Abstract

Organizational resilience is an important means of coping with crises. This concept has received much attention within both academia and industry. However, research on the definition and measurement of organizational resilience is still in the exploratory stage. To date, studies on organizational resilience have yielded mixed conclusions, which makes it difficult to provide specific recommendations for coping with crises. This paper uses an exploratory case study approach to explore the process of organizational resilience among six highly resilient companies: Southwest Airlines, Apple, Microsoft, Starbucks, Kyocera, and Lego. We employed grounded theory to distill the main characteristics of organizational resilience, to explore and validate its structural dimensions, and to develop a measurement scale for organizational resilience. Further, we conducted reliability and validity analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and validation factor analysis on the 526 valid data collected. Results show that organizational resilience includes five dimensions: capital resilience, strategic resilience, cultural resilience, relationship resilience, and learning resilience. The measurement scale has good reliability and validity, which better reflects the notion of organizational resilience. This study bridges the gaps in the existing literature on organizational resilience and its measurement scales, and provides a foundation for future research.

1. Introduction

Today’s business environment is increasingly complex and volatile [1]. With the globalization and the internationalization of business activities, crises seem to have become regular events in the development of organizations [2,3]. These “black swans” (small probability but high impact events) or “gray rhinos” (large probability and high impact potential crises) include the September 11 attacks, the 2008 financial crisis, the 2011 tsunami in Japan, the 2013 Ebola virus in Africa, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. These events pose increasing challenges to the survival and development of organizations [4]. Therefore, how companies can manage risk and continue to grow during crises has become a key issue that must be addressed by decision makers. Why are some organizations better able to cope with adverse environmental conditions and survive in the face of a crisis? What kinds of processes lead to the adoption of new operation procedures? In essence, these are issues of organizational resilience [4,5,6,7]. Empirical and theoretical studies show that organizational resilience is the most direct factor explaining why companies can successfully overcome crises. This is because highly resilient companies have strong organizational resilience and they are able to overcome existential crises. There is growing evidence that resilient organizations have the ability to adapt to market changes and are more likely to remain relevant and responsive to market changes [8,9]. Some scholars have even linked resilience to the long-term development of companies [10]. For instance, Somers (2009) [11] defined organizational resilience as the ability of a firm to take measures in advance to cope with a crisis. Thus, the study of organizational resilience is of great importance, not only in terms of providing new theoretical perspectives on crisis management, but also in terms of helping companies to grow through crises in practice.

After reviewing the research on organizational resilience, we found that this topic has received increasing attention in academic circles over the past 30 years [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Organizational resilience has been addressed in the fields of positive psychology [21], ecosystematics [22], engineering [23,24], and management [8,13]. Existing studies on organizational resilience have mainly focused on its definition and measurement, the factors influencing it, its mechanisms of operation, and its effects. Scholars have also looked at organizational resilience from the perspective of stakeholders [25,26,27], self-esteem [28,29], and leadership behavior [30,31,32,33]. However, most studies lack both a systematic theoretical exploration and a clear definition of organizational resilience [10,34]. Some scholars have conducted exploratory research on organizational resilience as an independent concept and proposed a measurement scale for organizational resilience [35,36,37,38,39,40]. However, scholars still do not have a unified opinion for the study of organizational resilience, and there are few in-depth evaluations of the dimensions of organizational resilience, which limits the scope of the research [39].

To address these limitations, this study provides an in-depth analysis of the concept of organizational resilience. We then conduct an exploratory multiple case study of six highly resilient companies, namely Southwest Airlines, Apple Inc., Microsoft, Starbucks, Kyocera, and Lego. We explore the dimensions of organizational resilience using grounded theory, develop measurement scales, and conduct empirical tests by combining theories and research results related to organizational resilience. Our study seeks to answer the following questions: What is organizational resilience? What are the processes involved in organizational resilience? How can companies in crisis achieve sustainable growth in spite of the crisis? We aim to help scholars better understand the meaning of organizational resilience and provide a reliable measurement basis for the empirical analysis of organizational resilience.

This paper contributes to the literature on organizational resilience in three ways. First, by reviewing existing research on organizational resilience, we found that it is a complex concept that is cross-level and multidimensional [39]. We clarify what organizational resilience is, providing an overarching definition and outlining how the specific process unfolds. In doing so, our study provides a systematic interpretation of the definition of organizational resilience in existing studies.

Second, scholars generally agree that organizational resilience is a multidimensional construct [27,41,42]. So far, scholars have built on the definition provided by McManus et al., (2008) [35] and they have added other aspects to the concept of organizational resilience. Based on organizational resilience theory, this study explores the structure of organizational resilience through qualitative research, selecting six highly resilient companies as research subjects. Using grounded theory to code our qualitative data, we divide organizational resilience into subcomponents, namely capital resilience, strategic resilience, cultural resilience, relational resilience, and learning resilience. This study makes creative use of qualitative research methods to make up for the shortcomings of existing studies on organizational resilience structures.

Third, we have developed a scale for measuring organizational resilience based on the studies of McManus et al., (2008) [35], Linnenluecke et al., (2012) [43], Godwin and Amah (2013) [44], and others. Thus far, scholars have constructed a measurement scale for organizational resilience from different perspectives and viewpoints based on the works of McManus et al., (2008) [35] and others [36,39,45]. However, fewer have used qualitative research methods to explore the structure of organizational resilience through the grounded theory research approach or developed a scale for measuring organizational resilience that has been accepted by other scholars. This study aims to provide a better measure organizational resilience and lays the foundation for further empirical studies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on organizational resilience, summarizes its various definitions, and defines the meaning of organizational resilience. Section 3 presents the research design and case analysis, describing the criteria for case selection, data collection, and analysis strategy. Section 4 presents the organizational resilience scale, including the initial measurement questions. Section 5 conducts the validity test for the scale, including the data collection, sample characteristics, and data analysis. Section 6 discusses the results obtained in this study, presents directions for future research, and concludes.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

The concept of resilience emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the field of physics. It refers to the ability of a system to cope with change [46]. Beginning in the mid-1880s, the concept of resilience began to penetrate into the field of ecology, where it was first introduced by Holling (1973) [47] in the article entitled “Resilience and stability of ecological systems.” In this article, the concept of resilience was introduced into the study of ecological environments, which refers to the ability of an ecosystem to recover to its previous state after being damaged. Later, Wildavsky (1988) [48] analyzed resilience in the context of organizational research. However, it was not until the late 1990s that the study of resilience within organizations gained popularity among scholars, who began to focus on post-disaster resilience research [44,49]. This includes research into events such as Hurricane Katrina, the September 11 attacks, as well as corporate resilience [50,51]. Moreover, there is a broader discussion on resilience in information systems [52], healthcare systems [13], and supply chains [53]. In recent years, organizational resilience has been well explored in the field of psychology. Researchers have studied psychologically well-adjusted children in high-risk environments, arguing that organizational resilience is the positive adaptive capacity that individuals show when experiencing adverse conditions [39].

In the organizational theory literature, resilience has been studied in the areas of disaster management, crisis management, and high-reliability organizations [54,55,56,57]. Nevertheless, scholars have not yet reached a unified conclusion regarding what constitutes organizational resilience [10]. As shown in Table 1, most existing studies interpret organizational resilience from the capability perspective, process perspective, functional perspective, and outcome perspective. We found that scholars with a dynamic view advocate exploring organizational resilience from a capability and process perspective, while scholars with a static view advocate exploring organizational resilience from an outcome and functional perspective. Scholars adopting a process perspective consider organizational resilience as a dynamic and progressive process exhibited by firms in response to crisis or adverse situations. Firms may adopt behaviors such as identity management, reintegration, improvisational coping, and emotional labor [6,58]. Scholars adopting the capability perspective consider organizational resilience as a dynamic and flexible organizational capability synthesized from predictive capability, survival capability, adaptive capability, coping capability, and learning capability that organizations exhibit in response to crises [1,20,59]. Scholars from an outcome perspective consider organizational resilience as the ability of organizations to remain in a positive adaptive state in the face of crises [60,61]. Scholars from a functional perspective view organizational resilience as a function of an organization’s ability to adapt to dynamic and complex environments [35,62].

Table 1.

Concept of organizational resilience.

Our systematic review of the research on organizational resilience shows that the concept is applied in a number of fields such as ecology, psychology, and economics. In summary, organizational resilience contains three main essential elements. First, the organization operates in a dynamic environment. Second, the organization responds to the crisis by reconfiguring organizational resources, reshaping organizational relationships, and optimizing organizational processes in an adverse situation. Third, the organization reaches recovery and achieves growth. Therefore, we regard organizational resilience as the ability of an organization to reconfigure organizational resources, optimize organizational processes, reshape organizational relationships in a crisis, recover quickly from the crisis, and use the crisis to achieve counter-trend growth. Organizational resilience emphasizes the ability of companies to not only get out of a difficult situation, but also to drive growth in a crisis.

Although scholars have interpreted the concept of organizational resilience from different perspectives, there is no universally accepted standard for the study of the structure and its measurement. As shown in Table 2, most of the existing studies can be divided into two-factor, three-factor, and four-factor structures. McManus et al. (2008) [35] proposed that organizational resilience encompasses planning capacity and adaptive capacity. Based on an analysis of 10 firms in the New Zealand region, the authors developed 13 resilience indicators to measure organizational resilience. Later, scholars such as Godwin and Amah (2013) [44] and Umoh et al. (2014) [41] incorporated organizational learning into organizational resilience. Godwin and Amah (2013) developed separate 15-item scales measuring organizational resilience using 128 employees from 34 manufacturing firms in Nigeria. Borekci et al. (2014) [71] focused on organizational structure and organizational capacity. The authors conducted an analysis of 109 service firms in Turkey. They developed a 15-item measurement scale and suggested that organizational resilience encompasses structural dependence, organizational capacity, and process continuity. Kantur and Say (2015) [39] argued that organizational resilience includes robustness, agility, and integrity, and developed a 10-item scale for measuring organizational resilience. In recent years, scholars have generally considered organizational resilience as a four-dimensional construct, with some arguing that it includes robustness, redundancy, adequacy, and rapidity [62,72,73,74]. According to Richtnér and Löfsten (2014) [75], organizational resilience includes structural, cognitive, relational, and emotional competencies. They came to their conclusions through an analysis of 329 technology-based companies in Sweden, and developed a 14-item measurement scale.

Table 2.

Dimensional components and related measures of organizational resilience.

Overall, the study of organizational resilience has been widely discussed in the fields of organizational behavior and strategic management. While qualitative and quantitative research continues to evolve, quantitative research on organizational resilience has developed more slowly. This is mainly due to the fact that scholars have different perceptions of organizational resilience, and there is still a lack of a uniform scale for measuring organizational resilience [39,40]. This study seeks to address this gap by constructing a unified definition of organizational resilience through an exploratory case study approach and then develop a scale to measure organizational resilience.

3. Research Design and Case Study Analysis

3.1. Case Selection

This study utilized an exploratory case study method. We selected six highly resilient companies, based on their typicality and the ease of access to information: Southwest Airlines, Apple, Microsoft, Starbucks, Kyocera, and Lego (see Table 3). First, two criteria were set for case selection. We selected companies that have been in existence for more than 40 years, and that had suffered a major crisis but emerged successfully and achieved sustained growth. These are highly resilient companies from Japan, the United States, and Denmark, respectively. These six companies have been in existence for more than 40 years. The oldest company is Lego, which was founded in 1932 and has 88 years of history. The youngest company is Apple, which was founded in 1976, with 44 years of history. There is no doubt that these six companies have experienced many crises over the past few decades, and they have all managed to survive and they have experienced growth against all odds. Although these six companies encountered different types of crises (some arising from the external environment and some from the lack of internal strategy), the resilience of these companies is worth studying.

Table 3.

Information on the companies selected.

Second, we selected the cases based on the ease of access to information. The annual reports of highly resilient companies contain important analytical material in the form of letters from the CEO or Chairman to investors. Each letter details the issues faced by the company in a respective year and the major initiatives the company has taken. In times of crisis, the annual report analyzes the reasons why the company survived the crisis. We also analyzed media reports and management commentaries on the six companies that were published in the Harvard Business Review, the Wall Street Journal, Business Week, and The Economist. We also studied books that were published about the six companies. In the process of screening the textual data, we adopted a problem-oriented approach to record and organize the events related to these six companies and the crises they faced. The database contained over 200 key events that occurred in these six companies in response to a crisis, which provides a strong basis for this study.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

We collected textual data with information on the six companies from company annual reports, published books, industry information, and the Harvard Business Report. To ensure the validity and completeness of the data, this study triangulated the information from different data sources. Specifically, the information collected was verified through multiple channels and in different ways. For example, we verified the authenticity of the information by communicating with the relevant managers of the companies, in order to enhance the robustness of the conclusions. To ensure the accuracy of data analysis, we also invited teachers and Ph.D. students with experience in conducting case studies to assist as we conducted our research.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study follows the research procedure outlined in procedural rooting theory to sort and code the obtained data. Rooting theory is a top-down research method that constructs theories in an inductive form [90]. Compared to constructive rooting theory and classical rooting theory, the procedural rooting method is clearly structured and simple to operate. This not only provides rigorous guidelines for researchers, but also offers concise operational steps. For example, the research procedure for programmed grounded theory includes three processes: open coding, spindle coding, and selective coding [91]. In order to ensure the accuracy and rigor of the coding, a coding team consisting of three doctoral students, two master’s students, and one professor was established. Each member independently coded the textual information and subsequently compared and adjusted the codebook to improve the reliability of the study.

3.3.1. Open Coding

Open coding is the process of interpreting the collected data, exploring the meaning behind the data, and using conceptualization and categorization to condense the intrinsic essence of the data, with the ultimate goal of achieving data aggregation. The open coding process requires the researcher to approach the data with a critical perspective and to be problem-oriented so that the information can be captured accurately. Table 4 shows the open coding process.

Table 4.

Open coding results.

It is important to note that different sample profiles may respond to different aspects, which means that a category or concept may come from one sample, while others play a complementary and supportive role. The main goal of this study is to find the concepts and categories that best describe, categorize, and compare the data. A total of 107 concepts and 20 categories were obtained in this study.

3.3.2. Axial Coding

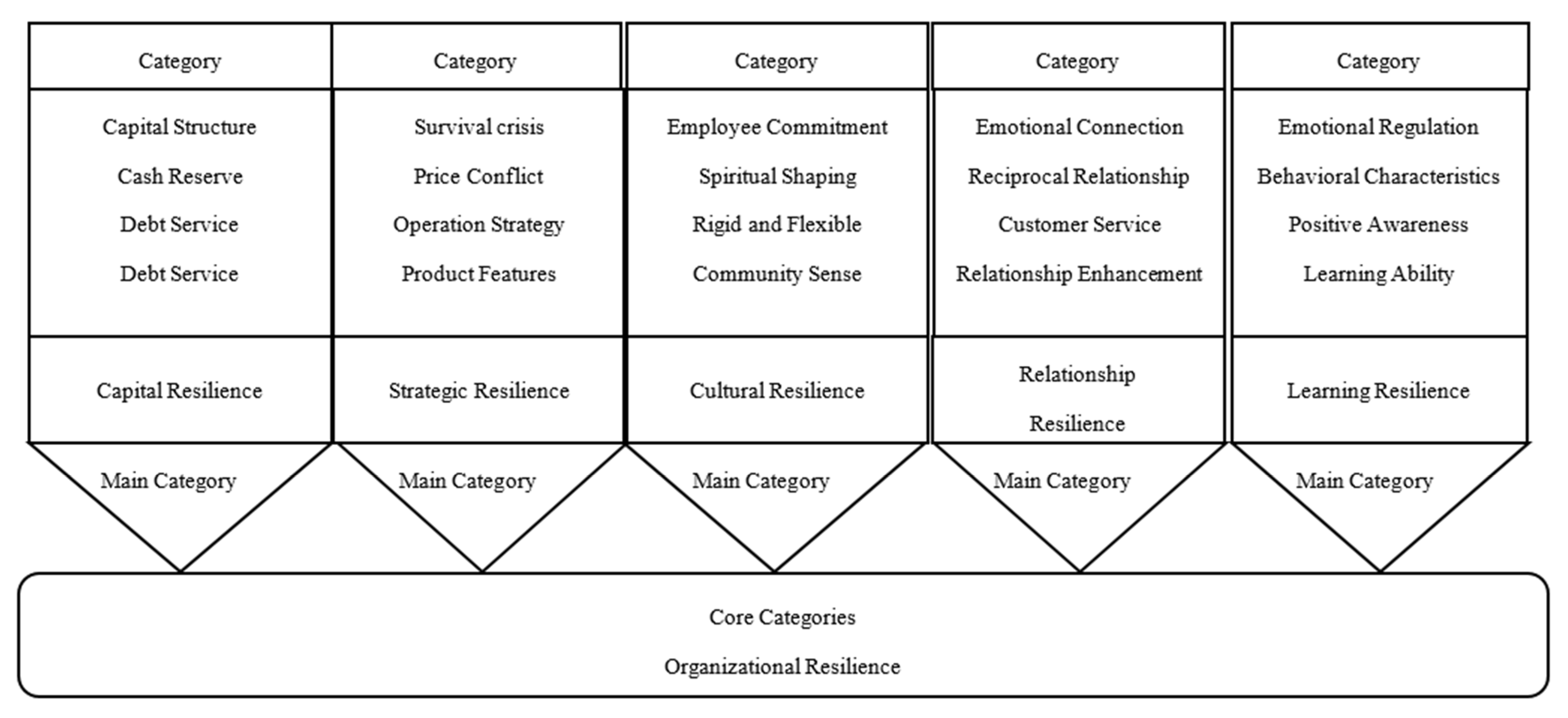

Axial coding is the process of further sorting and generalizing the categories established through open coding in order to discover the relationships between the categories. We used the process referred to as main axis coding, which is mainly based on the following model: “causal condition—phenomenon—action strategy—outcome” [92]. We clarified the relationships between the categories obtained in the open coding and form larger classes, thus, forming the master category [92]. After generalization and refinement, we finally obtained five categories, namely capital resilience, strategic resilience, cultural resilience, relationship resilience, and learning resilience (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Axial coding.

3.3.3. Selective Coding

Selective coding is based on the axial coding, and a more complete structure emerges by analyzing around the core categories so as to discover the core categories that can unify the other categories. Based on the interaction of resilience theory and data, the four main categories of capital resilience, strategic resilience, cultural resilience, relationship resilience, and learning resilience were extracted. Moreover, the core category of organizational resilience was further specified, which can unify all the categories of this study. The selective coding process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selective coding process.

A main finding of this study is that strategic resilience helped companies consistently identify and eliminate adverse factors that could weaken a company’s core business capabilities. Capital resilience helps companies balance their organizations’ capital structure and prepare for crises before they occur. Relationship resilience helped companies build mutually beneficial relationships between employers and employees, employees and companies, and companies and customers to help them withstand crises. Cultural resilience was the shaping of employees through corporate culture, encouraging them to have a long-term commitment toward the organization. Learning resilience is the ability of an organization to cope with the stresses it faces in the learning process, and the ability of an organization to learn various lessons for in response to a crisis. Together, these five factors formed the organizational resilience that helped companies navigate through crises and achieve sustained growth.

4. Developing the Organizational Resilience Scale

4.1. Scale Development Process

First, following existing studies, we used programmed root theory to conduct multiple case studies. We obtained five dimensions of organizational resilience: capital resilience, strategic resilience, cultural resilience, relationship resilience, and learning resilience. Second, we developed measurement items that are consistent with organizational resilience by drawing on existing measurement scales. Third, in order to analyze organizational resilience more clearly and to modify the measurement items, we conducted semi-structured interviews with the heads of the six companies who had experienced crises. During the interviews, we asked them what factors could help companies survive crises, or what organizational actions could help companies resist crises. Finally, we conducted a pre-study of the developed scale and further revised the scale to form a formal measure of organizational resilience.

4.2. Preparation of Initial Measurement Scale

In this study, the initial measurement scale was developed based on semi-structured interviews and combined with existing scales. Our measure of capital resilience was designed based on the studies of Valikangas (2010) [37] and Marsick et al. (2002) [80]. We created a total of seven questions in Likert-scale format, including “Our company has good cash flow”, “We reserve cash according to our corporate strategy and competitive model”, and “We have a sound capital structure”.

The measure of strategic resilience was designed based on the study by Davenport and Cronin (2000) [93]. We created a total of six questions, including “Our company is able to focus on its core business”, “Our company is able to identify adverse factors in its development in a timely manner”, and “We pursue a robust strategic growth model”.

The measure of cultural resilience was designed based on the studies by Meen and Keough (1992) [94] as well as Denison and Mishra (1995) [95]. It comprised a total of six questions, such as “Our corporate culture aims to develop a sense of community among employees”, “Our corporate culture fosters a sense of cooperation among employees”, and “Our corporate culture stimulates morale and spirit among employees”.

The measurement for relational resilience was mainly designed based on the studies by Shore et al. (1990) [96] and by Vogus and Sutcliffe (2007) [40]. We created a total of six questions, such as “We are able to create unique value for our customers”, “We aim for mutual prosperity between the company and our stakeholders”, and “We have a good reciprocal relationship with our employees”.

The measurement for cultural resilience was mainly designed based on the studies by Costanza et al. (2016) [87] and Ramón and Koller (2016) [88]. We created a total of six questions, such as “We will choose learning objects according to the characteristics of our own enterprise “, “We will choose the better enterprises to learn from”, and “We will have a deep knowledge of our own situation in time”. The questions are shown in Table 6 below.

Table 6.

Initial measurement scale of organizational resilience.

5. Validity Test for the Scale

5.1. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

5.1.1. Data Collection

This study was conducted over a total of five months, from July 2020 to the end of November 2020. The questionnaire was administered in Beijing, Fujian, Zhejiang, and Shanghai, where there are clusters of small- and medium-sized enterprises. The questionnaire included questions about participant demographics and about organizational resilience. The latter set of questions were designed using a 7-point Likert scale, with “1” representing complete disagreement and “7” representing strong agreement. We selected small- and medium-sized enterprises that operated in clusters for several reasons. First, these enterprises are considered resilient family businesses. Second, these enterprises better reflect the characteristics of resilience. Third, given the difficulties involved in collecting data on enterprises nationwide, the regions selected for this study comprise more enterprises than in other areas of China. Fourth, considering that the Chinese economy is dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises, it made more sense to select small and medium-sized enterprises, as this represents the situation in China more accurately.

We obtained data for this study through three main methods. First, we relied on the resources of the local Institute of Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development to conduct questionnaire surveys in Beijing, Fujian, Zhejiang, and Shanghai, and data were collected through mail and electronic questionnaires. Second, we conducted research on eligible companies in the four regions of Beijing, Fujian, Zhejiang, and Shanghai, collecting data mainly through on-site questionnaires.

5.1.2. Sample Characteristics

In this study, 900 questionnaires were distributed in four regions, and a total of 723 questionnaires were collected. By eliminating invalid questionnaires that were incomplete and that were filled out randomly, 526 valid questionnaires were finally obtained. The sample characteristics of this study are shown in Table 7 below.

Table 7.

Sample characteristics.

5.2. Data Analysis

Based on the scale development process, we first conducted an internal consistency analysis of the scale, i.e., the degree of consistency of multiple measures measuring the same concept; secondly, this study examined the structural validity, content validity, criterion validity, and face validity of the scale to ensure the validity of the scale; thirdly, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on the obtained scale to determine the optimal structure of the measurement scale and to judge the conformity of the measurement items contained in the scale with the corresponding concepts; finally, we conducted validation factor analysis (CFA) on the basis of exploratory factors to explore the relationship between theoretically delineated factors and the designed measurement items.

5.2.1. Internal Consistency Analysis

Drawing on Landers’ (2015) [97] requirements for internal consistency testing, this study applied the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) measure to test the internal consistency of the scale of organizational resilience, as shown in Table 8 below, which shows that the internal consistency of the scale was 0.911, indicating that the scale has good internal consistency.

Table 8.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for Inter-Rater Assessment.

5.2.2. Validity Analysis

Structural validity can demonstrate the reliability of the scale structure, but reliability tests do not represent validity. Chan and Idris (2017) [98] suggested that factor analysis would be an appropriate statistical measurement technique for structural validity, with measures of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. Therefore, Table 9 below explains the structural validity of the scale.

Table 9.

KMO and Bartlett’s test for validity.

Table 9 explained that the KMO value is 0.881, which can be conclude by meritorious, and this indicator is greater than the minimum standard 0.6. Thus, it indicates that the empirical measurement effectively tests the true meaning of the concept under consideration. Moreover, the approximate chi-square of Bartlett’s sphere test is 6862.277 with 190 degrees of freedom. p-value is 0.000, which is less than 0.01. Therefore, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that the questionnaire is valid at the 99% significance level.

Content validity analysis was conducted using a 4-point expert scale, with scores from 1 to 4 representing “not relevant”, “weakly relevant”, “strongly relevant”, and “very relevant”. In this study, the content validity index (I-CVI: the number of experts who rated each entry as 3 or 4 divided by the total number) was calculated based on expert ratings, and the average content validity (S-CVI/Ave) was the mean of the I-CVI of all entries. An I-CVI value greater than 0.78 and an S-CVI value greater than 0.9 indicated good internal homogeneity [99]. In this study, six experts in the field were invited to rate the entries of the scale, and the results of both I-CVI and S-CVI were 1. Therefore, the content validity of this scale is good.

To evaluate criterion validity, it could calculate the correlation between the results of the measurement and the results of the criterion measurement. This study generates the new variable for Total to represent the sum of value for the whole question and if there is a high correlation among the questions, it gives a good indication that the test is measuring what it intends to measure. For this indicator, the obtained value needs to compare with the critical value for Pearson correlation coefficient and the rule is that the obtained value should be greater than the critical value. For instance, the obtained value for the first item is 0.486. The sample size is n = 526, so the number of degrees of freedom is df = n − 2 = 526 − 2 = 524. Then the corresponding critical correlation value r_c for a significance level of α = 0.05, for a two-tailed test is 0.085. Thus, the obtained value is greater than the critical value and this would generate the significant result for criterion validity. It can be seen that the scale has good criterion validity, as shown in Table 10 below.

Table 10.

Test the validity using Pearson correlation coefficient.

Face validity refers to whether the questionnaire, in its surface form and content, is perceived as a valid questionnaire in the hands of the subjects [100], and Harrison and Wills (1983) [100] states that the only way to know the surface validity is through questionnaires or informal questioning of teachers and students. Therefore, in this study, two professors and five doctoral students in the field were invited to evaluate the face validity of this scale based on the preliminary research, and finally the experts agreed that this scale has good face validity.

5.2.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

This study used SPSS 26.0 to conduct exploratory factor analysis on the 31 measurement items of the organizational resilience scale, and then to determine the optimal structure of the scale. We found that the KMO coefficient of the organizational resilience measurement scale was 0.881, which was within the valid range. The factor significance level of Bartlett’s sphericity test was less than 0.001, which rejected the hypothesis that the correlation matrix was a unitary array, and, thus, the samples collected by this questionnaire were eligible for doing factor analysis. Next, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis using principal component analysis and found that a total of five factors were extracted. In addition, the questions with factor loadings of less than 0.4 were eliminated. These included “We reserve cash based on our corporate strategy and competitive model” and “We have a sound capital structure”.

The final measurement scale was obtained by optimizing the scale and removing the unqualified measurement questions. As shown in Table 11, the factor loadings of all five factors were above 0.6, and the cumulative variance contribution rate reached 81.059%, indicating that the organizational resilience scale has a good factor structure. Based on programmed rooting theory and on the literature on organizational resilience, this study corresponds these five factors to the five dimensions of organizational resilience. These are: (1) capital resilience (four measured items), which refers to the ability of a firm to operate normally and to recapitalize against risk in a crisis; (2) strategic resilience (four items), which refers to a company’s ability to maintain strategic consistency over time, helping it to identify and eliminate adverse factors and to be able to choose the right growth model; (3) relationship resilience (four items), which refers to the reciprocal relationships established between the company and its stakeholders; (4) cultural resilience (four items) refers to the way in which the corporate culture shapes the entrepreneurial spirit of employees and the commitment of employees to the organization; (5) learning resilience (four items), which refers to the ability of the company to cope with the pressures and challenges of learning. Through exploratory factor analysis, the non-conforming measurement items were eliminated, and the items measuring strategic resilience (SR), capital resilience (CR), relationship resilience (RR), cultural resilience (WR), and learning resilience (LR) were obtained. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient test revealed that the coefficient of each factor of organizational resilience was above 0.8, indicating that this scale has good reliability.

Table 11.

Exploratory factor analysis.

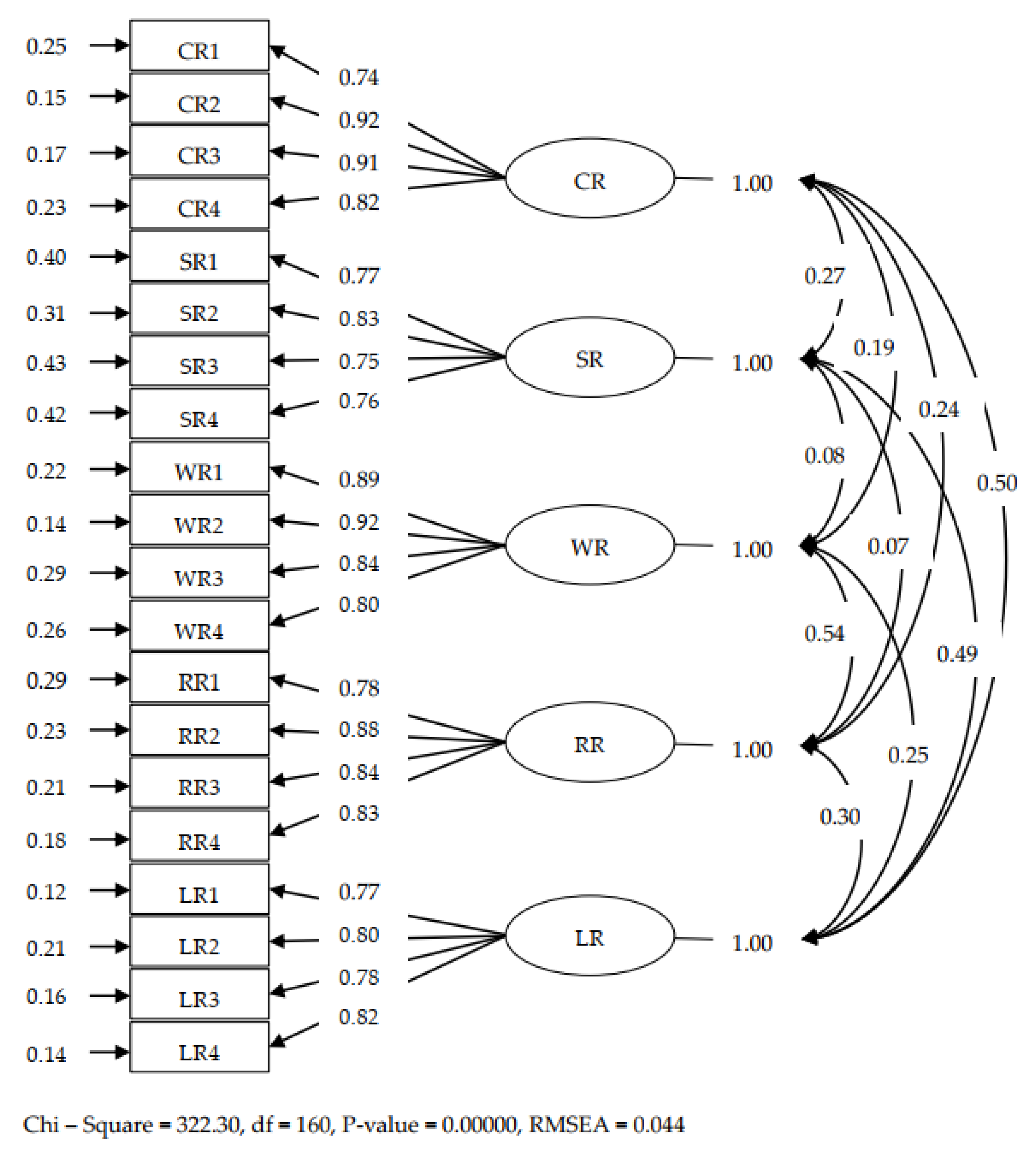

5.2.4. Validation Factor Analysis

In this study, after refining the measurement items of the organizational resilience scale based on exploratory factor analysis, the obtained scale was subjected to validated factor analysis using the LISREL 8.7 software. As seen in Table 12, the latent variable measurement models were χ2/df = 2.01 < 5, CFI = 0.99 > 0.9, NNFI = 0.98 > 0.9, and RMSEA = 0.044 < 0.1, all of which reached the desired range. Therefore, the model fit of this study is good.

Table 12.

Validated factor analysis of for the organizational resilience scale.

Meanwhile, as shown in Figure 2, the path coefficients of the latent variables corresponding to all the prior variables were above 0.7, and there were significant correlation coefficients among the five latent variables (as shown in Table 13). Thus, the measurement items for organizational resilience developed in this study responded well to the five latent variables and have high reliability and validity.

Figure 2.

Organizational resilience validated by factor analysis (CFA). Note: CR stands for capital resilience; SR stands for strategic resilience; WR stands for cultural resilience; RR stands for relationship resilience; and LR stands for learning resilience.

Table 13.

Correlation coefficient of each variable in descriptive statistics.

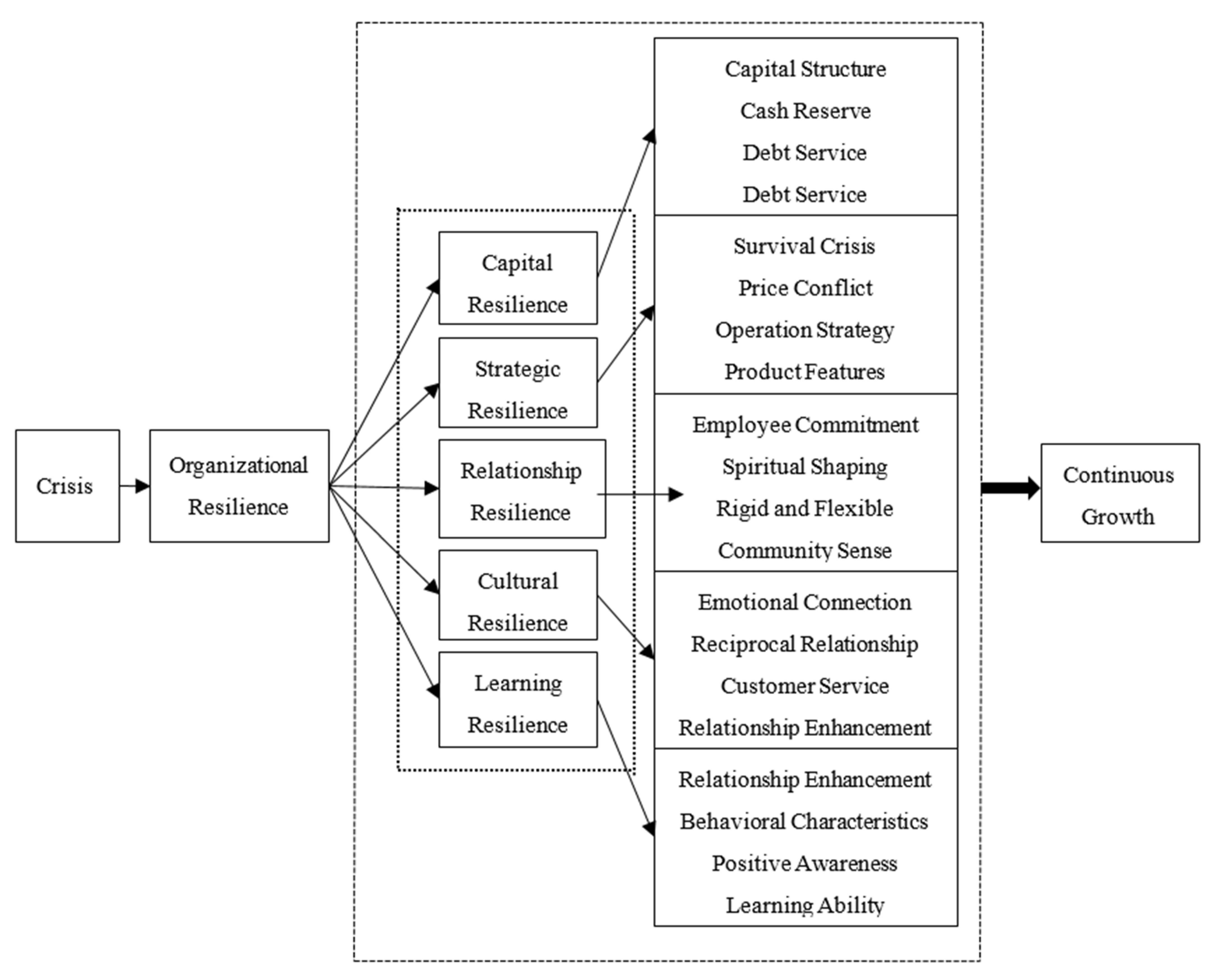

6. Conclusions and Discussion

6.1. Conclusions

With the development of the digital economy, the environment in which organizations operate is increasingly volatile. Survival and growth in a dynamic environment are central goals for organizations. Therefore, the importance of organizational resilience is recognized by both scholars and practitioners. This study analyzed six highly resilient companies, namely Southwest Airlines, Apple, Microsoft, Starbucks, Kyocera, and Lego. We provided an in-depth study of the dimensions and measurement components of organizational resilience. We have also clarified the process of organizational response to crises (as shown in Figure 3). First, this study clarified the concept of organizational resilience. Specifically, organizational resilience refers to the ability of an organization to reconfigure organizational resources, optimize organizational processes, reshape organizational relationships in a crisis, recover quickly from the crisis, and use the crisis to achieve counter-trend growth. Second, we specified five dimensions of organizational resilience: capital resilience, strategic resilience, relationship resilience, cultural resilience, and relationship resilience. Capital resilience refers to a company’s ability to operate normally and to recapitalize against risk in a crisis. Strategic resilience refers to a company’s ability to maintain strategic consistency over time, helping it to identify and eliminate adverse factors and to be able to choose an appropriate growth model. Relational resilience refers to the reciprocal relationships established between a company and its stakeholders. Cultural resilience refers to the way in which the corporate culture shapes the entrepreneurial spirit of employees and the commitment of the employees to the organization. Learning resilience refers to a company’s ability to cope with the stresses and challenges of learning. Finally, this study underwent a process of exploratory factor analysis and validation factor analysis to develop a 20-item scale for measuring organizational resilience.

Figure 3.

The organizational resilience process.

6.2. Discussion and Practical Implications

Compared to previous studies that measured organizational resilience, this study pioneered the use of a multi-case analysis approach. We drew on procedural rooting theory to obtain five dimensions of organizational resilience, which both complement and build on existing research. Previous studies found that organizational resilience is a multidimensional construct [27,41,42], which our study also validated. Scholars have argued that organizational resilience contains organizational learning and organizational resource dimensions [37,38,44]. Our study found that organizational resilience contains learning resilience and capital resilience. Learning plays an important role in organizations’ response to crises by enhancing their organizational capabilities [101]. Moreover, organizational resources can reduce organizational vulnerability and increase organizational resistance to the effects of crises [43]. It has also been noted that the idle resources that organizations have play an important role in providing flexibility and enhancing the organization’s ability to cope with crises [102,103,104]. Thus, learning resilience and capital resilience are important components of organizational resilience. Scholars have focused on the important role of relationships in organizational resilience [40,86,87]. Our study found that organizational resilience encompasses relationship resilience, which corroborates these studies’ findings. We also found that organizational resilience also includes strategic resilience and cultural resilience by conducting case studies of companies such as Southwest Airlines, which is a useful supplement to existing organizational resilience research.

A practical implication of this study is that building organizational resilience and accumulating corporate resilience assets does not happen overnight, but requires both time and a long-term strategic design, detailed planning, and effective measures. First, we need to implement a lean strategy to build strategic resilience. On the one hand, it is important for companies to have an ambitious vision and mission. The vision and mission of a company play an important role in its strategy and goals, and a common vision facilitates the growth of the company and paves the way for its future development. On the other hand, it is important for companies to set clear development goals and shape core competencies to match them. An ambitious vision and corporate mission help guide employees to focus on long-term development, while clear development goals help motivate organizational members and promote efficient synergy and mutual support within the organization. The matching of organizational members’ competencies with organizational goals helps to discover the impact of organizational members’ competencies on organizational goals.

Second, companies need to practice sound capital to shape capital resilience. Companies need to maintain adequate cash flow. Crises are unpredictable, so companies must be prepared before they arrive, and they need to determine the appropriate cash reserves based on the use of working capital. It is also necessary to control the level of capital leverage of the company. In the event of a crisis, companies with high capital leverage often find it difficult to cope with crises. It is necessary for them to adopt a sound financial strategy in the development process and keep their capital leverage within a reasonable range.

Third, it is important to practice reciprocal relationships to build relationship resilience. Higher relational resilience helps companies form strong cohesion with employees, customers, and investors when a crisis hits, thus, helping companies emerge from the crisis. Moreover, we want to take employees as the main body, so that employees and enterprises constitute a community of interests. Employees are one of the most important resources of the enterprise and the main body of enterprise value creation. Therefore, cultivating the organizational loyalty of employees and retaining them helps the enterprise enhance the dedication and cohesion of employees. As customers are the cornerstone of enterprise development, establishing a strong relationship between enterprises and customers can help enterprises overcome crises.

Fourth, we need to implement a culture of excellence to build cultural resilience. A resilient organizational culture is conducive to shaping a sense of community among organizational members, which can help organizations survive crises. At the same time, a relaxed organizational climate is more conducive to good organizational performance [105]. On the one hand, we should focus on caring and happiness. Caring for employees is good for employees to experience the feeling of home, which will motivate them to work harder to help the company cope with crises. Happy experiences can make the organization members have passion and can enhance the efficiency of the organization members. On the other hand, it is important to shape the commitment of organization members. Committed employees are conducive to the harmonious and stable development of the company.

However, as an exploratory study, this study still has some shortcomings. First, organizational resilience is a multidimensional structure, and the differences in industries may give different characteristics to organizational resilience. The samples selected for this study are mainly from the fields of technology, service, and manufacturing. Therefore, the structure of organizational resilience in other industries still needs to be further explored. Second, although Chinese scholars have measured organizational resilience, their research results have been integrated on the basis of existing studies. Fewer studies have explored the structure of organizational resilience from the perspective of multiple case studies. Although this current study has developed a scale for measuring organizational resilience, the crises faced by companies are constantly changing with the changes in the business environment and with the development of digital technology. The structure and measurement of organizational resilience may become more enriched and mature in the future as the external environment changes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C. and Y.X.; methodology, Y.L.; validation, Y.L. and R.C.; formal analysis, Y.X.; investigation, R.C.; resources, R.C. and Y.X.; data curation, R.C.; writing—Original draft preparation, R.C.; writing—Review and editing, Y.L.; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, Y.L. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 16AGL004; 2019 Youth Project of Fujian Province Social Science Planning, grant number FJ2019C031.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their reviews and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Duchek, S.; Raetze, S.; Scheuch, I. The role of diversity in organizational resilience: A theoretical framework. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 387–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, P. Crisis Management. Political Insight 2012, 3, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, A.; Boyer, M. Firm governance and organizational resiliency in a crisis context: A case study of a small research-based venture enterprise. Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Nonino, F. Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. Omega 2016, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Anten, N.P.; van Dixhoorn, I.D.; Feindt, P.H.; Kramer, K.; Leemans, R.; Sukkel, W. Why we need resilience thinking to meet societal challenges in bio-based production systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 23, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, I.P.; Collard, M.; Johnson, M. Adaptive organizational resilience: An evolutionary perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 28, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.M.M.; Sustains, O.R.H.L. Organizational Resilience. How Learning Sustains Organizations in Crisis, Disaster, and Breakdown by D. Christopher Kayes Juan Manuel Menéndez Blanco. Learn. Organ. 2018, 25, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, G.; Valikangas, L. The quest for resilience. Icade Rev. Fac. Derecho Cienc. Económicas Empresariales 2004, 62, 355–358. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D.M. Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty, 2nd ed.; Weick, K.E., Sutcliffe, K.M., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007; 194p, ISBN 978-0-7879-9649-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sawalha, I.H.S. Managing adversity: Understanding some dimensions of organizational resilience. Manag. Res. Rev. 2015, 38, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, S. Measuring resilience potential: An adaptive strategy for organizational crisis planning. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2009, 17, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deevy, E. Creating the Resilient Organization: A Rapid Response Management Program; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mallak, L. Putting organizational resilience to work. Ind. Manag. 1998, 40, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Balu, R. How to bounce back from setbacks. Fast Co. 2001, 45, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Coutu, D.L. How resilience works. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Vogus, T.J. Organizing for resilience. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E. Beyond bouncing back: The concept of organizational resilience. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Management Meetings, Seattle, WA, USA, 3–6 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S.F.; Hirschhorn, L.; Maltz, M. Organization resilience and moral purpose: Sandler O’Neill and partners in the aftermath of 9/11/01. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Management Meetings, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–26 October 2004; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jamrog, J.J.; McCann, J.E.I.; Lee, J.M.; Morrison, C.L.; Selsky, J.W.; Vickers, M. Agility and Resilience in the Face of Continuous Change; American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Vogelgesang, G.R.; Lester, P.B. Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2006, 5, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.; Griffiths, A. Beyond adaptation: Resilience for business in light of climate change and weather extremes. Bus. Soc. 2010, 49, 477–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riolli, L.; Savicki, V. Information system organizational resilience. Omega 2003, 31, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaah, M.; Amoako-Gyampah, K.; Jayaram, J. Resilience in family and nonfamily firms: An examination of the relationships between manufacturing strategy, competitive strategy and firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5527–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Wei, Y.; Li, X.; Lin, L. What Dimension of CSR Matters to Organizational Resilience? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerfel, M.L.; Lai, C.H.; Chewning, L.V. The evolutionary role of interorganizational communication: Modeling social capital in disaster contexts. Hum. Commun. Res. 2010, 36, 125–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chewning, L.V.; Lai, C.H.; Doerfel, M.L. Organizational resilience and using information and communication technologies to rebuild communication structures. Manag. Commun. Q. 2013, 27, 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffi-Hofstetter, H.; Mannheim, B. Managers’ coping resources, perceived organizational patterns, and responses during organizational recovery from decline. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.G. The importance of being resilient: Psychological well-being, job autonomy, and self-esteem of organization managers. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 155, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, W.L.; Lee, M.; Lim, W.S. The relational activation of resilience model: How leadership activates resilience in an organizational crisis. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2017, 25, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, L.; Harrison, W.; Jones, J.R.; Reiter-Palmon, R. Leadership behaviors and subordinate resilience. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2005, 11, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.S.; Stagl, K.C.; Salas, E.; Pierce, L.; Kendall, D. Understanding team adaptation: A conceptual analysis and model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1189–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, D.P. A theory of culture-switching: Leadership and red-tape during hurricane Katrina. Public Adm. 2012, 90, 851–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Van Eeten, M.J. The resilient organization. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S.; Seville, E.; Vargo, J.; Brunsdon, D. Facilitated process for improving organizational resilience. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2008, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.V.; Vargo, J.; Seville, E. Developing a tool to measure and compare organizations’ resilience. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2013, 14, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välikangas, L. The Resilient Organization: How Adaptive Cultures Thrive even when Strategy Fails; McGraw Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marsick, V.J.; Watkins, K.E. From the Learning Organization to Learning Communities toward a Learning Society; ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education, Center on Education and Training for Employment, College of Education, The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2000; pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kantur, D.; Say, A.I. Measuring organizational resilience: A scale development. J. Bus. Econ. Financ. 2015, 4, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogus, T.J.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Organizational resilience: Towards a theory and research agenda. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–10 October 2007; pp. 3418–3422. [Google Scholar]

- Umoh, G.I.; Amah, E.; Wokocha, H.I. Management development and organizational resilience: A case study of some selected manufacturing firms in Rivers State, Nigeria. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 16, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, K.; Bhamra, R.; Tsinopoulos, C. Building organizational resilience: Four configurations. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2018, 65, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A.; Winn, M. Extreme weather events and the critical importance of anticipatory adaptation and organizational resilience in responding to impacts. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, I.; Amah, E. Knowledge management and organizational resilience in Nigerian manufacturing organizations. Dev. Ctry. Stud. 2013, 3, 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Patriarca, R.; Bergström, J.; Di Gravio, G.; Costantino, F. Resilience engineering: Current status of the research and future challenges. Saf. Sci. 2018, 102, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petak, Z. Political Economy of the Croatian Devolution. In Proceedings of the Institutional Analysis and Development Mini-Conference, Bloomington, Indiana, 13–16 December 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildavsky, A.B. Searching for Safety; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1988; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, T.; Cäker, M.; Tengblad, S.; Wickelgren, M. Building traits for organizational resilience through balancing organizational structures. Scand. J. Manag. 2019, 35, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, T.J. Urban resilience and the recovery of New Orleans. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendra, J.M.; Wachtendorf, T. Elements of resilience after the world trade center disaster: Reconstituting New York City’s Emergency Operations Centre. Disasters 2003, 27, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comfort, L.K.; Sungu, Y.; Johnson, D.; Dunn, M. Complex systems in crisis: Anticipation and resilience in dynamic environments. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2001, 9, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.; Peck, H. Building the Resilient Supply Chain. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2004, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 628–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, K.J. Conceptualizing and measuring organizational and community resilience: Lessons from the emergency response following the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center. In Proceedings of the Third Comparative Workshop on Urban Earthquake Disaster Management, Kobe, Japan, 18–20 January 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Johnston, D. Disasters and communities: Vulnerability, resilience and preparedness. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2001, 10, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, A.W.; Williams, E.A. A dynamic model of organizational resilience: Adaptive and anchored approaches. Editor. Advis. Board 2018, 23, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Xiao, L.; Yin, J. Toward a dynamic model of organizational resilience. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2018, 9, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebjamnia, N.; Torabi, S.A.; Mansouri, S.A. Building organizational resilience in the face of multiple disruptions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 197, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sincorá, L.A.; Oliveira, M.P.V.D.; Zanquetto-Filho, H.; Ladeira, M.B. Business analytics leveraging resilience in organizational processes. RAUSP Manag. J. 2018, 53, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, P.; Filo, K.; Cuskelly, G. Organizational resilience of community sport clubs impacted by natural disasters. J. Sport Manag. 2013, 27, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koronis, E.; Ponis, S. Better than before: The resilient organization in crisis mode. J. Bus. Strategy 2018, 39, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Jung, K.; Chilton, K. Strategies of social media use in disaster management. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2016, 5, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N.; Bansal, P. The long-term benefits of organizational resilience through sustainable business practices. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafabi, S.; Munene, J.C.; Ahiauzu, A. Creative climate and organisational resilience: The mediating role of innovation. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2015, 23, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E. Resilience Capacity and Strategic Agility: Prerequisites for Thriving in a Dynamic Environment; UTSA, College of Business: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2009; pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.; Toder, F. A model of organizational recovery. J. Emerg. Manag. 2004, 2, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J.H.; Cameron, K.; Lim, S.; Rivas, V. Relationships, layoffs, and organizational resilience: Airline industry responses to September 11. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2006, 42, 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K. Prepare your organization to fight fires. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Borekci, D.; Rofcanin, Y.; Sahin, M. Effects of organizational culture and organizational resilience over subcontractor riskiness. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Von Winterfeldt, D. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Song, M. Linking emergency management networks to disaster resilience: Bonding and bridging strategy in hierarchical or horizontal collaboration networks. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1465–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, J.N.; Jung, K.; Andrew, S.A. Does transformational leadership build resilient public and nonprofit organizations? Disaster Prev. Manag. 2015, 24, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richtnér, A.; Löfsten, H. Managing in turbulence: How the capacity for resilience influences creativity. RD Manag. 2014, 44, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A. Benchmarking Organizational Resilience: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Research Study; New Jersey City University: Jersey City, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Girish, P.; Mesbahuddin, C.; Samuel, S. Organizational resilience and financial performance. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, A. Benchmarking the Resilience of Organizations. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rahi, K. Indicators to assess organizational resilience–a review of empirical literature. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2019, 10, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsick, V.J.; Watkins, K.E.; Wilson, J.A. Informal and incidental learning in the new millennium: The challenge of being rapid and/or being accurate. In Individual Differences and Development in Organizations; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Colding, J.; Berkes, F. Synthesis: Building resilience and adaptive capacity in social-ecological systems. Navig. Soc. Ecol. Syst. Build. Resil. Complex. Chang. 2003, 9, 352–387. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassop, L. The three R’s of resilience: Redundancy, requisite variety and resources. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Complexity and Organizational Resilience, Pohnpei, Micronesia, 24–25 May 2007; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, S.; Seville, E.; Brunsden, D.; Vargo, J. Resilience management: A framework for assessing and improving the resilience of organisations. In A Framework for Assessing and Improving the Resilience of Organisations; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnet, M.T. Employee Behaviors, Beliefs, and Collective Resilience: An Exploratory Study in Organizational Resilience capacity. Ph.D. Thesis, Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, M.; Kim, B.I.; Gang, K. Competition, product line length, and firm survival: Evidence from the US printer industry. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 29, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, D.P.; Blacksmith, N.; Coats, M.R.; Severt, J.B.; DeCostanza, A.H. The effect of adaptive organizational culture on long-term survival. J. Bus. Psychol. 2016, 31, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón, M.; Koller, T. Exploring adaptability in organizations; where adaptive advantage comes from and 450 what it is based upon. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2016, 29, 837–854. [Google Scholar]

- Şengül, H.; Marşan, D.; Gün, T. Survey assessment of organizational resiliency potential of a group of Seveso organizations in Turkey. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2019, 233, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnington, B.D.; Meehan, J.; Scanlon, T. A grounded theory of value dissonance in strategic relationships. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2016, 22, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Grounded theory methodology. Handb. Qual. Res. 1994, 17, 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J.M. Grounded Theory in Practice; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, E.; Cronin, B. Knowledge management: Semantic drift or conceptual shift? J. Educ. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2000, 41, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meen, D.E.; Keough, M. Creating the learning organization. Mckinsey Q. 1992, 1, 58–79. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, D.R.; Mishra, A.K. Toward a theory of organizational culture and effectiveness. Organ. Sci. 1995, 6, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Newton, L.A.; Thornton III, G.C. Job and organizational attitudes in relation to employee behavioral intentions. J. Organ. Behav. 1990, 11, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R. Computing Intraclass Correlations (ICC) as Estimates of Interrater Reliability in SPSS. Winnower 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan L, L.; Idris, N. Validity and reliability of the instrument using exploratory factor analysis and Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 400–410. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Granlund, M.; Zhao, Y.; Hwang, A.; Kang, L.; Huus, K. Transcultural adaptation, content validity and reliability of the instrument ‘Picture My Participation’for children and youth with and without intellectual disabilities in mainland China. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 28, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, H.; Wills, D.R. Product assembly and distribution optimization in an agribusiness cooperative. Interfaces 1983, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, P.R. An Historical Case Study of Organizational Resiliency within the Arellano-Felix Drug Trafficking Organization. Ph.D. Thesis, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay, P.; Glick, W.H.; Huber, G.P. Organizational actions in response to threats and opportunities. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 937–955. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A.D. Adapting to environmental jolts. Adm. Sci. Q. 1982, 27, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohria, N.; Gulati, R. Is slack good or bad for innovation? Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1245–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacci, I.; Mazzitelli, A.; Morea, D. Evaluating Climate between Working Excellence and Organizational Innovation: What Comes First? Sustainability 2020, 12, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).