The Contribution of Peripheral Large Scientific Infrastructures to Sustainable Development from a Global and Territorial Perspective: The Case of IFMIF-DONES

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The environmental impacts and the demand for natural resources must be limited.

- (2)

- Productive models must be based on technology allowing sustainable processes.

- (3)

- Sustainable Development requires organizational structures that must be adapted accordingly.

2. IFMIF-DONES: The Key Milestone toward the Use of Fusion Energy

2.1. The Situation with Nuclear Power

2.2. IFMIF-DONES: What It Is and How It Will Work

- (1)

- Particle accelerator, where deuterons (nuclei of hydrogen with one proton and one neutron) will be accelerated to very high speed. In the second phase, two parallel accelerators will work simultaneously.

- (2)

- Liquid lithium target, where the accelerated deuterons will impact producing nuclear reactions whose product are neutrons with the same energy as those created in fusion.

- (3)

- Test module, where different materials will be placed and irradiated with the neutrons.

2.3. The Situation of IFMIF-DONES: Current Development of the Project

3. Effects of Peripheral Large Scientific Infrastructures on Social and Territorial Sustainability

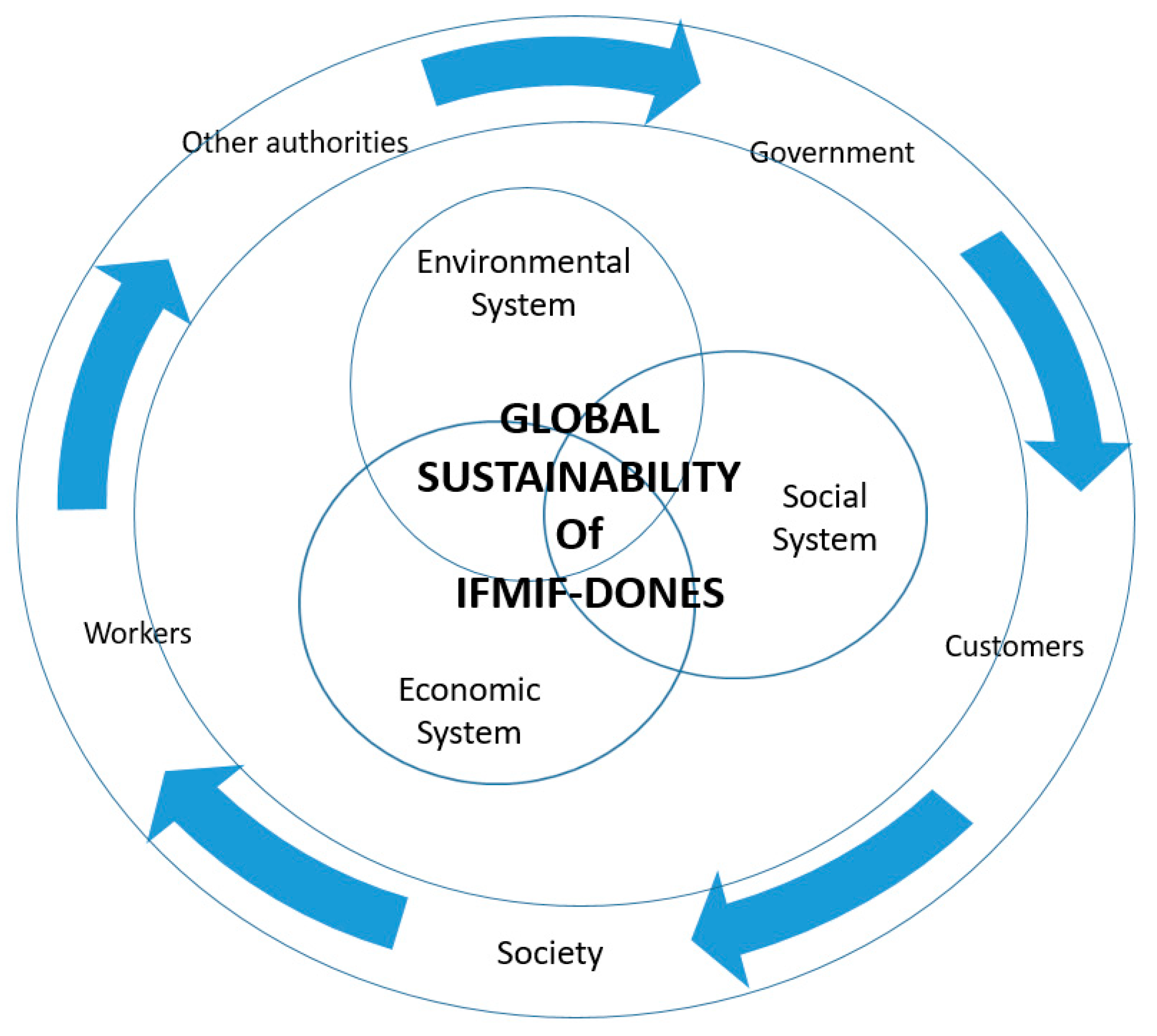

4. The Overall Impact of IFMIF-DONES at Different Levels

- (1)

- Global level: Given that the expected output of IFMIF-DONES will be the decision about the most suitable materials to construct the future fusion reactors, its impact at the global level will be to permit the development of fusion energy, which is expected to have a very high efficiency producing energy from non-hazardous fuels.

- (2)

- European Union level: The EU is one of the parts of the Broader Approach with Japan. This treaty is the framework toward fusion energy, where the EU has put a large amount of funds over the years. Furthermore, the major part of the funds financing IFMIF-DONES come from European programs like EUROfusion, ESFRI and, mainly, the European Regional Development Fund (EFDR). Therefore, the successful construction and operation of IFMIF-DONES will be a success for the European scientific policy.

- (3)

- National level: The expected location for IFMIF-DONES is in the South of Spain. The Spanish Government has managed all the different eventualities in order to successfully become the European candidate to host the Project. Furthermore, the Spanish Government is dedicating a remarkable part of its EFDR to fund IFMIF-DONES, which demonstrates a clear willingness. In this scenario, the increase in the number of contracts and the attraction of highly specialized construction and technological enterprises are a very worthy output of the project for Spain. Furthermore, the rise of Spanish research centers in important indicators and rankings like Shangai and others is another attractor and motor for progress.

- (4)

- Regional level: The Regional Government of Andalusia is carrying out the first investments of the project implementation at 50% with the Central Government. The origin of these funds is mainly the EFDR with some additional investment from its own budget. The expected impact will be also financial and scientific, but there is one particularity: the IFMIF-DONES project can become the needed boost for the shift of a mainly tourism-based economy to a knowledge-based one.

- (5)

- Local impact: Given the particularities of the territory where IFMIF-DONES is expected to be built and developed, it is necessary to enter in more details.

- (1)

- High dependence on agriculture, tourism, construction and its related areas (hotels, bars, restaurants, etc.) (REF: Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. Explotación de la Encuesta de Población Activa del INE.2020-3er trimestre. Thousands people).

- (2)

- Low rate of industrialization and big companies (industrial production index 90,1 and yearly variation −14,1).

- (3)

- Big cultural gap between young and older people. Whilst most young people have studied at a university, most people above 60 have not even got undergraduate formation.

- (4)

- An outstanding university, the fourth largest in Spain, with more than 60,000 students and 7000 professors, researchers and administrative staff [10]. It is at the top of Shangai ranking in some disciplines [12]. In addition, there are a few top research centers mainly linked to the university, but few job opportunities for their graduates.

- (5)

- Few but good hospitals. Some of them at the highest national level in some specialties.

- (6)

- High rates of unemployment (Granada: 108,100 unemployed, unemployment rate 25,94%; Andalusia: 932,300 unemployed, unemployment rate 23,80%).

- (1)

- Implementation of new high-technology private companies and stimulation of existing ones to work as suppliers during construction and operation of the facility.

- (2)

- Stimulation of regional construction companies.

- (3)

- Creation of highly qualified jobs for local graduates and additional jobs of services for non-graduate local workers currently in unemployment.

- (4)

- Creation of new lines of research complementary to the ones of the University and the research centers in the area.

- (5)

- Improvement of auxiliary infrastructures.

5. The Impact of IFMIF-DONES on Social Sustainability and SDGs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals (DSDG). Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/ (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Henriques, A.; Richardson, J. The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up? Assessing the Sustainability of Business and CSR; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cardillo, E.; Longo, M.C. Managerial Reporting Tools for Social Sustainability: Insights from a Local Government Experience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Moreno, V.; Leyva-Díaz, J.C.; Sánchez-Molina, J.; Peña-García, A. Proposal to foster sustainability through circular economy-based engineering: A profitable chain from waste management to tunnel lighting. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso-Orzáez, M.J.; Lozano-Miralles, J.A.; Lopez-Garcia, R.; Brito, P. Environmental criteria for assessing the competitiveness of public tenders with the replacement of large-scale LEDs in the outdoor lighting of cities as a key element for sustainable development: A case study applied with PROMETHEE methodology. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Accounting for the triple bottom line. Meas. Bus. Excell. 1998, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, A.; Salata, F. The perspective of Total Lighting as a key factor to increase the Sustainability of strategic activities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanish Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge. Available online: https://energia.gob.es/nuclear/Centrales/Espana/Paginas/CentralesEspana.aspx (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Available online: https://www.iter.org/proj/inafewlines (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Levy, N. Taking Responsibility for Responsibility. Public Health Ethics 2019, 12, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torjman, S. The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development, a Paper Prepared for Commissioner of Environment and Sustainable Development; Caledon Institute of Social Policy: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.; Matos, S.; Sheehan, L.; Silvestre, B. Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the Base of the Pyramid: A Recipe for Inclusive Growth or Social Exclusion? J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, K.J. Designing sustainable work systems: The need for a systems approach. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, M.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Broman, G. A Strategic Approach to Social Sustainability—Part 2: A Principle-Based Definition. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 140, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Hawke Research Institute Working Paper Series No 27; University of South Australia: Magill, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Polese, M.; Stren, R. The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Geibler, J.; Liedtke, C.; Wallbaum, H.; Schaller, S. Accounting for the Social Dimension of Sustainability: Experiences from the Biotechnology Industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, F.A.; Stevenson, M.; Zorzini, M. Social sustainability in developing country suppliers. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 610–638. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgreen, A.; Antioco, M.; Harness, D.; van Sloot, R. Purchasing and Marketing of Social and Environmental Sustainability for High-Tech Medical Equipment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Dillard, J.; Marshall, R.S. Triple Bottom Line: A Business Metaphor for a Social Construct; School of Business Administration, Portland State University: Portland, OR, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vavik, T.; Keitsch, M. Exploring relationships between Universal Design and Social Sustainable Development: Some Methodological Aspects to the Debate on the Sciences of Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, M. Reimagining urbanism. In Creative, Smart and Green Cities for the Changing Times; List Lab: Trento, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, G.; Li, F.; Tang, L. Multidisciplinary perspectives on sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2011, 18, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramanpouri, A.; Lamit, H.; Sedaghatnia, S. Urban Social Sustainability Trends in Research Literature. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingaertner, C.; Moberg, Å. Exploring social sustainability: Learning from perspectives on urban development and companies and products. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, L.; Poelzer, G.A.; Ejdemo, T.; Klyuchnikova, E.; Korchak, E.; Nygaard, V. Social sustainability innorthern mining communities: A study of the European North and Northwest Russia. Resour. Policy 2016, 47, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, R.V.; Klotz, L.E. Social Sustainability Considerations during Planning and Design: Framework of Processes for Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsko, C.; Marino, E.; Doherty, T.; Fisher, S.; Goodwin, B.; Green, A.; Reese, R.; Wirth, A. Systems of Access: A Multidisciplinary Strategy for Assessing the Social Dimensions of Sustainability. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2016, 12, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SDG | |

|---|---|

| 1 | No Poverty |

| 2 | Zero Hunger |

| 3 | Good Health and Well-being |

| 4 | Quality Education |

| 5 | Gender Equality |

| 6 | Clean Water and Sanitation |

| 7 | Affordable and Clean Energy |

| 8 | Decent Work and Economic Growth |

| 9 | Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure |

| 10 | Reduced Inequality |

| 11 | Sustainable Cities and Communities |

| 12 | Responsible Consumption and Production |

| 13 | Climate Action |

| 14 | Life Below Water |

| 15 | Life on Land |

| 16 | Peace and Justice Strong Institutions |

| 17 | Partnerships to Achieve the Goal |

| Granada | Escúzar | |

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 232,462 | 791 |

| Population under 20 years old (%) | 18.3 | 17.7 |

| Relative increase in population in 10 years | −0.8 | −4.7 |

| Public infrastructures | 155 schools, 10 libraries, 21 medical centers, 1 public university. | 1 school, 2 nurseries, 1 medical center. |

| Economy | Wide variety of services: 22,917 businesses with economic activity and 13,406 places to host (tourism). Some agriculture and industry. | Mainly agriculture. Recently, some industry. |

| Rate of unemployment | 23.2 | 23.8 |

| THREATS | OPPORTUNITIES |

|

|

| WEAKNESS | STRENGTHS |

|

|

| Topics on Social Sustainability | Promotion of Social Sustainability IFMIF-DONES | Promotion of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) |

|---|---|---|

| Human health and well-being/well-being of generations | The ultimate goal of IFMIF-DONES is to provide the keys to build fusion reactors that will produce clean energy, avoiding the emission of pollutants and greenhouse gasses and their negative effects on the health and well-being of present and future generations. | Goal 3 |

| Basic needs and quality of life | The expected shift from the primary sector to highly qualified jobs will mean higher incomes and better heritage in the economy and better quality of life. | Goals 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 and 8 |

| Social Coherence | IFMIF-DONES is in agreement with the recent attempt from regional, national and European levels to transform the region into a digital green-economy-based one. | Goals 1, 4, 5 and 10 |

| Social justice and equity | Goals 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 | |

| Democratic/engaged government and democratic society | ||

| Human rights | ||

| Social inclusion | More opportunities for everyone. Access to more opportunities for disadvantaged classes. | Goals 1, 4 and 5 |

| Diversity | The region of Escúzar will pass from a closed structure formed by several families (around 700 inhabitants) to a more heterogeneous one due to the move of foreign engineers and workers of the facility. | Goals 5 and 10 |

| Decline of poverty | ||

| Social infrastructure | The infrastructures complementary to IFMIF-DONES (roads, telecom, new schools) are expected to be remarkable. | Goal 9 |

| Social capital | The social capital of the original population of Escúzar will be enriched. More open-minded perspectives of life and formation will be brought with new visitors and inhabitants. | Goal 11 |

| Behavioral changes | The shift to a new productive framework and the arrival of people from other countries to the region will bring behavioral changes. | Goals 5, 10, 12 and 13 |

| Preservation of socio-cultural patterns and practices | The abovementioned changes can in no way cause the disappearance of the socio-cultural patterns and practices of the original population. The necessary bodies and practices for cultural preservation must be created and fostered. | Goals 4, 10 and 11 |

| Participation (including stakeholder participation) | The local and regional institutions will have a strong and permanent presence and participation in all the aspects of the DONES environment. | Goal 16 |

| Human dignity | ||

| Safety and security | Better infrastructures, safer roads, etc. | Goal 9 |

| Sense of place and belonging | Regional pride of one infrastructure that will be a key milestone toward nuclear fusion will undoubtedly reinforce the sense of place and belonging. | |

| Education and training | More schools and more international students will be a challenge for education and training, which will be improved. | Goal 4 |

| Employment | Many workers, qualified and not qualified, will be needed and hired during several decades. | Goal 8 |

| Community involvement and development, community resilience | One of the main targets of the University of Granada, as an implementing body of the project, is community involvement. For this reason, continuous activities to communicate to the community what is being done are being carried out. | Goal 16 |

| Fair operating practices | The final target is the decrease in uncontrolled energy consumption and emission of hazardous substances. Therefore, IFMIF-DONES will result in fair operating practices in industry, transport and other key activities. | Goals 12, 13, 14 and 15 |

| Capacity for learning | The activities of the University of Granada result in deeper know-how in scientific and operational terms based on continuous retrofit. | Goal 4 |

| No structural obstacles (to health, influence, competence, impartiality and meaning-making) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Pérez, V.; Peña-García, A. The Contribution of Peripheral Large Scientific Infrastructures to Sustainable Development from a Global and Territorial Perspective: The Case of IFMIF-DONES. Sustainability 2021, 13, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020454

Fernández-Pérez V, Peña-García A. The Contribution of Peripheral Large Scientific Infrastructures to Sustainable Development from a Global and Territorial Perspective: The Case of IFMIF-DONES. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020454

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Pérez, Virginia, and Antonio Peña-García. 2021. "The Contribution of Peripheral Large Scientific Infrastructures to Sustainable Development from a Global and Territorial Perspective: The Case of IFMIF-DONES" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020454

APA StyleFernández-Pérez, V., & Peña-García, A. (2021). The Contribution of Peripheral Large Scientific Infrastructures to Sustainable Development from a Global and Territorial Perspective: The Case of IFMIF-DONES. Sustainability, 13(2), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020454