Abstract

The Climate Village Program (CVP) is one of the national flagship programs of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia to support emission reduction and climate resilience. This paper examines the challenges and strategies for implementing the climate village program in the national and sub-national contexts. Data and information derived from discussions, seminars, focus group discussions, and interviews with local government officials in East Kalimantan were used to analyze the social learning of the CVP plus, including those on the policy process and its concept, integration program, and implementation. Sustainable strategies need to be addressed by integrating the CVP plus into the medium-term development plan of the region. The challenges and way forward of the CVP plus could be an excellent lesson for implementation in all provinces of Indonesia to support FOLU (Forest Other Land Use) Net Sinker 2030 and LTS-LCCR (Long-Term Strategy on Low Carbon and Climate Resilience) 2050. Key challenges and strategies for the CVP plus are highlighted in the planning and implementation phases, especially in improving climate resilience. This study also points out the steps of implementation of the CVP, development partners and their roles in relation to climate change and other socio-economic facts that make it difficult to engage real stakeholders in the implementation of the CVP plus.

1. Introduction

As an archipelagic country, Indonesia is very vulnerable to climate change. The Long-Term Strategy on Low Carbon and Climate Resilience (LTS-LCCR) 2050 has been developed to support integrated national transparency on climate change adaptation and mitigation actions. LTS-LCCR 205 covers 83,820 villages, of which 3270 villages have registered for the Climate Village Program (CVP) by 2021. The number of these CVPs is expected to increase gradually to 20,000 by 2024 [1].

The CVP is one of the community-based national flagship programs of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) of the Republic of Indonesia, which has been running since 2016. It aims to mainstream the global issue of climate change to collectively respond to climate change impacts occurring at the local site level. MoEF has created a roadmap as a common reference for implementing the climate village program. The CVP is followed and implemented by sub-national parties to support emission reduction and climate resilience. Like other ambitious national policies, the CVP is dynamically implemented by provincial governments during the implementation process towards emission reduction and climate resilience, based on the variations of problems, potentials, and supports they have. In 2021, the guidelines and direction for the implementation of the CVP were issued by the MoEF Directorate of Climate Change [2]. An important note on the CPV is that information on forest land availability and carbon potential in villages was less important. However, as a joint adaptation and mitigation action, this program makes a significant contribution to GHG mitigation efforts in Indonesia before and after 2020 [3].

East Kalimantan is one of 34 provinces in the country threatened by deforestation and forest degradation. It is estimated that between 2003 and 2013, 230,720 ha of forest area was lost, and about 305 million tons of CO2 will be released from protected areas if deforestation continues [4]. Important lessons have been learned in this province, including improving programs to combat deforestation and forest degradation. The result is an increase in the CVP, which is designed to maintain and/or improve forest cover.

The CVP plus was launched with multilateral support from the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility-Carbon Fund (FCPF-CF). East Kalimantan has an area of 12.7 million ha, of which 6.5 million ha (54%) is forested and has been selected as a site for pilot project FCPF-CF since 2015 [5].

The CVP plus is to operate in cultivation and protection areas, which are spread over five districts and one city. The CVP plus also plays a role in three sectors, namely forestry, plantation, management, and community empowerment. Efforts must be made to increase community resilience to address the impact of climate change [6,7]. The social learning process becomes an important component in the CVP plus to promote the active participation of the community and stakeholders in the implementation of local actions. This will strengthen resilience to the impacts of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [8]. Social learning defines a shift from ‘‘multiple cognition” to ‘‘collective cognition” as the condition of quite different perceptions, the potential for change, shared perspectives, insights, and values [9]. Social learning is understood as the process through which groups of people learn to define common problems, find, search for, and implement alternative options or solutions, and assess the value of solutions for specific problems [10,11].

As stated in [12], the social learning process is an approach to community development and education. It aims primarily to aid participation and experience in capacity building. This program of the CVP is superior to others because it is easy to implement, locally relevant, culturally appropriate, and efficient in its use of natural resources. There is an opportunity to receive incentives, although budgets are already available at the provincial, district, and village levels from the Indonesian central government.

This paper aims to assess the challenges and strategies in climate program implementation at the national and sub-national levels to support emission reduction and climate resilience, based on the experience of the CVP plus in East Kalimantan. The major gap is how to implement the CVP plus in line with local development plans and other climate change programs with stakeholders, as envisioned in the regional medium-term development plan. Another gap is how to implement the CVP plus at the local level in accordance with the characteristics of each village to reduce climate-related disaster risks at the local level, accommodate local wisdom as a strategy to stimulate communities to make efforts to increase their resilience to climate change, and protect tropical rainforest through community empowerment and participation programs that are more collaborative and well-targeted.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework

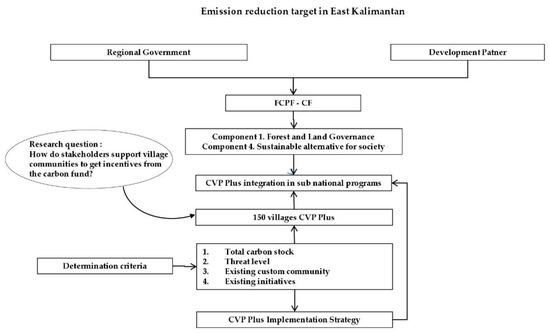

This research is a case study focused on the efforts of various parties in East Kalimantan Province to support villages with forest cover and carbon stock to gain result-based payment (RBP) from deforestation and forest degradation prevention efforts. East Kalimantan Province was selected as the research site for a number of reasons. First, local communities in East Kalimantan have the ability to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Second, the government and development partners appreciate and support the actions of local communities in mitigating climate change. Third, East Kalimantan is the site of the first pilot project for the jurisdiction-based reduction of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) in Indonesia. The REDD+ pilot project is in the FCPF-CF scheme. The logical framework of this research is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research logical framework.

2.2. Study Location

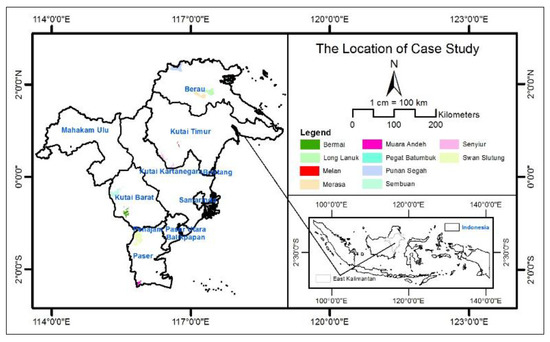

This study was conducted in the province of East Kalimantan. A total of 10 CVP plus villages were purposely selected, representing various districts, forest types, remaining forest, the presence of indigenous peoples/customary forests, the existence of forest Adat/Custom communities in the CVP plus villages [13,14], existing FPIC approval in accordance with FPIC guidelines [13,15,16,17,18], and the existence of mitigation and adaptation efforts to climate change for the sustainability of people’s livelihoods. The selected villages are Angsa Slutung Village and Muara Andeh Village in Paser Regency, Bermai Village and Sembuan Village in West Kutai Regency, Senyiur Village and Melan Village in East Kutai Regency, as well as Felt Village, Long Lanuk Village, Punan Segah Village, and Village Pegat Batumbuk in Berau Regency. The map of study locations is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Map of study locations. Source: author’s compilation.

2.3. Data Collection

A preliminary study was conducted from December 2018 to March 2019 to review CVP policies at the national level and CVP plus policies at the sub-national level and conduct interviews with key informants from local government and development partners. A follow-up study on the implementation of the CVP plus in the field was carried out from August 2020 to December 2021.

Research data were obtained in the form of primary and secondary data from key informant interviews, focus group discussions (FGD), field observation, and desk studies. Primary data in the form of quantitative and qualitative data include forest cover area and potential carbon stock, forest resource utilization activities, and the presence of indigenous/customary communities. Secondary data collected include administrative data and data on the socio-economic conditions of rural communities, as well as documents on adaptation and mitigation of climate change in East Kalimantan.

Carbon stock was measured using area activity data and carbon stock of the forest cover [5]. The activity data were taken from the map of land cover in the form of forest in 2019. The forest carbon stock values of primary dryland forest (281.3 tC/ha), secondary dryland forest (147.3 tC/ha), primary mangrove forest (160.8 tC/ha), secondary mangrove forest (126.8 tC/ha), primary swamp forest (344.24 tC/ha), and secondary swamp forest (233.5 tC/ha). According to the [19], the sources of carbon stock consist of five carbon pools: above-ground biomass, below-ground biomass, dead wood, litter, and soil organic matter. The formula for estimating the carbon stock at landscape level (CSlandscape) for each forest cover (Ai) and carbon stock per hectare (CSi) as follows CSlandscape = Ai x CSi.

2.4. Key Respondents

The key respondents were divided into three major groups. The first group was the group of the provincial government and local organizations of East Kalimantan Province, consisting of the Forestry Service of East Kalimantan Province, the Environment Service of East Kalimantan Province, the Community and Village Empowerment Service of East Kalimantan Province, the Plantation Service of East Kalimantan Province, the Energy and Mineral Resources Service of East Kalimantan Province, and the Regional Disaster Mitigation Agency of East Kalimantan Province. The second group was the group of development partners, consisting of the Provincial Climate Change Council (DDPI) of East Kalimantan, Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara (YKAN), GIZ Forclime FC, WWF Indonesia, Planet Urgence, GGGI, BUMI Foundation, Yayasan Biosfer Manusia (BIOMA Foundation), PADI Foundation, Yayasan Konservasi Khatulistiwa (YASIWA) Indonesia, ULIN Foundation, and Mulawarman Environment Forum (FliM). Meanwhile, the third group consisted of community groups in the 10 CVP villages, namely the Village Government, the Village Council (BPD), the Community Empowerment Agency (LPM), the Village Adat/Custom Institution, the Village Forest Management Agency (LPHD), the Adat/Custom Forest Management Agency (LPHA), and Karang Taruna.

2.5. Analysis Methods

An analysis was conducted using descriptive, qualitative, and quantitative methods by exposing the processes involved, from planning (determining the parties involved, determination of sites, budgeting, and creation of the FPIC team according to needs and the FPIC guide), to implementation (socialization and FPIC approval), and reporting (the CVP plus villages who declared their participation in the FCPF-CF program through the FPIC phases and were also actively involved in reporting the emission reduction activities on the MMR portal of East Kalimantan).

3. Results

3.1. The CVP plus and Support from Various Parties

3.1.1. The Climate Village plus Policy and Program

The CVP is one of the national programs that demonstrate the Indonesian Government’s commitment to the climate change mitigation efforts under the Paris Agreement. Indonesia adopted this agreement in 2014 at COP-12 as outlined in the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) document as part of the low-casualty development and climate change adaptation activities. As President Joko Widodo stated at the opening event of the Climate Adaptation Summit 2021, the Indonesian Government has set a goal to establish 20,000 climate villages by 2024. As of 2021, 3270 locations across Indonesia have been registered as CVP sites. This program is implemented in low administrative regions such as rukun warga (citizen association) or dusun (hamlet) and high administrative regions such as kelurahan or desa (village) or in an area whose community has made efforts to sustainably adapt to and mitigate climate change [20].

The CVP applies community-based development according to these three principles: community-based, local resource-based, and sustainable. The CVP plus or the Low-Emission CVP is one of the programs initiated by the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), which aims to integrate the CVP with the Carbon Fund (CF) scheme, particularly in villages with remaining forests. The FCPF implementation is a follow-up to land-based REDD+ payment preparation in Indonesia that takes the form of a result-based payment. This program rewards people in certain locations who have implemented climate change adaptation and mitigation efforts in a sustainable manner [20,21,22]. REDD+ is instrumental in engaging local communities and Adat/Custom community in the low emission program [23].

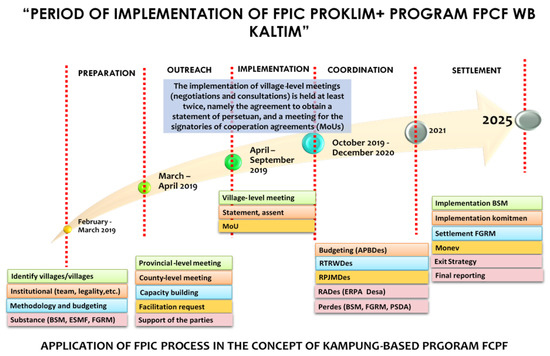

The villages targeted by the CVP plus under the FCPF program differ slightly from the villages targeted by the CVP implemented by the MoEF. The CPV plus takes into account criteria for carbon stock, the level of threat from forest destruction, the existence of Adat/Custom communities [24], existing CVP-related initiatives, and the urgency for these villages to become climate villages. Following the ERPD document, the East Kalimantan Provincial Government has identified approximately 150 CVP plus villages with remaining forest based on four criteria: carbon stock, levels of threat, the existence of Adat/Custom local communities, and existing support [1,14]. The CVP plus implementation process is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Steps of FPIC CVP plus implementation in East Kalimantan.

3.1.2. The Climate Change Mitigation Activities Conducted by the Local Government and the Development Partners in East Kalimantan

Environmental regulations are critical to encouraging better environmental practices [25]. The effectiveness of climate change policy implementation is not only measured by the right content of the policy but also affected by the role of stakeholders who implement the policy [26]. The stakeholders, including the regional heads, development partners, and private companies, also have critical roles in supporting climate change issues [19,20,21], including those located in East Kalimantan. They have taken a central role in the CVP’s success. The term CVP plus is used as an alternative way of naming the program to accommodate the climate change adaptation and mitigation activities previously undertaken by various parties in East Kalimantan. The role of each stakeholder in climate change mitigation and adaptation in East Kalimantan is explained in Table 1.

Table 1.

The role of local governments, development partners, and business entities in relation to climate change in East Kalimantan.

3.1.3. Commitments of East Kalimantan Provincial Government as Sub-National Entity to Implement the CVP plus as Part of Climate Change Controlling Program

As one of the provinces with vast forest cover, the East Kalimantan Provincial Government has since 2008 been committed to reducing the rates of deforestation and forest degradation as well as to lowering the CO2 emission rate by becoming part of the 10 provinces that initiated the establishment of the Governor’s Climate and Forest Task Force. This commitment was followed by a declaration of “Kaltim Green” at the 1st East Kalimantan Summit and the readiness for REDD implementation in 2020, which aimed to improve the overall quality of life of the community, minimize ecological disasters, reduce pollution and degradation of water and air quality, and raise community awareness.

In 2011, the provincial government of East Kalimantan implemented this commitment by establishing the council on Climate Change of East Kalimantan (DDPI-Kaltim), which was tasked with formulating province-level strategies to reduce emissions and climate change mitigation. In the same year, the East Kalimantan Provincial Government made strategic documents such as the Low Carbon Growth Strategy (LCGS, document available), Regional Action Plan on Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction (RAD-GRK) [27], the East Kalimantan Provincial Action Plan and Strategy (SRAP) on REDD+ Implementation [28], the Climate Change Master Plan [29], and the Green Economy Master Plan [30].

On the basis of this commitment, in 2015, the Minister of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) selected East Kalimantan Province as the location for the pilot project of Reduction of Emission from Deforestation and Forest Degradation under the result-based payment scheme through the World Bank-managed Forest Carbon Partnership Facilities-Carbon Fund (FCPF-CF) program. Under the FCPF-CF program, East Kalimantan Province will receive an incentive for every reduction in greenhouse gas emission in the land-based sector for the period 2020–2024. The East Kalimantan Provincial Government is set to integrate the FCPF-CF program into the Kaltim Green framework, affirming emission reduction for a longer period of time up to 2035 [30]. The CVP plus program is included within component 1 (Forest and Land Governance) and component 4 (Sustainable Alternative for Society) of the ERPD, and by the East Kalimantan Provincial Government, this program is to be incorporated in the Regional Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMD) of East Kalimantan in 2019–2023 [31]. The planning of the CVP plus program through integration into the RPJMD of East Kalimantan is proof of the strong commitment of the East Kalimantan Provincial Government in efforts to control climate change. In the process, the integration planning requires the participation of all parties from the provincial level to the village government and village communities/customary communities. This participatory process is certainly not an easy thing because each party, especially the village/customary community, has different social, economic, and ecological characteristics. In addition, the main challenge is how to ensure that the RPJMD can actually be operationally translated to the village community/customary community level.

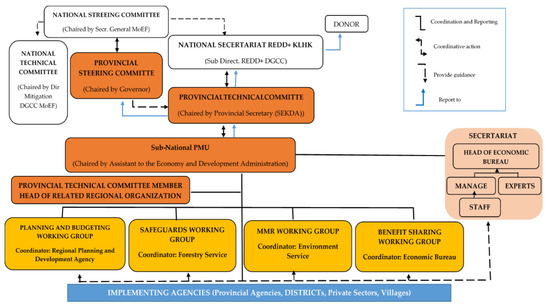

The implementation of the CVP plus in the FCPF Project requires intensive coordination and communication between the Provincial Government of East Kalimantan, the Regency Government to the village government/customary community level. This is a challenge that needs to be handled properly in the hierarchical management of activities from the top level to the bottom level. In FCPF-CF implementation, a management unit has been founded at the sub-national level to manage the FCPF-CF program under the Governor as the director, Regional Secretary as the technical commission chief, the Economy and Development Assistant in the Program Management Unit (PMU), the Economic Bureau as the secretariat coordinator, and four Work Groups in the Program Management Unit (PMU), namely the Measurement, Monitoring, and Reporting (MMR) Work Unit that is coordinated by the Environment Service of East Kalimantan Province (Dinas Lingkungan Hidup/DLH Prov Katim), the Safeguard Work Unit that is coordinated by the Forestry Service of East Kalimantan Province (Dinas Kehutanan/Dishut Prov Kaltim), the Planning and Budgeting Work Unit that is coordinated by the Regional Planning and Development Agency (Bappeda) of East Kalimantan and Regional Financial and Asset Management Agency of East Kalimantan, and the Benefit Sharing Mechanism (BSM) Work Unit that is coordinated by the Economic Bureau of the East Kalimantan Provincial Government, in reference to the national institution of FCPF-CF management [32].

Figure 4 above shows that in addition to the Governor, the Provincial Secretary who chaired the FCPF-CF activities at the sub-national level also reports the results of activities to the National Secretariat of REDD and the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. The Governor also coordinates with the National Steering Committee led by the Secretary-General of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, which plays a role in preparing directions to the national technical committee and the National REDD+ Secretariat of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, who then reports to donors. To support the responsibilities of the Governor, the sub-national institution of the FCPF management unit (Sub-National PMU), chaired by the Economics and Development Administration Assistant, provides facilitation of management and technical aspects.

Figure 4.

FCPF management unit structure at sub-national (East Kalimantan Province).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Implementation of the CVP plus in East Kalimantan Province

To date, the implementation of the CVP plus in East Kalimantan Province has achieved the FPIC implementation at the village level and received approval from 99 villages. The COVID-19 pandemic has hindered FPIC implementation in two regencies, namely Kutai Kertanegara Regency and Mahakam Ulu Regency. However, as a whole, the CVP plus implementation has proceeded as planned and will soon enter the phase where the village communities’ emission reduction activities will be reported to the MMR portal of East Kalimantan, which is integrated with the Climate Change Control National Registration System operated by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia.

The description in the results section proves that village communities in the 150 CVP plus villages in East Kalimantan Province are generally able to adapt to and mitigate climate change at the local level. This supports the rationale that village communities that are able to conserve forest cover will potentially gain incentives from FCPF-CF through the CVP plus program. This is also proof of the recognition that the Adat/Custom communities are the landowners [33,34]. Therefore, as a token of appreciation, the village communities in the 150 CVP plus villages receive the largest proportion of incentives from performance (65%) and rewards (10%) if the villages succeed in preventing deforestation and land degradation within a 10 year period from 2006 to 2016 [1,35].

4.2. Lessons Learnt from the CVP plus Implementation in East Kalimantan

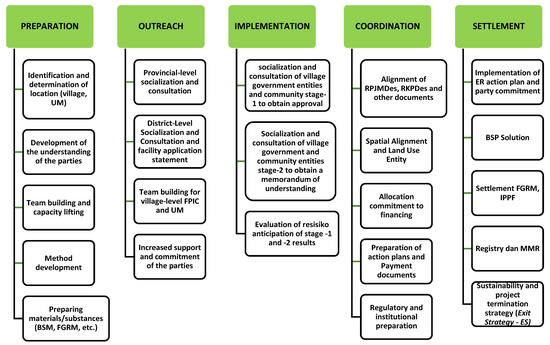

4.2.1. Preparation of 150 Villages Determination

In conducting the CVP plus, the FPIC team performed socialization at the province, regency, and village levels according to the FPIC guide [13,15,16,18,31,32]. At the province level, the socialization covered the introduction to the program as well as the scope, stages, and follow-up plan of the program. At the regency level, the socialization was intended to ensure role distribution, willingness, and ways of reaching the villages. Meanwhile, at the village level, the socialization was undertaken in two steps: (1) ensuring that the community members understood the program, demonstrated no objection, and expressed their agreement, and (2) ensuring that the community members understood their rights and obligations and ensuring their commitment (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Stages of the CVP plus Implementation in East Kalimantan.

The 150 CVP plus villages were spread across 8 cities/regencies, had variations in livelihoods, and had Adat/Custom and newcomer communities (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of 150 CVP plus villages by regency, livelihood, the existence of Adat/Custom communities, and the existence of newcomers.

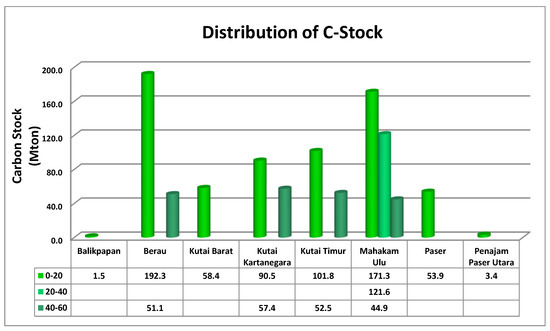

The forests present in the 150 CVP plus villages were highland natural forests, lowland natural forests, peat swamp forests, and mangrove forests with various areas of forest cover and carbon stocks, with the lowest in Balikpapan city and the highest in Berau Regency and Mahakam Ulu Regency (see Table 3). The villages selected for the CVP plus program are villages with good forest cover. Good forest cover in the CVP plus has a high carbon stock, which contributes significantly to preventing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. Therefore, good forest cover and high carbon stocks are very important for the CVP plus program.

Table 3.

Forest cover and carbon stock potential in the CVP plus villages per city/regency.

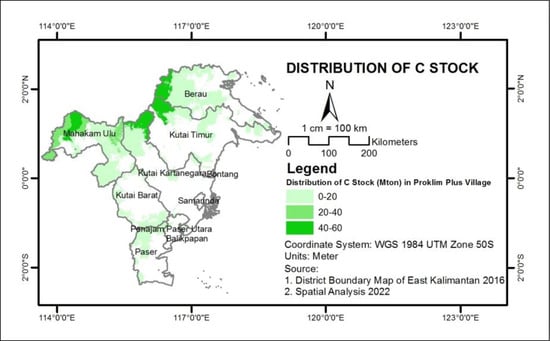

Forest carbon stock of the 0–20 Mt class was distributed across 8 regencies, accounting for 673.2 Mt. In class 20–40 Mt, there was Mahakam Ulu Regency with a total of 121.6 Mt, and in class 40–60 Mt, there were 4 regencies, namely Kutai Kertanegara Regency, Kutai Timur Regency, Berau Regency, and Mahakam Ulu Regency, with a total of 205.9 Mt. See Figure 6 and Figure 7 for more detail.

Figure 6.

Carbon stock distribution across 150 CVP plus villages in 8 regencies/cities.

Figure 7.

C-stock distribution in East Kalimantan Province. Source: author’s compilation.

The existence of Adat/Custom communities constitutes one of the prominent criteria in determining the 150 villages to be targeted for the CVP plus. This is in line with some reports [14,17,37,38] that state that Adat/Custom communities’ participation in the REDD+ activity is critical as it is related to the declaration of human rights. The existence of Adat/Custom communities in East Kalimantan Province is regulated by Governor Regulation No. 1 of 2015 on the Guide to the Acknowledgment and Protection of Adat/Custom Communities in East Kalimantan Province [39]. The East Kalimantan Provincial Government will acknowledge the existence of an Adat/Custom community if the following 5 requirements are met: there is a history of migration; there is an Adat/Custom area; there is an Adat/Custom institution; there is an Adat/Custom law, and there is an Adat/Custom object and site evidence of Adat/Custom community heritage.

Of the eight regencies/cities in which the FCPF-CP program was conducted, only three regencies had acknowledged the Adat/Custom communities, as evidenced by the existence of a Regional Regulation [39]. The three regencies/cities are Kutai Barat [33], Mahakam Ulu [34], and Paser [40]. Therefore, the determination of the 150 CVP plus villages was based on the representativeness of the native tribes and newcomers in East Kalimantan Province. Therefore, the determination of 150 CVP plus villages in East Kalimantan Province needs to take into account the representation of indigenous peoples and migrants.

4.2.2. Lessons Learnt from the 10 CVP plus Villages in East Kalimantan

The determination of the 10 CVP plus villages was based on the forest type, Adat/Custom community existence, ability to mitigate and adapt to climate change sustainably, and community livelihoods. The administrative and socio-economic condition data of the 10 CVP plus villages can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

The administrative and socio-economic conditions of the 10 CVP plus villages.

The 10 CVP plus villages had a land cover area in the form of forests of 1113.18–49,134.87 ha and a carbon stock potential of 0.16–8.02 Mt (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Forest cover condition and carbon stock potential of the 10 CVP plus villages.

In general, the villagers’ livelihoods were strongly related to the natural resources potential existing around the forest, such as timber and non-timber forest products such as rattan, honey, medicinal herbs, waterfall, game, and fish. Additionally, according to the results of a study in the villages along the Ratah River of East Kalimantan Province [41] their livelihoods were also influenced by existing companies, such as those running the palm oil plantations, timber, and coal mining fields. The social, economic, and cultural conditions of the 150 CVP plus villages can be seen in Table 6.

Table 6.

Social, economic, and cultural conditions as well as natural resource potential.

In essence, natural resources management and utilization by communities are customs and local wisdom that are passed down from generation to generation. Therefore, they are performed sustainably according to the prevailing Adat/Custom rules, either written or unwritten. Sustainable forest resource management and utilization receive support from a variety of parties through managing institutions, as can be seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Natural resources management and utilization.

Community activities are also related to the programs offered by the village through the village institution or Adat/Custom institution. Work programs may come from partners, in this case, the Central Government/Ministry of Environment and Forestry such as the Center for Social Forestry and Environment Partnership of Kalimantan Area, Dipterocarps Research and Development Center, East Kalimantan Provincial Government such as Forestry Service of East Kalimantan Province and Forest Management Unit, and development partners such as (Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara/YKAN, Deutsche Gesellschaft fűr Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Forclime, GIZ Propeat, World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Indonesia, etc.). Some of the activities performed are actually purely initiated by the communities; for instance, the proposed activities by the Adat/Custom communities in Sembuan Village, Swan Selutung Village, and Muara Andeh Village under much facilitation from Aliansi Masyarakat Adat/Custom Nusantara (AMAN) of East Kalimantan and Yayasan Padi Indonesia.

There are also forest protection and management activities, such as one funded by TFCA Kalimantan in the Mesangat Suwi Wetland Ecosystem Estate (KEE LBMS) of Senyiur Village and Melan Village of Kutai Timur Regency under the facilitation of the YASIWA-ULIN Foundation Consortium. The Village Forest scheme is a program by the Directorate General of Social Forestry and Environment Partnership of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in the Social Forestry Division that is implemented by Sembuan Village, Bermai Village, Long Lanuk Village, Punan Segah Village, and Pegat Batumbuk Village to give access for the communities to the forest and improve their economic conditions through Social Forestry Enterprise Group (KUPS) under the facilitation of the Kawal Borneo Community Foundation (KBCF)-Komunitas Konservasi Indonesia and Warung Informasi Konservasi (KKI-WARSI) of Jambi-Deutsche Gesellschaft fűr Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Forclime consortium, which later became part of the work of the Forest Management Unit.

4.3. The Challenges in the CVP plus Implementation

The challenge faced by the East Kalimantan Provincial Government in the CVP plus implementation at the village level is the low capacity of village human resources. The Local Government and Development Partners play a critical role in supporting village communities to integrate the CVP plus into the Village Medium-Term Development Plan (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Desa/RPJMDes), the Village Budget (Anggaran Pendapatan dan Belanja Desa/APBDes), and the Village Spatial Plan (Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Desa/RTRWDes [42]. This integration process of the CVP to the Village Medium-Term Development Plan should ensure harmony between human well-being and ecology. In addition, the village communities are also in need of assistance in making a report of the emission reduction activity they have conducted on the MMR portal. The Community and Village Empowerment Service of East Kalimantan Province is a regional apparatus organization in East Kalimantan responsible for village-level assistance. In order to integrate the emission reduction program into the village development plan, the Community and Village Empowerment Service of East Kalimantan Province has proposed a green assistance program. Human Resource capacity improvement is also carried out by the development partners who have a work program in the same village.

4.4. The Strategies in the CVP plus Implementation

The success of the CVP plus implementation in East Kalimantan Province is the result of the collaboration and active role of all stakeholders, whether they be the central government, local government, development partners/non-governmental organizations, private parties, or communities. Multi-stakeholder partnerships have the potential to overcome the limitations in program implementation in relation to climate change [43]. Multi-stakeholder partnerships are a form of governance that can harness the strengths of different parties and actors. The climate change program is characterized by undesirable complexity and the need for policy coordination vertically, horizontally, and across sectors, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), industry associations, and different levels of government (national and sub-national) [44,45]. The success of a program is highly reliant on the participation of all parties across multiple levels [46,47]. A social learning process in East Kalimantan for the implementation of the CVP is affected by the involvement of all actors/stakeholders and is very important to develop the existing social networks at the village level. This was the case in Central Java Province, in which 17 actors from the government, private sector, community and community groups, non-governmental organizations, mass media, and public legal entities were involved [48]. The collaborative governance involving companies, the government, and the community constitutes a key to the success of the climate change program in Talanbubuk Village in Palembang, South Sumatera Province [49]. Community empowerment and multiple stakeholders’ involvement seem to characterize this joint adaptation-mitigation program. In addition, the joint adaptation-mitigation program in the CVP plus allows for better measurement and verification as well as monitoring and evaluation under the forest cover criteria around the village area. Regular program monitoring and evaluation is necessary to ensure all activities are on the right track.

Approval from the village communities as to the CVP plus implementation through FPIC activity will be required. The same process also took place in the REDD+ activity in Africa [50] and Vietnam [38]. The CVP plus must be part of the village development plan that is set out in the Village Medium-Term Development Plan and the Village Budget. Furthermore, it must also be incorporated into the Village Spatial Plan and reinforced by a Village Regulation. The CVP plus should also integrate the Village Medium-Term Development Plan into the emission reduction program that contributes to the non-carbon benefits related to better forest management and livelihoods, especially the improvement of local communities’ access to forest resources for improved livelihoods. The program integration into the sub-national development planning and its synergy among stakeholders are needed to ensure optimal results [51].

The CVP plus implementation in East Kalimantan Province not only supports the CVP implementation but also supports the Social Forestry (SF) program of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. SF is a program that provides the local communities with access to manage forest resources to improve their welfare as well as to resolve conflicts under five schemes: Village Forest, Community Forest, People’s Crop Forest, Forestry Partnership, and Adat/Custom Forest. The CVP plus support in the SF program is included in Component 4 of the FCPF-CF, that is, a sustainable alternative for the community.

4.5. The Key Findings in Assessing the Challenges and Strategies of the CVP plus

The key findings in assessing the challenges and strategies of the CVP plus in East Kalimantan can be seen in Table 8.

Table 8.

The key findings in assessing the challenges and strategies of the CVP plus in East Kalimantan.

5. Conclusions

The integration of the CVP into the sub-national development plan and its implementation in the village community will be sustainable if the social learning process among all stakeholders in East Kalimantan is excellent. According to the information gathered from all stakeholders in East Kalimantan, the challenges for the CVP implementation in the future are institutional aspect, integration aspect in the development plan, human resource capacity aspect, and funding aspect.

The main feature of the CVP is the presence of forest lands, which are still in very good condition, with a total area of 5,049,541 ha and a total carbon stock of 1.001 gigatons. Mahakam Ulu Regency is very dominant, with a forest area of 1,495,791 ha and a carbon stock of 33.76% compared to the other regencies. The 10 CVP plus villages had a forest area of 1113–49,135 ha and a carbon stock potential of 0.16–8.02 Mt.

As for the institutional aspect, the CVP working group operates only at the provincial level, and there is neither a district-level working group nor an official institution charged with supporting the CVP after its establishment. Regarding the aspect of integration into the development plan, the CVP activity has not been included in the Village Medium-Term Development Plan because the meeting of all stakeholders has not yet been completed. Currently, the CVP is a priority program for the East Kalimantan Provincial Government. In the meanwhile, there is a lack of capacity and people’s awareness to implement the CVP at the village level. In addition, the government’s budget for the CVP implementation is limited and needs cooperation and additional funding from all stakeholders (domestic and international).

To address the above challenges, the following strategies should be considered for future CVP implementation. Institutional strengthening is necessary to support and implement the CVP program, mainly at the village level (desa and kelurahan). As part of the program planning, the integration of the CVP into the medium-term village development plan should consider environmental sustainability and economic aspects to ensure harmony between human well-being and ecology. The biophysical conditions of the village area, the characteristics of the village area, and the use of available space in the village should be identified to ensure healthy availability of water, food, and clothing, renewable energy sources, and the environment. Regarding the capacity of human resources, the activities of training, lessons learned, field visits, and workshops can be used to improve the capacity of human resources in terms of technical information, action steps, and work procedures, especially at the village level (desa and kelurahan). In addition, collaboration between NGOs and other parties involved in climate change, communities, local government, and central government is needed, and funding opportunities from the private sector or international donors should be pursued. Collective actions and strong support from all stakeholders are very important to expand existing social networks at the village level and increase community resilience to address climate change impacts. Regular monitoring and evaluation of the programs are very important for a long-term strategy. All stakeholders should take all steps of the monitoring and evaluation process to ensure that the CVP is on the right track.

Author Contributions

C.B.W. and E.M.A. performed the original draft. I.W.S.D. and C.K. conducted supervision. N.S., S.E. and T.W. performed the methodology of the manuscript. R.M. and Y.H. conducted review and editing. Y.N. and W.I.S. coordinated, integrated, and consolidated all resources. N.N. and A.A. performed validation of data and information. K.K. and A.N.L. performed visualization data and information. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research of our manuscript was privately funded, and received no external funding. All data and information were delivered according to the private research of each author. There is no conflict in our manuscript. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data set used/and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the kind support from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Republic of Indonesia; East Kalimantan Government; Development Partners; Regional Council of Climate Change of East Kalimantan Province; Forest Carbon Partnership Facility-Carbon Fund Program; Village Government and Community in 10 Selected Villages and anonymous reviewers for substantial and grammatical comments and corrections. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of CR within the CzeCOS program, grant number LM2018123.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- GoI. Indonesia Long Term Strategy for Low Carbon and Climate Resilience 2050; Goverment of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021; p. 132.

- KLHK. Peraturan Direktur Jenderal Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim Nomor P.4/PPI/API/PPI.0/3/2021 tentang Pedoman Penyelenggaraan Program Kampung Iklim; Ministry of Environment and Foretry of the Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021.

- GoI. First Nationally Determined Contribution Republic of Indonesia; Goverment of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016; p. 19.

- Harris, N.L.; Petrova, S.; Stolle, F.; Brown, S. Identifying optimal areas for REDD intervention: East Kalimantan, Indonesia as a case study. Environ. Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 035006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoI. Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) Carbon Fund Emission Reductions Program Document (ER-PD) ER Program Name and Country: East Kalimantan Jurisdictional Emission Reductions Program; Government of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019.

- Shammin, M.R.; Haque, A.K.E.; Faisal, I.M. A framework for climate resilient community-based adaptation. In Climate Change and Community Resilience: Insights from South Asia; Haque, A.K.E., Mukhopadhyay, P., Nepal, M., Shammin, M.R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Takeuchi, K.; Folke, C. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nature Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.I.; Sam, A.S.; Sathyan, A.R. Resilience to climate stresses in South India: Conservation responses and exploitative reactions. In Climate Change and Community Resilience; Haque, A.K.E., Mukhopadhyay, P., Nepal, M., Shammin, M.R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Devaux, A.; Horton, D.; Velasco, C.; Thiele, G.; López, G.; Bernet, T.; Reinoso, I.; Ordinola, M. Collective action for market chain innovation in the Andes. Food Policy 2009, 34, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koelen, M.; Das, E. Social learning: A construction of reality. In Wheelbarrows Full of Frogs: Social Learning in Rural Resource Management; Leeuwis, C., Pyburn, R., Eds.; Koninklijke Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Chable, V.; Nuijten, E.; Costanzo, A.; Goldringer, I.; Bocci, R.; Oehen, B.; Rey, F.; Fasoula, D.; Feher, J.; Keskitalo, M.; et al. Embedding cultivated diversity in society for agro-ecological transition. Sustainability 2020, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buck, L.E.; Wollenberg, E.; Edmunds, D. Social learning in the collaborative management of community forest: Lesson from the field. In Social Learning in Community Forest; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor Barat, Indonesia, 2001; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- FSC. Implementing Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC): A Forest Stewardship Council Discussion Paper FSC-DIS-003 V1 EN; Forest Stewardship Council: Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, F. Indigenous peoples’ right to free, prior and informed consent and the world bank’s extractive industries review. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 2004, 4, 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P. Free, Prior, and Informed Consent in REDD+; The Center for People and Forests: Bangkok, Thailand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Colchester, M.; Chao, S.; Anderson, P.; Jonas, H. Free, Prior and Informed Consent: Guide for RSPO Members; Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015; 122p. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, P.A.; Marbyanto, E. Village Socio-Economic Baseline in Berau District: Survey Report of Villages in the Surrounding FMU of West Berau (Laporan Survei di Desa-desa Sekitar KPH Berau Barat: Rona Awal Sosial Ekonomi Masyarakat Desa di Kabupaten Berau); Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, FORCLIME Forests and Climate Change Programme: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maharjan, S.K.; Carling, J.; Sherpa, L.N. Training Manual on Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) in REDD+ for Indigenous People; Asia Indigenous People Pact (AIPP)—International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA): Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2012; 119p. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Prepared by the National Greenhouse Gas Inventories Programme; Eggleston, S., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T., Tanabe, K., Eds.; IGES: Kanagawa, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Emilda, A.; Tray, C.S.; Sugiatmo; Aminah; Haska, H. Buku Praktis Proklim; Direktorat Adaptasi Perubahan Iklim Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017; 103p. [Google Scholar]

- Sahuburua, Z.; Sapteno SH, M.J.; Huwae, E.A.; Rachmawaty, E.; Arundati, S.T.; Sihaloho, A.; Ie, S.; Ellen, T.V.; Padang, D.; Tehuajo, N.; et al. Road Map—Mitigasi dan Adaptasi Perubahan Iklim dan Pembangunan Berkelanjutan Provinsi Maluku; Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017; 88p. [Google Scholar]

- Albar, I.; Emilda, A.; Tray, C.S.; Sugiatmo; Aminah; Haska, H. Road Map Program Kampung Iklim (Proklim); Gerakan Nasional Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim Berbasis Masyarakat; Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017; 47p. [Google Scholar]

- Neupane, P.R.; Wiati, C.B.; Angi, E.M.; Köhl, M.; Butarbutar, T.; Gauli, A. How REDD+ and FLEGT-VPA processes are contributing towards SFM in Indonesia—The specialists’ viewpoint. Int. For. Rev. 2019, 21, 460–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttaqin, M.Z. Pengelolaan lahan dan hutan di Indonesia: Akses masyarakat lokal ke sumberdaya hutan dan pengaruhnya pada pembayaran jasa lingkungan. In Pengelolaan Kawasan Hutan dan Lahan dan Pengaruhnya bagi Pelaksanaan REDD+ di Indonesia: Tenure, Stakeholder dan Livelihoods; Muttaqin, M.Z., Subarudi, Eds.; Pusat Penelitian dan Pengembangan Perubahan Iklim dan Kebijakan, Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kehutanan—Kementerian Kehutanan: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2013; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins, C.; Fraas, J.W. Coming clean: The impact of environmental performance and visibility on corporate climate change disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekawati, S.; Subarudi; Budiningsih, K.; Sari, G.K.; Muttaqin, M.Z. Policies affecting the implementation of REDD+ in Indonesia (cases in Papua, Riau and Central Kalimantan). For. Policy Econ. 2019, 108, 101939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bappeda. RAD GRK Kaltim 2010-20130: Revisi Rencana Aksi Daerah Penurunan Emisi Gas Rumah Kaca Provinsi Kalimantan Timur; Badan Perencanaan dan Pembangunan Daerah Provinsi Kalimantan Timur: Samarinda, Indonesia, 2018; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Pemprov. Strategi dan Rencana Aksi Provinsi (SRAP) Implementasi REDD+ Kaltim; Pemerintah Provinsi Kalimantan Timur-Satuan Tugas REDD+ Unit Kerja Presiden Bidang Pengawasan dan Pengendalian Pembangunan (UKP4): Samarinda, Indonesia, 2012; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, F.; Fadli, M.; Rustam; Rahminah; Catur, D. Master Plan Perubahan Iklim Kalimantan Timur (Master Plan of Climate Change on East Kalimantan); Dewan Daerah Perubahan Iklim Kalimantan Timur: Samarinda, Indonesia, 2018; 138p. [Google Scholar]

- Bappeda. Masterplan Pembangunan Ekonomi Hijau Kalimantan Timur 2015–2030; Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Daerah Provinsi Kalimantan Timur: Samarinda, Indonesia, 2015; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Pemprov. Peraturan Daerah Provinsi Kalimantan Timur Nomor 2 Tahun 2019 tentang Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah Daerah Provinsi Kalimantan Timur Tahun 2019–2023; Pemerintah Provinsi Kalimantan Timur: Samarinda, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- KLHK. Keputusan Menteri Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan Nomor: SK 287/MENLHK/SET.2/7/2020 tentang Tim Tingkat Nasional Pengelolaan Program Penurunan Emisi Gas Rumah Kaca Dalam Kerangka Forest Carbon Patnership Facility di Prov Kalimantan Timur; Ministry of Environmental and Forestry of The Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020.

- Kubar. Peraturan Daerah Kabupaten Kutai Barat Nomor: 13 Tahun 2017 tentang Penyelenggaran Pengakuan dan Perlindungan Masyarakat Hukum Adat. Sendawar, Kabupaten Kutai Barat, Indonesia. 2017. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/97689/perda-kab-kutai-barat-no-13-tahun-2017 (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Mahulu. Peraturan Daerah Kabupaten Mahakam Ulu Nomor: 7 Tahun 2018 tentang Pengakuan, Perlindungan, Pemberdayaan, Masyarakat Hukum Adat dan Lembaga Adat. Ujoh Bilang, Kabupaten Mahakam Ulu, Indonesia. 2018. Available online: https://www.aman.or.id/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Perda-adat-mahulu.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Pemprov. Peraturan Gubernur Kalimantan Timur Nomor: 33 Tahun 2021 tentang Mekanisme Pembagian Manfaat dalm Program Penurunan Emisi Gas Rumah Kaca Berbasis Lahan. Samarinda, Provinsi Kalimantan Timur, Indonesia. 2021. Available online: https://jdih.kaltimprov.go.id/produk_hukum/detail/2230c51d-5316 (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- BAPLAN. WebGIS Ministry of Enviroment and Forestry. 2020. Available online: https://geoportal.menlhk.go.id/webgis/index.php/en/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- UNEP. REDD+ Implementation: A Manual for National Legal Practioners; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.T.; Castella, J.C.; Lestrelin, G.; Mertz, O.; Le, D.N.; Moeliono, M.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Vu, H.T.; Nguyen, T.D. Adapting free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) to local contexts in REDD+: Lessons from three experiments in Vietnam. Forests 2015, 6, 2405–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pemprov. Peraturan Daerah Provinsi Kalimantan Timur Nomor: 1 Tahun 2015 tentang Pedoman Pengakuan dan Perlindungan Masyarakat Hukum Adat di Provinsi Kalimantan Timur. Indonesia. 2015. Available online: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/20818 (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Paser. Peraturan Daerah Kabupaten Paser Nomor: 4 Tahun 2019 tentang Pengakuan dan Perlindungan Masyarakat Hukum Adat. Tana Paser, Kabupaten Paser, Indonesia. 2019. Available online: https://jdih.paserkab.go.id/assets/library/document/perda-nomor-4-tentang-pengakuan-dan-perlindungan-masyarakat-hukum-adat.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Angi, E.M.; Wibowo, A.; Wiati, C.B. The potential, utilization and management of forest biodiversity for the livelihood of local communities in Ratah Watershed, East Kalimantan Province, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 886, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angi, E.M. Kampung Iklim Plus: Pengembangan Konseptual Program Kampung Iklim di Kalimantan Timur—Gerakan Nasional Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim Berbasis Masyarakat di Kalimantan Timur; The Nature Conservation Indonesia (TNC Indonesia): Samarinda, Indonesia, 2019; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkse, J.; Kolk, A. Addressing the climate change—Sustainable development nexus. Bus. Soc. 2011, 51, 176–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andonova, L.B.; Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H. Transnational climate governance. Glob. Environ. Politics 2009, 9, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T. Promoting the “development dividend” of climate technology transfer: Can cross-sector partnerships help? World Dev. 2007, 35, 1684–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gebara, M.F.; Fatorelli, L.; May, P.; Zhang, S. REDD+ policy networks in Brazil: Constraints and opportunities for successful policy making. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- May, P.H.; Gebara, M.F.; de Barcellos, L.M.; Rizek, M.B.; Millikan, B. The Context of REDD+ in Brazil: Drivers, Actors and Institutions, 3rd ed.; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ismiartha, G.R.; Santoso, R.S.; Hanani, R. Analisis stakeholders dalam kegiatan pengelolaan sampah program kampung iklim (proklim) sebagai upaya mitigasi perubahan iklim dusun soka, desa lerep, kecamatan ungaran barat, kabupaten semarang. J. Public Policy Manag. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hudaya, M.R.; Puspita, D.T. Collaborative governance dalam implementasi program kampung iklim di kelurahan talangbubuk, kecamatan plaju, kota palembang. Komunitas J. Pengemb. Masy. Islam 2021, 12, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan, E. Free, prior, and informed consent in Africa: An emerging standard for extractive industry projects. In Oxfam American Research Background Series; Pfeifer, K., Ed.; Oxfam: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Narendra, B.H.; Siregar, C.A.; Dharmawan, I.W.S.; Sukmana, A.; Pramono, I.B.; Basuki, T.M.; Nugroho, H.Y.S.H.; Supangat, A.B.; Setiawan, O.; Nandini, R.; et al. A review on sustainability of watershed management in Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).