Abstract

Given the crucial role of entrepreneurial optimism (EO) in prompting university students’ green entrepreneurial intentions (GEI), scholars are still striving to explore the causal mechanism that can facilitate the underlying relationship. Based on the social cognitive theory, we hypothesize that individual’s psychological resources, entrepreneurial resilience (ER) and entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE), mediate the association between EO and GEI. In addition, this study seeks to investigate the impact of sustainability orientation (SO) in the relationship between EO and GEI. Data for this study have been collected from Chinese university students in their final years. The authors used variance-based Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to test the proposed hypotheses. The findings indicate that EO significantly influences GEI. Further, ER and ESE significantly mediate the link between EO and GEI. Moreover, this study finds that SO significantly moderates the relationship between EO and GEI such that the association is stronger at high levels of SO and vice versa. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior studies have tested these relationships. The findings suggest that the proposed model can be utilized by practitioners and policy makers to facilitate the execution of green entrepreneurship among university students.

1. Introduction

While the prevalence of green entrepreneurship is well-recognized, understanding the phenomenon of university students’ green entrepreneurial intentions (GEI) is still a subject of ongoing debate [1,2]. This debate to a certain extent reflects the two distinct streams of views about the antecedents of GEI. On the one hand, a massive stream of research has identified contextual factors as the key stimulators of GEI, including university-based and external institutional entrepreneurial support [2]; conceptual, educational, and national support [3]; and entrepreneurial education [4,5]. On the other hand, there is a narrow strand of psychology and entrepreneurship domains that strive to explore the individual-level antecedents of GEI such as personality traits [6], entrepreneurial passion, and alertness [7]. Surprisingly, there is a dearth of empirical evidence that investigates the individual-level precursors of GEI [8]. Although it has been theorized that entrepreneurial optimism (EO) can be linked with GEI, only a limited sample of studies have investigated entrepreneurial optimism as an antecedent of GEI. An exception to this is the study of Wang et al. [9] who examined the impact of EO as a driving force for GEI. Despite the fact that EO holds an eminent role in predicting GEI, the authors envisaged that the underlying mechanism that might transform EO into successful GEI still needs to be explored. Our study addresses the call of Wang et al. [9] and seeks to explore the boundary effects of the EO–GEI relationship.

The aims of this study are threefold. First, EO is an important factor that can help university students translate their optimism regarding sustainable responsibility into environment change and changes in society at large. The construct of EO represents bipolar views in its genre [10]. The first stream classifies it as an “optimistic bias” that provokes overconfidence or overoptimism and may cause distorted perceptions of the future, culminating in unfavorable outcomes [11]. In juxtaposition to this, the other thread categorizes it as “dispositional optimism”, which generates positive expectations about the future, engendering entrepreneurs to yield higher productivity than others who lack EO [12]. These opposite views about EO present mixed findings in the academic literature and thus warrant additional inquiry to reach a consensus that might explore the causal mechanism through which EO culminates in improved entrepreneurial intentions, specifically GEI.

This turns out to be our second objective. We rely on the social cognitive theory [13] and propose that EO enhances GEI through the mediating role of an individual’s psychological resources, namely, entrepreneurial resilience (ER) and entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE). EO fuses ER and ESE, which are the chief components of psychological capital or PsyCap, fueling the impact of EO on GEI. ER reflects entrepreneurs’ ability to retrieve themselves from disruptions in functioning [14] caused by optimistic bias. Likewise, ESE represents individuals’ perceptions of their ability to successfully perform entrepreneurial roles [15] thereby stimulating dispositional optimism. Hence, individuals with superior EO may excel in transitioning their environmental concerns into enriched GEI through the mediating roles of ER and ESE. Our study is essential to empirical inquiry as it addresses the unexplored mediating roles of ER and ESE between EO and GEI.

Third, in addition to examining the causal mechanism of the EO-and-GEI link by investigating the mediating roles of ER and ESE, we also propose the moderating role of sustainability orientation (SO) that also might underpin the association. SO is a key driving force that motivates individuals to transform their optimism for environment into actionable initiatives, i.e., GEI. The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) [16] defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Thus, SO implies individuals’ concerns about social responsibility and environmental protection [17]. Therefore, we hypothesize that high levels of university students’ SO strengthen the association between EO and GEI (and vice versa).

There are several contributions of this study. First, we enrich the academic discussion on GEI and related literature. Investigating entrepreneurship, particularly green entrepreneurship, is important because it leverages university students to recognize and exploit opportunities that arise from market imperfections linked to environmental and social challenges [17]. Past research has shown that entrepreneurship provides opportunities to university students to combat the rising issues of unemployment [18], hence providing opportunities for social and economic development [19]. Second, by linking EO as the key booster of GEI, we present a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon that may enhance the likelihood of university students’ taking advantage of entrepreneurial initiatives. According to prior research [6], only 2% of Chinese university students start their own business. We suggest that fostering EO may result in escalated levels of GEI. Third, we predict that university students’ psychological resources, ER and ESE, ameliorate the relationship between EO and GEI, which to date has not been tested earlier. Last, by exploring the intervening role of SO, we advance the limited research on the relationship between EO and GEI and present a comprehensive framework that is capable of inspiring GEI at the disposal of EO.

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. Relationship between EO and GEI

An optimist is “someone who looks at the bright side of things and expects positive and desirable events happening in the future” [20]. Optimism engenders self-confidence and elevates individual’s entrepreneurial intentions [9]. Given that commencing a new enterprise is a complex process and that around half of newly established businesses fail [21], entrepreneurship scholars contemplate that such positive emotions and energy are imperative for entrepreneurial activity [22]. Positive emotional states infused by EO allow nascent entrepreneurs to cultivate successful entrepreneurial endeavors [23]. According to Janssen et al. [24], optimistic students have strong entrepreneurial intentions and are more inclined to pursue an entrepreneurial career. Baluku et al. [25] found that optimistic students are confident in their abilities to successfully translate their entrepreneurial ideas into reality. Similarly, Hmieleski and Baron [26] corroborated that nascent entrepreneurs with dispositional optimism are more capable to deal with challenges and obstacles in pursuing new enterprises. In a similar fashion, Wang et al. [9] advocated that students possessing a high tendency towards ecology are more motivated to engage in behaviors that can contribute to environmentalism, thereby leveraging GEI. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1.

There will be a positive relationship between EO and GEI.

2.2. Relationship between EO, ER, and ESE

In addition, we suggest that EO affects individuals’ psychological resources, namely, ER and ESE. According to Newman et al. [27], ER and ESE are two of the four components of PsyCap with hope and optimism as the other underlying dimensions. Prior studies have shown idiosyncratic acumens about the application of PsyCap in the work context [28] with a narrow stream of research capturing the dimensions of PsyCap in the entrepreneurship domain. For instance, Tang [29] argued that research studies examining an individual’s traits, i.e., psychological resources, are important for entrepreneurial initiatives. Nonetheless, scholarly work has scarcely exploited its implications in the entrepreneurship context [30]. Further, a review of scholarly work suggests that researchers’ deployment of PsyCap is different in diverse contexts. For example, Wang et al. [9] investigated the correlational impact of optimism and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial motivation and intentions. Likewise, Kapikiran and Acun-Kapikiran [31] examined the mediator effect of self-efficacy between optimism and resilience. Relying on the purpose of the study, we propose that both of forms PsyCap, i.e., ER and ESE, mediate the link between EO and GEI. Hmieleski and Baron [26] acknowledged “no significant difference in the degree of optimism that entrepreneurs exhibited toward the success of their businesses, regardless of their individual level of preparedness to lead their firms” (p. 60). We suggest that ER and ESE are important cognitive resources that facilitate individual’s preparedness of green entrepreneurial activities through stimulating their tolerance and confidence levels, which are the key ingredients for success in entrepreneurial initiatives. This makes our research more salient and unique.

EO reflects an individual’s perception of “looking on the bright side of entrepreneurial initiatives” [10]. Particularly, optimistic individuals view situations as good and bad events [20]. They expect that bad events are temporary and good events are enduring, which encourages them to undertake entrepreneurial initiatives [30]. Further, the perception and experience of good events enhance individual’s confidence in themselves [13], thereby facilitating the transition of their goals into actions. Nevertheless, adverse experiences may incapacitate their ability to withstand difficulties and challenges in pursuing entrepreneurial goals [10]. Therefore, insights from resilience literature may buffer the negativities prompted due to optimistic bias, ultimately aiding a smooth transition. There is a lack of research on the link between EO with ER in the entrepreneurship literature. However, borrowing insinuations from medical science indicates that optimistic patients were more capable of adapting to stressors as well as less likely to develop medical illnesses [32]. This supports our theoretical deduction that EO can be linked with ER. In addition, a review of previous literature indicates that resilience is linked with a positive self-image, enhanced self-confidence, and envisioning realistic plans [33]. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2a.

There will be a positive relationship between EO and ER.

Similarly, we also link EO with ESE. According to Welter and Scrimpshire [30], optimism is subjective and triggers ESE. ESE refers to “the conviction (confidence) someone has to mobilize the necessary motivation, cognitive resources, and activities to perform an identified task [green entrepreneurship]” [34]. According to the social cognitive theory [13], ESE elicits individual’s confidence in themselves that they can provoke success and are capable of “getting the job done” [26]. Further, Bandura [13] posits that “an optimistic sense of self-efficacy is required to achieve goals”, indicating the effect of EO and ESE. Similarly, Baluku et al. [35] linked the reportage of optimism with entrepreneurial self-efficacy. In addition, several well-recognized studies have linked optimism with self-efficacy [36,37,38,39,40] among studies in the different contexts. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2b.

There will be a positive relationship between EO and ESE.

2.3. Mediating Role of ER and ESE between EO and GEI

Integrating the impact of EO on GEI in Hypothesis 1 with the impact of EO on ER and ESE in Hypotheses 2a and b, we propose the mediating effects of ER and ESE between EO and GEI. The social cognitive theory [13] supports these mediation relationships. EO is an individual psychological trait that elevates their confidence and intentions to commence an eco-friendly business. For instance, Janssen et al. [24] and Wang et al. [9] noted that individuals high in optimism are more likely to embark on the process of new venture creation. However, researchers also report that explanations based merely on EO will be trivial to fuel GEI unless entrepreneurs are prepared to demonstrate consistency and persistence as well as tolerance to reap enduring effects and combat adversities and failures [26]. Hence, ER and ESE serve as stimulators that facilitate the smooth culmination of EO into GEI. Conclusively, we hypothesize that optimistic individuals advance their environmental concerns forward through manifesting enhanced capabilities and responsiveness by embarking upon resilience and self-efficacy. They tend to come up with unique and novel ideas to promote environmentalism as well as develop more confidence and tolerance in dealing with uncertain challenges and obstacles in pursuing green entrepreneurial initiatives. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3a.

The relationship between EO and GEI will be mediated by ER.

Hypothesis 3b.

The relationship between EO and GEI will be mediated by ESE.

2.4. Moderating Role of SO

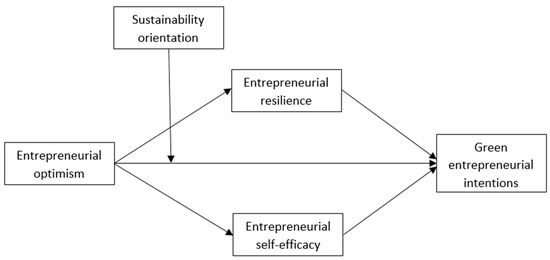

Considering the significant role of EO in stimulating university students’ GEI through the mediating effects of ER and ESE, we suggest that the relationship will also be influenced by individual’s SO (Figure 1). SO refers to “entrepreneurs’ tendency to match their economic objective with preserving the environment and the society” [41]. Given the nature of green entrepreneurship embarking upon more environmental-specific behaviors rather than traditional entrepreneurship that aims to enlarge economic benefits [42], SO may explain why individuals wish to commence a sustainable enterprise [43]. It is argued that individuals’ value choices are determined by the perspectives on their connection with the environment and society [44]. SO infuses critical standards and guidelines that individuals adopt to manage such relationships. Individuals high in SO are more likely to develop a strong sense of social responsibility, particularly responsibility concerning green areas [9]. Further, scholars argue that individuals’ environmental concerns foster their preferences to engage in GEI, if not the entire process of “green entrepreneurship” [9]. Moreover, prior research on SO suggests that individuals with superior SO have a higher tendency to engage in volunteer activities and programs that aim to mitigate environmental issues [42]. Di Fabio et al. [45] noted that individuals’ environmental awareness and active involvement in eco-friendly practices foster positive emotional states and raise confidence in their abilities to influence the environment with their actions. In addition, scholars have related SO with entrepreneurs’ triple-bottom line objectives: “economic”, “social”, and “environmental” [46]. Therefore, individuals possessing high levels of SO will have heightened motivation in pursuing and integrating environmental concerns with business activities, thereby underpinning the link between EO and GEI. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4.

The relationship between EO and GEI will be influenced by SO such that high (low) levels of SO will strengthen (weaken) the relationship.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of green entrepreneurial intentions.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Population and Sampling Technique

This study conducted a quantitative survey to collect data from Chinese university students. This is in accord with the objective of the study to assess the GEI of university students. The target population of the study is expected to be an appropriate representation of the context. This is because entrepreneurial intentions are the basis of entrepreneurial behaviors. Extensive empirical studies have employed university students to comprehend the phenomenon of entrepreneurial intentions [1,6,18]. The students were in their final years in the Business degree programs. In addition, it is important to utilize a sample of students from the Business degree programs because they are taught several subjects related to business, business ethics, entrepreneurship, and sustainability among others. Therefore, it is interesting to know the mechanism that might explain university students’ GEI. According to [2,18,22], entrepreneurial behaviors can be predicted based on entrepreneurial intentions. That is to say, the stronger the intentions, the higher the likelihood of commencing green entrepreneurship. Moreover, appropriate institutional and governmental interventions can be executed to transform students’ GEI into green entrepreneurial behaviors [2]. Hence, in order to facilitate green entrepreneurial behaviors, it is important to determine the antecedents that shape university students’ GEI.

Using the purposive sampling technique, the authors collected data from university students. The purposive sampling technique is recommended when the study seeks to achieve its purpose and is utilized in several preliminary studies that capture similar contexts [47,48]. The authors approached 500 university students to collect responses for the study variables from February 2022 to May 2022. They were provided a cover letter along with the questionnaire. The questionnaire contained two sections. In the first section, the participants were requested to provide their demographic details such as gender, age, and degree programs. The second section was related to the study variables and the items were adapted from previous studies (briefed in the subsequent section). The participants were asked to provide responses for EO, ER, ESE, GEI, and SO. The rationale of the study was briefed in the cover letter, and participants were ensured of the confidentiality of their responses. Further, they were informed that their responses would only be used for analysis purposes and that the findings of the study would be provided to them if they would seek it. A total of 417 completely filled questionnaires were received, indicating a response rate of 83%. The obtained responses were analyzed using the variance-based SEM. According to Ringle et al. [49], the study examined the outer and the inner models for analysis. Our survey included responses from 297 male students and 120 female students with an average age of 27 years (standard deviation: 4.26). A total of 23% of the students were enrolled in the bachelor’s degree programs, 42% were enrolled in Master’s degree programs, and 35% were enrolled in doctoral degree programs. Further, in order to minimize the issues of common method biasness (CMB), we employed the multicollinearity assessment test and all the values being below 5 indicated that the study is free from the issues of CMB (Table 1). The subsequent section presents an overview of the measurement scales and results of the study.

Table 1.

Multicollinearity Assessment.

3.2. Measurement Scales

The questionnaire items to measure the study variables are based on previously established scales and are measured on 5-point Likert scale with 1 indicating “complete disagreement” and 5 indicating “complete agreement”. The EO scale is based on items developed by Zhang et al. [50] and contains 3 items. A sample item is: “Most of the time, I am high-spirited”. The ER scale is derived from Sinclaire and Wallstone [51] and contains 4 items. A sample item is: “I believe that I can grow in positive ways by dealing with difficult situations”. The ESE scale contains 3 items and is adapted from Hockerts [52]. A sample item is: “I can find a way to help solve environmental problems”. The scale items to measure GEI is derived from Linan and Chen [53] and modified by Zhang [54]. The scale contains 5 items, and a sample item is: “I am preparing for green entrepreneurship in the future”. The SO scale is based on items developed by Kukertz and Wagner [44] and contains 6 items. A sample item is: “I think that environmental problems are one of the biggest challenges for our society”.

4. Results

4.1. Outer Model Assessment

Before analyzing the inner model to yield the structural paths and examine the predictive capability of the proposed model, we assessed the outer model for validating reliability and validity of the measurement scales. This is in line with the recommendation of Hair et al. [55]. Table 2 presents the psychometric properties of the study variables. Reliability analysis was tested using the composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha criteria. Our results indicate that all the proposed variables have good internal consistency as the values fall between the range of 0.7 and 0.95. Further, outer loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) tests were employed to determine the convergent validity. Given that the minimum threshold value was 0.50, results indicate convergent validity of the constructs as all the values are greater than the acceptable threshold.

Table 2.

Psychometric Properties of Constructs.

Additionally, Fornell–Larcker and heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) tests were utilized to examine the discriminant validity of the constructs. Results of these analyses are reported in Table 3 and Table 4. For obtaining the Fornell–Larcker values, the square root of AVE values was assessed, indicating that all the items of a particular scale had a strong correlation with their own constructs that inter-construct correlation. Similarly, use of the HTMT ratio is also recommended by Henseler et al. [56] to validate the discriminant validity coupled with Fornell–Larcker criterion. The authors processed a bootstrapping technique that was bias-corrected and accelerated (5000 resamples). Results indicate that all the HTMT values are lower than the maximum limit of HTMT0.90. Hence, these analyses confirm the discriminant validity of the questionnaire survey.

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

Table 4.

Heterotrait–monotrait Ratio.

4.2. Inner Model Assessment

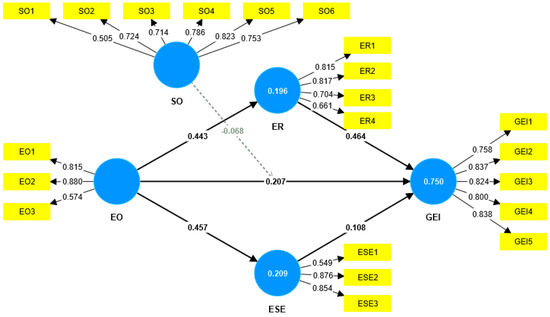

As discussed above, the authors used variance-based SEM to analyze the measurement (i.e., “outer model”) and the structural models (i.e., “inner model”). After examining the measurement model, the authors established reliability and validity of the measurement scales. Resultantly, this qualifies the data to examine the inner model. For the inner model assessment, in the first step, path coefficients (β) were obtained along with their relevant t- and p-values. The bootstrapping procedure was used to obtain the t- and p-values, and the confidence intervals (CIs) were used to verify the analysis. The structural equation modeling (SEM) is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Model of Green Entrepreneurial Intentions.

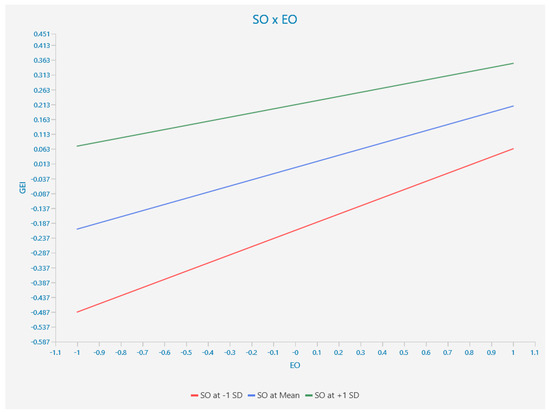

Results presented in Table 5 indicate that EO is significantly and positively related to GEI (β = 0.207, t = 3.552, p < 0.05) with 95% of CIs between 0.0.083 and 0.0.309. Thus, hypothesis H1 is accepted. Likewise, EO is significantly and positively related to ER (β = 0.443, t = 7.824, p < 0.05) with 95% of CIs between 0.331 and 0.548 and ESE (β = 0.457, t = 9.151, p < 0.05) with 95% of CIs between 0.357 and 0.555. Thus, hypotheses H2a and 2b are accepted. Results of the indirect effects reported in Table 5 suggest that ER, (β = 0.205, t = 6.786, p < 0.05) with 95% of CIs between 0.147and 0.266 and ESE, (β = 0.051, t = 3.165, p < 0.05) with 95% of CIs between 0.021 and 0.083, significantly mediate the relationship between EO and GEI. As both the direct and indirect effects are significant, this indicates complementary mediating effects of ER and ESE between EO and GEI. Thus, hypotheses H3a and 3b are accepted. The study also proposed the moderating role of SO between the relationship of EO and GEI. The two-stage moderation approach was used [55], and analysis revealed that the interaction effect of SO and EO is significant (β = −0.068, t = 2.749, p < 0.05) with 95% of CIs between −0.115 and −0.019. Moreover, the interaction effect was assessed using the simple slope analysis. Figure 3 illustrates the interaction effect and indicates that high levels of SO (plus one SD) profoundly influence the positive relationship between EO while low levels of SO (minus one SD) has less profound impact on the association.

Table 5.

Tests of Direct and Indirect Effects.

Figure 3.

Moderator Effect of Sustainability Orientation on Green Entrepreneurial Intentions.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Given the escalated gravity of interest in examining factors that can stimulate university students’ GEI, scholars have identified a wide array of individual as well as context variables. However, the link between individuals’ psychological resources and GEI has rarely been investigated [30]. This study attempts to address this omission in the broader literature of green entrepreneurship and proposes the influence of EO on GEI through the mediating role of students’ psychological resources, namely, ER and ESE. The authors also propose the moderating effect of SO in the relationship between EO and GEI. Data were collected from university students in China and empirically assessed using the variance-based SEM. On the basis of the study’s findings, we draw the following conclusions that present meaningful implications for theory and practice.

First, EO is an essential ingredient of navigating university students’ GEI (H1). Prior research endorses the inference that optimistic individuals are more likely to commence their own business as compared to those with low or no optimism [35] despite the fact that a majority of research has shown implications of EO on entrepreneurial initiatives and/or entrepreneurial success [57]. Scholars argue that prior research on the link between EO and entrepreneurial success has revealed fragmented findings [10,58]. For instance, Helweg-Larsen and Shepperd [59] identified optimistic bias on the basis of overconfidence or overoptimism, which can lead to distorted perceptions of the future and may boost the probability of failure. Further, the relationship between failure and confidence has been negatively reported in the extant literature, barricading its positive implications for entrepreneurial success. On the contrary, dispositional optimism has been displayed as imposing a positive influence on entrepreneurial success [60].

Second, by investigating students’ psychological resources ER and ESE, our study advances existing knowledge on EO and speculates that ER and ESE may have stimulating impacts on the influence of optimism on GEI. Accordingly, this study finds that there is a significant impact of EO on ER and ESE (H2a and 2b). Our findings indicate that ER and ESE boost individuals’ tolerance and self-confidence, which are the sine qua non rudiments of entrepreneurial initiatives, and hence facilitate the successful culmination of EO into GEI. By integrating these hypotheses, the results indicate that both ER and ESE significantly mediate the direct link between EO and GEI (H3a and 3b). By assessing the mediating role of ER and ESE, our study presents novel contributions to the existing literature on the link between PsyCap and GEI. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that investigates the mediating role of ER and ESE between EO and GEI. In addition, plentiful research has shown promising implications of individual’s resilience and self-efficacy on a wide array of individuals’ attitudes and behaviors in diverse contexts [61,62,63,64]. Hence, our study is aligned with and extends preliminary investigations of the subject matter.

Third, given the critical role of EO in developing university students’ GEI, we hypothesized that an individual’s SO would be a vital factor that intervenes this relationship and boosts the impact of EO on GEI (H4). Our findings reveal that individuals high in SO have a stronger association between EO and GEI than those low in SO. Past research has illustrated that SO not only elicits students’ ecological inclinations but also undertakes entrepreneurs’ triple bottom-line objectives such as economic, social, and environmental [46]. Hence, university students pursuing entrepreneurial careers possess more robust and sound reasoning to engage in eco-friendly behaviors that may promote their eco-entrepreneurial initiatives thereby strengthening the link between EO and GEI. However, no prior studies have linked these associations, thus granting novelty and uniqueness to our study.

These findings also suggest some useful implications for practice. First, our findings indicate that emphasis should be put on cultivating university students’ EO so that their GEI may be fostered and transformed into execution. The role of students coupled with institutional efforts and governmental interventions can facilitate this phenomenon as today’s students may turn out to be tomorrow’s potential entrepreneurs. Therefore, they should realize the importance of optimism in leveraging green entrepreneurial initiatives. Throughout their candidature, they should primarily work on improving self-confidence and reliance in their abilities so that they become more resilient and develop superior beliefs that they can contribute significantly to the environment. Research has shown that specific goals and tiny tasks are key inputs of enhancing confidence in oneself [65]. Students should partake in activities that they deem feasible to be challenging as well as rewarding. For instance, short-term planning and goal-setting may help them to accomplish these tasks. Further, they should start by making micro-investments in green assets, which will elevate their confidence levels and enable them to invest more in green entrepreneurial initiatives. Besides, given the crucial role of SO in underpinning the underlying relationship, students should actively participate in social and charitable activities, particularly those imposing positive impacts on ecology, e.g., growing trees, manifesting green consumption behaviors, and promoting institutional and national sustainable development goals (SDGs). Second, considering the significance of these variables, universities should encourage students to opt for self-employment as an alternative to pursuing employment careers. Research supports that Business Incubation Centers (BIC) play an imperative role in developing students’ entrepreneurial traits and facilitate their raw ideas into execution by providing mentoring and coaching to students [66]. Furthermore, universities should encourage students to participate in volunteer activities that prompt societal and environmental concerns. Students participating in such activities should be rewarded so that their passion for pursuing green entrepreneurial careers may be ameliorated. Prior research has demonstrated that external rewards provoke extrinsic motivation, which complements intrinsic motivation [67]. Last but not least, research suggests that setting up an enterprise is not an easy task, and normally there is a gap of several years between a student’s graduation and commencement of a business. In due course, their motivation and concern for the environment may fluctuate, which may affect the impact of SO on the link between EO and GEI. For this reason, governmental interventions should aid nascent entrepreneurs in commencing a green enterprise. Examples include but are not limited to interventions such as financial support, exempted or relaxed tax conditions, and the minimization of entry-level barriers.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

The findings of this study should be carefully interpreted, considering the limitations of the study. First, our study examined the crucial role of EO in promoting university students’ GEI through ER and ESE with the moderating effect of SO. There is a wide agreement that supports the view that intentions are cultivated into behaviors [2]. However, investigating the proposed model on a sample of university students may be deemed problematic. Nevertheless, the choice of university students as a sample in this study is justified in line with previous studies because today’s students may be tomorrow’s potential entrepreneurs. We suggest that future studies should extend our model by testing its impact on green entrepreneurial behaviors. Second, the relationship between EO and GEI may also be affected by some other factors such as entrepreneurial passion [7], family support [68], prior business experience [69], etc. It would be interesting to examine these factors that might influence the association between EO and GEI. Third, longitudinal studies may be undertaken in this context to assess students’ SO and GEI before and after graduating from their institutions because the role of a university education and mentoring may have significant impacts in shaping students’ GEI. Finally, caution should be given to interpret findings based on a sample of Chinese university students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., A.M.R., H.B., I.A., S.K. and J.D.; methodology, Y.Z., A.M.R., H.B., I.A., S.K. and J.D.; software, Y.Z., A.M.R., H.B., I.A., S.K. and J.D.; formal analysis, Y.Z., A.M.R., H.B., I.A., S.K. and J.D.; data curation, Y.Z. and J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z., A.M.R., H.B., I.A., S.K. and J.D.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., A.M.R., H.B., I.A., S.K. and J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study adheres to the ethical guidelines of the local legislation and/or institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

The informed consent of the respondents was implied through survey completion.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions reported in this study are included in the article. Further, the data may be requested from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fanea-Ivanovici, M.; Baber, H. Sustainability at Universities as a Determinant of Entrepreneurship for Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G. From green entrepreneurial intentions to green entrepreneurial behaviors: The role of university entrepreneurial support and external institutional support. Int. Ent. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Risco, A.; Mlodzianowska, S.; García-Ibarra, V.; Rosen, M.A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. Factors affecting green entrepreneurship intentions in business university students in COVID-19 pandemic times: Case of Ecuador. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, N. Green entrepreneurial intention of Mba students: A malaysian study. Int. J. Ind. Manag. 2020, 5, 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Nuringsih, K.; Puspitowati, I. Determinants of eco entrepreneurial intention among students: Study in the entrepreneurial education practices. Adv. Sci. Letter 2017, 23, 7281–7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, W.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A.; Qureshi, M.A. Impact of personality traits and university green entrepreneurial support on students’ green entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of environmental values. J. App. Res. High Edu. 2020, 13, 1154–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Murad, M.; Shahzad, F.; Khan, M.A.S.; Ashraf, S.F.; Dogbe, C.S.K. Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: Role of entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and proactive personality. Front. Psy. 2020, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.M.; Rizwan, S.; Zayed, N.M.; Nitsenko, V.; Miroshnyk, O.; Kryshtal, H.; Ostapenko, R. The Impact of Green Entrepreneurship on Social Change and Factors Influencing AMO Theory. System 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cao, Q.; Zhuo, C.; Mou, Y.; Pu, Z.; Zhou, Y. COVID-19 to green entrepreneurial intention: Role of green entrepreneurial self-efficacy, optimism, ecological values, social responsibility, and green entrepreneurial motivation. Front. Psy. 2021, 12, 732904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, N.; Ivanov, V.; Cole, R.A. Entrepreneurial optimism, credit availability, and cost of financing: Evidence from US small businesses. J. Corp. Fin. 2017, 44, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J. Person Soc. Psy. 1980, 39, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J. Person Soc. Psy. 1994, 67, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Personal and Collective Efficacy in Human Adaptation and Change; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Taylor, M.S.; Seo, M.G. Resources for change: The relationships of organizational inducements and psychological resilience to employees’ attitudes and behaviors toward organizational change. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 727–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.E.; Peterson, M.; Mueller, S.L.; Sequeira, J.M. Entrepreneurial self–efficacy: Refining the measure. Ent. Theor. Practic. 2009, 33, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED, S.W.S. World commission on environment and development. Our Comm. Futur. 1987, 17, 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, S.; Reynaud, E. Individuals’ sustainability orientation and entrepreneurial intentions: The mediating role of perceived attributes of the green market. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 25–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, T.; Lin, C.L.; Xu, D. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention of university students in China: Integrating the perceived university support and theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, G.; Kha, K.L.; Arokiasamy, A.R.A. Factors affecting students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A systematic review (2005–2022) for future directions in theory and practice. Manag. Rev. Quar. 2022, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Klimas, P.; Czakon, W.; Kraus, S.; Kailer, N.; Maalaoui, A. Entrepreneurial failure: A synthesis and conceptual framework of its effects. Europ. Manag. Rev. 2021, 18, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaralli, N.; Rivenburgh, N.K. Entrepreneurial intention: Antecedents to entrepreneurial behavior in the USA and Turkey. J. Glob. Ent. Res. 2016, 6, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, A.; Lindblom, T.; Wechtler, H. Dispositional optimism, entrepreneurial success and exit intentions: The mediating effects of life satisfaction. J. Bus Res. 2020, 120, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.; Giacomin, O.; Shinnar, R. Students’s Entrepreneurial Optimism, Overconfidence and Entrepreneurial Intentions. In Proceedings of the ECSB Entrepreneurship Education Conference, Aarhus, Denmark, 29–31 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baluku, M.M.; Kikooma, J.F.; Kibanja, G.M. Psychological capital and the startup capital–entrepreneurial success relationship. J. Smal Bus Ent. 2016, 28, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Baron, R.A. Entrepreneurs’ optimism and new venture performance: A social cognitive perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Ucbasaran, D.; Zhu, F.E.I.; Hirst, G. Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. J. Org. Behav. 2014, 35, S120–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef-Morgan, C.M.; Luthans, F. Psychological capital and well-being. Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Inv. Stres. 2015, 31, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.J. Psychological capital and entrepreneurship sustainability. Front. Psy. 2020, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, C.; Scrimpshire, A. The missing capital: The case for psychological capital in entrepreneurship research. J. Bus Ventur. Insight 2021, 16, e00267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapikiran, S.; Acun-Kapikiran, N. Optimism and Psychological Resilience in Relation to Depressive Symptoms in University Students: Examining the Mediating Role of Self-Esteem. Educ. Sci. Theor. Practic. 2016, 16, 2087–2110. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia, F.; Moore, J.L.; Linnville, S.E.; Hoyt, R.E.; Hain, R.E. Optimism predicts resilience in repatriated prisoners of war: A 37-year longitudinal study. J. Traum. Stres. 2012, 25, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedner, T.; Abouzeedan, A.; Klofsten, M. Entrepreneurial resilience. Annal Inn. Ent. 2011, 2, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull 1998, 124, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluku, M.M.; Matagi, L.; Musanje, K.; Kikooma, J.F.; Otto, K. Entrepreneurial socialization and psychological capital: Cross-cultural and multigroup analyses of impact of mentoring, optimism, and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions. Ent. Edu. Pedag. 2019, 2, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, S.; Mergler, A.; Boman, P. Managing the transition: The role of optimism and self-efficacy for first-year Australian university students. J. Psy. Couns. Sch. 2014, 24, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademas, E.C. Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: The mediating role of optimism. Person Ind. Differ. 2006, 40, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.M. Optimism and realism: A review of self-efficacy from a cross-cultural perspective. Int. J. Psy. 2004, 39, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xie, B.; Guo, Y. The trickle-down of work engagement from leader to follower: The roles of optimism and self-efficacy. J. Bus Res. 2018, 84, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand, K.L. Hope, Self-Efficacy, and Optimism: Conceptual and Empirical Differences; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Calic, G.; Mosakowski, E. Kicking off social entrepreneurship: How a sustainability orientation influences crowdfunding success. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 738–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Mubushar, M.; Khan, I.U.; Rehman, H.M.; Khan, S.U. The influence of personality traits on sustainability-oriented entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of servant leadership. Env. Devel Sustain. 2021, 23, 13707–13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnaeim, S.M.; El-Bassiouny, N. The relationship between entrepreneurial cognitions and sustainability orientation: The case of an emerging market. J. Ent. Emerg. Eco. 2021, 13, 1033–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Palazzeschi, L.; Bucci, O.; Guazzini, A.; Burgassi, C.; Pesce, E. Personality traits and positive resources of workers for sustainable development: Is emotional intelligence a mediator for optimism and hope? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.K.; Belz, F.M. Sustainable entrepreneurship: What it is. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, Z.; Arasti, Z.; Bagheri, A. Identifying social entrepreneurship competencies of managers in social entrepreneurship organizations in healthcare sector. J. Glob. Ent. Res. 2018, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayati, D.T.; Fazlurrahman, H.; Hadi, H.K.; Arifah, I.D.C. The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention through planned behavioural control, subjective norm, and entrepreneurial attitude. J. Glob. Ent. Res. 2021, 11, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. “SmartPLS 4.” Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH. 2022. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Dong, Y. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with mental health. Stu. Psychol. Behav. 2010, 8, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, V.G.; Wallston, K.A. The development and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale. Assessment 2014, 11, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K. Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 41, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y.W. Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Ent. Theor. Practic. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. A Study on the Relationship between Green Entrepreneurial Traits, Green Entrepreneurial Motivation and Green Entrepreneurial Intention. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publicaitons: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Danso, A.; Uddin, M.; Damoah, J.O. Entrepreneurs’ optimism, cognitive style and persistence. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 1355–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevelyan, R. Optimism, overconfidence and entrepreneurial activity. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 986–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helweg-Larsen, M.; Shepperd, J.A. Do moderators of the optimistic bias affect personal or target risk estimates? A review of the literature. Person Soc. Psy. Rev. 2001, 5, 74–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Dispositional optimism. Trend Cog. Sci. 2014, 18, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etherton, K.; Steele-Johnson, D.; Salvano, K.; Kovacs, N. Resilience effects on student performance and well-being: The role of self-efficacy, self-set goals, and anxiety. J. Gen. Psy. 2022, 149, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallak, R.; Assaker, G.; O’Connor, P.; Lee, C. Firm performance in the upscale restaurant sector: The effects of resilience, creative self-efficacy, innovation and industry experience. J. Retail Con. Servic. 2018, 40, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M. Impact of role conflict, self-efficacy, and resilience on nursing task performance of emergency department nurses. Korean J. Occ. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Warner, L.M. Perceived self-efficacy and its relationship to resilience. Resilience in children, adolescents, and adults. Transl. Res. Into Pract. 2013, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltz, D.L.; Öncü, E.R.M.A.N. Self-confidence and self-efficacy. In Routledge Companion to Sport and Exercise Psychology; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Fernández, M.T.; Blanco Jiménez, F.J.; Cuadrado Roura, J.R. Business incubation: Innovative services in an entrepreneurship ecosystem. Servic. Ind. J. 2015, 35, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, S.; Polania-Reyes, S. Economic incentives and social preferences: Substitutes or complements? J. Econ. Lit. 2012, 50, 368–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, A.E.; Settles, A.; Shen, T. Does family support matter? The influence of support factors on entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions of college students. Acad. Ent. J. 2017, 23, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Staniewski, M.W. The contribution of business experience and knowledge to successful entrepreneurship. J. Bus Res. 2016, 69, 5147–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).