Abstract

This study deals with a competitive knowledge network (CKN) where participants desire to pass their personally important exams, and henceforth want to contribute and seek knowledge about exam-related issues they need to solve. Besides, CKN members are basically competing with each other since they all aim to pass the same exams. Therefore, from the contributor’s perspective, if the advisor fears that his/her advice can be detrimental to his or her own benefits, knowledge sharing (KS) intention within the CKN may be hindered by their expectation of competitive advantage. However, few studies were done about the effects of such fear and a sense of competition on KS continuance intention in the context of CKN. In this sense, our study aims to elucidate the effects of competition and fear on KS continuance intention in a mobile CKN. By using 296 valid questionnaires, we obtained very meaningful conclusions such that competition is a driving force rather than an obstacle to KS among CKN members, and fear also enhances members’ sustainable KS intention.

1. Introduction

Recently, peer-to-peer problem solving virtual networks called knowledge networks have become widespread in many countries. People routinely visit knowledge networks when they need others’ help and solutions for their own problems [1]. This phenomenon is expected to become more prevailing as mobile devices based on smartphones take a considerable portion of Internet time in our daily lives, which was rapidly increasing from 26% in 2014 to 48% in 2019 [2]. In South Korea, the average time spent per day with smartphones by adults is dominatingly increasing in South Korea during the recent five years from 2015–2019 [3]. The greatest challenge of knowledge networks is to encourage members’ willingness to engage in acts of knowledge sharing (KS) [4,5]. Typically, two kinds of KS activities exist—contributing knowledge and seeking knowledge. Previous studies on knowledge networks have identified three main motivations for volunteer members [4], which include anticipated benefits and rewards, the moral obligation resulting from generalized reciprocity and altruistic behavior, and other factors (trust, identification, and social control) [5,6].

Among knowledge networks, a competitive knowledge network or CKN has unique characteristics such that network members desire to pass the same exams, but they need each other for the sake of seeking helpful guidance and tips on various types of issues necessary for preparing for those exams. In this sense, many members of CKN are usually committed to acts of contributing and seeking knowledge in the CKN. However, a sense of competition always lingers among members, which surely leads to fear of losing their own competitiveness when releasing their own tips to others. Therefore, CKN represents a complicated sense of emotional factors among members.

Potential knowledge sharing members seek contingent rewards by actively doing activities in the networks [7]. If the knowledge is related to knowledge holders’ benefits, knowledge sharing is likely to be hindered by their expectation of competitive advantage [8]. Additionally, in organizations, employees expect that they will receive extrinsic incentives (e.g., salary raises, bonuses, promotions, or job security) in return for knowledge sharing, and in fact, organizations have offered reward systems to encourage employees’ knowledge sharing. In this regard, members’ willingness to share knowledge in virtual advice networks will be affected by interpersonal competition.

Competition is always prevailing in CKN. Those CKN members who strongly perceive competition are inclined to achieve a better outcome than others [9]. There are two perspectives on competition. One view is that competition encourages individuals to do their best, and therefore, helps achieve collective outcomes (e.g., [10]). Another view holds that competition discourages people from helping each other, and damages collective performance (e.g., [11]). This leads to the following predictions in knowledge sharing. An organizational climate that emphasizes individual competition may hinder people from sharing knowledge, while cooperative climate may promote knowledge sharing between individuals by creating trust, a necessary condition for knowledge sharing. Then, from the viewpoint of rewards (e.g., individual incentives) expected after knowledge sharing, if individuals who participate in knowledge sharing have feelings of competition, such feelings may have a significant negative effect on their knowledge sharing.

A sense of competition may be deeply related to negative feelings such as fear. People commonly fear knowledge sharing when competition exists among them. Fierce competition usually produces either winners or losers. The fear that one could be a loser in the competitive situations facing the CKN members particularly inhibits knowledge sharing [12]. For instance, if an individual is afraid that he/she may be exploited for sharing knowledge without rewarding [13], the knowledge owner will be reluctant to share his/her precious knowledge with implicit rivals in the networks.

Thus, emotions play as important predictors of members’ KS intentions in the CKNs. Especially, to the best of our knowledge, the influence of fear and sense of competition on KS among CKN members has remained unexplored fully in previous studies. Additionally, the relationship between individuals’ feelings toward CKN and their KS behaviors are not investigated sufficiently either [1]. Therefore, filling the research void is necessary.

Further, members in knowledge networks have particular needs and motivations that are connected to different KS behaviors about knowledge contribution and knowledge seeking [14,15]. However, previous KS studies have investigated two KS behaviors separately, though we need to get a comprehensive understanding of those two KS behaviors in a single integrated context. Especially as it is quite interesting from the view of research to know why mobile users desire to conduct KS activities (i.e., knowledge contributing and knowledge seeking) voluntarily in the CKN where competition prevails among members.

The purpose of this study is, therefore, to verify the following two RQs (research questions). RQ1: How much do emotional factors exercise their influence on the CKN members’ KS intention about knowledge contributing and knowledge seeking? RQ2: Do members’ KS intentions, attitudes, and the antecedents differ depending on the level of fear perceived by CKN members?

2. Theoretical Background and Research Model

2.1. Definition of Knowledge

Philosophers have long had many epistemological debates about what knowledge is since the classical Greek period [16]. Polanyi [17] classified knowledge as tacit or explicit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is personal and context-specific to communicate, whereas explicit knowledge is transferred and communicated in a formal language. Nonaka [18] argued that information is a flow of messages and the basis of knowledge, whereas knowledge can be justified by one’s beliefs. Data was perceived as a subconcept of information, and information as a subconcept of knowledge [16,19].

Many types of attributes of knowledge have been described from various perspectives to define what knowledge is. In organizational studies, researchers categorized the attributes of knowledge into three types: (1) object (structured), (2) cognition (unstructured), and (3) capability [20]. The perspective of objects indicates that knowledge can be relocated with a small cost. The perspective of cognition indicates that knowledge can be shared through communication between individuals. Additionally, the perspective of capability indicates that knowledge can be created through a dynamic interaction such as learning-by-doing.

In the fields of information system (IS) studies, however, researchers do not have a clear consensus on the classification of attributes of knowledge as well as its definition. For example, Alavi and Leidner viewed knowledge from five perspectives: (1) state of mind, (2) object, (3) process, (4) condition of having access to information, and (5) capability [16]. Accordingly, the perspective of the state of mind focuses on the expansion of individuals’ knowledge and its application to the organization. The process perspective is concerned with the application of knowledge acquired through training. The perspective of the condition of having access to information pertains to organizing knowledge for easy retrieval as an extension of knowledge as an object. Notably, IS studies seem to hold the view that it is unnecessary to participate in the debates on the conceptualization of knowledge if an understanding of knowledge is not a decisive factor in building KN [16]. For example, refer to Appendix A to see that many of the KN studies deal with knowledge as an extension of the right type of information, and a meaningful “thing” worthy of being shared among members. Additionally, it seems essential to note that since knowledge is ’sticky’ in a given context due to its attributes, different knowledge holders can use different types of knowledge in different contexts [20,21,22,23].

Therefore, this study defines knowledge in the CKN context as all kinds of meaningful information possessed by individuals, including ideas, facts, expertise, and experience, which is in concurrence with the definition of Bartol and Srivastava [23].

2.2. Knowledge Sharing Terminology

In many of previous studies, most common definition of the term “knowledge sharing” (or KS) in the context of virtual community like CKN refers to the behavior of helping and collaborating with others by sharing knowledge with the goal of solving problems, developing new ideas, or implementing policies, or the behavior of diffusing one’s knowledge to others [24]. On the other hand, knowledge transfer has been used to describe the exchange of knowledge sources between different groups, such as divisions or organizations, rather than between individuals [25]. Meanwhile, knowledge exchange is a social interaction that is affected by the relationships among people in networks [26], which includes both contributing and seeking knowledge [22,27]. As such, KS is subtly different from knowledge transfer and knowledge exchange.

However, these terms are quite similar to each other such that knowledge source moves, and contributors and beneficiaries exist. In previous studies, researchers tried to supplement each term interchangeably rather than trying to clearly distinguish them. For example, Lee describes KS as the transfer of knowledge through individuals, groups, or organizations [28]. Hendriks described KS as a characteristic of knowledge exchange by referring to the relationship between a knowledge possessor and a knowledge receiver [29]. KS was also described as people’s repeated and mutual knowledge exchange behavior [30]. Such interchangeable supplementation of those terms is also evident in IS studies about KN. As revealed in Appendix A, many IS researchers also use the term KS interchangeably with knowledge transfer or knowledge exchange.

Therefore, in our study, we use KS as a generic term to represent CKN members’ intention to get involved in KS activities such as knowledge contribution and knowledge seeking, and intention to continue such KS activities.

2.3. Competitive Knowledge Network (CKN)

Knowledge network (KN) is a virtual community for knowledge sharing based on platforms created with ICT technology. Activities that usually made the KN refers to a case of online social networking where KS occurs through links on the network, which is based on the voluntary participation of members with common interests and goals [31]. Therefore, the type of KN is characterized by two types: interaction type and database type [32]. Interaction type KN is a network where members share their knowledge and experience by posting or answering questions. On the other hand, database type KN is a network where members’ suggestions and opinions are stored on the KN platform and used by others.

CKN belongs to an interaction type KN, where a sense of competition works powerfully within members like a team actively engaged in knowledge sharing in an organization (e.g., [33]). However, it has unique characteristics that differ from the ordinary type of KN in which members just share knowledge in mutually collaborative contexts with a common interest and purpose. In contrast, the CKN is characterized by a strong sense of competition among members. They are basically contenders who need to compete with each other to attain a hard-to-win goal such as either passing the exam or earning a big sum of money through stock investment. Therefore, in the usual context of the CKN, sharing experiences or information with other members about very sensitive issues related to the goal would be like releasing a secret to potential rivals and competitors. Nevertheless, active KS activities occur in many numbers of CKNs around the world, and the CKN-related research issues deserve receiving due attention from the perspective of KS studies.

2.4. Hypothesis Development

2.4.1. KS Intention and Satisfaction

In knowledge sharing research, individuals’ actual knowledge sharing behaviors can be examined by measuring their intentions. In theory, the prediction of individuals’ actual KS behaviors through their KS intentions is supported by two major theories: Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). TRA is a social psychology model that focuses on the elements that determine the reasons for behavioral intention [34]. According to TRA, an individual’s tendency to carry out a specific behavior determines the performance of that behavior, while an individual’s attitude and subjective norms determine behavioral intention. TRA theory has been verified as a successful model in explaining knowledge sharing behavioral intentions [24,35,36,37]. TBP is an expanded version of TRA. According to TPB, individual behavior can be explained by intention, which is influenced by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [38]. In KS research, TPB theory has also been used to explain individuals’ decisions to engage in knowledge sharing [37] and to analyze individuals’ intentions and actual behaviors [24,36]. That is, members with greater intentions to share knowledge are likely to engage in knowledge sharing. Thus, it is possible to predict individuals’ knowledge sharing behaviors by measuring their KS intentions in virtual advice networks.

Researchers have long considered knowledge sharing as a way to foster knowledge networks. Although motivating members to share their knowledge voluntarily is a challenge in sustaining knowledge networks, the greater challenge is to stimulate their willingness to continue knowledge sharing [39]. Therefore, in order to establish sustainable knowledge networks, it is necessary to retain members and motivate them to use virtual networks continuously. However, there exist many unexplored research issues about the relationship between members’ KS activities and their intention to continue sharing knowledge [40,41].

Theoretically, continuance intention to use information systems such as knowledge networks are largely supported by two theories: Expectation Confirmation Theory (ECT) and IS Continuance Theory. These theories are based on the relationship between satisfaction and continuance intention. ECT developed by Oliver [42] suggests that customers’ continuous purchase is driven by satisfaction. This indicates that customers’ positive disconfirmation will bring them satisfaction, which is associated with the intention to continue. Bhattacherjee [43] theorized the IS continuance model that adapted the ECT. Bhattacherjee suggests that users’ satisfaction is the factor that strongly predicts the intention toward IS continuance.

From these arguments, we suggest that a large gap between members’ expectations and actual KS experience will reduce their degree of satisfaction in knowledge networks, and will lead them to stop participating in knowledge sharing. Thus, we developed the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Members’ KS satisfaction positively affects their KS continuance intention.

However, in knowledge networks, knowledge is shared asymmetrically between a minority of contributors and a majority of recipients (e.g., [35,37]). Usually, a small number of individuals contribute knowledge, and many individuals use that knowledge. With the efforts of the minority, knowledge networks can be repositories of a great deal of knowledge for potential knowledge seekers [44], and many knowledge seekers may also drive the minority to contribute more by supplying positive feedback and increasing contributor recognition in knowledge networks [45]. As the two behaviors of contributing and seeking knowledge must occur together to ensure the predicted benefits of knowledge networks, it is essential to investigate the two KS behaviors simultaneously in the context of research. Nevertheless, most KS studies have addressed only one direction of knowledge flow, such as contribution [27]. Therefore, in both dimensions of contribution and seeking, we developed the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Members’ intention to contribute knowledge positively affects their KS satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Members’ intention to seek knowledge positively affects their KS satisfaction.

2.4.2. Emotional Factors on KS

Emotion has been always a key factor for motivating individuals to engage in KS. In this study, we consider a sense of competition, altruism, feelings of membership and influence, and fear to investigate their effects on KS intention.

A sense of competition is defined as a desire to perform better than one’s rivals do. Generically, the sense of competition that individuals perceive will have potentially more negative effects on KS because competition tends to usually make individuals withhold KS not to benefit others [7]. Bartol & Srivastava [23] suggest that an individual may, in fact, perceive KS behavior to be detrimental to self-performance. Yang and Maxwell [46] also argued that greater perception of internal competition might be more likely to cause people to protect rather than share information. By the way, in competitive environments like CKN, individuals may treat each other as rivals and use different strategies to reach their own goals at the expense of others. That is, that members who perceive greater levels of competition will be less likely to contribute their knowledge to others, whereas they will be more likely to seek knowledge in the CKN. Based on these arguments, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).

Members’ sense of competition negatively affects their intention to contribute knowledge.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).

Members’ sense of competition positively affects their intention to seek knowledge.

Altruism is exhibited in situations in which people experience internal enjoyment by helping others voluntarily [14,47,48]. Altruism is defined as a voluntary action to help others improve their welfare without the expectation of returns [39]. The knowledge that contributes to others’ welfare motivates altruistic people with intrinsic enjoyment and satisfaction [8]. Fang and Chiu [39] found that members’ altruism influenced intentions to continue KS positively. Ma and Chan [49] argued that altruism provides an essential condition for KS by reducing conflict and promoting participation. Members with higher levels of altruism will be more willing to contribute their knowledge to others and will be more likely to intend to seek others’ knowledge due to the pleasure of participating in the CKN. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed.

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

Members’ altruism positively affects their intention to contribute knowledge.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

Members’ altruism positively affects their intention to seek knowledge.

There is another kind of emotional factor related to the CKN. When a group of people get together and exchange feelings and information for a period of time, a sense of community emerges, which is defined as “a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together” [50,51]. The CKN is a virtual knowledge network where a number of members often spend time together in an online community by creating knowledge, sharing it, and supporting others, etc. The sense of community consists of four interactive constructs of feelings of membership, feelings of influence, integration and fulfillment of needs, and shared emotional connection [51]. Feelings of membership indicate that people experience the feeling of being part of a community. Feelings of influence imply that members believe they may affect or control other members of the community. Integration and fulfillment of needs suggest that members believe that, in the course of cooperating with other members, the community resources will meet their needs. Shared emotional connection reflects members’ belief that other members share a history, common places, times, and similar experiences.

Therefore, in the context of the CKN, the sense of community naturally transforms into the sense of virtual community, which is similarly defined as “the members’ feelings of membership, identity, belonging, and attachment to a group that interacts primarily through electronic communication” [50,52]. In this respect, it is no surprise that in order for the CKN to sustain members, to attract potential newcomers, and to facilitate knowledge sharing among members, it is necessary to foster members’ sense of virtual community [1]. Nahapiet and Ghoshal [53] suggested that members’ identification with knowledge networks will be encouraged by the sense of virtual community and will affect their willingness to share knowledge with other members in the same knowledge networks.

However, it should be noted that those measurements related to the sense of community cannot be directly applied to measuring the sense of virtual community, because the virtual knowledge networks like CKN differ from face-to-face communities, in that the synchrony, physical proximity, and spatial cohesiveness do not apply to the virtual knowledge networks [52]. Henceforth, Abfalter et al. [50] suggested that in considering these limitations, most researchers should measure the sense of virtual community by establishing their own qualitative models, measuring the concept in alternative ways, adding additional items to the original sense of community’s items, or testing the validity and reliability of the sense of community’s measurements indirectly. In the case of Koh and Kim’s study [54], three dimensions (membership, influence, and immersion) were proposed as the sense of virtual community measurements [1]. In this sense, in order to develop measurements of the sense of virtual community like CKN, we considered ‘feelings of membership’ and ‘feelings of influence’ as independent variables. We suggest that members with higher ‘feelings of membership’ are more likely to want to have a strong relationship with their participating CKN, which will encourage them to participate more actively in KS activities. Besides, members with higher ‘feelings of influence’ are more likely to try to have a greater influence on other members in the CKN by constantly sharing their precious personal experiences and reminding them of their presence. Therefore, we developed the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Members’ feelings of membership positively affect their intention to contribute knowledge.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Members’ feelings of membership positively affect their intention to seek knowledge.

Hypothesis 6a (H6a).

Members’ feelings of influence positively affect their intention to contribute knowledge.

Hypothesis 6b (H6b).

Members’ feelings of influence positively affect their intention to seek knowledge.

2.4.3. Fear and Its Moderating Effect

In the context of KS, fear refers to the severe anxiety of losing one’s unique value or being defeated by a rival. Once knowledge is shared among members in the CKN, the shared knowledge could become public goods in the CKN that anyone can use, which may make knowledge contributors think twice before sharing their knowledge [6]. This phenomenon can cause anxiety about losing one’s value from knowledge contributors, which refers to the fear of losing one’s unique value [13]. In this case, the person will be more cautious about KS in the knowledge networks [12,13]. In organizations, performance goals and incentive systems can encourage competition among employees. In this case, peers are likely to regard each other as implicit rivals. Then, employees may be concerned about being defeated by their rivals with the anxiety that their peers can achieve greater performance using the knowledge they share. As a result, the fear of being defeated by a rival will also inhibit KS activity [12].

There is no previous study in the field of CKN investigating how the level of individuals’ fear moderates the relationship between the antecedents of KS intentions and the related variables. Our assumption is that members’ KS attitudes will differ between members depending on the level of fear they feel in the CKN. Therefore, we developed the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Members’ KS intentions, attitudes, and the antecedents differ between a high-level fear group and low-level fear group.

2.5. Research Model

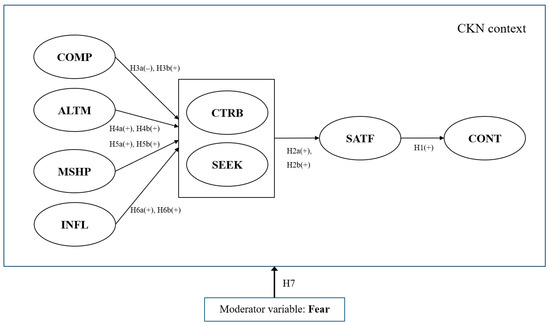

On the basis of the proposed hypotheses discussed so far, we propose a research model in which the main eight constructs are employed to represent all the hypotheses. The model assumed that the sense of competition, altruism, feelings of membership, and feelings of influence have effects on KS intention composed of both knowledge contributing intention and knowledge seeking intention. In addition, the KS intention is also assumed to have a positive effect on KS satisfaction which positively leads to KS continuance intention. To represent how the fear perceived by members has moderating effects, we added fear as a moderating variable. This study extends upon a number of previous studies about KS intentions in the context of the CKN. For example, significant relationships between individuals’ emotional attitudes (towards enjoying helping, reciprocity, self-efficacy, sense of community, playfulness, etc.) and their intentions of knowledge contributing and seeking have been empirically investigated [55,56,57]. Additionally, the impact of very limiting factors, such as commitment and emotional connection, that influence knowledge contributing intentions were also analyzed [58]. However, contrary to these previous studies, this study applies ECT theory and IS continuance theory in the context of mobile CKN to reveal whether mobile users’ KS intentions lead to their continuance intention to share knowledge through satisfaction with the use of mobile CKN contexts. Henceforth, this study aims to make a significant contribution to supplementing KS studies. Our research model is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model. Note: COMP, sense of competition; ALTM, altruism; MSHP, feelings of membership; INFL, feelings of influence; CTRB, knowledge contributing intention; SEEK, knowledge seeking intention; SATF, KS satisfaction; CONT, KS continuance intention. In the hypothesis number, ’a’ targets knowledge contributing intention (CTRB). ’b’ targets knowledge seeking intention (SEEK).

3. Research Methodology and Results

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

We collected data through an online self-report survey targeting the members of a mobile CKN in a specific domain, where members help each other to solve their own raised exam-related issues by participating in the knowledge contributing and seeking activities with other members. We posted a URL link to our questionnaire on the forums and blogs to ask about members’ knowledge sharing experience using the mobile apps. To increase the participation rate in the survey, we offered cash in return to some participants. The characteristics and background of the participants are as follows.

Recently, due to the unprecedented high rate of unemployment among the youth in South Korea, many young adults in their 20s and 30s apply for a limited number of employment examinations offered by enterprises and local autonomous entities. Henceforth, it is no surprise that its competition is very fierce, and a sense of strong competition becomes rampant among applicants. In such a competitive context existing in the CKN, any advice from those members with either rich experience in taking exams in the past or reliable knowledge about a number of tricky issues related to exams is definitely helpful for members, quenching their thirst for information about how to prepare for the exams and what to do with respect to specific nettlesome topics related with the exams.

In response to fierce competition among the youth to pass the job exams to get admitted into target companies (or organizations), examinees had started operating the CKN to form communities for the sake of seeking mutual benefits among them. It is customary in the CKN for those experienced members to voluntarily post valuable knowledge related to exams, and provide a high quality of answers for tricky issues. For novice members, they are eager to seek any support and guidance from reliable and experienced members in the CKN. Despite many types of altruistic behaviors occurring in the CKN, all the members participating in the CKN are aware of the hard reality that they aim to pass the same exams, and unavoidably they would compete with each other in the end. This seems quite mutually contradictory and there are very few studies about an interesting research topic like this.

The survey questionnaire was developed to measure a total of nine constructs such as three individual emotion-related constructs (i.e., sense of competition, altruism, fear), two virtual community-related feelings (i.e., feelings of membership, feelings of influence), two KS intentions (knowledge contribution, knowledge seeking), and two dependent constructs (i.e., KS satisfaction and KS continuance). All the items of the questionnaire were adapted from the existing literature that had already been validated by researchers. Seven-point Likert scales were used to measure each item, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). To guarantee content validity, the original version of the questionnaire was refined before conducting a formal survey by two pilot tests. Detailed items are addressed in Appendix B. After excluding those inconsistent and incomplete questionnaires, we garnered 296 valid responses from a total of 320 respondents. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics.

3.2. Measurement Model and Results

It is usual that the measurement model is assessed by the statistical criteria of internal consistency reliability (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability), convergent validity (i.e., factor loading, AVE), and discriminant validity. Widely accepted thresholds are as follows. Cronbach’s alpha scores of at least 0.7 are required for high internal consistency. The threshold value of composite reliability (CR index) for a given construct is 0.7 [59]. The factor’s outer loading of each item should be 0.7 or greater to ensure individual item reliability [60]. The threshold value of the average variance extracted (AVE) is 0.5 [61,62].

Discriminant validity for a pair of two constructs was assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio and confidence interval up. The measure avoids one criticism of the “Fornell and Larcker” criteria, that it does not reliably detect the lack of discriminant validity in common research situations. The liberal threshold values for the HTMT ratio and corresponding confidence interval up are 0.9 and 1, respectively [63]. Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5 posit that all the constructs and items possess internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Results for the Measurement Model.

Table 3.

Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Table 4.

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) for Discriminant Validity.

Table 5.

Confidence Intervals for the Entire Data.

Self-reported data may suffer from the possibility of common method bias (CMB), which needs to be eliminated. In our study, two approaches were used to check the existence of the CMB. First, we examined a correlation matrix of the constructs. When the correlations are higher than 0.90, CMB issues can be raised. We confirmed that the highest correlation is 0.732 in Table 4, which shows that CMB is unlikely to be a big concern harming the results. As a second approach, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test on the constructs used in our research model. This test presented eight factors, and the most variance explained by one factor was 36.150% (less than 50%). The results showed that there is no threat of CMB, or it is not serious in our study as shown in Table 6 [64].

Table 6.

Common Method Bias Assessment.

3.3. Structural Model and Hypotheses Test Results

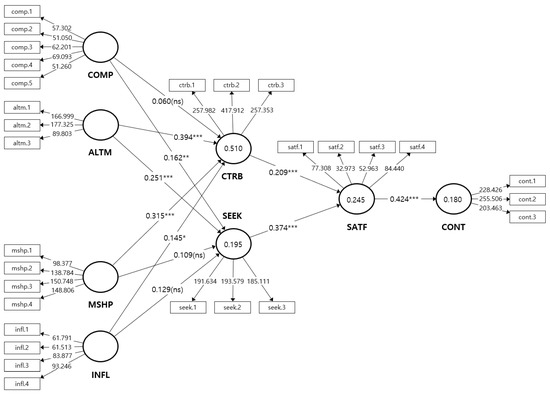

Based on the reliability and validity of the measurement model, the proposed hypotheses in Section 2 were tested using the 296 valid questionnaire sample data. The proposed hypotheses were statistically supported except for three hypotheses: H3a (Sense of competition→Knowledge contributing intention), H5b (Feelings of membership→Knowledge seeking intention), and H6b (Feelings of influence→Knowledge seeking intention).

Detailed results are as follows. Firstly, let us check the antecedents of knowledge contributing intention. Altruism (β = 0.394, p < 0.001), feelings of membership (β = 0.315, p < 0.001), and feelings of influence (β = 0.145, p < 0.05) had significantly positive effects on knowledge contributing intention. Secondly, let us think about the antecedents of knowledge seeking intention. Sense of competition (β = 0.162, p < 0.01) and altruism (β = 0.251, p < 0.001) had significantly positive effects on knowledge seeking intention. Thirdly, let us investigate KS attitudinal processes leading to KS continuance intention. Knowledge contributing intention (β = 0.209, p < 0.001) and knowledge seeking intention (β = 0.374, p < 0.001) had significantly positive effects on KS satisfaction, and KS satisfaction (β = 0.424, p < 0.001) had a significantly positive relationship with KS continuance intention.

Out of the results, new findings were such that a sense of competition is irrelevant to members’ knowledge contributing intention, and the two virtual community-related feelings (i.e., feelings of membership, feelings of influence) are only in a significant relationship with members’ knowledge seeking intention. Members’ altruism turned out to be a key variable affecting both knowledge contributing and seeking intentions in the CKN context. Figure 2 and Table 7 summarize hypotheses test results.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM Results (Note: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)

Table 7.

Results for Hypotheses Tests (N = 296).

3.4. Welch-Satterthwait Test for PLS-MGA

H7 is about testing the moderating effects of fear perceived by members. To test H7, we divided the sample into two groups based on the average value for a member’s fear perception (=2.988). The high-level of fear group (>2.988) includes 170 respondents (mean = 3.866, SD = 0.848). The low-level of fear group (<2.988) includes 126 respondents (Mean = 1.804, SD = 0.619). Two groups’ demographic characteristics are addressed in Table 1. The moderating effects of fear were analyzed by adhering to the test processes supported by a multi-group analysis (MGA) mechanism [65]. However, before conducting the MGA test, we need to conduct the Welch-Satterthwait t-test to address whether a significant parametric significance exists between the groups. The assumption here is that variances and/or sample sizes are unequal across groups [65]. Table 8 provides the computed bias-corrected confidence intervals, which confirm the significant difference of a path coefficient between groups if there is no overlap of the results. Table 8 suggests that two groups (high-level fear group vs low-level fear group) are significantly different, leading us to check MGA results.

Table 8.

Confidence Intervals of Groups by the Level of Fear Perception (bias-corrected).

The MGA results are addressed in Table 9, where all the bold fonts here represent abbreviated words to denote constructs used in our proposed conceptual model as shown in Figure 1. Table 9 reveals that there are no significant differences in effects at p < 0.05 between groups except for the relationship between KS satisfaction and KS continuance intention (|β(fear high)–β(fear low)| = 0.209; p-value (fear high vs. fear low) = 0.040). This implies that fear perceived by members only moderates the relation between KS satisfaction and KS continuance intention. Its implication is that members who perceive a high level of fear are more likely to continue KS with others when they are satisfied with KS in the context of CKN. Detailed discussions will be suggested in the following discussion section.

Table 9.

Multi-group analysis (MGA) Results.

4. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Our findings can be summarized as follows. Firstly, a sense of competition is a driver motivating knowledge seeking intention rather than knowledge contributing intention. Secondly, altruism affects both knowledge contribution and seeking intentions. Thirdly, the two constructs belonging to the sense of virtual community, i.e., feelings of membership and feelings of influence play as a driving force for knowledge contributing intention rather than knowledge seeking intention. Fourthly, the path of KS intention-satisfaction-continuation was statistically significant. Fifth, fear is a key driver for both KS satisfaction and KS continuance intention, all of which are significant factors for the sake of sustaining the CKN.

Based on the findings above, let us discuss below the implications one by one. First of all, let us first focus on the implications of altruism. For the sake of promoting both knowledge contribution and seeking intentions, the altruism turns out to be the only one influencing factor. For the CKN to remain sustainable, both knowledge creation and knowledge seeking intentions should stay robust and active. From that point on, how to motivate and retain the altruism among members in the CKN proves crucial to activate both knowledge creation and knowledge seeking intentions. This finding is valuable when considering the previous studies in which either knowledge contribution or knowledge seeking intention was stressed without noticing the importance of stimulating both of them.

Both feelings of membership and feelings of influence represent the sense of virtual community that is prevailing in the CKN. Our results revealed that they affect only the knowledge contributing intention. We interpret that this result is caused by the fact that as shown in Table 1, the KS activity duration period for almost 50% of participants (n = 136) is below one year, and they seem just beginners in terms of KS activities. This implies that new entrants are likely to do something good for the sake of other members by spending a considerable amount of time and effort to strengthen their identity within the CKN [1]. Those fresh members tend to get indulged in knowledge contribution activities as a way of impressing others about their existence and identity in the CKN.

The sense of competition proved to simulate the knowledge seeking intention, while it had nothing to do with the knowledge contributing intention. A basic nature of the CKN is that there is no explicit reward for knowledge seeking and contribution. Furthermore, the CKN is implicitly full of competition among members. All of the CKN characteristics like these contribute to restricting members’ KS activities to some extent, especially knowledge contributing intention is hampered [7,9].

Our result is consistent with previous studies that have shown that KS satisfaction is an essential factor leading to motivate individuals to continue KS intention [40,42,43]. However, one of our research questions was to verify the moderating effects of fear on members’ KS attitudes in the context of CKN. Basically, fear had a significantly positive effect on the relation between KS satisfaction and KS continuance intention. We know that the nature of fear is generically related to anxiety about losing one’s unique value [13] and being possibly defeated by a rival [12]. Therefore, it is easily predictable that members who have a sense of fear about the consequences after sharing their valuable knowledge in the competitive online community like CKN would be less likely to continue KS. Especially, such a sense of competition among members is high in the target CKN from which we collected the data sample. Most of the members in the CKN are worried about a low rate of success in passing their target exams, and therefore, it is no surprise that they feel a strong sense of competition. In competitive situations, people will become more reluctant to share their unique knowledge obtained through relatively long periods of experience about a number of tricky topics of the exams. After all, our results about the role of fear were such that fear perceived by members is playing as one of the crucial moderating factors for KS satisfaction and KS continuance intention. The implication about fear like this would be reemphasized by the fact that fear as one of the negative emotions has been generally regarded as a hindrance to specific behaviors. However, our results demonstrated the possibility that a negative emotion like fear can positively affect the sustainability of the CKN by stimulating KS satisfaction and KS continuance intention.

This study provides a number of managerial implications. Firstly, from an organizational perspective, rather than a virtual community like CKN, managers need an in-depth understanding of employees’ emotional attitudes in order for knowledge sharing to be an effective competitive advantage strategy. Many organizations do not properly sustain KMS (Knowledge Management System) or internal CoP (Community of Practice) for the sake of KS due to insufficient adjustments in the balance between knowledge contributors and knowledge seekers. In that case, it is effective to stimulate their collective emotions such as membership or feelings of influence. In those organizations where knowledge shared by others needs to be actively used for work, it is more desirable to stimulate personal emotions such as a sense of competition. Secondly, the operators of a virtual community, where sustainability is the key to success, should do their best to find a way to maximize their members’ satisfaction. The characteristics of virtual community members differ from those of organizational employees, and benefits such as salary raises, bonuses, promotions, or job security cannot be given as a reward for sharing knowledge. After all, due to the nature of virtual space, knowledge sharers will have greater satisfaction through intrinsic rewards rather than external rewards. This intrinsic satisfaction depends largely on emotionally oriented factors such as pleasure, expectation, and achievement. In particular, as our study shows, careful strategies for negative emotions are required when there exists a complex subtle emotional atmosphere among members, such as a sense of competition.

Out of empirical works, this study can suggest several topics for further study. Firstly, samples need to be collected from multiple CKN sources to compare the empirical results depending on the CKN characteristics. We believe that such an approach may shed more light on unveiling the role of a sense of competition and fear in the context of different types of CKNs. Secondly, another kind of emotion needs to be considered to know how emotions may have effects on members’ KS intentions and attitudes. Thirdly, it is natural that a group of influencing people would emerge when a large number of people get together. Especially, in online situations like the CKN, some members show leading roles in many aspects of KS attitudes. Therefore, future studies need to be done on how those influential members’ enthusiasm and personal behaviors have effects on members’ generic KS attitudes in the CKN. Fourthly, it would be interesting when further studies are done with respect to the CKNs operating in a specific organization. Such CKNs are only open to those people working in that organization and closed to outside members. All the members are basically colleagues working together in the same company. Therefore, quite a new finding may be obtained out of the analysis of a data sample from them even if the same research model is adopted.

Author Contributions

Supervision, K.C.L.; writing—review, K.C.L.; literature review, H.G.J.; data processing and analysis, H.G.J.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Definition of Terms in KS Studies.

Table A1.

Definition of Terms in KS Studies.

| Year | Domain | Platform | Key Construct | Term(s) Defined | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | IT/IS | Electronic medium | Knowledge sharing behavior | “Knowledge sharing refers to an individual converting his or her own knowledge into a form that can be readily understood, absorbed, and employed by others.” | [66] |

| 2019 | Health | Online health communities | Knowledge sharing intention | (Not defined) | [67] |

| 2019 | Marketing | Virtual brand communities | Knowledge sharing | (Not defined) | [32] |

| 2018 | Education | Social networking site | Knowledge sharing | “Knowledge sharing refers to the transfer or spread of knowledge through individuals, groups, or organizations.” | [30] |

| 2018 | SNS | Mobile MSN | Knowledge sharing behavior | “The term knowledge sharing is defined as the sharing of community-related information, ideas, suggestions and expertise among individuals.” | [68] |

| 2017 | Education | Virtual communities | Knowledge sharing intention | (Not defined) | [69] |

| 2017 | Marketing | Virtual innovation community | Knowledge sharing behavior | (Not defined) | [70] |

| 2017 | Health | Online health Q&A communities | Knowledge sharing intention | “Knowledge sharing is the act of sharing ideas, experiences, information, and skills between individuals and desired persons.” | [26] |

| 2017 | Health | Online health communities | Knowledge sharing intention | “Knowledge sharing in health care services refers to the transferability of knowledge between the key producers (e.g., physicians and patients) of a service.” | [71] |

| 2016 | IT/IS | Social Q&A sites | Knowledge sharing behavior | (Not defined) | [72] |

| 2016 | Education | Online test community | Knowledge sharing behavior | “Knowledge sharing referred to knowledge or information dissemination and distribution by one person to other members.” | [73] |

| 2016 | Tourism | Online travel communities | Knowledge sharing | “Consumer subjective knowledge refers to self-beliefs regarding one’s knowledge in the domain of consumption.” | [74] |

| 2016 | Health | Online health communities | Knowledge sharing | “Knowledge sharing is a kind of exchange behavior.” | [75] |

| 2016 | Game | Online game community | Innovation-related knowledge sharing | "Innovation-related knowledge sharing is the extent to which a game user shares his or her innovation-related knowledge with other members of the user community." | [76] |

| 2015 | IT/IS | Virtual communities | Knowledge sharing intention | (Not defined) | [77] |

| 2015 | Business | Business online communities | Continuous knowledge sharing intention | “Continuous knowledge sharing refers to individual repeated act of sharing knowledge when using a knowledge based information system (i.e., online community).” | [78] |

| 2015 | SNS | Knowledge sharing | “Knowledge sharing is the behavior of an individual disseminating his or her knowledge to other people to solve problems, develop new ideas, or implement policies or procedures.” | [79] | |

| 2014 | Tourism | Online travel communities | Knowledge sharing | (Not defined) | [80] |

| 2014 | Education | A virtual Community of teacher professionals | Knowledge sharing behavior | “Knowledge sharing intention refers to the willingness of individuals within a community or an organization to sharewith others the knowledge they own, while knowledge sharing behavior refers to the individuals’ behaviors of sharing knowledge.” | [81] |

| 2014 | Tourism | Interest online communities | Intention to share knowledge | "Knowledge-sharing intention (KSI): the intention to share knowledge." | [82] |

| 2013 | Education | Virtual communities | Knowledge sharing intentions | “With regards to learning, knowledge sharing means that one becomes genuinely ready to help others, rather than only giving things to others or obtaining things from them.” | [83] |

| 2013 | SNS | Intention to share knowledge | "Intention to knowledge sharing: The degree to which individual believes that individual will participate in knowledge sharing in Facebook Groups" | [84] | |

| 2013 | General-purpose | Virtual communities | Continuance intention to share knowledge | "Knowledge sharing is defined as the sharing of community related information, ideas, suggestions and expertise among individuals." | [85] |

| 2012 | Marketing | Virtual communities | Intention to share knowledge | (Not defined) | [86] |

| 2012 | Business | Weblogs | Intention of knowledge sharing | "We focus on knowledge sharing, which refers to the provision of task information and know-how to help others and to collaborate with others to solve problems, develop new ideas, or implement policies or procedures.” | [87] |

| 2012 | General-purpose | Online photo community | Intention to share knowledge | “Intention to share knowledge indicates an individual’s willingness or readiness to make her knowledge available to others.” | [4] |

| 2011 | General-purpose | A virtual community | Knowledge sharing behavior | “Quality of shared knowledge: The nature and helpfulness of content and knowledge shared in the virtual community. Quantity of shared knowledge: The volume of knowledge posting and viewing in the virtual community.” | [88] |

| 2011 | SNS | Wiki communities | Knowledge sharing intention | “A literature review revealed four primary perspectives for conceptualizing knowledge sharing: communication, learning, market, and interaction.” | [89] |

| 2011 | Education | Online learning platform | Online knowledge sharing behavior | Individual online knowledge sharing behavior is defined as the online communication of knowledge so that knowledge is learned and applied by an individual. | [90] |

| 2010 | Education | Virtual communities | Intention to continue sharing knowledge | (Not defined) | [91] |

| 2010 | Business | online CoPs | Knowledge sharing | “I define knowledge sharing in this study as the activity in which participants are involved in the joint process of contributing, negotiating and utilizing knowledge.” | [92] |

| 2010 | Education | Blog | Knowledge sharing | (Not defined) | [93] |

| 2010 | SNS | Weblogs | Knowledge sharing behavior | “We operationally define knowledge sharing among community members as a process that includes the attempt to transfer knowledge by a sender, the completion of the transfer, and the successful absorption of this knowledge by a recipient.” | [94] |

| 2009 | Business | Professional virtual communities | Knowledge sharing behavior | “Knowledge sharing is defined as a process of communication between two or more participants involving the provision and acquisition of knowledge.” | [95] |

| 2009 | Education | Virtual learning communities | Knowledge sharing intention | (Not defined) | [96] |

| 2007 | Business | Virtual communities of practice | Online knowledge sharing | “Knowledge sharing is defined as a process of communication between two or more participants involving the provision and acquisition of knowledge.” | [97] |

| 2004 | Business | Virtual communities | Knowledge sharing activity | (Not defined) | [98] |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Constructs and Measurement Items.

Table A2.

Constructs and Measurement Items.

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Operationalization | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of competition (COMP) | 1. Members have a ‘win–lose’ relationship. 2. Members’ goals are incompatible with each other. 3. Members are competitive to prepare for the recruitment exam. 4. Members are competitive in trying to get the highest score. 5. Members are trying to outperform others for the exam. | Desire to achieve a better outcome than a comparator other | [7,9] |

| Altruism (ALTM) | 1. When I have the opportunity, I help members solve their posting questions. 2. When I have the opportunity, I orient new members even though it is not required. 3. When I have the opportunity, I give my time to help members when needed. | Voluntary helping actions where one attempts to improve the welfare of others at some cost to oneself | [39] |

| Fear (FEAR) | 1. If I provide everybody with my entire know-how, I am afraid of failing in the exam. 2. I don’t gain anything if I share my know-how. 3. If I share my know-how, I will lose my knowledge advantage. 4. Knowledge sharing means failing in the exam. | Members’ anxiety about giving away valuable knowledge while being offered little in return | [13] |

| Feelings of membership (MSHP) | 1. I feel as if I belong to the virtual advice network. 2. I feel membership in the virtual advice network 3. I feel as if the members of the virtual advice network are my close friends. 4. I like the members of the virtual advice network. | The feelings of belonging and awareness of being part of an integrated network | [1] |

| Feelings of influence (INFL) | 1. I am well known as a member of the virtual advice network. 2. I feel that I control the virtual advice network. 3. My postings on the virtual advice network are often reviewed by other members. 4. Replies to my postings appear on this virtual advice network frequently. | The reciprocal relationship of members and the network in terms of their ability to affect change in each other | [1] |

| Knowledge contributing intention (CTRB) | 1. I intend to contribute my knowledge in the future. 2. My intentions are to contribute my knowledge in the next month. 3. If I could, I would like to contribute my knowledge. | The degree to which members intend to contribute their knowledge to others in the network | [27] |

| Knowledge seeking intention (SEEK) | 1. I intend to seek knowledge in the future. 2. My intentions are to seek knowledge in the next month. 3. If I could, I would like to seek knowledge. | The degree to which members intend to seek other’s knowledge in the network | [27] |

| KS satisfaction (SATF) | 1: I feel very satisfied with my previous experience of knowledge sharing in the virtual advice network. 2: I feel very pleased with my previous experience of knowledge sharing in the virtual advice network. 3: I feel very contented with my previous experience of knowledge sharing in the virtual advice network. 4: I feel absolutely delighted with my previous experience of knowledge sharing in the virtual advice network. | The degree of members’ satisfaction with the result of knowledge sharing behavior | [99] |

| KS continuance intention (CONT) | 1. I intend to continue using my virtual advice network to share knowledge in the future. 2. My intentions are to continue using my virtual advice network to share knowledge in the next month. 3. If I could, I would like to continue using my virtual advice network to share knowledge | The degree to which members intend to continue to share knowledge in the network | [27] |

References

- Chen, G.-L.; Yang, S.-C.; Tang, S.-M. Sense of virtual community and knowledge contribution in a P3 virtual community: Motivation and experience. Internet Res. 2013, 23, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datareportal. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2019-global-digital-overview?rq=Digital2019analysis (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- eMarketer. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/chart/213106/average-time-spent-per-day-with-smartphones-by-adults-south-korea-2015-2019-hrsmins-change (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Erden, Z.; Von Krogh, G.; Kim, S. Knowledge sharing in an online community of volunteers. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2012, 9, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.H.; Ju, T.L.; Yen, C.H.; Chang, C.M. Knowledge sharing behavior in virtual communities: The relationship between trust, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why Should I Share? Examining Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.E.; Ford, D.P.; Turel, O.; Gallupe, B.; Zweig, D. “I’m busy (and competitive)!” Antecedents of knowledge sharing under pressure. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2014, 12, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T.; Mors, M.L.; Løvås, B. Knowledge sharing in organizations: Multiple networks, multiple phases. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 776–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Baruch, Y.; Lin, C.P. Modeling team knowledge sharing and team flexibility: The role of within-team competition. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 947–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A. A configural theory of team processes: Accounting for the structure of taskwork and teamwork. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, Q.; Tjosvold, D. Linking transformational leadership and team performance: A conflict management approach. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 1586–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Sutton, R.I. The Knowing-Doing Gap: How Smart Companies Turn Knowledge Into Action; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 1578511240. [Google Scholar]

- Renzl, B. Trust in management and knowledge sharing: The mediating effects of fear and knowledge documentation. Omega 2008, 36, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.-K. Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Wei, K.K. Understanding seeking from electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical study. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2005, 56, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, M. The Tacit Dimension, Routhledge and Kegan; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I. A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, U.; Kogut, B. Knowledge and the speed of the transfer and imitation of organizational capabilities: An empirical test. Organ. Sci. 1995, 6, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, R.-L.; Tsai, S.D.-H.; Lee, C.-F. The problems of embeddedness: Knowledge transfer, coordination and reuse in information systems. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 1289–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenrieder, I.; Nooteboom, B. Learning groups: What types are there? A theoretical analysis and an empirical study in a consultancy firm. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Noe, R.A. Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartol, K.M.; Srivastava, A. Encouraging knowledge sharing: The role of organizational reward systems. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2002, 9, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Ho, S.H.; Han, I. Knowledge sharing behavior of physicians in hospitals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2003, 25, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulanski, G.; Cappetta, R.; Jensen, R.J. When and How Trustworthiness Matters: Knowledge Transfer and the Moderating Effect of Causal Ambiguity. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Gong, Y. Social capital, motivations, and knowledge sharing intention in health Q&A communities. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1536–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wei, K.K. What drives continued knowledge sharing? An investigation of knowledge-contribution and -seeking beliefs. Decis. Support Syst. 2009, 46, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-N. The impact of knowledge sharing, organizational capability and partnership quality on IS outsourcing success. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, P. Why share knowledge? The influence of ICT on the motivation for knowledge sharing. Knowl. Process Manag. 1999, 6, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.C.; Chang, C.H.; Lian, J.W.; Wang, M.W. Antecedents and consequences of social networking site knowledge sharing by seniors: A social capital perspective. Libr. Hi Tech 2018, 36, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gabbard, J.L. Factors that affect scientists’ knowledge sharing behavior in health and life sciences research communities: Differences between explicit and implicit knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, Y. Social Capital on Consumer Knowledge-Sharing in Virtual Brand Communities: The Mediating Effect of Pan-Family Consciousness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Marqués, D.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Merigó, J.M. Analyzing the effects of technological, organizational and competition factors on Web knowledge exchange in SMEs. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Jin, X.L.; Fang, Y.; Lee, M.K.O. The influence of affective cues on positive emotion in predicting instant information sharing on microblogs: Gender as a moderator. Inf. Process. Manag. 2017, 53, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.-W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-N. Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological factors, and organizational climate. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F.; Lee, G.G. Perceptions of senior managers toward knowledge-sharing behaviour. Manag. Decis. 2004, 42, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reychav, I.; Weisberg, J. Bridging intention and behavior of knowledge sharing. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.H.; Chiu, C.M. In justice we trust: Exploring knowledge-sharing continuance intentions in virtual communities of practice. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O.; Lee, Z.W.Y. Understanding the continuance intention of knowledge sharing in online communities of practice through the post-knowledge-sharing evaluation processes. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2013, 64, 1357–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Feeling the sense of community in social networking usage. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2009, 57, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddibhotla, N.B.; Subramani, M.R. Contributing to public document repositories: A critical mass theory perspective. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; Kankanhalli, A.; Roy, R. The dynamics of sustainability of electronic knowledge repositories. In Proceedings of the ICIS 2007 Proceedings-Twenty Eighth International Conference on Information Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 9–12 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.-M.; Maxwell, T.A. Information-sharing in public organizations: A literature review of interpersonal, intra-organizational and inter-organizational success factors. Gov. Inf. Q. 2011, 28, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F. Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on employee knowledge sharing intentions. J. Inf. Sci. 2007, 33, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.-Y.; Lai, H.-M.; Chang, W.-W. Knowledge-sharing motivations affecting R&D employees’ acceptance of electronic knowledge repository. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2011, 30, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.W.K.; Chan, A. Knowledge sharing and social media: Altruism, perceived online attachment motivation, and perceived online relationship commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abfalter, D.; Zaglia, M.E.; Mueller, J. Sense of virtual community: A follow up on its measurement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, A.L. Developing a Sense of Virtual Community Measure. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.; Kim, Y.-G.; Kim, Y.-G. Sense of virtual community: A conceptual framework and empirical validation. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 8, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.G.; Lee, K.C. An Empirical Analysis of Role of Individual Emotions and Sense of Virtual Community on Users’ Knowledge Sharing Intention. Korean Manag. Rev. 2015, 44, 1473–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H.K.; Lee, K.C. An Empirical Analysis Approach to Exploring the Influence of Positive and Negative Emotions on Individual’s Knowledge Sharing and Utilization Intentions. Knowl. Manag. Res. 2015, 16, 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.G.; Lee, K.C. Influence of individual emotions on intention to share knowledge in competitive online advice communities. Knowl. Manag. Res. 2017, 18, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.G.; Lee, K.C. Investigating Mobile Application Users’ Intentions to Share Knowledge in the Context of a Competitive Knowledge Network. Korean Bus. Educ. Rev. 2019, 34, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and Validity Assessment. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; Beverly Hills Sage Publications: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 1483377466. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1483377385. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Q.; Yang, W.; Shi, Y. Characterizing the relationship between conscientiousness and knowledge sharing behavior in virtual teams: An interactionist approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 91, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Examining users’ knowledge sharing behaviour in online health communities. Data Technol. Appl. 2019, 53, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, M.; Saghafi, F.; Aghayi, E. A multidimensional model of knowledge sharing behavior in mobile social networks. Kybernetes 2019, 48, 906–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.H. Developing an antecedent model of knowledge sharing intention in virtual communities. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2017, 16, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, F.; Lin, M.; Du, H.S. Knowledge sharing among innovative customers in a virtual innovation community the roles of psychological capital, material reward and reciprocal relationship. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 691–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Deng, Z.; Chen, X. Knowledge sharing motivations in online health communities: A comparative study of health professionals and normal users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Detlor, B.; Connelly, C.E. Sharing Knowledge in Social Q&A Sites: The Unintended Consequences of Extrinsic Motivation. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 70–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, D.-K.; Chih, W.-H.; Yuan, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-Y. The study of the antecedents of knowledge sharing behavior. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 845–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Lin, Z.; Zhuo, R. What drives consumer knowledge sharing in online travel communities?: Personal attributes or e-service factors? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H. Knowledge sharing in online health communities: A social exchange theory perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, Y.S.; Kang, M. Extending lead user theory to users’ innovation-related knowledge sharing in the online user community: The mediating roles of social capital and perceived behavioral control. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.; Lai, H.; Chou, Y. Knowledge-sharing intention in professional virtual communities: A comparison between posters and lurkers. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 2494–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, K.F.; Tan, F.B. The mediating role of trust and commitment on members’ continuous knowledge sharing intention: A commitment-trust theory perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.Y.; Tsai, C.C.; Fang, Y.C. Understanding social capital, team learning, members’ e-loyalty and knowledge sharing in virtual communities. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2015, 26, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Reid, E.; Kim, W.G. Understanding Knowledge Sharing in Online Travel Communities. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L.; Fan, H.L.; Tsai, C.C. The role of community trust and altruism in knowledge sharing: An investigation of a virtual community of teacher professionals. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2014, 17, 168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.M.; Chen, T.T. Knowledge sharing in interest online communities: A comparison of posters and lurkers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.W.; Cheng, M.J. Are you ready for knowledge sharing? An empirical study of virtual communities. Comput. Educ. 2013, 62, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, S.M.; Chou, C.H.; Liao, H.L. A study of Facebook Groups members’ knowledge sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Hsu, F.C.; To, P.L. Exploring knowledge sharing in virtual communities. Online Inf. Rev. 2013, 37, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Chau, P.Y.K. Cultivating the sense of belonging and motivating user participation in virtual communities: A social capital perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 32, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, T.; Stamati, T.; Nopparuch, P. Exploring the determinants of knowledge sharing via employee weblogs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 33, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chuang, S.S. Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.T.; Wei, Z.H. Knowledge sharing in wiki communities: An empirical study. Online Inf. Rev. 2011, 35, 799–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.W.K.; Yuen, A.H.K. Understanding online knowledge sharing: An interpersonal relationship perspective. Comput. Educ. 2011, 56, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wei, K.K.; Chen, H. Exploring the role of psychological safety in promoting the intention to continue sharing knowledge in virtual communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Virtual knowledge sharing in a cross-cultural context. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.; Kim, M. What makes bloggers share knowledge? An investigation on the role of trust. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2010, 30, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.K.; Lu, L.C.; Liu, T.F. Exploring factors that influence knowledge sharing behavior via weblogs. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.J.J.; Hung, S.W.; Chen, C.J. Fostering the determinants of knowledge sharing in professional virtual communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.Y.L.; Chen, N.-S. Kinshuk Examining the Factors Influencing Participants’ Knowledge Sharing Behavior in Virtual Learning Communities. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2009, 12, 134–148. [Google Scholar]

- Usoro, A.; Sharratt, M.W.; Tsui, E.; Shekhar, S. Trust as an antecedent to knowledge sharing in virtual communities of practice. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2007, 5, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.; Kim, Y.G. Knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An e-business perspective. Expert Syst. Appl. 2004, 26, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-L.; Zhou, Z.; Lee, M.K.O.; Cheung, C.M.K. Why users keep answering questions in online question answering communities: A theoretical and empirical investigation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).