Abstract

After the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, Chinese officials claimed that the goal of “driving 300 million people to participate in ice and snow sports” had been achieved. Historically, the London 2012 Olympic Games had a similar goal: to increase sports participation for all by hosting the Olympic Games. Given these goals, the impact of the Olympic Games on sports participation has clearly become significant. These impacts can be referred to as the Olympic sport participation legacy, an intangible Olympic legacy. The Olympic sport participation legacy has attracted a lot of researchers’ interest in the academic field in recent years. This paper aims to conduct a scoping review of Olympic sport participation legacy studies between 2000 and 2021 to identify the progress of studies on the sustainability of Olympic sport participation legacies. Unlike previous scoping reviews on sport participation legacies, this review adopts a Patterns, Advances, Gaps, Evidence of Practice, and Research Recommendations (PAGER) framework at the results analysis stage to improve the quality of the findings. The results from the scoping review contained 54 peer-reviewed articles on three levels of research: the population level, social level, and intervention processes. Many studies indicate that achieving a sustainable Olympic sport participation legacy requires joint collaboration and long-term planning between governments, community organisations, and other stakeholders.

1. Introduction

In the most recent Olympic Charter, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) sets out the development objectives and requirements for building a sustainable Olympic legacy, making the Olympic Games have a positive and sustainable Olympic legacy for the host city, region, and country and promoting sports development in the host country [1]. The Olympic sport participation legacy is an intangible and positive Olympic legacy, and its main role is to increase the sports participation of the population in the host country [2,3,4].

Beijing’s 2022 Olympic hosting bid set out the goal of “engaging 300 million people to participate in snow and ice sports” through the Winter Olympics, an objective that has attracted global interest in the sports participation legacy of the Olympic Games. Historically, the London 2012 Olympics bid made a similar promise to encourage more people across the United Kingdom to participate in sports by hosting the Olympic Games [5,6,7]. The motto of the London 2012 Olympics was to “inspire a generation”, which implied that London would use the Olympic sport participation legacy to inspire people across the country, especially the young, to participate in sports and increase participation rates [7,8,9]. The State General Administration of Sports of China [10] claimed that, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, from the successful bid for the Beijing Winter Olympics (July 2015) to October 2021, the number of people participating in snow and ice sports nationwide reached 346 million, accounting for 24.56% of China’s total population. and the promise of driving 300 million people to participate in snow and ice sports was fulfilled. This shows the positive effect that the Olympic sport participation legacy can have on promoting sports participation for all.

Numerous studies on the impact of the Olympic Games on sports participation in host countries emerged following the successful bid to host the London 2012 Olympic Games. Scholars also investigated the sports participation in host countries following previous Olympic Games in order to produce empirical evidence that hosting the Olympic Games can increase sports participation [11,12,13,14,15]. Furthermore, some scholars have even hypothesised that the Olympic Games can positively influence sports participation in the host country [16,17,18,19]. To date, although there is still a lack of sufficient evidence to prove that hosting the Olympic Games can really bring an increase in sports participation in the host country, hosting the 2022 Winter Olympics made Beijing the world’s first dual Olympic city [20], and the achievement of sports participation targets for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games offers new opportunities for research on the Olympic sport participation legacy.

Research related to the Olympic sport participation legacy has an interdisciplinary character that encompasses political, cultural, demographic, and health aspects. This paper will scope a review of related research on the Olympic sport participation legacy, attempting to identify the extent of current research objectives, research progress, and prospects for future research. The aim is to make a contribution to the sustainable development and utilisation of the Olympic sport participation legacy.

2. Methods

A literature review is normally used to collect the literature and analyse the current state of research in a particular academic field, identifying its latest achievements or remaining gaps [21]. This can be an important guide to research in an academic field. A scoping review is a particular way of conducting a literature review, with Arksey and O’Malley [22] suggesting that there are different levels of breadth and depth regarding the application of a scoping review, depending on the researchers’ needs. Such needs can be divided into four categories: (1) to provide a quick scoping of the research areas, (2) to identify whether the research areas are worthy of systematic review (that is, whether a significant amount of the relevant literature exists or has been reviewed systematically), (3) to summarise the existing research findings, and (4) to identify gaps through analysis of the existing research to provide guidance for future research [22]. The purpose of this paper falls into the latter two categories, summarising the existing research on the Olympic sport participation legacy and identifying the existing shortcomings and gaps.

The scoping review steps were adapted from Arksey and O’Malley’s [22] methodological framework and were conducted in five steps (Table 1).

Table 1.

Five-step scoping review framework.

In order to extend the breadth and depth of the scoping review, two methods have been included in the literature search process (step 2): a database search and a systematic manual search [21]. Moreover, to improve the quality and practicability of the literature review, this paper adopts a structured approach to summarising, analysing, and reporting the results (step 5) as proposed by Bradbury et al. [23]: the Patterns, Advances, Gaps, Evidence of Practice, and Research Recommendations (PAGER) framework. The use of the PAGER framework will be explained in detail in the following section.

2.1. Identification of Research Questions and Related Studies

The research question in this paper is as follows: “What are the findings of the research on the Olympic sport participation legacy, and are there any gaps?” This is step 1, and an initial reading of relevant articles [6,7,15,24] was used to identify the keywords and terms used in the selection of articles (step 2). The criteria for article selection were peer-reviewed articles or book chapters, full texts available online, being written in English, assessing the impact of the Olympic Games on sport participation, the development and utilisation of the Olympic sport participation legacy, and the Olympic Games, including the Winter and Summer Games as well as the Paralympic and Youth Olympic Games.

2.2. Study Selection

The selection of articles for this review was completed in two parts: one by means of a database search and the other by means of a manual search. In general, database searching is used more frequently in literature reviews, while manual searching is less common. The research topic of this review is the study of the Olympic sport participation legacy, which is a social science field with a multidisciplinary nature, indicating that potential articles may be found in databases or journals in other subject areas [21]. The manual search method can be helpful for allowing for a more comprehensive and systematic review of the entire scope. Therefore, it was necessary to use the manual searching method to expand the scope of the search for potential articles. The article search process was conducted in April 2022, and the database search and manual search for articles covered 21 years of articles from 2000 to 2021 (included). All articles are available online in English.

2.2.1. Database Search

The selection of databases was based on the research topic, and after an initial reading, the following two databases were selected for searching in this review with a search year range from 2000 to 2021 (inclusive): the Sports Medicine & Education Index and the Web of Science. The keywords used for the search were as follows: (sport participat) OR (physical activ) AND Olympic OR (Olympic legacy) OR (Olympic heritage). The keywords used in this search included the strings “participat” and “activ” in order to avoid missing articles that contained the terms “participate, participation, participating” and “active, activity, activities”. The initial search identified a total of 1550 articles, and the removal of duplicates resulted in 1379 articles.

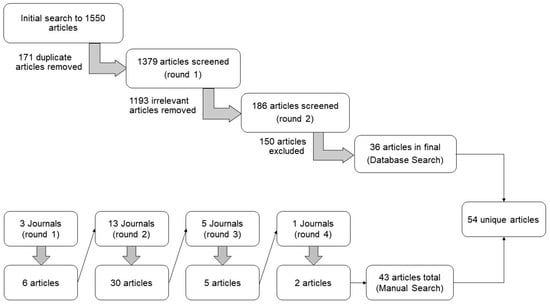

The database search for articles consisted of a two-round screening process designed to remove irrelevant articles and to filter out the most relevant articles to the research topic. In round 1, articles that were not relevant to the research topic were excluded based on the title and abstract of the article. As a result, 1193 irrelevant articles were excluded from the 1379 articles, leaving 186 articles for round 2’s screening. In round 2, after a full-text reading of these 186 articles, the most relevant articles to the research topic were left. This means that the articles that focused on the development and utilisation of the Olympic sport participation legacy as key issues of the full-text were finally selected for the database search. In contrast, articles that did not make the Olympic sport participation legacy their main research focus (e.g., articles that simply posed that there was a relationship between the Olympic Games and the sport participation legacy without any in-depth explanation or analysis) were excluded. After round 2’s screening, 36 articles were eventually included in the database search results. Figure 1 (top part) provides a visual overview of the entire database search process.

Figure 1.

The process of database searching and systematic manual searching.

2.2.2. Systematic Manual Search

The systematic manual search process can make an entire scope review more systematic and comprehensive. According to Teare and Taks [21], the search process is conducted in a total of three steps: (1) selecting the top journals in a specified field by identifying by their impact factor, (2) searching for articles related to the research topic by keywords within a specified period of times, where articles are selected based on their titles and abstracts as well as a full-text reading, and those that meet the criteria are eventually included in the selection, and (3) after selecting the relevant articles in the top journals, the reference lists of these articles are checked one by one to find other relevant journals, followed by a manual search of these relevant journals. Steps 2 and 3 were repeated until no new journals appeared.

The research topic of this review is the development and utilisation of the Olympic sport participation legacy and the relationship between the Olympic Games and sports participation. Through our initial searches and readings, a large number of relevant studies were found within journals in the field of sport management. Therefore, the top journals in the field of sport management were used as a starting point for the systematic manual search. In addition, due to the multidisciplinary nature of this research topic, the manual search process was not limited to the field of sport management. This is also the reason why a systematic manual search approach is necessary for a scoping study of multidisciplinary fields [21].

The top three journals in the sport management discipline based on their impact factors are Sport Management Review, the Journal of Sport Management, and European Sport Management Quarterly, which were used as a starting point for round 1 of the manual search. First, there was a search of each of the three journals for articles relating to the Olympics and the sport participation legacy. The search was carried out by setting a year range of 2000–2021 and entering keywords. The title and abstract sections of the retrieved articles were browsed for the initial screening. A full-text reading of the initially screened articles was then conducted to determine the final articles to be included in the manually searched article pool. In this review, six relevant articles were found in these three journals. Then, the reference lists for these 6 articles were checked one by one, and 13 new journals were found that required a second round of searching. Using the same search pattern, 30 relevant articles were found in round 2 of searching. The same steps were repeated to find 5 new journals for round 3. In round 3 of searching, 5 relevant articles were found. From these, an additional journal was found for round 4 of searching, during which 2 relevant articles were found, but no new journals appeared in the reference lists of these 2 articles. With the systematic manual search process completed, 43 articles were found. The last two rows in Figure 1 show the whole process of the systematic manual search.

2.2.3. Combining Two Search Methods

Based on the above two search methods, this review found 36 (database search) and 43 (systematic manual search) articles. After combining the articles found by the 2 search methods, 25 articles were found to be identical. This meant that 25 articles were retrieved by both the database search and the manual search. Thus, the two search methods produced a total of 54 unique articles, including 11 articles unique to the database search, 18 articles unique to the manual search, and 25 articles from both search methods. The results of this combination are shown in Figure 1. As stated by Teare and Taks [21], a single identification method is not sufficient to adequately identify articles in multidisciplinary fields. By combining database searching and systematic manual searching, the results provided a more comprehensive picture of the research in the multidisciplinary field.

2.3. Data Analysis with the PAGER Framework

The present scoping review used the updated Patterns, Advances, Gaps, Evidence of practice, and Research Recommendations (PAGER) framework for the analysis and reporting of data. After the article searches were completed, a charting and analysis report step took place. In previous scoping reviews, useful information from all articles was extracted (e.g., authors, year of publication, location of study, purpose of study, and research methods) and analysed descriptively to draw relevant conclusions [22].

However, the criteria for charting and analysing report sessions in previous scoping reviews did not highlight the focus of the analysis and did not provide a detailed description of a particular area [23]. Although earlier scoping studies have also emphasised the use of a clearer and more consistent approach at the data analysis step to improve the quality of the scoping review, there is still no clear and consistent way to achieve this [25]. Nevertheless, the PAGER framework goes some way towards achieving this goal [23]. This review adopted the PAGER framework as a structured approach to the fourth and fifth steps of the scoping review (charting and analysis) for more detailed and accurate charting and data analysis. This review applied the PAGER framework to the data analysis step in order to improve the quality of the report and to provide an understandable review for different recipients. Table 2 shows the implications of the five components of the PAGER framework.

Table 2.

The five domains of the PAGER framework.

3. Results

A total of 54 articles were included in this scoping review, and data and content analyses were conducted. In terms of the years of publication of the articles, the papers were published from 2008 to 2021 (inclusive). Overall, research on the Olympic sport participation legacy showed rapid growth from 2012 onwards, and the majority of the articles (n = 50) were published between 2012 and 2021. Not only that, around half of the articles (n = 26) conducted research on the sport participation legacy of the London 2012 Olympics. In addition, the most recent article on the sport participation legacy of the London 2012 Olympics was published in 2021, making it clear that 9 years after London 2012, research on the sport participation legacy of the London 2012 Olympics is still ongoing.

According to the results of the analysis of the 54 articles, research on the Olympic sport participation legacy can be divided into three broad sections: (1) research related to the Olympic sport participation legacy at the demographic level, (2) research on the Olympic sport participation legacy at the social level, and (3) research on the Olympic sport participation legacy and the intervention process.

3.1. Research Related to the Olympic Sport Participation Legacy at the Demographic Level

The legacy of Olympic sport participation has been studied more often at the demographic level, including the impact of the Olympics on different age groups’ sports participation, the impact of the Olympics on disabled people’s participation in sports, the impact of the Olympics on general families’ sports participation, and the impact of the Olympics on ethnic minorities’ participation in sports.

According to the study, the impact of the Olympic sport participation legacy was found to be different among different age groups. Several papers contain research on four groups: children, youth, adults, and older people. Due to the different criteria for classifying age in different countries and regions, this paper does not delineate the age range specifically. Craig and Bauman [26] used pedometer measurements to examine changes in sport participation among Canadian children before and after the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics (2007–2011) and found that there was no influence from the Winter Olympics. Moreover, the Vancouver Winter Olympics had no influence on sport participation among Canadian adolescents [27]. With regard to the impact of the Olympics on sport participation in the adult population, the London 2012 Olympic sport participation legacy had an impact on the adult population in the UK, and although sports participation peaked immediately after the Games and began to fall back, it was still higher than the pre-Olympic levels [24]. The Sydney 2000 Olympic Games had no impact on adult sport participation in Australia, and although adults had a willingness to participate in sports, they failed to take action [12]. Interestingly, older people are more likely to respond positively to the Olympics [14,24]. The generation of young people who experienced the 1964 Tokyo Olympics have higher sports participation now than other generations, suggesting that older people in Japan were influenced by the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, as demonstrated by a positive response to sports participation [14]. It follows that the Olympic sport participation legacy has different impacts at different ages and that different Olympic Games themselves have different impacts.

Current research on the sport participation of disabled people following the Olympic Games indicates that the Games do not have a positive impact on the motivation of disabled people’s sport participation, and there is even a decline in sport participation. Brown and Pappous [28] examined the reasons for the decline in sport participation for disabled people in the UK after the London 2012 Paralympic Games. The role of Paralympic athletes as models for other people with disabilities had limitations, and the low media coverage of the Paralympic Games was also an issue. There is still a long way to go in using the Paralympic Games as a tool to encourage sport participation by disabled people, which requires full promotion of the Paralympic spirit, a greater integration of disabled people’s sports in terms of other social and cultural factors, and protection of the human rights of disabled people to participate in sports [29].

Current research on the impact of the Olympic Games on the sports participation of ordinary families indicates that the attitudes of the families are negative towards sports participation following the Olympic Games [7,30,31]. Non-friendly Olympic participation mechanisms have resulted in many families not being able to afford to go to the Games live, making them feel distant from the Games.

There is little research on the impact of the Olympic sports participation legacy among ethnic minorities. However, Kokolakakis and Lera-López [32] examined the impact of the London 2012 Olympic Games on sports participation among four minorities in the UK and found that there was a short-lived increase in sports participation and, furthermore, that different ethnic minorities responded positively to the Games to different degrees.

3.2. Research on the Olympic Sport Participation Legacy at the Social Level

It is common to explore the utilisation and development of the Olympic sport participation legacy on a social level. The research articles found in this scoping review encompassed the impact of the Olympic sport participation legacy on community grassroots, non-host cities, specific sports, education, and public health.

Research on the impact of the Olympic Games on community grassroots sport participation has suggested that hosting the Olympic Games can promote urban regeneration, improve public activity resources, increase community residents’ sport participation, and improve public health [33,34]. However, there is insufficient evidence that community sport participation actually increased as a result of the Olympic Games. Furthermore, Feng and Hong’s [11] investigation actually found that the Olympics did not have a sustained positive impact on community grassroots sport participation and that community residents’ sport participation did not increase as a result of the Olympics. The inadequacy of sports facilities in communities also led to complaints from residents. Nevertheless, community grassroots are considered to be able to play an important role in the development of a legacy of Olympic sport participation [35,36].

The impact of the Olympics on sport participation in the host countries in general is a broader theme, with some studies breaking it down to the impact of the Olympics on sport participation in a city or examining the impact of the Olympic sport participation legacy in non-host cities [15,37]. Other studies have looked beyond the host country to examine the impact of the Olympic Games on sport participation in non-host countries. The starting point of research from this perspective is to explore the impact of the performance of participating Olympic athletes from non-host countries on their own country’s sport participation [38]. This perspective goes beyond previous research examining the impact of Olympic sport participation legacies within the host country context.

There is research suggesting that hosting the Olympic Games has a demonstration effect, which means that people are inspired to participate in sports while watching elite Olympic sporting performances [39]. The Olympics teach people the importance and significance of sports and encourage them to participate in physical activity. In addition, two articles have researched the impact of the Olympics on physical education in schools [40,41]. Kohe and Bowen-Jones [40] examined the perceptions of school students on physical education and sport participation in schools after the Olympics and received positive feedback. Similarly, Ribeiro et al. [41] examined the impact of the Olympics on the development of schoolteachers’ teaching skills, knowledge, and experiences, and the results demonstrated that teachers have an important role in the spread of Olympic physical education in schools. The educational support of schoolteachers is also important for the participation of students in sports in schools.

There is also research that has refined the development of the Olympic sport participation legacy to a specific sport. For example, Pappous and Hayday [42] conducted research on the impact of the London 2012 Olympic Games on sport participation in two sports in the UK: fencing and judo. The results found that there was an increase in overall sport participation in both sports. The researchers suggested that the successful promotion of individual sports such as these during the Olympics could attract more people to participate and increase sport participation at a grassroots level, leading to an overall increase in sport participation nationwide.

3.3. Research on the Olympic Sport Participation Legacy and the Intervention Process

The development and utilisation of the Olympic sport participation legacy requires the active intervention of relevant factors to be effective. Relevant research includes the intervention of the government in the Olympic sport participation legacy, the support of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to collaborate in the development of the Olympic sport participation legacy, the role of the media in promoting the development of the Olympic sport participation legacy, and research into the process of developing the utilisation of the Olympic sport participation legacy [13,16,17,19,43,44,45,46].

Other articles researching government interventions in the development and utilisation of Olympic sport participation legacies include Weed et al. [16], who argued that the government should promote the Olympics in the appropriate way to trigger the festival effect (i.e., to promote the Olympics as a national festival that goes beyond sport). Such an approach has the potential to promote popular sport participation, but there is no evidence to prove this yet. Furthermore, Kolotouchkina [44] evaluated the pre-event civic engagement strategy and framework for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, noting that the role of this strategy framework was to enable people to participate in the process of staging the Games, including making suggestions for the design of the Olympic medals and voting for the Olympic mascot. Such an approach similarly promotes the Olympic Games as a national festival that can lead to greater Olympic knowledge and experience for citizens and can help to increase civic participation in sports in the future.

Government policy planning also has an important influence on the development of the Olympic sport participation legacy. Bretherton et al. [47] reflected on the failure of the pre-London 2012 sports policy objective (to increase overall sports participation by 2 million people between 2008 and 2012). They argued that host governments cannot rely only on the unique status and influence of the Olympics to help increase sport participation. They should offer more active policy support as well as greater control of the external environment. On this point, Gérard et al. [48] explored the impact of the UK’s austerity policies (welfare cuts and reduced local government funding) on grassroots clubs and organisations, leading to a reduction in their ability to provide sporting services to residents and negatively affecting their sporting participation. This is contradictory to the policy of encouraging sport participation. It also shows that the government should not only encourage sport participation but also create a favourable social environment for residents’ sport participation [49]. Moreover, the lack of a clear plan for the long-term use of Olympic venues is not conducive to the sustainability of the Olympic sport participation legacy [50].

The role of the media and NGOs in the development of Olympic sport participation legacies is important, and research advocates that there should be coordination between them and governments. Indeed, Kidd [51] suggested that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) should do more to institutionalise and strengthen legacy planning management (e.g., by providing more help to host governments in legacy management). The media promotion during the Olympic Games helps to increase interest in the Games, leading to increased enthusiasm and a positive impact on people’s motivation to participate in sports. However, how to translate motivation into actual sport participation remains to be studied [17,52]. In the development of theories for studying the Olympic sport participation legacy, the “festival effect” (i.e., developing the Olympics as a national festival that drives sport participation) and the “trickle-down effect” (or “demonstration effect”, referring to the process of motivating people to participate in sports through the influence of elite athletes or sporting events) have often been used [8,13,27,43,53]. However, there is little evidence to support the existence of these effects in the current studies, and claims remain speculative.

4. Discussion

This scoping review provides a review of the research on the sustainability of Olympic sport participation legacies. Based on the results in this review, it can be seen that the boom in researching Olympic sport participation legacies began with the London 2012 Olympic Games, and sport participation itself has also gained much attention as an element of the Olympic legacy since the London Games. The reason for this is speculated in this paper to be inspired by the goals of the London 2012 Olympic Games, which were the first in history to claim to encourage sport participation for all by hosting the Games [5,6,7]. This review will now discuss the main findings of the literature analysis of Olympic sport participation legacies based on the PAGER framework (Table 3), which includes model themes, research progress, research gaps, evidence of practice, and research recommendations.

Table 3.

Results of the PAGER analysis of the Olympic sport participation legacy research.

Five themes are summarised for discussion in this paper from the three sections of the results: (1) the impact of the Paralympic Games on disabled people’s sport participation, (2) the reaction of general families to Olympic sport participation legacies, (3) the role of community grassroots organisations in delivering Olympic sport participation legacies, (4) the impact of the Olympic Games on sport participation in non-host regions, and (5) government policies and the development of Olympic sport participation legacies.

4.1. The Impact of the Paralympic Games on Disabled People’s Sport Participation

The Paralympic Games, as an important part of the Olympic movement, play an important role in promoting sport participation. Whether as an elite sporting event or as a specific sporting performance, the Paralympic Games are important in constructing the meaning of disability and sport in society [54]. There has been extensive academic research on Olympic sport participation focusing on the Summer Games, followed by the Winter Games and then the Paralympic Games. This research weighting can also be reflected in social attention to the Olympic Games competition. Media coverage is an important channel for societal attention to the Olympic Games, and elite athletes in the Paralympic Games have less exposure in the media compared with the non-disabled Games [55]. However, this does not mean that the Paralympic Games are unimportant; on the contrary, they can have a significant impact on disabled people’s participation in sports. Sports can be a catalyst for social development, and this is especially true of disability sports. The Paralympic Games have transformed the status of disabled people from patients to athletes and are a way for disabled people to receive more social attention and recognition [56]. This is an incentive for disabled people to participate in sports. Current research points to the Paralympic Games as a driving force in encouraging the participation of people with disabilities in sports. Olympism is about the harmonious development of human society, and the Paralympic Games are the ideal vehicle for the integration of disabled people into society by way of sport [29]. However, there are two sides to this ideal vehicle. If the Paralympic Games fail to achieve a coordinated functioning of sport and politics and are used as a political tool to promote social equality, they can have a negative effect on the attitudes of disabled people towards sports in society [57]. More disabled people should be called upon to represent disabled people’s sport organisations, to be a voice for disabled people, and to fight for more power and benefits [28]. This is a reasonable hypothetical suggestion for promoting disabled people’s participation in sports based on a status quo analysis, as disabled people are more aware of the needs of disabled people. If the Paralympic Games are to be a tool to increase the participation of disabled people in sports, it is necessary to place disabled people in a key position in the decision-making process of sports. Due to the current paucity of empirical research on the Paralympic Games increasing participation in sports for disabled people, it cannot provide sufficient evidence for practice. In future research, data on the impact of other Paralympic Games iterations on the sport participation of disabled people should be collected, and qualitative and quantitative research should be conducted to provide more evidence about the development of the Paralympic sport participation legacy.

4.2. The Reaction of Ordinary Families to the Olympic Sport Participation Legacy

Studying whether the attitudes and perceptions of the ordinary families in the host country towards the Olympics affect their future sport participation is a direction where more research could be conducted. Some studies have shown that the attitudes of ordinary families towards the Olympic Games affect their motivation to participate in sports in the future. The ordinary family can feel enthusiastic for their country’s athletes’ exciting performances, which can have a positive impact on their motivation to participate in sports in daily life. However, not all family members are inspired, and this seems to be related to the ages and personal lifestyles of the family members [7]. Moreover, it is still uncertain whether the ordinary families inspired to participate in sports would actually increase their sport participation. The idea of placing an ordinary family as the central lever connecting the sport participation legacy has yet to be proven by sufficient evidence [30]. Even if the attitudes of ordinary families towards the Games are positive and they want to participate in sports, there is still other resistance in the process. A large distance remains between the government’s sports development policy and the ordinary family. It is difficult for ordinary families to enjoy the benefits that hosting the Games brings, as there seems to be no other activity to participate in but watching the Olympic games at home with media coverage. The government has not adequately managed the relationship between delivering the benefits that elite sports bring and promoting public sport participation [31]. The government should recognise the diversity of the sporting needs of ordinary families when formulating community sport development policies. Ordinary families should also be given the opportunity to participate in the design and decision-making process of local government sports infrastructure plans [30]. Currently, most research is stuck at the stage of observing the phenomenon, and research on measures to address this issue is scarce. A further point is that according to the review, articles related to ordinary families and the Olympic sport participation legacy were found to be set in the context of the London 2012 Olympic Games, while the sport participation of ordinary families in other Olympic Games had not been investigated. Therefore, practical evidence on how to effectively promote ordinary family sport participation through the Olympics needs to be complemented. In future research, researchers should initiate qualitative research related to ordinary families and Olympic sport participation legacies for other Olympic Games locations aside from the London 2012 Olympics. Video diaries can be used as a qualitative research method for sport studies through visual engagement, which can provide further insight into people’s interactions with the Olympics and the impact on their daily lives [7,58]. The range of research includes the feasibility of the ordinary family as a lever for public sport participation delivery, the rationale for government public sport policies to respond to the sporting needs of ordinary families, and the impact of the Olympics on ordinary family sport participation from a managerial perspective.

4.3. The Role of Community Sport Organisations in Delivering the Olympic Sport Participation Legacy

The review found that community sport organisations have an important role to play in delivering the Olympic sport participation legacy. Top-down sport promotion policies cannot sustain community residents’ sport participation in the long term [59]. The maintenance of community participation in sports needs to be community-driven, with people in the community choosing more appropriate sports based on their needs and getting more people involved [35]. This community self-driven model of community sport organisation is a hypothesis for future improvements in community residents’ sport participation and is a response to the failure of traditional government sport incentives to effectively increase residents’ sport participation. It also highlights the significance of community sport organisations in delivering the Olympic sport participation legacy. Furthermore, the ability of community sport organisations to provide adequate sport services for residents can have a direct impact on their actual sport participation. “Sports facilities resources were poorly distributed and in some areas there were not enough sports facilities for residents to use; not everyone had the opportunity to participate in the sports activities organised by the community, some were just for show.” These issues add barriers to residents’ participation in sports [11]. The quality of the public physical activity resources in a community is directly proportional to the level of sport participation of local community residents [33]. It is clear that strengthening the capacity of grassroots community organisations can help promote residents’ sport participation. Mutually, the level of sport participation of community residents can influence their support for future sport events [34]. The residents’ level of sport participation can be reflected in their interest and identification with sports [60]. Current research has recognised the role of grassroots community organisations in achieving sustainable Olympic sport participation legacies, and community residents’ perceptions of sport participation could impact their support for future sporting events. Practical recommendations for improving sport participation between community sport organisations and community residents were proposed, such as using community sport participation as a long-term development strategy, promoting sport and culture communication, and volunteering participation among community residents to build a sustainable sport participation legacy, as well as meeting the sporting needs of communities through strategic alliances between community sport organisations, sponsors, and other stakeholders [34]. Future research could focus on the demographic differences in community sport organisations, such as the physical activity in older communities being different from the physical activity in younger communities. Qualitative research to analyse how sport participation activities are developed in different communities should be conducted.

4.4. The Impact of the Olympic Games on Sport Participation in Non-Host Regions

Although the literature on the Olympic sport participation legacy has grown in recent years, most of it has focused on the context of the host country or city, and few studies have looked at the impact of the Games in non-host regions or how sport participation in these regions changes before and after the Games [15,37,38]. The Olympic Games is a global sporting event, and its impact extends beyond the region in which it is held. Non-host regions can include both non-host cities in the host country and non-host countries [15,61,62,63]. A survey of community perceptions found that the 2002 Winter Olympics did not have much impact on non-host communities, but there was a willingness among residents to support community activity participation [64]. Similarly, during the London 2012 Games, residents of non-London communities were willing to participate in local Olympics-related activities but were concerned about the resulting traffic problems and price rises [61]. There is also evidence that community sports organisations in non-host cities have attempted to provide recreational sports services to community residents but have been constrained by government funding and policies in trying to achieve this [15]. Given the positive perception of the Olympics by residents and sports organisations in non-host city communities, there is a need to consider how these positive perceptions can be transformed into actual increases in sport participation. Some studies have examined the activity leverage of non-host city communities in the transformation of Olympic impact, proposing that governments and stakeholders in non-host cities should build early leadership and strategic alliances prior to the Olympics to promote residents’ interest in sports and increase local sports activities, thereby effectively activating the activity leverage [37,63]. In addition, research on the impact of the Olympic Games in non-host countries is much less common than that on the impact of the Games in non-host cities in host countries. A survey of leisure-time physical activity among the youths in the hometowns (in Canada) of Canadian athletes who participated in the London 2012 Olympic Games found that Canadian athletes winning medals was positively associated with leisure-time physical activity among the youths in their hometowns [38]. This provides some evidence for the possibility of a trickle-down effect of the Olympics in non-host countries. For now, however, there is a lack of practical evidence on leveraging the Games to develop local sports in non-host regions (i.e., non-host cities in host countries and non-host countries). Future research should focus on how to deliver the impact of the Olympic Games in non-host cities in host countries to increase actual sport participation, adding more research evidence that the Olympic Games has an impact on sport participation in non-host countries.

4.5. Government Policies and the Development of the Olympic Sport Participation Legacy

Finally, the review found that government intervention has a significant impact on the implementation and sustainability of the Olympic sport participation legacy. Government intervention can be mainly reflected in the influence of government policies on the development and utilisation of the Olympic legacy [4,8,44,65]. Moreover, not only policies directly related to the Olympic legacy but also social, economic, and culturally related policies can have an impact on the development of the Olympic legacy [48,49]. Social, economic, and cultural changes resulting from government policies can also affect the sustainable development and utilisation of the Olympic legacy. The 2010 austerity policies in the UK (significant cuts to welfare budgets, increases in value-added tax, and reductions in spending across all sectors of society) led to a shift in the market logic at a societal level, which in turn affected the mechanisms for the delivery of sport and leisure services by grassroots sports clubs in the UK. This series of effects has hindered the development of sport participation after the London 2012 Olympic Games [48]. Government austerity policies are at odds with the goal of increasing national sport participation through hosting the Olympics. This is also the case with the UK government’s risk management policy, where excessive risk management based on the protection of the physical and mental health of minors has led to a culture of risk discourse in society, particularly in sports, causing a moral panic among the public about participation in sports. Under the influence of such a discursive culture, the transmission of the Olympic spirit is greatly hindered, and people are less enthusiastic about participating in sports [49]. In a similar dimension, the role of the government through policy in the sociocultural sphere of Olympic education (Olympism education structures and educational programmes) can also influence the public’s sport participation [66].

There is a number of studies on how governments can properly guide the development of the Olympic legacy through policies to create a friendly environment for sport participation. Several aspects are mentioned in this literature. First, governments need to draw up long-term plans, including the pre-, mid-, and post-Olympic periods, to consider the impact of the internal and external environment on legacy development and to prepare adequately for the development of the Olympic Games’ sport participation legacy [3,44,47]. Secondly, governments need to coordinate the interests between Olympic stakeholders and cooperate adequately in areas such as the use of sports facilities and activities that encourage public participation in sports [4,46,50]. Third, in order to effectively maximise the positive effects of the Olympics on sport participation, policies at all levels of government need to be coherent and utilise policy tools to effectively satisfy people’s sporting demands [65]. These points are derived by analysing the reasons why governments have failed to promote the growth of sport participation following hosting the Olympic Games, yet a lack of sufficient empirical evidence of the viability of these recommendations remains. The quadrennial nature of hosting the Olympic Games also makes empirical research on the Olympic sport participation legacy a long-term process.

The “trickle-down effect” and the “festival effect” have emerged frequently in studies examining the impact of government intervention on the Olympic sport participation legacy [8,16,53]. However, empirical evidence on these two theories is not sufficient. The selection and collection of research data are still flawed, and there is a need for the government to create relevant databases to assist researchers in conducting research [2,18,67].

Future research could expand the dimensions of research on the impact of government intervention on the Olympic legacy. The aforementioned social, economic, and cultural impacts of government policies can have an indirect effect on the development of the Olympic legacy. In addition, the policy descriptions of sport participation in the bidding documents of individual governments in countries bidding for future Olympic Games could be considered.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review examined a total of 54 articles dealing with the Olympic sport participation legacy. The 54 articles were divided into 3 broad sections, including the population dimension, the social dimension, and the intervention process. Five major research themes were summarised from these three broad sections through the PAGER framework.

The first was research related to the impact of the Paralympic Games on the sport participation of disabled people. The Paralympic Games are an important part of the Olympic Games, and disabled people constitute an important group in society as well. In the Olympic spirit preached by the IOC, the Paralympic Games have the goal of encouraging and promoting the sport participation of disabled people. However, there is a low level of interest in the Paralympic Games in society, and the public is not aware of the Paralympic spirit. Misuse of the influence of the Paralympic Games can also lead to a rejection of the Paralympic Games by the disabled population, which in turn could reduce disabled people’s sport participation.

Secondly, there are the attitudes of ordinary families towards the Olympic sport participation legacy. The ordinary family is an important unit of society and is also crucial to the implementation of the Olympic sport participation legacy. Several relevant pieces in the literature are qualitative studies of the attitudes and perceptions of ordinary families regarding the Olympic Games, and the video diary method is widely used. Within these studies, it is shown that family members of different ages have different attitudes towards the Olympic Games, and they are inspired by the Olympics to different degrees. Moreover, these studies show that the ordinary family has the desire to increase their sport participation, but the actual sport participation is still unknown.

Third, the role of community sports organisations is important in delivering the Olympic sport participation legacy. Community sports organisations can be described as a bridge between the government and community residents. Community residents generally have little direct access to the government, and government policies and intentions related to promoting sport participation need to be ultimately achieved through community sport organisations. The ability of community sports organisations to provide sports and leisure services largely determines the level of sport participation of community residents.

Fourth, there is the impact of the Olympic sport participation legacy in non-host regions. The Olympic Games are an international sporting event with a large scope of influence. Whether non-host regions would be inspired by the Olympics to increase their sport participation requires further investigation. In addition, this review found that non-hosting regions can be divided into two types—non-host cities in the host country and non-host countries—which shows the wide geographical scope of the study. One of the aims of the Olympic Charter and the IOC is to stimulate increased sport participation worldwide through the Olympic Games. Research on non-hosting regions also caters to the development of Olympic sports.

Finally, there is the impact of government intervention on the legacy of Olympic sport participation. Numerous related studies were found in this review, and the dimension of the research extends from the study of government-related sport policies to the impact of social, economic, and cultural policies on the Olympic sport participation legacy. The “trickle-down effect” and “festival effect” theories are often used in research. The importance of relevant official databases has also been mentioned many times, as some studies lack complete data in the research process.

The current research found in this scoping review is more focused on the phenomenological descriptions and recommendations for future planning of Olympic sport participation legacies, for which considerable progress has been made. However, the process of collecting empirical evidence on the successful use of Olympic sport participation legacies to achieve increased sport participation is still in a lagging phase.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, and visualisation, P.S.; review and editing and supervision, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- International Olympic Committee. Olympic Charter: In Force as from 17 July 2020/International Olympic Committee. 2020. Available online: https://library.olympics.com/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/355508/olympic-charter-in-force-as-from-17-july-2020-international-olympic-committee?_lg=en-GB (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Veal, A.J.; Toohey, K.; Frawley, S. The sport participation legacy of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games and other international sporting events hosted in Australia. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2012, 4, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.C.; de Sousa-Mast, F.R.; Gurgel, L.A. Rio 2016 and the sport participation legacies. Leis. Stud. 2014, 33, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.C.; Frawley, S.; Hodgetts, D.; Thomson, A.; Hughes, K. Sport participation legacy and the Olympic games: The case of Sydney 2000, London 2012, and Rio 2016. Event Manag. 2017, 21, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Culture Media and Sport. London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games Impacts and Legacy Evaluation Framework; DCMS: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weed, M. London 2012 legacy strategy: Ambitions, promises and implementation plans. In Handbook of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games; Girginov, V., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Darko, N.; Mackintosh, C. ‘Don’t you feel bad watching the Olympics, watching us?’ A qualitative analysis of London 2012 Olympics influence on family sports participation and physical activity. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2016, 8, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M.; Coren, E.; Fiore, J.; Wellard, I.; Chatziefstathiou, D.; Mansfield, L.; Dowse, S. The Olympic Games and raising sport participation: A systematic review of evidence and an interrogation of policy for a demonstration effect. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayday, E.J.; Pappous, A.; Koutrou, N. The role of voluntary sport organisations in leveraging the London 2012 sport participation legacy. Leis. Stud. 2019, 38, 746–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Sports of China. 2022 Beijing Press Centre Press Conference ‘Beijing Winter Olympic Games to Drive 300 Million People to Participate in Snow and Ice Sports Special Session’. 2022. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n315/n20067425/c24084697/content.html (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Feng, J.; Hong, F. The legacy: Did the Beijing Olympic Games have a long-term impact on grassroots sport participation in Chinese townships? Int. J. Hist. Sport 2013, 30, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Bellew, B.; Craig, C.L. Did the 2000 Sydney Olympics increase physical activity among adult Australians? Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.V.; Lorenc, T. A qualitative study into the development of a physical activity legacy from the London 2012 Olympic Games. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, K.; Wu, J.; Inoue, Y.; Sato, M. Long-term impact of the Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games on sport participation: A cohort analysis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, E.; Bloyce, D.; Smith, A. Delivering a sports participation legacy from the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Evidence from sport development workers in Birmingham and their experiences of a double-bind. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M.; Coren, E.; Fiore, J.; Wellard, I.; Mansfield, L.; Chatziefstathiou, D.; Dowse, S. Developing a physical activity legacy from the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: A policy-led systematic review. Perspect. Public Health 2012, 132, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boardley, I.D. Can viewing London 2012 influence sport participation?—A viewpoint based on relevant theory. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2013, 5, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayday, E.J.; Pappous, A.; Koutrou, N. Leveraging the sport participation legacy of the London 2012 Olympics: Senior managers’ perceptions. Int. J. Sport Policy 2017, 9, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.J.; Darcy, S.; Walker, C. A case of leveraging a mega-sport event for a sport participation and sport tourism legacy: A prospective longitudinal case study of whistler adaptive sports. Sustainability 2020, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Neto, V. Beijing: The World’s First Dual Olympic City. Olympics. 2021. Available online: https://olympics.com/en/news/100-days-to-go-beijing-worlds-first-dual-olympic-city (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Teare, G.; Taks, M. Extending the scoping review framework: A guide for interdisciplinary researchers. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2020, 23, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Aveyard, H.; Herber, O.R.; Isham, L.; Taylor, J.; O’Malley, L. Scoping reviews: The PAGER framework for improving the quality of reporting. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokolakakis, T.; Lera-López, F.; Ramchandani, G. Did London 2012 deliver a sports participation legacy? Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Bauman, A.E. The impact of the Vancouver Winter Olympics on population level physical activity and sport participation among Canadian children and adolescents: Population based study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potwarka, L.R.; Leatherdale, S.T. The Vancouver 2010 Olympics and leisure-time physical activity rates among youth in Canada: Any evidence of a trickle-down effect? Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Pappous, A. “The Legacy Element... It Just Felt More Woolly”: Exploring the Reasons for the Decline in People With Disabilities’ Sport Participation in England 5 Years After the London 2012 Paralympic Games. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2018, 42, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, P.D.; Silva, C.F. The fiddle of using the Paralympic Games as a vehicle for expanding [dis] ability sport participation. Sport Soc. 2018, 21, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, C.; Darko, N.; Rutherford, Z.; Wilkins, H.M. A qualitative study of the impact of the London 2012 Olympics on families in the East Midlands of England: Lessons for sports development policy and practice. Sport Educ. Soc. 2015, 20, 1065–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, C.; Darko, N.; May-Wilkins, H. Unintended outcomes of the London 2012 Olympic Games: Local voices of resistance and the challenge for sport participation leverage in England. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokolakakis, T.; Lera-López, F. Sport legacy impact on ethnic minority groups: The case of London 2012. Sport Soc. 2021, 25, 730–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa-Mast, F.R.; Reis, A.C.; Vieira, M.C.; Sperandei, S.; Gurgel, L.A.; Pühse, U. Does being an Olympic city help improve recreational resources? Examining the quality of physical activity resources in a low-income neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, T.; Calapez, A.; Cunha de Almeida, V.M. Does the Olympic legacy and sport participation influence resident support for future events? Leis. Stud. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, T. ‘Grow and sustain’: The role of community sports provision in promoting a participation legacy for the 2012 Olympic Games. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2010, 2, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, E.H. Delivering sports participation legacies at the grassroots level: The voluntary sports clubs of Glasgow 2014. J. Sport Manag. 2017, 31, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Henry, I. Evaluating the London 2012 Games’ impact on sport participation in a non-hosting region: A practical application of realist evaluation. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potwarka, L.; Ramchandani, G.; Castellanos-García, P.; Kokolakakis, T.; Teare, G.; Jiang, K. Beyond the host nation: An investigation of trickle-down effects in the ‘Hometowns’ of Canadian athletes who competed at the London 2012 Olympic Games. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegman, O. Educational Olympic Challenge: The Legacy of Public Sport Participation. In European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences; Chis, V., Albulescu, I., Eds.; Future Academy: Bankstown, Australia, 2016; Volume 18, pp. 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohe, G.Z.; Bowen-Jones, W. Rhetoric and realities of London 2012 Olympic education and participation ‘legacies’: Voices from the core and periphery. Sport Educ. Soc. 2016, 21, 1213–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ribeiro, T.; Correia, A.; Figueiredo, C.; Biscaia, R. The Olympic Games’ impact on the development of teachers: The case of Rio 2016 Official Olympic Education Programme. Educ. Rev. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappous, A.; Hayday, E.J. A case study investigating the impact of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games on participation in two non-traditional English sports, Judo and Fencing. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 668–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girginov, V.; Hills, L. A Sustainable Sports Legacy: Creating a Link between the London Olympics and Sports Participation. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2008, 25, 2091–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolotouchkina, O. Engaging citizens in sports mega-events: The participatory strategic approach of Tokyo 2020 Olympic. Commun. Soc. 2018, 31, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.; Leopkey, B. Exploring Issues within Post-Olympic Games Legacy Governance: The Case of the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympic Games. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhagen, S.E. Leveraging sporting events to create sport participation: A case study of the 2016 Youth Olympic Games. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2021, 13, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, P.; Piggin, J.; Bodet, G. Olympic sport and physical activity promotion: The rise and fall of the London 2012 pre-event mass participation ‘legacy’. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2016, 8, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérard, S.; Brittain, I.; Jones, A.; Thomas, G. The impact of austerity on the London 2012 Summer Olympics participation legacy from a grassroots sports club perspective: An institutional logics approach. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, H.; Garratt, D. Olympic dreams and social realities: A Foucauldian analysis of legacy and mass participation. Sociol. Res. Online 2013, 18, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Grix, J. Implementing a Sustainability Legacy Strategy: A Case Study of PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympic Games. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, B. The global sporting legacy of the Olympic Movement. Sport Soc. 2013, 16, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Kamada, M.; Reis, R.S.; Troiano, R.P.; Ding, D.; Milton, K.; Murphy, N.; Hallal, P.C. An evidence-based assessment of the impact of the Olympic Games on population levels of physical activity. Lancet 2021, 398, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perks, T. Exploring an Olympic “Legacy”: Sport Participation in Canada before and after the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics. Can. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 52, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdue, D.E.; Howe, P.D. See the sport, not the disability: Exploring the Paralympic paradox. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2012, 4, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, L.; Robinson, P.; Shields, N. Media portrayal of elite athletes with disability–a systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, D.; Steadward, R. The Paralympic Games and 60 years of change (1948–2008): Unification and restructuring from a disability and medical model to sport-based competition. In Disability in the Global Sport Arena; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Braye, S.; Dixon, K.; Gibbons, T. A mockery of equality’: An exploratory investigation into disabled activists’ views of the Paralympic Games. Disabil. Soc. 2013, 28, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.L.; Fonseca, J.; De Martin Silva, L.; Davies, G.; Morgan, K.; Mesquita, I. The promise and problems of video diaries: Building on current research. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2015, 7, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vail, S.E. Community development and sport participation. J. Sport Manag. 2007, 21, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kaplanidou, K. The effect of sport involvement on support for mega sport events: Why does it matter. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Shipway, R.; Cleeve, B. Resident perceptions of mega-sporting events: A non-host city perspective of the 2012 London Olympic Games. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadakis, K.; Kaplanidou, K. Legacy perceptions among host and non-host Olympic Games residents: A longitudinal study of the 2010 Vancouver Olympic Games. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Misener, L. Event leveraging in a nonhost region: Challenges and opportunities. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deccio, C.; Baloglu, S. Nonhost community resident reactions to the 2002 Winter Olympics: The spillover impacts. J. Travel Res. 2002, 41, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derom, I.; Lee, D. Vancouver and the 2010 Olympic Games: Physical activity for all? J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Pereira, E.; Mascarenhas, M. Educational dimension of olympism: A systematic literature review. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2020, 42, 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, F.; Grix, J.; Marqués, D.P. The Olympic legacy and participation in sport: An interim assessment of Sport England’s Active People Survey for sports studies research. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2013, 5, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).