].

This study examines eight indicators that define women’s inclusion in the built environment, including safety, security, women-specific amenities, community engagement, cultural sensitivity, independent affordable accommodation, public facilities, mixed-use development, and mobility and accessibility. The research examines women’s movement patterns and navigation behaviors across Riyadh City in Saudi Arabia while studying women from various social characteristics and backgrounds. The research aims to determine existing opportunities for women’s public life engagement, in addition to defining the existing barriers that limit their efficient participation. The research draws from the “World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report (2016)”, which placed the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia at 141st position among 144 countries and 16th among 18 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region thus highlighting the substantial gender inequalities found in the Kingdom. The research investigates women’s movement in Riyadh to generate knowledge about improving urban planning and policy approaches for gender equality. The research examines how factors including pedestrian-friendly environments and public transportation usage, service availability, and challenge levels affect the efficiency and ability of women’s mobility in Riyadh City. The research investigates methods to enhance women’s mobility in Riyadh City while developing recommendations that support urban designers, planners, and decision-makers toward achieving women’s urban inclusion.

2. Literature Review

A comprehensive exploration of existing research and academic discourse concerning women’s inclusion within the built environment was conducted. This was employed to understand the prevailing main indicators related to gender-inclusive urban planning that influence women’s accessibility, safety, and participation in public spaces. It aimed to extract factors for analyzing women’s mobility in urban settings.

2.1. Women’s Inclusion in the Built Environment

The built environment is the tangible man-made element of the urban setting [

2]. It is defined by variables that trace all aspects of human living, encompassing the buildings, the supporting systems that provide water and electricity, the street networks, and the means of transportation. To approach a resilient built environment, the urban setting should accommodate all users’ needs and achieve gender equality, where all genders can move around freely, safely, and have healthy, sociable, and active lifestyles [

3]. In this regard, supporting women and promoting their inclusion in the built environment becomes crucial.

Multiple elements can have an impact on whether women are included in the built environment to effectively engage in all levels of activities. Certainly, unsafe cities directly contribute to women’s daily struggles to engage and access the provided socio-economic opportunities, resulting in a noticeable state of gender inequality [

3]. A comprehensive literature review established the evidence regarding the city’s priorities for men’s mobility, health, safety, leisure, and economic well-being over women’s [

4], and it is almost universally understood that women face significant social and economic disadvantages when compared with men [

4]. Women’s possibilities, safety, and health can all be enhanced by creating a more inclusive built environment.

The study has tackled a group of indicators which can be used to alter how cities are designed and structured, making them more friendly and inclusive to women’s requirements. Two of these indicators are related to the following: first, access and mobility; second, safety and security [

4]. The research adds new perspectives to the ongoing discussion on women’s inclusion in the built environment, by drawing on the actual research conducted with varied groups of women and desk-based literature reviews. It outlines six more indicators that affect women’s inclusion and impact city planning, those related to cultural sensitivity, public facilities and services, community engagement, mixed-use development, gender-specific amenities, and affordable housing options.

The literature reviews indicate that women’s mobility behaviors have not received much consideration [

5], according to assessments of women’s studies in the built environment [

6,

7]. Various references demonstrate the multiple levels of difficulties and limitations on the women’s movement that modern cities bring [

8].

Based on these premises, this study sheds light on the definitions of women’s inclusion indicators in the built environment, with a significant focus on Women’s mobility behaviors and the variables impacting it.

2.2. Indicators for Women’s Inclusion in the Built Environment

In order to design built environments that are equitable, safe, and functional for all users, it is crucial to comprehend the indicators of women’s inclusion. Investigating how well urban designs accommodate and represent women’s requirements can provide significant insights into gender equity. Indicators for women’s inclusion embrace a range of variables, integrating factors that address specific needs such as sense of safety, mobility, or accessibility. Understanding these indicators can help develop an inclusive built environment that supports women’s various experiences and fosters inclusivity, ultimately resulting in more resilient and balanced urban settings.

Figure 1 below represents the indicators for women’s inclusion in the built environment.

2.2.1. Mobility and Accessibility

The term “mobility” describes the capacity to move around and navigate without restrictions in the physical environment. A fundamental element of urban design is now being reexamined from a gender-inclusive perspective. Women’s daily activities, such as commuting to work, managing household duties, and dropping children off at school, necessitate certain mobility qualities that urban design must cater to in order to make the entire cityscape more accessible and inclusive. However, women’s mobility is influenced by various sociocultural, infrastructural, and financial constraints, making it a gendered and contextual experience [

9]. Globally, women’s mobility is restricted because urban mobility systems have historically been constructed with men in mind, leading to several challenges. These include inadequate public transportation options, lack of access to affordable transportation, poor infrastructure such as insufficient crossings, insufficient pedestrian and public transit facilities, in addition to social and cultural challenges: women may face social barriers to mobility, such as cultural norms that restrict their mobility [

4].

Private automobiles represent Riyadh’s main means of transport, with taxis covering more than 90% of the trips. However, the recent launch of the King Abdulaziz Project covers a small but growing share through the Riyadh Metro and bus systems [

10,

11,

12]. Saudi Arabia used to restrict women’s driving until recently; in 2018, this ban was removed, yet it still influences mobility patterns. Many women still rely on male family members or paid drivers during their driving training sessions and the process of obtaining driving licenses. The change supports Saudi Vision 2030′s objective of mobility diversification by introducing Phase One sports boulevards as pedestrian and cycling infrastructure. The average number of daily trips for Riyadh residents amounts to 1.812, while significant differences exist between genders: Saudi women aged 25–44 make 1.49 trips per day, while non-Saudi women aged 25–44 make only 0.417 trips daily [

10,

11]. The main reasons for trips are work, school, shopping, and recreational activities, demonstrating both urban needs and social preferences [

11,

12]. The highest amount of traffic flow occurs between 7:00–9:00 a.m. and 4:00–7:00 p.m., yet evening speeds reach 24.8 km/h while the morning speed reaches 33.1 km/h [

11,

13]. The duration of average travel times ranges between 16 and 24 min for distances of 10 km, yet car trips during peak hours require more than an hour and reach an average length of 20.5 km [

10,

11]. Non-Saudi female subjects aged 18–24 made only 0.548 trips per day, while Saudi male subjects made 4.746 trips per day, as these women had restricted access to public transportation and faced cultural barriers [

11,

12]. The Riyadh Metro demonstrates the potential to reduce car usage and create an inclusive transportation system. The Riyadh Royal Commission, together with the King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, conducted surveys to gather a deeper understanding of gender insights, as reported in [

11,

12,

13].

2.2.2. Safety and Security

Safety is a basic human right. The sense of safety and security is fundamental to every human being as an indicator of the quality of life. It has been defined by the World Bank (2020) as “being free from real and perceived danger in public and private areas” [

4]. Women’s safety and security are key factors in urban planning. Incorporating safety and security into cities’ urban spaces can significantly improve women’s mobility, thereby improving their mental and physical wellbeing [

3]. Women are more likely to participate fully in society when they feel safe and secure in their surroundings, creating healthier, more accessible, livable, and safe cities, which, in turn, increase economic activity and generate new revenue opportunities [

14]. However, concerns about personal safety can have a negative psychological impact and restrict a woman’s freedom and choice to move in public spaces [

15]. It is argued that women face safety concerns when accessing public spaces, such as low illumination in pedestrian zones, a lack of obvious security, and poorly connected public spaces. Literature has emphasized the importance of utilizing gender-sensitive urban design techniques. A great focus on women’s challenges and limitations, emphasizes the measures that raise awareness of urban safety while highlighting the disparities in how women use public space. Achieving more inclusive and equitable communities requires acknowledging these discrepancies and resolving them via urban policy and design [

16].

2.2.3. Women-Specific Amenities

The presence of women-friendly features in the built environment creates a sense of comfort and belonging [

17]. The idea of providing adequate amenities dedicated to fulfilling women’s needs increases the resilience of the inclusive built environment to accommodate women’s requirements and adopt their specific demands. Specific amenities can vary from tangible to intangible.

Women tend to enjoy commuting in the built environment within adequate spaces that have pathways with sufficient lighting, plazas with suitable seating platforms, other essential facilities such as toilets, praying areas, and spaces for children’s activities [

18]. However, the intangible variable is considered quite crucial; lacking the sense of safety and security can deter women from enjoying the built environment [

19].

In this view, an inadequate built environment that does not integrate such women-specific needs repeatedly exclude them from equal access to social and economic opportunities [

4]. Respectively, millions of women are dissatisfied with the existing infrastructure and public spaces they encounter during their life-work commutes, where the city designs fail to incorporate their needs [

20].

For instance, poorly maintained, male-dominated, dilapidated, dim spaces negatively impact women [

21]. Considering the tangible and intangible needs of women in the design of the inclusive built environment and amenities would resolve similar issues toward inclusive cities [

22]. This safer and healthier design approach provides vibrant cities for all [

23].

2.2.4. Engaging the Community

Engaging the community is an indicator that focuses on the role of women in participating in the decision-making process as a part of the community [

24]. This essential responsibility as a community representative allows room for discussions, expressing requirements, and conveying the messages of other women in need. These critical matters have to be discussed among stakeholders to raise awareness of them. Women’s participation aims to seek a better community engagement so that lasting sustainable outcomes, debate, processes, decision-making, or execution can be achieved [

25]. When women are involved in decision-making, their needs and perspectives are more likely to be considered with more inclusive and equitable policies and programs. In order to support women’s engagement, community meetings and workshops that are specifically designed for women should be held, in addition to providing support and training for women to participate in community organizations and government bodies and NGOs. By engaging women in community decision-making, more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable communities are created for all [

26].

2.2.5. Cultural Sensitivity

Cultural sensitivity represents the ability to recognize and understand different cultural values and beliefs alongside their practices, with great respect for the communities coming from diverse backgrounds. It involves being aware of others’ cultural preferences with a willingness to learn about and interact respectfully with them [

27]. Learning more about various backgrounds provides an opportunity to understand their needs in order to create a homogeneous platform inclusive of all communities.

Saudi Arabian culture, based on Islamic traditions and customs, requires cultural sensitivity. This typically involves a great respect for a particular dress code, awareness of prayer times, the prohibition of alcohol and pork, and respect for gender norms in various settings, including urban public spaces, restaurants, public transportation, and specific public events.

For the past decades, women have encountered some challenges regarding their dress code (such as the obligation to wear an abaya and headscarf), restrictions on travelling alone, and a ban on driving. It is important to note that there have been recent changes in Saudi Arabian laws, such as the permission for women to drive. The requirement for women to wear an abaya in public and cover their hair with a headscarf is no longer applied. Women are now freely able to travel abroad without restrictions [

27].

2.2.6. Independent Affordable Accommodation

Independent affordable housing stands as a fundamental factor that supports gender equality and women’s inclusion. Previously in Saudi Arabia, women relied on male guardians (mahram) for transportation, permission to work and independent accommodation [

28]. The availability of independent housing at affordable prices represents a fundamental condition for achieving gender equality and women’s social inclusion. Women who obtain secure, affordable housing that meets their preferences will achieve greater autonomy and better overall well-being. Great attention and support should be given to single, unmarried women and divorced mothers. Women should have unrestricted access to housing accommodations, just like other people, without social restrictions or financial barriers. With a safe and comfortable place to reside, women are enabled to live freely, pursue their education and jobs, and actively participate in society. Thus, this should not be limited by societal limitations or safety constraints. Open choices should be approachable, not as a luxury, but as an essential. Vision 2030 is working to grant these rights toward more inclusive communities.

2.2.7. Public Facilities and Services

Public facilities in urban spaces, which can be used in a public setting to meet the requirements of individuals or communities, are typically public services offered by the government or non-governmental organizations [

29]. Urban public facilities are generally classified into public health service facilities (public restrooms, sanitation rooms, garbage cans, smoke extinguishers, etc.), transportation service facilities (bus stops, bicycle parking, barrier-free facilities, etc.), public leisure service facilities (leisure seats, telephone booths, fitness and recreation facilities, lighting fixtures, etc.), and information service facilities (outdoor advertisements, bulletin boards, etc.) [

30]. Inequality in the allocation and accessibility of urban public facilities may result in a lack of access to public resources, the exclusion of vulnerable people, and, eventually, a generally unequal society [

29]. Women use and experience public space very differently than men, according to a large body of literature [

31,

32].

By analyzing different movement patterns in cities by gender, these inequalities might be demonstrated. Based on literature reviews, women’s movement patterns and experiences may be adversely impacted by broader structural reasons [

33,

34,

35]. Urban planning typically bases its modeling techniques on the daily “home–work–home” routine of the male-employed person. These models do not take into account the burden of childcare and household responsibilities borne by women. As a result, women move more frequently throughout the day and spend more time in public areas than men. Trip-chaining travel patterns, which are more prevalent among women and include “home–childcare–grocery–home–work–childcare–home”, are not well reflected by current urban or transport planning models [

16].

2.2.8. Mixed-Use Development

The term “mixed-use”, during the 1960s and the 1970s, arose in urban planning circles as a tool for urban rejuvenation, particularly in large-scale initiatives [

36]. The term “mixed-use development” is used to describe any proposal that does not include only one use. Uses can be vertically integrated with one another in a single building. Examples of vertically combined uses in housing schemes are those where the commercial space is on the first floor and the residential space is on the higher floors. Additionally, nearby buildings are referred to as having a horizontal variety of uses [

37]. Employing various and different uses in workplaces and living spaces at various levels of human communities, such as combining administrative, residential, and retail on one site, creating mixed-use developments in a district, block, or even a single building, and fostering diversity among people of different ages, income levels, cultures, and races, is extremely important in new urbanism. Adopting a mixed-use approach makes urban areas more lively, secure, and safe, and it enhances social contacts and decreases daily commutes (between work and home), which reduces traffic and prevents horizontal city development [

38]. The idea of providing mixed-use development promotes women’s mobility and facilitates women’s movement across the city. It provides the services needed within an adequate distance, promoting ease and relatively smooth navigation.

2.3. Saudi Arabia 2030 Vision and Women’s Inclusion

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has recently made progress toward the remarkable intentions outlined in Vision 2030 and created a roadmap for achieving its objectives and building a sustainable future. A dynamic society, a thriving economy, and an ambitious objective to reduce KSA’s reliance on oil, diversify its economy, and improve public service sectors are the key focuses of Vision 2030. KSA’s strategy places a priority on women’s inclusion, which will assist in achieving one of the most crucial objectives: lowering the female unemployment rate. More than 15 million women live in KSA, making up more than 45% of the country’s total population [

39]. The concept of women’s inclusion in the built environment has been defined as the ability of the city to fulfill the users’ needs (according to their gender) and provide the essential demands to facilitate their daily life [

40]. Women in Saudi Arabia still have a long way to go before inclusion is achieved. The gender gap in the country has received a lot of attention because it is thought that women’s rights are a sign of progress [

41].

The gender gap affects many aspects of a woman’s life. For instance, figures from the OECD assessment report (2016) demonstrate that employment rates for males with higher education are double the number of females with the same degree [

42]. Responding to that, KSA developed its strategic plan for Vision 2030 emphasizing women’s participation and inclusion as a priority, aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) introduced by the United Nations [

4,

43]. To achieve sustainable development, all countries around the world are aiming to accomplish the UN’s 17 SDGs. The importance of women’s inclusion and gender equality is an important target focused on by SDG5. As a result, Saudi Vision 2030 has initiated different programs for women’s inclusion to tackle SDG5, such as granting women leadership roles that were previously denied to them and providing new job opportunities for women estimated to exceed the 450,000 jobs [

43]. In addition, raising awareness through communal initiatives and training programs targeted at bridging the gap between men and women [

44].

2.3.1. Women’s Mobility in the Built Environment

Cities are a manifestation of the cultural, social, and national setting in addition to being hubs for transportation. The term “women’s mobility” was first coined and used in the 1990s, to characterize the struggles that women encounter when commuting around their urban environments. It refers to factors influencing women’s freedom of movement, such as cultural norms, access to transport, and safety measures [

45]. The subject steered reforms of urban strategies to offer better and equal access for all, which is safe and inclusive.

Since then, multiple studies around the world have investigated gendered mobility practices, however, recent studies have given more attention to women’s perspectives and variations of cultures, mode choice, and travel routes [

46]. This becomes significant to understand the women’s travel patterns and be able to integrate their needs. For instance, women’s trip chaining commutes are complex and multilayered in terms of time and space [

33,

47,

48]. Barriers vary in this respect ranging from women’s restricted access to resources in a context favoring motorized mobility. As a result, they struggle with the incompetent transport network against their complex daily schedules. This aspect is crucial to understanding that women’s commuting within the city is closely linked to schedules according to societal expectations and traditional definitions of women’s roles.

Despite increased female participation in higher education and paid employment, gendered roles have not significantly changed. Limited mobility and constraints related to time and space, such as children’s responsibilities, contribute to women working closer to home and using more public transport. Women often make fewer business trips and more trips for acquiring goods or escorting others, leading to more varied activity patterns and differentiated labor markets and space-time opportunities. Trip-chaining is more prevalent among women due to their complexity [

9,

49]. Studies conducted all across the globe show that women have made shorter travels in terms of both distance and time. This is particularly true for work-related travel, but it also applies to other forms of travel. In addition, women typically travel less and engage in more non-work activities [

50,

51]. The increased mobility entails increased risk and a heightened reality of violence [

52,

53], mobility can be both empowering and disempowering at the same time. Considering this, gender and mobilities studies consider women’s safety in urban public spaces to be an important subject, both practically and conceptually.

Finally, the research focuses on women’s mobility as a key indicator of inclusive cities. As understanding women’s mobility is essential for creating inclusive and equitable cities. Traditionally, women in Saudi Arabia have faced restrictions on their mobility due to social norms and limited access to transportation options. By recognizing the unique challenges and experiences women face in navigating urban spaces, policymakers and urban planners can take steps to address these barriers and promote gender equality. The focus of the study is on women in order to highlight the seriousness of Riyadh City’s efforts to implement inclusive and safety measures that empower women and support the goals of KSA Vision 2030.

As Vision of 2030 prioritizes women’s inclusion and aims for a society with equal opportunities, for women to fully participate in society, they need safe and easy ways to get around. This includes commuting to work, managing household duties, and accessing education and other opportunities considering mobility as crucial for engaging in daily life.

The research addresses these limitations, as studying women’s mobility provides valuable insights into how well a city is achieving the goals of Vision 2030, particularly regarding women’s empowerment and creating a vibrant society.

2.3.2. Riyadh City as a Case Study for Women’s Mobility in the Build Environment, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

There are 13 different provinces in the Saudi Arabian Kingdom. The Riyadh Province is the second largest region in KSA after Ash Sharqiyah. The capital city, Riyadh, has an area of about 1600 square km. It is Saudi Arabia’s capital and primary financial center. By the beginning of the 1940s, Riyadh had become a major industrial hub with progressive infrastructure and transportation systems thanks to the revenue from petroleum sales [

54]. The dominance of privately owned vehicles in Saudi Arabia mostly stems from the inadequate experience in offering public transport, exemplified by the Saudi Public Transport Company (SAPTCO) in Riyadh, which discontinued operations in 1992 in restricted regions [

55]. Riyadh in particular has historically lacked an efficient public transit system, with the Riyadh Metro commencing operations at the end of 2024. Furthermore, Riyadh City is wealthy and expansive, with its population significantly influenced by Islamic culture and numerous traditions pertaining to privacy besides the sociodemographic difficulties include a high average household size that led to the main reliance on privately owned vehicles [

56].

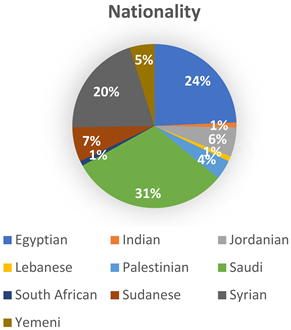

Currently, life in Riyadh is accelerating due to the considerable development that has occurred over the past years. Riyadh has become one of the most densely inhabited cities in Saudi Arabia, with a population of more than eight million in 2020. In the city of Riyadh, non-Saudis make up nearly half (44%) of the population and come from a variety of cultural backgrounds. According to the population pyramid, males, and females between the ages of 4 and 34 make up the majority of the population. This would suggest that Riyadh is a young city. However, the current mobility system heavily favors private automobiles rather than active modes of transportation like cycling and walking.

According to Frost and Sullivan (2016) [

54,

57], the announced transportation mode shares for the years 2000 and 2017 (83% and 87%, respectively) stated by statistics released by SAUDI National e-Government Portal (2020) [

58].

Riyadh, as the capital of Saudi Arabia, introduces a unique case study for gendered mobility. The city witnessed exponential urban expansion and transformed into an international business hub, influencing the extension of its infrastructure and transport network. A key aspect of this transformation is increasing women’s participation in public life. Therefore, reviewing the case of Riyadh, it is going through steady steps toward achieving the Vision 2030 goals, specifically the radical shifts toward empowering women.

The research aims at pinpointing areas of development to guide the city’s decision-makers and foster an enhanced experience for women. This stems from the reality that the sustainable inclusion of women in Riyadh cannot be guaranteed unless ongoing research and studies continuously communicate their needs. Achieving such progressive shifts requires developing public transportation modes and improving pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, so that Riyadh City becomes a more equitable and sustainable city for everyone.

3. Materials and Methods

The research methodology has adopted mixed methods. Both quantitative and qualitative approaches were used, including a descriptive analysis of the related literature. Researchers conducted an empirical study represented by a questionnaire survey for data collection, to investigate the women travel behavior as a tool for approaching their effective inclusion in Riyadh City.

The questionnaire (

Appendix A) was designed to explore similarities and variances in responses in relation to their lifestyle and perceptions [

59]. Important aspects assessing the sense of safety and comfort were the core of the study. The questions were distributed across the Riyadh City targeting women as individuals and groups as well, the team conducted field investigations within universities and shopping malls and approached participants to fill in the questionnaires. Also, the researchers depended on other contact methods, such as text messages, e-mails, and different social platforms, to gather more respondents to fill in the questionnaire. Initially, a pilot test was addressed to 23 participants, questions were then updated to ensure simplicity, clarity, and time efficiency, and provided with an Arabic translation when needed.

Tools and software programs utilized included data collection via Google Forms [

60], afterwards the extracted data was coded using Microsoft Excel, version 21, and then examined by using the “Statistical Package for the Social Science” (SPSS) version 23.

Statistics including means and standard deviation were calculated to describe the indicators and study variables. The aim of the examination was to analyze the women mobility behavior under the umbrella of the 2030 vision, since the start of allowing women in KSA.

The research population included women either working or housewives. The sample embraced 103 women as a stratified random sample, where the population is divided into subgroups (strata) based on a characteristic (e.g., based on gender), and random samples are subsequently drawn from the designated subgroup (i.e., women). The data were collected in a timeframe of four months. The questionnaire was structured in two sections with total 22 questions. The first section included the basic information related to sociodemographic characteristics of participants, taking into account (age, education, etc.); the second section tackled mobility behaviors and characteristics (car driving, availability of pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, cultural and social norms in Riyadh that influence the mobility choices, etc.).

The methodology was structured in sequential stages (as shown in

Figure 2). Firstly, it begins with a comprehensive literature review regarding women inclusion in the built environment, in the view of the Vision 2030. The literature introduces eight indicators, defining the inclusiveness of women. The research oriented its focus to study women’s mobility behavior as a tool for indicating women inclusion. Nevertheless, women mobility has been appealing as a measurable indicator since 2018 by the initiation of the royal decree to allow women to drive. And the 2030 vision that encourage women empowerment with more engagement in the business market and other platforms that acquire resilient city mobility. In addition to the large public transportation project currently underway in Riyadh, these changes motivate community members, especially women, to utilize buses and metro lines for their daily trips.

Secondly, the research reveals the findings of the questionnaire survey leading to the third stage of the discussion and interpretations. Finally, the research concludes with its findings, outcomes, and recommendations for further research. The research aims to offer several recommendations to enhance cities for women and subsequently resilient and inclusive for all.

4. Results

This research investigates the relationship between the built environment and women’s mobility in Riyadh. It identifies key factors influencing women’s mobility in the city. As outlined in the research methodology, the study was conducted in three main stages. The first stage involved a review of existing literature on women’s inclusion and mobility in Riyadh, focusing on the impact of the built environment to identify indicators affecting women’s mobility. The second stage involved analyzing and evaluating the current situation in Riyadh City using a quantitative approach, specifically through a questionnaire survey. The third stage involved analyzing the responses from this survey were analyzed using SPSS software.

4.1. Questionnaire Results

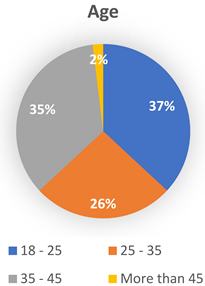

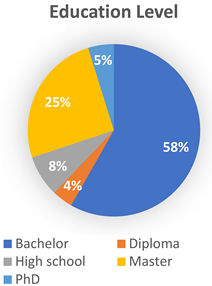

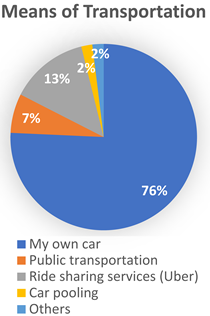

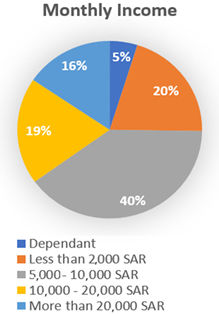

Women’s inclusion and mobility in Riyadh City were examined through a survey in which 103 women participated. A poll of women from multiple nationalities, varying ages, and high educational levels explored women’s inclusion and mobility in Riyadh (as shown in

Table 1). A total of 42.7% respondents have lived in Riyadh for more than 20 years, indicating that most of them have long-standing ties to the city. This could provide insightful information about how people perceive inclusion and mobility over time. The majority of respondents prefer longer, less congested routes and spend roughly half an hour a day on them. Regarding respondents’ ratings of their sense of safety while navigating Riyadh City, a significant portion of respondents (61.1%) rated their sense of safety as high, which suggests that most women feel relatively safe while navigating the city.

Participants’ responses about the availability of pedestrian-friendly infrastructure in Riyadh City indicated that a notable portion of respondents (36.9%) rated pedestrian-friendly infrastructure as low. This suggests that a significant number of women feel that pedestrian infrastructure in Riyadh is lacking, and it is likely considered insufficient or in need of improvement to meet the expectations and women’s needs.

As for the influence of cultural and social norms in Riyadh on mobility choices (40.8%) of respondents reported a high response. This suggests that cultural norms influence mobility decisions, however, not as significantly as other considerations like infrastructure or safety. These norms are essential for understanding how women move throughout the city, and these social and cultural variables must be considered for any interventions or policies aimed at enhancing mobility.

Regarding the rates of Riyadh’s public spaces and transportation facilities in terms of their suitability for women’s needs, a significant number of respondents (45.7%) rated them as high quality, indicating that the city’s public spaces are well-designed for these respondents.

When asked about Riyadh’s adaptability, ease of movement, and how free women felt navigating the city, a significant number of respondents (49.5%) ranked the city extremely flexible. This means that nearly half of respondents believe the city provides a high level of convenience and flexibility in movement.

Concerning the relationship between the “Ease of Mobility” and “Influence of Cultural and Social Norms” in Riyadh, the questionnaire had a specific question, where respondents were asked to rate the cultural and social norms in Riyadh that influence their mobility choices. The results show that around (80%) rated from medium to high influence of the social norms on their mobility choices in Riyadh City.

4.2. Statistical Analysis Results

In the process of analyzing the collected data (103 women living in Riyadh), the SPSS software was utilized to identify the correlations between the study indicators. Mainly, a correlation analysis using Spearman’s rho revealed a statistically significant positive relationship between some of the tested variables. The below subsections demonstrate these correlations, where it was evident that the most recurrent variables correlating with the dependent variable “Ease of Mobility” were safety, cultural and social norms, and the availability and convenience of public facilities and transportation.

4.2.1. The Influence of Safety and Security

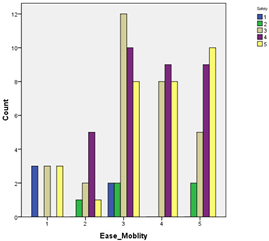

This statistical analysis indicates a significant relationship between the variables “Ease of Mobility” and “Safety” (as shown in

Table 2 and Table 5). A correlation coefficient (rho) of 0.22 was observed between the two variables, indicating a positive correlation. This result is statistically notable with a

p-value of 0.026, which falls below the conventional threshold of 0.05. Accordingly, it is confirmed that when there is an increase in perceived safety, there is a corresponding increase in the ease of mobility.

Table 2.

Ease of mobility and safety correlations.

Table 2.

Ease of mobility and safety correlations.

| Spearman’s Rho | | Ease_Moblity | Safety |

|---|

| Ease_Mobility | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | 0.219 * |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | . | 0.026 |

| N | 103 | 103 |

| Safety | Correlation Coefficient | 0.219 * | 1.000 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.026 | . |

| N | 103 | 103 |

4.2.2. The Influence of Cultural and Social Norms in Riyadh on Ease of Women’s Mobility (Cultural Sensitivity)

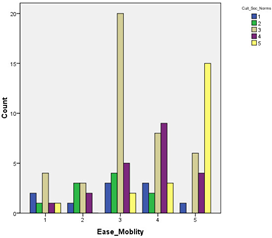

This second statistical layer indicated a significant relationship between “Ease of Mobility” and “Influence of Cultural and Social Norms” in the city of Riyadh (as shown in

Table 3 and Table 5). The correlation coefficient (rho) scored 0.46, revealing a moderate positive correlation between the two variables. This result is statistically meaningful, with a

p-value of less than 0.01, suggesting that it did not occur coincidentally. Viewing this result within the specific context of Riyadh, where driving cars is favored over modes such as walking and active mobility, illustrates a significant impact on women’s mobility, particularly since they were not allowed to drive cars.

On the bright side, these norms are changing after women were granted permission to drive starting June 2018. This change in laws marks a paradigm shift in women’s mobility. According to the survey results, this shift toward inclusion of women facilitated their job opportunities and effective participation in public life.

Table 3.

Ease of mobility, culture, and social norms correlations.

Table 3.

Ease of mobility, culture, and social norms correlations.

| Scheme | | Ease_Moblity | Cultural and Social Norms |

|---|

| Ease_Mobility | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | 0.460 ** |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | . | 0.000 |

| N | 103 | 103 |

| Culture and Social Norms | Correlation Coefficient | 0.460 ** | 1.000 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | . |

| N | 103 | 103 |

4.2.3. The Influence of the Availability and Convenience of Public Facilities and Services on Women’s Mobility in Riyadh City

This correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship between the variable “Ease of Mobility” and the variable “Availability and Convenience of Public Facilities and Transportation” (rho = 0.45,

p < 0.01) (as shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5). The Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient of 0.454 indicates a moderate positive association. In short, the ease of mobility improves as the availability and convenience of public facilities and transportation increase. It is important to consider the accessibility of public transportation to women, such as metro and bus stations. Ultimately, this contributes to improving the ease of mobility for women in Riyadh.

The remaining indicators did not reveal any significant correlation with the dependent variable “Ease of Mobility”. Additionally, a difference statistical analysis was conducted on the selected variables and indicators, reviewing respondents’ different age, education, income, etc. The analysis revealed no impact on their sense of safety or ease of mobility; thus, no significant statistical differences were found across demographic categories. The statistical analysis indicated no statistically significant difference was observed between demographic categories. The factors that might explain this finding include homogeneity of the sample, in which all participants were women living in a homogenous urban structure and culture. Additionally, demographic variables might only have influenced mobility indirectly, through, for example, access to car ownership, which was not explicitly analyzed in this research. Moreover, the sample size (N = 103), and the stratified random sampling approach, might have been effective in capturing broader trends, and were not able to detect subtle differences.

Table 4.

Ease of mobility and public facilities and services correlations.

Table 4.

Ease of mobility and public facilities and services correlations.

| Spearman’s Rho | | Ease_Moblity | Public Facilities and Services |

|---|

| Ease_Mobility | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | 0.454 ** |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | . | 0.000 |

| N | 103 | 103 |

| Public Facilities and Services | Correlation Coefficient | 0.454 ** | 1.000 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.000 | . |

| N | 103 | 103 |

Table 5.

Charts representing the correlation results.

5. Discussion

This section discusses influences on women’s mobility as an indicator of women’s inclusion in Riyadh City. The first correlation shows a significant influence between ease of mobility and safety (rho = 0.22, p < 0.05). This supports the literature review emphasizing women’s lack of safety is a critical aspect limiting women’s access to move freely and equally around their cities. However, the research suggests that the moderate strength of this correlation indicates that safety is itself influenced by other factors shaping the ease of mobility.

On the other hand, the positive correlation between cultural and social norms factor and ease of mobility scoring (rho = 0.46, p < 0.01) is quite significant. This grounded link reveals the necessity to continuously raise awareness about women’s roles and rights within the city, while mobility is a direct indicator of this realization. The recent progress in policies allowing women to drive represents a major shift against previous norms, resulting in an enhanced freedom of mobility and accessibility.

A third tier of this analysis investigated the positive correlation between the availability/convenience of public facilities/transportation choices with ease of mobility, yielding a result of (rho = 0.45, p < 0.01). This view reflects the significant influence of transportation availability and infrastructure quality in advancing women’s mobility experiences. This result promotes the essential need to conduct gender-responsive studies addressing women’s specific needs and travel pattern, contributing to an inclusive urban planning framework.

Thus, women’s mobility in Riyadh appears to be complex and holds multifaceted layers of influence. However, this study realizes that there is a notable gap of significant statistical data revealing demographic variations in mobility choices and travel patterns based on age, education, and income. Despite this limitation, the analysis revealed consistent trends in women’s perception of their mobility experience.

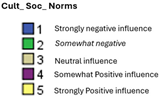

In the context of Riyadh, based on the research literature review, observations, qualitative data, and open discussions with the research respondents provide empirical data on women’s mobility in Riyadh, the traditional “home–work–home” framework has indeed been male-centric, reflecting longstanding cultural norms and infrastructure priorities. However, 43% of the research samples follow this routine “home–work–home”, while 57% represent multiple patterns, 20% follow the path of “home–school–work-school–home”, 17.5% follow the pattern of “home–school–shopping–home” as shown in

Figure 3. These results indicate that women in the Riyadh City (either driving or with a private driver) are responsible for certain tasks (for example: driving her children or siblings to school or evening training sessions, fetching groceries and supplies food and other shopping requirements). Women in Riyadh exhibit multiple mobility patterns beyond “home–work–home,” such as tasks involving school drop-offs and shopping.

Certainly, this paper directs the focus of urban development toward establishing gender equality through three specific areas of intervention: ensuring the safety of public places and transportation, shifting cultural norms to truly include women in the streets of Riyadh, and designing transportation systems and infrastructure that respond to women’s specific needs and travel patterns. Consequently, achieving ease of mobility for women requires a blend of physical and social reforms. This calls for a comprehensive mobility outlook toward creating inclusive and diverse metropolitan areas that respect cultural and traditional contexts such as Riyadh.

6. Conclusions

This paper demonstrated the layers of women’s mobility in Riyadh City versus the recent national attempts to integrate them equally into the city’s development plans under Vision 2030 to empower women and enhance their participation in public life. The shift in cultural norms has begun to offer opportunities for employment and social chances for participation and effective engagement, especially since the royal decree (2018) allowing women to drive.

The researchers adopted assessment methods to understand the significance of infrastructure, cultural norms, and safety as key factors for creating inclusive mobility experiences for women of Riyadh. This was fundamentally introduced and aligned with the KSA vision of 2030. The results showed that the variables women’s ease of mobility and sense of safety are significantly correlated, in which it is important to improve public facilities accordingly. Additionally, cultural norms are changing and becoming more accepting of women’s presence in the streets of Riyadh, which is another significant factor influencing women’s mobility. These findings can be linked to the continuous endeavors to shift societal perceptions and upgrade infrastructure to encourage women’s equal rights for improved mobility experience and their active inclusion in urban environments.

This paper offers insights into tangible outcomes and best practices to enhance women’s mobility conditions: first, improving public facilities and pedestrian infrastructure, by designing wider sidewalks, shaded pathways, and women-specific amenities. Second, promote community engagement and awareness campaigns, involving community workshops where women can voice their mobility needs to influence local planning and support the decision-making process. Third, develop reports and evaluation frameworks for tracking women’s mobility metrics (e.g., rates of public transport usage, safety incidents) and evaluate the impact of used measures, and report annually to align with Vision 2030 objectives. These recommendations provide a roadmap to improve the urban environment of Riyadh to be more responsive to women’s mobility needs.

By promoting these recommendations, Riyadh can reach the goal of Vision 2030: empowering women to fully participate in city development. Finally, this paper insightfully contributes to the body of research through its empirical study, addressing the direct mobility needs of women in Riyadh. The research emphasizes that future studies and policymakers’ agendas should carefully consider women-specific needs for feeling safe and accepted by their cities, helping to develop more inclusive and equitable urban communities.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Individual contributions are as follows: D.A.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, supervision, and visualization. M.N.A.T.: original draft preparation, investigation, and resources. S.S.A.: investigation, writing—review and editing, and resources. M.A.: formal analysis, validation, investigation, and writing—review and editing. S.A.: investigation, writing—review and editing, resources, and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The survey does not involve any sensitive personal data, complies fully with applicable ethical guidelines, and has been confirmed by the Chair of the Institutional Committee; therefore, it does not require additional ethical review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the survey population sample that supported our research process. Their contributions have significantly enriched our understanding of the subject. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Grammarly, version 6.8.259, for the purposes of checking grammar and proofreading. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hussain, A.; Shukla, D. Reclaiming Urban Spaces for Women Through Gender Inclusive Approaches. In Proceedings of the ICAB 2021, Sasi Creative School of Architecture, Coimbatore, Indian, 25–26 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi, A.R.; Jangjoo, S. Women’s preferences and urban space: Relationship between built environment and women’s presence in urban public spaces in Iran. Cities 2022, 126, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Cities Alive: Designing Cities That Work for Women; Arup and produced in partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the University of Liverpool; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Handbook for Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning and Design; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Washington, DC, USA; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Basarić, V.; Vujičić, A.; Simić, J.M.; Bogdanović, V.; Saulić, N. Gender and age differences in the travel behavior—A Novi Sad case study. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 4324–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, C.; Piva, E.; Pucci, P.; Rossi, C. A systematic literature review on women’s daily mobility in the Global North. Transp. Rev. 2024, 44, 1016–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujičić, A.; Mirović, V.; Simić, J.M.; Ruškić, N. Daily Trips Characteristics in Novi Sad—Gender differences. PROMET Traffic Transp. 2025, 37, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borker, G. Understanding the constraints to women’s use of urban public transport in developing countries. World Dev. 2024, 180, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uteng, T.P. Gendered mobility: A case study of non-western immigrant women in Norway. In The Ethics of Mobilities: Rethinking Place, Exclusion, Freedom and Environment, 1st ed.; Sager, T., Bergmann, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oakil, A.T.; Mehbub Anwar, A.; Alhussaini, A.; Al Hosain, N.; Muhsen, A.; Arora, A. Urban Transport Energy Demand Model for Riyadh: Methodology and Preliminary Analysis. Urban Transp. Energy Demand Model Riyadh Methodol. Prelim. Anal. 2022, 10, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Commission for Riyadh City. King Abdulaziz Project for Riyadh Public Transport. King Abdulaziz Project for Riyadh Public Transport – Royal Commission for Riyadh City. 2024. Available online: https://www.rcrc.gov.sa/ (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Muhsen, A.; Toasin Oakil, A. Sustainable Transport in Riyadh: Potential Trip Coverage of the Proposed Public Transport Network. [CrossRef]

- Al Hosain, N.; Alhussaini, A. Evaluating Access to Riyadh’s Planned Public Transport System Using Geospatial Analysis. [CrossRef]

- UN Women. “Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces: Global Results Report.” United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. 2017. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2017/10/safe-cities-and-safe-public-spaces-global-results-report (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Ratnayake, R. Fear of Crime in Urban Settings: Influence of Environmental Features, Presence of People and Social Variables. Bhumi Plan. Res. J. 2013, 3, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Vetro, A.; Concha, P. Building safer public spaces: Exploring gender difference in the perception of safety in public space through urban design interventions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Her City—A Guide for Cities to Sustainable and Inclusive Urban Planning and Design Together with Girls, 3rd ed.; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gorney, C. The Changing Face of Saudi Women. Natl. Geogr. Mag. 2016, 110–133. [Google Scholar]

- UN Women. Turning Promises into Action: Gender Equality in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN Women Headquarters Office: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beebeejaun, Y. Gender, urban space, and the right to everyday life. J. Urban Aff. 2017, 3, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, C. Evaluating the influence of fear of crime as an environmental mobility restrictor on women’s routine activities. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Renard, A. A Society of Young Women: Opportunities of Place, Power, and Reform in Saudi Arabia; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAWI. Available online: https://www.cawi-ivtf.org/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Abalkhail, J.M. Women and leadership: Challenges and opportunities in Saudi higher education. Career Dev. Int. 2017, 22, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarhaby, I. Modern woman in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Rights, challenges and achievements. Br. J. Middle East. Stud. 2018, 46, 201–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Women Creating Change WCC. A Blueprint for Women’s Civic Engagement in New York City Toward a More Just and Equitable Democracy; Women Creating Change: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, M. UN Country Results Report. 2023. Available online: https://saudiarabia.un.org (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Epstein, C.F. Woman’s Place: Options and Limits in Professional Careers; Woman’s Place by Cynthia F. Epstein—Paper—University of California Press; Univ of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.ucpress.edu/books/womans-place/paper (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Liu, M.; Yan, J.; Dai, T. A multi-scale approach mapping spatial equality of urban public facilities for urban design. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Pan, Y. A Study on the Renewal of Urban Public Facilities by Interaction Design in the Context of Smart Cities. Jpn. J. Ergon. 2021, 57 (Suppl. 2), K6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greed, C. An Investigation of the Effectiveness of Gender Mainstreaming as a Means of Integrating the Needs of Women and Men into Spatial Planning in the United Kingdom. Prog. Plan. 2005, 64, 243–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, N. Spatial Cognition and the Brain. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1124, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R.F.; Sawyer, G.K.; Begle, A.M.; Hubel, G.S. The Impact of Crime Victimization on Quality of Life. Trauma. Stress 2010, 23, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chant, S. Cities through a “gender lens”: A golden “urban age” for women in the global South? Environ. Urban. 2013, 25, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S. Politics of Urban Space: Rethinking urban inclusion and the right to the city. In Women, Urbanization and Sustainability; Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks: London, UK, 2017; pp. 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardner, P. Explaining mixed-use developments: A critical realist’s perspective. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual Pacific-Rim Real Estate Society Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand, 19–22 January 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huston, S.; Mateo-Babiano, D. Vertical mixed-use communities: A solution to urban sustainability? review, audit and developer perspectives. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual European Real Estate Society Conference, Vienna, Austria, 3–6 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khakzand, M.; Yazdanfar, S.A.; Mirzaei, M. Mixed Use Development, A Solution for Improving Vitality of Urban Space. Comun. Inst. De Investig. Cient. Trop. Ser. Cienc. Biolog. 2016, 33, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Garawi, N.; Anil, I. Geographical Distribution and Modeling of the Impact of Women Driving Cars on the Sustainable Development of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Dev. Change 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. In Proceedings of the Global Gender Gap Report 2024, the World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland, 21 September 2024.

- Alsubaie, A.; Jones, K. An Overview of the Current State of Women’s Leadership in Higher Education in Saudi Arabia and a Proposal for Future Research Directions. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Authority for Statistics GASTAT. Available online: https://database.stats.gov.sa/home/indicator/535 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Alessa, N.A.; Shalhoob, H.S.; Almugarry, H.A. Saudi Women’s Economic Empowerment in Light of Saudi Vision 2030: Perception, Challenges and Opportunities. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 2022, 12, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwach, P. Mapping Gendered Spaces and Women’s Mobility: A Case Study of Mitathal Village, Haryana. Orient. Anthropol. 2020, 20, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.C.S.; Bittencourt, L.; Taco, P.W.G. Women’s perspective in pedestrian mobility planning: The case of Brasília. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 33, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M.P. Gender, the Home-Work Link, and Space-Time Patterns of Nonemployment Activities. Econ. Geogr. 1999, 7, 370–394. [Google Scholar]

- Susilo, Y.O.; Dijst, M. How Far is Too Far? Travel Time Ratios for Activity Participation in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Rec. 2009, 2134, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azouz, N.; Khalifa, M.A.; El-Fayoumi, M. Mobility inequality of disadvantaged groups in Greater Cairo region. Renew. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorthol, R. Daily mobility of men and women—A barometer of gender equality? In Gendered Mobilities, 1st ed.; Cresswell, T., Uteng, T.P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner, J.; Holz-Rau, C. Women’s complex daily lives. A gendered look at trip chaining and activity pattern entropy in Germany. Transportation 2011, 44, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, V. Women’s victimisation and safety in transit environments. Crime Prev. Community Saf. 2017, 19, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Husseiny, M.; Mashaly, I.; Azouz, N.; Sakr, N.; Seddik, K.; Atallah, S. Exploring sustainable urban mobility in Africa-and-MENA universities towards intersectional future research. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 26, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, B.; Katar, I.M.; Al-Atroush, M.E. Towards sustainable pedestrian mobility in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia: A case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, M.A.; Al-Badi, A.H.; Mayhew, P.J. The enablers and disablers of e-commerce: Consumers’ perspectives. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2012, 54, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, O.; Potoglou, D. Introducing public transport and relevant strategies in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia: A stakeholders’ perspective. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2018, 6, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost & Sullivan. Southeast Asia’s E-Commerce Market to Surpass US$25 Billion by 2020 Despite Market Challenges, Finds Frost & Sullivan. PR Newswire. 2 June 2016. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/southeast-asias-e-commerce-market-to-surpass-us25-billion-by-2020-despite-market-challenges-finds-frost--sullivan-300320594.html (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Saudi Arabia’s National Portal for Government Services, Saudi Arabia’s National Portal for Government Services|GOV.SA. Available online: https://my.gov.sa/en (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Aboubakr, D.; Nasreldin, R.; Fattah, D.A. Assessing livability of public spaces in gated and ungated communities using the star model. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2020, 67, 605–624. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhresheh, M.M. Preference for void-to-solid ratio in residential facades. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).