Abstract

This paper presents findings from a study carried out as part of BigPicnic, a European Commission’s Horizon 2020 project. BigPicnic brought together members of the public, scientists, policy-makers and industry representatives to develop exhibitions and science cafés. Across 12 European and one Ugandan botanic gardens participating in the study, we surveyed 1189 respondents on factors and motives affecting their food choices. The study highlights the importance that cultural knowledge holds for understanding food choices and consumer preferences. The findings of this study are discussed in the wider context of food security issues related to sustainable food choice, and the role of food as a form of cultural heritage. Specifically, the findings underline the importance of the impact of food preferences and choices on achieving sustainability, but also indicate that heritage is a key parameter that has to be more explicitly considered in definitions of food security and relevant policies on a European and global level.

1. Introduction

This paper discusses the role of food as a form of cultural heritage and the importance that cultural knowledge holds for understanding food choices and consumer preferences, drawing on the insights gained from the BigPicnic project. This project (‘Big Picnic: Big Questions - Engaging the Public with Responsible Research and Innovation on Food Security’), funded by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme, aimed to address food security issues in the context of botanic garden education through linking up food security, climate change and plant diversity. Throughout its duration (May 2016–April 2019), exhibitions and science café events were developed through co-creation processes which engaged people from various target groups [1] and other educational activities which addressed food security issues across a wide range of themes. During the co-creation activities, an extensive program of qualitative studies was carried out. This showed that there is a range of motives people have when making food choices. Specifically, one of the key findings was that food culture and heritage is a door opener for fruitful discussions on the link between food security and sustainable development. Findings from these qualitative studies were used to design a survey study with the aim to collect data from visitors to the exhibitions, workshops and science cafés organised by 15 botanic gardens in 12 European and one African countries [2,3].

The major goal of the survey study was to find out how selected food choice motives identified through qualitative data were perceived by people living in a wide range of participating countries. By presenting the findings from this study, this paper aims to contribute to the current discussions surrounding sustainable food choices. We argue that a key element in this discussion is missing, namely food as cultural heritage, and that we need to understand the impact that environmental concerns, social context and food culture, as well as heritage, have on food choices. The outcomes of our research point to the importance of natural concerns, sociability and traditional eating as factors influencing what people choose to eat. Among the principal conclusions of this paper, however, is also the realization that heritage is a key parameter that is to a great extent omitted from both the key definition of food security and the associated European and global policy that deals with food and sustainable development.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 will place the study in a broader context highlighting the importance of food security and the adoption of sustainable food choices and underlining the growing importance of the notion of food heritage for addressing these issues. Section 3 describes the research methodology and methods employed in the BigPicnic project while Section 4 provides an overview of the survey data and discusses the links to findings from the qualitative studies. The discussion provides a summary of the main findings, reflects on the implications of the study results for international research and educational projects and contemplates the importance of better-disseminating food security research to policy-makers.

2. The Wider Context: Food Security Discourse, Food Choices and the Notion of Food Heritage

The findings of the BigPicnic project discussed in this paper raise interesting issues in the context of food security and point towards the importance of the growing recognition of the impact of food preferences and choices on achieving sustainability.

Food security is one of the greatest challenges facing society today. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): “food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life. The four pillars of food security are availability, access, utilization and stability. The nutritional dimension is integral to the concept of food security.” [4]. Nevertheless, food security is an umbrella concept and is interpreted differently in different countries. It is often emphasized that food security is context-specific and may mean different things to different people, in different spaces and times [5] (p. 153). Some countries do not even have an established term or an exactly synonymous word that corresponds to the Anglo-American term. Even among various fields of expertise, food security seems complicated, includes various perspectives and is subject to misconception and misunderstanding [6]. Food security has constituted a very common challenge throughout human history, but its discourses have evolved since the 1970 s in parallel with the global industrial food system [7,8,9]. Existing definitions of food security seem to focus on three key elements, namely access, sovereignty and safety.

Inevitably, food choices and preferences are directly linked to the current and future environmental problems. For example, climate change is increasingly recognized as an issue of global concern, while food production and consumption along with dietary choices have a major impact on its dynamics [10]. Around 10 to 12% of the global annual emissions of greenhouse gases and 75% of global deforestation come from agriculture [11]. Therefore, climate change is an issue that our food system must play a part in mitigating. Climate change has the potential to affect food security across a range of areas such as access to food, utilization and price stability [4].

It is increasingly important for the global society to both understand the concept of food security, but also to adopt behaviors that improve food security locally, regionally, and nationally through adopting sustainable ways of producing and consuming food. People from different communities have a different relationship to food and their food choices are impacted by their socio-economic and cultural background. Both formal and informal education play a major role in supporting people to make informed decisions when it comes to choosing food. Indeed, studies by psychologists have recently underlined the importance of investigating the motives for and functions of eating in everyday life in order to understand what constitutes ‘normal’ eating behavior [12] (p. 117). Human eating behavior is regulated by multiple motives and is a complex function of biological, learned, sociocultural, and economic factors [12] (p. 118). To this end, numerous food choice questionnaires have been employed in efforts to reveal these eating and food choice motives [12] (p. 118). Understanding why people adopt particular eating behaviors is important in order to develop educational programs which have the potential to support behavioral change.

Sociocultural parameters provide an interesting and important angle to the discussion of the topic of food preferences and food security. The FAO has been using four measurable and interrelated components (often referred to as pillars) to define food security: availability, access, utilization and stability [13] (p. 11). It is worth noting in this context that ‘food access’ is thought to be affected, among other things, by preference, which encompasses social, religious and cultural norms and values all of which can influence consumer demand for certain types of food [14] (p. 420). John Ingram has further stressed that social value is also an element for the ‘food utilization’ component as food also provides social, religious and cultural functions and benefits [14]. Maxwell and Smith have highlighted that cultural acceptability should also be considered as an important aspect within the food security concept as food contribute to the basic needs and well-being of people in ways that go far beyond nutritional adequacy [15] (pp. 39–41). Nevertheless, anthropologists studying food security through ethnography have criticized the lack of attention afforded to local cultural and social contexts from the part of the scientific community and the policy-makers [16].

Placing an emphasis, however, on the cultural and social role of food is not something entirely new. From the latter half of the 20th-century, food has been a topic of interest for anthropologists, sociologists, geographers (and scholars from various other disciplines) who have emphasized the social and cultural dimensions of eating and culinary traditions and the importance of studying alimentary cultures [17,18,19,20,21]. For example, researchers interested in the anthropology of food have addressed the role of food in poverty and welfare and have often offered expert advice to food corporations and to national or international development organizations [22]. Studies have focused on a variety of issues such as the environmental and social consequences of genetically modified organisms [5], the promotion of organic food [23], the negative impact of meat production and consumption [24], the impact of food consumption habits on climate change [25], the impact of supermarkets on consumers and consumption practices [26] and the threat of globalizing forces on traditional food cultures and practices [27], to name just a few. Methods such as the Food Consumption Scores (adopted by the United Nations World Food Program) for measuring food security have commonly been criticized because of their lack of attention to the complexities of historical context and local specific parameters [5] (pp. 153–154). Nevertheless, despite the emphasis on food as a cultural construction, some anthropologists have also underlined the benefits drawn from the insights of other disciplines such as nutrition science [28]. In terms of how people make choices about food, it has been pinpointed that ethical consumption is the result of a complex interplay between locally specific contexts and circumstances of food provision and various moral codes and political ideas [29].

Building on this body of work, the relatively recently emerged field of heritage studies and its widely expanding heritage discourse acknowledge that longstanding geographic, economic, social, and cosmological differences throughout the world define how and what people eat as well as when and with whom they eat [30] (p. 1). Eating food invokes memories, incites senses and emotions and offers experiences that bind people together through space and time [31], creating local, regional and national/ethnic identities and connecting the past with the present [30]. These elements render food a form of cultural heritage encompassing both tangible and intangible dimensions. Indeed, since UNESCO adopted the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003 [32], there has been a growing global awareness and recognition of the vital importance of intangible forms of heritage with food playing an increasingly significant role [30] (pp. 10–17).

Within this context, it is important to acknowledge that food as a form of heritage should play a more prominent role in how food security is defined and should be considered more carefully when policies dealing with food and sustainable development are formulated. Heritage is about supporting culinary traditions and acknowledging that they help to shape personal and collective identities. Efforts to address food security at the policy, organizational, individual or educational level should acknowledge the essential role that heritage plays in people’s lives. In particular, this should take into account the importance of food in relation to memory and the expression of identity and different religious, political and ethical values, as well as traditional ways of eating. These motives are currently underrepresented in policy papers and campaigns and this is a point to which we shall return in this paper (see Discussion). Thus, this study addresses the following research questions: Do people who participated in outreach activities offered by Botanic Gardens consider socio-cultural motives in food choice as important? Do people who participated in such activities in different countries and cultural settings respectively consider socio-cultural motives equally important?

Quite interestingly, an overarching theme highlighted by the co-creation sessions (exhibitions, science cafés and other activities) was the cultural heritage dimension of food and the central role food plays in developing and sustaining personal and collective identities. This acquired even more significance because food heritage was not the focal point of the BigPicnic project and some of our project partners even considered this an unexpected finding.

Qualitative data collected during pilot activities in the first phase of the Big Picnic project, as well as the research literature mentioned above, suggests the hypothesis that cultural background has an impact on how people answer questionnaire items addressing socio-cultural motives. For example, people with a migration background, who engaged in BigPicnic co-creation activities linked food to their culture and home country memories frequently. Thus, another hypothesis was that this pattern would appear in a larger sample as well.

3. Research Methodology and Methods

This paper presents findings of a quantitative survey that examined food choices and is part of a larger research study carried out as part of the BigPicnic project. Big Picnic was a collaboration between 19 international partners ranging from universities, botanic gardens, NGOs and professional bodies to an institute for art, science and technology (see Appendix A, Table A1). It brought together members of the public, scientists, policy-makers and industry representatives to develop exhibitions and science cafés (events in casual settings to encourage conversation and debate between scientists and the public on a particular topic). These were used to increase engagement and generate debate on local and global food security issues. It involved more than 100 science café events reaching 6000 participants as well as 100 outreach exhibitions attracting diverse audiences.

The BigPicnic botanical garden partners (henceforth BG Partners) carried out extensive applied research of their outreach exhibitions, science cafés and other co-creation activities [1,2,3]. The first phase of the research included a series of qualitative studies, which collected evidence from approximately 4500 participants. The second phase of the research involved a large-scale survey of 1189 respondents. Most of the questionnaires were collected at science cafés, exhibitions and a science communication event organised by the BG partners, inviting both experts and non-experts to participate. This survey was designed to complement the aforementioned qualitative study and is focused on food choices. This paper reports mainly on findings from the latter study. However, reference is also made to findings from the qualitative study, where relevant.

This survey conducted for the BigPicnic project drew inspiration from the Eating Motivation Survey (henceforth TEMS), published by Renner et al. in 2012 [12]. The survey was carried out to test whether or not the cultural heritage dimension of food would appear in a larger, multicultural sample and thus would underpin the importance of food choice in relation to socio-cultural and natural concern motives.

The TEMS is a confirmatory factor analysis with fifteen factors for food choice and ‘yielded a satisfactory model fit for a full 78 items representing 15 factors’ [12] (p. 117). For the BigPicnic Survey, six factors were chosen based on evidence that the qualitative data had uncovered. These factors were: Sociability, Social Image, Social Norms, Traditional Eating, Weight Control and Natural Concern. Additional items addressing Migration were added, as this issue appeared frequently in the qualitative data (see Appendix A). Sociability encompasses social reasons for food choice; Social Norms comprises food choice to meet others’ expectations; the factor Social Image is characterized by the consumption of food to present oneself positively in social contexts; the motivation to choose food items low in fat or calories to control one’s body weight is captured by the factor Weight Control. Traditional Eating corresponds to choosing foods out of traditional and circumstances-related reasons; Ethical aspects of food choice were captured by the factor Natural Concerns that assesses the preference for natural foods from fair trade or organic farming [12].

As mentioned above, the qualitative studies made a strong case for the cultural and social values attributed to food and the notion of food as cultural heritage. Specifically, the most prominent categories that emerged from the qualitative study with regard to the role of food as cultural heritage were ‘traditional eating’, ‘migration’ and ‘cultural diversity in food use’ and these were followed by ‘food stories/memories’ and the ‘social context of eating’. These findings suggested that there is also another factor influencing food choice which had not been addressed in the TEMS-survey. This one was paraphrased as Migration and the survey participants were asked whether or not being born and having grown up in a particular country affected their food choice. The TEMS item blocks proved themselves quite reliable and valid having a Cronbach’s range from 0.60 to 0.73. It is noteworthy that the item block for Migration had a score of 0.75 on the same range (See Table 1). Items were formulated by the authors to get a first insight into how important a migration background might be when it comes to food choices.

Table 1.

Reliability of the factors for food choice.

Although all 15 TEMS factors would have been equally interesting to look at, we decided to go for those seven factors only as they were well justified by qualitative data collected for the BigPicnic project. TEMS items have been tested in Germany and were published in English. Thus, the selected questions were already available in these two languages. The BG Partner translated the BigPicnic questionnaire version into another five European languages. The translation is always a source of error that needs to be considered whenever data is presented as if the source is equal.

In terms of the overall sample, 1189 people filled in the questionnaire after visiting a BigPicnic exhibition, workshop or science café in a particular partner country. Topics addressed in these learning experiences were related to food in a broad sense. Two hundred and ninety of these questionnaires were filled in by visitors of BGCI’s (Botanical Gardens Conservation International) 10th International Congress on Education in Botanic Gardens (held in September 2018 in Warsaw) or via an online questionnaire format offered on the BigPicnic website [33]. These questionnaires form a distinct group called International (INT). All others are marked in relation to the country where they were collected.

4. Results

4.1. The BigPicnic Survey Results

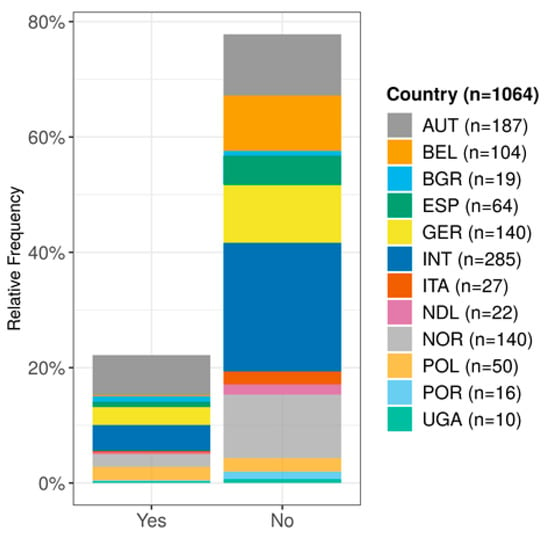

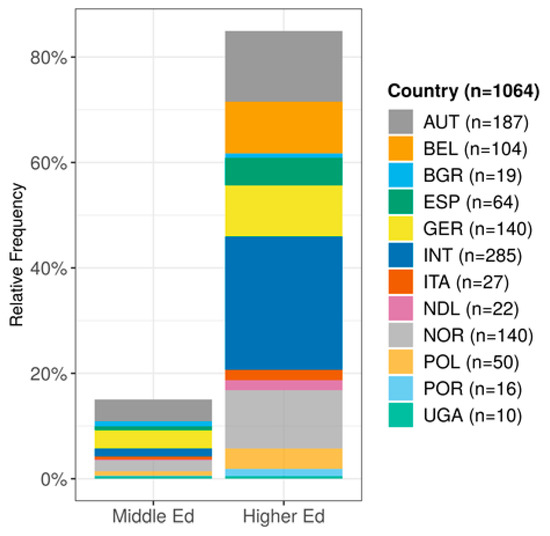

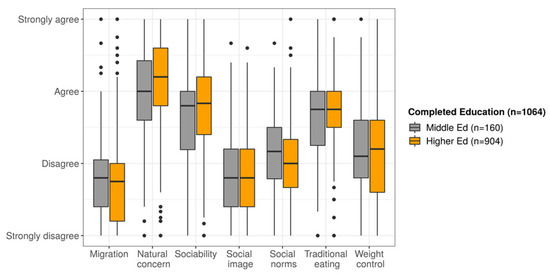

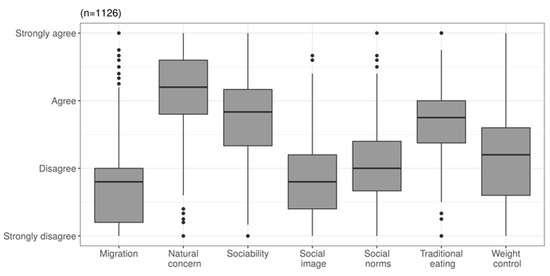

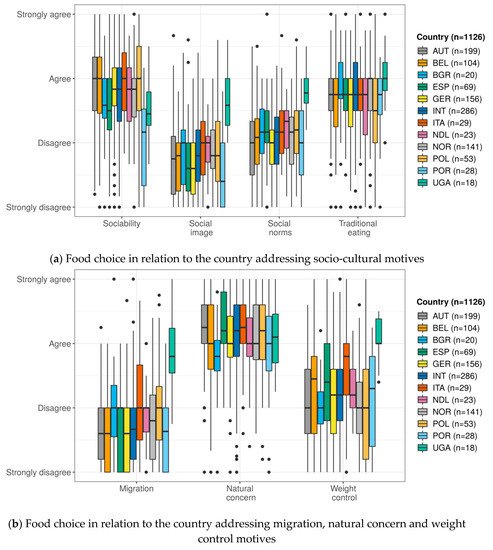

The TEMS study had a sample size of 1040 participants. The mean age was 29 years (SD = 11; range 18–77 years) [12]. This was quite similar to the sample covered by the BigPicnic survey. There were 1189 participants that filled in the BigPicnic questionnaire. Of those, 63 questionnaires were excluded from the analysis because participants either filled in less than 75% of the survey items or skipped an entire factor and/or answered only “don’t know”. About 40% of the remaining 1126 BigPicnic survey participants (67% women) were between 20–39 years old, another 40% were 40–60 years old. About a quarter of the survey participants indicated that they were still in education (Figure 1). The people who completed the survey in most partner countries predominantly had qualifications from higher education institutions (highest level of education = college or university, Figure 2). When looking at how people ticked boxes in relation to the seven food choice factors, neither education nor gender appears to make a difference (Figure 3). Not all participants ticked a box for the education question. Thus, the samples in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 addressing education is lower (n = 1064) than for Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 (n = 1126). However, these participants filled out more than 75% of the survey. That is why we decided to use their data for analysing factors of food choices (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The statistical distribution amongst middle and higher-educated participants was quite similar in most partner countries (Figure 2). In Belgium, people who took part had almost exclusively a higher education background. The international group (INT) is characterised by a higher percentage of women with a higher education background, while in general, more than twice as many women than men filled in the questionnaire (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Distribution of people still in education or not amongst survey participants in each country.

Figure 2.

Distribution of level of education amongst survey participants in each country.

Figure 3.

Food choice in relation to the level of education.

Figure 4.

Factors for food choice chosen by all survey participants.

Figure 5.

Food choice in relation to the country in which the survey was conducted.

Natural Concerns appears to be the most agreed factor out of those offered in this survey (Figure 4). Most people either agreed or strongly agreed with statements related to preferences for ‘natural foods’ from ‘fair trade’ or ‘organic farming’ or ‘environmentally friendly food’. Sociability, as well as Traditional Eating, were also prominent. People agreed that they ‘Eat what they eat’ because ‘it makes social gatherings comfortable’ and ‘enjoyable’, as well as ‘it belongs to certain situations’ and ‘family traditions’. On the other hand, Social Norms and Weight Control appear to be less important factors. Furthermore, Social Image and Migration factors were also not considered important. Most participants either disagreed or strongly disagreed with Social Image statements such as ‘a particular food is chosen because others like it’ or ‘it makes me look good in front of others’.

Most people disagreed or strongly disagreed with statements such as ‘I cannot buy ingredients I need in the country I currently live’ or ‘my food habits changed since moving to the country I currently live’. It is worth stressing here that people with migration backgrounds who participated in the BigPicnic co-creation teams emphasized food as part of their cultural identity. However, this aspect did not appear to be important for survey participants. One could assume that either this particular group of people was not well represented amongst visitors or it did not engage in this survey because of language or cultural barriers.

Figure 5 shows the results according to the country in which data was collected. INT is data collected via the international BigPicnic website as well as during an international conference. Thus for these questionnaires, the nationality of participants is unknown. Country results show that for each individual factor, the score is statistically significant dependent on the country (chi² independence test) in which the survey was conducted. This significance is also due to the INT- questionnaires, which suggests that the context in which the questionnaire is filled in has an impact on how people tick the boxes. It is evident from the data gathered that Uganda shows a different pattern. The BG partner in Uganda explained that there is a disparity in terms of food availability between people from different social classes in the country and this influences attitudes to issues such as food waste (see also Section 5.1, p. 12).

4.2. Results from the Qualitative Studies

The following is a summary of the meta-analysis conducted on the qualitative studies (carried out by the BG Partners) and their findings of food security that directly or indirectly informs and influences sustainable food choices and consumer preferences. Overall, the food choices that people make were strongly linked to the provision of quality education and were considered to have an important role in achieving good health and well-being.

BG Partners identified numerous areas where quality education can contribute to nutrition for sustainable and healthy diets. In fact, their audiences identified the provision of food education as a key priority. Looking more closely at how ‘food education’ was defined in this context, the following categories emerged: ‘ability to know how to access information about food’, ‘the acquisition of food skills (i.e., how to prepare, cook and handle food)’, ‘knowing how to prepare healthy food and what constitutes a balanced diet’, ‘the importance of food labels’, ‘knowing more about how to grow food plants and where food actually comes from’, and ‘science plays a significant role in providing food education’.

In addition, raising awareness about food-related issues was highly appreciated by the respondents. Developing certain food habits was deemed significant as a way for people to adopt healthier food habits in a more sustainable and true manner. The BG Partners also identified the provision of environmentally sensitive education (what they termed as ‘green education’) as something that is strongly valued and that people would expect to receive at both school and university level. Studies carried out particularly at Alcalá de Henares in Spain, emphasised the importance of adopting a certain value system that could potentially lead to more informed food choices.

What is important to note from the qualitative studies is that the vast majority of the qualitative study reports placed healthy food choices as the most important factor for achieving good health and well-being. Other factors included consuming ‘safe food’, pursuing a ‘healthy and balanced diet’, paying attention to ‘weight control’ and ‘feeling well in one’s self’. The ‘food choices’ mentioned previously were defined most strongly through whether a product is organic or natural with ‘financial reasons’ following closely. The selection criteria of the audiences were also influenced by whether a product is regional or local, whether a product looks good (including how it is packaged) and by general food habits such as taste, liking or not liking a type of food. Other parameters that were deemed to impact on food choices included ‘individual choices’, ‘ethics’ (e.g., animal welfare), ‘nutritional and health benefits’ (such as eating more vegetables, legumes or grains), the ‘quality’, ‘freshness’ and ‘seasonality’ of a product.

At this point, it important to mention that ‘how to make choices’ emerged as a factor also in the context of responsible consumption and production that links to the circularity and efficiency of food systems. Although this did not feature in a statistically important position as compared to other factors, it goes to show that audiences viewed food choices as having an impact on a wide range of issues.

Perhaps the most interesting outcome derived from the qualitative studies conducted during the BigPicnic project was the impact of cultural and social values attributed to food and the relevant notion of food as a form of cultural heritage. This is important for two reasons. First, because the project itself never intended to directly examine this aspect but, nevertheless, this emerged as a crucial parameter and could therefore not be ignored in the development of the quantitative survey. What is more, the food heritage dimension, as mentioned in the Introduction, has been to a great extent overlooked by the dominant European and global policies that deal with food and sustainable development. The emergence of a critical heritage discourse that places a new emphasis on the interrelationship between tangible and intangible elements [34], the growing awareness and promotion of intangible heritage by international organisations (such as UNESCO, ICOM) [35] and the increasing attention that food and culinary traditions receive through the lens of heritage [30] provide further support to the importance of the cultural heritage dimension of food.

The activities undertaken by the 15 BG Partners of the BigPicnic project engaged with a variety of themes surrounding food, and security and cultural and social values attributed to food were identified both directly and indirectly in nearly all of the botanical gardens (13 out of 15) and in 40 out of the 76 qualitative study reports conducted by the partners. These values were not articulated through references to food choices or consumer preferences per se. However, the aspects of food choices mentioned place a certain gravitas to the consideration of the food heritage dimension when analysing what people eat, when, why and with whom.

4.3. Comparing the Results

When looking at the results of both the quantitative survey and the qualitative studies from the point of view of food choices, it is evident that the BG audiences placed a bigger emphasis on ‘natural concerns’. Environmental and ethical sensitivities in relation to food products clearly seemed to be the top priority and this was reflected in the number of statements in support of food products that are ‘natural’, derived from ‘fair trade’ and ‘organic farming’ chosen from the survey options. Similarly, the qualitative studies pointed towards the same direction albeit with a greater emphasis on the role of education in supporting such food choices. In addition, the regionality and locality of the available food products seemed to be more important in the qualitative studies along with financial considerations (whether or not a product is too expensive). Both qualitative and quantitative research results, however, underline the contribution of food preferences and choices to healthy living and well-being.

Interestingly, ‘weight control’ as an individual factor appeared to be less important in the food choice survey. Audiences indicated that the motivation to choose food items that are low in fat or calories in order to control body weight was not very high. The frequency of occurrence of this factor was quite low in the qualitative studies as well. Although having a healthy and balanced diet in general featured far more strongly, the need to specifically control weight as a way to combat the negative impact of obesity and eating disorders was not as prominent. This was also the case with the category ‘feeling good with one’s self’.

’Traditional Eating’ featured strongly in the food choice survey as respondents indicated how important it is for people to choose foods that relate to specific traditions and to a variety of situations and circumstances (such as family traditions etc.). Indeed, the role of ‘traditional eating’ in defining how people can approach food safety appeared to be very important also in the qualitative studies. Various BG Partner qualitative studies reported examples of specific types of food that people are familiar with or culturally attached to because they grew up eating them. Several examples of specific types of plants or dishes that are often associated with special situations (events, celebrations, rituals) associated with familial, regional or national traditions were also presented. Although findings from all the BG Partners suggest that there is a special link between food, territory/locality and culture, the case of Uganda and Italy (with the Mediterranean diet), in particular, helped bring this issue in focus. Another aspect that is notable in the qualitative studies conducted for the BigPicnic project are the findings that imply that the diversity in relation to food cultures affects the way people use and consume food. In this context, the importance of cultural diversity in food systems (including the transport, production, processing, distribution and logistics of food) was also emphasised.

As mentioned above, for the purposes of this survey ‘sociability’ encompassed social reasons for food choice and many respondents agreed that they ‘eat what they eat’ because ‘it makes social gatherings comfortable’ and ‘enjoyable’. The qualitative studies clearly also demonstrated that food has a special value in the context of social interaction, with both sharing food and eating with others being highly valued attributes. The majority of the comments derived from the qualitative study reports compiled by the BG Partners stressed how pleasant and useful it is for communities to be connected through occasions that involve making or eating food together. Furthermore, food appeared to have strong associations with specific memories and stories that people keep and remember. Most of the feedback about this topic revolved around the decisive role of childhood memories in defining attitudes towards food as well as knowledge about food. For example, in Poland, food triggered nostalgic thinking about home (e.g., grandma’s baking), while findings from Hannover (Germany) and Greece acknowledged the senses (e.g., taste/flavour, smell) as an important trigger for food memories as people automatically remember eating things in a specific way at a certain point in time. These direct references to food memories can be considered closely with the social element and dimension of food and eating patterns.

On the other hand, ‘social norms’ appeared to be less important factors within the survey results. In fact, pursuing food choices in order to meet the expectations of others was present in the qualitative studies mainly on individual examples. In one such example, in the very specific context of eating insects addressed in Belgium by the Botanical Garden Meise, it was observed that some food habits are often defined by social norms (whether or not our family or peers eat something or not) as parents and grandparents had a strong influence (sometimes positive, other times negative) on whether the children would taste or not taste insects. Following a similar trend in the feedback received from the BigPicnic audiences through the survey, the ‘social image’ factor represented by the statement ‘particular food is chosen because others like it’ or ‘it makes me look good in front of others’ was not something the respondents agreed with. This aspect was not frequently mentioned in the qualitative study reports as well.

One major difference between the finding of food choice survey and the qualitative studies was the ‘migration’ factor. In the context of diaspora communities, the qualitative studies carried out in Belgium and Scotland indicated that access to ingredients from the home country was an important factor as it allowed people to follow eating patterns that sustained their cultural identity and maintained their ability to reconnect with their country of origin. It is no coincidence that these findings came out predominantly from projects undertaken by the Botanical Garden Meise in Belgium in collaboration with members of the African community living in the country. Within this context, people of African origin expressed their concerns about not being able to buy and use certain food crops that are either not available in the Belgian shops or are available but lack the necessary quality and are not affordable. It was also interesting to observe that, in Edinburgh, food was seen as a medium for communication that enables members of diaspora communities to create social contacts with Scottish-born people and improve their knowledge of the English language and local accent. While the necessity of people living in foreign countries to adapt their food habits as a consequence was mentioned, that the importance of preserving traditional food preparation practices was also emphasised.

In contrast, most survey participants when asked whether being born and having grown up in a particular country affected their food choice, responded negatively. Neither the opportunities to purchase ingredients from their home country nor their food habits appeared to be influenced by moving to another country. Considering how significant food is for the maintenance of cultural identities (as seen by the qualitative studies and reported by other researchers), it can perhaps be assumed that this particular group of people was not well represented in the survey sample and/or among the people attending the particular BigPicnic activities. It may also be possible that representatives from migrant communities (which are usually considered as hard to reach audiences) could not or did not wish to engage in this survey because of language or cultural barriers.

5. Discussion

5.1. Reflecting on Food Choice and Consumer Preferences Based on the Outcomes of the BigPicnic Project

Food choices and consumer preferences can be influenced by a wide range of factors, which put together can have a strong impact on issues related to food security and sustainable development. The audiences of the BG partners of the BigPicnic project appeared to place great significance on Natural Concerns and these concerns explain their preference towards natural, fair trade, or organic food. The vital role of education in raising awareness and helping citizens to make informed food choices also emerged as a significant component. Sociability and Traditional Eating—relating to social gatherings, interactions and traditions—were two more aspects that featured high.

The BigPicnic project findings discussed in this paper confirm that there is a growing awareness among consumers of the importance of healthy living and well-being and of how food preferences and choices impact on the latter. What was even more striking in the findings of both the survey and the qualitative studies was the emergence of the socio-cultural parameters of food and of the food heritage notion as key aspect that can also influence what people choose to eat, how and with whom. This was also an opportunity to realise that food security policies at both the European (e.g., Food 2030) and global level (e.g., SDGs) overlook the cultural dimension of food. As a result, acknowledging and emphasizing the importance of food heritage in the context of food security was considered as an original and key contribution of the BigPicnic project. This was indeed also manifested in the final policy recommendations that aim to influence decision-makers and to get this message across at a policy level [36].

As mentioned in Section 3, the data gathered for the BigPicnic project built on previous research such as the TEMS survey. In reference to their sample, Renner and colleagues [12] (p. 125) commented it: ‘Being rather homogeneous in terms of cultural background, political values, and religious beliefs, this sample might have restricted variance in political values, religious beliefs, and traditions’. Indeed, the BigPicnic survey suggest that this limitation has to be considered. For example, Grunert et al. [37] showed that consumers in Germany and Poland are concerned about the environmental impact of meat cultivation and are willing to pay for reduced carbon emissions. Another limitation of this survey study, which should be addressed in potential future research and is also highlighted in the TEMS survey [12] (p. 126), is that environments, where food is scarce can render very different responses in terms of eating motives as opposed to environments where food is more abundant. This became evident in the case of Uganda (see Section 4.1 and Figure 5a,b, p. 9).

Nevertheless, the BigPicnic sample is multinational and multi-cultural. Thus, this survey adds a new perspective to data collected by the TEMS group earlier. The focus of this survey reflected the overwhelming evidence generated through the qualitative studies, which identified the central role food plays in developing and sustaining personal and collective identities. Food as cultural heritage emerged as an overarching theme during the co-creation sessions, in particular. The scientific community needs to be careful about quantitative research approaches that do not include a multicultural and multi-perspective approach. Culturally sensitive data is needed to get a more differentiated picture. What is more, education programmes for sustainable development need to acknowledge that there is no one-size-fits-all educational approach fitting the needs of people everywhere in Europe.

We need to develop a nuanced understanding of micro-food systems in order to identify patterns that apply across different cultures and those that are context or culture specific. This suggests that the European agenda about food security needs to take cultural perspectives into consideration, if it is to be successful. In terms of future research, it is important to consider the cultural and heritage dimension of food in the analysis and interpretation of the data. Far too many studies still do not address social or cultural aspects of food systems.

While comparing interrelation clusters, Renner and colleagues stipulate that “for sustainable eating behavior changes, health concerns need to be positively related to social and biological incentives for eating” [12] (p. 125). Findings from the BigPicnic studies suggest that, in addition, consumers need to become consciously aware of how their own cultural and heritage background may affect their food choices. This seems to imply that educational campaigns and activities conducted either in formal or informal settings need to create learning environments that provide people with opportunities to reflect on the importance that cultural and heritage aspects of food have on them as individuals and members of a community.

Survey results collected in 11 countries (n= 1189) suggest that the country, as well as the context in which the survey is conducted, has an impact on how people prioritise the factors which affect their food choices: Migration, Natural Concern, Sociability, Social Image, Social Norms, Traditional Eating and Weight Control. Yet, most of these factors are omitted from food security policies at the European (e.g., Food 2030) and at the global level (e.g., SDGs) [38]. Consequently, raising the profile of food heritage was seen as one of BigPicnic’s key contributions, especially on a policy level.

5.2. Food Security and Food as Heritage

As pointed out in Section 2, the different disciplines that engage with food and eating behaviors as their direct or indirect object of study (and their relevant discourses) often touch upon overlapping themes and issues (e.g., what defines food choices), but do not always engage in a multidisciplinary dialogue to explore where their disciplines could meet and cross-fertilise each other. Not surprisingly, decision-making processes and food choices are therefore usually not explicitly linked to cultural or heritage-based argumentation. In order to understand how people arrive at a given behavior and how they make food choices, it is important to take into consideration various factors and cultural and heritage dimensions are among them.

Analyzing why food security policies have not thoroughly addressed food heritage as a parameter is beyond the scope of this paper. However, simplistic assumptions about the relationship between academic social science research and policy can go some way towards explaining this lack of engagement with food heritage at a policy level. More often than not, research findings do not have a simple, direct impact on policy. Furthermore, when discussing the impact of research on policy-making, there is not always an agreement in terms of what the relationship between researchers and policy-makers (and those in positions of power more broadly) should be. When discussing research on food, it has also been emphasised that there is often no consensus about whether and how scholars can and should work with commercial partners that focus on commercial needs and interests [22] (p. 438). One can acknowledge that social research can be focused on providing research-based knowledge which then policy-makers may or may not use to make informed decisions [39,40,41]. However, it can be equally argued that applied research and policy research can and should be directly applicable to the formation and evaluation of social policy and related practice [42]. Influencing policy-makers and activists on issues of food security may entail some ethical dilemmas for researchers, but it is nonetheless viewed as valuable [5] (p. 168). No matter what our stance may be on this matter, great effort is needed in order for any research to have an actual impact and to convince policy-makers.

Our experience from working on the BigPicnic project demonstrated that dissemination is key. For this particular project, an orchestrated effort was made to disseminate our research outcomes to different audiences through a range of activities undertaken by all project partners. These efforts also culminated in a final festival that took place in Madrid on 27 February 2019, which was attended by almost 200 people including policy-makers, educators and other stakeholders. This event featured presentations, workshops, stands and other activities that not only promoted the outcomes of the BigPicnic project but also encouraged dialogue around food security. What is more, among the project deliverables was also the formulation of a set of six policy recommendations that were launched during the aforementioned festival and which were also widely circulated in both electronic and printed format [33]. As the project was funded by the European Commission, there was an obligation to thoroughly report on the outcomes and impact of the research as well as to try to influence its policy on food security, namely the Food 2030 framework.

The definition of food security on an international and intergovernmental level and what it should entail has been influenced, among other things, by the discourse on sustainability and by policy documents such as the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals [38], and the Food 2030 framework of the European Commission [43]. However, the ever-growing discourse on sustainable development has only relatively recently acknowledged the relevance and importance of cultural heritage. This is evident, for example, from the fact that the role of culture and cultural heritage is only mentioned in one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and only in one out of the 169 relevant targets (target 11.4). The tide has turned with international organisations such as UNESCO and ICOMOS recognising cultural sustainability as one of the four pillars of sustainable development and emphasising the importance of both tangible and intangible heritage [44,45,46]. Nevertheless, the 17 SDGs encompass a range of themes that are directly or indirectly relevant to food security, despite the fact that it have not yet been clearly articulated. On the other hand, the Food 2030 framework makes no direct reference to the cultural associations of food, therefore, indicating that the existing body of literature (e.g., anthropological) has not informed the relevant food and nutrition security priorities.

BigPicnic was not designed as a project that would address the concept of food as heritage specifically. What the authors of this paper have clearly witnessed is that people engaging with food security do not always have a background in anthropology and/or social studies (usually quite the opposite). Most of the people who work in the Botanic Gardens we engaged have backgrounds in science, botany and horticulture disciplines. None of the food security-related themes and activities that the each Garden chose to work on focused on issues related to food as heritage. At the same time, policy-makers themselves and people working in the food and agricultural sector or even the education sector cannot always be expected to have a strong awareness of the cultural associations of food or at least the research that academics have been conducting on this topic. For the BigPicnic project that is discussed in this paper, the botanical garden partners were instructed and encouraged to analyse their qualitative data with reference to certain themes that are underlined by the SDGs and the Food 2030 because of the importance of the latter for food security. During this process, the importance of food as heritage emerged despite the aforementioned disconnect between cultural associations of food and the dominant food security policies.

As mentioned in Section 2, the recognition of food as a form of cultural heritage with the relevant literature that articulates food in this way is a phenomenon of the 21st century [21]. Research on food as heritage is inevitably influenced also by disciplinary boundaries and the tendency to divide research in line with clear-cut disciplinary boundaries. It is widely acknowledged that each discipline holds a certain amount of tacit knowledge [47] and has an established canon and this canon is maintained, among other things, through a process of gatekeeping [48,49]. Food heritage clearly sits at an interface of several existing disciplines and fields of research. One could argue that any attempt to synthesize the insights provided by established disciplines dealing with food culture, without being restricted by a reluctance to blur disciplinary boundaries, can render research on food heritage richer and more innovative. Studies of food as heritage can be likened to the circumstances that have promoted the development of cultural heritage studies as a multidisciplinary field which is currently emerging as truly inter- and trans-disciplinary, with researchers and practitioners from different areas of expertise striving to work together and cross-fertilise their research principles, methodological approaches and methods [35]. Indeed, food anthropologists, for example, have seen themselves as reaching a shift towards transdisciplinarity [50] (p. 4).

It would be fair to say that the observations made through the BigPicnic project about the importance of food as a form of cultural heritage support a potential amendment of the food security definition. Indeed, the BigPicnic consortium has recently added ‘heritage’ to ‘access’, ‘sovereignty’ and ‘safety’ (Figure 6). The inclusion of heritage in the definition is a sign of recognition for the importance of culinary traditions and the special associations and meanings that cultural identities (local/regional/ethnic/national) imbue to any conceptualisation of food, food security and food choices for that matter.

Figure 6.

Food security definition: the recently amended version adopted by the BigPicnic consortium that has added ‘Heritage’ to ‘Access’, ‘Sovereignty’ and ‘Safety’ [51].

6. Conclusions

This paper identified Natural Concerns, Sociability and Traditional Eating as important factors for shaping food choices and consumer preferences through a survey conducted in 12 countries for the BigPicnic project. The relevance and importance of the notion of food heritage and careful consideration of the socio-cultural aspects of food were also discussed in the context of existing food security policies, which have been deemed not to address the aforementioned issues efficiently. This paper has reflected on some of the reasons that have potentially influenced food security policy-makers and other stakeholders to overlook the cultural associations of food. Moreover, the authors have argued for the importance of policy-making that is informed by research on food, food security and food choices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; Methodology, S.K., G.A. and T.M.; Validation, S.K. and T.M.; Formal analysis, K.J.S. and F.S.; Investigation, S.K., G.A., T.M., K.J.S. and F.S.; Resources, S.K. and T.M.; Data curation, S.K. and K.J.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.K., G.A., T.M. and K.J.S.; Writing—review and editing, S.K., G.A., T.M. and K.J.S.; Visualization, K.J.S. and F.S.; Supervision, S.K. and T.M.; Project administration, S.K. and T.M.; Funding acquisition, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 710780.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Julia Thaler and Elisabeth Carli for the preparation of the raw data, and Elisabeth Carli for her support in the statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The 19 Partners of the BigPicnic project.

Table A1.

The 19 Partners of the BigPicnic project.

| Name | Country |

|---|---|

| University of Innsbruck | Austria |

| Botanical Garden of the University Vienna | Austria |

| University Botanic Gardens of Sofia University “Saint Kliment Ohridski” | Bulgaria |

| Hortus botanicus Leiden | The Netherlands |

| Waag Society | The Netherlands |

| University of Warsaw Botanic Garden | Poland |

| Juan Carlos I Royal Botanic Gardens, Alcalá de Henares University | Spain |

| Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum at Freie Universität Berlin | Germany |

| School Biology Centre Hannover | Germany |

| WilaBonn (Science Shop Bonn) | Germany |

| Natural History Museum of the University of Oslo | Norway |

| National Museum of Natural History and Science at the University of Lisbon | Portugal |

| Royal Botanic Garden of Madrid | Spain |

| Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh | United Kingdom |

| Balkan Botanic Garden of Kroussia | Greece |

| Botanic Garden Meise | Belgium |

| School Biology Centre Hannover | Germany |

| Bergamo Botanic Garden “Lorenzo Rota” | Italy |

| Tooro Botanical Gardens | Uganda |

The questionnaires used in this study, for example, in English and German, as published by Renner et al. [12].

| I eat what I eat, … | strongly disagree | disagree | agree | strongly agree | don’t know | ||||

| . . . because it makes a social gathering more enjoyable | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because my family/partner thinks that it is good for me | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it contains no harmful substances (e.g., pesticides, pollutants, antibiotics) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it would be impolite not to eat it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is considered to be special | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because others like it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is pleasant to eat with others | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because my own food habits chanced since moving to the country I currently live | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it makes me look good in front of others | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is fair trade (a fair price has been paid to producers) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . to stand out from the crowd | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it makes social gatherings more comfortable | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is natural (e.g., no additives like sweeteners or preservatives) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . to avoid disappointing someone who is trying to make me happy | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is organic (hasn’t been farmed using synthetic pesticides or fertilizers) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it facilitates contact with others (e.g., at business meals, events) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is trendy | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because I am overweight | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because I grew up with it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is seasonal | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because the life style in the country I currently live is different to the one I come from | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is environmentally friendly (e.g., production, packaging, transport) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is social | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because I watch my weight | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . so that I can spend time with other people | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because I do not know how to prepare the food I used to eat when I was a child | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because I want to lose weight | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because I am supposed to eat it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is low in fat | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because my doctor says I should eat it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it suits any other special day (e.g., graduation, passed exams, first or last day of school) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is low in calories | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because it is traditional (e.g., cultural, family or religious traditions) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because other people (my colleagues, friends, family) eat it | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because I do not have time to prepare the food I used to eat when I was a child | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . because I cannot buy the ingredients I need in the country I currently live | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Gender | male | female | other | ||||||

| □ | □ | □ | |||||||

| Which age group do you belong to? | 5–11 | 12–15 | 16–19 | 20–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |

| Are you still in full time education? | yes | no | |||||||

| □ | □ | ||||||||

| What is the highest level of full-time education you have received? | primary school | secondary school | vocational school | college | university | ||||

| □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||||

| What town do you live in? | |||||||||

| Who did you come with? | alone | partner | friends | family | family with children | colleagues | as part of an organized group | ||

| □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||

| Why did you come to this event? | |||||||||

| What do you think is the most important question food research should deal with in the future? | |||||||||

| What current developments in our food supply do you feel confident about? | |||||||||

| What current development in our food supply are you worried about? | |||||||||

| Ich esse was ich esse, … | stimme ich gar nicht zu | stimme nicht zu | stimme zu | stimme absolut zu | weiß ich nicht | ||||

| . . . weil es ein Zusammensein gemütlicher macht | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil meine Familie/mein Partner findet, dass es gut für mich ist | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es unbelastet ist (z.B. keine Pestizide, Schadstoffe, Antibiotika) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es unhöflich wäre, nicht zu essen | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es als etwas Besonderes gilt | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil andere es gut finden | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es schön ist, mit anderen Menschen zu essen | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil sich meine Essgewohnheiten geändert haben, seit ich in das Land gezogen bin, in dem ich jetzt lebe | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich damit vor anderen gut dastehe | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es aus fairem Handel kommt | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich mich dadurch von anderen abhebe | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es ein Treffen angenehmer macht | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es naturbelassen ist (z.B. nicht gentechnisch verändert) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . um jemanden, der mir eine Freude machen will, nicht zu enttäuschen | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es aus biologischer Landwirtschaft kommt | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es den Kontakt mit anderen Menschen erleichtert (z.B. bei Geschäftsessen, Feiern) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es ’in’ ist | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich übergewichtig bin | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich damit aufgewachsen bin | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es gut zur Jahreszeit passt | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil der Lebensstil in diesem Land anders ist als in dem Land, wo ich herkomme | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es die Umwelt wenig belastet (z.B. durch Produktion, Verpackung, Transport) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es gesellig ist | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich auf mein Gewicht achte | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich dabei Zeit mit anderen Menschen verbringen kann | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich nicht weiß, wie man das Essen zubereitet, das ich als Kind gegessen habe | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich abnehmen möchte | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es von mir erwartet wird | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es wenig Fett enthält | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil mein Arzt sagt, dass ich es essen sollte | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es zu bestimmten Situationen dazugehört (z.B. Abschlussfeiern, erster oder letzter Schultag) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es wenig Kalorien hat | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . aufgrund von Traditionen (z.B. Familientradition, kulturelle oder religiöse Feste) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil andere (Kollegen, Freunde, Familie) das essen | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil ich keine Zeit habe das Essen zuzubereiten, das ich als Kind gegessen habe | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| . . . weil es die Zutaten, die ich brauche, in diesem Land, in dem ich jetzt lebe, nicht zu kaufen gibt | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | ||||

| Geschlecht | Männlich | Weiblich | Anders | ||||||

| □ | □ | □ | |||||||

| Welcher Altersgruppe gehören Sie an? | 5–11 | 12–15 | 16–19 | 20–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80+ |

| □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |

| Befinden Sie sich noch (überwiegend) in Ausbildung? | Ja | Nein | |||||||

| □ | □ | ||||||||

| Ihre höchste abgeschlossene Ausbildung ist | Volksschule | Hauptschule | Lehre | Matura/Meisterprüfung | Universität/Fachhochschule | ||||

| □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | |||||

| In welcher Stadt/welchem Ort leben Sie? | |||||||||

| Mit wem sind Sie heute hier? | Alleine | Partner | Freunde | Familie | Familie mit Kindern | Kollegen | Als Teil einer organisierten Gruppe | ||

| Warum sind Sie heute zu dieser Veranstaltung gekommen? | |||||||||

| Was denken Sie, ist die wichtigste Frage, mit der sich die Forschung im Bereich der Nahrungsmittel in Zukunft auseinandersetzen sollte? | |||||||||

| Welche gegenwärtigen Entwicklungen bezüglich unserer Nahrungsversorgung stimmen Sie zuversichtlich? | |||||||||

| Welche gegenwärtigen Entwicklungen bezüglich unserer Nahrungsversorgung beunruhigen Sie? | |||||||||

References

- Wippoo, M.; van Dijk, D. Blueprint of Toolkit for Co-Creation. BigPicnic Deliverable D2.1 London: BGCI. 2016. Available online: https://www.bigpicnic.net/media/documents/BigPicnic_-_D2.1_Blueprint_of_toolkit_for_co-creation.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Kapelari, S.; Alexopoulos, G.; Sagmeister, K. Partner evaluation reports on science café implementation. BigPicnic Deliverable D.4.1. London: BGCI. 2019; Available online: https://www.bigpicnic.net/resources/public-views-and-recommendations-rri-food-security/ (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Exhibition case studies. BigPicnic Deliverable D3.1 London: BGCI. 2019. Available online: https://www.bigpicnic.net/resources/exhibition-case-studies/ (accessed on 5 August 2019).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. Declaration of the World Summit on Food Security. 2009. Available online: http://www.fao.org/tempref/docrep/fao/Meeting/018/k6050 e.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2018).

- Pottier, J.; Klein, J.A.; Watson, J.L. Observer, Critic, Activist: Anthropological Encounters with Food Insecurity. In The Handbook of Food and Anthropology; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, M. Food Security—A Commentary: What Is It and Why Is It So Complicated? Foods 2012, 1, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.; Devereux, S. The Evolution of Thinking about Food Security. In Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa; ITDG Publishing: London, UK, 2001; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S. Food security: A post-modern perspective. Food Policy 1996, 21, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, M. “Food Security” and “Food Sovereignty”: What Frameworks Are Best Suited for Social Equity in Food Systems? J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2012, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Climate change and dietary choices — how can emissions of greenhouse gases from food consumption be reduced? Food Policy 1998, 23, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S. Climate Change and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, B.; Sproesser, G.; Strohbach, S.; Schupp, H.T. Why we eat what we eat. The Eating Motivation Survey (TEMS). Appetite 2012, 59, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringer, R. Food Security Global Overview. In Food Poverty and Insecurity: International Food Inequalities; Caraher, M., Coveney, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, J. A food systems approach to researching food security and its interactions with global environmental change. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.; Smith, M. Household food security: A conceptual review. In Household Food Security: Concepts, Indicators, Measurements: A Technical Review; Maxwell, S., Frankenberger, T., Eds.; UNICEF and IFAD: New York, NY, USA; Rome, Italy, 1992; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Pottier, J. Anthropology of Food: The Social Dynamics of Food Security; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goody, J. Cuisine and Class: A Study in Comparative Sociology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, S.W. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.; Valentine, G. (Eds.) Consuming Geographies: We Are Where We Eat; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Counihan, C.; Van Esterik, P. (Eds.) Food and Culture: A Reader, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J.A.; Watson, J.L. The Handbook of Food and Anthropology; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, M.L.; Klein, J.A.; Watson, J.L. Practising Food Anthropology: Moving Food Studies from the Classroom to the Boardroom. In The Handbook of Food and Anthropology; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016; pp. 435–457. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J. Creating ethical food consumers? Promoting organic foods in urban Southwest China1. Soc. Anthr. 2009, 17, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, J.; Klein, J.A. Introduction: Consumer and Consumed. Ethnos 2017, 82, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, R. Is a sustainable consumer culture possible? In Anthropology and Climate Change: From Encounters to Actions; Crate, S.A., Nuttall, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; Abingdon, UK, 2016; pp. 301–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, E.; Klein, J.A.; Watson, J.L. Supermarket Expansion, Informal Retail and Food Acquisition Strategies: An Example from Rural South Africa. In The Handbook of Food and Anthropology; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016; pp. 370–386. [Google Scholar]

- Welz, G. Contested origins: Food Heritage and the European Union’s Quality Label Program. Food Cult. Soc. 2013, 16, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxson, H.; Klein, J.A.; Watson, J.L. Rethinking Food and its Eaters: Opening the Black Boxes of Safety and Nutrition. In The Handbook of Food and Anthropology; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016; pp. 268–288. [Google Scholar]

- Luetchford, P.; Klein, J.A.; Watson, J.L. Ethical Consumption: The Moralities and Politics of Food. In The Handbook of Food and Anthropology; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016; pp. 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovine, M.A.; Brulotte, R.L. Introduction: Food and Foodways as Cultural Heritage. In Edible Identities: Exploring Food and Foodways as Cultural Heritage; Brulotte, R.L., Di Giovine, M.A., Eds.; Ashgate: Surrey, UK, 2014; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. Foreword. In Culinary Tourism: Material Worlds; Long, L., Ed.; University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 2004; pp. xi–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 10 September 2019).

- BigPicnic. Available online: https://www.bigpicnic.net/ (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Winter, T. Clarifying the critical in critical heritage studies. Int. J. Heritage Stud. 2013, 19, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagawa, N.; Smith, L. (Eds.) Safeguarding Intangible Heritage: Practices and Politics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- BigPicnic Recommendations. Available online: https://www.bigpicnic.net/resources/bigpicnic-recommendations/ (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/?menu=1300 (accessed on 14 July 2019).

- Davies, C.A. Reflexive Ethnography: A Guide to Researching Selves and Others; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.H. Research for Policy’s Sake: The Enlightenment Function of Social Research. Policy Anal. 1977, 3, 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- Shaxson, L. Is your evidence robust enough? Questions for policy makers and practitioners. Évid. Policy J. Res. Debate Pr. 2005, 1, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, C.; Fardon, R.; Harris, O.; Marchand, T.; Nuttall, M.; Strang, V.; Wilson, R. Anthropology and Public Policy. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Anthropology; SAGE Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Food 2030. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/76 d1 b04 c-aefa-11 e7-837 e-01 aa75 ed71 a1 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation). Introducing Cultural Heritage into the Sustainable Development Agenda. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/images/HeritageENG.pdf. (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Hosagrahar, J.; Soule, J.; Fusco Girard, L.; Potts, A. Cultural Heritage, the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the New Urban Agenda. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS Concept Note for the United Nations Agenda 2030 and the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (HABITAT II), Quito, Ecuador, 17–20 October 2016; Available online: http://www.usicomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Final-Concept-Note.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Throsby, D. Culture in sustainable development. In Reshaping Cultural Policies: A Decade Promoting the Diversity of Cultural Expressions for Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Gerholm, T. On Tacit Knowledge in Academia. Eur. J. Educ. 1990, 25, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtorf, C. A Comment on Hybrid Fields and Academic Gate-Keeping. Public Archaeol. 2009, 8, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowbel, L.R. Gatekeeping: Why Shouldn’t we be Ambivalent? J. Soc. Work. Educ. 2012, 48, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.L. Introduction: Anthropology Food and Modern Life. In The Handbook of Food and Anthropology; Klein, J.A., Watson, J.L., Eds.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Available online: https://www.bgci.org/our-work/projects-and-case-studies/bigpicnic/ (accessed on 5 November 2019).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).