Hazard Assessment of Ag Nanoparticles in Soil Invertebrates—Strong Impact on the Longer-Term Exposure of Folsomia candida

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Species

2.2. Test Soil

2.3. Test Materials, Characterization, and Spiking

2.4. Ecotoxicity Test Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

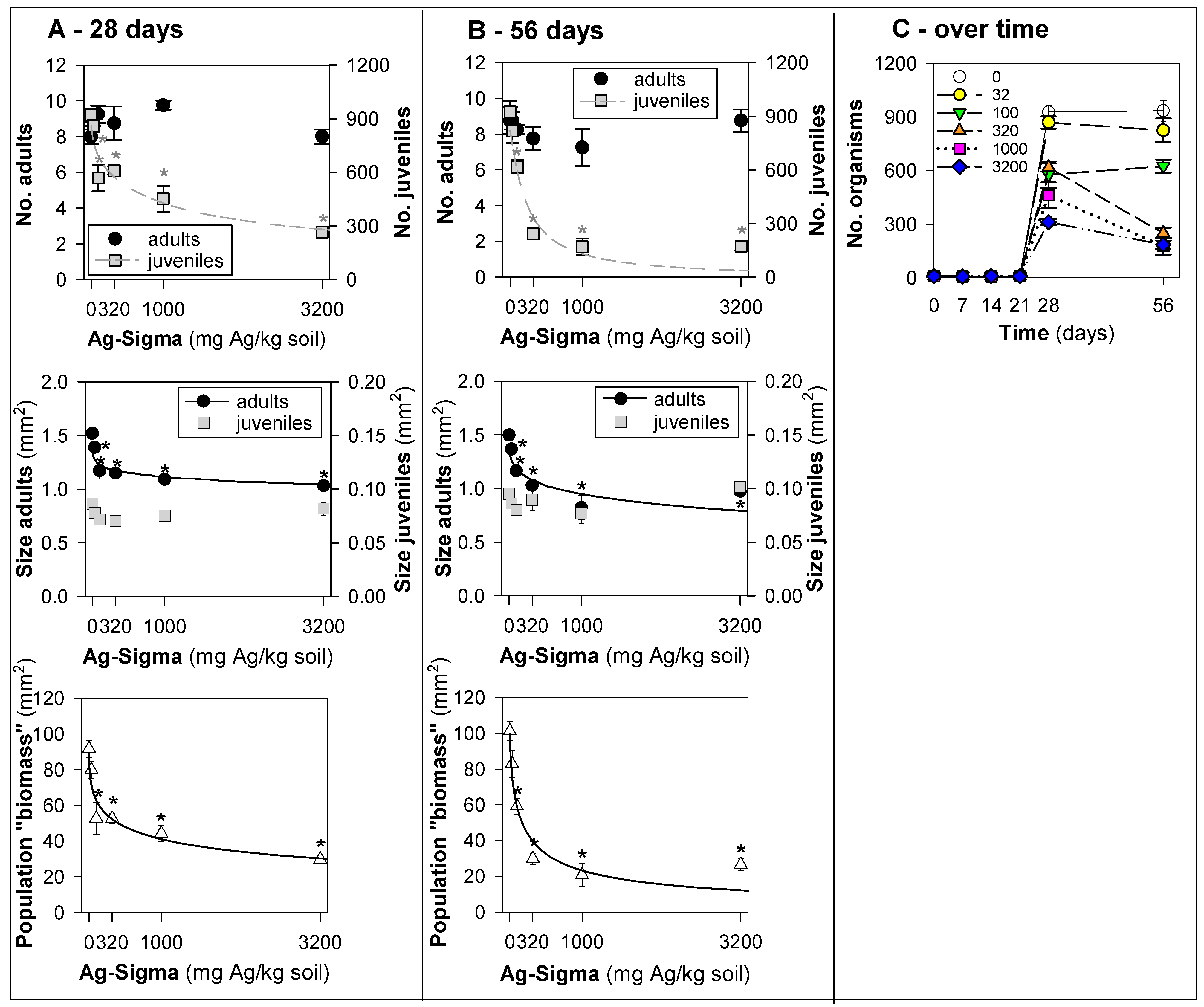

3. Results

4. Discussion

| Species | Ag Material | Soil | LC50 | EC50 (F1/F2) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. candida | Ag-Sigma | LUFA 2.2 | n.e. | 988/234 | Current study |

| F. candida | AgNM300K | LUFA 2.2 | n.e. | 540 | [7] |

| E. crypticus | Ag-Sigma | LUFA 2.2 | 1276 | 446/500 | [19] |

| E. crypticus | AgNM300K | LUFA 2.2 | 675 | 161 | [17] |

| F. candida | AgNO3 | LUFA 2.2 | 179 | 152 | [7] |

| F. candida | AgNO3 | LUFA 2.2 | 284 | 100 | [57] |

| F. candida | AgNO3 | artificial OECD | 97.97 | 126 | [9] |

| F. candida | Ag NPs-2.7 nm | artificial OECD | n.e. | 159 | [9] |

| F. candida | Ag NPs-6.5 nm | artificial OECD | n.e. | 206 | [9] |

| F. candida | Ag NPs-3–8 nm | LUFA 2.2 | n.e. | n.e. (>673) | [57] |

| E. crypticus | AgNO3 | LUFA 2.2 | 75 | 62 | [17] |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IMARC. Silver Nanoparticles Market Report by Synthesis Method (Wet Chemistry, Ion Implantation, Biological), Shape (Spheres, Platelets, Rods, Colloidal Silver Particles, and Others), End Use Industry (Electronics and IT, Healthcare and Lifesciences, Textiles, Food and Beverages, Pharmaceuticals, Cosmetics, Water Treatment, and Others), and Region 2025–2033. Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/silver-nanoparticles-market (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Market.us. Global Silver Nanoparticles Market—Industry Segment Outlook, Market Assessment, Competition Scenario, Trends, and Forecast 2024–2033. Available online: https://market.us/report/silver-nanoparticles-market/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Kyziol-Komosinska, J.; Dzieniszewska, A.; Czupioł, J. Behavior of Silver Species in Soil: Ag Nanoparticles vs. Ionic Ag. Molecules 2024, 29, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.L.; Morel, E.; Cross, R.K.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Baccaro, M.; Lahive, E. Soil species sensitivity distributions for terrestrial risk assessment of silver nanomaterials: The influence of nanomaterial characteristics and soil type. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 2473–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Li, L.; Yang, P.; Luo, L.; Li, L.; Wang, Q. Assessing the environmental occurrence and risk of nano-silver in Hunan, China using probabilistic material flow modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 1249–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkovic, S.; Bornhöft, N.A.; van der Weijden, R.; Nowack, B.; Adam, V. Dynamic probabilistic material flow analysis of engineered nanomaterials in European waste treatment systems. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.; Maria, V.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.; Amorim, M. Ag Nanoparticles (Ag NM300K) in the Terrestrial Environment: Effects at Population and Cellular Level in Folsomia candida (Collembola). Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2015, 12, 12530–12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.A.; Maria, V.L.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Multigenerational exposure of Folsomia candida to silver: Effect of different contamination scenarios (continuous versus pulsed and recovery). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavkova, D.; Beklova, M.; Kopel, P.; Havelkova, B. Effects of Silver Nanoparticles and Ions Exposure on the Soil Invertebrates Folsomia candida and Enchytraeus crypticus. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 105, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicogna, J.R.; Ritchie, E.E.; Scroggins, R.P.; Princz, J.I. A comparison of the effects of silver nanoparticles and silver nitrate on a suite of soil dwelling organisms in two field soils. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.S.; Engelke, M.; Zhang, X.; Lesnikov, E.; Köser, J.; Eickhorst, T.; Filser, J. Collembola Reproduction Decreases with Aging of Silver Nanoparticles in a Sewage Sludge-Treated Soil. Front. Environ. Sci. 2017, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Mariyadas, J.; Amorim, M.J. Soil type dependent toxicity of AgNM300K can be predicted by internal concentrations in earthworms. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoults-Wilson, W.A.; Reinsch, B.C.; Tsyusko, O.V.; Bertsch, P.M.; Lowry, G.V.; Unrine, J.M. Role of Particle Size and Soil Type in Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles to Earthworms. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makama, S.; Piella, J.; Undas, A.; Dimmers, W.J.; Peters, R.; Puntes, V.F.; van den Brink, N.W. Properties of silver nanoparticles influencing their uptake in and toxicity to the earthworm Lumbricus rubellus following exposure in soil. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Ortiz, M.; Lahive, E.; George, S.; Ter Schure, A.; Van Gestel, C.A.M.; Jurkschat, K.; Svendsen, C.; Spurgeon, D.J. Short-term soil bioassays may not reveal the full toxicity potential for nanomaterials; bioavailability and toxicity of silver ions (AgNO3) and silver nanoparticles to earthworm Eisenia fetida in long-term aged soils. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 203, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.I.L.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Mechanisms of response to silver nanoparticles on Enchytraeus albidus (Oligochaeta): Survival, reproduction and gene expression profile. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 254–255, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicho, R.C.; Ribeiro, T.; Rodrigues, N.P.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Effects of Ag nanomaterials (NM300K) and Ag salt (AgNO3) can be discriminated in a full life cycle long term test with Enchytraeus crypticus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 318, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.I.L.; Zanoni, I.; Blosi, M.; Costa, A.L.; Hristozov, D.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Safe and sustainable by design Ag nanomaterials: A case study to evaluate the bio-reactivity in the environment using a soil model invertebrate. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 171860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, N.P.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Novel understanding of toxicity in a life cycle perspective—The mechanisms that lead to population effect—The case of Ag (nano)materials. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.C.F.; Tourinho, P.S.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; van Gestel, C.A.M.; Amorim, M.J.B. Toxicokinetics of Ag (nano)materials in the soil model Enchytraeus crypticus (Oligochaeta)—impact of aging and concentration. Env. Sci. Nano 2021, 8, 2629–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioh Lobe, P.D.; Filser, J.; Voua Otomo, P. Avoidance behaviour of Enchytraeus albidus (Oligochaeta) after exposure to AgNPs and AgNO3 at constant and fluctuating temperature. Eur. J. Soil. Biol. 2018, 87, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariyadas, J.; Amorim, M.J.B.; Jensen, J.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J. Earthworm avoidance of silver nanomaterials over time. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoults-Wilson, W.A.; Zhurbich, O.I.; McNear, D.H.; Tsyusko, O.V.; Bertsch, P.M.; Unrine, J.M. Evidence for avoidance of Ag nanoparticles by earthworms (Eisenia fetida). Ecotoxicology 2011, 20, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.I.L.; Hansen, D.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Effects of silver nanoparticles to soil invertebrates: Oxidative stress biomarkers in Eisenia fetida. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 199, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.I.L.; Roca, C.P.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. High-throughput transcriptomics reveals uniquely affected pathways: AgNPs, PVP-coated AgNPs and Ag NM300K case studies. Env. Sci. Nano 2017, 4, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyusko, O.V.; Hardas, S.S.; Shoults-Wilson, W.A.; Starnes, C.P.; Joice, G.; Butterfield, D.A.; Unrine, J.M. Short-term molecular-level effects of silver nanoparticle exposure on the earthworm, Eisenia fetida. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 171, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novo, M.; Lahive, E.; Díez-Ortiz, M.; Matzke, M.; Morgan, A.J.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Svendsen, C.; Kille, P. Different routes, same pathways: Molecular mechanisms under silver ion and nanoparticle exposures in the soil sentinel Eisenia fetida. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 205, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Velasco, N.; Peña-Cearra, A.; Bilbao, E.; Zaldibar, B.; Soto, M. Integrative assessment of the effects produced by Ag nanoparticles at different levels of biological complexity in Eisenia fetida maintained in two standard soils (OECD and LUFA 2.3). Chemosphere 2017, 181, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waalewijn-Kool, P.L.; Diez Ortiz, M.; van Straalen, N.M.; van Gestel, C.A.M. Sorption, dissolution and pH determine the long-term equilibration and toxicity of coated and uncoated ZnO nanoparticles in soil. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 178, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.F.M.; Gomes, S.I.L.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Shorter lifetime of a soil invertebrate species when exposed to copper oxide nanoparticles in a full lifespan exposure test. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, B.; Gomes, S.I.L.; Campodoni, E.; Sandri, M.; Sprio, S.; Blosi, M.; Costa, A.L.; Amorim, M.J.B.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J. Environmental Hazards of Nanobiomaterials (Hydroxyapatite-Based NMs)—A Case Study with Folsomia candida—Effects from Long Term Exposure. Toxics 2022, 10, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, B.; Gomes, S.I.L.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Impacts of Longer-Term Exposure to AuNPs on Two Soil Ecotoxicological Model Species. Toxics 2022, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicho, R.C.; Santos, F.C.F.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Multigenerational effects of copper nanomaterials (CuONMs) are different of those of CuCl2: Exposure in the soil invertebrate Enchytraeus crypticus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.J.B.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J. Plastic pollution—A case study with Enchytraeus crypticus—From micro-to nanoplastics. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.J.; Maria, V.L.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Fate and Effect of Nano Tungsten Carbide Cobalt (WCCo) in the Soil Environment: Observing a Nanoparticle Specific Toxicity in Enchytraeus crypticus. Env. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11394–11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Stahlmecke, B.; Romazanov, J.; Kuhlbusch, T.; Van Doren, E.; De Temmerman, P.-J.; Mast, J.; Wick, P.; Krug, H.; Locoro, G.; et al. NM-Series of Representative Manufactured Nanomaterials—NM-300 Silver Characterisation, Stability, Homogeneity; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cofell, E.R.; Nwabara, U.O.; Bhargava, S.S.; Henckel, D.E.; Kenis, P.J.A. Investigation of Electrolyte-Dependent Carbonate Formation on Gas Diffusion Electrodes for CO2 Electrolysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 15132–15142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofell, E.R.; Park, Z.; Nwabara, U.O.; Harris, L.C.; Bhargava, S.S.; Gewirth, A.A.; Kenis, P.J.A. Potential Cycling of Silver Cathodes in an Alkaline CO2 Flow Electrolyzer for Accelerated Stress Testing and Carbonate Inhibition. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 12013–12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Lee, W.H.; Won, J.H.; Ko, Y.J.; Kim, S.; Min, B.K.; Lee, K.Y.; Jung, W.S.; Oh, H.S. Enhancement of Catalytic Activity and Selectivity for the Gaseous Electroreduction of CO2 to CO: Guidelines for the Selection of Carbon Supports. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2021, 5, 2100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdus Samad, U.; Alam, M.A.; Sherif, E.-S.M.; Alam, M.; Shaikh, H.; Alharthi, N.H.; Al-Zahrani, S.M. Synergistic Effect of Ag and ZnO Nanoparticles on Polypyrrole-Incorporated Epoxy/2pack Coatings and Their Corrosion Performances in Chloride Solutions. Coatings 2019, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrazia, F.W.; Leitune, V.C.B.; Garcia, I.M.; Arthur, R.A.; Samuel, S.M.W.; Collares, F.M. Effect of silver nanoparticles on the physicochemical and antimicrobial properties of an orthodontic adhesive. J. Appl. Oral. Sci. 2016, 24, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymczak, M.; Pankowski, J.A.; Kwiatek, A.; Grygorcewicz, B.; Karczewska-Golec, J.; Sadowska, K.; Golec, P. An effective antibiofilm strategy based on bacteriophages armed with silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Guideline for Testing of Chemicals No. 232. Collembolan Reproduction Test in Soil; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, B.; Maria, V.L.; Römbke, J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Multigenerational exposure of Folsomia candida to ivermectin—Using avoidance, survival, reproduction, size and cellular markers as endpoints. Geoderma 2019, 337, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Guidance on Sample Preparation and Dosimetry for the Safety Testing of Manufactured Nanomaterials. Series on the Safety of Manufactured Nanomaterials No. 36; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, L.A.; Amorim, M.J.B.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J. Assessing the toxicity of safer by design CuO surface-modifications using terrestrial multispecies assays. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 678, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, L.V.; Hrács, K.; Nagy, P.I.; Seres, A. Effects of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Panagrellus redivivus (Nematoda) and Folsomia candida (Collembola) in Various Test Media. Int. J. Env. Res. 2018, 12, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waalewijn-Kool, P.L.; Ortiz, M.D.; Lofts, S.; van Gestel, C.A.M. The effect of pH on the toxicity of zinc oxide nanoparticles to Folsomia candida in amended field soil. Env. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 2349–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kool, P.L.; Ortiz, M.D.; van Gestel, C.A.M. Chronic toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles, non-nano ZnO and ZnCl2 to Folsomia candida (Collembola) in relation to bioavailability in soil. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2713–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waalewijn-Kool, P.L.; Klein, K.; Forniés, R.M.; van Gestel, C.A.M. Bioaccumulation and toxicity of silver nanoparticles and silver nitrate to the soil arthropod Folsomia candida. Ecotoxicology 2014, 23, 1629–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, H.E. On the structure and function of the mouthparts of the soil-inhabiting collembolan Folsomia candida. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1972, 4, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westheide, W.; Graefe, U. Two new terrestrial Enchytraeus species (Oligochaeta, Annelida). J. Nat. Hist. 1992, 26, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Ortiz, M.; Lahive, E.; Kille, P.; Powell, K.; Morgan, A.J.; Jurkschat, K.; Van Gestel, C.A.M.; Mosselmans, J.F.W.; Svendsen, C.; Spurgeon, D.J. Uptake routes and toxicokinetics of silver nanoparticles and silver ions in the earthworm Lumbricus rubellus. Env. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerl, J.; Tsurkan, M.; Hensel, R.; Neinhuis, C.; Werner, C. The multi-layered protective cuticle of Collembola: A chemical analysis. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.N.; Gotoh, T. Comparative ultrastructural observation of the cuticle and muscle of an enchytraeid (Enchytraeus japonensis) and an oribatid species (Tectocepheus velatus) using transmission electron microscopy. J. Fac. Agric. 2009, 54, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, A.K.; Chatterjee, T.; Chakravarty, A.; Ghosh, S.K. Silver nanoparticle–induced developmental inhibition of Drosophila melanogaster accompanies disruption of genetic material of larval neural stem cells and non-neuronal cells. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, B.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Yan, S.J. Silver nanoparticles have lethal and sublethal adverse effects on development and longevity by inducing ROS-mediated stress responses. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, Z.; Popham, H.J.R.; Stanley, D.; Suresh, D.; Finley, K.; Campbell, J.; Kannan, R.; Upendran, A. Dietary silver nanoparticles reduce fitness in a beneficial, but not pest, insect species. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 93, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Luan, T.; Lin, L. Effects of undissociated SiO2 and TiO2 nano-particles on molting of Daphnia pulex: Comparing with dissociated ZnO nano particles. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 2021, 222, 112491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Endpoint | Generation/ Time (Days) | EC10 (95% CI) | EC50 (95% CI) | EC90 (95% CI) | Model and Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival | F0/28 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | - |

| Reprod. | F1/28 | 33 (9–115) | 988 (567–1721) | 8098 (1970–33,286) | Thres2P (S: 0.37; Y0: 860.8; r2: 0.7) |

| Size (adults) | F0/28 | 58 (10–346) | >>3200 | >>3200 | Thres2P (S: 0.15; Y0: 1.4; r2: 0.5) |

| Size (juveniles) | F1/28 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | - |

| Biomass (total population) | F0 + F1/28 | 4 (1–26) | 622 (340–1138) | >>3200 | Log2P (S: 0.25; Y0: 92; r2: 0.8) |

| Survival | F1/56 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | - |

| Reprod. | F2/56 | 34 (15–80) | 234 (161–340) | 1591 (691–3664) | Log2P (S: 0.66; Y0: 817.3; r2: 0.8) |

| Size (adults) | F1/56 | 57 (12–259) | >>3200 | >>3200 | Thres2P (S: 0.27; Y0: 1.4; r2: 0.4) |

| Size (juveniles) | F2/56 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | - |

| Biomass (total population) | F1 + F2/56 | 6 (2–22) | 165 (107–256) | 4318 (1427–13,063) | Log2P (S: 0.39; Y0: 101; r2: 0.9) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes, S.I.L.; Scott-Fordsmand, J.J.; Amorim, M.J.B. Hazard Assessment of Ag Nanoparticles in Soil Invertebrates—Strong Impact on the Longer-Term Exposure of Folsomia candida. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060210

Gomes SIL, Scott-Fordsmand JJ, Amorim MJB. Hazard Assessment of Ag Nanoparticles in Soil Invertebrates—Strong Impact on the Longer-Term Exposure of Folsomia candida. Journal of Xenobiotics. 2025; 15(6):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060210

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes, Susana I. L., Janeck J. Scott-Fordsmand, and Mónica J. B. Amorim. 2025. "Hazard Assessment of Ag Nanoparticles in Soil Invertebrates—Strong Impact on the Longer-Term Exposure of Folsomia candida" Journal of Xenobiotics 15, no. 6: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060210

APA StyleGomes, S. I. L., Scott-Fordsmand, J. J., & Amorim, M. J. B. (2025). Hazard Assessment of Ag Nanoparticles in Soil Invertebrates—Strong Impact on the Longer-Term Exposure of Folsomia candida. Journal of Xenobiotics, 15(6), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/jox15060210