Abstract

Within sustainability development paradigms, state governance is considered important in interventions to address risks produced by the industrial society. However, there is largely a lack of understanding, especially in the Global South, about the nature and workings of the governance institutions necessary to tackle risks effectively. Reflexive governance, as a new mode of governance, has been developed as a way to be more inclusive and more reflexive and respond to complex risks. Conversely, there is limited scholarly work that has examined the theoretical and empirical foundations of this governance approach, especially how it may unfold in the Global South. This paper explores the conditions and constrains for reflexive governance in a particular case: that of the South Durban Industrial Basin. South Durban is one of the most polluted regions in southern Africa and has been the most active industrial site of contention between local residents and industry and government during apartheid and into the new democracy. Empirical analysis found a number of constrains involved in enabling reflexive governance. It also found that a close alliance between government and industry to promote economic development has overshadowed social and environmental protection. Reflexive governance practitioners need to be cognisant of its applicability across diverse geographic settings and beyond western notions of reflexive governance.

1. Introduction

The urgent need for sustainable development raises issues of governance, since sustainability goals are subjected to heterogeneous perceptions and interest [1]. To reach necessary transformative change, there is a need to both properly understand this situation as well as find ways to manage it that are both politically legitimate and relevent to the environment. Although new modes of governance, such as reflexive governance, can increase participation and deliberation across industry, government and civil society sectors, thereby providing more legitimate decision-making, there is limited scholarly work that has examined the theoretical and empirical foundations of this assumption [2], let alone in the Global South. This includes the structures, power relations and actions that may hinder the emergence of reflexive governance [3]. There is apprehension about the political implications of reflexive governance since its designs engage with real-world political contexts, which affect their workings and may weaken their efficiency. Additionally, there may also be worries caused by the democratic legitimacy of reflexive governance designs and the uncertain relationships with establishments of representative democracy [4]. There are further concerns that reflexive governance emerged from the 1990s and developed in an era in which neoliberalism was the dominant political discourse, with repeated efforts to reduce the power of the nation state in favour of industry’s self-regulation [5]. Swyngedouw and Kaika (2014) and Dagkas and Tsoukala (2011) note that neo-liberalisation makes it difficult for vulnerable groups to have equal access to good-quality environmental resources, and for procedural quality in decision-making to occur [6,7]. However, linked to neoliberalism, Rosenau notes that government institutions can evolve in such a way as to be minimally dependent on hierarchical, command-based arrangements (i.e., industrial deregulation and self-regulation; loss of governance functions by the state) [8]. Nevertheless, the point of this paper is not to engage in complex debates about the ills of neoliberalism or to provide solutions to neoliberalism. The authors believe that the solutions to neoliberalism must evolve through genuine discussions between civil society, government and industry on moving towards sustainable development. As Luna (2015) states, the movement away from neoliberalism is about having a discussion about the kind of development we want for our future, how basic needs will be secured for everyone, moving away from inequality and how these goals will be achieved [9]. However, there is no doubt that reflexive governance will be important in these discussions, and there is a need to investigate how reflexive governance may be strengthened.

Reflexive governance may face a number of challenges such as how to treat and deal with the state’s power, responsibility, boundaries, the withering manner of the state, the problem between state management and state governance, and the problem of long-term coexistence and positive interaction between state and society, etc. [4,10]. Modern approaches to reflexive governance may thus aspire technocratic approaches to governance, which give rise to institutions that yield instability, whilst ignoring environmental externality impacts [11] and lack the capacity to co-ordinate collective action due to non-hierarchical forms of governance [12]. The question is whether reflexive governance may be a hybrid mode of governance, interpenetrated by other modes, or if it exists alongside and/or in competition with them [13]. Reflexive governance is, therefore, not straightforward and involves managing a plethora of contestations over sustainability and acknowledging that legitimacy is negotiated [14]. Limited research has explicitly investigated the potential for reflexivity to assist in understanding the politics of human–environmental impacts [11] and how reflexive governance unfolds or may potentially spiral into poor governance and risk ignoring or fragmenting divergent views [12] with reflexivity as one of the tenets of reflexive governance [15]. A major shortcoming of the existing literature on reflexivity is that the distinction between what reflexive governance is and what enables and/or hinders it is unclear [11]. If neoliberalism may influence reflexive governance approaches, then how may reflexive governance principles be safeguarded to ensure that they do not spiral into a technocratic approach or become paternalistic, thereby perpetuating risks?

Within this context, the aim of this paper is to explore the conditions and constrains of reflexive governance. Of particular importance is to examine the application of reflexive governance, its political implications, and shortcomings in terms of addressing industrial risks, using the case of the South Durban Industrial Basin (SDIB) in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Whilst there is largely a lack of understanding, especially in the Global South, about the nature and workings of the governance institutions necessary to tackle risks effectively, and which Southern countries exhibit different and perhaps more severe technical, financial and capacity constraints to Northern countries, it is important to explore the applicability of reflexive governance across diverse geographic settings, especially at the local level. As Guay also highlights, the connections between local governments and global processes receive limited attention in the political economy, despite local governance forays into the foreign policy realm having important implications for governance and policy-making generally [16]. The SDIB is considered to be one of the most contaminated regions in southern Africa and is declared a pollution hotspot. This will include how the state manages the plethora of contestations regarding risks. The geographic setting of local communities which have been historically exposed to petrochemical industries and industrial risks has not transformed since the introduction of democracy [17], making it of interest to investigate to what extent, and in what way, reflexive governance approaches has been employed. This paper consists of seven sections, including this introduction. The Section 2 provides some background to South Africa and reflexive governance. The Section 3 explores the literature on reflexive governance, participation and deliberative democracy. The section also outlines supplementary approaches to reflexive governance, such as ‘value reflexive governance’ and ‘ecological reflexivity’ approaches. The Section 4 explores the literature on an ‘enabling’ reflexive governance approach. The Section 5 outlines the study, the case description, the empirical material and the applied method. The Section 6 presents the results. The Section 7, which is the conclusion, evaluates the findings in relation to the literature and discusses the wider implications for an enabling a reflexive governance approach.

2. South Africa and Reflexive Governance

South African achieved democracy in 1994, an era when neoliberal ideology was globally dominant [18,19], and during a period when reflexive governance emerged. As a newly democratised nation, and in line with reflexive governance principles, the country developed a democratic constitution and a democratic parliament. For example, the 1996 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa makes provisions for the right to a healthy environment. It also bestows the right to have the environment protected by the government, who must prevent pollution and degradation, and ensure ecological sustainable development. It makes provisions for the participation of citizens in decision-making processes, democracy and accountability, the separation of powers and cooperative governance, and the decentralization of power [20]. Various policies and regulations have also been developed in line with the constitution to reduce and eliminate environmental and social risks in society. An example is the 1998 National Waste Management Strategy (NWMS), designed to ensure the good health of the people and the quality of the environment by the implementation of ‘cleaner production’ to increase the eco-efficiency of industrial processes, as well as to implement ‘cleaner technologies’ to reduce pollution and industrial risks in society [21]. The 1998 National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) emphasises that people’s needs must be put at the forefront when matters of environmental management are considered, and makes provisions for the promotion of the participation of all interested and affected parties in environmental governance [22]. ‘Reflexive governance’ approaches to deliberation and participation between a variety of stakeholders has, therefore, been considered critical for implementing processes to address societal risks, with civil society considered an important aspect of the new, inclusive ‘democratic’ societies. These act to ensure the human right to a healthy and just environment. Since its establishment of democracy, South Africa has implemented regulations that provide guiding principles for a ‘reflexive governance’ approach to an inclusive society so as to increase participation and deliberation between the government, industry and civil society.

Unfortunately, despite the progress in enabling the supportive governance policy frameworks and the values to preventing and managing environmental risk, the implementation of reflexive governance principles has been limited [23]. As Malherbe and Segal (2001) note, although South African legislation has attempted to sharpen corporate accountability for corporate actions post-1994, government institutions have not actively and publicly monitored corporate governance [24]. Due to the government engaging in a macro-economic neoliberal model since its democracy, it has concentrated on expanding industrial modes of production [25,26,27], with the logic of wealth production dominating the logic of risk alleviation, which contributes to increased industrial risks in society [28]. The state has also recognised, to some degree, its own incapacity to regulate effectively, with enforcement being inadequate or mechanistic, addressing the tail end rather than holistic approaches to address industrial risks. This has stifled technological innovation, stressing supply-side solutions rather than behavioural change on the part of industry [29]. Additionally, the anti-apartheid struggle should have impressed on the new government the need to incorporate citizens’ interests into decision-making processes; however, participation mechanisms have not enhanced participatory governance. Participatory mechanisms have been biased towards citizens with the capacity and resources to organise, who would be able to bring their concerns to government attention without these mechanisms [30]. Despite the general literature on state governance deficiencies, there is a lack of empirical evidence on how reflexive governance may be obstructed towards addressing industrial risks.

3. Reflexive Governance, Participation and Deliberative Democracy

The concept of reflexivity arose due to the industrial society producing unforeseen and unintended side effects as a result of an unlimited faith in science, bureaucracy and instrumental rationality [11,13,31,32,33]. In Beck’s periodization of social change, simple modernity is associated with the development of industrial society, whilst the new, reflexive modernity is associated with the emergence of the risk society, in which progress can turn into self-destruction [24,31]. Fuelled by technical disasters, the scientific capacity to determine risks and propose viable ways to handle them has been questioned [34,35], as well as industrial expertise [15] concerning its interest and ability to shape structural change in society and technology [1]. Within the sustainability development paradigms, state governance is, therefore, considered important in interventions to address unintended side effects and manage risks. The theory of reflexive modernization does not include the demise of the state, which simultaneously remains both the agent and the subject of change. Although aspects of the nation-state have been undermined, the nation-state still retains a considerable role in the governance process. ‘Governance’, in turn, is recast as a mechanism for managing today’s pervasive uncertainty. Reflexive modernisation allows for the recasting of ‘governance’ as a necessary, yet contingent, mechanism of managing uncertainty in contemporary societies [36].

Although ‘governance’ has diverse interpretations [37,38], modern approaches to governance are generally understood as the inclusion of the non-state stakeholders in decision-making [39,40,41,42] and emphasis of accountability, transparency, fairness, rule of law and ethical considerations by the state [13,43], whilst not relying on technocratic and bureaucratic processes to manage developmental and policy processes [1,29,44]. This collective understanding of modern governance can be grouped together under reflexive governance [4]. Reflexive governance, as a new mode of governance, is viewed as organising a response to the risks by replacing traditional, hierarchical and deterministic governance approaches with more reflexive, flexible and interactive ones, which draw on diverse knowledge systems [2,12,13,45]. Despite this understanding of reflexive governance, there is largely a lack of understanding about the nature and workings of the governance institutions that are necessary to effectively enable reflexive governance in society, so as to tackle industrial risks [3,46,47].

Participation and deliberation are central to reflexive governance and democracy, and to tackling development challenges [3], with reflexivity also associated with the principle of participation [14]. The concepts of governance and participation are interrelated, as governance is difficult to achieve if participation is insufficient. An essential component of good governance is the ability to enable citizens to express their views, and to act on those views, facilitated through participation [48]; the more deliberate the process, the more reflexive governance is [3]. When in-depth information is not disseminated to citizens, participatory and deliberation mechanisms may be ineffective [49]. Formal participatory assemblies may sometimes be geared towards ‘domesticating’ and undermining the legitimacy of groups who choose to engage critically with local governments (and industry). This has the potential to revert back to ‘first generation’ governance (i.e., traditional state-centred and technocratic regulation) and move away from the actual principles and values of reflexive governance.

For example, Wesselink et al. (2011) noted that impediments to participation may occur when environmental policies are not aligned with other policies and when economic interests prevail over environmental issues. Thus, ‘participation fatigue’ can occur, which is the failed embedding of new participatory governance in a bureaucratic structure that is not receptive to input from other stakeholders (e.g., civil society) [44]. To work towards sustainable development, the encouragement of knowledge inputs and participation from across society is not just an instrumental imperative, but an ethical imperative, since it is only on the basis of interactive governance that it is possible to elaborate a development trajectory that reflects the fundamental needs of society at large [14]. When linking reflexive governance with ‘deliberative democracy’, participants can debate the various issues in a careful and reasonable fashion for democratic legitimacy to occur. Only after genuine discussions occur, can decisions be made. In this sense, the deliberative aspect corresponds to a collective process of reflection and analysis, permeated by the discourse that precedes the decision. However, despite the principles of interactive governance within a reflexive governance approach, there is no guarantee that government (or industry) will genuinely apply these principles.

Therefore, it is important to distinguish between genuine processes of participation and deliberation, as opposed to more tokenistic ones. It is useful to draw on the ladder of participation, as presented by Arnstein (1969), which is still useful in understanding the different types of participation. These are grouped into ‘non-participation’, ‘tokenism’, and ‘citizen power’. With ‘non-participation’ (i.e., manipulation and therapy), the objective is to gain support for decisions which are already made. ‘Tokenism’, namely, informing, consultation and placation, allows citizens to express their views but with no assurance that citizens’ concerns will be taken into account. ‘Citizen power’ (namely, partnership, delegated power and citizen control) results in an increase in citizens’ decision-making powers. ‘Partnerships’ allow for power to be equally shared among citizens and power-holders. Regarding ‘citizen control’, Arnstein notes that, although citizens demand a degree of power (for example, governing of a program or institution), a Model City cannot meet the criteria of citizen control, since final approval power rests with the city authority. Nevertheless, citizen empowerment suggests that direct democracy (the participation of citizens in decision-making) needs to be established on a ‘partnership’ basis, with citizens treated as equal partners in development and decision-making processes [50].

4. Towards an ‘Enabling’ Reflexive Governance Approach

Reflexive governance, under the auspices of the ‘next generation’ environmental regulations, has been proposed as a means to overcome various insufficiencies associated with the ‘first generation’ environmental regulation linked with direct command and control state regulation and failure to nurture contextualised learning [2,4]. In relation to the ‘old’ and ‘new’ modes of governance, it is useful to draw on the various distinctions of governance, as noted by Stirling (2006) [51], which refer to unreflective, reflective and reflexive governance approaches. Unreflective governance denotes limited instrumental driven decision-making processes, whilst reflective governance involves more critical attempts to manage side effects and garner a multitude of perspectives to implement the best policy. Reflexive governance is about engaging with a variety of social actors, rather than eliminating ambivalence [2,14,52]. It seeks to explore how ambivalence is incorporated into reflexive approaches through governance, with participatory processes of various forms widely advocated to understand social change [4,52]. This is, in most instances, geared towards the construction of collective and consensual visions of what a more sustainable socio-technical system might entail [53]. Reflexive governance emphasises the participatory approaches in goal formulation and strategies of development for governance [54]. Since ambivalences of sustainability are emergent, reflexive governance is assumed to have the distinct feature of continually monitoring, feeding back and adjusting as a means of handling these interdependencies and the unpredictability of systemic change [52].

Considering that reflexive governance may become compromised within a neoliberal and bureaucratic framework, how can reflexive governance be robustly implemented and safeguarded? A clearer and enabling conception of reflexive governance can be facilitated through concepts such as ‘value reflexive governance’ and ‘ecological reflexivity’. The idea is not to posit one concept over the other, but rather to have them work together, since they are based on particular values. Meisch et al. (2012) notes that, as opposed to reflective governance, ‘value reflexive governance’ emphasises the values of good governance norms, where values become the guiding imperatives, which offer more transparent and inclusive governance by not only making it imperative for more social actors to express their values, but ensuring that those values materialise into actions [55]. According to Smith and Stirling (2007), reflexive governance is also about social actors changing values in response to scrutiny [56]. Meisch et al. (2012) states that value reflexive governance is sensitive to participants’ values in governance processes and develops specific solutions to problems. Unfortunately, there is no set of particular philosophical tools to guide value discourses, and there are diverse social and institutional contexts which maybe unique to particular environments [55]. Reflecting on ways to develop procedural arrangements that work with power and conflict, to ensure inclusive participation, equality among participants and open communication in a process of experimentation and learning, is necessary to cope with ambivalence [4].

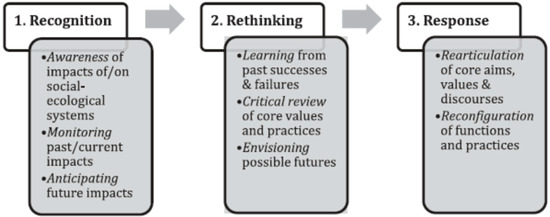

According to Weiland (2012), there is a need to collectively develop the instruments and procedures that allow for the productive use of diversity. It seems that deliberation between all social actors is key to ensuring the development of the ‘value’ instruments and procedures for enabling reflexive governance [12]. It is also important to explore what determines reflexive governance. As Meadowcroft and Steurer (2018) note, reflexive governance is not straightforward [14]. As highlighted, modern approaches to reflexive governance may spiral into technocratic approaches to governance and overlook environmental externality impacts. Pickering (2019) attempts to solve this problem by further proposing ‘ecological reflexivity’, understood as, ‘the capacity of an entity (for example, an agent, structure, or process) to recognise its impacts on social-ecological systems and vice-versa; rethink its core values and practices in this light, and respond accordingly by transforming its values and practices [11]. Therefore, this goes beyond policy processes initiated by government and moves from unconscious reaction to conscious and cognitive effort. Figure 1 shows the three components and their signs of ecological reflexivity. According to Pickering, in order to qualify as minimal reflexivity, institutions (for example, government and industry) must show all three components of reflexivity to some degree. This understanding can assist in detecting shortfalls in reflexivity and unveil non-reflexive or reflexive institutions. For example, an agent or structure will be considered non-reflexive if it recognises a problem and fails to rethink activities such as the government’s lack of enforcement of environmental regulations, leading to the continual pollution of society and the environment by industrial processes.

Figure 1.

Components and signs of ecological reflexivity: Source: Pickering (2019).

The combination of value-reflexive governance and ecological reflexivity in reflexive governance approaches can ensure that there is a more explicit emphasis on the formulation of participants’ values to formulate actions, and that all stakeholders can develop instruments and procedures that will enable the productive use of diversity with feedback on decisions made. Social actors are also enabled to recognise their impact on social-ecological systems and must be reflexive in rethinking practices, thereby transforming values and practices. Such an approach can entail more open, transparent and inclusive governance. As Meisch et al. (2012 notes, it is important that values are turned into actions by developing specific solutions to the problems enabled by the formulation of values, instruments and procedures [55]. The key, however, is that the participation and deliberation encouraged by the government ensures the decentralisation of power to citizens, so that all stakeholders have an equal chance to induce positive change [57] and ensure equity and fairness in the rule and application of law [38,43].

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. The Studied Case

The South Durban Industrial Basin (SDIB) in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa is considered one of the most contaminated regions in southern Africa. The SDIB is home to two of South Africa’s four oil refineries, Africa’s foremost chemical storage facility, and over 180 smokestack industries are located in the SDIB [58]. The region is an example of an industrial hub that includes residential areas situated next to heavy industries [18]. The apartheid impression to formulate a deliberate industrial region was efficaciously implemented by the early 1970s; this region became home to 70 percent of Durban’s industrial activity [59].

A brief background about South Durban is that in 1994, with the ushering in of democracy, the community established the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance (SDCEA) to tackle the issue of pollution within South Durban. (The SDCEA is made-up of 16 affiliate organisations and has been active since its formation. It makes no profit and exists solely for the benefit of the people it represents. The Alliance is vocal and active in lobbying, reporting and researching industrial incidents and accidents in South Durban [60].) According to Reid and D’Sa (2005), SDCEA was formed to link local concerns across racial boundaries in order to respond systematically to pollution issues [61]. As was the case during apartheid, South Durban communities continue to endure the environmental, health, and socio-economic costs of pollution from adjacent industries [18], with the most frequent perpetrators of atmospheric pollution incidents being the oil refineries, notably Engen Petroleum and the South African Petroleum Refinery (SAPREF) [60]. Health impacts in South Durban have been a concern, with asthma rates documented at double the global average [62], and the incidence of leukaemia noted to be up to 24 times higher than the national average [63]. A 2002 medical study carried out by a team of medical researchers at the local Settlers Primary School bordering the Engen refinery found that 52 percent of learners suffered from severe asthma, and 11 percent of learners experienced moderate to severe persistent asthma. It was further found that children in South Durban were much more likely to suffer from chest complaints than children from other parts of Durban [64]. The SDCEA also recorded a total of 55 major industrial incidents in South Durban from 2000 to 2016 [65,66]. In 2018, the South Durban basin was declared a pollution hotspot, according to the provincial government’s Environment Outlook Report [67].

5.2. Data Collection

For the qualitative research methodology employed for this study, primary material was collected by one of the authors in June and July 2019. Semi-structured interview guides were used to collect data from key social actors (namely, local government, external civil society scientific experts supporting community groups, local residents, and community-based organisations (CBOs)). A purposive sampling design was employed during fieldwork, where the researcher’s judgement determines who can provide the best information to achieve the objectives of the study. A snowballing technique was also employed, as informants referred the researcher to other informants for interview. A total of seven interviews were conducted, of which five interviews are reported in this study. One interview was secured with an anonymous local government official. Two interviews were secured with academics from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, dealing with health studies and industrial expansion in South Durban, respectively. One interview was secured with an ex-local government employee (now working in the water industry in the same area), who was previously responsible for air pollution in South Durban, and another interview was conducted with the SDCEA leadership. Unfortunately, numerous attempts to secure interviews with several major South Durban industries proved futile. Additionally, two key government officials directly responsible for pollution issues and air-quality monitoring in South Durban did not respond to interview invitations. This has implications for the data analysis, as the views of two important social actors have not been possible to obtain.

This paper also draws on fieldwork conducted in South Durban in July 2017, which explored governance as part of a study that looked at ‘toxic tourism’ for environmental justice [68]. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with several members of the local SDCEA involved with various environmental projects in South Durban, ranging from industrial pollution to climate change. From this study, two interviews are used that particularly concern governance issue.

Documents are used as secondary sources when necessary to identify relationships or patterns regarding the interview content and as a way to interrogate and verify what has been said. These include the 2007 South Durban Basin Multi-Point Plan (MPP) Case Study Report [69]; the 2017/2018 eThekwini Municipality Annual Report [70]; a 2019 Independent Online (IOL) media article [71]; the 2020 National Air Quality Indicator—Monthly data report [72]; a 2018 Mail and Guardian media article [73]; a 2019 Africa News Agency media article [74]; the 2018 South African Petroleum Industry Association (SAPIA) Annual Report [75]; and the 2018 Engen Refinery Integrated Report [76].

5.3. Data Analysis

For the data analysis, grounded theory and open coding were employed to identify similar emerging themes across the interviews (namely, scientific experts and co-creation of knowledge, risk communication, trust and transparency, participation, governance, civil society resources and fragmentation). Grounded theory and open coding primarily involve taking the data apart (i.e., interviews) and examining the parts for differences and similarities. Codes are clustered together to form categories (i.e., themes) [77]. This article focuses on two main themes (namely, poor governance skills and transparency when addressing industrial risks, and the lack of participatory governance and deliberation), which are discussed below. There are links and overlaps between the themes.

5.4. Informed Consent

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol for the 2019 field work was approved by the University of South Africa, College Research Ethics Committee (Project identification REC 170616-051). For the fieldwork of 2017, the ethical standards for academic research were followed. It was, however, not possible to obtain ethical clearance from the University of South Africa, because the study was based at another university which, at that time, had no ethics committee in place.

6. Results

In the following, we will analyse to what extent reflexive governance was applied to address the industrial risks in the SDIB. In particular, the hindrances in applying this approach will be investigated. This section presents two main themes (i.e., lack of governance skills and transparency to address industrial risks, and lack of participatory governance and deliberation).

6.1. Lack of Governance Skills and Transparency to Address Industrial Risks

Poor governance, since 2010, has resulted in the local government not maintaining air-monitoring equipment to collect air-quality data so as to address potential industrial risks in South Durban, as per the previous MPP. This, in turn, had implications for the government not sharing air-quality information with civil society in order to make informed decisions about industrial development issues, with implications for transparency within the new reflexive governance democratic dispensation. The MMP was launched after the dawn of democracy, in November 2000, and aimed to provide an improved and collective decision-making structure for air pollution management at the local government level, reduce air pollution to meet health-based air-quality standards, and improve the quality of life for the local community. Some of the key achievements of the MMP were an improved air-quality monitoring network with integrated data transfer and storage, the extension of sampling to other pollutants such as Benzene, Toluene, Ethyl-benzene and Xylene, and a reflexive government multi-stakeholder approach, with the government, community and industry working jointly [69]. The ex-government employee, Informant A, working for a water purification company in South Durban, who was previously employed as a local government official responsible for pollution control and programme manager of the previous MPP, noted the deterioration of governance in combatting industrial risks in South Durban since the MPP ended:

‘There have been gains and changes [to combat industrial risks since the turn of democracy] but I am a bit disappointed in the maintenance of that current domain … The Multi-Point Plan was funding from industry, funding from government and there was a true multi-stakeholder nature of a democratic government and industry coming on board and led by the top teams. The MPP delivered as it enabled the science to prevail with monitoring and good data and allowing a health study to take place. A first successful health study that is also documented and peer-reviewed. Industry started investing at that time millions of Rands [South African currency] to address pollution. So under the MPP we have seen pollution coming down to within levels and now it is best practice from industry … But what is disappointing and since I left government, there has been a disinterest [by local government] in maintaining the [air] monitoring stations … I complained [to local government] about an incident … and it took many weeks for them to respond, but an inadequate response … You have to look at the stakeholder approach to handle the issue, making sense of it to make a solution. So that is missing … They [government] will probably give you lots of excuses why things can’t happen … ’(Informant A, 19 June 2019).

The local SDCEA CBO further noted the lack of proper reflexive governance to maintain air-monitoring equipment in South Durban, including the lack of transparency and communication to civil society surrounding how the data were collected by the government. Informant B, a SDCEA Environmental Project Officer—responsible for Development, Infrastructure and Climate Change—noted for the lack of governance to monitor air pollution:

‘ … We have the city with the latest [air monitoring] equipment … that will give you [an] exact reading of what’s emitted out [by industry] and what volume. [It has been] non-functional since 2013, yet to date, two, three weeks ago, they have claimed that no, we’ve only stopped receiving information from our monitoring stations from 2016. When we asked them about that, we didn’t know that and one of their [government] portfolio committee members in Johannesburg stated that they have not received any information to date since 2013. So, these are the key things that are displaying themselves in our communities and government is not acting on our behalf … ’(Informant B, 10 July 2017).

The above suggests an unreflective governance approach by the municipality in not organising a response to potential risks and not displaying accountability and transparency towards external stakeholders. In an article published by the Independent Online (IOL) media in 2019, it was reported that many civil society groups complained that local government had not supplied and engaged with them regarding air-pollution monitoring information for many years, as the monitoring stations were non-functional [71]. Reference to the National Air Quality Indicator Monthly data report for the KwaZulu Natal Province, April 2020 [72], stipulates that the 2004 National Air Quality Act requires the establishment of national standards for municipalities and provinces to monitor ambient air quality to report compliance with ambient air quality standards. To this end, different spheres of government have invested in continuous air-pollution monitoring hardware to meet this objective. The information secured from these stations is used to develop the National Air Quality Indicator (NAQI), based on an annual measure of prevalent pollutants. One of the purposes of the NAQI is to provide an evidence-based approach in presenting and measuring air-quality management interventions, and serves as a communication tool on air-quality matters, to be easily understood and used by the public.

However, the report notes that a number of monitoring stations are not fully operational, and government does not provide any indication as to why there have been delays indicating poor risk communication and transparency. The two monitoring stations located in South Durban (namely, Settlers (Merebank) and Wentworth Reservoir stations) were not fully operational, and recordings were only available for sulphur dioxide and particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), but not for other pollutants such as nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, nitrogen oxides, benzene, toluene and xylene. Therefore, civil society did not have the necessary information to make informed decisions and act on potential pollutants in the air, harmful to their health and wellbeing, as provided for in the South African Constitution, or to hold government and industry accountable. Although the government has recognised shortcomings in its ability to maintain and monitor air quality, it has failed to adopt principles of ecological reflexivity to rethink activities surrounding monitoring, enforcement and compliance, which have potentially led to the continual pollution of the South Durban community, indicating a non-reflexive local governance institution.

However, the unreflective governance was also due to the lack of technical skills within the local government. Although skills were transferred to the new government during the transition in 1994, with many civil society leaders moving into different state structures, with the relationship between the state and civil society organisations characterised by a collaborative nature [19], several civil society informants noted that the lack of the eThekwini government skills had deteriorated since 2010. Some of the previously trained government officials had left the government sector to work in industry, or had moved to other sectors. This created a technical void within the government to effectively deal with industry and enforce regulations. Informant C noted that the government did not have the capacity and skills to effectively govern South Durban:

‘Officials are not doing their job, we call them … and they go to the industry, they can’t read the information and the industry [then] tells them what to do and they [are] quite happy to believe that [as] they don’t have the technical expertise … There is also a cut back on qualified staff. They [local government] don’t employ people who have the experience. Most of the air quality officers that were employed and trained in Denmark and Norway, they have also left and are either working for ENGEN or SAPREF or [now in] consultancy or they are in New Zealand, Australia or other parts of the world … Since 2010, there has been a lack of credible data—the monitoring stations, fourteen of the most sophisticated and experienced stations has been allowed to decay and not work and not managed. So that is the problem … the environment has not become an important issue by government at all costs and yet they want to make development decisions when the equipment are not operating …. It is a lack of leadership.’[Informant C, 3 July 2019].

The above statement suggests that there is not necessarily a lack of employed government officials, but rather not enough qualified, technically skilled staff. A review of the eThekwini Municipality Annual Report, 2017/2018 [70], shows that of the forty-one Environmental Protection posts, only one was vacant. A researcher in the field of occupational and environmental health, who has worked very closely with the South Durban community on health studies and risk exposure since 2002, stated that the lack of government technical skills, including their poor engagement and deliberation with civil society, influenced the relationship between civil society and the government. Civil society was not able to secure information on industrial pollution, due to poor communication and a lack of transparency from local government. As the informant noted:

‘I definitely think that the skills set that they [local government] had around the MMP … has been lost. There is an attempt to build a new technical skills base and to be honest, I don’t know at this point, the levels of those individuals that are now there … But what has happened is that because of our repeated attempts to get this sort of information that we want, there has not been that sort of forthcoming sort of relationship. We [civil society] have tended to lose that link that we have had [with government] over that period of time … the air quality network … [which] has been substantially compromised so the type of data we were getting in the 2000s when we were doing the health study is not as good as what we are seeing now … It is local government who is supposed to maintain that [air quality stations] and run that and our sense is that there is a failing on government’s side… We have not been given clear reasons why these things are not working effectively’[Informant D, 20 June 2019].

6.2. Lack of Participatory Governance and Deliberation

Empirical analysis suggested that the government did not engage with reflexive governance principles by acknowledging the interpenetration of governance subjects and objects to engage more openly and directly with a variety of social actors to gather recursive feedback to understand social change. This governance approach was, therefore, divergent from the stated eThekwini Municipality city governance principles, as outlined in the eThekwini Municipality Annual Report, 2017/2018 [70]. The report highlights that some of the principles of good governance that the municipality demonstrates include ‘accountability’ as a ‘fundamental requirement of good governance’, and ‘transparency’, in that citizens should be able to follow and understand the decision-making process. Other principles outlined in the report include ‘equity and inclusiveness’, where community members ‘feel their interests have been considered in the decision-making processes’. However, these principles have not mirrored the practices of local government. A closer analysis of the local government’s ‘participatory’ governance principle suggests ‘tokenistic’ participatory approaches towards civil society. The local government’s annual report highlights its participatory governance approach as follows, ‘Anyone affected by or interested in a decision should have the opportunity to participate in the process of making that decision … Community members may be provided with information, asked for their opinion, given the opportunity to make recommendations or, in some cases, be part of the actual decision-making process’. This approach suggests that when information is provided, and citizens are asked for their opinion, citizens may not be included from the onset of the strategy formulation and are only included in the final decision-making processes in select cases. This governance approach is tantamount to Arnstein’s notion of top-down approach to governance by inviting citizens’ opinions (namely, consultation), and thus offers no assurance that citizens’ concerns will be taken into account [50]. It is also tantamount to ‘placation’, when citizens advise but local government retains the right to judge the legitimacy of the recommendations.

Poor reflective governance and a lack of government transparency regarding environmental risk information also influenced how civil society was able to meaningfully engage with local constituencies, government and industry to inform decisions. Informant D highlighted the lack of information from the government and how this compromised civil society actions regarding industrial risks:

‘In the 2000s when the pollution control unit was setup and run by [Informant A] … What is most important about that was their ability to make this information available on a short turnover basis. So, you could go to the website and you would know what was going on … With my engagement with the organisations representing civil society I would say … they don’t have the information [from local government now] that they need to take the necessary action or to engage with their stakeholders, the local communities. I think this is problematic. For example, for our birth cohort study—epidemiological study … we needed emissions data, the emissions inventory. Now according to all our legislation and Access to Information Act, this data is supposed to be available. It took us a very, very long time, in fact probably more than five years. We had written to them [local government], we quoted the act and they agreed to release it to us, and we have repeatedly found there to be a reluctance to release this information. They said well this is confidential information’[Informant D, 20 June 2019].

This indicates a bureaucratic government approach, whereby modern approaches to reflexive governance since democracy spiralled into technocratic approaches. Local government has not enabled a transparent and inclusive governance by allowing civil society to express their needs and concerns. Despite civil society expressing their need for information, and as stipulated by regulations, the local government did not engage in ecological reflexivity by reflecting on their practices and changing their values in response to scrutiny and development solutions. Nor did the government spearhead democratic deliberations with stakeholders as a form of open communication to address diverse opinions. It was furthermore suggested by one informant that the government might not be concerned with facilitating deliberative democracy and engagement between industry and affected communities to address industrial risks. It was noted by a local government official that it was not necessarily the city department’s responsibility to engage with local concerns and that there were local government structures in place to facilitate this engagement. However, this was not taking place due to politics, resulting in poor reflexive governance. According to a local government informant, namely, Informant E, there was a bias from government’s political representatives regarding engagement with communities:

‘It is not happening [local government bringing industry and communities together]... As local government, we have governance structures in place. We have our political reps, our ward councillors, who are the voice of the people and they should be doing that. They should be opening the channels of communication. They should be encouraging this. That is why SAPREF and the industries have included councillors in their forums so that they bring the voice of the people. That is tricky, councillors are supposed to have their community meetings. However, councillors will push the line of the people that support him or her because of politics. So, they will hear the voices of the people that support them, and the others may be seen as troublemakers or not so important.’[Informant E, 21 June 2019].

Thus, the local government municipality has not engaged in effective participation and deliberation with civil society but has relied on local councillors to bring the concerns of the people to the municipal council. However, councillors may be inaccessible to people. Generally, Durban councillors have been accused of not communicating effectively with their constituents [73].

Councils may also be prone to corruption. For example, four eThekwini Municipality councilors were arrested in 2019 on charges of fraud and corruption [74]. The above government informant also acknowledges that local councillors may have vested interests. This indicates that the government recognises flaws in its strategy of communication and deliberation with civil society but has not been reflexive in rethinking practices and how to better engage with citizens in order to transform values and practices. A more open, transparent and inclusive governance is required to enable value reflexive governance to enable action and find specific solutions to problems.

Local government has not engaged with civil society to develop the instruments and procedures that would allow for a broader input into development processes, and to create feedback on development decisions made. Informant A emphasised the harsh approach by local government in not setting up consultative forums and, therefore, not applying the regulations of the country that enable consultations with civil society:

‘Government can create spaces for people to come on board such as a forum, but it is not happening. Government is quite happy that it is not happening since they have less pressure on them. You have got the Constitution and all the regulations that say communities must be involved but they have not translated that into a modus-operandi to have a consultative forum … if you collecting air quality information where is the report and for the information to go public … Like the number of complaints, we have had for Mondi and SAPREF for the last year—what was the cause of that? How was it dealt with? Is it improving? The trends? So, you could be addressing social reporting’[Informant A, 19 June 2019].

Unfortunately, Informant D was less optimistic that the government would ensure proper consultation with civil society, due to the macro-economic development policies in the country, which drive business profits to the fore, at the expense of people and the environment. As the informant noted:

‘So, this sort of information about knowledge transfer and making sure people are aware, we have to make sure it works. I think in a way I say that, but I know deep down it is not going to happen … because it is such a divided society … Those that are empowered believe that they are doing good for society with this trickle down effort and you will eventually benefit from this so let us go on and do it. I personally don’t believe in that. It is breaking that barrier which is going to be a challenge. In a sense government is supposed to be the referee in this. They are supposed to say right, we are representing both stakeholders—we see the value in economic development, but we also see the impact on communities on civil society... But you don’t see that happening because government then gets taken in because these things [industrial development] represent an increase tax base. So, the vested interest start[s] to shift … ’[Informant D, 20 June 2019].

Some informants noted that this lack of transparency and participation from government was due to the close relationship between government and the industry for economic expansion and the industry making decisions for the government, especially with the latter not having the proper technical skills, as highlighted above. According to Informant C, the government has repeatedly made excuses for not releasing information because they work closely with industry, who control how government makes decisions:

‘They [government] say under the pretext that it [information] is confidential. How can information that affects your health be confidential? They supposed to be revealing the information. During the apartheid era we did not get the information so why is it now during a democratic government they do not give you the information? What is critical is that there is a lack of political will. Previously, the national government and provincial and local government [after the transition to democracy] made sure that you got hold of the permits, the scheduled permits, you got the information. The air emission licenses are the most progressive permits that are ever done coming out of Norway. In Norway and Denmark, you can go to the government and they give you [the information] straight away about the facility. Here you can’t get it and they won’t allow it because the industry controls the government … the folks that are working there [in local government] are too scare[d] to do their job for fear that the industry has got power and a lot of these politicians have got shares in these big companies … that is the major problem’[Informant C, 3 July 2019].

It would seem, then, that during the transition to democracy, there was a new deposition for the government to enable a reflexive form of governance; however, this has deteriorated over the last decade due to a lack of political will and loss of technical skills. Informant F, who is the Air Quality/GIS & Youth Development Officer at the SDCEA, also noted the lack of government transparency, as well as the close relationship between the government and industry, which influenced the lack of proper governance:

‘ … the very same authorities, they are not giving us information. From 2010 to date, information that you used to get over the counter with no questions asked, even if now you can be a student, you want data, air quality monitoring data; they are going to ask you 101 questions. But before, they used to just give you data. So, I think there is a lot of secrecy … You know the other biggest problem that we have seen is that, unfortunately authorities … [are] paving their greener pastures to go to industries. That is the unfortunate part. They always want to look good on the side of industries. They don’t want to be too harsh and too hard on industries.’[Informant F, 10 July 2017].

Due to the supposedly close relationship between government and industry, and lack of engagement from government towards civil society, some informants noted that major industries, such as the refineries, took advantage of this association and did not genuinely engage in participation with local civil society, since decisions on industrial development were already made (with government).

For example, the Engen Refinery Integrated Report, 2018 [76], noted that the industry strove to strengthen industry and government relationships by engaging on issues of mutual interest. Such engagements were noted to take place at Engen’s senior leadership level, represented by the Chief Executive Officer. The industry was also part of the SAPIA ‘to articulate and lobby the government to support the industry’s positions’. Unfortunately, these engagements were separate from community engagement. In addition, the government did not enable a collective platform to bring all stakeholders together. A review of the SAPIA (2018) Annual Report contained a foreword by the government Minister of Energy, noting that national government had set a target to attract USD 100 billion of investment into the South African economy, and that the energy sector could contribute to a quarter of this target, as a minimum.

Reflexive governance engagement with civil society seems to be constrained by political power dynamics and macro-economic growth. This may imply that the government (and industry) are not sincerely concerned about deliberative democracy and collective governance with civil society and development processes. An academic human geographer from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Informant G, researched social development in the area, and refers to the bureaucratic and tokenistic participation from the government (and industries) in the area as follows:

‘The big issue [in South Durban] is lack of public participation. When participation took place it was top down and tokenism and almost telling you this is how it is going to be, rather than asking you what do you want? So, what is known as one of the most toxic zones in the world, the Merebank, Wentworth Zone will become more toxic … ’[Informant F, 1 July 2019].

7. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper presented two main themes that emerged from grounded theory and coding of primary data. The first theme is the lack of governance skills and transparency and showed that poor governance, since 2010 and after the dismantling of the MPP, resulted in the local government not maintaining air-monitoring equipment to collect air-quality data to address potential industrial risks in South Durban. This has implications for the government not sharing air-quality information with civil society in order to make informed decisions about industrial development issues. This was a divergent approach from the previous MMP, launched after the dawn of democracy, which ran from 2000 to 2010, and resulted in improved air-quality monitoring and a reflexive government multi-stakeholder approach, with the government, community and industry working jointly. Since 2010, the lack of proper reflexive governance to maintain air-monitoring equipment has resulted in a lack of transparency and communication with civil society surrounding how the government collected the data. Although the government recognised shortcomings in its ability to maintain and monitor air quality, it failed to adopt principles of ecological reflexivity to rethink activities surrounding monitoring, enforcement and compliance, which potentially led to the continual pollution of the South Durban community, indicating a non-reflexive local governance institution. However, unreflective governance was also due to the lack of technical skills within the local government to effectively deal with industry and enforce regulations.

The second theme presented in the results surrounded the lack of participatory governance and deliberation. This showed that the government did not engage with reflexive governance principles by engaging transparently and directly with a variety of social actors to gather recursive feedback to understand social change. There were ‘tokenistic’ participatory approaches from the local government towards civil society, with the government retaining the right to judge the legitimacy of the recommendations put forward by civil society rather than engaging with them on an equal footing. Thus, poor reflective governance and a lack of government transparency on environmental risk information influenced how civil society was able to engage with local constituencies, government and industry to inform decisions. Modern approaches to reflexive governance since the establishment of democracy have spiraled into technocratic approaches. Local government did not view it as their responsibility to engage with local concerns, but the duty of inefficient local government structures to facilitate this engagement. Although government recognised flaws in its strategy of communication and deliberation with civil society, it was not reflexive in rethinking practices and how it better engaged with citizens. Some informants noted that a lack of transparency and participation from government was due to the close relationship between government and industry for economic expansions and due to industry dominating development decisions. Major industries took advantage of the close relationship with government and did not genuinely engage in participation with local civil society since industrial development decisions were already made with government. Thus, reflexive governance to engage with civil society was found to be constrained by political power dynamics and macro-economic growth.

Overall, this paper has shown that there are a number of constraints involved in enabling reflexive governance, particularly in terms of development and middle-upper-income countries such as South Africa. The country’s democratic transition has enabled the supportive governance policy frameworks and the overall guiding principle of reflexive governance values. The newly elected government has instituted a democratic constitution and developed various regulations to strengthen democracy and accountability, for example by ensuring the participation of civil society in many political issues. Despite this positive development, there has been a very restricted implementation of value reflexive policies, not least at the local government level. The analysis found three crucial reasons for this: lack of sufficient skills at the local governmental level, the local government’s reliance on technical experts from the industry, and the lack of platforms where government, industry and civil society can collectively deliberate on industrial risk issues.

Reflexive governance application in the South Durban political contexts had implications for its workings and efficiency. Civil society expressed uncertain relations with local government and questioned the democratic legitimacy of its value reflexive governance approaches. Poor reflexive governance was due to a lack of local government skills in maintaining air-monitoring equipment, and not addressing any potential industrial risks in South Durban. This, in turn, had implications for the government sharing air-quality information with civil society to make informed decisions about industrial development issues, with implications on participation and transparency. Although the government recognised shortcomings in its ability to maintain and monitor air quality, it failed to engage in ecological reflexivity and rethink activities surrounding monitoring, enforcement and compliance, indicating a non-reflexive local governance approach.

The government, as an enforcer of the law, relied on industry technical expertise, and thus spiralled into biased and technocratic approaches removed from the public. Some of the previously trained government officials left the government sector to work in industry or moved to other sectors. This created a technical void within the government to effectively deal with industry and enforce regulations. The eThekwini government skills have rapidly deteriorated since 2010, after the conclusion of the MPP, and thus weakened reflexive governance. These shortcomings have seriously hindered the way the government operates and engages with both civil society and industry and, hence, the implementation of reflective governance, the development of value reflective governance principles for engagement with civil society and industry, and the spearheading of ecological reflexivity to improve its operations and practices. These have had implications for upholding value reflexive governance principles outlined in the South African Constitution, including other environmental and governance policies and regulations.

The further failure of a value-reflexive governance and ecological reflexivity approach was that the local government did not engage with reflexive governance principles by creating platforms where the civil society, government and industry could openly communicate and make joint decisions, nor was the government concerned with gathering recursive feedback to understand social change. Therefore, this governance approach was divergent from the stated eThekwini Municipality city governance principles. This lack of engagement compromise civil society’s ability to meaningfully engage with local constituencies, government and industry to inform decisions. The municipality also relied on local councils to bring the concerns of the people to the municipal council. However, councillors were inaccessible to people or prone to corruption. A more open, transparent and inclusive governance approach is required to enable a value-reflexive governance approach to enable action and find specific solutions to problems. This will require the government to enable the appropriate deliberative platforms to jointly engage with civil society and industry to obtain a consensus surrounding the relevant instruments and procedures, which would allow for a broader input into development processes, and feedback on the development decisions made. At the present moment, this is absent and has enabled tokenistic participatory and communicative approaches towards civil society when presented.

The emerging democratic structure of South Africa creates opportunities to better handle industrial environmental risks. As shown in this paper, a reflexive governance approach has the potential to address these risks in a democratically sound and environmental relevant way. A prerequisite, however, is that the government gives priority and allocates resources to this approach. As this case study indicated, certain conditions need to be met. First of all, it requires that the government does not prioritise neoliberal profit driven by industrial motives at the expense of social and environmental concerns. Due to a governmental, neoliberal development paradigm, old modes of governance are still present and exercised within the framework of reflexive governance policy and principles. Secondly, this requires that the local government develop a sufficient technical capacity so that it may also be able to make informed development decisions, without relying on industrial expertise. Thirdly, it requires that the local government, as enforcer of the law, maintains a neutral approach by not being one-sidedly influenced by industrial interests, and by providing a platform for civil society to inform decisions. This will require that those employed within local government have the required skills and expertise and are able to make independent decisions surrounding industrial development.

Combining the value-reflexive governance and ecological reflexivity will foster the formulation of values and the development of the instruments and procedures that can better incorporate diverse opinions into development decisions. Thus, the local government must engage in ecological reflexivity by rethinking its practices and transforming how it currently enables reflexive governance. Such an approach will enable a stronger reflexive governance approach. However, the challenge is not only to build relevant local governance structures, but also to develop new interfaces between the government and society, and find a balance of power between stakeholders. Generally, this case from South Africa has highlighted that reflexive governance practitioners need to be cognisant of its applicability across diverse geographic settings and beyond western notions of reflexive governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and R.L.; methodology, L.L.; validation, R.L.; formal analysis, L.L. and R.L.; investigation, L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L. and R.L.; supervision, R.L.; project administration, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the College Ethics Committee) of the University of South Africa, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Newig, J.; Voß, J.; Monstadt, J. Editorial: Governance for Sustainable Development in the Face of Ambivalence, Uncertainty and Distributed Power: An Introduction. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K.; Kuyper, J.; Linnér, B.; Lövbrand, E. Non-state actors in global climate governance: From Copenhagen to Paris and beyond. Environ. Politics 2017, 26, 56–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.; Pickering, J. Deliberation as a catalyst for reflexive environmental governance. In Working Paper Series 3; Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Voß, J.-P.; Bornemann, B. The Politics of Reflexive Governance: Challenges for Designing Adaptive Management and Transition Management. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss2/art9/ (accessed on 2 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Gunningham, N. Regulatory reform and reflexive regulation: Beyond command and control. In Reflexive Governance for Global Public Goods, Politics, Science and the Environment; Brousseau, E., Dedeurwaerdere, T., Siebenhüner, B., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Kaika, M. Urban political ecology. Great promises, deadlock… and new beginnings? Doc. d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 2014, 60, 459–481. [Google Scholar]

- Dagkas, A.; Tsoukala, K. Civil society, identity, space and power in the neoliberal age in Latin America and Greece. Synergies 2011, 3, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenau, J.N. Governance, Order and Change in World Politics. In Governance without Government: Order and Change in World Politics; Rosenau, J.N., Czempiel, E.-O., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992; Chapter 1; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Luna, V. From Neoliberalism to Possible Alternatives. Inf. Econ. 2015, 395, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T. Confronting governance challenges of the resource nexus through reflexivity: A cross-case comparison of biofuels policies in Germany and Brazil. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J. Ecological reflexivity: Characterising an elusive virtue for governance in the Anthropocene. Environ. Politics 2019, 28, 1145–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, S. Reflexive governance: A way forward for coordinated natural resource policy? In Environmental Governance: The Challenge of Legitimacy and Effectiveness; Hogl, K., Kvarda, E., Nordbeck, R., Pregernig, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McNutt, K.; Rayner, J. Valuing Metaphor: A constructive account of reflexive governance in policy networks. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Interpretative Policy Analysis, Grenoble, France, 23–25 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcroft, J.; Steurer, R. Assessment practices in the policy and politics cycles: A contribution to reflexive governance for sustainable development. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2018, 20, 734–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M.; Lidskog, R.; Uggla, Y. A reflexive look at reflexivity in environmental sociology. Environ. Sociol. 2017, 3, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, T. Local Government and Global Politics: The Implications of Massachusetts’ “Burma Law”. Political Sci. Q. 2000, 115, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. Reconsidering the ‘risk society theory’ in the South. S. Afr. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 45, 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Maguranyanga, B. South African Environmental Justice Struggles against ‘Toxic’ Petrochemical Industries in South Durban. Available online: http://www.umich.edu/~snre492/brain.html (accessed on 17 March 2011).

- Leonard, L.; Pelling, M. Civil Society Response to Industrial Contamination of Groundwater in Durban, South Africa. Environ. Urban. 2010, 22, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Constitution. Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/images/a108-96.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- National Waste Management Strategy. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Republic of South Africa. Available online: http://www.polity.org.za/pol/acts/ (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- National Environmental Management Act, Act 107, Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Republic of South Africa. Available online: https://www.environment.co.za/documents/legislation/NEMA-National-Environmental-Management-Act-107-1998-G-19519.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Mathee, A. Environment and Health in South Africa. J. Public Health Policy 2011, 32, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malherbe, S.; Segal, N. Corporate Governance in South Africa. In Proceedings of the Policy Dialogue Meeting on Corporate Governance in Developing Countries and Emerging Economies, OECD Development Centre and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, OECD headquarters, Muldersdrift, South Africa, 23–24 April 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, R.; Habib, A.; Valodia, I.; Zuern, E. Globalization, marginalization and contemporary social movements in South Africa. J. Afr. Aff. 2005, 104, 615–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barchiesi, F. Classes, Multitudes and the Politics of Community Movements in Post-Apartheid South Africa; Centre for Civil Society Research: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Makino, K. Institutional conditions for social movements to engage in formal politics. In Protest and Social Movements in the Developing World; Shigetomi, S., Kumiko, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, L. Civil Society Reflexiveness in an Industrial Risk Society. Ph.D. Thesis, University of London (Kings College), London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fig, D. Manufacturing amnesia. Int. Aff. 2005, 81, 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S. Participatory Governance and Citizen Action in Post-Apartheid South Africa. In Discussion Paper Series No; International Institute for Labour Studies: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risk Society; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Giddens, A.; Lash, S. Reflexive Modernization; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, E.; Renn, O.; McCright, A. The Risk Society Revisited: Social Theory and Governance; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. The Metamorphosis of the World; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Visvizi, A. Safety, risk, governance and the Eurozone crisis: Rethinking the conceptual merits of ‘global safety governance’. In Essays on Global Safety Governance: Challenges and Solutions; Kłosińska-Dąbrowska, P., Ed.; University of Warsaw Publishing Programme: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kunseler, E. Revealing a paradox in scientific advice to governments. Palgrave Commun. 2016, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooiman, J.; Bavinck, M.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Mahon, R.; Pullin, R. Interactive Governance and Governability: An Introduction. J. Transdiscipl. Environ. Stud. 2008, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, D.; Goga, S. Natural Resource Governance Systems in South Africa. Water Research Commission; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016; Available online: http://www.wrc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/mdocs/WIN1_IWRM.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2020).

- Marissing, V.E. Citizen participation in the Netherlands Motives to involve citizens in planning processes. In Proceedings of the ENHR Conference ‘Housing: New Challenges and Innovations in Tomorrow’s Cities’, Reykjavik, Iceland, 29 June–3 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, P.; Hall, A.W. Effective Water Governance; Global Water Partnership Technical Committee, TEC Background Papers; Elanders: Mölndal, Sweden, 2003; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tembo, F. Participation, Negotiation, and Poverty: Encountering the Power of Images; Ashgate Publishing Company: Farnham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, D.; Amos, B.; Plumptre, T. Principles for Good Governance in the 21st Century. In Proceedings of the Fifth World Parks Congress, Durban, South Africa, 8–17 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wesselink, A.; Paavola, J.; Fritsch, O.; Renn, O. Rationales for public participation in environmental policy and governance: Practitioners’ perspectives. Environ. Plan. 2011, 43, 2688–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeijl-Rozema, A.; Cörvers, R.; Kemp, R. Governance for sustainable development: A framework. In Proceedings of the Earth System Governance: Theories and Strategies for Sustainability, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 24–26 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blowers, A. Environmental Policy: Ecological Modernisation or the Risk Society? Urban Stud. 1997, 34, 845–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L. Governance, participation and mining development. Politikon 2017, 44, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, R. Governing When Chaos Rules: Enhancing governance and participation. Wash. Q. 2002, 25, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, R.; Farhad, H.; Rees, C. Participation in Decentralized Local Governance: Two Contrasting Cases from the Philippines. Public Organ. Rev. 2007, 7, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, R.S. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A. Precaution, foresight, sustainability: Reflection and reflexivity in the governance of science and technology. In Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Voß, J.P., Bauknecht, D., Kemp, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 225–272. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, G.; Shove, E. Ambivalence, Sustainability and the Governance of Socio-Technical Transitions. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnino, R.; Torres, C.; Schneider, S. Reflexive governance for food security: The example of school feeding in Brazil. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]