Abstract

Green human resource management (GHRM) has emerged as an essential strategy for achieving environmental sustainability within organizations. However, there remains a significant gap in understanding its direct impact on sustainable performance. This study seeks to address these gaps by investigating the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance, with a focus on the mediating role of green innovation and the moderating influence of transformational leadership. A cross-sectional study was conducted among Malaysian small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to explore the interrelationships between green HRM, green process and product innovation, sustainability, and the role of sustainable leadership. The study’s findings reveal a positive and significant relationship between green HRM practices and sustainability, encompassing environmental, economic, and social aspects. The findings suggest that management support for environmental initiatives is a critical factor in enhancing the effectiveness and spread of green innovations, emphasizing the importance of GHM in the broader context of organizational change and sustainability. In addition, the study underscores the critical role of transformative leadership in fostering sustainable practices, particularly the significant moderator role of responsible leadership in driving sustainable business practices. In summary, this study provides a roadmap for businesses, particularly SMEs, to leverage HGRM as a strategic tool in their pursuit of sustainability.

1. Introduction

In an era increasingly characterized by environmental consciousness and the imperative for sustainable development, the integration of ecological considerations into human resource management has emerged as a pivotal area of scholarly inquiry [1,2,3]. Green human resource management (GHRM), which embodies the fusion of environmental management with HR practices, stands as a critical component in this evolving domain [4]. Despite burgeoning interest, the mechanisms through which GHRM impacts sustainable performance, particularly through green innovation and the influence of transformational leadership, have yet to be fully explored [5].

Despite the growing recognition of green human resource management as an essential strategy for achieving environmental sustainability within organizations, there remains a significant gap in understanding its direct impact on sustainable performance. While previous studies have highlighted the potential of GHRM in promoting eco-friendly workplace practices, the concrete outcomes of these initiatives in terms of organizational sustainability are not comprehensively understood [4]. This lack of clarity extends to the specific contributions of GHRM practices, such as sustainable recruitment, training, and motivation, toward improving the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance. The intricate dynamics of how GHRM influences these aspects of sustainable performance, despite being critical to both theoretical understanding and practical implementation, have not been adequately addressed in the existing literature [6].

Furthermore, the role of green innovation as a mediator in the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance presents another area of uncertainty. While it is hypothesized that GHRM practices can foster green process and product innovations, the extent to which these innovations contribute to the sustainable performance of organizations remains underexplored [7]. Additionally, the potential moderating effect of transformational leadership on this relationship introduces further complexity. Despite acknowledging the significance of leadership in organizational change and sustainability initiatives [8], the literature offers limited insights into how transformational leadership might enhance or influence the effectiveness of GHRM practices in achieving sustainable performance [9]. This gap signifies a critical need for research that disentangles these relationships and offers a clearer understanding of how GHRM, coupled with transformational leadership, can effectively drive sustainable performance in organizations.

Moreover, the evolving corporate landscape, with its increasing emphasis on environmental stewardship and social responsibility, demands a more nuanced comprehension of how GHRM aligns with these broader sustainability goals. The current literature often treats GHRM as a homogeneous concept, with limited exploration into the diverse practices encompassed within it and how they individually and collectively contribute to sustainable outcomes [4]. This oversight presents a significant challenge for organizations seeking to implement GHRM effectively, as they lack detailed guidance on which specific practices are most impactful in driving sustainable performance. The need to delineate these practices and understand their distinct roles is especially critical in the context of varying industry sectors and organizational sizes, where GHRM’s effectiveness and applicability may differ markedly. Addressing this gap is vital not only for advancing theoretical understanding but also for providing practical insights to organizations striving to integrate environmental and social considerations into their HR strategies [6].

This observation forms the basis for the next two research questions:

- How does GHRM influence sustainable performance, and what roles do green process and product innovation play in this relationship?

- In the context of GHRM’s influence on sustainable performance, how does transformational leadership moderate the impact and effectiveness of green innovations?

- What is the interplay between GHRM practices, green innovation, sustainable performance, and transformational leadership in achieving environmental and organizational sustainability goals?

Moreover, the role of leadership, particularly transformational leadership, in enhancing the efficacy of GHRM practices and fostering a culture of sustainability within organizations, calls for deeper investigation. While the existing literature underscores the importance of leadership in driving organizational change [8], its specific impact within the GHRM framework and on sustainable performance is less understood [9]. This gap in the literature points to the need for further research, guiding the investigation towards understanding the influence of transformational leadership on the effectiveness of GHRM practices in achieving sustainable performance.

This study seeks to address these gaps by investigating the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance, with a focus on the mediating role of green innovation and the moderating influence of transformational leadership. The research aims to contribute to the growing field of sustainable human resource management by offering insights that are theoretically robust and practically relevant for organizations committed to sustainability [10].

To achieve this objective, the study employs various theoretical frameworks, including the resource-based view (RBV) [11], triple bottom line (TBL) [12], innovation diffusion theory [13], and transformational leadership theory [14]. Together, these perspectives provide a comprehensive lens for examining the strategic role of HR in enhancing sustainable performance and the key elements that strengthen this relationship [6,15].

This study, by elucidating the intricate relationships between GHRM, green innovation, sustainable performance, and the role of transformational leadership, is poised to offer multifaceted implications for both theory and practice. Theoretically, it aims to contribute to the expanding literature on sustainable HRM by providing a deeper understanding of how GHRM practices influence organizational sustainability, thereby enriching the theoretical discourse with nuanced insights into the mediating role of green innovation and the moderating effects of transformational leadership. Practically, the findings are expected to offer tangible guidance for business leaders and HR professionals, suggesting effective GHRM strategies that can be employed to enhance sustainable performance. This study could also serve as a roadmap for organizations looking to integrate environmental sustainability into their core HR practices, thereby promoting a more holistic approach to corporate sustainability. Additionally, by highlighting the role of leadership, the research underscores the importance of fostering a leadership style that aligns with and supports sustainability goals, offering a valuable perspective for leadership development programs. Overall, the study has the potential to significantly impact how organizations conceptualize and implement GHRM as a tool for achieving environmental and sustainability objectives, influencing policy-making and strategic decisions in the realm of sustainable business practices.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Human Research Management

Green human resource management has emerged as a pivotal approach in integrating environmental management with traditional HR practices. Renwick, Redman, and Maguire [4] define GHRM as the implementation of HR policies and practices that promote sustainable use of business resources and help reduce environmental impact. This definition underscores the role of HRM in fostering a culture of sustainability within organizations. Jackson, Renwick, Jabbour, and Muller-Camen [6] further elaborate that GHRM encompasses a range of practices aimed at enhancing environmental performance through employee involvement and commitment.

Selection and recruitment are fundamental aspects of GHRM. Organizations focusing on sustainability incorporate environmental criteria into their selection processes. Jabbour and Santos [5] highlight that companies are increasingly looking for candidates who not only possess traditional skills and competencies but also exhibit a strong orientation towards environmental values and sustainability. This shift in recruitment criteria reflects an alignment of organizational goals with environmental responsibility, as noted by Renwick [4].

Training and development in the context of GHRM focuses on enhancing employee awareness and skills regarding environmental practices. According to Opatha [7], effective green training programs are essential for equipping employees with the knowledge and skills necessary to participate in the organization’s sustainability initiatives. These programs often include modules on waste reduction, energy conservation, and sustainable work practices. Ehnert, Harry, and Zink [3] suggest that such training not only enhances employees’ green skills but also fosters a culture of environmental responsibility.

In GHRM, compensation and rewards are structured to encourage and recognize employees’ contributions to environmental sustainability. Cascio et al. [16] argue that aligning reward systems with environmental performance metrics can significantly motivate employees to engage in sustainable practices. For instance, incentives for reducing waste or energy consumption can reinforce positive environmental behaviors. Bass and Riggio [8] note that such reward systems are more effective when they are part of a broader strategy of transformational leadership that encourages and values sustainability.

2.2. Sustainable Performance

Sustainable performance, as defined by Elkington [12], refers to an organization’s ability to operate in a manner that ensures long-term viability across environmental, economic, and social dimensions. This approach involves a comprehensive view of sustainability. Elkington [12] introduced the concept of the triple bottom line (TBL), which encapsulates this broader perspective, emphasizing that sustainable performance is formed by the integration of economic, environmental, and social performance. This holistic approach has been widely adopted in both academic research and business practice, advocating for a balanced consideration of profit, planet, and people in evaluating an organization’s success.

Economic performance, traditionally the primary focus of business evaluation, involves assessing an organization’s financial health and profitability. Sezen [17] and Baeshen [18] emphasize that sustainable economic performance is not just about short-term gains but also about ensuring long-term financial stability and growth. This aspect of performance is critical, as it provides the resources necessary for environmental and social initiatives. Xie [19] and Kanan [20] highlight the interconnectedness of economic performance with green innovations and sustainable practices, suggesting that these elements can drive long-term profitability and competitive advantage.

Environmental performance evaluates an organization’s impact on the natural environment. This includes metrics such as carbon footprint, energy efficiency, waste management, and resource conservation. Fang [21] and Kuo [22] stress the growing importance of environmental performance as a key component of sustainable business practice, reflecting the increasing global concern for environmental sustainability. The literature suggests that companies that excel in environmental performance often employ innovative green technologies and sustainable operational practices, which can also lead to cost savings and enhanced corporate reputation [23,24].

Social performance pertains to an organization’s impact on society. This includes issues like labor practices, community engagement, diversity and inclusion, and corporate social responsibility. Al-Shammari [25] and Singh [26] argue that social performance is critical for building trust and goodwill with stakeholders, including employees, customers, and the community at large. Studies by Mousa [27] and Marrucci [28] highlight that social performance is not just a moral imperative but can also contribute to business success by enhancing brand image and customer loyalty.

3. Theoretical Understanding

The evolving landscape of business sustainability underscores the importance of integrating environmental considerations into human resource management. To comprehend this integration, a thorough understanding of various theoretical frameworks is essential. This essay delves into four key theories—resource-based view (RBV), triple bottom line (TBL), innovation diffusion theory, and transformational leadership theory—and their relevance to GHRM and sustainable performance.

The RBV of the firm, emerging in strategic management during the 1980s, emphasizes the importance of unique internal resources for competitive advantage. These resources are characterized as valuable, rare, inimitable, and nonsubstitutable. In the context of GHRM, this theory suggests that sustainable HR practices can be a strategic resource. Empirical evidence supports this viewpoint, indicating that GHRM practices like green recruitment and training enhance firm performance through cost reduction, reputation enhancement, and improved employee engagement [29,30]. These practices, conceptualized as valuable, rare, inimitable, and nonsubstitutable resources, are posited to enhance sustainable performance. Empirical studies by Al-Shammari [25], Singh [26], and others have substantiated this perspective, demonstrating that GHRM significantly influences sustainable performance, with green innovation serving as a pivotal mediating factor. This relationship is further corroborated by the findings of Fang [21], Kuo [22], and Ahakwa [31], who highlight the direct impact of GHRM on environmental performance, mediated through green innovation.

The TBL framework, emphasizing an integrated approach to economic, social, and environmental performance, aligns seamlessly with the objectives of GHRM. This theoretical paradigm is reinforced by multidisciplinary research across various geographies, including works by Al-Shammari [25] and Fang [21], which elucidate the significant influence of GHRM practices on environmental and overall sustainable performance. The mediating role of green innovation, as identified in these studies, resonates with the TBL’s holistic view of organizational sustainability.

Introduced by John Elkington in 1997, the TBL concept advocates for a holistic approach to sustainability, encompassing profit, people, and planet. It calls for businesses to account not only for economic value but also for environmental and social value. GHRM practices, under this framework, contribute to the organization’s triple bottom line [32]. For instance, socially responsible hiring practices promote social value, while environmentally conscious operations enhance the planet aspect. Various studies have utilized TBL to evaluate the impact of GHRM on these three dimensions, offering a comprehensive perspective on the role of HR in sustainable development.

Developed by Everett Rogers, this theory explains the spread of new ideas and technologies within organizations. It highlights factors such as innovation characteristics, communication channels, time, and social systems. When applied to GHRM, the theory provides insights into how green innovations, encouraged by HR practices, permeate an organization. The innovation diffusion theory, which explains the mechanisms through which new ideas and practices permeate organizations, offers a vital framework for understanding the propagation of green innovation influenced by GHRM. Research by Al-Shammari [25], Singh [26], and others substantiates this relationship, indicating a positive influence of GHRM on green innovation and, consequently, on sustainability performance. The theory further elucidates the nuanced role of management’s environmental concern in enhancing the effectiveness of GHRM in fostering innovation.

Transformational leadership, introduced by James MacGregor Burns and further developed by Bernard M. Bass [8], focuses on the transformative role of leadership in organizations. Transformational leaders, characterized by their charisma and motivational prowess, are pivotal in fostering an environment conducive to innovation and change. In the realm of GHRM [33], such leaders are instrumental in advocating and implementing sustainable practices. Transformational leadership theory, which underscores the transformative impact of visionary leadership on organizational culture and practices, is particularly relevant in the context of GHRM [34,35,36]. Studies by Ahmed [37] and Singh [26] demonstrate the influential role of green transformational leadership in augmenting the effectiveness of GHRM practices, thereby enhancing green innovation and environmental performance. This theory also provides a foundational basis for hypothesizing the moderating role of responsible leadership in the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance, as well as in the mediation effect of green innovation.

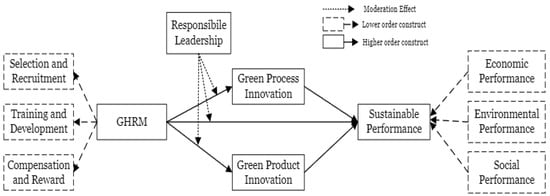

The interplay of these theories provides a multifaceted understanding of GHRM and sustainable performance. The RBV highlights the strategic value of green HR practices, TBL emphasizes the holistic impact of these practices on economic, social, and environmental performance, innovation diffusion theory sheds light on the adoption and spread of green innovations within organizations, and transformational leadership theory underscores the critical role of leadership in driving sustainability initiatives. Collectively, these theoretical frameworks offer a comprehensive lens through which to examine and appreciate the complexity and significance of integrating environmental sustainability into human resource management practices (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Hypothesis Development

4.1. GHRM, Green Innovation, and Sustainable Performance

Choudhary [38] and Hameed [39] both identify a positive influence of GHRM on green creativity, with Hameed further pinpointing green transformational leadership as a pivotal mediator. This perspective is reinforced by Masri [40] and Jia [10], with Masri emphasizing GHRM’s impact on environmental performance and Jia focusing on its role in fostering green passion and creativity. The importance of GHRM in cultivating a sustainable corporate culture is further highlighted by Nejati [41] and Shaban [42], with Nejati also noting its positive effect on green supply chain management. Additionally, Jabbour [43] and Roscoe [44] stress the need for integrating GHRM with green supply chain management and its role in establishing a green organizational culture.

Song [15] and Hameed [39] observe that GHRM positively impacts green innovation, with the latter identifying the critical role of green transformational leadership. Choudhary [38] and Jirawuttinunt [45] examine this relationship within the hospitality sector and ISO 14000 [46] certified businesses, respectively, with Choudhary emphasizing GHRM’s effect on employee green creativity. Empirical evidence supporting the positive correlation between GHRM practices and environmental performance is provided by Masri [40] in Palestinian manufacturing and by Nejati [41] in Iranian manufacturing firms. Shaban [42] additionally underscores the role of GHRM in shaping sustainability-focused organizational cultures.

Alenzi [47] and Al-Shammari [25] find that GHRM practices positively influence SP, with Al-Shammari further elucidating the mediating role of green innovation. Imran [48] and Khan [49] corroborate the positive impact of GHRM on SP, with Khan specifically highlighting the moderating role of external pressures. The significant role of GHRM in boosting SP, particularly in the context of green supply chain management, is accentuated by Bon [9] and Alenzi [50]. Roscoe [44] and Zhao [51] explore mechanisms through which GHRM practices, including proenvironmental HRM and corporate social responsibility, contribute to the development of a green organizational culture and the enhancement of SP.

Based on these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

There is a significant relationship between GHRM and green process innovation.

H2.

There is a significant relationship between GHRM and green product innovation.

H3.

There is a significant relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance.

Research by Sezen [17] underscores that green manufacturing and eco-innovation have a positive impact on corporate sustainability performance. Baeshen [18] extends this understanding by demonstrating that green innovation significantly influences sustainable performance in small and medium-sized enterprises. Further, Xie [19] and Kanan [20] highlight the beneficial effects of green process innovation and GHRM practices on sustainable performance. The role of green innovation as a key driver of sustainable performance, particularly when influenced by GHRM and Big Data, is elaborated upon by Imran [48] and Fernando [52]. Additionally, El-Kassar [23] and Xie [19] emphasize the importance of management commitment, human resource practices, and green subsidies in strengthening the link between green innovation and sustainable performance.

Further investigation into the realm of green product innovation by Sezen [17] and Majali [53] reveals its positive, yet variably strong, influence on sustainability performance, particularly in the context of green entrepreneurial orientation and green transformational leadership within small and medium-sized enterprises. Supporting this, Baeshen [18] affirms the positive effect of green product innovation on sustainable performance. Xie [19] and Weng [54] observe that green product innovation positively impacts both financial and corporate performance, with Weng additionally noting the crucial role of stakeholders in driving green innovation. The significant positive influence of green product innovation on firm performance is further corroborated by Ar [55] and Fernando [52], with Fernando highlighting the mediating role of service innovation capability. El-Kassar [23] delves into the drivers and outcomes of green innovation, including the influence of Big Data, management commitment, and HR practices.

Based on these insights, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H4.

There is a significant relationship between green process innovation and sustainable performance.

H5.

There is a significant relationship between green product innovation and sustainable performance.

4.2. Mediation of Green Process Innovation

Research conducted by Kanan [20] and Al-Shammari [25] demonstrates that GHRM positively influences sustainable performance, with green process innovation (GPI) playing a mediating role in this relationship. This assertion is further bolstered by studies from Imran [48] and Roscoe [44], with Imran adding that Big Data serves as an antecedent to green innovation. The discourse is expanded by Alam [56] and Bon [9], who delve into the roles of green employee empowerment and green supply chain management practices in mediating the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance. Additionally, Mensah [57] and Ragas [58] explore the impact of GHRM on factors such as green corporate citizenship, green corporate reputation, and job performance, with Ragas highlighting the potential of GHRM to influence employees’ lifestyle and job performance. Collectively, these studies underscore the significant role of GHRM in driving sustainable performance, particularly through the mediation of green process innovation.

In a similar vein, Fang [21] and Kanan [20] find that GHRM positively influences GPI, which, in turn, mediates the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance. This finding is supported by Al-Shammari [25] and Setyaningrum [59], with Al-Shammari observing that GPI partially mediates the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance, and Setyaningrum confirming GPI’s mediating effect on GHRM’s impact on business performance. These observations align with the broader literature that discusses the mediating role of green innovation in the relationship between environmental management practices and environmental performance [9,44,56,60].

Based on these insights, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6.

Green process innovation mediates the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance.

H7.

Green product innovation mediates the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance.

4.3. Mediated Moderation of Responsible Leadership

Alenzi [47] and Ren [61] independently conclude that GHRM practices significantly impact sustainable performance, with Ren particularly emphasizing the moderating role of CEO ethical leadership. However, the specific mechanisms through which responsible leadership moderates this relationship remain somewhat ambiguous. Omarova [62] and Roscoe [44] identify key elements in this dynamic, noting the mediating roles of environmental awareness and the enablers of green organizational culture, respectively. These findings imply that responsible leadership could potentially enhance the efficacy of GHRM practices by fostering environmental awareness and promoting a green organizational culture.

Further supporting this, Hameed [39] and Al-Shammari [25] observe that green transformational leadership positively affects the relationship between GHRM and green perceived organizational support. Additionally, they note that green innovation serves as a partial mediator between GHRM and sustainable performance. Ismail [63] and Jia [10] reinforce these findings, with Ismail highlighting the positive influence of GHRM on visionary leadership, and Jia demonstrating how transformational leadership can ignite employees’ green passion and creativity. Singh [26] and Perez [64] find that green HRM practices mediate the impact of green transformational leadership on green innovation, further enhancing environmental performance. Ragas [58] and Roscoe [44] also identify positive correlations between GHRM, job performance, and the facilitation of a green organizational culture.

In line with these observations, Liu [65] and Majali [53] discover that both ethical and green transformational leadership positively influence green innovation behavior and performance, with Majali additionally identifying a mediating role for green product innovation. Cai [66] and Zhu [67] augment these findings, with Cai focusing on the impact of leaders’ voluntary green behaviors on team innovation, and Zhu emphasizing the role of environmentally specific transformational leadership in employee green innovation behavior. Liao [68] and Liu [69] underscore the positive impact of responsible leadership on environmental innovation and performance, with Liu specifically noting green innovation as a mediator. Lastly, Singh [26] and Hang [70] explore the roles of green transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility in fostering green innovation and performance, with Hang highlighting the moderating influence of competitive advantage and the mediating role of green trust.

Based on these studies, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H8.

Responsible leadership moderates the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance.

H9.

Responsible leadership moderates the mediation effect of green process innovation on the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance.

H10.

Responsible leadership moderates the mediation effect of green product innovation on sustainable performance.

5. Research Methodology

5.1. Research Design and Sampling

This study utilized a cross-sectional design to explore the interrelationships between GHRM, green innovation, sustainable performance, and the moderating role of responsible leadership in diverse organizational settings. The cross-sectional approach, known for its efficacy in capturing data at a single point in time, was particularly suitable for the exploratory and explanatory nature of this research in the field of organizational studies [71,72,73].

The study was conducted in the Klang Valley, Malaysia, a region known for its diverse range of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which in 2021 included approximately 424,384 (34.6%) of Malaysia’s total SMEs of 1,226,494 [74,75,76]. Employing a convenience sampling method, as suggested by Golloway [77], facilitated efficient access to a broad spectrum of SMEs in this area. The questionnaire, developed in English and translated into Malay, ensured comprehensive understanding among participants from different linguistic backgrounds.

Aiming for a sample size of 425 (minimum sample of 383, for 95% confidence level with 5% margin of error), the study involved distributing 650 questionnaires via email to a variety of SMEs across the Klang Valley. Out of the responses received, 478 were suitable for initial consideration, and following a rigorous data cleaning process, 425 responses were deemed appropriate for final analysis. This process led to a response rate of approximately 65.4%. The data-cleaning procedure involved removing responses from participants who did not meet the study’s specific criteria or displayed signs of inattentive responding, including incomplete survey responses, repetitive answer patterns, ambiguous responses, or unclear answers to open-ended questions.

To address potential nonresponse bias, the study applied the approach recommended by Armstrong and Overton [78]. A comparison of demographic factors, such as age and gender, was conducted between the initial 55 respondents and the last 55 respondents using independent sample and chi-square T-tests. This comparison aimed to detect any significant differences between early and late respondents. The analysis revealed no significant variations between these groups (p > 0.05), indicating that nonresponse bias was not a concern in the study.

5.2. Measurement Development

Sustainable performance, serving as the dependent variable in this study, was assessed through its three formative dimensions: environmental, economic, and social performance. To measure these dimensions, nine items were adopted from the study by Jabbour and de Sousa Jabbour [43]. These items were evaluated using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “1” (strongly disagree) to “5” (strongly agree), with “3” representing a neutral stance.

To analyze GHRM practices as an independent variable, ten items were used, encompassing three reflective dimensions of GHRM. These items were adopted from the research conducted by Yu [79]. The same five-point Likert-type scale was employed for participants to express their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement.

Green product innovation and green process innovation were included as mediating variables in this study. The measurement of green innovation was based on six items adopted from the study by Zailani [80]. Respondents were asked to rate these items on the aforementioned five-point Likert-type scale to gauge the level of green innovation within their organizations.

Responsible leadership, the moderating variable in this study, was measured using items that reflect the extent to which leadership within the organization demonstrates ethical, environmentally responsible, and socially conscious behaviors. The scale for this variable was adapted from a previous study [68,81] that focused on leadership’s role in fostering sustainable practices within organizations. Participants rated these items using the same five-point Likert-type scale to indicate their agreement with statements about their leadership’s practices and attitudes towards sustainability.

5.3. Data Analysis Technic

The study employed SmartPLS 4 for data analysis, focusing on the relationship between GHRM practices and sustainable performance in an organizational context. GHRM, conceptualized as a second-order construct, comprised three dimensions: training and development, hiring and recruitment, and compensation and rewards. These dimensions demonstrated strong internal consistency, with composite reliability scores exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7, indicating good reliability [82]. Convergent validity was also confirmed, as each dimension’s average variance extracted (AVE) surpassed the 0.5 benchmark [83].

Sustainable performance, the study’s dependent variable, was measured through its three dimensions—environmental, economic, and social performance. These dimensions revealed robust validity and reliability, with AVE scores exceeding the recommended levels and strong internal consistency reliability scores.

In examining the structural model, path coefficients indicated a significant relationship between GHRM practices and sustainable performance. Bootstrap resampling with 5000 subsamples validated these paths, showing p-values below 0.05, thus confirming the hypothesized relationships. The R-squared value for sustainable performance was substantial, demonstrating the model’s strong explanatory power. Additionally, model fit indices, including SRMR and NFI, fell within acceptable ranges, indicating an adequate fit of the model to the empirical data [84].

PLS-SEM analysis confirmed a significant and positive relationship between GHRM practices and sustainable performance, encompassing environmental, economic, and social aspects. This result supports the theoretical framework proposed in the study and aligns with the existing literature, offering valuable insights into the role of GHRM in enhancing sustainable performance in organizational settings.

6. Data Analysis and Results

In the study of GHRM, green innovation, and sustainable performance among Malaysian SMEs (Table 1), the sample showed a slightly higher proportion of male (55.3%) to female respondents (44.7%), mirroring typical workforce demographics in SMEs and providing diverse insights into GHRM practices. Most respondents were in their career prime, aged 26–45 (65.9%), likely holding significant roles and experience in sustainability practices. The inclusion of both younger (below 25) and older (above 55) participants ensures a range of experiences and attitudes toward GHRM and sustainability.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

Educational backgrounds varied, with a majority (52.9%) holding bachelor’s degrees and a significant portion (29.4%) having master’s degrees, indicating a strong understanding of GHRM practices. The presence of respondents with doctorates (4.7%) and high school education (12.9%) further diversifies the sample.

Regarding positions, nearly half of the respondents (47.1%) were in middle management, followed by upper (29.4%) and lower management (23.5%), suggesting that the insights come from individuals with potential influence in their organizations. Experience levels varied, with the largest group having 2–5 years of experience (35.3%), followed by those with 6–10 years (28.2%) and over 10 years (16.5%).

Most respondents (42.4%) came from SMEs with 51–200 employees, but all organization sizes were represented, enriching the understanding of how GHRM practices and sustainable performance vary across different scales. Overall, the demographic diversity of the respondents provides a comprehensive view of the workforce in Malaysian SMEs, grounding the study’s findings in a broad spectrum of perspectives and experiences.

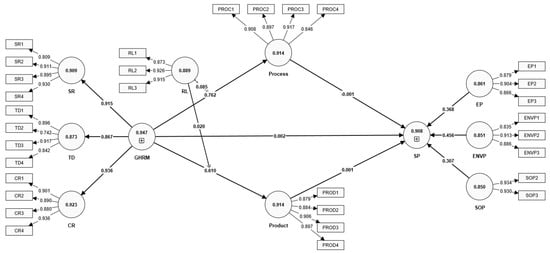

6.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

In this study of GHRM, green innovation, and sustainable performance among Malaysian SMEs, the measurement model’s reliability and validity were rigorously evaluated (see Table 2 and Figure 2). The reliability of the constructs was established through Cronbach’s alpha, with values ranging from 0.850 to 0.923, indicating high internal consistency [82]. Composite reliability scores were also robust, ranging from 0.913 to 0.946, further affirming the consistency of the constructs [83].

Table 2.

Results of measurement model.

Figure 2.

Illustration of measurement model (lower-order model).

The average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.50, denoting good convergent validity and suggesting that a substantial portion of the variance in the indicators is captured by the associated constructs [85]. Additionally, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values fell well below the threshold of 5.0, ruling out concerns of multicollinearity and indicating that the constructs are distinct and measure different phenomena [82,85].

Each specific construct, including social performance (SOP), environmental performance (ENVP), economic performance (EP), green process innovation, green product innovation, and responsible leadership (RL), demonstrated high reliability and convergent validity. This is indicative of their robust measurement in the context of GHRM. The selection and recruitment (SR), training and development (TD), and compensation and reward (CR) dimensions, as part of GHRM, also showed strong reliability, as depicted in the structural model (Figure 2).

The measurement model’s indicators, represented in Figure 2, substantiate the constructs’ validity and reliability. The analysis presents a solid foundation for subsequent structural model assessment and supports the study’s contributions to the literature on sustainable organizational practices in the context of GHRM. The findings, detailed in Table 2, provide a reliable and valid assessment of the constructs pertinent to GHRM and sustainable performance.

6.2. Discriminant Validity

The discriminant validity of the constructs in our study on GHRM, green innovation, and sustainable performance was thoroughly assessed using both the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio (Table 3) and the Fornell–Larcker criterion (Table 4). These statistical assessments are crucial for ensuring that the constructs are empirically distinct and the measures are not conflated.

Table 3.

Discriminate validity (HTMT).

Table 4.

Discriminate validity (FC criterion).

According to the HTMT ratio results (Table 3), all values fell below the conservative threshold of 0.90, with the majority also below the more liberal threshold of 0.85 [86], confirming adequate discriminant validity among the constructs. This suggests that the constructs are sufficiently differentiated, with the lowest HTMT value observed between the process and responsible leadership (RL) constructs and the highest between selection and recruitment (SR) and compensation and reward (CR), indicating distinct conceptual domains as intended in the study design.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion results (Table 4) further support discriminant validity. The square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct (diagonal elements) were greater than the interconstruct correlations (off-diagonal elements), as required for establishing discriminant validity [83]. The diagonal elements, representing the square root of the AVE, ranged from 0.852 to 0.932, exceeding all off-diagonal interconstruct correlations, which reaffirms the uniqueness of each construct in the measurement model.

These robust discriminant validity results, combined with the reliability statistics reported in Table 2 and the structural model illustrated in Figure 2, provide a solid foundation for the reliability and validity of the measures used in this study. This comprehensive assessment ensures that the findings from the study’s analysis, conducted with SmartPLS 4, are based on sound empirical measurements, making a significant contribution to the literature on sustainable practices in the context of GHRM.

Table 5 details the outer loadings of the lower-order model indicators, offering insight into the relationships within the constructs of the study on GHRM and sustainable performance. The loadings demonstrate strong associations across all indicators, with ENVP on SP (0.991), SOP on SP (0.891), and CR on GHRM (0.935) showing particularly robust links, all significant at p < 0.001. The T statistics reinforce these findings, with ENVP on SP notably high at 175.854. SR, TD, and CR indicators’ strong loadings on GHRM further confirm the multidimensionality and the strength of GHRM as a construct.

Table 5.

Outer loading of the lower-order model indicators.

6.3. Hypothesis Development and Discussion

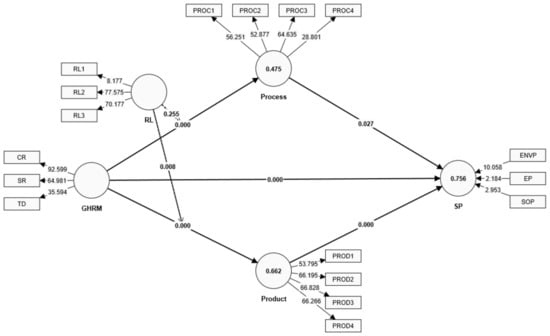

The structural model results in Table 6, reinforced by Figure 3, provide a comprehensive analysis of green human resource management’s influence on sustainable performance (SP) in Malaysian SMEs, considering the mediating roles of green process and product innovation and the moderating effect of responsible leadership (RL).

Table 6.

Results from structural model measurement.

Figure 3.

Illustration of structural model (higher-order model).

The study substantiates Hypotheses 1 and 2, revealing GHRM’s substantial positive effect on both green process innovation (β = 0.750, p < 0.001) and green product innovation (β = 0.336, p < 0.001); refer to Table 6. These results align with Choudhary [38] and Hameed [39], who note GHRM as a catalyst for green creativity, with our study extending this understanding to a quantifiable impact on innovation outputs. This echoes Masri [40] and Jia [10], who emphasize GHRM’s influence on environmental performance and the fostering of a culture of green passion and creativity. Our findings corroborate their assertions, demonstrating that GHRM effectively translates into tangible process and product improvements.

Contrary to the positive associations posited by Alenzi [47] and Al-Shammari [25], Hypothesis 3 (GHRM’s direct impact on SP) was not supported (β = 0.004, p = 0.819), suggesting a more complex relationship than previously understood; refer to Table 6. Similarly, Hypothesis 4 (green process innovation’s effect on SP; refer to Table 6) found no significant direct impact (β = 0.020, p = 0.226), challenging assertions by Bon [9] and Alenzi [50]. However, Hypothesis 5 was affirmed, with green product innovation showing a significant positive influence on SP (β = 0.106, p < 0.001), in line with Baeshen [18] and Sezen [17]. These findings suggest that while GHRM creates an environment conducive to innovation, it is specifically the tangible outcomes of green product innovation that drive SP.

While green process innovation did not mediate the GHRM–SP relationship (H6: β = 0.015, p = 0.237), green product innovation did (H7: β = 0.036, p < 0.001). This distinction underlines the need for a strategic focus on product innovation to leverage GHRM’s full potential in enhancing SP. The findings expand upon the research by Fang [21] and Kanan [20], emphasizing the critical role of product innovation in achieving sustainable outcomes.

The study found that RL did not significantly moderate the GHRM–SP relationship through process innovation (H8 and H9; refer to Table 6), contrasting with Alenzi [47] and Ren [61]. However, it did significantly moderate the relationship through product innovation (H10: β = 0.006, p = 0.032), supporting insights from Hameed [39] and Al-Shammari [25]. This indicates that RL, particularly in transformational and ethical forms, can enhance the efficacy of GHRM practices, and more so when focused on product innovation.

The model demonstrated excellent predictive relevance for SP (Q2 = 0.958) and good explanatory power (R2 = 0.964), with very low RMSE and MAE, indicating an excellent fit; refer to Table 7. In summation, our study enriches the literature by delineating the nuanced pathways through which GHRM influences SP in SMEs.

Table 7.

Model fit.

7. Implications of the Study

7.1. Theorical Implication

This study’s exploration of green human resource management (GHRM) and its impact on sustainable performance, framed within the resource-based view (RBV), triple bottom line (TBL), innovation diffusion theory, and transformational leadership theory, offers significant theoretical implications for the field of sustainable business practices.

Consistent with RBV, our findings reinforce the strategic value of GHRM practices as unique internal resources that drive competitive advantage. Aligning with Al-Shammari [25] and Singh [26], the study demonstrates that GHRM, characterized by its rarity and inimitability, significantly influences sustainable performance, particularly when mediated by green innovation. This bolsters the RBV perspective, suggesting that GHRM practices, beyond their inherent value, contribute strategically to enhancing an organization’s sustainability.

In alignment with the TBL framework, our study highlights how GHRM practices contribute to an organization’s holistic sustainability goals. The significant impact of GHRM on green product innovation, and its subsequent influence on sustainable performance, encapsulates the TBL’s ethos of balancing economic, social, and environmental aspects. This finding illustrates the integral role of GHRM in achieving comprehensive sustainability, aligning with the multidimensional approach advocated by the TBL framework.

Our study extends the innovation diffusion theory by demonstrating the pivotal role of GHRM in the dissemination of green innovation within organizations. The findings illustrate that management support for environmental initiatives is a critical factor in enhancing the effectiveness and spread of green innovation, emphasizing the importance of GHRM in the broader context of organizational change and sustainability.

The study underscores the critical role of transformational leadership in fostering sustainable practices, particularly the significant moderating role of responsible leadership in the GHRM–sustainable performance dynamic. This aligns with the findings of Ahmed [37] and Singh [26], indicating that green transformational leadership can amplify the efficacy of GHRM, thereby fostering an organizational culture conducive to sustainability and innovation.

Collectively, these theoretical perspectives provide a rich tapestry for understanding the complex interplay between GHRM and sustainable performance. The study contributes to the literature by highlighting the strategic importance of GHRM as a resource (RBV), its comprehensive contribution to sustainability (TBL), the facilitation of innovation diffusion (innovation diffusion theory), and the transformative role of leadership (transformational leadership theory) in driving sustainable business practices. These insights offer a nuanced and multifaceted understanding that is essential for future research and practice in sustainable human resource management.

7.2. Practical Implication

This study’s exploration of GHRM and its impact on sustainable performance in SMEs provides a nuanced understanding of how integrating sustainability into core business operations can yield both environmental and economic benefits. The emphasis on green product innovation is particularly noteworthy; our findings indicate that while GHRM positively influences both process and product innovation, it is through the latter that a more pronounced impact on sustainable performance is realized. This underscores the strategic importance for businesses not only to support but also to actively invest in environmental innovation, especially in the realms of product development and design.

The significance of GHRM practices extends beyond environmental stewardship. Our study illuminates the multifaceted nature of GHRM in fostering a capable and motivated workforce aligned with sustainability goals, encompassing areas such as green recruitment, training in environmental awareness, and sustainability-focused performance management systems. Furthermore, the study sheds light on the pivotal role of leadership. The moderating effect of responsible leadership in the interplay between GHRM and sustainable performance, particularly through product innovation, highlights the need for leaders who are ethically responsible and proactively engaged in environmental stewardship. This finding suggests a shift in leadership development programs towards incorporating sustainability as a core competency.

Importantly, the study draws attention to the criticality of embedding sustainability into the business strategy. The direct correlation between green product innovation and sustainable performance advocates for a paradigm shift, where sustainability is integral to business strategy, requiring businesses to commit to sustainability at all operational levels.

Moreover, cultivating a culture of sustainability within organizations is identified as a key factor. This goes beyond mere policy implementation; it requires instilling sustainability values into the organizational ethos, consistently promoting environmental responsibility, and fostering employee involvement in green initiatives.

The study also underscores the necessity of robust sustainability reporting. Effective monitoring and transparent reporting of environmental performance are crucial, enabling businesses to set clear sustainability targets, assess performance regularly, and communicate efforts transparently to stakeholders.

Additionally, the study’s findings relate to the economic performance implications of GHRM in SMEs. Our research reveals that GHRM practices not only contribute to environmental sustainability but also significantly impact the economic performance of SMEs. The adoption of GHRM leads to cost reductions, enhanced brand reputation, increased market appeal, and potentially higher sales and profitability. Furthermore, GHRM practices are shown to boost employee motivation and productivity, leading to further economic gains. This dual benefit of GHRM underscores its role as a strategic asset, enabling SMEs to achieve both sustainable and economic success.

In summary, this study provides a comprehensive roadmap for businesses, particularly SMEs, to use GHRM as a strategic tool in their sustainability journey. It calls for a holistic approach encompassing green HR practices, transformational leadership development, sustainability integration into business strategy, fostering a culture valuing environmental responsibility, and maintaining transparency in sustainability efforts. By implementing these strategies, businesses can effectively integrate environmental sustainability into their operations and strategic goals, achieving a balance between environmental stewardship and economic performance.

8. Limitations of This Study

The study on green human resource management (GHRM) and its impact on sustainable performance presents several limitations that warrant consideration for future research. Primarily, the sample size, though statistically adequate, was limited to SMEs in the Klang Valley region of Malaysia. This geographical concentration may restrict the applicability and generalizability of the findings to other regions or countries with different economic, cultural, and environmental backgrounds.

Additionally, the research employed a cross-sectional design, capturing data at a single point in time. This approach limits the ability to draw causal inferences or observe longitudinal changes and trends in GHRM practices and their impact on sustainable performance. To gain a more dynamic and comprehensive understanding, future studies could benefit from a longitudinal design that tracks these aspects over time.

The study also relied on self-reported data from survey respondents, which poses potential biases such as social desirability or variations in respondents’ interpretations of survey questions. To enhance the validity and reliability of findings, subsequent research could incorporate objective measures or employ multiple data sources for triangulation.

Another limitation is the focused scope of GHRM practices examined in the study. While it covered certain key aspects, it may not have encompassed the full range of GHRM practices that could significantly influence sustainable performance. Expanding the scope to include a broader spectrum of GHRM practices could provide a more holistic understanding of their impacts.

The study did not extensively address industry-specific factors that could influence the adoption and effectiveness of GHRM practices. Different industries may encounter unique challenges and opportunities in implementing GHRM, which could play a crucial role in shaping outcomes. Therefore, future research should consider these industry-specific dynamics.

Moreover, while the study explored the moderating role of responsible leadership, there are other potential moderating or mediating variables that might significantly influence the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance. Investigating additional factors could provide a more nuanced understanding of this relationship.

Finally, the study’s examination of the economic performance implications of GHRM was not as comprehensive as it could have been. A more detailed and varied approach in assessing the economic impacts of GHRM practices would be beneficial for future studies, providing deeper insights into the economic benefits of integrating GHRM into business strategies.

In summary, while the study offers valuable insights into the relationship between GHRM and sustainable performance in SMEs, these limitations highlight areas for further exploration and refinement in understanding this relationship more comprehensively. Future research addressing these limitations could significantly enhance our knowledge and application of GHRM in achieving sustainable and economic success in SMEs.

9. Conclusions and Future Directions

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of green human resource management (GHRM) within Malaysian SMEs, exploring the complex interplay between GHRM, green process and product innovation, and sustainable performance. A key finding is the strategic importance of product innovation in mediating the GHRM–sustainable performance relationship. While GHRM positively impacts both green process and product innovation, it is primarily through product innovation that a significant effect on sustainable performance is observed. This result aligns with and extends the research by Choudhary [38] and Hameed [39], who highlight the role of GHRM in fostering green creativity. Our study contributes to this body of knowledge by quantifying GHRM’s influence on specific types of innovation.

Furthermore, the study emphasizes the critical role of responsible leadership in enhancing the effectiveness of GHRM practices, particularly concerning product innovation. This finding complements insights from researchers like Hameed [39] and Al-Shammari [25], who note the importance of ethical and transformational leadership in realizing the full potential of GHRM practices. Although responsible leadership did not significantly moderate the GHRM–sustainable performance relationship through process innovation, its marked influence in the context of product innovation underscores the necessity of incorporating leadership styles that prioritize sustainability.

Additionally, the study reveals that the direct impact of GHRM on sustainable performance is more intricate and less straightforward than previously understood, challenging earlier assertions by Alenzi [50] and Al-Shammari [25]. This complexity suggests that a more nuanced and strategic approach to implementing GHRM practices is essential. By situating our findings within the context of the existing literature, this study not only contributes to the understanding of GHRM’s role in enhancing sustainable performance but also highlights the need for further research to explore these dynamic relationships.

Future research directions in this field are abundant and varied. Expanding the scope of research to include a broader geographical context could offer a more global understanding of GHRM practices. Industry-specific studies could provide insights into how GHRM is tailored to and functions within different sectors, potentially leading to more effective GHRM strategies. Longitudinal research would offer a dynamic perspective on the long-term impacts of GHRM on sustainable performance.

Exploring additional mediators and moderators in the GHRM–sustainable performance relationship, understanding the impact of external factors such as regulatory changes and market conditions, and incorporating qualitative research methods could all yield significant insights. These avenues promise to deepen the understanding of GHRM and enhance its practical application in promoting organizational sustainability. As this area of study evolves, it holds the potential to make substantial contributions to both academic knowledge and practical business strategies in sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and Z.K.M.M.; data curation, W.Z.; formal analysis, W.Z.; investigation, W.Z.; software, W.Z.; supervision, Z.K.M.M.; validation, Z.K.M.M. and W.Z.; visualization, W.Z.; writing—original draft, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and Z.K.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the fact that the study was conducted as per the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research questionnaire was anonymous, and no personal information was gathered.

Informed Consent Statement

Oral consent was obtained from all individuals involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their efforts to improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Joshi, A.; Kataria, A.; Rastogi, M.; Beutell, N.J.; Ahmad, S.; Yusliza, M.Y. Green Human Resource Management in the Context of Organizational Sustainability: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Jackson, S.E. HRM Institutional Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Business Organizations. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Harry, W. Recent Developments and Future Prospects on Sustainable Human Resource Management: Introduction to the Special Issue. Manag. Rev. 2012, 23, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda*. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The Central Role of Human Resource Management in the Search for Sustainable Organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2133–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Muller-Camen, M. State-of-the-Art and Future Directions for Green Human Resource Management: Introduction to the Special Issue. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Z. Für Pers. 2011, 25, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opatha, H.; Anton, A. Green Human Resource Management: A Simplified General Reflection. Int. Bus. Res. 2014, 7, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.; Riggio, R. Transformational Leadership; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul, T.B.; Ahmed, A.Z.; Ayham, J. Green Human Resource Management, Green Supply Chain Management Practices and Sustainable Performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Bandung, Indonesia, 6–8 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Chin, T.; Hu, D. The Continuous Mediating Effects of GHRM on Employees Green Passion via Transformational Leadership and Green Creativity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business, 1st ed.; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: Florence, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. From Transactional to Transformational Leadership: Learning to Share the Vision. Organ. Dyn. 1990, 18, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H.; Xu, H. Effects of Green Human Resource Management and Managerial Environmental Concern on Green Innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, C.N.; O’Donnell, M.B.; Tinney, F.J.; Lieberman, M.D.; Taylor, S.E.; Strecher, V.J.; Falk, E.B. Self-Affirmation Activates Brain Systems Associated with Self-Related Processing and Reward and Is Reinforced by Future Orientation. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezen, B.; Çankaya, S.Y. Effects of Green Manufacturing and Eco-Innovation on Sustainability Performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeshen, Y.; Soomro, Y.A.; Bhutto, M.Y. Determinants of Green Innovation to Achieve Sustainable Business Performance: Evidence From SMEs. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 767968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Huo, J.; Zou, H. Green Process Innovation, Green Product Innovation, and Corporate Financial Performance: A Content Analysis Method. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanan, M.; Taha, B.; Saleh, Y.; Alsayed, M.; Assaf, R.; Ben Hassen, M.; Alshaibani, E.; Bakir, A.; Tunsi, W. Green Innovation as a Mediator between Green Human Resource Management Practices and Sustainable Performance in Palestinian Manufacturing Industries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Shi, S.; Gao, J.; Li, X. The Mediating Role of Green Innovation and Green Culture in the Relationship between Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Performance. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.K.; Khan, T.I.; Islam, S.U.; Abdullah, F.Z.; Pradana, M.; Kaewsaeng-on, R. Impact of Green HRM Practices on Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Innovation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A.-N.; Singh, S.K. Green Innovation and Organizational Performance: The Influence of Big Data and the Moderating Role of Management Commitment and HR Practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zheng, X. How Does Corporate Learning Orientation Enhance Industrial Brand Equity? The Roles of Firm Capabilities and Size. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 35, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad Al-Shammari, A.S.; Alshammrei, S.; Nawaz, N.; Tayyab, M. Green Human Resource Management and Sustainable Performance with the Mediating Role of Green Innovation: A Perspective of New Technological Era. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 901235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green Innovation and Environmental Performance: The Role of Green Transformational Leadership and Green Human Resource Management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.K.; Othman, M. The Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices on Sustainable Performance in Healthcare Organisations: A Conceptual Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrucci, L.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. The Contribution of Green Human Resource Management to the Circular Economy and Performance of Environmental Certified Organisations. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyadi, A.; Natalisa, D.; Poór, J.; Perizade, B.; Szabó, K. Predicting the Relationship between Green Transformational Leadership, Green Human Resource Management Practices, and Employees Green Behavior. Adm. Sci. 2022, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney, M.T.; Wang, N.; Nazir, M.; Ferasso, M.; Saeed, A. Continuous Effects of Green Transformational Leadership and Green Employee Creativity: A Moderating and Mediating Prospective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 840019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahakwa, I.; Yang, J.; Agba Tackie, E.; Asamany, M. Green Human Resource Management Practices and Environmental Performance in Ghana: The Role of Green Innovation. SEISENSE J. Manag. 2021, 4, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, S.; Farmanesh, P.; Khademolomoom, A.H. Effects of Green Human Resource Management on Innovation Performance through Green Innovation: Evidence from Northern Cyprus on Small Island Universities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muisyo, P.K.; Qin, S. Enhancing the FIRMS Green Performance through Green HRM: The Moderating Role of Green Innovation Culture. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D.; Pandey, S.; Wright, B. Transformational Leadership in the Public Sector Empirical Evidence of Its Effects; Routledge: Lndon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muenjohn, N. Transformational Leadership: A New Force in Leadership Research; YUMPU: Diepoldsau, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Iftikhar, U.; Zaman, K.; Rehmani, M.; Ghias, W.; Islam, T. Impact of Green Human Resource Management on Service Recovery: Mediating Role of Environmental Commitment and Moderation of Transformational Leadership. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 710050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.; Soleman, M.; Zaman, F. Green HRM and Green Innovation: Can Green Transformational Leadership Moderate: Case of Pharmaceutical Firms in Australia. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 616–617. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, P.; Datta, A. The Significance of GHRM in Fostering Hospitality Employees Green Creativity: A Systematic Literature Review with Bibliometric Analysis. J. Inf. Optim. Sci. 2022, 43, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, Z.; Naeem, R.M.; Hassan, M.; Naeem, M.; Nazim, M.; Maqbool, A. How GHRM Is Related to Green Creativity? A Moderated Mediation Model of Green Transformational Leadership and Green Perceived Organizational Support. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 43, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, H.A.; Jaaron, A.A.M. Assessing Green Human Resources Management Practices in Palestinian Manufacturing Context: An Empirical Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Rabiei, S.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. Envisioning the Invisible: Understanding the Synergy between Green Human Resource Management and Green Supply Chain Management in Manufacturing Firms in Iran in Light of the Moderating Effect of Employees’ Resistance to Change. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, S. Reviewing the Concept of Green HRM (GHRM) and Its Application Practices (Green Staffing) with Suggested Research Agenda: A Review from Literature Background and Testing Construction Perspective. Int. Bus. Res. 2019, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Green Human Resource Management and Green Supply Chain Management: Linking Two Emerging Agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Chong, T. Green Human Resource Management and the Enablers of Green Organisational Culture: Enhancing a Firm’s Environmental Performance for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirawuttinunt, S. The Relationship between Green Human Resource Management and Green Intellectual Capital of Certified ISO 14000 Businesses in Thailand. St. Theresa J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 14000; Environmental Management. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Alenzi, M.A.S.; Jaaffar, A.H.; Khudari, M. The Mediating Effect of Organisational Sustainability and Employee Behaviour on the Relationship between GHRM and Sustainable Performance in Qatar. Wseas Trans. Bus. Econ. 2022, 19, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, I. How Systematic Quality Control Affects Suppliers Socioeconomic Sustainability and the Stability of the Buyersupplier Relationship: A Case of the Garment Industry in Bangladesh. In Upgrading the Global Garment Industry; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 306–338. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Pasha, U. GSCM, GHRM and Sustainable Performance: Does External Pressures Matter? Environ. Sci. Bus. 2022, 20, 481–499. [Google Scholar]

- Alenzi, M.A.S.; Jaaffar, A.H.; Khudari, M. The Effect of GHRM on the Sustainable Performance of Private Companies in Qatar. Int. J. Manag. Sustain. 2023, 12, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Kusi, M.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.; Ahmed, F.; Sukamani, D. Influencing Mechanism of Green Human Resource Management and Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Sustainable Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Y.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Wah, W.-X. Pursuing Green Growth in Technology Firms through the Connections between Environmental Innovation and Sustainable Business Performance: Does Service Capability Matter? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majali, T.; Alkaraki, M.; Asad, M.; Aladwan, N.; Aledeinat, M. Green Transformational Leadership, Green Entrepreneurial Orientation and Performance of SMEs: The Mediating Role of Green Product Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.-H.; Chen, J.-S.; Chen, P.-C. Effects of Green Innovation on Environmental and Corporate Performance: A Stakeholder Perspective. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4997–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ar, I.M. The Impact of Green Product Innovation on Firm Performance and Competitive Capability: The Moderating Role of Managerial Environmental Concern. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 62, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.A. Impact of GHRM on Organizations Environmental Performance: Mediating Role of Green Employee Empowerment. J. Bus. 2021, 6, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku Mensah, A.; Afum, E.; Sam, E.A. Does GHRM Spur Business Performance via Green Corporate Citizenship, Green Corporate Reputation and Environmental Performance? Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragas, S.F.P.; Tantay, F.M.A.; Chua, L.J.C.; Sunio, C.M.C. Green Lifestyle Moderates GHRMs Impact on Job Performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2017, 66, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyaningrum, R.P.; Muafi, M. Green Human Resources Management on Business Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Product Innovation and Environmental Commitment. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2023, 18, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Seman, N.A.; Govindan, K.; Mardani, A.; Zakuan, N.; Mat Saman, M.Z.; Hooker, R.E.; Ozkul, S. The Mediating Effect of Green Innovation on the Relationship between Green Supply Chain Management and Environmental Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; Jackson, S.E. Effects of Green HRM and CEO Ethical Leadership on Organizations’ Environmental Performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 42, 961–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarova, L.; Jo, S.-J. Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Impact of Environmental Transformational Leadership and GHRM. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.; El Irani, M.; Kertechian, K.S. Green HRM and Nongreen Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Visionary Leadership in Asia. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 43, 660–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.A.E.; Ejaz, F.; Ejaz, S. Green Transformational Leadership, GHRM, and Proenvironmental Behavior: An Effectual Drive to Environmental Performances of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, L. The Influence of Ethical Leadership and Green Organizational Identity on Employees Green Innovation Behavior: The Moderating Effect of Strategic Flexibility. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 237, 52012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Yang, C.; Bossink, B.A.G.; Fu, J. Linking Leaders Voluntary Workplace Green Behavior and Team Green Innovation: The Mediation Role of Team Green Efficacy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H. Influence of Environmentally Specific Transformational Leadership on Employees Green Innovation Behavior—A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, M. The Influence of Responsible Leadership on Environmental Innovation and Environmental Performance: The Moderating Role of Managerial Discretion. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2016–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, L. The Impact of Organizational Innovation Culture on Employees’ Innovation Behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2022, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Y.; Sarfraz, M.; Khalid, R.; Ozturk, I.; Tariq, J. Does Corporate Social Responsibility and Green Product Innovation Boost Organizational Performance? A Moderated Mediation Model of Competitive Advantage and Green Trust. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2022, 35, 5379–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azungah, T. Qualitative Research: Deductive and Inductive Approaches to Data Analysis. Qual. Res. J. 2018, 18, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C. Quantitative, Cross-Sectional Survey Utilising the Corporate Entrepreneurship Assessment Instrument (CEAI) to Describe Middle Managers’ Perceptions of a South African Firm’s Internal Environment in 2018. Master’s Thesis, The IIE’s Varsity College, Westville, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Haque, R.; bin S Senathirajah, A.R.; Chowdhury, B.; Khalil, M.I. Examining the Mediation Effect of Organizational Response Towards COVID-19 on Employee Satisfaction in SMEs. Int. J. Oper. Quant. Manag. 2022, 28, 461–485. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Chowdhury, B.; Khalil, I.; Haque, R.; bin Senathirajah, A.R. Analyzing Key Factors Affecting Sales Performance amongst Malaysian Smes: A Structural Path Modeling Approach. Int. J. Ebusiness Egovernment Stud. 2022, 14, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2022; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; ISBN 9789264419025.

- Khalil, M.I.; Haque, R.; bin S Senathirajah, A.R.; Chowdhury, B.; Ahmed, S. Modeling Factors Affecting SME Performance in Malaysia. Int. J. Oper. Quant. Manag. 2022, 28, 506–524. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, A. Non-Probability Sampling. In Encyclopedia of Social Measurement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 859–864. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Chavez, R.; Feng, M.; Wong, C.Y.; Fynes, B. Green Human Resource Management and Environmental Cooperation: An Ability-Motivation-Opportunity and Contingency Perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Govindan, K.; Iranmanesh, M.; Shaharudin, M.R.; Sia Chong, Y. Green Innovation Adoption in Automotive Supply Chain: The Malaysian Case. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Rashid, M.A.; Hussain, G.; Ali, H.Y. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Reputation and Firm Financial Performance: Moderating Role of Responsible Leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, W.-L.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F. Internet Research Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Internet Res. 2019, 29, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]