Abstract

Competition to ensure sustainable conditions for graduates’ knowledge, skills, and competencies (KSC) and employability for sustainable development of human resources has long been present in higher education institutions (HEIs). The purpose of this study is to examine the roles of educational processes, practical activities, and research activities as key determinants to predict KSC and employability in the context of medical education in Indonesian HEIs. Moreover, this study also reports the role of facilities in predicting educational processes, practical activities, and research activities. This survey study obtained data from 1086 respondents, who are students of two medical schools. The data were analyzed by assessing the measurement and structural model in the partial least square structural equation model (PLS-SEM). Overall, all hypotheses were supported; the strongest relationship emerged between facilities and research activities, while the lowest relationship was present between practical activities and employability. From a theoretical perspective, the findings offer a conceptual framework related to HEIs’ quality management factors. Highlighting the significant relationships, appropriate policies can be produced for more quality institutions in improving graduates’ KSC and employability for the labor market.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, stakeholders of higher education institutions (HEIs) should commit to making sustainable improvements for their graduates’ knowledge, skills, and competencies (KSC) and employability [1] as Rieckmann [2] addressed HEIs’ outstanding contribution in developing human societies for sustainable development. Increased enrollment in HEIs also resulted in a higher number of graduates that would result in competitiveness in job vacancy that is eventually related to employability. Students, including those who are in medical education, should build their KSC and employability rate to solve sustainability issues in the surrounding world. KSC is essential for students to measure their future careers’ performances or employability as part of HEIs quality assurance [3]. Two main issues regarding this assurance are: (1) the communication between the institution and students about KSC they should achieve and (2) how to comprehend using KSC for their future occupation or employability. The employability term has been an object of discussion for a long time among HEIs stakeholders. Particularly, it is claimed that if graduates do not possess the SKC required by end-users, employability becomes an issue. The employability rate can be represented in the trend of unemployment. Among the contributing factors are educational processes, practical activities, and research activities. Thus, it is important to identify factors affecting both KSC and employability.

The identification is important for sustainable education development in the future. Studies about students’ perceptions regarding KSC and employability have been previously conducted and reported [4,5,6,7]. However, limited studies are available in the context of HEIs (medical education) in developing countries. Therefore, the main purpose of the current study is to investigate factors affecting (1) KSC and (2) employability among medical students of Indonesian HEIs. Specifically, we attributed three research objectives; (1) to elaborate the influence of the educational processes, facilities, research activities, and practical activities towards knowledge, skills, and competencies, (2) to highlight the impact of the educational processes, facilities, research activities, and practical activities towards employability, and (3) to report the role of facilities in predicting educational processes, practical activities, and research activities. Theoretically, the study’s findings provide a framework that can guide future researchers interested in doing a study, especially for those who intend to conduct studies in developing countries. For the significant relationships resulted from the data computation, medical education stakeholders can produce appropriate policies supporting their graduates’ KSC and employability.

2. Review of Literature

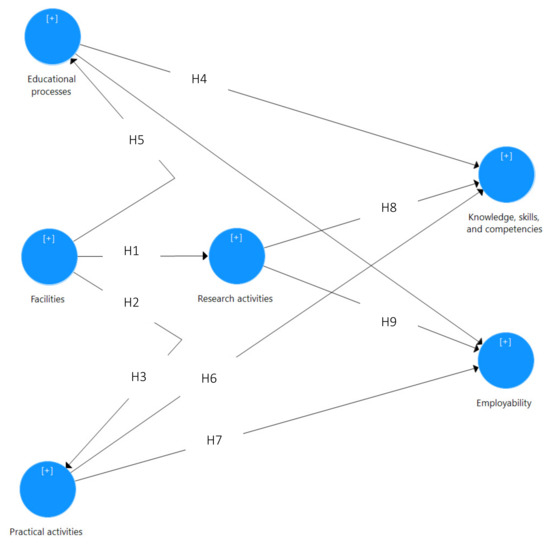

Prior studies have reported topics on KSC and employability in education. Nicolescu and Nicolescu [7] applied path analysis to build a framework for students in business schools through skills in line with employability. The findings of their study inform four categories of skills that were hypothesized on employability confidence. The exogenous factors represent qualities, transferable social skills, professional and job-seeking skills that significantly influence students’ employability confidence. Meanwhile, corporate-related and individual transferable skills were not significant predictors for employability [7]. Lambrechts and Van Petegem [4] reported the significant predicting power of sustainable development competencies on skill in conducting research. Their results illustrated that competencies in research have a substantial contribution to the achievement of sustainable development competencies. Meanwhile, Gora et al. [6] reported a direct and indirect effect of infrastructures and supporting equipment, educational processes, practical and research activities toward KSC and employability in Romania. In this study. We included six variables: facilities, educational processes, practical activities, research activities, KSC, and employability. From these six variables, nine hypotheses were proposed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A proposed model exploring Indonesian medical education students’ knowledge, skills and competencies (KSC) and employability.

2.1. Facilities

Buildings, technology-based classrooms, laboratories, and other equipment are essential for teaching and learning processes, practical activities, and research activities [8]. There is a strong report that high-quality equipment provides more appropriate didactic activities that foster outcomes resulting from teaching and learning and decreases dropout rates [9,10]. In Indonesia, facilitating conditions or facilities in HEIs are still the main challenge; the inequality development between educational institutions in rural and urban areas still exists [11]. This condition results in gaps among students’ KSC and impacts job acceptance [12,13]. In a specific way, the infrastructures have a key role in deepening students’ KSC, especially for the specialization field, including in medical education. The availability and appropriateness of facilities allow students to have good competencies and learn skills to make a better opportunity for future careers as medical workers. Similarly, facilities are expected to have a strong bond with KSC and employability [6,12,13]. Within the current study context, educational processes, practical activities, and research activities were hypothesized to be affected by facilities,

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Facilities will positively influence educational processes.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Facilities will positively influence practical activities.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Facilities will positively influence research activities.

2.2. Educational Processes

Educational processes were included to predict Indonesian medical students’ KSC and employability. Educational processes have been reported to have an essential role in improving HEIs quality [14,15,16,17]. Higher education policymakers should plan and set their policies based on evaluating educational processes; the policies include the curricula, program designs, and plans. Educational processes refer to the quality of the content, teaching staff, and teaching activities. Since HEIs systems are pushed to improve education effectiveness in various approaches, instructional processes’ quality should be more concerned [17].

All parties in education, such as faculty members, teachers, administration staff, and educational policymakers, should attempt to produce quality cultures in HEIs to achieve accreditation and evaluation from external boards. It is to invite more students to enter the institutions and excellent graduates for broad employments. Some steps should be addressed to maintain and improve the content of the educational processes [6]. Among others are restructuring study disciplines and the suitability between activities inside or outside the classroom. It aims to match future participation in producing students with good KSC and satisfactory rate of employment [14,15,16]. Within the system, the educational processes should be sustainable [18]. Therefore, HEIs should continually examine the demands of future jobs. In the medical field, the markets have been widely recognized, such as hospitals and pharmaceutical companies. Moreover, the opportunities achieved by the graduates to continue their studies should also be considered. Learning from the reports [6,14,19], the current study proposes two hypotheses,

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Educational processes will positively influence KSC.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Educational processes will positively influence employability.

2.3. Practical Activities

Various emergences of job demands push people for novel KSC demands [5,6] Graduates’ KSC would be enhanced if the correlation between the knowledge they obtain in HEIs and the KSC they achieved from practical activities could support them in preparing for a job opportunity [6,20]. When practical activities are the main focus, an essential role in shaping students’ KSC will be addressed [6,20]. Higher education should be able to facilitate teachers to integrate lectures and practical activities that aim at designing the development stimulation of KSC. The demand for specialized competencies and skills regarding practical activities is now rising, causing the competitiveness in a labor market that relates to employability rates [5,21]. Prior studies have reported their effort in statistically computing the predictive power of practical activities on KSC or/and employability [5,6,22]. For example, Gora et al. [6] reported the significant relationship between practical activities and KSC while failed to prove a substantial relationship between practical activities and employability. Based on the importance of practical activities for HEIs KSC and employability, two research hypotheses are proposed,

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Practical activities will positively influence KSC.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Practical activities will positively influence employability.

2.4. Research Activities

Research activities, defined as a learning process for scientific knowledge, need a critical thinking process. The activities establish means and methods aiming to improve cognitive skills, perception, creativity, skills, and abilities that could be an important factor to improve the rate of employability. Lambrechts and Van Petegem [4] informed that research competencies are elaborated in various approaches depending on specific purposes or disciplines. Higher education should integrate research activities to have an essential role in the instruction. Similarly, research learning in HEIs classrooms has been perceived as a necessary approach for an in-depth learning process and an instrumental tool for competencies-based learning [23,24]. In brief, one of the challenges is the conceptualization of the research function as part of research activities to improve students’ KSC and employability in producing quality graduates [23,24]. Regarding the importance of the research activities, two hypotheses regarding research activities were proposed,

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Research activities will positively influence knowledge, skills, and competencies.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Research activities will positively influence employability.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design of the Study

This survey study aims at reporting findings on the strength of quality assurance in medical education. The study included two primary endogenous constructs, namely (1) KSC and (2) employability. The proposed model shown in Figure 1 consists of six constructs, namely educational process, facilities, practical activities, research activities, KSC, and employability. Nine path lines were proposed for the six constructs; three path lines were proposed for facilities, hypothesized to significantly predict three constructs (educational process, practical activities, and research activities). Meanwhile, KSC and employability were proposed to be predicted by educational process, practical activities, and research activities (Figure 1). The study implemented a cross-sectional survey design [25,26,27]. This design is described as quantitative research procedures, providing a survey administration to samples or the whole population. It is to elaborate attitudes, opinions, or behaviors.

3.2. Instrumentation

A survey instrument was implemented to confirm research purposes through an in-depth analysis of previous literature [28]. There were six constructs with forty-nine indicators, as shown in Table 1. The educational process was proposed with the establishment of 17 indicators [6,29,30]. Seven indicators for facilities and practical activities, respectively, were adapted from prior related studies [5,6,20,29]. Besides, research activities (9 indicators), employability (3 indicators), and KSC (6 indicators) were initiated [6,7,14,19,31,32,33,34]. The survey instrument is a 5-point Likert scale. We protected the participants’ confidentiality by not adding specific personal information that can harm them, such as names, emails, and addresses. Before distributing the questionnaire to the participants, we examined the instrument through discussion with educational policy experts. We invited ten experts; however, five agreed and discussed the instruments in two focus group discussions. Through these discussions, some indicators were revised, and some others were removed. The final decision to change and remove the indicators was based on an in-depth argumentation among the parties, researchers, and experts. The removed indicators were EP6, EP16, and Fc7. Finally, the instrument’s distribution was conducted with forty-six indicators remained for the main data collection.

Table 1.

Initial constructs, indicators, and sources.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

As this study explores factors that influence medical education students’ perceived KSC and employability, we distributed the instrument to two Indonesian medical schools (Institution A and Institution B). The two universities were selected due to the reason of feasibility. The sampling was taken based on *G power application [35]. With nine path arrows, the current study requires more than 108 samples. Due to the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), the study instrument was made in Google Form and shared through email and social media. As a result, 1108 responses were gathered; 1086 data were measurable and included to analyze the study, exceeding the minimum number of samples required. Three hundred and sixty-four respondents were from Institution B, while 722 were respondents from institution A. Only two hundred and thirty-eight respondents are males; the other 848 respondents are females. Seventy-seven of the respondents were in the first year, 379 respondents in the second year, 275 in the third year, and 355 in the fourth year or above.

For data analysis, partial least square-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) procedures were implemented. In this study, the SmartPLS 3.2 (SmartPLS GMBH, Bönningstedt, Germany) application was utilized for assessing measurement and structural models. The data validity and reliability were measured during their computation in the measurement model. To examine the validity of the data, we reported convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was reported through average variance extraction (AVE), which value should be ≥0.500; discriminant validity was addressed based on the computation processes of Fornell–Larcker criterion, cross-loading, and the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT). Meanwhile, to report the reliability of the data, an internal consistency reliability process was done. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) were two approaches for reliability; both values should be bigger than 0.700. For the assessment model, we reported the significance of the relationship through path coefficient, t-value, and p-value.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

Hair et al. [36] encouraged four assessments of measurement models for PLS-SEM that include assessing reflective indicator loadings, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

4.1.1. Reflective Indicator Loadings

The reflective indicator loadings achieved in SEM should be bigger than 0.700 [36,37,38]. From the computation, all loadings were higher than 0.700. The highest loading was achieved by Employability, E2 (0.9186), while the lowest loading referred to Facilitating condition, Fc1 (0.7089). The process of indicators’ dropping (twelve) was conducted to achieve the acceptable loadings since they had low loadings; (1) educational processes (EP8, 0.5124; EP9, 0.2134; EP10, 0.4636; EP15, 0.6122; EP17, 0.6881), (2) facilities (Fc2, 0.5622; Fc3, 0.6114;), (3) research activities (RA6, 0.5432; RA8, 0.6778; RA9, 0.5110), and (3) practical activities (PA3, 0.5891; PA5, 0.4115). After the deletion process, thirty-four indicators were included for the next data analysis process (Table 2).

Table 2.

Reflective indicator loadings, internal consistency reliability, and convergent validity.

4.1.2. Internal Consistency Reliability (ICR)

ICR was implemented to evaluate the results consistency of results across indicators. In the current approach, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) were reported. The values for ICR should be from 0 to 1. Cronbach’s alpha and CR values should be greater than 0.700 [26,36,39]. Table 2 presents the reports of Cronbach’s alpha and CR. The Cronbach’s alpha and the CR values for all constructs are sufficient, exceeding the recommended amount. Employability had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8641 and CR of 0.9137, while knowledge, skills, and competencies had an alpha of 0.9200 and CR of 0.9378. Moreover, facilities obtained an alpha of 0.7900 and CR of 0.8639. Educational processes had an alpha of 0.9151 and CR of 0.9291. Practical activities possessed an alpha of 0.9446 and CR of 0.9265. Finally, research activities obtained an alpha of 0.9037 and CR of 0.9269.

4.1.3. Convergent Validity

Convergent validity is described as a topic that is related to construct validity; tests with the same or similar construct should be highly related [36]. The convergent validity in this study is reported through the calculation of average variance extracted (AVE). We applied the SmartPLS 3.2 to calculate the AVE [36]. Through the algorithm, AVE values should be 0.500 or higher, explaining 50% or more of the variance (Table 2). From the computation, all constructs obtained AVE values of higher than 0.500 or explaining more than 50% of the variance. Employability’s AVE value was 0.7874, educational processes’ AVE was 0.5675, facilities’ AVE was 0.6144, KSC’ AVE was 0.7158, practical activities’ AVE was 0.7733, and research activities was 0.6763.

4.1.4. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity is the extent to which a construct is empirically distinct from other constructs. Three approaches were used in this study to examine the discriminant validity, namely the Fornell–Larcker criterion, cross-loadings, and HTMT. For the Fornell–Larcker criterion, a construct’s shared variance should be smaller than others’ AVE [40]. Table 3 shows that the values of each construct’s shared variances are smaller than the construct. For example, the value of practical activities (0.8793) is greater than all of its shared variances; educational process (0.6574), and employability (0.5087), facilities (0.5623), and KSC (0.6991). The discriminant validity was established based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion. Besides, discriminant validity emerges if an indicator loading on a construct is greater than its cross-loadings [26,36]. Table 4 performs all indicators’ loadings and their cross-loadings. The outer loadings (in bold) for every construct were greater than the other constructs’ loadings. For example, the indicator E1 within the construct of employability obtained the highest loading of 0.9116 if being compared to its other constructs’ loadings (e.g., educational processes = 0.5381; facilities = 0.3703; knowledge, skills, and competencies = 0.5858; practical activities = 0.4691; and research activities = 0.5037). Another example is the loading values of RA 2 in the construct of research activities (0.8479) is greater than its cross-loading values; RA 2 in educational processes (0.5597), KSC (0.6045), facilities (0.4457), and employability (0.4333). All cross-loading computation was reported in detail in Table 4. Discriminant validity will also appear when the HTMT is higher than 0.900. HTMT above 0.900 refers to a lack of discriminant validity [36]. Performed in Table 5, all HTMTs are below 0.900, significantly differ from 1; therefore, HTMT evaluation was supporting the discriminant validity. The lowest HTMT emerges on the path between facilities and employability (0.4275), while the higher HTMT value exists between KSC and research activities (0.7999). The other HTMT values that resulted from the computation are employability and educational processes (0.6407), Facilities and educational processes (0.6581), KSC and educational processes (0.7869). A more detailed elaboration on the HTMT values shown in Table 5.

Table 3.

Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Table 4.

Loading and cross-loading of measures.

Table 5.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio for discriminant validity (HTMT < 0.900) [36].

4.2. Structural Model

4.2.1. Collinearity

The assessment of the structural model involved the examination of the model’s predictive capabilities. However, before reporting the structural model, the collinearity value should be noted by reporting the variance inflation factor (VIF) values. Notably, the sets of predictors were assessed for the collinearity [36]; facilities as a predictor of educational processes, practical activities, and research. Educational processes, practical activities, and research activities are the predictors of KSC and employability (Table 6). VIF values should be lower than 3; the values exceeding three are often regarded as having multicollinearity problems. From the results of the data analysis, all VIFs are lower than 3. Facilities as a predictor of the educational process, practical activities, and research activities obtained a VIF value of 1.000. Educational processes as a predictor of KSC and employability had a VIF value of 2.168. Practical activities and research activities as predictors of KSC and employability gained VIF values of 2.260 and 2.499, respectively (Table 6). Therefore, collinearity is not an issue for the model of this study.

Table 6.

Variance inflation factor (VIF < 3) [36].

4.2.2. Structural Model

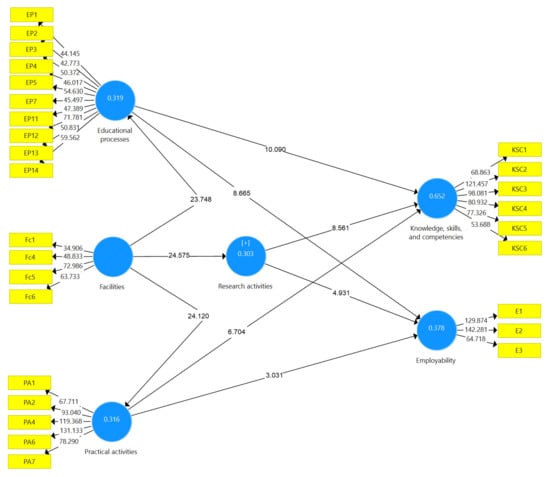

For the structural model, the significance of all direct effects or hypotheses was assessed by examining the path coefficients, t-statistics, and p-value. We computed the data through a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples. The results of the bootstrapping computation are presented in Table 7 and Figure 2; Table 7 informs the hypotheses, relationship, path, t-value, and p-value, while Figure 2 presents the t-value and loading value of the path lines within the bootstrapping procedure. The highest t-value was obtained by the path between facilities and research activities (t = 24.5754), while the lowest value was the relationship between practical activities and employability (t = 3.0306). All hypotheses proposed in this study were supported. In detail, H1 was reported to be significant influencing educational processes (β = 0.5644; t = 23.7480; p < 0.001) and practical activities (β = 0.5623; t = 24.1196; p < 0.001). H3 was also supported where research activities are significantly predicted by facilities (β = 0.5504; t = 24.5754; p < 0.001). Similarly, the significant role of educational processes to KSC (H4) was also reported (β = 0.3380; t = 10.0896; p < 0.001). Educational processes is also a significant predictor for employability, H5 (β = 0.3303; t = 8.6647; p < 0.001). The result of PLS-SEM results supports H6 because there is a significant direct effect of practical activities on KSC (β = 0.2519; t = 6.7039; p < 0.001). H7 is also supported as employability is significantly predicted by practical activities (β = 0.1351; t = 3.0306; p < 0.005). Finally, the findings also support hypotheses 8 and 9. Positive relationships also emerged between research activities and KSC (β = 0.3159; t = 8.5610; p < 0.001). Research activities is also informed to be a significant predictor for employability (β = 0.2196; t = 4.9313; p < 0.001).

Table 7.

Path, t-value, and p-value.

Figure 2.

The results estimated through PLS-SEM in the SmartPLS 3.3 (n = 1086).

5. Discussion

The current research validates the model that highlights factors predicting students’ KSC and employability. The process began with reviewing the literature followed by content validity with two sessions of discussions with educational experts. Further, assessing the measurement model in the PLS-SEM was conducted. When first initiated, the scale of the questionnaire consists of forty-nine indicators. Some indicators were removed in the content validity. Forty-six indicators were included in the main data collection and analysis. Finally, thirty-four indicators were valid and reliable after the measurement model approach. Similar approaches have been introduced by previous studies conducted to validate and examine the reliability of scales [6,41]. The process is an effort to elaborate on the undefined predictors affecting the covariation among the constructs. The valid and reliable instrument from this study can guide future researchers interested in doing similar types of study.

To support the primary purposes of the study (hypothesis 4 to hypothesis 9), we included facilities as a construct to predict educational processes (H1), practical activities (H2), and research activities (H3). Firstly, an educational process was significantly predicted by facilities, supporting H1 of the study. This significant relationship should be encouraged by improving the quality and quantity of adequate infrastructures to improve educational processes [6]. Facilitating conditions have played a vital role in influencing the teaching and learning process with technology [42]. Facilities also significantly predict practical activities. Gora et al. [6] introduced the relationship within a similar context as this study finding showing that both of them were significantly correlated. The assessment of the structural model also supported hypothesis 3; research activities were significantly affected by facilities. In sum, all supporting infrastructures, such as sufficient buildings, technology-based classrooms, laboratories, and other equipment, are very important for educational processes as well as practical and research activities.

Hypotheses 4 and 5 refer to the role of educational processes towards Indonesian medical students’ KSC and employability. For hypothesis 4, the findings inform that the educational processes significantly predict students’ KSC. It encourages the idea that the KSC for sustainability in Indonesian medical institutions needs to improve pedagogical and instructional aspects. Specifically, it refers to the quality of the curriculum, educational activities, and evaluation [6,14]. The educational processes in this study possess a very significant contribution to support employability; the finding supports hypothesis 5. It can refer to the quality of educational processes that could improve the rate of acceptance of medical students in related institutions. Similar findings were reported [6,19] to report that employability was predicted by the educational processes. Through the results of this study, it is recommended that Indonesian medical education institutions could improve their pedagogical and content quality to guarantee employability. In medical education, students are the educational processes center that challenges appear daily. Students’ ways of thinking, values, habits, self-concepts, needs, diversity and academic background should be improved. Proved feedback should be utilized to improve their KSC and employability.

The sixth and seventh hypotheses were also supported. The findings show that the practical activities significantly predict Indonesian medical students’ KSC. The elaboration encourages the research results published by Gora et al. [6] and Tranca [20]; they informed that practical activities were related to students’ KSC. In brief, the more practical activities are conducted, students could achieve KSC better. Practical activities play a significant role in predicting employability (H6). However, Gora et al. [6] reported that practical activity was not a significant predictor of employability. Teachers are recommended to foster the practical abilities of students they teach. It aims at increasing the quality of the graduate to fulfill the high demand of the labor market. Thus, practical activities should always be promoted in HEIs [5].

The results of this study also promoted the last two hypotheses (H8 and H9). Research activities perceived by Indonesian medical students significantly predict their knowledge, skills, and competencies, supporting the 8th hypothesis. As Webster and Kenney [32] informed that in the current social life condition and technology advancement where everyone connected to the Internet can instantly access information, the improvement of research knowledge, skills, and competencies is essential. A similar finding exposed a strong predictive power of research activities towards knowledge, skills, and competencies [6]. The study’s finding also supported H9; research activities significantly predict Indonesian medical students’ perceptions of employability. The report promotes the previous result [6]. The recognition of institution demands regarding the attempts to better their institutions require research experience. Therefore, this factor could have a significant role in the students’ perception of employability for their future careers in the medical field [43].

6. Conclusions

The valid and reliable scale produced by the results of this study can inform predictors that affect KSC and employability [44]. The presentation of the scale is important to enrich literature sources in the context of medical education and quality assurance in higher education. More important, all hypotheses proposed in this study are confirmed that would produce theoretical and practical implications. Both KSC and employability are significantly predicted by educational processes, practical activities, and research activities. Similarly, facilities are a significant predictor for educational processes, practical activities, and research activities. From the theoretical perspectives, these findings offer a conceptual framework that relates to HEIs quality factors. In this study context, the report informs the validity and reliability data through a comprehensive process from the survey questionnaire’s initiation to assessing the measurement model using PLS-SEM. From a practical view, the perspectives of Indonesian medical students are essential for policymakers to set appropriate regulations toward improving students’ KSC and employability, highlighting the direct relationships among exogenous and endogenous variables. The right policies can trigger Indonesian universities to become responsible for their institution evaluation and accreditation to improve their graduates’ KSC and employability for the labor market. By enhancing the factors affecting the outcomes, students would benefit from the sustainable policies for their learning environment. For future studies, the findings can be a set of guidelines for researchers to conduct.

However, some limitations should be considered within this study. Extended samples, methods, and majors are suggested. Studies in bigger samples regarding quality management could be conducted to improve KSC and the labor market’s chance. Other methods, such as observation, experimental studies, and interviews, would also be interesting for similar tasks. Additionally, more general majors are recommended for future studies, especially in the HEIs quality management context of developing countries. In other words, the findings of the current study can be adapted in various contexts of education, namely social science, engineering, humanity, and science). The open-accessed survey instrument can be adapted by future researchers who are interested in conducting similar topics of research.

Even though academic implications emerged from the results, the current study is not free from limitations. The quantitative result might not represent an in-depth understanding of each respondent regarding the topic of the research. A qualitative procedure would greatly contribute to supporting the findings of the research. Another limitation is regarding the respondents of the study, who are medical graduates and students. Thus, it is recommended to conduct studies on other contexts and settings to possibly report whether the findings differ by nature and period. The current study does not explore the significant differences based on demographic information, such as gender, age, sex, and institutions; multiple group analysis (MGA) or MANOVA analysis could support and complete the study’s findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H., A.M. and M.M.; formal analysis, E.E. and A.P.; funding acquisition, All authors; investigation, A.D.F. and A.M.; methodology, A.D.F. and A.H.; project administration, A.D.F., A.M., E.E. and A.H.; resources, A.D.F., A.M., E.E. and M.M.; software, S.T.; supervision, H.H., A.M. and M.M.; validation, A.D.F., E.E., A.H. and N.N.A.S.; writing—original draft, A.D.F., A.A.S., M.F.M.Y., M.H. and A.H.; writing—review and editing, M.M., M.H., A.A.S., M.F.M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-funded by Universitas Jambi, LPDP Indonesia, and Universiti Utara Malaysia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee (MHREC) Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada (KE/FK.1157/EC/2020, 21 October 2020)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/7dwbmybkyc/2 (accessed on 25 April 2021).

Acknowledgments

We thank all administrative and technical support from all related Indonesia medical schools. We also address our gratitude to all respondents of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Poza-Vilches, F.; López-Alcarria, A.; Mazuecos-Ciarra, N. A Professional Competences’ Diagnosis in Education for Sustainability: A Case Study from the Standpoint of the Education Guidance Service (EGS) in the Spanish Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-Oriented Higher Education: Which Key Competencies Should Be Fostered through University Teaching and Learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vykydal, D.; Folta, M.; Nenadál, J. A Study of Quality Assessment in Higher Education within the Context of Sustainable Development: A Case Study from Czech Republic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Van Petegem, P. The Interrelations between Competences for Sustainable Development and Research Competences. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 776–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Vatamanescu, E.M. Students’ Perception on Developing Conceptual Generic Skills for Business: A Knowledge-Based Approach. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2017, 47, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gora, A.A.; Ştefan, S.C.; Popa, Ş.C.; Albu, C.F. Students’ Perspective on Quality Assurance in Higher Education in the Context of Sustainability: A PLS-SEM Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, L.; Nicolescu, C. Using PLS-SEM to Build an Employability Confidence Model for Higher Education Recipients in the Field of Business Studies. Kybernetes 2019, 48, 1965–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.K.; Bhatt, M.P. The Importance of Infrastructure Development to High-Quality Literacy Instruction. Future Child. 2012, 22, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; González-Zamar, M.D.; Infante-Moro, J.C.; García, G.R. Sustainable Management of Digital Transformation in Higher Education: Global Research Trends. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, G.K.A.; Azevedo Lopes, F.W. Infraestrutura de Saneamento Básico e Incidência de Doenças Associadas: Uma Análise Comparativa Entre Belo Horizonte e Ribeirão Das Neves—Minas Gerais [Sanitation Infrastruture and Associeted Diseases: A Comparative Analysis between Belo Horizonte and Ribeirão Das Neves—Minas Gerais]. Cad. Geogr. 2017, 27, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendratno, S.S.; Subagyo, H.; Rafilluddin, Z.; Mogensen, M.; Hall, A.; Bundy, D. Partnership for Child Development: An International Programme to Improve the Health of School-Age Children by School-Based Health Services Including Deworming. Control. Dis. Due Helminth Infect. 2003, 25, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sujarwoto, S.; Tampubolon, G. Spatial Inequality and the Internet Divide in Indonesia 2010–2012. Telecommun. Policy 2016, 40, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryadarma, D.; Widyanti, W.; Suryahadi, A.; Sumarto, S. From Access to Income: Regional and Ethnic Inequality in Indonesia. SMERU Work. Pap. 2006, 21, ii23. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts, W.; Mulà, I.; Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Gaeremynck, V. The Integration of Competences for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: An Analysis of Bachelor Programs in Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čepić, R.; Vorkapić, S.T.; Lončarić, D.; Andić, D.; Mihić, S.S. Considering Transversal Competences, Personality and Reputation in the Context of the Teachers’ Professional Development. Int. Educ. Stud. 2015, 8, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltner, E.M.; Rieß, W.; Mischo, C. Development and Validation of an Instrument for Measuring Student Sustainability Competencies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, P.T.; Yorke, M. Employability and Good Learning in Higher Education. Teach. High. Educ. 2003, 8, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allui, A.; Sahni, J. Strategic Human Resource Management in Higher Education Institutions: Empirical Evidence from Saudi. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José Sá, M.; Serpa, S. Transversal Competences: Their Importance and Learning Processes by Higher Education Students. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trancă, L.M. Competences of Students in Social Work from the Perspective of Practical Work Supervisors in the Field of Delinquency. In The Fifth International Conference Multidisciplinary Perspectivesin the QuasicoerciveTreatment of Offenders Probation as a Field of Study and Research: From Person to Society; Filodiritto Editore: Bologna, Italy, 2016; pp. 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butum, L.C. The Role of International Competences in Increasing Graduates’ Access to the Labor Market. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M.; Elen, J. The “research-Teaching Nexus” and “Education through Research”: An Exploration of Ambivalences. Stud. High. Educ. 2007, 32, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brew, A. Imperatives and Challenges in Integrating Teaching and Research. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2010, 29, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukminin, A.; Habibi, A.; Muhaimin, M.; Prasojo, L.D. Exploring the Drivers Predicting Behavioral Intention to Use M-Learning Management System: Partial Least Square Structural Equation Model. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 181356–181365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A.; Yusop, F.D.; Razak, R.A. The Role of TPACK in Affecting Pre-Service Language Teachers’ ICT Integration during Teaching Practices: Indonesian Context. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 1929–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiles, B.B.; Thompson, J.A.; Griebling, T.L.; Thurmon, K.L. Perception, Knowledge, and Interest of Urologic Surgery: A Medical Student Survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbarczyk, A.; Nagourney, E.; Martin, N.A.; Chen, V.; Hansoti, B. Are You Ready? A Systematic Review of Pre-Departure Resources for Global Health Electives. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faham, E.; Rezvanfar, A.; Movahed Mohammadi, S.H.; Rajabi Nohooji, M. Using System Dynamics to Develop Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education with the Emphasis on the Sustainability Competencies of Students. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 123, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Merrill, M.Y.; Sammalisto, K.; Ceulemans, K.; Lozano, F.J. Connecting Competences and Pedagogical Approaches for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: A Literature Review and Framework Proposal. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, A.; Steiner, G. Integrating Research and Teaching on Innovation for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2006, 7, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.M.; Kenney, J. Embedding Research Activities to Enhance Student Learning. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2011, 25, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B. Successful Implementation of TPACK in Teacher Preparation Programs. Int. J. Integr. Technol. Educ. 2015, 4, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zartner, D.; Carpenter, K.; Gokcek, G.; Melin, M.; Shaw, C. Knowledge, Skills, and Preparing for the Future: Best Practices to Educate International Studies Majors for Life after College. Int. Stud. Perspect. 2018, 19, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdfelder, E.; FAul, F.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A.; Yusop, F.D.; Razak, R.A. The Dataset for Validation of Factors Affecting Pre-Service Teachers’ Use of ICT during Teaching Practices: Indonesian Context. Data Brief 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.A.; Shateri, K.; Amini, M.; Shokrpour, N. Relationships between Academic Self-Efficacy, Learning-Related Emotions, and Metacognitive Learning Strategies with Academic Performance in Medical Students: A Structural Equation Model. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhaimin, A.; Habibi, A.; Mukminin, A.; Hadisaputra, P. Science Teachers’ Integration of Digital Resources in Education: A Survey in Rural Areas of One Indonesian Province. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Huang, Z.; Othman, B.; Luo, Y. Let’s Make It Better: An Updated Model Interpreting International Student Satisfaction in China Based on PLS-SEM Approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcar, J.; Janíčková, L.; Filipová, L. What General Competencies Are Required from the Czech Labour Force? Prague Econ. Pap. 2014, 2, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, A. Quality Assurance in Higher Education: Indonesian Medical Education Context. Mendeley Data V2 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).