Abstract

This study explored changes in consumers’ perceptions of take-out food before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic using big data collected from social media. Using “take-out food” as a keyword, 18,544 search results were found in 2019, before the COVID-19 outbreak, compared to 20,718 search results in 2021. These keywords were analyzed using text mining, semantic network analysis, CONCOR analysis, and sentiment analysis, respectively, to understand consumers’ perception of take-out food. Using text mining, in 2019, “dining-out” was the most frequent search term associated with take-out food, followed by packing, famous restaurant, family, delicious, menu, and available. In 2021, “dining-out” was again the most popular keyword, followed by packing, famous restaurant, delivery, family, delicious, available, and Corona. A semantic network analysis showed that, in 2019, four categories emerged: delicious, meat, satisfaction, and lunchbox. The same analysis showed that, in 2021, the categories were delicious, meat, good, and home meal. These findings suggest that, after COVID-19, take-out food began to be recognized as a daily meal that can replace home-cooked meals. According to the sentiment analysis, the number of positive keywords decreased by 4.03% after COVID-19, while the number of negative keywords increased at the same rate; regarding the increase in negative keywords, such as sadness, disgust, and fear, since the emergence of COVID-19, consumers’ anxiety about eating out due to the virus was observed. This study can be useful by providing core data and an analysis method necessary for food service companies’ business activities and decision making related to take-out amid consumers’ rapidly changing needs for the dining-out environment caused by COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged at the end of 2019, has brought profound changes to people’s diets and all aspects of their daily life. In South Korea, as the number of COVID-19 cases increased, the government implemented regulations around social distancing and limited the number of private gatherings. Many schools and companies expanded online classes and telecommuting, and people refrained from going out due to concerns about contracting the virus [1]. These shifts of daily life also brought major changes to the food service market, and on-premises restaurants have experienced great difficulties in business compared to before COVID-19. Meanwhile, the delivery and take-out food service markets have grown in sales and are expanding in connection with the online market [2,3,4]. Accordingly, many on-premises restaurants are seeking new measures, such as starting or expanding their take-out services [2,3,5].

With the recent expansion of the restaurant market and the introduction of food technology, various types of dining out are emerging. Although the traditional method of eating out is to dine in the restaurant, the food industry is adopting various types of new services, such as delivering food to a place chosen by the consumer, allowing consumers to visit the restaurant and take food out to eat at another desired place, and providing meal kits that consumers can cook at home [6,7]. These services are made even more convenient through mobile applications or online sites. As consumers prefer non-contact services due to COVID-19, such types of dining out are becoming more popular [8]. According to a 2022 Statista report, the global market for online food delivery service is expected to reach USD 223.7 billion in 2025, up from USD 115.07 billion in 2020 [9,10]. According to the National Restaurant Association [11], approximately 60% of restaurant customers in the United States dine out. Restaurants offer delivery, pick-up, drive-through, and curbside services [11,12]. As such, with the consumers’ demand for non-contact off-premises services increasing as a result of COVID-19, studies are being actively conducted on these areas [9,13,14]. However, to date, studies have largely focused on online food delivery [13,14,15], with take-out services mainly being included in the same category as food delivery [8,16]. In other words, few studies focus exclusively on take-out services. Therefore, it is necessary to examine take-out services, which have increased in popularity among restaurant services due to the expansion of non-contact consumption in the wake of COVID-19. Most importantly, it is necessary to investigate consumers’ changing perceptions of services due to COVID-19, which has had a great ripple effect on the overall restaurant industry.

As non-contact services have become the new normal for consumers’ dining-out behaviors due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, this study aims to investigate the changes in consumers’ perceptions and emotions between pre-COVID-19 (2019) and post-COVID-19 (2021) eras in the context of take-out services using a big data analysis. First, we identified the relevant keywords by collecting big data using the search keywords “take-out food” before and after the onset of COVID-19 and performing text mining. Second, using the derived keywords, we identified the correlation between common words using a semantic network analysis and CONCOR analysis. Finally, we examined the change in emotional keywords by using positive and negative words extracted from data through sentiment analysis. In this way, this study aimed to provide key data and analysis methods that can be useful for food service companies’ business activities and decision making in relation to take-out services amid rapidly changing consumer needs for the dining environment due to COVID-19.

2. Related Studies

2.1. COVID-19 and Dining Out

The COVID-19 pandemic caused major changes in not only living conditions, but also the dining environment, and many studies have investigated how consumer behaviors related to dining out have changed due to COVID-19 [17,18,19]. As non-contact consumption became mainstream during the pandemic, research topics have primarily focused on food delivery services [17,18,20]. Meanwhile, the evolution of digital technologies, including smartphones, has provided technological support for non-contact transactions, thereby accelerating the online food delivery industry, and related research is being actively conducted [13,21]. Shroff, Shah, and Gajjar [13], in their review of online food delivery research, reported that, from 2015—when the first research on online food delivery (OFD) was published—until 2021, 368 papers related to OFD were included in Web of Science’s core collection. Looking at some examples of related studies, Mehrolia, Alagarsamy, and Solaikutty [17] empirically measured the characteristics of customers who ordered and did not order online food during the COVID-19 crisis in India. They investigated respondents’ characteristics such as age, patronage frequency before the lockdown, affective and instrumental beliefs, product involvement, and perceived threat, to investigate significant differences between the two categories of OFD customers. They reported that high perceived threats, less product involvement, low perceived benefit of OFDs, and less frequent online food orders are less likely to lead individuals to order OFD. Brewer and Sebby [20] explored the effect of two dimensions of stimuli—marketing stimuli (menu visual appeal and menu informativeness) and social stimuli (perception of COVID-19 risk)—on desire for food, perceived convenience of online food ordering, and purchase intentions when ordering food online during the COVID-19 pandemic. They discovered the indirect effects of the menu’s visual appeal and informativeness and the perception of COVID-19 risks on consumers’ purchase intentions.

A new research trend is studying the changed dining-out trends and consumption patterns at two different time points before and after the onset of COVID-19. Jung, Yoon, and Song [22] identified words closely associated with the phrase “dining out” using big data gleaned from social media to investigate consumers’ perceptions of dining out and related issues before and after COVID-19. According to the results, before COVID-19, discussions using words such as delicious, nice, and easy were common, but after COVID-19, negative expressions such as struggling and cautious were the main sentiment. The authors noted that, with the outbreak of the pandemic, new search terms such as delivery, take-out, and social distancing emerged. They also reported a decrease in positive emotions and an increase in negative emotions after the outbreak of COVID-19 compared to before the pandemic. Kim and Kim [5] analyzed trends in dining-out consumption before and after the pandemic emerged using text mining of big data such as online comments and SNS. The analysis indicated that, before COVID-19, the internet search for local restaurants mainly related to tourist destinations, family dining out, and family events; after COVID-19, many keywords related to delivery service and specific menus and restaurant names. Zhu et al. [19] studied how the COVID-19 pandemic affected Chinese consumers’ food consumption away from home. They analyzed sales records from a large restaurant chain located in 12 cities in China from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2020. The results indicated that consumers reported ordering and consuming more calories (as well as carbohydrates, protein, fat, and sodium) after the COVID-19 outbreak than during the pre-COVID-19 period. This finding did not support the hypothesis that COVID-19 led consumers to eat more healthily during the pandemic. Chotigo and Kadono [18] examined and compared the important factors that encourage Thai customers to use food delivery apps before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, including external factors such as trust, convenience, application quality, and satisfaction. Their results showed that satisfaction was affected by social influence, trust, convenience, and application quality both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, price value was a significant predictor of satisfaction before the pandemic, but not during the pandemic. On the other hand, habits had a significant influence on satisfaction before the pandemic, but they were found to have a negative influence on satisfaction during the pandemic. The results also showed that satisfied customers who use food delivery apps are more likely to continue using them.

As the COVID-19 pandemic led to a “new normal” in dining environments, more multifaceted studies are needed in order to examine the changes in consumers’ perceptions and behaviors in terms of dining-related services, products, and issues. Moreover, as constant concerns about infectious diseases, such as the emergence of new strains of viruses, continue and create uncertainty in society at large [23], it is important for academics and industry stakeholders to closely examine and learn about changes in consumers’ perceptions due to COVID-19, which will be essential for understanding consumers in a future era of uncertainty.

2.2. Take-Out Food

Delivery and take-out have been explored as the same category in several studies [8,16]. Some studies have focused on fast food among different types of dining out, while certain studies in North America and Europe considered delivery and take-out to be one of the characteristics of fast-food service [24,25,26]. This is related to the study analyzing the cause-and-effect relationship between both geriatric diseases and obesity problems, which have recently intensified in developed countries, and fast-food consumption [6]. Recent studies have also focused on the food delivery market rather than take-out services, as the development of food technology has led to a growing online food delivery market, which is more convenient for consumers [13,14,15]. However, Kim and Go [6] found that delivery and take-out consumption differed depending on individual income, occupation, and weight, revealing heterogeneous characteristics. In addition, Kim [8] divided consumers’ consumption behavior into rational and emotional motives, finding that rational motives such as economic benefit, ease of use, low price, and convenience had a positive effect on delivery choice, while take-out service use increased when emotional motives such as aspiration, change of mood, desire satisfaction, and rest increased along with rational motives. Recently, in restaurants that provide food delivery, not only general setup restaurants, but also cloud kitchens have risen as the mainstream type of business [27,28]. Cloud kitchens mainly provide delivery services and, as a result, take-out options are mostly offered at restaurants with service facilities [27,28]. In addition, curbside and drive-throughs are popular take-out options that are distinct from delivery [12]. Therefore, delivery and take-out services cannot be considered the same as service providers, and the methods of services provided to consumers are also different, meaning consumers’ perceptions and satisfaction toward the related products and services could differ as well.

Although not many recent studies regard take-out food as fast food or a category within online delivery food, certain exceptions exist. Kim and Go [6] analyzed how individual characteristics of Korean adult consumers are related to the consumption of delivery and take-out food. The younger the age or the higher the education level, the higher the rate of consumption of delivery and take-out food reported. According to the authors, higher education levels increase the opportunity cost of time, which in turn increases the rate of choosing time-saving delivery and take-out food consumption options. Meanwhile, younger consumers are more likely to consume delivery or take-out food because it is easier for them to order delivery or take-out food using the Internet or mobile apps according to recent technological advances. These results demonstrate that delivery and take-out foods are non-homogeneous goods, and their consumption varies according to individual weight, income, and occupation. For instance, in the case of delivery food, both the consumption rate and frequency increased as the consumer’s body weight or personal income increased. However, for take-out food, higher body weight meant the subjects were less likely to consume it, but there was also no significant difference in consumption with personal income. Furthermore, in terms of occupation, the frequency of consumption of take-out food was higher among those in service or sales positions. Mura et al. [29] examined whether take-out food consumption mediates the association between socioeconomic status and fruit and vegetable intake and, if so, to what extent. The results showed that the lowest-education group consumed fewer fruits and vegetables than the highest education group, leading to the unhealthy consumption of take-out foods. On the contrary, consumers with higher education levels showed higher consumption of healthy take-out food. Although research on take-out food has been conducted, despite the recent increased demand from consumers due to COVID-19, research in this area is still very limited.

In their review paper analyzing studies of consumers’ reviews of food delivery services, Adak et al. [30] reported that consumers’ complaints commonly related to delivery time, service, food quality, and cost. The Food Consumption Behavior Survey of the Korea Rural Economic Research Institute [31] found that high price, long waiting time, and unsatisfactory taste were the main reasons for rarely or infrequently using delivery services. The most common reasons for using take-out services were saving delivery costs and cheaper prices through discounts on take-out services, followed by a long waiting time for deliveries. In particular, in South Korea, the advancement of food delivery services via mobile applications led to overheated competition due to the explosive demand for delivery, the oligopoly of a small number of applications, and expensive delivery fees [32]. When consumers are dissatisfied with food delivery services, take-out services can provide an alternative.

2.3. Big Data in the Food Service Industry

As the fourth industrial revolution’s technology development supports the demand for non-contact services due to COVID-19, various convenient online dining services have become part of daily life. Big data including various types of information have been created by sharing this information on restaurant service and consumers’ experiences online, making big data analysis an important tool for understanding industry trends [23]. Consumers share their experiences, emotions, and opinions related to various food products, services, and organizations through online comments and posts. Accordingly, it is important to extract meaningful information from the enormous amounts of data and utilize it in research [33]. Big data analyses can collect a large amount of data accumulated in daily life quickly and accurately. These data can then be used to analyze consumers’ opinions objectively. Therefore, the analysis of big data reflecting consumers’ opinions in everyday life is of great help when it comes to discovering new results or valuable implications not revealed in previous studies using interview or survey techniques [34].

Typical methods of big data analysis include text mining, semantic network analysis, convergence of iteration correlation (CONCOR) analysis, topic modeling, and sentiment analysis [34,35]. This study used text mining, semantic network analysis, CONCOR analysis, and sentiment analysis to understand consumers’ perceptions of take-out food before and after the onset of COVID-19. Text mining is a method of extracting meaningful keywords from unstructured data collected through natural language-processing technology in order to discover useful information and new knowledge that has not previously been revealed [34,36]. In addition, text mining can extract the main keywords from numerous texts in large-scale text data, and the extracted texts can be utilized for sentiment analysis and network analysis [37]. A semantic network analysis is a method of applying social network analysis to text analysis, extracting meaningful words from texts, and identifying the connection system formed through the extracted words and their relationships [38]. In addition, semantic network analysis, like social network analysis, is an analysis method that identifies a phenomenon through a network constructed by representing a specific action entity as a node and the connection between nodes as a link [37]. To understand the characteristics of the network connection structure, degree centrality—an index derived through semantic network analysis—is used, which represents how frequently it is used with other connected keywords [39]. Semantic network analysis helps grasp the meaning of text precisely in detail by identifying keywords that appear simultaneously and adjacent to each other [34,40]. A CONCOR analysis derives clusters formed by words that share similarities based on a semantic network analysis and enables intuitive understanding of the entire network structure. This method is used to find and classify nodes with similarities in structurally equivalent positions among the connections of nodes using correlation coefficients for the main keywords [34,41]. A sentiment analysis, also called opinion mining, is a method of analyzing people’s opinions, sentiments, evaluations, appraisals, attitudes, and emotions about products, services, organizations, individuals, issues, events, and topics [42,43]. In general, it is used to classify emotions expressed in texts or to convert them into objective numerical data. In a narrow sense, it can be seen as classifying positive and negative emotions in the text [44]. In addition, this analysis method includes not only simply classifying positive and negative, but also analyzing the intention or stance of the writer by extracting positive and negative words [45].

Recent studies applying big data have been actively utilized to understand the food service industry. Most studies employ customers’ reviews and ratings on Google Maps [46,47] or travel, hotel, and restaurant platforms such as Yelp or TripAdvisor [48,49,50] to investigate words implying positive or negative evaluations [46] and the effects of the intensity of emotions in reviews, length of reviews, and expertise of reviews [50]. For example, Shin et al. [46] collected 5427 restaurant reviews from Google Maps and performed a sentiment analysis. The importance of the collected words was vectorized, and the positive and negative coefficients of the words in the review were calculated using machine learning. The researchers identified four evaluation categories: food, price, service, and atmosphere. They also identified words to detect positives and negatives in restaurant evaluations in each aspect. Mathayomchan and Taecharungroj [47] analyzed 935,386 Google Maps reviews of 5010 restaurants in London, Birmingham, and Manchester to examine the effects of restaurant attributes and the underlying factors impacting overall customer experience within a range of different restaurant types. They used the VADER sentiment analysis algorithm to measure sentiment related to four key restaurant attributes: food, service, atmosphere, and value. They also tested the relationship between these attributes and five-star ratings, and the top 30 food items of eight types of restaurants were analyzed to explore factors that elicited positive and negative evaluations. Li, Liu, and Zhang [50] examined the impact of emotional intensity on perceived review usefulness, as well as the moderating effects of review length and reviewer expertise with text mining data from 600,686 reviews of 300 popular restaurants in the US from Yelp. Jia [48] analyzed online reviews of restaurant tourist customers from China and the United States using text-mining methods and compared their motivation and satisfaction. The results suggested that Chinese tourists were less inclined to assign lower ratings to restaurants and were more strongly fascinated by the food offered, whereas American tourists were more likely to be fun seeking and were less uncomfortable with crowdedness. Oh and Kim [49] collected 19,194 online reviews from 262 fine dining restaurants on TripAdvisor, classified into Japanese, Cantonese, French, and Italian cuisine, and analyzed the reviews corresponding to each ethnic cuisine by performing a semantic network analysis and Clauset–Newman–Moore clustering. The semantic network analysis revealed that several distinguishable clusters of specific words about the reviewer’s Hong Kong fine dining experience were displayed in each cuisine.

Although recent studies have applied big data in the food service industry field, the sources of the data are limited to a few popular global applications or websites with many user reviews, and research topics are also focused on factors with an impact on consumer reviews. Considering that a big data analysis can quickly and accurately collect a large amount of data accumulated in daily life and objectively analyze consumer opinions, we believe research needs to be expanded to a broader range of dining services and products.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

The aim of this study was to investigate changes in consumer attitudes and sentiments in relation to take-out food in the pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic period by applying big data analytics to social media content. For this purpose, data were collected from Naver and Daum blogs, two representative online platforms in Korea, in addition to portal sites. The findings of this study can be expected to help food service companies better understand and identify consumers’ needs in the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. These online platforms were selected because of ease of data collection compared to Facebook or Instagram, where posts are private, and because these two online platforms contain a large amount of data. Data were collected during two periods: pre-COVID-19 (January 2019 to December 2019) and post-COVID-19 (January 2021 to December 2021). The keyword entered in the data search was take-out food. Table 1 shows the search results using “take-out food” as the keywords. In 2019, before COVID-19, in total, 18,544 keywords were searched; in 2021, after COVID-19, in total, 20,718 keywords were searched. In a morphemic analysis, the number of words with a frequency of 10 or more was 3031 in 2019 and 2890 in 2021. Considering that 1000 cases per channel is considered appropriate in TEXTOM-based data collection, the number of keywords included in this study was considered sufficient. Narrative coding for take-out food was clustered according to food, emotion, and demand/purpose (Table 2).

Table 1.

Survey of collected data.

Table 2.

Narrative coding index.

3.2. Methodology and Summary Statistics

A number of governments have utilized data-driven decision making to respond to the unprecedented challenges posed by science and the coronavirus [51]. According to a recent report, big data analytics is predicted to be the most influential technology in the industry over the next 5 years [52]. In this study, online data were collected and refined in an effort to apply the big data of social media before and after COVID-19. TEXTOM was used as a big data analysis solution for the research. Core keywords extracted using TEXTOM were clustered into similar groups, and then the analysis tool Ucinet6 was used to detect relationships between these groups of keywords. NodeXL was utilized as a visualization tool, which is based on network analysis data of centrality value, density, clustering, etc. In this study, several analysis methods—including text mining, semantic network analysis, CONCOR analysis, and sentiment analysis—were employed. Text mining is a technique for extracting information from unstructured text data. Using this method, useful words were extracted based on natural language processing and morpheme analysis technology. Major text mining indicators, such as frequency of occurrence and TF-IDF, were then calculated. Semantic network analysis and CONCOR analysis were performed to identify correlations between co-occurring words based on the text mining analysis data. In this study, the following four indicators were considered: (1) the degree of connection, where the higher the value, the higher the correlation with other variables; (2) betweenness centrality, where the higher the value, the greater the mediating role in the presence of other variables; (3) closeness centrality, where the higher the value, the greater the likelihood of a connection with other variables; (4) page link, where the higher the value, the higher the popularity, which means that the connection lines preferentially flock to nodes with more important pages or information. Finally, sentiment analysis—a natural language processing technology that analyzes subjective data, such as people’s attitudes, opinions, and tendencies, from a text—was performed by extracting positive and negative words from the data. The words were classified using the emotional vocabulary dictionary independently created by TEXTOM, and their frequency and emotional intensity were then calculated.

4. Results

4.1. Text Mining Analysis

Table 3 shows the results of the text mining analysis using the keyword of take-out food for 2019. The frequency analysis of keywords in documents extracted using take-out food as the keyword revealed that “dining-out” was the most frequent keyword, followed by packing, famous restaurant, family, delicious, menu, and available. This finding indicates that these words appeared frequently in the keyword search of take-out food. The high frequency of their appearance also indicates that they were being utilized with great importance. Some keywords, such as famous restaurant, family, pigs’ feet, foundation, kitchen, pork cutlet, and sushi, showed significantly higher TF-IDF values than others. This means that these words have a very rare value for take-out food and that they are essential words. As TF-IDF, in particular, has meaningful implications for short-term trend analysis, it can be inferred that these keywords acted as major factors in the take-out food trend in 2019.

Table 3.

Text mining of take-out food (2019).

According to the results of the text mining analysis for 2021 (Table 4), “dining out” appeared most frequently, followed by packing, famous restaurant, delivery, family, available, and Corona. The following keywords had high TF-IDF values: famous restaurant, ribs, food, sushi, dining table, criticism, and abalone. This indicates that the scarcity value of these words was significantly high among documents related to take-out food after COVID-19. In 2021, after COVID-19, new keywords that did not exist before COVID-19, such as food and dining table, appeared, which indicates that these new keywords started playing an influential role.

Table 4.

Text mining of take-out food (2021).

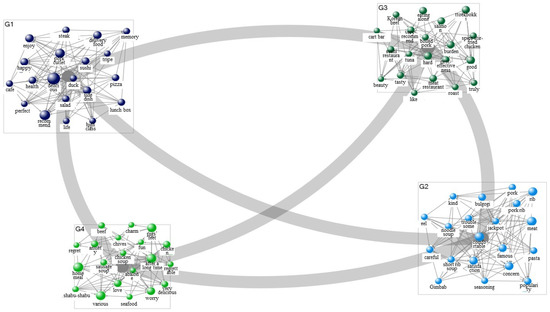

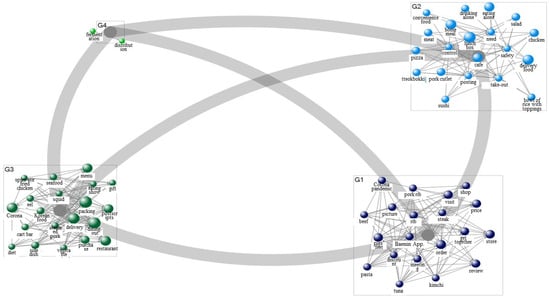

4.2. Semantic Network Analysis

A semantic network analysis of take-out food was conducted by combining the emotions and demands (purposes) of data for 2019 and 2021. Table 5 summarizes the results of the semantic network analysis of take-out food and consumers’ emotions for 2019. The results showed that discussion including terms such as delicious, recommended, meat, ribs, highly recommended, satisfaction, lunch box, etc., had been formed based on degree centrality, betweenness centrality, closeness centrality, and page rank. Figure 1 illustrates the results of visualizing the semantic network following the clustering process. The analysis results were separated into four categories: delicious, meat, satisfaction, and lunch box. It was presumed that people looking up take-out food in 2019 performed the search to find places where they could take out delicious food with high satisfaction. According to the results of the semantic network analysis in 2021 after COVID-19 (Table 6), discussion including terms such as delicious, recommend, meat, comfortable, good, home meal, and various had been formed. The visualized results were divided into four categories: delicious, meat, good, and home meal (Figure 2). This finding indicates that after COVID-19, people perceived the emotions related to satisfaction with the safety with a relatively high value in order to eat home-cooked meals.

Table 5.

Sentimental network index of take-out food (2019).

Figure 1.

Sentimental network visualization of take-out food (2019).

Table 6.

Sentimental network index of take-out food (2021).

Figure 2.

Sentimental network visualization of take-out food (2021).

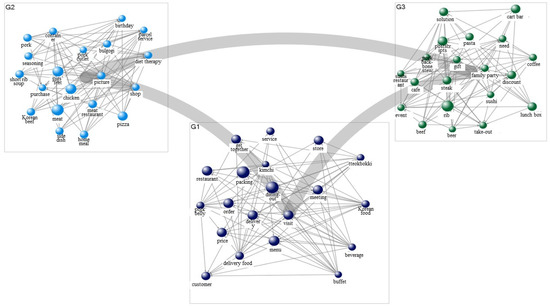

Table 7 summarizes the results of the semantic network analysis, which connected take-out food and demands (purposes) for 2019, which was before COVID-19. In terms of the demand for take-out food, the analysis revealed that discourses about packing, dining-out, meat, pigs’ feet, chicken, and ribs had been formed. The results based on this finding were divided into three categories: packing, meat, and ribs, which indicated that the search was performed for the purpose of taking out food, such as meat and ribs (Figure 3). In contrast, according to the results of the semantic network analysis for 2021 (Table 8), in terms of the demand for take-out food, discourses about order, store, lunch box, food delivery, home meal, packing, dining out, delivery, and Corona had been formed. Notably, and unlike in 2019, in 2021, new keywords such as lunch box, home meal, and Corona appeared, rather than the menu of usual take-out food such as pigs’ feet and chicken, which indicated that food that can be eaten on a daily basis had been changed into food for take-out. The visualized results were divided into four categories: order, lunch box, packing, and fermentation (Figure 4). Based on these results and according to the results of the semantic network analysis of data collected in 2019 and 2021, different sets of keywords appeared before and after COVID-19, with discussions including terms such as delicious, recommend, meat, and ribs in 2019 and discussions including terms such as delicious, recommend, meat, comfortable, and good in 2021. In addition, as for the network for demands in 2019, keywords such as packing, dining out, meat, pigs’ feet, and chicken appeared together. In 2021, new keywords such as order, store, lunch box, food delivery, and home meal appeared together. These findings revealed vastly different demands/necessary purposes before and after COVID-19.

Table 7.

Demand network index of take-out food (2019).

Figure 3.

Demand network visualization of take-out food (2019).

Table 8.

Demand network index of take-out food (2021).

Figure 4.

Demand network visualization of take-out food (2021).

4.3. Sentiment Analysis

Sentiment analysis was performed by extracting positive and negative words from the data (Table 9). When the data obtained in 2019 and 2021 in relation to take-out food were compared, the number of positive keywords among sentiment words decreased by 4.03% in 2021, whereas the number of negative keywords increased in 2021 by 4.03% (Table 10 and Table 11). Specifically, sub-emotions of positive categories (e.g., joy, interest) decreased in 2021 compared to 2019, and sub-emotions of negative categories (e.g., sadness, disgust, and fear) increased in 2021 compared to 2019.

Table 9.

Sentiment word frequency of take-out food.

Table 10.

Sentiment analysis of take-out food (2019).

Table 11.

Sentiment analysis of take-out food (2021).

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

This study explored changes in consumers’ perceptions and emotions with regard to take-out food before and after the onset of COVID-19 by applying big data from social media. A semantic network analysis of take-out services and consumer sentiment classified the 2019 data into four categories: delicious, meat, satisfaction, and lunch box. The 2021 data were categorized as delicious, meat, good, and home meal. Based on these findings, after the COVID-19 outbreak, it seems that take-out food became recognized as a daily meal that can replace home-cooked meals. According to Kim and Kim [5], who studied the changes in dining-out consumption before and after the COVID-19 outbreak by using big data, before COVID-19, search keywords related to “dining out” were mainly centered around tourist destinations, dining-out information for families gathering for special occasions, and information searches for restaurant foundation; however, after COVID-19, keywords related to food delivery services ranked at the top, and searches for specific menus and restaurant information increased in comparison to general restaurant information. These findings can be interpreted in a similar context as the results of the current study in that, before COVID-19, search terms related to dining out mainly concerned restaurants during travel or for special events whereas, after COVID-19, searched words related to delivery or accessible specific menus and restaurant information to replace meals on a daily basis. In particular, these results can be interpreted more specifically based on the semantic network connecting take-out services and demands (purposes). In 2019, words searched for the purpose of taking out food, such as packing, meat, and ribs, were predominant. In 2021, keywords such as lunch box, home meal, and Corona appeared, confirming the changed demands/necessary purpose of take-out food that can be eaten on a daily basis, such as home-cooked meals, due to COVID-19. The increased use of such keywords confirmed the changed needs and purposes for packaging food that can be eaten similar to home meals due to COVID-19. Indeed, Lee and Ryu’s [53] study dealt with changes in mothers’ meal preparation stress and food consumption patterns at home after COVID-19 through a qualitative study, as children have spent more time at home due to the expansion of online education in light of COVID-19. The authors reported that stress related to meal preparation went up regardless of the mother’s employment status. Accordingly, although the frequency of dining in significantly decreased, the frequency of home delivery of food and online grocery shopping substantially increased. Similar trends have been observed in the United States [54,55], the Netherlands [56], Indonesia [57], Denmark, and Germany [58], among others.

Meanwhile, the result of this study’s sentiment analysis, which extracted positive and negative words from the search word data related to take-out food, showed that the number of positive keywords decreased by 4.03% after the outbreak of COVID-19, while the number of negative keywords increased at the same rate. Factors affecting consumers’ emotions related to take-out services are believed to be attributes related to menus and services or external environmental influences. However, considering the main focus of this study on changes in consumers’ perceptions due to COVID-19 and changes in consumers’ emotions identified in the results of the sentiment analysis, here, we highlight the changes in consumers’ sentiment toward take-out services caused by COVID-19. Several studies have been conducted to understand the changes in consumers’ emotional, psychological, or other perceptions caused by COVID-19; the results tend to vary. Some studies reported that negative emotions or perceptions caused by COVID-19 toward take-out services or online delivery services, such as anxiety, perceived severity, and perceived vulnerability, did not affect consumers using these services [2,8]. However, Smith et al. [59] found that stress associated with COVID-19 increases food motivation in all food categories. In particular, consumers in the group with the highest stress expressed a greater willingness to pay than the other groups for all types of delivery or take-out food presented in the study. In general, all groups in the study were willing to wait longer or pay more for delivery or take-out food, such as sweets and fast food, than for relatively healthy food, such as savory snacks or vegetables. Kim [8] reported that not only rational motives, such as economic benefit, convenience, and labor saving, but also emotional motives, such as changes in mood, fulfillment of desire, comfort, and rest, had a positive effect on consumers’ choice of take-out food. In many studies, in general, severe acute stress can inhibit food intake; however, when eating serves as an adaptive means for stress relief, stress has been reported to stimulate food intake [59,60,61,62]. Given the increase in take-out consumption in South Korea after COVID-19 [31,63], some of the negative sentiment words (e.g., sadness, fear) that appeared after COVID-19, as found in this study, may have led to the consumption of take-out food. Certainly, some of the negative emotions (e.g., disgust, anger, fright) could have been caused by dissatisfaction with products or services, as more consumers purchased take-out meals more frequently than before. Byrd et al. [64] investigated the risk perception of restaurant food and packages among American consumers during the pandemic, and restaurant food packages were ranked the highest after cooked and uncooked food served in dine-in restaurants. However, carry-out/curbside pick-up/drive-through foods ranked relatively low in terms of risk perception. These findings suggest that concerns about infection through the packaging of take-out food, which were not previously raised, also contributed to negative emotions during the pandemic. Factors related to negative emotion keywords that have increased since COVID-19 need to be identified in greater detail through follow-up studies.

5.2. Implications

As uncertainty related to politics, the economy, and society in general grows due to climate change and pandemic, the change cycle of the food service industry and consumer trends are also getting shorter. The biggest issue of these recent uncertainties is COVID-19, and it is essential for the food service industry as a whole to understand consumers’ perceptions and changing trends. As many dine-in restaurants started providing take-out services to recover from poor sales due to COVID-19 and to respond to consumer needs, the perceptions of consumers examined in this study are expected to provide practical information necessary for the marketing plans of food service business. Specifically, this study found that, after COVID-19, consumers recognized take-out food as a home meal; this idea can be developed and applied to menu development and/or promotions. In other words, it is possible to apply the characteristics of home meals that are not special, but comfortable, and can be eaten on a daily basis, to the development of restaurant menus, and promote them in this way. As for individual menu keywords with high frequency or TF-IDF values, pigs’ feet, pork cutlet, and sushi were popular in 2019, but ribs, sushi, dining table, pigs’ feet, and abalone were more popular in 2021. This finding can be used for menu development that satisfies current consumer trends. As for menu-related keywords that appeared both before and after the onset of COVID-19, dinner showed a high TF-IDF in text mining, and meat was mentioned as a common topic of discourse in sentiment analysis. These findings suggest that consumers mainly use take-out food for dinner, and that there is a continuing interest in the meat on the menu, which provides important insights when developing a main menu for take-out services. In addition, regarding the increase in negative keywords, such as sadness, disgust, and fear, since the emergence of COVID-19, consumers have great anxiety about dining out due to the virus and, therefore, more measures and publicity about hygiene and safety are required to reassure consumers about take-out products, services, and packages. In addition, as previously stated, consumer behaviors surrounding take-out consumption are affected not only by rational motives, but also by emotional motives. Therefore, it is important to apply emotional marketing that can comfort and relieve consumers’ negative emotions related to take-out food.

Academically, this study is meaningful in that it limited the research area to take-out food and examined the changing consumer trends and perceptions of dining out before and after the outbreak of COVID-19 in more detail. In particular, recent research on non-contact dining services has tended to concentrate on online delivery services, with few studies focusing exclusively on take-out services. Therefore, this study, focusing on take-out food, which is still popular as an alternative given consumer complaints about delivery services, is of great value due to its rarity. In addition, from the perspective of research methods, this study is meaningful in that it expanded the scope of big data research by approaching data sources and research topics in a popular and pragmatic way. It is also expected to provide good fundamental data for the practical application of big data research in the food service industry in the future.

5.3. Limitations and Future Study

This study has limitations in several areas. First, there are some limitations in the interpretation of the results, as previous studies on take-out food are scarce. Second, the big data in this study used a Korean-based portal website as the data source; thus, the main consumer group is Korean-speaking consumers, and the interpretation of the study results can be mainly related to the Korean food service market. Therefore, it is difficult to directly apply the results of this study to the cases of other countries, considering that the time and extent of each country’s lockdown and/or quarantine measures due to COVID-19 differ, and the conditions of the food service industry are also different. Therefore, based on these limitations, similar research should be conducted as follow-up research by applying relevant data from other countries. In particular, in the case of some countries with stronger and more stringent quarantine policies than South Korea, such as countries with long lockdown periods or enforced compulsory closures of dine-in restaurants during the pandemic (e.g., the United States [64]), significant differences are expected in consumers’ demands and emotions regarding take-out services since the outbreak of COVID-19. In addition, multifaceted studies on consumers’ behaviors are needed, given the insufficient research on the topic of take-out food. Finally, more qualitative and quantitative research is needed to identify factors that caused the increase in negative sentiment keywords since COVID-19, such as dissatisfaction with products and services or general negativity due to the pandemic, in order to understand their effects on the perceived risk of infection via take-out packaging or food.

This study explored how consumers’ perceptions toward take-out food, which has recently become more popular as a non-contact dining-out service, changed before and after the outbreak of COVID-19. It achieved this by applying big data. Although uncertainty is growing throughout society due to the pandemic, the findings of this study comparing the pre- and post-COVID-19 outbreak in relation to take-out options as a popular dining-out service are expected to have great implications for academia and industry when it comes to understanding consumers in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J. and J.J.; methodology, H.J. and E.L.; software, H.J. and E.L.; validation, H.J. and E.L.; formal analysis, H.J. and J.J.; investigation and data curation, H.J. and J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J. and J.J.; writing—review and editing, J.J. and E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, N.D.; Jeon, M.Y.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, H.E.; Lee, J.Y. Trend Korea 2021; Miraebook Publishing, Co.: Seoul, Korea, 2021; pp. 25–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, C.; Choi, H.; Choi, E.K.; Joung, H.W. Factors Affecting Customer Intention to Use Online Food Delivery Services before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblander, E.S.; McCarthy, D.M. How Has COVID-19 Impacted Customer Relationship Dynamics at Restaurant Food Delivery Businesses? Mark. Sci. Inst. Work. Pap. Ser. 2021, 23, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, D.; Sharma, D. Online Food Delivery Portals during COVID-19 Times: An Analysis of Changing Consumer Behavior and Expectations. Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2020, 13, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Kim, S.C. A Study on the Changes in Eating Out Consumption Using Big Data after COVID-19. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 40, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Go, S. Consumer Characteristics and Food Delivery-takeout Behaviors at Restaurants. Foodserv. Ind. J. 2017, 13, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yeonhap News. Where You Want Michelin Restaurant Food. Market Kurly Special Exhibition. 2022. Available online: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20220803060400003?input=1195m (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Kim, S. A Study on the Relationship of Korean and Chinese Consumers’ Eating-out Motivation, Dining-out, and Delivery Takeout in COVID-19: The Moderation Role of Interpersonal Contact Anxiety. J. Korean Contents 2022, 22, 324–336. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, P.; Kumar, G. Online Food Delivery Companies’ Performance and Consumers Expectations During Covid-19: An Investigation Using Machine Learning Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Online Food Delivery: Highlights. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/eservices/online-food-delivery/united-states/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- National Restaurant Association. Off-Premises Capabilities Are Key. 2019. Available online: https://restaurant.org/research-and-media/research/research-reports/technology-the-off-premises-market/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Kim, O.H. COVID-19 Pandemic and the Food Industry: Navigating the Uncharted. J. Foodserv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2020, 23, 343–365. [Google Scholar]

- Shroff, A.; Shah, B.J.; Gajjar, H. Online Food Delivery Research: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 0959–6119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Nayal, P.; Maseeh, H.I.; Kumar, A.; Sivapalan, A. Online Food Delivery: A Systematic Synthesis of Literature and a Framework Development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 104, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Adenan, A.M.; Ali, A.; Ismail, N.A.S. Living through the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact and Lessons on Dietary Behavior and Physical Well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jae, M.K.; Jeon, H.R.; Lee, Y. Difference Analysis of Consumers for Dietary Life Consumption Behavior Based on Eating Out and Delivering or Taking Out Food Service. J. Consum. Cult. 2017, 20, 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrolia, S.; Alagarsamy, S.; Solaikutty, V.M. Customers Response to Online Food Delivery Services during COVID-19 Outbreak Using Binary Logistic Regression. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotigo, J.; Kadono, Y. Comparative Analysis of Key Factors Encouraging Food Delivery App Adoption before and during the COVID19 Pandemic in Thailand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Lopoz, R.A.; Gao, L.; Liu, X. The Covid-19 Pandemic and Consumption of Food Away from Home: Evidence from High-frequency Restaurant Transaction Data. China World Econ. 2021, 19, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, P.; Sebby, A.G. The Effect of Online Restaurant Menus on Consumers’ Purchase Intention during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. 2021, 94, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; Han, S.P. Estimating Demand for Mobile Applications in the New Economy. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 1470–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H.; Song, M.K. A Study on Dining-out Trends Using Big Data: Focusing on Changes since COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsis. A New World after COVID-19, “New Normal” of Crisis and Opportunity. 2020. Available online: https://newsis.com/view/?id=NISX20200419_0000998415&cID=10401&pID=10400 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Gopinath, B.; Flood, V.M.; Bulutsky, G.; Louie, J.C.Y.; Baur, L.A.; Mitchell, P. Frequency of Takeaway Food Consumption and Its Association with Major Food Group Consumption, Anthropometric Measures and Blood Pressure during Adolescence. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 2025–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; McNaughton, S.A.; Gall, S.L.; Blizzard, L.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A.J. Takeaway Food Consumption and Its Associations with Diet Quality and Abdominal Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Study of Young Adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffe, L.; Uwamahoro, N.S.; Dixon, C.J.; Blain, A.P.; Danielsen, J.; Kirk, D.; Adamson, A.J. Supporting a Healthier Takeaway Meal Choice: Creating a Universal Health Rating for Online Fast-food Outlets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Washington Post. A Pandemic Surge in Food Delivery Has Made Ghost Kitchens and Virtual Eateries One of the Only Growth Areas in the Restaurant Industry. 2020. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/09/17/virtual-ghost-kitchen-restaurants/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Hankyung Economy. The Evolution of Cloud Kitchens… Purchase, Order, and Delivery Are “Quickly”. 2022. Available online: https://www.hankyung.com/economy/article/2022030702071/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Mura, M.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G. Contribution of Take-out Food Consumption to Socioeconomic Differences in Fruit and Vegetable Intake: A Mediation Analysis. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1556–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adak, A.; Pradhan, B.; Shukla, N. Sentiment Analysis of Customer Reviews of Food Delivery Services Using Deep Learning and Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Systematic Review. Foods 2022, 11, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korean Rural Economic Institute. Food Consumption Behavior Research. 2021. Available online: https://www.krei.re.kr/krei/researchReportView.do?key=67&pageType=010101&biblioId=530219 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Jeong, M.; Choi, K. Analysis of Major Topics for Platform Services for Delivery Orders before and after Covid-19 with the Use of Text Mining Techniques. Reg. Ind. Rev. 2021, 44, 283–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, F.A.; Hassaballah, M.; Ali, A.A.; Nam, Y.; Ibrahim, A.I. COVID19 Outbreak: A Hierarchical Framework for User Sentiment Analysis. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 70, 2507–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.W.; Namkung, Y. Understanding Consumers’ Perceptions of the Fresh-food Delivery Platform Service Based on Big Data: Using Text Mining and Semantic Network Analysis. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 30, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.T. A Study on the Consumer Perceptions of Meal-kits Using Big Data. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 35, 227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Hotho, A.; Nürnberger, A.; Paaβ, G. A Brief Survey of Text Mining. LDV Forum 2005, 20, 19–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Park, D.H.; Kim, M.S. A Study of Perceptions of Jeju-island Tourism Using Social Media Big Data Analysis: Before and after the Outbreak of Ban on Korean Entertainer’s. Tour. Leis. Res. 2018, 30, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Choi, M.I.; Kim, D.W. Semantic Network Analysis of Public Relations Research a Comparison of the Journal of Public Relations Research in Korea and the United States. J. Public Relat. 2013, 17, 120–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H. An Essay for Understanding the Meaning of the Network Text Analysis Results in Study of the Public Administration. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. IHSS 2015, 16, 247–280. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.S. A Content Analysis of Journal Articles Using the Language Network Analysis Methods. J. Korean Soc. Inf. Manag. JKOSIM 2014, 31, 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.J. Social Network Analysis, 4th ed.; Parkyoungsa: Seoul, Korea, 2016; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. 2012. Available online: https://www.cs.uic.edu/~liub/FBS/SentimentAnalysis-and-OpinionMining.pdf/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, J.Y. Sentiment Analysis of Twitter Reviews toward Convenience Stores Customer in Korea. Glob. Bus. Adm. Rev. 2019, 16, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.E.; Park, S.H.; Kim, W.J. Automatic Construction of a Negative/Positive Corpus and Emotional Classification Using the Internet Emotional Sign. J. KIISE 2015, 42, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.M.; Choi, K.W. A Study on Restaurant Selection Attribute & Satisfaction Using Sentiment Analysis: Focused on On-line Reviews of Foreign Tourist. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 30, 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, B.; Rye, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D. Analysis on Review Data of Restaurants in Good Map through Text Mining: Focusing on Sentiment Analysis. J. Multimed. Inf. Syst. 2022, 9, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathayomchan, B.; Taecharungroj, V. How Was Your Meal? Examining Customer Experience Using Google Maps Reviews. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S. Motivation and Satisfaction of Chinese and U.S. Tourists in Restaurants: A Cross-Cultural Text Mining of Online Reviews. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, M.; Kim, S. Dimensionality of Ethnic Food Fine Dining Experience: An Application of Semantic Network Analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. Online Persuasion of Review Emotional Intensity: A Text Mining Analysis of Restaurant Reviews. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Khan, Z.; Wang, X. COVID-19 Pandemic in the New Era of Big Data Analytics: Methodological Innovations and Future Research Directions. Br. J. Manag. 2021, 32, 1164–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yallop, A.; Seraphin, H. Big Data and Analytics in Tourism and Hospitality: Opportunities and Risks. J. Tour. Future 2020, 6, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Ryu, S. Qualitative Research on Mothers’ Stress Level of Meal Preparation and Change on Food Consumption Pattern in Context of COVID-19. J. Korean Cont. 2022, 22, 695–709. [Google Scholar]

- Chenarides, L.; Grebitus, C.; Lusk, J.L.; Printezis, I. Food Consumption Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Agribusiness 2020, 37, 44–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, B.; McFadden, B.; Rickard, B.J.; Wilson, N.L.W. Examining Food Purchase Behavior and Food Values during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2020, 43, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, M.P.; Gillebaart, M.; Schlinkert, C.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Derksen, E.; Mensink, F.; Hermans, R.C.J.; Aardening, P.; Ridder, D.; Vet, E. Eating Behavior and Food Purchases during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Cross-sectional Study among Adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2021, 157, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.P.; Tanto, H.; Mariyanto, M.; Hanjaya, C.; Young, M.N.; Persada, F.P.; Miraja, B.A.; Redi, A.A.N.P. Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Online Food Delivery Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Its Relation with Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Chang, B.P.I.; Hristov, H.; Pravst, I.; Profeta, A.; Millard, J. Changes in Food Consumption during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analysis of Consumer Survey Data from the First Lockdown Period in Denmark, Germany, and Slovenia. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 635859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.R.; Jansen, E.; Thapaliya, G.; Aghababian, A.H.; Chen, L.; Sadler, J.R.; Carnell, S. The Influence of COVID-19-related Stress on Food Motivation. Appetite 2021, 163, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.; Jimenez, S.; Brownell, K.; Stoney, C.; Niaura, R. Are Stress Eaters at Risk for the Metabolic Syndrome? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1032, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, G.; Wardle, J. Perceived Effects of Stress on Food Choice. Physiol. Behav. 1999, 66, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.A.; Brownell, K.D. The Stress-eating Paradox: Multiple Daily Measurements in Adult Males and Females. Psychol. Health 1994, 9, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Rural Economic Institute. Food Consumption Behavior Research. 2019. Available online: https://www.krei.re.kr/krei/researchReportView.do?key=67&pageType=010101&biblioId=523173 (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Byrd, K.; Her, E.S.H.; Fan, A.; Almanza, B.; Liu, Y.; Leitch, S. Restaurants and COVID-19: What Are Consumers’ Risk Perceptions about Restaurant Food and Its Packaging during the Pandemic? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).