Abstract

The metallurgical industry generates substantial amounts of heavy metal-containing solid waste, posing significant environmental and health risks. This study systematically evaluates the environmental behavior and ecological risks of heavy metals in four typical metallurgical wastes: jarosite slag (SW1), electric arc furnace ash (SW2), chromium-containing sludge (SW3), and acid-base sludge (SW4). We demonstrate that particle size fundamentally governs heavy metal mobility, with fine-structured SW1 and SW2 (D50 = 4.76 µm and 1.34 µm) exhibiting enhanced metal mobility and bioavailability. In contrast, coarser SW3 and SW4 particles (D50 = 268.83 µm and 133.94 µm) retain heavy metals in more stable forms. Among all metals analyzed, cadmium (Cd) presents the most severe ecological threat, with acid-extractable fractions reaching 52% in SW2 and 45% in SW3—indicating high release potential under changing pH conditions. Risk assessment confirms high to very high ecological risks for Cd in both SW2 and SW3. Moreover, under acidic leaching conditions, SW1 and SW2 show significantly higher cumulative toxicity than SW3 and SW4. These findings highlight the critical role of waste-specific properties in controlling heavy metal fate and provide a scientific basis for targeted risk management and sustainable remediation strategies.

1. Introduction

The metallurgy industry, a critical sector of the national economy, plays an indispensable role in driving both global economic growth and societal progress [1,2]. In 2020, China’s crude steel production reached 1.065 billion tons, accounting for 56.7% of the global total [3]. Moreover, China holds a significant share in the global production of non-ferrous metal alloys, including iron, copper, and nickel, contributing approximately half of the global output [4,5]. However, this large-scale production generates a substantial amount of metallurgical solid waste, which is complex in composition and presents significant environmental and health risks [6,7]. In the absence of comprehensive pre-assessment and appropriate treatment, such waste not only results in resource loss but also poses serious threats to the ecosystem and public health [8].

Strengthening systematic research on metallurgical solid waste, including the identification of its composition, pollution characteristics, and potential hazards, has become essential for the scientific management and resource utilization of such waste [9,10]. This will enhance waste management practices while also providing a critical foundation for the green transformation and sustainable development of the metallurgy industry. Recent research has focused on the occurrence forms, leaching characteristics, and health risk assessments of heavy metals in metallurgical solid waste. For instance, Pang et al. [11]., employed both experimental and modeling approaches to analyze the distribution and environmental risks of heavy metals in electrolytic manganese residue (EMR), lead–zinc slag (LZS) and electric-furnace ferronickel slag (EFS). They found that manganese in EMR is readily leached under neutral conditions, whereas heavy metals in LZS and EFS are leached under acidic conditions, with leaching subsequently controlled by complexation and precipitation in neutral or alkaline environments. Anna and her team [12] observed that the leaching of heavy metals in metallurgical solid waste is significantly affected by pH, with most metals exhibiting lower concentrations at higher pH values. However, lead leaching increases under alkaline conditions, and copper leaching notably rises at a pH of 10.5. Li et al. [13]., emphasized that although certain metals in metallurgical solid waste may have high total concentrations, their leachability and environmental risks depend primarily on their speciation and mobility. Therefore, sequential extraction tests are necessary to assess the release potential and environmental impact of pollutants, ensuring safe reuse or proper disposal.

Jarosite slag, electric arc furnace ash, chromium-containing sludge, and acid-base sludge are typical solid wastes in the metallurgy industry [14]. These wastes attract significant attention due to their complex origins, diverse compositions, and significant environmental risks. Jarosite slag primarily result from the use of the iron salt process in hydrometallurgical extraction of zinc, copper, and nickel, with the highest production occurring during zinc smelting [15]. Current disposal methods for jarosite slag include landfilling, hazardous waste treatment, rotary kiln, and plasma furnace processes [16]. However, due to technological and economic constraints, large quantities of jarosite slag continue to be temporarily stored, posing considerable environmental pollution risks. Electric arc furnace ash, a byproduct of steelmaking in electric arc furnaces, contains up to 40–50% iron and includes harmful heavy metals such as lead, chromium, and arsenic, presenting significant environmental hazards [17]. Chromium-containing sludge, primarily produced during steel plate coating processes, contains chromium concentrations ranging from 3% to 12% [18]. During storage, trivalent chromium may oxidize to the more toxic hexavalent chromium, threatening water and soil safety [19]. Acid-base sludge, formed by mixing acid and alkaline residues from cold-rolling mills, is complex in composition, containing iron oxide, residual acids, and exhibiting both oiliness and alkaline corrosivity, thus posing significant environmental risks [20]. Ioana Monica Sur et al. [21]. conducted an ecological risk assessment of soils in the Baia Mare region, Romania. Their results revealed elevated levels of heavy metals in the topsoil (Cd:3.5–14.4 mg/kg; Cu:9.4–361.5 mg/kg; Pb:29.7–1973 mg/kg), with concentrations exceeding the limits set by Romanian legislation. Gianina Elena Damian et al. [22]. examined the effect of pH in humic acid washing solutions on removing lead and copper from a polymetallic contaminated soil. Using an in situ soil washing technique on soil from near the “Lăcădețu” mine in Zlatna, Romania, they assessed solutions at pH 3.0, 7.0, and 9.6 (the natural pH of the solution). The results demonstrated optimal removal efficiency under alkaline conditions, with 60.3% of copper and 48.08% of lead removed. The complex composition and high pollution risks of metallurgical solid waste necessitate urgent scientific analysis and assessment of its composition and potential hazards.

This study focuses on four representative types of metallurgical solid waste—jarosite slag (SW1), electric arc furnace dust (SW2), chromium-containing sludge (SW3) and acid-base sludge (SW4)—with the primary objectives of determining the speciation, leaching behavior, and potential health risks of heavy metals present in these wastes. By systematically evaluating their environmental release potential and toxic effects, this research aims to provide a scientific basis for the precise management and environmentally sound treatment of metallurgical solid wastes. An integrated analytical approach was employed. (1) X-ray fluorescence (XRF), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). These techniques were used to comprehensively characterize the chemical composition, crystalline phases, and microstructural properties of the wastes, establishing a physicochemical foundation for interpreting their environmental behavior. (2) the BCR sequential extraction procedure was applied to assess the mobility and release characteristics of heavy metals. (3) The Risk Assessment Code (RAC) and the Overall Pollution Toxicity Index (OPTI) were further utilized to quantitatively evaluate potential threats to ecosystems and human health. This study is expected to deliver critical data for assessing the environmental impact and health risks associated with metallurgical solid wastes. The findings will support the optimization of waste disposal strategies and contribute to promoting green and sustainable development within the metallurgical industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

Jarosite slag (SW1) is produced during the removal of iron from zinc, copper, nickel, and other non-ferrous metals in the wet smelting process using the iron alum method at the Chizhou Jiuhua smelter. Electric arc furnace ash (SW2), chromium-containing sludge (SW3), and acid-base sludge (SW4) are all byproducts of the metallurgical processes in the iron and steel industry, sourced from the Maanshan Masteel Group. Immediately after collection, the samples were placed in sealed polyethylene bags and refrigerated at 4 °C. For sample representativeness, a composite sampling approach was employed: within 24 h, 10 subsamples (approximately 1 kg each) were randomly collected at different time points from the discharge stream of each waste. After all subsamples were thoroughly mixed, they were reduced to approximately 2 kg using the quartering method for subsequent experimental analysis. Prior to analysis, all samples were dried to a constant weight in an oven at 60 °C, ground, and sieved through a 100-mesh nylon sieve to ensure sample homogeneity.

2.2. Characterization Methods

The particle size distribution of the samples was measured using a Mastersizer 2000 (Malvern Instruments Ltd. Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). The chemical composition of the samples was analyzed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF, EAGLE III model, EDAX Corporation, Warrendale, PA, USA). SEM (Hitachi SU8020, Tokyo, Japan) images were acquired on a Sirion 200 (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) operated at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a working distance of ≈10 mm. Secondary-electron (SE) and backscattered-electron (BSE) detectors were used as appropriate. EDS spectra were collected with an Oxford INCA system (live time 60 s) and quantified using ZAF correction. Representative micrographs are taken within the magnification range of ×500 to ×10,000. XRD (DX-2700,Dandong Haoyuan Instrument Co., Ltd., Dandong, China) analysis was performed using a PANalytical BV X’Pert Pro diffractometer (Cu Kα, λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV and 40 mA, scanned over 10–80° 2θ with a rate of 5°/min. Phase identification was conducted using HighScore Plus 4.9 and the ICDD PDF-4 database. XPS data were acquired with an ESCALAB 250Xi (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) using Al Kα radiation and processed with CasaXPS 2.3.25 after Shirley background subtraction. XRF data were analyzed using EDAX EAGLE III equipped with GENESIS software (GENESIS V7.0). ICP-OES (Agilent 5110, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and ICP-MS (PerkinElmer Nexion 1000, Waltham, MA, USA) were operated under standard plasma conditions, with quantification based on certified reference materials (GBW07405, GBW07406, Guangzhou, China). Thermal behavior was investigated using a STA 449 F3 Netzsch Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA, Selb, Germany) with a heating rate of 15 °C/min in air or nitrogen (N2). The total elemental composition of the acid-dissolved samples was determined using a Nexion 1000 Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS, PerkinElmer, MA, USA), as well as an Agilent 5110 Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES, Agilent, CA, USA) and an AFS-933 Atomic Fluorescence Spectrometer (Jitian Instrument Co., Ltd. Beijing, China). The recovery rates of all elements ranged from 90% to 110%, with relative standard deviations (RSDs) less than 5%. Finally, the treated sample mixtures were analyzed using the sulfuric-nitric acid digestion method to assess metal leachability, followed by leaching tests.

2.3. Experimental Methods

The moisture content was determined by drying the samples at 105 °C for over 12 h and recording the mass before and after drying. The leaching potential of heavy metals in solid waste was evaluated using the HJ/T 300-2007 [23] method, as proposed by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China [24]. The four solid waste sample (SW1, SW2, SW3, SW4) is prepared to pass through a 5 mm sieve, and its moisture content is determined. A defined mass of the sample is placed in an extraction vessel and mixed with an extraction agent, a dilute acid solution of sulfuric and nitric acids with an initial pH of 3.20, at a liquid-to-solid ratio of 10:1. The sealed vessel is agitated for 18 h at 30 rpm using a rotary oscillator at room temperature. Following agitation, the mixture is pressure-filtered, and the resulting leachate is collected, preserved as necessary, and analyzed for target contaminant concentrations to assess leaching toxicity. The chemical speciation of heavy metals was analyzed using the standardized four-step BCR sequential extraction procedure [25]. The fractions were defined as follows: F1 (acid-soluble/exchangeable), extracted using 0.11 mol/L CH3COOH for 16 h; F2 (reducible), extracted with 0.5 mol/L NH2OH·HCl for 16 h; F3 (oxidizable), treated with 8.8 mol/L H2O2 at 85 °C followed by 1 mol/L NH4OAc for 16 h; and F4 (residual), determined after complete digestion using HNO3–HF–HClO4. Each extraction step was followed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 min and filtration through a 0.45 μm membrane prior to ICP-OES analysis. Chloride ion concentration was determined using a chloride ion-selective electrode. Standard solutions of varying concentrations were prepared, and their current values were measured to generate a standard curve.

2.4. Environmental Risk Assessment Method

To quantitatively assess the environmental risks posed by heavy metals in four types of metallurgical solid waste, this study employed two computational models: the Risk Assessment Code (RAC) and the Overall Pollution and Toxicity Index (OPTI). These methodologies enable quantitative analysis of heavy metals’ bioavailability and comprehensive toxicity, based on their chemical forms and leaching characteristics, thereby providing a scientific basis for risk classification. The RAC index enables the quantification of environmental risk by calculating the ratio between the bioavailability score of heavy metals and their total concentration. According to previous studies [26], the bioavailability score is defined as the F1 fraction obtained from the BCR sequential extraction procedure. The equations are as follows:

where F1: weak acid extractable state; F2: residual state; F3: reducible state; F4: oxidizable state.

To assess the overall environmental risk of multiple heavy metals in four samples under specific leaching conditions, the Overall Pollution Toxicity Index (OPTI) was also employed. This index considers the types of heavy metals, their toxicity, and stability, as well as their impact on environmental risk.

where M: the number of relevant heavy metals; TK: the toxicity response factor of the heavy metals; and K: the corresponding heavy metal; (where is the total content of heavy metals, mg/kg; denotes the background concentration of heavy metals in Chinese surface soils, mg/kg); and is the ratio of leachable content to total heavy metal concentration [27].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Component Analysis

As illustrated in Figure S1, the iron oxide (Fe2O3) content in SW1 reached 51.9%, followed by sulfur trioxide (SO3), which accounted for approximately 31.7%. Additionally, trace amounts of silicon dioxide (SiO2, 7.5%), sodium oxide (Na2O, 4.4%), and zinc oxide (ZnO, 2.2%) were also present. In comparison, the Fe2O3 content in SW2 is slightly lower than in SW1, at approximately 51.4%. However, SW2 contained a significant proportion of ZnO, which represented 41.1% of the total mass. The calcium oxide (CaO) content in SW3 reached 23.6%, followed by chromium trioxide (Cr2O3), Fe2O3, and magnesium oxide (MgO), which comprised 19.8%, 18.2%, and 13.9%, respectively. Figure S1 demonstrates that SW4 was predominantly composed of Fe2O3 (45.5%) and CaO (30.3%), with smaller quantities of MgO (10.0%), SiO2 (5.0%), and aluminum oxide (Al2O3 4.3%).

The results indicate that SW1, SW2, and SW4 contain high levels of Fe. However, due to technical and economic constraints, iron slag is temporarily disposed of by stockpiling [28], which presents high presents a significant challenge for effective solid waste management. Furthermore, the presence of chromium in SW3 and the potential formation of toxic Cr6+ through the oxidation of Cr3+ pose a substantial risk to water bodies and soil quality [19].

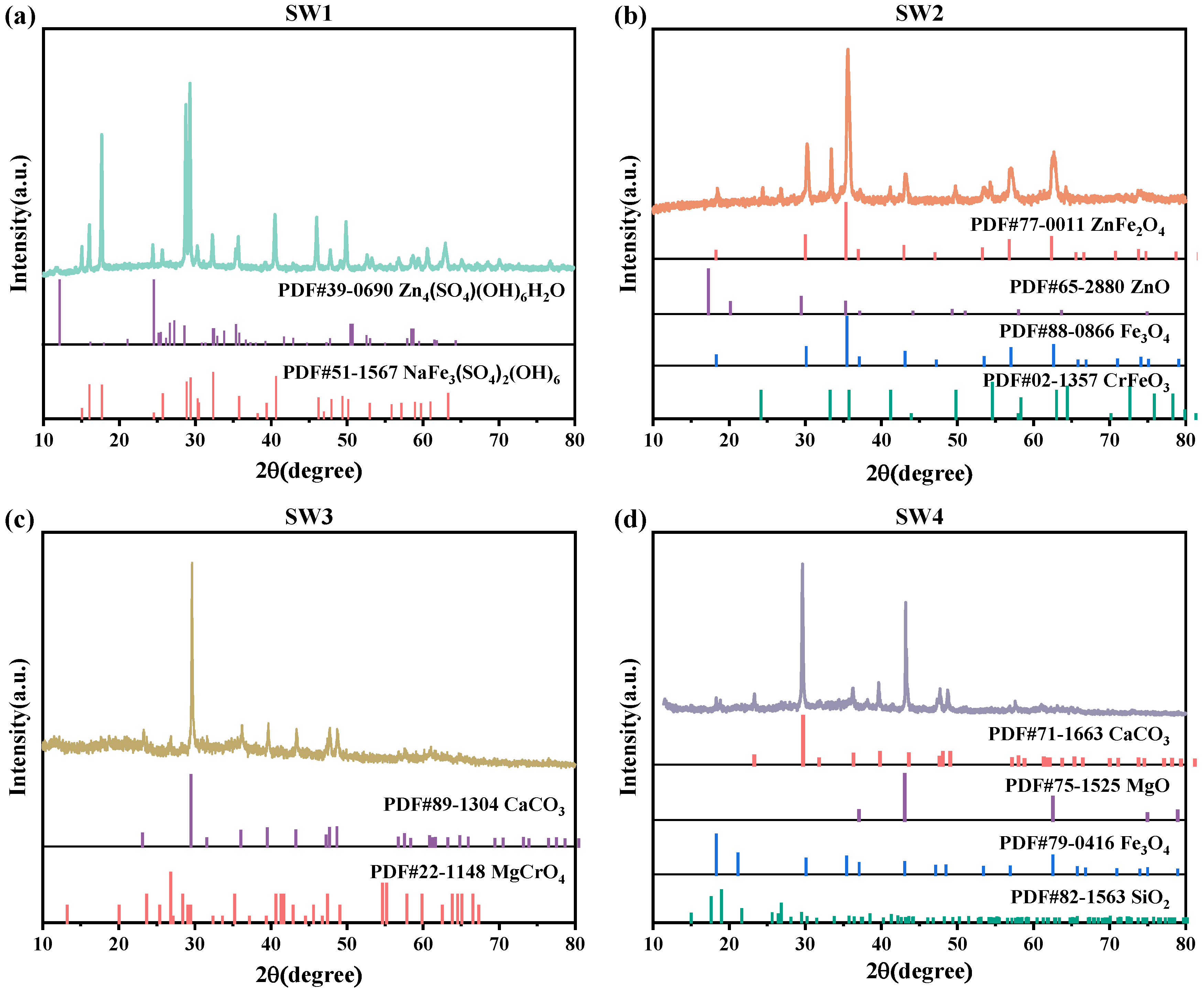

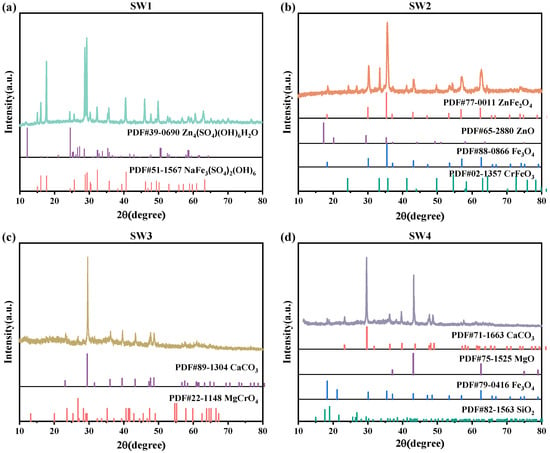

3.2. Phase Composition Analysis

The XRD spectra were baseline-corrected and smoothed using HighScore Plus 4.9, and the ICDD PDF-4 database. The characteristic diffraction peaks (2θ, °) of the dominant crystalline phases are summarized as follows: Zn4SO4(OH)6H2O (18.7°, 32.4°, 36.8°), NaFe3(SO4)2(OH)6 (15.1°, 30.3°, 37.6°) in SW1; Fe3O4 (30.1°, 35.5°, 57.0°), ZnFe2O4 (33.0°, 36.1°, 62.5°), and ZnO (31.8°, 34.4°, 47.6°) in SW2; CaCO3 (29.4°, 36.0°, 43.1°) and MgCrO4 (21.1°, 35.3°, 42.8°) in SW3; and Fe3O4 (30.1°, 35.5°, 57.0°), MgO (42.9°, 62.3°), and SiO2 (26.6°, 50.1°) in SW4. The XRD pattern of SW1 revealed that the slag was primarily composed of Zn4SO4(OH)6H2O and NaFe3(SO4)2(OH)6 phases (Figure 1a). Among these, Zn4SO4(OH)6H2O is a loosely bound hydroxy zinc sulfate hydrate that forms on the surface of Zn. As shown in Figure 1b, the physical phase of SW2 was predominantly characterized by Fe3O4, ZnO, and ZnFe2O4. Figure 1c shows that SW3 contained calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and magnesium chromate (MgCrO4). In contrast, the XRD pattern of SW4 (Figure 1d) identified the presence of Fe3O4, MgO, and SiO2 phases.

Figure 1.

(a)The XRD pattern of jarosite slag (SW1), (b) The XRD pattern of electric arc furnace dust (SW2), (c) The XRD pattern of chromium-containing sludge (SW3) and (d) The XRD pattern of acid-base sludge (SW4).

The high metal content in both SW1, SW2 and SW4 complicates their disposal, as improper handling could lead to environmental contamination. Therefore, resource recovery emerges as an effective strategy, not only reducing environmental risks but also maximizing economic benefits by extracting valuable metals [17,18]. Additionally, the presence of toxic Cr6+ in the MgCrO4 phase of SW3 highlights the need for stringent disposal measures [19]. Given the potential threat of chromium to aquatic ecosystems, careful consideration must be given to neutralizing or safely containing this compound to minimize its ecological impact.

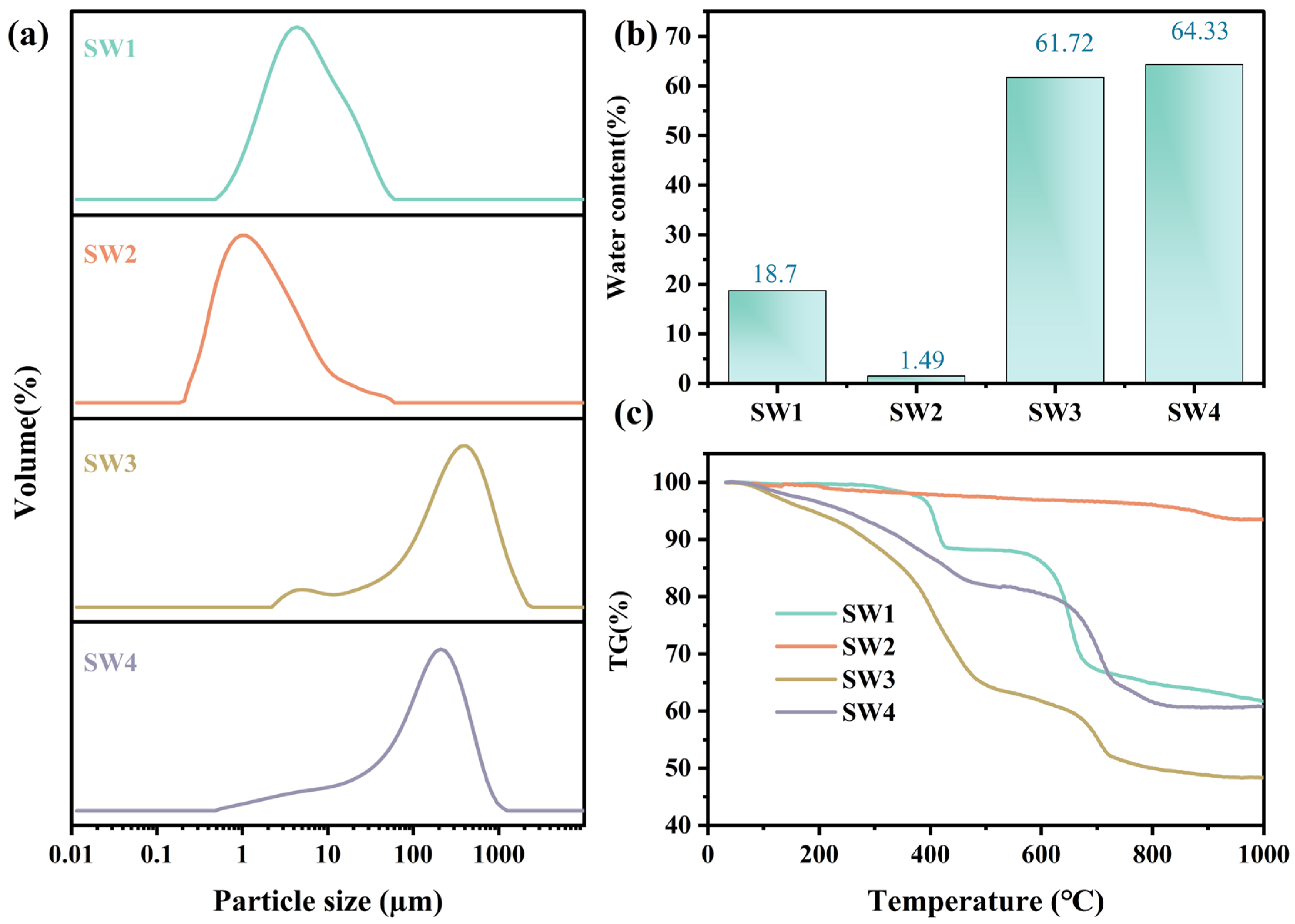

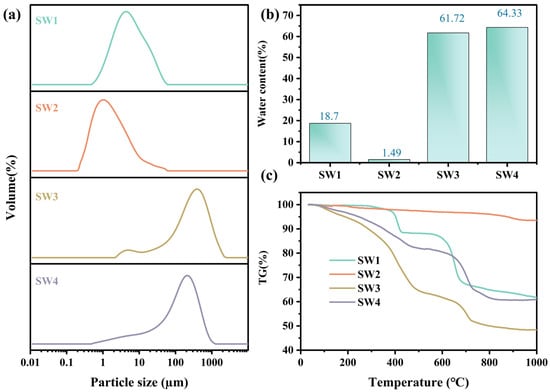

3.3. Particle Size Distribution

The particle size distribution for the four solid wastes (SW1, SW2, SW3, and SW4) are shown in Figure 2a and Table S1. The particle size distribution was analyzed using a Mastersizer 2000 (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, WorcestershireUK) equipped with a He–Ne laser (λ = 633 nm). The D10, D50, and D90 values were obtained using Mastersizer 2000 software. Notable variations in particle size and distribution patterns were observed. SW1 and SW2 exhibited finer particles, with D50 values of 4.76 µm and 1.34 µm, respectively, classifying them as fine particulate matter [29]. In contrast, SW3 and SW4 displayed coarser particles, with D50 values of 268.83 µm and 133.94 µm, respectively. At the same time, SW2 exhibited the broadest distribution (4.40), indicating a wider range of particle sizes, while SW3 and SW4 showed narrower distributions (Table S1).

Figure 2.

The particle size distribution (a), moisture content (b), and thermogravimetric of four solid wastes (c).

Fine particulates (SW1 and SW2) have a higher tendency to adsorb heavy metals such as lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and copper (Cu), thereby enhancing the mobility and bioavailability of these metals in the environment [30]. In contrast, SW3 and SW4 are primarily composed of coarse particles, in which heavy metals are typically present in crystalline or mineral-bound forms with lower bioavailability [31]. However, upon deposition, these metals may still be released through weathering and acidification processes. Consequently, fine particulates such as SW1 and SW2 require greater attention in health risk assessments. For SW3 and SW4, the focus should shift to the long-term release of heavy metals in soil and water and their cumulative environmental impact.

3.4. Moisture Content and Thermogravimetric

As shown in Figure 2b, SW1 exhibited moderate moisture content (18.7%), which mitigates transportation challenges but increases the risk of heavy metal leaching during storage. SW2, with the lowest moisture content (1.49%), minimizes handling complexity. However, its fine particulate nature heightens the risk of airborne dispersion, necessitating solidification or stabilization [32,33]. In contrast, SW3 (61.72%) and SW4 (64.33%) exhibited high moisture contents, which not only elevated treatment costs but also exacerbated leachate risks. These characteristics underscore the need for advanced dehydration, stabilization, and resource recovery technologies to minimize environmental impacts and support sustainable waste management practices [34,35].

The thermogravimetric curves (Figure 2c) showed three distinct stages of mass loss. For SW1, 3.8% weight loss occurred below 150 °C due to moisture evaporation, followed by 7.2% between 400~600 °C attributed to decomposition of Zn4SO4(OH)6·H2O. SW2 exhibited negligible mass change (<1%) up to 800 °C, indicating high thermal stability. SW3 lost 12.5% mass below 200 °C (bound water) and 18.3% between 200~500 °C (decomposition of carbonates and hydroxides). SW4 exhibited a total loss of 16.8%, mainly between 100~600 °C due to dehydration and CaCO3 decomposition.

The weight loss of SW1 primarily occurred between 400 °C and 600 °C, with a substantial increase, indicating that its heavy metals may be present in relatively stable mineral forms. In contrast, SW2 exhibited negligible weight loss and demonstrated the highest thermal stability, which effectively immobilizes heavy metals and minimizes the risks associated with thermal treatment [36]. SW3, however, showed significant weight loss within the range of 100 °C to 500 °C, suggesting the presence of considerable amounts of bound water and thermally unstable compounds [37]. Similarly, the weight loss of SW4 predominantly occurred between 100 °C and 600 °C, although to a lesser extent than SW3. Nevertheless, its calcium-based compounds and adsorbed heavy metals may still be released at high temperatures, necessitating attention to their potential dissolution. Therefore, SW1 and SW2 exhibit superior thermal stability and a lower risk of heavy metal release, whereas SW3 and SW4 demonstrate reduced thermal stability, with SW3 requiring particular attention due to its pronounced risk of heavy metal release under high-temperature conditions. These findings provide critical insights and recommendations for the high-temperature treatment of metallurgical solid wastes.

In conclusion, the moisture content of metallurgical solid waste significantly affects the speciation and leaching characteristics of heavy metals. Fine particulates with low moisture content pose health risks through airborne dispersion, while coarse particulates with high moisture content are more likely to cause waterborne contamination. Therefore, in health risk assessments and solid waste management, strict pollution control measures should be implemented based on the moisture content and particle characteristics to effectively mitigate the environmental and health hazards associated with heavy metals.

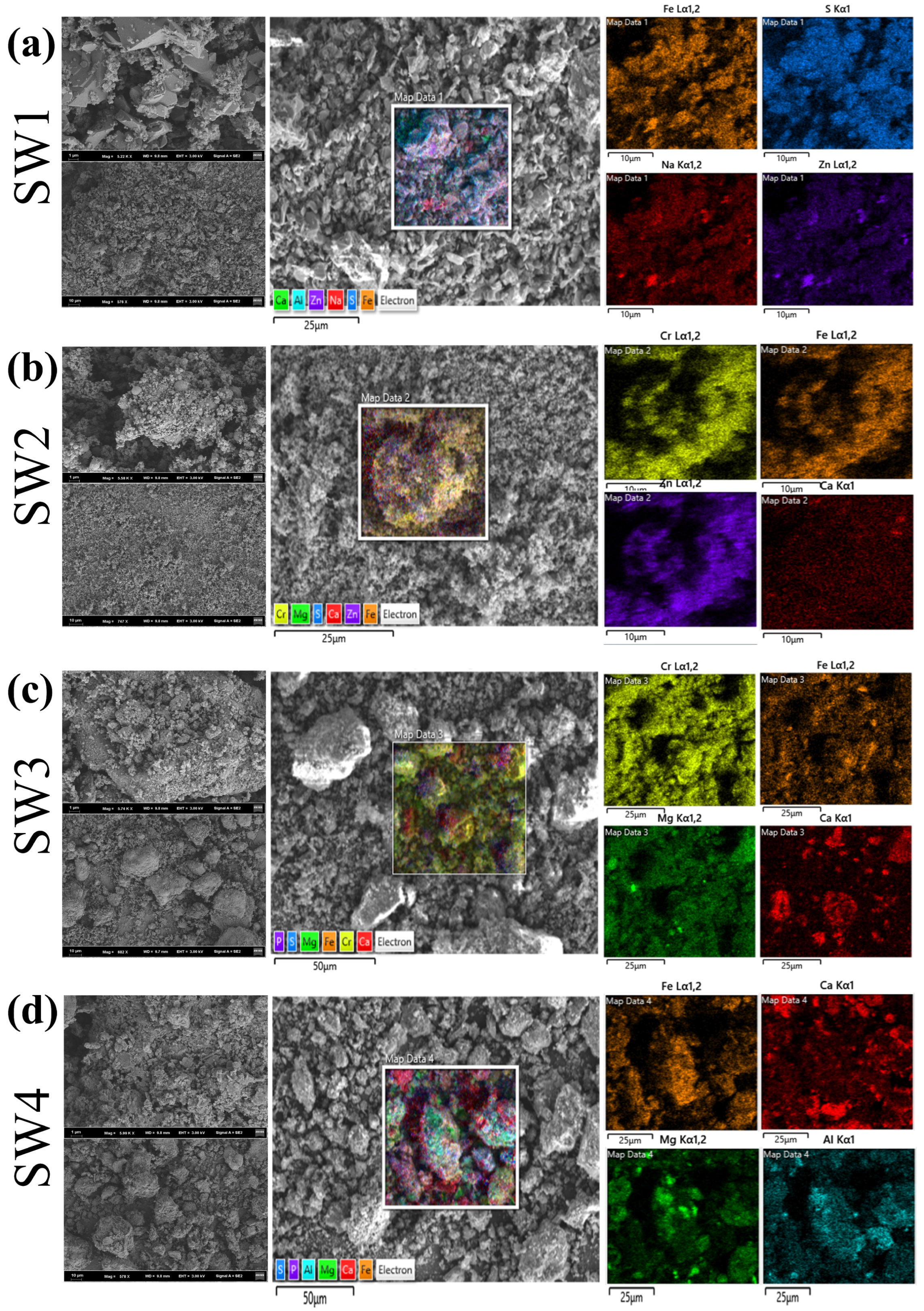

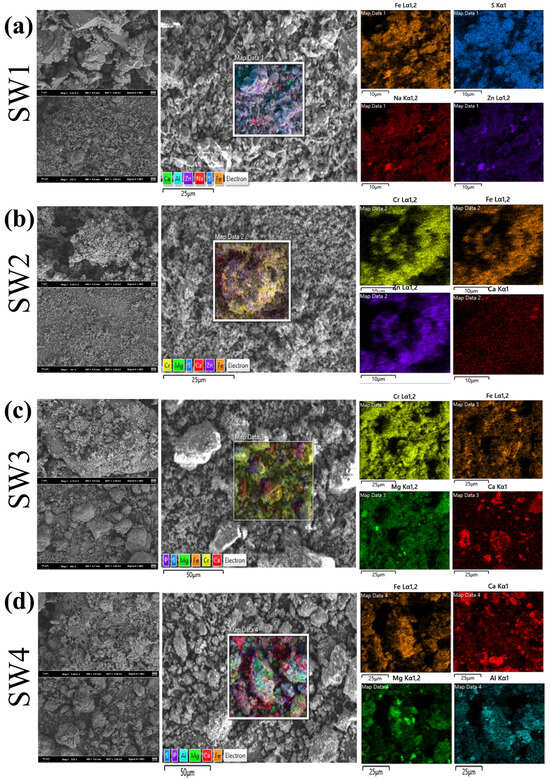

3.5. Morphology Analysis

As shown in Figure 3 and Figure S2, all SEM images were obtained at 15 kV with scale bars of 2 μm (SW1 and SW2) and 10 μm (SW3 and SW4). Particle size distributions measured by laser diffraction (Mastersizer 2000) are reported in Section 3.3; the D50 values were SW1 = 4.76 μm, SW2 = 1.34 μm, SW3 = 268.83 μm and SW4 = 133.94 μm. SEM observations qualitatively concur with these results: SW1 and SW2 show fine, flaky/porous particles while SW3 and SW4 exhibit coarser aggregated particles. SW1 primarily exhibited sheet-like and porous structures with rough surfaces, and EDS results indicated that Fe and S were the dominant elements (Tables S2 and S3), which consistent with the above XRD results showing that the main components are hydrated iron sulfate and hydrated zinc sulfate. This structure provides a high specific surface area, which may facilitate the enrichment of heavy metals within micropores [38]. However, under acidic or oxidizing conditions, heavy metals are prone to leaching [39]. SW2 displayed a particle-like and glassy structure, with Zn and Fe as the main elements (Tables S2 and S3). The glassy characteristics contribute to the stabilization of heavy metals, but cracks may serve as pathways for Zn release, particularly under acidic conditions, where Zn mobility poses a significant risk. SW3 was predominantly composed of flocculent aggregates that gradually formed clustered structures, with Cr and Fe as the main elements (Tables S2 and S3). The loose structure of this sample renders its heavy metal species highly soluble. Notably, the significant Cr content poses a high environmental and health risk due to the potential release of toxic Cr6+ under acidic or oxidizing conditions. SW4 exhibited a dense blocky structure primarily composed of Fe and Ca (Tables S2 and S3). XRD results shown that its main component is calcium carbonate. Alkaline conditions may enhance the passivation of heavy metals [40,41], but cracks and localized loose areas could lead to the release of heavy metals, especially under acidic conditions, where potential risks remain.

Figure 3.

(a)The SEM of jarosite slag (SW1), (b) The SEM of electric arc furnace dust (SW2), (c) The SEM of chromium-containing sludge (SW3) and (d) The SEM of acid-base sludge (SW4).

In summary, SW1 and SW3, due to their porous or loose structures, may exhibit higher risks of heavy metal release under specific conditions. Although SW2 contains relatively stable glassy materials, the effects of cracks should be closely monitored. The dense structure of SW4 reduces heavy metal release to some extent, but its long-term stability warrants further evaluation. These findings provide a scientific basis for the development of technologies for the harmless treatment of metallurgical solid wastes.

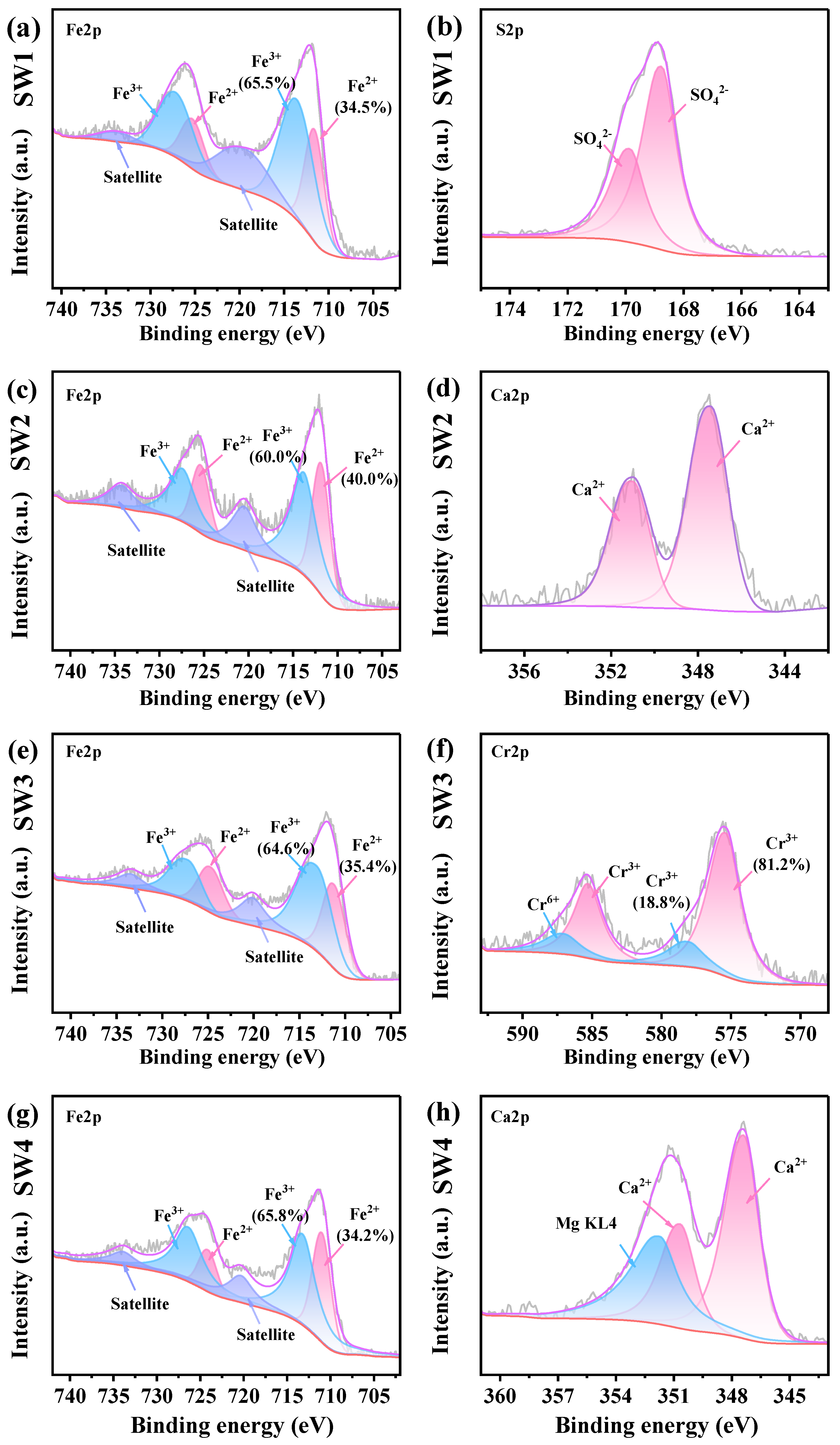

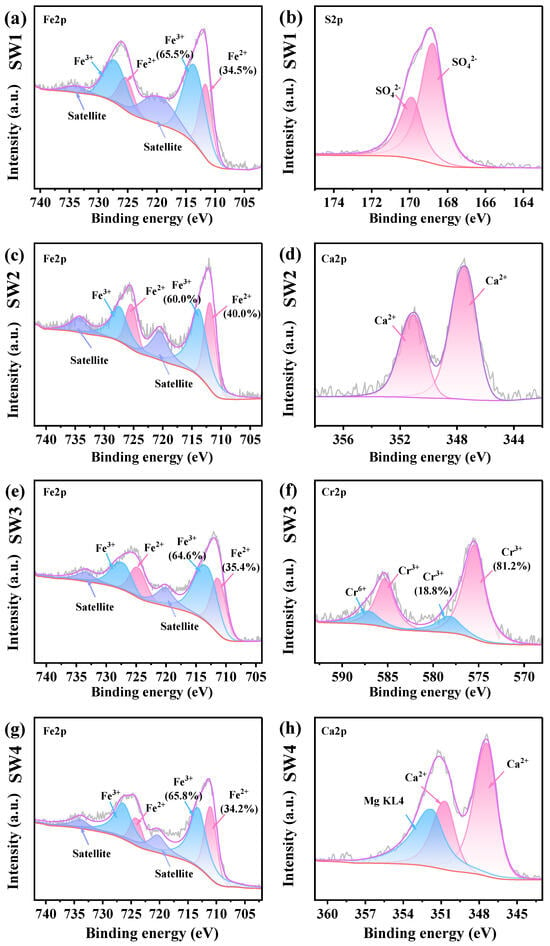

3.6. Element Valence Analysis

In the Fe2p spectrum, six peaks were identified: 711.6 and 725.3 eV for Fe2+, 713.6 and 727.2 eV for Fe3+ and 720.1 and 733.8 eV for satellite peaks, respectively. The S2p spectra showed peaks at 168.7 eV and 169.8 eV, corresponding to SO42−2p3/2, and SO42− 2p1/2, respectively. For Zn, peaks at 1022.3 eV, 1039.7 eV, and 1045.3 eV were assigned to Zn2+ 2p3/2, loss feature, and Zn2+ 2p1/2, respectively. In the Mg1s spectrum, the peak at 1303.6 eV corresponded to Mg2+. Additionally, in presence of Mg, Mg KL4 region overlaps with the Ca2p region, resulting in the Ca2p spectrum being split into three components: Ca2+ 2p3/2 (347.4 eV), Ca2+ 2p1/2 (350.1 eV), and Mg KL4 (351.7 eV). The Cr2p spectra consisted of four peaks, attributed to Cr3+ 2p3/2 (575.3 eV), Cr3+ 2p1/2 (585.3 eV), Cr6+ 2p3/2 (578.1 eV), and Cr6+ 2p1/2 (587.1 eV). The XPS peak assignments were confirmed based on the NIST database. For example, Fe2+ (711.6 eV) and Fe3+ (713.6 eV) were identified in Fe 2p spectra, Zn2+ (1022.3 eV) in Zn 2p, and Cr6+ (578.1 eV) and Cr3+ (575.3 eV) in Cr 2p, consistent with corresponding XRD-identified phases such as Fe3O4, ZnFe2O4, and MgCrO4.

As illustrated in Figure 4b, the S2P spectra revealed the presence of SO42− in the SW1, which is consistent with the XRD and XRF results. The Zn2p spectra indicated Zn to be the form of Zn2+ in the SW1 and SW2 (Figure S3b,d). Figure 4c,d demonstrates that Mg is identified as Mg2+ in SW3 and SW4 (Figure S3f,h). This is consistent with the XRD results as well. Additionally, the content of Fe3+ in the four solid wastes is higher than that of Fe2+. In the management of solid waste, proper management and disposal methods must be implemented to prevent the indiscriminate dumping of these solid wastes [9]. Moreover, Ca2+ was detected in both SW2 and SW4 (Figure 4d,h), and based on XRD and XRF analyses, the source of Ca2+ was identified as CaCO3. Notably, the Cr2p spectra indicated that 18.8% of the Cr was in the Cr6+ state (Figure 4h). According to the XRF analysis, the high toxicity of Cr6+ underscores the need for preventive measures to mitigate potential health risks associated with SW3 [42].

Figure 4.

(a,b) The XPS spectrum ofjarosite slag (SW1), (c,d) The XPS spectrum of electric arc furnace dust (SW2), (e,f) The XPS spectrum of chromium-containing sludge (SW3) and (g,h) The XPS spectrum of acid-base sludge (SW4).

3.7. Mass Fraction Analysis of Heavy Metals and Cl, S in Solid Waste

Table S4 demonstrates the mass fractions of heavy metals and Cl and S in solid waste. The SW1 contained a high concentration of S (111,000 mg·kg−1), followed by Pb (2977 mg·kg−1), As (2136 mg·kg−1), and Cu (1808 mg·kg−1). This is because SW1 is primarily composed of sulfates, which is consistent with the XRD results. In contrast, the Cl content in SW2 reached 20,448.4 mg·kg−1, which can be reduced through acid-base washing and high-temperature calcination. The results indicated that both SW1 and SW2 had high levels of Pb, As, Cu, and Cd. Based on health risk assessment and solid waste disposal technologies, it is recommended to recycle heavy metals or stabilize them to reduce their bioavailability and decrease their mobility in the environment [43]. Furthermore, both Cl and S concentrations were relatively high in SW3 and SW4. The high content S may lead to the formation of acidic leachate when the S comes into contact with moisture, which can result in soil and water acidification, thereby negatively affecting plant growth and aquatic organisms [44]. Cl may seep into groundwater, contaminating water sources. Under sunlight and high-temperature conditions, it can form toxic chlorinated organic compounds, posing risks to ecosystems and human health [45]. In comparison to SW1 and SW2, the heavy metal concentrations in SW3 and SW4 are relatively lower. However, the potential impact on water environments and soils during solid waste disposal processes should still not be overlooked.

3.8. Heavy Metal Toxicity Leaching Test

The leaching behavior of four samples was investigated through acid leaching experiments. The results are shown in Table 1, except for Zn in SW1, all other heavy metal elements were below the thresholds specified in GB 5085.3-2007 [46] for hazardous waste identification. Therefore, the thresholds outlined in the Chinese Surface Water Quality Standard (GB 3838-2002) [47] (Table S6) and the Groundwater Quality Standard (GB/T14848-2017) [48] (Table S7) were used as the baseline to assess the concentration of hazardous substances in solid waste leachate [49]. The leaching amounts of Cu (11.81 mg·L−1) and Cd (1.66 mg·L−1) in SW1 and Cd (0.159 mg·L−1) in SW2 exceeded the surface water and groundwater quality standards. All other metals were below these standards. Additionally, the heavy metal concentrations in SW3 and SW4 were also lower than the surface water and groundwater quality standards, indicating that SW3 and SW4 pose a lower safety risk, while SW1 and SW2 present a higher safety risk. The elevated leaching of Zn in SW1 may be associated with the chemical form of Zn, which is consistent with the results of XRD analysis showing the presence and form of Zn in SW1. Zelin Xu et al. [50]. reported that the extractant specified in HJ/T 299-2007 [51] for simulating acid rain lowered the surface pH of solid matrices, which enhanced the release of metals/metalloids. Alicja Kicin’ska et al. [52]. demonstrated that Cd and Zn posed a greater leaching hazard than other metallic elements when evaluated using alternative leaching methods. This suggests that the greater leachability of Cd and Zn increases their potential environmental risk.

Table 1.

Leaching toxicity of four solid wastes (ρ mg/L).

3.9. Occurrence State Analysis of Metal Elements

The chemical form and distribution of heavy metals in four samples were investigated (Figure S4 and Table S5). During the extraction process, the residual state is identified as the most stable, with minimal environmental risk. However, the weak acid extractable state is more easily mobilized, suggesting that these metals may be released upon changes in environmental pH [53]. Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Ce in SW1 were predominantly in the residual state (>65%), indicating a low environmental risk. However, the weak acid extractable fraction of SW1 (ranging from 4% to 24%) should not be overlooked, as it might pose a potential risk of environmental contamination, warranting further attention and treatment. Unfortunately, SW2 exhibited the highest percentage of Cd in the weak acid extractable state (52%), significantly surpassing the other three samples, which indicated that the environmental risk of Cd in SW2 was the highest. However, Ni and Cu in SW2 were predominantly present in the residual state, resulting in a relatively low leaching risk. The weak acid extractable fraction of Cd in SW3 (45%) was only surpassed by SW2. Notably, the weak acid extractable fraction of Ni in SW4 (14%) was higher than that of the other metals in SW4. Meanwhile, the reducible and oxidizable states of heavy metals in SW3 and SW4, as well as those of Pb and Ce in SW2, were found to be high. However, metals in the reducible and oxidizable fractions possess potential for mobility and bioavailability. These metals may be released in response to changes in environmental conditions [54]. In summary, the environmental risks associated with the four samples are ranked as follows: SW2>SW3>SW1>SW4.

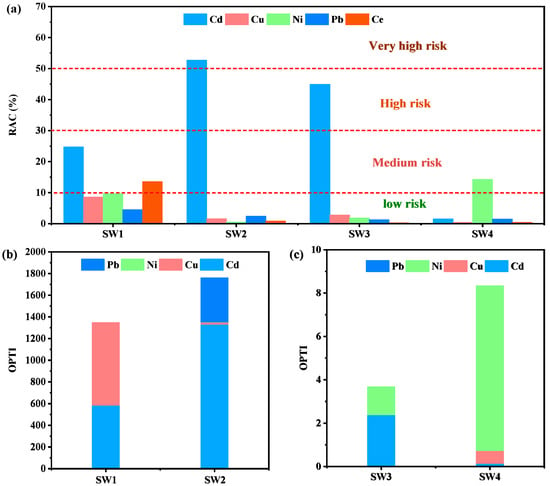

3.10. Environmental Risk Assessment

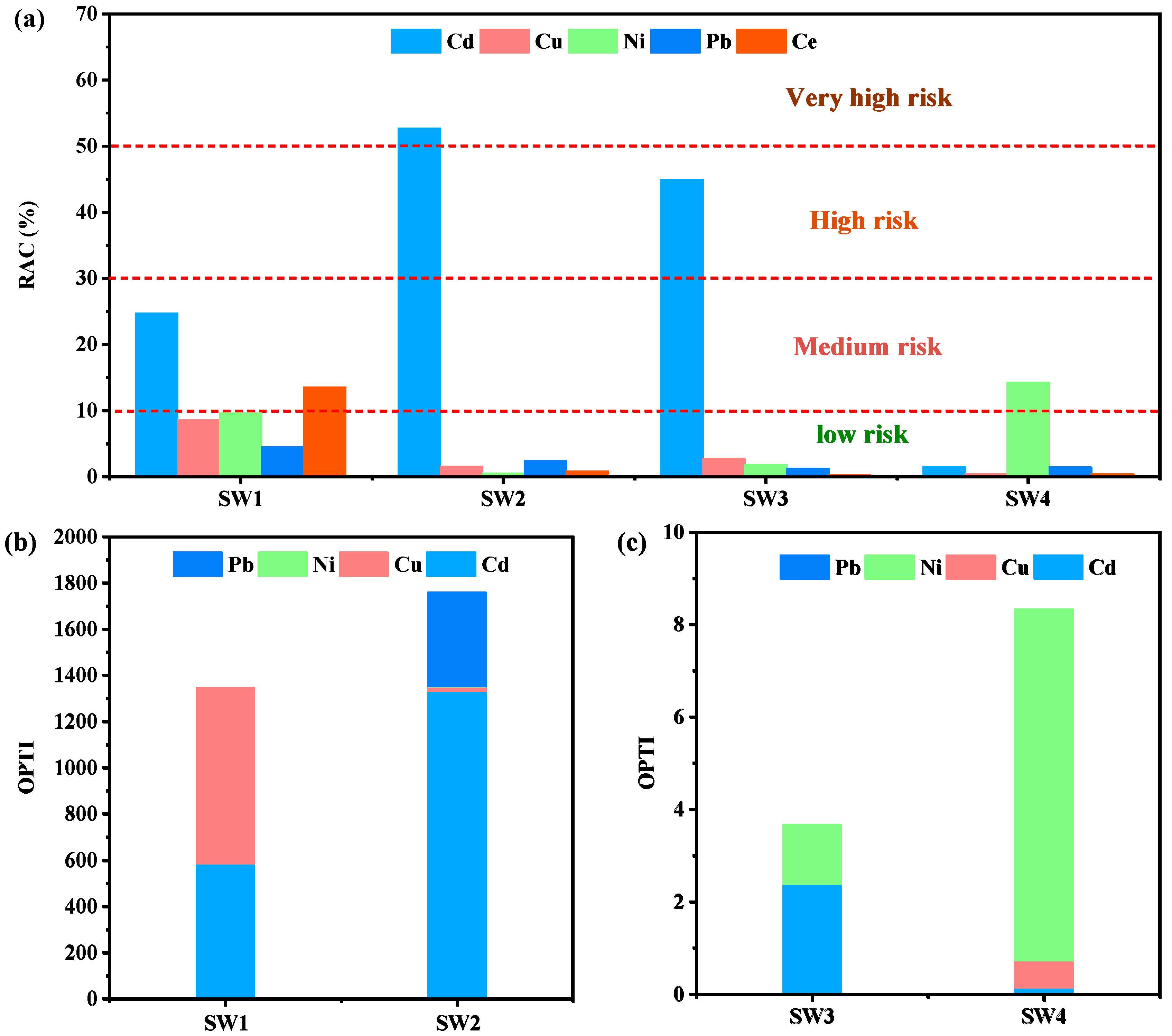

The environmental risk of heavy metals in the four samples can be assessed using the Risk Assessment Code (RAC). RAC classifies risks into five levels: values below 1% are considered safe for the environment, 1–10% indicates low risk, 11–30% represents moderate risk, 31–50% corresponds to high risk, and values exceeding 50% signify very high risk [55]. Based on the RAC calculation using the BCR method, Cd constitutes the primary environmental risk, reaching high-risk levels in SW2 and SW3, with RAC values ranging from 44.94% to 52.74%. Additionally, Ce in SW1 and Ni in SW4 exhibit moderate risk levels, while all other metals fall within the low-risk category (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

RAC of four solid wastes (a), OPTI of four solid wastes (b,c).

To evaluate the overall toxicity of heavy metals in the four samples, the Overall Pollution Toxicity Index (OPTI) was employed. Generally, SW3 and SW4 showed relatively low cumulative toxicity under acidic leaching conditions, whereas SW1 and SW2 exhibited higher toxicity (Figure 5b,c). Cd was the major contributor to the OPTI values in both SW1 and SW2, likely due to its cationic leaching behavior [56].

4. Conclusions

This study conducted a comprehensive investigation of four typical metallurgical solid wastes, yielding several significant findings:

Chemical composition analysis revealed that SW1, SW2, and SW4 contained high levels of Fe2O3 (45.5–51.9%), while SW3 showed significant amounts of CaO (23.6%) and Cr2O3 (19.8%). XRD and XPS analyses confirmed the presence of various metal-containing phases and different valence states of metals, particularly the concerning presence of Cr6+ (18.8%) in SW3. Physical characterization demonstrated distinct differences in particle size distribution and moisture content among the samples. SW1 and SW2 were characterized by fine particles (D50 < 5 μm) with relatively low moisture content, while SW3 and SW4 consisted of coarse particles (D50 > 100 μm) with high moisture content (>60%). These characteristics significantly influence their environmental behavior and treatment requirements.

The leaching toxicity tests revealed that SW1 and SW2 posed higher environmental risks, with several heavy metals exceeding standard limits. The BCR sequential extraction showed that Cd exhibited the highest mobility, particularly in SW2 and SW3, with weak acid extractable fractions of 52% and 45%, respectively. Environmental risk assessment using RAC and OPTI indicated that: Cd constituted the primary environmental risk, reaching high-risk levels in SW2 and SW3. The overall environmental risks ranked as: SW2>SW3>SW1>SW4. SW1 and SW2 demonstrated higher cumulative toxicity under acidic leaching conditions

These findings have important implications for the management and treatment of metallurgical solid wastes: Fine particulate wastes (SW1 and SW2) require careful handling and dust control measures due to their potential for airborne dispersion and higher heavy metal mobility. The high moisture content in SW3 and SW4 necessitates effective dewatering processes before further treatment or disposal. Special attention should be paid to Cd contamination, particularly in SW2 and SW3, where stabilization treatments may be necessary before disposal. The presence of Cr6+ in SW3 demands specific treatment strategies to prevent its release into the environment.

This research provides a scientific basis for optimizing waste management strategies and developing targeted treatment technologies for different types of metallurgical solid wastes, contributing to the sustainable development of the metallurgical industry.

5. Implications for Waste Management and Resource Recovery

The resource recovery potential of these wastes is explicitly discussed: Specifically, SW2, with its extremely high contents of ZnO (41.1%) and Fe2O3 (51.4%), is identified as a highly valuable secondary resource for zinc and iron recovery. Meanwhile, the challenge in its recycling is also noted, namely its relatively high chlorine content (20,448.4 mg/kg). Pretreatment processes such as washing or roasting may be required to remove chlorine prior to pyrometallurgical processing. For SW1 and SW4, their potential as iron recovery resources is also discussed, given their similarly high Fe2O3 contents (51.9% and 45.5%, respectively). Regarding SW3, the focus of its resource recovery is indicated to lie in the retrieval of chromium (Cr) and calcium (Ca), but the harmless treatment of highly toxic Cr(VI) must be prioritized.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jox15060211/s1, Table S1: Particle size of four solid wastes. Table S2: The SEM EDS results of four solid wastes. Table S3: The TEM EDS results of four solid wastes. Table S4: Mass fraction of heavy metals and Cl, S in four solid wastes (ω mg·kg−1). Table S5: The results of the BCR sequential extraction procedure (mg/kg). Table S6: The Chinese National Standard for Surface Water Quality (GB 3838-2002) regarding selected heavy metals. Table S7: the Chinese National Standard for Groundwater Quality (GB/T14848-2017) regarding specific heavy metals. Figure S1: The chemical composition of four solid wastes. Figure S2: The TEM of four solid wastes. Figure S3: The XPS spectrum of four solid wastes. Figure S4: The occurrence state of metal elements in four solid wastes. File S1: Original images of Figure 3 and Figure S2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and G.N.; methodology, G.N.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, S.L.; resources, G.N.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. writing—review and editing, G.N.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, G.N.; project administration, G.N.; funding acquisition, G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key R&D Plan of China (Grant No.2022YFC3703100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Shuqin Li was employed by the company Sinosteel Maanshan General Institute of Mining Research Co., Ltd., Maanshan 243071, China. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Wu, P.; Jiang, L.Y.; He, Z.; Song, Y. Treatment of metallurgical industry wastewater for organic contaminant removal in China: Status, challenges, and perspectives. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2017, 3, 1015–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiao, K.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Z. A review on low carbon emissions projects of steel industry in the World. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 306, 127259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Ho, J.; Cui, J.; Ren, F.; Cheng, X.; Lai, M. Improving the post-fire behaviour of steel slag coarse aggregate concrete by adding GGBFS. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Wen, Z. Analysis of China’s non-ferrous metals industry’s path to peak carbon: A whole life cycle industry chain based on copper. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, B. Energy and CO2 emission performance: A regional comparison of China’s non-ferrous metals industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 123168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, G.; Mikula, K.; Skrzypczak, D.; Moustakas, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Chojnacka, K. Potential environmental pollution from copper metallurgy and methods of management. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iluţiu-Varvara, D.-A. Researching the Hazardous Potential of Metallurgical Solid Wastes. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 25, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Zulkapli, N.S.; Kamyab, H.; Taib, S.M.; Din, M.F.B.M.; Majid, Z.A.; Chaiprapat, S.; Kenzo, I.; Ichikawa, Y.; Nasrullah, M. Current technologies for recovery of metals from industrial wastes: An overview. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 22, 101525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Liu, X.; Yu, I.K.; Wang, L.; Zhou, J.; Sun, X.; Rinklebe, J.; Shaheen, S.M.; Ok, Y.S.; Lin, Z. Potentially toxic elements in solid waste streams: Fate and management approaches. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 253, 680–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisz, S.; Kibort, K.; Mioduska, J.; Lieder, M.; Małachowska, A. Waste management in the mining industry of metals ores, coal, oil and natural gas—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; An, M.; Wang, Q. Occurrence and leaching behaviors of heavy-metal elements in metallurgical slags. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 330, 127268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, A.; Mizerna, K.; Bożym, M. An assessment of pH-dependent release and mobility of heavy metals from metallurgical slag. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, H.; Wang, J.; She, X.; Wang, G.; Zuo, H.; Xue, Q. Current status of the technology for utilizing difficult-to-treat dust and sludge produced from the steel industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 132909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, X.; Qu, G.; Ning, P. A critical review on extraction of valuable metals from solid waste. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 301, 122043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Ye, L.; Du, J. Research progress of vanadium extraction processes from vanadium slag: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 342, 127035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyrokykh, T.; Volkova, O.; Sridhar, S. The Recycling of Vanadium from Steelmaking Slags: A Review. Steel Res. Int. 2024, 95, 2300477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, K.; Fu, T.; Gao, J.; Hussain, S.; AlGarni, T.S. Pyrometallurgical recovery of zinc and valuable metals from electric arc furnace dust—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, H.-Y.; Shen, S.; Cheng, J.; Diao, J.; Xie, B. A novel process for comprehensive resource utilization of hazardous chromium sludge: Progressive recovery of Si, V, Fe and Cr. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 405, 124669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, L.; Mugnaioli, E.; Perchiazzi, N.; Duce, C.; Pelosi, C.; Zamponi, E.; Pollastri, S.; Campanella, B.; Onor, M.; Abdellatief, M.; et al. Hexavalent chromium release over time from a pyrolyzed Cr-bearing tannery sludge. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Fu, M.; Gan, J.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, F. Study on the treatment of tempering lubricant wastewater in steel industry by anaerobic/aerobic process. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, I.M.; Micle, V.; Polyak, E.T.; Gabor, T. Assessment of Soil Quality Status and the Ecological Risk in the Baia Mare, Romania Area. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, G.E.; Micle, V.; Sur, I.M. Lead and Copper Removal from Multi-Metal Contaminated Soils Through Soil Washing Technique Using Humic Substances as Washing Agents: The Influence of the Washing Solution pH. Stud. Univ. Babeș-Bolyai Chem. 2019, 64, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ/T 300-2007; Solid Waste-Extraction Procedure for Leaching Toxicity-Acetic Acid Buffer Solution Method. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Li, W.; Gu, K.; Yu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xin, M.; Bian, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.N.; Zhang, D. Leaching behavior and environmental risk assessment of toxic metals in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash exposed to mature landfill leachate environment. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Q.; Jiang, X.; Lv, G.; Chen, Z.; Lu, S.; Ni, M.; Yan, J.; Deng, X. Evolution of Heavy Metal Speciation in MSWI Fly Ash after Microwave-assisted Hydrothermal Treatment. Chem. Lett. 2018, 47, 960–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, J.; Ruan, X.; Liu, J.; Qian, G. Chemical characteristics and risk assessment of typical municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) fly ash in China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 261, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Liu, X.; Hong, W.; Khalid, Z.; Lv, G.; Jiang, X. Leaching behavior and comprehensive toxicity evaluation of heavy metals in MSWI fly ash from grate and fluidized bed incinerators using various leaching methods: A comparative study. Sci Total Environ 2024, 914, 169595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Peng, Z.; Ye, Q.; Wang, L.; Augustine, R.; Perez, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Tang, H.; Rao, M. Toward environmentally friendly direct reduced iron production: A novel route of comprehensive utilization of blast furnace dust and electric arc furnace dust. Waste Manag. 2021, 135, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.P.; Pitcairn, G.R.; Dalby, R.N. Drug Delivery to the Nasal Cavity: In Vitro and In Vivo Assessment. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carr. Syst. 2004, 21, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, A.O.; Balgobind, A.; Pillay, B. Bioavailability of heavy metals in soil: Impact on microbial biodegradation of organic compounds and possible improvement strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 10197–10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, C.E.; Martínez, C.E. Dissolution of mixed amorphous–crystalline Cd-containing Fe coprecipitates in the presence of common organic ligands. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.R.; Saichek, R.E.; Maturi, K.; Ala, P. Effects of soil moisture and heavy metal concentrations on electrokinetic remediation. Indian Geotech. J. 2002, 32, 258–288. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Sun, C.; Zhang, W.; Marhaba, T. pH effect on heavy metal release from a polluted sediment. J. Chem. 2018, 2018, 7597640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Li, X.; Duan, W.; Xie, M.; Dong, X. Heavy metal stabilization remediation in polluted soils with stabilizing materials: A review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 4127–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wen, X.; Zhou, J.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Yan, B. A critical review on the migration and transformation processes of heavy metal contamination in lead-zinc tailings of China. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 338, 122667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yu, G.; Xie, S.; Pan, L.; Li, C.; You, F.; Wang, Y. Immobilization of heavy metals in ceramsite produced from sewage sludge biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U., Jr. Activated carbons and low cost adsorbents for remediation of tri-and hexavalent chromium from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 762–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Lian, C.; Yu, J.; Yang, H.; Lin, S. Study on the adsorption performance and competitive mechanism for heavy metal contaminants removal using novel multi-pore activated carbons derived from recyclable long-root Eichhornia crassipes. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 276, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Wang, F.; Yan, C.; Tian, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhou, B.; Yuan, R.; Yao, J. Leaching behavior of metals from iron tailings under varying pH and low-molecular-weight organic acids. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 383, 121136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Peng, N.; Zhao, P.; Chen, M.; Deng, F.; Yu, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; Sun, J. Effect of a low-cost and highly efficient passivator synthesized by alkali-fused fly ash and swine manure on the leachability of heavy metals in a multi-metal contaminated soil. Chemospheres 2021, 279, 130558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Huang, Q.; Liu, L.; Fan, G.; Shi, G.; Lu, X.; Gao, Y. Gao, Interactive Effects of Inorganic–Organic Compounds on Passivation of Cadmium in Weakly Alkaline Soil. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Yadav, K.K.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, N.; Cabral-Pinto, M.M.; Rezania, S.; Radwan, N.; Alam, J. Chromium contamination and effect on environmental health and its remediation: A sustainable approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, 112174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potysz, A.; Pędziwiatr, A.; Hedwig, S.; Lenz, M. Bioleaching and toxicity of metallurgical wastes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, S.; Kaur, P.; Kaur, J.; Bhat, S.A. Chapter 9-Solid Waste Management: Challenges and Health Hazards. In Recent Trends in Solid Waste Management; Ravindran, B., Gupta, S.K., Bhat, S.A., Chauhan, P.S., Tyagi, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P.; Huang, Q.; Bourtsalas, A.C.; Themelis, N.J.; Chi, Y.; Yan, J. Review on fate of chlorine during thermal processing of solid wastes. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 78, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 5085.3-2007; Identification Standards for Hazardous Wastes-Identification for Extraction Toxicity. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2007.

- GB 3838-2002; Environmental Quality Standard for Surface Water. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002.

- GB/T14848-2017; Standard for Groundwater Quality. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Yan, J.; Li, C.; Xie, R.; Yu, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yu, W.; Kan, H.; Meng, Q.; Dong, P. Analysis of the Release Characteristics of Blast Furnace Lead Smelting Slag by Integrating Mineralogy and Dynamic/Static Leaching. JOM 2023, 76, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, D.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, S.; Fu, R.; Cui, Y. The risk assessment for metal(loid)s in soil-slag mixing systems: Coupling sequential extraction, leaching tests, and in vitro bioaccessibility assays. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ/T 299-2007; Solid Waste-Extraction Procedure for Leaching Toxicity-Sulphuric Acid & Nitric Acid Method. China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Kicińska, A. Physical and chemical characteristics of slag produced during Pb refining and the environmental risk associated with the storage of slag. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 43, 2723–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarrón, M.; Zornoza, R.; Martínez-Martínez, S.; Muñoz, V.A.; Faz, Á.; Acosta, J.A. Effect of land use and soil properties in the feasibility of two sequential extraction procedures for metals fractionation. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, D.; Liu, X.; Tang, C.; Parikh, S.J.; Xu, J. A novel calcium-based magnetic biochar is effective in stabilization of arsenic and cadmium co-contamination in aerobic soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 387, 122010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; Shimaoka, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.-N.; Ma, L.; Zhang, D. Evaluation of chemical speciation and environmental risk levels of heavy metals during varied acid corrosion conditions for raw and solidified/stabilized MSWI fly ash. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, M.; Mao, T.; Fu, C.; Lin, X.; Li, X.; Yan, J. Effects of curing pathways and thermal-treatment temperatures on the solidification of heavy metal in fly ash by CaCO3 oligomers polymerization. J. Clean. 2022, 362, 132526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).