Abstract

Previous environmental sustainability studies have examined only limited type of pro-environmental behaviour (PEB; e.g., recycling), but have not explored relationships among various types or dimensions of PEBs. This paper explores six types of PEBs (i.e., activist, avoider, green consumer, green passenger, recycler and utility saver) and investigates their antecedents and interrelationships between two ethnic groups—Malays and Chinese in Malaysia. Survey data from 581 respondents, comprising 307 Malays and 274 Chinese, were used to assess the research model. To conduct multi-group analysis, the study used partial least squares structural equation modelling in SmartPLS 3. The study extends the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory by using social norms to predict PEBs. The results suggest that social norms predict each type of PEB, in contrast to other constructs in VBN theory, except for utility-saving behaviours. The findings also reveal some similarities as well as differences between Malays and Chinese, indicating that the two ethnic groups are not homogeneous. The study is the first to simultaneously study six types of PEB and to examine the differences between Malays and Chinese on PEB constructs and offers a valuable contribution to the literature by extending VBN theory to social norms and PEB.

1. Introduction

Environmental sustainability is a topic of increasing concern. Problems related to the environment-for example, air pollution and the degrading biodiversity—have turned into pressing issues for many parties, including the government and business firms as well as individual consumers [1]. Environmental studies (e.g., [2,3,4,5,6]) have narrowed their focus on the influential factors of pro-environmental or green behaviours of individuals. Such pro-environmental behaviours (PEBs) involve actions that can protect the environment from the destructive effects of human activities [7]. Although previous research has examined PEB, only a handful of studies have investigated behaviours by investigating their impacts and association in depth. Green purchasing [8,9] and recycling behaviours [10,11,12] appear to be the common aspects evaluated by many, yet these studies simultaneously disregard the varied dimensions of the PEB sphere, as well as other probable significant correlations. Such disregard for the other dimensions may cause issues in interpretation, considering that those concerned about the environment are usually associated with multiple green activities [13]. For example, users of organic produce may participate in green events and commute via public transport, meaning that the purchase of organic products contributes little to preserving the environment. Hence, in order to gain a more holistic view of PEB, an investigation of its varied elements is essential to describing the sustenance of the ecosystem [14]. Consequently, this study examines six types of PEBs, their antecedents and their interrelationships.

Furthermore, as depicted in numerous studies, green behaviours of consumers are related to individual factors such as socio-demographics, values, beliefs and norms [7,15,16]. One theory that combines these factors is the Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) theory [7]. According to VBN theory, green behaviours are more likely to occur when a causal series of variables (i.e., values, beliefs and personal norms) is present. Among all constructs in the VBN model, personal norms have been found to be a successful antecedent of PEB in different settings. Although recent studies have examined the influence of personal norms on PEB [7,15,17,18], few have investigated the influence of social norms simultaneously. To comprehensively understand behavioural intentions regarding PEB, both personal and social norms should be considered [16]. Previous studies have shown that individuals are more likely to engage in certain behaviours when they believe that their family members, relatives, friends, neighbours and colleagues will value those actions [16,19]. This notion is supported by Han et al. [20], revealing that social norms have a direct positive effect on green behaviour. Although VBN theory explains and predicts PEB behaviour rather than pro-environmental intentions [7,15,16,21], there is limited research examining PEBs as dependent variables when applying VBN theory. While intentions may not be precise and reliable measures of behaviour, individuals still might not engage in a defined behaviour even while demonstrating a strong intention to do so. Thus, this paper focuses on PEBs, rather than intentions, to produce insightful findings.

Finally, only limited studies have examined the influential factors of PEB across ethnicity, particularly within the Asian region. Past studies of PEB were conducted mainly in the West and specifically in the US, with most of the assessments focusing on Whites, Blacks and Hispanics, hence suggesting bias. Nonetheless, the number of studies conducted among the Eastern nations has also increased, especially in Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan and China. However, these nations have an almost homogeneous ethnicities, which refers to the dominance of one particular ethnic group amongst the population. Malaysia, on the other hand, is a melting pot of diverse ethnic groups, with Malays (55.1%) and Chinese (23.7%), as well as other minority ethnic groups (21.2%) living in harmony amidst varied cultures, beliefs and practices within the shared social sphere [22,23]. Moreover, although the Malays and the Chinese, as the two major ethnic groups in Malaysia, have co-existed since the early 19th century, marketing studies have rarely compared these two ethnic groups. Comparative analyses regarding PEB within the context of ethnicity are scant, as most scholars have preferred to explore the impacts of other demographic elements, for instance, gender, age, income and level of education [24]. In so doing they have dismissed the well-reckoned significance of identifying PEB and its related variables among the stretched ethnicities [25]. As such, this study attempts to bridge this research gap by conducting a comparative analysis between the Malay and Chinese ethnic groups with regards to PEB, through the extended VBN theory. Specifically, Malay and Chinese ethnic groups in Malaysia were considered particularly interesting, as their PEBs are often performed to shape social identity and develop interpersonal interaction [20]. Accordingly, the present study extends VBN theory by using social norms to attempt in explaining PEB among Malay and Chinese ethnic groups.

In this way, this work seeks to develop a robust model to enhance comprehension regarding PEB among the Malays and Chinese ethnic groups. The variances found in the PEB antecedents and interrelationships of PEB between these ethnic groups are explored based on VBN theory and social norms (i.e., extended VBN theory). The specific objectives of this study are as follows:

- ▪

- To investigate disparities in interrelationships between Malay and Chinese ethnic groups via the VBN model (i.e., values, beliefs and personal norms);

- ▪

- To examine differences in PEB between Malay and Chinese ethnic groups, based on the extended VBN model (i.e., social norms) and personal norms; and

- ▪

- To explore the multidimensional structure of PEB among Malay and Chinese ethnic groups.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Pro-Environmental Behaviours

PEBs are defined as any actions that can protect the environment as a whole and/or a specific ecosystem from the destructive effects of human activities [1,7]. This definition is sufficiently broad to explore a range of related behaviours [13]. However, Stern [7] and Lee et al. [13] conceptualised PEB as a one-dimensional, undifferentiated construct, though there are distinct types of PEB and several causal factors that influence them. Cleveland et al. [14], who examined 50 items measuring self-reported environmental behaviours, identified the following six types of PEB that encompass distinct characteristics: activist, avoider, green consumer, utility saver, recycler and green passenger (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of six types of PEB.

2.2. Socio-Demographic Variable—Malay Vs. Chinese Ethnic Groups

Hofstede [26,27,28] introduced the concept of national culture, whereby nations are assumed to be homogenous and mono-cultural. However, other researchers have argued that this assumption is fundamentally flawed and that several countries such as Malaysia are multi-cultural and research should therefore account for within-country cultural heterogeneity [29,30]. This study focusses on two dominant ethnic groups, Malays and Chinese, which together constitute almost 90% of Malaysia’s population and are a sufficiently large sample to represent the residents of Malaysia. Several studies have demonstrated that the Malays and Chinese in Malaysia show dissimilarities in their patterns of behaviour when observed and studied using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions [31,32,33]. For instance, religiously, the Malays are mostly Muslims, whereas most Chinese follow Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, and Christianity. In addition, in comparison, Malays are more cohesive, are deeply concerned with family welfare, tend to respect authority, are “ever ready to submit to the authorities and even to sacrifice for the group” ([32], p.184) and are mindful of others’ perspectives. The Chinese, on the other hand, are more individualistic, focus on their own success, and are more cost-conscious, rational and open to uncertainties [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Also, Idris [40,46] demonstrated that Malay women entrepreneurs were significantly different from the Chinese with regards to uncertainty avoidance, which in turn affects certain behaviour. Another study in Singapore also identified some differences between the Malays and Chinese. Malays scored more in attitudes towards traditional values and beliefs and were more socially sensitive compared to their Singaporean Chinese counterparts [37,41]. All these dissimilarities indicate the unique and disparate characteristics of the Malay and Chinese ethnic groups in Malaysia, which this study will explore in relation to PEB.

2.3. Value-Belief-Norm Theory

The VBN theory was first established by Stern et al. [21] to explain the influence of human values on behaviour in an environmentalist context. This theory posits relationships between values, beliefs, norms, and behaviours in a causal chain [7,16,21]. Value refers to “a guiding principle for any behaviour based on desirable trans-situational goals, which vary by relative importance” ([47], p. 21). For the value components, altruistic values, biospheric values, egoistic values, and openness to change values were proposed, based on Schwartz’s [47,48,49] theory of basic values [7,21]. Altruistic value is a collective value concerning other people and living species which motivates people to engage in PEB [1,7]. The second type of value, biospheric, emphasises the biosphere, the environment, and the ecosystem [1,21], while the third type of value, egoistic, refers to self-interest in regard to society, which includes wealth, authority, and being influential [21]. Last, but not least, openness to change refers to stimulation and self-direction based on the motivation of independent thought and action, which conflicts with the motivation of fulfilling others’ expectations [21,49,50]. Value structure is complex and can often include different variables segmenting PEB motivation within a culture [1,7,21]. Thus, these values delineate the possibilities of segmentation between Malay and Chinese ethnic groups.

Sanchez et al. [51] used VBN to examine how personal values determined the willingness to pay for the reduction of noise pollution. However, their study took three values—biospheric, egoistic and altruistic—but did not examine beliefs and norms. Although a direct relationship between value and behaviours can be drawn, this relationship is stronger when there are other mediating variables, such as specific beliefs or personal norms [7,16]. Belief refers to one’s thoughts about the natural environment and human behaviour, and has two components. The first is awareness of consequences, which refers to the belief that environmental circumstances will either improve (to the benefit of all) or threaten other people, other species or the biosphere [1,7,21]. Choi et al. [16] also define awareness of consequences as the consciousness of adverse consequences for the environment that individuals’ value so greatly. In the VBN framework, awareness of consequences precedes the second belief construct, i.e., ascription of responsibility. Ascription of responsibility is a belief that an individual’s actions can either prevent or promote potentially undesirable consequences [1,21]. It could also be described as one’s own sense of responsibility to minimise negative environmental consequences [16].

When individuals hold enduring beliefs and ideals that are essential to preserving the environment, pro-environmental sentiments lead to personal norms for such individuals [52]. Personal norms are feelings of moral obligation to preserve the environment [1,53]. They also refer to the expectation that one is ethically obliged to engage in PEB [16] after recognising the consequences of certain behaviours and the efforts one can make to alleviate those consequences [17].

Awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms are three variables of a norm-activation model that has been empirically validated by many studies [17,20]. For example, Kiatkawsin and Han [1] showed that values influence beliefs, with New Ecological Paradigm as the first belief, which in turn effects the second: Awareness of Consequences. In the context of green tourism, Han [54] found that ascription of responsibility fits the VBN model better than other constructs, while Personal Norms have also been identified as being a successful antecedent of PEB in many contexts [15,55,56,57]. Even though the relationships among all constructs of the VBN model often generate statistically significant results, the predictive power remains in question, in contrast to other theories such as the theory of planned behaviour [1].

At the end of the causal chain, the final construct tested in this study measures PEB. PEB constructs such as Activist, Avoider, Green Consumer, Green Passenger, Recycler, and Utility Saver are hypothesised to be influenced by personal norms [7,21]. Past research has shown that Malay and Malaysia Chinese ethnic groups are somewhat dissimilar in terms of culture and lifestyle (see e.g., [31,32,33,36,40,41,43,58]). These dissimilarities may lead to varying levels of strengths in the relationships among VBN constructs as well as their influence towards the adoption of PEBs. This leads to the following hypotheses (H1a–H12a and H1b–H12b) which propose, in a general sense [59], that different ethnic groups in Malaysia will act as a moderator between relationships in the model:

- H1a,b: The strength of the relations between altruistic value and awareness of consequences is different between Malays and Chinese.

- H2a,b: The strength of the relations between biospheric value and awareness of consequences is different between Malays and Chinese.

- H3a,b: The strength of the relations between egoistic value and awareness of consequences is different between Malays and Chinese.

- H4a,b: The strength of the relations between openness to change and awareness of consequences is different between Malays and Chinese.

- H5a,b: The strength of the relations between awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility is different between Malays and Chinese.

- H6a,b: The strength of the relations between ascription of responsibility and personal norms is different between Malays and Chinese.

- H7a,b to H12a,b: The strength of the relations between personal norms and PEBs (i.e., Activist, Avoider, Green Consumer, Green Passenger, Recycler and Utility Saver) is different between Malay and Chinese.

2.4. Extended Value-Belief-Norm Theory

Many researchers have used VBN theory to predict PEB, but few have suggested that social norms are also an important antecedent to such behaviour [16]. Consequently, the model is extended by adding social norms to examine their effects on PEB. Social norms represent the social pressures that an individual experience from significant others or from society at large to engage in a specific behaviour [60]. People influenced by Social norms are more likely to acquiesce to the opinions or advice given by significant others, such as family members, close friends, colleagues and peers [6,16,19,61,62,63]. While the relationship between personal norms and PEB has been established, this relationship could be considerably stronger when social norms are adopted as a mediating variable [64,65]. Recent studies have also suggested that a strong social consciousness has direct effects on PEB [65]. According to such research, both the personal norms and social norms that influence individuals’ decisions are better explanations for their PEB [64,65,66]. In conclusion, personal norms have a positive influence on social norms if an individual’s personal benefits are in accord with societal benefits [66], while social norms positively influence PEB [65]. Hence:

- H13a,b: The strength of the relations between personal norms and social norms is different between Malay and Chinese.

- H14a,b to H19a,b: The strength of the relations between social norms and PEBs (i.e., Activist, Avoider, Green Consumer, Green Passenger, Recycler and Utility Saver) is different between Malay and Chinese.

3. Methodology

3.1. Respondent and Data Collection Procedure

The purposive sampling method was used to collect the data via a survey questionnaire. Also known as judgment sampling, this sampling technique involves the deliberate choice of participants due to the qualities the participant possesses and is a non-random technique [67]. It was selected as it does not need underlying theories or a set number of participants. For this study, green consumers represented our target respondents for the research questionnaire survey. The target sample’s main criterion was, to live and work in the Klang Valley of Malaysia as most green consumers are located urban areas [4,5,6]; the second criterion was to have used green products recently, and a third criterion was to be able to name a green product purchased or consumed recently. The last two criterions were used as filter questions to ensure that the respondents were green consumers. Though it may not result in a good generalisation of the population, it was considered an acceptable option because the lack of available databases of green consumers in Malaysia means that randomization would have been impossible. During the pre-test, 12 sets of questionnaires were distributed to marketing experts and selected respondents. This was followed by a pilot test with 40 respondents, the aim of which was to assess unseen errors in the questionnaire that might have affected the finding’s reliability and validity. Initially, data was collected via printed surveys distributed at environmental events such as Grub Cycle roadshows. However, to improve the number of responses, an online questionnaire survey was conducted using Google Forms. Seven hundred completed questionnaires were collected, but 119 were excluded because of incomplete answers (i.e., missing values), outliers and exaggerated data. Thus, 581 respondents were retained for analysis, comprising 307 Malays and 274 Chinese.

Non-response bias refers to whether bias exist between the responder and non-responder with regards to their demographic profile or/and attitudinal constructs [68]. As for this study, using the purposive sampling method has partially solved the non-response bias issue as the decision was made to choose respondents of certain characteristics as the target population. Furthermore, an independent sample t-test was also conducted to investigate this bias. Results of the t-test suggest that there is no mean difference between printed and online questionnaires responses as well as between early respondents (responses received in the first week) and late respondents (responses received in the last week) [59]. These provide justification that non-response problem is not a major concern in this study.

A marker-variable analysis was conducted to examine the possibility of the common method variance [67]. Correlational differences between the original framework and a marker-variable added framework were lower than 0.3, suggesting that common method bias was not a concern in this study [69,70].

3.2. Construct Measurement Development

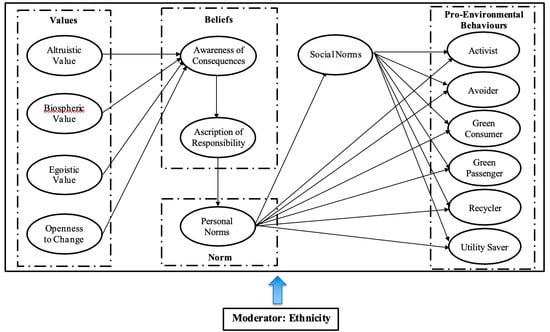

Table 2 shows the constructs, items and sources from decades of research that were used to construct the survey. The questionnaire included four sections: a filter question (section A), factors that affect PEB (section B), PEB (section C) and demographics (section D). For sections B and C, a six-point scale was used that ranged from very unimportant/strongly disagree/never (1) to very important/strongly agree/always (6) because it could not generate moderate degrees of agreement, in contrast to scales that have an odd number of ratings [71]. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework for this study.

Table 2.

Measurement instruments and sources.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3.3. Data Analysis

To assess the research model and conduct multi-group analysis (MGA), partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was used. SmartPLS 3.0 [76] was used to analyse the data. PLS-SEM is a comprehensive multivariate method that analyses each relationship between constructs in a conceptual model concurrently and supports MGA [77,78].

The analysis indicated that the data were multivariate abnormal—Mardia’s multivariate skewness (β = 18.172, p < 0.01) and Mardia’s multivariate kurtosis (β = 240.94, p < 0.01)—suggesting that a non-parametric SEM such as PLS-SEM was appropriate [79]. Reinartz et al. [80] identified 100 samples as the sampling threshold for PLS-SEM, indicating that sample sizes of 307 and 274 are adequate for the technique. G*Power was used to determine the minimum sample required, with 64 cases at the recommended size to achieve a statistical power of 0.8. Samples for both Malay (n = 307) and Chinese (n = 278) participants were greater than the suggested minimum; hence they were acceptable sample sizes.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 3 shows the profile of respondents for the two groups. The total sample of 581 respondents comprised 307 Malay and 274 Chinese participants. There were more female respondents in both the Malay (291) and Chinese (162) ethnic groups. The majority of respondents were between 18 and 35 years of age, and approximately 97% had completed tertiary education. There were more Malay females, younger, bachelor’s degree holders compared to the Chinese respondents. However, there were more single Chinese respondents. This is consistent with another study by Ghazali et al. [4] examining the green purchase behaviour of Muslim consumers in Malaysia and Indonesia, where most respondents were female, single, were bachelor’s degree graduates and employed. Roberts [81] also concluded that environmentally conscious consumers are likely to be female and be more educated.

Table 3.

Sample characteristics.

4.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

The evaluation of the measurement model included the assessment of the validity and reliability of the model’s latent variables.

4.2.1. Formative Constructs

Formative measurement assumes that observed indicators determine the characteristics of a latent variable. The PEB constructs (i.e., Activist, Avoider, Green Consumer (GreenCons), Green Passenger (GreenPass), Recycler and Utility Saver (UtilSav) were treated as formative variables [14]. Confirmatory tetrad analysis was used to confirm causal directions between constructs and indicators before conducting formative measurement model evaluation.

The confirmatory tetrad analysis results for PEB constructs Activist, Avoider, GreenCons, GreenPass, Recycler, and UtilSav matched those of Cleveland et al. [14], which demonstrate formative-type measurement. To achieve convergent validity and reliability, some items from GreenCons (i.e., GC6, GC9, and GC12) and one of GreenPass (i.e., GP3) were deleted due to variance inflation factors (VIFs) greater than 5 [78]. Table 4 demonstrates that all outer weights for constructs measured formatively ranged from 0.005 to 0.689, and all VIFs were lower than 5 for both groups, indicating the satisfactory convergent validity of the formative measurement model [78,82].

Table 4.

Convergent validity of formative constructs of PEBs.

4.2.2. Reflective Constructs

The variables within the VBN framework in the model (i.e., Values—Altruistic (AL), Biospheric (BV), Egoistic (EV), Openness to Change (OC); Belief—Awareness of Consequences (AC) and Ascription of Responsibility (AR); Norms—Personal Norm (PN) and Social Norm (SN)) were all reflective in nature. To achieve convergent validity and reliability for all latent variables in the reflective measurement model, some items were deleted (AL6, EG1, OC1, OC2, OC3, OC4, PN1, PN2, and PN3) because they had a loading of less than 0.7 [78]. Table 5 shows that all loadings and composite reliability values were greater than 0.7, and average variances extracted were greater than 0.5 for the two groups, indicating the satisfactory convergent validity of the reflective measurement model [78].

Table 5.

Convergent validity and reflective measurement model.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

In terms of the discriminant validity for assessment of the reflective constructs, two approaches were used. First, the items’ loadings were examined and no cross loading with higher values was found with opposing constructs. Second, the most conservative discriminant validity test available to date was applied [83]: the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations [84]. Table 6 indicates that the outcomes of the HTMT criterion were below the critical value of HTMT0.85 for both groups, thus indicating acceptable discriminant validity [84].

Table 6.

Discriminant validity via Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT)—reflective constructs.

4.4. Structural Model Evaluation and Hypothesis Testing

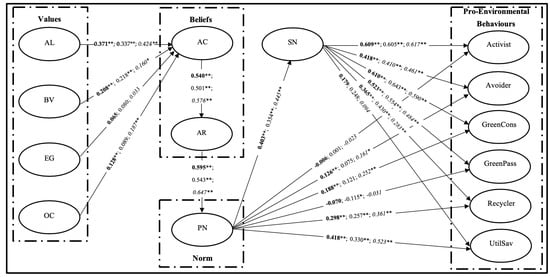

To examine the validity of the structural model, a bootstrapping procedure was used with 5000 bootstrap resamples [78]. Structural models for both Chinese and Malay participants were assessed using PLS-SEM. Standardized betas and explanatory power (R2) are shown in Figure 2. R-squared for all endogenous constructs, except SN and AV, was greater than 0.2 for both groups, indicating substantial explanatory power [78]. GreenCons demonstrated the greatest explanatory power in the Chinese (54.4%) and Malay (48.3%) sub-samples.

Figure 2.

Results of the structural model. (Notes: Full sample = bold font, Malay sample = normal font, Chinese sample = italic font. AC = awareness of consequences, AL = altruistic values, AR = ascription of responsibility, AT = activist, AV = avoider, BV = biospheric values, EG = egoistic values, GreenCons = green consumer, GreenPass = green passenger, OC = openness to change, PN = personal norms, SN = social norms, UtilSav = utility saver. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.).

Effect size (f2) was assessed to identify the statistical significance of the measures. Table 7 indicates that differences in the measures achieved at least a small effect size of f2, 0.02 [85]. The table also indicates that all ten endogenous variables attained predictive relevance because their Q2 values were greater than zero [78]. Thirteen hypotheses were supported in the Malay sub-sample, and fifteen in the Chinese sub-sample (Table 7). In the Malay sample, all value constructs influenced beliefs (except for EG and OC on AC), belief constructs influenced PNs, PNs influenced SNs and PEB (excepting Activist, Avoider, and GreenCons), and SNs influenced PEB (excepting UtilSav). Hence, H1a to H19a were supported, except for H3a, H4a, H7a, H8a, H9a, and H19a. For Chinese participants, the results suggest that all value constructs influenced the belief constructs (except for EG on AC), belief constructs influenced PNs, PNs influenced SNs and PEB (except for Activist and GreenPass) and SNs influenced PEB (except for UtilSav). Therefore, H1b to H19b were supported, but H3b, H7b, H10b and H19b were not.

Table 7.

Results of hypothesis testing for direct relationships.

4.5. Multi-Group Analysis

Prior to performing the MGA, measurement invariance of composites (MICOM) was used to test the measurement invariance of a model across the two groups [77,78].

Table 8 displays the partial measurement invariance on all constructs for both groups, indicating a need to compare differences between Malay and Chinese ethnic groups using MGA. The results displayed in Table 9 reveal the significant differences between Malay and Chinese ethnic groups for six of the relationships. Based on the results of the MGA (Table 9), it was found that the positive impact of OCs and ACs (H4); ACs and ARs (H5); AR s and PNs (H6); PN and GreenCons (H9); and PNs and UtilSav (H12), are stronger for the Chinese group. However, the relationship between SN and Recycler (H18) was identified as being stronger for the Malays.

Table 8.

Results of invariance measurement testing using permutation.

Table 9.

Results of Multi-Group Analysis.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study compares Malay and Chinese ethnic groups in Malaysia vis-a-vis the effects of values, beliefs, PNs and SNs on PEBs. The MGA results demonstrate that there are differences and similarities between the Malays and Chinese ethnic groups. They were similar with regards to 12 of the relationships. However, there were differences between the two groups with regards to seven of the hypothesised relationships. This indicates that even though there are similarities, the two groups are not completely homogenous.

This is specifically true with regards to the relationships between the Values, Belief and Norm constructs, where there are differences between the two groups in three out of the six hypothesised relationships, namely, between OC and AC, AC and AR and between AR and PN. This is consistent with the findings of Han [20] and Stern [7]. The results suggest that Chinese score higher in these relationships than the Malays. As for the similarities between the two groups, there were no differences between the two groups with regards to three of the hypothesised relationships, namely ALs and ACs (H1), BVs and ACs (H2) and EGs and ACs (H3). In H3, the relationship is not significant for both Malays and Chinese. The results indicate that values have an influence on how consumers become aware of the adverse consequences for the environment due to various factors such as pollution, climate change, etc. This is in line with Kiatkawsin and Han [1] whose findings reveal that values influence beliefs.

The results also indicate differences in the effects of OCs on ACs between the Malay and Chinese ethnic groups. OCs positively influenced AC for Chinese, but for Malays there was no significant relationship. Past studies have shown that OCs motivate people to engage in PEBs [12,21]. The findings of this study also corroborate recent studies of ethnic groups, in which the Chinese are more willing to accept and experience new things [32], such as PEBs, in order to reduce environmental degradation. However, the relationship between EGs and ACs are not significant for both groups. This result is inconsistent with past studies that suggests the negative influence of egoistic values on environmental attitudes and behaviours [7,17]. However, Kiatkawsin and Han [1] and Stern et al. [21] also found that the relationship between EGs and ACs was non-significant. This might be due to other variables which were not included in the model [1]. Nevertheless, the non-significant relationship between EGs and ACs is evidence that social power, wealth, and authoritative power does not lead to environmental attitudes and behaviours, and this is true for both ethnic groups [86].

Furthermore, the findings suggest differences between the effects of PNs on GreenCons, and UtilSav across groups. The results indicate two relationships, namely the effect of PNs on GreenCons and UtilSav are higher for the Chinese. The effect of PNs on GreenCons was also not significant for Malays. The results may suggest that the Chinese have a stronger tendency to be recognised as ecologically conscious or green consumers. These findings are consistent with some past findings, which reports that the Chinese are more engaged in PEBs and specifically that the consumption of green products is higher compared to the Malays [25]. Other ethnic culture research also indicates that the Chinese rely more on personal norms to be guided and motivated towards PEBs [32]. At the same time, the results of the analysis also suggest that the effect of PNs on the various PEB dimensions are similar for Malays and Chinese. However, the relationships were not significant for both Malays and Chinese with regards to the effect of PN on Activist, while it was only significant for the Chinese for the effect on Avoider. On the other hand, the effect of PNs on GreenPass was not significant for Chinese. It should be noted that Malaysia’s sustainable public transportation systems are not as well established, causing many people to prefer private transportation [87]. The relationship between PNs and Recycler was significant for both Malays and Chinese, meaning that both races had favourable feelings towards recycling.

Ghazali et al. [6] and Suhaimee et al. [25] also suggested that the Chinese prefer eco-friendly products (which are often sold at a premium) due to their healthy lifestyle, frequent promotion by non-profit organisations, and the environmental benefits such products offer. Furthermore, most organic companies in Malaysia today were founded by Chinese entrepreneurs. This includes Natural Health Farm Marketing (M) Sdn Bhd (Dr. Jessie Chung), BMS Organics (Dr. K.B. Lee), Alive Organic Sdn Bhd (Lilin Teh, and Signature Snack Sdn Bhd (Edwin Wang).

As for the effect of social norms on PEBs, the findings indicate that the two ethnic groups were similar for five of the relationships and only differed with regards to Recycler, meaning that Malays in this sample had a stronger tendency towards recycling due to social norms, seen as socially good conduct. The results suggest that PEB was affected by SNs across both groups, which supports past research findings which establish a positive relationship between the two dimensions [66]. As indicated by the high significance values, both groups experience the strong influence of SNs on PEB in the presence of interpersonal bonds that consist of symbolic identification in a group [66]. Table 10 summarises the differences between the Malay and Chinese ethnic groups.

Table 10.

Summary of differences between Malays and Chinese as revealed in this study.

5.2. Practical Implications

Despite the long-term co-existence between Malay and Chinese ethnic groups in Malaysia, this study suggests that these two groups exhibit certain dissimilarities regarding attitudes, behaviours and decision-making. Marketers should therefore pay attention to the drivers of PEB so that marketing strategies can be made more appealing to target audiences in specific ethnic groups. Advertisement messages and channels should be designed and implemented to reach targeted ethnic groups. For example, since this study has established that Chinese are especially open to change and are highly accepting of new things, marketers should introduce innovative environmental ideas, such as “pray green” campaigns, to discourage the burning of joss sticks and paper offerings during Chinese praying rituals. On the other hand, this risk offending some Chinese devotees, just as Catholic churches replacing real votive candles with electric light bulbs offends some worshippers. Sometimes, symbolism and ambience are everything.

The results also indicate practical implications for those authorities responsible for environmental conservation. Since findings suggest that Chinese ethnic groups more readily engage in PEB than do Malays, local authorities should strengthen the drivers of PEB among Chinese, while educating and influencing Malays via those same drivers. Educational talks regarding environmental preservation should be held frequently in schools so that students can learn to practice PEB during their early years. Different pro-environmental activities can be organised in residential areas to encourage PEB among both Chinese and Malay ethnic groups.

The results suggest differences between the groups regarding the effects of PNs on GreenCons. To encourage GreenCons habit, using a moral approach alone might not be enough to exert a greater influence [7,21]. Marketers should combine interventions such as a religious approach, a moral approach, education, monetary rewards, and community management [7] to motivate green consumerism. An example is providing financial incentives while educating customers about the benefits of using eco-friendly products.

Moreover, this study finds that SNs and PNs affect PEB among both Malay and Chinese ethnic groups. In particular, the study revealed that SN influences Activist, Avoider, GreenCons and GreenPass, while PN influences Recycler and UtilSav. To encourage environmentally friendly behaviours, local authorities should educate both groups about the seriousness of environmental problems and their respective PEB. This approach enhances perceived social pressures for PEB; when people recognise that their efforts is beneficial to the environment, they are more likely to engage in PEB. Marketers should offer incentives, such as donating portions of profits to environmental organisations, through cause-related marketing campaigns to activate consumers’ SNs. Likewise, marketers can promote environmental campaigns through social media such as Facebook, by getting audiences to post, like and share, stimulating their SNs to promote engagement in this kind of activity. For example, Delcea et al. [88] showed that social media exposure can have a high positive impact on eco-friendly product adoption. Bedard and Tolmie [89] also established that social media usage and online interpersonal influence had a significant relationship with green purchase intentions. Using social media influencers may be highly effective for the younger population.

This study identifies six types of PEB which all require special effort or some degree of sacrifice—Activist, Avoider, GreenCons, GreenPass, Recycler and UtilSav. When people have already participated in PEB, they are more likely to repeat such behaviour in the future. Thus, to encourage engagement in the same kind of behaviour in the future, local authorities should target and communicate with those who are already involved in some form of PEB. For example, a sharing session is a good platform for reassuring participants that their positive actions are both meaningful and beneficial to the environment, thus motivating them to repeat specific PEBs frequently.

6. Conclusions

This study contributes to the existing literature by extending the VBN theory to include SNs and PEB, to examine whether there are differences between the Malay and Chinese ethnic groups. The VBN theory offers a good account of the causes of the general predisposition toward PEB. This study also supports the inclusion of social norms in VBN, as this improves the predictive power of the theoretical framework in determining PEB. The result of the MGA analysis demonstrates that though there are similarities, there are indeed some significant differences between Malays and Chinese with regards to the various hypothesised relationships. This indicates that they are not completely homogenous. Several past studies have not accounted for these differences. The findings of this study are also consistent with some past findings, which indicate that the Chinese are more engaged in PEB. Different types of PEB have different causes. Finally, the similarities between the two groups with regards to many of the relationships may indicate that there are fewer differences between the two ethnic groups and that they are moving towards the process of becoming more homogeneous.

Limitations and Future Research

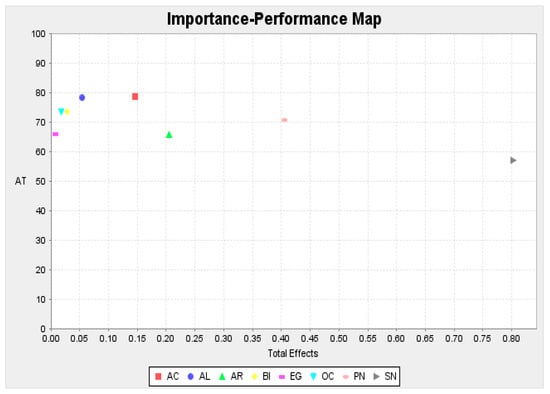

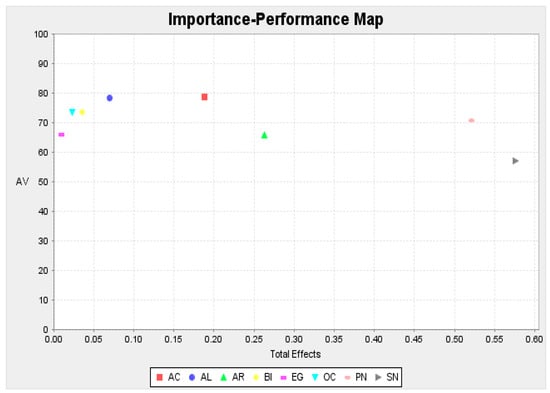

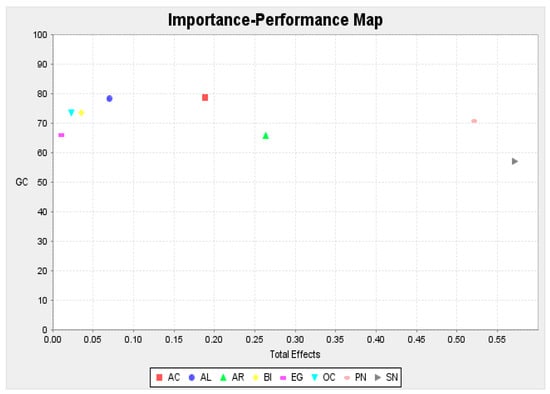

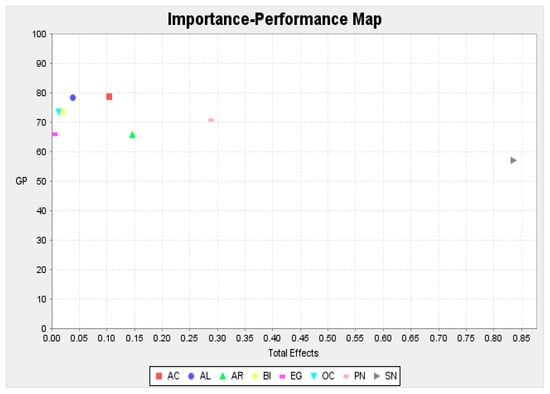

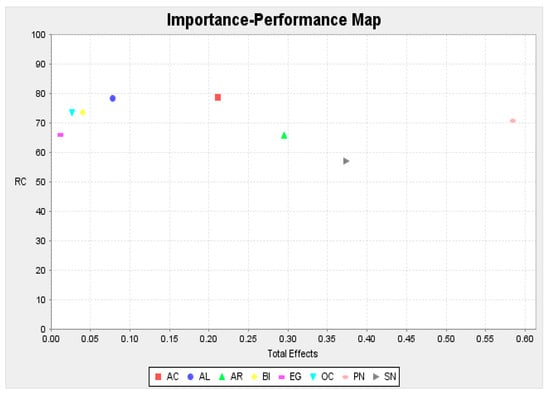

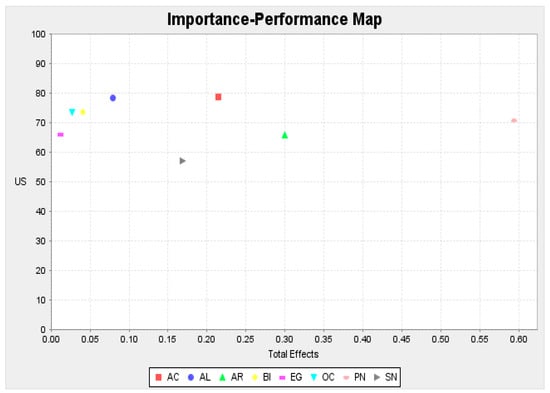

This study focuses only on behaviours beneficial to the environment. Future studies should therefore consider exploring negative behaviours, namely, destructive environmental behaviours and their underlying reasons. This study extends VBN theory using social norms, but other constructs should be considered when measuring PEB. In order to increase the explanatory power of the model, future research should consider integrating variables, such as environmental knowledge and concern, within the conceptual framework. In addition, further empirical examination should be done on the antecedents and influencers of each PEBs, as the exploratory Importance-Performance Map analyses (IPMA) (see Appendix A—Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4, Figure A5 and Figure A6) revealed that social norms and personal norms influence each PEBs with different strengths. For instance, the IPMA result demonstrates that social norms influenced consumers behaviour towards becoming a green activist, an avoider of non-green products, a green consumer and a green passenger, more so than their personal norms. On the other hand, personal norms influenced behaviour towards being a recycler and a utility saver, more so than the social norms.

Purposive sampling was used for this study and the findings may not be generalisable to the entire population. Future studies could try to replicate this study using probability sampling. It is also suggested that future research should consider using qualitative designs in conjunction with quantitative methods to gain deeper insights into the various green behaviour and relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, E.M.G. and S.-F.Y.; Data curation, E.M.G. and S.-F.Y.; Formal analysis, D.S.M.; Funding acquisition, E.M.G. and D.S.M.; Methodology, E.M.G. and S.-F.Y.; Supervision, B.N.; Validation, D.S.M.; Writing—original draft, E.M.G. and S.-F.Y.; Writing—review & editing, E.M.G. and B.N.

Funding

This study was funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme from the Ministry of Education Malaysia (grant number FRGS/1/2016/SS01/UM/02/5), of which Ezlika M. Ghazali and Dilip S. Mutum were the recipients, and Su-Fei Yap was one of the research students. Open Access publication fees were covered by Bang Nguyen from the University of Southern Denmark.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Importance-Performance Map for Activist.

Figure A2.

Importance-Performance Map for Avoider.

Figure A3.

Importance-Performance Map for Green Consumer (GreenCons).

Figure A4.

Importance-Performance Map for Green Passenger (GreenPass).

Figure A5.

Importance-Performance Map for Recycler.

Figure A6.

Importance-Performance Map for Utility Saver (UtilSav).

References

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young travelers’ intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, Y.; Jing, F.; Nguyen, B. Awe, spirituality and conspicuous consumer behavior. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, J.; Jing, F.; Nguyen, B. From Awe to Ecological Behavior: The Mediating Role of Connectedness to Nature. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Mutum, D.S.; Ariswibowo, N. Impact of religious values and habit on an extended green purchase behaviour model. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisbowo, N.; Ghazali, E. Green purchase behaviours of Muslim consumers: An examination of religious value and environmental knowledge. J. Organ. Stud. Innov. 2017, 4, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazali, E.; Soon, P.C.; Mutum, D.S.; Nguyen, B. Health and cosmetics: Investigating consumers’ values for buying organic personal care products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K. Determinants of Chinese Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Media use, environmental beliefs, self-efficacy, and pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Leveraging factors for sustained green consumption behavior based on consumption value perceptions: testing the structural model. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 95, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Licata, J.W.; McKee, D.; Pullig, C.; Daughtridge, C. The Recycling Cycle: An Empirical Examination of Consumer Waste Recycling and Recycling Shopping Behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 2000, 19, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilg, A.; Barr, S.; Ford, N. Green consumption or sustainable lifestyles? Identifying the sustainable consumer. Futures 2005, 37, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.; Choi, J. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Kalamas, M.; Laroche, M. “It’s not Easy Being Green”: Exploring Green Creeds, Green Deeds, and Internal Environmental Locus of Control. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Marell, A.; Nordlund, A. Exploring consumer adoption of a high involvement eco-innovation using value-belief-norm theory. J. Consum. Behav. 2011, 10, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Jang, J.; Kandampully, J. Application of the extended VBN theory to understand consumers’ decisions about green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Mean or green: which values can promote stable pro-environmental behavior? Conserv. Lett. 2009, 2, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J. Norm-based loyalty model (NLM): Investigating delegates’ loyalty formation for environmentally responsible conventions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics. Press Release: Current Population Estimates, Malaysia, 2014-2016; The Office of Chief Statistician, Department of Statistics: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2016.

- Department of Statistics Population & Demography. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/ctwoByCat&parent_id=115&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09 (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Goh, Y.N.; Wahid, N.A. A review on green purchase behaviour trend of Malaysian consumers. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimee, S.; Ibrahim, I.Z.; Abd-Wahab, M.A.M. Organic Agriculture in Malaysia. Available online: http://ap.fftc.agnet.org/ap_db.php?id=579&print=1 (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage Publication: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putit, L.; Arnott, D.C. Micro-culture and consumers adoption of technology: A need to re-evaluate the concept of national culture. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2007, 2007, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Putit, L.; Muhammad, N.S. Predictors of web-based transactions: Examining key variations within an intra-national culture. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2015, 21, 2068–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, R.; Richardson, S. Cultural values in Malaysia: Chinese, Malays and Indians compared. Cross Cult. Manag. An Int. J. 2005, 12, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.S.F.; Chong, S.S.C.; Sia, B.B.K.; Ooi, B.B.C. Culture and Consumer Behavior: Comparisons between Malays and Chinese in Malaysia. Int. J. Innov. Manag. Technol. 2010, 1, 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wan-Husin, W.N. Cultural Clash between the Malays and Chinese in Malaysia: An Analysis on the Formation and Implementation of National Cultural Policy. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Humanity, History and Society, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 27 June–1 July 2012; IACSIT Press: Singapore, 2012; Volume 34, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, C.; Yaapar, M.S.; Abdullah, N.F.L. Understanding Malay and Chinese work ethics in Malaysia through proverbs. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2017, 17, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastor, K.A.; Jin, P.; Cooper, M. Malay Culture and Personality. Am. Behav. Sci. 2000, 44, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.; Ghazali, E.; Cheng, O.C. Demographics and personal characteristics of urban Malaysian entrepreneurs: an ethnic comparison. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2005, 5, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E. lin The Chinese Malaysians’ selfish mentality and behaviors: Rationalizing from the native perspectives. China Media Res. 2007, 3, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.A.; Rashid, M.Z.A. Perceptions of Business Ethics in a Multicultural Community: The Case of Malaysia. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K.; Kau, A.K. Culture’s Influence on Consumer Behaviors: Differences Among Ethnic Groups in a Multiracial Asian Country. In Proceedings of the Advances in Consumer Research; Kahn, B.E., Luce, M.F., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Valdosta, GA, USA, 2004; Volume 31, pp. 366–372. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, A. Uncertainty avoidance and innovative differences in a multi-ethnic society: A female perspective. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 39, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.F.; Cheung, F.M.; Howard, R.; Lim, Y.H. Personality across the ethnic divide in Singapore: Are “Chinese Traits” uniquely Chinese? Pers. Individ. Dif. 2006, 41, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C.; Yaapar, M.S.; Amir, S. Budi and Malay workplace ethics. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2016, 10, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.Z.; Ibrahim, S. The effect of culture and religiosity on business ethics: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storz, M.L. Malay and chinese values underlying the malaysian business culture. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 1999, 23, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed Azizi, W.; Saufi, R.A.; Chong, K.F. Family Ties, Hard Work, Politics and Their Relationship with the Career Success of Executives in Local Chinese Companies. Malaysian Manag. Rev. 2003, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, A. Ethnicity and Cultural Values: An empirical study of Malay and Chinese Entrepreneurs in Peninsular Malaysia. Sarjana 2011, 26, 22–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Elicitation of Moral Obligation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1970, 15, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.H. Value Priorities and Behaviour: Applying a theory of Integrated Value Systems. Psychol. Values 1996, 8, 119–144. [Google Scholar]

- Parks-Leduc, L.; Feldman, G.; Bardi, A. Personality Traits and Personal Values: A Meta-Analysis. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 19, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.; López-Mosquera, N.; Lera-López, F.; Faulin, J. An Extended Planned Behavior Model to Explain the Willingness to Pay to Reduce Noise Pollution in Road Transportation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, A.; Strutton, D. Marketing mix strategies for closing the gap between green consumers’ pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 563–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Wölfing Kast, S. Promoting Sustainable Consumption: Determinants of Green Purchases by Swiss Consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhorst, J.; Klöckner, C.A.; Matthies, E. Saving electricity – For the money or the environment? Risks of limiting pro-environmental spillover when using monetary framing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Situational and Personality Factors as Direct or Personal Norm Mediated Predictors of Pro-environmental Behavior: Questions Derived from Norm-activation Theory. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 2007, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. Antecedents to green buying behaviour: a study on consumers in an emerging economy. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.; Othman, M.N. Demographic and Psychographic Profile of Active and Passive Investors of KLSE: A Discriminant Analysis. Asia Pacific Manag. Rev. 2004, 9, 391–413. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, C.A.; Stefanini, C.J.; Silva, L.A. da Chapter 9 The Effect of High and Low Environmental Consciousness Regarding Brazilian Restaurants: A Multigroup Analysis Using PLS. In Applying Partial Least Squares in Tourism and Hospitality Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 185–209. ISBN 9781787566996. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R. Altruistic or egoistic: Which value promotes organic food consumption among young consumers? A study in the context of a developing nation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, E.M.; Mutum, D.S.; Woon, M.-Y. Multiple sequential mediation in an extended uses and gratifications model of augmented reality game Pokémon Go. Internet Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englis, B.G.; Phillips, D. Does Innovativeness Drive Environmentally Conscious Consumer Behavior? Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabler, C.B.; Butler, T.D.; Adams, F.G. The environmental belief-behaviour gap: Exploring barriers to green consumerism. J. Cust. Behav. 2013, 12, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, L.J.; Gilmartin, S.K.; Bryant, A.N. Assessing Response Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Web. High. Educ. 2011, 44, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, W.W.; Thatcher, J.B.; Wright, R.T. Doug Steel Controlling for Common Method Variance in PLS Analysis: The Measured Latent Marker Variable Approach. Springer Proc. Math. Stat. 2013, 56, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, S.O. A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point likert scales. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2011, 37, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Wilson, S.; Modi, P. Personality and older consumers’ green behaviour in the UK. Futures 2015, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.R.; Smith, J.S.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J.J. Against the Green: A Multi-method Examination of the Barriers to Green Consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamas, M.; Cleveland, M.; Laroche, M. Pro-environmental behaviors for thee but not for me: Green giants, green Gods, and external environmental locus of control. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781483377445. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, G. Testing the Differential Impact of Structural Paths in PLS Analysis: A Bootstrapping Approach. In New Perspectives in Partial Least Squares and Related Methods; Abdi, H., Chin, W.W., Vinzi, V.E., Russolillo, G., Trinchera, L., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 56, pp. 221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P. Construct Measurement and Validation Procedures in MIS and Behavioral Research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 293–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics Versus Statistics in Discriminant Validity Testing: A Comparison of Four Procedures. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-12-2017-0515 (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khemlani, D.M.; Dumanig, F.P. National Unity in Multi-Ethnic Malaysia: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Tun Dr. Mahathir’s Political Speeches. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Khor, S. Study: KL Has One of The World’s Least Reliable Public Transportation Systems. Available online: http://says.com/my/news/study-kuala-lumpur-s-public-transportation-system-is-one-of-the-worst-in-the-world (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Delcea, C.; Cotfas, L.-A.; Trică, C.; Crăciun, L.; Molanescu, A. Modeling the Consumers Opinion Influence in Online Social Media in the Case of Eco-friendly Products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, S.A.N.; Tolmie, C.R. Millennials’ green consumption behaviour: Exploring the role of social media. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).