Abstract

Human rights violations in sports reveal that athletes are continuously exposed to violence. In Korea, the negative effects of its sports powerhouse paradigm are increasingly apparent. Although discussions on human rights in sports have progressed, academic research on this has not. Sourcing information from Korea’s Press Foundation’s big data news system from 2006 to 2023, this study used term frequency, term frequency-inverse document modeling, topic term matrix extraction through latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), and LDAvis to analyze sports human rights issues and policies over time. The results revealed topics in three timeframes: in the first policy establishment period (2006–2010), the topics ranged from “Sports Human Rights Education” to “Minimum Education for Student Athletes”. In the policy transition period (2011–2018), the topics included “Strengthening Sports Human Rights Education”, “Women’s Human Rights Issues in Sports”, and “Government-Level Investigation into Sportsdom Controversies”; and in the second policy establishment period (2019–2023), the topics included “Athlete Harassment”, “Sportsdom #MeToo Movement”, “Guarantee of Student Human Rights Convenience Facilities”, and “Guarantee of Sports Human Rights”. Better mid- to long-term plans, national efforts, and education that improve awareness of human rights in sports are needed for sustainability.

1. Introduction

Recently, human rights violations in sports have emerged as a serious societal concern. Instances such as the sexual violence targeting elite short-track speed skaters in 2019 and the 2020 suicide of a triathlete attributed to the harsh treatment from leaders and fellow athletes have deeply impacted the nation. The main cause of these tragic incidents is the abnormal structure of Korea’s elite sports aimed at promoting national prestige. Everyone has the right to be physically and emotionally safe and free from all forms of violence when participating in sports [1]. However, many human rights violations in sports have been reported worldwide and in the Korean media. These reports offer evidence that individuals participating in sports are frequently exposed to violence. Human rights violations in sports in Korea are said to stem from a culture in which violence is tolerated and therefore repeated. Specifically, this has encouraged a sports powerhouse paradigm through triumphalism [2]. In Korea, a national-led minority of elite athletes are concentrated/cultivated to win medals in international competitions and are rewarded with pensions and military exemptions. This is a nationwide sports policy aimed at achieving economic growth and enhancing national prestige in Korea through the successful hosting of international sports events (e.g., 1986 Asian Games, 1988 Olympics, 2002 Korea–Japan World Cup, 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics, etc.) [3]. However, as cases of human rights violations in sports continue to be publicized, the negative side effects of the sports powerhouse paradigm are becoming more apparent. As the times and society change, Korean citizens no longer regard any human rights violation in sports as a “possible occurrence”. In other words, since the 2000s, cases of human rights violations in sports not previously recognized began to be acknowledged as social problems requiring practical and academic attention. Based on this recognition, Korea’s National Human Rights Commission created a special committee to evaluate human rights in sports, and with this, a large-scale investigation into human rights violations in sports began with discussions of various corrective sustainable measures. Since then, such discussions on human rights in sports have progressed rapidly, with measures to improve human rights for athletes increasing at national and local levels. However, academic research on this has not kept pace. The Declaration of Human Rights from the International Olympic Committee in 1996 marked a pivotal moment, highlighting the intersection of sports, politics, and human rights. It underscored the crucial role of athletes in fostering democracy and equality. Building on this, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) published in 2015 aimed to address social inequality and promote peace and sustainable development through sports. The concept of sustainable sports human rights encompasses protecting and respecting human rights across all facets of sports activities. It involves upholding principles such as equality, fair treatment in sports participation, safety, health, social responsibility, education, regulation, and supervision. Adhering to these principles enables sports development in a more equitable, safe, and sustainable manner.

This study seeks to determine what a sustainable sports human rights policy could be. Sustainable sports human rights policies can encompass a variety of issues, from human rights and equality in the field of sports to environmental protection and economic development. We aim to fill this gap in the literature by studying this problem in Korea and providing insights into the policies needed to address human rights in sports today and in the future. To that end, we analyze existing human rights policies in sports based on recent trends in Korean society and Korea’s policies using big data from the Korea Integrated Newspaper Database System (KINDS). Through this, we can examine objective and basic academic data, enabling sustainable strategic national policy interventions to improve such rights in sports. Our analysis finds that although Korea’s policies on sports human rights have expanded, these government-led policies have not been ineffective due to issues of unsustainability. Better mid- to long-term plans, national efforts, and education that improve awareness of human rights in sports are needed to make such policies sustainable.

2. Review of the Literature

Examining the current status of research on human rights issues in Korean elite sports reveals a predominant focus on “factual surveys”. The central inquiry into sports human rights revolves around safeguarding the human rights of elite sports athletes. However, recent studies in this field predominantly concentrate on documenting the challenges faced by elite athletes, often presented as factual surveys. This heightened awareness and interest in sports human rights emerged in the late 2000s due to reported cases of (sexual) violence and various human rights issues within elite groups [4]. Surveys on human rights in sports in Korea have primarily been led by the National Human Rights Commission and the Korea Sports Council. Since 2021, the Sports Ethics Center has also been surveying student and professional business team players. Notably, the National Human Rights Commission has been investigating student athletes’ human rights, learning rights, violence, and sexual violence since 2006 [5]. Simultaneously, the Korea Sports Council has been conducting surveys on (sex) violence in sports involving student athletes, leaders, national athletes, leaders, and parents since 2005 [6]. Research on the human rights of student athletes predominantly focuses on violations of their right to education [7,8,9,10,11,12], violence in school sports teams [9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], and the basic sports rights of student athletes [19,20].

This is due to the special nature of research on human rights in sports, with academic attention on incidents representing social problems centered in the media and civil society (e.g., the violation of Jang Hee-jin’s right to study, the Cheonan Elementary School dormitory fire incident, etc.). The discourse on “guaranteeing the right to learn” emphasizes educational value, resocialization, and basic rights, reinforcing that student athletes must be guaranteed the right to education as students rather than as athletes [21]. Not all student athletes succeed as professional athletes in Korea and elsewhere; therefore, a lack of education hinders their academic and social adaptation when seeking other careers. In terms of violence in sports, this has been implicitly tolerated based on the assumption that “a certain degree of violence or corporal punishment is an extension of the training necessary to improve performance or mental strength” [13]. In the closed environment of sports, depicted as a kind of island culture, routine violence occurs in stadiums, on training grounds, and in training camps. In addition, through the internalization of violence, victims become perpetrators in the future and thus become part of the mechanism that perpetuates violence and a violent culture [22]. In addition, by examining laws, institutions, and policies addressing sports human rights issues, this study entailed analyzing existing laws foundational for human rights protection. This involved investigating and analyzing potential revisions to current laws, studying provisions related to human rights within the legal framework and system, and human rights and societal perspectives [14,23,24,25,26,27,28].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Procedure

We aim to provide objective insights into human rights in Korean sports by scouring news data related to such rights over the past few decades. This allowed us to identify the policies designed and evolved to address these issues. Our research approach was as follows.

3.2. Data Collection

As stated, we began by collecting data from the Korea Integrated Newspaper Database (KIND), the Korea Press Foundation’s big data news source. We collected data related to sports human rights from 54 media outlets between 1 January 2006 and 31 July 2023. Based on the evolution of national sports policy interventions as Korean sports human rights became a social issue, we divided this timeframe into three periods: the first policy establishment period (2006–2010), a policy transition period (2011–2018), and a second policy establishment period (2019–2023) [29]. While there may be diverse opinions on the optimum criteria for categorizing policies by period, this study adopted the measure proposed by Hong [29], which assesses a country’s proactive involvement in sports human rights by introducing its sports human rights policies as the basis for classification. The initial period, the first policy establishment period (2006–2010), was identified when a government-level survey on human rights violations in sports took place, accompanied by formulating policies related to sports human rights. The subsequent period, from 2011 to 2018, was characterized as a policy transition period, marked by a notable reduction in the involvement of the National Human Rights Commission and the government in sports human rights policies. Finally, as incidents related to sports human rights issues surged and prompted renewed government intervention, the period from 2019 to 2023 was designated the second policy establishment period.

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sookmyung Women’s University (No. SMWU-2308-HR-051).

3.3. Text Mining

In the first step of our analysis, we employed text mining. Text mining extracts information using natural language processing technology, which records communication information using human natural language as unstructured data [30] and analyzes and concretizes the relationships between interrelated words [31]. Text mining classifies words into morphemes. These are the smallest units in a word, which are then interpreted in the context of a sentence based on meaning [32]. Ultimately, text mining extracts information from data sources to discover new information and patterns [33,34]. We applied a word normalization process to the articles we collected using the R program’s KoNLP package and NIADic (Korean Morphological Dictionary). This process involved the removal of special symbols, punctuation marks, numbers, meaningless stop words, and spaces. Nouns were extracted through the Korean morpheme analysis, words with the same meaning were integrated, and meaningless single-letter words were excluded from the analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Text mining examples.

3.4. Data Analysis

To check the frequency of words, we converted the document term matrix (DTM) of the refined data, extracting words that appeared with high frequency using term frequency (TF)–inverse document frequency (IDF). Although TF captures the frequency of words in a document, the TF value can increase if stop words (such as postpositions, articles, and adverbs) appear frequently. Therefore, IDF is introduced to calculate the weighted IDF value [35]. For this, we used R-studio’s Wordcloud package to extract each document’s TF values and important words within the document (IDF) and visualize words that appeared with high frequency.

3.5. Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) Topic Modeling

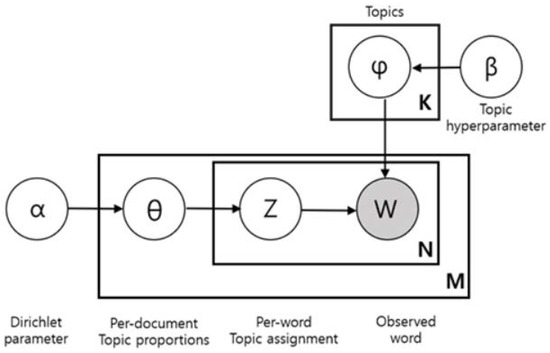

This study also employed LDA topic modeling. The rationale for this choice lies in the diverse analysis directions in existing text analysis, the challenge of comprehending the intricate social and cultural aspects within the research results, and the potential to simplify the findings [36]. This process collects words related to a topic by extracting the topics from a set of documents without any involvement from the researcher [37], as it can extract topics through a probabilistic model [38,39,40,41]. As an automated text analysis algorithm that considers large amounts of text [22,30], it is an inductive analysis method that can discover text structures [42]. The algorithm finds topics in a set of words in a document and considers the relational characteristics of their meaning in various contexts [38] by analyzing the corpus of words [43]. This statistical technique identifies the connection between topics and the probability distribution for the words expressing each topic [38,44]. Therefore, the results do not depend on the researcher’s interpretation but rather have the advantage of being consistent when using the same data [21]. Figure 1 illustrates the LDA document creation process. In this representation, N denotes the number of words in a document, M represents the total number of documents, and K indicates the total number of topics; α and β are the parameters associated with the subject distribution for each document and the word distribution for each subject, respectively. Consequently, LDA analysis determines W based on the β value, representing word distribution by subject, and assigns a subject assignment value Z to each word [44]. LDAvis gauges topic similarity and condenses it to convey the relevance of each topic in two dimensions [45].

Figure 1.

LDA document generation process.

As researchers, we can arbitrarily set the number of topics, but with limited expert knowledge about the content, we cannot easily select the appropriate number [19]. For this reason, we applied topic modeling by repeatedly measuring the coherence and perplexity, checking the extent to which topics are classified. The number of topics for each period was selected using the harmonic mean value [16], determined by the number of topics at the highest point. We extracted the topic term matrix through LDA and then applied LDAvis to visualize it. LDAvis shows the distribution of topics by reducing the number of dimensions by the number of terms. It shows the relevance of the terms associated with each topic according to the distance between topics. An overlap or close distance indicates a high correlation between the terms and topics.

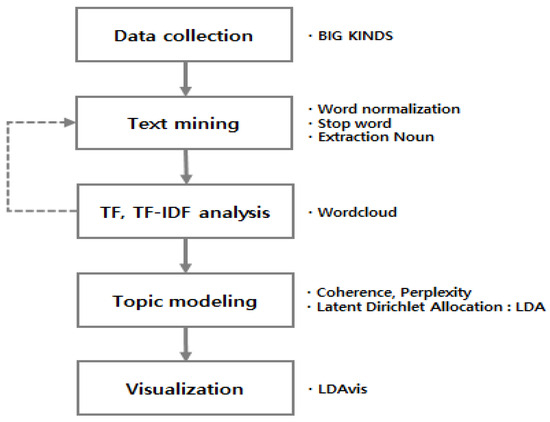

Our research model is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research model.

4. Results

4.1. Data Collection and Text Mining

As a result of searching “Sports Human Rights“ in KINDS, the big data news analysis system, we found 1821 cases during the first policy establishment period (2006–2010), 4663 cases during the policy transition period (2011–2018), and 6938 cases during the second policy establishment period (2019–2023), comprising a total of 13,442 cases. After excluding articles unrelated to sports and duplicate articles, we ended with 3992 news articles for our analysis. This included 280 articles from the first policy establishment period, 687 articles from the policy transition period, and 3025 articles from the second policy establishment period. Table 2 presents the number of terms extracted through data refinement.

Table 2.

Number of extracted articles and terms by period.

4.2. TF, TF–IDF, TF Visualization

We found the following frequently referenced terms in each of the periods, listed in order: In the first policy establishment period: Sports (150), Human Rights Commission (103), Violence (91), Sexual Violence (89), and Human Rights (78), with the TF–IDF values ranked as Sports (6.177), Sexual Violence (5.641), Education (5.481), Violence (5.32), and Human Rights Commission (5.239). In the policy transition period: Education (263), Sports (247), Sports Human Rights (211), Object (187), and Sexual Violence (170), with the TF–IDF values ranked as Education (16.847), Sports Human Rights (14.214), Provincial Sports Council (13.595), Sports (13.014), and Grand Prize (12.529). In the second policy establishment period: Sportsdom (1283), Sexual Violence (975), Violence (885), Coach (840), and Sports (780), with the TF–IDF values ranked as Sportsdom (56.863), Human Rights Commission (55.997), Sexual Violence (55.782), Coach (53.094), and Victim Athlete A (50.593). The frequency of the terms appearing in each period and the top 30 TF–IDF terms are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Term frequency and inverse document frequency results by period.

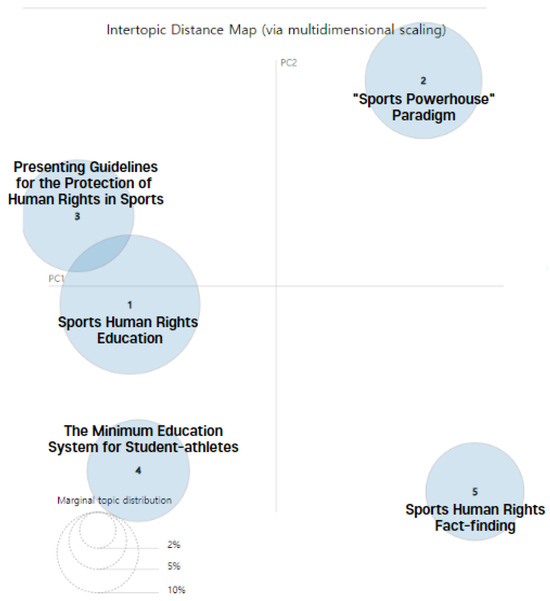

4.3. LDA Topic Modeling: First Policy Establishment Period (2006–2010)

Based on the LDA limitation of arbitrarily designating the number of topics, we chose the number of topics and repeatedly checked the coefficient of coherence and perplexity. The number of topics chosen for the first policy establishment period was five (N): topic one was “Sports Human Rights Education”, with a quota of 29.6%, assuming terms belonging to each topic. The second topic (quota 20.6%) was classified as the “Sports Powerhouse Paradigm” topic. Topic three had a quota of 19.2%, and included content about establishing a sports human rights charter and guidelines. Topic four (quota 15.9%) included content about the minimum education system for student-athletes and content related to guaranteeing the right to learn for elite athletes. Topic five (quota 14.6%) included a fact-finding survey on controversies in human rights in sports conducted in 2008, reporting accusations of widespread corruption and violence. The matrix output values of the topic terms corresponding to each topic and the estimated terms under each topic are listed in Table 4 and visualized in Figure 3.

Table 4.

LDA topic modeling during the first policy establishment period (2006–2010).

Figure 3.

LDAvis for the first policy establishment period (2006–2010).

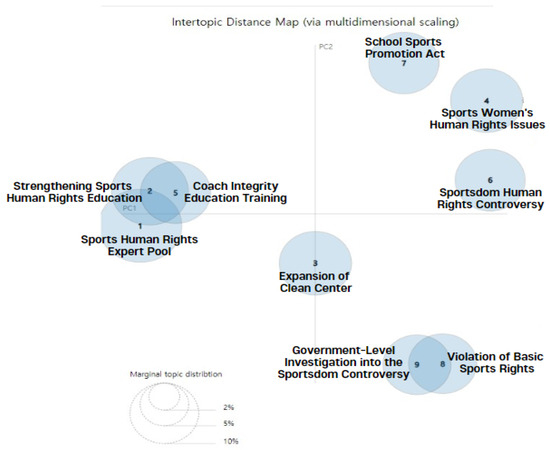

4.4. LDA Topic Modeling: Policy Transition Period (2011–2018)

For the policy transition period, we selected nine (N) topics. Topic one had a quota of 14.6%, and represented a pool of sports human rights experts. Topic two had a quota of 12.5%, capturing the strengthening of sports human rights education. Topic three had a quota of 11.1%, including a cleanup center operated as part of a measure to eradicate sports crime and corruption. Topic four had a quota of 11%, representing women’s human rights issues in sports. Topic five corresponded to human rights education for sports coaches and was labeled “Integrity Education Training for Coaches” (quota 10.5%). Topic six concerned players’ human rights violations, with a quota of 10.4%. Topic seven addressed the “School Sports Promotion Act”, having a quota of 10.4%, and topic eight captured protecting the human rights of athletes, with a quota of 9.8%. Topic nine, the last topic, with a quota of 9.8%, related to a fact-finding investigation into various controversies occurring in sports. The matrix output values of the topic terms corresponding to each topic and the estimated terms under each topic are listed in Table 5 and visualized in Figure 4.

Table 5.

LDA topic modeling during the policy transition period (2011–2018).

Figure 4.

LDAvis for the policy transition period (2011–2018).

4.5. LDA Topic Modeling: Second Policy Establishment Period (2019–2023)

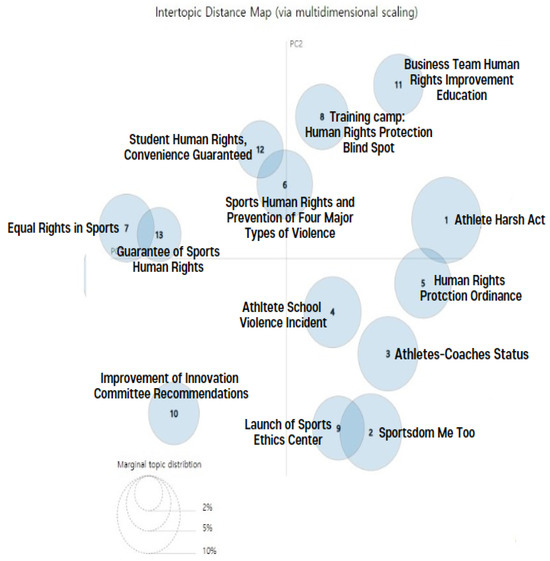

For the second policy establishment period, we selected 13 (N) topics. Topic one had a quota of 12.2% and concerned athletes’ extreme choices caused by harassment. Topic two, with a quota of 9.8%, related to the “#MeToo” movement in sports among sports athletes. Topic three addressed the relationship between athletes and coaches, related to controversies between the victim and the perpetrator (quota 9.2%). Topic four had a quota of 8.4%, highlighting incidents within school sports teams and stories about professional athletes’ past school violence. Topic five had a quota of 8.1% and concerned human rights protection ordinances. Topic six had a quota of 7.8% and addressed implementing education on human rights in sports and preventing four major types of violence. Topic seven had a quota of 7.6% and related to sports equality rights. Topic eight had a quota of 7.1% and concerned blind spots in training camps, for example. Topic nine had a quota of 6.8% and addressed the launch of the Sports Ethics Center. Topic 10 (quota of 6.5%) was related to announcing the Sports Innovation Committee’s recommendations, which aim to guarantee student athletes the right to learn and normalize their classes. Topic 11 had a quota of 6.3% and concerned the necessity and implementation of human rights education for athletes and coaches in professional teams. Topic 12 had a quota of 5.4% and related to guaranteeing student human rights convenience facilities in school sports classes. Finally, topic 13 had a quota of 4.9% and included guaranteeing human rights in sports. The matrix output values of the terms corresponding to each topic and the estimated terms under each topic are listed in Table 6 and visualized in Figure 5.

Table 6.

LDA topic modeling for the second policy establishment period (2019–2023).

Figure 5.

LDAvis for the second policy establishment period (2019–2023).

5. Discussion

This research explored different ways to create sustainable sports human rights policies. Following the LDAvis analysis conducted for the initial policy establishment period (2006–2010), it was observed that topic one (“Sports Human Rights Education”) and topic three (“Sports Human Rights Protection Guidelines”) exhibited a strong correlation.

The implication is that a sports human rights education was established using the Sports Human Rights Guidelines manual established by the National Human Rights Commission during this timeframe. In addition, the introduction of a system that guaranteed the right to study for student athletes, as part of establishing a school sports department management system in 2010, established the minimum education system for student athletes as a national policy. Topic five captures sports corruption, violence, and sexual violence based on a broadcast report conducted in 2008, confirming that the issue of widespread human rights violations in sports had surfaced.

From the LDA analysis of the first policy establishment period (2006–2010), similar to the reports on student athlete human rights from 2008 to 2009 [46], the issues in this period once again were confirmed as including violence and sexual violence, the need to guarantee the right to education, and the establishment of sports human rights policies. Concurrently, Korean sports were focused on the elite athlete training system, and due to the hierarchical relationship caused by triumphalism and a closed training camp culture, victims were forced to be silent about violence and sexual violence between coaches and athletes and between seniors and juniors [20,47,48]. In other words, violence and sexual violence in sports resulted from the structure of the system (strukturelle Gewalt) expressed as an unequal social culture [49,50]. The system included various crimes, with the damage ultimately being concealed. Since 2006, the Korean Sports & Olympic Committee has implemented training to protect athletes’ human rights through joint education provided by the city and province. In 2008, the Korean Sports & Olympic Committee Athlete Protection Committee established comprehensive measures related to sports violence and sexual violence, including the permanent expulsion of perpetrators and the establishment of guidelines for preventing sports sexual violence. In addition to violence and sexual violence, discussions were also held on guaranteeing student athletes the right to learn. Studies on student athletes during the first policy establishment period argue that the infringement of the right to learn in the name of special education for student athletes is not only an infringement of a student’s basic rights but is directly related to their right to live, because it affects their ability to choose a job and life after no longer participating in their sport [40]. This suggests that the limitation of students’ right to learn results from the elite athlete training system [21]. Thus, new policies have been promoted to improve the quality of life and welfare of student athletes outside of elite sports. Sustainability-based sports human rights policies are the most effective approach to solving urgent problems in Korean society. Ensuring the rights and welfare of student athletes, including their freedom of expression and protection from abuse and harassment in the first policy establishment period, is the core of sustainable sports human rights and the government’s active attempts to resolve sports human rights issues in Korea.

Looking at the LDAvis results for the policy transition period (2011–2018), topics one, two, and five were adjacent; these were the “Pool of Sports Human Rights Experts”, “Strengthening Sports Human Rights Education”, and “Integrity Education Training for Coaches” topics. As most perpetrators of sexual violence in sports appear to be coaches, the IOC has adopted the “Consensus Statement Sexual Harassment & Abuse in Sports”, which states that policies should include implementation, education, training, surveillance, and evaluation to prevent and respond to sexual violence. In 2010, Korea issued recommendations for human rights guidelines to strengthen human rights education in sports [51]. During the policy transition period, discussions were held to resolve human rights issues in sports by launching a special committee for sports innovation. The Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, and the Prosecution Service launched a joint investigation committee to eradicate the four major evils of sports with the Sports 3.0 Committee (a sports policy advisory body). However, scholars indicate that effective measures were not drawn up because they could not be implemented and enforced regularly [29,52].

Topics eight, nine, and six were also found to be adjacent. The implication is that public opinion called for a fact-finding investigation to be conducted by the government into the infringement of basic rights in sports and various controversies over human rights. Other human rights issues, besides violence and sexual violence, emerged during the policy transition period, such as gender-related controversies around female soccer players and closed-circuit surveillance of professional baseball players. Athletes have the right to human dignity and the right to pursue happiness; thus, the active consideration of the state, individuals, and organizations cannot be neglected as a basic principle of the constitution [53]; sexual controversy arising over female sports players being considered unfeminine is a serious human rights violation. Regarding the closed-circuit inspection of professional players in 2014, the club violated the athletes’ personal information. This raised sports human rights awareness concerning athletes’ personal information being perceived as belonging to their club [54]. The definition of human rights states that “everyone born with dignity is free and equal, and these freedoms and equality cannot be violated [55]”. Just because one is an athlete does not mean that this role can be given priority over one’s right to freedom. These human rights issues point to the need for sports human rights education to go beyond sports violence and sexual violence [56]. In addition, to resolve other human rights issues, including match fixing, doping, and scouting corruption in the realm of sports, discussions should be held on the purpose and direction of education on sustainable sports human rights. This can raise awareness regarding the sustainability of human rights in sports among all stakeholders in the sports field, including athletes, fans, and the general public.

The LDAvis analysis for the second policy establishment period identified the following topics: topic two, which captured the “Sportsdom #MeToo Movement”, was closest to topic three: “Athlete–Coach Relationships”; topic four: “Athletes’ Violent Incidents in School”; topic five: “Human Rights Protection Ordinances”; and topic one: “Athlete Harassment”. The sportsdom #MeToo movement followed the spread of the general #MeToo movement in 2018. The issue of violence and sexual violence in sports once again came to the surface when an athlete revealed personal damage from sexual violence from a coach lasting about four years. Other various human rights issues were exposed in this period as well, such as an athlete who suffered continuous abuse from leaders and coaching staff, past school violence controversies among professional athletes, and sexual harassment of fellow athletes. According to the project results report released by the Korean Sports & Olympic Committee [57], from 2009 to 2019, the total number of training sessions, including national athletes, match organizations, city and provincial training, and on-site training, was estimated to be 3000 or more, with the number of participants being 280,000. However, according to the National Human Rights Commission of Korea’s [58] study on the charter of sports human rights and the improvement of guidelines, about 25% of incumbent athletes were unaware of how to respond when faced with a damaging situation. This indicates that sports human rights education has not been properly conducted at national and local government levels for over 10 years. In addition, the terms belonging to each topic of the second policy establishment period included Blue House, President, Minister, and National Assembly with high frequency, suggesting that public opinion regarding sports human rights issues should be investigated and resolved at the national level.

Despite the public’s interest in sports human rights issues and the implementation of sports human rights education at the national level, violence and sexual violence have been openly committed for many years. This implies the need to assess whether sports human rights education is being implemented properly to reflect the unique structure of elite sports. In particular, the vicious cycle of human rights violations in elite Korean sports, which combines nationalism and familism in a closed structure, implies that not just individual awareness but the whole structure of sportsdom must change [59]. Therefore, it is necessary to establish an effective mechanism to enforce a sustainable human rights policy for sports. Other characteristics of the second policy establishment period included topic 7, which covers equal rights in sports; topic 11, regarding human rights improvement training for professional teams; topic 12, which concerns guaranteeing student human rights convenience facilities; and topic 13, on guaranteeing sports human rights. These topics indicate that the scope of sports human rights expanded in this period compared to the earlier two periods. Specifically, we found that human rights issues in sports that focused on violence, sexual violence, and guaranteeing student athletes the right to learn had expanded to include professional athletes as well.

The results of this study indicate a gradual increase in awareness of human rights issues within Korea’s elite sports sector. Over the first policy establishment period (approximately 4 years), 280 news reports on sports human rights issues were recorded, yielding five topics through LDA topic modeling. In the subsequent “policy transition period” (7 years), 687 news reports were documented, resulting in nine topics. Moving into the second policy establishment period (4 years), 3025 news reports and 13 topics were identified, showcasing a threefold increase in sports human rights news articles compared to the preceding decade. This suggests a heightened societal interest in sports human rights and a conducive environment for enhancing these rights. Moreover, the evolution of sports human rights topics from the first to the second policy establishment period indicates a progression beyond initial concerns of sexual violence (assault) and student athletes’ human rights. The discourse expanded to encompass the School Sports Promotion Act, women’s human rights issues, sports equality rights, student athletes’ convenience guarantees, and professional team human rights improvements. This shift signifies a broadening awareness of human rights in sports, extending beyond the previously limited dimensions of sex and age. It is noteworthy that the sports human rights issues, including violations of the right to education, instances of violence, and sexual misconduct, previously addressed sporadically in civil society, academia, and the government were officially brought to light through a comprehensive government-wide fact-finding survey. Despite the intensified national and social interest in human rights in sports, the persistent emergence of violence and sexual violence issues raises doubts about the effectiveness of related policies and education. It underscores the need for effective sports human rights policies and a comprehensive review of various educational contents related to human rights in sports.

The Korean government’s commitment to addressing human rights issues in sports reflects a robust policy stance. However, despite these efforts, the effective implementation of government-led public policies in the realm of sports has been lacking. Specifically, the recurrence of similar content in the policies of the policy transition period and the second policy establishment period, mirroring those of the first policy establishment period, supports this conclusion.

The cause can be found in hastily created regulation policies to resolve an incident after it occurs and the absence of a universal recognition of human rights in sports. Thus, mid- to long-term plans are needed to move away from such hastily prepared regulatory policies and establish effective ones. This study identified key topics related to human rights issues in Korean sports using the LDA topic modeling analysis method. By leveraging these derived topics, this study aims to furnish foundational data for the sustainable establishment of policies aimed at addressing human rights issues in Korean sports.

Further, we need to analyze cases in other countries in which behavioral science is reflected in national public policies. This can help Korea find ways to apply behavioral science in establishing sports policies, including behavioral economics and psychology. In addition, to develop effective, sustainable policies for resolving human rights issues in sports, improvements in awareness should be supported. However, improved awareness can only be achieved when a culture is established through a sustainable, intentional effort and education.

Based on the findings of this study, we propose the following policy recommendations. Firstly, there is a need to enhance monitoring within the sports sector and refine reporting mechanisms based on comprehensive fact-finding surveys. Although the survey on violence and sexual violence among sports players initiated in 2005 unveiled approximately 78% of the incidents, the response primarily emphasized the necessity of human rights education, providing only guidelines and no actual punitive measures against the wrongdoers. This indicates that this survey on human rights in sports was more of a tool for exerting pressure than for enforcing consequences for human rights violations. Additionally, the current reporting system through the Korea Sports Council may not adequately consider the nature of sports human rights issues, often arising from closed and structural power dynamics. Strengthening the reliability of fact-finding processes, on-site monitoring, and reporting agencies is essential to effectively respond to human rights issues in sports.

Secondly, we recommend expanding the scope of the content of sports human rights education. Presently, sports human rights education predominantly centers on violence and sexual violence, overlooking various other human rights challenges prevalent in the sports domain. The separation of sports human rights and general human rights hampers the recognition of issues by both victims and perpetrators. Therefore, we advocate for including diverse topics in the educational curriculum to enhance awareness and prevent human rights problems. Rather than being solely reactive, sports human rights education should adopt a forward-looking approach, aiming to prevent issues and necessitating efforts to integrate various human rights-related subjects into sports education.

6. Conclusions

We analyzed sports human rights policies over time, providing insights into sports human rights violations, a social problem in Korean society. Our findings can enable national policy strategic intervention in order to improve human rights in the Korean sports sector. According to our results, Korea’s policies on sports human rights have gradually expanded from the first policy establishment period through the policy transition period to the second policy establishment period. During the policy transition period, discussions were held to resolve human rights issues in sports through the launch of the special committee for sports innovation, the launch of a joint investigation team between the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism and the Prosecution Service, and the launch of the Sports 3.0 Committee (a sports policy advisory body). In the second policy establishment period, the scope of sports human rights was expanded compared to the other periods. In addition, we found that the public’s interest in sports human rights issues and sports human rights education at the national level drove further implementation.

However, Korean government-led public policies have not been properly established in sports. Causes of this include hastily created regulatory policies and the absence of a universal recognition of human rights in sports. Mid- to long-term plans for effective policy establishment are needed, and measures to apply behavioral science, such as behavioral economics and psychology, should be used to establish effective sports policies. In addition, national efforts and education should be pursued to improve the awareness of human rights in sports. Although we offer useful insights, our study does have limitations. Big data analysis, such as LDA topic modeling, is limited in identifying ways to establish public policies and improve awareness of human rights in sports. Additionally, the interpretation of LDA topic modeling analysis results is subject to individual perspectives, introducing challenges in precisely comprehending the significance of words associated with various topics. Therefore, follow-up studies are required that research sustainable public policy plans and how to apply behavioral science approaches, including behavioral economics and psychology. Notably, this study did not account for the distinctions within elite athlete groups (such as student athletes, professional team athletes, and national team athletes). Therefore, future investigations should consider the diverse segments within the elite athlete population for a more comprehensive understanding. Sports human rights policies should be sustainable. The principle of sustainability should be considered when sports organizations and operating institutions adopt sports human rights policies. This will contribute to establishing sustainable human rights policies in the sports environment. In addition, research on improving the perception of sustainable sports human rights is needed. Efforts to improve public awareness of human rights in sports should raise interest in sports human rights and their sustainability, thus encouraging sports fans, athletes, and sponsors, who are sports’ subjects, to lead a positive change in sports human rights issues.

Author Contributions

Study design: N.-Y.C. and H.A.; conceptualization, N.-Y.C. and H.A.; study conduct: N.-Y.C., Y.-V.K. and H.A.; data collection: N.-Y.C. and H.A.; data analysis: N.-Y.C. and H.A.; data interpretation: N.-Y.C. and H.A.; drafting the manuscript: N.-Y.C., Y.-V.K. and H.A.; revising the manuscript’s content: N.-Y.C., Y.-V.K. and H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Sookmyung Women’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea (SMWU-2308-HR-051).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mountjoy, M.; Brackenridge, C.; Arrington, M.; Blauwet, C.; Carska-Sheppard, A.; Fasting, K.; Kirby, S.; Leahy, T.; Marks, S.; Martin, K.; et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D. Establishing New Sports Paradigm and Future Task through the Sports Reform Committee Policy Documents Analysis in South Korea. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2020, 59, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, B.H.; Love, A.; Rider, R.A. Symbolic Power and Dual Careers of Athletes: Successful Career Transition Experiences of Korean College Athletes Who Quit Sport. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2022, 39, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D. Study on the Current Status and Future Direction for Human Rights Research in Sports. J. Educ. Cult. 2022, 28, 583–597. [Google Scholar]

- National Human Rights Commission of Korea. Sports Human Rights Field Investigation; National Human Rights Commission of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020.

- Korean Sport & Olympic Committee. Sports (Sexual) Violence Survey; Korean Sport & Olympic Committee: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K. A Study on the Human Rights of Student Sports Player and the Guaranteeing of their Rights to Education. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2009, 12, 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Park, S. Human Rights Policy Analysis and Improvement Direction in Sports: Focusing on the Protection of Right for Learning. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2020, 59, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.E.; Lee, M.S.; Byun, H.J.; Kim, S. An Analysis on the Continuum of Learning Rights/Violence/Sexual Violence in the Experiences of Student- athletes from the Perspective of Sexual Politics. J. Korean Women’s Stud. 2009, 25, 35–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H. A Discussion on the Ambivalence of the Minimum Academic Achievement Policy. Korean J. Sport 2021, 19, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.W. Logical Backgrounds of Fostering the Studying-Student-athletes. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2011, 50, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H. A new perspective on student athletes’ rights and right to learning: Focusing on pedagogic discourse. J. Korean Soc. Study Phys. Educ. 2021, 26, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Sports & Human Rights in Korea: Age of Violence towards Victory. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S. Human Rights Policy Analysis and Improvement Measures in Sports: A Focus on Relief and Protection from (Sexual) Violence. Philos. Mov. 2020, 28, 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- Myung, W. The socio-cultural background and the current issues of camp training system in school sport. Korean J. Sport Sci. 2017, 28, 592–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.C.; Kim, J.H. Human Rights of Student Athletes, Past and Present. Philos. Mov. 2020, 28, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.G. Discussion and suggestions on school violence and its response in the sports field. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2021, 24, 49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Im, C.Y. Types of Subjective Perception of High School Taekwondo Student Players on Human Rights in Sport. J. Martial Arts 2020, 14, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.K.; Yu, T.H. Student Athletes in Terms of Human Rights: An Educational Dicourse. Korean Assoc. Sport Pedagog. 2007, 14, 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.R. The Analysis of News Framing on Human Rights of Student Athletes. Korean Soc. Sociol. Sport 2010, 23, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Myung, W. A Study on Knowledge Discourse of Student-athlete’s Right for Learning. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2020, 59, 221–239. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.H.; Yi, J.W. Schooling and the culture of school athletics. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2004, 43, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, G.M. The Constitutional Implication for Student Athletes of Their Rights to Learn. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2010, 13, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, K. A Comparative Law Study for the Guarantee of Sports Rights. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2019, 22, 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.T.; Kim, S.K. A study on the introduction of a special judicial police officer system to guarantee the human rights of athletes. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2020, 23, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.G.; Kim, J.; Yoon, H.J. Normative System of the Sport Human and National Responsibilities. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2020, 23, 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yim, Y.S.; Hong, D.K. An exploration for the prevention of human rights violation in elite sports. Korean Assoc. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 26, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.J. Constitutional Status of Sportright: Athlete’s real condition and solution plan about school violence and the way Law-Human Rights Education should go. J. Hum. Rights Law-Relat. Educ. 2012, 5, 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D. An Analysis of Human Rights Policy in Sports in South Korea. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2021, 24, 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Miner, G.; Elder, I.V.J.; Fast, A.; Hill, T.; Nisbet, R.; Delen, D. Practical Text Mining and Statistical Analysis for Non-Structured Text Data Applications; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Wallace, L.; Rich, S.; Zhang, Z. Tapping the Power of Text Mining. Commun. ACM 2006, 49, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R.; Sanger, J. The Text Mining Handbook: Advanced Approaches in Analyzing Unstructured Data; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jusoh, S.; Alfawareh, H.M. Techniques, Applications and Challenging Issue in Text Mining. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Issue 2012, 9, 431–436. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, S.M.; Indurkhya, N.; Zhang, T. Fundamentals of Predictive Text Mining; Springer: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, S. Understanding inverse document frequency: On theoretical arguments for IDF. J. Doc. 2004, 60, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kang, M.J.; Park, K.R.; Joe, G.M. Domestic research trends analysis on inclusive education for young children with disabilities using frequency analysis and LDA topic modeling: Based on papers from 1998 to 2022. Korean J. Early Child. Educ. Res. 2023, 25, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Lafferty, J.D. Correlated topic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2006, 18, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M. Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.L.; Steyvers, M. Finding scientific topics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101 (Suppl. S1), 5228–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, B.; Song, M.; Jho, W. A study on opinion mining of newspaper texts based on topic modeling. J. Korean Soc. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2013, 47, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyvers, M.; Griffiths, T. Probabilistic topic models. In Handbook of Latent Semantic Analysis; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.; Nag, M.; Blei, D.M. Exploiting Affinities between Topic Modeling and the Sociological Perspective on Culture. Poetics 2013, 41, 570–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenaño-Fernandez, D.; González, M.; Gil, D.; Luján-Mora, S. Text mining of open-ended questions in self-assessment of university teachers: An LDA topic modeling approach. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 35318–35330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, J.; Manning, C.D.; Heer, J. Termite: Visualization techniques for assessing textual topic models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces, Naples, Italy, 22–25 May 2012; pp. 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H. Actual Conditions of Invasion & Measures of Sport Safety Right. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2010, 13, 141–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.W.; Park, C.B. A study on the actual situation and countermeasures of verbal aggression in the school elite athletes. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2008, 47, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- You, K.U.; Won, Y.B. Research into the cause and type of violence among adolescent athletes. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2007, 46, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.B.; Oh, H.T.; Choi, D.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, T.Y. The violence in sport through the relationships of power. Korea J. Sports Sci. 2009, 19, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, S.; Mountjoy, M.; Marcus, M. Sexual Harassment and Abuse n Sport: The Role of The Team Doctor. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Human Rights Commission of Korea. Sports Human Rights Guidelines Recommendations; National Human Rights Commission of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010.

- Kim, J.D.; Kim, D. Problems and Solutions of Punishment on Sexual Violence in the World of Sport. J. Sports Entertain. Law 2019, 22, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.J. Human Right Abuse of Female Athletes and Solution for the Problem. J. Sport Entertain. Law 2014, 17, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.; Cho, K.M. A Legal Approach on the Illegal Personal Information Collection Actions of Sport Organization against Its Members. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2015, 54, 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund. Human Rights Principles; United Nations Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.H.; Jumg, E.; Yu, T.H. Current Situation and Future Tasks of Human Rights Education in South Korean Sport. J. Hum. Rights Law-Relat. Educ. 2012, 14, 109–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Sport & Olympic Committee. 2020 Business Results Report; Korean Sport & Olympic Committee: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Human Rights Commission of Korea. Research on the Development of Sports Human Rights Charters and Guidelines; National Human Rights Commission of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Huh, J.H.; Kim, E.J.; Ko, K.H. Research on the human rights violation of semi-professional athletes in the workplace. Korean J. Sport Sci. 2020, 31, 728–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).